Abstract

Background:

Pediatric hand fractures are common, but few require surgery; therefore, these fractures are often perceived to be overreferred. Our objective is to systematically identify and describe pediatric hand fracture referring practices.

Method:

A scoping review was performed, searching electronic databases and grey literature up to January 2018 to identify referring practices for children (17 years and younger) with hand fractures (defined as radiographically confirmed fractures distal to the carpus) to hand surgeons. All study designs were included, and study selection and data extraction were independently performed in duplicate by 2 reviewers. Outcomes included referring rates, necessity of referral, referring criteria, and management of fractures.

Results:

Twenty (10 cross-sectional, 7 prospective cohorts, and 3 narrative reviews) studies reporting on referring practices or management of 21,624 pediatric hand fractures were included. Proportion of pediatric hand fractures referred to hand surgeons ranged from 6.5% to 100%. Unnecessary referral, defined as those fractures within the scope of primary care management, ranged from 27% to 78.1%. Ten studies reported referring criteria, with 14 unique criteria identified. The most common referring criteria were displacement (36.4%), loss of joint congruity (36.4%), and instability (36.4%). The most common justification for these criteria was increased likelihood of requiring surgery. The most common initial management was immobilization (66%-100%). Final management was provided by orthopedic or plastic hand surgeons with 0% to 32.9% of fractures requiring surgery.

Conclusion:

Referring practices vary widely in the literature. Major gaps in the literature include objective measures and justification for referring criteria and primary care education on hand fracture referring practices.

Keywords: child, hand fracture, referral, review

Abstract

Historique:

Les fractures de la main sont courantes en pédiatrie, mais rares sont celles qui exigent une opération. C’est pourquoi on a souvent l’impression qu’elles sont trop envoyées en consultation. Les chercheurs avaient comme objectif de déterminer et de décrire systématiquement les pratiques de consultation à cause d’une fracture de la main en pédiatrie.

Méthodologie:

En janvier 2018, dans le cadre d’une analyse exploratoire, les chercheurs ont fouillé les bases de données électroniques et la documentation parallèle pour déterminer les pratiques de consultation de chirurgiens de la main pour les enfants (de 17 ans et moins) victimes de fractures de la main (définies comme des fractures de la partie distale du carpe, confirmées par radiographie). Ils ont inclus toutes les méthodologies, et deux analystes ont chacun effectué toute l’extraction des données. Les résultats incluaient le taux, la nécessité et les critères de consultation ainsi que le traitement des fractures.

Résultats:

Les chercheurs ont inclus 20 études (dix transversales, sept cohortes prospectives, trois examens narratifs) sur les pratiques de consultation ou de prise en charge de 21,624 fractures de la main en pédiatrie. De 6,5 % à 100 % de ces fractures étaient envoyées en consultation à un chirurgien de la main. De 27 % à 78,1 % des consultations étaient inutiles, c’est-à-dire qu’elles pouvaient être traitées en soins primaires. Dix études faisaient état de critères de consultation, pour un total de 14 critères uniques. Ainsi, les principaux critères de consultation étaient un déplacement (36,4 %), la perte de la congruence articulaire (36,4 %) et l’instabilité (36,4 %). La principale justification de ces critères était une plus grande probabilité d’opération. L’immobilisation (66 % à 100 %) demeurait le traitement initial le plus courant. Un chirurgien orthopédique ou plastique de la main effectuait le traitement définitif, et de 0 % à 32,9 % des fractures devaient être opérées.

Conclusion:

Les publications font état de pratiques de consultation très variables. Elles comportent de grandes lacunes, soit l’objectivité des mesures, la justification des critères de consultation retenus et la formation en soins primaires sur les pratiques de consultation en cas de fracture de la main.

