Abstract

Background: The Zika virus (ZIKV) caused a large outbreak in the Americas leading to the declaration of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern in February 2016. A causal relation between infection and adverse congenital outcomes such as microcephaly was declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) informed by a systematic review structured according to a framework of ten dimensions of causality, based on the work of Bradford Hill. Subsequently, the evidence has continued to accumulate, which we incorporate in regular updates of the original work, rendering it a living systematic review.

Methods: We present an update of our living systematic review on the causal relation between ZIKV infection and adverse congenital outcomes and between ZIKV and GBS for four dimensions of causality: strength of association, dose-response, specificity, and consistency. We assess the evidence published between January 18, 2017 and July 1, 2019.

Results: We found that the strength of association between ZIKV infection and adverse outcomes from case-control studies differs according to whether exposure to ZIKV is assessed in the mother (OR 3.8, 95% CI: 1.7-8.7, I 2=19.8%) or the foetus/infant (OR 37.4, 95% CI: 11.0-127.1, I 2=0%). In cohort studies, the risk of congenital abnormalities was 3.5 times higher after ZIKV infection (95% CI: 0.9-13.5, I 2=0%). The strength of association between ZIKV infection and GBS was higher in studies that enrolled controls from hospital (OR: 55.8, 95% CI: 17.2-181.7, I 2=0%) than in studies that enrolled controls at random from the same community or household (OR: 2.0, 95% CI: 0.8-5.4, I 2=74.6%). In case-control studies, selection of controls from hospitals could have biased results.

Conclusions: The conclusions that ZIKV infection causes adverse congenital outcomes and GBS are reinforced with the evidence published between January 18, 2017 and July 1, 2019.

Keywords: Zika, Disease outbreaks, arboviruses, causality, Guillain-Barré syndrome, congenital abnormalities

Introduction

The Zika virus (ZIKV), a mosquito-borne flavivirus, caused a large outbreak of infection in humans in the Americas between 2015–2017 ( WHO Zika -Epidemiological Update). Since then, the circulation of ZIKV has decreased substantially in the Americas 1 but ZIKV transmission will likely continue at a lower level 2. Smaller outbreaks have been reported from countries in Africa and Asia, including Angola, India 3, and Singapore 4. Regions with endemic circulation, such as Thailand 5, have the potential for new ZIKV outbreaks with adverse outcomes 6.

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared ZIKV as a cause of adverse congenital outcomes and Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) as early as September 2016 7, informed by a systematic review of evidence structured according to a framework of ten dimensions of causality, based on Bradford Hill ( Table 1) 8. The accumulation of evidence on the adverse clinical outcomes of ZIKV has barely slowed down since the WHO declared the Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on February 1 st, 2016, with approximately 250 research publications on ZIKV appearing every month (see Zika Open Access Project). We updated the systematic review to January 18, 2017 as a living systematic review by introducing automated search methods to produce a high quality, up to date, online summary of research 9 about ZIKV and its clinical consequences, for all the causality dimensions 10.

Table 1. Comparison of the search strategy included study designs and causality dimensions addressed in the different review periods.

The latest and previous versions of this table are available as extended data 16.

| Review | Baseline 8 | Update 1 10 | Update 2 [this review] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Period | <May 30, 2016 | May 30, 2016-January 18, 2017 | >January 18, 2017 -July 01, 2019 |

| Search strategy | “ZIKV” or “Zika” | “ZIKV” or “Zika” | Focussed search strategy (Supplementary

File 2) |

| Study design | Epidemiological studies;

in vivo/

in vitro studies;

surveillance reports |

Epidemiological studies | |

|

Dimensions of the causality

framework based on Bradford Hill * |

•Temporality (cause precedes effect) | ||

| •Biological plausibility of proposed biological

mechanisms |

|||

| •Strength of association | •Strength of association | ||

| •Exclusion of alternative explanations | |||

| •Cessation (reversal of an effect by experimental

removal of, or observed a decline in, the exposure) |

|||

| •Dose-response relationship | •Dose-response relationship | ||

| •Experimental evidence from animal studies | |||

| •Analogous cause-and-effect relationships found in

other diseases |

|||

| •Specificity of the effect | •Specificity of the effect | ||

| •Consistency of findings across different study

types, populations and times |

•Consistency of findings across different

study types, populations and times |

||

* The causality framework is described elsewhere in detail:

Since 2017, understanding about the pathogenesis of how ZIKV causes congenital abnormalities has evolved 11, 12. The quality of diagnostic methods, especially for acute ZIKV infection, has also improved 13– 15. More importantly, understanding of the limitations of diagnostic testing, and the need for interpretation in the context of other flavivirus infections, has developed. Important epidemiological questions about the associations between ZIKV infection and adverse congenital outcomes and GBS remain unanswered, however. Much of the early epidemiological evidence, which relied on surveillance data, was limited in use because of issues with the quality of the reporting and case definitions. The reported strength of association between ZIKV and adverse outcomes has varied in studies of different designs and in different settings. Evidence for a dose-response relationship with higher levels of exposure to ZIKV resulting in more severe outcomes, of clinical findings that are specific to ZIKV infection, or of adverse outcomes caused by different lineages of ZIKV was not found in the earlier systematic reviews.

The objective of this study is to update epidemiological evidence about associations between ZIKV infection and adverse congenital outcomes and between ZIKV and GBS for four dimensions of causality: strength of association, dose-response, specificity, and consistency.

Methods

We performed a living systematic review, which we have described previously 10. This review updates the findings of the previous reviews 8, 10 and will be kept up to date, in accordance with the methods described below. Reporting of the results follows the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Extended data, Supplementary File 1 17) 18.

Focus on epidemiological aspects of causality

This review and subsequent updates will focuse on four dimensions of causality that are examined in epidemiological study designs: strength of association, dose-response relationship and specificity of effects and consistency of association (Extended data, Table 1, Supplementary File 2 17). Evidence for domains of causality that are typically investigated in in vitro and in vivo laboratory studies ( Table 1) was not sought. In the absence of licensed vaccines or treatments for ZIKV infection, we did not search for evidence on the effects of experimental removal of ZIKV.

Eligibility criteria

We considered epidemiological studies that reported original data and assessed ZIKV as the exposure and congenital abnormalities or GBS as the outcomes. We based the exposure and outcome assessment on the definitions used in the publications. We applied the following specific inclusion criteria (Extended data, Supplementary File 2 17):

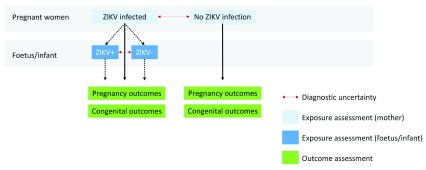

Strength of association: at the individual level, we selected studies that included participants both with and without exposure to ZIKV ( Figure 1), such as cohort studies and case-control studies. At the population level, we included studies that assessed the outcome during the ZIKV outbreak and provided a comparison with pre or post-outbreak incidence of the outcome.

Figure 1. For congenital abnormalities due to ZIKV, exposure assessment in mother-infant pairs can be performed in the mother or the foetus or infant.

The latest and previous versions of this figure are available as extended data 16.

Dose-response relationship: we included studies that assessed the relation between the level of the viral titre or the presence or severity of the symptoms and the occurrence or severity of the outcome.

Specificity of the outcome for ZIKV exposure: we included studies that assessed whether the pathological findings in cases with the outcome are specific for ZIKV infection.

Consistency: we looked at eligible studies to determine the consistency of the relationship between ZIKV exposure and the outcomes across populations, study designs, regions or strains.

Search and information sources

We searched PubMed, Embase, LILACS and databases and websites of defined health agencies (Extended data, Supplementary File 2 16). We included search terms for the exposure, the outcome and specific study designs. We also performed searches of the reference lists of included publications. A detailed search strategy is presented in Supplementary File 2. For this review, the search covered the period from January 19, 2017 to July 1, 2019.

Study selection and extraction

One reviewer screened titles and abstracts of retrieved publications. If retained, the same reviewer screened the full text for inclusion. A second reviewer verified decisions. One reviewer extracted data from included publications into piloted extraction forms in REDCap (version 8.1.8 LTS, Research Electronic Data Capture) 19. A second reviewer verified data entry. Conflicts were resolved by consulting a third reviewer.

Synthesis of evidence

First, we summarised findings for each dimension of causality and for each outcome descriptively. Where available, we calculated unadjusted odds ratios (OR) or risk ratios (RR) and their 95% confidence interval (CI) from published data for unmatched study designs. For matched study designs, we used the effect measure and 95% CI presented by the authors. For publications that presented results for multiple measures of exposure and/or outcome, we compared these results. We applied the standard continuity correction of 0.5 for zero values in any cell in the two-by-two table 20. We used the I² statistic to describe the percentage of variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity for reasons other than chance 21. Quantitative synthesis was performed using R 3.5.1 22. We conducted random effects meta-analyses using the R package metafor (version 2.0-0) 20. Finally, we compared descriptive and quantitative findings from this review period with previous versions of the review 8, 10.

