Abstract

Background

Some research seems to suggest that physical activity (PA) was beneficial for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Aim

This study examined the association between levels of PA and PTSD among individuals 15 years and above in South Africa.

Setting

Community-based survey sample representative of the national population in South Africa.

Methods

In all, 15 201 individuals (mean age 36.9 years) responded to the cross-sectional South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (SANHANES-1) in 2012.

Results

One in five (20.1%) of participants reported exposure to at least one traumatic event in a lifetime, and 2.1% were classified as having a PTSD, 7.9% fulfilled PTSD re-experiencing criteria, 3.0% PTSD avoidance criteria and 4.3% PTSD hyperarousal criteria. Almost half (48.1%) of respondents had low PA, 17.4% moderate PA and 34.5% high PA. In logistic regression analysis, adjusted for age, sex, population group, employment status, residence status, number of trauma types, problem drinking, current tobacco use, sleep problems and depressive symptoms, high PA was associated with PTSD (odds ratio [OR] = 1.75, confidence interval [CI] = 1.11–2.75), PTSD re-experiencing symptom criteria (OR = 1.43, CI = 1.09–1.86) and PTSD avoidance symptom criteria (OR = 1.74, CI = 1.18–2.59), but high PA was not associated with PTSD hyperarousal symptom criteria. In generalised structural equation modelling, total trauma events had a positive direct and indirect effect on PTSD mediated by high PA, and high PA had a positive indirect effect on PTSD, mediated by psychological distress and problem drinking.

Conclusion

After controlling for relevant covariates, high PA was associated with increased PTSD symptomatology.

Keywords: physical activity, post-traumatic stress symptoms, adolescents, adults, cross-sectional population survey, South Africa

Introduction

Globally, the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is significant and impacts morbidity and mortality.1,2 Compared with the general population, individuals with PTSD are more likely to have low physical activity (PA).3 In a systematic review from eight studies, four consistently found associations with lower PA in individuals with ‘PTSD symptoms of hyperarousal’.3 In additional studies, Whitworth et al.4 found that ‘strenuous intensity exercise’ directly decreased ‘avoidance/numbing and hyperarousal symptoms’, and total exercise directly decreased avoidance and numbing symptoms. LeardMann et al.5 found that engaging in PA, particularly high PA, decreased PTSD. All studies investigating levels of PA in relation to PTSD have been conducted in industrialised countries. In a previous review, Atwoli et al.6 note that ‘trauma and PTSD-risk factors may be distributed differently in lower-income countries compared with high-income countries’.

In several intervention studies, PA seems to be able to reduce symptoms of PTSD and depression among individuals with PTSD.2,7 Where limited access to traditional treatment modalities, such as psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, of PTSD is available like in low-resourced settings such as in South Africa, PA intervention as an adjunct to PTSD treatment could be relevant.2 Based on prior studies,3,8 it was hypothesised that greater moderate and high PA levels would be associated with reduced overall PTSD symptoms and the three PTSD symptom clusters. The study aimed to examine the association between PA levels and PTSD among individuals aged 15 years and above in South Africa.

Methods

Sample and procedure

Cross-sectional data of the South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (SANHANES-1) conducted in 2012 were analysed.9 Household members aged 15 years and above were ‘interviewed using a structured questionnaire on demographic and health variables’.9 The individual study survey response rate was 92.6%.9

Measures

Trauma event exposure. Participants were asked, ‘Have you ever experienced any of the following events?’ (14 events, e.g. ‘severe automobile accidents’ and ‘learned about the sudden, unexpected death of a family member or a close friend?’ – Yes or No).9

Post-traumatic stress disorder was measured with the ‘17-item Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS)’ that assesses ‘all primary DSM-IV symptoms of PTSD related to intrusion, avoidance and hyperarousal symptoms’.10 Participants had PTSD ‘if they score at least one re-experiencing, three avoidance/numbing and two hyperarousal phenomena at a frequency of at least twice in the previous week’10 (Cronbach’s alpha 0.94).

