Abstract

Climate change refugia in the terrestrial biosphere are areas where species are protected from global environmental change and arise from natural heterogeneity in landscapes and climate. Within the marine realm, ocean acidification, or the global decline in seawater pH, remains a pervasive threat to organisms and ecosystems. Natural variability in seawater carbon dioxide (CO2) chemistry, however, presents an opportunity to identify ocean acidification refugia (OAR) for marine species. Here, we review the literature to examine the impacts of variable CO2 chemistry on biological responses to ocean acidification and develop a framework of definitions and criteria that connects current OAR research to management goals. Under the concept of managing vulnerability, the most likely mechanisms by which OAR can mitigate ocean acidification impacts are by reducing exposure to harmful conditions or enhancing adaptive capacity. While local management options, such as OAR, show some promise, they present unique challenges, and reducing global anthropogenic CO2 emissions must remain a priority.

Keywords: adaptive capacity, biological response, management, mitigation, ocean acidification, pH variability, refugia, vulnerability

Ocean acidification refugia (OAR) may exist due to natural spatial and temporal variability in seawater carbon dioxide (CO2) across marine ecosystems. Based on a literature review of biological responses to variable CO2, we identify two types of refugia, those that reduce harmful exposures to ocean acidification and those that boost the adaptive capacity of marine organisms. The conditions that shape OAR must persist through time and may benefit from additional management actions.

![]()

1. INTRODUCTION

Climate change refugia are areas where localized environmental conditions protect species from the unfavorable or harmful conditions associated with broad transformations of the Earth's climate (Ashcroft, 2010; Keppel et al., 2012; Morelli et al., 2016). A priori knowledge of anthropogenic climate change trajectories and biological impacts provides opportunities to identify climate change refugia and invest in local management actions. The oceans play a critical role in regulating the Earth's climate, are of enormous socioeconomical value, and are disproportionally affected by climate change (IPCC, 2014). The three main climate change phenomena expected to impact many marine ecosystems are warming, sea level rise, and ocean acidification (Doney et al., 2012; Gattuso et al., 2015; Hoegh‐Guldberg & Bruno, 2010; Poloczanska et al., 2013). Ocean acidification refers to the global changes in seawater carbon dioxide (CO2) chemistry associated with the absorption of anthropogenic CO2 emissions (Doney, Fabry, Feely, & Kleypas, 2009), which results in increases in pCO2 and [HCO3 −] and decreases in pH and calcium carbonate saturation state (Ω) (Zeebe & Wolf‐Gladrow, 2001). These changes in CO2 chemistry have the potential to negatively affect many marine organisms and ecosystems (Kroeker et al., 2013; Pörtner, Karl, & Boyd, 2014) and alter the global carbon cycle for millennia to come (Caldeira & Wickett, 2003; Hönisch et al., 2012). By protecting sensitive species and ecosystems, refugia could help maintain valuable marine resources and services upon which our society depends (Billé et al., 2013; Gattuso et al., 2015, 2018; McLeod et al., 2013).

How and where to invest in ocean acidification management efforts, including the identification of refugia, remains largely unresolved (Albright et al., 2016; Billé et al., 2013; Gattuso et al., 2018), in part due to the complexity of seawater CO2 chemistry in marine waters (Bates et al., 2018; Hurd, Lenton, Tilbrook, & Boyd, 2018; Strong, Kroeker, Teneva, Mease, & Kelly, 2014). Much like weather and climate on land, seawater conditions vary dramatically over hours to seasons (Waldbusser & Salisbury, 2014). Ocean weather can be thought of as the state of seawater chemistry, temperature, currents, etc. in a location at any given moment in time (Bates et al., 2018). Ocean climate, on the other hand, can be thought of as the average chemical and physical seawater conditions across regions, while small‐scale differences within a climatology can create restricted areas that encapsulate ocean microclimates. Global surface ocean pH climatologies naturally range between pH 8.0 and 8.2 (Bates et al., 2014) and are predicted to decline by >0.4 units if CO2 emissions continue at the current rate (Pörtner et al., 2014). Locally, however, marine ecosystems exhibit seawater acidification rates that differ from what is expected based on atmospheric CO2 forcing alone (Cai et al., 2011; Cyronak, Schulz, Santos, & Eyre, 2014; Feely et al., 2010; Kapsenberg, Alliouane, Gazeau, Mousseau, & Gattuso, 2017; Provoost, Heuven, Soetaert, Laane, & Middelburg, 2010; Wootton, Pfister, & Forester, 2008). This is because many biogeochemical and physical drivers influence local seawater CO2 chemistry (Figure 1, Box 1) and may themselves be influenced by changes to the Earth's climate (e.g., temperature, precipitation, upwelling). Natural variability and interaction of these drivers generate unique variations in seawater CO2 chemistry across marine ecosystems (Chan et al., 2017; Duarte et al., 2013; Hofmann et al., 2011; Waldbusser & Salisbury, 2014), such that marine species, and distinct populations, are likely to encounter different future trajectories depending on their location and habitat (Jury, Thomas, Atkinson, & Toonen, 2013; Kapsenberg, Kelley, Shaw, Martz, & Hofmann, 2015; Kwiatkowski & Orr, 2018; Landschützer, Gruber, Bakker, Stemmler, & Six, 2018; Pacella, Brown, Waldbusser, Labiosa, & Hales, 2018; Shaw, Mcneil, Tilbrook, Matear, & Bates, 2013).

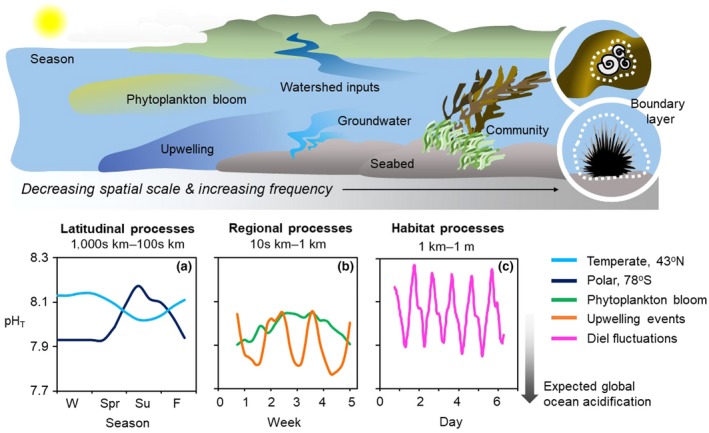

Figure 1.

Processes modifying ocean acidification exposures over a range of temporal frequencies and spatial scales. (a) Seasonal pH regimes driven by warming in a temperate ecosystem and primary production in a polar ecosystem (Kapsenberg, Alliouane, et al., 2017; Kapsenberg et al., 2015). (b) Event‐scale pH variability over a period of 5 weeks. Primary production by a phytoplankton bloom increases pH which decreases upon cessation of the bloom, while periodic upwelling events cause strong decreases in pH (Kapsenberg, 2015; Kapsenberg & Hofmann, 2016). (c) Intense diel pH fluctuations in a coral reef ecosystem driven by benthic photosynthesis and respiration (Cyronak, Santos, et al., 2014). See Box 1 for more details

Box 1. Seawater CO2 chemistry dynamics in marine ecosystems.

1.

An organism's exposure to seawater CO2 chemistry is driven by a hierarchy of biogeochemical and physical processes extending from the open ocean to the organism's boundary layer (Figure 1). The magnitude of contemporary variability in CO2 chemistry is often greater than the end‐century predictions for ocean acidification, which can either amplify or alleviate the harmful exposures associated with anthropogenic ocean acidification (Hofmann et al., 2011). Increasing seawater CO2 concentrations shift chemical equilibria to induce a suite of changes in biologically important parameters such as pH, pCO2, saturation state (Ω), and bicarbonate concentrations ([HCO3 −]), among others (Waldbusser & Salisbury, 2014; Zeebe & Wolf‐Gladrow, 2001). Depending on the driver, CO2 parameters can decouple, complicating estimates of ocean acidification impacts in some ecosystems. For the purposes of this paper, we collectively refer to spatiotemporal variability in one or all of these parameters as variations in seawater “CO2 chemistry.”

Seawater CO2 chemistry is modified seasonally and latitudinally due to differences in solar irradiance and temperature, which can influence the duration of primary production (Racault, Quéré, Buitenhuis, Sathyendranath, & Platt, 2012; Takahashi et al., 2002). For example, seasonal decoupling of pH and aragonite saturation state (Ωar) occurs in the Mediterranean Sea and North Atlantic due to summertime warming (Courtney et al., 2017; Kapsenberg, Alliouane, et al., 2017). In contrast, summertime primary production in the Southern Ocean causes significant increases in both pH and Ωar during seasonal phytoplankton blooms (Kapsenberg et al., 2015; McNeil, Sweeney, & JaE, 2011).

