Abstract

Objectives:

In the United States, about 15% of persons living with HIV infection do not know they are infected. Opt-out HIV screening aims to normalize HIV testing by performing an HIV test during routine medical care unless the patient declines. The primary objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to assess the acceptance of opt-out HIV screening in outpatient settings in the United States.

Methods:

We searched in PubMed and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) for studies published from January 1, 2006, through December 31, 2018, of opt-out HIV screening in outpatient settings. We collected data from selected studies and calculated for each study (1) the percentage of persons who were offered HIV testing, (2) the percentage of persons who accepted the test, and (3) the percentage of new HIV diagnoses among persons tested. We also collected information on the reasons given by patients for opting out. The meta-analysis used a random-effects model to estimate the average percentages of HIV testing offered, HIV testing accepted, and new HIV diagnoses.

Results:

We initially identified 6986 studies; the final analysis comprised 14 studies. Among the 8 studies that reported the size of the study population eligible for HIV screening, 71.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 53.9%-89.0%) of the population was offered an HIV test on an opt-out basis. The test was accepted by 58.7% (95% CI, 47.2%-70.2%) of persons offered the test. Among 9 studies that reported data on new HIV diagnoses, 0.18% (95% CI, 0.08%-0.26%) of the persons tested had a new HIV diagnosis. Patients’ most frequently cited reasons for refusal of HIV screening were that they perceived a low risk of having HIV or had previously been tested.

Conclusions:

The rates of offering and accepting an HIV test on an opt-out basis could be improved by addressing health system and patient-related factors. Setting a working target for these rates would be useful for measuring the success of opt-out HIV screening programs.

Keywords: HIV, routine, opt-out, screening, outpatient

In the United States, an estimated 1.1 million persons were living with HIV as of 2015. Of those persons, about 15%, or 1 in 7, did not know they were infected.1 In 2006, the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended routinely screening persons aged 13-64 in all health care settings, unless the documented prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection in the area was <0.1%. CDC also recommended that persons at high risk for HIV infection be screened annually, that persons being testing for sexually transmitted infections be screened at each visit, and that persons initiating tuberculosis treatment be screened routinely. The recommendation further called for this routine screening to be performed on an opt-out basis; that is, the HIV testing will be performed unless the patient declines after being notified of the testing.2 In opt-out screening, patient consent for HIV testing is covered by the consent for medical treatment that patients provide when they seek medical care. This screening approach is believed to increase the number of persons who are aware of their HIV infection, identify HIV infection at an early stage, reduce mother-to-child HIV transmission, reduce stigma associated with HIV testing, and enable those who are infected to take steps to protect the health of their partners.3

In 2013, the US Preventive Services Task Force supported CDC’s recommendation for routine HIV screening because of the high certainty of substantial benefit and recommended that clinicians routinely screen adolescents and adults aged 15-65 for HIV infection.4 Other professional organizations, such as the American College of Physicians5 and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,6 also recommend routine opt-out HIV screening for the population groups they care for.

A 2017 systematic review reported the percentages of persons who accepted an HIV test and new HIV diagnoses in opt-in and opt-out HIV screening programs in emergency departments.7 The systematic review found that acceptance of HIV testing was 44% in the opt-out strategy and 19% in the opt-in strategy. The prevalence of new HIV infection was 0.40% in populations screened in the opt-out strategy and 0.52% in populations screened in the opt-in strategy. To our knowledge, the percentage of persons accepting HIV screening and the percentage of new HIV diagnoses in non–emergency department outpatient settings that use the opt-out strategy have not been systematically reviewed. The objective of our study was to describe the percentage of patients who were offered HIV testing on an opt-out basis (ie, informing patients that they will be tested for HIV unless they decline), the percentage of persons who accepted testing, the percentage of new HIV diagnoses, and reasons for opting out in non–emergency department outpatient settings in the United States.

Methods

Search Strategy

Using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses guidelines,8 we systematically reviewed studies reporting opt-out HIV screening programs in outpatient settings in the United States. We searched in PubMed and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) for studies published from January 1, 2006, through December 31, 2018. We did not apply a language restriction, and we used multiple search terms (Box). We identified additional studies through a manual search of bibliographies. The search was conducted on September 20, 2017, and was later updated on February 2, 2019.

