Abstract

We report the preparation of α‐chlorosilyl‐ and acyl‐substituted digermenes. Unlike the corresponding transient disilenes, these species with a Ge=Ge double bond show an unexpectedly low tendency for cyclization, but in turn are prone to thermal Ge=Ge bond cleavage. Triphenylsilyldigermene has been isolated as a crystalline model compound, and is the first fully characterized example of a neutral digermene with an A2GeGeAB substitution pattern. Spectroscopic and computational evidence prove the constitution of 1‐adamantoyldigermene as a first persistent species with a heavy double bond conjugated with a carbonyl moiety.

Keywords: cycloaddition, digermenes, double bonds, germanium, isomerization

Break the cycle! The synthesis and spectroscopic characterization of α‐chlorosilyl‐ and acyldigermenes are reported (see graphic). Unlike their lighter silicon congeners, these digermenes do not rearrange into cyclic systems. This has allowed, for example, the first characterization of a species with a CO‐functionalized heavier double bond. Ultimately, these compounds thermally dissociate to form germylene fragments.

Introduction

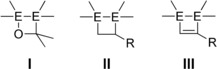

The discovery of the first alkene analogue in 1976, Lappert's distannene,1 led to a rapid growth in interest in the chemistry of multiple bonds between heavier Group 14 elements. This resulted in the isolation of stable doubly and eventually triply bonded species of both silicon and germanium,2 which have since been proven to be useful synthons in preparative chemistry. For example, Si‐ and Ge‐based ring systems are accessible by their cycloaddition to unsaturated organic substrates such as ketones (I),3 alkenes (II),4 and acetylenes (III)3e, 5 (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Small ring systems (E=Si, Ge) derived from [2+2] cycloadditions of disilenes or digermenes to ketones (I), alkenes (II), and acetylenes (III).

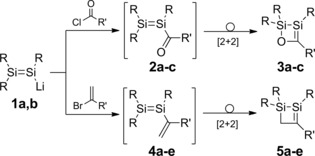

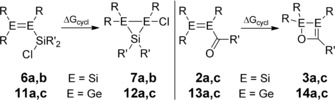

The synthetic application of disilenes gained further momentum with the advent of functionalized derivatives, most notably disilenides as analogues of vinyllithium.6 The anionic, nucleophilic silicon center in these species enables targeted peripheral functionalization of the uncompromised Si=Si moiety, as documented by various examples.7 In some cases, however, these functional disilenes rearrange to cyclic isomers, a process that is thermodynamically driven by replacement of the weak π bond by stronger bonds (Scheme 2). In particular, disilenides 1 a,b undergo quantitative reactions with carboxylic acid chlorides to afford cyclic Brook‐type silenes 3 a–c.8 The plausible intermediates, acyl disilenes 2 a–c, could not be detected by NMR spectroscopy, even at low temperature. Documented examples of acyl‐substituted species with double bonds between heavier main group elements are still unknown, both experimentally and theoretically. Likewise, disilenides 1 a,b react with various vinyl bromides to afford 1,2‐disilacyclobut‐2‐enes 5 a–e, without spectroscopic evidence for the putative intermediates, vinyldisilenes 4 a–e.9 The electronic structure of the latter has been investigated theoretically for the parent species.10 Experimentally, however, 1,2‐disilabutadienes are as yet unknown, except for the recently reported 1,2,3‐trisilacyclopentadienes, in which cyclization is hindered by incorporation of the butadiene motif into the five‐membered ring.11

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of cyclic silenes 3 a–c and 5 a–e (1 a: R=Tip=2,4,6‐iPr3C6H2; 1 b: R=SiMetBu2; 2 a, 3 a: R=Tip, R′=tBu; 2 b, 3 b: R=Tip, R′=1‐adamantyl; 2 c, 3 c: R=SiMetBu2, R′=1‐adamantyl; 4 a, 5 a: R=Tip, R′=Ph; 4 b, 5 b: R=Tip, R′=SiMe3; 4 c, 5 c: R=SiMetBu2, R′=H; 4 d, 5 d: R= SiMetBu2, R′=Ph; 4 e, 5 e: R=SiMetBu2, R′=SiMe3).8, 9

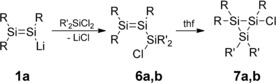

Conversely, α‐chlorosilyldisilenes 6 a,b, prepared from the reaction of 1 a with dichlorosilanes, have been isolated, although they readily rearrange to cyclotrisilanes 7 a,b (Scheme 3).12 Specifically, the dimethyl‐substituted trisilaallyl chloride 6 a spontaneously cyclizes to cyclotrisilane 7 a, even at room temperature in the absence of a donor solvent, whereas the corresponding diphenyl derivative 6 b is stable in a hydrocarbon solvent for several weeks and needs elevated temperature or the addition of THF to promote isomerization to 7 b.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of α‐chlorosilyldisilenes 6 a,b and cyclotrisilanes 7 a,b (R=Tip; 6 a, 7 a: R′=Me; 6 b, 7 b: R′=Ph).12

Compared to the versatile syntheses, reactions, and applications of disilenes, the chemistry of digermenes is still in its infancy. We recently reported the isolation of the first lithium digermenide 8 as well as proof‐of‐principle experiments for its reactivity as a nucleophile in salt metathesis reactions with monochlorosilanes (Scheme 4).13 Single‐crystal X‐ray diffraction data for the resulting unsymmetrically substituted digermenes 9 a,b could only be obtained for a partially hydrolyzed sample of 9 b, which were of limited value in terms of the determination of pertinent bonding parameters.

Scheme 4.

Previously reported synthesis of unsymmetrically substituted digermenes 9 a,b (R=Tip=2,4,6‐iPr3C6H2; 9 a: SiR′3=SiMe3; 9 b: SiR′3=SiMe2Ph).13

Considering the vast synthetic possibilities offered by the availability of disilenides and the lack of simple synthetic protocols for digermasilacyclopropanes14 and cyclic Brook‐type germenes, we investigated the reactivity of 8 towards dichlorosilanes and acyl chlorides in order to prepare the digerma analogues of previously reported silacycles 3 and 7.

Results and Discussion

Triphenylsilyldigermene 10

Reaction of Ph3SiCl with digermenide 8 in toluene at room temperature yielded triphenylsilyldigermene 10 of NMR spectroscopic purity. Crystallization from a concentrated solution in hexane afforded single crystals of 10 as yellow plates in 52 % yield (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of triphenylsilyl digermene 10 (R=Tip=2,4,6‐iPr3C6H2).