Introduction

Pediatric hand fractures are common, with reported incidences of up to 624 pediatric hand fractures per 100 000 patients per year.1 The hand is the most frequently injured body part in children.2-5 Hand fractures are the second most common fracture, accounting for one-fifth of all pediatric fractures.2-5 Incidence of hand fractures increases with age, with peak occurrence coinciding with the onset of puberty and an increased participation in contact sports.2 The growing skeleton has a unique capacity to heal and remodel and the majority of pediatric hand fractures are managed by immobilization with only approximately 10% requiring surgery.3,4,6-13

From the perspective of the referring physician, there are 2 common concerns when managing pediatric hand fractures: diminished hand function and disturbance of the growth plate. Injuries to the hand can result in major functional deficits which may affect expression, work, and play. Before skeletal maturity, the growth plate, or physis, is open and vulnerable to injury. The physis represents an area of weakness compared to the surrounding bone because it is unmineralized and the chondrocytes are vulnerable to disruption through shearing or angular forces.14 While disturbance of bone growth is a major concern for referring physicians, this rarely becomes a real issue, except with Salter Harris type 5 fractures which makeup less than 1% of growth plate fractures.15 However, type 5 injuries are difficult to diagnosis on radiograph and a high degree of clinical suspicion is necessary.

From the perspective of the hand surgeon, pediatric hand fractures may represent a potential misuse of resources because, while common, few require surgery.3,4,6-13 In contrast to adults, hand fractures in children have low morbidity,3-6 as children display quicker recovery from hand injuries and have a low frequency of nonunion.13,16 For these reasons, pediatric hand fractures are often perceived to be overreferred. The underlying assumption is that similar and more appropriate care can be delivered outside of a surgeon’s office at a lower cost. Unnecessary surgeon visits can be a burden to both the health-care system and the patient as these visits place strain on wait-lists, increase hospital costs, and require patient and care giver time. One study of outpatient upper limb fracture pediatric patients quantified the direct cost of attending clinic in 2016 to be equivalent to US$60.24 and the cost to society due to productivity loss to be US$97.37 per consultation. Moreover, although subjectively patients deemed the appointments necessary, only 12.6% of appointments resulted in a change of management.17 Another study found for every 100 appointments, 25 working days were lost and 18 patients lost wages. Among 71 patients, 54 days of school were missed.18

Despite the high incidence of pediatric hand fractures, there is limited evidence for when to refer these fractures and there remains discrepancy between referring and consultant physicians. The American Academy of Pediatric guidelines recommends that complex fractures be referred to a surgeon19,20; however, the term “complex” is ambiguous and potentially difficult to interpret for a physician without specialized hand training. When looking at the adult literature, referring guidelines are also limited, and moreover, application from adult to children may not be appropriate; the pediatric hand is a growing hand and children have developmental constraints that may change splinting and therapy management.

To our knowledge, there is no review that systematically summarizes the evidence regarding pediatric hand fracture referring practices. We used a scoping review methodology to understand the range and types of referring practices. We included both referring and consultant perspectives to inform the future design of pediatric referring recommendations. Specifically, this study’s purpose is to identify and describe referring practices, from primary care physicians to hand surgeons, of radiographically confirmed hand fractures in children 17 years and younger.

Methods and Materials

A scoping review was conducted to capture a broad range of studies and to summarize knowledge from a variety of sources and types of evidence. Using the Joanna Briggs Institute-framework for scoping reviews, we conducted the following: (1) identified the research question, (2) identified relevant studies, (3) completed study selection, (4) charted the data, and (5) collated, summarized, and reported the results.21 In the spirit of a scoping review, this was an iterative process to ensure comprehensive inclusion of literature. This work involved identifying, reviewing, and categorizing data from primary articles and did not involve human participants and was thus exempt from ethics approval.

A broad search of the medical literature to identify all studies and journals that focused on pediatric hand fracture referring practices was conducted including the following online databases: EMBASE, MEDLINE (OVID), PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews with no limitations on date (inception to January 3, 2018) or language of publication. No search filters were used. The search strategy was repeated on Google and Google Scholar searching through the first 5 pages of results for grey literature. The grey literature search strategy was completed within a single session for each search strategy due to the dynamic nature of the Internet. Bibliographies of included studies were searched by hand for other relevant articles. Expert consultation (F.F. and A.H.) was sought to identify any potential ongoing or unpublished studies.

Searches included 2 themes: (1) hand fracture and (2) triage or referring practices. These 2 themes were combined using the Boolean operator “and.” The search strategy was approved by a Health Sciences Librarian (See Online Appendix 1 for Search Strategy).

