Abstract

Background

Paediatric surgical care is increasingly being centralized away from low‐volume centres, and prehospital delay is considered a risk factor for more complicated appendicitis. The aim of this study was to determine the incidence of paediatric appendicitis in Sweden, and to assess whether distance to the hospital was a risk factor for complicated disease.

Methods

A nationwide cohort study of all paediatric appendicitis cases in Sweden, 2001–2014, was undertaken, including incidence of disease in different population strata, with trends over time. The risk of complicated disease was determined by regression methods, with travel time as the primary exposure and individual‐level socioeconomic determinants as independent variables.

Results

Some 38 939 children with appendicitis were identified. Of these, 16·8 per cent had complicated disease, and the estimated risk of paediatric appendicitis by age 18 years was 2·5 per cent. Travel time to the treating hospital was not associated with complicated disease (adjusted odds ratio (OR) 1·00 (95 per cent c.i. 0·96 to 1·05) per 30‐min increase; P = 0·934). Level of education (P = 0·177) and family income (P = 0·120) were not independently associated with increased risk of complicated disease. Parental unemployment (adjusted OR 1·17, 95 per cent c.i. 1·05 to 1·32; P = 0·006) and having parents born outside Sweden (1 parent born in Sweden: adjusted OR 1·12, 1·01 to 1·25; both parents born outside Sweden: adjusted OR 1·32, 1·18 to 1·47; P < 0·001) were associated with an increased risk of complicated appendicitis.

Conclusion

Every sixth child diagnosed with appendicitis in Sweden has a more complicated course of disease. Geographical distance to the surgical facility was not a risk factor for complicated appendicitis.

This study of all paediatric appendicitis cases among Swedish children reports the incidence of disease. Multivariable analysis was performed to estimate the association between travel time to hospital and the risk of complicated appendicitis, adjusted for socioeconomic determinants of health. Increasing travel time to hospital did not seem to increase the risk of complicated appendicitis.

One in six complicated

Antecedentes

La atención quirúrgica pediátrica está cada vez más centralizada lejos de los centros de bajo volumen, y el retraso pre‐hospitalario se considera un factor de riesgo para las apendicitis más complicadas. El objetivo de este estudio fue determinar la incidencia de apendicitis pediátrica en Suecia y evaluar si la distancia al hospital era un factor de riesgo para una enfermedad complicada.

Métodos

Se analizó un estudio de cohortes a nivel nacional que incluyó todos los casos de apendicitis pediátrica en Suecia durante el periodo 2001‐2014, incluida la incidencia de la enfermedad en diferentes estratos de la población y las tendencias a lo largo del tiempo. El riesgo de enfermedad complicada se determinó mediante métodos de regresión, con el tiempo de viaje como exposición primaria y los determinantes socioeconómicos a nivel individual como variables independientes.

Resultados

Se identificaron 38.939 casos de apendicitis pediátrica. De estos, el 17% eran complicados y el riesgo estimado de apendicitis pediátrica a los 18 años era del 2,5%. El tiempo de viaje al hospital de tratamiento no se asoció con una enfermedad complicada (razón de oportunidades, odds ratio OR ajustada 1,00 (i.c. del 95%: 0,96 a 1,05) por aumentos de 30 minutos, P = 0,93). El nivel de educación (P = 0,18) y los ingresos familiares (P = 0,120) no se asociaron de forma independiente con un aumento del riesgo de enfermedad complicada. El desempleo de los padres (OR ajustada 1,17 (1,05 a 1,32), P = 0,006) y tener padres nacidos fuera de Suecia se asociaron con un mayor riesgo de apendicitis complicada (P < 0,001; un progenitor nacido en Suecia: OR ajustada 1,12 (1,01 a 1,25), ambos progenitores nacidos fuera de Suecia: OR ajustada 1,32 (1,18 a 1,47)).

Conclusión

Uno de cada seis niños diagnosticados de apendicitis en Suecia sufre un curso de enfermedad más complicado. La distancia geográfica al hospital donde se llevó a cabo la cirugía no fue un factor de riesgo para la apendicitis complicada.

Introduction

Paediatric surgical care is increasingly being centralized away from low‐volume centres1, 2, 3. However, the anticipated improvement in quality of treatment for rare diseases may come at the expense of reduced access and longer travel time for the patient, which may have an impact on patients with common diseases. Appendicectomy is the most common abdominal emergency operation in children, and appendicitis perforation rates are frequently used as an indicator of access to surgical care4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9.