Box.

Keywords used to search for studies reporting opt-out HIV screening programs in outpatient settings in the United States, in PubMed and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), January 1, 2006, through December 31, 2018

PubMed

“HIV” [MeSH] or “human immunodeficiency virus” AND “diagnostic tests, routine” [MeSH] OR “routine” OR “opt-out” OR “nurse-driven” OR “physician-driven” OR “nurse initiated” OR “physician initiated” OR “universal” OR “provider-initiated” OR “non-targeted” AND “mass screening” [MeSH] OR “detect” OR “detected” OR “detecting” OR “test” OR “tested” OR “testing” OR “screen” OR “screened” OR “screening”

CINAHL

MH “human immunodeficiency virus” OR “HIV” AND MH “diagnostic tests, routine” OR “routine” OR “opt-out” OR “nurse-driven” OR “physician-driven” OR “nurse initiated” OR “physician initiated” OR “universal” OR “provider-initiated” OR “non-targeted” AND MH “health screening” OR “detect” OR “detected” OR “detecting” OR “test” OR “tested” OR “testing” OR “screen” OR “screened” OR “screening”

Inclusion Criteria

The criteria for studies to be included in this review were as follows: the study (1) reported screening on an opt-out basis (testing conducted as part of routine care, where patients were told the test would be conducted unless they opted out and declined testing), (2) reported acceptance of the HIV test, and (3) was conducted from January 1, 2006, through December 31, 2018, in outpatient settings in the United States.

Exclusion Criteria

We excluded studies that indicated opt-in or other types of HIV testing approaches, such as targeted, risk-based, community outreach testing; home-based testing; or self-testing, because our objective was to assess only the opt-out approach. We also excluded studies conducted in emergency departments, inpatient settings, antenatal settings, and jails or prisons, because some of these settings (eg, emergency departments) were assessed previously, and the screening approach in these settings is often unique to the populations served.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

One researcher (M.T.G.) conducted the database searches. After removing duplicates, 2 researchers (M.T.G. and D.E.M.) independently screened titles and abstracts and chose studies that reported opt-out HIV screening in outpatient settings in the United States for further evaluation. The 2 researchers then conducted full-text screening by using all inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Two researchers (M.T.G. and D.E.M.) independently extracted the data. Variables in the data extraction tool were author, publication year, period in which the study was conducted, place the study was conducted, type of health care facility in which the study was conducted, number of persons who were eligible for HIV screening, age group of population studied, number of persons who were offered an HIV test on an opt-out basis, number of persons who accepted the test, number of persons who tested positive for HIV, and reasons for declining HIV screening. “Persons who were eligible for HIV screening” was defined as persons who visited a health care facility for purposes other than obtaining an HIV test and who, according to CDC’s 2006 guidelines, should be screened for HIV.

Data Analysis

First, we used the reported data in each selected study to calculate percentages and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the 3 percentages we were interested in. Then, we estimated the combined percentage of persons who were offered an HIV test, the combined percentage of persons who accepted the test, and the combined percentage of new HIV diagnoses by combining data from the selected studies in a meta-analysis. Because we found high levels of heterogeneity among the studies included in the meta-analysis, we used a random-effects model to estimate the summary percentages. For the assessment of the percentage of persons who were offered an HIV test, we examined all studies that reported the number of persons eligible for HIV screening. For the assessment of the percentage of persons who accepted the test, we included all studies that reported data on acceptance. For the assessment of the percentage of new HIV diagnoses, we included all studies that reported test results.

To determine whether the 3 percentages of interest varied (ie, the level of heterogeneity of each outcome) across the studies selected, we used the I 2 and χ2 tests for heterogeneity. The I 2 statistic describes the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to real heterogeneity rather than chance. A value of 0% indicates no heterogeneity, and heterogeneity increases as values increase to a maximum of 100%. We conducted subgroup analysis by region to explain any heterogeneity.