Searching and screening frequency

Daily searches of PubMed, Embase and LILACS are automated and monthly searches are performed manually for other information sources in the first week of the month (Extended data, Supplementary File 2 17), with screening of all retrieved publications on the same day. The search strategy consisted of a combination of free terms and MESH terms that identified the exposure and outcomes (Extended data, Supplementary File 2 17). Searches from multiple sources were combined and automatically deduplicated by an algorithm that was tested against manual deduplication. Unique records enter a central database, and reviewers are notified of new content.

Frequency of results update

The tables and figures presented in this paper will be updated every six months as a new version of this publication. As soon as new studies are included, their basic study characteristics are extracted and provided online https://zika.ispm.unibe.ch/assets/data/pub/causalityMap/.

Duration of maintenance of the living systematic review

We will keep the living systematic review up to date for as long as new relevant data are published and at least until October 31, 2021, the end date of the project funding.

Risk of bias/Certainty of evidence assessment

To assess the risk of bias of cohort studies and case-control studies, we compiled a list of questions in the domains of selection bias, information bias, and confounding, based on the quality appraisal checklist of the United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and literature 23. Two independent reviewers conducted the quality assessment. Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer.

Results

Search results from January 19, 2017 to July 1, 2019 (Update 2)

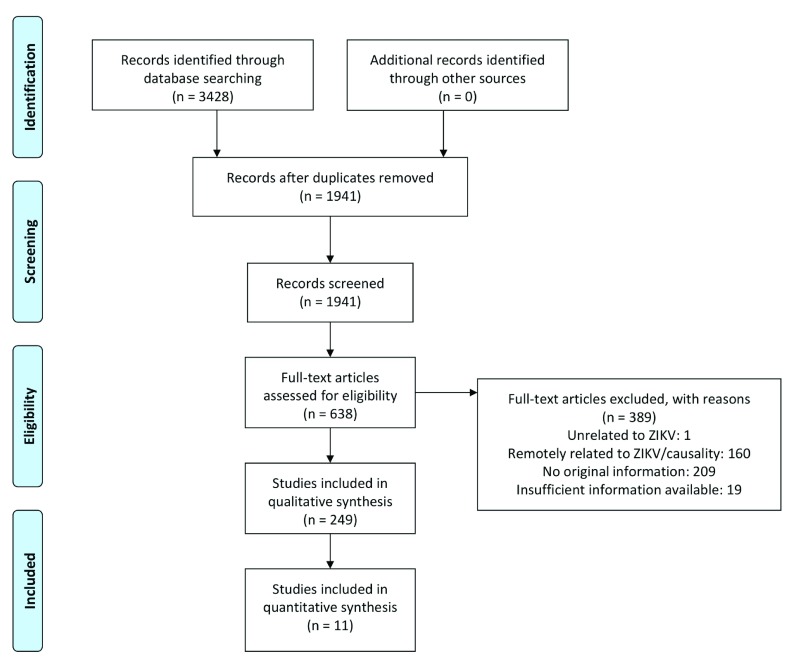

From January 19, 2017 to July 1, 2019 we screened 1941 publications, of which we included 638 based on title and abstract. After reviewing the full text, 249 publications were included ( Table 2, Figure 3). Of these publications, 195 reported on congenital abnormalities linked to ZIKV 24– 217 and 59 on GBS 4, 44, 118, 201, 203, 206, 218– 270. Five outbreak reports described both outcomes 44, 118, 201, 203, 206.

Table 2. Included publications in the baseline review, update 1 and update 2 (this version), by outcome and epidemiological study design.

The latest and previous versions of this table are available as extended data 16.

| Outcome | Adverse congenital outcomes,

number of publications |

GBS,

number of publications |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Review period/version | Baseline * | Update1 † | Update2 | Baseline * | Update1 † | Update2 |

| Study design | ||||||

| Case report | 9 | 13 | 39 | 9 | 5 | 17 |

| Case series | 22 | 12 | 62 | 5 | 11 | 22 |

| Case-control study | 0 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Cohort study | 1 | 8 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cross-sectional study | 2 | 1 | 19 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Controlled trials | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ecological study/outbreak report | 5 | 4 | 27 | 19 | 7 | 9 |

| Modelling study | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total: | 41 | 40 | 195 | 34 | 25 | 59 |

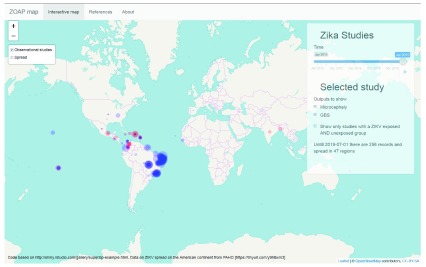

Figure 2. Map of the epidemiological studies that report on adverse congenital outcomes (blue) or Guillain-Barré syndrome (red) associated with Zika virus exposure.

The size of the points correspond with the number of exposed individuals with the adverse outcome, according to the definitions used in the publications. The latest and previous versions of this figure are available as extended data 16.

Figure 3. PRISMA flow-chart of publications retrieved, screened and included between January 18, 2017 and July 1, 2019.

Adapted from: Moher et al. (2009) 18. The latest and previous versions of this figure are available as extended data 16.

Adverse congenital outcomes

We included 39 case reports 24– 61, 62 case series 62– 123, 10 case-control studies 124– 133, 35 cohort studies 134– 168, 19 cross-sectional studies 169– 187, seven ecological studies 188– 194, three modelling studies 195– 197 and 20 outbreak reports 198– 217 that report on congenital abnormalities linked to ZIKV.

Causality dimensions

Strength of association. Individual level: In this review period, five case-control studies reported on strength of association, four in Brazil (n=670 participants) 125, 126, 128, 130 and one in French Polynesia (n=123 participants) 131. The studies assess adverse pregnancy outcomes including infants born with microcephaly, according to exposure to ZIKV for cases. Of these, all studies matched controls, based on gestational age and/or region. During the review period up to January 18, 2017, we included one case-control study 271, which we replaced with a publication reporting the final results of the study 126. The meta-analyses incorporate estimates from studies identified in all review periods.

Assessment of exposure status varied between the studies (Extended data, Supplementary File 3 17). In five case-control studies, exposure to ZIKV was assessed in the mother, based on clinical symptoms of ‘suspected Zika virus infection’ 125, or presence of maternal antibodies measured by IgM (Kumar et al. (2016) 272), PRNT (de Araujo et al. (2018) 126, Subissi et al. (2018) 131), or both PRNT and IgG (Moreira-Soto et al. (2018)) maternal antibody 127.

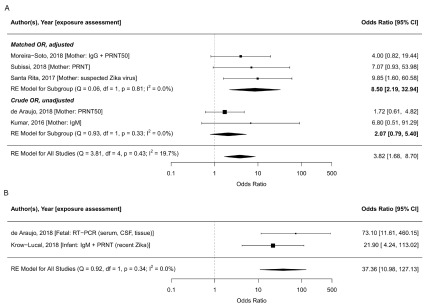

In meta-analysis, we found that the odds of adverse congenital outcomes (microcephaly or congenital abnormalities) were 3.8 times higher in ZIKV-infected mothers (95% CI: 1.7-8.7, tau 2=0.18, I 2=19.8%, Figure 4). Moreira-Soto et al. (2018) found that in Bahia, Brazil, Chikungunya infection was also associated with being a case 127.

Figure 4.

Forest plot and meta-analysis of case-control studies reporting on ZIKV infection assessed in mothers ( A) and in infants ( B) and adverse congenital outcomes (microcephaly, congenital malformations, central nervous system abnormalities). The odds ratio from the five case-control studies that assess exposure in mothers combined is 3.8 (95% CI: 1.7-8.7, tau 2=2.37, I 2=19.8%); the odds ratio for the studies that assess exposure in infants is 37.4 (95% CI: 11.0-127.1, tau 2=0, I 2=0%). The odds ratios are plotted on the log scale. Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid, PRNT, plaque reduction neutralisation test; RE, random effects; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. The latest and previous versions of this figure are available as extended data 16.

In two matched case-control studies, exposure to ZIKV was assessed in infants; Araujo et al. found a 73.1 (95% CI 13·0–Inf) times higher odds was reported for microcephaly when ZIKV infection was assessed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in the neonate 126. Krow-Lucal et al. (2018) found an OR of 21.9 (95% CI: 7.0-109.3) based on evidence of recent Zika infection assessed using IgM followed by PRNT in infants in Paraiba, Brazil 128. When exposure was assessed at the infant-level, the combined odds of adverse congenital outcomes was 37.4 times higher (95% CI: 11.0-127.1, tau 2=0, I 2=0%, Figure 4).

