Abstract

Transcription factor B-cell lymphoma/leukemia 11A (BCL11A) gene encodes a zinc-finger protein that is predominantly expressed in brain and hematopoietic tissue. BCL11A functions mainly as a transcriptional repressor that is crucial in brain, hematopoietic system development, as well as fetal-to-adult hemoglobin switching. The expression of this gene is regulated by microRNAs, transcription factors and genetic variations. A number of studies have recently shown that BCL11A is involved in β-hemoglobinopathies, hematological malignancies, malignant solid tumors, 2p15-p16.1 microdeletion syndrome, and Type II diabetes. It has been suggested that BCL11A may be a potential prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target for some diseases. In this review, we summarize the current research state of BCL11A, including its biochemistry, expression, regulation, function, and its possible clinical application in human diseases.

Keywords: Clinical application, Expression, Function, Human diseases, Regulation

Introduction

The B-cell lymphoma/leukemia 11A (BCL11A) is a common retroviral insertion site in murine leukemia and is initially identified from aberrant t(2;14)(p13;q32.3) chromosomal translocations in human B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas [1,2], and later identified to have important functions in various other human diseases. However, the mechanisms by which BCL11A is linked to these human diseases are not clear. Here, we summarize the expression, regulation, function and clinical application of BCL11A, and focus on known BCL11A-related human diseases.

The biochemistry of BCL11A

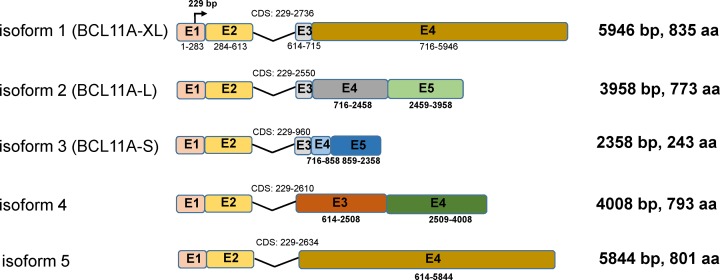

BCL11A, also known as ecotropic viral integration site 9 homolog (EVI9) or COUP-TF-interacting protein 1 (CTIP1), is encoded by a gene located on chromosome 2p16.1 and highly conserved to mouse Bcl11a (musBcl11a) [2]. Five isoforms of the BCL11A gene have been reported, which sharing identical exon 1 and 2 (Figure 1). BCL11A-XL, BCL11A-L, and BCL11A-S have been studied extensively. BCL11A-XL is the longest isoform consisting of four exons with a total length of 5946 bp. It encodes a 125 kDa Kruppel-like zinc-finger protein containing six C2H2 zinc-fingers, a proline-rich region, and an acidic domain [2]. BCL11A specifically binds to 5′-GGCCGG-3′ sequences and functions mainly as a transcriptional repressor [3].

Figure 1. Transcript Variants of BCL11A.

The five transcript variants share the same exon 1 and exon 2, but the remaining exons are different. BCL11A-XL encodes the longest isoform. Their common translation initiation site is in exon 1 at 229 bp.

Expression and regulation of BCL11A

Expression

BCL11A is mainly expressed in brain and most hematopoietic cells, including hematopoietic stem cells, common lymphoid progenitors, B cells, and early T-cell progenitors, although it is weakly expressed in T lymphocytes [4,5].

Remarkably, each isoform of BCL11A has specific expression patterns. BCL11A-XL, for example, is preferentially expressed in normal B-cells, whereas BCL11A-S is expressed in B-cell malignant cells [2]. In the human and rat brain, BCL11A-S is widely distributed, but BCL11A-L is mainly expressed in the cerebral cortex [6,7]. The roles of different expression patterns of BCL11A in regulating diseases are unclear, and further study is needed.

Regulation

The expression of BCL11A is generally regulated by three ways. First, miRNAs regulation. MiRNAs are small (19–24 nucleotides), highly conserved, non-coding RNA molecules, which act as a translational repressor by regulating gene expression at the post-transcriptional level. Lee et al. [8] and de Vasconcellos et al. [9] found that the let-7 family of miRNAs can regulate BCL11A expression. More recent studies indicated that miR-137 and miR-146a could suppress BCL11A expression by targeting its 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) [10,11]. Other miRNAs, like miR-210, miR-30a, miR-486-3p and miR-138-5p, can reduce BCL11A expression by directly binding to the 3′UTR region or the coding sequence of BCL11A gene [12–15] (Table 1).

Table 1. BCL11A is regulated by some miRNAs, transcription factors, and interacts with some transcription factors to play its functions.

| Regulator | Relationship with BCL11A | Function of BCL11A | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| MiRLet-7 family | Indirectly promote | HbF production | [8,9] |

| MiR-210 | Directly suppresses | HbF production | [12] |

| MiR-138-5p | Directly suppresses | HbF production | [15] |

| MiR-486-3p | Directly suppresses | HbF production | [14] |

| MiR-30a | Directly suppresses | Associated with several clinical variables | [13] |

| MiR-137 | Directly suppresses | Impaired stem cells stemness and tumorigenesis | [10] |

| MiR-146a | Directly suppresses | Inhibit cell growth and promote apoptosis | [11] |

| 14q32/miRNA clusters | Directly suppress | Promote B-cell transformation and differentiation | [75] |

| MiR-4753, miR-6809 | Directly suppress | Circepsti1-mir-4753/6809-bcl11a pathway affects the proliferation and apoptosis of triple negative breast cancer | [81] |

| KLF1 | Positively regulates | HbF production | [16,17] |

| POGZ | Positively regulates | HbF production | [18] |

| HRI | Positively regulates | HbF production | [19] |

| Mi2β | Positively regulates | HbF production | [22] |

| SOX2 | Positively regulates | Tumor growth | [21] |

| FOXQ1 | Positively regulates | Cell proliferation and apoptosis | [23,87] |

| UCHL1 | Negatively regulates | Cell apoptosis | [24] |

| SIRT1 | Negatively regulates | HbF production | [25] |

| IGF2BP1 | Negatively regulates | HbF production | [20] |

| HbF production | |||

| DNMT1 | Interacts | Stem cells maintenance and tumor development | [38,10] |

| CASK | Interacts | Axon arborization | [44] |

| UBC9 | Interacts | Sumo-conjugation | [58] |

| RBBP4 | Interacts | Recruit epigenetic complexes to regulate transcription and promote tumorigenesis | [80] |

| BCL6 | Interacts | Leukemogenesis | [1] |

| Nf1 | Cooperates with | Leukemogenesis | [54] |

| MLL-AF9 | Cooperates with | Leukemogenesis | [26] |

| DNMT3A (R882), FLT3-ITD mutations | Positive correlation | May associated with several clinical variables | [66] |

| MDR1 | Positive correlation | Poor response to chemotherapy | [76] |

| Mdm2, Pten | Positive correlation | Low complete remission | [74] |

Abbreviations: BCL6, B-cell cll/lymphoma 6; CASK, calcium/calmodulin-dependent serine kinase; DNMT1, methyltransferase 1; DNMT3A, DNA methyltransferase 3 α; FLT3-ITD, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3-internal tandem duplication; FOXQ1, Forkhead box Q1; HRI, heme-regulated inhibitor; IGF2BP1, insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1; KLF1, Kruppel-like factor 1; Mdm2, murine double minute 2; MDR1, ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 1; Mi2β, chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 4; MiR, microRNA; Mll-AF9, mixed lineage leukemia-myeloid/lymphoid or mixed lineage leukemia translocated to chromosome 3 fusion protein; Nf1, Neurofibromin 1; POGZ, Pogo transposable element derived with ZNF domain; Pten, phosphatase and tensin homolog; RBBP4, Retinoblastoma-binding protein 4; SIRT1, Sirtuin 1; SOX2, SRY-box 2; UBC9, E2 SUMO-conjugating protein UBC9; UCHL1, Ubiquitin carboxyl terminal hydrolase 1.

