Abstract

There is a widespread belief that neurogenesis exists in adult human brain, especially in the dentate gyrus, and it is to be maintained and, if possible, augmented with different stimuli including exercise and certain drugs. Here we examine the evidence for adult human neurogenesis and note important limitations of the methodologies used to study it. A balanced review of the literature and evaluation of the data indicate that adult neurogenesis in human brain is improbable. In fact, in several high quality recent studies in adult human brain, unlike in adult brains of other species, neurogenesis was not detectable. These findings suggest that the human brain requires a permanent set of neurons to maintain acquired knowledge for decades, which is essential for complex high cognitive functions unique to humans. Thus, stimulation and/or injection of neural stem cells into human brains may not only disrupt brain homeostatic systems but also disturb normal neuronal circuits. We propose that the focus of research should be the preservation of brain neurons by prevention of damage, not replacement.

Keywords: adult neurogenesis, neural stem cells, memory, bromodeoxyuridine, homeostasis, neuronal protection, DNA repair/methylation

Introduction

In rodents, monkeys and more recently humans, there have been hundreds of publications on neurogenesis (the birth of new neurons in the central nervous system (CNS) and spinal cord) during development through adulthood and into old age. Moreover, it is often assumed that new born neurons in the adult CNS mature and are integrated and function normally (Cope and Gould 2019). The purpose of this review is to analyze and synthesize the extant data on neurogenesis in normal and diseased adult humans. The surprising result is that there is no or minimal human adult neurogenesis (AN). To document this conclusion, we will first review the relevant human data, then the methodological issues for validly detecting neurogenesis, and finally the implications for treatment of neuropsychiatric diseases.

Adult human neurogenesis: what is the evidence?

Hundreds of studies in rodents have employed different interventions to stimulate AN (Chen et al., 2000; Arvidsson et al., 2002; Santarelli at al., 2003; Chen and Sun, 2007; Young, 2009; Chen and Wang, 2016) with the implicit or explicit assumption that new neurons will be beneficial and that positive results will be applicable to humans, especially adults with disease (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, depression and stroke) (Benraiss et al., 2001; Gutierrez-Fernandez et al., 2012; Boldrini, et al., 2013; Chen and Wang, 2016, Cope and Gould, 2019). As discussed below, this assumption may be incorrect. In fact, the bulk of the adult human data collected over the last 20 years has failed to prove AN occurs and is of any functional significance in our species.

After considering it theoretically possible on the basis of studies in reptiles, birds and small mammals, the possibility of human AN received again considerable attention in 1998 when Eriksson et al. took advantage of the fact that five cancer patients infused with 250 mg of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) for diagnostic purposes gave informed consent for their brains to be studied after death. One cancer patient with no BrdU infusion was used for control. These patients died 16 days to 2.1 years later (ages 57 to 72). In postmortem brain samples, occasional BrdU+ cells were detected in the dentate gyrus (DG), some of which were GFAP+ (astrocytes; see Table 1 for histological abbreviations and their meaning), while just over 20% of them were co-labeled with NSE or NeuN (putative neurons). The authors concluded that in humans over age fifty continued neurogenesis in the DG existed. They also suggested that there were neural stem cells (NSCs) in adult human brain ventricular-subventricular zone (VZ-SVZ), an area above the anterior horn of the lateral ventricle, the origin of the rostral migratory stream that continuously supplies neurons to the olfactory bulb in many animal species whose olfactory ventricle remains open. In humans, the olfactory ventricle closes during development and the hypocellular region has characteristic gaps devoid of cell bodies. Eriksson and colleagues also pointed out substantial interindividual variability in the number of BrdU+ cells and a decline in the number of BrdU+ cells detected in patients with longest interval between BrdU injection and histological assessment. They interpreted this observation to indicate a progressive death of the newly generated cells over time. This interpretation seems in agreement with Gould et al. 2001 who reported adult generated neurons had a transient existence and who also pointed out the difficulty in replicating AN results other than in already damaged brains. To us, a more plausible explanation for the observations in both studies is simply that damaged neurons, attempting to repair themselves, incorporate BrdU (see below) and continue to die so that eventually the longer the waiting period before histological evaluation, the less BrdU+ cells there are. In view of the metabolic cost of producing new cells in a complex already mature neuronal circuit, it is questionable that the brain would invest resources in producing new neurons to have them die soon after production.

Table 1.

Common antigens, and their corresponding abbreviations, for the detection of cell proliferation and differentiation. Antigen specificity is not absolute and may vary depending on whether use is in vitro or in vivo, developmental age, region, species, etc.

| Antigen | Description | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferative Markers | Ki67 | Cell proliferation protein marker; marks cells in G1, S, G2, and M phases; i.e. marks dividing progenitors | High |

| MCM-2 | Mini-chromosome maintenance Protein-2; marks cells in G1, S, G2, and M phases | High | |

| PCNA | Proliferating cell nuclear antigen - Cell proliferation protein marker; marks cells mostly in late G1-phase and S-phase | Low | |

| PHH3 | Phosphohistone-H3 (PHH3); mitosis-specific marker | High | |

| RR | Ribonucleotide reductase | High | |

| Progenitor Markers | BLBP | Brain lipid binding protein for neuronal precursors; highly specific marker of radial glia cells | High |

| GFAP | (see below); radial glia marker | Medium | |

| Nestin | Intermediate filament protein; progenitor marker | Medium | |

| Vimentin | Intermediate filament protein; progenitor marker; highly expressed in mesenchymal cells | Medium | |

| Tbr2 | Intermediate progenitor marker | High | |

| SOX2 | Marks immature, undifferentiated cells | Medium | |

| PAX6 | Early progenitor marker | High | |

| Immature neurons | DCX | Microtubule-associated phosphoprotein; Doublecortin, marker of early stage (immature) neurons, promotes dendritic growth and cell migration | Medium |

| MASH-1 | Transcription factor - mammalian achaete scute homolog-1; controlled by Hedgehog | High | |

| NeuroD1 | Transcription factor - specific for postmitotic cells; Promotes neuronal differentiation; also marks radial glia cells | High | |

| PSA-NCAM | Polysialic acid - Neural cell adhesion molecule; Facilitates cell motility - essential for migration, cell growth and synaptogenesis | Low | |

| Reelin | Glycoprotein secreted in developing cortex | Medium | |

| TBR1 | Member of T-box family of transcription factors; Involved in reginal and lamina identity (deep cortical layers) | High | |

| Neuronal markers | NeuN | Mature neuron marker; Neuronal nuclei marker (Aka, Fox3) - specific for postmitotic cells; Not expressed in Golgi, Purkinje, mitral cells, photoreceptors, cells of inferior olive, dentate nucleus, sympathetic ganglia cells, Dopamine cells of substantia nigra | High |

| NSE | Neuron specific enolase; expressed by cultured (and immature) oligodendrocytes and other glia under pathological conditions | Medium | |

| TUJ1 | Neuron marker for β-tubulin 3 (immature neurons) | High | |

| Non-neuronal markers | GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein – for astrocytes; progenitor marker | Low |

| GFAP δ | For stem cells not clearly dividing | Medium | |

| IBA-1 | Ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 -For microglia | High | |

| Olig-2 | For oligodendrocytes precursors and GABAergic progenitors | Medium | |

| S-100 | For astrocytes | High |

Starting in 1999, a few studies claimed there was neurogenesis in the neocortex and hippocampus in adult primates and the olfactory system in humans (Gould et al., 1999, 2001, 2007). However, these claims were not substantiated in non-human primates (Kornack and Rakic, 2001; Rakic 2002a,b,c; Koketsu et al., 2003; Breunig et al., 2007) or in humans (Sanai et al., 2004, 2011; Bhardwaj et al., 2006; Kempermann, 2006).

In 2004 Sanai et al. confirmed (using cell cultures from a large sample of adult human SVZs [n= 65 neurosurgical resections and n=45 autopsied brains], that the SVZ contained NSCs that could differentiate into immature neurons, TUJ1+, PSA-NCAM+ and a few DCX+ neuroblasts. However, the authors acknowledged a robust germinal capacity but no evidence of cells migrating in chains along the SVZ or olfactory peduncle to the olfactory bulb. In adult humans, the existence of NSC in the SVZ was later confirmed (van den Berge et al., 2011) as was the fact that these NSCs did not divide and migrate (Kempermann, 2006; Spalding et al., 2013).

