Abstract

Paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 1 (PITX1) is a pivotal gene in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, which is a well-known pathway affecting lactation performance. The aim of this study was to analyze the DNA methylation profile of the PITX1 gene and its relevance to milk performance in Xinong Saanen dairy goats; thus, potential epigenetic markers of lactation performance were identified. A total of 267 goat blood samples were divided into “low” and “high” groups according to two milk traits: the average milk yield (AMY) and the average milk density (AMD). One CpG island in the 3-flanking region of the PITX1 gene was identified as being related to milk performance. Fisher's exact test demonstrated that the methylation rates of the overall CpG island and the 3rd and 12th CpG-dinucleotide loci in the blood were significantly associated with the AMY, and the overall methylation rate of the high AMY group was relative hypomethylation compared with the low AMY group. The overall methylation rates of this CpG island in mammary gland tissue from dry and lactation periods again exhibited a significant difference: the lactation period showed relative hypomethylation compared with the dry period. Bioinformatic transcription factor binding site prediction identified some lactation performance related transcription factors in this CpG island, such as CTCF, STAT, SMAD, CDEF, SP1, and KLFS. Briefly, overall methylation changes of the CpG island in the PITX1 gene are relevant to lactation performance, which will be valuable for future studies and epigenetic marker-assisted selection (eMAS) in the breeding of goats with respect to lactation performance.

1. Introduction

Lactation performance is a complex quantitative trait affected by several crucial factors including genetic background, nutrition, and environment (Carcangiu et al., 2018). Over the past decade, the influences of genetic variations on milk performance in animals have been extensively studied (Koufariotis et al., 2018). Recently an increasing number of studies have demonstrated that nutritional or environmental changes contribute to changes in inheritable epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation (Lan et al., 2013a; Chavatte-Palmer et al., 2018; Kwan et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 2018). As one of the most important and common types of epigenetic modification, DNA methylation plays a significant role in regulating biological processes such as milk production and organ development (Hwang et al., 2017; Fleming et al., 2018; Jessop et al., 2018). In recent years, gene methylation involved in vital biological functions has been well-studied in animals (Ibeagha-Awemu and Zhao, 2015). However, to date, no association has been established between epigenetic modifications and lactation performance.

It is well-known that lactation performance is regulated by several critical pathways, such as the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis pathway (PITX2/PITX1–HESX1–LHX3/LHX4–PROP1–POU1F1), which regulates the expression of GH (growth hormone) and PRL (prolactin) (Davis et al., 2010). As a member of the paired-like homeodomain transcription factor (PITX) family, the PITX1 gene is located upstream of the HPA axis pathway and plays a critical role in pituitary organogenesis (Ma et al., 2017). During early pituitary development, PITX1 activates the transcription of couples of pituitary hormone genes and transcription factor genes such as the LIM family, the POU family, and the SIX family (Poulin et al., 2000). Notably, PITX1 has been characterized as an activator of the POMC gene and a partner of Pit1 causing differential expression of GH, PRL, and TSH, and thereby affecting milk performance in animals (Carvalho et al., 2006). In 2013, both the PITX1 gene and another PITX family member, PITX2, were identified as being associated with milk performance in dairy goats (Lan et al., 2013b; Zhao et al., 2013).

Therefore, this study aimed at exploring the DNA methylation changes at the CpG islands within PITX1 gene, as well as their relevance to milk performance. The present study is important and necessary for exploring the epigenetic regulation of lactation and developing potential epigenetic markers for improving milk performance through epigenetic marker-assisted selection (eMAS) in breeding.

2. Materials and methods

Experimental animals and the procedures performed in this study were approved by the Faculty Animal Policy and Welfare Committee of Northwest A & F University under contract (NWAFU-314020038). The care and use of experimental animals fully complied with local animal welfare laws, guidelines, and policies.

