Abstract

Previous descriptions of the composition and stability of children’s households have focused on the presence of parents and the stability of mothers’ marital and cohabiting relationships. We use data available in the 2008 Survey of Income and Program Participation to expand the description of children’s household composition and stability. We find that one in five children lives with nonnuclear household members. These other household members are a source of substantial household instability. In addition, during the period of observation (2008– 2013), children experienced considerable residential instability. Thus, children’s experience of household instability is much more common and frequent than previously documented. Moreover, levels of both residential and compositional instability are higher for children with less-educated mothers and for racial/ethnic minorities.

Keywords: Children, Households, Race, Education, Kin

Introduction

Most studies of children’s family structure and family instability have focused on the formation and dissolution of mothers’ marital and cohabiting relationships. Yet, other adults and children can contribute to family life and to changes in household composition. An emerging body of research has shown that a large and growing proportion of children live with nonnuclear kin (Pilkauskas and Cross 2018). Nearly 11 % of children live with a grandparent, and 15 % live with any extended kin (Kreider and Ellis 2011). An even larger proportion (19.5 %) live in shared households with nonnuclear kin or nonrelatives (Mykyta and Macartney 2012). Of course, estimates of the prevalence of coresidence with kin understate its incidence. Nearly one-third of children live with a grandparent between birth and age 18 (Amorim et al. 2017), and even more (35 %) experience extended family structure (Cross 2018). Extended households tend to be unstable (Glick and Van Hook 2011; Pilkauskas 2012), and thus children are more likely to experience an extended family member enter or exit their household than they are to see a parent or parent’s partner come or go (Perkins 2017).

The family instability literature tends to focus on nonnormative family instability— specifically, parental divorce and remarriage. Yet older children experience the birth of their siblings, and younger children experience the exit of older siblings in their transition to adulthood. Further, many children experience residential instability, sometimes without any accompanying change in household composition. Similar to parental divorce and remarriage, these changes might be stressful, disrupt routines, and alter the resources available to children (Astone and McLanahan 1994; Fomby and Mollborn 2017; Fomby and Sennott 2013).

Family instability, operationalized as changes in mothers’ coresidential unions, is associated with, and is likely a cause of, poorer child outcomes (Cavanagh and Fomby forthcoming). Racial/ethnic minorities and children with less-educated mothers experience more family instability due to maternal cohabitation and divorce than do white children or those with college-educated mothers (Brown et al. 2016; Rackin and Gibson-Davis 2018). Socioeconomically disadvantaged children also more often live with extended family (Cross 2018), and poverty is associated with more residential instability (Geist and McManus 2008). Family instability is associated with the downward mobility of children relative to their parents. In this way, household stability may also be an important mechanism for the transmission of economic advantage across generations (Bloome 2017).

This research builds on work on extended household instability in three ways. First, family instability research has often produced evidence suggesting that repeated family transitions cumulate to negatively impact child development. This is one reason why prior work produced estimates of cumulative number of marital or union transitions children experience (Brown et al. 2016; Rackin and Gibson-Davis 2018; Raley and Wildsmith 2004). Perkins (2017) determined that 20 % of children experience any household instability over a two-year period. Our analysis produces estimates of the amount of household instability children experience. Second, our measure of household instability is broader, including sibling transitions as well as residential instability. This conceptual and measurement extension may open opportunities for understanding better why family or household instability is associated with poorer child outcomes. Third, given pronounced differences in family histories by race/ethnicity and maternal education, we produce estimates of household instability by race/ethnicity and parental education. To achieve these goals, we use data from the 2008 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP).

Background

Children’s Family and Household Instability

Family patterns of the second half of the twentieth century increased the proportion of children who experienced parental divorce and single-parent families. This spawned an enormous research literature on the effects of single parent families on child development. Early theories posited that father absence was key to the poorer outcomes of children who experienced parental divorce. Yet, empirical findings showed that children from remarried parent families did as poorly as those whose mothers never remarried (McLanahan and Sandefur 1994; Wu and Martinson 1993). Remarriage increased the resources available to divorced mothers and their children, but these benefits were offset by the additional disruption of remarriage.

These findings led researchers to develop and test theories about how family instability contributed to child development (Cavanagh and Huston 2006; Coleman et al. 2000; Fomby and Cherlin 2007). Some of this association is due to selection of women with fewer resources into less stable relationships, but some is likely due to the effects of family instability on children (McLanahan et al. 2013). Family stress theory argues that parental divorce, remarriage, and parental cohabiting transitions contribute to poorer behavioral and cognitive outcomes by upsetting family routines and exposing children to conflict and other sources of stress (Amato 2000). The movement of partners and children in and out of the home can disrupt household routines, undermine maternal health, and lead to inconsistent parenting (Cavanagh and Huston 2006; Lee and McLanahan 2015; Waldfogel et al. 2010). Family instability can also lead to frequent moves, which may hinder child development (Astone and McLanahan 1994; Fomby and Mollborn 2017; Fomby and Sennott 2013). Thus, family demographers began tracking trends in children’s family experiences, including the experience of family instability (Brown et al. 2016; Raley and Wildsmith 2004).

