Abstract

The 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS) is a multisystem condition and the most prevalent microdeletion syndrome in humans. Approximately 25% of individuals with 22q11.2DS receive antipsychotic treatment. To assess whether patients with 22q11.2DS are vulnerable to adverse effects of antipsychotic medication, we carried out a literature review. A systematic search strategy was performed using PubMed (Medline), Embase, PsychInfo, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Publications describing adverse effects of antipsychotic medication in patients with 22q11.2DS were included in the review and assessed for their methodological quality. A total of 11 publications reporting on eight trials, cross‐sectional or cohort studies, and 30 case reports were included. The most commonly reported adverse effects can be classified into the following categories: movement disorders, weight gain, seizures, cardiac side effects, and cytopenias. Many of these symptoms are manifestations of 22q11.2DS, also in the absence of antipsychotic medication. Based on the reviewed literature, a causal relation between antipsychotic medication and the reported adverse effects could not be established in the majority of cases. Randomized clinical trials are needed to make firm conclusions regarding risk of adverse effects of antipsychotics in patients with 22q11.2DS.

Keywords: 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, adverse effects, antipsychotic medication, systematic review

1. INTRODUCTION

The 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS) is a multisystem condition associated with deletions on chromosome 22q11.2. With a prevalence of approximately 1 in 3000 live births, it is the most prevalent microdeletion syndromes in humans (Devriendt, Fryns, Mortier, Van Thienen, & Keymolen, 1998; Scambler, 2000). The 22q11.2 deletion mostly occurs de novo, and in the majority of cases the size of the deletion is around 3 Mb (McDonald‐McGinn et al., 2015). Independent of deletion size, the 22q11.2DS phenotype is highly variable. Common features include neurodevelopmental disorders and major birth defects such as congenital heart defects and submucous cleft palate, in addition to later‐onset conditions such as obesity and Parkinson's disease (Bassett et al., 2011; Fung et al., 2015; Voll et al., 2017). Endocrine problems and neuropsychiatric disorders are common manifestations, with the lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia in 22q11.2DS estimated to be up to 41% in adults (Schneider et al., 2014).

Although many patients with 22q11.2DS receive antipsychotic treatment for psychotic disorders or behavioral problems, little is known about the safety and tolerability of antipsychotics in people with 22q11.2DS. Current guidelines recommend following treatment guidelines for nondeleted patients with schizophrenia (Bassett et al., 2011; Fung et al., 2010). However, given the high prevalence of comorbid conditions, additional measures to safeguard tolerability and safety of antipsychotics might be needed. To assess whether patients with 22q11.2DS are vulnerable to side effects of antipsychotic medication, we carried out a systematic review.

2. METHODS

2.1. Literature search

This systematic review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐analysis (PRISMA) Statement (Moher et al., 2015). The literature search was conducted by two independent researchers (J.B. and L.G.) using PubMed (Medline), Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and PsychINFO. Combinations of the following search terms were used: “22q11.2DS,” “velocardiofacial syndrome,” “DiGeorge syndrome,” “Shprintzen syndrome,” and “adverse event” and “antipsychotic” or “psychosis.” The search had no year restrictions, and languages were restricted to Dutch, English, German, and French. See Supporting Information (Table S1) for an example search string. The search cut‐off date was December 7, 2018. Reference lists of the included studies were searched for cross‐references. After independent screening by J.B and L.G., consensus about which studies to include was reached between J.B, L.G., and J.Z.

2.2. Inclusion criteria

Publications were included when the following inclusion criteria were met: (a) the paper reported on a trial, cohort study or case report with specific mention of adverse events related to antipsychotic use; (b) the study included one or more patients with a molecularly confirmed diagnosis of 22q11.2DS; (c) the study was published in a peer‐reviewed journal or conference book. Quality of the included studies was assessed independently by J.B. and L.G. using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for harm studies (Higgins & Altman, 2008) or the tool for evaluating the methodological quality of case reports and case series (Murad, Sultan, Haffar, & Bazerbachi, 2018), dependent on the type of study (Table S2 and Table S3, respectively).

3. RESULTS

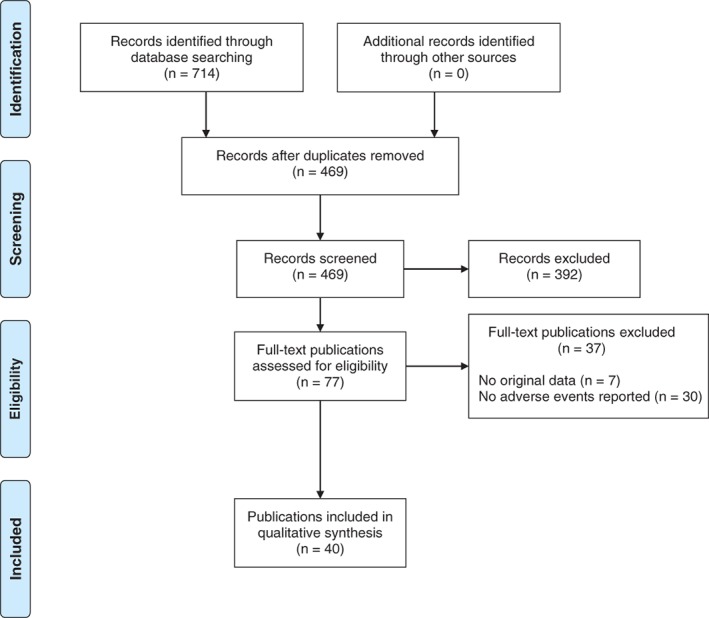

A flow diagram of the literature search is depicted in Figure 1. After screening the titles and abstracts, the search yielded 77 articles that reported on adverse events associated with antipsychotic use in patients with 22q11.2DS. After reading the full text of these 77 articles, 40 publications fulfilled inclusion criteria of which 11 (reporting on 8 studies) described trials, cross‐sectional or cohort studies (see Table 1 for descriptive information; Butcher, Fung, Cheung, et al., 2013; Butcher, Marras, Pondal, et al., 2014; Butcher, Fung, Fitzpatrick, Guna, Andrade, Lang, et al., 2015; Butcher, Fung, Fitzpatrick, Guna, Andrade, Lang, & Chow, 2015; Dori et al., 2017; Gothelf, 2015; Gothelf et al., 2015; Kawano et al., 2014; Verhoeven & Egger, 2015; Voll et al., 2017; Wither, Borlot, MacDonald, et al., 2017). None of the included studies were randomized or blinded in design. Additionally, 30 case reports (Aksu & Demirkaya, 2016; Angelopoulos et al., 2017; Biswas, Hands, & White, 2008; Boot, Butcher, van Amelsvoort et al., 2015; Borders, Suzuki, & Safani, 2017; Briegel, 2007; Butcher et al., 2014; Demily, Poisson, Thibaut, & Franck, 2017; Engebretsen, Kihldal, & Bakken, 2015; Faedda, Wachtel, Higgins, & Shprintzen, 2015; Farrell et al., 2018; Gagliano & Masi, 2009; Gladston & Clarke, 2005; Gothelf et al., 1999; Jacobson & Turkel, 2013; Kontoangelos, Maillis, Maltezou, Tsiori, & Papageorgiou, 2015; Kook et al., 2010; Krahn, Maraganore, & Michels, 1998; Le Page, 2006; Molebatsi & Olashore, 2018; Muller & Fellgiebel, 2008; O'Hanlon, Ritchie, Smith, & Patel, 2003; Ohi et al., 2013; Perret et al., 2017; Praharaj & Sarkar, 2010; Ruhe, Qureshi, & Procaccini, 2018; Sachdev, 2002; Starling & Harris, 2008; Thomas, 2003; Yacoub & Aybar, 2007) were included, summarized in Table 2. One publication described both a cross‐sectional study and a case report (Butcher et al., 2014), and is therefore included in both Tables 1 and 2. The most commonly reported symptoms that were potentially related to antipsychotic medication and that may have clinical implications were classified into the following categories: movement disorders, seizures, weight gain, cardiac side effects, and cytopenias. The main results for each of these categories are discussed separately. For a detailed overview see Table 2.