Physical activity was assessed with the validated ‘General Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ)’.11,12 ‘It assessed days and duration of PA at work, for transport, and during leisure time in a usual week’.12 Results were grouped into ‘low, moderate and high PA according to GPAQ guidelines’.12 Domain-specific PA (work, transportation and leisure time) were ‘classified into three groups, no (or low) activity, and low and high groups by the median metabolic equivalent (METs) of those having performed such activities’.13

Sleep problems was defined as ‘severe or extreme/can’t do’ having the ‘problem with sleeping, such as falling asleep, waking up frequently during the night, or waking up too early in the morning?’14

Depressive symptoms were defined as ‘severe or extreme/can’t do’ having the ‘problem with feeling sad, low or depressed’.9

Problem drinking was defined as scoring 3 or more in women and 4 or more in men on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption (AUDIT-C)15 (Cronbach’s alpha 0.89).

Demographic data included sex, age, population group, employment and residence status.

Current tobacco use included the use of ‘tobacco smoking and use of other tobacco products’.9

Psychological distress was defined as scores 20 or more on the 10-item Kessler scale16 that was validated in South Africa17 (Cronbach’s alpha 0.93).

Body pains were defined as ‘moderate, severe, extreme/can’t do’ having bodily discomfort.9

Data analysis

Data analyses were conducted in STATA software version 15.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA), taking into account the complex study design. Multivariable logistic regression was used to estimate the effects of PA (and its domains) on PTSD (and PTSD symptom criteria), adjusted for age, sex, population group, employment status, residence status, number of trauma types, problem drinking, current tobacco use, sleep problems and depressive symptoms. Covariates were included based on the literature review.3,4,5,8 Possible two-way interactions were tested, but no significant indirect effects of low, moderate and high PA on PTSD symptoms or any of the individual PTSD symptom clusters (ps > 0.05) were detected. To investigate pathways of associations between (1) total trauma events and (2) high PA and PTSD, we built generalised structural equation models (GSEMs). Models included variables, such as bodily pain, sleep quality, psychological distress, alcohol consumption and substance use, that were previously used in assessing indirect effects of PA on PTSD.4,18,19 Maximum likelihood function with observed information matrix standard errors was used to fit the models using Akaike Information Criteria (AIC). Data that were missing were not included in the analysis and no collinearity was found.

Ethical considerations

Informed written consent was obtained from participants. The study protocol was approved by the research ethics committee (REC) of the Human Sciences Research Council (REC 6/16/11/11).

Results

Sample characteristics

Participants included 15 201 individuals (of 16 780) 15–98 years (mean age 36.9, SD = 16.5) with complete measures of PTSD from South Africa. More than half of the participants were female (54.3%) and most were black African (77.8%), followed by white people (10.2%), mixed race (9.3%) and Indians or Asians (2.7%).

One in five respondents (20.1%) had exposure to at least one traumatic event in a lifetime based on DTS criteria. The specific major traumatic life events experienced included (1) ‘Sudden, unexpected death of a family member or a close friend’ (67.6%); (2) ‘Violent personal assault, serious accident, or serious injury experienced by a family member or a close friend’ (43.3%), (3) ‘Observed the serious injury or unnatural death of another person due to violent assault, accident, war, or disaster or unexpectedly witnessed a dead body or body parts’ (35.8%), (4) ‘Experienced severe automobile accidents’ (21.4%) and (5) ‘Being diagnosed with a life-threatening illness’ (16.7%). Regarding PTSD comorbidities, 2.9% of study participants reported ‘severe or extreme sleep problems’, 2.7% ‘severe or extreme depressive symptoms’, 20.5% engaged in problem drinking and 18.2% were currently using tobacco.

According to the three different PA levels, 48.1% of respondents were classified as having low PA, 17.4% moderate PA and 34.5% high PA. In all, 2.1% of study participants had a PTSD, 7.9% fulfilled PTSD re-experiencing criteria, 3.0% PTSD avoidance criteria and 4.3% PTSD hyperarousal criteria. Similar proportions of PTSD levels were found for the three PA domains (work, travel and leisure) (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics.