Level 1 screening was performed for title and abstract. Articles were included if they reported on referring practices or management of hand fractures. Management was purposely included at the level 1 screening because depending on the article perspective, for example, from a primary care or emergency department perspective, referral can be considered management. Nonhuman studies were excluded. The search was not limited by age at this level. All types of articles, including observational, trials, and reviews were considered.

Articles passing the level 1 screening underwent a level 2 screening for full-text review. Articles identified through grey literature and by local specialists were included at this stage. Eligible articles were included for data extraction if they reported on referring practices of hand fractures (defined as distal to the carpus) in patients 17 years or younger. Referrals to hand surgeons included both orthopedic and plastic surgeons. Hand surgery represents an overlap in scope of practice that is dependent of geography; in Canada, hand fractures are primarily managed by plastic surgeons whereas, for example, in the United States, hand fractures are primarily managed by orthopedic surgeons. Articles were excluded if they reported exclusively on adult patients without any pediatric patients or if they reported on hand injuries without fractures.

If a study presented unclear data, the corresponding author was e-mailed and a follow-up e-mail was sent after 2 weeks for nonresponders. Specific reasons for exclusion and inter-rater reliability (calculated using Cohen κ statistic) were determined at the full-text screening phase.

The number of studies included and excluded was summarized using a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart. A data collection form based on the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC) was created to ensure that we were comprehensive in extracting relevant study characteristics and included: general information, eligibility, population and setting, methods, participants, outcomes, results, and applicability.22 Our primary outcome was referring practices, that is: which hand fractures were referred, who referred them, and where they were referred to. Screening and data extraction were performed in duplicate by 2 independent reviewers (R.H. and A.T.). Disagreements were resolved by discussion and obtaining consensus between the 2 reviewers. Data were categorized and reported descriptively. Once collected, data were discussed among reviewers and categorized by themes. As this was a scoping review, no formal quality assessment was required. This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Results

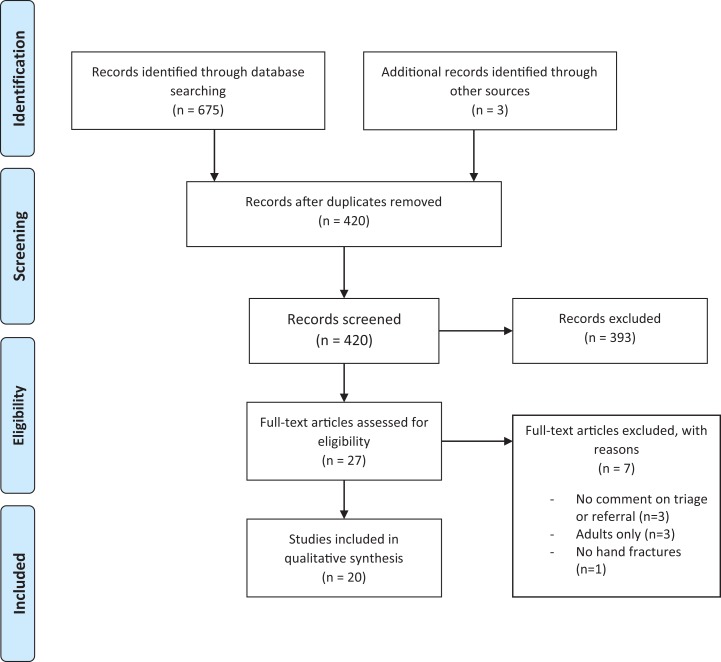

The search strategy identified 675 potential studies and after duplicates were removed, 420 were eligible for level 1 screening (Figure 1). Grey literature search and expert consultation produced 3 additional studies. Twenty seven studies passed title and abstract screening and underwent full-text review. Twenty original studies on pediatric hand fracture referring practices were included in final data extraction and the level 2 screening Cohen κ statistic was 0.823.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

A summary of the study characteristics included in this scoping review is provided in Table 1. The most common study designs were: cross-sectional (50.0%), prospective cohort (35.0%), and narrative review (15.0%). The studies were conducted in 6 countries including: United Kingdom (35.0%), United States (30.0%), and Canada (15.0%). Fourteen (70.0%) studies were published after 2000. Extracted data were organized into 3 main identifiable themes: (1) referring rates and necessity of referrals, (2) referring criteria, and (3) primary care education. One study reported on both referring rates and necessity of referrals and referring criteria; therefore, 21 study themes are reported.23