Figure 1.

Study attrition diagram [Color figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Table 1.

Overview of results from trials, cross‐sectional, and cohort studies

| Study | Publication type | Research design | Study objective | Population | Sample size (N) | Antipsychotic(s) | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22q11.2DS group | Comparison group | 22q11.2DS group | Comparison group | ||||||

|

Butcher et al. (2013), Butcher et al. (2014), Butcher, Fung, Fitzpatrick, Guna, Andrade, Lang, et al. (2015), and Butcher, Fung, Fitzpatrick, Guna, Andrade, Lang, & Chow (2015)a |

Abstracts (3x) + article | Retrospective | Assess whether patients 22q11.2DS schizophrenia show a different response profile to clozapine than those with idiopathic schizophrenia | Psychosis | Idiopathic psychosis | 20 | 20 | Clozapine | Half of the 22q11.2DS group (n = 10, 50%) experienced at least one serious adverse; event compared with none of the idiopathic group (gender‐adjusted OR = 16.5, 95% CI 1.8–149.8), comprising myocarditis (n = 1, 5%), severe neutropenia (n = 3, 15%) and seizures (n = 8, 40%). Seizures occurred at lower doses (250–400 mg) in 22q11.2DS patients than in idiopathic schizophrenia, despite anticonvulsants in a significant proportion of the patients |

| Dori, Green, Weizman, and Gothelf (2017) | Article | Retrospective | Evaluate the effectiveness and safety of antipsychotic and antidepressant medications in individuals with 22q11.2DS and psychiatric comorbidity | Psychosis | – | 19 (35 trials)b | – | Risperidone/olanzapine/quetiapine | Akathisia/parkinsonism (n = 9, 25.7%), weight gain (n = 5, 14%), drowsiness (n = 3, 8.7%), decreased appetite (n = 3, 8.7%), convulsions (n = 2, 5.7%), hyperprolactinemia and menstrual irregularities (n = 2, 5.7%), hyper salivation (n = 1, 2.9%), tics (n = 1, 2.9%), QT prolongation (n = 1, 2.9%), elevated liver enzymes (n = 1, 2.9%) |

| Gothelf (2015)c | Abstract | Prospective | Assess the safety and effectiveness of psychiatric medications in 22q11.2DS | Children and young adults | – | 86 | – | n.s. | Similar type and frequency of adverse events as in those reported in non‐22q11.2DS individuals using antipsychotics |

| Gothelf et al. (2015)c | Abstract | Prospective | Identify the phenotypic markers that are unique to 22q11.2DS and those associated with psychosis‐risk. Assess the safety and effectiveness of psychiatric medications in 22q11.2DS | Children and young adults | Children and young adults with Williams syndrome | 100 | 50 | n.s. | Similar type and frequency of adverse events as in those reported in non‐22q11.2DS individuals using antipsychotics |

| Kawano, Oshimo, Hasegawa, and Ishigooka (2014) | Abstract | Open‐label trial | Assess the safety and efficacy of aripiprazole in 22q11.2DS ASD | ASD | – | 3 | – | Aripiprazole | No adverse effects |

| Verhoeven and Egger (2015) | Article | Retrospective and prospective | Assess the efficacy of antipsychotics in 22q11.2DS and propose an appropriate psychopharmacological strategy | Adult and adolescent patients with psychosis | – | 28 | – | Clozapine/quetiapine/risperidone/haloperidol/aripiprazole | No major side effects |

| Voll et al. (2017) | Article | Cross‐sectional | Characterize the prevalence of and contributing factors to adult obesity 22q11.2DS | Adult patients | – | 207 | – | n.s. | Results for psychotropic medication use (including but not exclusively antipsychotics) and obesity: OR = 2.60 |

| Wither et al. (2017) | Article | Retrospective | Investigate the prevalence and characteristics of seizures and epilepsy in adult 22q11.2DS | Adult patients | – | 202 | – | n.s. | 32 (15.8%) had a documented history of seizures. Of these 145 (71.8%) had acute symptomatic seizures, usually associated with hypocalcemia and/or antipsychotic or antidepressant use |

Abbreviations: ASD, autism spectrum disorder; mg, milligram, n.s., not specified; −, not present.

These articles described the same study population and are therefore reported together here.

This study describes 19 patients that received a total of 35 trials with an antipsychotic.

These articles describe partly overlapping cohorts.

Table 2.

Overview of results from case reports

| Study | Publication type | Sex | Age | Intellectual functioning | History of seizures | Relevant comorbidities | Psychiatric disorder(s) | Medication regime | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial # | Antipsychotic(s), daily dose | Comedication, daily dose | Adverse effects and symptoms attributed to antipsychotic treatment | ||||||||

| Aksu and Demirkaya (2016) | Article | F | 15 | IQ 48 | Hypocalcemic convulsions | Thymus aplasia, hypoparathyroidism, hypocalcemia, kidney aplasia | Sz | 1 | Clozapine 500 mg | – | Generalized tonic–clonic convulsion |

| 2 | Clozapine 250 mg | Valproic acid 500 mg | Mild sedation, sialorrhea | ||||||||

| Angelopoulos et al. (2017) | Article | M | 19 | IQ 50 | – | Cardiomegaly, bilateral basal ganglia calcifications | Sz | 1 | Risperidone 20 mg | Biperiden 6 mg, Topiramate 100 mg | Gaps in memory, dizzy |

| 2 | Olanzapine 50 mg | Clonazepam 2 mg | Gaps in memory | ||||||||

| 3 | Haloperidol 60 mg, olanzapine 20 mg | Biperiden 6 mg, clonazepam 2 mg | Gaps in memory | ||||||||