The family instability literature emerged from a line of stratification research investigating intergenerational transmission of status attainment. In these origins, it theorized that deviations from the normative nuclear family structure would hinder educational attainment, often operationalizing this deviation with a variable labeled broken family (e.g., Duncan 1967; Hauser and Featherman 1976). Researchers have since ceased using such value-laden terms to describe single-parent families, but the mental model remains. This has limited investigations of household instability in two ways. First, the relevant aspect of family structure is the presence or absence of nuclear family members, specifically fathers, who normatively live with their minor children. Yet, as noted in the Introduction, households with children often include other kin as well as nonrelatives. The movement of these kin or kin-like individuals could also introduce stress into the household, disrupting household routines in ways that are potentially meaningful for child development.

Second, normal instability is not viewed as potentially problematic, but household instability may produce stress even when it is normative. The birth of a younger sibling, for example, disrupts routines and is a source of stress for everyone in the household. Older siblings exiting to form their own household, or coming back in, also change household dynamics. Whether siblings coming and going are as consequential for child development as parental divorce and remarriage remains an open question. It could be that normative transitions, such as the birth of a sibling, are more socially supported and anticipated than the nonnormative transitions of biological and social fathers and thus are less consequential. Transitions of fathers may be especially relevant to child well-being given that parents are primary caretakers of children and that the role of social fathers is ambiguous, especially when their relationship with the mother is tenuous. Being normative, the birth of a sibling within a married-parent family produces no similar ambiguities but is chaotic nonetheless. Incorporating these diverse forms of household instability can enable researchers to test theories about why household instability is consequential for child development. A first step toward that goal is to know the amount and types of household instability children experience.

Social Class and Racial/Ethnic Differences

Today, family and household experiences are strongly differentiated by social class (McLanahan 2004) and race/ethnicity (Raley et al. 2015). Divorce rates for college-educated women dropped precipitously in the 1980s but remained high for women with no more than a high school diploma (Martin 2006; Raley and Bumpass 2003). Women across the socioeconomic spectrum are delaying marriage, but increases in age at marriage and the proportion never marrying are higher for less-educated women (Martin et al. 2014). Nonmarital fertility has also increased substantially but continues to be uncommon among college-educated women (Gibson-Davis and Rackin 2014). Racial/ethnic differences in marriage, divorce, and nonmarital fertility are also large. Black and Hispanic women are less likely to marry and more likely to divorce than non-Hispanic white women (Raley et al. 2015). Nonmarital fertility is less common among whites than among blacks or Hispanics (Sweeney and Raley 2014). Altogether, these differences have led to dramatically different levels of family instability—as measured by maternal partnership transitions—for children by maternal education (Rackin and Gibson-Davis 2018) and race/ethnicity (Brown et al. 2016).

Different patterns of marriage and nonmarital fertility are only one aspect of social experience that contributes to greater household instability among disadvantaged groups. Living with extended kin is a more common experience among racial/ethnic minority and low– socioeconomic status children (Amorim et al. 2017; Cross 2018; Desmond 2012). Asians, Hispanics, and African Americans have cultural traditions that make living with grandparents and other extended kin more normative than is the case for those of Western European descent; structural factors, such as lower incomes and recent migration status, also contribute (Kamo 2000; Van Hook and Glick 2007). Household extension increases the risk of household instability (Perkins 2017; Van Hook and Glick 2007).

In addition, racial bias among landlords and other discriminatory practices hinder minority attainment of secure housing in desirable locations (Dreier et al. 2001; Sharkey 2008; Turner et al. 2002). Renters in poor urban neighborhoods face high rates of residential instability because of forced relocation (Desmond et al. 2015). Thus, disadvantaged groups experience not only greater marital instability but also more residential instability and more instability in household composition.

These different forms of household instability are related but distinct. Residential instability is often accompanied by changes in family composition (Desmond and Perkins 2016; Fomby and Sennott 2013), but children can and do experience a change in household composition with no residential move and vice versa. Residential instability may compound the effects of compositional instability (Perkins 2018). Yet even if it does not, in combination with other forms of household instability, residential instability can produce chronic instability, a dimension of the home environment also associated with poorer child outcomes (Fomby and Mollborn 2017).

Our analysis builds on prior work to show class and racial/ethnic variation in the amount of household instability experienced during childhood, measured more inclusively. Household extension is more common for children in single-parent families than for those in two-parent families (Perkins 2017). The strong and growing association between single-parenting and socioeconomic status, combined with the greater residential instability of lower income and racial minority families, leads us to expect that class variation in the amount household instability is likely even greater than variation in family instability due to parental divorce and remarriage.

We begin by describing children’s coresidence with nonrelatives as well as nonnuclear kin to provide context for understanding household instability. Our analyses next estimate the number of household changes that children typically experience before their 18th birthday, distinguishing changes in household membership from changes in address. Instability is further broken down by relationship type. Instability due to a parent moving into or out of the child’s house is differentiated from that due to a sibling or nonnuclear household member. We conduct these analyses for the full sample and then separately by race/ethnicity and maternal education.