Regional event‐scale processes (few days to a few months) such as phytoplankton blooms (Kapsenberg & Hofmann, 2016), upwelling (Chan et al., 2017), and freshwater contributions from precipitation, runoff, and groundwater (Fassbender, Sabine, & Feifel, 2016) further modify CO2 exposures. Upwelling off of the California coast frequently results in pH exposures below pH 7.8 (Chan et al., 2017; Feely, Sabine, Hernandez‐Ayon, Ianson, & Hales, 2008), while phytoplankton blooms and overall community production can increase pH by 0.1–0.2 units (Frieder, Nam, Martz, & Levin, 2012; Kapsenberg & Hofmann, 2016). Freshwater sources themselves vary drastically in carbonate chemistry, thereby disparately influencing CO2 chemistry dynamics across salinity gradients (Fassbender et al., 2016). For example, freshwater total alkalinity can be either lower or higher than seawater, which can change how watershed inputs impact the surface water CO2 chemistry of nearshore ecosystems (Cyronak, Santos, Erler, Maher, & Eyre, 2014; Millero, Hiscock, Huang, Roche, & Zhang, 2001).

At the habitat scale (1 m–1 km), benthic community metabolism drives diel pH variability via shifts in photosynthesis and respiration (Hendriks et al., 2014; Kapsenberg & Hofmann, 2016). Seabed composition (e.g., calcium carbonate and silicate sediments, hard bottom, etc.) and local hydrology (e.g., tides, currents, residence times, and groundwater) can also influence CO2 chemistry at these scales (Burdige, Hu, & Zimmerman, 2010; Santos, Glud, Maher, Erler, & Eyre, 2011; Zhang, Falter, Lowe, & Ivey, 2012). At the smallest spatial scale (millimeters to centimeters), seawater may be modified within an organism's diffusive boundary layer due to the metabolism of the organism itself (and the host organism for epibionts) along with physical properties that determine the size of the boundary layer, such as benthic structure and flow rates (Hurd et al., 2011; Noisette & Hurd, 2018).

Drivers of CO2 chemistry can interact over frequencies, such that multiple drivers can act together at any given location. The importance of each driver of seawater CO2 chemistry, in terms of exposure, may change through time. For instance, the magnitude of diel variability can vary seasonally (Kapsenberg & Hofmann, 2016; Murray, Malvezzi, Gobler, & Baumann, 2014) and an upwelling event could have overwhelmingly harmful effects on organisms (Barton, Hales, Waldbusser, Langdon, & Feely, 2012; Bednaršek et al., 2012). Taken together, the dynamic nature of CO2 chemistry in marine ecosystems creates unique palettes of exposure in time and space.

The presence of spatial and temporal variability in CO2 chemistry across marine ecosystems has raised the idea that ocean acidification refugia (OAR), or locations where ocean acidification impacts could be less intense, exist naturally (Manzello, Enochs, Melo, Gledhill, & Johns, 2012). Proposed OAR include seagrass meadows and dense algal beds (Hendriks et al., 2014; Krause‐Jensen et al., 2015; Manzello et al., 2012; Unsworth, Collier, Henderson, & Mckenzie, 2012; Wahl et al., 2018; Young & Gobler, 2018), algal boundary layers (Cornwall et al., 2014; Hendriks, Duarte, Marbà, & Krause‐Jensen, 2017; Noisette & Hurd, 2018), mangroves (Sippo, Maher, Tait, Holloway, & Santos, 2016; Yates et al., 2014), slow‐flow habitats (Hurd, 2015), deep‐sea mounts (Tittensor, Baco, Hall‐Spencer, Orr, & Rogers, 2010), areas isolated from upwelling (Chan et al., 2017; Kapsenberg & Hofmann, 2016), and productive high‐latitude environments (Hendriks et al., 2017; Krause‐Jensen et al., 2016). These examples vary dramatically across spatial scales (e.g., a few millimeters in an algal boundary layer to a 100 m2 seagrass bed), with no clear criteria as to what makes each area a potential OAR other than observed transient increases in seawater pH relative to surrounding waters. The lack of a clear, agreed‐upon definition for OAR and criteria for how they must function in the context of climate change makes it difficult for managers, legislators, and scientists to assess where to invest management efforts. In this perspective, we critically evaluate the concept of OAR in the context of organismal exposures to variable CO2 chemistry and propose target refugia for research and management.

2. DEFINING OCEAN ACIDIFICATION REFUGIA

To build a framework for OAR, we turned to the recent interest in phytoremediation as a means for the local mitigation of ocean acidification through photosynthesis (Nielsen et al., 2018; Washington State Blue Ribbon Panel on Ocean Acidification, 2012). Unlike many other global change stressors, the intensity of ocean acidification exposures is directly modified by the metabolism of marine organisms (e.g., respiration and/or photosynthesis), which can add or remove CO2. For example, daytime photosynthesis by seagrass meadows can radically elevate seawater pH across spatial scales of a few millimeters to hundreds of meters (Guilini et al., 2017; Hendriks et al., 2014; Manzello et al., 2012). For this reason, the idea of seagrass ecosystems, and phytoremediation in general, acting as OAR has garnered considerable attention within the scientific community (Hendriks et al., 2014; Manzello et al., 2012; Young & Gobler, 2018), governments (Nielsen et al., 2018; Washington State Blue Ribbon Panel on Ocean Acidification, 2012), and the media (OA‐ICC, 2018). One issue with the concept of seagrass ecosystems acting as OAR is that times of net photosynthesis are accompanied by periods of net respiration on daily and seasonal timescales (Duarte et al., 2010; Unsworth et al., 2012). Therefore, any benefits of periodic relief from ocean acidification exposures due to pH increases during times of net seagrass photosynthesis (e.g., Semesi, Beer, & Björk, 2009) must be critically evaluated against any potential harmful effects due to intensifying exposures that occur in these habitats during times of net respiration (Cyronak et al., 2018; Pacella et al., 2018; Unsworth et al., 2012). Furthermore, the CO2 chemistry in seagrass habitats is influenced by other biogeochemical and physical processes that act over timescales ranging from hours to seasons (Box 1; Duarte et al., 2013). Consequently, the presence of seagrass alone does not guarantee reduced exposure to harmful conditions (Cyronak et al., 2018; Koweek et al., 2018), nor does it necessarily translate to a biological benefit (Greiner, Klinger, Ruesink, Barber, & Horwith, 2018). This disconnect between seawater chemistry and biological impacts highlights the need to create a defining set of criteria that will allow the scientific and management communities to critically evaluate the effectiveness of potential OAR.

We define OAR as any area of the coastal or open ocean that exhibits persistent environmental conditions such that a species' vulnerability to anthropogenic ocean acidification is reduced, where vulnerability is the combination of sensitivity, exposure, and adaptive capacity (Dawson, Jackson, House, Prentice, & Mace, 2011; McLeod et al., 2013; Williams, Shoo, Isaac, Hoffmann, & Langham, 2008). Inherent to this definition is that the local environmental conditions that define the refugium must, (a) provide a significant biological benefit and (b) persist through time, such that a species can outlast anthropogenic ocean acidification across generations. Based on the definition of climate change refugia by Morelli et al. (2016), we reiterate that the size of a refugium must be large enough to manage a small (meta)population. Therefore, we do not consider potential microrefugia wherein seawater chemistry is modified within the boundary layers of photosynthesizing organisms (Flynn et al., 2012; Hendriks et al., 2017; Noisette & Hurd, 2018), even though this could benefit small epiphyte communities (Cox et al., 2017).

Our definition of OAR purposefully allows for environmental factors other than seawater CO2 chemistry to mitigate the harmful impacts of ocean acidification. For example, food supply has been shown to reduce species sensitivity to ocean acidification (Ramajo et al., 2016). In some cases, environmental or ecological interactions, such as competition for light or space, might be more important in driving biological responses rather than CO2 exposures (Barry, Frazer, & Jacoby, 2013; Connell et al., 2017; Garrard et al., 2014). However, as natural variability in seawater CO2 chemistry ultimately drives the severity of ocean acidification exposure and is expected to increase in the future (e.g., Flynn et al., 2012, Jury et al., 2013, Pacella et al., 2018, Shaw et al., 2013), we focus this perspective on the biological impacts of exposure to variable CO2 chemistry. The ocean acidification research community has, over the last few years, made significant progress on this topic (Figure S1; Boyd et al., 2016; Hurd et al., 2018; Rivest, Comeau, & Cornwall, 2017), and the emerging trends could help inform target refugia and management strategies.

3. BIOLOGICAL IMPACTS OF VARIABLE CO2 CHEMISTRY

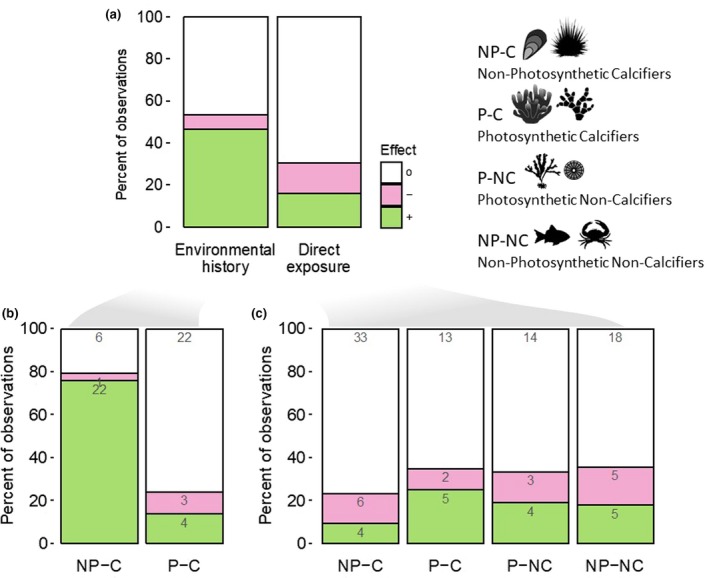

Throughout this paper, we use the term “variable CO2 chemistry” to refer to spatial and temporal changes in the seawater carbon dioxide system (e.g., pCO2, pH, [HCO3 −], Ω, see Box 1). In order to examine how variable CO2 chemistry influences the effectiveness of OAR, we reviewed all studies published through 2018 that assessed the impact of natural CO2 variability on marine species in the context of ocean acidification (see Supporting Information for details). Across a total of 61 studies (Figure S1, Table S1) and 172 observed biological responses, 62% of biological responses exhibited no sensitivity to variability treatments. These studies, however, can be divided into two categories: environmental history or direct exposure, and have different implications for the assessment of OAR.

