Abstract

PURPOSE:

The aim of the current study was to assess whether the quality of patient–provider communication on key elements of cancer survivorship care changed between 2011 and 2016.

METHODS:

Participating survivors completed the 2011 or 2016 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Experiences with Cancer Surveys (N = 2,266). Participants reported whether any clinician ever discussed different aspects of survivorship care. Responses ranged from “Did not discuss at all” to “Discussed it with me in detail”. Distributions of responses were compared among all respondents and only among those who had received cancer-directed treatment within 3 years of the survey.

RESULTS:

In 2011, the percentage of survivors who did not receive detailed instructions on follow-up care, late or long-term adverse effects, lifestyle recommendations, and emotional or social needs were 35.1% (95% CI, 31.9% to 38.4%), 54.2% (95% CI, 50.7% to 57.6%), 58.9% (95% CI, 55.3% to 62.5%), and 69.2% (95% CI, 65.9% to 72.3%), respectively, and the corresponding proportions for 2016 were 35.4% (95% CI, 31.9% to 37.8%), 55.5% (95% CI, 51.7% to 59.3%), 57.8% (95% CI, 54.2% to 61.2%), and 68.2% (95% CI, 64.3% to 71.8%), respectively. Findings were similar among recently treated respondents. Only 24% in 2011 and 22% in 2016 reported having detailed discussions about all four topics. In 2016, 47.6% of patients (95% CI, 43.8% to 51.4%) reported not having detailed discussions with their providers about a summary of their cancer treatments.

CONCLUSION:

Clear gaps in the quality of communication between survivors of cancer and providers persist. Our results highlight the need for continued efforts to improve communication between survivors of cancer and providers, including targeted interventions in key survivorship care areas.

INTRODUCTION

The number of survivors of cancer in the United States is increasing and expected to exceed 20 million by 2026.1 In addition to the fear of recurrence, many survivors of cancer experience residual symptoms and other long-term effects of the cancer and its treatment, such as fatigue and distress.1,2 Survivors of cancer also face a higher risk than the general public of new, biologically distinct cancers.3,4 Given the complex physical, psychosocial, social, and spiritual needs of this population, the increasing number of survivors of cancer underscores the growing need to address the information and care gaps faced by survivors, such as those highlighted in the Institute of Medicine’s 2006 report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition.5 The seminal report recommended survivorship care planning to facilitate care coordination among survivors, cancer specialists, and primary care providers (PCPs) in addressing late or long-term adverse effects, emotional and social needs, and healthy lifestyles. The report also suggested patients receive a written and communicated survivorship care plan (SCP) that summarizes their diagnosis and treatment, describes possible late effects, and delineates a follow-up care plan that incorporates available evidence-based standards of care.6 The SCP was envisioned as a tool to deliver patient-centered care by facilitating patient–provider communication.

Patient–provider communication is central to the delivery of high-quality, patient-centered care, which has been associated with improved adherence, satisfaction, and self-management,7 and aligns with the core principals of medical ethics.8 In a nationally representative survey of survivors of cancer conducted in 2011, nearly one half of patients reported that they had never had a detailed discussion with any provider about late or long-term adverse effects, emotional and social needs, or lifestyle recommendations, and more than one quarter of patients reported not having a detailed discussion about follow-up care.9 Since that time, several guidelines have been issued and policies instituted aimed at improving the quality of survivorship care planning. Of note, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, American Cancer Society, and ASCO have issued guidelines for survivorship care.10-22 Resources for developing SCPs also have been developed by individual medical centers and organizations, such as LIVESTRONG and the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship,17,23 and the implementation of SCPs has attracted much research.24-26 In 2012, the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer (CoC) —a leading accreditation body that establishes standards to ensure quality, multidisciplinary, and comprehensive cancer care delivery in health care settings—developed multiple standards aimed at improving survivorship care and mandated the use of SCPs in organizations seeking accreditation (standard 3.3).27 To maintain accreditation, CoC required cancer programs to offer SCPs to 25% of eligible patients by the end of 2016, with a goal by the end of 2018 of 50% (lowered from the original goal of 75%).27-29

In this descriptive study, we use data from both the 2011 and 2016 Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS) Experiences with Cancer survey to assess whether the quality of patient–provider communications regarding key elements of survivorship care has improved over time.

