Abstract

Aims

Emission of toxic metabolites in guttation droplets of common indoor fungi is not well documented. The aims of this study were (i) to compare mycotoxins in biomass and guttation droplets from indoor fungi from a building following health complaints among occupants, (ii) to identify the most toxic strain and to test if mycotoxins in guttation liquids migrated trough air and (iii) to test if toxigenic Penicillium expansum strains grew on gypsum board.

Methods and Results

Biomass suspensions and guttation droplets from individual fungal colonies representing Aspergillus, Chaetomium, Penicillium, Stachybotrys and Paecilomyces were screened toxic to mammalian cells. The most toxic strain, RcP61 (CBS 145620), was identified as Pen. expansum Link by sequence analysis of the ITS region and a calmodulin gene fragment, and confirmed by the Westerdijk Institute based on ITS and beta‐tubulin sequences. The strain was isolated from a cork liner, was able to grow on gypsum board and to produce toxic substances in biomass extracts and guttation droplets inhibiting proliferation of somatic cells (PK‐15, MNA, FL) in up to 20 000‐fold dilutions. Toxic compounds in biomass extracts and/or guttation droplets were determined by HPLC and LC‐MS. Strain RcP61 produced communesins A, B and D, and chaetoglobosins in guttation droplets (the liquid emitted from them) and biomass extracts. The toxins of the guttation droplets migrated c. 1 cm through air and condensed on a cool surface.

Conclusions

The mycotoxin‐containing guttation liquids emitted by Pen. expansum grown on laboratory medium exhibited airborne migration and were >100 times more toxic in bioassays than guttation droplets produced by indoor isolates of the genera Aspergillus, Chaetomium, Stachybotrys and Paecilomyces.

Significance and Impact of the Study

Toxic exudates produced by Pen. expansum containing communesins A, B and D, and chaetoglobosins were transferable by air. This may represent a novel mechanism of mycotoxin dispersal in indoor environment.

Keywords: Cytotoxicity, fungal contamination, mycotoxins, Penicillium, toxins

Introduction

Penicillium expansum is a ubiquitous filamentous fungus causing the serious postharvest disease known as blue mould in harvested apples, peaches and hazels (Julca et al. 2015). It is known to produce the potent mycotoxins communesins, chaetoglobosins and patulin when growing on fruits (Andersen et al. 2004; Nielsen et al. 2004; Tannous et al. 2016). As Penicillium expansum results in fruit losses and is a public health issue (Tannous et al. 2016), its ecology as a fruit pathogen and its mycotoxin production on fruits have been extensively studied. On artificially contaminated apples, the optimal conditions for growth have been predicted to occur near 25°C, pH 5·1 and at a high water activity (aw) value of 0·99. Growth of Pen. expansum strains occurred between 4–30°C and optimal patulin production was recorded at 16°C (Tannous et al. 2016).

It is likely that any cellulolytic, saprophytic or biodeteriogenic fungi can grow in indoor environment if finding suitable substrate and moisture (Li et al. 2015). Penicillium expansum has been shown to produce cellulolytic enzymes as β‐glucanase, endoglucanases, cellobiohydrolases and β‐glucosidase and has been isolated from surface‐sterilized timber and deteriorating cedar wood in historical buildings (Duncan et al. 2006; Zayne et al. 2009). This indicates that Pen. expansum may be able to colonize indoor building materials in addition to fruits. However, growth of Pen. expansum on modern building materials and toxin production by indoor isolates identified by modern molecular methods as Pen. expansum have not been documented.

Moisture and indoor growth of ascomycetous fungi, considered together, are positively associated with respiratory illness according to studies performed in many geographical regions (Korkalainen et al. 2017; Mendell and Kumagai 2017; Caillaud et al. 2018; Tähtinen et al. 2019). Irrespective of definition, moisture and mould damage are internationally common and are estimated to occur in 18–50% of buildings (Mendell et al. 2011; Norbäck and Miller 2013). Moisture or dampness and mould damage are found in 2·5–26% of Finnish buildings, being most prevalent (12–26%) in public educational buildings and healthcare facilities (Annila et al. 2017).

Growth of filamentous fungi indoor depends on moisture enabling cell division, mycelial growth, sporulation, formation of membrane‐surrounded liquid‐containing organelles (vesicles, vacuoles and peroxisomes), synthesis of secondary metabolites and emission of volatile organic compounds (Kenne et al. 2014; Kistler and Broz 2015; Bennet and Inamdar 2015). Mould odour has been connected to unhealthy indoor air and is a possible indicator of active fungal growth (Mendell and Kumagai 2017). However, no guidelines for unhealthy levels of indoor mould exposure have been defined (Bennet and Inamdar 2015; Hurraß et al. 2016).

Biologically active fungal secondary metabolites may be toxic to the producer organism, transported to the cell surface and liberated to the exterior by membrane‐surrounded organelles like vacuoles and vesicles (Kenne et al. 2014; Kistler and Broz 2015; Bennet and Inamdar 2015). Compared to conidia and hyphal fragments, membrane‐surrounded organelles of indoor fungi have gained little attention and their impact on indoor air quality is not understood yet. Also, occurrence of Pen. expansum isolates in indoor environments has been of less concern compared to other indoor Penicillium species such as Pen. chrysogenum, and the toxigenic Aspergillus species (Nielsen 2003).

In our preliminary study we found that isolates of Pen. expansum are able to produce chaetoglobosins and communesins, which are secreted in membrane‐surrounded vesicles and liberated as liquid exudates (Salo et al. 2015). Recently we showed that indoor Trichoderma strains produce toxic vesicles and guttation droplets containing peptaibols (Castagnoli et al. 2018b). The reported connection between exposure to toxins and weakened immune tolerance (Genius 2010; Tuuminen and Lohi 2019), as well as our preliminary findings aroused our interest in microbial toxigenesis and vesicle formation and guttation in indoor environments. In this study we investigated toxicities in vesicles and exudates from indoor Penicillium and Aspergillus strains properly identified by molecular methods.

Materials and methods

Sampling and microbiological protocols

Rooms in a large, mechanically ventilated office building (200 rooms) associated with severe adverse health effects of several occupants were investigated. The building has a concrete frame, mineral wool and cork board isolation and a tile façade. Office B23 was on the 1st floor, C35 on the 2nd and others on the ground floor of a building erected in 1959–1967 and renovated in 1997–2000. For cultivation, the samples (Table 1) were grown on 2% malt extract agar (35 ml per plate, Ø 9 cm); sealed with gas‐permeable adhesive tape to slow moisture loss during the 2–4 weeks culturing at a relative humidity (RH) of 30–40% and a temperature of 22–24°C.

Table 1.

Moulds from a university office building where several occupants reported severe, building‐related adverse health symptoms

| Taxon found | Offices | Type of sampling |

|---|---|---|

| Acrostalagmus luteoalbus a | A46 | Cork insulationb d |

| Acrostalagmus sp. a | A31b a | Swab |

| Aspergillus calidoustus a | A31b a | Swabb c |

| Aspergillus niger a | A45b a | Swab |

| Aspergillus versicolor a | A31b a, C35 a | Swab, cork, dust |

| Aspergillus westerdijkiae a | C35 a | Dust, mineral wool insulation |

| Chaetomium globosum a | A31b a, A45b a | Swab, fallout |

| Penicillium expansum a | A31b a, A45b a | Swabb b, corkb a, fallout, impactor |

| Penicillium sp. a | A31a a, A34 | Swab |

| Rhizopus sp. b | A34, B23 | Swab |

| Trichoderma sp. a | C35 a | Dust, mineral wool insulation |

Offices associated with building‐related health complaints are marked in italics.