Environmental history studies used the CO2 variability observed in an organism's habitat to interpret their sensitivity to ocean acidification at a species level. Organisms of the same species, or closely related species, were collected from at least two sites with contrasting variability regimes and were exposed to elevated and stable CO2 conditions simulating future ocean acidification. Environmental history comparisons tested the hypothesis that long‐term exposure (≥1 generation) to variable CO2 conditions enhances the physiological tolerance of populations to ocean acidification. These studies provide information on sensitivity, adaptive capacity, and the potential for evolution on timescales greater than one generation (Dawson et al., 2011; Kelly & Hofmann, 2013; Williams et al., 2008). Studies testing an organism's environmental history demonstrated a positive effect of variability in 47% of the observations, with few observed negative effects (7%, Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Biological responses to CO2 variability in the context of ocean acidification. (a) Responses grouped by experimental design. (b) Responses from environmental history studies only, grouped by mode of life (data not shown: one positive observation each for P‐NC and NP‐NC). (c) Responses from direct exposure studies, grouped by mode of life. Responses are either positive (green, variability mitigates ocean acidification effect), negative (pink, variability exacerbates ocean acidification effect), or neutral (white, variability has no effect). Numbers within bars denote the number of observations

The direct exposure approach used experimental designs where organisms were directly exposed to varying CO2 conditions with present‐day and future mean pH conditions). In contrast to the environmental history approach, direct exposure studies used organisms collected from a single population and tested the hypothesis that biological sensitivity to ocean acidification is altered when the organism is directly exposed to fluctuating conditions under simulated ocean acidification. Such studies provide insight on sensitivity to ocean acidification in the context of local environmental variability. In studies testing direct exposures, a near equal and low percentage of positive (16%) and negative (14%) effects were observed (Figure 2a).

Combined, these results indicate that an organism's long‐term (at least one generation) exposure to harmful conditions has some potential to boost adaptive capacity to ocean acidification, while direct exposure to variability will, in the majority of cases, not alter biological responses. When direct exposure to variability did alter ocean acidification sensitivity, the responses were highly mixed across organisms and biological processes (Figures S2 and S3). Therefore, it is not expected that direct effects of variability will influence biological responses to ocean acidification as much as changes in mean conditions will.

To further explore these trends, we grouped organisms into four categories based on their mode of life (photosynthesizing, calcifying, both, or neither). In environmental history studies, nonphotosynthesizing calcifiers (NP‐C) exhibited an overwhelmingly positive effect, wherein a variable environmental history reduced sensitivity to ocean acidification in 76% of observed biological responses (Figure 2b). Organisms in this category consisted of echinoderms, mollusks, crustaceans, and bryozoans and were predominantly collected from temperate upwelling or riverine‐influenced sites. Echinoderms were the most studied taxa within the environmental history approach (seven papers), with consistent independent observations across species, regions, habitats, and life stages. For example, sea urchin fertilization exhibited increased ocean acidification tolerance associated with CO2 variability in tidepools and upwelling habitats (Kapsenberg, Okamoto, Dutton, & Hofmann, 2017; Moulin, Catarino, Claessens, & Dubois, 2011). Likewise, sea urchin larval growth exhibited reduced ocean acidification sensitivity when parents originated from sites with high and variable CO2 levels (Gaitán‐Espitia et al., 2017; Kelly, Padilla‐Gamiño, & Hofmann, 2013). Similar observations have been made for mollusks, where differences in sensitivities to ocean acidification were correlated with CO2 exposure history (Thomsen et al., 2017; Vargas et al., 2017). Food supply and nutritional status likely play into population‐specific pH sensitivities, but sites of high pH variability with frequent low pH events are not always coupled with high food supply (Kroeker et al., 2016). Taken together, these results provide strong evidence that exposure to CO2 variability has the potential to modulate nonphotosynthesizing calcifiers' sensitivity to ocean acidification and enhance their adaptive capacity (Kelly & Hofmann, 2013).

The observed benefit of variable CO2 history for NP‐C type organisms is in stark contrast to photosynthesizing calcifiers (P‐C). The P‐C group, comprised mostly of temperate and tropical corals and coralline algae, largely exhibited indifference to variability (81% no effect), with a near equal and low number of positive and negative effects (Figure 2b). It may be that P‐C organisms are less influenced by CO2 variability at the habitat scale due to acclimation to large daily CO2 fluctuations that, depending on flow regimes, can occur within their diffusive boundary layers due to the interactive effects of photosynthesis, respiration, and calcification (Gattuso, Allemand, & Frankignoulle, 1999; Hurd et al., 2011). The contrasting responses to ocean acidification sensitivity based on environmental history across different modes of life (i.e., NP‐C compared to P‐C) highlights the need to develop a better mechanistic understanding of how CO2 chemistry is regulated at the cellular level and how changes in environmental conditions alter biological processes.

Contrary to environmental history studies, when organisms were directly exposed to variable CO2 chemistry, no mode of life showed an obvious advantage or disadvantage under simulated ocean acidification (Figure 2c). Direct effects were few (N ≤ 10, combined positive and negative), with the vast majority of biological processes unresponsive to fluctuating CO2 conditions. This indicates that transient increases in pH are unlikely to protect organisms from ocean acidification if there are also transient decreases in pH, especially if the mean pH is no different from the mean pH of the source waters (although there may be exceptions, for example, Jarrold, Humphrey, Mccormick, & Munday, 2017).

Based on this literature review, we can make three broad conclusions. First, in the majority of observations, directly exposing marine organisms to short‐term fluctuations in CO2 chemistry (e.g., hours) does not appear to modulate their biological response to ocean acidification. Therefore, to mitigate ocean acidification impacts via reduced exposures, a substantial increase in mean pH will be necessary, independent of local variability regimes. Second, exposure to variable CO2 conditions over the course of at least one generation may expand a species' adaptive capacity and CO2 tolerance window. Currently, this effect is most apparent in NP‐C organisms from temperate environments. Third, while few, the presence of both positive and negative effects of CO2 variability indicates that ocean acidification impacts could vary from predicted responses in dynamic environments (Figures S2 and S3).

4. OCEAN ACIDIFICATION REFUGIA MANAGEMENT

Our best hope for maintaining biodiversity in a changing climate is by exploiting natural variations in vulnerability, defined as the combination of a species sensitivity, exposure, and adaptive capacity (Dawson et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2008). In this vein, recently proposed ocean management strategies consider management of both environmental exposures, such as reducing CO2 emissions, and biological responses, such as ecosystem restoration or assisted evolution, as potential solutions to mitigate climate change impacts (Gattuso et al., 2018). For ocean acidification impacts, most biological responses were unchanged in the presence of temporal variability in CO2 chemistry (Figure 2c), indicating that responses to mean changes in environmental conditions remain highly relevant (Kroeker et al., 2013). Therefore, temporary pH increases without a substantial change in mean pH (e.g., pH increases associated with primary production over tidal or diel cycles) should not be an identifying criterion for OAR, and reducing global CO2 emissions must remain the primary management activity (Gattuso et al., 2015). However, exposure to variability in CO2 chemistry, specifically low pH events (e.g., days to weeks of low pH exposure driven by upwelling), does seem to reduce vulnerability to ocean acidification by enhancing adaptive capacity. This was most consistently observed for nonphotosynthesizing calcifiers (Figure 2). Based on these results, OAR could help protect species from ocean acidification via one of two mechanisms: (a) modulating exposure to harmful conditions (e.g., areas with sustained high mean pH) or (b) enhancing adaptive capacity (e.g., areas with frequent low pH exposures; Box 2). Because OAR based on mitigating exposures require an increase in mean pH and OAR based on stimulating adaptive capacity require frequent low pH events, these two classes of OAR are mutually exclusive in terms of CO2 variability regimes. However, other mechanisms that reduce a population's vulnerability to ocean acidification (e.g., food supply) could potentially occur in either class of OAR.

Box 2. Ocean acidification refugia definitions and potential examples.

1.

