Abstract

Objective:

Definitive concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CRT) is considered the standard of care for organ preservation and is the only potentially curative therapy for surgically unresectable patients with stage III to IVb locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. In patients with high risks for adverse events utilizing cisplatin, carboplatin has been empirically substituted. The objective of this study was to estimate the locoregional control rate, progression-free survival, overall survival, and adverse events in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck patients treated with CRT utilizing carboplatin.

Study Design:

A retrospective single-arm analysis.

Methods:

Data on consecutive patients who fit the eligibility criteria were collected. Eligible patients were treated with 70 Gy of radiation therapy and at least two cycles of carboplatin (area of curve [AUC] of 5 between January 2007 to December 2013.

Results:

Fifty-four patients were identified. Overall locoregional control rate was 50% (95% confidence interval [CI] 37%–63%). Median progression-free and overall survival were 21 (CI 11–33) and 40 (CI 33–NA) months, respectively. One-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival were 81% (CI 67%–89%), 59% (CI 41%–73%), and 42% (CI 22%–61%), respectively. Stage III/IVa patients (n = 45) had a median survival of 62 (CI 37–NA months) and 3 years of 71% (CI 53%–84%), whereas stage IVb (n = 9) had a median survival of 31 (CI 4–NA) months and none survived to 3 years.

Conclusion:

Definitive CRT with carboplatin for locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck was well tolerated and demonstrated comparable results to CRT with cisplatin.

Keywords: Chemoradiotherapy, locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, carboplatin, cisplatin, renal insufficiency

INTRODUCTION

Head and neck cancer accounts for more than 550,000 cases annually worldwide.1 In the United States, the 2016 statistics reports estimated 61,760 new cases and 13,190 deaths.2 Approximately 95% of these tumors are squamous cell carcinomas arising primarily from the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx.3

Definitive concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CRT) is considered the standard of care for organ preservation and is the only potentially curative therapy in surgically unresectable patients with stage III to IVb locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (LA-SCCHN). The standard regimen is 70 Gy (2 Gy/fraction) over 7 weeks, with concurrent cisplatin 100 mg/m2 on days 1, 22, and 43. This was established mainly by the Intergroup4 and the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 91–115 trials, utilizing cisplatin-based CRT. In a retrospective study of 233 patients, half of the patients receiving high-dose cisplatin and radiation for treatment of head and neck cancer developed acute kidney injury despite careful patient selection, liberal hydration, and use of mannitol to maintain urinary flow.6 In patients with baseline renal insufficiency or hearing impairment who are considered to have high risks for adverse events (AEs) with cisplatin, carboplatin has been empirically substituted as an alternative regimen. Data are available regarding the outcomes of patients treated with carboplatin-based CRT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Approval for data collection and analysis was obtained from Karmanos Cancer Institute/Wayne State University (Detroit, MI) Institutional Review Board. The study cohort consisted of 54 patients with histology proven LA-SCCHN.

Demographic, clinical, radiographic, and pathologic data were obtained from electronic medical records and included the following: age, gender, performance status, number of prior treatments, number of cycles, and toxicities. Pretreatment imaging studies (i.e., computed tomography [CT] scans and magnetic resonance imagings) were reviewed by an independent institutional radiologist to determine the initial stage.

Concurrent Chemoradiation

Eligible patients were treated with concurrent chemoradiation therapy with 70 Gy of radiation therapy and at least two cycles of carboplatin (area of curve [AUC] of 5 at the Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit, Michigan, between January 2007 and December 2013.

Evaluation of Toxicity

Toxicity was graded using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4. Data on the grade of reported toxicities, with particular interest in the frequency of grade 3 or higher toxic events, were collected. Adverse events documented to have occurred between day 1 of therapy (chemotherapy or radiation therapy, whichever came first, or both if started on the same day) up until 30 days after the last day of therapy (chemotherapy or radiation therapy, whichever came last, or both if ended on the same day) were collected.

Statistical Analysis

The primary objective was to estimate local–regional control (LRC) rate. Secondary objectives were estimation of progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and laryngectomy rates in LC patients, as well as the evaluation of adverse events in all patients included in the study.