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Studies Included in Scoping Review.

| Characteristic | Studies (N = 20) |

|---|---|

| Study design | |

| Cross-sectional study | 10 |

| Prospective cohort | 7 |

| Narrative review | 3 |

| Origin of study | |

| United Kingdom | 8 |

| United States | 6 |

| Canada | 3 |

| Netherlands | 1 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 |

| Switzerland | 1 |

| Year of publication | |

| 2009-2017 | 8 |

| 2000-2008 | 6 |

| Prior | 6 |

| Themes | N = 21 |

| Referring rates and necessity of referral | 13 |

| Referring criteria | 5 |

| Primary care education on pediatric hand fractures | 3 |

Fourteen of 20 studies reported exclusively on pediatric patients, while 6 studies reported on adult and pediatric patients. The mean age reported across the pediatric only studies was 7.8 to 11.5 years old. The 20 included studies represented 2 624 hand fractures. One study reported from both the emergency department and a plastic surgery clinic; therefore, 21 locations are reported.24 The most common study location was a surgeon’s clinic (13/21 studies), with 7 studies reported from an orthopedic clinic and 6 studies reported from a plastic surgery clinic. Seven studies reported from the emergency department and one from a community primary care clinic. Patient and fracture demographics across studies were comparable. Single, isolated fractures affecting the fifth digit in male participants from 10 to 15 years of age were most common.3,11,12,25-27

Theme 1: Referring Rates and Necessity of Referrals

Table 2 summarizes the referring rates, necessity of referral, and management. Depending on authorship, referring rates varied: Primary care physicians reported referring rates to hand surgeons of 6.5% to 82.6%8,28-31 and hand surgeons reported referring rates from primary care physicians of 35% to 100%.3,11,23,24,27,32 Five studies commented on necessity of referrals. Of those referred, 27% to 78% were deemed unnecessary.25,26,33,34 Unnecessary referrals were hand fractures within the scope of a primary care physician that did not require management by a hand surgeon; the definition of within the scope of a primary care physician was unique to each study. Ramasubbu et al found that 41% of hand fractures and 38% of finger fractures referred to their clinic were unnecessary as there was no fracture present on radiograph.26 Hsu et al found 22% of phalangeal fractures and 70% of metacarpal fractures referred were unnecessary.34 Hsu et al categorized necessity of referrals as per the American Board of Pediatrics and American Academy of Pediatric Surgery criteria, where nondisplaced phalangeal and metacarpal fractures fall under the realm of primary care.19,20 The most common management by hand surgeons was immobilization, ranging from 66% to 100%.3,10,11,12,24,26 Surgical management ranged from 0% to 32.9%.3,10,11,12,24-26,34 Intra-articular fractures were commonly reported as fractures that required surgery. Davis et al found 44% of intra-articular fractures required secondary operative fixation or splint adjustment,32 and in the study by Stanton et al, intra-articular fractures accounted for 17% of all fractures and 26% of fractures that required surgery.6 Among the intra-articular fractures, unstable proximal interphalangeal joint fractures were noted by studies at increased risk of surgery.3,10,12,24,28,33 Associated soft-tissue injuries, such as amputations8, subluxation or dislocation,10 and neurovascular injuries11 were also reported along with fractures that required surgery.

Table 2.

Referral and Management.

| Sample Size (Hand Fractures) | Referral Rate (%) | Referral Criteria for Fractures | Management (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Total | Inappropriate | Immobilization | Surgery | ||

| Ablove 199835 | NR | NR | NR | Open, intra-articular, displaced or associated with amputation | NR | NR |

| Al-Qattan 2015 | NR | NR | NR | Any involvement of phalangeal neck | NR | NR |

| Anzarut 200723 | 281 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Bhende 19938 | 92 | 82.6 | NR | Open, displaced, complex closeda or association with amputation or nail bed laceration | 95.7 | 4.3 |

| Davis 199032 | 678 | 100 | 27 | All hand fractures should be referred | NR | 2.9 |