Although some authors argue that appendiceal perforation is a result of genetic proclivity10, co‐morbidities11 or microbial profile12, others13 argue that prehospital delay increases the risk of complicated disease. The risk of more complicated disease has been reported to be associated with rural area of residence14, worse insurance and socioeconomic status15 or a lesser degree of connectivity to the healthcare services9. However, these associations have been derived from group‐level socioeconomic status rather than patient‐level data. Furthermore, only a few of these studies included children, and although one14 included travel distance, none considered the estimated travel time to the treating hospital as a possible predictor of perforation risk. As surgical services are increasingly being centralized, the potentially negative effect of travel time on access to an optimal level of care remains important.

The primary aim of this study was to assess how travel distance to hospital was associated with severity of disease, with adjustments for age, sex and socioeconomic determinants of health. A secondary aim was to report adjusted effects of socioeconomic determinants of health on this risk.

Methods

This nationwide cohort study used longitudinal registry data from all Swedish children treated for appendicitis between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2014. There are 21 counties in Sweden, with a total population of 2·0–2·1 million children during the study interval16. In 2015, 99·6 per cent of Swedish citizens lived less than a 2‐h drive from a hospital providing around the clock emergency surgical services (defined by the Lancet bellwether procedures: emergency laparotomy, caesarean section and open fracture repair)17. Although all regional and most local hospitals offer treatment for paediatric appendicitis, the youngest children and those with considerable co‐morbidities are often referred to one of the seven university hospitals, of which four are dedicated paediatric surgery tertiary centres. There are no national guidelines for diagnostic evaluation, referral or treatment of paediatric appendicitis in Sweden, and a family can seek paediatric emergency care directly at secondary or tertiary hospitals without referral via the primary‐care physician. There is one national insurance plan for all Swedish children, and emergency healthcare was available without any direct out‐of‐pocket expenses throughout the entire study period18.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All Swedish children age 0–18 years treated for acute appendicitis (National Inpatient Register, ICD codes K35.0–K37.9) were included in the study. This comprised children admitted for public or private in‐hospital care for a minimum of 1 night, or children treated surgically for appendicitis. Exclusion criteria were: repeat operations, scheduled admissions or elective surgery, suspected misclassification or other unclear procedures that did not fit into any of the predefined treatment regimens.

Data collection

Patients were identified in the National Inpatient Register, which covers more than 99 per cent of public and private inpatient care in Sweden19. The unique personal identity number linked children to parents in the Multi‐Generation Register20. The Labour and Taxation Register21 provided data on place of residence and socioeconomic variables. Annual aggregated data on the Swedish population were collected by age and sex from the Longitudinal Integration Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies (LISA database, Statistics Sweden)22. Annual data on road net and infrastructure were collected from the National Road Database23.

Dependent and independent variables

The primary outcome was severity of appendicitis, classified as uncomplicated or complicated disease. The primary exposure was travel time in minutes from place of residence to the treating hospital. Secondary exposures were highest completed parental education, parental unemployment, household disposable income, governmental support by social security transfers, and parental place of birth. Potential confounders were year of diagnosis of appendicitis, sex, age at diagnosis and county of residence. In the aggregated population‐level data, secondary outcomes were incidence rate of appendicitis, number of treating hospitals and annual appendicitis volume per university hospital or regional/local hospital.

Definitions

Appendicitis severity was classified according to ICD‐1024 as complicated disease (appendicitis with generalized peritonitis or appendicitis abscess; 2001–2009: K35.0–1; 2010–2014: K35.2), or as uncomplicated disease (K35.3–K37.9) (Appendix S1 , supporting information). Diagnostic and procedure codes were specified by the surgeon performing the operation, and included in the discharge record together with the final diagnosis as determined by the clinician responsible for the discharge of the patient. Diagnostic and procedure‐related codes in the discharge record were reported to the National Inpatient Register by administrative staff. Travel time was estimated by the most time‐efficient way by car from the Small Area of Market Studies (SAMS) of the patient's residence to the geo‐coordinates of the treating hospital, measured in minutes as a continuous variable. The population centroid of 0–18‐year‐old inhabitants in each SAMS was used as the origin of travel. The travel time to hospital considered speed limitations, stop signals, left turns and right turns as they were during the year in which appendicitis was diagnosed. Highest level of education achieved was defined by the parent with the highest level and categorized as completion of compulsory school (less than 10 years), high school (0–12 years) or higher education (over 12 years). Unemployment was dichotomized based on registration in the Swedish Public Employment Service for over 150 days. Income was the sum of the parents' disposable income after taxation and transfers the year of treatment of appendicitis, and was categorized into annual quintiles to adjust for inflation and shifts in taxation levels or social transfer regulations over time. Governmental support was dichotomized based on payments of social transfers in the year of diagnosis. Children could have both parents born outside Sweden, one Swedish‐born parent or two Swedish‐born parents. Owing to an ICD‐10 revision, a trend over time variable was defined as before and after 2010 (Appendix S1 , supporting information).