In 2010 Knoth et al. studied neurogenesis in the DG employing DCX as the screening marker in n=54 deceased humans, ages 0-100. To confirm neurogenesis, they double labeled DCX+ cells with other neuronal markers including PCNA and found within the neurogenic niche of the DG (the granule cells layer) on a log-log scale of DCX+ cells/mm2 versus age (n=45, 1 day to 94 years), there was a linear decline from hundreds in fetuses to ~1 in the very old. However, the authors acknowledged that both DCX and PCNA might not be specific for newborn neurons. In their conclusion, Knoth and colleagues were very circumspect. They stated: “Our data alone cannot prove or disprove the true presence or absence of neurogenesis (in humans) at any age…”

Employing atmospheric atomic bomb-test-derived 14C in genomic DNA Spalding et al. (2013) concluded that one-third of human DG neurons turnover at a rate of 1.75% per year after studying deceased adults aged 19 to 92 (n=55 for hippocampal neurons and n=65 for non-neuronal cells). However, their conclusion that “neurons (in the hippocampus) are generated through adulthood and that the rates are comparable in middle aged humans and (9 months old) mice” is wrong. This conclusion is based on a calculation error that goes back to original data, in the mouse, reported by Ben Abdallah (2010). As pointed out by Lipp and Bonfanti (2016) and further commented by Parolisi et al, (2018) about 700 new granule cells out of 20 million in a 40 years old human corresponds to a mere 0.0035% of the total population. In a 9 months old mouse 416 new cells in a population of 0.5 million corresponds to 0.083% of the population. Obtaining the ratio to compare between species (0.0832/0.0035 = 23.77) makes it clear that the turnover rates are different by a very large factor; here more than 20 fold in the mouse than in human. Hence, based on their own data, what Spalding and colleagues (2013) actually show is that the adult human neurogenesis turnover rate in the human DG of the hippocampus is a tiny fraction of that in adult mice. Subsequently, using the same technique, they also detected minimal neurogenesis in the striatum (Ernst et al., 2014). The methodology involved in these studies is complex and requires separating neuronal from non-neuronal nuclei in a highspeed cell-sorter, separation of rosettes, isolation of the DNA and subsequent mass spectrometry to identify the 14C in the DNA (Spalding et al., 2005). The problems here are that, aside of issues of contamination, there are multiple assumptions and corrections by as much as >20%. One important assumption that has been received with some skepticism is that the 14C in pine tree rings is an accurate reflection of the 14C in the air. However, the authors conceded that in industrial cities this assumption may not be valid (Spalding et al., 2005). Also, the authors underestimated the amount of DNA repair and removal of methyl groups in DNA which was unknown in 2005 when their methodology was worked out (Spector and Johanson, 2014) and which could explain some of the variability in their data. Indeed, in a very active group of cells in the DG, the slow but continuous repair and removal/return of methyl groups explains best the incorporation of 14C in these aging neurons. Importantly, if cells are 14C negative the results suggest new neurons were not generated since new neurons cannot be created without carbon incorporation although it is formally possible that new neurons were generated using carbon from dead cells as happens with the transfer of BrdU incorporated in the DNA of dead cells into living ones (Spector and Johanson CE, 2007). However, if the cells are 14C positive, the positivity is not specific. The incorporation of the 14C isotope could be due to cell division or more likely to any one of several other possibilities including DNA repair/methylation and cell death, processes which are prominent in older specimens. This is why reports using this technique suggesting that there are no new neurons in the adult human cerebral cortex (Bhardwaj et al., 2006) or in the human olfactory bulb (Bergmann et al., 2012) (negative results) are correct as noted in the experiments described below while reports by the same group reporting human adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus (Spalding et al., 2013) and striatum (Ernst et al., 2014) are probably incorrect, or at least incomplete and controversial (Also see below.) Cellular DNA repair, methyl group removal/return, and apoptotic cell death differ in dissimilar structures. However, the result is that the 14C incorporation method cannot prove the birth of new neurons or the absence of new neurons in adult human brain.

In 2014 Doorn et al. studied clinically diagnosed and pathologically verified Parkinson’s disease patients (n=14, ages 59-96), healthy controls that had some α-synuclein pathology at autopsy (n=6, ages 56-91) and healthy controls without α-synuclein pathology (n=9, ages 62-92). To assess cell proliferation in the DG they employed MCM-2 staining to screen for newborn cells and used colocalization with IBA-1 to identify microglia. They found that, in the DG, over 90% of the very few MCM-2+ cells also stained for IBA-1 and thus were microglia.

In an extremely careful study of 23 brains from deceased individuals ages 0.2 to 59 years, Dennis et al. (2016) studied the SVZ and the DG subgranular zone (SGZ). They employed immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence in combination with unbiased stereology. To identify the phenotype of proliferating cells in the SVZ and SGZ, they double labeled cells with Ki67 and DCX, and then triple labeled them with TUJl or epidermal growth factor receptor, to identify neurons; or GFAP (astrocytes), IBA-1 (microglia) or Olig 2 (oligodendrocytes). Importantly, all studies were done blinded. The assumption was that triple staining would lessen the chance for false positives. By age 3, 60% of the Ki67+ cells in the SGZ co-stained with IBA-1 (and thus were microglia). At older ages, >99% of the Ki67+ cells stained with IBA-1. Thus, this study is consistent with Doorn et al. (2014) that the principal proliferating cells in the adult human DG are microglia not neurons. In the SVZ they replicated the results of Sanai et al. (2004) (up to 18 months) and the exponential decrease with aging for DCX immunostaining in the SGZ as shown by Knoth et al. (2010). The authors point out that the results are consistent with PCNA labelling in the infant human SVZ and rostral migratory stream, and that only a non-proliferative pool remains in the adult. They further indicate that PCNA-based immunohistochemistry studies overestimate proliferative events in human postmortem brain tissue.

A more recent paper by Mathews et al. (2017), looking at neurogenesis associated changes in gene expression (n=26, ages 18-88), is consistent with the results of Doorn et al. (2014) and Dennis et al. (2016). Interestingly, they point out that strongly GFAP+ profiles with large thick radiating processes found in many elderly adults are “consistent with the morphology of activated astrocytes.” Both, astrocyte activation and microglia activation, are common in neuro-inflammation and especially prominent in neurodegenerative brain diseases (Jang et al., 2013; Liddelow et al., 2017).

Sorrells et al. (2018) published a comprehensive study on hippocampal neurogenesis in humans. They used a total of n=59 post-mortem and post-operative samples of the hippocampus and investigated the presence of progenitor cells and neurons from fetal age to adulthood. Their controls (n=37) spanned from 14 gestational weeks to 77 years old and their samples from people with epilepsy (n=22) spanned 3 months to 64 years old. They also used n=12 Rhesus macaques. They employed multiple label detection with various combinations of Ki67, DCX, PSA-NCAM, BLBP, NeuN, GFAP, and other markers as reported in their supplementary table 3. The methodology included light, confocal and electron microscopy, RNAscope in situ hybridization and comparative gene transcription analysis. Their careful and exhaustive examination provided data in support of a rapid decrease of DG neurogenesis with age. They stated that in the monkey hippocampus SGZ proliferation was found in early postnatal life and diminished during juvenile development as was previously reported (Eckenhoff and Rakic, 1988; Kornack and Rakic, 1999); importantly, they concluded that “…neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus does not continue, or is extremely rare, in adult humans.” In a very thoughtful discussion they suggested that earlier studies that found low level DG neurogenesis in human adults were probably in error. They pointed out that DCX can be expressed by glial cells and that the BrdU+ cells in the Eriksson et al. (1998) paper “…could possibly be explained by processes not associated with cell division…” as suggested previously (Kuan et al., 2004; Breunig, et al., 2007; Gould, 2007; Spector and Johanson, 2014).

As commented by Snyder (2018), hopes of neuronal plasticity may not necessarily be lost, since the plasticity, due to addition of new neurons in rodents, may in humans be provided by the prolonged development of neurons, which in some cases may last decades. Andrae (2018) proposed to focus research efforts on methodologies to extend the period of normal neurogenesis so that this can be used to treat neurological disorders in adults. Whether this is possible will require future intense investigation.

A study by Cipriani et al. (2018) reports results in agreement with those of Sorrells and colleagues. This study, which included n=39 controls spanning 13 gestational weeks to 72 years old and n=5 Alzheimer’s disease cases ages 74 to 89, concluded that pools of “morphologically, antigenically, and topographically diverse neural progenitor cells are present in the human hippocampus from early developmental stages until adulthood, including in Alzheimer’s disease patients, while their neurogenic potential seems negligible in the adult.” As pointed out in a commentary by Arellano et al. (2018), the common finding of these separate, yet almost simultaneous studies, is very significant because the DG was considered the only structure in the adult human brain where the possibility of neurogenesis was still being considered. In non-human primates new neurons could also not be detected in this structure after puberty (Eckenhoff and Rakic, 1988).