Progression-free survival was defined as the time from initiation of carboplatin treatment until disease progression or death, whichever occurred first. Overall survival was defined as time from initiation of carboplatin treatment until death. Patients who have not experienced the event of interest were censored at the date of last contact.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Patients

Between January 2007 and December 2013, 54 patients with LA-SCCHN underwent definitive CRT with carboplatin (AUC of 5). They were mostly older with a median age of 60.5 (range: 38–80). Fourteen patients were older than 65, and five were older than 70 years of age. They were predominantly (78%) male. Half of the patients had LC (50%); next most common was oropharyngeal (35%); a few patients (7%) had unresectable oral cavity or hypopharyngeal (6%); and 2% had SCCHN of unknown primary origin. Nearly half (46%) had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (PS) 0 to 1, whereas the rest (54%) had PS 2 to 3. Prior to initiation of treatment, nearly one-quarter (24%) had chronic kidney disease ≥ stage 3, and one-fifth (20%) had hearing impairment at baseline (Table I).

TABLE I.

Patient Characteristics.

| Age | Median 60.5 (IQR 56–65) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | M | 42 (78%) |

| F | 12 (22%) | |

| Diagnosis | Oral cavity | 4 (7%) |

| Oropharyngeal | 19 (35%) | |

| Hypopharyngeal | 3 (6%) | |

| Laryngeal | 27 (50%) | |

| Unknown primary HNSCC | 1 (2%) | |

| Stage | I | 1 (2%) |

| III | 20 (37%) | |

| IVA | 24 (44%) | |

| IVB | 9 (17%) | |

| T stage | 1 | 5 (9%) |

| 2 | 9 (17%) | |

| 3 | 21 (39%) | |

| 4 | 18 (33%) | |

| X | 1 (2%) | |

| N stage | 0 | 21 (39%) |

| 1 | 6 (11%) | |

| 2 | 21 (39%) | |

| 3 | 6 (11%) | |

| Second cancer | Yes | 8 (15%) |

| No | 46 (85%) | |

| ECOG PS | 0 | 5 (9%) |

| 1 | 20 (37%) | |

| 2 | 26 (48%) | |

| 3 | 3 (6%) | |

| Hearing impairment | Yes | 11 (20%) |

| Unknown | 43 (80%) | |

| CKD | GFR > 90 mL/min | 14 (26%) |

| GFR 60–89 | 27 (50%) | |

| GFR 30–59 | 12 (22%) | |

| GFR 15–29 | 1 (2%) | |

CKD = chronic kidney disease, ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, F = female, GFR = glomerular filtration rate, HNSCC = head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, IQR = interquartile range, M = male, N = node, PS = performance status, T = tumor.

Compliance

Forty-six (85%) patients had optimal dose of carboplatin, defined as at least two doses of carboplatin at AUC 4.5 to 5. Fifty (93%) patients were given an optimal dose of radiation therapy, defined as ≥ 60 Gy. Fortyeight (89%) patients received a total of 70 Gy.