Indicates the sample from which the strains were isolated. aPen. expansum RcP61, bPen. expansum MH6; cAsp. calidoustus MH34; dAcr. luteoalbus P0b8.

Indicates that the majority (>60%) of the isolates/office produced toxic metabolites.

Plates overgrown with Rhizopus may have contained other species.

Fungal isolates of the Aspergillus niger complex, Pen. expansum MH 6, Chaetomium sp. MH52 and Trichoderma sp. were identified by microscopy (Samson et al. 2002), fluorescence emission of biomass suspensions, toxicity profiles in three toxicity assays and comparison to strains identified by DSMZ (Deutche Sammlung für Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen, Braunschweig, Germany), and deposited in the culture collection HAMBI (University of Helsinki, http://www.helsinki.fi/hambi). The reference strains Aspergillus versicolor GAS226, Aspergillus westerdijkiae PP2, Paecilomyces variotii Paec 2 and Pen. expansum SE1 were identified to species level by DSMZ and deposited in the HAMBI culture collection.

Strains Acrostalagmus luteoalbus P0b8, Aspergillus calidoustus MH34, Pen. expansum RcP61 and SE1, as well as Pen. chrysogenum RUK2/3 were identified by sequence analysis of the ITS region (Andersson et al. 2009) and a calmodulin gene fragment (Hong et al. 2006; Pildain et al. 2008). Sequences were deposited in the GenBank Nucleotide database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) under the following accession numbers: Acr. luteoalbus P0b8: KM853014; Asp. calidoustus MH34: KM853016; Pen. expansum RcP61: KP889005, MK201596, Pen. expansum SE1: MK217414, MK201595, Pen. chrysogenum RUK2/3: KM853015, MK217415. These strains were deposited both in the Szeged Microbiology Collection (http://www.szmc.hu) in Hungary and the HAMBI (http://www.helsinki.fi/hambi/collection in Finland.

In addition, the identity of the strain Pen. expansum RcP61 was confirmed by the Westerdijk Institute based on ITS and beta‐tubulin sequences as Pen. expansum Link, and the strain was deposited in the Westerdijk Institute strain collection under the accession number CBS 145620.

Analytical procedures

For initial toxicity screening, a loop (10 μl) containing 10–20 mg biomass (wet weight) of each colony on the primary culture plates was tested for toxicity. The fungal biomass was dispersed into 0·2 ml of ethanol, the vial sealed and incubated in a water bath for 10 min at 60 °C. The obtained ethanolic lysates were used to expose porcine spermatozoa (obtained from an artificial insemination station) and kidney tubular epithelial cells (PK‐15). The lysate was considered toxic when 2·5 vol% (boar sperm) or 5 vol% (PK‐15) of the lysate inhibited target cell functions: motility (sperm, within 30 min or 1 day) and proliferation (PK‐15, 2 days) (Castagnoli et al. 2018a). The colonies that displayed toxicity were streaked pure and identified to genus or species level.

Exudate droplets harvested from mycelial surfaces with micropipettes and diluted (step = 2) in ethanol were incubated at 60 °C for 10 min and then serially diluted (step = 2) for toxicity testing. The in vitro toxicity test was performed using porcine cells (sperms, somatic cell lines) as indicators according to Bencsik et al. (2014) and Ajao et al. (2015). Fluorescence emission of the fungal secondary metabolites was photographed and illuminated at 360 nm. Mycotoxins were identified using LC‐MS methods (Mikkola et al. 2012; Mikkola et al. 2015).

Toxicity tests of ethanol‐soluble substances extracted from plate‐grown biomass and the identification of the toxins by LC‐MS were described previously (Mikkola et al. 2012; Mikkola et al. 2015; Castagnoli et al. 2018a).

Other protocols

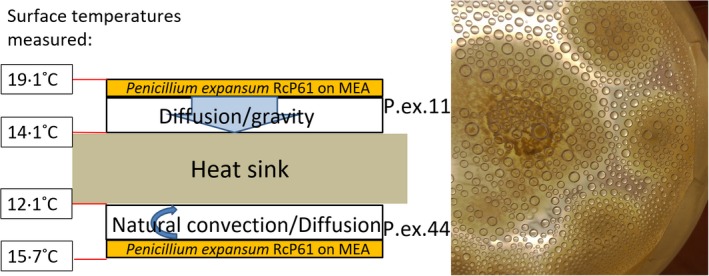

Translocation of fungal metabolites by water vapour from one surface to another was measured using an experimental setup as shown and explained in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Experimental set‐up to study transit of toxicity of guttation droplets through air. Two malt agar plates were inoculated with Penicillium expansum RcP61 and sealed with adhesive tape to prevent drying out. A thermostatically controlled cooled steel plate was sandwiched between the lids of the culture plates, with the lid facing down (top plate) and lid facing up (bottom plate). The measured surface temperatures are shown. The right panel shows the droplets condensing in 14 days on the inner surface of the lid facing up. Condensates on both lids were harvested and analysed using LC‐MS (Fig. 3, Table 4). [Colour figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

To cultivate fungi, moisturized gypsum boards, 100 cm2, thickness of 12 mm, were seeded with spores from a 20‐day‐old plate culture suspended in 0·1 vol% Tween 80. The seeded board was incubated in a steel chamber (12·5 l) and sealed with a glass lid at RH 95% and 20 ± 1 °C. Biomass (2 mg) was scraped with a microscopic slide from the surface of the gypsum liner and dispersed in 40 μl ethanol, incubated at 60 °C for 10 min and then tested for toxicity to PK‐15 cells using inhibition of proliferation as endpoint and applying a fluorometric readout confirmed with microscopic examination as described in Bencsik et al. (2014). Concentrations of conidia (2 μm) and hyphal fragments (larger than 0·1 μm) in biomass lysates and guttation droplets were calculated as the average from 10 microscopic fields by phase contrast microscope (Olympus CKX41 Tokyo Japan) with 400 × magnification.

HPLC‐mass spectrometry analysis

HPLC‐electrospray ionization ion trap mass spectrometry analysis (ESI‐IT‐MS) was performed using an MSD‐Trap‐XCT plus ion trap mass spectrometer equipped with an Agilent ESI source and Agilent 1100 series LC (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, Del., USA) in positive mode with the mass range of m/z 50–2000. The column used was a SunFire C18, 2·1 × 50 mm, 2·5 μm (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Separation of the compounds from exudate droplets and condensates of Pen. expansum RcP61 was performed using an isocratic method of solution A: H2O with 0·1% (v/v) formic acid and B: methanol in a ratio of 40/60 (v/v) for 15 min and a subsequent gradient of 100% B for 30 min at a flow rate of 0·2 ml min−1.