Recently three studies suggested that there is neurogenesis in the DG. A study by Boldrini et al. (2018), in autopsied persons ages 14-79 (n=28) with no neuropsychiatric disease or treatment, states that there is continuous sustained neurogenesis throughout aging in the DG. However, this study is fraught with problems. One example can be seen in their figure 1H in which they claim a Nestin+ cell is an intermediate neuronal progenitor. This cell looks like a reactive astrocyte. However, since staining with IBA-1 or Olig-2 are not presented one cannot be sure how glial cells were ruled out. Microglia and astrocytes can be Nestin+ (Takamori et al., 2009). It is possible that they consistently misidentified non-neuronal diving cells for neurons. In agreement with this, Parolisi et al. (2018) also reviewed the evidence for AN and used humans and dolphins as examples of long living species with large brains to discuss its evolutionary implications. Parolisi and colleagues state that in the Boldrini paper “…various molecular markers were found associated to different stages of immature neurons, which do not show the typical aspect of recently generated neuroblasts.” In addition, Boldrini and colleagues claimed they could not compare their findings to those of Knoth or Sorrells because these studies did not use stereology. However, they did not compare their results to studies that did use stereology such as for instance Dennis et al. (2016). Commentaries by Lee and Thuret (2018) and Kuhn et al. (2018) stress the advantages of using stereology, the shorter post mortem delays and the healthier controls in Boldrini’s study. However, they do not mention advantages of any of the additional methodologies used in the Sorrells paper. Paredes et al. (2018) points out that “…stereology is only a useful technique if what is being counted is correctly identified.”

Another recent study claims that hippocampal neurogenesis is abundant in neurologically healthy subjects and that it drops sharply in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (Moreno-Jimenez at al., 2019). This study shows clear DCX staining in adult human brains. However, as established previously, DCX positivity is not sufficient to demonstrate new neurons (see for instance: Gomez-Climent et al., 2008; Luzzati et al., 2009; Klempin et al., 2011). In addition, the supposedly new neurons are in the wrong place, i.e. mostly away from the hilus and they look mature. Unfortunately, there is no documentation of any dividing cells or precursors and the authors offer no proof of the presence of cycling/dividing cells with progenitor morphology and molecular profiling (Sox2+, Nestin+, GFAP+). Also, what the authors called normal controls were in fact ill individuals (many had cancer). If there was abundant adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus, as the authors claim, it is puzzling that the hippocampus is not constantly growing. It seems logical to expect that, for it to stay the same size, old neurons must die and be removed at least at the same rate as the new ones repopulating it. Yet, we are unaware of any study showing “abundant” adult apoptosis concomitant with correspondingly abundant neurogenesis.

A third paper claims that human hippocampal neurogenesis persists in aged adults and Alzheimer’s disease patients (Tobin et al., 2019). These authors are aware of the results of Moreno-Jimenez et al. (2019), but do not critically reflect on the differences found in reference to the amount of putative adult neurogenesis in the Alzheimer’s patients. They do acknowledge that they do not observe a correlation between level of neurogenesis and amyloid deposits or fibrillary tangles. In a careful examination of their figures we have failed to identify any clear evidence of new born neurons on their way to become adult neurons in process of being incorporated into the DG circuitry. Needless to say, any progenitor could become glia instead of neuron and there is no IBA-1 staining to, at least, rule out microglia. While extensively critical of the results in Sorrells et al. (2018), the authors do not comment on the results of Cipriani et al. (2018), which are in agreement with those of Sorrells et al. (2018).

Thus, as it now stands, the studies by Boldrini et al., (2018), Tobin et al., (2019) and Moreno-Jimenez (2019) are at odds with the works of Knoth et al. (2010), Doorn et al. (2014), Dennis et al. (2016), Mathews et al. (2017), Cipriani et al. (2018), and Sorrells et al. (2018). A commentary by Kempermann et al. (2018) points out the need to very seriously consider all technical issues “…for a full evaluation of the evidence.” We could not agree more. However, the assertion that the “…functional contribution that new neurons would make to human cognition is not negligible” is not consistent with the data summarized above. There is, in fact, no evidence that would clearly indicate human cognition would weaken or diminish if there was no AN in the hippocampus. In rats, it is worth noting that in a technical tour de force employing a pharmacogenetic model, Groves et al., (2013) showed that ablating adult neurogenesis in the DG showed no difference from controls in spatial pattern separation, spatial learning, or contextual or cued fear conditioning. A meta-analysis of all published studies also showed no effect for ablation of adult neurogenesis on dentate function but did find remarkable high levels of heterogeneity among studies of hippocampal function. Moreover, in agreement with the results of Groves et al. (2013), in a paper entitled “A transgenic rat for specifically inhibiting adult neurogenesis”, Snyder et al. (2016) reported that blockade of neurogenesis in the hippocampus did not affect anxiety levels or patterns of exploration. The Kempermann et al., (2018) commentary also fails to consider, for instance, Akers et al. (2014) who suggests that hippocampal AN may contribute to forgetting. Or as Mongiat and Schinder (2014) pointed out in their commentary on Akers’ paper, adding new neurons (in the DG) “…will still impose a cost to network stability.” Thus, adding new neurons might, in fact, be counterproductive. Hence, we agree that standardization of methodologies is a crucial step towards a possible solution to the contradictions and controversies in the field and, as Fred Gage (2019) suggests, “the creation of open-access brain banks with tissues more ideally suited to these types of studies” may be an essential first step.

Finally, it is worth nothing that the studies of Knoth et al. (2010), Dennis et al. (2016), Sorrells et al. (2018), and Cipriani et al. (2018) had built in internal controls. Using the same methodology they found abundant neurogenesis in unborn and young humans, which in all four studies declined to undetectable levels or minimal neurogenesis in adults and elderly humans and thus, the methods they employed were robust in detecting neurogenesis when it occurred. In other words, the methodologies employed in these four studies have face validity and are responsive to change.

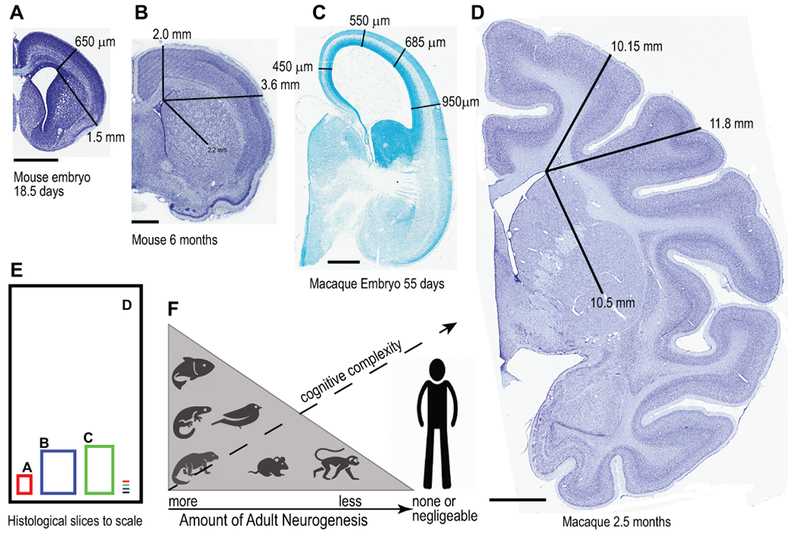

Human brain size has also been hypothesized to be an important limiting factor for AN (Paredes et al., 2016). These authors highlighted the tremendous differences in distances that separate cell origin and destination in the different species and discuss the fact that migration would be extremely difficult in developed large brains due to obstacles such as intervening white matter. We also show this in our Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(A-E) Comparison of brain sizes and some migratory distances to illustrate the large differences among mouse and macaque monkey at different developmental points. (F) Amount of adult neurogenesis from “more” in fish, salamanders and other reptiles to “substantial” in birds and rodents, to “less” in monkeys and finally to “none, negligible or not detectable” in humans. The capacity for adult neurogenesis seems negatively correlated to the cognitive capacity in the different species so that the less cognitive complexity the more likely adult neurogenesis is present. Rakic (1985) postulated that humans, throughout evolution, lost their capacity to regenerate neurons in exchange for stability in the neural networks so that processes of memory, learning and higher cognitive functions were favored. Scale bars: 1.0 mm (A-C), 4.0 mm in (D). Macaque tissue examples are from MacBrainResource.org.