Ethical considerations

Unique personal identity numbers were coded with a key that was available only to the register holder. No patients were identified, and it was not possible to receive the patient involvement statement. Ethical approval was obtained from the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund (2014/792) and approval to access deidentified information on the parents' place of birth and socioeconomic variables was obtained from the Central Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (Ö 18‐2015). The study was reported in compliance with the STROBE guidelines25.

Statistical analysis

Primary outcomes were reported as sex‐ and age‐specific incidence rates per 1000 person‐years and as percentages, with trends over time. The population denominator was the average of the official Swedish population in the specified sex and age group at the beginning and end of each year. New cases of appendicitis were divided by the population at risk in each sex and age group, for each study year. The incidence of appendicitis for each sex and age in each year was calculated, as were the corresponding mean incidences of appendicitis across all years of the study. The risk of paediatric appendicitis until age 18 years with 95 per cent confidence interval was estimated as the cumulative childhood incidence of appendicitis, calculated as the sum of these 1‐year mean incidences. Multivariable Poisson regression models were used to estimate effects of co‐variables, adjusted for changes in age and sex distribution in the population over time, and the revision in ICD‐10. The incidence rate ratios obtained are presented as percentages with 95 per cent confidence intervals. Age and travel time were non‐normally distributed and categorized into 3‐year and 30‐min intervals respectively, and considered as ordered categorical. Primary and secondary exposures are presented with odds ratios (OR) for complicated disease, first by regression analysis with each independent variable adjusted for age, year of treatment and the change in ICD system, and then by a full multivariable logistic regression model. All models were clustered by county of residence, to adjust for possible effects of local variation in the coding of appendicitis. The overall contribution of categorical variables in the regression models was assessed by the F test and reported as P values. Sensitivity analyses were performed to test the robustness of results for variations in health determinant categorization cut‐off values, by altering the categorization of parental education into six levels and travel time into quintiles. Median (i.q.r.) values were calculated for hospital appendicitis volume, and time trends were assessed with linear regression. Proportions and ratios are presented with 95 per cent confidence intervals and 5 per cent (2‐sided) significance level. ArcGIS software (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Redmond, California, USA) was used to estimate travel times26. Statistical analyses were performed in Stata/SE® version 14.1 for Windows® (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Of 40 021 children admitted for public or private in‐hospital care in Sweden for a minimum of 1 night, or treated surgically for appendicitis, 1082 were excluded as they had repeat operations (64 children), scheduled admissions or elective surgery (829), suspected misclassification (2; operative NOMESCO27 procedure code was JFF40 appendicostomy), or other unclear procedures that did not fit into any of the predefined treatment regimens (187) (Table S1 , supporting information).