Ocean Acidification Refugia ‐ Areas of the coastal or open ocean that exhibit persistent environmental conditions such that a species' vulnerability to anthropogenic ocean acidification is reduced, where vulnerability is the combination of sensitivity, exposure, and adaptive capacity

| Exposure | Adaptive capacity |

|---|---|

| Spatial refugium | Adaptive refugium |

| An area within a species' biogeographic range that experiences less intense ocean acidification exposure relative to sister populations | An area that enhances a species' adaptive capacity to ocean acidification, often an exposure hotspot |

|

|

| Small‐scale operative refugium | |

| An area that experiences less intense ocean acidification exposure due to purposeful CO2 management | |

|

|

| (!) Refugia dependent on primary producers |

4.1. Ocean acidification refugia based on mitigating exposures

Management of CO2 chemistry exposure (Figure 1) is currently the most common strategy for recently proposed OAR and falls under two categories: spatial refugia and small‐scale operative refugia (Box 2). Based on our literature review and previous biological response studies (Kroeker et al., 2013), any region with a sustained increase in mean seawater pH or that is consistently isolated from corrosive high CO2 conditions has the potential to function as a spatial refugium, regardless of local CO2 variability regimes. While spatial refugia are not isolated from ocean acidification per se, organisms living in these refugia will face better environmental conditions relative to their sister populations that encounter more corrosive conditions, while maintaining connectivity and the potential for genetic exchange. Spatial refugia based on physical characteristics are likely to persist through time. Examples include microclimates such as areas shielded from corrosive upwelling events (Chan et al., 2017; Kapsenberg & Hofmann, 2016) and deep‐sea mounts which isolate organisms from deeper CO2‐rich waters (Tittensor et al., 2010). Spatial refugia based on the biological removal of CO2 potentially exist in hotspots of primary production. For example, in high‐latitude environments, the extended photoperiod and high nutrient levels maintain primary production and high pH for several months in summer (Duarte & Krause‐Jensen, 2018; Havenhand et al., 2018; Kapsenberg et al., 2015; Krause‐Jensen et al., 2016). Like other spatial refugia, high‐latitude environments are not isolated from ocean acidification and are actually considered one of the most vulnerable ecosystems due to naturally cold, CO2‐rich waters (Orr et al., 2005). So far, we are unaware of studies that have tested the hypothesis that seasonally restricted high pH benefits an organism's sensitivity to ocean acidification. Nonetheless, primary production hotspots could function as spatial refugia if high pH levels are sustainable for a period of biological significance relative to areas with lower primary productivity.

Exposure can also be managed directly in small‐scale operative refugia (Box 2). Purposeful modification of seawater CO2 chemistry will be most feasible in easily accessible coastal locations and for target economic purposes, such as aquaculture or small‐scale reef management (Mongin, Baird, Hadley, & Lenton, 2016). Phytoremediation, or modification of seawater CO2 chemistry by seagrass, kelp, or algae cultivated alongside ocean acidification‐sensitive organisms, is an active area of research (Young & Gobler, 2018). However, its effectiveness in the field has significant limitations (Greiner et al., 2018; Mongin et al., 2016), and additional bubble stripping of high nighttime CO2 levels in macrophyte beds may be necessary to ensure that the overall mean pH is significantly elevated when compared to that of surrounding waters (Koweek, Mucciarone, & Dunbar, 2016). Nighttime bubbling with air may be particularly effective in slow‐flow environments where diel pH cycles can be large (Hurd, 2015). Even if a substantial increase in mean pH is achieved, use of marine vegetation as the basis of small‐scale operative refugia must be evaluated in the context of seasonal changes in primary production (Duarte et al., 2010; Unsworth et al., 2012). Artificial ocean alkalization is another method currently under evaluation aimed at directly modifying exposures (Gattuso et al., 2018; Ilyina, Wolf‐Gladrow, Munhoven, & Heinze, 2013; Renforth & Henderson, 2017). Increasing total alkalinity may be achieved by adding crushed shells or concrete to key habitats, which then through dissolution causes an increase in seawater calcium carbonate saturation state (Green, Waldbusser, Hubazc, Cathcart, & Hall, 2013; Green, Waldbusser, Reilly, Emerson, & O'donnell S, 2009; Greiner et al., 2018; Mos, Dworjanyn, Mamo, & Kelaher, 2019). The effectiveness of passive calcium carbonate dissolution in mitigating biological impacts in the field will be highly dependent on local hydrology and is potentially restricted to specific biological processes in small boundary layers or shallow sediments (Green et al., 2013, 2009; Mos et al., 2019).

Regardless of the exact method, management of small‐scale operative refugia will require intense resource investment in the form of engineering, maintenance, restoration, monitoring, and funding. A priori knowledge of the local environment will be necessary to choose where to implement such efforts so that other coastal drivers, such as groundwater, terrestrial runoff, or high flow rates (Figure 1) do not wash away or neutralize the expected benefits of the management approach. Watershed inputs, including surface runoff, groundwater, excess nutrients and other materials, may need to be included in the management plan in order to achieve the management goals of the refugium. The long‐term persistence of small‐scale operative refugia will largely depend on the duration of resource investments. For phytoremediation specifically, additional management costs may be required to protect macrophytes from other climate change impacts such as marine heat waves (Arias‐Ortiz et al., 2018; Filbee‐Dexter, Feehan, & Scheibling, 2016). While purposeful local management of CO2 chemistry to protect target marine resources, such as aquaculture or small reefs, could offer short‐term benefits for a few years (Mongin et al., 2016), OAR based on physical features (e.g., some spatial refugia) may function for a much longer time period.

4.2. Ocean acidification refugia based on enhancing adaptive capacity

Intense variability in CO2 chemistry, specifically exposure to frequent low pH events (e.g., days to weeks), can enhance adaptive capacity, suggesting that OAR may also exist as adaptive refugia in “exposure hotspots” (Chan et al., 2017; Box 2). Rather than managing exposures, adaptive refugia reduce a species' vulnerability to ocean acidification by enhancing their potential to adapt to changing conditions (Dawson et al., 2011). Based on our literature review, enhancing adaptive capacity is currently the most likely means by which variable seawater CO2 chemistry can mitigate ocean acidification impacts. So far, this appears most effective for NP‐C type organisms in temperate ecosystems (Figure 2b), although research in other biomes is lacking. Adaptive capacity can potentially accrue via changes in physiological plasticity, epigenetics, genetics, or a combination thereof (Hoffmann & Sgrò, 2011; Hofmann, 2017). The benefit of intermittent exposure to low pH, such as that associated with upwelling, is likely influenced by frequency and duration of the low pH events, generation time, and life history of the organism (Boyd et al., 2016). For management, marine protected areas encompassing adaptive refugia could help protect and maximize the genetic diversity necessary for adaptation and dispersal, while reducing other local stressors (Bernhardt & Leslie, 2013; Roberts et al., 2017).

Like spatial refugia, adaptive refugia are not isolated from ocean acidification and local adaptation is unlikely to provide complete resistance to ocean acidification (Gaitán‐Espitia et al., 2017; Kelly et al., 2013). The increasingly harmful low pH and calcium carbonate undersaturation associated with ocean acidification at exposure hotspots may ultimately challenge the persistence of a local population (Hauri et al., 2009). Thus, adaptive refugia must last long enough to generate and disperse adaptive geno‐ or phenotypes elsewhere. This duration will be influenced by species‐specific characteristics such as life history and rates of adaptation. Ideally, adaptive refugia should encompass source populations that disperse to spatial refugia where ocean acidification effects are less intense. Understanding population connectivity, and how it might be altered by global change, will be an important aspect of deciding where to invest climate change management efforts (Magris, Pressey, Weeks, & Ban, 2014; Palumbi, 2003). For example, resource investment at sites with sink populations, where the persistence of the population depends on immigration from reproductive populations elsewhere, could be futile. Ocean acidification itself could alter a species' ability to successfully disperse to new habitats. For example, the ability for larval clownfish to detect settlement cues is diminished under simulated ocean acidification (Munday et al., 2009, but see also Jarrold et al., 2017). While dispersal of adapted genotypes to a favorable new location may happen naturally by chance, management of key species could help facilitate this process in a controlled manner via assisted evolution or migration (Hoegh‐Guldberg et al., 2008; van Oppen et al., 2017; van Oppen, Oliver, Putnam, & Gates, 2015). As a conservation strategy, assisted migration has been debated due to difficulties in predicting unintended consequences of introducing species to new habitats outside of their natural range (Ricciardi & Simberloff, 2009). In the ocean, however, there is a high chance of finding spatial refugia within the existing biogeographic range of a species due to the vast spatiotemporal heterogeneity of seawater CO2 chemistry within ocean microclimates (Chan et al., 2017; Kapsenberg & Hofmann, 2016; Vargas et al., 2017). Assisted migration across OAR combines management actions addressing both adaptive capacity and exposure, and may be particularly beneficial to sensitive species with a large biogeographic range but small dispersal distance.

4.3. Management guidelines

Management guidelines for land‐based climate change refugia can readily be applied to the marine realm. A step‐by‐step workflow, developed by Morelli et al. (2016) and adapted for OAR is as follows: (1) Identify clear management goals, which includes pinpointing the organism and biological process of interest for conservation. (2) Assess vulnerability of the target resource as a function of sensitivity, exposure, and adaptive capacity. This will require knowledge and integration of environmental variability in biological experiments either by using the existing literature or designing new studies, which will be ambitious beyond the scope of an individual species or marine resource. (3) Revise management goals based on the vulnerability assessment in Step 2. (4) Identify locations of potential refugia based on historical, environmental, modeling, and biological data. Evaluate if these conditions support the management goals and are likely to persist through the expected duration of anthropogenic ocean acidification or need of the target marine resource. (5) Prioritize refugia for management by evaluating other benefits of its location, such as overlap with other vulnerable resources, existing marine protected areas, and site accessibility. (6) Identify and implement management actions. (7) Monitor refugia and adjust management actions to maintain management goals.