We assessed publication bias by visually inspecting funnel plots. A funnel plot is a simple scatter plot that plots estimated percentages on the x-axis and the sample size or index precision on the y-axis. Publication bias will produce an asymmetrical funnel plot, with a gap in a bottom corner of the graph. A lack of publication bias will produce a symmetrical funnel plot resembling an inverted funnel. We also checked the statistical significance of the funnel plots’ symmetry by using the Egger test; publication bias exists (ie, an asymmetrical funnel plot is created) if P < .10. We analyzed data by using Stata version 11.9

Quality Assessment

We used the Joanna Briggs Institute’s Critical Appraisal Checklist for Prevalence Studies to assess the quality of the studies.10 This checklist consists of 9 items related to sampling, sample size, description of study settings, methods, and data analysis. The responses to the items are framed as “1” for yes, “0” for no, “unclear,” or “not applicable.” Two items on this checklist did not apply to the objectives of our study, so we did not use them. We calculated a total score for each study as the sum of 7 items. Two authors (M.T.G. and D.E.M.) separately assessed the quality of each study. A score of 6 or 7 indicates good quality, a score of 4 or 5 indicates moderate quality, and a score of <4 indicates poor quality.

Results

The search of the PubMed and CINAHL databases yielded 6969 publications (Figure 1). We identified an additional 17 publications in the manual search of bibliographies. After we removed duplicates (n = 1286), 5700 publications remained; after screening titles and abstracts of the 5700 publications, 137 remained for full-text review. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria to the 137 publications, 14 publications11-24 remained and were included in the final synthesis of the systematic review and meta-analysis (Table). These publications described studies that included a combined total of 164 040 persons who were offered an HIV test on an opt-out basis. Thirteen studies were cross-sectional, and 1 was quasi-experimental.20

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses flow chart for search process and studies selection in a review of studies reporting opt-out HIV screening programs in outpatient settings in the United States, January 1, 2006, through December 31, 2018.

Table.

Numbers of persons who were offered and accepted an HIV test on an opt-out basis and who tested positive for HIV, as reported by studies conducted in non-emergency department outpatient settings in the United States and included in the systematic review, 2006-2018

| Principal Author (Year of Publication) | Study Period | Location of Study | Type of Health Care Facility in Which Study Was Conducted | Age Group of Population Studied, y | No. of Persons Eligible for HIV Screeninga | No. of Persons Offered HIV Test on Opt-Out Basis | No. of Persons Who Accepted HIV Test | No. of Persons Who Tested Positive for HIV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anim11 (2013) | January through April 2010 | Dayton, Ohio | Primary care teaching clinic | ≤64 | Not reported | 272 | 46 | 0 |

| Buzi12 (2016) | January 2011 through December 2014 | Houston, Texas | Family planning and primary care clinics | 13-23 | Not reported | 39 698 | 34 299 | 88 |

| Crumby13 (2016) | June 2012 through April 2014 | Houston, Texas | Community health center | ≥13 | 22 658 | 10 904 | 9909 | Not reported |

| Cunningham14 (2009) | July 2007 through March 2008 | Bronx, New York | Community health center | ≥18 | 319 | 300 | 105 | 0 |

| Gardner15 (2012) | June 2010 through June 2011 | Providence, Rhode Island | Tuberculosis clinic | >14 | 939 | 821 | 791 | 1 |

| Harmon16 (2014) | February through March 2012 | Henderson, North Carolina | Primary care clinic | ≥18 | 138 | 138 | 100 | 0 |

| Hemranjani17 (2010) | March through June 2007 | Las Vegas, Nevada | Outpatient clinic | ≥13 | Not reported | 742 | 316 | Not reported |

| Kinsler18 (2013) | Not reported | Los Angeles County, California | Outpatient clinic | 18-64 | Not reported | 220 | 170 | Not reported |

| Leonard19 (2010) | January through May 2008 | Baltimore, Maryland | General adolescent medicine clinic | 13-21 | 217 | 116 | 55 | Not reported |

| Mahajan20 (2016) | January through August 2010 | Los Angeles, California | Ambulatory care clinics | ≥18 | Not reported | 220 | 170 | Not reported |

| Myers21 (2009) | March 2007 through March 2008 | North Carolina, South Carolina, Mississippi | Community health center | 13-64 | 58 619 | 16 148 | 10 769 | 17 |

| Nunn22 (2016) | January 2012 through August 2014 | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | Community health center | ≥13 | 23 317 | 13 827 | 5878 | 13 |