In summary, almost 100 years ago with their meticulous histological studies, anatomists such as Kolliker, His, and Ramon y Cajal correctly indicated that there is no human AN. They suggested that nerve cells are responsible for the most precious human mental functions and are irreplaceable under normal conditions. In other words, as Rakic (1985) suggested “…a prolonged period of interaction with the environment, as pronounced as it is in all primates, especially humans, requires a stable set of neurons to retain acquired experiences…” The question is why do some studies still provide controversial results interpreted as evidence that there is human AN? We believe that methodological issues are at the center of the controversy.

Methodological Issues

Among the technical issues that may contribute to, what we consider, the erroneous idea of human AN there are problems unique to dealing with human samples (e.g. the difficulty in assuring homogenous postmortem delays before fixation and processing while some markers are degrading), problems of translation since the results in other species have not been translatable to humans and general technical problems of marker specificity, toxicity, detection, quantitative methodologies, proper use of controls, and even expression differences between brain regions or at different developmental stages. Because the renewed interest in AN was sparked by studies using BrdU, which is still the most commonly used of the thymidine analogues and because much work on this subject has been done in mice and uses a host of different neuronal and non-neuronal markers, we focus our technical review on these issues.

The use and misuse of BrdU

The use of BrdU as a specific and decisive marker of cell division has been particularly misleading in the large AN field. In part, because many authors continue to ignore the warnings expressed in many reviews (e.g. Taupin, 2007; Spector and Johanson, 2007; Levkoff et al., 2008; Ross et al., 2008; Duque and Rakic 2011, 2015; Lipp and Bonfanti, 2016) about the possibility of false BrdU labeling or the erroneous interpretation of such labeling. Hence, many researchers take uncritically any immunolabeling of the cell nucleus, and even perinuclear cytoplasm, as a definitive sign of cell division and therefore as evidence of the production of new neurons. Of course, BrdU does label dividing cells. However, the possibility that BrdU positivity may be due to attempts of cells to repair themselves or a sign of cell death (apoptosis) are usually neglected or understated. Excitation of the brain by running and/or induced epilepsy, both which stimulate DNA synthesis and BrdU positivity, were interpreted as production of new neurons (van Praag et al., 1999; Parent and Lowenstein, 2002; Jakubs et al., 2006). The fact that, despite supposedly producing new useful neurons in the hippocampus in epileptic animals and human cases, the hippocampus may become smaller rather than bigger is neglected.

BrdU’s toxicity has been well documented including, among others, its detrimental effects on chromosomes and DNA stability, the cell cycle, cell differentiation and survival (Hsu and Somers, 1961; Webster et al., 1973; Bannigan and Langman, 1979; Saffhill and Ockey, 1985; Biggers et al., 1987; Kolb et al., 1999; Sekerkova et al., 2004; Breunig et al., 2007; Lehner et al., 2011; Morris, 1991). Moreover, BrdU labeling may signify cell death rather than renewal. In an experiment in which unilateral ligation of the internal carotid artery caused a large number of BrdU+ cells in the hippocampus on the side of the ligation with subsequent loss of labelled neurons (Kuan et al., 2004), many BrdU+ cells could be double labeled with the Tunnel method as a sign of cell death. Hence, to continue to ignore or downplay the toxicity of BrdU and caveats concerning its utility only serves to add to the confusion.

The use and misuse of inbred animal models, particularly mice

One fundamental and very disturbing fact with most laboratory rat and mouse models is that these animals have been inbred for hundreds of generations. Hence, it is unlikely that the laboratory animal is even a good model of a true “wild” one. In fact, while many studies have indicated the exuberant existence of AN in the hippocampus of laboratory mice the concept of AN in the real “wild” mouse hippocampus is questionable. Take for instance the report by Hauser et al. (2009) in which the authors captured male and female wood mice in a park around the University of Zurich and found that wheel running had no impact on cell proliferation, neurogenesis or cell death in their hippocampi.

There are some advantages to inbred species, especially when studying genetics, because the similarity among individuals may facilitate the isolation of genes involved in particular traits. But, it is clear that inbreeding has made our laboratory animals rather different than their wild counterparts. In humans, the same is true. Because of cultural, political or geographic factors human inbreeding has resulted in populations experiencing different sorts of genetic problems (e.g. early onset Alzheimer’s disease) and which can facilitate the isolation and study of the genes involved.

Mice and humans went on their own evolutionary paths tens of millions of years ago. So, each species developed their own unique features. There are many analogous structures and systems but they are not always homologous. Rodents are not a small version of humans which may very well be why over, and over again, many treatments that work in rodents fail in humans.

The Limitations of antibodies and marker specificity

Specific markers for NSC and/or newborn cells may not be as specific as expected. Their expression could be transient, intermittent, species dependent or could be missed completely for technical reasons. Even if the labeling is not an artifact the function of the marked cell may be different from the expectations of the experimentalist. For instance, microglia may be produced and detected as adult new born cells but, they are not neurons and will not become neurons. They may have a transient and specific function such as in the clearing of dead cells (Streit, 2000; Lu et al., 2011), which could also be cleared by immature neuroblasts (Sierra et al., 2010). An additional confound is the possibility of the retention of immature neurons which maintain their markers and morphology and which may mature much later in life. Unfortunately, events such as the birth of the organism are not good predictors of the brain’s developmental state and it is difficult to detect and correctly interpret cellular events in the nonlinearly scaling lifespan of different species (Charvet and Finlay, 2018).

Table 1 lists some of the commonly employed antigens for cell division and a few presumably specific neuronal markers. However, specificity is often not absolute and this also is either ignored or neglected by many authors. For instance, the neuronal marker NSE is expressed by cultured (and immature) oligodendrocytes and other glia under pathological conditions. DCX and PSA-NCAM, not only mark immature neurons in nonhuman species, they also mark mature neurons and glia cells in humans. To expand on the idea of the need to be careful when interpreting the expression and specificity of any sort of labeling, take as an example the case of the commonly used marker NeuN (for a review see Guselnikova and Korzhevskiy, 2015). Its expression is commonly believed to be exclusive of neurons, but not all neurons, most notably it does not label cerebellar Golgi, Purkinje, or dentate nucleus cells; mitral cells of the olfactory bulb, photoreceptors and most cells of the inner nuclear layer of the retina, neurons of inferior olive, dorsal cochlear nucleus, gamma motor neurons, sympathetic chain ganglia cells or cortical Cajal-Retzius cells, and was deemed unreliable to label dopaminergic cells of the (rat) substantia nigra. To complicate matters, in vitro experiments indicate that GFAP+ (astrocytes) cells are also NeuN+. So, are these cells in vitro, neurons or glia? Their morphology is consistent with that of astrocytes.

Because it is difficult to find a single method in neurobiology that stands alone and is sufficient to demonstrate any theory, further measures to minimize the possibility of error include, for instance, the use of confocal microscopy with multiple planar views, when using immunofluorescence, to be certain an antigen is actually in the assigned cell. This avoids the common mistake of identifying a satellite glial cell for a neuron. Species specific limitations are particularly important when employing genetic techniques, viral vectors, electroporation, recombinase-based systems, and transplants. For example, genetic models in animals include, among others, knock-in, knockout, transgenic, Cre/lox P, inducible Cre and mosaic analysis (Kempermann, 2006; Breunig et al., 2007). But, in general, these methods are not usable in humans, except when there are “experiments of nature” (e.g. human knockouts).

Pharmacological Implications for the treatment of neuropsychiatric diseases

Brain Protection, Nourishment and Homeostasis.

In view of the lack of, or minimal, neurogenesis in the adult human brain and possibly in the DG, one might expect a really robust protective and nourishing environment for the brain. This would prevent damage and provide a stable environment since the neurons must function smoothly and last intact for decades. Surrounding the adult human brain are a myriad of anatomical, physiological and homeostatic systems that provide a near constant internal milieu (Table 2).

Table 2.