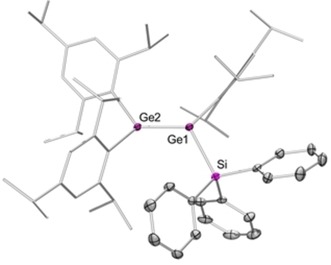

The 29Si NMR spectrum of 10 features one singlet at δ=1.89 ppm, in the expected range for a tetracoordinate silicon center, which compares well to the signals observed for 9 a (δ=1.87 ppm) and 9 b (δ=0.25 ppm).13 The longest wavelength absorption in the UV/Vis spectrum is located in the typical region for heavier alkene homologues at λ max=426 nm (ϵ=20 845 L mol−1 cm−1) and is thus slightly blue‐shifted compared to the value reported for digermenide 8 (λ max=435 nm).13 Single‐crystal X‐ray diffraction analysis confirmed the constitution of 10 as a silyl‐substituted digermene (Figure 1). The trans‐bent angles θ (defined as the angle between the R‐E‐R′ plane normal and the E‐E bond vector) in 10 [θ(Ge1)=23.7°; θ(Ge2)=21.3°] are substantially larger than those in 8 [θ(GeTipLi)=12.8°, θ(GeTip2)=7.1°] or the symmetrically substituted Tip2Ge=GeTip2 [θ(GeTip2)=12°]. In contrast, the twist angle τ (defined as the angle between the R‐E‐R′ plane normals) of 10 (τ=13.6°) is similar to that in Tip2Ge=GeTip2 (τ=14°) and thus smaller than that in 8 (τ=19.9°).13, 15, 16 In agreement with the increased trans bending, the Ge−Ge distance of 2.3279(4) Å is elongated compared to those in both 8 (2.284 Å) and Tip2Ge=GeTip2 (2.213 Å).13, 15, 16 The Ge1−Si bond of 2.3984(8) Å is slightly shorter than those in persilyl‐substituted digermenes (iPr2MeSi)2Ge=Ge(SiMeiPr2)2 (2.400 Å) and (iPr3Si)2Ge=Ge(SiiPr3)2 (2.427 Å).17

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of triphenylsilyl digermene 10 in the solid state (hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity; thermal ellipsoids drawn at 50 % probability). Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°]: Ge1−Ge2 2.3279(4), Ge1−Si 2.3984(8); Ge2−Ge1−Si 119.09(8), Σ°(Ge1) 346.53, Σ°(Ge2) 345.24, θ(Ge1) 23.7, θ(Ge2) 21.3, τ 13.6. Σ°(E) refers to the sum of angles around atom E.

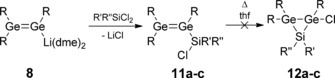

Reaction of digermenide 8 with dichlorosilanes

Treatment of 8 with 1.5 equivalents of Me2SiCl2 at −78 °C in toluene resulted in an immediate color change to bright‐orange. The 1H NMR spectrum of the reaction mixture showed full conversion to a single product, which was identified as silyl digermene 11 a based on the following spectroscopic observations.

Three sharp singlets in the aryl region at δ=7.12, 7.09, and 7.01 ppm suggest the presence of three chemically inequivalent Tip groups that rotate rapidly on the NMR time scale and are therefore relatively unhindered. The singlet at δ=0.58 ppm with a relative intensity corresponding to six H atoms is assigned to the Si‐bonded methyl groups. The identical chemical environment of the two methyl groups virtually excludes a three‐membered Si2Ge ring as the presence of the asymmetric Ge center in the hypothetical heavy cyclopropane 12 a would cause diastereotopic splitting of the corresponding signals. Comparison with the NMR data of silyl disilene 6 a and its isomeric cyclotrisilane 7 a underpins this interpretation (Table 1).11

Table 1.

NMR spectroscopic data for α‐chlorosilyldigermenes 11 a–c in comparison with those of α‐chlorosilyldisilenes 6 a,b, cyclotrisilanes 7 a,b, and silyldigermenes 9 a,b and 10.

|

|

δ 29Si [ppm] |

δ 1HTip‐H [ppm] |

δ 1Hortho‐iPr‐CH [ppm] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

11 a |

31.5 |

7.12, 7.09, 7.02 |

3.89, 3.75, 3.59 |

|

11 b |

23.7 |

7.12, 7.03, 7.03 |

3.92, 3.76, 3.62 |

|

11 c |

15.2 |

masked by Ph signals |

3.58, 3.54, 3.34 |

|

6 a |

26.2 |

7.09, 7.06, 6.99 |

4.29, 4.00, 3.78 |

|

6 b |

11.8 |

masked by Ph signals |

4.15, 3.97, 3.74 |

|

7 a |

−35.4 |

7.20, 7.18, 7.15, 7.02, 6.95 |

4.21, 4.09, 3.74, 3.61, 3.43 |

|

7 b |

−54.8 |

masked by Ph signals |

4.04, 3.96, 3.89, 3.55 |

|

9 a |

1.87 |

7.11, 7.10, 7.02 |

3.84, 3.83, 3.65 |

|

9 b |

0.25 |

7.09, 7.06, 7.05 |

3.85, 3.82, 3.67 |

|

10 |

1.89 |

7.06, 7.01, 6.95 |

3.86, 3.76, 3.72 |

Consistent evidence is provided by the 13C NMR spectrum of 11 a, with twelve signals between 153.1 and 122.0 ppm that satisfyingly match, in number and chemical shifts, the corresponding signals of silyl disilene 6 a, while being in stark contrast to the eighteen signals in this range for cyclotrisilane 7 a.12 The 29Si NMR signal at δ=31.5 ppm is typical of a terminal silyl group (6 a: δ=26.2 ppm, 9 a: δ=1.87 ppm, 9 b: δ=0.25 ppm), unambiguously excluding the presence of an endocyclic Si atom (7 a: δ=−35.4 ppm).12, 13 The slightly lower field 29Si NMR shift of 11 a compared to 6 a can be rationalized in terms of the higher electronegativity of germanium compared to silicon. The UV/Vis spectrum of a freshly prepared and filtered solution shows the longest‐wavelength absorption at λ max=435 nm (ϵ=11 110 L mol−1 cm−1), close to the values for silyldisilenes and digermenes (7 b: 427 nm,12 10: 426 nm), strongly supporting the presence of an uncompromised Ge=Ge moiety. Based on the accumulated spectroscopic evidence, we are confident in assigning the connectivity of α‐chlorosilyldigermene 11 a to the main product of the reaction of digermenide 8 with Me2SiCl2 (Scheme 6). Despite various attempts at crystallization from concentrated solutions in hexane, pentane, benzene, toluene, mesitylene, fluorobenzene, or THF, single crystals of 11 a could not be obtained.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of α‐chlorosilyl digermenes 11 a–c (R=Tip=2,4,6‐iPr3C6H2; 11 a, 12 a: R′=R′′=Me; 11 b, 12 b: R′=Me, R′′=Ph; 11 c, 12 c: R′=R′′=Ph).

In an analogous manner to Me2SiCl2, the sterically more demanding dichlorosilanes MePhSiCl2 and Ph2SiCl2 reacted with digermenide 8 at −78 °C in toluene to afford the α‐chlorosilyldigermenes 11 b and 11 c, which were characterized by multinuclear NMR spectroscopy, but again eluded crystallization. In principle, the same arguments for structure identification hold as in the case of 11 a (Table 1): the 29Si NMR signals of 11 b,c (11 b: δ=23.7 ppm; 11 c: δ=15.2 ppm) are detected at significantly lower field than expected for three‐membered rings (7 a: δ=−35.4 ppm; 7 b: δ=−54.8 ppm). Three chemically distinct Tip groups give rise to the minimum number of signals in the 1H and 13C NMR spectra, indicating free rotation about the Ge−C bond. Unfortunately, redox processes become competitive during the synthesis of 11 b and 11 c, resulting in increasing amounts of the intensely green 1,3‐tetragermabutadiene Tip2Ge=Ge(Tip)−(Tip)Ge=GeTip2 18 as a side product (11 b: <0.5 %; 11 c: 2 %, as determined by 1H NMR). Presumably, the increasing number of electron‐withdrawing phenyl groups renders the dichlorosilane reagents more prone to reduction by digermenide 8, which is oxidatively coupled to the tetragermabutadiene in the process.