| Predictor variables (# missing cases) | Sample |

PTSD (n = 299) (%) | PTSD re-experiencing (n = 998) (%) | PTSD avoidance (n = 414) (%) | PTSD hyperarousal (n = 558) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | |||||

| All | 15 | 201 | 2.1 | 7.9 | 3.0 | 4.3 |

| Age (# 10) | ||||||

| 15–24 | 4296 | 27.7 | 2.0 | 6.8 | 2.6 | 3.7 |

| 25–44 | 5482 | 43.01 | 2.2 | 8.1 | 3.2 | 4.6 |

| 45–64 | 4015 | 21.9 | 2.3 | 8.6 | 3.2 | 4.5 |

| 65 or more | 1398 | 7.3 | 2.1 | 8.6 | 3.3 | 4.5 |

| Sex (# 92) | ||||||

| Men | 6292 | 45.7 | 2.0 | 8.6 | 3.3 | 4.9 |

| Women | 8817 | 54.3 | 2.3 | 7.0 | 2.8 | 3.7 |

| Population group (# 178) | ||||||

| Black African | 10 045 | 77.8 | 2.5 | 8.5 | 3.5 | 4.7 |

| White people | 717 | 10.2 | 0.7 | 6.7 | 0.9 | 3.3 |

| Mixed race | 2983 | 9.3 | 0.9 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 1.7 |

| Asian or Indian | 1278 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 8.9 | 2.7 | 5.8 |

| Employment status (# 540) | ||||||

| No | 9631 | 63.5 | 2.5 | 8.2 | 3.5 | 4.6 |

| Yes | 5030 | 36.5 | 1.6 | 7.4 | 2.2 | 3.9 |

| Residence (# 0) | ||||||

| Rural | 5079 | 36.4 | 1.9 | 7.3 | 2.6 | 3.4 |

| Urban | 1022 | 63.6 | 2.3 | 8.2 | 3.3 | 4.9 |

| Number of trauma types (# 364) | ||||||

| 0 | 12 186 | 79.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 1 | 978 | 7.4 | 6.1 | 28.9 | 8.4 | 11.7 |

| 2 | 695 | 5.0 | 10.1 | 35.2 | 14.9 | 20.1 |

| 3 or more | 978 | 7.7 | 13.3 | 46.1 | 18.5 | 28.5 |

| Sleep problems (# 103) | 443 | 2.9 | 10.5 | 25.6 | 14.3 | 19.6 |

| Depressive symptoms (# 105) | 394 | 2.7 | 13.9 | 27.8 | 19.3 | 20.0 |

| Problem drinking (# 311) | 2816 | 20.5 | 3.5 | 10.0 | 4.6 | 6.1 |

| Current tobacco use (# 344) | 2990 | 18.2 | 3.4 | 10.2 | 4.5 | 6.2 |

| Physical activity (# 595) | ||||||

| Low | 7278 | 48.1 | 1.7 | 6.7 | 2.4 | 3.9 |

| Moderate | 2504 | 17.4 | 1.8 | 7.6 | 2.9 | 3.7 |

| High | 4724 | 34.5 | 3.0 | 9.6 | 4.1 | 5.3 |

| Work physical activity (# 239) | ||||||

| Low (0 METS) | 9770 | 62.8 | 1.6 | 6.5 | 2.3 | 3.5 |

| Moderate (1–4789 METS) | 2664 | 18.3 | 3.2 | 10.3 | 4.6 | 5.4 |

| High (4800 or more METS) | 2557 | 18.9 | 3.1 | 10.6 | 4.2 | 6.0 |

| Travel physical activity (# 239) | ||||||

| Low (0 METS) | 6812 | 42.9 | 1.5 | 5.9 | 2.0 | 3.5 |

| Moderate (1–799 METS) | 3937 | 26.7 | 3.3 | 10.9 | 4.5 | 5.9 |

| High (800 or more METS) | 4436 | 30.4 | 2.1 | 8.2 | 3.2 | 4.2 |

| Leisure physical activity (# 362) | ||||||

| Low (0 METS) | 12 395 | 79.3 | 2.0 | 7.1 | 2.8 | 3.9 |

| Moderate (1–2039 METS) | 1235 | 10.6 | 2.3 | 11.5 | 3.5 | 6.3 |

| High (2040 or more METS) | 1333 | 10.1 | 2.8 | 10.1 | 4.5 | 5.5 |

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; METS, metabolic equivalents.