2.1. Animals, phenotypic data recording, and group classification

A total of 267 blood samples were obtained from healthy, unrelated adult female Xinong Saanen dairy goats, which were reared on the Chinese native dairy goat breeding farm in Qianyang County, Shaanxi, China (Zhao et al., 2013). The data regarding the average milk yield (AMY; kg) were obtained directly from the breeding farm, whereas the data regarding the average milk density (AMD) were measured by our study team using a MilkoScan FT120 (FOSS Corporation, Denmark) instrument (Lan et al., 2013b; Zhao et al., 2013). The relevant measurements of these two milk traits are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Milk performance of the low and high groups of Xinong Saanen dairy goats.

| Items | Average milk yield (kg) | Average milk density |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum values | 272.4 | 1023 |

| Maximum values | 1057.6 | 1036.5 |

| Data range | 758.2 | 13.5 |

| Mean | 728.5 | 1029.2 |

| SD | 130.6 | 2.1 |

| Kurtosis | 0.021 | 1.397 |

| Skewness | 0.005 | |

| Mean of low group | 321.1 | 1023.8 |

| SD of low group | 68.8 | 1.1 |

| Mean of high group | 1024.8 | 1035.5 |

| SD of high group | 46.5 | 1.4 |

| values |

The use of different letters (A, B) beside mean values in the same column signifies a significant difference at the level; SD stands for standard deviation.

Using the statistical probability (95.00 %) of the mean standard deviations for AMY and AMD, the low and high groups for each of the aforementioned milk traits were classified according to published literature (Pan et al., 2013). For the low or high group of each milk trait, two random pooled samples were constructed, and were named as follows: L-P1 (low-pool I), L-P2 (low-pool II), H-P1 (high-pool I), and H-P2 (high-pool II). Finally, eight DNA pools were constructed. It can be noted from Table 1 that the low group for each milk trait was significantly lower than average, whereas the high group was significantly higher than average. A test was used to confirm the significance of the difference between the low and high groups, and the results validated that there were indeed significant differences between low and high groups for the AMY (kg) and the AMD (; Table 1). In addition, five mammary gland tissue samples from Xinong Saanen dairy goats during a lactation period () and a dry period () were collected from another Xinong Saanen dairy goat farm, Fuping, Shaanxi Province, China (X. Zhang et al., 2017).

2.2. Genomic DNA extraction and bisulfite treatment

Genomic DNA samples from all chosen individuals were isolated as previously described (Cui et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018). The DNA samples were then measured and diluted to a final concentration of 50 ng L (Wang et al., 2017; Q. Yang et al., 2017, 2018). Qualified DNA samples from the low and high groups were equally selected to construct genomic DNA pools. Each pool – containing 1000 ng mixed genomic DNA – was processed by sodium bisulfite using a QIAGEN EpiTect Fast DNA Bisulfite Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) and following the manufacture's instructions.

2.3. Bioinformatics analyses

The CpG islands within the goat PITX1 gene were predicted using the MethPrimer website (http://www.urogene.org/methprimer/, last access: 10 January 2019) (Li and Dahiya, 2002), and the primers used to amplify the CpG islands were also designed using this website (Table 2).

Table 2.

Primers used for PCR amplification.

| Primers | Primer sequences (5–3) | Length (bp) | CpG numbers | Location (GeneID: 508754) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | F: GTTTAGATAGGAGTTGATTTTTGAG | 126 | 8 | 5-flanking region |

| |

R: ATAACACACTAAATTCTCCCTC |

|

|

|

| P2 | F: GGGTGGTATTAATATAGGGTTTTAG | 132 | 6 | Intron 1 |

| |

R: CAATAATCACCTTCTAATCAAACTC |

|

|

|

| P3 | F: ATTAGTAGTTGGATTTGTGTAAGGG | 106 | 10 | Exon 3 |

| |

R: ACCCAATTATTATAAAAATACCCC |

|

|

|

| P4 | F: GTTATATGTTTTTGGGTGGGAT | 403 | 24 | 3-flanking region |

| R: CTATTCAACCCAACTCCCTTAA |

To identify the possible trans-acting factors which might bind to specific CpG-dinucleotide locus, two respective authorized and reliable online bioinformatics softwares were used: TFSEARCH (Version 1.3) (http://mbs.cbrc.jp/research/db/TFSEARCH.html, last access: 19 June 2018) and the MatInspector database in Genomatix (http://www.genomatix.de, last access: 10 January 2019).

2.4. PCR amplification, cloning, and sequencing of the CpG island within the PITX1 gene

The PCR reaction and the purification of the PCR products were performed as previously described (Pan et al., 2013). Purified fragments were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega, WI, USA) system. The colony PCR was used to identify the positive inserts, which were sequenced via sequencing service (GenScript, Nanjing, China). The number of positive inserts for each pool sent for sequencing was around 10, according to the efficiency of ligation and transformation. The methylation status for the CpG island and each CpG-dinucleotide locus was measured by sequencing, and alignment analyses were carried out using DNAMAN software (version 7.0, Lynnon Biosoft, Vaudreuil, Quebec, Canada) (Lan et al., 2013a).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Comparisons of the methylation difference at each CpG-dinucleotide locus, the entire CpG island between the low and high groups for each milk trait, and the methylation status of mammary gland tissue from dry and lactation periods were analyzed using the Fisher's exact test (-test) as previously described (Lan et al., 2013a).