Chemicals and suppliers

Boar semen, 27 × 106 sperms per ml in MRA extender, was purchased from Figen Ltd., Tuomikylä, Finland. The porcine kidney (PK‐15), murine neuroblastoma (MNA) and feline lung (FFL) cells retrieved from EVIRA (Echard 1974; Andersson et al. 2009) were grown in a tissue culture facility as described in detail by Ajao et al. (2015). Malt extract agar media contained 15 g malt extract (Sharlab, Barcelona, Spain) and 12 g agar (Amresco, Dallas, USA) in 500 ml of H2O. Tween 80 was from Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA.

The UV illuminator was from UVA Finland Ltd., Kauniainen. The toxic fungal droplets were photographed using a Dino‐Lite microscopic loupe (Taiwan), magnification 200 ×, connected by USB to a laptop computer.

Results

Toxic droplets emitted by the indoor fungus Penicillium expansum

Indoor dust and materials were collected from offices where occupants had complained of severe, building‐associated health symptoms. Among the biomass suspensions of the 122 colonies from primary culture plates seeded with samples from the affected offices, 63–100% were toxic ex vivo towards porcine sperm cells and in vitro towards somatic PK‐15, FFL and MNA cell lines (Table 1). The fungi corresponding to the toxic biomass suspensions found in the screening procedure were identified as Pen. expansum, Acr. luteoalbus, Asp. calidoustus, Asp. niger, Asp. versicolor, Asp. westerdijkiae, Trichoderma sp. and Chaetomium sp. (Table 1). Guttation droplets produced by the single colonies were screened for toxicity: toxic droplets were produced by Acrostalagmus sp., Trichoderma sp., Chaetomium sp. and the Pen. expansum isolate. For the Pen. expansum RcP61 isolate, concentrations of conidia and toxicity endpoints, as EC100 against PK‐15 cells, between biomass lysate and guttation liquid were compared. Biomass lysate and guttation liquid contained 2 × 107 and 1 × 104 conidia per ml, respectively, the toxicity titres were 160 and 640 respectively. The guttation droplets containing 1000 times less conidia were more toxic than the biomass lysate. Particles classified as hyphal fragments were detected in the biomass dispersal at an estimated concentration below 104 particles per ml. Hyphal fragments were not detected in the guttation liquid (<1 particle in 10 microscopic fields). This indicated that the liquid of the guttation droplet contained toxic substances.

Toxin‐producing Pen. expansum grew from cork insulation boards sampled from holes bored inside the walls of rooms and settled dust from the offices named A31a, A31b, A45b (Table 1) sharing the health problem and the building history. A marked finding was that the colonies of Pen. expansum on plates seeded from samples from the offices associated with serious health concerns extruded amber‐coloured guttation droplets of viscous liquid from the mycelium. The droplets emitted blue fluorescence under UV light.

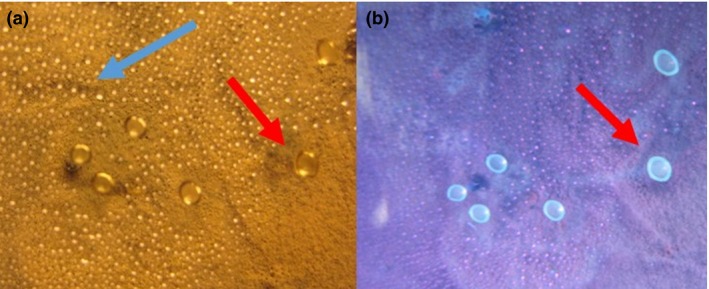

These droplets emitting blue fluorescence were collected from surfaces of the cultured biomass and from the lids of the Petri dishes (Fig. 2). Interestingly the droplets proved to be highly toxic to porcine spermatozoa as well as PK‐15, FFL and MNA cells. A pooled vesicle harvest (dry weight content of 8–9 mg ml−1) was cytotoxic towards each of the three somatic cells up to dilutions of 5000–20 000‐fold (Table 2). Motility of spermatozoa was lost by exposure to approximately 1 μl of the vesicle liquid of 50% of 27 × 106 spermatozoa within 1 h, indicating that the vesicles contained compounds exerting immediate toxic action.

Figure 2.

Photographs of condensates on the lid of a Petri dish containing a 4‐week‐old culture of Penicillium expansum RcP61 inspected under visible light (a) and UV‐light (b). Droplets emitting blue fluorescence (red arrows) were toxic in >100× dilutions compared with the non‐fluorescent droplets (blue arrow, panel a) to boar sperm and porcine kidney cells PK‐15. [Colour figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Table 2.

Mammalian cell toxicities of vesicles emitted by indoor moulds isolated from offices listed in Table 1, associated with severe building‐related ill health of the occupants, and of reference substances

| Isolate and culture age | Indicator cell and exposure time | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porcine sperm cell, 1 h | Porcine kidney, PK15, 2 days | Feline lung, FFL, 2 days | Murine neural, MNA 2 days | |

| Toxicity end‐point | ||||

| Motility inhibition | Inhibition of proliferation | |||

| Penicillium expansum RcP61a vesicle | Highest dilution causing maximal toxic effect, × | |||

| 1000× | ≥20 480× | ≥10 240× | 5120× | |

| Exposure concentration | ||||

| EC50 μl vesicle liquid ml−1 (EC100, μg dry wt. ml−1)b | ||||

| Pen. expansum RcP61 7 days | 2·5 | 0·08 | 0·08 | 0·16 |

| Pen. expansum RcP61 22 days | 2·5 (21) | 0·04 (≤0·4) | 0·08 (<0·8) | 0·16 (1·6) |

| Pen. expansum RcP61 35 daysa | (42) | (1·6) | (1·6) | (1·6) |

| Chaetomium sp. MH52 22 days | 50 | 25 | ||

| Acrostalagmus luteoalbus POB8 14 days | 50 | 50 | ||

| Aspergillus sp. K20 13 days | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| Asp. calidoustus MH34 14 days | >50 | 50 | >50 | |

| Reference substances | ||||

| Asp. versicolor GAS/226 14 days | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| Asp. westerdijkiae pp2 14 days | >50 | >50 | >50 | >50 |

| Paecilomyces variotii Paec 2 14 days | >50 | >50 | >50 | 5 |

| Pen. chrysogenum RUK2/3 exudate droplets 14 days | (160) | 50 (325) | 50 | 25 |

| Pen. chrysogenum RUK2/3 liquid squeezed from the mycelial biomass 14 daysc | (210) | (210) | ||

| Pen. expansum SE1 | 2 | 0·1 | 0·1 | 2 |

| Stachybotrys sp. HJ5 14 days | >50 | 20 | 20 | |

| Triclosan (mitochondriotoxic reference) | (2) | (8) | (8) | (4) |

Containing 86 μg ml−1 of communesins A, B, D and 480 μg ml−1 of chaetoglobosins.

Numbers in brackets indicate dry weight of the liquid in the vesicle.

22 days grown plate culture containing 4200 μg ml−1 of meleagrin.