Associations between physical activity levels and post-traumatic stress disorder

In logistic regression analysis, adjusted for age, sex, population group, employment status, residence status, number of trauma types, problem drinking, current tobacco use, sleep problems and depressive symptoms, high PA was associated with PTSD (odds ratio [OR] = 1.75, confidence interval [CI] = 1.11–2.75), PTSD re-experiencing symptom criteria (OR = 1.43, CI = 1.09–1.86) and PTSD avoidance symptom criteria (OR = 1.74, CI = 1.18–2.59), but high PA was not associated with PTSD hyperarousal symptom criteria (see Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Associations between physical activity levels and PTSD (N = 13469).

| Variable | OR | (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion variable: PTSD | |||

| Step 1 | |||

| Low physical activity | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate physical activity | 1.03 | 0.66–1.62 | 0.890 |

| High physical activity | 1.75 | 1.24–2.48 | 0.002 |

| Step 2† | |||

| Low physical activity | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate physical activity | 1.43 | 0.88–2.34 | 0.148 |

| High physical activity | 1.85 | 1.18–2.89 | 0.008 |

| Criterion variable: PTSD re-experiencing symptoms | |||

| Step 1 | |||

| Low physical activity | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate physical activity | 1.14 | 0.84–1.54 | 0.402 |

| High physical activity | 1.48 | 1.17–1.86 | < 0.001 |

| Step 2† | |||

| Low physical activity | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate physical activity | 1.34 | 0.96–1.85 | 0.082 |

| High physical activity | 1.46 | 1.11–1.90 | 0.006 |

| Criterion variable: PTSD avoidance and numbing symptoms | |||

| Step 1 | |||

| Low physical activity | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate physical activity | 1.18 | 0.85–1.63 | 0.327 |

| High physical activity | 1.71 | 1.28–2.29 | < 0.001 |

| Step 2† | |||

| Low physical activity | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate physical activity | 1.60 | 1.03–2.48 | 0.036 |

| High physical activity | 1.90 | 1.28–2.82 | < 0.001 |

| Criterion variable: PTSD hyperarousal symptoms | |||

| Step 1 | |||

| Low physical activity | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate physical activity | 0.94 | 0.67–1.31 | 0.695 |

| High physical activity | 1.36 | 1.02–1.82 | 0.037 |

| Step 2† | |||

| Low physical activity | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate physical activity | 1.17 | 0.78–1.76 | 0.440 |

| High physical activity | 1.46 | 0.99–2.15 | 0.054 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

, Adjusted for age, gender, population group, residence status, employment status, number of trauma types, hazardous or harmful alcohol use, current tobacco use, sleep problems and depressive symptoms.

Associations between domains of physical activity levels and post-traumatic stress disorder

In logistic regression analysis, adjusted for age, sex, population group, employment status, residence status, number of trauma types, problem drinking, current tobacco use, sleep problems and depressive symptoms, high work-related PA and moderate travel-related PA were associated with PTSD, while leisure-related PA was not associated with PTSD. High work- and leisure-related PA was positively associated with all three PTSD symptom criteria, while moderate and/or high travel-related PA was positively associated with all three PTSD symptom criteria (see Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Associations between domains of physical activity levels and PTSD (N = 13469).

| Variable | AOR | (95% CI)† | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion variable: PTSD | |||

| Work physical activity | |||

| Low (0 METS) | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate (1–4789 METS) | 1.91 | 1.11-3.31 | 0.021 |

| High (4800 or more METS) | 1.83 | 1.08–3.11 | 0.026 |

| Travel physical activity | |||

| Low (0 METS) | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate (1–799 METS) | 2.70 | 1.56–4.70 | < 0.001 |

| High (800 or more METS) | 1.44 | 0.77–2.71 | 0.254 |

| Leisure physical activity | |||

| Low (0 METS) | 1 | Reference | |

| Moderate (1–2039 METS) | 0.82 | 0.38–1.76 | 0.607 |

| High (2040 or more METS) | 1.35 | 0.76–2.41 | 0.311 |

| Criterion variable: PTSD re-experiencing symptoms | |||

| Work physical activity | |||

| Low (0 METS) | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate (1–4789 METS) | 1.44 | 1.09–1.90 | 0.010 |

| High (4800 or more METS) | 1.44 | 1.06–1.95 | 0.020 |

| Travel physical activity | |||

| Low (0 METS) | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate (1–799 METS) | 2.40 | 1.71–3.36 | < 0.001 |