3. Results

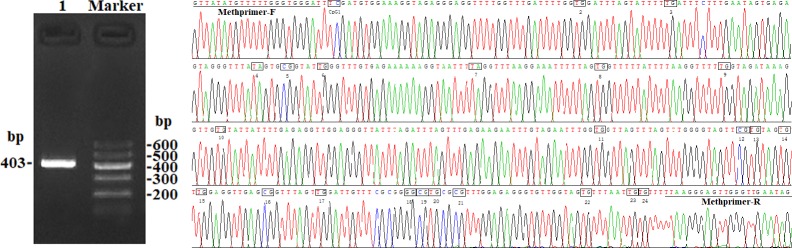

3.1. DNA methylation profile of the PITX1 gene

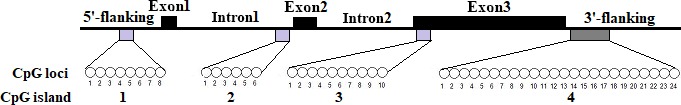

In this study, four CpG islands located at the 5-flanking region, intron 1, exon 3, and 3-flanking region of the PITX1 gene were predicted (Fig. 1). A total of four pairs of methylation primers were designed to amplify these four CpG islands. Due to the complexity and low G and C bases content of bisulfite-processed genomic DNA as well as the low amplification efficiency for bisulfite PCR, only one 403 bp-CpG island (24 CpG-dinucleotide loci) located at the 3-flanking region was accessible using the P4 primer (Fig. 2). At the available CpG island within the PITX1 gene, about 10 positive inserts for each sample were sequenced. The alignments of the sequences demonstrated different overall methylation patterns in the low and high pools for the two milk traits; the overall methylation rate of these blood DNA pools varied from 22.46 % (high pool group for AMY) to 33.33 % (high pool group for the AMD) (Table 3). In addition, different overall methylation patterns were detected in mammary gland tissue from dry (57.29 %) and lactation (45.03 %) periods (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Gene structure and CpG islands distribution within the goat PITX1 gene.

Figure 2.

PCR electrophoresis diagram and bisulfite sequencing maps of the goat PITX1 CpG island.

Table 3.

Methylation percentage and value difference of each CpG-dinucleotide locus between the low and high groups.

| Milk traits | Average milk yield |

Average milk density |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CpG no. | Low group | High group | value | Low group | High group | value |