Incidence of childhood appendicitis

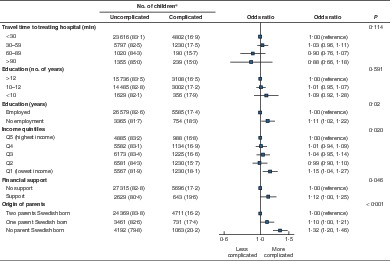

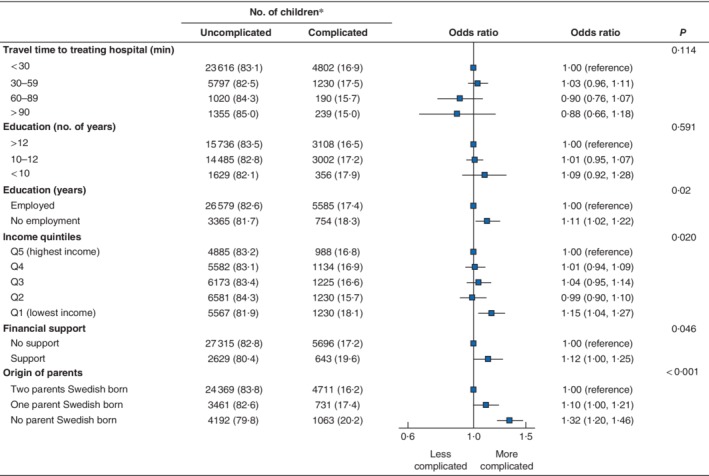

During the 14‐year study interval, 38 939 children were admitted for acute appendicitis in Sweden, corresponding to a childhood incidence of 2·5 per cent. The incidence increased with age (Fig. 1 a), and decreased over time; the adjusted annual decrease was 3·2 (95 per cent c.i. 2·8 to 3·7) per cent (P < 0·001). After adjustment for variations in age and sex over time, the incidence was 27·3 (95 per cent c.i. 24·8 to 29·9) per cent higher among boys than girls (P < 0·001).

Figure 1.

Incidence of appendicitis by age and sex, and complicated and uncomplicated appendicitis by age, among Swedish children, 2001–2014 a Incidence of appendicitis by age and sex. The adjusted incidence rate ratio, obtained from multivariable Poisson regression analysis, increased by 12·8 (95 per cent c.i. 12·6 to 13·0) per cent per added year of age (P < 0·001). b Incidence of complicated and uncomplicated appendicitis by age, and percentage of complicated appendicitis.

Hospitals and caseload volume

Children in Sweden were treated for appendicitis in 64 hospitals, with a median volume of 32 (range 0–415) cases per year. The number of non‐university hospitals providing treatment decreased from 54 early in the study period to 44 in 2014. Over the same interval, the median annual caseload volume in non‐university hospitals decreased from 35 (i.q.r. 19–59) to 24 (7–39) (β = –0·77, 95 per cent c.i. –1·19 to –0·35; P < 0·001). Both the number of university hospitals and their caseload volume remained unchanged throughout the study period (β = –0·38, –5·51 to 4·75; P = 0·884).

Complicated appendicitis

Overall, 16·8 (95 per cent c.i. 16·7 to 17·0) per cent of children had complicated appendicitis; there was no difference between boys and girls (Table S2 , supporting information). This risk peaked in the first years of life (54·3 (38·5 to 70·1) per cent among 1‐year‐olds) and decreased with age (Fig. 1 b). During the study interval, the incidence of both complicated and uncomplicated appendicitis decreased; the annual adjusted decrease was 4·7 (95 per cent c.i. 3·7 to 5·6) per cent (P < 0·001) and 2·9 (2·4 to 3·4) per cent (P < 0·001) respectively.