Dysregulation of BCL11A may be an initial trigger for some human diseases.

Second, transcription factors regulation. Some transcription factors can regulate BCL11A expression. Kruppel-like factor 1 (KLF1), a transcription factor that inhibits γ-globin expression by positively regulating BCL11A [16,17]. In hematopoietic progenitor cells, pogo transposable element derived with ZNF domain (POGZ) can bind to the BCL11A gene promoter to enhance the transcriptional repression of BCL11A [18]. Other transcription factors like heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI) [19], insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1 (IGF2BP1) [20], SRY-box 2 (SOX2) [21], chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 4 (Mi2β) [22], forkhead box Q1 (FOXQ1) [23], ubiquitin carboxyl terminal hydrolase 1 (UCHL1) [24], and sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) [25] have been reported to regulate BCL11A (Table 1).

Finally, genetic variations, including insertion, deletion, and translocation of chromosome as well as variations within BCL11A gene. Increased expression of musBcl11a was shown in a mixed lineage leukemia-myeloid/lymphoid or mixed lineage leukemia translocated to chromosome 3 (Mll-AF9) mice model insertion with murine leukemia virus [26]. 2p15-p16.1 chromosome microdeletion may lead to haploinsufficiency of BCL11A [27,28]. Some groups reported that BCL11A single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), especially rs11886868 and rs1427407, can reduce the expression of BCL11A [29,30]. Similarly, disrupt the enhancer of BCL11A gene can reduce its expression [31,32].

In summary, the normal level of BCL11A is strictly regulated by a variety of ways. Imbalances among regulatory factors or genetic variations lead to dysregulation of BCL11A and may be an initial trigger for some human diseases.

Functions of BCL11A

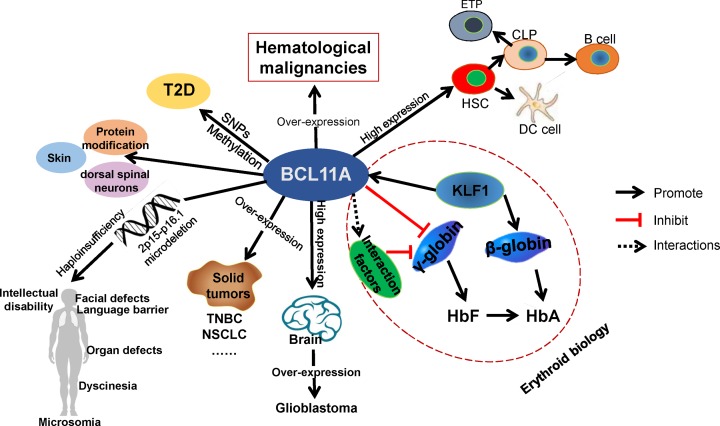

BCL11A performs its functions in brain, multiple cell lineages, and fetal-to-adult hemoglobin switching as well as other fields, as shown in Table 2 and Figure 2.

Table 2. BCL11A directly or indirectly regulates the downstream targets expression.

| Target | Relationship | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| γ-Globin | Negatively regulates | HbF production | [42,43] |

| TBR1 | Negatively regulates | Acquisition of the subcerebral fate | [48] |

| Sema3c | Negatively regulates | Migration of Cortical Projection Neurons | [49] |

| Bcl2, Bcl2-xL, Mdm2, and p53 | Positively regulates Bcl2, Bcl2-xL, Mdm2/4 and negatively regulates p53 | Promote lymphoid development via suppress the p53 pathway | [51] |

| SETD8 | Positively regulates | Lung squamous carcinoma growth | [21] |

| ISL1 | Positively regulates | Cancer stemness and tumorigenesis | [10] |

| DCC, MAP1b | Positively regulates | Axon branching and dendrite outgrowth | [45] |

| E2-2 | Positively regulates | Cell differentiation | [50] |

| Flt3 | Positively regulates | Dendritic cell development | [55] |

| Fosl2 and Elvol4 | Positively regulates | Epidermal differentiation and lipid metabolism | [56] |

| Frzb | May positively regulate | Wnt pathway | [57] |

Abbreviations: Bcl2, B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2; DCC, colorectal carcinoma; E2-2, transcription factor 4; Elvol4, Fatty acid elongase 4; Frzb, frizzled-related protein 3; Fosl2, Fos-related antigen2; Flt3, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3; ISL1, Islet-1; MAP1b, microtubule-associated protein 1; Mdm2, murine double minute 2; p53, tumor protein p53; Sema3c, Semaphorin 3C; SETD8, lysine methyltransferase 5A; TBR1, T-box brain 1.

Figure 2. Known expressions and functions of BCL11A.

BCL11A is highly expressed in brain and most hematopoietic system cells. Overexpression of BCL11A was found in hematological malignancies and some malignant solid tumors, such as TNBC and NSCLC. 2p15-p16.1 microdeletions lead to haploinsufficiency of BCL11A and may lead to 2p15-p16.1 microdeletion syndrome. BCL11A gene SNPs or DNA methylation may contribute to the development of T2D. In erythroid biology, BCL11A directly inhibits γ-globin and plays a crucial role in fetal-to-adult hemoglobin switching, suggesting that BCL11A is a promising therapeutic gene for β-hemoglobinopathies; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; DC cell, dendritic cell; ETP, early T-cell progenitor; HbA, adult hemoglobin; HbF, fetal hemoglobin; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; T2D, Type II diabetes; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

BCL11A has recently attracted heightened interest due to its crucial role in fetal-to-adult hemoglobin switching in erythroid biology. It was discovered that the BCL11A, as a critical factor for γ-globin gene silencing, can reduce fetal hemoglobin (HbF) to promote adult hemoglobin (HbA) in human erythroid cells [33]. Further study revealed that KLF1 directly activates β-globin expression and indirectly suppresses γ-globin via acting BCL11A [16,34]. Several studies have suggested that BCL11A may silence the γ-globin by interacting with lysine-specific demethylase 1 and repressor element-1 silencing transcription factor corepressor 1 (LSD1/CoREST) complex, nucleosome remodeling deacetylase (NuRD) histone demethylase complex, DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) and SRY-box 6 (SOX6) [35–38]. These transcription factors may collaborate with BCL11A, bind to the distal or proximal promoters of the γ-globin gene and enhance the inhibitory ability of BCL11A to γ-globin expression. As a gene editing tool, CRISPR-Cas9 (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-associated protein 9) has been widely used for genomic editing in eukaryotic cells. With the help of short guide RNA (sgRNA), the Cas9 protein can cut the PAM-containing (protospacer adjacent motif, 5′-NGG-3′) DNA sequence and induce target gene mutations. Specific sgRNA was used to target deletion of BCL11A gene, such as deletion of BCL11A erythroid enhancers [31,39]. With this method, BCL11A was validated as a key regulator for HbF expression. Moreover, knockdown of BCL11A by RNA interference and chemical drugs each showed an increase of HbF [40,41]. Two research groups, Liu et al. [42] and Martyn et al. [43], have recently shown that BCL11A directly binds to TGACCA motif at -115 bp of the γ-globin promoter to silence the γ-globin expression, demonstrating remarkable progress in understanding the simplified mechanism of BCL11A participation in γ- to β-globin switching.