For OAR, spatial and adaptive refugia have the potential to target multiple species at once. From a practical perspective, priority locations for OAR research could, therefore, be chosen based on existing marine protected areas that exhibit the right environmental characteristics. Inter‐ and intraspecific vulnerability assessments will be necessary to assess management goals. For example, the environmental conditions that shape adaptive refugia for sea urchins can be harmful to the early development and aquaculture production of oysters (Barton et al., 2012). Small‐scale operative refugia will most likely benefit a target marine resource or species. As some biological responses showed negative responses to CO2 variability regimes (14%), inclusion of CO2 variability remains an important aspect of vulnerability assessments, especially for refugia targeting a single species. Temporal variability in seawater CO2 chemistry can differentially affect biological processes even within the same life history stage (Kapsenberg et al., 2018), and an understanding of vulnerability through life stages may also be necessary. Organisms are likely to encounter a range of stressors within their environments, and CO2 chemistry may not be the predominant one. For example, mortality in shellfish aquaculture is driven by ocean acidification in the Northeast Pacific upwelling system (Barton et al., 2015), summer heat stress in the Ebro Delta on the Spanish Mediterranean coast (M. Fernández, pers. comm.), and salinity stress associated with extreme events (Cheng, Chang, Deck, & Ferner, 2016). Therefore, if a refugium is targeting ocean acidification impacts, it is important to determine that changes in CO2 chemistry represent a primary stressor. Once an OAR has been identified, several ocean management actions can be implemented to improve overall ecosystem health (Gattuso et al., 2018), regardless if one is managing for exposure or adaptive capacity. Effective OAR management will require a holistic view of ecosystems, encompassing the diverse array of processes that alter CO2 chemistry (Figure 1, Box 1) and may often require the coordination of several management actions operating across disciplines.

4.4. Considerations for future research

As research will play a large role in identifying OAR, we briefly highlight two general knowledge gaps in ocean acidification biology. First, identifying OAR in a specific area requires knowing to which aspect of CO2 chemistry (e.g., pH, pCO2, Ω) the target organism and biological process are sensitive and how those parameters are expected to change over time. The latter can be achieved with high spatiotemporal resolution of oceanographic measurements and modeling (Chan et al., 2017; Cyronak et al., 2018; Koweek et al., 2018; Krause‐Jensen et al., 2015). However, for most all biological processes, the mechanism and reaction norm (i.e., sensitivity measured across a wide range of exposures) by which a specific parameter of CO2 chemistry affects an organism remains unclear (Bach, 2015; Cyronak, Schulz, & Jokiel, 2016; Hendriks et al., 2015). Different CO2 parameters can differentially influence various biological processes, even within a single species (Waldbusser et al., 2015). Identifying mechanisms of biological sensitivity to changes in CO2 chemistry is especially important for coastal areas where various CO2 parameters can decouple due to changes in temperature and salinity driven by watershed inputs (Box 1; Fassbender et al., 2016; Waldbusser & Salisbury, 2014).

Second, once the driver of ocean acidification sensitivity is known for a given species it will be easier to design and interpret experiments assessing impacts of multiple stressors (Boyd et al., 2018). This research should be conducted in a way that complements the environmental variability that is observed in an organism's environment. Parameters such as salinity, oxygen, and temperature can exhibit large natural spatial and temporal variability, and multiple stressors do not necessarily occur synchronously in time (Gunderson, Armstrong, & Stillman, 2016). For example, diel processes can result in asynchronous warming and acidification stress on coral reefs (Kline et al., 2015). Exposure to multiple stressors is not always a simple scenario of warming and acidification, and local variability regimes may be more important than changes in global means (Boch et al., 2018; Boyd et al., 2018; Reum et al., 2016). For instance, some studies show negative effects of pH variability only when low pH coincides with instances of hypoxia (Gobler, Clark, Griffith, & Lusty, 2017; Lifavi, Targett, & Grecay, 2017). Successful research in the area of OAR will require multidisciplinary approaches that aim to not only determine functional relationships, but create mechanistic understandings of how biological processes respond to local environmental conditions in the context of ocean acidification.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In the marine realm, dynamic CO2 variability provides the opportunity for local ocean acidification management by taking advantage of natural heterogeneity in species vulnerability. Specifically, OAR based on seawater CO2 chemistry can either (a) reduce exposure to harmful conditions via sustained elevated mean pH or (b) boost adaptive capacity via frequent exposure to low and variable pH. While rapid and sweeping international reduction in CO2 emissions should remain the primary goal, local management of ocean acidification may be necessary to ensure the persistence of marine ecosystem services and resources. With this in mind, we outline some of the most important considerations moving forward:

When assessing the effectiveness of OAR, environmental conditions must be connected to a biological benefit such that a species overall vulnerability to ocean acidification is reduced.

OAR based on exposure, whether natural (spatial refugia) or purposeful (small‐scale operative refugia), must exhibit a significant and sustained increase in mean pH compared to that of the surrounding waters, regardless of temporal variability regimes.

OAR that boost adaptive capacity (adaptive refugia) are most likely to be found at areas with frequent low pH events and intense CO2 variability (i.e., exposure hotspots). As of now, the potential of adaptive refugia is largely based on evidence from nonphotosynthesizing calcifiers in temperate marine ecosystems.

Characteristics of the refugia must persist through time, such that the target species can endure for the duration of anthropogenic ocean acidification or necessity of the marine resource (e.g., aquaculture). This is particularly important when assessing exposure‐based OAR reliant on primary production.

Marine protected areas will likely support the effectiveness of any OAR by reducing other local stressors (e.g., pollution, habitat destruction) and maximizing genetic diversity and healthy, large populations (Roberts et al., 2017).

Future research on the mechanistic understanding of ocean acidification sensitivity and variability in multistressor exposures will advance the assessment and implementation of OAR. This may require consideration of an organism's full life history.

This perspective is not meant to provide a definitive list of local ocean acidification management options. Rather, the ideas outlined here are intended to apply the current research to management actions. There will be a finite source of time, funding, and effort to implement any local management action, and it is important to develop clear goals and assess the potential return on investment. For example, while phytoremediation may seem like a “no regrets” investment due to other ecological benefits (Nielsen et al., 2018), resources that go into these efforts with the intention of combating ocean acidification may fall short of desired objectives. Research on OAR remains a hot topic, but an effective way forward requires the synthesis of multidisciplinary research that integrates interdisciplinary perspectives from the organism to the ecosystem, alongside targeted and goal‐oriented management planning. Ultimately, the local management of global change represents an immensely challenging endeavor, and successful enterprises will require synergy between interdisciplinary science and feasible management actions.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work is a contribution to European Commission Horizon 2020 Marie Skłodowska‐Curie Action (no. 747637) awarded to LK.

Kapsenberg L, Cyronak T. Ocean acidification refugia in variable environments. Glob Change Biol. 2019;25:3201–3214. 10.1111/gcb.14730