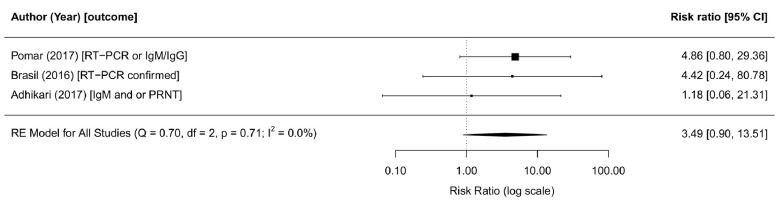

In this review period, one cohort study reported on strength of association, in 610 pregnant women returning from ZIKV-affected areas in Central and South America to the USA 138. Maternal ZIKV exposure was measured using RT-PCR or IgM followed by plaque reduction neutralisation test (PRNT). Among the 28 infants born to ZIKV-infected mothers, none was diagnosed with microcephaly and, one was born with a major malformation. In the ZIKV-unexposed group, eight out of 306 had major malformations. A complete overview of different outcomes assessed is presented in the extended data, Supplementary File 3 17. During the review period up to January 18, 2017, we included two cohort studies, one in women with rash and fever (Brasil et al. (2016)) and one in unselected pregnant women (Pomar et al. (2017)) 273, 274. In meta-analysis of all three studies, we found that the risk of microcephaly was 3.5 times higher in ZIKV-infected mothers of babies (95% CI: 0.90-13.51, tau 2=0, I 2=0%, Figure 5).

Figure 5. Forest plot and meta-analysis of cohort studies reporting on ZIKV infection and adverse congenital outcomes.

The risk ratio from the random effects model is 3.5 (95% CI: 0.9-13.5, tau2=0,I 2=0%). The risk ratios are provided on the log scale. Abbreviations: ZIKV, Zika virus; PRNT, plaque reduction neutralisation test; RE, random effects; RT-PCR, Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. The latest and previous versions of this figure are available as extended data.

Population level: At a population level, data from Mexico collected at different altitudes during the ZIKV outbreak, showed that the risk of microcephaly was increased in regions at altitudes below 2200m, in which ZIKV can circulate 196. Hay et al. (2018) reanalysed surveillance data from Colombia and northeast Brazil and concluded that time-dependent reporting changes might have caused apparent inconsistencies in the proportion of congenital abnormalities as a result of maternal ZIKV infection 197.

Dose response. Halai et al. (2017) 120 examined the severity of congenital outcomes according to measures of the severity of maternal ZIKV infection in a subset of mothers in the cohort presented by Brasil et al. (2016) 274. They evaluated ZIKV load, assessed by RT-PCR using the cycle threshold (CT) as a measure of number of RNA copies, and a severity score of symptoms in 131 pregnant women. They concluded that neither higher viral load nor more severe symptoms was associated with more severe congenital abnormalities 136. Moreira-Soto et al. found higher maternal antibody titers in microcephaly cases compared with controls 127. In previous review periods, Honein et al. (2016) compared outcomes in neonates born to symptomatic and asymptomatic infected pregnant women returning to the USA with possible ZIKV infection and found no differences 275.

Specificity. Although some outcomes, such as lingual phenotype 177 or neurogenic bladder 276, have been hypothesised as a specific phenotype for congenital ZIKV infection, no additional evidence was identified that certain congenital adverse findings are specific for congenital ZIKV infection.

Consistency. Geographical region: All four WHO geographic regions (the Africa region [AFRO], the American region [AMRO], the South-East Asian region [SEARO] and the Western Pacific region [WPRO]) with past or active ZIKV transmission have now reported congenital abnormalities due to ZIKV infection. During this review period, the first congenital abnormality due to infection with the Asian lineage of the virus on the African mainland occurred in a traveller returning from Angola 47. Possible cases of congenital abnormalities have occurred in Guinea-Bissau 96. In the most recent WHO situation report from March 2017, two cases of microcephaly are documented in Thailand and one in Vietnam, which were also described in detail in other works 24, 54, 107. We identified another publication on congenital abnormalities due to endemic ZIKV in Cambodia 110. The occurrence of congenital adverse outcomes in AFRO, SEARO, and WPRO seems sporadic, despite the endemic circulation of ZIKV. As noted above, the observed complication rate varied strongly between regions. Extended data, Supplementary File 3 provides a full overview of the published studies on congenital abnormalities per region and country 17.

Traveller/non-traveller populations: In this update, we found further evidence that congenital abnormalities occurred in infants born to women travellers returning from ZIKV-affected areas and women remaining in those areas. In total, 25 publications report on 272 congenital abnormalities due to ZIKV infection in travellers 27, 29, 30, 32, 34, 36, 38, 42, 45, 56, 58, 61, 89, 94, 98, 109, 117, 122, 123, 137, 140, 151, 153, 166, 173, with 109 publications reporting congenital abnormalities due to ZIKV in 2652 non travellers 24– 26, 28, 31, 33, 35, 37, 39– 41, 43, 44, 46– 48, 50, 51, 54, 57, 60, 62– 79, 81, 83– 85, 87, 88, 90– 93, 95– 97, 100, 101, 104– 106, 110– 113, 115, 116, 118, 119, 121, 124– 135, 142– 147, 149, 152, 154, 156– 164, 167, 168, 171, 172, 175– 180, 182, 186

In this review period, evidence emerged that transmission through sexual contact with infected travellers also resulted in foetal infection 58, 59.

Study designs: The association between ZIKV infection and congenital abnormalities was consistent across different study designs ( Table 2).

Lineages: We found no new evidence of consistency across different lineages from observational studies. The currently observed adverse congenital outcomes are linked to the ZIKV of the Asian lineage.

Risk of bias assessment

In all case-control studies, uncertainty about the exposure status due to imperfect tests could result in a bias towards the null. Some studies might suffer from recall bias where exposure was assessed by retrospectively asking about symptoms 125, 131. For the cohort studies 138, 274, the enrolment criteria were based on symptomatology. As a result, even in the absence of evidence of ZIKV, the unexposed groups might have had conditions that were unfavourable to their pregnancy. We expect this to bias the results towards the null or underestimate the true effect. Owing to imperfect diagnostic techniques, both false positives (IgM, cross reactivity) and false negatives (due to the limited detection window for RT-PCR) might occur, potentially resulting in bias; the direction of this bias would often be towards the null. None of the studies controlled for potential confounding. Extended data, Supplementary File 4 provides the full risk of bias assessment of the studies included in the meta-analysis 17.

GBS

During this review period, we included 17 case reports 44, 218– 233, 22 case series 118, 234– 254, seven case-control studies 4, 255– 260, one ecological study 264, one modelling study 265 and eight outbreak reports 201, 203, 206, 266– 270 that reported on ZIKV infection and GBS.

During this review period, we included 17 case reports 46, 220– 235, 22 case series 120, 236– 256, seven case-control studies 4, 257– 262, one ecological study 266, one modelling study 265 and eight outbreak reports 201, 203, 206, 266– 270 that reported on ZIKV infection and GBS.

Causality dimensions

Strength of association. Individual level. The number of studies reporting on the strength of association between ZIKV infection and GBS at an individual level increased substantially. We identified five case-control studies 255– 259 published since the previous update, which included one case-control study from French Polynesia 277. All studies were matched for age and place of residence. In the studies from Brazil, Colombia, Puerto Rico and New Caledonia, temporal clustering of cases in association with ZIKV circulation was documented 255– 258. In Bangladesh, ZIKV transmission was endemic 259. Exposure assessment was based on serology 255, 256 or a combination of RT-PCR and serology 257– 259. Extended data, Supplementary File 3 shows the variability in ORs according to criteria for ZIKV exposure assessment, based on unmatched crude data extracted from each case-control study 17.