Method

We use data from longitudinally collected household rosters from the 2008 SIPP, a nationally representative sample of households interviewed every four months for five years. Data were collected from September 2008 to August 2013, in 15 waves of interviews conducted four months apart. We do not use data from Wave 16 because of missing data in Rotation 2 resulting from a federal government shutdown. The first wave of interviews collected information on 105,663 people living in 42,030 households. Over the course of the panel, the survey collected data on more than 130,000 people as individuals in originally sampled households established new households and others joined sampled households. Our analyses focus on the 37,069 children who appear at least once in a SIPP household at ages 0–17. Missing data across survey waves are substantial. Of the 105,663 individuals observed in the first wave, only 40,524 (38 %) were observed at every interview until Wave 15. We discuss our strategies for addressing missing data later.

Measures

Every interview collected a roster of household members, and each member of the household has a unique identifier. For each individual in the household, we have information on age, race, ethnicity, gender, nativity, education, and relationship to householder. Every individual has two parent pointers that identify all parent-child relationships in the household (including stepparents and adoptive parents) and one spouse pointer to identify all married couples. A person is coded as a parent of a child if she/he is identified by a parent pointer or if she/he is married to or cohabiting with a person who is identified as a parent. We are unable to distinguish full from half- or stepsiblings. The redesigned 2014 SIPP will make identifying such relationships possible, but only the first two waves of the 2014 panel are currently publicly available.

Using the available information, we create measures describing the relationship between each child to every other household member in two rounds of calculations. In the first round, we use the variable describing each members’ relationship to householder along with parent and spouse pointers to determine direct relationships. The second round identifies transitive relationships. For example, if person A is coded as the child of the householder B, and person C is coded as the stepchild of the householder B, we code C as the sibling of A. Or, if A is child of B, and B is spouse/partner of C, then C is parent of A. We are able to identify the relationship of most (99 %) household members to children in using this approach. In less than 1 % of the cases, we are unable to identify a child’s relationship to another household member in a wave. For example, if the child and the other household member are both nonrelatives of the householder, we do not know whether they are related.

We check our transitive approach to determining relationships by comparing our relationship measure in Wave 2 with one based on the household relationship matrix collected in the topical module for that wave. The two measures agree for 98 % of the relationships. Our approach performs least well for relationships coded as nonrelative in the topical module for two reasons. First, as mentioned earlier, a weakness of the transitive approach to determining relationships is that if two people are unrelated to the householder, we cannot know whether they are related to each other. By comparing with the relationship matrix measure, we know that for most (85 %) of the cases in which we cannot determine the relationship for two people, they are not related. Thus, we code these undetermined relationships as nonrelatives. Second, we code the child of a partner as a child of self, analogous to the assumptions made when researchers use maternal marital-cohabitation histories to determine children’s experience of family instability. The relationship variable has five categories: parent, sibling, grandparent, other relative, and nonrelative.

Our measure of compositional change captures any change in household membership by comparing the sets of unique identifiers in consecutive waves. Compositional change equals 1 when a child moves out of a household and leaves at least some members behind or when other members move in. Address change indicates whether an individual’s address changed between interviews. An overall measure, household change, includes both compositional and address changes. Additional measures allow us to break composition change into change involving parents, siblings, or other nonnuclear household members.

Many SIPP respondents missed one or more interviews. Wave 1 collected data on 105,663 original sample members (27,119 children). The maximum possible number of observed intervals for original sample members is 1,479,282 (105,663 × 14), but we have data on only 1,004,104 (67 %). Among original children, we have data on a similar proportion (66 %) of potential intervals.

We can categorize the 475,178 missing intervals into two groups. In one group, the whole household goes missing because everyone in a household refused to be interviewed or was impossible to locate for one or move waves. This was the case for 420,757 (89 %) of the missing intervals. In the second, smaller group, only some of the people in the household go missing. This would happen if some household members moved out and could not be interviewed. It also happens by design: children younger than age 15 are not followed when they no longer live with a SIPP member 15 years old or over. For example, if a child were originally observed in his mother’s household, and he went to live with his father, he would not be included after he moved to his father’s household. Despite the difference in treatment, the proportion of missing observations in the first group is similar for original children (88 %) as it is for the whole sample.

Missing data have the potential to downwardly bias our results if missingness is associated with household instability, and missing intervals are simply dropped from the analysis. Supporting this intuition, we find that individuals with at least some missing data are more likely to have experienced composition changes in fully observed intervals than individuals with complete data. The rate of household change for individuals who are missing at any wave is .072 compared with .057 for those with complete data. Similarly, for children, the rate of household composition change for children with any missing waves is .077 compared with .064 for those with no missing waves.

To reduce the bias due to missing data, we recover some of the missing intervals by inferring composition change from the available data. For the first type of missing data, where an entire household goes missing, we compare each person’s household composition at their last appearance before the gap in data with their first appearance after the gap. If the households are the same, we code no composition change; if they are different, they are coded as having a composition change. In the middle, the composition change variable remains missing.

For the second type of missing data, with only some of the people in a household missing, we infer a composition change for everyone in the household. That is, when a person transitions to missing and someone who was in that person’s household appears in the data while that person is missing, we code both the person who went missing and the person who remains in the data as having a composition change. Analogously, when a person (ego) reappears in the data after a stretch of missing interviews, we code a composition change for everyone in the household who appeared in the data while ego was missing. First appearances in the data after Wave 1 are automatically coded as a household change for the person who appeared, unless the person is less than 1 year old. We do not count being born as a composition change from the perspective of the infant, but it is a household change for everyone else the infant lives with. Last appearances in the data are not counted as household changes unless the people ego last lived with are observed in subsequent interviews. By inferring composition change in this way, we are able to recover 62,943 (13 %) missing intervals and reduce the downward bias in our estimates. Using only fully observed intervals, the rate of composition change is .064 compared with .081 after inferring. For children, the estimated rate of change is .070 before inferring and .090 after.