| 4 | Clozapine 300 mg | Clonazepam 1 mg | – | ||||||||

| Biswas et al. (2008) | Article | F | 34 | Mild ID | – | Musculo‐skeletal abnormalities | Depression, borderline personality disorder, psychosis | 1 | Clozapine dose NR | – | Hyper salivation |

| Boot et al. (2015) | Article | M | 45 | Moderate to severe ID | – | – | Sz | 1 | Quetiapine 700 mg | – | Seizures and oculogyric crisis |

| 2 | Aripiprazole 15 mg | – | Generalized epileptic seizures | ||||||||

| 3 | Clozapine 150 mg | – | Myoclonus, cogwheel rigidity, rest tremors bilaterally | ||||||||

| M | 54 | Mild ID | – | Tardive dyskinesia as a result of previous antipsychotic treatments | Sz | 1 | Clozapine 300 mg | Benztropine 2 mg | Myoclonic jerks, seizure | ||

| 2 | Clozapine 200 mg | Clonazepam 3 mg | Hand tremor | ||||||||

| 3 | Clozapine 400 mg | Benztropine | Tonic–clonic seizures | ||||||||

| 4 | Clozapine dose NR | Gabapentin 3,000 mg, clonazepam 1.5 mg, calcium, vitamin D | Rest tremor | ||||||||

| M | 38 | Mild ID | – | – | Sz | 1 | Olanzapine 17.5 mg | Fluoxetine 20 mg, domperidone 40 mg, calcium, vitamin D | Decreased facial expression, slowness, rigidity, decrease in restlessness, periodic oculogyric movements | ||

| Borders et al. (2017) | Article | F | 34 | IQ 87 | – | Right aortic arch, cerebellar cyst, scoliosis, hypocalcaemia | ASD, sz, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder | 1 | Quetiapine dose NR | – | Sedation |

| 2 | Aripiprazole dose NR | – | Shaking and claw‐like spasms | ||||||||

| 3 | Asenapine 10 mg | Clonazepam 1 mg | Dystonic reactions, including shaking and claw‐like spasms of the hand | ||||||||

| Briegel (2007) | Abstract | M | 10 | – | – | – | Sz | 1 | Clozapine dose NR | – | Seizure |

| Butcher et al. (2014) | Abstract | M | 54 | – | – | – | Sz | 1 | Clozapine dose NR | – | Progressive parkinsonism (including bradykinesia, rigidity, and right‐sided tremor) and myoclonus |

| Demily et al. (2017) | Article | M | 37 | – | – | – | Sz | 1 | Quetiapine 300 mg | – | Weight loss |

| Engebretsen et al. (2015) | Article | F | 19 | – | Graves' disease | Schizoaffective disorder | 1 | Olanzapine dose NR | Weight gain, increased blood sugar, leukopenia | ||

| 2 | Ziprasidone dose NR | – | – | ||||||||

| 3 | Aripiprazole dose NR | – | – | ||||||||

| 4 | Amisulpride dose NR | – | Unspecified severe side effects | ||||||||

| 5 | Quetiapine dose NR | – | Tiredness | ||||||||

| 6 | Haloperidol dose NR | – | Weight loss, compulsions | ||||||||

| 7 | Clozapine dose NR | – | Severe tremor, leukopenia | ||||||||

| 8 | Risperidone dose NR | – | – | ||||||||

| Faedda et al. (2015) | Article | F | 15 | IQ 58 | – | Asthma | Possible ADHD, anxiety disorder NOS | 1 | Olanzapine 15 mg | Lorazepam 12 mg | Weight gain (30 pounds in 3 months) |

| 2 | Ziprasidone 120 mg | – | Body aches and tight throat with swallowing problems | ||||||||

| Farrell et al. (2018) | Article | M | 41 | IQ 80 | – | Huntington's disease, hyperkinetic movement disorder (oro‐lingual‐buccal dyskinesia, choreoathetosis, mingled with repetitive grabbing movements, and posturing of the left upper extremity) | Sz | 1 | Perphenazine dose NR | Lithium | – |

| 2 | Perphenazine, olanzapine, clozapine; doses NR | – | Thrombocytopenia | ||||||||

| 3 | Clozapine dose NR | – | Obesity | ||||||||

| 4 | Clozapine, Risperidone; doses NR | Fluoxetine | Thrombocytopenia, obesity | ||||||||

| 5 | Clozapine, Ziprasidone dose NR | – | – | ||||||||

| Gagliano and Masi (2009) | Article | F | 7 | – | Idiopathic precocious puberty, high levels of B‐humanchorionic gonadotropin and estradiol | Sz | 1 | Risperidone 1.5 mg, Aripiprazole 7.5 mg | – | Mild and transient nausea | |

| 2 | Clozapine 150 mg, Aripiprazole 8.7 mg | Tamoxifen 10 mg | Psychomotor agitation | ||||||||

| 3 | Clozapine 150 mg, Aripiprazole 10 mg | Valproic 900 mg, Tamoxifen 10 mg | Neutropenia | ||||||||

| 4 | Clozapine 150 mg, Aripiprazole 15 mg | Lithium 600 mg, Tamoxifen 10 mg | Sedation, enuresis, increased appetite | ||||||||

| 5 | Clozapine 200 mg, Aripiprazole 15 mg | Lithium 600 mg, Tamoxifen 10 mg | Weight gain, tachycardia | ||||||||

| Gladston and Clarke (2005) | Article | M | 32 | IQ 66 | – | Palate abnormality | Schizoaffective disorder | 1 | Clozapine 300 mg | – | Hypersalivation, constipation, myoclonic‐epilepsy |

| 2 | Clozapine 300 mg | Sodium valproate 300 mg | Myoclonic jerks | ||||||||

| 3 | Clozapine 300 mg | Sodium valproate 1,200 mg | – | ||||||||

| Gothelf et al. (1999) | Article | F | 35 | – | Psychosis | 1 | Clozapine 200 mg | Valproate 600 mg | Unspecified myoclonic jerks | ||

| Jacobson and Turkel (2013)a | Article | F | 2 | – | A prior seizure | Congenital heart defect, recurrent pneumonia, pulmonary hypertension, and right heart failure, recently developed choreiform movements | Delirium | 1 | Fluphenazine dose NR | Fentanyl, midazolam, Lorazepam, chloral hydrate, Vecuronium, transdermal clonidine, diphenhydramine, Pressors, anticoagulants, diuretics, sildenafil | Elevated liver enzymes |

| Kontoangelos et al. (2015) | Article | M | 18 | – | – | Behavioral disorders | 1 | Haloperidol 2 mg | – | Cervical dystonia, torticollis, continuous twisting movements of the trunk and limbs, dysarthria | |

| 2 | Quetiapine 200 mg | – | |||||||||

| Kook et al. (2010) | Article | F | 25 | – | Hypothyroidism, hypoparathyroidism | Sz | 1 | Risperidone 8 mg | Levothyroxine and vitamin D | Generalized tonic–clonic seizures | |