As mentioned above, BCL11A is highly expressed in brain and indispensable for brain development [2,6]. CASK, a calcium/calmodulin-dependent serine kinase, interacts with BCL11A to regulate axon branching in the brain [44]. Interestingly, BCL11A also target deleted in colorectal carcinoma (DCC) and microtubule-associated protein 1 (MAP1b), two genes with important influence in axon branching [45], providing added evidence of a possible regulatory network of how BCL11A might be involved in axon branching. Based on the yeast-two-hybrid screening of a human adult brain cDNA library, BCL11A was identified as a novel co-regulator of nuclear receptor subfamily 2 group E member 1 (TLX) and may associate with TLX-related functions, such as neural stem cells maintenance and brain tumors [46]. BCL11A strictly regulates the sensory area development of layer 4 neurons [47]. Cánovas et al. [48] found that different expression levels of BCL11A decide the subcerebral and corticothalamic fates in layers 5 and 6 neurons through directly repressing T-box brain 1 (TBR1). Wiegreffe et al. [49] suggested that musBcl11a negatively regulates semaphorin 3C (Sema3c) to control the migration of cortical neurons. In comparison with erythroid biology, the functions and mechanisms of BCL11A in the brain are still largely unclear and further study is needed.

Besides the functions listed above, BCL11A also plays an important role in the hematopoietic system. BCL11A is essential for multiple cell lineages such as B-cell development, plasmacytoid dendritic (pDC) cells maturation, and maintenance of stemness in stem cell [5,50–52]. MusBcl11a knockout reduces the self-renewal ability of hematopoietic stem cells and delays the cell cycle through the cyclin-dependent kinase 6 (Cdk6) pathway in musBcl11a-deficient mouse [5]. Yu et al. [53] showed that lack of musBcl11a might activate the p53 pathway and lead to apoptosis of early B cells and common lymphoid progenitors as well as abolish the ability of hematopoietic stem cells to translate to B, T, and natural killer (NK) cells. In addition, BCL11A was shown to regulate cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (p21) [54], early B-cell factor 1 (Ebf1), paired box 5 (Pax5) [51], B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 (Bcl2), murine double minute 2 (Mdm2) [53] as well as FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (Flt3) [55] in the hematopoietic system, but the regulatory mechanisms are not clear. Overall, the functions of BCL11A may mainly relate to cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis in the hematopoietic system.

Studies have shown that BCL11A also involved in skin, dorsal spinal neurons development, and protein modification. Deletion of BCL11A decreases the expression of differentiation-associated gene, Fos-related antigen2 (Fosl2) and lipid-metabolism-related gene, Fatty acid elongase 4 (Elvol4), leads to impairment of epidermal permeability barrier that increases the risk of skin infection [56]. In dorsal spinal neurons development, secreted frizzled-related protein 3 (Frzb), which belongs to Wnt signaling pathway, is a downstream target of musBcl11a. Dysregulation of Frzb shows a spinal cord innervation dysfunction in the absence of musBcl11a [57]. Besides, a study by Kuwata et al. [58] revealed that BCL11A has a function of protein modification and may participate in the small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) conjugation system by interacting with E2 SUMO-conjugating protein UBC9, and then recruits SUMO1 by its N-terminal region. Currently, there are a limited number of studies that focused on these functions of BCL11A and more other functions of BCL11A need to be developed.

BCL11A in human diseases

In recent years, much progress has been achieved in investigating the roles of BCL11A in some diseases, including β-hemoglobinopathies, hematological malignancies, malignant solid tumors, intellectual disability, and Type II diabetes (Figure 2 and Table 3).

Table 3. Functions of BCL11A in different human diseases.

| Human diseases | Functions of BCL11A | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| β-Hemoglobinopathies | BCL11A directly inhibits the expression of γ-globin | [59–65] |

| Hematological malignancies | BCL11A functions as an oncogene, high level of BCL11A blocks cell differentiation, inhibits cell apoptosis and promotes cell proliferation | [53,54,66,67,74–78] |

| Triple negative breast cancer | BCL11A functions as an oncogene, high level of BCL11A promotes tumor formation | [10,68,80,81] |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | BCL11A functions as an oncogene, high level of BCL11A promotes tumor formation, enhances cell migration and invasion | [13,21,83,84] |

| Glioblastoma | BCL11A is highly expressed in glioblastoma and the functions of BCL11A are still unknown | [85] |

| Neuroblastoma | High level of BCL11A promotes neuroblastoma cell line growth and inhibits apoptosis | [11] |

| Laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma | BCL11A has higher single-nucleotide polymorphisms odds ratios and higher plasma concentrations in advanced stage of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma, but the functions are unknown | [86] |

| Ovarian cancer | High level of BCL11A may increase cell apoptosis | [24] |

| Prostate cancer | BCL11A knockdown suppresses prostate cancer cell lines proliferation and invasion | [23] |

| 2p15-p16.1 microdeletion syndrome | BCL11A haploinsufficiency | [88–94] |

| Type II diabetes | BCL11A is highly expressed in Type II diabetes and negatively correlated with insulin secretion | [95–105] |

BCL11A in β-hemoglobinopathies

β-Hemoglobinopathies, particularly sickle cell disease (SCD) and β-thalassemia, represent the most common monogenic disease in the world and are caused by adult β-globin gene mutation [59]. Improving the levels of HbF is considered an effective therapeutic strategy for β-hemoglobinopathies. Studies revealed that HbF levels can be regulated by BCL11A gene [37,60]. Through SCD transgenic mice model, the Xu [61] and Brendel research groups [62], respectively, found that inactivation of the BCL11A gene rescues HbF levels and corrects the hematologic and pathologic defects of SCD. Furthermore, studies from Zhou and co-workers found that KLF1 can indirectly regulate the γ-globin by affecting the expression of BCL11A, providing more evidence for the development of clinical therapeutic drugs using this regulatory network [16,22,34].

Targeting BCL11A by chemical drugs, RNA interference has additionally been shown to increase the production of HbF [8,40,63]. Recently, thanks to the benefits from CRISPR-Cas9 technology, target genes can be safely and accurately edited. Canver et al. [31] developed a pooled guide RNA library to screen human and mouse enhancers and found that BCL11A erythroid enhancer plays an important role in HbF re-induction. Similarly, in a BCL11A enhancer deleted mouse model, γ-globin gene silencing was delayed [64]. Aside from the CRISPR-Cas9, Chang et al. [65] and Psatha et al. [32] used zinc finger nucleases to destroy the BCL11A erythroid-specific enhancer contributing to improve erythroid phenotype and increase the fetal globin level in CD34-positive hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). Notably, destroying the coding region of the BCL11A gene demonstrates an adverse effect on HSPCs function while destroying these enhancers did not affect the survival and proliferation of HSPCs and other cell lineages in vivo, indicating the practical value of BCL11A erythroid-specific enhancer editing. These findings provide an autologous stem cell editing and transplantation therapy strategy for β-hemoglobinopathies patients. All above findings suggest that BCL11A is a promising therapeutic gene for β-hemoglobinopathies.