REFERENCES

- Albright, R. , Anthony, K. R. N. , Baird, M. , Beeden, R. , Byrne, M. , Collier, C. , … Abal, E. (2016). Ocean acidification: Linking science to management solutions using the Great Barrier Reef as a case study. Journal of Environmental Management, 182, 641–650. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.07.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias‐Ortiz, A. , Serrano, O. , Masqué, P. , Lavery, P. S. , Mueller, U. , Kendrick, G. A. , … Duarte, C. M. (2018). A marine heatwave drives massive losses from the world's largest seagrass carbon stocks. Nature Climate Change, 8, 338–344. 10.1038/s41558-018-0096-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft, M. B. (2010). Identifying refugia from climate change. Journal of Biogeography, 37, 1407–1413. 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2010.02300.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bach, L. T. (2015). Reconsidering the role of carbonate ion concentration in calcification by marine organisms. Biogeosciences, 12, 4939–4951. 10.5194/bg-12-4939-2015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barry, S. C. , Frazer, T. K. , & Jacoby, C. A. (2013). Production and carbonate dynamics of Halimeda incrassata (Ellis) Lamouroux altered by Thalassia testudinum Banks and Soland ex König. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 444, 73–80. 10.1016/j.jembe.2013.03.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton, A. , Hales, B. , Waldbusser, G. G. , Langdon, C. , & Feely, R. A. (2012). The Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas, shows negative correlation to naturally elevated carbon dioxide levels: Implications for near‐term ocean acidification effects. Limnology and Oceanography, 57, 698–710. 10.4319/lo.2012.57.3.0698 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barton, A. , Waldbusser, G. , Feely, R. , Weisberg, S. , Newton, J. , Hales, B. , … McLauglin, K. (2015). Impacts of coastal acidification on the Pacific Northwest shellfish industry and adaptation strategies implemented in response. Oceanography, 28, 146–159. 10.5670/oceanog.2015.38 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bates, A. E. , Helmuth, B. , Burrows, M. T. , Duncan, M. I. , Garrabou, J. , Guy‐Haim, T. , … Rilov, G. (2018). Biologists ignore ocean weather at their peril. Nature, 560, 299–301. 10.1038/d41586-018-05869-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates, N. , Astor, Y. , Church, M. , Currie, K. , Dore, J. , Gonaález‐Dávila, M. , … Santa‐Casiano, M. (2014). A time‐series view of changing ocean chemistry due to ocean uptake of anthropogenic CO2 and ocean acidification. Oceanography, 27, 126–141. 10.5670/oceanog.2014.16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bednaršek, N. , Tarling, G. A. , Bakker, D. C. E. , Fielding, S. , Jones, E. M. , Venables, H. J. , … Murphy, E. J. (2012). Extensive dissolution of live pteropods in the Southern Ocean. Nature Geoscience, 5, 881–885. 10.1038/ngeo1635 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt, J. R. , & Leslie, H. M. (2013). Resilience to climate change in coastal marine ecosystems. Annual Review of Marine Science, 5, 371–392. 10.1146/annurev-marine-121211-172411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billé, R. , Kelly, R. , Biastoch, A. , Harrould‐Kolieb, E. , Herr, D. , Joos, F. , … Gattuso, J.‐P. (2013). Taking action against ocean acidification: A review of management and policy options. Environmental Management, 52, 761–779. 10.1007/s00267-013-0132-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boch, C. A. , Micheli, F. , AlNajjar, M. , Monismith, S. G. , Beers, J. M. , Bonilla, J. C. , … Woodson, C. B. (2018). Local oceanographic variability influences the performance of juvenile abalone under climate change. Scientific Reports, 8, 5501 10.1038/s41598-018-23746-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, P. W. , Collins, S. , Dupont, S. , Fabricius, K. , Gattuso, J.‐P. , Havenhand, J. , … Pörtner, H.‐O. (2018). Experimental strategies to assess the biological ramifications of multiple drivers of global ocean change—A review. Global Change Biology, 24, 2239–2261. 10.1111/gcb.14102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, P. W. , Cornwall, C. E. , Davison, A. , Doney, S. C. , Fourquez, M. , Hurd, C. L. , … McMinn, A. (2016). Biological responses to environmental heterogeneity under future ocean conditions. Global Change Biology, 22, 2633–2650. 10.1111/gcb.13287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdige, D. J. , Hu, X. , & Zimmerman, R. C. (2010). The widespread occurrence of coupled carbonate dissolution/reprecipitation in surface sediments on the Bahamas Bank. American Journal of Science, 310, 492 10.2475/06.2010.03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.‐J. , Hu, X. , Huang, W.‐J. , Murrell, M. C. , Lehrter, J. C. , Lohrenz, S. E. , … Gong, G.‐C. (2011). Acidification of subsurface coastal waters enhanced by eutrophication. Nature Geoscience, 4, 766–770. 10.1038/ngeo1297 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira, K. , & Wickett, M. E. (2003). Anthropogenic carbon and ocean pH. Nature, 425, 365–365. 10.1038/425365a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, F. , Barth, J. A. , Blanchette, C. A. , Byrne, R. H. , Chavez, F. , Cheriton, O. , … Washburn, L. (2017). Persistent spatial structuring of coastal ocean acidification in the California Current System. Scientific Reports, 7, 2526 10.1038/s41598-017-02777-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B. S. , Chang, A. L. , Deck, A. , & Ferner, M. C. (2016). Atmospheric rivers and the mass mortality of wild oysters: Insight into an extreme future? Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 283, 20161462 10.1098/rspb.2016.1462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell, S. D. , Doubleday, Z. A. , Hamlyn, S. B. , Foster, N. R. , Harley, C. D. G. , Helmuth, B. , … Russell, B. D. (2017). How ocean acidification can benefit calcifiers. Current Biology, 27, R95–R96. 10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall, C. E. , Boyd, P. W. , McGraw, C. M. , Hepburn, C. D. , Pilditch, C. A. , Morris, J. N. , … Hurd, C. L. (2014). Diffusion boundary layers ameliorate the negative effects of ocean acidification on the temperate coralline macroalga Arthrocardia corymbosa . PLoS ONE, 9, e97235 10.1371/journal.pone.0097235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney, T. A. , Lebrato, M. , Bates, N. R. , Collins, A. , de Putron, S. J. , Garley, R. , … Andersson, A. J. (2017). Environmental controls on modern scleractinian coral and reef‐scale calcification. Science Advances, 3, e1701356 10.1126/sciadv.1701356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, T. E. , Nash, M. , Gazeau, F. , Déniel, M. , Legrand, E. , Alliouane, S. , … Martin, S. (2017). Effects of in situ CO2 enrichment on Posidonia oceanica epiphytic community composition and mineralogy. Marine Biology, 164, 103 10.1007/s00227-017-3136-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cyronak, T. , Andersson, A. J. , D'Angelo, S. , Bresnahan, P. , Davidson, C. , Griffin, A. , … White, M. (2018). Short‐term spatial and temporal carbonate chemistry variability in two contrasting seagrass meadows: Implications for pH buffering capacities. Estuaries and Coasts, 41, 1282–1296. 10.1007/s12237-017-0356-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cyronak, T. , Santos, I. R. , Erler, D. V. , Maher, D. T. , & Eyre, B. D. (2014). Drivers of pCO2 variability in two contrasting coral reef lagoons: The influence of submarine groundwater discharge. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 28, 398–414. [Google Scholar]