| Krahn et al. (1998) | Article | M | 27 | IQ 70 | – | Ventricular septal defect and persistent ductus arteriosus, Parkinson's disease | Sz | 1 | Fluphenazine (decanoate) | – | Muscle rigidity, oral‐buccal movements, tremors of tongue and upper extremities, drug‐induced parkinsonism |

| 2 | Clozapine 125 mg | Levocarbidopa 100/25 mg, amantadine 100 mg, Benztropine 2 mg | Resting tremor of all limbs, generalized bradykinesia, generalized tonic–clonic seizures | ||||||||

| Le Page (2006) | Article | F | 17 | Borderline intellectual functioning | – | Psychosis | 1 | Clozapine dose NR | – | Agranulocytosis | |

| 2 | Haloperidol dose NR | Sodium valproate | Thrombocytopenia | ||||||||

| Molebatsi and Olashore (2018) | Article | F | 13 | – | Complex congenital heart defect | Sz | 1 | Haloperidol 3 mg | – | Akathisia, sialorrhea | |

| 2 | Olanzapine 5 mg | – | – | ||||||||

| Muller and Fellgiebel (2008) | Article | F | 41 | Mild ID | – | Bilateral hearing loss, ventricular tachycardia | Psychosis | 1 | Quetiapine 400 mg | – | – |

| O'Hanlon et al. (2003) | Article | F | 23 | Mild ID | Right bundle‐branch block, lymphopenia, thrombocyto‐penia | Psychosis | Previous trials | Haloperidol, Thiothixene, Risperidone, Thioridazine, olanzapine, Quetiapine; doses NR | – | Hypertension, seizure disorder | |

| 1 | Thioridazine 50 mg | Propranolol 20 mg, Bromocriptine 2.5 mg, phenytoin 200 mg | – | ||||||||

| 2 | Olanzapine 30 mg | Propranolol 20 mg, Bromocriptine 2.5 mg, phenytoin 200 mg | Worsening of chronic thrombocytopenia | ||||||||

| Ohi et al. (2013) | Article | F | 48 | IQ 80 | Thymic hypoplasia, hypocalcemia bilateral basal ganglia calcifications, thrombocytopenia | Sz | 1 | Risperidone 1,200 mg | – | Generalized spasm | |

| Perret et al. (2017) | Article | F | 27 | IQ 100 | Multiple congenital malformations | Bipolar disorder type 1, psychotic episode | 1 | Olanzapine 10 mg | – | Weight gain, tremor, unspecified dystonia | |

| 2 | Risperidone dose NR | – | Weight gain, tremor, unspecified dystonia | ||||||||

| Praharaj and Sarkar (2010) | Article | M | 21 | IQ 85 | Bifascicular block, ventricular ejection fraction 63% | Predominantly manic symptoms | 1 | Olanzapine 20 mg | Sodium valproate 2 mg | Thrombocytopenia | |

| 2 | Clozapine 300 mg | ‐ | Thrombocytopenia | ||||||||

| Ruhe et al. (2018) | Article | M | 17 | – | – | Hypothyroidism | Bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | 1 | Clozapine 175 mg | Cariprazine 6 mg | Mild diarrhea, thrombocytopenia, neck stiffness, sore throat, myocarditis |

| Levothyroxine 100 mg | |||||||||||

| Sachdev (2002) | Article | M | 22 | Mild to moderate ID | Epileptic seizures | – | Psychotic disorder | 1 | Chlorpromazine 100 mg | – | Drowsiness, hypotension |

| 2 | Olanzapine 10 mg | – | Tremulous, hypotension, myoclonus of the limbs | ||||||||

| Starling and Harris (2008) | Article | F | 16 | Moderate ID | Epilepsy with myoclonic jerks and generalized seizures | Ventricular septal defect, poor motor skills, cortical, and cerebellar atrophy | Repetitive behavior, angry outbursts, depressed mood, auditory hallucinations | 1 | Olanzapine 7.5 mg | – | Weight gain |

| 2 | Aripiprazole 20 mg | Sodium valproate 800 mg | Neuroleptic malignant syndrome | ||||||||

| F | 15 | – | – | Gray matter heterotopia frontal horn of the lateral ventricles bilaterally, hyperdense foci in right frontal horn on MRI | Depressed mood, paranoid delusions, and hallucinations | 1 | Olanzapine 20 mg | Fluvoxamine 50 mg | Weight gain | ||

| M | 18 | – | Congenital hypoparathyroidism, pulmonary artery stenosis, hyperdense foci in frontal lobes, and basal ganglia on cerebral CT | Psychosis | 1 | Quetiapine 800 mg | – | Sedation, weight gain | |||

| 2 | Amisulpride 1,000 mg | – | Unspecified dystonia | ||||||||

| 3 | Olanzapine 30 mg | – | Sedation, weight gain | ||||||||

| Thomas (2003) | Article | M | 23 | ID | – | – | Psychosis | 1 | Risperidone 2 mg | Calcium | Psychomotor retardation |

| Yacoub and Aybar (2007) | Article | F | 25 | Borderline intellectual functioning | – | Prominence of the lateral ventricles | Psychosis | 1 | Clozapine 150 mg | – | Mild sedation, hyper salivation, tonic–clonic seizure |

| 2 | Clozapine 75 mg | Divalproex sodium 750 mg | – | ||||||||

Abbreviations: – = not reported/not present, mg = milligram, F = female, M = male, sz = schizophrenia, ASD = autism spectrum disorder, # = number, NR = not reported, ID = intellectual disability.

This case report describes a 2‐year‐old with recurrent pneumonia, a prior seizure, pulmonary hypertension, and right heart failure. The child underwent surgical repair of congenital cardiac defects. Psychiatrists were consulted to assist with managing the delirium while she was intubated and sedated.

3.1. Movement disorders

Extrapyramidal symptoms were frequently reported in individuals with 22q11.2DS treated with antipsychotics. In 19 patients who together received 35 trials with risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine (Dori et al., 2017), extrapyramidal symptoms were reported in nine of the 35 (25.7%) trials. No information was provided on whether extrapyramidal symptoms occurred more often during treatment with either risperidone, olanzapine or quetiapine. The severity or the type of motor symptoms was also not reported. Notably, although clozapine is generally considered to be practically free of motor side effects (Casey, 1989; Rummel‐Kluge et al., 2010), several case studies reported extrapyramidal symptoms in patients on monotherapy with clozapine (Boot, Butcher, van Amelsvoort, et al., 2015; Gagliano & Masi, 2009; Gladston & Clarke, 2005; Krahn et al., 1998; Ruhe et al., 2018), see Table 2. Noteworthy, there was one case report of a 27‐year‐old man with increasing parkinsonism (including bradykinesia, rigidity, and rest tremor) while on clozapine treatment (Krahn et al., 1998). The progressive nature of his symptoms however suggested that these symptoms were not primarily drug induced. Myoclonus was reported in several case reports under clozapine (Boot, Butcher, van Amelsvoort, et al., 2015; Butcher et al., 2014; Gladston & Clarke, 2005; Gothelf et al., 1999), and in one case under olanzapine treatment (Sachdev, 2002). Dystonia was reported during treatment with amisulpride (Starling & Harris, 2008), haloperidol (Kontoangelos et al., 2015), risperidone (Perret et al., 2017), asenapine (Borders et al., 2017) olanzapine (Boot, Butcher, van Amelsvoort, et al., 2015; Perret et al., 2017), and quetiapine (Boot, Butcher, van Amelsvoort, et al., 2015).