Architecture and Systems for brain protection, nourishment and homeostasis.

| Anatomical Protection |

| a) Skull |

| b) Cerebrospinal fluid (brain buoyancy with operational brain weight 40 grams) |

| c) Blood-brain barrier (BBB) – Tight junctions in cerebral capillaries |

| d) Blood CSF (B-CSF) barriers (see text) |

| Physiological Protection |

| a) Multiple specific and non-specific efflux transport systems |

| 1. At BBB |

| 2. At choroid plexus (CP) |

| 3. Via turnover of CSF |

| b) Metabolism of some compounds |

| 1. At CP |

| 2. At BBB (e.g. dopamine) |

| Nourishment of brain |

| a) At BBB |

| 1. Macronutrients (e.g. glucose, fatty and amino acids) |

| 2. Micronutrients (e.g. riboflavin and thiamine) |

| 3. Ions (e.g. iron but not sodium of chloride) |

| b) At B-CSF barrier via CP into CSF |

| 1. Micronutrients (e.g. vitamin C and folate) |

| 2. Ions (e.g. sodium, chloride and bicarbonate) |

| 3. Growth factors and peptide hormones (e.g. prolactin) |

| Remarkable Mechanisms for Brain Homeostasis at or within |

| a) CP and CSF |

| b) BBB |

| c) Brain cells |

Anatomically the skull encased brain is isolated from the blood by capillaries with tight junctions i.e., the blood brain barrier (BBB; Spector, 2009; 2010; Spector and Johanson, 2010; 2014). The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is also isolated from the blood by tight junctions between the epithelial cells in the choroid plexus (CP), which secretes the CSF, and the tight junctions in the layers of the arachnoid cell membrane which encompasses the CSF (Spector et al., 2015a,b). Thus, the CP and arachnoid membrane make up the blood-cerebrospinal fluid (B-CSF) barrier. There is however ready exchange of small molecules between CSF and brain; in other words, the brain and CSF, which also provides buoyancy for the brain, can be considered a single compartment isolated from the blood and protected by the skull (Spector et al., 2015a,b). Of course, within the central compartment, astrocytes and microglia constantly sculpt and protect neurons, and help provide a stable milieu.

Physiologically, these barriers provide anatomical protection against water-soluble, ionic and large molecules entering the brain from the blood (Spector, 2009; Spector and Johanson, 2010). However, highly lipid soluble compounds and water can freely enter brain from blood. Moreover, at both the BBB and B-CSF barrier there are multiple specialized active-transport “pumps” to extrude unwanted endogenous and exogenous molecules from the central compartment back into the blood (Spector, 2010; Spector and Johanson, 2010); importantly for pharmacologists, these protective systems can also prevent the entry of therapeutic drugs. For instance, in the case of meningitis, penicillin and its congeners, which are potentially useful treatments, are vigorously transported by organic acid transporter-3 out of CSF (Spector, 2010). This problem was overcome by the finding that the long half-life ceftriaxone was not transported by organic acid transporter-3 and thus became the drug of choice for most cases of meningitis. In other cases, e.g., the congenital vitamin transport disorders, exemplified by the lack of riboflavin, thiamine or folate transporters into brain at the BBB, the barrier to vitamin entry (because of the missing transport system) was overcome by giving massive doses of the appropriate vitamin and thus preventing the severe neurological damage associated with these vitamin transport disorders (Spector, 2014). There are some drugs whose entry is facilitated by “riding” into brain on endogenous transport systems, e.g., diphenhydramine, or others that avoid the barriers e.g., the lipid soluble pentothal. So, the barriers that work effectively to protect the brain from toxic chemicals and drugs (e.g., ivermectin by P-glycoprotein at the BBB) (Spector 2010) are the same that produce significant problems for the delivery of potentially useful drugs into the central nervous system.

In terms of brain nourishment, both the BBB and CP contribute via separate saturable systems (Spector 2009; Spector et al., 2015a,b). Many of these systems at the barriers also provide homeostasis and participate in maintaining a constant internal milieu for the brain. In fact, most nutrients including glucose and vitamins in the CSF and brain as well as ions are buffered from changes in concentrations in blood (Spector 2009; Spector and al., 2015a,b). For example, large increases or decreases in blood potassium minimally change the potassium concentration in CSF and the extracellular space of brain. Similarly, large drops in many vitamin blood levels are not reflected in brain because of the vitamin homeostatic systems. An excellent example is scurvy in which the rest of the body is scorbutic but the brain until the very end retains enough vitamin C to function - a remarkably protective result (Spector, 2009). This is not due to lack of turnover, but due to the efficacy of the sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter-2 in the CP to pump the vitamin into CSF and brain at very low blood concentrations (Spector, 2009). With these multiple complex systems for protection, nourishment and homeostasis, the adult human brain can function optimally. Without even one of them (e.g., the thiamine transport -homeostatic system) at the BBB and B-CSF barriers due to congenital absence or severe deficiency states, irreversible neurological damage occurs (Spector, 2014).

Thus, in the brain, unlike the gut, skin and liver which are exposed to both chemical and, in the case of skin, physical toxins (e.g., UV light), the non-replicating neurons in adult human brain are protected and nourished by a large number of discrete systems as noted above. These latter tissues especially the gut and skin, in fact, have programmed turnover mechanisms – with stem cells in the crypts in the gut and basal layers of the skin dividing, renewing and replacing the dead superficial cells. Even bone slowly remodels. The neurons in the brain do not and thus require exquisite protection for longevity.

Transplantation of Neural Stem Cells: Example of Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease is due to a decrease of dopamine input to the striatum from dopaminergic cells in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc). Transplantation of dopamine- producing NSC into the putamen or SN was tested in two careful double-blind trials (Freed et al., 2001; Olanow et al., 2003) in which cyclosporine was employed to prevent rejection. Both trials provided clear evidence of stem cell survival with production of dopamine but there was no clear benefit, although there was possibly a treatment effect in milder patients. However, in both trials, there was disabling “off-levodopa therapy” dyskinesia; in the later trial 56% of the transplanted patients were affected and Olanow and colleagues concluded that “fetal (stem cell) transplantation cannot be recommended as a therapy for Parkinson’s disease.” They hypothesized the dyskinesia was due to “incomplete or aberrant re-innervation of the striatum.” Since these trials were completed over fifteen years ago, there has been substantial new information about the biology of the SN. For example, in rats, there is tonic somatodendritic dopamine release in the SN with the extracellular SN concentration of dopamine ~80 nM (Yee et al., 2019). This is enough to saturate DA D2 receptors. The tonic release of DA is not due to action potentials. Whether this occurs in humans is unknown but probable. This finding greatly complicates the traditional understanding of SN biology. For example, how could transplantation of dopamine neurons into the putamen of Parkinson’s patients influence dopamine levels in the SN?

Also, since there is renewed interest in transplanting human iPS cell-derived dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s disease there are many issues that require resolution. In a primate model of Parkinson’s disease employing human iPS cell-derived neurons from four patients with PD and four controls, Kikuchi et al. (2017) grafted these eight cell lines into the putamen of monkeys. The grafted monkeys improved and there was no dyskinesia unlike humans as noted in above. The grafted cells from both normal and Parkinson’s disease patients produced substantial dopamine. Kikuchi et al. used the immune-suppressive drug (FK506) to counter rejection. In this study there was tremendous inter-individual variation in the number of DA cells in the putamen that were tyrosine hydroxylase positive (a putative measure of DA cells). One of the issues that became apparent is how an investigator should select “good donor cells” for transplantation. A further complication is the finding that how you grow the cells matters, e.g., the importance of timely vitamin C in the growth medium to establish crucial epigenetic modifications to ensure maximal utility of the donor cells (Wulansari et al., 2017). Finally, even if you can pick a “good donor” cell line for transplantation, the pharmaceutical issues of scaling up to potentially tens of thousands of transplants employing FDA-required good laboratory practice and keeping the cells stable are formidable challenges. Whether transplantation of stem cells is hopeless in Parkinson’s disease or if a different paradigm might work remains to be established.

Is there neurogenesis after stroke?

Over 90% of strokes are ischemic due to interference with brain blood flow because of intra-arterial clotting or less commonly an embolus (Spector, 2016). At present, there are two established (proven) treatments although of modest efficacy: intravenous tissue plasminogen activator to dissolve the clot or endovascular therapy to remove or relieve the obstructing clot. Both require treatment within a few hours after the incident for a potential beneficial effect (Chen and Wang 2016). In animal models, with and without stimulation, many reports found meaningful neurogenesis in the penumbral region (the region surrounding the core necrotic region) after stroke (e.g., Pencea et al., 2001; Parent et al., 2002; Kernie and Parent 2010; George and Steinberg, 2015). Although early reports suggested that there was neurogenesis in the penumbral region after stroke in humans (Jin et al., 2006; Lindvall and Kokaia, 2015), these new neurons or old neurons unsuccessful attempts at dividing were not permanent. In the Spalding et al., (2013) study of 14C dating of neurons in the penumbra of stroke for new neuron birth dating, the authors could not detect any (lasting) neurogenesis in the penumbra. Lindwall and Kokaia (2015) pointed out the difficult task for the production of useful replacement neurons in human stroke: the new neurons must survive, migrate to the appropriate place, differentiate into the phenotype of dead neurons that need to be replaced and finally be integrated into functional circuits with correct synaptic connectivity. This apparently does not happen (Spalding et al., 2013). In summary, there is no evidence for human AN after a stroke. Moreover, in stroke, even if you could stimulate neurons with growth factors to divide, the challenge of turning such newborn neurons into functioning integrated neurons in adult brain seems challenging and, so far, impossible. It is worth noting that Kondziolka et al., (2005) did a controlled transplantation trial in stable (for 2 months) post-stroke patients with 5 to 10 million human neuronal cells. This trial was negative and roundly criticized by Bakay (2005).