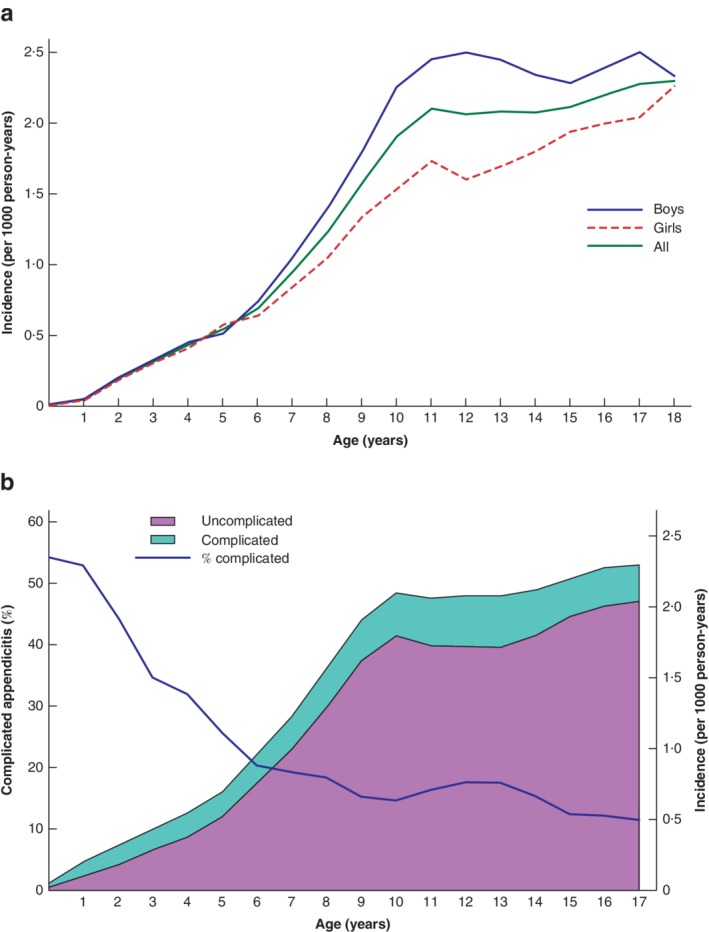

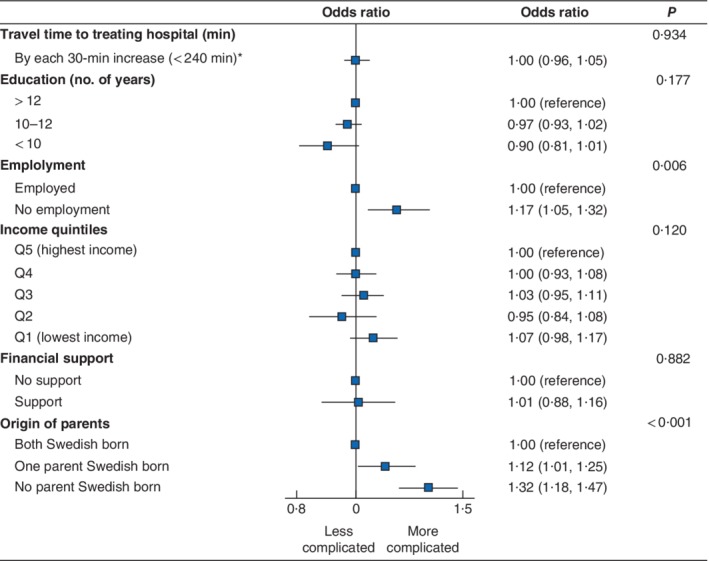

Travel time and socioeconomic determinants

The risk of complicated appendicitis per distance travelled was adjusted by age, sex, year of diagnosis and place of treatment (Fig. 2), socioeconomic determinants (Fig. 3) and ICD‐10 revision. In the full multivariable model with adjustment for all socioeconomic variables and potential confounders, longer travel time to hospital was not associated with more severe appendicitis (adjusted OR 1·00 (95 per cent c.i. 0·96 to 1·05) for each 30‐min increase in travel time; P = 0·934). In the sensitivity analyses, where travel time was evaluated as a non‐ordered categorical variable rather than an ordered categorical variable, a small increase in risk of complicated appendicitis was noted only among children living 10–60 min from surgical facilities (Figs S1 and S2 , supporting information). There remained no independent association between level of education and complicated appendicitis, nor for income or financial support (Fig. 3). Appendicitis among children of employed parents and Swedish‐born parents was associated with lower risk (Fig. 3). These findings were robust in sensitivity analyses with altered health determinant categorization cut‐off values (Figs S1–S3 , supporting information).

Figure 2.

Risk of complicated appendicitis by travel time to treating hospital and by each socioeconomic determinant *Values in parentheses are percentages; odds ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. Regression analyses were adjusted for age, year and the ICD‐10 revision, and stratified by county of treatment.

Figure 3.

Multivariable effect estimates of travel time to treating hospital on risk of complicated appendicitis Odds ratios are shown with 95 per cent confidence intervals. Regression analyses were adjusted for socioeconomic determinants, age, year and the ICD‐10 revision, and stratified by county of treatment. *Cases with an estimated travel time of 240 minutes or more were considered outliers and excluded from the multivariable analysis.

Discussion

This nationwide cohort study of paediatric appendicitis in Sweden showed increased centralization of treatment away from non‐university hospitals, yet increased travel time to the treating hospital was not associated with an increased risk of complicated appendicitis. One in 40 children developed appendicitis during childhood and, even with modern diagnostic and therapeutic tools, every sixth child with appendicitis developed more complicated disease.

The current trend towards centralization of paediatric surgical care for complex and rare conditions to higher‐volume surgical centres may also lead to reduced access and longer travel time for patients with more common diseases1, 2, 3, 28. Local hospital preparedness for surgical care may be a concern particularly for conditions in which patient outcomes depend on timely treatment. As complicated appendicitis has been associated with prehospital delay13, 29, it may be hypothesized that longer travel time to an adequate level of care would increase the risk of complicated disease. This study does not support such a hypothesis. Among earlier reports of an association between rural versus urban place of residence and complicated appendicitis, only one14 considered the distance to hospital, and none estimated the actual travel time for the patient. Furthermore, no previous study has been able to integrate individual‐level health determinants into the analysis of risk14, 30, 31, 32.