3.2. Seizures

Seizures were reported after the start of quetiapine (Boot, Butcher, van Amelsvoort, et al., 2015), aripiprazole (Boot, Butcher, van Amelsvoort, et al., 2015), risperidone (Kook et al., 2010), and clozapine (Aksu & Demirkaya, 2016; Boot et al., 2015; Briegel, 2007; Gladston & Clarke, 2005; Krahn et al., 1998; Yacoub & Aybar, 2007) in individuals with 22q11.2DS. In a retrospective study that looked at the response profile to clozapine, eight of the 20 (44.4%) adults with 22q11.2DS experienced seizures, where patients in the idiopathic psychosis group (n = 20) experienced none (Butcher, Fung, Fitzpatrick, Guna, Andrade, Lang, & Chow, 2015). Out of the 17 case reports of individuals treated with clozapine that fulfilled inclusion criteria for this review, five cases (29.4%) reported tonic–clonic seizures (Aksu & Demirkaya, 2016; Boot, Butcher, Vorstman, et al., 2015; Briegel, 2007; Krahn et al., 1998; Yacoub & Aybar, 2007). In a retrospective chart review study in 202 adults with 22q11.2DS it was found that 21 of the 119 patients (17.6%) on psychotropic drugs experienced one or more seizures, and 16 patients (50% of the patients with seizures) experienced their first seizure while taking an antipsychotic (Wither, MacDonald, Borlot, et al., 2017). The antipsychotic most commonly associated with seizures was clozapine Wither, Borlot, MacDonald, et al., 2017.

3.3. Weight gain

Weight gain was mostly reported in patients that use risperidone (Borders et al., 2017), quetiapine (Starling & Harris, 2008), olanzapine (Faedda et al., 2015; Perret et al., 2017; Starling & Harris, 2008), and clozapine (Gagliano & Masi, 2009). Weight gain was the second most frequent adverse effect reported in five (14.2%) out of the 35 trials with risperidone, quetiapine, and olanzapine (Dori et al., 2017). In a study in 207 adults with 22q11.2DS, it was found that psychotropic medication use, including but not exclusively antipsychotics, increased the odds of developing obesity with ~2.5 times relative to those without psychotropic medication (Voll et al., 2017).

3.4. Cardiac adverse effects

Two cases of clozapine‐induced myocarditis, expected to occur in ~3% of patients on clozapine in general (Ronaldson, Fitzgerald, & McNeil, 2015), have been reported in patients with 22q11.2DS (Boot, Butcher, Vorstman, et al., 2015; Ruhe et al., 2018). In addition, one case report described the development of QT prolongation after sertraline was added to treatment with quetiapine and risperidone, which normalized after discontinuation of sertraline (Dori et al., 2017).

3.5. Cytopenias

In a retrospective study that looked at the response profile to clozapine, three (15%) of the 20 patients presented with severe neutropenia, while no neutropenia was seen in the patients with idiopathic psychosis (Butcher, Fung, Fitzpatrick, Guna, Andrade, Lang, & Chow, 2015). Neutropenia associated with clozapine use was also reported in two case reports (Gagliano & Masi, 2009; Le Page, 2006), in one case leading to agranulocytosis (Le Page, 2006). It must be noted that the child (aged 7 years) described in the first case report (Gagliano & Masi, 2009) also used aripiprazole and tamoxifen; neutropenia has been reported as a side effect of both drugs in patients without 22q11.2DS (Felin, Naveed, & Chaudhary, 2018; Miké, Currie, & Gee, 1994). Leukopenia was reported with the use of olanzapine monotherapy and clozapine monotherapy (Engebretsen et al., 2015). Thrombocytopenia has been reported in many patients that used clozapine (Farrell et al., 2018; Praharaj & Sarkar, 2010), risperidone (Farrell et al., 2018), haloperidol (Le Page, 2006), olanzapine (Farrell et al., 2018; O'Hanlon et al., 2003; Praharaj & Sarkar, 2010), and perphenazine (Farrell et al., 2018).

3.6. Critical appraisal

The quality of the trials, cross‐sectional and cohort studies (see Table S2) was highly variable. Most studies were retrospective in nature, and patients and assessors were not blinded to either treatment or outcome. Study objectives differed among the included studies; assessing the safety and tolerability of antipsychotics was not the main objective for all studies. Furthermore, most studies did not apply corrections for possible confounders, and patient selection was mostly unclear. It is noted that some studies reported on partly overlapping cohorts, therefore we combined those references in our results section (see Table 1).

Critical appraisal of the case reports is described in Table S3. It is noted that only two out of 30 case reports performed a challenge–rechallenge approach. Also, dose–response relations were scarcely reported (n = 4). Most case reports did not assess the possibility of alternative causes for the reported symptoms. These aspects are essential in determining the likelihood of a causal relation between symptoms and medication use. Therefore, the evidence derived from the case reports remains inconclusive.

4. DISCUSSION

This study is the first to provide a systematic overview of the literature specifically on reported adverse effects of antipsychotic medication in patients with a 22q11.2DS. Symptoms that were reported as (possible) adverse effects were movement disorders, seizures, weight change, cardiac side effects and cytopenias. These symptoms are also known adverse effects of antipsychotics in the nondeleted (general) population. While there is an abundance of case reports, research to this date is merely observational in nature and randomized and/or controlled trials are lacking.

The only study that directly compared the tolerability to antipsychotics in adults with 22q11.2DS to patients without a 22q11.2 deletion (Butcher, Fung, Fitzpatrick, Guna, Andrade, Lang, & Chow, 2015) reported that half of the 22q11.2DS group (n = 10, 50%) experienced at least one serious adverse event under treatment with clozapine compared with none of the idiopathic group (gender‐adjusted OR = 16.5, 95% CI 1.8–149.8). Reported adverse events included myocarditis (n = 1, 5%), severe neutropenia (n = 3, 15%) and seizures (n = 8, 40%). However, in this retrospective study, no challenge–rechallenge or dose–response effects were reported.

Our findings are consistent with a recent review that examined effectiveness and side effects of psychiatric medication in individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome with comorbid psychiatric disorders (Mosheva, Korotkin, Gur, Weizman, & Gothelf, 2019). The authors concluded that individuals with 22q11.2DS and psychiatric disorders are treated in a manner that is similar to those without 22q11.2DS but that comorbid disorders common in 22q11.2DS may complicate treatment to some extent (Mosheva et al., 2019).