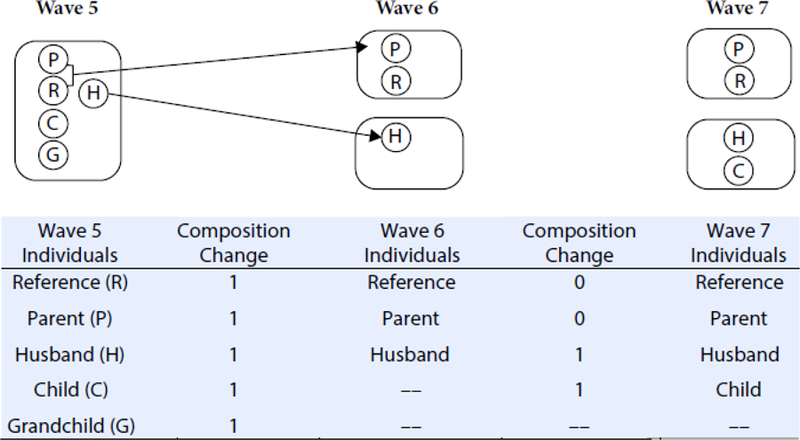

Figure 1 demonstrates what the application of these rules looks like in a sample household. In Wave 5, we observe a five-person household: the household reference person (R) and her parent (P), husband (H), child (C), and grandchild (G). In Wave 6, H, C, and G have left the household, and only H is observed at a new address. All five people are coded as experiencing a household change between Waves 5 and 6. The R and P are observed together in the same household in Waves 6 and 7 and are coded as experiencing no household change. C and G are not observed in Wave 6, but C is observed in the new household (with H) in Wave 7. G is coded missing for the interval between Waves 6 and 7 because we cannot know whether he experienced a household change since the one between Waves 5 and 6. Both C and H are coded as experiencing a household change between Waves 6 and 7 because the data indicate that C entered H’s household.

Fig. 1.

Illustration of measurement of composition change

Despite our efforts to recover missing data, we believe that we underestimate household instability. Composition change is still coded as missing when a whole household disappears from the data and never reappears. If a household goes missing in Wave 3 and reappears in Wave 7, composition change is coded missing for Waves 4–6. It seems likely that the missing periods have higher levels of instability than the periods we capture. Analysis weights correct for some of this bias to the extent that household instability is correlated with factors used to generate the weights. Additionally, we miss instability that occurs between interviews. Using the monthly household rosters collected in Wave 2 for household changes between Wave 1 and Wave 2, we determine that the rate of household change including household changes that occur between waves is 1.08 times the rate estimated by comparing household composition in the interview months. Thus, we believe that these are slightly conservative estimates but probably do not underestimate by much.

Race/ethnicity of the child is coded into five mutually exclusive categories: white, black, Hispanic, Asian, and other (including multiracial). The race/ethnicity of individuals varies slightly across the waves, but we use the child’s first recorded race/ethnicity. Parental education is measured as the education level of the child’s biological mother, recorded the first time that both the child and mother are observed in the household together. For the 13 % of children (10 % child-waves) that never lived with their biological mother, we code parental education as the education of stepmother/stepfather or adoptive mother/father if the child never lived with any mother. For children who never lived with a mother or father (3.6 % child-waves), parental education is missing. Education has four categories: less than high school, high school graduate (including GED), some college, and college degree or more.

Analytical Approach

To generate period estimates of children’s household instability, we create age-specific estimates of the probability that a child experiences any household change between two interviews. The numerator is all persons (age x) experiencing a change between two interviews, and the denominator excludes individuals not observed at both the start and end points unless someone in their household at the earlier or later interviews is observed. That is, the denominator includes only those nonmissing on the composition change variable (see Fig. 1, shown earlier).

We multiply the probability of experiencing a change between interviews (i.e., over a four-month period) by 3 to find an annual rate. We sum age-specific annual rates of change from ages 0–1 to age 17–18 to derive a cumulative number of transitions over the course of childhood. This approach is analogous to how a total fertility rate is calculated. We run these models for the full sample and then separately by race/ethnicity and maternal education.

Anyone interested may access our main data file to replicate or build on these analyses (Reynolds et al. 2019). Code to produce this and other analytical files is available in an online appendix.

Results

Table 1 presents information on children’s coresidence with nonnuclear kin and nonrelatives. Overall, we find that 19.8 % of all children coreside with nonrelatives or nonnuclear kin. This matches closely previous Current Population Survey–based estimates for 2010 of 19.5 % (Mykyta and Macartney 2012) and SIPP-based estimates of 20.8 % for 2009 (Pilkauskas and Cross 2018). Nearly 11 % coreside with a grandparent, and 16.4 % live with any extended kin. These estimates are also nearly exactly the same as found in previous research (Kreider and Ellis 2011; Pilkauskas and Cross 2018). In addition, about 4 % live with nonrelatives. As expected, and consistent with other research (Cross 2018), we see large variation by parental education and race/ethnicity. Among those whose parent has less than a high school diploma, more than one-quarter live with nonnuclear household members compared with only 8.2 % among children of a college graduate. Non-Hispanic whites have the lowest proportion living with nonnuclear kin.