Identification of the toxins in guttation droplets produced by Penicillium expansum

Considering the high toxicity of Pen. expansum vesicles towards mammalian cells (Table 2) and the scarcity of information about indoor isolates of this species, guttation droplets were analysed using HPLC‐MS. Guttation droplets produced by indoor isolates from other buildings; Asp. versicolor, Asp. calidoustus, Asp. westerdijkiae, Chaetomium sp., Pae. variotii, Pen. expansum, Pen. chrysogenum and Stachybotrys sp. were analysed for reference. It is evident from Table 2, that the vesicles emitted by Pen. expansum RcP61 contained chaetoglobosins and communesins A, B and D (Table 3). The main mycotoxin identified in the droplet liquid was chaetoglobosin, representing 5·6% of the total ion intensity.

Table 3.

Toxicity and toxins identified from ethanol extracts from biomass of indoor moulds isolated from offices (Table 1) and of reference extracts

| Taxon found | Indicator cell and exposure time | Toxins identified | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porcine sperm cells 1 day | Porcine kidney cells, PK‐15 2 days | Murine neural, MNA 2 days | ||

| Motility inhibition | Inhibition of proliferation | |||

| Exposure concentration EC100, μg dry wt ml−1 | ||||

| Acrostalagmus luteoalbus P0b8 | 10 | 10 | Melinacidins II, III, IV | |

| Asp. calidoustus MH4 | 1 | 1 | Ophiobolins H, K | |

| Aspergillus sp. K20 | 10 | 1 | 5 | Sterigmatocystin |

| Chaetomium sp. MH1 | 10 | 40 | 20 | Chaetoglobosin |

| Pen. expansum RcP61 | 1 | 0·7 | 0·7 | Communesins A, B, D and chaetoglobosin C |

| Pen. expansum MH6 | 1 | 0·8 | 1 | |

| Reference extracts | ||||

| Pen. expansum SE1 | 1 | 1 | 0·5 | Communesins A, B, D and chaetoglobosin C |

| Asp. versicolor SL/3 | 10 | 1 | 5 | Sterigmatocystin, averufin |

| Asp. westerdijkiae pp2 | 5 | 15 | 15 | Stephacidin B, avrainvillamide ochratoxin A |

| Paecilomyces variotii Paec 2 | 5 | 500 | 500 | Viriditoxin |

| Stachybotrys sp. HJ5 | 20 | 5 | 5 | Not tested |

| Penicillium sp. TRP1 | 100a | 500a | 500a | None |

| Trichoderma longibrachiatum DSM768 | 100a | 500a | 500a | Noneb |

Represented the nonspecific upper limit of the assays.

Detection limit 0·01 mg ml−1.

Interestingly, ethanol extracts from the biomass and vesicles of Pen. expansum RcP61 contained the same mycotoxins, chaetoglobosins and communesins A, B and D. Biomass extracts of Asp. sp. K20 and Asp. calidoustus MH34 were very toxic to the cells tested and contained mycotoxins (sterigmatocystin, ophiobolins H and K) (Table 3), but the contents of the guttation vesicles were not toxic to the tested cells (Table 2). Also, the guttation droplets from chaetoglobosin‐producing Chaetomium sp. MH1, and melinacidin‐producing Acr. luteoalbus POB8 exhibited very low toxicities compared to Pen. expansum RcP61 (Table 2).

Mycotoxin‐containing liquids are generated on hyphal surfaces and mobilize into the air

To test whether the toxin contents of Pen. expansum guttation droplets would mobilize from a mouldy surface into the air, we set‐up a system (Figs 1 and 2) where the aerosolization of toxic exudates from a culture plate of Pen. expansum RcP61 was detected across a column of air. To generate natural air convection and to condense the humidity, the lids of the culture plates were set a few degrees cooler than the culture plates themselves (Fig. 1). To distinguish between the toxic droplets’ translocation driven by natural air convection and diffusion driven by gravity, one culture plate was placed with its lid facing upwards and the other with its lid facing downwards.

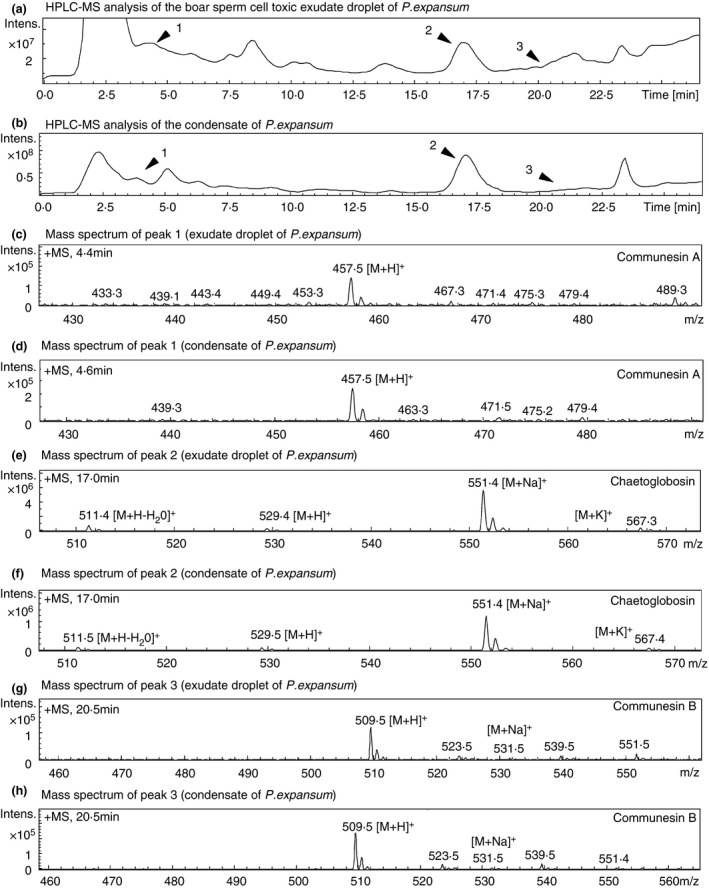

After 8 days, the liquids condensed on the lids were decanted and subjected to mass spectrometric analysis. Boar sperm‐toxic exudate droplets and condensates of Pen. expansum RcP61 upwards (P.ex.44) was analysed using HPLC‐UV and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI‐MS). Peak 1 (4·6 min) of Pen. expansum RcP61 exudate droplet (Fig. 3) contained protonated mass ion [M + H]+ at m/z 457·5 of communesin A. Peak 2 (17·0 min) contained protonated mass ion [M + H]+ at m/z 457·5, sodiated mass ion [M + Na]+ at m/z 529·4, protonated mass ion at m/z 511·5 [M + H‐H20]+ (representing loss of water from protonated mass ion in ESI source) and potassium adduct [M + K]+ at m/z 567·3 of chaetoglobosin. Peak 3 (20·5 min) contained protonated mass ion [M + H]+ at m/z 509·5 and sodiated mass ion [M + Na]+ at m/z 531·5 of communesin B. Corresponding adduct ions of communesin A at m/z 457·5 (Fig. 3d), chaetoglobosin at m/z 511·5, 529·5, 550·4 and 567·4 (Fig. 3f) and communesin B at m/z 509·5 and 531·5 (Fig. 3g) in peaks 1 (4·4 min), 2 (17·0 min) and 3 (20·5 min), respectively, were found from a condensate of Pen. expansum RcP61.

Figure 3.