Drug Therapy and Neurogenesis

As documented above, in adult monkeys there is minimal and in humans undetectable AN, except possibly in the DG. In rodents, there are hundreds of reports describing interventions that increase neurogenesis e.g., exercise, lithium, tricyclic anti-depressants and serotonin selective receptor inhibitors like fluoxetine and, in some studies, these interventions improved cognition (Gould et al., 2001; Santarelli et al., 2003; Foland et al., 2008; Young, 2009). However, there are multiple technical problems with these studies. For example, focusing on lithium used to treat manic-depressive disease, Chen et al., (2000) employed high dose BrdU to detect new neurons in the DG in control versus lithium treated mice. After four weeks of lithium treatment, they found a 25% increase in BrdU+ cells in the DG. Moreover, they found 65% of the BrdU+ cells in both control and lithium treated mice were NeuN+, suggesting they were neurons. However, they did not measure the blood levels of BrdU which could have been increased due to the lithium treatment (Kempermann, 2006; Breunig et al., 2007; Spector and Johanson 2007). If the blood levels of BrdU were 25% higher in the lithium group, their results could be explained by the altered pharmacokinetics of BrdU which would also explain why there was no increase in the percentage of NeuN+ cells in the control and lithium treated mice. Similar types of issues can be raised in the putative increase in dentate neurogenesis in the anti-depressant studies (e.g., Santerelli et al., 2003). Moreover, even if there is increased neurogenesis in the DG of animals with lithium and/or anti-depressants, this does not prove neurogenesis in the DG gyrus is the cause of the improved animal cognition. However, many authors, as noted above, have either explicitly or implicitly suggested that these rodent study results can be applied to human adults (Santarelli et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2000, Cape and Gould 2019). Further complicating the rodent studies, Snyder et al. (2009) showed that adult born hippocampal neurons are more numerous and more involved in behaviors in rats than in mice. Hence, what to believe, rats or mice?

In an autopsy cross sectional study of patients with major depression, Boldrini et al., (2013) reported a larger DG and more granule cell neurons in anti-depressant treated patients than in untreated control patients. However, they concluded that postmortem studies “are correlative” and do not prove causality, i.e., that the antidepressant increased dentate size is due to neurogenesis. In fact, there are many serious problems associated with the hypothesis that anti-depressants work by rapidly increasing neurogenesis in the DG. In monkeys, if AN was to happen, then as reported by Kohler et al. (2011), it would take longer than 6 months for new neurons in the DG to connect and be integrated in a functionally meaningful way. Moreover, the well-known observation that ketamine can overcome severe depression in hours undercuts the neurogenic hypothesis (i.e. that anti-depressants work by increasing neurogenesis) and favors the chemical imbalance hypothesis.

In view of the finding that there is minimal or, in some studies, no detectable human AN it is difficult to argue that several diseases (e.g., depression, manic depressive disease, Alzheimer’s disease, dementia) are due to insufficient neurogenesis in the DG. Even if one could increase neurogenesis with safe interventions, appropriate cellular integration into functioning systems is doubtful since the distances axons must travel to then correctly connect to their targets are much longer and more complex in human than in rodent brains (Fig 1) and the developmental signals and chemicals to direct axonal growth are long gone. In addition, it seems unlikely that diseases of such diverse pathogenesis, affecting different cellular populations in dissimilar brain structures would all be due to the lack of, or remediated by, AN. The literature favoring the existence of human AN seem to imply that it must exist because AN exists in other species. However, this is intrinsically inconsistent with the uniqueness of species specific capacities and even with evolution.

In our view, a beneficial result of stimulating neurogenesis or transplanting NSCs into adult human brain is, at present, just a hypothesis. The experimental finding in Parkinson’s disease noted above in which transplanted neurons functioned (and made dopamine) but made many patients worse is most instructive. Until there is clarification of this issue, i.e., whether transplantation or stimulation of neurogenesis is helpful or, as suggested by Rakic (1985) and Akers et al., (2014) potentially harmful, a better approach for neuroscientists and pharmacologists would be to promote optimal use of the brain by ensuring ideal care of the body (e.g., good diet, normal weight, no smoking) and to develop treatments that prevent brain damage (e.g., from hypertension, stroke, atherosclerosis, arterial clotting, and nutritional deficiencies).

What Can Neuroscientists and Pharmacologists Offer to Preserve Brain Function?

Neuroscientists, pharmacologists and clinical pharmacologists have contributed by, for example, employing their knowledge of the pathophysiology of stroke and its causes to diminish risk factors. They have developed well known preventive therapies for the control of hypertension and diabetes. Even arterial clots that lead to downstream tissue necrosis (e.g., stroke) can be prevented in some cases with statins and aspirin (Spector 2016). These therapies have reduced stroke in America from the second leading cause of death several decades ago to the fifth leading cause now (Benjamin et al., 2018). Put simply, the preventive approach focusing on well known risk factors with effective, safe, and inexpensive generic drugs is a medical triumph. At present, a substantial part of the continuing incidence of stroke is due to medication non-compliance and lack of access of many patients who would benefit from preventive therapy. To improve medication compliance and access, pharmacologists need to work with additional health professionals. For instance, as in other areas of therapy, long acting anti-hypertensive drugs would almost certainly improve compliance and outcomes. Consider denosumab for the prevention of osteoporosis and fractures; this drug requires only one subcutaneous shot every six months. In fact, a highly durable RNAi inhibitor of PCSK9 for lowering serum cholesterol which potentially requires one subcutaneous injection every six months is being developed (Fitzgerald et al., 2017).

Of course, there are many brain diseases (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, manic depression), where the cause is not known and thus a good pharmacological target is not apparent. However, it is unlikely that transplantation or neurogenesis stimulation is the answer. Instead, the cause must be found and preventive therapy would be best, as in AIDS or the vitamin deficiency syndromes (e.g., pellagra and Wernicke’s; niacin and thiamine deficiency, respectively).

Conclusion

There is little convincing evidence to support the existence of functional AN in the human brain. There is a dramatic decrease in brain AN from salamanders (huge) to rodents (substantial) through monkeys (much less) to minimal or none in humans (Fig 1). The notion that certain brain disorders are due to lack of human AN (e.g., depression, manic-depressive psychosis) is unlikely. The failure of stem cell transplantation in Parkinson’s disease suggests that even if new neurons were somehow introduced in adult human brain, they would have difficulty properly integrating into and functioning in extant brain circuitry. Since there are disorders (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease) in which particular neuronal populations are steadily lost, the challenge is to find methods to preserve them. Adult neuronal networks are composed of neurons that are born sequentially during development and slowly mature according to genetic and environmental cues. Once established, those circuits, although plastic to some extent, cannot be dramatically altered. Hence, we suggest that more emphasis should be placed on the retention and preservation of the health of existing neurons, instead of the introduction of new ones.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Michiko Spector for her valuable contribution in the preparation of this manuscript. This work has been made in part possible by the MacBrainResource NIMH R01-MH113257 to AD.

Funding:

NIMH R01-MH113257 to AD.

Abbreviations:

- AN

adult neurogenesis

- BBB

blood brain barrier

- B-CSF

Blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier

- BrdU

bromodeoxyuridine

- CP

choroid plexus

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- DG

dentate gyrus

- NSC

neural stem cell

- SNc

substantia nigra pars compacta

- SGZ

subgranular zone

- VZ-SVZ

ventricular zone – subventricular zone

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethic Statement

The author declares that the manuscript is in complete compliance with the ethical standards of Brain Structure and Function.

Ethical approval and inform consent

This is a review article and no procedures of any kind were performed on any animals or humans by the authors themselves. This review article is in accordance with general ethical standards of scientific conduct and scientific writing.