As reported previously, isomerization of the related disilenes 6 a,b to the corresponding cyclotrisilanes is induced by heating or the addition of THF as a donor solvent. At higher temperatures or upon addition of THF, however, all silyldigermenes eventually decompose to product mixtures dominated by the homoleptic Tip2Ge=GeTip2 15 as the only identifiable product. Digermenes in general are known to be readily cleaved into their constituent germylene fragments. Thermally induced dissociation of the Ge=Ge double bond of 10 and 11 a–c and subsequent dimerization of the resulting Tip2Ge: fragments plausibly explains the formation of Tip4Ge2. The concomitantly formed Tip(R2ClSi)Ge: fragments seem to be highly unstable and presumably decompose via various pathways to a variety of unknown products.

Accordingly, α‐chlorosilyldigermenes 11 a–c are much less prone to cyclization to heavy cyclopropanes 12 a–c compared to the disilene congeners 6 a,b, but rather dissociate into their germylene fragments under thermal treatment or in the presence of n‐donating solvents.

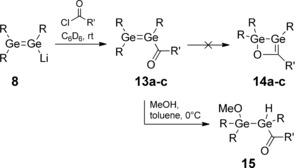

Reactions of digermenide 8 with acyl chlorides

In the light of the above observations, we anticipated that the use of acyl chlorides as substrates for the reaction with 8 might allow the isolation of the first stable compounds with acyl‐substituted heavier double bonds. Upon addition of 1 equivalent of either pivaloyl chloride, 2,2‐dimethylbutyryl chloride, or 1‐adamantoyl chloride to digermenide 8 at room temperature in C6D6, the reaction mixture instantly turned dark‐red and precipitation of a white solid was observed (Scheme 7).

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of acyl digermenes 13 a–c and trapping with methanol to afford 15 (R=Tip=2,4,6‐iPr3C6H2; 13 a, 14 a: R′=tBu; 13 b, 14 b: R′=2‐methylbutan‐2‐yl; 13 c, 14 c, 15: R′=1‐adamantyl).

The 1H NMR spectra of the crude products after five minutes indicated very clean conversion to single products in all cases. During the reported reactions of disilenide 1 with carboxylic acid chlorides, an initially occurring red color8 might be attributed to transient yet undetected acyl disilenes. In the present case, the red color persisted at room temperature for up to several hours (13 a,b) or days (13 c). The 1H and 13C NMR signals of 13 a–c (see the Supporting Information) are of limited diagnostic value in distinguishing them from hypothetical cyclic germenes 14 a–c as the cyclic Brook silenes 3 a,b have been reported to show rapid inversion at the Si=C silicon atom at room temperature, leading to apparent C s symmetry in solution and hence a lower number of signals for the Tip substituents than might otherwise be expected.8

Monitoring samples of 13 a–c by 1H NMR revealed that conversion to homoleptic Tip2Ge=GeTip2 and various unidentified side products takes place even at room temperature, in analogy to what was observed for α‐chlorosilyldigermenes 11 a–c. Whereas the reaction mixtures obtained from digermenide 8 and pivaloyl chloride or 2,2‐dimethylbutyryl chloride largely decomposed in the course of one night, the 1‐adamantoyl‐substituted 13 c persisted to about 95 % even after 18 h in reaction mixtures at the original concentration. The decomposition rate, however, increased at higher concentrations, which prevented the removal of 1,2‐dimethoxyethane (liberated from 8) from the reaction mixture as well as crystallization attempts from concentrated solutions. The similarity to the decomposition behavior of digermenes 11 a–c, however, suggests that the reaction products may indeed be the unprecedented acyldigermenes 13 a–c. Due to its superior stability in solution, we limit the following discussion to the 1‐adamantoyl derivative 13 c (see the Supporting Information for spectra of 13 a,b).

The 13C NMR spectrum of 13 c at 300 K features two signals at δ=232.4 and 238.7 ppm, in the typical range for carbonyl C atoms, which we attribute to the s‐cis and s‐trans isomers of the Ge=Ge−C=O system. Theoretical calculations on their relative thermodynamic stabilities at the M06‐2X(D3)/def2‐TZVPP//BP86(D3)def2‐SVP level of theory predicted the s‐cis isomer (dihedral angle φ=51.64°) to be 10.9 kcal mol−1 more stable than the s‐trans form (φ=−149.13°). The IR band at 1649 cm−1 validates the presence of a C=O bond attached to germanium in 13 c, and is in acceptable agreement with the calculated value of 1690 cm−1 for the s‐cis isomer. A shift of around 70 cm−1 to lower wavenumbers compared to fully organic ketones is well known for acylsilanes and ‐germanes, and has been rationalized in terms of lowering of the C−O bond order due to the σ donating character of the tetryl moiety.19 In the UV/Vis spectrum of 13 c, two bands at λ max=476 nm and λ=386 nm further support the proposed open‐chain structure: the longest‐wavelength absorption maximum falls within the typical absorption range of digermenes and shows a substantial bathochromic shift compared to the bands observed for 8 (λ max=435 nm), 9 b (λ max=424 nm), and 10 (λ max=426 nm), presumably due to strong polarization of the Ge=Ge moiety by the attached C−O double bond.13 In contrast, the longest‐wavelength absorptions of the cyclic Brook germenes 3 a–c (λ max=351, 355, and 354 nm) have been reported to be significantly blue‐shifted compared to the corresponding peaks for disilenide 1.8 Even the second absorption of 13 c at λ max=386 nm is red‐shifted compared to the bands of 3 a–c. The excellent agreement with λ max of reported germyl‐substituted ketones Et3GeCOMe (λ max=380 nm) and Ph3GeCOMe (λ max=380 nm) corroborates the presence of a C=O double bond in 13 c.19b The bathochromic shift observed in comparison to all‐organic ketones (which typically absorb in the UV region) can be explained in terms of mixing of the oxygen‐centered lone pair with the Ge−C bond.19b, 19e, 19f, 20

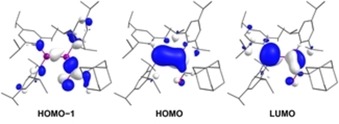

Further support for the assignment was sought by performing time‐dependent DFT calculations on 13 c at the M06‐2X(D3)/def2‐SVP level of theory. The predicted longest‐wavelength absorption at λ Ge=Ge,calc.=468 nm is in excellent agreement with the experimental value λ Ge=Ge,exp.=476 nm and is mainly due to the HOMO→LUMO transition. The second‐longest absorption wavelength λ C=O,calc.=401 nm also exhibits satisfactory agreement with the experimental value λ C=O,exp.=386 nm and stems from a complex transition with HOMO−1→LUMO as its main component. The HOMO−1 resembles the π‐symmetric nonbonding orbital of an isolated carbonyl group, whereas the HOMO is the π orbital of the Ge=Ge double bond (Figure 2).21 The two orbitals are only marginally intermixed, providing little evidence of conjugation. In contrast, the LUMO is clearly a shared π* orbital of the conjugated Ge=Ge−C=O system resulting from substantial antibonding contributions of both the Ge=Ge double bond and the carbonyl group. Overestimation of this mixing between HOMO−1 and HOMO accounts for both the blue‐shift of λ Ge=Ge and the red‐shift of λ C=O in the calculated UV/Vis spectrum. The tendency of DFT methods to overvalue conjugation is well known.22

Figure 2.

Selected Kohn–Sham orbitals of 13 c at the M06‐2X(D3)/def2‐SVP level of theory.

The strongest evidence for the existence of a persistent acyldigermene 13 c was finally provided by quenching with methanol. It should be noted that the cyclic adamantyl‐substituted Brook silene 3 b has been reported to be inert towards MeOH in the absence of a base. The cyclic structure is retained, however, after base‐catalyzed addition of MeOH to the Si=C moiety of 3 b.8 In contrast, the reaction of 13 c with MeOH in toluene proceeds even at 0 °C and results in the formation of acyldigermane 15, which can be isolated as pale‐yellow crystals in 60 % yield from a filtered and concentrated solution in hexane.