METHODS

Data Source and Study Sample

MEPS is a nationally representative household survey of a US civilian noninstitutionalized population on health care utilization and costs. The 2011 and 2016 MEPS included a self-administered questionnaire—the Experiences with Cancer Survey—that specifically targets survivors of cancer age 18 years and older. This questionnaire was designed to enable a detailed assessment of the burden of cancer, including the impact of cancer and its treatment on access to health care, the ability to work and participate in usual activities, health insurance, patient–provider communication, and quality of life.30 The overall response rate for the MEPS was 54.9% in 2011 and 46% in 2016. Among MEPS respondents who were eligible to complete the Experiences with Cancer Survey, response rate was 90% in 2011 and 81.2% in 2016. We excluded those respondents whose sole cancer diagnosis was a nonmelanoma skin cancer, as has been done elsewhere.9 Our analytic sample consisted of 1,202 and 1,064 survivors from 2011 and 2016, respectively.

Measures

The survey asked: “At any time since you were first diagnosed with cancer, did any doctor or other health care provider, ever discuss with you: The need for regular follow-up care and monitoring even after completing your treatment? Late or long-term [adverse] effects of cancer treatment you may experience over time? Your emotional or social needs related to your cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effects of that treatment? Lifestyle or health recommendations[,] such as diet, exercise, [or] quitting smoking? and A summary of all the cancer treatments you received? (2016 only)”. There were four possible responses to each question: “Discussed it with me in detail”, “Briefly discussed it with me”, “Did not discuss it at all”, or “I don’t remember”.

Respondent characteristics included age (18 to 44 years, 45 to 49 years, 50 to 54 years, 55 to 59 years, 60 to 64 years, 65 to 69 years, 70 to 74 years, and ≥ 75 years), sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, others), marital status (currently married, others), education (less than high school, high school, college, advanced degree), income level (low, middle, and high income categorized as ≤ 124%, 125% to 399%, and ≥ 400% of the Federal poverty line, respectively), insurance coverage (any private, public only, uninsured), usual source of care (yes/no), number of comorbidities (0, 1, 2, 3, ≥ 4; derived from eight self-reported ailments: arthritis, asthma, cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, emphysema, hypertension, and myocardial infarction), time since last cancer treatment (currently receiving treatment, < 1 year, 1 to 3 years, 3 to 5 years, > 5 years, never treated, and treatment status not ascertained), and cancer type (colon, prostate, breast, uterus, other).

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics were stratified by the year of the survey. Weighted distributions of responses to questions about survivorship care discussions in 2011 and 2016 were compared in the entire sample and the subset of respondents who had received cancer-directed treatment within 3 years of the survey. Proportional distributions of each response type and the not ascertained/refused category were graphically examined across the years of the survey. For statistical comparisons, we dichotomized these responses about communication quality into two categories: “Discussed with me in detail” versus “Briefly discussed it with me”, “Did not discuss it at all”, or “I don’t remember”. In additional analyses, we reclassified responses about communication quality as any discussion (“Discussed with me in detail” or “Briefly discussed it with me”) versus no discussion (“Did not discuss it at all” or “I don’t remember”). Respondents in the not ascertained/refused category were excluded from statistical comparisons. We conducted χ2 tests of independence in the entire sample and the recent treatment subset to examine whether the proportion of respondents in the two categories varied by the year of the survey. All analyses were conducted using Stata/IC 14 software (STATA, College Station, TX; Computing Resource Center, Santa Monica, CA) and accounted for the complex MEPS survey design.

