Abstract

Background:

In 2013, Texas House Bill 2 (HB 2) placed restrictions on the use of medication abortion, which later were nullified with the 2016 FDA-approved mifepristone label.

Methods:

Using data collected directly from Texas abortion facilities, we evaluated changes in the provision and use of medication abortion during three six-month time periods corresponding to the policy changes: before HB 2, after HB 2, and after the label change.

Results:

Medication abortion constituted 28% of all abortions before HB 2, 10% after implementation of the restrictions, and 33% after the label change.

Conclusions:

Use of medication abortion in Texas rebounded after the FDA label change.

Keywords: Medication abortion, Mifepristone, Abortion restrictions, Texas, House Bill 2

1. Introduction

Before 2013, use of medication abortion in Texas mirrored national trends [1], which has steadily increased since the approval of mifepristone in 2000 [2]. However, House Bill 2 (HB 2), which was implemented on November 1, 2013, imposed restrictions on medication abortion and required providers to follow the outdated mifepristone label. HB 2 reduced the gestational age limit to 49 days and generally required four visits. In the first six months following the law, there was a 70% decrease in medication abortions [3], likely due to the medication abortion restrictions, as well as clinic closures [4] and confusion about the legality of abortion [5].

On March 29, 2016, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a revised label for Mifeprex® (mifepristone 200 mg) that reflected evidence-based practice [6], which essentially nullified the medication abortion restrictions in HB 2. The updated label increased the window of eligibility for medication abortion to 70 days’ gestation, specified a revised regimen, and removed the requirement for a visit to receive misoprostol. We aimed to assess how this change impacted Texas women’s access to and use of medication abortion.

2. Material and methods

In order to rapidly evaluate policy changes in Texas, we collected monthly data directly from licensed, non-hospital abortion facilities. We focused on three 6-month time periods: Period 1: November 2012-April 2013 (before enforcement of HB 2), Period 2: November 2013-April 2014 (after enforcement of HB 2), and Period 3: November 2017-April 2018 (after FDA approval of updated mifepristone label).

We requested monthly data on the total number of abortions, type of abortion (medication or surgical), and gestational age (<12 weeks, ≥12 weeks’ gestation) directly from licensed facilities that were providing abortion services between November 2012 and April 2018. In summer 2014, facilities provided retrospective data for Periods 1 and 2 based on clinic records, or physician estimates when necessary. Starting in January 2017, we launched an online, encrypted platform using Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) where providers could upload aggregate data each month.

For Period 1 and Period 2, we received complete data from 36 of 41 facilities, which represented 89% of estimated abortions in Texas. For Period 3, clinic staff from 16 of 21 open facilities uploaded data through the online encrypted platform or shared the data through direct correspondence. These clinics provided approximately 93% of the total abortions for the period. For non-participating facilities in any period, we made estimates according to methods previously reported [3]. We relied on knowledgeable sources, such as other providers in their community, or estimated monthly totals based on data available for other recent periods for which we had information or used the volume of other providers in the area. Our estimates to date are largely consistent with state vital statistics on the number and percentage change in abortions over the same period [7].

We tracked the number of facilities providing medication abortion and calculated the percentage of abortions that were medication abortion in each of the three periods. We considered facilities as open if they provided services for at least three of the six months in a time period; similarly, we counted facilities as offering medication abortion if they offered the method for at least three months in a time period. The Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas at Austin determined that this study did not require their review or oversight.

To both complement and validate our own data, we used publicly-available abortion statistics from the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) for 2012 to 2016 [1] to assess trends in medication abortion before and within the three time periods. We calculated the proportion of all abortions that were medication abortions for each year.

3. Results

Medication abortion was provided by 34 of 41 open facilities in Period 1, 14 of 27 in Period 2, and 20 of 21 in Period 3.

In Period 1, medication abortions accounted for 28% of all abortions and 32% (9,948/30,646) of abortions under 12 weeks gestation (Table 1). In Period 2, medication abortion was 10% of all abortions and 11% (2,991/26,522) of abortions under 12 weeks. During Period 3, medication abortion represented 33% of all abortions and 37% (9,521/25,726) of abortion under 12 weeks. There was a 3-fold increase in medication abortion between Period 2 and Period 3 (p<0.01).

Table 1.

Abortion facilities and provision of medication abortion at three time points1

| Period 1: Nov 2012-Apr 2013 |

Period 2: Nov 2013- Apr 2014 |

Period 3: Nov 2017-Apr 2018 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of open abortion facilities2 | 41 | 27 | 21 |

| Number of facilities providing medication abortion3 | 34 | 14 | 20 |

| Total number of abortions | 35,415 | 30,800 | 29,260 |

| Number of abortions <12 weeks | 30,646 | 26,522 | 25,726 |

| Number of medication abortions (percent of total abortions) | 9,948 (28.1%) | 2,991 (9.7%) | 9,521 (32.5%)4 |

Data source: Texas Policy Evaluation Project

Facilities that provided services for at least 3 months

Facilities that provided medication abortion for at least 3 months

χ2 p value <0.01 for the proportion of all abortions that were medication abortion in Period 2 vs Period 3.