The present study represents a comprehensive epidemiological analysis of paediatric appendicitis, with presentation of incidence and disease severity across age groups for boys and girls, description of caseload volume in hospitals, and evaluation of associations between multiple individual‐level health determinants and complicated appendicitis. In the Swedish health insurance system, which provides universal coverage for all children without direct out‐of‐pocket expenses, the level of education and the size of the parental income seemed to be unrelated to the severity of disease in the multivariable analysis. Yet, the results suggest a reduced risk among children whose parents were born within the country, and for children of parents who were working. In addition to language barriers and variable genetic proclivity, these findings could indicate a beneficial effect of stronger ties with social capital, mediated by social networks in the labour market and by gradients of social cohesion to the Swedish society. Associations between income and the risk of complicated appendicitis have been suggested4, 9, 15, 31, but are not supported consistently30, 33. Hence, the lack of an association is most likely related to the universal health coverage with care free of charge. Lee and colleagues33 reported that higher education de facto was associated with an increased risk of complicated appendicitis in adults with equal insurance status33. Even though no such association was seen in the present cohort of children, the same tendency was noticed. Differences from earlier studies may be explained by the fact that socioeconomic effects are context‐specific, but unmeasured confounding factors in earlier studies cannot be ruled out, as most of them relied on proxies for education and income.

The findings of this study must be interpreted within the context of the design. The National Inpatient Register has a diagnostic coverage rate of 99 per cent, and very high accuracy in reported diagnosis19. Previous validations of the National Inpatient Register concluded that almost 100 per cent of inpatient care in Sweden is covered throughout the present study interval (2001–2014). A medical chart review validation of the accuracy in the register was performed specifically for appendicitis in 1994, resulting in a positive predictive value of 90·3 per cent and a negative predictive value of 94·0 per cent, with an accuracy of 91·3 per cent34. Reporting bias may still have been introduced by inadequate coverage or misclassification, but this is not expected to bias the analysis systematically. Notably, the revision of ICD‐10 codes in 2010 influenced how complicated appendicitis was reported to healthcare registers, as the classification switched from an intraoperative determination of appendicitis severity (perforation) to a clinical one (peritonitis); this shift was duly adjusted for in the statistical analysis. Complicated cases tend to gravitate towards university hospitals, giving the impression that longer travel times could be associated with more complicated disease. Such selection bias would be expected to work in the direction towards more complicated disease with increasing travel time. This potential selection bias was insufficiently adjusted for in the present study, suggesting that the negative findings may be even more robust. The Swedish Labour and Taxation Register is linked to the administration of taxes, and its accuracy is expected to be high. However, to some degree incomes may be under‐reported systematically to the taxation register. Categorization of socioeconomic determinants is arbitrary, yet the reported effect estimates of primary and secondary exposures were insensitive to alterations in classification. The analysis of travel time assumed access to a motor vehicle for immediate transport to hospital, which may vary within levels of health determinants. Owing to the study design, causality cannot be claimed even when an association exists, and it cannot be ruled out that trends in appendicitis severity by levels of travel time reflect gradients in incidence of self‐limiting disease, rather than of progressing appendicitis34, 35.

As it is based on a total population of children, a strength of this study is that selection bias is minimized and the internal validity is high. Furthermore, individual‐level health determinants were adjusted for. Yet, socioeconomic determinants of health are context‐specific and not easily comparable between populations. The applicability of these results may therefore be limited to populations where children have low financial barriers to healthcare, and where children are free to seek emergency care at secondary and tertiary hospitals at their discretion. Many high‐income countries provide equally high access to a reliable infrastructure, generally high health literacy, and well equipped hospitals offering proper diagnostic tools and resources. Further studies conducted in other populations and in other healthcare systems are needed to evaluate the generalizability of these results. Previous studies10, 36 have reported variations in incidence and severity of appendicitis across ethnic groups, yet it is unclear whether this effect is related to genetic or social factors. Although ethnicity is not available in the Swedish healthcare registers, nonetheless, the present study has confirmed that place of birth of the parents does correlate with disease severity.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Classification of complicated appendicitis

Table S1. 187 patients diagnosed with appendicitis were treated with procedures that could not be classified into any of the pre‐defined treatment regimens, and were therefore excluded.

Table S2. Swedish children admitted to inpatient care for their first episode of appendicitis. All Swedish children 0‐18 years of age were eligible for inclusion.

Fig. S1. Multivariable effect estimates of travel time to treating hospital on the risk of complicated appendicitis, adjusted for age and year, and stratified by county of treatment. Travel time as categorical variable.