| Rodriguez23 (2016) | January 2011 through December 2013 | Bronx and Queens, New York | Health centers (and community practice sites and school-based health clinics) | 13-64 | 100 369 | 79 649 | 49 646 | 55 |

| Weis24 (2009) | December 2006 through July 2007 | Aiken County, South Carolina | Community health center | ≥13 | Not reported | 985 | 574 | 0 |

| Total | 206 576b | 164 040 | 112 828 | 174c |

aNumber of eligible persons refers to persons who visited non–emergency department outpatient facilities for purposes other than receiving an HIV test and who should be screened for HIV. In 2006, the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended routinely screening persons aged 13-64 in all health care settings, unless the documented prevalence of undiagnosed HIV in the area was <0.1%.2

bThe total number includes only the studies that reported data on the number of persons eligible for HIV screening.

cThe total number includes only the studies that reported data on the number of persons who tested positive for HIV.

Four studies were conducted in the northeastern region of the United States,14,15,22,23 1 study in the Midwest,11 6 studies in the South,12,13,16,19,21,24 and 3 studies in the West.17,18,20 Thirteen studies were conducted at community health centers, ambulatory care clinics, or primary care centers,11-14,16-24 and 1 study was conducted in a tuberculosis clinic.15 All studies were conducted among populations aged ≥13 years, and 2 studies reported data among adolescents or young adults (aged 13-23 years).12,19

Of the 14 studies, 8 studies reported data on the number of persons in the study who were eligible for HIV screening.13-16,19,21-23 Among these 8 studies, the percentage of persons who were offered an HIV test on an opt-out basis varied from 27.5% (95% CI, 27.2%-27.9%; 16 148 of 58 619)21 to 100.0% (95% CI, 97.4%-100.0%; 138 of 138).16 The results of the meta-analysis from these 8 studies showed that, overall, a weighted 71.4% (95% CI, 53.9%-89.0%) of the persons eligible for HIV screening were offered an HIV test on an opt-out basis (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage of persons who were offered an HIV test on an opt-out basis in an outpatient setting in the United States, 2006-2018. Data based on 8 of 14 studies included in a systematic review; 6 studies did not have the data needed to calculate a percentage. “Weight, %” refers to weights derived from random-effects analysis. The dashed line indicates the average percentage across all studies. The diamond represents the 95% confidence interval of the average estimate (based on the random model).

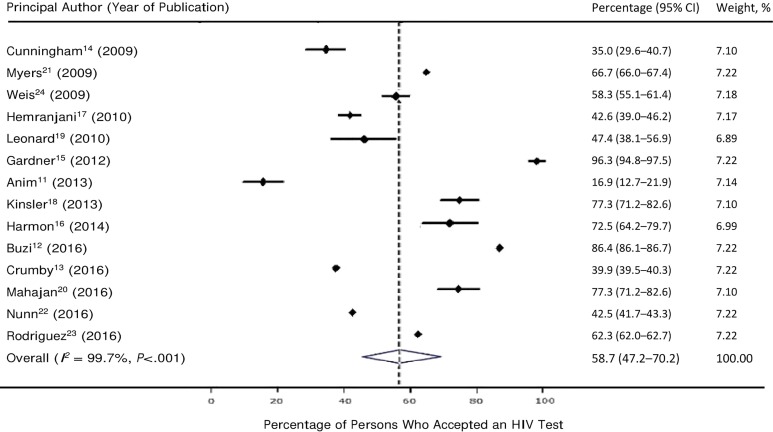

All 14 studies reported data on the number of persons who accepted HIV testing among those who were offered testing. The percentage of persons who accepted HIV testing ranged from 16.9% (95% CI, 12.7%-21.9%; 46 of 272)11 to 96.3% (95% CI, 94.8%-97.5%; 791 of 821).15 Based on a meta-analysis of the 14 studies, a weighted 58.7% (95% CI, 47.2%-70.2%) of persons offered HIV screening accepted testing (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Percentage of persons who accepted an HIV test on an opt-out basis in an outpatient setting in the United States, based on 14 studies in a systematic review, 2006-2018. Data based on all 14 studies included in a systematic review. “Weight, %” refers to weights derived from random-effects analysis. The dashed line indicates the average percentage across all studies. The diamond represents the 95% confidence interval of the average estimate (based on the random model).