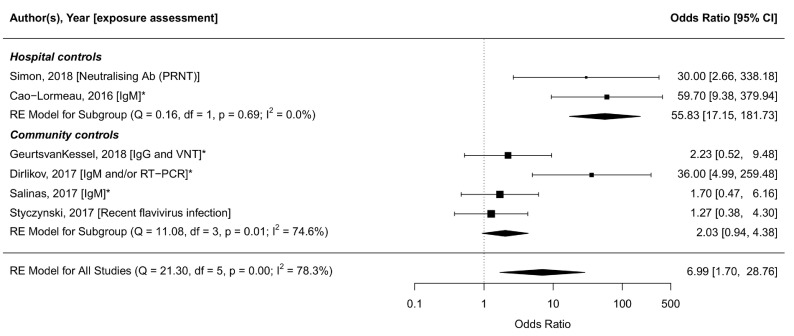

Figure 6 shows the association between GBS and ZIKV infection, using the diagnostic criteria that were most similar across studies. Heterogeneity was considerable (I 2=78.3%), but was reduced slightly after stratification based on the method of selection of controls. The summary OR was higher in studies that enrolled controls from hospital (OR: 55.8, 95% CI: 17.2-181.7, tau 2=0, I 2=0%) 258, 277 than in studies that enrolled controls at random from within the same community 255– 257 or from the same household 259 (OR: 2.0, 95% CI: 0.8-5.4, tau 2=0.46, I 2=74.6%). Amongst studies with community controls, ORs were lower when enrolment and assessment took place several months after onset of symptoms 255, 256 than in studies with contemporaneous enrolment 257, 259. To further illustrate the heterogeneity in exposure assessment between and within the studies, we provide additional aggregations of the data in Extended data, Supplementary File 3 17.

Figure 6. Forest plot of six included case-control studies and their exposure assessment.

Odds ratios (ORs) are shown on the log-scale. The meta-analysis is stratified by the selection of controls: Hospital controls, or community/household controls. Most similar exposure assessment measures are compared (IgM 256, 258, 259, 277, recent flavivirus infection 255, or IgM and/or RT-PCR 257). OR: 7.0 [95% CI: 1.7-28.8, tau2=2.78, I 2=78.3%]. ORs from studies marked with an asterisk (*) are matched ORs, unmarked studies provided crude ORs. The latest and previous versions of this figure are available as extended data 16.

Population level. At a population level, Mier-Y-Teran-Romero et al. (2018) found that the estimated incidence of GBS ranged between 1.4 (0.4–2.5) and 2.2 (0.8–5.0) per 10,000 ZIKV infections comparing surveillance/reported cases from Brazil, Colombia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, French, Honduras, Puerto Rico, Suriname, Venezuela, and Micronesia. The across-location minimum and maximum estimates were used to estimate an average risk of having GBS and being reported after ZIKV infection across locations of approximately 2.0 GBS cases per 10,000 infections (95% credible interval 0.5–4.5 per 10,000 ZIKV infections) 265.

Dose response. In a case-control study, Lynch et al. (2018) found higher titres of neutralising antibodies in ZIKV-infected GBS cases than in patients with symptomatic ZIKV infection but without GBS 260.

Specificity. Dirlikov et al. (2018) compared Puerto Rican GBS cases reported through public health surveillance that were preceded by ZIKV and cases that were not preceded by ZIKV infection 249. Clinical features involving cranial nerves were observed more frequently in ZIKV-related cases and, at a six-month follow-up visit, residual cranial neuropathy was noted more often in this group. However, clinical symptoms did not allow a distinction to be made between ZIKV and non-ZIKV related GBS.

Consistency. Geographical region: During this review period, GBS likely due to ZIKV infection was reported in Asia; including Thailand, Bangladesh, Singapore and India 4, 48, 252, 259. Publication in the WHO Region of the Americas followed the pattern as observed before and no GBS linked to ZIKV infection was reported in Africa. Extended data, Supplementary File 3 provides a full overview of the published studies on congenital abnormalities by region and country 17. In a reanalysis of surveillance data from the Region of the Americas, Ikejezie et al. (2016) found consistent time trends between GBS incidence and ZIKV incidence 264.

Traveller/non-traveller populations: In studies included in this update, we found additional evidence of GBS in both travellers and non-travellers with ZIKV infection. Ten publications report on 11 travellers 218, 220, 222– 224, 227, 229, 232– 234, while 34 publications report GBS due to ZIKV in 402 non travellers 4, 44, 118, 219, 221, 225, 226, 228, 230, 231, 235– 237, 239– 247, 249, 251, 253– 260, 262, 263.

Study designs: Across the different study designs, the relation between GBS and ZIKV is consistently shown. Table 2 and Extended data, Supplementary File 3 provide an overview of the included study designs 17.

Lineages: We still lack evidence on the consistency of the relation between GBS and ZIKV across different lineages from observational studies. The observed cases of GBS were linked to ZIKV of the Asian lineage.

Risk of bias assessment

Potential selection bias in case-control studies was introduced by the selection of controls from hospitals rather than from the communities in which the cases arose 258, 277. Uncertainty about the exposure status due to imperfect tests would tend to result in a bias towards the null. Two case-control studies did not conduct a matched analysis although controls were matched, and no study controlled for potential confounding by factors other than those used for matching. Exclusion criteria and participation rate, especially of the controls, were poorly reported. Extended data, Supplementary File 4 provides the full risk of bias assessment of the studies included in the meta-analysis 17.

Discussion

In this living systematic review, we summarised the evidence from 249 observational studies in humans on four dimensions of the causal relationship between ZIKV infection and adverse congenital outcomes and GBS, published between January 18, 2017 and July 1, 2019.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this living systematic review are, first, that we automated much of the workflow 10; we searched both international and regional databases daily and we screen papers for eligibility as they became available, so publication bias is unlikely. Second, we have quantified the strength of association between ZIKV infection and congenital abnormalities and GBS and investigated heterogeneity of outcome and exposure assessment within and between studies. Third, for congenital outcomes, we included studies with both microcephaly and other possible adverse outcomes, acknowledging the spectrum of congenital adverse outcomes caused by ZIKV. This work also has several limitations. First, we have not assessed the dimensions of the causality framework that involve laboratory studies, so we have not updated the pathobiology of ZIKV complications, which was addressed in the baseline review 8 and the first update to January 2017 10. Limiting the review to epidemiological domains has allowed more detailed analyses of these studies and we hope that laboratory scientists will continue to review advances in these domains. Second, the rate of publications on ZIKV remains high so, despite the reduced scope and automation, maintenance of the review is time-consuming and data extraction cannot be automated. Third, this review may suffer from continuity bias, which is important for the conduct and interpretation of living systematic reviews and results from changes in the author team. Careful adherence to the protocol will reduce this risk.

Interpretation of the findings

ZIKV and congenital abnormalities: Since the earlier versions of the review 8, 10, evidence on the causal relationship between ZIKV infection and congenital abnormalities has expanded. Unfortunately, the total number of cases investigated in the published cohort or case-control studies remains small. In case-control studies in which infants with microcephaly or other congenital abnormalities are compared with unaffected infants, the strength of association differs according to whether exposure to ZIKV is assessed in in the mother (OR 3.8, 95% CI: 1.7-8.7, tau 2=0.18, I 2=19.8%) or the foetus/infant (OR 37.4, 95% CI: 11.0-127.1, tau 2=0, I 2=0%). This large difference in effect size can be attributed to the fact that not all maternal ZIKV infections result in foetal infection. In cohort studies, the risk of congenital abnormalities was 3.5 times higher (95% CI: 0.9-13.5, I 2=0%, tau 2=0) in mothers with evidence of ZIKV infection than without, which is similar to the OR for maternal exposure to ZIKV estimated from case-control studies. Further research is needed to understand the drivers of mother to child transmission. Higher maternal antibody titres were correlated with a higher incidence of adverse congenital outcomes in one case-control study 127. However, amongst ZIKV-infected mothers followed prospectively, severity of ZIKV infection was not associated with more severe congenital abnormalities 136. Convincing evidence on a dose-response relation is therefore still lacking.

ZIKV and GBS: Evidence on the causal relation between ZIKV infection and GBS has grown since our last review 10. The body of evidence is still smaller than that for congenital abnormalities, possibly because GBS is a rare complication, estimated to occur in 0.24 per 1000 ZIKV infections 277. In this review, the strength of association between GBS and ZIKV infection, estimated in case-control studies, tended to be lower than observed in the first case-control study reported by Cao-Lormeau (2016) in French Polynesia 277. It is possible that the finding by Cao-Lormeau et al. was a ‘random high’, a chance finding 278. Simon et al., however, found a similarly strong association in a case-control study in New Caledonia 258. In both these studies, controls were patients in the same hospital. Although matched for place of residence, it is possible that they were less likely to have been exposed to ZIKV than the cases, resulting in an overestimation of the OR. In case-control studies in which controls were enrolled from the same communities as the cases, estimated ORs were lower, presumably because exposure to ZIKV amongst community-enrolled controls is less biased than amongst hospital controls 279. Under-ascertainment of ZIKV infection in case-control studies in which enrolment occurred several months after the onset of symptoms 255, 256 is also likely to have reduced the observed strength of association. There is also possible evidence of a dose-response relationship, with higher levels of neutralising antibodies to both ZIKV and dengue in people with GBS 260. However, the level of antibody titre might not be an appropriate measure of viral titre, and merely a reflection of the intensity of the immune response. Taking into account the entire body of evidence, inference to the best explanation 280 supports the conclusion that ZIKV is a cause of GBS. The prospect of more precise and robust estimates of the strength of association between ZIKV and GBS is low because outbreaks need to be sufficiently large to enrol enough people with GBS. In the large populations that were exposed during the 2015–2017 outbreak, herd immunity will limit future ZIKV outbreaks.