In fact, most of the events that were reported as adverse effects are, or may be, common manifestations of 22q11.2DS, even in the absence of antipsychotic medication. Therefore, if and to what extent, the use of antipsychotics was responsible for the observed symptoms could not be established. For example, parkinsonism may not be uncommon in adults with 22q11.2DS (Boot, Butcher, van Amelsvoort, et al., 2015; Butcher et al., 2017). Notably, individuals with 22q11.2DS have an increased risk of developing early‐onset Parkinson's disease, with an average age at onset around age 40 years (Boot et al., 2018; Butcher, Kiehl, Hazrati, et al., 2013). It is therefore important to differentiate between antipsychotic medication‐induced extrapyramidal adverse effects and Parkinson's disease in this population. Dopamine transporter (DAT) imaging may be helpful in this (Booij, van Amelsvoort, & Boot, 2010).

Furthermore, seizures and epilepsy, are more prevalent in individuals with 22q11.2DS than in the general population (Wither et al., 2017), and anticonvulsant treatment may be necessary (Wither et al., 2017), especially in those patients on clozapine (Butcher et al., 2015). In addition to hypocalcemia, antipsychotic medication, in particular clozapine, is an important contributor to a lowered seizure threshold in adults with 22q11.2DS that should alert clinicians (Wither et al., 2017).

Weight gain and metabolic syndrome are well‐known adverse events of antipsychotic medication (Allison & Casey, 2001; Newcomer, 2007). No studies assessed whether patients with 22q11.2DS have an increased risk compared to other populations. However, in a study in adults with 22q11.2DS, it was found that psychotropic medication use, including but not exclusively antipsychotics, increased the odds of developing obesity with ~2.5 times (Voll et al., 2017). Given the comorbidity in 22q11.2DS, such as congenital heart defects, the observed risk of developing obesity during antipsychotic treatment may also warrant extra attention.

Thrombocytopenia was reported in several patients on antipsychotic medication. However, thrombocytopenia is a common manifestations of 22q11.2DS (Bassett et al., 2011), and patients with 22q11.2DS typically have reduced platelet counts that usually do not require specific precautions (Lawrence, McDonald‐McGinn, Zackai, & Sullivan, 2003). A low white blood cell count was also frequently seen, including 15% (3 out of 20) of the patients on clozapine in the study by Butcher et al. (2015), above general population expectations (Schulte, 2006).

Given the increased prevalence of physical health problems in 22q11.2DS additional safety measures are recommended to prevent and monitor side effects and the occurrence of serious adverse events, see Box 1 for more information.

Box 1. Recommendations for prescribing antipsychotic medication in 22q11.2DS.

As patients with 22q11.2DS may be at increased risk for movement disorders, a motor assessment should be part of standard clinical practice.

Be aware that patients with 22q11.2DS are at increased risk for developing early‐onset Parkinson's disease, with mean age at onset for motor signs relatively young at approximately 40 years. Molecular imaging may be helpful to distinguish Parkinson's disease from antipsychotic medication‐induced parkinsonism.

As most antipsychotic medications lower seizure threshold (particularly with clozapine), and 22q11.2DS is associated with hypocalcemic seizures, frequent monitoring of calcium levels is warranted.

To reduce seizure risk, consider the addition of low‐dose anticonvulsant when clozapine is initiated.

Consider to consult a neurologist in case of, nonhypocalcemic, seizures.

Promote daily exercise and a healthy diet to prevent weight gain during antipsychotic treatment.

In general, it is recommended to monitor calcium levels, thyroid function and platelets on a regular basis, and to follow general management recommendations for adults with 22q11.2DS (Fung et al., 2015).

It is important to note that 50% of the case studies reported on clozapine use in 22q11.2DS, and this is much higher than expected (Nielsen, Røge, Schjerning, Sørensen, & Taylor, 2012) given that clozapine is usually prescribed for treatment‐resistant schizophrenia. This may indicate a publication bias in the included case reports; as of yet, there is no evidence for increased prevalence of treatment‐resistant schizophrenia in 22q11.2DS. It has been suggested that regular antipsychotics may have limited effect in 22q11.2DS (Verhoeven & Egger, 2015) but to the best of our knowledge, there are no randomized controlled trials supporting this hypothesis. It is likely, however, that clozapine is prescribed more often to patients with 22q11.2DS given that clozapine is less likely than other antipsychotic medications to cause motor side effects (Casey, 1989; Rummel‐Kluge et al., 2010). Given the multisystem nature of the condition, and the increased prevalence of physical health problems in 22q11.2DS, extra attention is recommended to prevent and monitor the occurrence of (serious) adverse events, see Box 1 for more information.

5. CONCLUSION

Most of the reported adverse effects in this systematic review; movement disorders, seizures, weight change, cardiac side effects, leukopenia and thrombocytopenia, are common manifestations in individuals with 22q11.2DS, even in the absence of antipsychotic medication. Also, the reported adverse effects in 22q11.2DS are mostly similar to common side effects of antipsychotic medication observed in the nondeleted (general) population. Based on the existing literature, a causal relation between antipsychotic medication and the reported adverse effects could not be established. Randomized clinical trials are needed to make firm conclusions regarding risk of adverse effects of antipsychotics in people with 22q11.2DS. In conclusion, when considering antipsychotic medication in patients with 22q11.2DS, clinicians need to balance potential risks and benefits, and monitor patients regularly to screen for side effects.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the topic and contents of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.B. and L.G. performed the literature search, screening, and quality assessments. J.B. took the lead in writing the manuscript. J.Z. designed and coordinated the project. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the interpretation and manuscript. All authors approved the final version of this article.

Supporting information

Data S1 Table S1: Systematic search strategy

Table S2: Quality assessment trials, cohorts and case–control studies

Table S3: Quality assessment case reports

de Boer J, Boot E, van Gils L, van Amelsvoort T, Zinkstok J. Adverse effects of antipsychotic medication in patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: A systematic review. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2019;179:2292–2306. 10.1002/ajmg.a.61324