Table 1.

Children’s coresidence with nonnuclear kin and nonrelativesa

| Total | <High School | High School | Some College | College Graduate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. By Parental Educationb | |||||

| Nonnuclear kin or nonrelative | 19.8 | 28.6 | 23.0 | 15.9 | 8.2 |

| Nonrelative | 4.1 | 5.7 | 3.7 | 3.1 | 1.9 |

| Grandparent | 10.6 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 8.8 | 4.4 |

| Any extended kin | 16.4 | 24.8 | 20.1 | 13.2 | 6.5 |

| White | Black | Hispanic | Asian | Other | |

| B. By Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Nonnuclear kin or nonrelative | 13.8 | 28.9 | 26.9 | 21.3 | 26.1 |

| Nonrelative | 3.8 | 3.6 | 4.7 | 2.2 | 6.6 |

| Grandparent | 7.2 | 17.1 | 13.3 | 15.6 | 13.5 |

| Any extended kin | 10.4 | 26.0 | 23.5 | 19.7 | 20.4 |

Sample includes 312,393 person-waves. Percentages are weighted.

Analysis of differences by parental education excludes the 3.6 % of children not living with a parent.

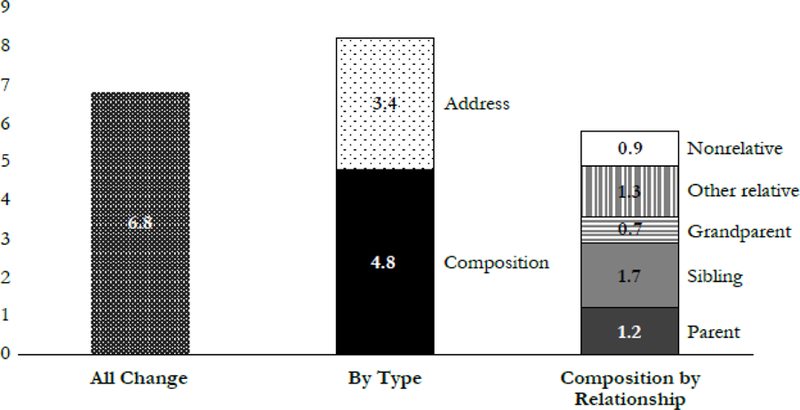

Figure 2 presents the cumulative number of household changes experienced by a child’s 18th birthday as well as cumulative number of changes by type. Overall, children experience considerable household instability while growing up, averaging 6.8 changes between birth and age 18. Of these household changes, 4.8 involve composition changes, and 3.4 involve a change of address. Because address change and composition change sometimes co-occur, the sum of the two is more than the total amount of change.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative number of household changes by age 18, overall and by type

The final column of Fig. 2 breaks instability in household composition by type of relationship. Children experience, on average, 1.2 parental changes by age 18. This is more than prior published estimates of an average of 1.01 changes among children born to mothers younger than 30 (Brown et al. 2016) because the prior estimates described family instability only up to age 12. Our SIPP-based estimate of family instability by age 12 among children born to mothers younger than 30 is effectively the same as the estimate from the National Survey of Family Growth for this population (0.99 compared with 1.01).

Importantly, parents account for a relatively small proportion of children’s household instability. Both siblings (1.7) and other relatives (1.3) contribute more to household instability. Again, because of overlap between the different types of change, the sum of the components is 5.8, more than the whole combined (4.8). That the component sum is not much more than the whole, however, suggests that there is not much co-occurrence of different types of change. All together, these results indicate that many children experience household instability throughout childhood and that parents contribute to only a small proportion of that instability.

Table 2 presents variation in household instability by parental education and race/ethnicity. Levels of household instability—both composition instability and changes in address—decrease nearly linearly as parental education increases. College graduates, however, are clearly distinct from the other educational groups with much lower levels of instability of all types. Children with a college-educated parent experience only 4.1 household changes by age 18, compared with nearly 8 changes among children of a high school graduate and 9 changes in the least-educated group. In addition, although the educational gradient in parental instability is large (1.4 changes for those with a parent with less than a high school diploma compared with 0.6 changes for those with a parent with a college degree), educational differences in household instability are even greater.

Table 2.

Cumulative number of household changes by age 18 by race/ethnicity and by parental education

| By Parental Education |

By Race/Ethnicity |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | <High School | High School | Some College | College Graduate | Non-Hispanic White | Black | Hispanic | Asian | Other | |

| All Changes | 6.8 | 9.0 | 7.8 | 7.1 | 4.1 | 5.8 | 8.5 | 7.8 | 5.1 | 8.7 |

| Address Changes | 3.4 | 4.3 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 4.9 | 3.7 | 2.5 | 4.2 |

| Composition Changes | 4.8 | 6.6 | 5.6 | 4.8 | 2.7 | 4.1 | 5.9 | 5.5 | 3.2 | 6.5 |

| Parent | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| Sibling | 1.7 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 2.2 |

| Grandparent | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1.2 |

| Other relative | 1.3 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 2.0 |

| Nonrelative | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.3 |

Note: Analyses are weighted.