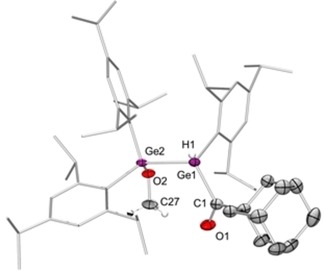

Single‐crystal X‐ray diffraction analysis confirmed the constitution of 15 as the 1,2‐addition product of methanol to the Ge=Ge bond of 13 c (Figure 3). The Ge1−Ge2 distance of 2.4694(5) Å is in the expected range for Ge−Ge single bonds. The CO double‐bond length of 1.215(3) Å is also unremarkable. The IR spectrum of 15 shows the expected bands for the Ge−H (2037 cm−1) and C=O (1647 cm−1) stretching modes, and the carbonyl moiety gives rise to a signal at δ=238.6 ppm in the 13C NMR spectrum, similar to that of the acyldigermene starting material 13 c. The similarity of the 13C NMR shifts and IR bands of α,β‐unsaturated 13 c and saturated 15 confirms that π‐conjugation between the Ge=Ge moiety and the carbonyl group in acyldigermene 13 c is insignificant and that solely the inductive effect of the digermanium moiety accounts for the observed differences to organic ketones. Conversely, the electron‐withdrawing carbonyl moiety induces strong polarization of the Ge−Ge double bond towards the acyl‐substituted terminus, as is evident from the regioselective addition of methanol.

Figure 3.

Molecular structure of acyldigermane 15 in the solid state (carbon‐bonded hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity; thermal ellipsoids drawn at 50 % probability). Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°): Ge1−Ge2 2.4694(5), Ge1−C1 2.041(3), C1−O1 1.215(3), Ge2−O2 1.8189(17); Ge1−C1−O1 118.7(2).

The sum of available evidence leaves no doubt that we have prepared the first persistent acyldigermenes 13 a–c, which, unlike the acyldisilenes (only proposed as intermediates), show no tendency for cyclization at room temperature but instead readily decompose by facile dissociation of the Ge=Ge bond. As similar conclusions apply to α‐silyldigermenes 11 a–c (see above), the electronic structures and thermodynamic properties vary substantially between functionalized disilenes and digermenes. We therefore sought to shed some light on the underlying reasons by performing DFT calculations.

Theoretical results

In order to rationalize the strongly differing inclinations of digermenes 11 a–c and 13 a–c towards cyclization compared to their lighter silicon analogues 2 a–c and 6 a,b, we took a closer look at the thermodynamics of these rearrangements (Scheme 8). To enable comparison, we restricted our investigations to those systems for which both the disilene and digermene are now known. In the case of the adamantyl‐substituted acyldigermene 13 c, the s‐cis conformer is thermodynamically favored over the s‐trans conformer (see the Supporting Information) and we generalized these findings for the remaining acylmetallenes without further verification. The calculated free enthalpies of cyclization ΔG cycl at the M06‐2X(D3)/def2‐TZVPP//BP86(D3)/def2‐SVP level of theory for α‐chlorosilyldigermenes 11 a,c, the corresponding disilenes 6 a,b, the s‐cis acyldigermenes 13 a,c, and their silicon analogues 2 a,c show a clear trend (Table 2).

Scheme 8.

Theoretically investigated cyclizations of α‐chlorosilyldimetallenes 6 a,b and 11 a,c as well as acyldimetallenes 2 a,c and 13 a,c (R=Tip=2,4,6‐iPr3C6H2; 6 a, 7 a: E=Si, R′=Me; 6 b, 7 b: E=Si, R′=Ph; 11 a, 12 a: E=Ge, R′=Me; 11 c, 12 c: E=Ge, R′=Ph; 2 a, 3 a: E=Si, R′=tBu; 2 c, 3 c: E=Si, R′=1‐adamantyl; 13 a, 14 a: E=Ge, R′=tBu; 13 c, 14 c: E=Ge, R′=1‐adamantyl).

Table 2.

Calculated free reaction enthalpies ΔG cycl at the M06‐2X(D3)/def2‐TZVPP//BP86(D3)/def2‐SVP level of theory.

|

|

E |

R′ |

ΔG cycl [kcal mol−1] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

11 a/12 a |

Ge |

Me |

+2.6 |

|

11 c/12 c |

Ge |

Ph |

+0.02 |

|

6 a/7 a |

Si |

Me |

−7.6 |

|

6 b/7 b |

Si |

Ph |

−5.1 |

|

13 a/14 a |

Ge |

tBu |

−2.5 |

|

13 c/14 c |

Ge |

1‐Ad |

−3.1 |

|

2 a/3 a |

Si |

tBu |

−17.9 |

|

2 c/3 c |

Si |

1‐Ad |

−16.9 |

While the acyclic digermenes 11 a,c and 13 a,c show slightly endergonic or exergonic ΔG cycl values near 0 kcal mol−1, the corresponding disilenes 6 a,b and 2 a,c exhibit far more negative cyclization enthalpies ranging from −5.1 to −17.9 kcal mol−1, in line with the observed trend for the formation of small rings 7 a,b and 3 a,c. Geometric ring parameters of cyclic silicon systems and their germanium analogues do not differ significantly (see the Supporting Information), and so differences in ring strain are unlikely to be a destabilizing factor. Therefore, to a first approximation, ΔG cycl can be taken as a measure of the bond dissociation energy (BDE) balance of the cyclization. While an Si−Cl bond appears in both the starting material and the product during the formation of cyclotrisilanes 7 a,b and hence is unlikely to exert a pronounced influence on ΔG cycl, the difference in BDEs of Si−Cl (ca. 100 kcal mol−1)23 and Ge−Cl (ca. 93 kcal mol−1)23 of about 7 kcal mol−1 is apparently responsible for the higher ΔG cycl values of 12 a,c. Similarly, the much more negative ΔG cycl values of acyldisilenes compared to digermenes can be rationalized in terms of the higher BDE of Si−O bonds (ca. 191 kcal mol−1) compared to Ge−O bonds (ca. 158 kcal mol−1).23

Conclusions

Functionalized digermenes, namely α‐chlorosilyldigermenes 11 a–c and acyldigermenes 13 a–c, have been synthesized and their stability has been studied. The rich cyclization chemistry of the corresponding functional disilenes appears not to be reflected by the analogous germanium systems. None of the systems shows a detectable tendency towards cyclization; instead, they slowly decompose under ambient conditions to the homoleptic Tip2Ge=GeTip2 and unidentified side products. Chlorosilyldisilenes 13 a–c have been identified by detailed comparison of their NMR spectra with those of their silicon analogues. In addition, the newly synthesized triphenylsilyldigermene 10 has been fully characterized as the first neutral digermene with an A2Ge=GeAB substitution pattern. IR and UV/Vis spectra of 13 c as well as trapping with methanol to yield digermane 15 provide evidence for the synthesis of acyldigermenes 13 a–c, which, to the best of our knowledge, are the first isolated examples of acyldimetallenes of any heavier main group element. Considering the wide scope of reactions that α,β‐unsaturated ketones are known for in organic chemistry, our current focus is on exploring the synthetic potential of 13 a–c.