| CpG1 | 43.75 % | 17.39 % | 0.146 | 22.22 % | 38.10 % | 0.338 |

| CpG2 | 56.25 % | 34.78 % | 0.209 | 66.67 % | 52.38 % | 0.380 |

| CpG3 | 50.00 % | 17.39 % | 0.041 | 18.52 % | 28.57 % | 0.498 |

| CpG4 | 18.75 % | 8.70 % | 0.631 | 0.00 % | 0.00 % | 1.000 |

| CpG5 | 75.00 % | 43.48 % | 0.099 | 55.56 % | 66.67 % | 0.555 |

| CpG6 | 0.00 % | 0.00 % | 1.000 | 0.00 % | 0.00 % | 1.000 |

| CpG7 | 6.25 % | 0.00 % | 0.410 | 3.70 % | 4.76 % | 1.000 |

| CpG8 | 6.25 % | 8.70 % | 1.000 | 25.93 % | 28.57 % | 1.000 |

| CpG9 | 25.00 % | 4.35 % | 0.139 | 18.52 % | 23.81 % | 0.729 |

| CpG10 | 43.75 % | 30.43 % | 0.503 | 44.44 % | 42.86 % | 1.000 |

| CpG11 | 25.00 % | 47.83 % | 0.192 | 29.63 % | 38.10 % | 0.555 |

| CpG12 | 0.00 % | 47.83 % | 0.001 | 37.04 % | 19.05 % | 0.214 |

| CpG13 | 25.00 % | 17.39 % | 0.694 | 37.04 % | 38.10 % | 1.000 |

| CpG14 | 25.00 % | 30.43 % | 1.000 | 0.00 % | 4.76 % | 0.438 |

| CpG15 | 18.75 % | 47.83 % | 0.093 | 44.44 % | 33.33 % | 0.555 |

| CpG16 | 43.75 % | 17.39 % | 0.146 | 44.44 % | 42.86 % | 1.000 |

| CpG17 | 18.75 % | 13.04 % | 0.674 | 37.04 % | 52.38 % | 0.382 |

| CpG18 | 12.50 % | 13.04 % | 1.000 | 22.22 % | 23.81 % | 1.000 |

| CpG19 | 50.00 % | 21.74 % | 0.090 | 48.15 % | 52.38 % | 1.000 |

| CpG20 | 37.50 % | 17.39 % | 0.264 | 59.26 % | 42.86 % | 0.383 |

| CpG21 | 43.75 % | 34.78 % | 0.740 | 51.85 % | 38.10 % | 0.393 |

| CpG22 | 43.75 % | 21.74 % | 0.174 | 44.44 % | 57.14 % | 0.561 |

| CpG23 | 25.00 % | 13.04 % | 0.415 | 44.44 % | 33.33 % | 0.555 |

| CpG24 |

6.25 % |

30.43 % |

0.109 |

29.63 % |

38.10 % |

0.555 |

| Total | 29.17 % | 22.46 % | 0.022 | 32.72 % | 33.33 % | 0.850 |

Table 4.

Methylation percentage and value difference for each CpG-dinucleotide locus between the mammary gland tissue from the dry and lactation periods.

| Periods/CpG no. | Lactation | Dry | value | Periods/CpG no. | Lactation | Dry | value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CpG1 | 42.31 % | 50.00 % | 0.766 | CpG13 | 38.46 % | 55.00 % | 0.372 |