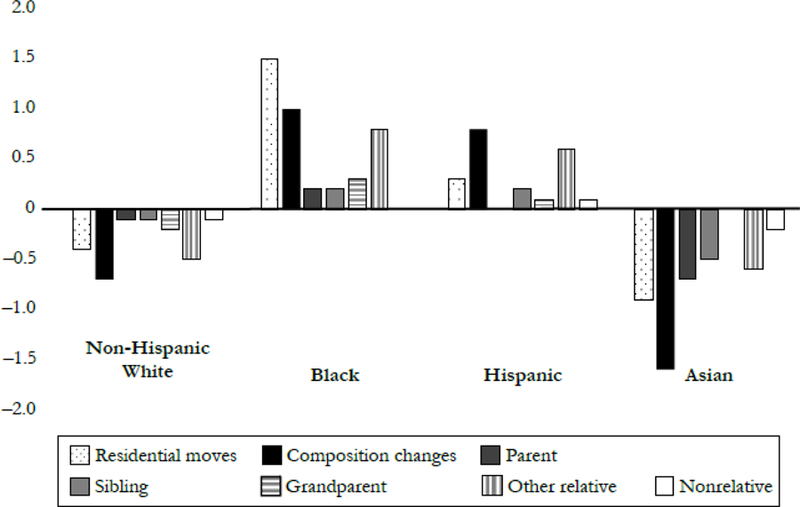

Household instability, including all composition and address changes, is higher for black and Hispanic children than for white and Asian children. In general, groups that experience more compositional change also experience more residential instability. For example, Asians experience less compositional instability and less residential instability than whites. Yet unlike differences in education, those across racial/ethnic groups are not always linear. Some groups experience particularly high levels of specific types of instability. To help see these patterns, we graph the difference in level of cumulative instability from the overall average for each type of instability by race/ethnicity. These results, shown in Fig. 3, reveal that children in black families experience disproportionately higher levels of residential instability. Whereas their compositional instability is 1.0 transition greater than the average, their residential instability is more than 1.5 transitions greater than the average. In addition, the greater compositional instability of black and Hispanic children’s households is due more to extended kin change than to parents or parental partners. Generally, compared with any other racial/ethnic group, Asian children experience less household instability, but they experience average levels of grandparent instability.

Fig. 3.

Differences in household instability from mean, by race/ethnicity

Discussion and Conclusion

Our research produces estimates of the amount of household instability (residential and compositional) children experience while growing up and how this varies by race/ethnicity and parental education. Our analyses indicate that children often live with nonnuclear kin; nearly one in five children lives with nonnuclear household members. This estimate is similar to findings from other research on children’s shared living arrangements (Mykyta and Macartney 2012; Pilkauskas and Cross 2018). Our analyses also show that typical measures of instability that focus on maternal relationship histories miss most household instability. Siblings are a major source of household compositional change, and children also experience residential instability and household change due to other adults and children entering and leaving the households. Unfortunately, data limitations prevent us from being able to separate normative changes, such as siblings being born, from nonnormative ones, such as stepsiblings moving in. Work by Perkins (2017) suggests that most sibling transitions are normative.

Considering nonparental sources of household instability, we determine that based on the rates of household instability prevailing during 2008–2013, children experience an average of 6.8 household transitions before reaching age 18. More than two-thirds of this instability (4.8 changes) involves a change in household composition. During the period of analysis, children also experienced substantial residential instability, averaging 3.4 changes in address between birth and age 18.

A voluminous literature points to the significance of parental instability for child well-being. Are these other forms of household instability also consequential for children? Existing theories suggest that other sources of household instability might matter. Family stress theory, for example, argues that parental divorce and remarriage are stressful for children partly because they are accompanied by changes in household order and routine, reducing a family’s capability to meet the child’s needs. Moreover, each additional transition can make it more difficult for a family to recover and reach a new normal (Osborne and McLanahan 2007). The birth of a new sibling might be similarly disruptive even if it is normative. The movement of other kin and nonrelatives may also disrupt routines and introduce conflict in the home, making it more difficult for children to develop a sense of stability and routine.

Alternatively, work comparing the implication of social father exits from biological father exits suggests that some transitions may be uniquely disruptive to child development (Brown 2006; Lee and McLanahan 2015). In households that include kin or other nonrelatives, the norms that shape ties as well as the flow of valued resources between household members may be limited or less clearly defined (Carroll et al. 2007). Limited obligations of an uncle to a child, for example, may make his movement in or out of the household less salient for children. Alternatively, having an uncle come and go might disrupt household routines and make parenting children more difficult. Exploring these different sources of household instability can help us to understand why instability—parental, kin, or otherwise—is connected to child development.

To that end, research on instability should be broadened to investigate the associations between various forms of household instability and child outcomes. Recent research has found a link between household change due to nonnuclear household members and children’s educational attainment (Perkins 2019). Other research has considered multiple sources of instability in children’s environment, including residential mobility, finding that persistent change is associated with poorer child behavior (Fomby and Mollborn 2017). More research along these lines can provide useful information for refining theories of child development and the intergenerational transmission of social advantage.