REFERENCES

- Aksu, H. , & Demirkaya, S. K. (2016). Treatment of schizophrenia by clozapine in an adolescent girl with digeorge syndrome. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 26(7), 652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison, D. B. , & Casey, D. E. (2001). Antipsychotic‐induced weight gain: A review of the literature. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62(Suppl7), 22–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelopoulos, E. , Theleritis, C. , Economou, M. , Georgatou, K. , Papageorgiou, C. C. , & Tsaltas, E. (2017). Antipsychotic treatment of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome‐related psychoses. Pharmacopsychiatry, 50(4), 162–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett, A. S. , McDonald‐McGinn, D. M. , Devriendt, K. , Digilio, M. C. , Goldenberg, P. , Habel, A. , … Sullivan, K. (2011). Practical guidelines for managing patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. The Journal of Pediatrics, 159(2), 332–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, A. B. , Hands, O. , & White, J. (2008). Velocardiofacial syndrome in intellectual disability: Borderline personality disorder behavioral phenotype and treatment with clozapine—A case report. Mental Health Aspects of Developmental Disabilities, 11(3), 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Booij, J. , van Amelsvoort, T. , & Boot, E. (2010). Co‐occurrence of early‐onset Parkinson disease and 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: Potential role for dopamine transporter imaging. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part A, 152(11), 2937–2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boot, E. , Butcher, N. , Vorstman, J. , van Amelsvoort, T. A. M. J. , Fung, W. , & Bassett, A. S. (2015). Pharmacological treatment of 22q112 deletion syndrome‐related psychoses. Pharmacopsychiatry, 48(6), 219–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boot, E. , Butcher, N. J. , Udow, S. , Marras, C. , Mok, K. Y. , Kaneko, S. , … Bassett, A. S. (2018). Typical features of Parkinson disease and diagnostic challenges with microdeletion 22q11.2. Neurology, 90(23), e2059–e2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boot, E. , Butcher, N. J. , van Amelsvoort, T. , Lang, A. E. , Marras, C. , Pondal, M. , … Bassett, A. S. (2015). Movement disorders and other motor abnormalities in adults with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part A, 167(3), 639–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borders, C. B. , Suzuki, A. , & Safani, D. (2017). Treatment of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome‐associated schizophrenia with comorbid anxiety and panic disorder. Mental Illness, 9(2), 7225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briegel, W. (2007). 22q11.2 deletion and schizophrenia in childhood and adolescence. Zeitschrift Fur Kinder‐Und Jugendpsychiatrie Und Psychotherapie, 35(5), 353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, N. , Fung, W. , Cheung, E. , Slade, L. , Chow, E. , & Bassett, A. (2013). Pharmacogenetic response to clozapine treatment in schizophrenia: New insights from a genetic form of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 39, S29. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, N. , Fung, W. , Fitzpatrick, L. , Guna, A. , Andrade, D. , Lang, A. , … Bassett, A. (2015). Personalizing treatment of schizophrenia: Clozapine response in a molecular subtype. Biological Psychiatry, 77(9), 187S. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, N. , Fung, W. L. A. , Fitzpatrick, L. , Guna, A. , Andrade, D. M. , Lang, A. E. , & Chow, E. W. C. (2015). Response to clozapine in a clinically identifiable subtype of schizophrenia. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 206(6), 484–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, N. , Marras, C. , Pondal, M. , Christopher, L. , Strafella, A. , Fung, W. , … A.S., B. (2014). Motor dysfunction in adults with hemizygous 22q11.2 deletions at high risk of early‐onset Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders, 29, S46. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, N. J. , Kiehl, T.‐R. , Hazrati, L.‐N. , Chow, E. W. C. , Rogaeva, E. , Lang, A. E. , & Bassett, A. S. (2013). Association between early‐onset Parkinson disease and 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: Identification of a novel genetic form of Parkinson disease and its clinical implications. JAMA Neurology, 70(11), 1359–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, N. J. , Marras, C. , Pondal, M. , Rusjan, P. , Boot, E. , Christopher, L. , … Bassett, A. S. (2017). Neuroimaging and clinical features in adults with a 22q11.2 deletion at risk of Parkinson's disease. Brain: A Journal of Neurology, 140(5), 1371–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey, D. E. (1989). Clozapine: Neuroleptic‐induced EPS and tardive dyskinesia. Psychopharmacology, 99(1), S47–S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demily, C. , Poisson, A. , Thibaut, F. , & Franck, N. (2017). Weight loss induced by quetiapine in a 22q11.2DS patient. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports, 13, 95–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devriendt, K. , Fryns, J.‐P. , Mortier, G. , Van Thienen, M. N. , & Keymolen, K. (1998). The annual incidence of DiGeorge/velocardiofacial syndrome. Journal of Medical Genetics, 35(9), 789–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dori, N. , Green, T. , Weizman, A. , & Gothelf, D. (2017). The effectiveness and safety of antipsychotic and antidepressant medications in individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 27(1), 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engebretsen, M. , Kihldal, A. , & Bakken, T. (2015). Metyrosine treatment in a woman with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, psychosis and aggressive behaviour. A case study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 59, 116–117.23919538 [Google Scholar]

- Faedda, G. L. , Wachtel, L. E. , Higgins, A. M. , & Shprintzen, R. J. (2015). Catatonia in an adolescent with velo‐cardio‐facial syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part A, 167(9), 2150–2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, M. , Lichtenstein, M. , Crowley, J. J. , Filmyer, D. M. , Lazaro‐Munoz, G. , Shaughnessy, R. A. , … Sullivan, P. F. (2018). Developmental delay, treatment‐resistant psychosis, and early‐onset dementia in a man with 22q11 deletion syndrome and Huntington's disease. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(5), 400–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felin, T. , Naveed, S. , & Chaudhary, A. M. (2018). Aripiprazole‐induced neutropenia: Case report and literature review. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 56(5), 21–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung, W. L. A. , Butcher, N. J. , Costain, G. , Andrade, D. M. , Boot, E. , Chow, E. W. C. , … Fishman, L. (2015). Practical guidelines for managing adults with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Genetics in Medicine, 17(8), 599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung, W. L. A. , McEvilly, R. , Fong, J. , Silversides, C. , Chow, E. , & Bassett, A. (2010). Elevated prevalence of generalized anxiety disorder in adults with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(8), 998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliano, A. , & Masi, G. (2009). Clozapine‐aripiprazole association in a 7‐year‐old girl with schizophrenia: Clinical efficacy and successful management of neutropenia with lithium. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 19(5), 595–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladston, S. , & Clarke, D. J. (2005). Clozapine treatment of psychosis associated with velo‐cardio‐facial syndrome: Benefits and risks. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49(7), 567–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothelf, D. (2015). Risk factors for schizophrenia and psychiatric treatments in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 25, S118. [Google Scholar]

- Gothelf, D. , Frisch, A. , Munitz, H. , Rockah, R. , Laufer, N. , Mozes, T. , … Frydman, M. (1999). Clinical characteristics of schizophrenia associated with velo‐cardio‐facial syndrome. Schizophrenia Research, 35(2), 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothelf, D. , Mekoria, E. , Weinberger, E. , Midbaria, Y. , Dorib, N. , Green, T. , & Weizman, A. (2015). Neurodevelopmental risk factors for psychosis in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome and their treatment. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(1), S76–S77. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J. P. , & Altman, D. G. (2008). Assessing risk of bias in included studies. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Cochrane book series, 187–241. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, J. R. , & Turkel, S. B. (2013). Elevated liver enzymes associated with fluphenazine used to manage delirium symptoms in infants. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 23(7), 513–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano, M. , Oshimo, T. , Hasegawa, D. , & Ishigooka, J. (2014). Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole used for impulsiveness in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome with autism spectrum disorder. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 17, 78. [Google Scholar]