| CpG2 | 57.69 % | 65.00 % | 0.763 | CpG14 | 30.77 % | 55.00 % | 0.135 |

| CpG3 | 38.46 % | 65.00 % | 0.001 | CpG15 | 42.31 % | 55.00 % | 0.552 |

| CpG4 | 42.31 % | 50.00 % | 0.008 | CpG16 | 34.62 % | 60.00 % | 0.136 |

| CpG5 | 57.69 % | 60.00 % | 1.000 | CpG17 | 38.46 % | 50.00 % | 0.552 |

| CpG6 | 42.31 % | 50.00 % | 0.766 | CpG18 | 19.23 % | 30.00 % | 0.494 |

| CpG7 | 42.31 % | 40.00 % | 1.000 | CpG19 | 42.31 % | 55.00 % | 0.552 |

| CpG8 | 34.62 % | 55.00 % | 0.233 | CpG20 | 57.69 % | 70.00 % | 0.540 |

| CpG9 | 50.00 % | 55.00 % | 0.774 | CpG21 | 53.85 % | 65.00 % | 0.551 |

| CpG10 | 53.85 % | 65.00 % | 0.551 | CpG22 | 46.15 % | 70.00 % | 0.139 |

| CpG11 | 65.38 % | 70.00 % | 1.000 | CpG23 | 46.15 % | 65.00 % | 0.244 |

| CpG12 |

53.85 % |

60.00 % |

0.769 |

CpG24 |

50.00 % |

60.00 % |

0.561 |

| Total | 45.03 % | 57.29 % |

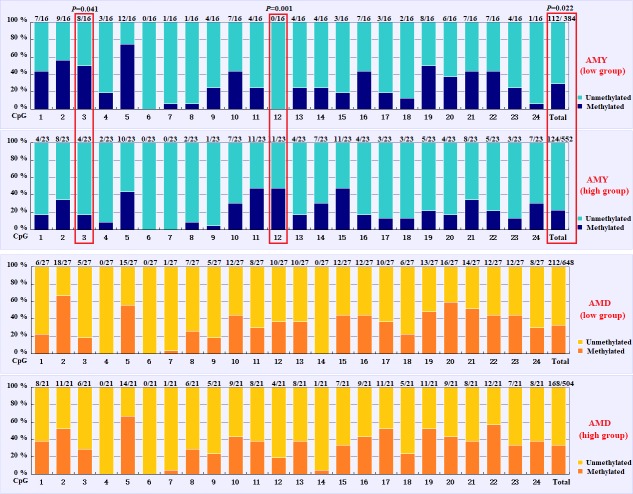

3.2. DNA methylation differences between the low and high groups for the two milk traits

Based on the methylation status of each CpG-dinucleotide locus, methylation differences between the low and high groups were evaluated according to Fisher's exact test (-test). As seen from Table 3 and Fig. 3, the overall methylation level of the CpG island within the PITX1 gene was significantly associated with the AMY (). Specifically, the overall methylated percentage of the high AMY group (22.46 %) was significantly lower than that of the low group (29.17 %). For individual CpG-dinucleotide locus, the methylation status of the 3rd CpG-dinucleotide locus was significantly associated with the AMY (), and the methylation percentage of this locus from high group (17.39 %) was significantly lower than that from low group (50.00 %); on the contrary, the methylation status of the 12th CpG-dinucleotide locus showed a negative association with the AMY, and the methylation rate of the high group (47.83 %) was significantly higher than that of the low group (0 % (Table 3 and Fig. 3). However, no significant relevance was found between methylation changes and the AMD.

Figure 3.

Comparisons of the DNA methylation differences for each CpG locus between the low and high groups for the two lactation traits. The numbers () above each bar represent the ratio of methylation versus total colonies, and the red frames represent significant differences. AMY refers to the average milk yield, and AMD refers to the average milk density.

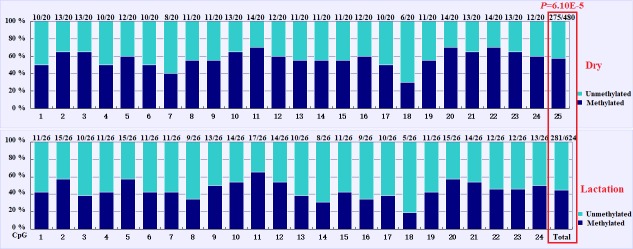

3.3. DNA methylation differences between mammary gland tissue from dry and lactation periods

The overall DNA methylation rates of the CpG island in mammary gland tissue from dry and lactation periods exhibited a significant difference (); mammary gland tissue from the dry period showed hypermethylation (57.29 %), whereas mammary gland tissue from the lactation period showed relative hypomethylation (45.03 %) (Table 4 and Fig. 4). However, no significant relevance was identified on each CpG-dinucleotide locus in mammary gland tissue from the dry and lactation periods.

Figure 4.

Comparisons of the DNA methylation differences for each CpG locus for mammary gland tissue from dry and lactation periods. The numbers () above each bar represent the ratio of methylation versus total colonies, and the red frame represents a significant difference.

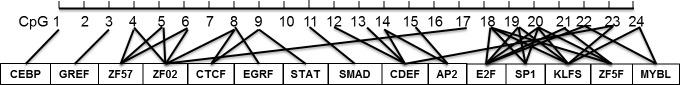

3.4. Possible trans-acting factors binding to the CpG-dinucleotide loci

According to the bioinformatical analyses, several crucial transcription factors, such as CTCF, STAT, SMAD, CDEF, SP1, KLFS, and zinc finger transcription factors were predicted to bind to the CpG-dinucleotide loci of this CpG island within PITX1 (Fig. 5). In this CpG island, 24 CpG-dinucleotide loci were sparsely localized in the 403 bp region, and potential transcription factors were predicted to bind to the nearby area of almost every CpG-dinucleotide loci.

Figure 5.

Prediction of the possible binding transcription factors for each CpG-dinucleotide locus in the CpG island within the goat PITX1 gene.

4. Discussion

Extensive DNA methylation studies have focused on the CpG islands located at the promoter region, as the methylation of promoter CpG islands could result in self-perpetuating gene silencing (Moore et al., 2013). However, an increasing number of studies have found that a far greater proportion of methylation occurs across the whole gene (Jones, 2012). Genome-wide studies have revealed that gene body methylation is evolutionarily conserved (Keller et al., 2016). Therefore, this work attempted to study the methylation of four possible CpG islands across the whole PITX1 gene in a group Xinong Saanen dairy goats. However, only the CpG island located at the 3-flanking region was available. It is well known that 3-flanking regions are also important in gene regulation (Yang et al., 2016).