BCL11A in malignant tumors

Previous studies have shown that BCL11A is also highly expressed in some hematological malignancies and malignant solid tumors, and is associated with poor clinical prognosis [13,21,66–68]. Two mechanisms may explain the abnormal activation of BCL11A in these malignant tumors. One is BCL11A gene variations, including virus integration [54,69], gene copy number amplification [70,71], and chromosomal translocation [72]. Another is abnormal regulations of BCL11A gene, such as inactivation of microRNAs [13], abnormally activated long non-coding RNAs [73] and dysregulation of transcription factors [21].

BCL11A in hematological malignancies

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) with SYBR Green Dye or Taqman probe is applied to detect the mRNA levels of BCL11A in myeloid and lymphoid leukemia bone marrow samples. Studies have demonstrated that BCL11A is highly expressed in initial myeloid and lymphoid malignancies compared with healthy control and elevated levels predict worsened clinical outcomes, such as lower complete remission, shorter overall survival and higher relapse rate and a poor response to chemotherapy [54,67,74–76]. Thus, BCL11A is considered as a potential diagnostic biomarker for some hematological malignancies.

Studies indicated BCL11A may be involved in hematological malignancies by blocking cell differentiation, apoptosis, and promoting cell proliferation. In 2000, Nakamura et al. [1] suggested that Evi9a and Evi9c, the isoforms of musBcl11a, have a potential to transform NIH-3T3 cells. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis found that BCL11A was down-regulated during myeloid differentiation of HL60 cells induced by all-trans-retinoic acid [4], and similar results were observed in K562 cells treated with butyric acid [67], indicating that high level of BCL11A may cause leukemia by block myeloid differentiation. Through retroviral insertion screening, Yin et al. [54] found that the overexpression of BCL11A accelerated the acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in neurofibromin 1 (Nf1) deficiency bone marrow cells. Overexpression of BCL11A may trigger the hematopoietic cells cell-cycle through directly inhibits p21 or indirectly inhibits p21 via p53 or some other factors [53,54]. Still by retroviral insertion screening, BCL11A was identified to accelerate the process of AML caused by t(9;11) translocation by cooperating with MLL-AF9 [26]. Wu et al. [77] furtherly analyzed the global gene expression profile, the results showed that BCL11A may inhibit the apoptosis of B-cell lymphoma cell line through the transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and Wingless/Integrated (WNT) signaling pathways. It is noteworthy that knockdown of BCL11A mRNA by small interfering RNA combined with vincristine can decrease cell proliferation and increase cell apoptosis in B-cell lymphoma [78]. Thus, BCL11A knockdown may potentiate other clinical drugs, providing a powerful strategy for clinical treatment for hematological malignancies in future.

In addition, overexpression of BCL11A may cooperate with ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 1 (MDR1) [76], Mdm2, phosphatase and tensin homolog (Pten) [74], and MLL-AF9 [26], DNA methyltransferase 3α (DNMT3A) R882 mutation and FLT3-ITD (internal tandem duplication) mutation [66] to participate in hematological malignancies. The functions and mechanisms of BCL11A cooperates with these genes in hematological malignancies are still need further research.

BCL11A in malignant solid tumors

The role of BCL11A in malignant solid tumors has rarely been reported, but overexpression of BCL11A has been detected in some malignant solid tumors, suggesting that it may be a potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarker in these tumors.

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) accounts for approximately 15% of breast cancer and carries a poor prognosis [79]. Recently, BCL11A was identified highly expressed in TNBC through the analysis of the METABRIC (Molecular Taxonomy of Breast Cancer International Consortium) and TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) databases, which was verified by qRT–PCR and immunohistochemistry [68]. As a novel breast cancer gene, high expression of BCL11A significantly correlates with TNBC subtypes and high histological grade. High levels of BCL11A promotes TNBC development while knockdown of BCL11A sharply decreases the tumorigenicity of TNBC cells and reduces the tumor size in mice model [68]. These findings suggest BCL11A is a new potential diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target for TNBC; yet, whether BCL11A can be used for breast cancer diagnosis or drug development is still a challenge since the molecular mechanism of BCL11A in TNBC is unclear.

Thankfully, advancements in our understanding of the molecular functions of BCL11A have been made. Moody et al. [80] found that BCL11A binds to retinoblastoma-binding protein 4 (RBBP4) and gives BCL11A capacity to recruit histone methyltransferase and deacetylase complexes to initiate transcriptional repression of the downstream gene. Chen et al. [10] also found that BCL11A interacts with DNMT1 to suppress islet-1 (ISL1) expression in TNBC. The prevention of this interaction impaired the stemness and tumorigenesis of breast cancer through elevating ISL1 in vitro and in vivo. More recently Chen et al. [81] further showed that circular RNA circEPSTI1 was highly expressed in TNBC and could target miR-4753 and miR-6809 to eliminate their inhibitory effect on BCL11A, thus preventing cell apoptosis and stimulate cell proliferation. Overall, the current research provides a theoretical basis for the development of new drugs to target BCL11A. These research efforts will improve the clinical outcomes of patients diagnosed with TNBC.

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) can be defined into four types according to its histopathology: squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), large cell carcinoma (LCC), adenocarcinoma (AC), and undifferentiated NSCLC [82]. Affymetrix mRNA array, TCGA database analysis and immunohistochemistry showed that BCL11A was overexpressed in SCC and LCC, mainly in SCC [13,21,83]. High BCL11A expression level, especially BCL11A-XL, was positively correlated with squamous histology and smoking status, and was an independent prognostic factor for disease-free survival in early-stage NSCLC [13,83]. High level of BCL11A may enhance NSCLC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [21,73], but the molecular mechanism of BCL11A in NSCLC is still unknown. Recently, Lazarus et al. [21] found that SOX2–BCL11A–SETD8 (lysine methyltransferase 5A), as a novel regulatory axis, is essential for SCC development. Disrupting this axis with SETD8 inhibitor reduces SCC cells growth significantly and highlights that SOX2–BCL11A–SETD8 regulatory pathway may be a potential candidate framework for drug development in NSCLC. A case report from a 64-year-old Chinese woman diagnosed with NSCLC first showed that BCL11A was a novel ALK receptor tyrosine kinase (ALK) fusion gene [84], BCL11A–ALK showed certain resistance to ALK inhibitor crizotinib and considered as an oncogenic fusion gene. Its roles and mechanisms in NSCLC are still unknown and need to be studied in the future.