| Gornitzky 201625 | 73 | NR | 57 | NR | NR | 27.8 |

| Hill 199829 | 632 | 30.7-31.3 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Hsu 201234 | 529 | NR | 30-78.1 | American Board of Pediatrics and American Academy of Pediatric Surgery Criteriab | NR | 7.2 |

| Larsen 200430 | 28 231 | 41 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Leonard 197010 | 263 | NR | NR | NR | 75 | 10 |

| Liu 201411 | 83 | NR | NR | Unstable, rotated, displaced, intra-articular, compound or short | 84 | 12.0 |

| Mahabir 200112 | 232 | NR | NR | Open, unstable or significant malrotation deformity | 67.1 | 32.9 |

| Murphy 201033 | 1875 | NR | >50 | NR | NR | NR |

| Nofsinger 200228 | NR | NR | NR | Any at “high risk for surgery”c | NR | NR |

| Ramasubbu 201626 | 21 | NR | 38.1 | NR | 100 | 0 |

| Stanton 20076 | 183 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 15 |

| Usal 199231 | 26 | 6.5 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Vadivelu 200627 | 236 | 35 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Weber 200924 | 37 | NR | NR | PIPJ fractures that are unstable on passive testing, associated with dislocations, have fragments >1/3 articular surface or present late (>5 days) | 100 | 0d |

| Young 2013 | 303 | NR | NR | NR | 66 | 5 |

Abbreviations: NR, not recorded; PIPJ, proximal interphalangeal joint; UCL, ulnar collateral ligament.

a Not defined by authors.8

b The American Board of Pediatrics: nondisplaced fractures not requiring reduction or long casts and finger fractures treated with buddy taping or splinting only are within the scope of primary care practice.19 The American Academy of Pediatric Surgery Advisory Panel Guidelines for Referral recommends any child with complex fractures and dislocations be referred.20

c High risk: base of thumb fractures, UCL avulsion fractures or UCL injuries with gross instability, phalangeal neck fractures, displaced middle phalangeal fractures, severe distal phalangeal crush injuries, and distal phalangeal injuries with tendon involvement.28

d Two patients with avulsion fractures of the volar plate with large epiphyseal fragments and subluxation of the PIP had open reduction internal fixations with K-wires and were excluded from the study.24

Theme 2: Referring Criteria

Ten studies reported on referring criteria to a hand surgeon with 14 unique criteria reported (Table 3). The most common criteria included loss of joint congruity (ie, when the fracture involves the joint and fracture fragments are displaced; 36.4%), displacement (when the fracture fragments are not well-aligned in anatomical position; 36.4%), and instability (fractures that continue to be displaced or mal-rotated after a closed reduction; 36.4%). Four studies justified their referring criteria by recommending referral of fractures with a greater likelihood of requiring surgery, the definition of which varied for each study.10-12,28 Only one study encouraged an increase in referring practices; Davis et al found 25% of emergency department hand fracture management to be unsatisfactory and subsequently concluded that all hand fractures should be referred to a surgeon’s clinic.32 Only one study was authored by a primary care physician.8 The most commonly reported criteria—loss of joint congruity and displacement—were each a criterion in only 4 studies. There were 8 criteria that were recommended by only one study each.

Table 3.

Referring criteria, with definition, used by each study.

| Author | Displaced | Joint Incongruity | Unstable | Open | Specific Pattern | Amputated | Malrotated | All | Angulated | Compound | Dislocated | Late | Short |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fragments Not Aligned | Involves Joint and Fragments Displaced | Continued Displacement After CR | Soft Tissue Deficit Over Fracture | As Defined by Authora | Associated With Missing Part of Digit | Rotation on Physical Exam | Any Hand Fracture | Rotation on X-Ray | Fragment Comminution | Associated With Joint Dislocation | Presents After 5+ Days | Decreased Length of Digit | |

| Primary care | |||||||||||||

| Bhende 19938 | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Hand surgeon | |||||||||||||

| Ablove 199835 | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Al-Qattan 2015 | X | ||||||||||||

| Davis 199032 | X | ||||||||||||

| Hsu 201234 | X | ||||||||||||

| Leonard 197010 | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Liu 201411 | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Mahabir 200112 | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Nofsinger 200228 | X | ||||||||||||

| Vadivelu 200627 | |||||||||||||

| Weber 200924 | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| TOTALS | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Theme 3: Primary Care Education