Recently, numerous epigenetic markers have been identified as being involved in biological functions and livestock traits using whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) and bisulfite sequencing methods (Y. Yang et al., 2017; Sarova et al., 2018). Fang et al. (2017) uncovered 331 meat quality traits related to candidate differentially methylated regions (DMRs) in Japanese Black (Wagyu) and Chinese Red Steppes cattle. Y. Zhang et al. (2017) revealed 10 DMR-related genes (DMGs) by analyzing the sequencing results of Hu sheep ovaries, which were likely related to the prolificacy of Hu sheep. Li et al. (2018) identified potential DMRs and DMGs that were involved in hair follicle development and growth in cashmere goats. Dechow and Liu (2018) detected the DNA methylation patterns in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of Holstein cattle with variable milk yield, and revealed some potential epigenetic variation related to milk performance. With the rapid development of science, more and more crucial genetic and epigenetic markers will be discovered, which will provide abundant information for animal breeding and biological research.

Numerous genes have been proved to be regulated by DNA methylation, and there are a few possible mechanisms by which this can occur (Mattern et al., 2017). The methyl-group in CpG islands might result in compact and inactive chromatin structure, recruiting methyl-CpG binding proteins or preventing relevant transcription factors from binding, which inhibits the initiation or proceeding of transcription (Kang et al., 2015). In this study, we designed three pairs of primers to detect the expression of goat PITX1. However, we failed to detect the expression of goat PITX1 in mammary gland tissue and other tissues (heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney, muscle, and adipose tissue – data not shown). Furthermore, according to the Ensembl, NCBI, and BioGPS databases, there is little expression of PITX1 in the adult mammary glands of humans, mice, and sheep. Even though there was no expression of PITX1 in mammary gland tissue, we speculate that the epigenetic modification of PITX1 can still be an useful epigenetic marker for improving lactation performance in the process of goat epigenetic marker-assisted selection in breeding at the DNA level.

In addition, these findings have also been corroborated by the biological functions of some possible transcription factors predicted in this study, including the following: (1) CTCF can regulate gene expression by binding to the gene imprinting control region (ICR) (Dunn and Davie, 2003); (2) the STAT family of proteins are the main components in the JAK–STAT pathway, which is critical to the proper development and function of the mammary epithelial tissue (Haricharan and Li, 2014); (3) SMAD proteins are Smad signaling components – in mammary epithelial cells, Smad signaling acts to antagonize JAK–STAT signaling to regulate mammary gland differentiation (Cocolakis et al., 2008); (4) CDEF could regulate the cell cycle of epithelial cell (Müller and Engeland, 2010); and (5) SP1 and KLFS could regulate the expression of genes containing GC-rich promoters (Kaczynski et al., 2003), and these transcription factors could influence the function of PITX1 and therefore affect lactation performance.

5. Conclusion

In this study, a functional CpG island at the 3 flanking region of goat PITX1 gene was identified. In this region, the overall methylation rate of the high AMY group showed relative hypomethylation compared with the low AMY yield group; the overall methylation rate of mammary gland tissue from the lactation period showed hypomethylation compared with the dry period. These results will provide epigenetic markers for improving lactation performance with regards to the process of goat epigenetic marker-assisted selection in breeding.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31172184) and the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province of China (grant no. 2017JM3021). Edited by: Steffen Maak Reviewed by: Runjun Yang and one anonymous referee

Appendix A. Abbreviations

| PITX | Paired-like homeodomain transcription factor |

| PITX1 | Paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 1 |

| AR | Androgen receptor |

| eMAS | Epigenetic marker-assisted selection |

| HPA axis | Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| AMY | Average milk yield |