RESULTS

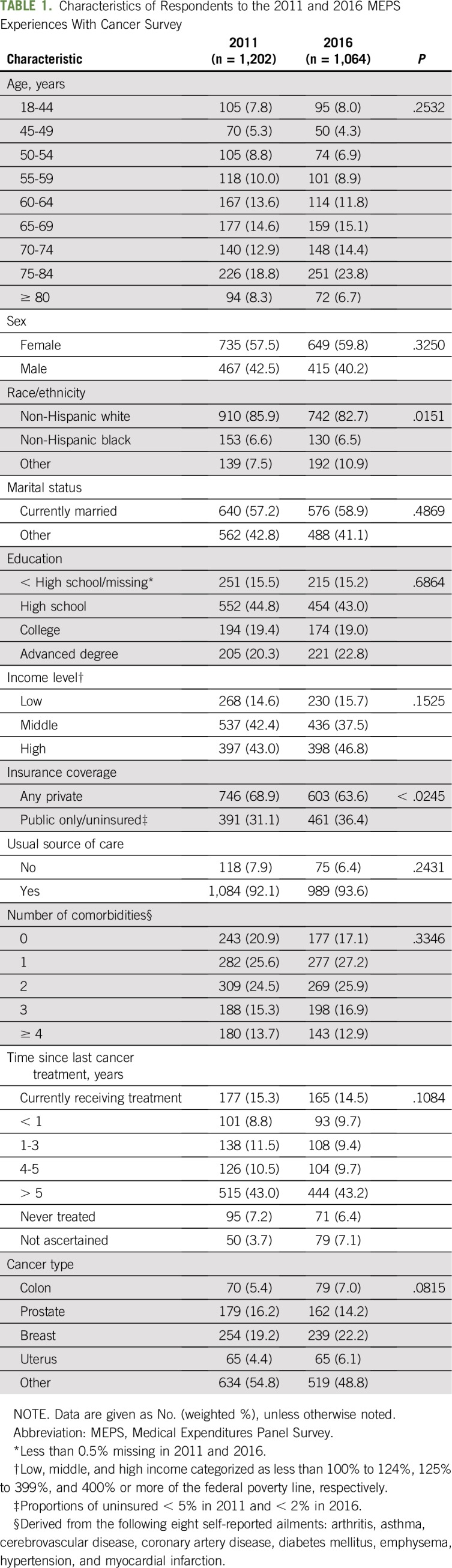

Descriptive statistics are listed in Table 1. The majority of respondents were female, non-Hispanic white, and married. There were only minor differences in the distributions of respondent characteristics between 2011 and 2016.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Respondents to the 2011 and 2016 MEPS Experiences With Cancer Survey