Three studies reported on primary care education for pediatric hand fractures. Two were narrative reviews28,32 and one was a cross-sectional study.23 The narrative reviews were authored by hand surgeons and employed a broad approach to hand fractures. One included how to take a hand history and physical examination.35 Both narratives described hand anatomy, the Salter-Harris classification, and common imaging of the hand. Both described selective management of common hand fractures, such as Boxer fractures and Seymour fractures, including when to refer. One review warned about potential bad outcomes and complications as means for referral justification.28

The cross-sectional study surveyed primary care physicians referring patients to plastic surgery.23 This study was focused on primary care continuing medical education of plastic surgery topics, and its aim was to assess educational needs. Of all plastic surgery referrals, trauma and upper extremity injuries were most common. Hand fractures were identified in both utilization and perceived need’s assessments as areas that primary care physicians required continuing education.

Discussion

This review found referring practices for pediatric hand fractures were not well described in the literature and had considerable variability. This may be related to lack of standardized guidelines for when to refer pediatric hand fractures and individual institute’s referring culture. Our findings are similar to prior studies reporting that few pediatric hand fractures require surgical management and referring patterns for hand fractures have not been driven by evidence.

Regarding referring criteria, there were 6 criterion that were recommended by only one study each demonstrating a lack of consensus among studies. Some criteria were rater-dependent. For example, displacement, defined as fracture fragments that are not well-aligned in anatomical position, is rater-dependent. Where one physician’s interpretation of malaligned may be 1 mm of displacement or more, another physician’s interpretation may be 3 mm or more. Moreover, radiographic measurement of fracture displacement has been proven to have poor inter-rater reliability.36 There was a paucity of referring criteria authored by primary care physicians and the discrepancy of criteria when categorized by authorship represents a disconnect between referring and consulting doctors. These 2 results may account for the high percentage of referrals deemed unnecessary by hand surgeons.

The most common justification for referring criteria was increased likelihood of requiring surgery. An important consideration is whether “likelihood of requiring surgery” is an adequate outcome measure. While it is important to refer fractures that will require surgery, there may be other nonsurgical fractures that warrant specialty care. For example, a fracture that initially appears anatomically aligned, but due to location and fracture pattern is prone to slipping may be best managed with close follow-up, serial radiographs, and clinical examination. Distinguishing these fractures from stable, nondisplaced fractures can be difficult. These fractures should be referred to a hand surgeon, but initial radiographs can appear innocuous to the nonspecialist. Thus, a more inclusive definition than increased likelihood of requiring surgery should be considered when justifying referring practices of pediatric hand fractures.

There were only 3 studies whose theme focused on education for primary care physicians on pediatric hand fractures. These were authored by hand surgeons and only one study incorporated primary care physicians’ perspectives. Discussion by an integrated management team with input from both referring and consulting physicians as well as patients might result in development of a better approach to “whole person care” of this patient group. This study highlights the need for more research into efficient and effective management of pediatric hand fractures, including educational and resource support for referring physicians.

Thus, pediatric hand fractures referring practices represent a potential area for investigation and research. This study addresses important knowledge gaps in terms of optimal utilization of health-care resources and manpower, which is in alignment with the national Choosing Wisely Canada campaign,37 whereby clinicians and patients are engaged in conversations pertaining to unnecessary diagnostic tests, referrals and treatments, and encourage health-care professionals to make smart and effective care choices.

Strengths of our study include the comprehensive nature of our search and inclusion of all study designs. There are 2 main limitations of this review: first, this review cannot provide recommendations for “best” referring criteria as the individual studies included in this review did not evaluate the necessary outcomes. The second is the inclusion of heterogenous study designs and outcomes. To address wide variance in outcome data, the 2 reviewers used the standardized EPOC tool to independently extract data.22 Quantitative data were also presented as ranges, as meta-analysis would not have been possible.