- Cyronak, T. , Schulz, K. G. , & Jokiel, P. L. (2016). The Omega myth: What really drives lower calcification rates in an acidifying ocean. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 73, 558–562. 10.1093/icesjms/fsv075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cyronak, T. , Schulz, K. G. , Santos, I. R. , & Eyre, B. D. (2014). Enhanced acidification of global coral reefs driven by regional biogeochemical feedbacks. Geophysical Research Letters, 41, 5538–5546. 10.1002/2014GL060849 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, T. P. , Jackson, S. T. , House, J. I. , Prentice, I. C. , & Mace, G. M. (2011). Beyond predictions: Biodiversity conservation in a changing climate. Science, 332, 53–58. 10.1126/science.1200303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doney, S. C. , Fabry, V. J. , Feely, R. A. , & Kleypas, J. A. (2009). Ocean acidification: The other CO2 problem. Annual Review of Marine Science, 1, 169–192. 10.4319/lol.2011.rfeely_sdoney.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doney, S. C. , Ruckelshaus, M. , Emmett Duffy, J. , Barry, J. P. , Chan, F. , English, C. A. , … Talley, L. D. (2012). Climate change impacts on marine ecosystems. Annual Review of Marine Science, 4, 11–37. 10.1146/annurev-marine-041911-111611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, C. M. , Hendriks, I. E. , Moore, T. S. , Olsen, Y. S. , Steckbauer, A. , Ramajo, L. , … McCulloch, M. (2013). Is ocean acidification an open‐ocean syndrome? Understanding anthropogenic impacts on seawater pH. Estuaries and Coasts, 36, 221–236. 10.1007/s12237-013-9594-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, C. M. , & Krause‐Jensen, D. (2018). Greenland tidal pools as hot spots for ecosystem metabolism and calcification. Estuaries and Coasts, 41, 1314–1321. 10.1007/s12237-018-0368-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, C. M. , Marbà, N. , Gacia, E. , Fourqurean, J. W. , Beggins, J. , Barrón, C. , & Apostolaki, E. T. (2010). Seagrass community metabolism: Assessing the carbon sink capacity of seagrass meadows. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 24, 1–8. 10.1029/2010GB003793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fassbender, A. J. , Sabine, C. L. , & Feifel, K. M. (2016). Consideration of coastal carbonate chemistry in understanding biological calcification. Geophysical Research Letters, 43, 4467–4476. 10.1002/2016GL068860 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feely, R. A. , Alin, S. R. , Newton, J. , Sabine, C. L. , Warner, M. , Devol, A. , … Maloy, C. (2010). The combined effects of ocean acidification, mixing, and respiration on pH and carbonate saturation in an urbanized estuary. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 88, 442–449. 10.1016/j.ecss.2010.05.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feely, R. A. , Sabine, C. L. , Hernandez‐Ayon, J. M. , Ianson, D. , & Hales, B. (2008). Evidence for upwelling of corrosive "acidified" water onto the continental shelf. Science, 320, 1490–1492. 10.1126/science.1155676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filbee‐Dexter, K. , Feehan, C. J. , & Scheibling, R. E. (2016). Large‐scale degradation of a kelp ecosystem in an ocean warming hotspot. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 543, 141–152. 10.3354/meps11554 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, K. J. , Blackford, J. C. , Baird, M. E. , Raven, J. A. , Clark, D. R. , Beardall, J. , … Wheeler, G. L. (2012). Changes in pH at the exterior surface of plankton with ocean acidification. Nature Climate Change, 2, 510 10.1038/nclimate1489 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frieder, C. A. , Nam, S. H. , Martz, T. R. , & Levin, L. A. (2012). High temporal and spatial variability of dissolved oxygen and pH in a nearshore California kelp forest. Biogeosciences, 9, 3917–3930. 10.5194/bg-9-3917-2012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaitán‐Espitia, J. D. , Villanueva, P. A. , Lopez, J. , Torres, R. , Navarro, J. M. , & Bacigalupe, L. D. (2017). Spatio‐temporal environmental variation mediates geographical differences in phenotypic responses to ocean acidification. Biology Letters, 13, 20160865 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrard, S. L. , Gambi, M. C. , Scipione, M. B. , Patti, F. P. , Lorenti, M. , Zupo, V. , … Buia, M. C. (2014). Indirect effects may buffer negative responses of seagrass invertebrate communities to ocean acidification. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 461, 31–38. 10.1016/j.jembe.2014.07.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gattuso, J.‐P. , Allemand, D. , & Frankignoulle, M. (1999). Photosynthesis and calcification at cellular, organismal and community levels in coral reefs: A review on interactions and control by carbonate chemistry. American Zoologist, 39, 160–183. 10.1093/icb/39.1.160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gattuso, J.‐P. , Magnan, A. , Billé, R. , Cheung, W. W. , Howes, E. L. , Joos, F. , … Turley, C. (2015). Contrasting futures for ocean and society from different anthropogenic CO2 emissions scenarios. Science, 349, aac4722 10.1126/science.aac4722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattuso, J.‐P. , Magnan, A. K. , Bopp, L. , Cheung, W. W. L. , Duarte, C. M. , Hinkel, J. , … Rau, G. H. (2018). Ocean solutions to address climate change and its effects on marine ecosystems. Frontiers in Marine Science, 5, 337 10.3389/fmars.2018.00337 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gobler, C. J. , Clark, H. R. , Griffith, A. W. , & Lusty, M. W. (2017). Diurnal fluctuations in acidification and hypoxia reduce growth and survival of larval and juvenile bay scallops (Argopecten irradians) and hard clams (Mercenaria mercenaria). Frontiers in Marine Science, 3, 282 10.3389/fmars.2016.00282 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green, M. A. , Waldbusser, G. G. , Hubazc, L. , Cathcart, E. , & Hall, J. (2013). Carbonate mineral saturation state as the recruitment cue for settling bivalves in marine muds. Estuaries and Coasts, 36, 18–27. 10.1007/s12237-012-9549-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green, M. A. , Waldbusser, G. G. , Reilly, S. L. , Emerson, K. , & O'donnell, S. (2009). Death by dissolution: Sediment saturation state as a mortality factor for juvenile bivalves. Limnology and Oceanography, 54, 1037–1047. 10.4319/lo.2009.54.4.1037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner, C. M. , Klinger, T. , Ruesink, J. L. , Barber, J. S. , & Horwith, M. (2018). Habitat effects of macrophytes and shell on carbonate chemistry and juvenile clam recruitment, survival, and growth. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 509, 8–15. 10.1016/j.jembe.2018.08.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guilini, K. , Weber, M. , de Beer, D. , Schneider, M. , Molari, M. , Lott, C. , … Vanreusel, A. (2017). Response of Posidonia oceanica seagrass and its epibiont communities to ocean acidification. PLoS ONE, 12, e0181531 10.1371/journal.pone.0181531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson, A. R. , Armstrong, E. J. , & Stillman, J. H. (2016). Multiple stressors in a changing world: The need for an improved perspective on physiological responses to the dynamic marine environment. Annual Review of Marine Science, 8, 357–378. 10.1146/annurev-marine-122414-033953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauri, C. , Gruber, N. , Plattner, G.‐K. , Alin, S. , Feely, R. A. , Hales, B. , & Wheeler, P. A. (2009). Ocean acidification in the California Current System. Oceanography, 22, 60–71. 10.5670/oceanog.2009.97 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Havenhand, J. N. , Filipsson, H. L. , Niiranen, S. , Troell, M. , Crépin, A. S. , Jagers, S. , & Anderson, L. G. (2018). Ecological and functional consequences of coastal ocean acidification: Perspectives from the Baltic‐Skagerrak System. Ambio, 48(8), 831–854. 10.1007/s13280-018-1110-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, I. E. , Duarte, C. M. , Marbà, N. , & Krause‐Jensen, D. (2017). pH gradients in the diffusive boundary layer of subarctic macrophytes. Polar Biology, 40, 2343–2348. 10.1007/s00300-017-2143-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, I. E. , Duarte, C. M. , Olsen, Y. S. , Steckbauer, A. , Ramajo, L. , Moore, T. S. , … McCulloch, M. (2015). Biological mechanisms supporting adaptation to ocean acidification in coastal ecosystems. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 152, A1–A8. 10.1016/j.ecss.2014.07.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, I. E. , Olsen, Y. S. , Ramajo, L. , Basso, L. , Steckbauer, A. , Moore, T. S. , … Duarte, C. M. (2014). Photosynthetic activity buffers ocean acidification in seagrass meadows. Biogeosciences, 11, 333–346. 10.5194/bg-11-333-2014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoegh‐Guldberg, O. , & Bruno, J. F. (2010). The impact of climate change on the world's marine ecosystems. Science, 328, 1523–1528. 10.1126/science.1189930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoegh‐Guldberg, O. , Hughes, L. , Mcintyre, S. , Lindenmayer, D. B. , Parmesan, C. , Possingham, H. P. , & Thomas, C. D. (2008). Assisted colonization and rapid climate change. Science, 321, 345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, A. A. , & Sgrò, C. M. (2011). Climate change and evolutionary adaptation. Nature, 470, 479–485. 10.1038/nature09670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, G. E. (2017). Ecological epigenetics in marine metazoans. Frontiers in Marine Science, 4, 4 10.3389/fmars.2017.00004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, G. E. , Smith, J. E. , Johnson, K. S. , Send, U. , Levin, L. A. , Micheli, F. , … Martz, T. R. (2011). High‐frequency dynamics of ocean pH: A multi‐ecosystem comparison. PLoS ONE, 6, e28983 10.1371/journal.pone.0028983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honisch, B. , Ridgwell, A. , Schmidt, D. N. , Thomas, E. , Gibbs, S. J. , Sluijs, A. , … Williams, B. (2012). The geological record of ocean acidification. Science, 335, 1058–1063. 10.1126/science.1208277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd, C. L. (2015). Slow‐flow habitats as refugia for coastal calcifiers from ocean acidification. Journal of Phycology, 51, 599–605. 10.1111/jpy.12307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd, C. L. , Cornwall, C. E. , Currie, K. , Hepburn, C. D. , Mcgraw, C. M. , Hunter, K. A. , & Boyd, P. W. (2011). Metabolically induced pH fluctuations by some coastal calcifiers exceed projected 22nd century ocean acidification: A mechanism for differential susceptibility? Global Change Biology, 17, 3254–3262. 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02473.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd, C. L. , Lenton, A. , Tilbrook, B. , & Boyd, P. W. (2018). Current understanding and challenges for oceans in a higher‐CO2 world. Nature Climate Change, 8, 686–694. 10.1038/s41558-018-0211-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ilyina, T. , Wolf‐Gladrow, D. , Munhoven, G. , & Heinze, C. (2013). Assessing the potential of calcium‐based artificial ocean alkalinization to mitigate rising atmospheric CO2 and ocean acidification. Geophysical Research Letters, 40, 5909–5914. 10.1002/2013gl057981 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC . (2014). Climate change 2014: Synthesis report In Core Writing Team , Pachauri R. K., & Meyer L. A. (Eds.), Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (pp. 1–151). Geneva, Switzerland: IPCC. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrold, M. D. , Humphrey, C. , Mccormick, M. I. , & Munday, P. L. (2017). Diel CO2 cycles reduce severity of behavioural abnormalities in coral reef fish under ocean acidification. Scientific Reports, 7, 10153 10.1038/s41598-017-10378-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jury, C. , Thomas, F. , Atkinson, M. , & Toonen, R. (2013). Buffer capacity, ecosystem feedbacks, and seawater chemistry under global change. Water, 5(3), 1303–1325. 10.3390/w5031303 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kapsenberg, L. (2015). Data to accompany “Exploring the Complexity of Ocean Acidification: An Ecosystem Comparison of Coastal pH Variability”. Santa Barbara Coastal LTER.