- Kontoangelos, K. , Maillis, A. , Maltezou, M. , Tsiori, S. , & Papageorgiou, C. C. (2015). Acute dystonia in a patient with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Mental Illness, 7(2), 30–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kook, S. D. , An, S. K. , Kim, K. R. , Kim, W. J. , Lee, E. , & Namkoong, K. (2010). Psychotic features as the first manifestation of 22q I I.2 deletion syndrome. Psychiatry Investigation, 7(1), 72–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahn, L. E. , Maraganore, D. M. , & Michels, V. V. (1998). Childhood‐onset schizophrenia associated with parkinsonism in a patient with a microdeletion of chromosome 22. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 73(10), 956–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, S. , McDonald‐McGinn, D. M. , Zackai, E. , & Sullivan, K. E. (2003). Thrombocytopenia in patients with chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. The Journal of Pediatrics, 143(2), 277–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Page, H. (2006). Clinical case rounds in child and adolescent psychiatry: Treatment resistant psychosis in an adolescent with scoliosis and a history of early feeding difficulties. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry/Journal de l'Academie Canadienne de Psychiatrie de L'enfant et de L'adolescent, 15(4), 179–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald‐McGinn, D. M. , Sullivan, K. E. , Marino, B. , Philip, N. , Swillen, A. , Vorstman, J. A. S. , … Morrow, B. E. (2015). 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 1, 15071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miké, V. , Currie, V. , & Gee, T. (1994). Fatal neutropenia associated with long‐term tamoxifen therapy. The Lancet, 344(8921), 541–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Shamseer, L. , Clarke, M. , Ghersi, D. , Liberati, A. , Petticrew, M. , … Stewart, L. A. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta‐analysis protocols (PRISMA‐P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molebatsi, K. , & Olashore, A. A. (2018). Early‐onset psychosis in an adolescent with DiGeorge syndrome: A case report. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 24(1), 1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosheva, M. , Korotkin, L. , Gur, R. E. , Weizman, A. , & Gothelf, D. (2019). Effectiveness and side effects of psychopharmacotherapy in individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome with comorbid psychiatric disorders: A systematic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1–14. 10.1007/s00787-019-01326-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, U. J. , & Fellgiebel, A. (2008). Successful treatment of long‐lasting psychosis in a case of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Pharmacopsychiatry, 41(4), 158–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murad, M. H. , Sultan, S. , Haffar, S. , & Bazerbachi, F. (2018). Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ evidence‐based medicine, 23(2), 60–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer, J. W. (2007). Metabolic considerations in the use of antipsychotic medications: A review of recent evidence. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 68(Suppl 1), 20–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. , Røge, R. , Schjerning, O. , Sørensen, H. J. , & Taylor, D. (2012). Geographical and temporal variations in clozapine prescription for schizophrenia. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 22(11), 818–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hanlon, J. F. , Ritchie, R. C. , Smith, E. A. , & Patel, R. (2003). Replacement of antipsychotic and antiepileptic medication by L‐α‐methyldopa in a woman with velocardiofacial syndrome. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 18(2), 117–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohi, K. , Hashimoto, R. , Yamamori, H. , Yasuda, Y. , Fujimoto, M. , Nakatani, N. , … Takeda, M. (2013). How to diagnose the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: A case report. Annals of General Psychiatry, 12(1), 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perret, L. C. , Lodovighi, M.‐A. , Perret, O. , Ibrahim, E. C. , Philip, N. , Azorin, J.‐M. , & Belzeaux, R. (2017). Treatment of comorbid bipolar disorder improves disabilities and neuropsychological functioning in DiGeorge syndrome: A case report. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 37(6), 736–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praharaj, S. K. , & Sarkar, S. (2010). Velocardiofacial syndrome presenting as chronic mania. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 64(6), 666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronaldson, K. J. , Fitzgerald, P. B. , & McNeil, J. J. (2015). Clozapine‐induced myocarditis, a widely overlooked adverse reaction. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 132(4), 231–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhe, A. M. , Qureshi, I. , & Procaccini, D. (2018). Clozapine‐induced myocarditis in an adolescent male with DiGeorge syndrome. The Mental Health Clinician, 8(6), 313–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rummel‐Kluge, C. , Komossa, K. , Schwarz, S. , Hunger, H. , Schmid, F. , Kissling, W. , … Leucht, S. (2010). Second‐generation antipsychotic drugs and extrapyramidal side effects: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of head‐to‐head comparisons. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 38(1), 167–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev, P. (2002). Schizophrenia‐like illness in velo‐cardio‐facial syndrome: A genetic subsyndrome of schizophrenia? Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53(2), 721–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scambler, P. J. (2000). The 22q11 deletion syndromes. Human Molecular Genetics, 9(16), 2421–2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, M. , Debbané, M. , Bassett, A. S. , Chow, E. W. C. , Fung, W. L. A. , Van Den Bree, M. B. M. , … Kates, W. R. (2014). Psychiatric disorders from childhood to adulthood in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome: Results from the international consortium on brain and behavior in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(6), 627–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte, P. F. J. (2006). Risk of clozapine‐associated agranulocytosis and mandatory white blood cell monitoring. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 40(4), 683–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starling, J. , & Harris, A. W. (2008). Case reports: An opportunity for early intervention: Velo‐cardio‐facial syndrome and psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 2(4), 262–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Z. S. (2003). Psychosis, electrolyte imbalance, and velocardiofacial syndrome. England: Psychosomatics. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven, W. M. A. , & Egger, J. I. M. (2015). Atypical antipsychotics and relapsing psychoses in 22q112 deletion syndrome: A long‐term evaluation of 28 patients. Pharmacopsychiatry, 48(3), 104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voll, S. L. , Boot, E. , Butcher, N. J. , Cooper, S. , Heung, T. , Chow, E. W. C. , … Bassett, A. S. (2017). Obesity in adults with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Genetics in Medicine, 19(2), 204–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wither, R. , MacDonald, A. , Borlot, F. , Butcher, N. , Chow, E. , Bassett, A. , & Andrade, D. (2017). Increased epilepsy prevalence in adults with 22q11 deletion syndrome. Neurology, 88(16), P1. 236. [Google Scholar]

- Wither, R. G. , Borlot, F. , MacDonald, A. , Butcher, N. J. , Chow, E. W. C. , Bassett, A. S. , & Andrade, D. M. (2017). 22q11.2 deletion syndrome lowers seizure threshold in adult patients without epilepsy. Epilepsia, 58(6), 1095–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yacoub, A. , & Aybar, M. (2007). Response to clozapine in psychosis associated with velo‐cardio‐facial syndrome. Psychiatry, 4(5), 14–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1 Table S1: Systematic search strategy

Table S2: Quality assessment trials, cohorts and case–control studies

Table S3: Quality assessment case reports