Comparison of HPLC‐ESI‐MS analyses of the exudates in guttation droplets and vapour condensates of Penicillium expansum RcP61 from Fig. 2 (P.ex.44). HPLC chromatograms of the exudate droplets (a) and of the vapour condensates (b). The peaks 1, 2, 3 in panels a and b were identified as communesin A (peak 1), chaetoglobosin (peak 2) and communesin B (peak 3). Patulin was not measured. Molecular ion [M + H]+ of peak 1 is m/z = 457·5 (c, d), of peak 2 is m/z = 551·4 (e, f) and of peak 3 is m/z 509·5 (g, h).

The total ion chromatograms derived from HPLC‐MS analysis of the exudate droplet (Fig. 3a) and condensate of Pen. expansum RcP61, experimental upwards set‐up (P.ex.44) (Fig. 3a) were similar. Therefore, it was shown that toxic metabolites (chaetoglobosin and communesin A and B) of exudate droplets of Pen. expansum RcP61 are able to transfer by air. Similarly analysed, condensed water collected from experimental downwards set‐up (P.ex.11) also showed that communesin A and chaetoglobosin were transferred by air.

It can be concluded, that the toxic contents of Pen. expansum RcP61 guttation droplets aerosolized and drifted through air (10 mm) both vertically upwards and downwards from the mycelial culture to the respective cooled lids.

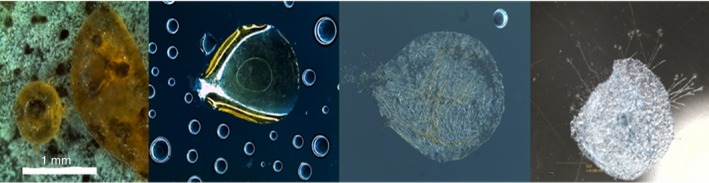

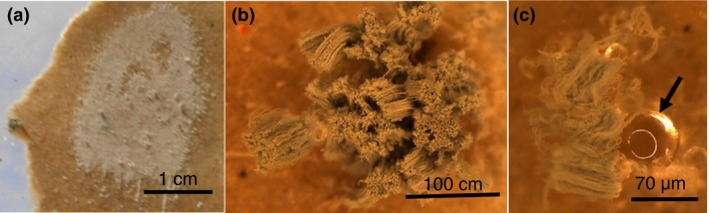

Figure 4 shows micrographs of the guttation droplets, visualizing guttation droplet biomass (first left), trapped on the inner surface of the lid (second left), drying of the droplets (third left) and germination of the conidia (last right) on the lid of the Petri plate.

Figure 4.

Life‐cycle of toxin‐containing vesicles from Penicillium expansum RcP61. From left to right: a large, amber‐coloured vesicle extrudes from the mycelial biomass of Pen. expansum RcP61. The vesicle meets air convection, becomes airborne, hits the polypropylene lid of the culture plate, among tiny droplets of airborne moisture (2nd from left). Air moisture is low, RH 30%, the droplet empties and desiccates (3rd from left). Nine days later, the vesicle has propagated a new generation of Pen. expansum conidiophores (last right). [Colour figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Gypsum board is a common indoor surface material of buildings in Finland. To test if Pen. expansum RcP61 produces droplets while growing on gypsum board, sections of moistened liner‐covered gypsum board were seeded with spore suspension, followed by incubation inside moistened climate chambers sealed with glass lids and rubber seals. After 6 days the gypsum boards appeared visibly mouldy, whereas after 10 days the guttation droplets were visible by naked eye (Fig. 5), having accumulated on the mouldy surface of the gypsum board, independently of whether the board was, or was not, autoclaved before inoculation. Biomass (2 mg) was collected from the surface of the gypsum liner (Fig. 5a) and the biomass lysates were found toxic to the PK‐15 cells at a concentration of 0·5% (v/v).

Figure 5.

Penicillium expansum RcP61 mycelium grown on gypsum board emits guttation droplets. (a) Visible mould growth, 3 weeks, on the gypsum plate; (b) stereo micrographs of the Pen. expansum conidiophores; (c) amber‐coloured guttation droplet (arrow) extruding from the mycelial biomass grown on the gypsum board (a). [Colour figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Toxins in guttation droplets of reference fungi from a culture collection of toxigenic fungi isolated from buildings

The currently studied office building had no major moisture‐damage and was not visibly mouldy, however, the settled dust contained Asp. versicolor‐like strains and Asp. calidoustus. These strains contained highly toxic sterigmatocystin and ophiobolins in their biomass extracts and produced visible guttation droplets (Table 3), but no toxicities were detected in the droplet liquids.

We also used the primary isolates of toxigenic fungi (Pen. chrysogenum RUK2/3 and Pen. expansum SE1, Stachybotrys sp. HJ5, Asp. westerdijkiae PP2, Asp. versicolor GAS226 and Pae. variotii Paec 2) isolated from indoor dusts and building materials, deposited in the HAMBI culture collection for testing toxicity and droplet formation (Table 2). Guttation droplets (dry weight content 6–8 mg ml−1) were produced by isolate Pen. chrysogenum RUK2/3 and contained up to 4 mg ml−1 of meleagrin. Despite the high concentration and substantial amount of the secondary metabolites (meleagrin) of the Pen. chrysogenum RUK2/3 guttation droplets, the toxic effects were modest: the droplets inhibited growth of PK‐15 100–500‐fold less effectively, whereas sperm motility and proliferation of feline pulmonary cells were 5–10‐fold less inhibited (Table 2). The reference strain Pen. expansum SE1 produced chaetoglobosin and communesins A, B and D in the biomass and its guttation droplets were as toxic as those produced by the Pen. expansum strain RcP61. The guttation droplets from other reference strains of toxigenic indoor isolates, viriditoxin‐producing Pae. variotii Paec 2, and Stachybotrys sp. HJ5 producing yet unidentified toxins were 100 times less toxic than the guttation droplets of the Pen. expansum reference strains SE1 and Pen. expansum strain RcP61. Summarizing the results, we established that an indoor strain of Pen. expansum emitted substantial amounts of toxins in guttation droplets, furthermore, the toxins migrated aerially.

Discussion

Penicillium expansum is known to produce some of the most potent mycotoxins within the genus Penicillium, the communesins and chaetoglobosins, which are produced when growing on fruits (Andersen et al. 2004; Nielsen et al. 2004). We report here for the first time that Pen. expansum strains isolated from building material and dust from an office associated with health complaints also produced communesins and chaetoglobosins. Furthermore, we demonstrated that these toxins migrated through the air (Figs 1 and 2, Table 4). Grown on laboratory medium, the in vitro‐ and ex vivo‐measured specific toxicity of Pen. expansum emitted in guttation droplets was 100 times higher than those guttation droplets of toxic indoor isolates of Aspergillus, Chaetomium, Acrostalagmus, Paecilomyces and Stachybotrys, and is, to our knowledge, the highest among the indoor moulds reported to date. We also show that the strain produced guttation droplets when growing on gypsum liner, and that lysates of biomass grown on gypsum liner, containing guttation droplets and conidia were toxic in vitro. The toxicity value was five times lower than the threshold value for toxicity defined for the screening test for microbial biomass lysates.

Table 4.