References

- 1.Akers KG, Martinez-Canabal A, Restivo L, Yiu AP, De Cristofaro A, Hsiang HL, Wheeler AL, Guskjolen A, Niibori Y, Shoji H, Ohira K, Richards BA, Miyakawa T, Josselyn SA, Frankland PW (2014) Hippocampal neurogenesis regulates forgetting during adulthood and infancy. Science 344:598–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreae LC (2018) Adult neurogenesis in humans: dogma overturned, again and again? Sci. Trans. Med 10:eaat3893. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arellano JI, Harding B, Thomas JL (2018) Adult Human Hippocampus: No New Neurons in Sight. Cereb Cortex 28:2479–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arvidsson A, Collin T, Kirik D, Kokaia Z, Lindvall O (2002) Neuronal replacement from endogenous precursors in the adult brain after stroke. Nat Med 8:963–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakay RA (2005) Neural transplantation. J Neurosurg 103:6–8; discussion 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bannigan J, Langman J (1979) The cellular effect of 5-bromodeoxyuridine on the mammalian embryo. Journal of embryology and experimental morphology 50:123–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben Abdallah NM, Slomianka L, Vyssotski AL, Lipp HP (2010) Early age-related changes in adult hippocampal neurogenesis in C57 mice. Neurobiol Aging 31:151–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benjamin EJ et al. (2018) Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 137:e67–e492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benraiss A, Chmielnicki E, Lerner K, Roh D, Goldman SA (2001) Adenoviral brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces both neostriatal and olfactory neuronal recruitment from endogenous progenitor cells in the adult forebrain. J Neurosci 21:6718–6731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergmann O, Liebl J, Bernard S, Alkass K, Yeung MS, Steier P, Kutschera W, Johnson L, Landen M, Druid H, Spalding KL, Frisen J (2012) The age of olfactory bulb neurons in humans. Neuron 74:634–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhardwaj RD, Curtis MA, Spalding KL, Buchholz BA, Fink D, Bjork-Eriksson T, Nordborg C, Gage FH, Druid H, Eriksson PS, Frisen J (2006) Neocortical neurogenesis in humans is restricted to development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:12564–12568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biggers WJ, Barnea ER, Sanyal MK (1987) Anomalous neural differentiation induced by 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine during organogenesis in the rat. Teratology 35:63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boldrini M, Santiago AN, Hen R, Dwork AJ, Rosoklija GB, Tamir H, Arango V, John Mann J (2013) Hippocampal granule neuron number and dentate gyrus volume in antidepressant-treated and untreated major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 38:1068–1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boldrini M, Fulmore CA, Tartt AN, Simeon LR, Pavlova I, Poposka V, Rosoklija GB, Stankov A, Arango V, Dwork AJ, Hen R, Mann JJ (2018) Human Hippocampal Neurogenesis Persists throughout Aging. Cell Stem Cell 22:589–599 e585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breunig JJ, Arellano JI, Macklis JD, Rakic P (2007) Everything that glitters isn’t gold: a critical review of postnatal neural precursor analyses. Cell Stem Cell 1:612–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charvet CJ, Finlay BL (2018) Comparing Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis Across Species: Translating Time to Predict the Tempo in Humans. Front Neurosci 12:706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Y, Sun FY (2007) Age-related decrease of striatal neurogenesis is associated with apoptosis of neural precursors and newborn neurons in rat brain after ischemia. Brain Res 1166:9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X, Wang K (2016) The fate of medications evaluated for ischemic stroke pharmacotherapy over the period 1995–2015. Acta Pharm Sin B 6:522–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen G, Rajkowska G, Du F, Seraji-Bozorgzad N, Manji HK (2000) Enhancement of hippocampal neurogenesis by lithium. J Neurochem 75:1729–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cipriani S, Ferrer I, Aronica E, Kovacs GG, Verney C, Nardelli J, Khung S, Delezoide AL, Milenkovic I, Rasika S, Manivet P, Benifla JL, Deriot N, Gressens P, Adle-Biassette H (2018) Hippocampal Radial Glial Subtypes and Their Neurogenic Potential in Human Fetuses and Healthy and Alzheimer’s Disease Adults. Cereb Cortex 28:2458–2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cope EC, Gould E (2019) Adult Neurogenesis, Glia, and the Extracellular Matrix. Cell Stem Cell 24:690–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dennis CV, Suh LS, Rodriguez ML, Kril JJ, Sutherland GT (2016) Human adult neurogenesis across the ages: An immunohistochemical study. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 42:621–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doorn KJ, Drukarch B, van Dam AM, Lucassen PJ (2014) Hippocampal proliferation is increased in presymptomatic Parkinson’s disease and due to microglia. Neural Plast 2014:959154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duque A, Rakic P (2011) Different effects of bromodeoxyuridine and [3H]thymidine incorporation into DNA on cell proliferation, position, and fate. J Neurosci 31:15205–15217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duque A, Rakic P (2015) Identification of proliferating and migrating cells by BrdU and other thymidine analogues Benefits and limitations In: Immunocytochemistry and Related Techniques. (Merighi A, Lossi L, eds), pp 123–129: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckenhoff MF, Rakic P (1988) Nature and fate of proliferative cells in the hippocampal dentate gyrus during the life span of the rhesus monkey. J Neurosci 8:2729–2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Bjork-Eriksson T, Alborn AM, Nordborg C, Peterson DA, Gage FH (1998) Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med 4:1313–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ernst A, Alkass K, Bernard S, Salehpour M, Perl S, Tisdale J, Possnert G, Druid H, Frisen J (2014) Neurogenesis in the striatum of the adult human brain. Cell 156:1072–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fitzgerald K, White S, Borodovsky A, Bettencourt BR, Strahs A, Clausen V, Wijngaard P, Horton JD, Taubel J, Brooks A, Fernando C, Kauffman RS, Kallend D, Vaishnaw A, Simon A (2017) A Highly Durable RNAi Therapeutic Inhibitor of PCSK9. N Engl J Med 376:41–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foland LC, Altshuler LL, Sugar CA, Lee AD, Leow AD, Townsend J, Narr KL, Asuncion DM, Toga AW, Thompson PM (2008) Increased volume of the amygdala and hippocampus in bipolar patients treated with lithium. Neuroreport 19:221–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Freed CR, Greene PE, Breeze RE, Tsai WY, DuMouchel W, Kao R, Dillon S, Winfield H, Culver S, Trojanowski JQ, Eidelberg D, Fahn S (2001) Transplantation of embryonic dopamine neurons for severe Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med 344:710–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gage FH (2019) Adult neurogenesis in mammals. Science 364:827–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.George PM, Steinberg GK (2015) Novel Stroke Therapeutics: Unraveling Stroke Pathophysiology and Its Impact on Clinical Treatments. Neuron 87:297–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gomez-Climent MA, Castillo-Gomez E, Varea E, Guirado R, Blasco-Ibanez JM, Crespo C, Martinez-Guijarro FJ, Nacher J (2008) A population of prenatally generated cells in the rat paleocortex maintains an immature neuronal phenotype into adulthood. Cereb Cortex 18:2229–2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gould E (2007) How widespread is adult neurogenesis in mammals? Nat Rev Neurosci 8:481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gould E, Reeves AJ, Graziano MS, Gross CG (1999) Neurogenesis in the neocortex of adult primates. Science 286:548–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gould E, Vail N, Wagers M, Gross CG (2001) Adult-generated hippocampal and neocortical neurons in macaques have a transient existence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:10910–10917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Groves JO, Leslie I, Huang GJ, McHugh SB, Taylor A, Mott R, Munafo M, Bannerman DM, Flint J (2013) Ablating adult neurogenesis in the rat has no effect on spatial processing: evidence from a novel pharmacogenetic model. PLoS Genet 9:e1003718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gusel’nikova VV, Korzhevskiy DE (2015) NeuN As a Neuronal Nuclear Antigen and Neuron Differentiation Marker. Acta Naturae 7:42–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gutierrez-Fernandez M, Fuentes B, Rodriguez-Frutos B, Ramos-Cejudo J, Vallejo-Cremades MT, Diez-Tejedor E (2012) Trophic factors and cell therapy to stimulate brain repair after ischaemic stroke. J Cell Mol Med 16:2280–2290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hauser T, Klaus F, Lipp HP, Amrein I (2009) No effect of running and laboratory housing on adult hippocampal neurogenesis in wild caught long-tailed wood mouse. BMC Neurosci 10:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hsu TC, Somers CE (1961) Effect of 5-bromodeoxyuridine on mamalian chromosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 47:396–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jakubs K, Nanobashvili A, Bonde S, Ekdahl CT, Kokaia Z, Kokaia M, Lindvall O (2006) Environment matters: synaptic properties of neurons born in the epileptic adult brain develop to reduce excitability. Neuron 