Studies have also revealed that high expression of BCL11A may be associated with neuroblastoma [11], glioblastoma [85], laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma [86], ovarian cancer [24], and prostate cancer [23]. As mentioned above, BCL11A is a key factor in brain development but little is known about BCL11A in brain tumors. Recent study showing that BCL11A may contribute to glioblastoma with specific expression patterns [85], which provide a helpful platform for future studies. Down-regulation of BCL11A can induce apoptosis and inhibit proliferation in neuroblastoma cells [11]. In laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC), patients with advanced stage (III and IV) of LSCC had significantly higher BCL11A SNP odds ratios and higher plasma BCL11A concentrations than early stage (I and II) [86]. In prostate cancer, BCL11A was significantly down-regulated when FOXQ1 loss its function, and led to decreased proliferation, invasion and increased apoptosis in prostate cancer cells [23]. Interestingly, in colorectal cancer, FOXQ1 overexpression positively correlated with BCL11A [87]. The FOXQ1–BCL11A regulatory system may provide a new understanding within the molecular mechanism of some tumors.

BCL11A in 2p15-p16.1 microdeletion syndrome

2p15-p16.1 microdeletion syndrome is characterized by intellectual disability, microcephaly, microsomia, congenital organ defects, and facial defects etc. 2p15-p16.1 microdeletion results in the haploinsufficiency of BCL11A; thus, BCL11A is considered as a candidate gene for 2p15-p16.1 microdeletion syndrome using microarray based comparative genomic hybridization and fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis [88,89]. Two case reports on patients with language barriers [90,91] have revealed that a patient with a novel frameshift mutation in exon 4 of BCL11A displayed a similar phenotype to a patient with a 200 kb 2p15-p16.1 microdeletion covering the entire BCL11A gene. Interestingly, a 2p15-p16.1 microdeletion patient with intact BCL11A alleles still showed reduced BCL11A expression and increased HbF level, suggesting that the deletion region of BCL11A downstream may be a novel erythroid regulatory element and required for BCL11A expression [92]; thus, this region may serve as a novel therapy target for β-hemoglobinopathies.

BCL11A is crucially important in the care of 2p15-p16.1 microdeletion syndrome and restoring the normal expression of BCL11A may be conducive to the treatment of this disease. Aside from BCL11A gene, 2p15-p16.1 microdeletion involve other genes, such as poly(A) polymerase γ (PAPOLG), REL (an NF-kB gene family member) [93], ubiquitin specific peptidase 34 (USP34), and peroxisomal biogenesis factor 13 (PEX13) [94]. These genes may work together with BCL11A and contribute to the development of diseases. More evidence is needed to verify whether BCL11A is the main pathogenic factor in 2p15-p16.1 microdeletion syndrome.

BCL11A in Type II diabetes

Type II diabetes (T2D) is a chronic disease that affects glucose metabolism, characterized by insulin deficiency or insulin resistance. Study has confirmed that BCL11A expression is negatively correlated with insulin secretion, qRT-PCR showed that the mRNA levels of BCL11A in islets were significantly higher in non-responsive T2D patients compared with healthy donors [95]. Two mechanisms may responsible for BCL11A overexpression in T2D. One is ‘feed-forward’ mechanism, as a glucose-induced gene, high expression of BCL11A is triggered by initial hyperglycemia, increased BCL11A inhibits insulin secretion and causes severe hyperglycemia, which further enhance the expression of BCL11A and finally leads to T2D. Another is BCL11A SNP mutations, such as rs10490072 and rs243021 [96,97], these SNPs may increase the level of islet BCL11A expression and may reduce insulin secretion. Studies have indicated that an increased risk of T2D is caused by BCL11A SNPs in African-American, North African Arabs, European Americans, and Han and Mongolian populations in China [97–101]. Dysregulation of BCL11A may affect the insulin response to glucose in rs10490072 via BCL11A-SIRT1 pathway and may affect the glucagon secretion in rs243021 [102–104]. Interestingly, Tang et al. [105] suggested that besides BCL11A SNPs, BCL11A gene methylation is strongly associated with male T2D patients and may influence the triglyceride metabolism. The difference in modification of BCL11A gene in gender provides a new angle to understand its functions in T2D.

Conclusion

BCL11A is a crucial mediator of the regulatory network responsible for the development of the brain and multiple cell lineages. BCL11A also participates in human diseases and functions as an oncogene in some malignant tumors. The mechanisms of BCL11A involvement in these diseases are still unclear. Fortunately, the research on BCL11A has attracted heightened attention in recent years due to its pivotal role in fetal-to-adult hemoglobin switching. BCL11A and its related regulatory pathways have become the most promising therapeutic targets for β-hemoglobinopathies. BCL11A also may serve as a valuable diagnostic biomarker and therapeutic target for majority of human hematological malignancies, TNBC, and NSCLC. Studies of BCL11A in other diseases are still scattered or just in their infancy. More research is needed to help us understand the functions and mechanisms of BCL11A and apply it in future clinical treatment.

Availability of Data and Material

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jinling Zhang for proofreading the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AC

adenocarcinoma

- ALK

ALK receptor tyrosine kinase

- ALL

acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- AML

acute myeloid leukemia

- BCL11A

transcription factor B-cell lymphoma/leukemia 11A

- Bcl2

B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2

- BCL6

B-cell cll/lymphoma 6

- CASK

calcium/calmodulin-dependent serine kinase

- Cdk6

cyclin-dependent kinase 6

- CRISPR-Cas9

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-associated protein 9

- DCC

colorectal carcinoma

- DNMT1

methyltransferase 1

- DNMT3A

DNA methyltransferase 3α

- Ebf1

early B-cell factor 1

- Elvol4

fatty acid elongase 4

- Flt3

FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3

- Fosl2

Fos-related antigen2

- FOXQ1

Forkhead box Q1

- Frzb

frizzled-related protein 3

- HbA

adult hemoglobin

- HbF

fetal hemoglobin

- HRI

heme-regulated inhibitor

- HSPC

hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell

- IGF2BP1

insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1

- ISL1

Islet-1

- KLF1

Kruppel-like factor 1

- LCC

large cell carcinoma

- LSCC

laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma

- LSD1/CoREST

lysine-specific demethylase 1 and repressor element-1 silencing transcription factor corepressor 1 complex

- MAP1b

microtubule-associated protein 1

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- Mdm2

murine double minute 2

- MDR1

ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 1

- Mi2β

chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 4

- miRNA

microRNA

- Mll-AF9

mixed lineage leukemia-myeloid/lymphoid or mixed lineage leukemia translocated to chromosome 3 fusion protein

- Nf1

Neurofibromin 1

- NK

natural killer

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- NuRD

nucleosome remodeling deacetylase complex

- P21

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A

- PAPOLG

poly(A) polymerase gamma

- Pax5

paired box 5

- pDC

plasmacytoid dendritic

- PEX13

peroxisomal biogenesis factor 13

- POGZ

Pogo transposable element derived with ZNF domain

- Pten

phosphatase and tensin homolog

- RBBP4

retinoblastoma-binding protein 4

- REL

an NF-kB gene family member

- SCC

squamous cell carcinoma

- SCD

sickle cell disease

- Sema3c

Semaphorin 3C

- SETD8

lysine methyltransferase 5A

- SIRT1

Sirtuin 1

- SNP

single-nucleotide polymorphism

- SOX2

SRY-box 2

- SOX6

RY-box 6

- T2D

Type II diabetes

- TBR1

T-box brain 1

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor-β

- TLX

nuclear receptor subfamily 2 group E member 1

- TNBC

Triple-negative breast cancer

- UBC9

E2 SUMO-conjugating protein UBC9

- UCHL1

Ubiquitin carboxyl terminal hydrolase 1

- USP34

Ubiquitin specific peptidase 34

- UTR

untranslated region

- WNT

Wingless/Integrated

Contributor Information

Lijuan Wang, Email: wanglj730@163.com.