| AMD | Average milk density |

| WGBS | Whole genome bisulfite sequencing |

| DMRs | Differentially methylated regions |

| DMGs | Differentially methylated region-related genes |

Data availability

The original data are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

HZ and SZ contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Carcangiu V, Arfuso F, Luridiana S, Giannetto C, Rizzo M, Bini PP, Piccione G. Relationship between different livestock managements and stress response in dairy ewes. Arch Anim Breed. 2018;61:37–41. doi: 10.5194/aab-61-37-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho L, Ward RD, Brinkmeier ML, Potok MA, Vesper AH, Camper SA. Molecular basis for pituitary dysfunction: comparison of Prop1 and Pit1 mutant mice. Dev Biol. 2006;295:340. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chavatte-Palmer P, Velazquez MA, Jammes H, Duranthon V. Review: Epigenetics, developmental programming and nutrition in herbivores. Animal. 2018;24:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S1751731118001337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocolakis E, Dai M, Drevet L, Ho J, Haines E, Ali S, Lebrun JJ. Smad signaling antagonizes STAT5-mediated gene transcription and mammary epithelial cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1293–1307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707492200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Yan H, Wang K, Xu H, Zhang X, Zhu H, Liu J, Qu L, Lan X, Pan C. Insertion/Deletion within the KDM6A gene is significantly associated with litter size in goat. Frontiers in Genetics. 2018;9:91. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis SW, Castinetti F, Carvalho LR, Ellsworth BS, Potok MA, Lyons RH, Brinkmeier ML, Raetzman LT, Carninci P, Mortensen AH, Hayashizaki Y, Arnhold IJ, Mendonça BB, Brue T, Camper SA. Molecular mechanisms of pituitary organogenesis: In search of novel regulatory genes. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;323:4–19. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechow CD, Liu WS. DNA methylation patterns in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from Holstein cattle with variable milk yield. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:744. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5124-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn KL, Davie JR. The many roles of the transcriptional regulator CTCF. Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;81:161–167. doi: 10.1139/o03-052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, Zhao Z, Yu H, Li G, Jiang P, Yang Y, Yang R, Yu X. Comparative genome-wide methylation analysis of longissimus dorsi muscles between Japanese black (Wagyu) and Chinese Red Steppes cattle. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming A, Abdalla EA, Maltecca C, Baes CF. Invited review: Reproductive and genomic technologies to optimize breeding strategies for genetic progress in dairy cattle. Arch Anim Breed. 2018;61:43–57. doi: 10.5194/aab-61-43-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haricharan S, Li Y. STAT signaling in mammary gland differentiation, cell survival and tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;382:560–569. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JH, An SM, Kwon S, Park DH, Kim TW, Kang DG, Yu GE, Kim IS, Park HC, Ha J, Kim CW. DNA methylation patterns and gene expression associated with litter size in Berkshire pig placenta. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0184539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibeagha-Awemu EM, Zhao X. Epigenetic marks: regulators of livestock phenotypes and conceivable sources of missing variation in livestock improvement programs. Frontiers in Genetics. 2015;6:302. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessop P, Ruzov A, Gering M. Developmental Functions of the Dynamic DNA Methylome and Hydroxymethylome in the Mouse and Zebrafish: Similarities and Differences. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2018;6:27. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2018.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:484–492. doi: 10.1038/nrg3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczynski J, Cook T, Urrutia R. Sp1-and Kruppel-like transcription factors. Genome Biol. 2003;4:206. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-2-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JY, Song SH, Yun J, Jeon MS, Kim HP, Han SW, Kim TY. Disruption of CTCF/cohesin-mediated high-order chromatin structures by DNA methylation downregulates PTGS2 expression. Oncogene. 2015;34:5677–5684. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller TE, Han P, Yi SV. Evolutionary Transition of Promoter and Gene Body DNA Methylation across Invertebrate-Vertebrate Boundary. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1019–1028. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msv345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koufariotis LT, Chen YP, Stothard P, Hayes BJ. Variance explained by whole genome sequence variants in coding and regulatory genome annotations for six dairy traits. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:237. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4617-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan STC, King JH, Grenier JK, Yan J, Jiang X, Roberson MS, Caudill MA. Maternal Choline Supplementation during Normal Murine Pregnancy Alters the Placental Epigenome: Results of an Exploratory Study. Nutrients. 2018;10:E417. doi: 10.3390/nu10040417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan XY, Cretney EC, Kropp J, Khateeb K, Berg MA, Peñagaricano F, Khatib H. Maternal diet during pregnancy induces gene expression and DNA methylation changes in fetal tissues in sheep. Frontiers in Genetics. 2013;4:49. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00049. a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan XY, Zhao HY, Li ZJ, Zhou R, Pan CY, Lei CZ, Chen H. Exploring the Novel Genetic Variant of PITX1 Gene and Its Effect on Milk Performance in Dairy Goats. J Integr Agr. 2013;2:118–126. b. [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Li Y, Zhou G, Gao Y, Ma S, Chen Y, Song J, Wang X. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing of goat skins identifies signatures associated with hair cycling. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:638. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LC, Dahiya R. MethPrimer: designing primers for methylation PCRs. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:1427–143. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.11.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Qin QM, Yang Q, Zhang M, Zhao HY, Pan CY, Lei CZ, Chen H, Lan XY. Associations of six SNPs of POU1F1-PROP1-PITX1-SIX3 pathway genes with growth traits in two Chinese indigenous goat breeds. Ann Anim Sci. 2017;17:399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Mattern F, Heinzmann J, Herrmann D, Lucas-Hahn A, Haaf T, Niemann H. Gene-specific profiling of DNA methylation and mRNA expression in bovine oocytes derived from follicles of different size categories. Reprod Fert Develop. 2017;29:2040–2051. doi: 10.1071/RD16327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore LD, Le T, Fan G. DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:23–38. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller GA, Engeland K. The central role of CDE/CHR promoter elements in the regulation of cell cycle-dependent gene transcription. FEBS J. 2010;277:877–893. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan C, Jia W, Wu X, Zhao H, Liu S, Lei C, Lan X, Chen H. DNA methylation profile of DNA methyltransferase 3b (DNMT3b) gene and its influence on growth traits in goat. J Anim Plant Sci. 2013;23:380–387. [Google Scholar]