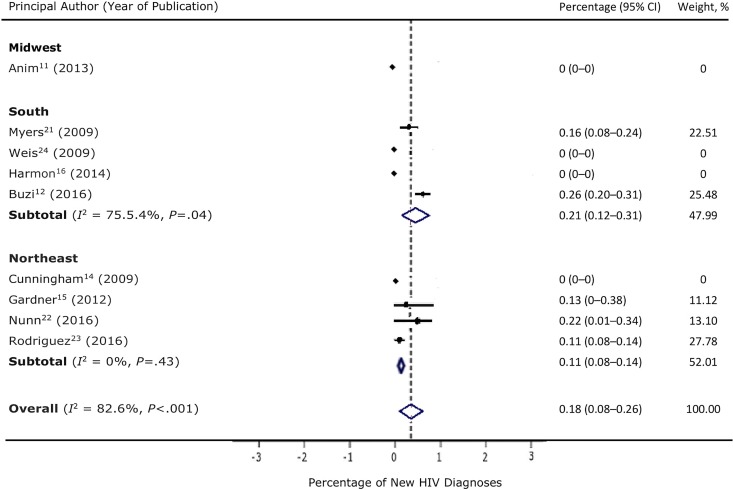

Of the 14 studies, 9 reported data on new HIV diagnoses.11,12,14-16,21-24 A meta-analysis of these 9 studies found that a weighted 0.18% (95% CI, 0.08%-0.26%) of persons tested were found to have a new HIV diagnosis (Figure 4). The study that reported the highest percentage (0.26%; 0.20%-0.31%; 88 of 34 299) of new HIV infections was conducted among adolescents and young adults aged 13-23, and most of the persons with positive HIV test results (73 of 88) were African American.12

Figure 4.

Percentage of new HIV diagnoses among persons who were offered and accepted an HIV test on an opt-out basis in an outpatient setting in the United States, by region, 2006-2018. Data based on 9 of 14 studies in a systematic review; 5 studies did not report data on number of new diagnoses. “Weight, %” refers to weights derived from random-effects analysis. Arrows indicate that the upper confidence interval (CI) cannot be plotted in the space provided. The dashed line indicates the average percentage across all studies. The diamond represents the 95% CI of the average estimate (based on the random model).

We observed high levels of heterogeneity in the percentage of persons offered an HIV test (I 2 = 99.8%, χ2 = 61 579.82, P < .001), the percentage of persons who accepted an HIV test (I 2 = 99.7%, χ2 = 40 580.80, P < .001), and the percentage of new HIV diagnoses (I 2 = 82.6%, χ2 = 42.92, P < .001). The heterogeneity in the percentage of new HIV diagnoses decreased after we conducted a subgroup analysis by region: I 2 was 75.5% in the South and 0% in the Northeast. In the subgroup analysis, studies that were conducted in the southern United States had the highest percentage of newly diagnosed HIV infections (0.21%).

Of the 14 studies, 6 reported reasons for opting out of HIV screening.11,14-16,22,24 Patients’ most frequently cited reason for opting out was that they perceived their risk of having HIV as low.11,14-16,22,24 This reason was followed by having had a previous HIV test,14,16,22 not having enough time for testing or waiting for test results (perception that the test will take a long time),16,22 privacy concerns,16,22 fear of needles,22 not expecting an HIV test,22 cost of the test,11 and not wanting to know their HIV status.24

The quality assessment showed that all studies had good quality (score of 6 or 7 of 7). The funnel plots and Egger symmetry tests showed lack of publication bias among the studies that reported data on the number of persons who were offered an HIV test (Egger’s bias = –25.81, P = .49), the number of persons who accepted HIV testing (Egger’s bias = –20.14, P = .24), and the number of new HIV diagnoses (Egger’s bias = –0.20, P = .70). The funnel plots based on these studies looked symmetrical.