Fengyuan Che, Email: che1971@126.com.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a Linyi People’s Hospital Doctoral Research Foundation [2016LYBS05]; Linyi Science and Technology Development Project [201818026]; the key research project program of Shandong Province [2016GSF201056 and 2018GSF118035]; the Chinese Medical Health Science and Technology Development Plan of Shandong Province [2017-462]; and Zhejiang Province Public Welfare Technology Application Research Project [2016C37025].

Author Contribution

F.C. and L.W. conceived and designed the project. J.Y. drafted the manuscript. X.X. and Y.Y. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Nakamura T. (2000) Evi9 encodes a novel zinc finger protein that physically interacts with BCL6, a known human B-cell proto-oncogene product. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 3178–3186 10.1128/MCB.20.9.3178-3186.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Satterwhite E. (2001) The BCL11 gene family: involvement of BCL11A in lymphoid malignancies. Blood 98, 3413–3420 10.1182/blood.V98.12.3413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avram D., Fields A., Senawong T., Topark-Ngarm A.and Leid M. (2002) COUP-TF (chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor)-interacting protein 1 (CTIP1) is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein. Biochem. J. 368, 555–563 10.1042/bj20020496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saiki Y., Yamazaki Y., Yoshida M., Katoh O.and Nakamura T. (2000) Human EVI9, a homologue of the mouse myeloid leukemia gene, is expressed in the hematopoietic progenitors and down-regulated during myeloid differentiation of HL60 cells. Genomics 70, 387–391 10.1006/geno.2000.6385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luc S. (2016) Bcl11a deficiency leads to hematopoietic stem cell defects with an aging-like phenotype. Cell Rep. 16, 3181–3194 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuo T.Y.and Hsueh Y.P. (2007) Expression of zinc finger transcription factor Bcl11A/Evi9/CTIP1 in rat brain. J. Neurosci. Res. 85, 1628–1636 10.1002/jnr.21300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.den Hoed J. (2018) Functional characterization of TBR1 variants in neurodevelopmental disorder. Sci. Rep. 8, 14279. 10.1038/s41598-018-32053-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee Y.T. (2013) LIN28B-mediated expression of fetal hemoglobin and production of fetal-like erythrocytes from adult human erythroblasts ex vivo. Blood 122, 1034–1041 10.1182/blood-2012-12-472308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Vasconcellos J.F. (2017) Tough decoy targeting of predominant let-7 miRNA species in adult human hematopoietic cells. J. Transl. Med. 15, 169. 10.1186/s12967-017-1273-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen F., Luo N., Hu Y., Li X.and Zhang K. (2018) MiR-137 suppresses triple-negative breast cancer stemness and tumorigenesis by perturbing BCL11A-DNMT1 interaction. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 47, 2147–2158 10.1159/000491526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li S.H., Li J.P., Chen L.and Liu J.L. (2018) miR-146a induces apoptosis in neuroblastoma cells by targeting BCL11A. Med. Hypotheses 117, 21–27 10.1016/j.mehy.2018.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gasparello J. (2017) BCL11A mRNA targeting by miR-210: a possible network regulating gamma-globin gene expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 2530. 10.3390/ijms18122530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang B.Y. (2013) BCL11A overexpression predicts survival and relapse in non-small cell lung cancer and is modulated by microRNA-30a and gene amplification. Mol. Cancer 12, 61. 10.1186/1476-4598-12-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lulli V. (2013) MicroRNA-486-3p regulates gamma-globin expression in human erythroid cells by directly modulating BCL11A. PLoS One 8, e60436. 10.1371/journal.pone.0060436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun K.T. (2017) Reciprocal regulation of gamma-globin expression by exo-miRNAs: Relevance to gamma-globin silencing in beta-thalassemia major. Sci. Rep. 7, 202. 10.1038/s41598-017-00150-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou D., Liu K., Sun C.W., Pawlik K.M.and Townes T.M. (2010) KLF1 regulates BCL11A expression and gamma- to beta-globin gene switching. Nat. Genet. 42, 742–744 10.1038/ng.637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shariati L. (2016) Genetic disruption of the KLF1 gene to overexpress the gamma-globin gene using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. J. Gene Med. 18, 294–301 10.1002/jgm.2928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gudmundsdottir B. (2018) POGZ is required for silencing mouse embryonic beta-like hemoglobin and human fetal hemoglobin expression. Cell Rep. 23, 3236–3248 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grevet J.D. (2018) Domain-focused CRISPR screen identifies HRI as a fetal hemoglobin regulator in human erythroid cells. Science 361, 285–290 10.1126/science.aao0932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Vasconcellos J.F. (2017) IGF2BP1 overexpression causes fetal-like hemoglobin expression patterns in cultured human adult erythroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E5664–E5672 10.1073/pnas.1609552114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazarus K.A. (2018) BCL11A interacts with SOX2 to control the expression of epigenetic regulators in lung squamous carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 9, 3327. 10.1038/s41467-018-05790-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amaya M. (2013) Mi2beta-mediated silencing of the fetal gamma-globin gene in adult erythroid cells. Blood 121, 3493–3501 10.1182/blood-2012-11-466227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang X. (2016) Inhibition of FOXQ1 induces apoptosis and suppresses proliferation in prostate cancer cells by controlling BCL11A/MDM2 expression. Oncol. Rep. 36, 2349–2356 10.3892/or.2016.5018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin C. (2013) UCHL1 is a putative tumor suppressor in ovarian cancer cells and contributes to cisplatin resistance. J. Cancer 4, 662–670 10.7150/jca.6641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dai Y., Chen T., Ijaz H., Cho E.H.and Steinberg M.H. (2017) SIRT1 activates the expression of fetal hemoglobin genes. Am. J. Hematol. 92, 1177–1186 10.1002/ajh.24879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergerson R.J. (2012) An insertional mutagenesis screen identifies genes that cooperate with Mll-AF9 in a murine leukemogenesis model. Blood 119, 4512–4523 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dias C. (2016) BCL11A haploinsufficiency causes an intellectual disability syndrome and dysregulates transcription. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 99, 253–274 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.05.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basak A. (2015) BCL11A deletions result in fetal hemoglobin persistence and neurodevelopmental alterations. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 2363–2368 10.1172/JCI81163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaouch L., (2016) rs11886868 and rs4671393 of BCL11A associated with HbF level variation and modulate clinical events among sickle cell anemia patients. Hematology 21, 425–429 10.1080/10245332.2015.1107275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhanushali A.A., Patra P.K., Nair D., Verma H.and Das B.R. (2015) Genetic variant in the BCL11A (rs1427407), but not HBS1-MYB (rs6934903) loci associate with fetal hemoglobin levels in Indian sickle cell disease patients. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 54, 4–8 10.1016/j.bcmd.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Canver M.C. (2015) BCL11A enhancer dissection by Cas9-mediated in situ saturating mutagenesis. Nature 527, 192–197 10.1038/nature15521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Psatha N. (2018) Disruption of the BCL11A erythroid enhancer reactivates fetal hemoglobin in erythroid cells of patients with beta-thalassemia major. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 10, 313–326 10.1016/j.omtm.2018.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sankaran V.G., Xu J.and Orkin S.H. (2010) Transcriptional silencing of fetal hemoglobin by BCL11A. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1202, 64–68 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05574.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Esteghamat F. (2013) Erythropoiesis and globin switching in compound Klf1::Bcl11a mutant mice. Blood 121, 2553–2562 10.1182/blood-2012-06-434530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu J. (2013) Corepressor-dependent silencing of fetal hemoglobin expression by BCL11A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 6518–6523 10.1073/pnas.1303976110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu J. (2010) Transcriptional silencing of {gamma}-globin by BCL11A involves long-range interactions and cooperation with SOX6. Genes Dev. 24, 783–798 10.1101/gad.1897310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sankaran V.G. (2008) Human fetal hemoglobin expression is regulated by the developmental stage-specific repressor BCL11A. Science 322, 1839–1842 10.1126/science.1165409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roosjen M. (2014) Transcriptional regulators Myb and BCL11A interplay with DNA methyltransferase 1 in developmental silencing of embryonic and fetal beta-like globin genes. FASEB J. 28, 1610–1620 10.1096/fj.13-242669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khosravi M.A. (2019) Targeted deletion of BCL11A gene by CRISPR-Cas9 system for fetal hemoglobin reactivation: a promising approach for gene therapy of beta thalassemia disease. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 854, 398–405 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.04.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macari E.R., Schaeffer E.K., West R.J.and Lowrey C.H. (2013) Simvastatin and t-butylhydroquinone suppress KLF1 and BCL11A gene expression and additively increase fetal hemoglobin in primary human erythroid cells. Blood 121, 830–839 10.1182/blood-2012-07-443986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guda S. (2015) miRNA-embedded shRNAs for Lineage-specific BCL11A Knockdown and Hemoglobin F Induction. Mol. Ther. 23, 1465–1474 10.1038/mt.2015.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu N. (2018) Direct Promoter Repression by BCL11A Controls the Fetal to Adult Hemoglobin Switch. Cell 173, 430.e17–442.e17 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martyn G.E. (2018) Natural regulatory mutations elevate the fetal globin gene via disruption of BCL11A or ZBTB7A binding. Nat. Genet. 50, 498–503 10.1038/s41588-018-0085-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuo T.Y., Hong C.J., Chien H.L.and Hsueh Y.P. (2010) X-linked mental retardation gene CASK interacts with Bcl11A/CTIP1 and regulates axon branching and outgrowth. J. Neurosci. Res. 88, 2364–2373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuo T.Y., Hong C.J.and Hsueh Y.P. (2009) Bcl11A/CTIP1 regulates expression of DCC and MAP1b in control of axon branching and dendrite outgrowth. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 42, 195–207 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Estruch S.B. (2012) The oncoprotein BCL11A binds to orphan nuclear receptor TLX and potentiates its transrepressive function. PLoS One 7, e37963. 10.1371/journal.pone.0037963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Greig L.C., Woodworth M.B., Greppi C.and Macklis J.D. (2016) Ctip1 controls acquisition of sensory area identity and establishment of sensory input fields in the developing neocortex. Neuron 90, 261–277 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Canovas J. (2015) The specification of cortical subcerebral projection neurons depends on the direct repression of TBR1 by CTIP1/BCL11a. J. Neurosci. 35, 7552–7564 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0169-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wiegreffe C. (2015) Bcl11a (Ctip1) controls migration of cortical projection neurons through regulation of Sema3c. Neuron 87, 311–325 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ippolito G.C. (2014) Dendritic cell fate is determined by BCL11A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, E998–E1006 10.1073/pnas.1319228111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu P. (2003) Bcl11a is essential for normal lymphoid development. Nat. Immunol. 4, 525–532 10.1038/ni925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Powers A.N.and Satija R. (2015) Single-cell analysis reveals key roles for Bcl11a in regulating stem cell fate decisions. Genome Biol. 16, 199. 10.1186/s13059-015-0778-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu Y. (2012) Bcl11a is essential for lymphoid development and negatively regulates p53. J. Exp. Med. 209, 2467–2483 10.1084/jem.20121846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yin B. (2009) A retroviral mutagenesis screen reveals strong cooperation between Bcl11a overexpression and loss of the Nf1 tumor suppressor gene. Blood 113, 1075–1085 10.1182/blood-2008-03-144436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu X. (2013) Bcl11a controls Flt3 expression in early hematopoietic progenitors and is required for pDC development in vivo. PLoS One 8, e64800. 10.1371/journal.pone.0064800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li S. (2017) Transcription factor CTIP1/ BCL11A regulates epidermal differentiation and lipid metabolism during skin development. Sci. Rep. 7, 13427. 10.1038/s41598-017-13347-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.John A. (2012) Bcl11a is required for neuronal morphogenesis and sensory circuit formation in dorsal spinal cord development. Development 139, 1831–1841 10.1242/dev.072850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kuwata T.and Nakamura T. (2008) BCL11A is a SUMOylated protein and recruits SUMO-conjugation enzymes in its nuclear body. Genes Cells 13, 931–940 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01216.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vinjamur D.S., Bauer D.E.and Orkin S.H. (2018) Recent progress in understanding and manipulating haemoglobin switching for the haemoglobinopathies. Br. J. Haematol. 180, 630–643 10.1111/bjh.15038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sankaran V.G. (2009) Developmental and species-divergent globin switching are driven by BCL11A. Nature 460, 1093–1097 10.1038/nature08243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu J. (2011) Correction of sickle cell disease in adult mice by interference with fetal hemoglobin silencing. Science 334, 993–996 10.1126/science.1211053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brendel C. (2016) Lineage-specific BCL11A knockdown circumvents toxicities and reverses sickle phenotype. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 3868–3878 10.1172/JCI87885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Finotti A. (2015) Development and characterization of K562 cell clones expressing BCL11A-XL: Decreased hemoglobin production with fetal hemoglobin inducers and its rescue with mithramycin. Exp. Hematol. 43, 1062–1071 e1063 10.1016/j.exphem.2015.08.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith E.C. (2016) Strict in vivo specificity of the Bcl11a erythroid enhancer. Blood 128, 2338–2342 10.1182/blood-2016-08-736249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chang K.H. (2017) Long-term engraftment and fetal globin induction upon BCL11A gene editing in bone-marrow-derived CD34(+) hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 4, 137–148 10.1016/j.omtm.2016.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tao H. (2016) BCL11A expression in acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk. Res. 41, 71–75 10.1016/j.leukres.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yin J. (2017) Corrigendum to “BCL11A expression in acute phase chronic myeloid leukemia” [Leuk. Res. 47 (2016) 88-92]. Leuk. Res. 52, 67. 10.1016/j.leukres.2016.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Khaled W.T. (2015) BCL11A is a triple-negative breast cancer gene with critical functions in stem and progenitor cells. Nat. Commun. 6, 5987. 10.1038/ncomms6987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Luo W.J. (2004) Epstein-Barr virus is integrated between REL and BCL-11A in American Burkitt lymphoma cell line (NAB-2). Lab. Invest. 