Fig. S2. Sensitivity analysis: Multivariable effect estimates of travel time to treating hospital on the risk of complicated appendicitis, adjusted for socioeconomic determinants, age and year, and stratified on county of treatment. Travel time categorized as quintiles.

Fig. S3. Sensitivity analysis: Multivariable effect estimates of travel time to treating hospital on the risk of complicated appendicitis, adjusted for socioeconomic determinants, age and year, and stratified on county of treatment. Education categorized in six levels, as determined by both parents' highest level of education.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge data management provided by C. Näslund, statistical guidance from A. Åkesson, and the services provided by Statistics Sweden and the Swedish Board of Health and Welfare in retrieving data. This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Society of Medicine, Anna Lisa and Sven‐Eric Lundgren Foundation for Medical Research, and by ALF project and educational grants from Lund University and Skåne Region (L.H., E.O.). The funders were not involved in planning and designing the study, analysing or interpreting data, or in writing the manuscript and the decision to publish the results. No preregistration exists for the studies reported in this article.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Presented to the European Paediatric Surgeons' Association Congress, Belgrade, Serbia, June 2019

References

- 1. Salazar JH, Goldstein SD, Yang J, Gause C, Swarup A, Hsiung GE et al Regionalization of pediatric surgery: trends already underway. Ann Surg 2016; 263: 1062–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. França UL, McManus ML. Trends in regionalization of hospital care for common pediatric conditions. Pediatrics 2018; 141: e20171940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. França UL, McManus ML. Outcomes of hospital transfers for pediatric abdominal pain and appendicitis. JAMA Netw Open 2018; 1: e183249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Braveman P, Schaaf VM, Egerter S, Bennett T, Schecter W. Insurance‐related differences in the risk of ruptured appendix. N Engl J Med 1994; 331: 444–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gadomski A, Jenkins P. Ruptured appendicitis among children as an indicator of access to care. Health Serv Res 2001; 36: 129–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O'Toole SJ, Karamanoukian HL, Allen JE, Caty MG, O'Toole D, Azizkhan RG et al Insurance‐related differences in the presentation of pediatric appendicitis. J Pediatr Surg 1996; 31: 1032–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ponsky TA, Huang ZJ, Kittle K, Eichelberger MR, Gilbert JC, Brody F et al Hospital‐ and patient‐level characteristics and the risk of appendiceal rupture and negative appendectomy in children. JAMA 2004; 292: 1977–1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scott JW, Rose JA, Tsai TC, Zogg CK, Shrime MG, Sommers BD et al Impact of ACA insurance coverage expansion on perforated appendix rates among young adults. Med Care 2016; 54: 818–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baxter KJ, Nguyen HTMH, Wulkan ML, Raval MV. Association of health care utilization with rates of perforated appendicitis in children 18 years or younger. JAMA Surg 2018; 153: 544–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Terlinder J, Andersson RE. Incidence of appendicitis according to region of origin in first‐ and second‐generation immigrants and adoptees in Sweden. A cohort follow‐up study. Scand J Gastroenterol 2016; 51: 111–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Salö M, Gudjonsdottir J, Omling E, Hagander L, Stenström P. Association of IgE‐mediated allergy with risk of complicated appendicitis in a pediatric population. JAMA Pediatr 2018; 172: 943–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Swidsinski A, Dörffel Y, Loening‐Baucke V, Theissig F, Rückert JC, Ismail M et al Acute appendicitis is characterised by local invasion with Fusobacterium nucleatum/necrophorum . Gut 2011; 60: 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Temple CL, Huchcroft SA, Temple WJ. The natural history of appendicitis in adults. A prospective study. Ann Surg 1995; 221: 278–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Penfold RB, Chisolm DJ, Nwomeh BC, Kelleher KJ. Geographic disparities in the risk of perforated appendicitis among children in Ohio: 2001–2003. Int J Health Geogr 2008; 7: 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bratu I, Martens PJ, Leslie WD, Dik N, Chateau D, Katz A. Pediatric appendicitis rupture rate: disparities despite universal health care. J Pediatr Surg 2008; 43: 1964–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Statistiska centralbyrån (Statistics Sweden) . Population by Region, Marital Status, Age and Sex. Year 1968–2014 http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/?rxid=e0690a76-b047-42b0-96f2-7b7c9125c5f7 [accessed 23 Ocober 2018].

- 17. Ng‐Kamstra JS, Raykar NP, Lin Y, Mukhopadhyay S, Saluja S, Yorlets R et al. Data for the Sustainable Development of Surgical Systems: a Global Collaboration; 2015. http://www.lancetglobalsurgery.org/indicators [accessed 13 May 2019].