Implications for future research

The sample sizes of studies published to date are smaller than those recommended by WHO for obtaining precise estimates of associations between ZIKV and adverse outcomes [ Harmonization of ZIKV Research Protocols to Address Key Public Health]. Given the absence of large new outbreaks of ZIKV infection in 2017–2019, there is a need for consortia of researchers to analyse their data in meta-analyses based on individual participant data [ Individual Participant Data Meta-analysis of Zika-virus related cohorts of pregnant women (ZIKV IPD-MA)]. Future collaborative efforts will help to quantify the absolute risks of different adverse congenital outcomes and allow investigation of heterogeneity between studies 136, 149, 275.

This review highlights additional research gaps. We did not assess the complication rates within the infected group in studies without an unexposed comparison group; the adverse outcomes are not pathognomonic for ZIKV infection, making an appropriate comparison group necessary. Although there are no individual features of ZIKV infection that are completely specific, the growing number of publications on ZIKV will allow better ascertainment of the features of a congenital Zika syndrome 281. In this review, we did not take into account the performance of the diagnostic tests in assessing the strength of association. Future research should include robust validation studies, and improved understanding of contextual factors in the performance of diagnostic tests, including the influence of previous circulation of other flaviviruses, the prevalence of ZIKV and the test used.

This living systematic review will continue to follow studies of adverse outcomes originating from ZIKV circulation in the Americas, but research in regions with endemic circulation of ZIKV is expected to increase. Such studies will clarify whether ZIKV circulation in Africa and Asia also results in adverse outcomes, as suggested by the case-control study of GBS from Bangladesh 259. Increased awareness might improve the evidence-base in these regions, where misperceptions about the potential risks of ZIKV-associated disease with different virus lineages has been reported 282. An important outstanding question remains whether the absence of reported cases of congenital abnormalities or GBS in these regions represent a true absence of complications or is this due to weaker surveillance systems or reporting 283. The conclusions that ZIKV infection causes adverse congenital outcomes and GBS are reinforced with the evidence published between January 18, 2017 and July 1, 2019.

Data availability

Underlying data

All data underlying the results are available as part of the article and no additional source data are required.

Extended data

Harvard dataverse: Living systematic review on adverse outcomes of Zika - Supplementary Material. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/S7USUI 17

This project contains the following extended data:

SupplementaryFile1Prisma.docx (PRISMA checklist)

SupplementaryFile2Methods.docx (Supplementary file 2, additional information to the Methods)

SupplementaryFile3Results.docx (Supplementary file 3, additional information to the Results)

SupplementaryFile4ROB.tab (Risk of bias assessment)

Harvard dataverse: Living systematic review on adverse outcomes of Zika - Figures and Table. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DLP5AN 16

This project contains the following extended data:

Fig1.pdf (Most recent version of Figure 1)

Fig2.pdf (Most recent version of Figure 3, PRISMA flowchart)

Fig3A.pdf (Most recent version of Figure 4A)

Fig3B.pdf (Most recent version of Figure 4B)

Fig4.pdf (Most recent version of Figure 5)

Fig5.pdf (Most recent version of Figure 6)

Table1.pdf (Most recent version of Table 1)

Table2.pdf (Most recent version of Table 2)

Reporting guidelines

PRISMA checklist and flow diagram for ‘Zika virus infection as a cause of congenital brain abnormalities and Guillain-Barré syndrome: A living systematic review’, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/S7USUI and Figure 2.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation [320030_170069], end date: 31/10/2021

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; peer review: 2 approved]