Efficacy

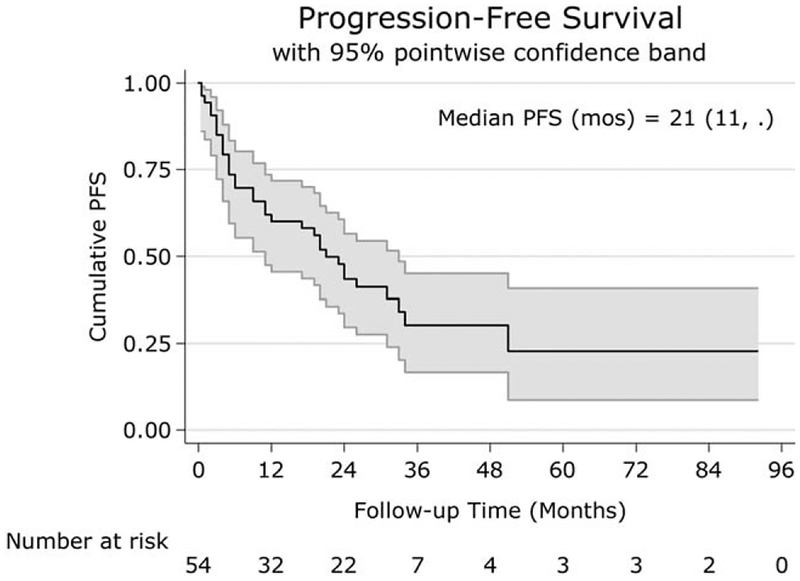

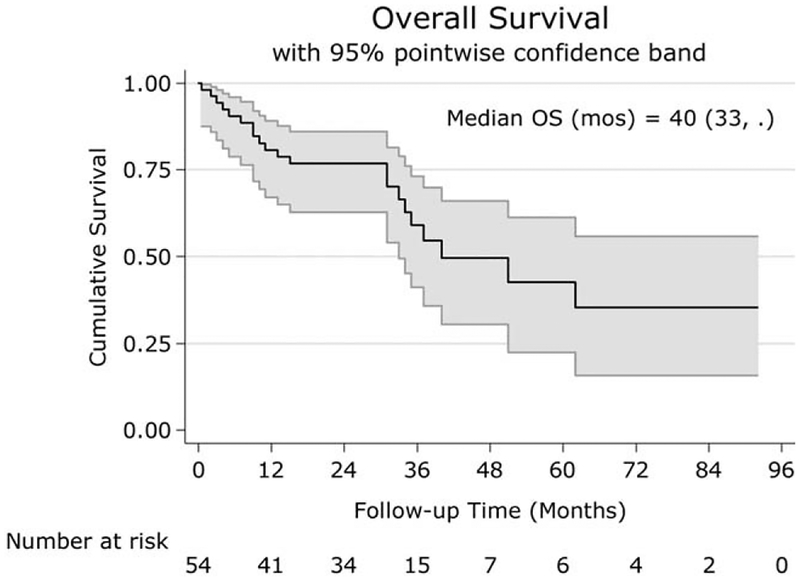

Overall LRC rate was 50% (95% confidence interval [CI] 37%–63%). Laryngectomy rate in LC patients was 41% (CI 25%–59%). Median PFS was 21 (CI 11–33) months (Fig. 1). Median OS was 40 (CI 33–NA) months (Fig. 2). The 1, 3, and 5-year OSs were 81% (CI 67%–89%), 59% (CI 41%–73%), and 42% (CI 22%–61%), respectively. Stage III/IVa patients (n = 45) had a median OS of 62 (CI 37–NA) months and a 3-year OS of 71% (CI 53%–84%), whereas stage IVb (n = 9) had a median OS of 31 (CI 4–NA) months, and none survived to 3 years.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan Meir curve of PFS for all patients. The x-axis shows the follow-up time in months, and the y-axis shows the cumulative PFS. Median PFS was 21 months.

PFS = progression-free survival.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan Meir curve of OS for all patients. The x-axis shows the follow-up time in months, and the y-axis shows the cumulative survival. The 1, 3, and 5-year OS were 81%, 59%, and 42%, respectively.

OS = overall survival.

Safety

Dysphagia was the most common AE: 21 patients with grade 2 (39%) and 20 with grade 3 (37%). Thirteen (24%) patients had percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy during therapy. Myelosuppression was also common, with ≥ grade 3 anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia seen in 17%, 13%, and 15% of patients, respectively (Table II). One patient died 6 days after completion of chemoradiation therapy. The cause of death was documented to be from ileus resulting in bowel perforation, which was considered not related to therapy.

TABLE II.

Adverse Events.

| All Grades | Grade 3, 4 | |

|---|---|---|

| Dysphagia | 41 (76%) | 20 (37%) |

| Dehydration | 3 (6%) | 3 (6%) |

| Anemia | 27 (50%) | 9 (17%) |

| Neutropenia | 15 (28%) | 7 (13%) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 14 (26%) | 8 (15%) |

| PEG during chemo RT | Yes: 7 (13%); No: 47 (87%) | |

PEG = percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, RT = radiotherapy.

DISCUSSION

Comparison of Cisplatin and Carboplatin

Mechanism of Action.