- 18. Anell A. The public–private pendulum – patient choice and equity in Sweden. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, Feychting M, Kim JL, Reuterwall C et al External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011; 11: 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Statistiska centralbyrån (Statistics Sweden) . Multi‐Generation Register https://www.scb.se/vara-tjanster/bestalla-mikrodata/vilka-mikrodata-finns/individregister/flergenerationsregistret/ [accessed 5 January 2019].

- 21. Statistiska centralbyrån (Statistics Sweden) . Labour and Taxation Register https://www.scb.se/vara-tjanster/bestalla-mikrodata/vilka-mikrodata-finns/individregister/inkomst--och-taxeringsregistret-iot/ [accessed 23 October 2019].

- 22. Statistiska centralbyrån (Statistics Sweden) . Longitudinal Integration Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies (LISA) https://www.scb.se/en/services/guidance-for-researchers-and-universities/vilka-mikrodata-finns/longitudinella-register/longitudinal-integrated-database-for-health-insurance-and-labour-market-studies-lisa/ [accessed 5 January 2019].

- 23. Trafikverket . Road Data Overview. Version 2.0; 2015. http://www.nvdb.se/globalassets/upload/styrande-och-vagledande-dokument/eng/road-data-overview.pdf [accessed 13 May 2019].

- 24. WHO . ICD10 – Version: 2016 https://icd.who.int/browse10/2016/en [accessed 13 May 2019].

- 25. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies; 2007. http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/strobe/ [accessed 13 May 2019]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26. Environmental Systems Research Institute . ArcGIS 10.3.1. Environmental Systems Research Institute: Redlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nordic Medico‐Statistical Committee (NOMESCO) . NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures (NCSP), Version 1.16. NOMESCO: Copenhagen, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28. França UL, McManus ML. Availability of definitive hospital care for children. JAMA Pediatr 2017; 171: e171096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kim M, Kim SJ, Cho HJ. Effect of surgical timing and outcomes for appendicitis severity. Ann Surg Treat Res 2016; 91: 85–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smink DS, Fishman SJ, Kleinman K, Finkelstein JA. Effects of race, insurance status, and hospital volume on perforated appendicitis in children. Pediatrics 2005; 115: 920–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lin KB, Lai KR, Yang NP, Chan CL, Liu YH, Pan RH et al Epidemiology and socioeconomic features of appendicitis in Taiwan: a 12‐year population‐based study. World J Emerg Surg 2015; 10: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hernandez MC, Finnesgaard E, Aho JM, Kong VY, Bruce JL, Polites SF et al Appendicitis: rural patient status is associated with increased duration of prehospital symptoms and worse outcomes in high‐ and low‐middle‐income countries. World J Surg 2018; 42: 1573–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee SL, Shekherdimian S, Chiu VY. Effect of race and socioeconomic status in the treatment of appendicitis in patients with equal health care access. Arch Surg 2011; 146: 156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Andersson R, Hugander A, Thulin A, Nyström PO, Olaison G. Indications for operation in suspected appendicitis and incidence of perforation. BMJ 1994; 308: 107–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Andersson RE. Does delay of diagnosis and treatment in appendicitis cause perforation? World J Surg 2016; 40: 1315–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Aarabi S, Sidhwa F, Riehle KJ, Chen Q, Mooney DP. Pediatric appendicitis in New England: epidemiology and outcomes. J Pediatr Surg 2011; 46: 1106–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Classification of complicated appendicitis

Table S1. 187 patients diagnosed with appendicitis were treated with procedures that could not be classified into any of the pre‐defined treatment regimens, and were therefore excluded.

Table S2. Swedish children admitted to inpatient care for their first episode of appendicitis. All Swedish children 0‐18 years of age were eligible for inclusion.

Fig. S1. Multivariable effect estimates of travel time to treating hospital on the risk of complicated appendicitis, adjusted for age and year, and stratified by county of treatment. Travel time as categorical variable.

Fig. S2. Sensitivity analysis: Multivariable effect estimates of travel time to treating hospital on the risk of complicated appendicitis, adjusted for socioeconomic determinants, age and year, and stratified on county of treatment. Travel time categorized as quintiles.

Fig. S3. Sensitivity analysis: Multivariable effect estimates of travel time to treating hospital on the risk of complicated appendicitis, adjusted for socioeconomic determinants, age and year, and stratified on county of treatment. Education categorized in six levels, as determined by both parents' highest level of education.