The airborne transit of mycotoxins contained in exudate droplets of Penicillium expansum RcP61 from the mycelial mass towards a cool surface in the experimental set‐up shown in Fig. 4

| Direction of transfer | Toxin identified | The precursor ions used for identification by MS/MS |

|---|---|---|

| Downwards (P.ex.11) | Chaetoglobosin | 529 [M + H]+, 551 [M + H]+ |

| Communesin A | 509 [M + H]+ | |

| Upwards (P.ex.44) | Chaetoglobosin | 529 [M + H]+, 551 [M + H]+ |

| Communesin A | 509 [M + H]+ | |

| Communesin B | 457 [M + H]+ |

The term guttation has long been known as a virulence mechanism of phytopathogenic and entomopathogenic micro‐organisms (Hutwimmer et al. 2010; Singh and Singh 2013; Singh 2014).

Culture collection isolates of Pen. verrucosum and Pen. nordicum were reported to emit droplets containing 0·01–9 μg ml−1 of ochratoxins A and B, which is 7–10‐fold higher than the concentrations in the mycelial mass of the producer fungus (Gareis and Gareis 2007). For indoor fungi, toxic emission of guttation droplets have been hitherto sparsely reported. Stachybotrys sp. chemotype S culture collection strains originating from various indoor habitats were reported to produce droplets containing 3–5 μg ml−1 satratoxin G and H per ml (Gareis and Gottschalk 2014). Gareis and Gottschalk (2014) first observed that guttation droplets of Stachybotrys chartarum chemotype S contained roridins and satratoxins and produced low (0·2–0·4 ng m−3) but measurable airborne concentrations of satratoxins G and H75.

It is impossible to directly predict in vivo mammalian toxicity based on in vitro toxicity results. In this study we used in vitro and ex vivo toxicity tests to compare toxicities of biomass extracts and guttation droplets produced by selected fungal isolates. Consistently high toxicity was obtained with a continuous lung cell line, FFL, a continuous kidney epithelial cell line, PK‐15, a malignant cell line, MNA, as well as with an ex vivo assay using boar sperm for Pen. expansum strains RcP61 (CBS 145620) and SE1. Using bioassays in combination with chemical analysis we were able to identify the toxins as chaetoglobosins and communesins. The cork liner used as isolation material in the office building may have been the source of Pen. expansum. Penicillium spp. are reported as common contaminants in both moisture‐damaged and non‐damaged indoor spaces (Pasanen et al. 1992; Gravesen et al. 1995; Kaarakainen et al. 2009; Salonen 2009; Adan et al. 2011; Andersen et al. 2011; Nielsen and Frisvad 2011; Samson 2011), but little attention has been paid to Pen. expansum and emissions of chaetoglobosins and communesins in indoor air and their potential association with adverse health effects in moisture damaged buildings.

Using chicken tracheas, Piecková and Wilkins (2004) have demonstrated that indoor Chaetomium sp. produced very potent, ciliostatically active metabolites. Mycotoxins from indoor Chaetomium globosum strains and pure chaetoglobosin A from C. globosum also inhibited sperm motility by a sublethal ciliostatic mechanism, very likely by inhibiting sugar transport affecting glycolytic and mitochondrial energy production (Vicente‐Carrillo et al. 2015; Castagnoli et al. 2017; Castagnoli et al. 2018b). The chaetoglobosin‐containing guttation droplets inhibited sperm motility, possibly indicating ciliostatic activity. Thus, the risk of respiratory toxicity represented by airborne chaetoglobosin shown toxic to the primary lung cell line FFL and exhibiting ciliostatic activity is highly speculative, but cannot be excluded. The risk of airborne respiratory toxicity can be directly evidenced by in vivo experiments exposing laboratory animals to known airborne concentrations of chaetoglobosins and communesisns, which was out of scope for this article.

Chaetoglobosins known as cytochalasins (McMullin et al. 2013) exert their cytotoxicity by capping the growing end of actin microfilaments, thereby destroying the cytoskeleton of mammalian cells (Ueno 1985; Scherlach et al. 2010). Communesins are neurotoxic, insecticidal indole alkaloids (Hayashi et al. 2004; Kerzaon et al. 2009). Chaetoglobosin B was reported to be toxic to human erythrocyte membranes by competitively inhibiting glucose transport activity (Scherlach et al. 2010). Inhibition of glucose transport was also reported for chaetoglobosin A (Nielsen and Frisvad 2011). Thus, it is possible that the observed complete blocking of proliferation of the somatic cells PK‐15, FFL and MNA (Table 2), as well as the motility inhibition of boar sperm by exposure to the Pen. expansum RcP61 vesicle fluid was caused by blocked glucose transport depriving the cells of energy.

This study is, to our knowledge, the first where a Pen. expansum strain, RcP61 (CBS 145620), growing on building material inside the construction in a building with reported health complaints, was shown to produce toxic guttation droplets on laboratory media and on gypsum liner. Toxin concentrations in guttation droplets emitted by Pen. expansum grown on laboratory medium, in the current work, appear 100–1000‐fold higher than previously demonstrated from any fungus.

The weakened immune tolerance reported from urban environments caused by depleted and poor outdoor microbial diversity (Moore 2015; Schuijs et al. 2015; von Hertzen et al. 2015; Haahtela et al. 2015; Adams et al. 2016; Mhuireach et al. 2016; Stein et al. 2016; Li et al. 2018) may be attenuated by exposure to indoor microbes producing toxins inducing loss of tolerance (TILT; Miller 1997; Genius 2010). We were tempted to speculate that the absence of a diverse protective microbiome in combination with exposure to microbial TILT may be a potential factor to contribute to the diverse indoor air‐related health symptoms experienced in mould‐damaged urban buildings.

Results of this study call for continued research on how mycotoxin‐containing guttation droplets can be spread in indoor air. The toxicity and migration of guttation droplets in the air were shown in this study, but their spreading in the rooms needs to be studied in future research.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest declared.

Acknowledgements

The authors warmly thank Riikka Holopainen at the Finnish Food Safety Authority (EVIRA) for providing the somatic cell lines PK‐15, FFL and MNA. The authors thank Prof. Tari Haahtela, Prof. Mirja Salkinoja‐Salonen and Prof. Martti Viljanen for their valuable advice and support during the work. The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Finnish Work Environment Fund by grant #112134, the Academy of Finland grants #253727 and #289161 and the Business Finland (the Finnish Funding Agency for Innovation, grant number 4098/31/2015). LK was supported by the GINOP‐2·3.2‐15‐2016‐00012 grant (Széchenyi 2020 Programme, Hungary) and the János Bolyai Research Scholarship (Hungarian Academy of Sciences).