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1. Butler D: Drop in cases of Zika threatens large-scale trials. Nature. 2017;545(7655):396–7. 10.1038/545396a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Colón-González FJ, Peres CA, Steiner São Bernardo C, et al. : After the epidemic: Zika virus projections for Latin America and the Caribbean. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(11):e0006007. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hamer DH, Chen LH: Zika in Angola and India. J Travel Med. 2019;26(5): taz012. 10.1093/jtm/taz012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Umapathi T, Kam YW, Ohnmar O, et al. : The 2016 Singapore Zika virus outbreak did not cause a surge in Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2018;23(3):197–201. 10.1111/jns.12284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ruchusatsawat K, Wongjaroen P, Posanacharoen A, et al. : Long-term circulation of Zika virus in Thailand: an observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(4):439–46. 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30718-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Althouse BM, Vasilakis N, Sall AA, et al. : Potential for Zika Virus to Establish a Sylvatic Transmission Cycle in the Americas. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(12):e0005055. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heymann DL, Hodgson A, Sall AA, et al. : Zika virus and microcephaly: why is this situation a PHEIC? Lancet. 2016;387(10020):719–21. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00320-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krauer F, Riesen M, Reveiz L, et al. : Zika Virus Infection as a Cause of Congenital Brain Abnormalities and Guillain-Barré Syndrome: Systematic Review. PLoS Med. 2017;14(1):e1002203. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Elliott JH, Turner T, Clavisi O, et al. : Living systematic reviews: an emerging opportunity to narrow the evidence-practice gap. PLoS Med. 2014;11(2):e1001603. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Counotte M, Egli-Gany D, Riesen M, et al. : Zika virus infection as a cause of congenital brain abnormalities and Guillain-Barré syndrome: From systematic review to living systematic review [version 1; peer review: 2 approved, 1 approved with reservations]. F1000Res. 2018;7:196. 10.12688/f1000research.13704.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Devakumar D, Bamford A, Ferreira MU, et al. : Infectious causes of microcephaly: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):e1–e13. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30398-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frenkel LD, Gomez F, Sabahi F: The pathogenesis of microcephaly resulting from congenital infections: why is my baby's head so small? Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;37(2):209–26. 10.1007/s10096-017-3111-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Koopmans M, de Lamballerie X, Jaenisch T, et al. : Familiar barriers still unresolved-a perspective on the Zika virus outbreak research response. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(2):e59–e62. 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30497-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fischer C, Pedroso C, Mendrone A, Jr, et al. : External Quality Assessment for Zika Virus Molecular Diagnostic Testing, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(5):888–892. 10.3201/eid2405.171747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Charrel R, Mogling R, Pas S, et al. : Variable Sensitivity in Molecular Detection of Zika Virus in European Expert Laboratories: External Quality Assessment, November 2016. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55(11):3219–26. 10.1128/JCM.00987-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Counotte MJ: Living systematic review on adverse outcomes of Zika - Figures and Table. Harvard Dataverse, V3.2019. 10.7910/DVN/DLP5AN [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Counotte MJ: Living systematic review on adverse outcomes of Zika - Supplementary Material. Harvard Dataverse, V1, UNF:6:sAGbGceAYGoHLIT7sDtDsw== [fileUNF].2019. 10.7910/DVN/S7USUI [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. : Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. : Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Viechtbauer W: Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36(3):1–48. 10.18637/jss.v036.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Higgins JP, Thompson SG: Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58. 10.1002/sim.1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. R Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria.2018. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Robins JM: A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology. 2004;15(5):615–25. 10.1097/01.ede.0000135174.63482.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moi ML, Nguyen TT, Nguyen CT, et al. : Zika virus infection and microcephaly in Vietnam. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(8):805–6. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30412-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Santos VS, Oliveira SJG, Gurgel RQ, et al. : Case Report: Microcephaly in Twins due to the Zika Virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97(1):151–4. 10.4269/ajtmh.16-1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mattar S, Ojeda C, Arboleda J, et al. : Case report: microcephaly associated with Zika virus infection, Colombia. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):423. 10.1186/s12879-017-2522-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zacharias N, Whitty J, Noblin S, et al. : First Neonatal Demise with Travel-Associated Zika Virus Infection in the United States of America. AJP Rep. 2017;7(2):e68–e73. 10.1055/s-0037-1601890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Benjamin I, Fernández G, Figueira JV, et al. : Zika virus detected in amniotic fluid and umbilical cord blood in an in vitro fertilization-conceived pregnancy in Venezuela. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(6):1319–22. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.02.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kaur G, Manganas L: EEG findings in a case of congenital zika virus syndrome. Neurology. 2017;88(16 Supplement 1). Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 30. Saulino D, Gaston E, Younke B, et al. : The first zika-related infant mortality in the United States: An autopsy case report. Laboratory Investigation. 2017;97:10A. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zuanazzi D, Arts EJ, Jorge PK, et al. : Postnatal Identification of Zika Virus Peptides from Saliva. J Dent Res. 2017;96(10):1078–84. 10.1177/0022034517723325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lovagnini Frutos MG, Ochoa JH, Barbás MG, et al. : New Insights into the Natural History of Congenital Zika Virus Syndrome. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2018;44(1):72–6. 10.1159/000479866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Villamil-Gomez WE, Guijarro E, Castellanos J, et al. : Congenital Zika syndrome with prolonged detection of Zika virus RNA. J Clin Virol. 2017;95:52–4. 10.1016/j.jcv.2017.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rodó C, Suy A, Sulleiro E, et al. : In utero negativization of Zika virus in a foetus with serious central nervous system abnormalities. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(5):549 e1–e3. 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jucá E, Pessoa A, Ribeiro E, et al. : Hydrocephalus associated to congenital Zika syndrome: does shunting improve clinical features? Childs Nerv Syst. 2018;34(1):101–6. 10.1007/s00381-017-3636-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Raymond A, Jakus J: Cerebral Infarction and Refractory Seizures in a Neonate with Suspected Zika Virus Infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37(4):e112–e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rabelo K, de Souza Campos Fernandes RC, de Souza LJ, et al. : Placental Histopathology and Clinical Presentation of Severe Congenital Zika Syndrome in a Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Exposed Uninfected Infant. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1704. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Angelidou A, Michael Z, Hotz A, et al. : Is There More to Zika? Complex Cardiac Disease in a Case of Congenital Zika Syndrome. Neonatology. 2018;113(2):177–82. 10.1159/000484656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. de Freitas Ribeiro BN, Muniz BC, Gasparetto EL, et al. : Congenital involvement of the central nervous system by the Zika virus in a child without microcephaly - spectrum of congenital syndrome by the Zika virus. J Neuroradiol. 2018;45(2):152–3. 10.1016/j.neurad.2017.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chimelli L, Moura Pone S, Avvad-Portari E, et al. : Persistence of Zika Virus After Birth: Clinical, Virological, Neuroimaging, and Neuropathological Documentation in a 5-Month Infant With Congenital Zika Syndrome. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2018;77(3):193–8. 10.1093/jnen/nlx116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Regadas VC, Silva MCE, Abud LG, et al. : Microcephaly caused by congenital Zika virus infection and viral detection in maternal urine during pregnancy. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2018;64(1):11–4. 10.1590/1806-9282.64.01.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schwartz KL, Chan T, Rai N, et al. : Zika virus infection in a pregnant Canadian traveler with congenital fetal malformations noted by ultrasonography at 14-weeks gestation. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines. 2018;4:2. 10.1186/s40794-018-0062-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Prata-Barbosa A, Cleto-Yamane TL, Robaina JR, et al. : Co-infection with Zika and Chikungunya viruses associated with fetal death-A case report. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;72:25–7. 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.04.4320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rabelo K, Souza LJ, Salomão NG, et al. : Placental Inflammation and Fetal Injury in a Rare Zika Case Associated With Guillain-Barré Syndrome and Abortion. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1018. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Guevara JG, Agarwal-Sinha S: Ocular abnormalities in congenital Zika syndrome: a case report, and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12(1):161. 10.1186/s13256-018-1679-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Giovanetti M, Goes de Jesus J, Lima de Maia M, et al. : Genetic evidence of Zika virus in mother's breast milk and body fluids of a newborn with severe congenital defects. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(10):1111–2. 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sassetti M, Zé-Zé L, Franco J, et al. : First case of confirmed congenital Zika syndrome in continental Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2018;112(10):458–62. 10.1093/trstmh/try074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Brito CAA, Henriques-Souza A, Soares CRP, et al. : Persistent detection of Zika virus RNA from an infant with severe microcephaly - a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):388. 10.1186/s12879-018-3313-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gunturiz ML, Cortés L, Cuevas EL, et al. : Congenital cerebral toxoplasmosis, Zika and chikungunya virus infections: a case report. Biomedica. 2018;38(2):144–52. 10.7705/biomedica.v38i0.3652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Valdespino-Vázquez MY, Sevilla-Reyes EE, Lira R, et al. : Congenital Zika Syndrome and Extra-Central Nervous System Detection of Zika Virus in a Pre-term Newborn in Mexico. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(6):903–12. 10.1093/cid/ciy616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ventura CV, Bandstra ES, Fernandez MP, et al. : First Locally Acquired Congenital Zika Syndrome Case in the United States: Neonatal Clinical Manifestations. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2018;49(9):e93–e8. 10.3928/23258160-20180907-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lemos de Carvalho A, Brites C, Taguchi TB, et al. : Congenital Zika Virus Infection with Normal Neurodevelopmental Outcome, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(11):2128–30. 10.3201/eid2411.180883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ho CY, Castillo N, Encinales L, et al. : Second-trimester Ultrasound and Neuropathologic Findings in Congenital Zika Virus Infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37(12):1290–3. 10.1097/INF.0000000000002080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wongsurawat T, Jenjaroenpun P, Athipanyasilp N, et al. : Genome Sequences of Zika Virus Strains Recovered from Amniotic Fluid, Placenta, and Fetal Brain of a Microcephaly Patient in Thailand, 2017. Microbiol Resour Announc. 2018;7(11): pii: e01020-18. 10.1128/MRA.01020-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ribeiro BNF, Marchiori E: Congenital Zika syndrome associated with findings of cerebellar cortical dysplasia - Broadening the spectrum of presentation of the syndrome. J Neuroradiol. 2018; pii: S0150-9861(18)30261-X. 10.1016/j.neurad.2018.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lockrow J, Tully H, Saneto RP: Epileptic spasms as the presenting seizure type in a patient with a new "O" of TORCH, congenital Zika virus infection. Epilepsy Behav Case Rep. 2018;11:1–3. 10.1016/j.ebcr.2018.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Davila-Castrodad NM, Reyes-Bou Z, Correa-Rivas M, et al. : First Autopsy of a Newborn with Congenital Zika Syndrome in Puerto Rico. P R Health Sci J. 2018;37(Special Issue):S81–S4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yarrington CD, Hamer DH, Kuohung W, et al. : Congenital Zika syndrome arising from sexual transmission of Zika virus, a case report. Fertil Res Pract. 2019;5: 1. 10.1186/s40738-018-0053-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Khatib A, Showler AJ, Kain D, et al. : A diagnostic gap illuminated by a sexually-transmitted case of congenital Zika virus infection. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2019;27:117–8. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2018.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Santos GR, Pinto CAL, Prudente RCS, et al. : Case Report: Histopathologic Changes in Placental Tissue Associated With Vertical Transmission of Zika Virus. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2019. 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sulleiro E, Frick MA, Rodó C, et al. : The challenge of the laboratory diagnosis in a confirmed congenital Zika virus syndrome in utero: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(20):e15532. 10.1097/MD.0000000000015532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. de Paula Freitas B, Zin A, Ko A, et al. : Anterior-Segment Ocular Findings and Microphthalmia in Congenital Zika Syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(12):1876–8. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Linden VV, Linden HV Junior, Leal MC, et al. : Discordant clinical outcomes of congenital Zika virus infection in twin pregnancies. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2017;75(6):381–6. 10.1590/0004-282X20170066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Leal MC, van der Linden V, Bezerra TP, et al. : Characteristics of Dysphagia in Infants with Microcephaly Caused by Congenital Zika Virus Infection, Brazil, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(8):1253–9. 10.3201/eid2308.170354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Parra-Saavedra M, Reefhuis J, Piraquive JP, et al. : Serial Head and Brain Imaging of 17 Fetuses With Confirmed Zika Virus Infection in Colombia, South America. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):207–12. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Aragao MFVV, Holanda AC, Brainer-Lima AM, et al. : Nonmicrocephalic Infants with Congenital Zika Syndrome Suspected Only after Neuroimaging Evaluation Compared with Those with Microcephaly at Birth and Postnatally: How Large Is the Zika Virus "Iceberg"? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38(7):1427–34. 10.3174/ajnr.A5216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cabral CM, Nóbrega M, Leite PLE, et al. : Clinical-epidemiological description of live births with microcephaly in the state of Sergipe, Brazil, 2015. Epidemiol Serv Saude. 2017;26(2):245–54. 10.5123/S1679-49742017000200002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sousa AQ, Cavalcante DIM, Franco LM, et al. : Postmortem Findings for 7 Neonates with Congenital Zika Virus Infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(7):1164–7. 10.3201/eid2307.162019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Ventura LO, Ventura CV, Lawrence L, et al. : Visual impairment in children with congenital Zika syndrome. J AAPOS. 2017;21(4):295–299.e2. 10.1016/j.jaapos.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ramalho FS, Yamamoto AY, da Silva LL, et al. : Congenital Zika Virus Infection Induces Severe Spinal Cord Injury. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(4):687–90. 10.1093/cid/cix374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Cavalcanti DD, Alves LV, Furtado GJ, et al. : Echocardiographic findings in infants with presumed congenital Zika syndrome: Retrospective case series study. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175065. 10.1371/journal.pone.0175065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Yepez JB, Murati FA, Pettito M, et al. : Ophthalmic Manifestations of Congenital Zika Syndrome in Colombia and Venezuela. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(5):440–5. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.0561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Aragao MFVV, Brainer-Lima AM, Holanda AC, et al. : Spectrum of Spinal Cord, Spinal Root, and Brain MRI Abnormalities in Congenital Zika Syndrome with and without Arthrogryposis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38(5):1045–53. 10.3174/ajnr.A5125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Chimelli L, Melo ASO, Avvad-Portari E, et al. : The spectrum of neuropathological changes associated with congenital Zika virus infection. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;133(6):983–99. 10.1007/s00401-017-1699-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Meneses JDA, Ishigami AC, de Mello LM, et al. : Lessons Learned at the Epicenter of Brazil's Congenital Zika Epidemic: Evidence From 87 Confirmed Cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(10):1302–8. 10.1093/cid/cix166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Del Campo M, Feitosa IM, Ribeiro EM, et al. : The phenotypic spectrum of congenital Zika syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2017;173(4):841–57. 10.1002/ajmg.a.38170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Acosta-Reyes J, Navarro E, Herrera MJ, et al. : Severe Neurologic Disorders in 2 Fetuses with Zika Virus Infection, Colombia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(6):982–4. 10.3201/eid2306.161702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sanín-Blair JE, Gutiérrez-Márquez C, Herrera DA, et al. : Fetal Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings in Prenatal Zika Virus Infection. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2017;42(2):153–7. 10.1159/000454860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Schaub B, Vouga M, Najioullah F, et al. : Analysis of blood from Zika virus-infected fetuses: a prospective case series. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(5):520–7. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30102-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Tse C, Picon M, Rodriguez P, et al. : The Effects of Zika in Pregnancy: The Miami Experience [20M]. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:137s-8s 10.1097/01.AOG.0000514691.21416.35 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Aleman TS, Ventura CV, Cavalcanti MM, et al. : Quantitative Assessment of Microstructural Changes of the Retina in Infants With Congenital Zika Syndrome. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(10):1069–76. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.3292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Mejdoubi M, Monthieux A, Cassan T, et al. : Brain MRI in Infants after Maternal Zika Virus Infection during Pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1399–400. 10.1056/NEJMc1612813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Fernandez MP, Parra Saad E, Ospina Martinez M, et al. : Ocular Histopathologic Features of Congenital Zika Syndrome. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2017;135(11):1163–9. 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.3595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Petribu NCL, Aragao MFV, van der Linden V, et al. : Follow-up brain imaging of 37 children with congenital Zika syndrome: case series study. BMJ. 2017;359:j4188. 10.1136/bmj.j4188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Schaub B, Gueneret M, Jolivet E, et al. : Ultrasound imaging for identification of cerebral damage in congenital Zika virus syndrome: a case series. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2017;1(1):45–55. 10.1016/S2352-4642(17)30001-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. James-Powell T, Brown Y, Christie CDC, et al. : Trends of Microcephaly and Severe Arthrogryposis in Three Urban Hospitals following the Zika, Chikungunya and Dengue Fever Epidemics of 2016 in Jamaica. West Indian Med J. 2017;66(1):10–9. 10.7727/wimj.2017.124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Contreras-Capetillo SN, Valadéz-González N, Manrique-Saide P, et al. : Birth Defects Associated With Congenital Zika Virus Infection in Mexico. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2018;57(8):927–36. 10.1177/0009922817738341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Castro JDV, Pereira LP, Dias DA, et al. : Presumed Zika virus-related congenital brain malformations: the spectrum of CT and MRI findings in fetuses and newborns. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2017;75(10):703–10. 10.1590/0004-282X20170134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Mulkey SB, Vezina G, Bulas DI, et al. : Neuroimaging Findings in Normocephalic Newborns With Intrauterine Zika Virus Exposure. Pediatr Neurol. 2018;78:75–8. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2017.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Pires P, Jungmann P, Galvão JM, et al. : Neuroimaging findings associated with congenital Zika virus syndrome: case series at the time of first epidemic outbreak in Pernambuco State, Brazil. Childs Nerv Syst. 2018;34(5):957–63. 10.1007/s00381-017-3682-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Felix A, Hallet E, Favre A, et al. : Cerebral injuries associated with Zika virus in utero exposure in children without birth defects in French Guiana: Case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(51):e9178. 10.1097/MD.0000000000009178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ramos CL, Moreno-Carvalho OA, Nascimento-Carvalho CM: Cerebrospinal fluid aspects of neonates with or without microcephaly born to mothers with gestational Zika virus clinical symptoms. J Infect. 2018;76(6):563–9. 10.1016/j.jinf.2018.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Soares-Marangoni DA, Tedesco NM, Nascimento AL, et al. : General movements and motor outcomes in two infants exposed to Zika virus: brief report. Dev Neurorehabil. 2019;22(1):71–4. 10.1080/17518423.2018.1437843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Howard A, Visintine J, Fergie J, et al. : Two Infants with Presumed Congenital Zika Syndrome, Brownsville, Texas, USA, 2016-2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(4):625–30. 10.3201/eid2404.171545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. De Fatima Viana Vasco Aragao M, Van Der Linden V, Petribu NC, et al. : Congenital Zika Syndrome: Comparison of brain CT scan with postmortem histological sections from the same subjects. Neuroradiology. 2018;60(1 Supplement 1):367–8. [Google Scholar]