Experimental Section

All reactions were carried out under a protective argon atmosphere using the Schlenk technique or gloveboxes. Pentane was heated to reflux with sodium/benzophenone and distilled prior to use. Hexane and toluene were taken directly from a solvent purification system (Innovative Technology PureSolv MD7). Deuterated benzene was heated to reflux over potassium and distilled prior to use. NMR spectra were recorded at 300 K on a Bruker Avance III 300 (1H: 300.13 MHz, 7Li: 116.59 MHz, 29Si: 59.6 MHz) or Bruker Avance III HD 400 instrument (1H: 400.13 MHz, 13C: 100.61 MHz, 29Si: 79.5 MHz). Chemical shifts are reported relative to SiMe4. UV/Vis spectra were measured on a Shimadzu UV‐2600 spectrometer from solutions in quartz cells with a path length of 1 mm. Fourier‐transform IR spectra were acquired on a Bruker Vertex 70 spectrometer in attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode. Elemental analyses were carried out on an Elementar Vario Micro Cube and show slightly suppressed carbon and hydrogen contents for digermenes 10, 11 a, and 13 a–c as a result of their extraordinary sensitivity towards oxygen. Methanol, dichlorodimethylsilane, dichloromethylphenylsilane, dichlorodiphenylsilane, pivaloyl chloride, and 2,2‐dimethylbutyryl chloride were boiled over magnesium and distilled prior to use. 1‐Adamantoyl chloride was recrystallized from hexane prior to use. Chlorotriphenylsilane was dried in vacuo and stored under argon prior to use. Digermenide 8 was prepared according to our published procedure.13 For theoretical data, crystallographic details, and plots of spectra, see the Supporting Information. CCDC https://summary.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structure-summary?doi=10.1002/chem.201902553 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data are provided free of charge by http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/.

Synthesis and characterization

Tip2Ge=Ge(Tip)SiPh3 (10): Digermenide 8 (600 mg, 0.58 mmol) and chlorotriphenylsilane (171 mg, 0.58 mmol, 1 equiv.) were mixed as solids in a Schlenk flask and toluene (6 mL) was added by means of a syringe. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature, whereupon a white precipitate was formed. After removal of the solvent in vacuo, hexane (10 mL) was added, and the mixture was filtered through a cannula to remove insoluble material. Reducing the volume to approximately 1.5 mL gave a dark‐red solution, from which 308 mg (52 %) of digermene 10 was obtained as crystalline yellow plates (m.p. 177 °C; dec.). 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6, 300 K, TMS): δ=7.75 (d, 3 J=6.88 Hz, 6 H; m‐Ph‐H), 7.06 (s, 2 H; Tip‐H), 7.05 (br, 3 H; p‐Ph‐H), 7.01 (s, 2 H; Tip‐H), 6.99 (s, 3 H; o‐Ph‐H), 6.97 (s, 3 H; o‐Ph‐H), 6.95 (s, 2 H; Tip‐H), 3.85 (sept, 3 J=6.61 Hz, 2 H; iPr‐CH), 3.80–3.69 (m, 4 H; iPr‐CH), 2.73 (sept, 3 J=6.90 Hz, 3 H; iPr‐CH), 1.26 (br d, 6 H; iPr‐CH 3), 1.20, 1.17, 1.14 (each d, 3 J=6.94 Hz, 6 H each; iPr‐CH 3), 1.10–0.84 (d & v br, 3 J=6.54 Hz, altogether 24 H; iPr‐CH 3), 0.74 ppm (br d, 6 H; iPr‐CH 3); 13C NMR (100.61 MHz, C6D6, 300 K, TMS): δ=153.2, 152.9, 151.9, 149.8, 149.4, 149.2, 146.4, 143.9, 139.7 (each s; Tip‐C), 136.9, 136.0, 129.1, 127.5 (each s; Ph‐C), 122.3, 122.0, 121.4 (each s; Tip‐C), 38.3, 37.1, 37.0, 34.3, 34.2, 34.1 (each s; iPr‐CH), 24.8, 24.4, 24.1, 23.9, 23.9, 23.7 ppm (each s, iPr‐CH3); 29Si{1H} NMR (79.5 MHz, C6D6, 300 K, TMS): δ=1.9 ppm; UV/Vis (hexane): λ max=425 nm (ϵ=20843 L mol−1 cm−1); elemental analysis calcd (%) for C63H84Ge2Si (1014.71): C 74.57, H 8.34; found: C 73.26, H 8.02.

Tip2Ge=Ge(Tip)SiMe2Cl (11 a): Digermenide 8 (212 mg, 0.2 mmol) was dissolved in toluene (8 mL) and the solution was cooled to −60 °C. Dropwise addition to a solution of dichlorodimethylsilane (53 mg, 50 μL, 0.41 mmol, 2 equiv.) in toluene (2 mL) at −60 °C led to an immediate color change to bright‐orange. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight and allowed to reach room temperature. After removal of the solvent and volatiles in vacuo, hexane (6 mL) was added and the mixture was filtered. Although formation of 11 a and the purity of the orange‐red filtrate were confirmed by NMR spectroscopy, no crystals could be obtained under any conditions. 1H NMR (400.13 MHz, C6D6, 300 K, TMS): δ=7.12, 7.09, 7.02 (each s, 2 H each, altogether 6 H; Tip‐H), 3.89, 3.75, 3.59 (each sept, 3 J=6.75 Hz, 2 H each, altogether 6 H; Tip‐Pr‐CH), 2.85–2.63 (m, 3 H; Tip‐Pr‐CH), 1.33 (d, 3 J=6.47 Hz, 12 H; Tip‐Pr‐CH 3), 1.27 (br d, 3 J=6.07 Hz, 9 H; Tip‐Pr‐CH 3), 1.21, 1.18 (each d, 3 J=6.85 Hz, 9 H each; Tip‐Pr‐CH 3), 1.11 (d, 3 J=6.85 Hz, 6 H; Tip‐Pr‐CH 3), 0.99 (d, 3 J=6.85 Hz, 9 H; Tip‐Pr‐CH 3), 0.58 ppm (s, 6 H; Si‐CH 3); 13C NMR (100.61 MHz, C6D6, 300 K, TMS): δ=153.1, 153.4, 152.5, 150.9, 150.1, 149.8, 145.8, 143.7, 139.3, 122.6, 122.4, 122.0 (Tip‐Ar‐C), 38.7, 37.6, 37.5, 34.8, 34.7, 34.4 (Tip‐Pr‐CH), 25.3, 25.0, 24.6, 24.3, 24.2, 24.0 (Tip‐Pr‐CH3), 7.4 ppm (Si‐CH3); 29Si{1H} NMR (79.5 MHz, 300 K, C6D6, TMS): δ=31.5 ppm; UV/Vis (hexane): λ max=435 nm (ϵ=11 080 L mol−1 cm−1); elemental analysis calcd (%) for C47H75ClGe2Si (848.91): C 66.50, H 8.91; found: C 65.60, H 8.55.