- Kapsenberg, L. , Alliouane, S. , Gazeau, F. , Mousseau, L. , & Gattuso, J. P. (2017). Coastal ocean acidification and increasing total alkalinity in the northwestern Mediterranean Sea. Ocean Science, 13, 411–426. 10.5194/os-13-411-2017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kapsenberg, L. , & Hofmann, G. E. (2016). Ocean pH time‐series and drivers of variability along the northern Channel Islands, California, USA. Limnology and Oceanography, 61, 953–968. 10.1002/lno.10264 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kapsenberg, L. , Kelley, A. L. , Shaw, E. C. , Martz, T. R. , & Hofmann, G. E. (2015). Near‐shore Antarctic pH variability has implications for biological adaptation to ocean acidification. Scientific Reports, 5, 9638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapsenberg, L. , Miglioli, A. , Bitter, M. C. , Tambutté, E. , Dumollard, R. , & Gattuso, J. P. (2018). Ocean pH fluctuations affect mussel larvae at key developmental transitions. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 285, 20182381 10.1098/rspb.2018.2381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapsenberg, L. , Okamoto, D. K. , Dutton, J. M. , & Hofmann, G. E. (2017). Sensitivity of sea urchin fertilization to pH varies across a natural pH mosaic. Ecology and Evolution, 7, 1737–1750. 10.1002/ece3.2776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, M. W. , & Hofmann, G. E. (2013). Adaptation and the physiology of ocean acidification. Functional Ecology, 27, 980–990. 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.02061.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, M. W. , Padilla‐Gamiño, J. L. , & Hofmann, G. E. (2013). Natural variation and the capacity to adapt to ocean acidification in the keystone sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus . Global Change Biology, 19, 2536–2546. 10.1111/gcb.12251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppel, G. , Van Niel, K. P. , Wardell‐Johnson, G. W. , Yates, C. J. , Byrne, M. , Mucina, L. , … Franklin, S. E. (2012). Refugia: Identifying and understanding safe havens for biodiversity under climate change. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 21, 393–404. 10.1111/j.1466-8238.2011.00686.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline, D. I. , Teneva, L. , Hauri, C. , Schneider, K. , Miard, T. , Chai, A. , … Hoegh‐Guldberg, O. (2015). Six month in situ high‐resolution carbonate chemistry and temperature study on a coral reef flat reveals asynchronous pH and temperature anomalies. PLoS ONE, 10, e0127648 10.1371/journal.pone.0127648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koweek, D. A. , Mucciarone, D. A. , & Dunbar, R. B. (2016). Bubble stripping as a tool to reduce high dissolved CO2 in coastal marine ecosystems. Environmental Science & Technology, 50, 3790–3797. 10.1021/acs.est.5b04733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koweek, D. A. , Zimmerman, R. C. , Hewett, K. M. , Gaylord, B. , Giddings, S. N. , Nickols, K. J. , … Caldeira, K. (2018). Expected limits on the ocean acidification buffering potential of a temperate seagrass meadow. Ecological Applications, 28, 1694–1714. 10.1002/eap.1771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause‐Jensen, D. , Duarte, C. M. , Hendriks, I. E. , Meire, L. , Blicher, M. E. , Marbà, N. , & Sejr, M. K. (2015). Macroalgae contribute to nested mosaics of pH variability in a subarctic fjord. Biogeosciences, 12, 4895–4911. 10.5194/bg-12-4895-2015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krause‐Jensen, D. , Marbà, N. , Sanz‐Martin, M. , Hendriks, I. E. , Thyrring, J. , Carstensen, J. , … Duarte, C. M. (2016). Long photoperiods sustain high pH in Arctic kelp forests. Science Advances, 2, e1501938 10.1126/sciadv.1501938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeker, K. J. , Kordas, R. L. , Crim, R. , Hendriks, I. E. , Ramajo, L. , Singh, G. S. , … Gattuso, J.‐P. (2013). Impacts of ocean acidification on marine organisms: Quantifying sensitivities and interaction with warming. Global Change Biology, 19, 1884–1896. 10.1111/gcb.12179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeker, K. J. , Sanford, E. , Rose, J. M. , Blanchette, C. A. , Chan, F. , Chavez, F. P. , … Washburn, L. (2016). Interacting environmental mosaics drive geographic variation in mussel performance and predation vulnerability. Ecology Letters, 19, 771–779. 10.1111/ele.12613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski, L. , & Orr, J. C. (2018). Diverging seasonal extremes for ocean acidification during the twenty‐first century. Nature Climate Change, 8, 141–145. 10.1038/s41558-017-0054-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Landschützer, P. , Gruber, N. , Bakker, D. C. E. , Stemmler, I. , & Six, K. D. (2018). Strengthening seasonal marine CO2 variations due to increasing atmospheric CO2 . Nature Climate Change, 8, 146–150. 10.1038/s41558-017-0057-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lifavi, D. M. , Targett, T. E. , & Grecay, P. A. (2017). Effects of diel‐cycling hypoxia and acidification on juvenile weakfish Cynoscion regalis growth, survival, and activity. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 564, 163–174. 10.3354/meps11966 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magris, R. A. , Pressey, R. L. , Weeks, R. , & Ban, N. C. (2014). Integrating connectivity and climate change into marine conservation planning. Biological Conservation, 170, 207–221. 10.1016/j.biocon.2013.12.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manzello, D. P. , Enochs, I. C. , Melo, N. , Gledhill, D. K. , & Johns, E. M. (2012). Ocean acidification refugia of the Florida Reef Tract. PLoS ONE, 7, e41715 10.1371/journal.pone.0041715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcleod, E. , Anthony, K. R. N. , Andersson, A. , Beeden, R. , Golbuu, Y. , Kleypas, J. , … Smith, J. E. (2013). Preparing to manage coral reefs for ocean acidification: Lessons from coral bleaching. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 11, 20–27. 10.1890/110240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mcneil, B. I. , Sweeney, C. , & JaE, G. (2011). Short Note: Natural seasonal variability of aragonite saturation state within two Antarctic coastal ocean sites. Antarctic Science, 23, 411–412. 10.1017/S0954102011000204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Millero, F. J. , Hiscock, W. T. , Huang, F. , Roche, M. , & Zhang, J. Z. (2001). Seasonal variation of the carbonate system in Florida Bay. Bulletin of Marine Science, 68, 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Mongin, M. , Baird, M. E. , Hadley, S. , & Lenton, A. (2016). Optimising reef‐scale CO2 removal by seaweed to buffer ocean acidification. Environmental Research Letters, 11, 034023. [Google Scholar]

- Morelli, T. L. , Daly, C. , Dobrowski, S. Z. , Dulen, D. M. , Ebersole, J. L. , Jackson, S. T. , … Beissinger, S. R. (2016). Managing climate change refugia for climate adaptation. PLoS ONE, 11, e0159909 10.1371/journal.pone.0159909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mos, B. , Dworjanyn, S. A. , Mamo, L. T. , & Kelaher, B. P. (2019). Building global change resilience: Concrete has the potential to ameliorate the negative effects of climate‐driven ocean change on a newly‐settled calcifying invertebrate. Science of the Total Environment, 646, 1349–1358. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulin, L. , Catarino, A. I. , Claessens, T. , & Dubois, P. (2011). Effects of seawater acidification on early development of the intertidal sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus (Lamarck 1816). Marine Pollution Bulletin, 62, 48–54. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2010.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munday, P. L. , Dixson, D. L. , Donelson, J. M. , Jones, G. P. , Pratchett, M. S. , Devitsina, G. V. , & Døving, K. B. (2009). Ocean acidification impairs olfactory discrimination and homing ability of a marine fish. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106, 1848–1852. 10.1073/pnas.0809996106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, C. S. , Malvezzi, A. , Gobler, C. J. , & Baumann, H. (2014). Offspring sensitivity to ocean acidification changes seasonally in a coastal marine fish. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 504, 1–11. 10.3354/meps10791 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, K. , Stachowicz, J. , Carter, H. , Boyer, K. , Bracken, M. , Chan, F. , … Wheeler, S. (2018). Emerging understanding of the potential role of seagrass and kelp as an ocean acidification management tool in California. Oakland, CA: California Ocean Science Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Noisette, F. , & Hurd, C. (2018). Abiotic and biotic interactions in the diffusive boundary layer of kelp blades create a potential refuge from ocean acidification. Functional Ecology, 32, 1329–1342. 10.1111/1365-2435.13067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- OA‐ICC . (2018). Ocean acidification news stream. Vienna, Austria: Ocean Acidification International Coordination Centre, International Atomic Energy Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, J. C. , Fabry, V. J. , Aumont, O. , Bopp, L. , Doney, S. C. , Feely, R. A. , … Yool, A. (2005). Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the twenty‐first century and its impact on calcifying organisms. Nature, 437, 681–686. 10.1038/nature04095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacella, S. R. , Brown, C. A. , Waldbusser, G. G. , Labiosa, R. G. , & Hales, B. (2018). Seagrass habitat metabolism increases short‐term extremes and long‐term offset of CO2 under future ocean acidification. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115, 3870–3875. 10.1073/pnas.1703445115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbi, S. R. (2003). Population genetics, demographic connectivity, and the design of marine reserves. Ecological Applications, 13, 146–158. 10.1890/1051-0761(2003)013[0146:PGDCAT]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poloczanska, E. S. , Brown, C. J. , Sydeman, W. J. , Kiessling, W. , Schoeman, D. S. , Moore, P. J. , … Richardson, A. J. (2013). Global imprint of climate change on marine life. Nature Climate Change, 3, 919–925. 10.1038/nclimate1958 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pörtner, H.‐O. , Karl, D. , Boyd, P. W. , Cheung, W. , Lluch‐Cota, S. E. , Nojiri, Y. , … Zavialov, P. (2014). Ocean systems In Field C. B., Barros V. R., Dokken D. J., Mach K. J., Mastrandrea M. D., Bilir T. E., Chatterjee M., Ebi K. L., Estrada Y. O., Genova R. C., Girma B., Kissel E. S., Levy A. N., Maccracken S., Mastrandrea P. R., & White L. L. (Eds.), Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: Global and sectoral aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 411–484). Cambridge, UK : Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Provoost, P. , Van Heuven, S. , Soetaert, K. , Laane, R. W. P. M. , & Middelburg, J. J. (2010). Seasonal and long‐term changes in pH in the Dutch coastal zone. Biogeosciences, 7, 3869–3878. 10.5194/bg-7-3869-2010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Racault, M.‐F. , Le Quéré, C. , Buitenhuis, E. , Sathyendranath, S. , & Platt, T. (2012). Phytoplankton phenology in the global ocean. Ecological Indicators, 14, 152–163. 10.1016/j.ecolind.2011.07.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramajo, L. , Pérez‐León, E. , Hendriks, I. E. , Marbà, N. , Krause‐Jensen, D. , Sejr, M. K. , … Duarte, C. M. (2016). Food supply confers calcifiers resistance to ocean acidification. Scientific Reports, 6, 19374 10.1038/srep19374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renforth, P. , & Henderson, G. (2017). Assessing ocean alkalinity for carbon sequestration. Reviews of Geophysics, 55, 636–674. 10.1002/2016RG000533 [DOI] [Google Scholar]