- 96. Rosenstierne MW, Schaltz-Buchholzer F, Bruzadelli F, et al. : Zika Virus IgG in Infants with Microcephaly, Guinea-Bissau, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(5):948–50. 10.3201/eid2405.180153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Oliveira-Filho J, Felzemburgh R, Costa F, et al. : Seizures as a Complication of Congenital Zika Syndrome in Early Infancy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98(6):1860–2. 10.4269/ajtmh.17-1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Walker CL, Merriam AA, Ohuma EO, et al. : Femur-sparing pattern of abnormal fetal growth in pregnant women from New York City after maternal Zika virus infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(2):187.e1–187.e20. 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.04.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Peixoto Filho AAA, de Freitas SB, Ciosaki MM, et al. : Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings in infants with microcephaly potentially related to congenital Zika virus infection. Radiol Bras. 2018;51(2):119–22. 10.1590/0100-3984.2016.0135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. De Alcantara T, La Beaud AD, Aronoff D, et al. : CT Scan Findings in Microcephaly Cases During 2015–2016 Zika Outbreak: A Cohort Study. Neurology. 2018;90(15 Supplement 1). Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 101. Cardoso TF, Jr, Santos RSD, Corrêa RM, et al. : Congenital Zika infection: neurology can occur without microcephaly. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104(2):199–200. 10.1136/archdischild-2018-314782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Alves LV, Mello MJG, Bezerra PG, et al. : Congenital Zika Syndrome and Infantile Spasms: Case Series Study. J Child Neurol. 2018;33(10):664–6. 10.1177/0883073818780105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. De Moraes CG, Pettito M, Yepez JB, et al. : Optic neuropathy and congenital glaucoma associated with probable Zika virus infection in Venezuelan patients. JMM Case Rep. 2018;5(5):e005145. 10.1099/jmmcr.0.005145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Figueredo LF, Franco-Zuluaga JA, Carrere-Rivera C, et al. : Anatomical Findings of fetuses Vertically-infected with Zika Virus. FASEB J. 2018;32(1). Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 105. De Alcantara T, Da Silva Maia JT, Aronoff D, et al. : Radiological findings and neurological disorders in microcephaly cases related to zika virus: A cohort study. Neurology. 2018;90(15 Supplement 1). Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 106. Almeida IMLM, Ramos CV, Rodrigues DC, et al. : Clinical and epidemiological aspects of microcephaly in the state of Piauí, northeastern Brazil, 2015-2016. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2019;95(4):466–474. 10.1016/j.jped.2018.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Wongsurawat T, Athipanyasilp N, Jenjaroenpun P, et al. : Case of Microcephaly after Congenital Infection with Asian Lineage Zika Virus, Thailand. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(9):1758–1761. 10.3201/eid2409.180416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Rajapakse NS, Ellsworth K, Liesman RM, et al. : Unilateral Phrenic Nerve Palsy in Infants with Congenital Zika Syndrome. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(8):1422–1427. 10.3201/eid2408.180057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Beaufrere A, Bessieres B, Bonniere M, et al. : A clinical and histopathological study of malformations observed in fetuses infected by the Zika virus. Brain Pathol. 2019;29(1):114–125. 10.1111/bpa.12644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Chu V, Petersen LR, Moore CA, et al. : Possible Congenital Zika Syndrome in Older Children Due to Earlier Circulation of Zika Virus. Am J Med Genet A. 2018;176(9):1882–9. 10.1002/ajmg.a.40378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Vouga M, Baud D, Jolivet E, et al. : Congenital Zika virus syndrome...what else? Two case reports of severe combined fetal pathologies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):356. 10.1186/s12884-018-1998-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. de Noronha L, Zanluca C, Burger M, et al. : Zika Virus Infection at Different Pregnancy Stages: Anatomopathological Findings, Target Cells and Viral Persistence in Placental Tissues. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2266. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Martins RS, Froes MH, Saad LDC, et al. : Descriptive report of cases of congenital syndrome associated with Zika virus infection in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, from 2015 to 2017. Epidemiol Serv Saude. 2018;27(3):e2017382. 10.5123/S1679-49742018000300012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Rodriguez J, Diaz M, Montalvo A, et al. : Case Series: Congenital Zika Virus Infection Associated with Epileptic Spasms. Ann Neurol. 2018;84(Supplement 22):S401–S. 10.1002/ana.25305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Azevedo RSS, Araujo MT, Oliveira CS, et al. : Zika Virus Epidemic in Brazil. II. Post-Mortem Analyses of Neonates with Microcephaly, Stillbirths, and Miscarriage. J Clin Med. 2018;7(12): pii: E496. 10.3390/jcm7120496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Petribu NCL, Fernandes ACV, Abath MB, et al. : Common findings on head computed tomography in neonates with confirmed congenital Zika syndrome. Radiol Bras. 2018;51(6):366–71. 10.1590/0100-3984.2017.0119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Seferovic MD, Turley M, Valentine GC, et al. : Clinical Importance of Placental Testing among Suspected Cases of Congenital Zika Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(3): pii: E712. 10.3390/ijms20030712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Cano M, Esquivel R: Zika virus infection in Hospital del Niño 'Dr José Renán Esquivel' (Panamá): Case Review since the introduction in Latin America. Pediátr Panamá. 2018;47(3):15–9. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 119. de Fatima Viana Vasco Aragao M, van der Linden V, Petribu NC, et al. : Congenital Zika Syndrome: The Main Cause of Death and Correspondence Between Brain CT and Postmortem Histological Section Findings From the Same Individuals. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;28(1):29–33. 10.1097/RMR.0000000000000194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Santana MB, Lamas CC, Athayde JG, et al. : Congenital Zika syndrome: is the heart part of its spectrum? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25(8):1043–4. 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Venturi G, Fortuna C, Alves RM, et al. : Epidemiological and clinical suspicion of congenital Zika virus infection: Serological findings in mothers and children from Brazil. J Med Virol. 2019;91(9):1577–1583. 10.1002/jmv.25504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Lee EH, Cooper H, Iwamoto M, et al. : First 12 Months of Life for Infants in New York City, New York, With Possible Congenital Zika Virus Exposure. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2019; pii: piz027. 10.1093/jpids/piz027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Merriam AA, Nhan-Chang CL, Huerta-Bogdan BI, et al. : A Single-Center Experience with a Pregnant Immigrant Population and Zika Virus Serologic Screening in New York City. Am J Perinatol. 2019. 10.1055/s-0039-1688819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Zambrano H, Waggoner J, Leon K, et al. : High incidence of Zika virus infection detected in plasma and cervical cytology specimens from pregnant women in Guayaquil, Ecuador. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2017;77(2):e12630. 10.1111/aji.12630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Santa Rita TH, Barra RB, Peixoto GP, et al. : Association between suspected Zika virus disease during pregnancy and giving birth to a newborn with congenital microcephaly: a matched case-control study. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):457. 10.1186/s13104-017-2796-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. de Araujo TVB, Ximenes RAA, Miranda-Filho DB, et al. : Association between microcephaly, Zika virus infection, and other risk factors in Brazil: final report of a case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(3):328–36. 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30727-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Moreira-Soto A, Sarno M, Pedroso C, et al. : Evidence for Congenital Zika Virus Infection From Neutralizing Antibody Titers in Maternal Sera, Northeastern Brazil. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(12):1501–4. 10.1093/infdis/jix539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Krow-Lucal ER, de Andrade MR, Cananéa JNA, Moore CA, et al. : Association and birth prevalence of microcephaly attributable to Zika virus infection among infants in Paraíba Brazil, in 201 6: a case-control study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 2018;2(3):205–13. 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30020-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Ventura LO, Ventura CV, Dias NC, et al. : Visual impairment evaluation in 119 children with congenital Zika syndrome. J AAPOS. 2018;22(3):218–22 e1. 10.1016/j.jaapos.2018.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Moreira-Soto A, Cabral R, Pedroso C, et al. : Exhaustive TORCH Pathogen Diagnostics Corroborate Zika Virus Etiology of Congenital Malformations in Northeastern Brazil. mSphere. 2018;3(4): pii: e00278-18. 10.1128/mSphere.00278-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Subissi L, Dub T, Besnard M, et al. : Zika Virus Infection during Pregnancy and Effects on Early Childhood Development, French Polynesia, 2013-2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24(10):1850–8. 10.3201/eid2410.172079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Lima GP, Rozenbaum D, Pimentel C, et al. : Factors associated with the development of Congenital Zika Syndrome: a case-control study. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):277. 10.1186/s12879-019-3908-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Pedroso C, Fischer C, Feldmann M, et al. : Cross-Protection of Dengue Virus Infection against Congenital Zika Syndrome, Northeastern Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25(8):1485–1493. 10.3201/eid2508.190113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Zin AA, Tsui I, Rossetto J, et al. : Screening Criteria for Ophthalmic Manifestations of Congenital Zika Virus Infection. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(9):847–54. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Vercosa I, Carneiro P, Vercosa R, et al. : The visual system in infants with microcephaly related to presumed congenital Zika syndrome. J AAPOS. 2017;21(4):300–4 e1. 10.1016/j.jaapos.2017.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Halai UA, Nielsen-Saines K, Moreira ML, et al. : Maternal Zika Virus Disease Severity, Virus Load, Prior Dengue Antibodies, and Their Relationship to Birth Outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(6):877–83. 10.1093/cid/cix472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Reynolds MR, Jones AM, Petersen EE, et al. : Vital Signs: Update on Zika Virus-Associated Birth Defects and Evaluation of All U.S. Infants with Congenital Zika Virus Exposure - U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(13):366–73. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6613e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Adhikari EH, Nelson DB, Johnson KA, et al. : Infant outcomes among women with Zika virus infection during pregnancy: results of a large prenatal Zika screening program. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(3):292 e1–e8. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Spiliopoulos D, Wooton G, Economides DL, et al. : Surveillance of pregnant women exposed to Zika virus areas. Bjog-Int J Obstet Gy. 2017;124:17–49. 10.1111/1471-0528.14586 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Eppes C, Rac M, Dempster C, et al. : Zika Virus in a Non-Endemic Urban Population: Patient Characteristics and Ultrasound Findings. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:135s-s 10.1097/01.AOG.0000514683.06169.08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Sohan K, Cyrus CA: Ultrasonographic observations of the fetal brain in the first 100 pregnant women with Zika virus infection in Trinidad and Tobago. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;139(3):278–83. 10.1002/ijgo.12313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Kam YW, Leite JA, Lum FM, et al. : Specific Biomarkers Associated With Neurological Complications and Congenital Central Nervous System Abnormalities From Zika Virus-Infected Patients in Brazil. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(2):172–81. 10.1093/infdis/jix261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Ximenes ASFC, Pires P, Werner H, et al. : Neuroimaging findings using transfontanellar ultrasound in newborns with microcephaly: a possible association with congenital Zika virus infection. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32(3):493–501. 10.1080/14767058.2017.1384459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Terzian ACB, Estofolete CF, Alves da Silva R, et al. : Long-Term Viruria in Zika Virus-Infected Pregnant Women, Brazil, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017;23(11):1891–3. 10.3201/eid2311.170078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Nogueira ML, Nery Junior NRR, Estofolete CF, et al. : Adverse birth outcomes associated with Zika virus exposure during pregnancy in São José do Rio Preto, Brazil. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(6):646–52. 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Sanz Cortes M, Rivera AM, Yepez M, et al. : Clinical assessment and brain findings in a cohort of mothers, fetuses and infants infected with ZIKA virus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(4):440 e1–e36. 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Maykin M, Avaad-Portari E, Esquivel M, et al. : Placental Histopathologic Findings in Zika-infected Pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(1):S520–S1. 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.11.411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]