Conclusion

Overall, there is considerable variation in referring practices for pediatric hand fractures with respect to proportion referred, criteria for referring, and which referrals were unnecessary. Major gaps in the literature include objective parameters and evidence-based justification for referring criteria. Future research should be aimed at incorporating statistical analysis for the identification of objective parameters predictive of fractures that require specialist management.

Supplemental Material

Appendix_1 for Pediatric Hand Fracture Referring Practices: A Scoping Review by Rebecca L. Hartley, Anna R. Todd, Alan R. Harrop and Frankie O. G. Fraulin in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, Appendix_2_-_PRISMA_Checklist for Pediatric Hand Fracture Referring Practices: A Scoping Review by Rebecca L. Hartley, Anna R. Todd, Alan R. Harrop and Frankie O. G. Fraulin in Plastic Surgery

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Drs Ceilidh-Anne Kinlin, Josh Lam, and Claire Temple-Oberle as well as Karen Hulin-Poli for their contributions to this manuscript. The University of Calgary librarian, Dr. Helen Lee Robertson, was instrumental in refining the search strategy.

Level of Evidence: Level 2, Therapeutic

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Rebecca Hartley receives funding through the Clinical Investigator Program at the University of Calgary.

ORCID iD: Rebecca L. Hartley, MD  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4226-4162

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4226-4162

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Landin LA. Fracture patterns in children. {Analysis} of 8,682 fractures with special reference to incidence, etiology and secular changes in a {Swedish} urban population 1950-1979. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1983;202:1–109. doi:10.3109/17453678309155630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cooper C, Dennison EM, Leufkens HGM, Bishop N, van Staa TP. Epidemiology of childhood fractures in Britain: a study using the general practice research database. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(12):1976–1981. doi:10.1359/JBMR.040902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Young K, Greenwood A, MacQuillan A, Lee S, Wilson S. Paediatric hand fractures. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2013;38(8):898–902. doi:10.1177/1753193412475045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barton NJ. Fractures of the phalanges of the hand in children. Hand. 1979;11(2):134–143. doi:10.1016/S0072-968X(79)80025-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hastings H 2nd, Simmons BP. Hand fractures in children. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;1(188):120–130. doi:10.1097/00003086-198409000-00015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stanton JS, Dias JJ, Burke FD. Fractures of the tubular bones of the hand. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2007;32(6):626–636. doi:10.1016/j.jhse.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Worlock PH, Stower MJ. The incidence and pattern of hand fractures in children. J Hand Surg Am. 1986;11(2):198–200. doi:10.1016/0266-7681(86)90259-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bhende MS, Dandrea LA, Davis HW. Hand injuries in children presenting to a pediatric emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22(10):1519–1523. doi:S0196-0644(05)81251-X [pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fetter-Zarzeka A, Joseph MM. Hand and fingertip injuries in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18(5):341–345. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?.T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med4&NEWS=N&AN=12395003. Accessed December 21, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leonard MH, Dubravcik P. Management of fractures fingers in the child.pdf. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1970;73:160–168. Accessed December 21, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu EH, Alqahtani S, Alsaaran RN, et al. A prospective study of pediatric hand fractures and review of the literature. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(5):299–304. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mahabir RC, Kazemi AR, Cannon WG, Courtemanche DJ. Pediatric hand fractures: a review. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2001;17(3):153–156. doi:10.1097/00006565-200106000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Valencia J, Leyva F, Gomez-Bajo GJ. Pediatric hand trauma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(432):77–86. doi:10.1097/01.blo.0000155376.88317.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nellans KW, Chung KC. Pediatric hand fractures. Hand Clin. 2013;29(4):569–578. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bentz ML, Bauer BS, Zuker R. Principles And Practice Of Pediatric Plastic Surgery. Thieme; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lindley SG, Rulewicz G. Hand fractures and dislocations in the developing skeleton. Hand Clin. 2006;22(3):253–268. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holm AGV, Luras H, Randsborg PH. The economic burden of outpatient appointments following paediatric fractures. Injury. 2016;47(7):1410–1413. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morris MWJ, Bell MJ. The socio-economical impact of paediatric fracture clinic appointments. Injury. 2006;37(5):395–397. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chapel Hill N. The american board of pediatrics: a guide to evaluating your clinical competence. Am Board Pediatr. 2011. http://www.aap.org.

- 20. Panel SA. Guidelines for referral to pediatric surgical specialists. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1 Pt 1):187–191. doi:10.1542/peds.110.1.187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. The Joanna Briggs Institute. Guidance for conduct of JBI scoping reviews In: Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Maunal. Joanna Briggs Institute Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences The University of Adelaide; 2015: Chapter 11. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004. [Google Scholar]

- 22. The Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). Data Collection Form. EPOC Resour Rev authors. 2017. http://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors. Accessed December 21, 2017.

- 23. Anzarut A, Singh P, Cook G, Domes T, Olson J. Continuing medical education in emergency plastic surgery for referring physicians: a prospective assessment of educational needs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(6):1933–1939. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000259209.56609.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weber DM, Kellenberger CJ, Meuli M. Conservative treatment of stable volar plate injuries of the proximal interphalangeal joint in children and adolescents: a prospective study. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25(9):547–549. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181b4f471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gornitzky AL, Milby AH, Gunderson MA, Chang B, Carrigan RB. Referral patterns of emergent pediatric hand injury transfers to a tertiary care center. Orthopedics. 2016;39(2):e333–e339. doi:10.3928/01477447-20160222-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ramasubbu B, McNamara R, Deiratany S, Okafor I. An evaluation of the accuracy and necessity of fracture clinic referrals in a busy pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2016;32(2):69–70. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000000473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vadivelu R, Dias JJ, Burke FD, Stanton J. Hand injuries in children: a prospective study. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26(1):29–35. doi:10.1097/01.bpo.0000189970.37037.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nofsinger CC, Wolfe SW. Common pediatric hand fractures. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2002;14(1):42–45. doi:10.1097/00008480-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hill C, Riaz M, Mozzam A, Brennen MD. A regional audit of hand and wrist injuries. A study of 4873 injuries. J Hand Surg Am. 1998;23B(2):196–200. doi:10.1016/S0266-7681(98)80174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Larsen CF, Mulder S, Johansen AMT, Stam C. The epidemiology of hand injuries in the Netherlands and Denmark. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19(4):323–327. doi:10.1023/B:. EJEP.0000024662.32024.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Usal H, Beattie T. An audit of hand injuries in a paediatric accident and emergency department. Health Bull (Raleigh). 1992;50(4):285–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Davis TRC, Stothard J. Why all finger fractures’shouldbe referred ∼0 a hand surgery service: a prospective study of primary management. J Hand Surg Am. 1990;15(3):299–302. http://journals.sagepub.com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/doi/pdf/10.1016/0266-7681_90_90008-R. Accessed August 22, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Murphy SM, Whately K, Eadie PA, Orr DJ. Unnecessary inter-hospital referral of minor hand injuries: a continuing problem. Ir J Med Sci. 2010;179(1):123–125. doi:10.1007/s11845-009-0416-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hsu EY, Schwend RM, Julia L. How many referrals to a pediatric orthopaedic hospital specialty clinic are primary care problems? J Pediatr Orthop. 2012;32(7):732–736. doi:10.1097/BPO.0b013e31826994a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ablove RH, Moy OJ, Peimer CA. Pediatric hand disease. diagnosis and treatment. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1998;45(6):1507-x. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?.T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med4&NEWS=N&AN=9889764. Accessed December 21, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lamraski G, Monsaert A, De Maeseneer M, Haentjens P. Reliability and validity of plain radiographs to assess angulation of small finger metacarpal neck fractures: human cadaveric study. J Orthop Res. 2006;24(1):37–45. doi:10.1002/jor.20025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Association CM. Choosing Wisely Canada. [website] Ottawa, ON: choosingwiselycanada.org. 2014. Accessed July 11, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix_1 for Pediatric Hand Fracture Referring Practices: A Scoping Review by Rebecca L. Hartley, Anna R. Todd, Alan R. Harrop and Frankie O. G. Fraulin in Plastic Surgery

Supplemental Material, Appendix_2_-_PRISMA_Checklist for Pediatric Hand Fracture Referring Practices: A Scoping Review by Rebecca L. Hartley, Anna R. Todd, Alan R. Harrop and Frankie O. G. Fraulin in Plastic Surgery