- Poulin G, Lebel M, Chamberland M, Paradis FW, Drouin J. Specific protein-protein interaction between basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors and homeoproteins of the Pitx family. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4826–4837. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.13.4826-4837.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarova N, Ahlawat S, Grewal A, Sharma R, Arora R. Differential promoter methylation of DAZL gene in bulls with varying seminal parameters. Reprod Domest Anim. 2018;53:914–920. doi: 10.1111/rda.13187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Yang Q, Wang K, Zhang S, Pan C, Chen H, Qu L, Yan H, Lan X. A novel 12-bp indel polymorphism within the GDF9 gene is significantly associated with litter size and growth traits in goats. Anim Genet. 2017;48:735–736. doi: 10.1111/age.12617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Yang Q, Wang K, Yan H, Pan C, Chen H, Liu J, Zhu H, Qu L, Lan X. Two strongly linked single nucleotide polymorphisms (Q320P and V397I) in GDF9 gene are associated with litter size in cashmere goats. Theriogenology. 2018;125:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2018.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Zhang S, Liu L, Cao X, Lei C, Qi X, Lin F, Qu W, Qi X, Liu J, Wang R, Chen H, Lan X. Application of mathematical expectation (ME) strategy for detecting low frequency mutations: An example for evaluating 14-bp insertion/deletion (indel) within the bovine PRNP gene. Prion. 2016;10:409–419. doi: 10.1080/19336896.2016.1211593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Yan H, Li J, Xu H, Wang K, Zhu H, Chen H, Qu L, Lan X. A novel 14-bp duplicated deletion within goat GHR gene is significantly associated with growth traits and litter size. Anim Genet. 2017;48:499–500. doi: 10.1111/age.12551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Zhang SL, Li J, Wang X, Peng K, Lan X, Pan C. Development of a touch-down multiplex PCR method for simultaneously rapidly detecting three novel insertion/deletions (indels) within one gene: an example for goat GHR gene. Anim Biotechnol. 2018:1–6. doi: 10.1080/10495398.2018.1517770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Liang G, Niu G, Zhang Y, Zhou R, Wang Y, Mu Y, Tang Z, Li K. Comparative analysis of DNA methylome and transcriptome of skeletal muscle in lean-, obese-, and mini-type pigs. Sci Rep-UK. 2017;7:39883. doi: 10.1038/srep39883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan X, Tsujimoto K, Hashimoto K, Kawahori K, Hanzawa N, Hamaguchi M, Seki T, Nawa M, Ehara T, Kitamura Y, Hatada I, Konishi M, Itoh N, Nakagawa Y, Shimano H, Takai-Igarashi T, Kamei Y, Ogawa Y. Epigenetic modulation of Fgf21 in the perinatal mouse liver ameliorates diet-induced obesity in adulthood. Nat Commun. 2018;9:636. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03038-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Wu X, Cai H, Pan C, Lei C, Chen H, Lan X. Genetic variants and effects on milk traits of the caprine paired-like homeodomain transcription factor 2 (PITX2) gene in dairy goats. Gene. 2013;532:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Zhang S, Ma L, Jiang E, Xu H, Chen R, Yang Q, Chen H, Li Z, Lan X. Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) of dairy goat mammary glands reveals DNA methylation profiles of integrated genome-wide and critical milk-related genes. Oncotarget. 2017;8:115326–115344. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Li F, Feng X, Yang H, Zhu A, Pang J, Han L, Zhang T, Yao X, Wang F. Genome-wide analysis of DNA Methylation profiles on sheep ovaries associated with prolificacy using whole-genome Bisulfite sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2017;18:759. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4068-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original data are available upon request to the corresponding author.