References

- Adams, R. , Bhangar, S. , Dannemiller, K. , Eisen, J. , Fierer, N. , Gilbert, L. , Green, J. , Linsey, C. et al (2016) Ten questions concerning the microbiomes of buildings. Build Environ 109, 224–234. [Google Scholar]

- Adan, O.C.G. , Huinink, H.P. and Bekker, M. (2011) Water relations of fungi in indoor environments In Fundamentals of Mold Growth in Indoor Environments and Strategies for Healthy Living ed. Adan O.C.F. and Samson R.A. pp. 41–65. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ajao, C. , Andersson, M. , Teplova, V.V. , Nagy, S. , Gahmberg, C.G. , Andersson, L.C. , Hautaniemi, M. , Kakasi, B. et al (2015) Mitochondrial toxicity of triclosan. Toxicol Rep 2, 624–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, B. , Smedsgaard, J. and Frisvad, J.C. (2004) Penicillium expansum: consistent production of patulin, chaetoglobosins and other secondary metabolites in culture and their natural occurrence in fruit products. J Agric Food Chem 52, 2451–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, B. , Frisvad, J.C. , Söndergaard, I. , Tarmussen, I.S. and Larsen, L.S. (2011) Associations between fungal species and water‐damaged building materials. Appl Environ Microbiol 77, 4180–4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, M.A. , Mikkola, R. , Raulio, M. , Kredics, L. , Maijala, P. and Salkinoja‐Salonen, M.S. (2009) Acrebol, a novel toxic peptaibol produced by an Acremonium exuviarum indoor isolate. J Appl Microbiol 106, 909–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annila, P.J. , Hellemaa, M. , Pakkala, T. , Lahdensivu, J. , Suonketo, J. and Pentti, M. (2017) Extent of moisture and mould damage in structures of public buildings. Case Stud Constr Mater 6, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Bencsik, O. , Papp, T. , Berta, M. , Zana, A. , Forgó, P. , Dombi, G. , Andersson, M.A. , Salkinoja‐Salonen, M.S. et al (2014) Ophiobolin A from Bipolaris oryzae perturbs motility and membrane integrities of porcine sperm and induces cell death on mammalian somatic cell lines. Toxins 6, 2857–2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennet, J. and Inamdar, A. (2015) Are some volatile organic compound (VOCs) mycotoxins? Toxins 7, 3785–3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caillaud, D. , Leynaert, B. , Keirsbulck, M. and Nadif, R. (2018) Indoor mould exposure, asthma and rhinitis: findings from systematic reviews and recent longitudinal studies ‐ a review. Eur Respir Rev 27, 170–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagnoli, E. , Andersson, M.A. , Mikkola, R. , Kredics, L. , Marik, T. , Kurnitski, J. and Salonen, H. (2017). Indoor Chaetomium‐like isolates: resistance to chemichals, fluorescence and mycotoxin production. Conference paper: Sisäilmastoseminaari Volume: SYI report 35 March 2017 Helsinki, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Castagnoli, E. , Marik, T. , Mikkola, R. , Kredics, L. , Andersson, M.A. , Salonen, H. and Kurnitski, J. (2018a) Indoor Trichoderma strains emitting peptaibols in guttation droplets. J Appl Microbiol 125, 1408–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagnoli, E. , Salo, J. , Toivonen, M.S. , Marik, T. , Mikkola, R. , Kredics, L. , Vicente‐Carrillo, A. , Nagy, S. et al (2018b) An evaluation of boar spermatozoa as a biosensor for the detection of sublethal and lethal toxicity. Toxins 10, 463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, S. , Farrell, R. , Thwaites, J. , Held, B. , Arenz, B. , Jurgens, A. and Blanchette, R. (2006) Endoglucanase‐producing fungi isolated from Cape Evans historic expedition hut on Ross Island, Antarctica. Environ Microbiol 8, 1212–1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echard, G. (1974) Chromosomal banding patterns and karyotype evolution in three pig kidney cell strains (PK‐15, F and RP). Chromosoma 45, 133–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gareis, M. and Gareis, E.‐M. (2007) Guttation droplets of Penicillium nordicum and Penicillium verrucosum contain high concentrations of the mycotoxins ochratoxin A and B. Mycopathologia 163, 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gareis, M. and Gottschalk, C. (2014) Stachybotrys spp. and the guttation phenomenon. Mycotox Res 30, 151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genius, S.J. (2010) Sensitivity‐related illness: the escalating pandemic of allergy, food intolerance and chemical sensitivity. Sci Total Environ 408, 6047–6061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravesen, S. , Frisvad, J.C. and Samson, R.A. (1995) Important moulds in damp buildings In Microfungi ed. Gravesen S., Frisvad J.C. and Samson R.A. pp. 15–26. København: Munksgaard. [Google Scholar]

- Haahtela, T. , Laatikainen, T. , Alenius, H. , Auvinen, P. , Fyhrquist, N. , Hanski, I. , von Hertzen, L. , Jousilahti, P. et al (2015) Hunt for the origin of allergy ‐ comparing the Finnish and Russian Karelia. Clin Exp Allergy 45, 891–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, H. , Matsumoto, H. and Ariyama, K. (2004) New insecticidal compounds, communesins C, D and E. from Penicillium expansum Link MK‐57. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 68, 753–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Hertzen, L. , Beutler, B. , Bienenstock, J. , Blaser, M. , Cani, P.D. , Eriksson, J. , Färkkilä, M. , Haahtela, T. et al (2015) Helsinki alert of biodiversity and health. Ann Med 47, 218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.B. , Cho, H.S. , Shin, H.D. and Frisvad, J.C. (2006) Novel Neosartorya species isolated from soil in Korea. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 56, 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurraß, J. , Heinzow, B. , Aurbach, U. , Bergmann, K.‐C. , Bufe, A. , Buzina, W. , Cornely, O. , Engelhart, S. et al. (2016) Medical diagnostics for indoor mold exposure. Int J Hyg Environ Health 220, 305–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutwimmer, S. , Wang, H. and Strasser, H. (2010) Formation of exudate droplets by Metarhizium anisopliae and the presence of destruxins. Mycologia 102, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julca, I. , Droby, S. , Sela, N. , Marcet‐Houben, M. and Gabaldon, T. (2015) Contrasting genomic diversity in two closely related postharvest pahogens: Penicillium digitatum and Penicillium expansum . Genome Biol Evol 8, 218–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaarakainen, P. , Rintala, H. , Vepsäläinen, A. , Hyvärinen, A. , Nevalainen, A. and Meklin, T. (2009) Microbial content of house dust samples determined with qPCR. Sci Total Environ 407, 4673–4680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenne, G.J. , Chakraborty, P. and Chanda, A. (2014) Modeling toxisome protrusions in filamentous fungi. JSM Environ Sci Ecol 2, 1010–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Kerzaon, I. , Pouchus, Y.F. , Monteau, F. , Le Bizec, B. , Nourisson, M.‐R. , Biard, J.‐F. and Grovel, O. (2009) Structural investigation and elucidation of new communesins from marine‐derived Penicillium expansum Link by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Rap Commun Mass Spectrom 23, 3928–3938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistler, H. and Broz, K. (2015) Cellular compartmentalization of secondary metabolism. Front Microbiol 6, 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkalainen, M. , Naarala, J. , Kirjavainen, P. , Koistinen, A. , Hyvärinen, A. , Komulainen, H. and Viluksela, M. (2017) Synergistic proinflammatory interactions of microbial toxins and structural components characteristic to moisture‐damaged buildings. Indoor Air 27, 13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.‐W. , Johanning, E. and Yang, C. (2015) In Airborne fungi and mycotoxins Chapter 3.2.5. In Manual of Environmental Microbiology (4th edn) ed. Yates M., Nakatsu C., Miller R. and Pillai S. Washington DC: ASM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G. , Sunc, G.‐X. , Rena, Y. , Luo, X.‐S. and Zhua, Y.‐G. (2018) Urban soil and human health: a review. Eur J Soil Sci 69, 196–215. [Google Scholar]