Tip2Ge=Ge(Tip)SiMePhCl (11 b): Digermenide 8 (265 mg, 0.26 mmol) was dissolved in toluene (8 mL) and the solution was cooled to −60 °C. Dropwise addition to a solution of dichloromethylphenylsilane (59 mg, 50 μL, 0.31 mmol, 1.2 equiv.) in toluene (2 mL) at −60 °C led to an immediate color change to bright‐orange. The reaction mixture was allowed to reach room temperature, whereupon it turned yellow‐green due to the formation of a small amount of tetragermabutadiene (not detectable in the 1H NMR spectrum). After removal of the solvent and volatiles in vacuo at 60 °C, hexane (8 mL) was added and the mixture was filtered. Although formation of 11 b and the purity of the product solution were confirmed by NMR spectroscopy, no crystals could be obtained under any conditions. 1H NMR (400.13 MHz, C6D6, 300 K, TMS): δ=7.74 (d, J=6.58 Hz, 2 H; Si‐Ph‐H), 7.12 (s, 2 H; Tip‐H), 7.03 (s, 2 H; Tip‐H), 7.03 (s, 2 H; Tip‐H), 7.00–6.90 (m, 3 H, overlapping with MePhSiCl2; Si‐Ph‐H), 3.92 (sept, 3 J=7.05 Hz, 2 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 3.76 (sept, 3 J=7.05 Hz, 2 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 3.62 (sept, 3 J=6.35 Hz, 2 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 2.79–2.63 (m, 3 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 1.28 (d, 3 J=6.30 Hz, 12 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3), 1.20, 1.17 (each d, 3 J=7.16 Hz, altogether 18 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3), 1.11 (d, 3 J=6.77 Hz, 12 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3), 1.04 (d, 3 J=6.77 Hz, 6 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3), 0.96 (d, 3 J=6.37 Hz, 6 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3), 0.81 ppm (s, 3 H, Si‐CH 3); 13C NMR (100.61 MHz, C6D6, 300 K, TMS): δ=154.2, 154.2, 152.5, 150.9, 150.2, 149.9, 146.0, 144.0, 138.0 (Tip‐Ar‐C), 134.7 (Si‐Ph‐C), 133.7 (Cl2MeSiPh‐C), 133.5 (Si‐Ph‐C), 133.4, 131.7 (Cl2MeSiPh‐C), 131.2, 130.2 (Si‐Ph‐C), 128.6 (Cl2MeSiPh‐C), 122.7, 122.4, 122.1 (Tip‐Ar‐C), 37.7, 37.6, 34.7, 34.7, 34.4 (Tip‐iPr‐CH), 24.9, 24.6, 24.6, 24.2, 24.2, 24.0, 24.0 (Tip‐iPr‐CH3), 6.8 (Si‐CH3), 5.1 ppm (Cl2PhSi‐CH3); 29Si{1H} NMR (79.5 MHz, 300 K, C6D6, TMS): δ=23.7 ppm.

Tip2Ge=Ge(Tip)SiPh2Cl (11 c): Digermenide 8 (246 mg, 0.24 mmol) was dissolved in toluene (5 mL) and the solution was cooled to −70 °C. Dropwise addition to a solution of dichlorodiphenylsilane (60.4 mg, 50 μL, 0.24 mmol, 1 equiv.) in toluene (2 mL) at −70 °C led to an immediate color change to dark‐red‐orange. The reaction mixture was allowed to reach room temperature, whereupon it turned deep‐green due to the formation of tetragermabutadiene (ca. 2 %, as determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy). After removal of the solvent and volatiles in vacuo, hexane (8 mL) was added, the mixture was filtered, and the filtrate was concentrated to a volume of 1 mL. At −26 °C, traces of tetragermabutadiene crystallized, which could be filtered off from the orange mother liquor. Although the formation of 11 c was confirmed by NMR spectroscopy, no crystals could be obtained under any conditions due to the presence of side products. 1H NMR (400.13 MHz, C6D6, 300 K, TMS): Due to strong overlap with the signals of Tip4‐digermene, tetragermabutadiene, toluene, and remaining Ph2SiCl2, detailed assignment and integration of the signals was only possible to a limited extent. δ=7.65 (dd, 3 J=7.91 Hz, 4 J=1.53 Hz, 4 H; Ph‐H), 7.07–6.97 (m, 8 H; Tip‐H & Ph‐H, masked by signals of side products), 6.90 (t, 3 J=7.51 Hz, 4 H; Ph‐H), 3.87–3.73 (m, 4 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 3.59 (sept, 3 J=6.44 Hz, 2 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 2.77–2.65 (m, 3 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH, overlapping with signals of side products), 1.21–1.17 (m, 18 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3, overlapping with signals of side products), 1.13–1.08 (m, 24 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3, overlapping with signals of side products), 0.99 ppm (d, 3 J=6.54 Hz, 12 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3); 13C NMR (100.61 MHz, C6D6, 300 K, TMS): δ=154.0, 153.3, 152.2, 150.7, 150.1, 149.8, 146.4, 144.2, 138.7 (Tip‐Ar‐C), 137.8 (Tol‐Ar‐C), 136.5, 135.9, 134.5, 134.4, 132.2, 131.8, 130.3 (Ph‐Ar‐C), 129.2, 128.5 (Tol‐Ar‐C), 128.5 (Ph‐Ar‐C), 125.6 (Tol‐Ar‐C), 122.7, 122.3, 121.8 (Tip‐Ar‐C), 38.8, 38.0, 37.3, 34.6, 34.5, 34.3 (Tip‐iPr‐CH), 24.9, 24.5, 24.2, 24.1, 24.0, 23.9 (Tip‐iPr‐CH3), 7.4 ppm (toluene‐CH3); 29Si{1H} NMR (79.5 MHz, 300 K, C6D6, TMS): δ=15.2 ppm.

Tip2Ge=Ge(Tip)‐CO‐tBu (13 a): Pivaloyl chloride (4.0 μL, 0.032 mmol, 1 equiv.) was added at room temperature to a solution of digermenide 8 (30 mg, 0.032 mmol) in C6D6 (0.5 mL). The solution instantly turned dark‐red and 1H NMR confirmed the selective formation of acyldigermene 13 a. In an attempted crystallization, digermenide 8 (402 mg, 0.389 mmol) was suspended in pentane (8 mL) and pivaloyl chloride (48 μL, 0.389 mmol, 1 equiv.) was added, which again afforded a dark‐red solution. Insoluble material was filtered off after stirring for 15 min at room temperature, and the filtrate was concentrated. Crystals of 13 a could not be obtained. 1H NMR (300 MHz, C6D6, 300 K, TMS): δ=7.10 (s, 2 H; Tip‐H), 7.07 (s, 4 H; Tip‐H), 3.97 (sept, 3 J=6.74 Hz, 2 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 3.70 (sept, 3 J=6.78 Hz, 4 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 3.33, 3.13 (each s, altogether 20 H; dme), 2.77–2.68 (m, 3 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 1.24–1.15 ppm (m, 63 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3, tBu‐CH 3); 13C NMR (75 MHz, C6D6, 300 K, TMS): δ=154.3, 153.4, 150.4, 150.3, 142.4, 141.6, 122.5, 122.0 (Tip‐Ar‐C), 72.2 (dme), 58.7 (dme), 38.4, 36.2, 34.7, 34.6 (Tip‐iPr‐CH), 28.0, 25.2, 25.0 (Tip‐iPr‐CH3), 24.5 (tBu‐C), 24.2 (Tip‐iPr‐CH3), 24.1 ppm (tBu‐CH3); UV/Vis (hexane): λ max=472 (4770), 383 nm (2750 L mol−1 cm−1); IR (powder): ν(CO)=1652 cm−1; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C50H78Ge2O (840.43): C 71.46, H 9.36; found: C 70.61, H 9.03.