Our analyses also confirm our expectation that household instability is much greater for racial/ethnic minorities and for children in educationally disadvantaged households. We find that non-Hispanic white children are less likely live with nonnuclear household members (i.e., someone who is not a parent or sibling) than any other racial/ethnic group. In addition, parental education is negatively associated with coresidence with nonnuclear household members. Because nonnuclear household members often leave the household quickly (see also Perkins 2017), they contribute a substantial proportion of children’s household instability. This is one reason why white and Asian children experience less household instability than black, Hispanic, and multiracial children and why parental education is negatively associated with all forms of household instability, especially compositional instability. These differences may not just reflect but also contribute to widening disparities in child well-being by race and class.

Previous research suggests that family instability, as measured by maternal partnership transitions, is less consequential for black children than for white children (e.g., Fomby and Cherlin 2007; Wu and Martinson 1993; Wu and Thompson 2001), perhaps because maternal instability captures a lower proportion of household instability for racial/ethnic minorities than for non-Hispanic whites. Scholarship has long pointed to the significance of extended kin in the lives of black and Hispanic households (e.g., Glick and Van Hook 2011; Sarkisian et al. 2007; Stack and Burton 1993), likely offsetting the negative effect of partner change by providing both children and parents greater access to kin and kin-like figures who can provide emotional and instrumental support during times of change (Fomby et al. 2010). Given this, the movement of other kin may be especially relevant to the well-being of minority children. Considering the instability of other kin in the lives of black and Hispanic children can open new ways of thinking about and measuring instability and child well-being.

Although black children experience more than the average number of changes in household composition, they experience especially high levels of residential instability. This is likely rooted in institutionalized racial biases that keep black families segregated in poorer neighborhoods (Sharkey 2008). Changes to housing policy that help black families attain desired housing outcomes may reduce children’s exposure to persistent instability.

Although the longitudinal household roster data available in the SIPP have many strengths that make this research possible, they also have some limitations. Perhaps the most severe is missing data due to panel attrition. We do not count transitions of whole households into missing as a household change, but it seems likely that relocations are sometimes a cause of missingness. Supplemental analyses (available on request) show that individuals that experience instability are more likely to have missing waves. In addition, we do not use information on changes in household composition between waves. Thus, it is likely that we somewhat underestimate the levels of household instability that children experience.

Other problems with these data include difficulties measuring how household members are related. We are unable to determine a child’s relationship to another household member in about 1 % of the cases. Moreover, we are unable to distinguish full, half-, and stepsiblings. The 2014 panel of the SIPP makes this possible, however, and new waves are scheduled to be released soon.

Finally, these data reflect children’s experiences during and just after the Great Recession. Previous research suggests that the recession temporarily depressed divorce rates (Cherlin et al. 2013; Cohen 2014), and it may have increased the prevalence of complex households. Although the effect was probably small overall (Bitler and Hoynes 2015), it could have been an especially relevant strategy for disadvantaged families with young children (Pilkauskas et al. 2014). We also do not know whether the estimates of residential stability reflect what occurs in better economic times.

Family demographers have made important strides to better measure children’s experiences with nonnormative family structures including single-parent families. Living with nonnuclear kin is common, but we know relatively little about the consequences of this experience for child development. Importantly, new dimensions of household instability have the potential to provide researchers with more tools to identify why household instability contributes to child development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research benefited from comments by FAMDEM seminar participants, especially Abigail Weitzman and Alex Weinreb, PRC Brownbag participants, and the comments of anonymous reviewers. It was supported by Grants P2CHD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin; and R03HD090425, Children’s Family and Household Experiences (Raley PI) by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- Amato PR (2000). The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1269–1287. [Google Scholar]

- Amorim M, Dunifon R, & Pilkauskas N (2017). The magnitude and timing of grandparental coresidence during childhood in the United States. Demographic Research, 37, 1695–1706. 10.4054/DemRes.2017.37.52 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Astone NM, & McLanahan S (1994). Family strucure, residential mobility, and school dropout: A research note. Demography, 31, 575–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitler M, & Hoynes H (2015). Living arrangements, doubling up, and the Great Recession: Was this time different? American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 105, 166–170. [Google Scholar]

- Bloome D (2017). Childhood family structure and intergenerational income mobility in the United States. Demography, 54, 541–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL (2006). Family structure transitions and adolescent well-being. Demography, 43, 447–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, Stykes JB, & Manning WD (2016). Trends in children’s family instability, 1995–2010. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 1173–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JS, Olson CD, & Buckmiller N (2007). Family boundary ambiguity: A 30-year review of theory, research, and measurement. Family Relations, 56, 210–230. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh SE, & Fomby P (Forthcoming). Family instability in the lives of American children. Annual Review of Sociology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cavanagh SE., & Huston AC. (2006). Family instability and children’s early problem behavior. Social Forces, 85, 551–581. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin A, Cumberworth E, Morgan SP, & Wimer C (2013). The effects of the Great Recession on family structure and fertility. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 650, 214–231. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen PN (2014). Recession and divorce in the United States, 2008–2011. Population Research and Policy Review, 33, 615–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M, Ganong L, & Fine M (2000). Reinvestigating remarriage: Another decade of progress. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1288–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Cross CJ (2018). Extended family households among children in the United States: Differences by race/ethnicity and socio-economic status. Population Studies, 72, 235–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond M (2012). Eviction and the reproduction of urban poverty. American Journal of Sociology, 118, 88–133. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond M, Gershenson C, & Kiviat B (2015). Forced relocation and residential instability among urban renters. Social Service Review, 89, 227–262. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond M, & Perkins KL (2016). Housing and household instability. Urban Affairs Review, 52, 421–436. [Google Scholar]

- Dreier P, Mollenkopf J, & Swanstrom T (Eds.). (2001). Place matters: Metropolitics for the twenty-first century. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan B (1967). Education and social background. American Journal of Sociology, 72, 363–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomb P., & Cherlin AJ. (2007). Family instability and child well-being. American Sociological Review, 72, 181–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomby P, & Mollborn S (2017). Ecological instability and children’s classroom behavior in kindergarten. Demography, 54, 1627–1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomby P, Mollborn S, & Sennott CA (2010). Race/ethnic differences in effects of family instability on adolescents’ risk behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 234–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomby P, & Sennott CA (2013). Family structure instability and mobility: The consequences for adolescents’ problem behavior. Social Science Research, 42, 186–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geist C, & McManus PA (2008). Geographical mobility over the life course: Motivations and implications. Population, Space and Place, 14, 283–303. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Davis C, & Rackin H (2014). Marriage or carriage? Trends in union context and birth type by education: Changing union context. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 506–519. [Google Scholar]

- Glick JE, & Van Hook J (2011). Does a house divided stand? Kinship and the continuity of shared living arrangements. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73, 1149–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser RM, & Featherman DL (1976). Equality of schooling: Trends and prospects. Sociology of Education, 49, 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kamo Y (2000). Racial and ethnic differences in extended family households. Sociological Perspectives, 43, 211–229. [Google Scholar]

- Kreider RM, & Ellis RR (2011). Living arrangements of children: 2009 (Current Population Reports No. P70–125) Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Lee D., & McLanahan S. (2015). Family structure transitions and child development: Instability, selection, and population heterogeneity. American Sociological Review, 80, 738–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SP (2006). Trends in marital dissolution by women’s education in the United States. Demographic Research, 15, 537–560. 10.4054/DemRes.2006.15.20 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SP, Astone NM, & Peters HE (2014). Fewer marriages, more divergence: Marriage projections for millennials to age 40 (Report) Washington, DC: Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S (2004). Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41, 607–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, & Sandefur GD (1994). Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, Tach L, & Schneider D (2013). The causal effects of father absence. Annual Review of Sociology, 39, 399–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mykyta L, & Macartney S (2012). Sharing a household: Household composition and economic well-being: 2007–2010 (Current Population Reports No. P60–242) Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne C, & McLanahan S (2007). Partnership instability and child well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 1065–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KL (2017). Household complexity and change among children in the United States, 1984 to 2010. Sociological Science, 4, 701–724. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KL. (2018, April). Compounded change: Residential mobility, changes in household composition, and children’s educational attainment. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America, Denver, CO. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KL (2019). Changes in household composition and children’s educational attainment. Demography, 56, 525–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkauskas NV (2012). Three-generation family households: Differences by family structure at birth. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 931–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkauskas NV, & Cross C (2018). Beyond the nuclear family: Trends in children living in shared households. Demography, 55, 2283–2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkauskas NV, Garfinkel I, & McLanahan SS (2014). The prevalence and economic value of doubling up. Demography, 51, 1667–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rackin HM, & Gibson-Davis CM (2018). Social class divergence in family transitions: The importance of cohabitation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80, 1271–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK & Bumpass LL (2003). The topography of the divorce pleateau: Levels and trends in union stability in the United States after 1980. Demographic Research, 8, 245–260. 10.4054/DemRes.2003.8.8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK, Sweeney MM, & Wondra D (2015). The growing racial and ethnic divide in U.S. marriage patterns. Future of Children, 25(2), 89–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK, & Wildsmith E (2004). Cohabitation and children’s family instability. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 210–219. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds R, Raley K, & Weiss I (2019). Household change with relationships [Texas Data Repository Dataverse, V1]. Retrieved from https://dataverse.tdl.org/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.18738/T8/CAMJAL

- Sarkisia N., Gerena M., & Gerste N. (2007). Extended family integration among Euro and Mexican Americans: Ethnicity, gender, and class. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey P (2008). The intergenerational transmission of context. American Journal of Sociology, 113, 931–969. [Google Scholar]

- Stack CB, & Burton LM (1993). Kinscripts. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 24, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MM, & Raley RK (2014). Race, ethnicity, and the changing context of childbearing in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 40, 539–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner MA, Ross S, Galster G, & Yinger J (2002). Discrimination in metropolitan housing markets (Report). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hook J, & Glick JE (2007). Immigration and living arrangements: Moving beyond economic need versus acculturation. Demography, 44, 225–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldfogel J, Craigie T-A, & Brooks-Gunn J (2010). Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing. Future of Children, 20(2), 87–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LL, & Martinson BC (1993). Family structure and the risk of a premarital birth. American Sociological Review, 58, 210–232. [Google Scholar]

- Wu LL & Thomson E (2001). Race differences in family experience and early sexual initiation: Dynamic models of family structure and family change. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 682–696. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.