52:1047–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jang E, Kim JH, Lee S, Kim JH, Seo JW, Jin M, Lee MG, Jang IS, Lee WH, Suk K (2013) Phenotypic polarization of activated astrocytes: the critical role of lipocalin-2 in the classical inflammatory activation of astrocytes. J Immunol 191:5204–5219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jin K, Wang X, Xie L, Mao XO, Zhu W, Wang Y, Shen J, Mao Y, Banwait S, Greenberg DA (2006) Evidence for stroke-induced neurogenesis in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:13198–13202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kempermann G (2006) They are not too excited: the possible role of adult-born neurons in epilepsy. Neuron 52:935–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kempermann G, Gage FH, Aigner L, Song H, Curtis MA, Thuret S, Kuhn HG, Jessberger S, Frankland PW, Cameron HA, Gould E, Hen R, Abrous DN, Toni N, Schinder AF, Zhao X, Lucassen PJ, Frisen J (2018) Human Adult Neurogenesis: Evidence and Remaining Questions. Cell Stem Cell 23:25–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kernie SG, Parent JM (2010) Forebrain neurogenesis after focal Ischemic and traumatic brain injury. Neurobiol Dis 37:267–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kikuchi T, Morizane A, Doi D, Magotani H, Onoe H, Hayashi T, Mizuma H, Takara S, Takahashi R, Inoue H, Morita S, Yamamoto M, Okita K, Nakagawa M, Parmar M, Takahashi J (2017) Human iPS cell-derived dopaminergic neurons function in a primate Parkinson’s disease model. Nature 548:592–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klempin F, Kronenberg G, Cheung G, Kettenmann H, Kempermann G (2011) Properties of doublecortin-(DCX)-expressing cells in the piriform cortex compared to the neurogenic dentate gyrus of adult mice. PLoS One 6:e25760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Knoth R, Singec I, Ditter M, Pantazis G, Capetian P, Meyer RP, Horvat V, Volk B, Kempermann G (2010) Murine features of neurogenesis in the human hippocampus across the lifespan from 0 to 100 years. PLoS One 5:e8809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kohler SJ, Williams NI, Stanton GB, Cameron JL, Greenough WT (2011) Maturation time of new granule cells in the dentate gyrus of adult macaque monkeys exceeds six months. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:10326–10331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koketsu D, Mikami A, Miyamoto Y, Hisatsune T (2003) Nonrenewal of neurons in the cerebral neocortex of adult macaque monkeys. J Neurosci 23:937–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kolb B, Pedersen B, Ballermann M, Gibb R, Whishaw IQ (1999) Embryonic and postnatal injections of bromodeoxyuridine produce age-dependent morphological and behavioral abnormalities. J Neurosci 19:2337–2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kondziolka D, Steinberg GK, Wechsler L, Meltzer CC, Elder E, Gebel J, Decesare S, Jovin T, Zafonte R, Lebowitz J, Flickinger JC, Tong D, Marks MP, Jamieson C, Luu D, Bell-Stephens T, Teraoka J (2005) Neurotransplantation for patients with subcortical motor stroke: a phase 2 randomized trial. J Neurosurg 103:38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kornack DR, Rakic P (1999) Continuation of neurogenesis in the hippocampus of the adult macaque monkey. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:5768–5773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kornack DR, Rakic P (2001) Cell proliferation without neurogenesis in adult primate neocortex. Science 294:2127–2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kuan CY, Schloemer AJ, Lu A, Burns KA, Weng WL, Williams MT, Strauss KI, Vorhees CV, Flavell RA, Davis RJ, Sharp FR, Rakic P (2004) Hypoxia-ischemia induces DNA synthesis without cell proliferation in dying neurons in adult rodent brain. J Neurosci 24:10763–10772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kuhn HG, Toda T, Gage FH (2018) Adult hippocampal neurogenesis: a coming-of-age story. J Neurosci. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee H, Thuret S (2018) Adult Human Hippocampal Neurogenesis: Controversy and Evidence. Trends Mol Med 24:521–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lehner B, Sandner B, Marschallinger J, Lehner C, Furtner T, Couillard-Despres S, Rivera FJ, Brockhoff G, Bauer HC, Weidner N, Aigner L (2011) The dark side of BrdU in neural stem cell biology: detrimental effects on cell cycle, differentiation and survival. Cell Tissue Res 345:313–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Levkoff LH, Marshall GP 2nd, Ross HH, Caldeira M, Reynolds BA, Cakiroglu M, Mariani CL, Streit WJ, Laywell ED (2008) Bromodeoxyuridine inhibits cancer cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Neoplasia 10:804–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liddelow SA et al. (2017) Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature 541:481–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lindvall O, Kokaia Z (2015) Neurogenesis following Stroke Affecting the Adult Brain. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lipp HP, Bonfanti L (2016) Adult Neurogenesis in Mammals: Variations and Confusions. Brain Behav Evol 87:205–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lu Z, Elliott MR, Chen Y, Walsh JT, Klibanov AL, Ravichandran KS, Kipnis J (2011) Phagocytic activity of neuronal progenitors regulates adult neurogenesis. Nat Cell Biol 13:1076–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Luzzati F, Bonfanti L, Fasolo A, Peretto P (2009) DCX and PSA-NCAM expression identifies a population of neurons preferentially distributed in associative areas of different pallial derivatives and vertebrate species. Cereb Cortex 19:1028–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mathews KJ, Allen KM, Boerrigter D, Ball H, Shannon Weickert C, Double KL (2017) Evidence for reduced neurogenesis in the aging human hippocampus despite stable stem cell markers. Aging Cell 16:1195–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mongiat LA, Schinder AF (2014) Neuroscience. A price to pay for adult neurogenesis. Science 344:594–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moreno-Jimenez EP, Flor-Garcia M, Terreros-Roncal J, Rabano A, Cafini F, Pallas-Bazarra N, Avila J, Llorens-Martin M (2019) Adult hippocampal neurogenesis is abundant in neurologically healthy subjects and drops sharply in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med 25:554–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morris SM (1991) The genetic toxicology of 5-bromodeoxyuridine in mammalian cells. Mutat Res 258:161–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Olanow CW, Goetz CG, Kordower JH, Stoessl AJ, Sossi V, Brin MF, Shannon KM, Nauert GM, Perl DP, Godbold J, Freeman TB (2003) A double-blind controlled trial of bilateral fetal nigral transplantation in Parkinson’s disease. Ann Neurol 54:403–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paredes MF, Sorrells SF, Cebrian-Silla A, Sandoval K, Qi D, Kelley KW, James D, Mayer S, Chang J, Auguste KI, Chang EF, Gutierrez Martin AJ, Kriegstein AR, Mathern GW, Oldham MC, Huang EJ, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Yang Z, Alvarez-Buylla A (2018) Does Adult Neurogenesis Persist in the Human Hippocampus? Cell Stem Cell 23:780–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Paredes MF, Sorrells SF, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A (2016) Brain size and limits to adult neurogenesis. J Comp Neurol 524:646–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Parent JM, Lowenstein DH (2002) Seizure-induced neurogenesis: are more new neurons good for an adult brain? Prog Brain Res 135:121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Parent JM, Vexler ZS, Gong C, Derugin N, Ferriero DM (2002) Rat forebrain neurogenesis and striatal neuron replacement after focal stroke. Ann Neurol 52:802–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Parolisi R, Cozzi B, Bonfanti L (2018) Humans and Dolphins: Decline and Fall of Adult Neurogenesis. Front Neurosci 12:497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pencea V, Bingaman KD, Wiegand SJ, Luskin MB (2001) Infusion of brain-derived neurotrophic factor into the lateral ventricle of the adult rat leads to new neurons in the parenchyma of the striatum, septum, thalamus, and hypothalamus. J Neurosci 21:6706–6717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rakic P (1985) Limits of neurogenesis in primates. Science 227:1054–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rakic P (2002a) Neurogenesis in adult primates. Prog Brain Res 138:3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rakic P (2002b) Adult neurogenesis in mammals: an identity crisis. J Neurosci 22:614–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rakic P (2002c) Neurogenesis in adult primate neocortex: an evaluation of the evidence. Nat Rev Neurosci 3:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ross HH, Levkoff LH, Marshall GP 2nd, Caldeira M, Steindler DA, Reynolds BA, Laywell ED (2008) Bromodeoxyuridine induces senescence in neural stem and progenitor cells. Stem Cells 26:3218–3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Saffhill R, Ockey CH (1985) Strand breaks arising from the repair of the 5-bromodeoxyuridine-substituted template and methyl methanesulphonate-induced lesions can explain the formation of sister chromatid exchanges. Chromosoma 92:218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sanai N, Tramontin AD, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Barbaro NM, Gupta N, Kunwar S, Lawton MT, McDermott MW, Parsa AT, Manuel-Garcia Verdugo J, Berger MS, Alvarez-Buylla A (2004) Unique astrocyte ribbon in adult human brain contains neural stem cells but lacks chain migration. Nature 427:740–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]