Tip2Ge=Ge(Tip)‐CO‐tPent (13 b): 2,2‐Dimethylbutyryl chloride (4.0 μL, 0.029 mmol) was added at room temperature to a solution of digermenide 8 (30 mg, 0.029 mmol) in C6D6 (0.5 mL). The solution instantly turned dark‐red and 1H NMR confirmed the selective formation of acyldigermene 13 b. In an attempted crystallization, digermenide 8 (383 mg, 0.406 mmol) was suspended in pentane (6.5 mL) and 2,2‐dimethylbutyryl chloride (56 μL, 0.406 mmol, 1 equiv.) was added, which again afforded a dark‐red solution. After stirring for 15 min at room temperature, insoluble material was filtered off, and the filtrate was concentrated. A second crystallization attempt was made from hexane instead of pentane, but in neither case were crystals of 13 b obtained. 1H NMR (300 MHz, C6D6, 300 K, TMS): δ=7.13 (s, 2 H; Tip‐H), 7.09 (s, 4 H; Tip‐H), 4.03 (sept, 3 J=7.30 Hz, 2 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 3.75 (sept, 3 J=7.30 Hz, 4 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 3.34, 3.13 (each s, altogether 30 H; dme), 2.75–2.73 (m, 3 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 1.65 (quart, 3 J=7.63 Hz, 2 H; tpentyl‐CH 2), 1.24, 1.23 (each d, 3 J=6.80 Hz, altogether 36 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3), 1.18–1.15 (m, 24 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3, tpentyl‐CH 3), 0.79 ppm (t, 3 J=7.30 Hz, 3 H; tpentyl‐CH2‐CH 3); 13C NMR (75 MHz, C6D6, 300 K, TMS): δ=154.4, 153.5, 150.4, 150.3, 142.6, 122.5, 121.9 (Tip‐Ar‐C), 72.3 (dme), 58.7 (dme), 38.4, 35.8, 34.7, 34.6 (Tip‐iPr‐CH), 25.3, 25.0 (Tip‐iPr‐CH3), 24.9 (C quart.), 24.1, 24.1 (iPr‐CH3, tpentyl‐CH3), 8.9 ppm (tpentyl‐CH3); UV/Vis (hexane): λ max=474 (4820), 382 nm (2780 L mol−1 cm−1); IR (powder): ν(CO)=1653 cm−1; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C51H80Ge2O (854.46): C 71.69, H 9.44; found: C 70.94, H 9.08.

Tip2Ge=Ge(Tip)‐CO‐1‐Ad (13 c): 1‐Adamantoyl chloride (6.4 mg, 0.032 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) in C6D6 (0.25 mL) was added at room temperature to a solution of digermenide 8 (30 mg, 0.032 mmol) in C6D6 (0.25 mL). The solution instantly turned dark‐red and 1H NMR confirmed the selective formation of acyldigermene 13 c. In an attempted crystallization, pentane (5 mL) was added to a mixture of digermenide 8 (300 mg, 0.318 mmol) and 1‐adamantoyl chloride (63 mg, 0.318 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), which again afforded a dark‐red solution. After stirring for 15 min at room temperature, insoluble material was filtered off, and the filtrate was concentrated. A second crystallization attempt was made using hexane instead of pentane, but in neither case were crystals of 13 c obtained. 1H NMR (300 MHz, C6D6, 300 K, TMS): δ=7.13 (s, 2 H; Tip‐H), 7.09 (s, 4 H; Tip‐H), 4.04 (sept, 3 J=7.11 Hz, 2 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 3.76 (br sept, 3 J=6.56 Hz, 4 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 3.34, 3.13 (each s, altogether 20 H; dme), 2.74 (sept, 3 J=6.85 Hz, 3 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 2.01 (s, 6 H; Ad‐α‐CH 2), 1.79 (s, 3 H; Ad‐β‐CH), 1.50 (s, 6 H; Ad‐γ‐CH 2), 1.28–1.23 (m, 36 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3), 1.18–1.15 ppm (m, 18 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3); 13C NMR (100.61 MHz, C6D6, 300 K, TMS): δ=232.4 (C=O), 154.4, 153.4, 150.4, 150.2, 142.5, 141.4 (Tip‐Ar‐C), 127.9 (Tip‐Ar‐C, masked by solvent), 122.5, 121.9 (Tip‐Ar‐C), 72.3, 58.7 (dme), 51.5 (br; Ad‐C quart), 40.5 (br; Ad‐α‐CH2), 38.5, 37.0 (Tip‐iPr‐CH), 36.0 (br; Ad‐γ‐CH2), 34.6 (Tip‐iPr‐CH), 28.7 (Ad‐β‐CH), 25.3, 25.1, 24.1 ppm (Tip‐iPr‐CH3); UV/Vis (hexane): λ max=476 (4140), 385 nm (2240 L mol−1 cm−1); IR (powder): ν(CO)=1649 cm−1; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C55H82Ge2O (918.55): C 73.23, H 9.22; found: C 72.22, H 9.15.

Tip2(OMe)Ge−GeH(Tip)‐CO‐1‐Ad (15): 1‐Adamantoyl chloride (50.7 mg, 0.26 mmol, 1.0 equiv.) and digermenide 8 (240 mg, 0.26 mmol) were combined in a flask and toluene (5 mL) was added. The reaction mixture immediately turned dark‐orange and was then cooled to −60 °C. Neat MeOH (12 μL, 9.8 mg, 0.31 mmol, 1.2 equiv.) was added to the cold reaction mixture and the cooling bath was removed. After reaching room temperature, all volatiles were removed from the green solution in vacuo and the remaining solid was redissolved in hexane (10 mL). The solution was filtered through a cannula. The green filtrate was concentrated to about 1 mL and stored at room temperature overnight, whereupon digermane 15 crystallized as 146 mg (60 %) of pale‐yellow needles. 1H NMR (400.13 MHz, C6D6, 300 K, TMS): The crystalline sample of 15 contained approximately 10 % of the regioisomer Tip2HGe−Ge(OMe)(Tip)‐CO‐1‐Ad 15′ , which could not be removed by purification methods due to the chemical similarity between 15 and 15′ . Hence, integrals are overestimated in the spectrum. δ=7.22 (d, 1 H; Tip‐H), 7.16 (br, masked by signal of C6D5H, 1 H; Tip‐H), 7.08 (d, 1 H; Tip‐H), 7.02 (d, 1 H; Tip‐H), 6.98 (d, 1 H; Tip‐H), 6.89 (d, 1 H; Tip‐H), 6.46 (s, 1 H; Ge‐H), 3.90 (s, 3 H; OCH 3), 3.80 (sept, 1 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 3.61 (sept, 1 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 3.50 (sept, 1 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 3.38 (sept, 1 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 3.24 (sept, 1 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 2.94 (sept, 1 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 2.83–2.64 (m, 3 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH), 2.08 (br d, 3 H; Ad‐α‐CH 2), 1.90 (br d, 3 H; Ad‐α‐CH 2), 1.76 (br, 3 H; Ad‐β‐CH), 1.63 (d, 3 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3), 1.55, 1.53 (each d, altogether 6 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3), 1.43 (br, 6 H; Ad‐γ‐CH 2), 1.41 (d, 3 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3), 1.35 (d, 6 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3), 1.31 (d, 3 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3), 1.22 (d, 3 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3), 1.20 (d, 3 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3), 1.18–1.12 (m, 15 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3), 0.47 (d, 6 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3), 0.39 (d, 3 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3), 0.33 ppm (d, 3 H; Tip‐iPr‐CH 3); 13C NMR (100.61 MHz, C6D6, 300 K, TMS): δ=238.6 (C=O), 155.8, 155.3, 155.1, 153.6, 153.5, 152.1, 150.7, 150.4, 150.0, 137.2, 136.8, 132.5, 123.3, 123.1, 122.8, 122.6, 122.2, 121.9 (Tip‐Ar‐C), 55.4 (Ad‐C quat), 53.9 (O‐CH3), 38.4, 36.8, 36.3, 35.6, 35.5, 34.6, 33.1, 32.4 (Tip‐iPr‐CH, Ad‐CH, and Ad‐CH2), 28.3, 27.5, 26.9, 25.7, 25.1, 24.9, 24.9, 24.6, 24.3, 24.2, 24.2, 24.1, 24.0, 24.0, 23.9, 23.4, 23.1, 22.9 ppm (Ad‐CH2 and Tip‐iPr‐CH3); IR (powder): ν=1647 (CO), 2037 cm−1 (Ge−H); m.p. >220 °C; elemental analysis calcd (%) for C57H88Ge2O2 (950.59): C 72.02, H 9.33; found: C 72.17, H 8.99.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

Support of this study by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG SCHE906/5‐1) is gratefully acknowledged.