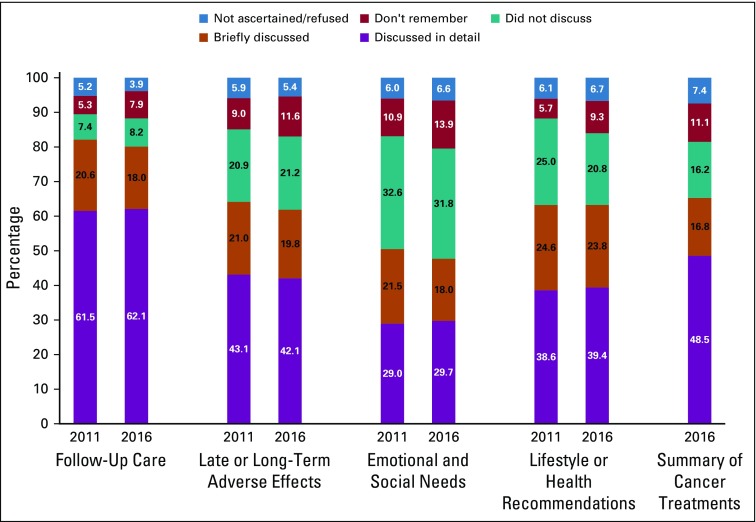

Distributions of responses to questions about key elements of survivorship care were similar in 2011 and 2016 (Fig 1). Proportions of respondents who did not receive detailed discussions—that is, received brief or no discussion—about key elements of survivorship care were statistically similar across the years of the survey. Specifically, the proportions of respondents who did not report detailed discussions about follow-up care were 35.1% in 2011 (95% CI, 31.9% to 38.4%) and 35.4% in 2016 (95% CI, 31.9% to 37.8%). In 2011, the proportion of patients who did not have detailed discussions about late or long-term adverse effects of treatment was 54.2% (95% CI, 50.7% to 57.6%) and healthy lifestyle or behavior change recommendations 58.9% (95% CI, 55.3% to 62.5%). Similar proportions were observed for 2016 at 55.5% (95% CI, 51.7% to 59.3%) and 57.8% (95% CI, 54.2% to 61.2%), respectively. The proportions of those who reported not having detailed conversations about emotional or social needs related to cancer or its treatment were 69.2% (95% CI, 65.9% to 72.3%) in 2011 and 68.2% (95% CI, 64.3% to 71.8%) in 2016. Of patients, 24.4% (95% CI, 21.6% to 27.4%) and 21.9% (95% CI, 18.9% to 25.2%) had detailed discussions about all four content areas in 2011 and 2016, respectively. In each year, follow-up care was discussed in detail most frequently, whereas detailed conversations about emotional and social needs were least frequent. Proportions of respondents who did not report any discussion about the four content areas also were statistically similar in 2011 and 2016 (Table 2).

Fig 1.

Patient-provider discussions of key aspects of survivorship care quality.

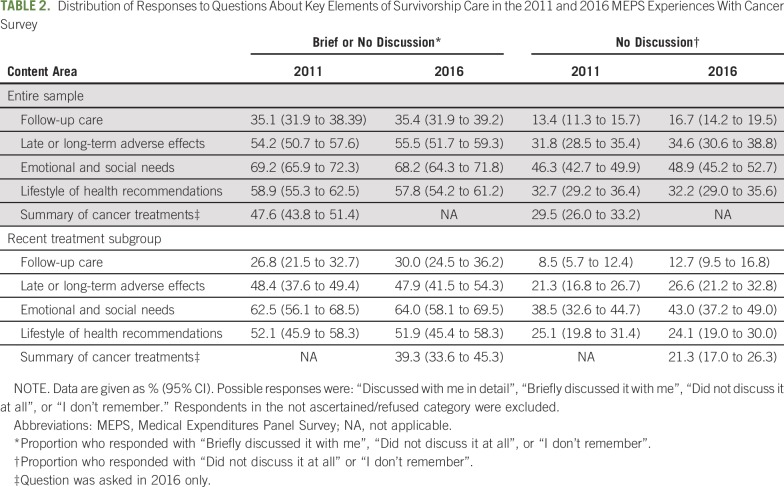

TABLE 2.

Distribution of Responses to Questions About Key Elements of Survivorship Care in the 2011 and 2016 MEPS Experiences With Cancer Survey

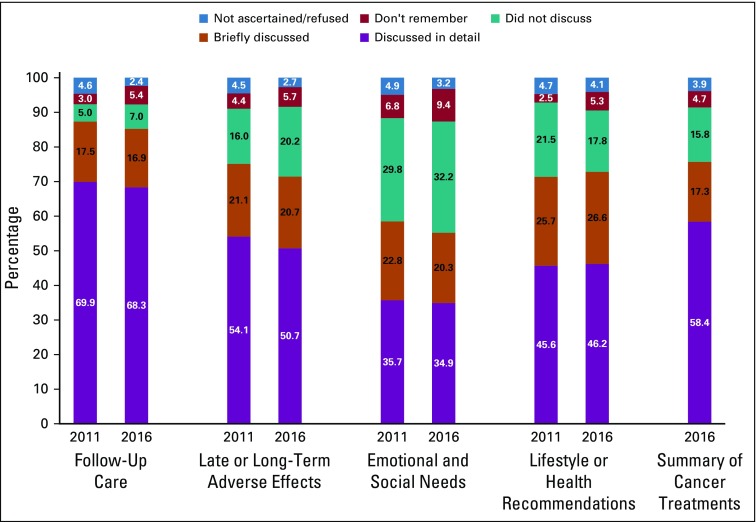

These distributions of responses changed marginally when samples were restricted to survivors of cancer who were treated within the past 3 years (416 and 366 respondents in 2011 and 2016, respectively), but remained similar across survey years (Fig 2 and Table 2).

Fig 2.

Patient-provider discussions of key aspects of survivorship care quality among survivors treated within 3 years of the survey.

In the 2016 survey, 47.6% (95% CI, 43.8% to 51.4%) of the sample did not have detailed discussions about a summary of their cancer treatments.

DISCUSSION

We found that the frequency of patient–provider discussions about key elements of survivorship care did not change considerably between 2011 and 2016, with only one quarter of survivors reporting detailed discussions on all four topics—follow-up care, late and long-term effects, emotional/social needs, and healthy lifestyle. In addition, in 2016, approximately one half of respondents did not have detailed discussions with their providers about a treatment summary, corroborating concerns about survivorship care delivery and the dissemination of treatment summaries that were raised in a previous analysis of the Health Information National Trends Survey fielded between October 2012 and January 2013.31

These findings fall short of our expectations, given the national efforts and organizations promoting survivorship care planning, which highlights the need for improved quality of survivorship care delivery, including the 2012 CoC mandate on SCPs as a standard for accreditation and several guidelines on survivorship care issued by National Comprehensive Cancer Network, American Cancer Society, and ASCO between 2011 and 2015.11-16,18,19,27 More research is required to validate our findings and identify best practices for patient–provider communication, both at the population level and at point of care.

The multimodal nature of cancer therapy requires that many patients with cancer see multiple providers. Thus, concomitant medical needs that involve other, noncancer generalists and specialists may make coordination of care across the cancer control continuum particularly challenging. Inadequate flow of information among providers, in turn, may impede the quality of patient–provider communication and may help to explain the suboptimal communication identified in the current study. Gaps in communication may become pronounced when a survivor’s care management and oversight passes to the PCP.32 It has been reported that many PCPs do not consider survivors of cancer as a distinct patient population, have difficulties identifying them through electronic health record (EHR), or receive limited information regarding their guideline-consistent follow-up.33

Our findings provide preliminary insights into the effects of policy changes, including the CoC mandate on SCPs, as they pertain to patient–provider communication about key areas of survivorship care. The SCP is intended to facilitate communication and coordination between the oncology team, other specialists, PCPs, and the patient; however, implementing SCPs in practice has had challenges. Crucial issues regarding the implementation of SCPs include a lack of standardized models of survivorship care, uncertainty about the timing and mode of plan delivery, and lack of clarity regarding how to integrate treatment plans and summaries into the care workflow and EHRs.34,35 Other challenges include clinician time required to create SCPs, lack of reimbursement for this time, and the lack of evidence that SCPs improve outcomes.19,34,36,37 Concerns also have been raised about an overemphasis on the means—the documentation and distribution of SCPs—but an insufficient focus on the ends: streamlining care and improving communication about sequelae of cancer, its treatment, and other vital aspects of follow-up.37

Providers and policymakers could address these challenges systematically to support care coordination and the delivery of comprehensive survivorship care. Of note, there is limited guidance on the optimal ways with which to identify and address survivors’ late or long-term adverse effects, emotional and social needs, and issues engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviors throughout treatment and follow-up care across diverse cancer types, treatments, provider types, and demographic and sociocultural settings. Given these diversities, a one-size-fits-all approach may not be feasible. Instead, communication strategies should be tailored to the specific context in which survivorship care is delivered. To achieve this, greater emphasis should be placed on communication skills training for providers oriented toward cancer survivorship care planning as well as the development and dissemination of decision aids for clinicians to facilitate patient-centered communication. With a growing number of survivors of cancer being moved to primary care, there is a need to extend these training opportunities to PCPs.38 In general, PCPs should be better integrated with the survivorship care paradigm to facilitate care coordination and the flow of information during and after the transition of care via electronic consultations or agreements between PCPs and oncologists.

The SCP is a potentially important tool for promoting communication about survivorship issues. Yet focusing exclusively on the documentation and dissemination of SCPs may not be productive.37 More attention is needed on how to implement the vision behind the SCP. Optimal uses of health information technology may need to be explored in this regard. EHRs could play a key role in survivorship care by being continuously updated to reflect survivors’ evolving communication needs.39 Health information technology could be used in multiple other ways to streamline the collection and dissemination of information while minimizing the burden on providers’ time. The functionality of EHRs could be enhanced to issue communication prompts during visits and capture the contents of communication within visit notes which could be shared with survivors. Dropdown lists and other attributes within survivors’ EHR portals could serve as important resources of information about sequelae of cancer, its treatment, and other vital aspects of follow-up. Looking ahead, research could strengthen the evidence base for best practices in communication with survivors of cancer targeted toward better implementation of these services and informing their appropriate reimbursement.