Discussion

CDC has called for the normalization of HIV testing in all health care settings.2 Studies show that health care providers still routinely conduct risk-based testing rather than opt-out HIV testing.19,25-27 A shortage of health care resources,28-30 lack of time,28,31 and lack of knowledge among health care providers about CDC’s updated recommendations31 are some of the barriers to implementing opt-out HIV screening. The wide range in the percentage of persons offered HIV testing (16.9%-96.3%) among the studies we examined could be due to differences in the willingness of health care providers to implement the opt-out strategy, differences in the electronic medical record process,13 or the perception among health care providers that the area in which they practice is an area of low HIV risk. In the studies analyzed in our review that described the implementation process,12,13,15-17,19,21-23 implementation of the opt-out HIV screening strategy was usually accompanied by a health system modification. Some health care facilities in our review modified their existing systems through changes in policy or leadership, modified their existing electronic medical records system, conducted staff training, displayed posters about the screening approach, and conducted continuous quality monitoring. Moreover, strategies that were not reported in the studies, but that have been proposed to increase the proportion of health professionals informing patients about opt-out HIV screening in health care settings, include designation of personnel to serve as organizational champions for expanding opt-out screening strategies31 and the use of electronic reminders.29,31-33 Therefore, support from administration, adoption of necessary health care infrastructure for implementation of the strategy, and staff training are key to the implementation and acceptance of an opt-out screening strategy.

Overall acceptance of opt-out HIV screening was higher in the outpatient settings analyzed in our review (58.7%) than in the emergency departments analyzed in a previous systematic review (44%).7 In our analysis, acceptance of opt-out screening varied among studies. Studies that reported a low percentage of persons accepting a test (16.9%, 35.0%)11,14 did not report any health system modification or staff training. Therefore, the low percentage could be due to ineffective implementation strategies. Moreover, the study with the lowest acceptance percentage11 was conducted among a low-income, medically indigent, uninsured population, and patients in that study had to pay for the test. The differences in receipt of testing could also be due to patient-related factors. For example, in 1 study conducted in 6 community health centers serving populations at risk from March 2007 through March 2008, after CDC released its new guidelines, the percentage of persons accepting an HIV test was higher among African American and Latino patients (compared with non-Hispanic white patients) and young adults (compared with adults aged ≥55).21 Health facility- or community-specific factors may also explain differences in the percentages of offering and accepting opt-out HIV screening. Further study is required to identify these factors.

The weighted estimate of the prevalence of new HIV diagnoses derived from our meta-analysis (0.18%) exceeded the prevalence of undiagnosed infections (0.1%) at which health care providers are recommended by CDC to initiate routine opt-out screening. Although the actual overall prevalence of undiagnosed infection could be lower, depending on the risk among those who refused the test, this result suggests that outpatient settings are settings in which an opt-out HIV screening approach should be integrated into routine medical care. The studies with no new HIV diagnoses had small sample sizes (46 to 574 participants). Increasing the sample size would likely have led to the identification of new HIV diagnoses. The difference in the proportion of tests that identified new HIV diagnoses among the studies could also be due to the difference in the prevalence of HIV infection in the study locations. Therefore, the studies indicating no new HIV infections do not rule out the possible need for opt-out HIV screening in these health care facilities.

Our review also assessed patient-related reasons for refusal of opt-out HIV screening. The most commonly cited reason was low perceived risk. Conducting campaigns to increase awareness of HIV risk factors and increasing the visibility of educational materials in waiting areas and examination rooms could improve awareness of risk.16,24 Behavioral assessments can also influence the perception of vulnerability to HIV infection.34 Another reason for refusal was having had a previous HIV test. CDC recommends that health care providers test all persons likely to be at high risk for HIV infection at least annually and repeat screening of persons not likely to be at high risk based on clinical judgment.2 Health care providers should be aware of the details of the CDC recommendation and ask patients when their most recent test was performed, if the patient reports a previous HIV test. In addition, providers should be aware that sometimes patients incorrectly report having been previously tested for HIV if their blood was actually tested for something else.14,35

Limitations

Our review had several limitations. First, we found high levels of heterogeneity in the percentages of offering an HIV test, accepting a test, and detecting new HIV diagnoses among the studies analyzed. The heterogeneity in the percentage of new HIV diagnoses was reduced substantially after conducting a subgroup analysis by region. Other unmeasured reasons (eg, sociodemographic factors, small sample size, population or health system–related factors) might explain the heterogeneity among studies. Therefore, our results should be interpreted cautiously. Second, the primary objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to assess the acceptance of opt-out HIV screening in outpatient settings. Not all studies reported data on the number of persons eligible for HIV testing and the number of new HIV diagnoses. Hence, our results may not reflect the actual overall percentage of persons offered an HIV test on an opt-out basis or the actual percentage of new HIV diagnoses in outpatient settings in the United States. Future studies need to explore these measures.