Both cisplatin and carboplatin are platinum (II) complexes with two ammonia groups in the cis position. The major cytotoxic target of cisplatin and carboplatin is DNA. The pharmacologic behavior of cisplatin is determined largely by an initial aquation reaction in which the chloride groups are replaced by water molecules. The aquated platinum complex can then react with a variety of macromolecules.7 The cytotoxicity of cisplatin against neoplastic cells correlate closely with platinum DNA interstrand cross-links and to the formation of intrastrand bifunctional N-7 adducts at d(GpG) and d(ApG).8

Carboplatin has a mechanism of action similar to that of cisplatin. Carboplatin induces the same platinum-DNA adducts as those induced by cisplatin; however, Hongo et al. have demonstrated that carboplatin required a 10 times higher drug concentration and 7.5 times longer incubation time than cisplatin to induce the same degree of conformational change on plasmid DNA.

Cisplatin.

Results from the RTOG 91–11 trial showed that only 120 of 172 patients (70%) treated with high-dose bolus cisplatin (100 mg/m2 on days 1, 22, and 43) completed all their cycles. Median age in this arm was 60 (range 26–78) years. The majority (96%) of the patients had a Karnofsky performance score of 80 or more; only 4% of the patients had a performance score of 60 to 80. Common AEs included nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, nausea, vomiting, stomatitis, dysphagia or odynophagia, and hematologic side effects.5

Carboplatin.

Carboplatin is known to be more myelosuppressive than cisplatin but causes less neurotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, and nausea with hyperemesis.9 Carboplatin is not as effective as cisplatin for its direct antitumor effect.7 It is not clear whether carboplatin is as effective of a radiosensitizer as cisplatin.

In theory, carboplatin could replace cisplatin in some patients who have contraindications to cisplatin, especially in patients with renal insufficiency, baseline hearing impairment, and borderline performance status, or those who may have difficulty tolerating the fluid volume associated with high-dose cisplatin.

In one randomized study in patients with locally advanced nasopharyngeal cancer, concurrent CRT using carboplatin demonstrated comparable efficacy and better tolerability when compared to concurrent CRT with cisplatin.10 Data regarding the outcomes of LA-SCCHN patients treated with carboplatin-based CRT remains limited.

Definitive Chemoradiotherapy

Definitive concurrent CRT is considered the standard of care for organ preservation and is the only potentially curative therapy in surgically unresectable patients with stage III to IVb, LA-SCCHN. The Intergroup Phase III Trial was one of the earlier trials that established concurrent CRT with cisplatin.4 In this trial, 295 patients were randomized among three arms: radiation therapy alone (arm A), radiation with concurrent cisplatin (arm B), and split-course radiation with cisplatin/5-fluorouracil (5FU). The 3-year OS for patients enrolled in arm A was 23% (median 12.6 months), compared with 37% (19.1 month) for arm B (P = 0.014) and 27% (13.8 months) for arm C (P = not significant). Of note in this trial, 96.3% of the patients had stage IV, and 85% had tumor (T)4 or nodal (N)3 disease.

The RTOG 91–11 was another randomized trial that evaluated the role of cisplatin in concurrent CRT.5 Five hundred twenty patients with stage III IV LA-SCCHN were randomized among three arms: induction chemotherapy (cisplatin/5FU) followed by radiation, concurrent CRT with cisplatin, and radiation alone. Concomitant CRT with cisplatin resulted in a 54% relative reduction in risk of laryngectomy compared with radiation alone (hazard ratio [HR], 0.46; 95% CI, 0.30–0.71; P = 0.001). Overall survival did not differ in any of the treatment comparisons, with 5- and 10-year estimates of 55% and 28% for concurrent, and 54% and 32% for radiation alone, respectively.

The benefit of concurrent CRT was also demonstrated in the meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer.11 Concurrent chemotherapy significantly decreased the risk of death compared with definitive local therapy alone (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.78–0.86). This was associated with a 6.5 percent (%) absolute decrease in mortality at 5 years. However, in this meta-analysis of 93 randomized trials with 17,346 patients, patients were treated with various concurrent chemotherapy regimens between 1965 to 2000.

Chemoradiotherapy With Cetuximab

Bonner et al. 12 reported a randomized trial of cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody against the epidermal growth factor receptor, given concurrently with radiation to patients with LA-SCCHN. Two-year OS rate was 62% versus 55%, and at 3 years was 55% versus 45%, favoring the combination regimen.12 The unique aspect of this trial was that it allowed patients with a Karnofsky performance score of at least 60; the age range was between 34 to 83 years. However, the median age in the concurrent arm was 56 years, and the majority (90%) of patients in this arm had a Karnofsky performance score of 80 or more.