| High (800 or more METS) | 1.52 | 1.08–2.15 | 0.017 |

| Leisure physical activity | |||

| Low (0 METS) | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate (1–2039 METS) | 1.52 | 0.99–2.34 | 0.055 |

| High (2040 or more METS) | 1.46 | 1.02–2.08 | 0.039 |

| Criterion variable: PTSD avoidance and numbing symptoms | |||

| Work physical activity | |||

| Low (0 METS) | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate (1–4789 METS) | 2.07 | 1.39–3.08 | < 0.001 |

| High (4800 or more METS) | 1.83 | 1.21–2.77 | 0.004 |

| Travel physical activity | |||

| Low (0 METS) | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate (1–799 METS) | 2.99 | 1.82–4.91 | < 0.001 |

| High (800 or more METS) | 1.65 | 0.95–2.85 | 0.073 |

| Leisure physical activity | |||

| Low (0 METS) | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate (1–2039 METS) | 1.06 | 0.65–1.75 | 0.808 |

| High (2040 or more METS) | 1.84 | 1.12–3.03 | 0.017 |

| Criterion variable: PTSD hyperarousal symptoms | |||

| Work physical activity | |||

| Low (0 METS) | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate (1–4789 METS) | 1.51 | 1.04–2.19 | 0.031 |

| High (4800 or more METS) | 1.68 | 1.08. 2.60 | 0.022 |

| Travel physical activity | |||

| Low (0 METS) | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate (1–799 METS) | 2.10 | 1.33–3.32 | 0.002 |

| High (800 or more METS) | 1.30 | 0.83–2.04 | 0.258 |

| Leisure physical activity | |||

| Low (0 METS) | 1 | Reference | - |

| Moderate (1–2039 METS) | 1.31 | 0.74–2.34 | 0.353 |

| High (2040 or more METS) | 1.59 | - | 0.037 |

AOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder; METS, metabolic equivalents.

, Adjusted for age, gender, population group, residence status, employment status, number of trauma types, hazardous or harmful alcohol use, current tobacco use, sleep problems and depressive symptoms.

Structural equation model analysis

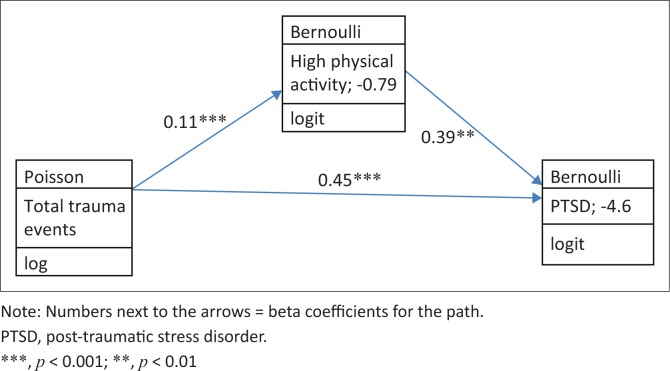

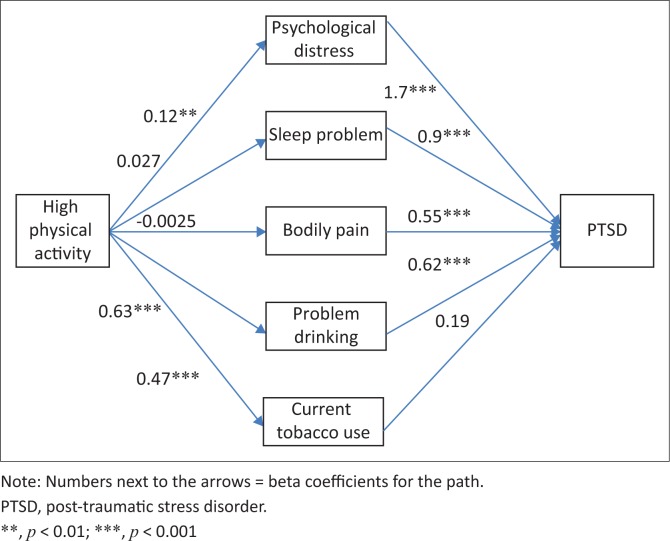

Total trauma events had a positive direct and indirect effect on PTSD mediated by high PA (see Figure 1). High PA had a positive indirect effect on PTSD, mediated by psychological distress and problem drinking (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Generalised structural equation model legend: Total trauma events – high physical activity – post-traumatic stress disorder.

FIGURE 2.

Generalised structural equation model legend: High physical activity – psychological distress (Kessler-10) – sleep problem – bodily pain – problem drinking – current tobacco use – post-traumatic stress disorder.

Discussion

This is one of the first investigations in a middle-income country, South Africa, to assess the relationship between PA and PTSD. The current conditional prevalence of PTSD after trauma exposure found in this study was 2.1%, which seems a little lower than in the previous South African Stress and Health Study (3.5%).20 While in this study 20.1% reported at least experiencing one lifetime trauma, the previous study reported a much higher exposure of 73.8%.20 Differences may stem from the more comprehensive trauma exposure measure of the South African Stress and Health Study that used 27 different types of trauma exposure,20 while this study only had 14 different types of traumatic events.

This investigation found an association between high PA, after controlling for significant covariates, and PTSD total, PTSD re-experiencing and PTSD avoidance symptom criteria, but not with PTSD hyperarousal symptom criteria. These findings seem to be contrary to what previous studies found, namely associations between low PA participation and increased PTSD symptoms of hyperarousal,3 and high PA and decreased PTSD symptoms5 and decreased avoidance and numbing symptoms.4 One possible explanation for this difference could be that trauma and PTSD-risk factors as well as ameliorating factors such as PA may be distributed differently in low-income countries, such as South Africa, compared with high-income countries where the previous studies originated. Several studies2,4,8 found the beneficial effect of intensive exercise behaviour on PTSD and PTSD symptoms. However, when we analysed domain-specific PA, similar results were found that: in all three PA domains (work, travel and leisure-related PA) a positive association was found with PTSD and/or PTSD symptoms.

Although some other studies found an indirect effect of PA, for example via smoking18 and poor sleep quality,19 this study found positive indirect effects of PA on PTSD symptoms, mediated by psychological distress and problem drinking. Previous research4,21,22 has found that PA has beneficial effects on psychological distress and alcohol use, which was not supported by the findings of this study. However, several other studies23,24 found a positive relationship between PA and alcohol use. Furthermore, this study did not confirm previous findings,18,19,25 suggesting beneficial effects of PA on PTSD through tobacco use, sleep quality and bodily pain. Clearly, more longitudinal studies are needed to establish the direct and indirect links between PA activity and PTSD and PTSD symptoms.

Study limitations

Because the investigation was based on cross-sectional data, no causative inferences can be made. The assessment of our data was based on self-report, including PA. This may have led to an overestimation of PA levels.26

Conclusion

This investigation found in a national community-based sample in South Africa that, after controlling for relevant confounders, high PA was associated with overall PTSD symptoms, PTSD re-experiencing symptom criteria and PTSD avoidance symptom criteria. Future investigations in low- and middle-income countries are needed to replicate these results.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Human Sciences Research Council for the South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (SANHANES-1) 2011–12: Adult Questionnaire – All provinces [Data set]. SANHANES 2011–12 Adult Questionnaire. Version 1.0. Pretoria South Africa: Human Sciences Research Council [producer] 2012, Human Sciences Research Council [distributor] 2017. http://doi.org/10.14749/1494330158.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors’ contributions

K.P. and S.P. designed and conducted the analyses and wrote the draft article and all authors read and approved the final article.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data of the South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (SANHANES-1) 2011–12 are available at http://datacuration.hsrc.ac.za.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the authors.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Peltzer K, Pengpid S. High physical activity is associated with post-traumatic stress disorder among individuals aged 15 years and older in South Africa. S Afr J Psychiat. 2019;25(0), a1329. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v25i0.1329