- McMullin, D.R. , Sumarah, M.W. and Miller, J.D. (2013) Chaetoglobosins and azaphilones produced by Canadian strains of Chaetomium globosum isolated from the indoor environment. Mycotox Res 29, 47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendell, M.J. and Kumagai, K. (2017) Observation‐based metrics for residential dampness and mold with dose–response relationships to health. Indoor Air 27, 506–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendell, M.J. , Mirer, A.G. , Cheung, K. , Tong, M. and Douwes, J. (2011) Respiratory and allergic health effects of dampness, mold, and dampness‐related agents: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Environ Health Perspect 119, 748–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mhuireach, G. , Johnson, B.R. , Adam, E. , Altrichter, A.E. , Ladau, J. , Meadow, J.F. , Pollard, K.S. and Green, J.L. (2016) Urban greenness influences airborne bacterial community composition. Sci Total Environ 571, 680–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkola, R. , Andersson, M.A. , Kredics, L. , Grigoriev, P. , Sundell, N. and Salkinoja‐Salonen, M. (2012) 20‐Residue and 11‐residue peptaibols from the fungus Trichoderma longibrachiatum are synergistic in forming Na+/K+ permeant channels and in adverse action towards mammalian cells. FEBS J 279, 4172–4190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkola, R. , Andersson, M.A. , Hautaniemi, M. and Salkinoja‐Salonen, M. (2015) Toxic indole alkaloids avrainvillamide and stephacidin B produced by a biocide tolerant indoor mold Aspergillus westerdijkiae . Toxicon 99, 58–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C.S. (1997) Toxicant induced loss of tolerance ‐ an emerging theory of disease? Environ Health Perspect 105, S445–S453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, M. (2015) Do airborne biogenic chemicals interact with the PI3K/Akt/mTOR cell signalling pathway to benefit human health and wellbeing in rural and coastal environments. Environ Res 140, 65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, K.F. (2003) Mycotoxin production of indoor molds. Fungal Genet Biol 39, 103–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, K.F. and Frisvad, J.C. (2011) Mycotoxins on building material In Fundamentals of Mold Growth. Indoor Environments and Strategies for Healthy Living ed. Adan O.C.F. and Samson R.A. pp. 245–275. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, K.F. , Nielsen, P.A. , Holm, G. and Uttrup, L.P. (2004) Mold growth on building materials under low water activities influence of humidity and temperature on fungal growth and secondary metabolites. Int Biodeter Biodegr 54, 325–336. [Google Scholar]

- Norbäck, D. and Miller, J.D. (2013) Building‐related illnesses and mold related conditions In Asthma in the Workplace, (4th edn) ed. Bernstein D.I., Malo J.‐L., Chan Yeung M. and Bernstein L. pp. 406–417. New York: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Pasanen, A.L. , Heinonen‐Tanski, H. and Kalliokoski, P. (1992) Fungal microcolonies on indoor surfaces – an explanation for the base‐level fungal spore counts in indoor air. Atmos Environ 26B, 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Piecková, E. and Wilkins, K. (2004) Airway toxicity of house dust and its fungal composition. Ann Agric Environ Med 11, 67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pildain, M.B. , Frisvad, J.C. , Vaamonde, G. and Cabral, D. (2008) Two novel aflatoxin‐producing Aspergillus species from Argentinean peanuts. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 58, 725–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salo, J. , Andersson, M.A. , Mikkola, R. , Kredics, L. , Viljanen, M. and Salkinoja‐Salonen, M. (2015) Vapor as a carrier of toxicity in a health troubled building Proceedings of Healthy Buildings 2015 – Europe (ISIAQ International), Eindhoven, The Netherlands, Paper ID526, 8 pp E.1 Sources & Exposure, Source control. [Google Scholar]

- Salonen, H. (2009) Indoor air contaminants in office buildings. (Dissertation). Finnish Institute of Occupational Health; People and Work Research Report 87, 222 p. [Google Scholar]

- Samson, R.A. (2011) Ecology and general characteristics of indoor fungi In Fundamentals of Mold Growth in Indoor Environments and Strategies for Healthy Living ed. Adan O.C.F. and Samson R.A. pp. 101–116. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Samson, R.A. , Hoekstra, E.S. , Frisvad, J.C. and Filtenborg, O. (2002) Eds. Introduction to food and air‐borne fungi (6th edn). Utrecht: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures. [Google Scholar]

- Scherlach, K. , Boettger, D. , Remme, N. and Hertweck, C. (2010) The chemistry and biology of cytochalasans. Nat Prod Rep 27, 869–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuijs, M.J. , Willart, M.A. , Vergote, K. , Gras, D. , Deswarte, K. , Ege, M.J. , Madeira, F.B. , Beyaert, R. et al. (2015) Farm dust and endotoxin protect against allergy through A20 induction in lung epithelial cells. Science 4, 1106–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S. (2014) Guttation: quantification, microbiology and implications for phytopathology In Progress in Botany 75, ed. Lüttge U., Beyschlag W. and Cushman J. pp. 187–214. Berlin: Springer‐Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S. and Singh, T.N. (2013) Guttation 1: Chemistry, crop husbandry and molecular farming. Phytochem Rev 12, 147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, M.M. , Cara, B.S. , Hrusch, L. , Justyna Gozdz, J. , Igartua, C. , Vadim Pivniouk, V. , Murray, S. , Julie, G. et al (2016) Innate immunity and asthma risk in Amish and Hutterite farm children. New Engl J Med 375, 411–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tähtinen, K. , Lappalainen, S. , Karvala, K. , Lahtinen, M. and Salonen, H. (2019) Probability of abnormal indoor air exposure categories compared with occupants’ symptoms, health information, and psychosocial work environment. Appl Sci 9, 99. [Google Scholar]

- Tannous, J. , Atoui, A. , Khoury, A. , Francis, Z. , Oswald, I. , Puel, O. and Lteif, R. (2016) A study on the physicochemical parameters for Penicillium expansum growth and patulin production: effect of temperature, Ph, and water activity. Food Sci Nutr 4, 611–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuuminen, T. and Lohi, J. (2019) Immunological and toxicological effects of bad indoor air to cause dampness and mold hypersensitivity syndrome. Allergy Immunol 2, 190–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ueno, Y. (1985) Toxicology of mycotoxins. Crit Rev Toxicol 14, 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente‐Carrillo, A. , Edebert, I. , Garside, H. , Cotgreave, I. , Rigler, R. , Loitto, V. , Magnusson, K.E. and Rodríguez‐Martínez, H. (2015) Boar spermatozoa successfully predict mitochondrial modes of toxicity: implications for drug toxicity testing and the 3R principles. Toxicol In Vitro 29, 582–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayne, M. , Mortabit, D. , Mostakin, M. , Iraqui, M. , Haggoud, A. , Haggoud, M. , Ettayebi, S. and Koraichi, I. (2009) Cellulolytic potential of fungi in wood degradation from an old house at the Medina of Fez. Ann Microbiol 59, 699–704. [Google Scholar]