The addition of cetuximab to chemoradiation therapy also has been studied. In the RTOG-0522, the addition of cetuximab to cisplatin CRT showed no benefits in outcomes of locoregional control, OS, PFS but with more AEs.13

Cetuximab has never been compared head to head to chemotherapy in the setting of concurrent chemoradiation in LA-SCCHN.

Chemoradiotherapy With Carboplatin

The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS data on patients treated with concurrent chemoradiation with carboplatin were 81% (CI 67–89%), 59% (CI 41–73%), and 42% (CI 22–61%), respectively. These results are comparable to historical data from patients treated with concurrent chemoradiation with cisplatin, with the Intergroup Phase III Trial showing 3-year OS rate of 37%, and with the RTOG 91–11 showing a 2-year OS rate of 74% and a 5-year OS rate of 54%. Our data is also comparable to the Bonner trial, where concurrent chemoradiation given with cetuximab showed a 2-year OS rate of 62% and a 3-year rate at 55%.

Locoregional control was at 50% (95% CI 37–63%) in our cohort; however, this may be due to the small number of patients (n = 27). It must also be noted, that although the RTOG 91–11 trial showed locoregional control rate of 83.6%, T4 patients were excluded from the RTOG 91–11, and the majority of patients on this study had stage III disease with only 36% had stage IV disease, whereas in our patients, only 39% had stage III or less.

Carboplatin has been used with concurrent therapy in various dosing protocols. For example, Calias et al. established the regimen of three cycles of carboplatin 70 mg/m2/d + 5FU 600 mg/m2/d D1–4 with standard radiation therapy of 70 Gy. The 3-year OS was 51% (95% CI = 39%–68%) versus 31% (95% CI = 18%–49%) for patients treated with chemoradiation with this regimen versus radiation therapy alone (P = 0.02). The locoregional control rate was also improved in the chemoradiation arm (66%; 95% CI = 51%–78%) versus radiation-alone arm (42%; 95% CI = 31%–56%).14

This regimen of three cycles of carboplatin 70 mg/m2/d + 5FU 600 mg/m2/d D1–4 was also utilized in the GORTEC 2007–01 phase III trial.15 This trial compared concurrent cetuximab and chemotherapy with radiation to concurrent cetuximab with radiation therapy in nonoperated LA-SCCHN. The 3-year PFS rate and locoregional control rates were improved in the chemotherapy plus cetuximab arm. However, OS was not different between both arms (HR = 0.80; 95% CI 0.61 = 1.05; P = 0.11).

Carboplatin 70 mg/m2/d given D 1 to 4 would equal to a total of carboplatin 280 mg/m2 per cycle. Because of the rather linear association between carboplatin clearance and glomerular filtration rate, its pharmacology supports the use of the AUC method rather than a fixed mg/m2 method.16

A recent meta-analysis out of China17 showed that cisplatin-based chemotherapy significantly improved 5-year OS (HR = 0.67, 95% CI, 0.49–0.91; P = 0.01) compared to the carboplatin group. No difference in the 3-year OS/LRC was observed. However, this meta-analysis included patients with stage II to IV disease and some neoadjuvant setting patients who ultimately underwent surgery. Not all the patients underwent definitive therapy with concurrent radiation.

In a single-institution retrospective review,18 the use of triweekly carboplatin (AUC 5, days 1, 22, and 43) in the definitive concurrent CRT for stage III to IV oropharyngeal carcinoma patients were reported. The 3-year locoregional control and OS rates for were 88% and 82%, respectively. The authors concluded that this regimen was more feasible than concurrent triweekly high-dose cisplatin with similar/favorable disease control and survival rates. However, human papilloma virus status was not reported.

The limitations of this study are its retrospective nature and the single-arm design with a small sample size from a single institution. As discussed earlier, large-volume high-quality data on carboplatin given as a single agent for definitive concurrent CRT for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma are limited. To our knowledge, this has never been compared head to head because these patients with contraindications to cisplatin simply cannot be randomized to cisplatin or carboplatin.

Our data, which included patients with renal insufficiency and baseline hearing impairment, as well as elderly patients and patients with borderline performance status, shows that definitive CRT with carboplatin for LA-SCCHN was well tolerated and demonstrated results comparable to CRT with cisplatin even in this challenged patient population.