This study has some limitations. First, the data were self-reported, and with most respondents being long-term survivors of cancer, there is a potential for recall bias. However, our findings were consistent when restricted to more recently treated survivors of cancer, and questions pertained to any provider at any time since diagnosis. This comprehensive view of patient–provider communication is pertinent, given that survivors face increased risk of chronic health conditions and additional cancers across their care continuum.40-42 Second, our ability to assess the effects of more recent efforts to improve survivorship care was limited. These efforts include the policy mandating increased dissemination of SCPs for CoC accreditation of cancer programs by the end of 2018, and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ implementation of the Oncology Care Model, which provides incentives for furnishing services that are aimed at improving the care experience for patients undergoing systemic treatment of cancer (the 5-year performance period for the model began in July 2016).29,43-45 Indeed, some responses even among recently treated survivors from the 2016 survey may pertain to discussions that took place before the implementation of policies and guidelines issued between 2011 and 2015.

These limitations notwithstanding, to our knowledge, this is the first descriptive analysis of trends in patient perception of the quality of communication about key aspects of survivorship care in a nationally representative sample of survivors of cancer. Our results suggest that continued efforts are needed to improve communication between survivors of cancer and providers, including the implementation and evaluation of targeted interventions in key survivorship care areas. Future research should assess patient- and provider-level barriers to communication about cancer survivorship through both prospective and retrospective evaluations and examine potential differences in communication by race/ethnicity, cancer type, and stage.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Institutes of Health.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Ashish Rai, Neetu Chawla, Xuesong Han, Janet de Moor, Karen R. Yabroff

Collection and assembly of data: Ashish Rai

Data analysis and interpretation: Ashish Rai, Xuesong Han, Sun Hee Rim, Tenbroeck Smith, Janet de Moor, Karen R. Yabroff

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Has the Quality of Patient–Provider Communication About Survivorship Care Improved?

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jop/site/ifc/journal-policies.html.

Janet de Moor

Employment: Biogen (I)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Biogen (I)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:271–289. doi: 10.3322/caac.21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayer DK, Nasso SF, Earp JA. Defining cancer survivors, their needs, and perspectives on survivorship health care in the USA. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e11–e18. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30573-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Ries LA, et al. Multiple cancer prevalence: A growing challenge in long-term survivorship. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:566–571. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weir HK, Johnson CJ, Ward KC, et al. The effect of multiple primary rules on cancer incidence rates and trends. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27:377–390. doi: 10.1007/s10552-016-0714-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine National Research Council . From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine Cancer survivorship care planning. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2005/From-Cancer-Patient-to-Cancer-Survivor-Lost-in-Transition/factsheetcareplanning.pdf

- 7.Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: A systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70:351–379. doi: 10.1177/1077558712465774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braddock CH, III, Snyder L, Neubauer RL, et al. The patient-centered medical home: An ethical analysis of principles and practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:141–146. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2170-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chawla N, Blanch-Hartigan D, Virgo KS, et al. Quality of patient-provider communication among cancer survivors: Findings from a nationally representative sample. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:e964–e973. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.006999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ajani JA, D’Amico TA, Almhanna K, et al. Gastric cancer, version 3.2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14:1286–1312. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bower JE, Bak K, Berger A, et al. Screening, assessment, and management of fatigue in adult survivors of cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1840–1850. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.4495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denlinger CS, Carlson RW, Are M, et al. Survivorship: Introduction and definition. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:34–45. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Denlinger CS, Ligibel JA, Are M, et al. Survivorship: Nutrition and weight management, version 2.2014. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014;12:1396–1406. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Shami K, Oeffinger KC, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society colorectal cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:428–455. doi: 10.3322/caac.21286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, et al. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1941–1967. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ligibel JA, Denlinger CS. New NCCN guidelines for survivorship care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(suppl):640–644. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LIVESTRONG Foundation Your survivorship care plan. https://www.livestrong.org/we-can-help/healthy-living-after-treatment/your-survivorship-care-plan