84:, 1193–1199 10.1038/labinvest.3700152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Martinez-Climent J.A. (2003) Transformation of follicular lymphoma to diffuse large cell lymphoma is associated with a heterogeneous set of DNA copy number and gene expression alterations. Blood 101, 3109–3117 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jamal-Hanjani M. (2017) Tracking the evolution of non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 2109–2121 10.1056/NEJMoa1616288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Trubia M. (2006) Characterization of a recurrent translocation t(2;3)(p15-22;q26) occurring in acute myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia 20, 48–54 10.1038/sj.leu.2404020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liao J.and Xie N. (2019) Long noncoding RNA DSCAM-AS1 functions as an oncogene in non-small cell lung cancer by targeting BCL11A. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacological Sci. 23, 1087–1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xu L., Wu H., Wu X., Li Y.and He D. (2018) The expression pattern of Bcl11a, Mdm2 and Pten genes in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 14, e124–e128 10.1111/ajco.12690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Agueli C. (2010) 14q32/miRNA clusters loss of heterozygosity in acute lymphoblastic leukemia is associated with up-regulation of BCL11a. Am. J. Hematol. 85, 575–578 10.1002/ajh.21758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guo X. (2018) BCL11A and MDR1 expressions have prognostic impact in patients with acute myeloid leukemia treated with chemotherapy. Pharmacogenomics 19, 343–348 10.2217/pgs-2017-0157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu H., Gao Y., Ding L., He D.and Li Y. (2014) Gene expression profile analysis of SUDHL6 cells with siRNA-mediated BCL11A downregulation. Cell Biol. Int. 38, 1205–1214 10.1002/cbin.10332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.He D., Wu H., Ding L.and Li Y. (2014) Combination of BCL11A siRNA with vincristine increases the apoptosis of SUDHL6 cells. Eur. J. Med. Res. 19, 34. 10.1186/2047-783X-19-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ali A.M. (2017) Triple negative breast cancer: a tale of two decades. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 17, 491–499 10.2174/1871520616666160725112335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moody R.R. (2018) Probing the interaction between the histone methyltransferase/deacetylase subunit RBBP4/7 and the transcription factor BCL11A in epigenetic complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 2125–2136 10.1074/jbc.M117.811463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen B. (2018) circEPSTI1 as a prognostic marker and mediator of triple-negative breast cancer progression. Theranostics 8, 4003–4015 10.7150/thno.24106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Torre L.A. (2015) Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 65, 87–108 10.3322/caac.21262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang N. (2015) The BCL11A-XL expression predicts relapse in squamous cell carcinoma and large cell carcinoma. J. Thorac. Dis. 7, 1630–1636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tian Q., Deng W.J.and Li Z.W. (2017) Identification of a novel crizotinib-sensitive BCL11A-ALK gene fusion in a nonsmall cell lung cancer patient. Eur. Respir. J. 49, 1602149. 10.1183/13993003.02149-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cai Y.D. (2018) Identification of the gene expression rules that define the subtypes in glioma. J. Clin. Med. 7, 350. 10.3390/jcm7100350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhou J. (2017) Genetic polymorphisms and plasma levels of BCL11A contribute to the development of laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One 12, e0171116. 10.1371/journal.pone.0171116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kaneda H. (2010) FOXQ1 is overexpressed in colorectal cancer and enhances tumorigenicity and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 70, 2053–2063 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bagheri H. (2016) Identifying candidate genes for 2p15p16.1 microdeletion syndrome using clinical, genomic, and functional analysis. JCI Insight 1, e85461. 10.1172/jci.insight.85461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shimbo H. (2017) Haploinsufficiency of BCL11A associated with cerebellar abnormalities in 2p15p16.1 deletion syndrome. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 5, 429–437 10.1002/mgg3.289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Soblet J. (2018) BCL11A frameshift mutation associated with dyspraxia and hypotonia affecting the fine, gross, oral, and speech motor systems. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 176, 201–208 10.1002/ajmg.a.38479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Peter B., Matsushita M., Oda K.and Raskind W. (2014) De novo microdeletion of BCL11A is associated with severe speech sound disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 164A, 2091–2096 10.1002/ajmg.a.36599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Funnell A.P. (2015) 2p15-p16.1 microdeletions encompassing and proximal to BCL11A are associated with elevated HbF in addition to neurologic impairment. Blood 126, 89–93 10.1182/blood-2015-04-638528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hancarova M. (2013) A patient with de novo 0.45 Mb deletion of 2p16.1: the role of BCL11A, PAPOLG, REL, and FLJ16341 in the 2p15-p16.1 microdeletion syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 161A, 865–870 10.1002/ajmg.a.35783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mimouni-Bloch A., Yeshaya J., Kahana S., Maya I.and Basel-Vanagaite L. (2015) A de-novo interstitial microduplication involving 2p16.1-p15 and mirroring 2p16.1-p15 microdeletion syndrome: clinical and molecular analysis. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 19, 711–715 10.1016/j.ejpn.2015.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Peiris H. (2018) Discovering human diabetes-risk gene function with genetics and physiological assays. Nat. Commun. 9, 3855. 10.1038/s41467-018-06249-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Staiger H. (2008) Novel meta-analysis-derived type 2 diabetes risk loci do not determine prediabetic phenotypes. PLoS One 3, e3019. 10.1371/journal.pone.0003019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cauchi S. (2012) European genetic variants associated with type 2 diabetes in North African Arabs. Diabetes Metab. 38, 316–323 10.1016/j.diabet.2012.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Langberg K.A. (2012) Single nucleotide polymorphisms in JAZF1 and BCL11A gene are nominally associated with type 2 diabetes in African-American families from the GENNID study. J. Hum. Genet. 57, 57–61 10.1038/jhg.2011.133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Keaton J.M. (2014) A comparison of type 2 diabetes risk allele load between African Americans and European Americans. Hum. Genet. 133, 1487–1495 10.1007/s00439-014-1486-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bai H. (2015) Association Analysis of Genetic Variants with Type 2 Diabetes in a Mongolian Population in China. J. Diabetes Res. 2015, 613236. 10.1155/2015/613236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kong X. (2015) The Association of Type 2 Diabetes Loci Identified in Genome-Wide Association Studies with Metabolic Syndrome and Its Components in a Chinese Population with Type 2 Diabetes. PLoS One 10, e0143607. 10.1371/journal.pone.0143607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Liang F., Kume S.and Koya D. (2009) SIRT1 and insulin resistance. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 5, 367–373 10.1038/nrendo.2009.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Simonis-Bik A.M. (2010) Gene variants in the novel type 2 diabetes loci CDC123/CAMK1D, THADA, ADAMTS9, BCL11A, and MTNR1B affect different aspects of pancreatic beta-cell function. Diabetes 59, 293–301 10.2337/db09-1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Jonsson A. (2013) Effects of common genetic variants associated with type 2 diabetes and glycemic traits on alpha- and beta-cell function and insulin action in humans. Diabetes 62, 2978–2983 10.2337/db12-1627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tang L. (2014) BCL11A gene DNA methylation contributes to the risk of type 2 diabetes in males. Exp. Ther. Med. 8, 459–463 10.3892/etm.2014.1783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.