CONCLUSION

Definitive CRT with carboplatin for LA-SCCHN was well tolerated and demonstrated comparable results to CRT with cisplatin.

Acknowledgments

The authors have not received any grants of funding for this study and have no conflicts of interest to declare. All authors made substantial contribution to the article; M.N. and A.S. contributed to the design, acquisition, analysis, interpretation of the data and prepared the first draft. M.Z., M.I., H.K., and J.A. contributed to the critical interpretation of the data and revised the article. J.A. provided statistical analysis. The final article was reviewed and approved by all authors. Both M.N. and A.S. had full access to all the data in the study and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. We indicate here that preliminary results of this study have been published electronically as an abstract in conjunction with the 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting; J Clin Oncol 34, 2016 (suppl; abstr e17538). The authors have not published or submitted any other related articles from the same study.

The authors thank their patients, the families of their patients, and their colleagues at Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit, Michigan, who supported them in the preparation of this article.

Footnotes

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seigel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2016; 66:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibson MK, Forastiere A. Multidisciplinary approaches in the management of advanced head and neck tumors: state of the art. Curr Opin Oncol 2004;16:220–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adelstein DJ, Li Y, Adams GL, et al. An intergroup phase III comparison of standard radiation therapy and two schedules of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forastiere AA, Zhang Q, Weber RS, et al. Long-term results of RTOG 91–11: a comparison of three nonsurgical treatment strategies to preserve the larynx in patients with locally advanced larynx cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:845–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhat ZY, Cadnapaphornchai P, Ginsburg K, et al. Understanding the risk factors and long-term consequences of cisplatin-associated acute kidney injury: an observational cohort study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0142225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Go RS, Adjei AA. Review of the comparative pharmacology and clinical activity of cisplatin and carboplatin. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:409–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roberts JJ, Knox RJ, Pera MF, et al. The role of platinum-DNA interactions in the cellular toxicity and anti-tumor effects of platinum coordination compounds In: Nicolini M, ed. Platinum and Other Metal Coordination Compounds in Cancer Chemotherapy. Boston, MA: Martinus Wighoff; 1988: 16–31. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fountzilas G, Ciuleanu E, Dafni U, et al. Concomitant radiochemotherapy vs radiotherapy alone in patients with head and neck cancer: a Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group phase III study. Med Oncol 2004;21: 95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chitapanarux I, Lorvidhaya V, Kamnerdsupaphon P, et al. Chemoradiation comparing cisplatin versus carboplatin in locally advanced nasopharyngeal cancer: randomised, non-inferiority, open trial. Eur J Cancer 2007;43:1399–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pignon JP, le Maitre A, Emilie Maillard E, Bourhis J; MACH-NC Collaborative Group. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): an update on 93 randomised trials and 17,346 patients. Radiother Oncol 2009;92:4–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 2006;354: 567–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ang KK, Zhang Q, Rosenthal DI, et al. Randomized phase III trial of concurrent accelerated radiation plus cisplatin with or without cetuximab for stage III–IV head and neck carcinoma: RTOG 0522. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:2940–2950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calais G, Alfonsi M, Bardet E, et al. Randomized trial of radiation therapy versus concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for advancedstage oropharynx carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:2081–2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bourhis J, Sun XS, Sire C, et al. Cetuximab-radiotherapy versus cetuximab plus concurrent chemotherapy in patients with N0-N2a squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN): results of the GORTEC 2007–01 phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(suppl): abstract 6003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calvert AH, Newell DR, Gumbrell LA, et al. Carboplatin dosage: prospective evaluation of a simple formula based on renal function. J Clin Oncol 1989;7:1748–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guan J, Li Q, Zhang Y, et al. A meta-analysis comparing cisplatin-based to carboplatin-based chemotherapy in moderate to advanced squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck (SCCHN). Oncotarget 2016;7: 7110–7119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iganej S, Buchschacher GL, Abdalla IA. Triweekly carboplatin alone in the treatment of oropharyngeal carcinoma with definitive concurrent chemoradiation: Outcomes of 120 unselected patients and a comparison to the RTOG 0129 regimen results. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(suppl): abstract e16031. [Google Scholar]