Conclusions

Our review, to our knowledge, is the first reported meta-analysis of data on the percentage of persons who were offered and accepted opt-out HIV testing in non–emergency department outpatient settings. The rates of offering and accepting an HIV test on an opt-out basis in outpatient settings could be improved by addressing health system and patient-related factors. The percentage of new HIV diagnoses suggests the need for strengthening the implementation of opt-out HIV screening in these settings. Similar to the 90-90-90 National HIV/AIDS Strategy 2020 targets for linkage, retention, and viral suppression,36 working targets for the proportion of persons offered opt-out HIV screening and the proportion that accept an HIV test would be useful for measuring success in opt-out HIV screening.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Barbara M. Sorondo for her assistance with the search strategy.

Authors’ Note: Additional checklist and graphs are available to readers by contacting the corresponding author.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers K01MD013770 and U54MD012393. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

ORCID iD: Merhawi Gebrezgi, BS  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4669-2930

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4669-2930

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS. Basic statistics. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/statistics.html. Accessed February 2, 2019.

- 2. Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Maricopa Integrated Health System. What is opt-out testing? https://www.mihs.org/testaz/benefits-of-hiv-testing/what-is-opt-out-testing. Accessed January 29, 2019.

- 4. US Preventive Services Task Force. USPSTF A and B recommendations. 2017. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/uspstf-a-and-b-recommendations/. Accessed February 5, 2019.

- 5. Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, Hopkins R, Jr, Owens DK; Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee, American College of Physicians. Screening for HIV in health care settings: a guidance statement from the American College of Physicians and HIV Medicine Association. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(2):125–131. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-150-2-200901200-00300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion: routine human immunodeficiency virus screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):401–403. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e318183fbc2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Henriquez-Camacho C, Villafuerte-Gutierrez P, Pérez-Molina JA, Losa J, Gotuzzo E, Cheyne N. Opt-out screening strategy for HIV infection among patients attending emergency departments: systematic review and meta-analysis. HIV Med. 2017;18(6):419–429. doi:10.1111/hiv.12474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. StataCorp. Stata Release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10. The Joanna Briggs Institute. The Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools for use in JBI systematic reviews: checklist for prevalence studies. 2017. http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/critical-appraisal-tools/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Prevalence_Studies2017.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2019.

- 11. Anim M, Markert RJ, Okoye NE, Sabbagh W. HIV screening of patients presenting for routine medical care in a primary care setting. J Prim Care Community Health. 2013;4(1):28–30. doi:10.1177/2150131912448071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buzi RS, Madanay FL, Smith PB. Integrating routine HIV testing into family planning clinics that treat adolescents and young adults. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(suppl 1):130–138. doi:10.1177/00333549161310S115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Crumby NS, Arrezola E, Brown EH, Brazzeal A, Sanchez TH. Experiences implementing a routine HIV screening program in two federally qualified health centers in the southern United States. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(suppl 1):21–29. doi:10.1177/00333549161310S104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cunningham CO, Doran B, DeLuca J, Dyksterhouse R, Asgary R, Sacajiu G. Routine opt-out HIV testing in an urban community health center. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(8):619–623. doi:10.1089/apc.2009.0005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gardner A, Naureckas C, Beckwith C, Losikoff P, Martin C, Carter EJ. Experiences in implementation of routine human immunodeficiency virus testing in a US tuberculosis clinic. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(9):1241–1246. doi:10.5588/ijtld.11.0628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harmon JL, Collins-Ogle M, Bartlett JA, Thompson J, Barroso J. Integrating routine HIV screening into a primary care setting in rural North Carolina. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2014;25(1):70–82. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2013.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hemranjani D, Kornsawad K, Norman A, Nguye C, Lising J, Satya S. Routine HIV screening program in an urban outpatient setting. AIDS Reader. 2010. https://www.theaidsreader.com/articles/routine-hiv-screening-program-urban-outpatient-setting . Accessed April 12, 2019.