L. Klemmer, Y. Kaiser, V. Huch, M. Zimmer, D. Scheschkewitz, Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 12187.

The copyright line for this article was changed on 23 October 2019 after original online publication.

References

- 1. Goldberg D. E., Harris D. H., Lappert M. F., Thomas K. M., J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1976, 227, 261. [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. West R., Fink M. J., Science 1981, 214, 1343–1344; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Hitchcock P. B., Lappert M. F., Miles S. J., Thorne A. J., J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1984, 480–482; [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Stender M., Phillips A. D., Wright R. J., Power P. P., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1785–1787; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2002, 114, 1863–1865; [Google Scholar]

- 2d. Sekiguchi A., Kingo R., Ichinohe M., Science 2004, 305, 1755–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Wiberg N., Niedermayer W., Polborn K., Mayer P., Chem. Eur. J. 2002, 8, 2730–2739; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Fanta A. D., DeYoung D. J., Belzner J., West R., Organometallics 1991, 10, 3466–3470; [Google Scholar]

- 3c. Fanta A. D., Belzner J., Powell D. R., West R., Organometallics 1993, 12, 2177–2181; [Google Scholar]

- 3d. Fink M. J., DeYoung D. J., West R., Michl J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105, 1070–1071; [Google Scholar]

- 3e. Batcheller S. A., Masamune S., Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29, 3383–3384. [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Weidenbruch M., Kroke E., Marsmann H., Pohl S., Saak W., J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1994, 1233–1234; [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Dixon C. E., Liu H. W., Vander Kant C. M., Baines K. M., Organometallics 1996, 15, 5701–5705; [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Dixon C. E., Cooke J. A., Baines K. M., Organometallics 1997, 16, 5437–5440; [Google Scholar]

- 4d. Sasamori T., Sugahara T., Agou T., Sugamata K., Guo J. D., Nagase S., Tokitoh N., Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 5526–5530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. De Young D. J., West R., Chem. Lett. 1986, 15, 883–884; [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Wiberg N., Niedermayer W., Polborn K., Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2002, 628, 1045–1052; [Google Scholar]

- 5c. Gottschling S. E., Milnes K. K., Jennings M. C., Baines K. M., Organometallics 2005, 24, 3811–3814; [Google Scholar]

- 5d. Gottschling S. E., Jennings M. C., Baines K. M., Can. J. Chem. 2005, 83, 1568–1576; [Google Scholar]

- 5e. Milnes K. K., Jennings M. C., Baines K. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 2491–2501; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5f. Majumdar M., Bejan I., Huch V., White A. J. P., Whittell G. R., Schäfer A., Manners I., Scheschkewitz D., Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 9225–9229; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5g. Henry A. T., Bourque J. L., Vacirca I., Scheschkewitz D., Baines K. M., Organometallics 2019, 38, 1622–1626; [Google Scholar]

- 5h. Weidenbruch M., Hagedorn A., Peters K., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 34, 1085–1086; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 1995, 107, 1187–1188; [Google Scholar]

- 5i. Hurni K. L., Baines K. M., Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 8382–8384; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5j. Milnes K. K., Pavelka L. C., Baines K. M., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 1019–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Scheschkewitz D., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 2965–2967; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2004, 116, 3025–3028; [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Ichinohe M., Sanuki K., Inoue S., Sekiguchi A., Organometallics 2004, 23, 3088–3090. [Google Scholar]

- 7.

- 7a. Scheschkewitz D., Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 2476–2485; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Scheschkewitz D., Chem. Lett. 2011, 40, 2–11; [Google Scholar]

- 7c. Präsang C., Scheschkewitz D., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 900–921; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7d. Rammo A., Scheschkewitz D., Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 6866–6885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bejan I., Güclü D., Inoue S., Ichinohe M., Sekiguchi A., Scheschkewitz D., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 3349–3352; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2007, 119, 3413–3416. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bejan I., Inoue S., Ichinohe M., Sekiguchi A., Scheschkewitz D., Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 7119–7122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Fernández I., Frenking G., Chem. Eur. J. 2006, 12, 3617–3629; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Xi H.-W., Karni M., Apeloig Y., J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 13066–13079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhao H., Klemmer L., Cowley M. J., Majumdar M., Huch V., Zimmer M., Scheschkewitz D., Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 8399–8402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abersfelder K., Scheschkewitz D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 4114–4121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nieder D., Klemmer L., Kaiser Y., Huch V., Scheschkewitz D., Organometallics 2018, 37, 632–635. [Google Scholar]

- 14.

- 14a. Baines K. M., Cooke J. A., Organometallics 1991, 10, 3419–3421; [Google Scholar]

- 14b. Kollegger G. M., Stibbs W. G., Vittal J. J., Baines K. M., Main Group Met. Chem. 1996, 17, 317–330; [Google Scholar]

- 14c. Lee V. Ya., Yasuda H., Ichinohe M., Sekiguchi A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 6378–6381; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2005, 117, 6536–6539; [Google Scholar]

- 14d. Lee V. Ya., Yasuda H., Ichinohe M., Sekiguchi A., J. Organomet. Chem. 2007, 692, 10–19. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schäfer H., Saak W., Weidenbruch M., Organometallics 1999, 18, 3159–3163. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fischer R. C., Power P. P., Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 3877–3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kira M., Iwamoto T., Maruyama T., Kabuto C., Sakurai H., Organometallics 1996, 15, 3767–3769. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schäfer H., Saak W., Weidenbruch M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 3703–3705; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2000, 112, 3847–3849. [Google Scholar]

- 19.

- 19a. Yates K., Agolini F., Can. J. Chem. 1966, 44, 2229–2231; [Google Scholar]

- 19b. Brook A. G., Duff J. M., Jones P. F., Davis N. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 431–434; [Google Scholar]

- 19c. Castel A., Rivière P., Satagé J., Desor D., Ahbala M., Abdenadher C., Inorg. Chim. Acta 1993, 212, 51–55; [Google Scholar]

- 19d. Bravo-Zhivotovskii D. A., Pigarev S. D., Kalikhman I. D., Vyazankina O. A., Vyazankin N. S., J. Organomet. Chem. 1983, 248, 51–60; [Google Scholar]

- 19e. Peddle G. J. D., J. Organomet. Chem. 1966, 5, 486–488; [Google Scholar]

- 19f. Brook A. G., Pierce J. B., Can. J. Chem. 1964, 42, 298–304. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ramsey B. G., Brook A., Bassindale A. R., Bock H., J. Organomet. Chem. 1974, 74, C41–45. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Orloff M. K., Colthup N. B., J. Chem. Educ. 1973, 50, 400–401. [Google Scholar]

- 22.

- 22a. Korth M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 5396–5398; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 5482–5484; [Google Scholar]

- 22b. Janesko B. G., Proynov E., Kong J., Scalmani G., Frisch M. J., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 4314–4318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Luo Y.-R., Comprehensive Handbook of Chemical Bond Energies, Taylor & Francis, 2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary