Abstract

Background

Evaluating hospital efficiency is a process to optimize resource utilization and allocation. This is vital due to hospitals being the largest financial cost in a health system. To limit avoidable uses of hospital resources, it is important to identify the sources of hospital inefficiencies and to put in place measures towards their reduction and elimination. Thus, the purpose of this research is to examine the sources of hospital inefficiency in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, and existing strategies tackling this issue.

Methods

In this study, the electronic databases MEDLINE (via PubMed), Web of Science, Embase, Google, Google Scholar, and reference lists of selected articles, were explored. Studies on inefficiency, sources of inefficiency, and strategies for inefficiency reduction in the Eastern Mediterranean region hospitals, published between January 1999 and May 2018, were identified. A total of 1466 articles were selected using the initial criteria. After further reviews based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 56 studies were eligible for this study. The chosen studies were conducted in Iran (n = 35), Saudi Arabia (n = 5), Tunisia (n = 5), Jordan (n = 4), Pakistan (n = 2), the United Arab Emirates, Palestine, Iraq, Oman, and Afghanistan (n = 1 each). These studies were analyzed using content analysis in MAXQDA 10.

Results

The analysis showed that approximately 41% of studies used data envelopment analysis (DEA) to measure hospital efficiency. Sources of hospital inefficiency were divided into four categories for analysis: Hospital products and services, hospital workforce, hospital services delivery, and hospital system leakages.

Conclusion

This study has revealed some sources of inefficiency in the Eastern Mediterranean Region hospitals. Inefficiencies are thought to originate from excess workforce, excess beds, inappropriate hospital sizes, inappropriate workforce composition, lack of workforce motivation, and inefficient use of health system inputs. It is suggested that health policymakers and managers use this evidence to develop appropriate strategies towards the reduction of hospital inefficiency.

Keywords: Efficiency, Hospitals, Eastern Mediterranean countries, Systematic review

Background

Hospitals are an essential component of health systems, while also being the most costly. They account for 50–80% of total health expenditures [1]. Hospital costs continue to rise due to the development of new technologies. New diagnostic and therapeutic methods are implemented to combat the rising proportion of chronic diseases, the increasing demand for health services, and the subsequent medical errors [2]. This has become a primary challenge and concern for governments [3].

Hospitals in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR) differ in size, proprietorship, assignment, and performance. The total number of hospital beds is estimated to be 740,000 and, except for Lebanon, the majority of hospital beds are in the public sector (80%), with the remaining in private for-profit (18%) and private not-for-profit (2%) hospitals. The range of hospital beds per 10,000 population vary from 3.9 to 32 in 22 countries in the EMR. Hospitals also vary widely in size, location (rural and urban), resources, specialization (general versus specialty hospitals) and organization, as well as their position in the health system (first-level hospitals, secondary care hospitals and large teaching institutions) [4]. A large proportion of hospitals are financed by the government, but out-of-pocket payments are rising due to limited public sector resources [5]. This leads to limited access to health services for vulnerable communities. Private hospitals in the EMR are usually small to medium size and located in capitals and other large cities. These hospitals are not the result of comprehensive health system planning, as such, they can also lead to inequity in access to healthcare. Most countries in the EMR have addressed inequalities by implementing reforms to increase productivity, transparency, and cost flexibility [5–7]. To facilitate this process and increase hospital efficiency, it is necessary to provide the healthcare sector with additional resources and management tools.

According to Farrell (1957), efficiency is defined as “the firm’s success to produce the maximum feasible amount of output from a given amount of input or producing a given amount of output using the minimum level of inputs where both the inputs and the outputs are correctly measured” [8]. Three different types of efficiency were defined by Farrell: technical efficiency, allocative efficiency, and economic efficiency. Technical efficiency is the ability of a business to gain a maximum output from the specific input. In contrast, allocative efficiency refers to the directing of resources toward products or services with the highest demand. Economic efficiency is allocative efficiency and technical efficiency from a joint unit of cost efficiency. An organization has an economic efficiency Which be efficient in terms of both technical and allocational [8]. In general, different methods have been used to measure hospital efficiency: Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA), Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA), and measures of performance, such as Pabon Lasso’s model. DEA is a non-parametric linear programming method used to evaluate the efficiency of decision-making units [8, 9]. SFA is parametric and calculates the difference between the organization’s predicted and expected outputs [10]. Pabon Lasso’s model (1986) assesses hospital performance using three performance indicators: bed occupancy rate (BOR), bed turnover rate (BTR), and average length of stay (ALS) [11].

A decline in hospital efficiency has been observed worldwide. In a global report by the World Health Organization (WHO) published in 2010, 10 sources of hospital inefficiency were identified: (1) underuse or overpricing of generic drugs; (2) use of substandard or counterfeit drugs; (3) inappropriate and ineffective drug use; (4) overuse or oversupply of equipment, investigations and procedures; (5) inappropriate or costly workforce mix, unmotivated worker; (6) inappropriate hospital admissions or length of stay; (7) inappropriate hospital size (low use of infrastructure); (8) medical errors and suboptimal quality of care; (9) waste, corruption and fraud; and (10) inefficient mix or inappropriate level of strategies [12]. However, thus far there has not been a comprehensive review to assess the source of hospital inefficiency in the EMR. This study aims to comprehensively identify the sources of hospital inefficiency in the EMR, and compare these to previously identified sources of hospital inefficiency. This will provide insight into the current condition of healthcare in this region.

According to the aforementioned WHO report, hospital efficiency in the EMR is low, particularly in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) [5]. To increase hospital efficiency in a context of rising costs and limited resources, it is necessary to identify sources of inefficiency and to suggest improvement strategies. Identifying these sources and identifying improvements are the objectives of this study.

Methods

This is a systematic review of existing evidence on hospital inefficiency in the EMR. This study recruited English peer-reviewed articles published between January 1999 and May 2018. To identify relevant articles, a database search was conducted in MEDLINE (via PubMed) (Additional file 1), Web of Knowledge, Embase, Google and Google Scholar. Keywords used included “efficiency”, “productivity”, “inefficiency”, “hospital”, “data envelopment analysis”, “Pabon Lasso”, and “stochastic frontier analysis”. Moreover, the reference lists of selected articles were searched for relevant papers. Economic journals in the field of health economy and efficiency such as the Journal of the Knowledge Economy, the American Journal of Economics and Business Administration, Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation, and the International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues were searched individually. An initial review was conducted to determine the scope of the study, and no study published before 1999 was found. Therefore, the review included studies between 1999 and May 2018.

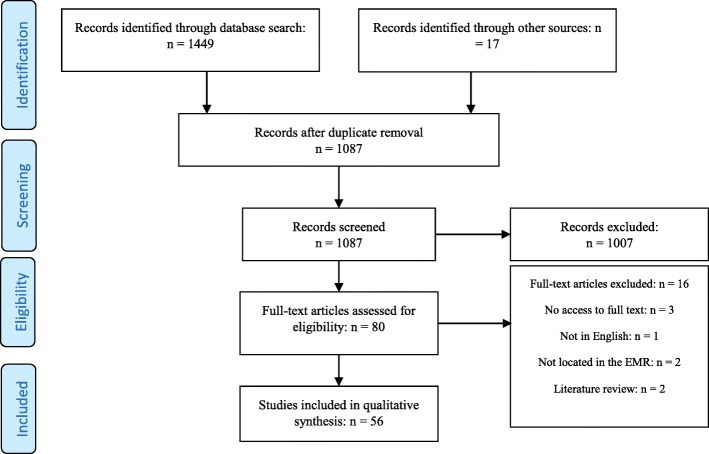

Following the screening of 1087 identified articles, 80 full texts were assessed for eligibility. After assessing these articles, 56 were included in the review. The screening process and search results are shown in the PRISMA Flow Diagram [13] of Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram: Database search and article selection process

A data extraction form with entries for the first author, year of publication, country of study, data collection method, number of hospitals studied, inputs and outputs for efficiency, sources of hospital inefficiency, and factors affecting efficiency, was used to collect data from the selected studies. For higher reliability, two researchers independently extracted data from a randomly selected sample of the chosen articles. Any disagreements were solved by discussion and consensus and, if necessary, by a third reviewer.

Mitton et al.’s fifteen-point scale [14] was used for quality appraisal. The criteria used to assess quality included: literature review and identification of research gaps; research question and design, validity and reliability; data collection; population and sampling; and analysis and reporting of results. These criteria were rated 0 (not present or reported), 1 (present but low quality), 2 (present and mid-range quality), or 3 (present and high quality). Articles were rated independently by two researchers using the article quality rating sheet. Given that the review was qualitative, articles were not removed at this stage, but more weight was given to articles with a quality rating of 10 or above in the data analysis and interpretation of results.

The data were analyzed using qualitative content analysis. Data were coded and managed using MAXQDA 10 for Windows (VERBI GmbH, Berlin, Germany), and themes and subthemes were extracted to identify patterns and relationships between themes.

Results

A total of 56 articles on hospital efficiency in the EMR, published between January 1999 and May 2018, were reviewed. A large number of studies (91%) were published after 2010. The reviewed studies were only conducted in 10 out of 22 EMR countries included in the search. Iran (n = 35) was most represented in the included studies, followed by Saudi Arabia (n = 5) and Tunisia (n = 5), Jordan (n = 4), Pakistan (n = 2), and finally UAE, Palestine, Iraq, Oman, and Afghanistan (n = 1 each).

Overall, 1995 hospitals were examined in these studies; most of them located in Iran (n = 858), Saudi Arabia (n = 573), Tunisia (n = 266), UAE (n = 96), Jordan (n = 72) and Afghanistan (n = 68). Out of 56 reviewed studies, 21 used DEA (37%), 12 used Bayesian SFA (21%), 10 used Pabon Lasso’s model (18%), and four studies used the Malmquist index (7.5%). Moreover, four studies (7.5%) used a hybrid approach by comparing DEA and Pabon Lasso’s model. Finally, five studies (9%) used other methods (the Cobb-Douglas Model, the Lean model, and efficiency and performance indicators).

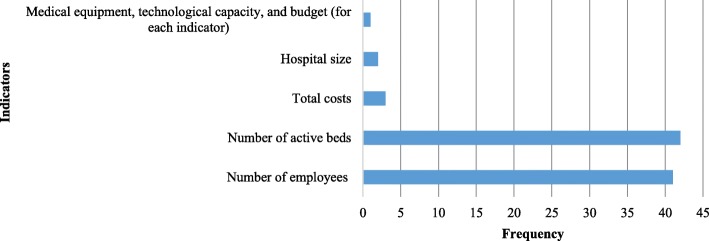

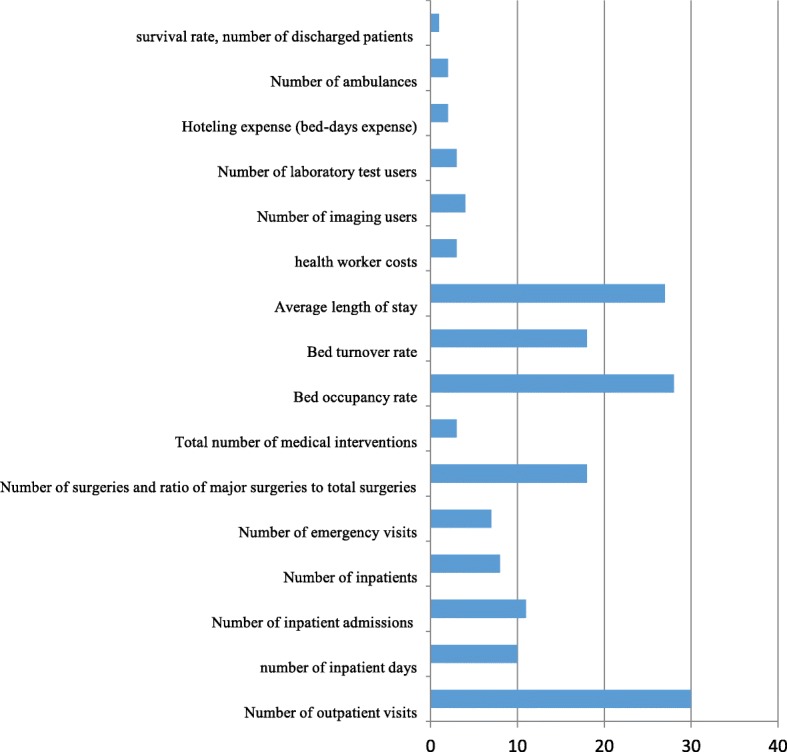

Calculating efficiency requires input and output variables. In data analysis, the number of workforce, active beds, total costs, hospital size, medical equipment, technological capacity, and budget have been used as input variables (Fig. 2). Total outpatient visits, inpatient admissions and days, number of inpatients, emergency visits, number of surgeries, ratio of major surgeries to total surgeries, total number of medical interventions, BOR, BTR, average length of stay (ALS), number of ambulances, ratio of active beds to fixed beds, hoteling expense (bed-day costs) and employee expense total survival rate, number of discharged patients, number of imaging service users, and number of laboratory test users, were used as output variables (Fig. 3). The input and output selection depends on the objective of the study and efficiency measurement. It is reasonable to consider total costs on the input side; however, few studies have employed hospital hoteling and workforce expenses as output in their evaluation. For example, Hatam [15] used hoteling and workforce expenses and found that most cases had more workforce and hoteling expenses than the similar ones showing significant inefficiency.

Fig. 2.

Frequency of input variables used to measure hospital efficiency in EMR countries

Fig. 3.

Frequency of output variables used to measure hospital efficiency in EMR countries

Operational definitions for acronyms and terms of input and output measures are given below:

Number of active beds: alternative term for ‘available beds’ [16].

Number of beds or hospital size: “Hospital beds include all beds that are regularly maintained and staffed and are immediately available for use. They include beds in general hospitals, mental health, and substance abuse hospitals, and other specialty hospitals. Beds in nursing and residential care facilities are excluded” [17].

Number of inpatient admissions: Mean number of hospital admissions in a certain hospital per year [16].

Number of bed-days: “number of days during which a person is confined to a bed and in which the patient stays overnight in a hospital” [18].

Bed occupancy rate (BOR): “The occupancy rate for curative (acute) care beds is calculated as the number of hospital bed-days related to curative care divided by the number of available curative care beds, multiplied by 365”.

Bed turnover rate (BTR): the number of times there is change of occupant for a bed during a given time period [17].

Average length of stay (ALS): “Average length of stay refers to the average number of days that patients spend in hospital. It is generally measured by dividing the total number of days stayed by all inpatients during a year by the number of admissions or discharges. Day cases are excluded” [17].

Day surgery: Day surgery is defined as the release of a patient who was admitted to a hospital for a planned surgical procedure and was discharged the same day [16].

Table 1 provides a summary of the studies reviewed, presenting the type and total number of hospitals examined, the methods used to calculate efficiency, inputs and outputs, and the source of inefficiency.

Table 1.

Summary of reviewed studies

| Author | Year | Country | Hospital type | Number of hospitals | Method used to calculate efficiency | Input and outputs | Source of inefficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Shammari [19] | 1999 | Jordan | Hospitals of MoH* | 15 | DEA |

Inputs: Numbers of bed-days, physicians, health workforce Outputs: Numbers of inpatient days, minor operations, major operations |

Excess resources |

| Ramanathan [20] | 2005 | Oman | Regional and Wilayat hospitals (MoH), Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, Hospital of the Royal Oman Police | 20 | DEA (Malmquist index) |

Inputs: Numbers of beds, physicians, and other medical workforces. Outputs: Number of visits, in-patient services, surgical operations |

Partial utilization of inputs, lack of full compliance with technological changes |

| Hajialiafzali [21] | 2007 | Iran | Hospitals affiliated with the Social Security Organization | 53 | DEA (frontier-based methods) |

Inputs: Total numbers of FTE* medical doctors, of FTE nurses, of other FTE workforces, number of beds Outputs: Numbers of outpatient visits and emergency visits, ratio of major surgeries to total surgeries, total numbers of medical interventions and surgical procedures |

Partial utilization of inputs |

| Hatam [15] | 2008 | Iran | Hospitals affiliated with the Social Security Organization | 18 | DEA (frontier-based methods) |

Inputs: Numbers of beds, FTE, total expense Outputs: Patient-days, BOR*, BTR,* ALS*, ratio of available beds to constructed beds, hoteling expense, bed-day costs, workforce costs |

Unused beds |

| Goshtasebi [22] | 2009 | Iran | MoH hospitals | 6 | Pabon Lasso | Output: ALS, BOR, BTR | Underutilization of resources, high BOR |

| Jandaghi [23] | 2010 | Iran | Public and private hospitals | 8 | DEA (frontier-based methods) |

Inputs: Numbers of physicians, nurses, medical workforce, official workforce, annual costs of hospital Outputs: Numbers of clinical visits, emergency visits, and bed-days |

Excess resources |

| Hatam [24] | 2010 | Iran | General public hospitals | 21 | DEA (frontier-based methods) |

Inputs: Numbers of hospital beds, FTE physicians, nurses, and other workforces Outputs: BOR, patient–day admissions, bed-days, ALS, BTR |

Lack of motivation to select inputs to minimize expenses caused by the fact that hospitals are public and therefore do not seek profitability. |

| Shahhoseini [25] | 2011 | Iran | Provincial hospitals | 12 | DEA (frontier-based methods) |

Inputs: Numbers of active beds, nurses, physicians, and other professionals Outputs: Number of surgeries, outpatients visits, BOR, ALS, inpatient days |

Excess resources |

| Ketabi [26] | 2011 | Iran | Hospitals in Isfahan | 23 | DEA |

Inputs: Average numbers of active beds, medical equipment, workforce (such as doctors, nurses and technicians) Outputs: BOR (%), ALS, total percentage of survival, performance ratio |

Excess medical equipment, workforce and technology for teaching and private hospitals. Teaching hospitals are less efficient because of bureaucratic processes and private hospitals have lower BORs. |

| Bahadori [27] | 2011 | Iran | Hospitals affiliated with Urmia University of Medical Sciences | 23 | Pabon Lasso | Output: ALS, BOR, BTR | Poor performance in BOR and/or BTR in 60.87% of hospitals. |

| Al-Shayea [28] | 2011 | Saudi Arabia | Khalid University Hospital | 1 (9 departments) | DEA |

Inputs: doctors’ total salary, nurses’ total salary Outputs: Numbers of in-patients, outpatients, bed and average turnover rate |

High costs of inputs |

| Kiadaliri [29] | 2011 | Iran | General hospitals affiliated with Ahvaz Jondishapour University of Medical Sciences | 19 | DEA (frontier-based methods) |

Inputs: beds, human resources Outputs: inpatient days, outpatient days, number of surgeries, BOR |

Inappropriate hospital sizes |

| Osmani [30] | 2012 | Afghanistan | District Hospitals | 68 | DEA and Tobit regression analysis model |

Inputs: Numbers of physicians, midwives, nurses, non-medical workforce, and beds Outputs: Numbers of outpatient visits, inpatient admissions, and patient days, ALS, BOR, number of hospital beds (proxy for hospital size), bed-physician and outpatient physician ratio, number of physicians |

Excess numbers of doctors, nurses, and beds |

| Farzianpour [31] | 2012 | Iran | Teaching hospitals of Tehran University of Medical Sciences | 16 | DEA (frontier-based methods) |

Inputs: Numbers of physicians, practicing nurses in health facilities, and active beds Outputs: Numbers of inpatients, outpatients, ALS |

Excess inputs or insufficient outputs |

| Chaabouni [32] | 2012 | Tunisia | Public hospitals | 10 | DEA and The Bootstrap Approach |

Inputs: Numbers of physicians, nurses, dentists and pharmacists, other workforces, and beds Outputs: Numbers of outpatient visits, admissions, post-admission days |

High hospital expenditures |

| Barati Marnani [33] | 2012 | Iran | Affiliated with Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences | 23 | Pabon Lasso model and DEA (frontier-based methods) |

Pabon Lasso: ALS, BOR, BTR DEA: Inputs: Numbers of physicians, nurses, other workforces, and active beds Outputs: BOR, numbers of patients and surgeries |

Excess resources |

| Sheikhzadeh [34] | 2012 | Iran | Elected public and private hospitals of East Azerbaijani Province | 6 | DEA (frontier-based methods) |

Inputs: Numbers of specialist physicians, general physicians, nurses, residents, medical team workforce with a degree (Bachelor’s), medical team, nonmedical and support workforce, and active beds Outputs: Numbers of emergency patients, outpatients, and inpatients, average daily inpatients residing in hospital |

Excess and inefficient inputs: lack of medical services for the amount of resources used. |

| Yusefzadeh [35] | 2013 | Iran | Public hospitals | 23 | DEA |

Inputs: Numbers of active beds, doctors, and other workforces Outputs: Number of outpatients’ admissions and day-beds |

Excess inputs or insufficient outputs |

| Gholipour [36] | 2013 | Iran | Obstetrics and gynaecology teaching hospitals | 2 | Pabon Lasso | Output: ALS, BOR, BTR | Low BOR |

| Arfa [37] | 2013 | Tunisia | Public hospitals | 101 | DEA |

Five fixed inputs: Numbers of physicians, dentists, mid-wives, nurses or equivalents, and beds. One variable input: budget Outputs: Numbers of outpatient visits and admissions |

Hospitals are not operating at full capacity |

| Ajlouni [38] | 2013 | Jordan | Public hospitals | 15 | DEA and Pabon-Lasso |

Pabon Lasso: ALS, BOR, BTR DEA: Inputs: Numbers of bed-days, physicians per year, and health workforce per year Outputs: Patient days, numbers of minor operations and major operations |

Poor management, treatment of diseases requiring long patient stays |

| Abou El-Seoud [39] | 2013 | Saudi Arabia | Public hospitals that have been reformed to operate under private sector management through the full operating system in Saudi Arabia | 20 | DEA |

Inputs: Numbers of specialists, nurses, allied workforce, and beds Outputs: Numbers of visits, patient hospital admissions, laboratory tests, and beneficiaries of radiological imaging |

Administrative weakness to overcome external environmental factors rather than inability to manage internal operations |

| Bastani [40] | 2013 | Iran | Hospitals affiliated to the MoH | 139 | Four hospital performance indicators | Output: ALS, BOR, BTR | Inappropriate hospital sizes |

| Younsi [41] | 2014 | Tunisia | 30 public and 10 private hospitals | 40 | Pabon Lasso | Output: ALS, BOR, BTR | Low bed density which may not match population hospital needs. Hospital bed numbers should be increased or maintained. |

| Torabipour [42] | 2014 | Iran | Teaching and non-teaching hospitals of Ahvaz County | 12 | DEA (Malemquist index) |

Inputs: Numbers of nurses, beds, and physicians. Outputs: Numbers of outpatients and inpatients, ALS, number of major operations |

Lack of familiarity of managers with advanced hospital technologies, lack of equipment and inappropriate use of technology in diagnosis, care and treatment. |

| Syed Aziz Rasool [43] | 2014 | Pakistan | Non-profit private organization (branches of LRBT hospitals) | 16 | DEA |

Inputs: Numbers of beds, specialists, nurses Outputs: Numbers of outpatient visits, inpatient admissions, and total numbers of surgeries |

Lack of government funds to hospitals run by non-profit organizations. |

| Pourmohammadi [44] | 2014 | Iran | All hospitals affiliated with the Social Security Organization | 64 | The Cobb-Douglas model |

Inputs: Numbers of physicians, nurses, other workforces, and active beds Outputs: Number of outpatients and inpatients |

Excess workforce |

| Mehrtak [45] | 2014 | Iran | All general hospitals located in Iranian Eastern Azerbijan Province | 18 | Pabon Lasso and DEA |

Pabon Lasso: ALS, BOR, BTR DEA: Inputs: Numbers of active beds, physicians, nurses, discharged patients Outputs: Number of surgeries and discharged patients, BOR |

Excess inputs: larger hospitals are more efficient than smaller hospitals. |

| Lotfi [46] | 2014 | Iran | All hospitals of Ahvaz (8 hospitals affiliated with Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences and 8 non-affiliated hospitals) | 16 | Pabon Lasso and DEA |

Pabon Lasso: ALS, BOR, BTR DEA: Inputs: Numbers of physicians, nurses, other workforces, and active beds Outputs: BOR, numbers of patients and surgeries |

Underuse of resources, excess hospital inputs |

| Kalhor [47] | 2014 | Iran | Hospitals affiliated with Qazvin University | 6 | Pabon Lasso | Output: ALS, BOR, BTR | Poor managerial decisions |

| Goudarzi [48] | 2014 | Iran | Teaching hospitals affiliated with Tehran University of Medical Sciences | 12 | DEA (frontier-based methods) |

Inputs: Numbers of medical doctors, nurses, and other workforces, active beds, and outpatient admissions Outputs: Number of inpatient admissions |

Excess numbers of nurses and active beds |

| Askari [49] | 2014 | Iran | Hospitals affiliated with Yazd University of Medical Sciences | 13 | DEA |

Inputs: Numbers of active beds, nurses, physicians, and non-clinical workforce Outputs: hospitalization admissions, BOR (%), and number of surgeries |

High excess inputs, particularly the excess number of nurses. |

| Adham [50] | 2014 | Iran | Teaching and non-teaching hospitals | 14 | Pabon Lasso | Output: ALS, BOR, BTR | Low BOR |

| Imamgholi [51] | 2014 | Iran | Hospitals affiliated to Busheher University of Medical Sciences | 7 | Pabon Lasso | Output: ALS, BOR, BTR | Non-optimal hospital sizes |

| Shetabi [52] | 2015 | Iran | Hospitals affiliated to Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences | 7 | DEA |

Inputs: Numbers of active beds, doctors, nurses, and other workforces Outputs: Numbers of accepted inpatients, outpatients and BOR (%) |

Excess inputs |

| Masoompourb [53] | 2015 | Iran | Teaching Hospital | 1 | Pabon Lasso | ALS, BOR, BTR | Decrease in ALS |

| Chaabouni [54] | 2016 | Tunisia | Public Hospitals | 10 | DEA (frontier-based methods) |

Inputs: Numbers of physicians, nurses, dentists, pharmacists, and beds, total cost Outputs: Numbers of outpatient visits, admissions, and post-admission days, price of labor |

large hospital sizes |

| Safdar [55] | 2016 | Pakistan | A large public hospital | 1 | DEA |

Inputs: Waiting time at the pharmacy, length of waiting line Outputs: Consultation time at the pharmacy |

High waiting times: low efficiency levels (less than 50% efficiency) are associated with high waiting times. |

| Mohammadi [56] | 2016 | Iran | Public hospitals | 67 | Cobb-Douglas production function | Inputs: Human resources (including net working hours of specialized workforce) and bed numbers (including the number of active beds) | Insufficient inputs: Inpatient service production levels were lower than expected in 40% of hospitals. A 10% increase in net working hours of specialized human resources would generate a 8.8% increase in average inpatient service production levels. A 10% increase in the number of active beds would generate a 1.1% increase in average inpatient service production levels. |

| Mahate [57] | 2016 | United Arab Emirates | Private and public hospitals in the UAE | 96 | DEA |

Inputs: Numbers of beds, doctors, dentists, nurses, pharmacists and allied health workforce, and administrative workforce Outputs: Numbers of treated inpatients, outpatients, ALS |

Waste of 41 to 52% of inputs during service delivery. |

| Kalhor [58] | 2016 | Iran | Tehran city general hospitals | 54 | DEA |

Inputs: Total numbers of FTE medical doctors, and nurses, numbers of supporting medical workforce including ancillary service workforce, and beds Outputs: Numbers of patient days, outpatient visits, patients receiving surgery, ALS |

Ownership type (lower efficiency of university hospitals because of more expenditures) |

| Kakemam [59] | 2016 | Iran | Hospitals of public, private, or social security ownership types in Tehran | 54 | DEA |

Inputs: Numbers of active beds, physicians, nurses, and other medical workforces Outputs: Numbers of outpatient visits, surgeries, and hospitalized days, ALS |

Lack of resource optimization. Poor adaptation of the sizes, types of practices, and ownerships of hospitals, affecting their technical efficiency. Approximately 70% of the hospitals were inefficient. |

| Hassanain [60] | 2016 | Saudi Arabia | Hospitals affiliated to the MoH | 12 | Lean | On-time start, room turnover times, percent of overrun cases, average weekly procedure volume and OR utilization | Ppoor hospital infrastructure, old technology, suboptimal management of human resources, the absence of employee engagement, frequent scheduling changes, inefficient process flow |

| Hamidi [61] | 2016 | Palestine | 22 government hospitals | 22 | DEA (frontier-based methods) |

Inputs: Numbers of beds, doctors, nurses, and non-medical workforce Outputs: Numbers of admitted patients, hospital days, operations, outpatient visits, ALS |

Mismanagement of available resources, shortage of the numbers of doctors and nurses and excess number of non-medical staff |

| Nabilou [62] | 2016 | Iran | Hospitals affiliated to Tehran University of Medical Sciences | 17 | DEA (Malmquist index) |

Inputs: Active beds, nurses, doctors and other workforces Outputs: outpatient admissions, bed-days, number of surgical operations |

Due to hospitals’ technological changes, a lack of knowledge of hospital workforce on proper applications of technology for patient treatment became the main cause of low hospital productivity and inefficiency. |

| Rezaei [63] | 2016 | Iran | Kurdistan teaching hospitals | 12 | DEA (frontier-based methods) |

Inputs: Numbers of active beds, nurses, physicians, and other workforce members Outputs: Inpatient admissions |

Waste of inputs during service delivery |

| Farzianpour [64] | 2017 | Iran | Training and non-training hospitals of Tabriz city | 19 | DEA |

Inputs: Numbers of physicians, total workforce, and active beds Outputs: Number of outpatients and BOR |

Poor management of human and financial resources. |

| Arfa [65] | 2017 | Tunisia | Public district hospitals | 105 | DEA |

Inputs: Numbers of physicians, surgical dentists, midwives, nurses and equivalents, and beds, operating budget Outputs: Outpatient visits in stomatology wards, outpatient visits in emergency wards, outpatient visits in external wards, numbers of admissions, and admissions in maternity wards |

Inadequate number of workforce, equipment, beds, and medical supply, health quality and lack of fitting operating budgets: tackling these sources of inefficiency would reduce net user needs and the bypassing of the public district hospitals, to increase their capacity utilization. Social health insurance should be turned into a direct purchaser of curative and preventive care for the public hospitals. |

| Aly Helal [66] | 2017 | Saudi Arabia | Public hospitals | 270 | DEA |

Inputs: Numbers of beds, doctors, nurses, and allied medical workforce Outputs: Numbers of individuals visiting admitted patients, radiography service beneficiaries, laboratory testing beneficiaries, and inpatients |

Excess inputs |

| Mousa [67] | 2017 | Saudi Arabia | Public hospitals | 270 | DEA |

Inputs: Numbers of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, allied health professionals, beds Outputs: Numbers of outpatient visits, inpatients, laboratory investigations, X-rays patients, X-rays films, total number of surgical operations |

Inadequate resources: some resources should be switched between regions to improve efficiency. |

| Moradi [68] | 2017 | Iran | Public hospitals | 11 | Pabon Lasso | ALS, BOR, BTR | Low number of hospital beds, and need for hospital expansion |

| Sultan [69] | 2017 | Jordan | General public hospitals | 27 | DEA |

Inputs: Numbers of beds, physicians, healthcare workforce, administrative workforce Outputs: Inpatient days, outpatient visits, emergency departments, and ambulances |

Diseconomies of scale affect the operational efficiency, poor management, poor productivity in outpatient services and low numbers of physicians. |

| Kassam [70] | 2017 | Iraq | Hospitals in Baghdad | 3 | DEA and Luenberger Productivity Indicator (LPI) |

Inputs: Numbers of doctors, nurses, and other health workforces Outputs: Numbers of outpatients, laboratory tests, radiology tests, sonar tests, emergency visits |

The cause of the inefficiencies is undetermined. |

| Rezaee [71] | 2018 | Iran | Hospitals affiliated with Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences | 15 | Pabon Lasso | Output: ALS, BOR, BTR | Excess inputs |

| Yazan Khalid Abed-Allah Migdadi [72] | 2018 | Jordan | Public hospitals | 15 | DEA |

Inputs: Numbers of physicians, nurses, and beds Outputs: ALS, number of Surgeries, BOR |

Low BOR |

| Sajadi [73] | 2018 | Iran | All hospitals in Isfahan City | 54 | Cross-sectional descriptive study comparing performance indicators | Outputs: BOR, BTR, bed-days, inpatients visits, number of surgeries in all types of hospitals, outpatient visits in all non-private hospitals, emergency visits in public and social security hospitals, and natural deliveries in public and semi-public hospitals | Inefficient use of limited resources |

*BOR bed occupancy rate, BTR bed turnover rate, ALS average length of stay, FTE Full Time Employee, MoH Ministry of Health

Various sources of hospital inefficiency were identified and divided into four themes, each with a set of subthemes: hospital products and services, hospital workforce, hospital services delivery, hospital system leakage (Table 2).

Table 2.

Source of inefficiency in Eastern Mediterranean hospitals and strategies for improvement

| Source of inefficiency | Common sources of inefficient performance | Proposed actions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital products and services | overuse or supply of equipment, investigations, and procedures |

- Inappropriate payment systems (fee-for-service payment mechanisms) - Misuse or inappropriate use of technology in patient treatment and diagnosis like imaging and lab services due to lack of knowledge and skills of health professional and lack of adopted evidenced-based guidelines. - Overuse or oversupply of equipment - Lack of or defective hospital equipment - Poor standards for use of technologies |

-Reform incentive and payment structures, developing appropriate tariff and payment systems (e.g. use capitation or diagnosis-related group mechanism for reimbursement) -Raising workforce awareness and training workforce and managers about new information systems and technologies -Raising workforce awareness of energy management through frequent training -Develop and implement clinical guidelines |

| Hospital workforce | inappropriate or costly workforce mix |

- Lack of or failure to use specialized managers in hospital administration - Suboptimal use of workforce capabilities, including those of physicians, nurses, paramedics, and support workforce, resulting in excess workforce in some departments - Inadequate management of hospital resources like workforce |

-Recruiting workforce based on hospital needs (both in terms of numbers and specialties required) -Preventing the recruitment and maintenance of specialist workforce who are not significantly relevant to hospital and patient needs. -Using work measurement and time management techniques for optimal use of the workforce with respect to the volume of hospital operations |

| unmotivated workforce |

- Lack of motivation due to high workload - Lack of workforce motivation in the public sector because of inadequate salaries |

-Introducing performance-based payments -Use appropriate incentive, reward and appraisal systems |

|

| Hospital services delivery | inappropriate hospital admissions and length of stay | - Inappropriate ALS*, unnecessary admissions, low BORs* and unnecessary referrals to specialists due to inadequate knowledge and training of workforce about best practice. |

-Developing and implementing policies to accelerate admission and discharge processes and increase the quality of services -Developing strategies to reduce ALS*, including full-time presence of physicians and modification of hospital funding policies -Establishing a two-way electronic referral system, to provide physicians with feedback -Effective marketing using appropriate customer information, and improving communication and customer loyalty |

| inappropriate hospital size (low use of infrastructure) |

- Inefficient hospital size, lack of scale efficiency and too many hospitals and inpatient beds in some areas, not enough in others - Suboptimal use of available capacities such as infrastructure and active beds, resulting in excess beds in some departments (lack of planning) |

-Modifying hospital size: selecting an efficient size and preventing hospital overdevelopment. if inefficient (downsizing or merging hospitals) -Making optimal use of hospital beds based on community needs. -Use of cost analysis and DEA model and other efficiency measurement models for incorporate inputs and output estimation into hospital planning. -Improving workforce, equipment, and beds based on evidence -Designing a basic framework for optimal resource allocation by health policymakers -Diversifying the outputs required for compensating hospital inefficiency -Redistributing hospital resources among regions -Training to raise knowledge about efficient admission practice |

|

| medical errors and suboptimal quality of care |

- Poor care management skills of physicians and other workforces. - Inadequate managerial skills and lack of training for hospital managers. - Inadequate skills and training of the hospital workforce. |

-Designing on-the-job training courses tailored to workforce roles. -Using experienced and well-educated managers with management or healthcare management degrees, performance evaluation of hospital managers and provide feedback -Introducing managers to management techniques and methods of economic analysis -Improve hygiene standards in hospitals; provide more continuity of care; undertake more clinical audits; monitor hospital performance |

|

| Hospital system leakages | waste, corruption and fraud |

- Inappropriate suboptimal allocation of funds among hospitals and unclear resource allocation guidance. - Hospital reliance on public funds and budgets, and lack of competition with other organizations. |

-Modifying hospital budget structures -Improve regulation/governance, including strong sanction mechanisms; assess transparency/vulnerability to corruption; undertake public spending tracking surveys; promote codes of conduct |

*BOR bed occupancy rate, BTR bed turnover rate, ALS average length of stay

The most frequent sources of inefficiency in EMR hospitals are excess workforce, excess beds, and inappropriate hospital sizes. Helal et al. [66] investigated the effect of health reforms (privatization) on the efficiency of 270 hospitals in Saudi Arabia and reported a 0.90 average efficiency in 2006 and a 0.92 average efficiency in 2014. The average efficiency of one is considered the best level of performance. Despite a reduction in inputs, outputs increased by 2%. Moreover, there was a 10.1% increase in the number of inpatients from 2006 to 2014. Therefore, reducing excess inputs such as excess workforce, excess beds or/and increasing outputs can be beneficial to hospitals. A 2013 analysis in Saudi Arabia showed that there was a reduction in the number of beds, doctors, nurses, and allied health workforce as inputs. Moreover, there was an increase in the number of inpatients, outpatients, the number of daily laboratory tests and the number daily of radiography services as outputs [39]. The most common strategies proposed in the included studies are: developing health policies for accurate recruitment planning, calculating the required number of beds for each community, and making proper use of hospital beds based on community needs.

Discussion

The purpose of this research was to examine the sources of hospital inefficiency and strategies available to increase hospital efficiency in the EMR. In recent years, there has been an increasing focus on hospital efficiency for health policymakers in developing countries. A total of 56 studies have been conducted on hospital efficiency in the EMR from January 1999 to May 2018. These studies have shown that hospital care is an economic activity requiring adequate funding and budgeting. As such, reducing inputs can improve performance and efficiency [56, 74].

The WHO Regional Office for the EMR classifies countries to there groups: high income countries (six countries), middle income countries (ten countries), and low income countries (six countries). The present research identified 56 articles on hospital efficiency in three high-income countries, five middle-income countries, and two low-income countries. General government expenditure allocated to health in the EMR countries remains between 2 and 16%, a low figure. Regarding hospital service utilization, the overall average bed occupancy rate and length of stays were 60.7% and 4.12 days, respectively, in the Region in 2013. Only a few countries have well-defined and functioning referral networks between hospitals and primary health care facilities, or between hospitals at different levels. Hospitals do not serve geographically defined catchment areas based on national policy mandates. Most countries are entrenched in the historical model of public provision and financing, and there is a mix of funding patterns, including public sector funds (through central government budgets and national insurance funds) and out-of-pocket payments made directly by users. In most countries, there is misalignment between the distribution of hospital beds and high-technology equipment and population health needs [4]. Contextual challenges exist, such as security issues, internal conflict and political volatility in EMR countries, leading to economic problems influencing health policies, health system budgets, and health system efficiency as a result [75, 76].

Some health system challenges are common to all EMR countries: “limited capacity in MoHs for evidence-based policy analysis and formulation and strategic planning through better use of information in adequate capacity to legislate, regulate and enforce rules and regulations” or “most countries lack national medicines policy” [75]. Both this study and the WHO have reported similar findings.

The most common input variables used in these studies were workforces numbers and the number of beds, while the most common output variables were the total number of outpatient visits, admissions and inpatient days. A systematic review of new approaches to measure hospital performance in LMICs in 2015 [77] identified seven key performance indicators. These included total inpatient days; recurrent expenditure per inpatient day; ALS; infection prevention rate; BOR; inpatient days per technical workforce; and unit cost of outpatient care. Seven performance indicators were also identified for high-income countries (HICs): mortality rate from emergency heart attack admissions after 28 days; mortality rate from emergency surgery after 30 days; number of patients on waiting lists; infection rate of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus per 10,000 bed-days; net profit; probability of workforce leaving within 12 months; and average healthcare commission rating [77].

On average, out-of-pocket payments differ between HICs and LMICs. In HICs, patients rarely pay directly for their care compared to LMICs where direct payment by patients is necessary due to lower insurance coverage. Furthermore, the mortality rate for non-elective admission is not the optimal output indicator for LMICs, as access to healthcare is a significant problem. These explain the differences in outputs between LMICs and HICs [77, 78].

The themes related to inefficiency extracted in this review, and the sources of inefficiency identified in the WHO report 2010 [11], highlight that studies have failed to address the issue of medical drugs. Using drug-related inputs and outputs can provide useful insights into drug-related sources of inefficiency in the EMR. For example, a study in Ethiopia used the cost of drug supply as input [79]. This can provide further insights into how to improve hospital efficiency.

In addition to excess workforce, excess beds and inappropriate hospital sizes, the inefficiency of hospitals in the EMR is also due to inappropriate workforce composition, lack of workforce motivation and inefficient use of health system inputs. According to a WHO report about National Health Accounts published in 2009, 15 to 25% of hospital inefficiency is related to workforce [80]. The workforce is at the core of the health system and accounts for almost half of the total health budget, in the form of wages and other payments [81]. The shortage of human resources is a major obstacle in implementing national healthcare plans, causing ineffective recruitment, inappropriate training, poor supervision, and suboptimal workforce distribution, which can further reduce efficiency [82]. Strategies to increase workforce efficiency focus on assessment and training based on needs, reviews of incentive policies, flexible contracts and performance-based payments [83].

Hospitals can result in lower efficiency if healthcare products and services are not optimal. Hospitals will face higher inputs against the specific output or lower outputs against the specific input. Excessive lengths of hospital stays, unnecessary admissions, and unnecessary referrals to specialists are examples of overuse of healthcare services. Reduced demand for hospital services and low BORs indicate underuse of available services [25–32]. A WHO report showed that suboptimal use of hospital resources, such as doctors, nurses, and beds, reduce demand for services and thus reduce hospital efficiency [82]. Optimal hospital management plays a vital role in optimizing healthcare services, improving hospital outcomes, and reducing costs [84–86]. Hospital managers and health policymakers can increase hospital efficiency and productivity through economies of scale. Strategies include optimizing hospital size, providing more products and services, and reducing ALS [38, 84–86].

Two of the principal sources of inefficiency in the EMR are inappropriate hospital sizes and excess numbers of active beds. These have been analyzed in studies conducted in countries outside the EMR, including in HICs [14, 21, 24–26, 33–35, 62]. These studies revealed the significant impact of hospital size and bed numbers on efficiency [87, 88]. The optimal number of active hospital beds typically lies between 200 and 300 beds. Generally, hospitals with less than 200 beds or more than 600 beds have higher costs [89]. According to international standards, a threshold BOR range between 84 and 85% indicates that use of hospital facilities and hospital resources are optimally efficient [90]. Therefore, optimizing hospital sizes and bed numbers can ensure that hospitals respond to population needs thus increasing efficiency. Indeed, it may be necessary for governments to build hospitals of a specific size, to take into account geographical considerations and difficulties accessing healthcare facilities.

The payment system has a vital role in improving hospital efficiency and productivity. In the EMR, payment systems are typically fee-for-service systems. In developed countries payments are often based on performance at clinical and organizational levels, increasing efficiency through performance incentives [91, 92]. Strategies to increase hospital efficiency include developing healthcare policies to implement appropriate payment systems, fair tariffs, and meticulous workforce recruitment plans, calculating required bed numbers for each community, making optimal use of hospital beds based on demand, and developing two-way electronic referral systems.

Conclusion

The results of this study have elucidated numerous sources of hospital inefficiency in the EMR. These sources should be addressed with targeted strategies, to improve hospital performance. Severe resource scarcity and increased costs of healthcare services, particularly in developing countries, require policymakers to ensure maximum use of available resources. Hospitals are highly complex, multidisciplinary social entities, whose performance can be improved through accurate, effective, and timely planning, organization, leadership, and management. Efficiency depends on multiple factors. As such, using various methods to measure hospital efficiency can be an effective strategy for managers and policymakers. Needs-based assessments and training, reviews of incentive policies, flexible contracts, performance-based payments, optimal hospital sizes based on community needs, increased resource availability and preservation of hospital social functions are crucial to increasing hospital efficiency.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Search strategy in Medline via PubMed.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ALS

Average length of stay

- BOR

Bed occupancy rate

- BTR

Bed turnover rate

- DEA

Data Envelopment Analysis

- EMR

Eastern Mediterranean Region

- FTE

Full Time Employee

- HICs

High-income countries

- LMICs

Low- and middle-income countries

- MoH

Ministry of Health

- SFA

Stochastic Frontier Analysis

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

MA and HR designed the research; MA and PI conducted it; MA and PI extracted the data; and MA, HR, VDB, and PI wrote the paper. MA had primary responsibility for final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study had no funding.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12913-019-4701-1.

References

- 1.Velasco-Garrido M, Busse R. Health technology assessment: an introduction to objectives, role of evidence, and structure in Europe. InHealth technology assessment: an introduction to objectives, role of evidence, and structure in Europe 2005. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mosadeghrad AM, Esfahani P, Nikafshar M. Hospitals’ efficiency in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis of two decades of research. J Payavard Salamat. 2017;11(3):318–331. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker D, Newbrander W. Tackling wastage and inefficiency in the health sector. 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office, World Health Organization. Introducing the framework for action for the hospital sector in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Regional Committee for the Eastern Mediterranean. EM/RC66/5. 2019. http://applications.emro.who.int/docs/RC_Technical_Papers_2019_5_en.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 27 Sept 2019.

- 5.World Health Organization . Improving hospital performance in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdullatif AA. Hospital care in WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region; an agenda for change. In: International Hospital Federation Reference Book 2005/2006. Ferney Voltaire: International Hospital Federation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pourreza A, Alipour V, Arabloo J, Bayati M, Ahadinezhad B. Health production and determinants of health systems performance in WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region. East Mediterr Health J. 2017;23(5):368–374. doi: 10.26719/2017.23.5.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrell MJ. The measurement of productive efficiency. J R Stat Soc Series A (General). 1957. 10.2307/2343100.

- 9.Charnes A, Cooper WW, Rhodes E. Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. Eur J Oper Res. 1978. 10.1016/0377-2217(78)90138-8.

- 10.Aigner D, Lovell CK, Schmidt P. Formulation and estimation of stochastic frontier production function models. J Econom. 1977. 10.1016/0304-4076(77)90052-5.

- 11.Pabon LH. Evaluating hospital performance through simultaneous application of several indicators. 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chisholm D, Evans DB. Improving health system efficiency as a means of moving towards universal coverage. World health report 2010 background paper, no. 28. http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/financing/healthreport/whr_background/en. Accessed 17 July 2018.

- 13.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009. 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Mitton C, Adair CE, McKenzie E, Patten SB, Perry BW. Knowledge transfer and exchange: review and synthesis of the literature. Milbank Q. 2007. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00506.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Hatam N. The role of Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) pattern in the efficiency of social security hospitals in Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2008;10(3):211–217. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization (WHO) 2015 Global Reference List of 100 Core Health Indicators. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.OECD. Health at a glance: Europe 2018: Organization for economic. Paris: OECD; 2018.

- 18.OECD Health Data 2001 . A comparative analysis of 30 countries; data sources, definitions and methods. Paris: OECD; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Shammari M. A multi-criteria data envelopment analysis model for measuring the productive efficiency of hospitals. Int J Oper Prod Man. 1999;19(9):879–891. doi: 10.1108/01443579910280205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramanathan R. Operations assessment of hospitals in the Sultanate of Oman. Int J Oper Prod Man. 2005. 10.1108/01443570510572231.

- 21.Hajialiafzali H, Moss J, Mahmood M. Efficiency measurement for hospitals owned by the Iranian social security organisation. J Med Syst. 2007. 10.1007/s10916-007-9051-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Goshtasebi A, Vahdaninia M, Gorgipour R, Samanpour A, Maftoon F, Farzadi F, et al. Assessing hospital performance by the Pabon lasso model. Iran J Public Health. 2009;38(2):119–124. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jandaghi G, Matin HZ, Doremami M, Aghaziyarati M. Efficiency evaluation of Qom public and private hospitals using data envelopment analysis. Eur J Econ Finance Adm Sci. 2010;22(2):83–91. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hatam N, Moslehi S, Askarian M, Shokrpour N, Keshtkaran A, Abbasi M. The efficiency of general public hospitals in Fars Province, Southern Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2010;12(2):138. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shahhoseini R, Tofighi S, Jaafaripooyan E, Safiaryan R. Efficiency measurement in developing countries: application of data envelopment analysis for Iranian hospitals. Health Serv Manag Res. 2011. 10.1258/hsmr.2010.010017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Ketabi S. Efficiency measurement of cardiac care units of Isfahan hospitals in Iran. J Med Syst. 2011. 10.1007/s10916-009-9351-0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Mohammadkarim B, Jamil S, Pejman H, Seyyed MH, Mostafa N. Combining multiple indicators to assess hospital performance in Iran using the Pabon Lasso model. Australas Med J. 2011. 10.4066/AMJ.2011.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Al-Shayea AM. Measuring hospital’s units efficiency: a data envelopment analysis approach. Int J Eng Technol. 2011;11(6):7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmadkiadaliri A, Haghparast-Bidgoli H, Zarei A. Measuring efficiency of general hospitals in the south of Iran. World Appl Sci J. 2011;13(6):1310–1316. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osmani AR. Technical efficiency of district hospitals in Afghanistan: a data envelopment analysis approach: Chulalongkorn University. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farzianpour F, Hosseini S, Amali T, Hosseini S, Hosseini SS. The evaluation of relative efficiency of teaching hospitals. Am J Appl Sci. 2012;9(3):392. doi: 10.3844/ajassp.2012.392.398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chaabouni S, Abednnadher C. Efficiency of public hospitals in Tunisia: a DEA with bootstrap application. Int J Behav Healthc Res. 2012. 10.1504/IJBHR.2012.051380.

- 33.Marnani AB, Sadeghifar J, Pourmohammadi K, Mostafaie D, Abolhalaj M, Bastani P. Performance assessment indicators: how DEA and Pabon lasso describe Iranian hospitals’ performance. Health Med. 2012;6(7):791–796. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheikhzadeh Y, Roudsari AV, Vahidi RG, Emrouznejad A, Dastgiri S. Public and private hospital services reform using data envelopment analysis to measure technical, scale, allocative, and cost efficiencies. Health Promot Perspect. 2012;2(1):28. doi: 10.5681/hpp.2012.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yusefzadeh H, Ghaderi H, Bagherzade R, Barouni M. The efficiency and budgeting of public hospitals: case study of Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2013;15(5):393. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.4742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gholipour K, Delgoshai B, Masudi-Asl I, Hajinabi K, Iezadi S. Comparing performance of Tabriz obstetrics and gynaecology hospitals managed as autonomous and budgetary units using Pabon Lasso method. Australas Med J. 2013. 10.4066/AMJ.2013.1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Arfa C, Sabri B. Appraising the efficiency of public hospitals in Tunisia. Future Healthc. 2013. 10.1007/s10754-013-9123-8.

- 38.Ajlouni M, Zyoud A, Jaber B, Shaheen H, Al-Natour M, Anshasi RJ. The relative efficiency of Jordanian public hospitals using data envelopment analysis and Pabon Lasso diagram. Glob J Bus Res. 2013;7(2):59–72. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abouel-Seoud M. Measuring efficiency of reformed public hospitals in Saudi Arabia: an application of data envelopment analysis. Int J Econ Manag Sci. 2013;2(9):44–53. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bastani P, Vatankhah S, Salehi M. Performance ratio analysis: a national study on Iranian hospitals affiliated to ministry of health and medical education. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42(8):876. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Younsi M. Performance of Tunisian public hospitals: a comparative assessment using the Pabon Lasso model. Hosp Res. 2014;3(4):159–166. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torabipour A, Najarzadeh M, Mohammad A, Farzianpour F, Ghasemzadeh R. Hospitals productivity measurement using data envelopment analysis technique. Iran J Public Health. 2014;43(11):1576. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rasool SA, Saboor A, Raashid M. Measuring efficiency of hospitals by DEA: an empirical evidence from Pakistan. Int Public Health J. 2014. 10.11591/.v3i2.4684.

- 44.Pourmohammadi K, Hatam N, Bastani P, Lotfi F. Estimating production function: a tool for Hospital Resource Management. Shiraz E Med J. 2014. 10.17795/semj23068.

- 45.Mehrtak M, Yusefzadeh H, Jaafaripooyan E. Pabon Lasso and data envelopment analysis: a complementary approach to hospital performance measurement. Glob J Health Sci. 2014. 10.5539/gjhs.v6n4p107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Lotfi F, Kalhor R, Bastani P, Zadeh NS, Eslamian M, Dehghani MR, et al. Various indicators for the assessment of hospitals’ performance status: differences and similarities. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(4):e12950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Kalhor R, Salehi A, Keshavarz A, Bastani P, Orojloo P. Assessing hospital performance in Iran using the Pabon Lasso model. Asia Pac J Health Manage. 2014;9(2):77. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goudarzi R, Pourreza A, Shokoohi M, Askari R, Mahdavi M, Moghri J. Technical efficiency of teaching hospitals in Iran: the use of stochastic frontier analysis, 1999–2011. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(2):91. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Askari R, Farzianpour F, Goudarzi R, Shafii M, Sojaei S. Efficiency evaluation of hospitals affiliated with Yazd University of Medical Sciences using quantitative approach of data envelopment analysis in the year 2001 to 2011. Pensee J. 2014;76:416–425. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adham D, Issac B, Sadeghi G, Mohammad P, Hossein A, Salarkhah E. Contemporary use of hospital efficiency indicators to evaluate hospital performance using the Pabon Lasso model. Eur J Bus Soc Sci. 2014;3(2):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Imamgholi S, Khatami Firouzabadi SMA, Goharinezhad S, Fadaei Dehcheshmeh N, Heidarinejad A, Azmal M. Assessing the efficiency of hospitals by using Pabon lasso graphic model. J Res Health. 2014;4(4):890–897. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shetabi HR, Mirbahari SQ, Nasiripour AA, Safi Keykale M, Mohammadi H, Esfandnia A, Safari S, Kazemi M, Mohammadi M. Evluating technical efficiency of Kermanshah city universities by means of data envelopment analysis model. Res J Med Sci. 2015. 10.3923/rjmsci.2015.53.57.

- 53.Masoompour SM, Petramfar P, Farhadi P, Mahdaviazad H. Five-year trend analysis of capacity utilization measures in a teaching hospital 2008–2012. Shiraz E-Med J. 2015. 10.17795/semj21176.

- 54.Chaabouni S, Abednnadher C. Cost efficiency of Tunisian public hospitals: a Bayesian comparison of random and fixed frontier models. J Knowl Econ. 2016. 10.1007/s13132-015-0245-8.

- 55.Safdar KA, Emrouznejad A, Dey PK. Assessing the queuing process using data envelopment analysis: an application in health centres. J Med Syst. 2016. 10.1007/s10916-015-0393-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Mohammadi H, Meskarpour-Amiri M. Estimation production function of inpatient services and input productivity: a cross-sectional study of Iran selected public hospitals. Hosp Pract Res. 2016;1(3):91–93. doi: 10.20286/hpr-010391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mahate A, Hamidi S. Frontier efficiency of hospitals in United Arab Emirates: an application of data envelopment analysis. J Hosp Adm. 2015. 10.5430/jha.v5n1p7.

- 58.Kalhor R, Amini S, Sokhanvar M, Lotfi F, Sharifi M, Kakemam E. Factors affecting the technical efficiency of general hospitals in Iran: data envelopment analysis. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2016. 10.1097/01.EPX.0000480717.13696.3c. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 59.Kakeman E, Forushani AR, Dargahi H. Technical efficiency of hospitals in Tehran. Iran Iran J Public Health. 2016;45(4):494. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hassanain M, Zamakhshary M, Farhat G, Al BA. Use of lean methodology to improve operating room efficiency in hospitals across the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2017. 10.1002/hpm.2334. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Hamidi S. Measuring efficiency of governmental hospitals in Palestine using stochastic frontier analysis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2016. 10.1186/s12962-016-0052-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Nabilou B, Yusefzadeh H, Rezapour A, Azar FEF, Safi PS, Asiabar AS, et al. The productivity and its barriers in public hospitals: case study of Iran. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2016;30:316. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rezaei S, Zandian H, Baniasadi A, Moghadam TZ, Delavari S, Delavari S. Measuring the efficiency of a hospital based on the econometric Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA) method. Electron Physician. 2016. 10.19082/2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Farzianpour F, Emami AH, Foroushani AR, Ghiasi A. Determining the technical efficiency of hospitals in Tabriz City using data envelopment analysis for 2013-2014. Glob J Health Sci. 2016. 10.5539/gjhs.v9n5p42.

- 65.Arfa C, Leleu H, Goaied M, van Mosseveld C. Measuring the capacity utilization of public district hospitals in tunisia: using dual data envelopment analysis approach. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016. 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Helal SMA, Elimam HA. Measuring the efficiency of health services areas in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia using data envelopment analysis (DEA): a comparative study between the years 2014 and 2006. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2017. 10.5539/ijef.v9n4p172.

- 67.Mousa W, Aldehayyat JS. Regional efficiency of healthcare services in Saudi Arabia. Middle East Dev J. 2018. 10.1080/17938120.2018.1443607.

- 68.Moradi G, Piroozi B, Safari H, Nasab NE, Bolbanabad AM, Yari A. Assessment of the efficiency of hospitals before and after the implementation of health sector evolution plan in Iran based on Pabon Lasso model. Iran J Public Health. 2017;46(3):389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sultan WI, Crispim J. Evaluating the productive efficiency of Jordanian public hospitals. Int J Bus Manage. 2016. 10.5539/ijbm.v12n1p68.

- 70.Ali AM, Kassam A. Efficiency analysis of healthcare sector. Eng Technol J. 2017;35(5 Part (A) Engineering):509–515. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rezaei S, Hajizadeh M, Bazyar M, Kazemi Karyani A, Jahani B, Karami MB. The impact of health sector evolution plan on the performance of hospitals in Iran: evidence from the Pabon Lasso model. Int J Health Gov. 2018. 10.1108/IJHG-09-2017-0046.

- 72.Migdadi YKA-A, Al-Momani HSM. The operational determinants of hospitals’ inpatients departments efficiency in Jordan. Int J Oper Res. 2018;32(1):1–23. doi: 10.1504/IJOR.2018.091199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sajadi HS, Sajadi ZS, Sajadi FA, Hadi M, Zahmatkesh M. The comparison of hospitals’ performance indicators before and after the Iran's hospital care transformations plan. J Educ Health Promot. 2017. 10.4103/jehp.jehp_134_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Goudarzi R, RjabiGilan N, Ghasemi SR, Reshadat S, Askari R, Ahmadian M. Efficiency measurement using econometric stochastic frontier analysis (SFA) method, case study: hospitals of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. J Kermanshah Univ Med Sci. 2014;17(10):666–672. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office, World Health Organization . Health systems in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: situation, challenges and gaps. High Level Expert Meetingon Health Priorities in the Eastern Mediterranean Region1–2March 2012. RDO/WP/12.5. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Blair I, Grivna M, Sharif AA. The “Arab World” is not a useful concept when addressing challenges to public health, public health education, and research in the Middle East. Front Public Health. 2014. 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Adhikari SR, Sapkota VP, Supakankunti S. A new approach of measuring hospital performance for low- and middle-income countries. J Korean Med Sci. 2015. 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.S2.S143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Waheb Y, Kamel L, Mena R. Cost analysis and efficiency indicators for health care: report number 3, summary output for El Gamhuria General Hospital, 1993–1994. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ali M, Debela M, Bamud T. Technical efficiency of selected hospitals in Eastern Ethiopia. Health Econ Rev. 2017. 10.1186/s13561-017-0161-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.World Health Organization (WHO) National Health Accounts database. Geneva: WHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hernandez P, Dräger S, Evans DB, Tan-Torres Edejer T, Dal Poz MR. Measuring expenditure for the health workforce: evidence and challenges. World health report 2006 background paper. http://www.who.int/nha/docs/Paper%20on%20HR.pdf. Accessed 7 July 2010.

- 82.World Health Organization (WHO) The world health report 2006 - working together for health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Huicho L, Scherpbier RW, Nkowane AM, Victora CG, Multi-Country Evaluation of IMCI Study Group. How much does quality of child care vary between workforce with differing durations of training? An observational multi-country study. Lancet. 2008. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61401-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.Mosadeghrad AM, Esfahani P, Afshari M. Strategies to improve hospital efficiency in Iran: A scoping review. Payesh. 2019;18(1):7–21.

- 85.Mannion R, Davies HT, Marshall M. Cultural characteristics of “high” and “low” performing hospitals. J Health Organ Manag. 2005;19(6):431–439. doi: 10.1108/14777260510629689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.West E. Management matters: the link between hospital organisation and quality of patient care. Qual Health Care. 2001;10(1):40–48. doi: 10.1136/qhc.10.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Roh C-Y, Jae Moon M, Jung C. Measuring performance of US nonprofit hospitals: do size and location matter? Public Perform Manage Rev. 2010. 10.2753/PMR1530-9576340102.

- 88.Yong K, Harris AH. Efficiency of hospitals in Victoria under casemix funding: a stochastic frontier approach. Australia: Centre for Health Program Evaluation; 1999.

- 89.Giancotti M, Guglielmo A, Mauro M. Efficiency and optimal size of hospitals: results of a systematic search. PLoS One. 2017. 10.1371/journal.pone.0174533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 90.Orendi J. Health-care organisation, hospital-bed occupancy, and MRSA. Lancet. 2008;371(9622):1401–1402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60610-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cylus J, Papanicolas I, Smith PC, editors. Health system efficiency: How to make measurement matter for policy and management [Internet] Copenhagen: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Walker S, Mason AR, Claxton K, Cookson R, Fenwick E, Fleetcroft R, et al. Value for money and the quality and outcomes framework in primary care in the UK NHS. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(574):e213–ee20. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X501859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Search strategy in Medline via PubMed.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.