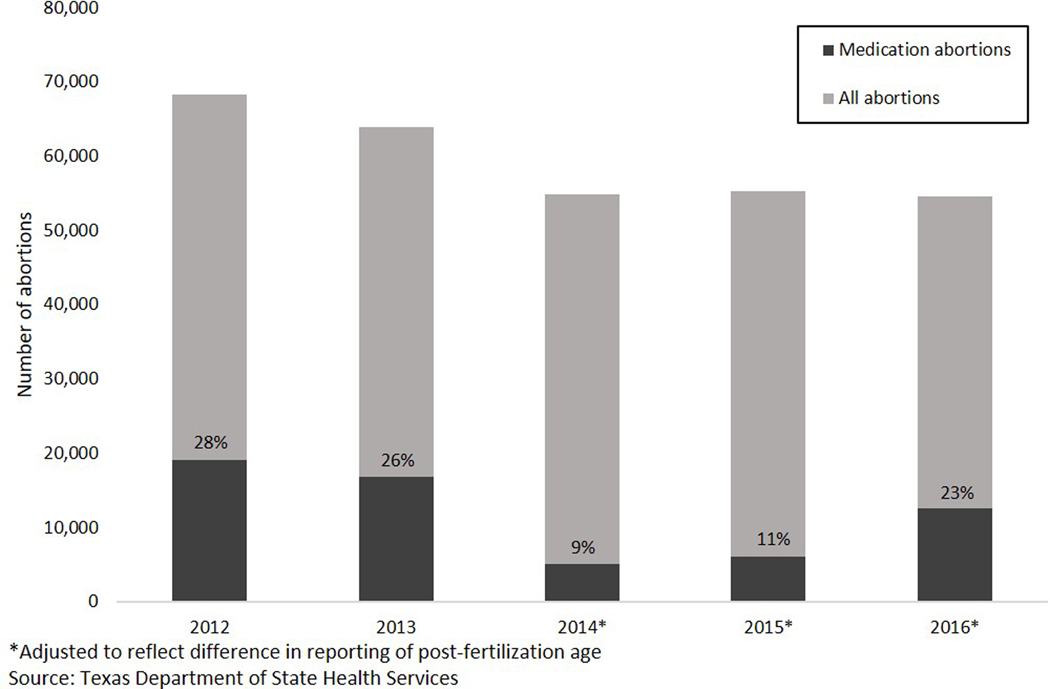

According to Texas DSHS vital statistics, abortion numbers for the calendar years during the period when the medication abortion restrictions were in effect were similar; medication abortion represented 9% of all abortions in 2014 and 11% in 2015 (Figure 1). In 2016, when the label change occurred, use of medication abortion increased and accounted for 23% of all abortions.

Figure 1.

Total abortions and medication abortions from 2012 to 2016 from state vital statistics data

4. Discussion

Prior research has documented the decline of medication abortion following state-level mifepristone restrictions in Texas and Ohio [3,8]. This study provides evidence that the 2016 FDA label change largely nullified the medication abortion restrictions of HB 2 and in the following year, medication abortion accounted for approximately 33% of all abortions, in line with national statistics [2]. In fact, a higher proportion of all abortion clients obtained medication abortion from November 2017 to April 2018 compared to before enforcement of HB 2. Our findings are corroborated by state vital statistics that demonstrate consistently low medication abortion numbers throughout 2014 and 2015 when providers were required to follow the old FDA label.

Now that providers can follow evidence-based guidelines, they may be more willing to offer this method. Eligible clients may be more likely to obtain a desired medication abortion due to fewer required visits and expanded gestational age limits. Despite these improvements, women continue to face barriers accessing medication abortion in Texas, including long travel distance to the nearest facility, a ban on telemedicine for the provision of medication abortion [9], a mandatory ultrasound during an in-person visit at least 24 hours before the procedure [10], and lack of insurance coverage for abortion [11].

This study also demonstrates the value and feasibility of collecting real-time data directly from abortion facilities. Because we had developed trusted relationships with providers throughout the state, we were able to work with facilities and identify changes sooner than would have been possible with state vital statistics; data for calendar year 2016 was not available until September 2018. Women continue to face medication abortion restrictions in other states, such as Arkansas and Missouri, and the rapid data collection approach used here could be adopted elsewhere to monitor the impact of these laws on women’s access to care.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation, as well as center grant P2C HD042849 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

References

- [1].Texas Department of State Health Services. Vital Statistics Annual Reports 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jones RK, Jerman J. Abortion Incidence and Service Availability In the United States, 2014. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2017;49:17–27. doi: 10.1363/psrh.12015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Grossman D, Baum S, Fuentes L, White K, Hopkins K, Stevenson A, et al. Change in abortion services after implementation of a restrictive law in Texas. Contraception 2014;90:496–501. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gerdts C, Fuentes L, Grossman D, White K, Keefe-Oates B, Baum S, et al. The impact of clinic closures on women obtaining abortion services after implementation of a restrictive law in Texas. Am J Public Health 2016;106:857–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fuentes L, Lebenkoff S, White K, Gerdts C, Hopkins K, Potter JE, et al. Women’s experiences seeking abortion care shortly after the closure of clinics due to a restrictive law in Texas. Contraception 2016;93:292–7. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].US Food and Drug Administration. MIFEPREX (mifepristone) tablets label 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Grossman D. The Use of Public Health Evidence in Whole Woman’s Health v Hellerstedt. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:155–6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sheldon WR, Winikoff B. Mifepristone label laws and trends in use: recent experiences in four US states. Contraception 2015;92:182–5. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Texas Constitutions and Statutes. OCC § 111.005 (2017).

- [10].Health & Safety § 171.012 (2011).

- [11].Texas Constitutions and Statutes. TX INS § 1218 (2017).