- 18. Kinsler JJ, Sayles JN, Cunningham WE, Mahajan A. Preference for physician vs. nurse-initiated opt-out screening on HIV test acceptance. AIDS Care. 2013;25(11):1442–1445. doi:10.1080/09540121.2013.772283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leonard L, Berndtson K, Matson P, Philbin M, Arrington-Sanders R, Ellen JM. How physicians test: clinical practice guidelines and HIV screening practices with adolescent patients. AIDS Educ Prev. 2010;22(6):538–545. doi:10.1521/aeap.2010.22.6.538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mahajan AP, Kinsler JJ, Cunningham WE, et al. Does the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendation of opt-out HIV screening impact the effect of stigma on HIV test acceptance? AIDS Behav. 2016;20(1):107–114. doi:10.1007/s10461-015-1222-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Myers JJ, Modica C, Dufour MS, Bernstein C, McNamara K. Routine rapid HIV screening in six community health centers serving populations at risk. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(12):1269–1274. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1070-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nunn A, Towey C, Chan PA, et al. Routine HIV screening in an urban community health center: results from a geographically focused implementation science program. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(suppl 1):30–40. doi:10.1177/00333549161310S105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rodriguez V, Lester D, Connelly-Flores A, Barsanti FA, Hernandez P. Integrating routine HIV screening in the New York City Community Health Center Collaborative. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(suppl 1):11–20. doi:10.1177/00333549161310S103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weis KE, Liese AD, Hussey J, et al. A routine HIV screening program in a South Carolina community health center in an area of low HIV prevalence. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(4):251–258. doi:10.1089/apc.2008.0167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McNaghten AD, Valverde EE, Blair JM, Johnson CH, Freedman MS, Sullivan PS. Routine HIV testing among providers of HIV care in the United States, 2009. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e51231 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jain C, Wyatt C, Burke R, Sepkowitz K, Begier EM. Knowledge of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 2006 routine HIV testing recommendations among New York City internal medicine residents. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23(3):167–176. doi:10.1089/apc.2008.0130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Minniear TD, Gilmore B, Arnold SR, Flynn PM, Knapp KM, Gaur AH. Implementation of and barriers to routine HIV screening for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1076–1084. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. DeMarco RF, Gallagher D, Bradley-Springer L, Jones SG, Visk J. Recommendations and reality: perceived patient, provider, and policy barriers to implementing routine HIV screening and proposed solutions. Nurs Outlook. 2012;60(2):72–80. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2011.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Leidel S, Wilson S, McConigley R, Boldy D, Girdler S. Health-care providers’ experiences with opt-out HIV testing: a systematic review. AIDS Care. 2015;27(12):1455–1467. doi:10.1080/09540121.2015.1058895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tan K, Black BP. A systematic review of health care provider-perceived barriers and facilitators to routine HIV testing in primary care settings in the southeastern United States. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2018;29(3):357–370. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2017.12.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Johnson CV, Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, VanDerwarker R, Mayer KH. Barriers and facilitators to routine HIV testing: perceptions from Massachusetts community health center personnel. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(11):647–655. doi:10.1089/apc.2011.0180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marcelin JR, Tan EM, Marcelin A, et al. Assessment and improvement of HIV screening rates in a Midwest primary care practice using an electronic clinical decision support system: a quality improvement study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:76 doi:10.1186/s12911-016-0320-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kershaw C, Taylor JL, Horowitz G, et al. Use of an electronic medical record reminder improves HIV screening. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):14 doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2824-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Glasman LR, Skinner D, Bogart LM, et al. Do assessments of HIV risk behaviors change behaviors and prevention intervention efficacy? An experimental examination of the influence of type of assessment and risk perceptions. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49(3):358–370. doi:10.1007/s12160-014-9659-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nunn A, Eng W, Cornwall A, et al. African American patient experiences with a rapid HIV testing program in an urban public clinic. J Natl Med Assoc. 2012;104(1-2):5–13. doi:10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30125-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. The White House Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS Strategy: updated to 2020. 2015. https://www.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/nhas-update.pdf. Accessed July 21, 2017.