- 18.Loren AW, Mangu PB, Beck LN, et al. Fertility preservation for patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2500–2510. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayer DK, Nekhlyudov L, Snyder CF, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical expert statement on cancer survivorship care planning. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:345–351. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paice JA, Portenoy R, Lacchetti C, et al. Management of chronic pain in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3325–3345. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Resnick MJ, Lacchetti C, Penson DF. Prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines: American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline endorsement. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:e445–e449. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.004606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skolarus TA, Wolf AM, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship Planning your patient’s care. https://www.canceradvocacy.org/resources/tools-for-care-providers/planning-your-patients-care/

- 24.Birken SA, Clary AS, Bernstein S, et al. Strategies for successful survivorship care plan implementation: Results from a qualitative study. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:e462–e483. doi: 10.1200/JOP.17.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birken SA, Presseau J, Ellis SD, et al. Potential determinants of health-care professionals’ use of survivorship care plans: A qualitative study using the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2014;9:167. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0167-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayer DK, Birken SA, Chen RC. Avoiding implementation errors in cancer survivorship care plan effectiveness studies. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3528–3530. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.6937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer . Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer Cancer program standards: Ensuring patient-centered care. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/2016%20coc%20standards%20manual_interactive%20pdf.ashx

- 29.American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer Important information regarding CoC survivorship care plan standard. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/news/survivorship

- 30.Yabroff KR, Dowling E, Rodriguez J, et al. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) experiences with cancer survivorship supplement. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:407–419. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0221-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blanch-Hartigan D, Chawla N, Beckjord EI, et al. Cancer survivors’ receipt of treatment summaries and implications for patient-centered communication and quality of care. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98:1274–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grunfeld E, Earle CC. The interface between primary and oncology specialty care: Treatment through survivorship. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010:25–30. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubinstein EB, Miller WL, Hudson SV, et al. Cancer survivorship care in advanced primary care practices: A qualitative study of challenges and opportunities. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1726–1732. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCabe MS, Bhatia S, Oeffinger KC, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: Achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:631–640. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tevaarwerk AJ, Hocking WG, Buhr KA, et al. A randomized trial of immediate versus delayed survivorship care plan receipt on patient satisfaction and knowledge of diagnosis and treatment. Cancer. 2019;125:1000–1007. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobsen PB, DeRosa AP, Henderson TO, et al. Systematic review of the impact of cancer survivorship care plans on health outcomes and health care delivery. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2088–2100. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.77.7482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parry C, Kent EE, Forsythe LP, et al. Can’t see the forest for the care plan: A call to revisit the context of care planning. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2651–2653. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.4618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nekhlyudov L, O’malley D M, Hudson SV. Integrating primary care providers in the care of cancer survivors: Gaps in evidence and future opportunities. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e30–e38. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30570-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kline RM, Arora NK, Bradley CJ, et al. Long-term survivorship care after cancer treatment: Summary of a 2017 National Cancer Policy Forum workshop. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:1300–1310. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donin N, Filson C, Drakaki A, et al. Risk of second primary malignancies among cancer survivors in the United States, 1992 through 2008. Cancer. 2016;122:3075–3086. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edwards BK, Noone AM, Mariotto AB, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2010, featuring prevalence of comorbidity and impact on survival among persons with lung, colorectal, breast, or prostate cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:1290–1314. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guy GP, Jr, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Economic burden of chronic conditions among survivors of cancer in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2053–2061. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.9716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Oncology care model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/oncology-care/

- 44.Kline R, Adelson K, Kirshner JJ, et al. The oncology care model: Perspectives from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and participating oncology practices in academia and the community. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:460–466. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_174909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kline RM, Bazell C, Smith E, et al. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Using an episode-based payment model to improve oncology care. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:114–116. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.002337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]