References

- 1.Gradus JL. Prevalence and prognosis of stress disorders: A review of the epidemiologic literature. Clin Epidemiol. 2017;9:251–260. 10.2147/CLEP.S106250.eCollection2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oppizzi LM, Umberger R. The effect of physical activity on PTSD. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2018;39(2):179–187. 10.1080/01612840.2017.1391903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vancampfort D, Richards J, Stubbs B, et al. Physical activity in people with posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review of correlates. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13(8):910–918. 10.1123/jpah.2015-0436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitworth JW, Craft LL, Dunsiger SI, Ciccolo JT. Direct and indirect effects of exercise on posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: A longitudinal study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;49:56–62. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LeardMann CA, Kelton ML, Smith B, et al. Prospectively assessed posttraumatic stress disorder and associated physical activity. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(3):371–383. 10.1177/003335491112600311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atwoli L, Stein DJ, Koenen KC, McLaughlin KA. Epidemiology of posttraumatic stress disorder: Prevalence, correlates and consequences. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28(4):307–311. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenbaum S, Vancampfort D, Steel Z, Newby J, Ward PB, Stubbs B. Physical activity in the treatment of Post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2015;230(2):130–136. 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harte CB, Vujanovic AA, Potter CM. Association between exercise and posttraumatic stress symptoms among trauma-exposed adults. Eval Health Prof. 2015;38(1):42–52. 10.1177/0163278713494774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shisana O, Labadarios D, Rehle T, et al. South African national health and nutrition examination survey (SANHANES-1). Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson JR, Book SW, Colket JT, et al. Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. 1997;27:153–160. 10.1017/s0033291796004229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong T, Bull F. Development of the World Health Organization Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ). J Pub Health. 2006;14:66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization (WHO) Global physical activity surveillance [homepage on the Internet]. 2017. [cited 2017 Dec 02]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/steps/GPAQ/en/index.html.

- 13.Zheng B, Yu C, Lin L, et al. Associations of domain-specific physical activities with insomnia symptoms among 0.5 million Chinese adults. J Sleep Res. 2017;26(3), 330–337. 10.1111/jsr.12507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stranges S, Tigbe W, Gómez-Olivé FX, Thorogood M, Kandala NB. Sleep problems: An emerging global epidemic? Findings from the INDEPTH WHO-SAGE study among more than 40,000 older adults from 8 countries across Africa and Asia. Sleep. 2012;35:1173–1181. 10.5665/sleep.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The audit alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C), an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–976. 10.1017/s0033291702006074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersen LS, Grimsrud A, Myer L, Williams DR, Stein DJ, Seedat S. The psychometric properties of the K10 and K6 scales in screening for mood and anxiety disorders in the South African Stress and Health study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2011;20(4):215–223. 10.1002/mpr.351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vujanovic AA, Farris SG, Harte CB, Smits JA, Zvolensky MJ. Smoking status and exercise in relation to PTSD Symptoms: A test among trauma-exposed adults. Ment Health Phys Act. 2013;6(2). 10.1016/j.mhpa.2012.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talbot LS, Neylan TC, Metzler TJ, Cohen BE. The mediating effect of sleep quality on the relationship between PTSD and physical activity. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(7):795–801. 10.5664/jcsm.3878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atwoli L, Stein DJ, Williams DR, et al. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in South Africa: Analysis from the South African Stress and Health Study. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:182 10.1186/1471-244X-13-182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chu AHY, Van Dam RM, Biddle SJH, Tan CS, Koh D, Müller-Riemenschneider F. Self-reported domain-specific and accelerometer-based physical activity and sedentary behaviour in relation to psychological distress among an urban Asian population. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15(1):36 10.1186/s12966-018-0669-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Leisure-time sedentary behavior is associated with psychological distress and substance use among school-going adolescents in five Southeast Asian Countries: A cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(12). pii: E2091 10.3390/ijerph16122091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dodge T, Clarke P, Dwan R. The relationship between physical activity and alcohol use among adults in the United States. Am J Health Promot. 2017;31(2):97–108. 10.1177/0890117116664710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werneck AO, Oyeyemi AL, Szwarcwald CL, Silva DR. Association between physical activity and alcohol consumption: Sociodemographic and behavioral patterns in Brazilian adults. J Public Health (Oxf). 2018. 10.1093/pubmed/fdy202 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, Kuijpers T, et al. A systematic review on the effectiveness of physical and rehabilitation interventions for chronic non-specific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(1):19–39. 10.1007/s00586-010-1518-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hagstromer M, Ainsworth BE, Oja P, Sjostrom M. Comparison of a subjective and an objective measure of physical activity in a population sample. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(4):541–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data of the South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (SANHANES-1) 2011–12 are available at http://datacuration.hsrc.ac.za.