Approximately 18% of Canadian adults use cannabis, which has increased from 14% since the legalization of recreational marijuana.1 However, less than 2% of Canadians are registered medical cannabis users.2,3 Chronic pain is a common reason for using cannabis.4,5 Because neuropathic pain, a subset of chronic pain, affects approximately 8% of patients and is challenging for physicians and patients to manage adequately, an understanding of cannabinoid therapies (ie, prescription cannabinoids or cannabis) is important (Box 1).6–9 This article will review the evidence for cannabinoids in refractory neuropathic pain and highlight tools to assist family physicians who seek practical guidance in advising, authorizing, prescribing, and monitoring cannabinoids. We acknowledge that there are various viewpoints on the role of cannabinoids and we offer multiple considerations.

Box 1. Overview and definitions.

The following provides an overview of relevant terminology

Cannabinoid: Any compound that activates a cannabinoid receptor (eg, prescription cannabinoid and cannabis). The most studied, although still poorly understood, are THC and CBD

Cannabinoid receptors: CB1 receptors (primarily in the central and peripheral nervous system) and CB2 receptors (primarily in the immune system) are part of the endocannabinoid system

Prescription cannabinoids: Nabilone or nabiximols (see Table 19 for details)

Cannabis: Marijuana; available legally from a licensed producer or licensed retailer

Licensed producer: Regulated by Health Canada; requires prescribers to authorize medical cannabis via a medical document

Licensed retailer: A regulated retailer or licensed dispensary; regulated by each province and territory, as government-operated, privately licensed stores, or online. Medical oversight is not required

CBD—cannabidiol, THC—tetrahydrocannabinol.

Case description: Mr Wilson

Mr Wilson, an 81-year-old who lives independently with his wife, has been a patient of yours for a long time. Three weeks ago he had an emergency department (ED) visit owing to dizziness and a near fall, and was told to follow up with his family physician if he continued to feel dizzy.

His medical history includes neuropathic pain secondary to long-standing type 2 diabetes mellitus, spinal osteoarthritis, and chronic insomnia. He is an ex-smoker. The discharge summary indicates that findings of the computed tomography scan of his brain were normal and that laboratory test results revealed that complete blood count, renal panel findings, extended electrolyte levels, and random blood glucose level were within normal range. His recent hemoglobin A1c measurement was 7.5%. His blood pressure was 128/84 mm Hg, with no orthostatic drop, and his heart rate was 72 beats/min. Neurologic and cardiac assessments were done, and no evidence of underlying disease was found. Findings of Dix-Hallpike maneuvers were negative.

According to your records, Mr Wilson is currently taking 75 mg of pregabalin twice daily, 60 mg of duloxetine daily, 850 mg of metformin twice daily, 40 units of insulin glargine at night, 20 mg of rosuvastatin daily, 5 mg of ramipril daily, 7.5 mg of zopiclone at night as required (2 or 3 times per week), and 1000 units of vitamin D daily. You recall that nortriptyline was trialed without success a few years ago (it had caused drowsiness and constipation at a dose of 100 mg at night), but after he was switched to pregabalin, Mr Wilson reported some improvement. About a year ago, duloxetine was added, and Mr Wilson reported further improvements in his diabetic neuropathy. Furthermore, Mr Wilson has previously expressed that he wants to avoid opioids “at all costs.”

Mr Wilson is still experiencing dizziness, and on today’s examination, his blood pressure and heart rate are 120/70 mm Hg and 68 beats/min, respectively, with no orthostasis. You confirm his current medication regimen, with no changes made over the past several months. However, upon routine cannabinoid screening, you discover that Mr Wilson was given cannabidiol (CBD) oil 3 months ago by his son to try to help with his nerve pain. You ask Mr Wilson to complete a Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test–Revised (https://bpac.org.nz/BPJ/2010/June/docs/addiction_CUDIT-R.pdf), on which he scores 4, indicating no hazardous cannabis use.10

Importance of cannabinoid screening

Screening for cannabinoid use, even in older adults, is important given the prevalence of cannabis use. Patients might contemplate self-medicating with cannabis for various reasons, including viewing cannabis as a “natural” (and therefore “safe”) alternative, or for managing medical conditions not adequately controlled by their current drug therapy.9 Prescription cannabinoids (ie, nabiximols and nabilone), when dispensed by a community pharmacy, are captured by provincial or territorial electronic prescription databases. Cannabis is not captured by these databases, which makes it easy to miss unless it is specifically asked about, as was the case with Mr Wilson. When screening, it might be helpful to ask patients separately about medical and recreational (or nonmedical) cannabis or marijuana. Also, prompting patients by asking about specific products such as “CBD oil” or “topical cannabis” might be useful, as these products are not always viewed as medications by patients.

Back to Mr Wilson

Physician: I’m sorry that your nerve pain is still causing problems. I didn’t realize how much it was bothering you. Thank you for sharing about your CBD oil though, as it is helpful for your assessment. Did you bring the CBD oil with you?

Mr Wilson: I have a picture of it on my phone. It’s really helping me. I started at 1 drop at night and now I take 16 drops. I think my son said it was safe to go up to 40 drops, but I didn’t need that much. He picked this one because it just has CBD in it. (The label reads CBD 100 mg/mL.)

Physician: May I make a suggestion about what I think could be the possible cause of your dizziness? [Mr Wilson nods.] I’m concerned that this CBD oil might be contributing to this.

Mr Wilson: But I thought CBD is safe because it doesn’t get you high.

Bringing evidence to practice: cannabinoid adverse effects

Cannabinoids can cause many adverse effects that are often underappreciated by patients or their families, such as with Mr Wilson and his son (Table 2).9 Most cannabinoid trials enrol experienced users and exclude older adults and those with comorbidities common among aging patients.11,12 Interestingly, the risk of adverse effects might even be higher in older adults owing to greater cannabinoid exposure (eg, slower cannabis metabolism and increased fat tissue) compared with younger adults.11 Cannabis also appears to increase the risk of ED visits. A survey of 14 715 individuals aged 50 years or older found that 30.9% of cannabis users visited the ED compared with 23.5% of nonusers (P < .001).13 Patients, especially older adults, are at risk of cannabinoid-related adverse effects and should be educated about and monitored for these effects.

Table 2.

Adverse effects of cannabinoids to assess or monitor

| ADVERSE EFFECT | CANNABINOID EVENT RATE, % | PLACEBO EVENT RATE, % | NUMBER NEEDED TO HARM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall adverse effects | 81 | 62 | 6 |

| Withdrawal due to adverse effects | 11 | Approximately 3 | 14 |

| “Feeling high” | 35 | 3 | 4 |

| Sedation | 50 | 30 | 5 |

| Dizziness | 32 | 11 | 5 |

| Speech disorders | 32 | 7 | 5 |

| Ataxia or muscle twitching | 30 | 11 | 6 |

| Hypotension | 25 | 11 | 8 |

Data from Allan et al.9

Cannabinoid therapies can cause dizziness. A systematic review found 3 systematic reviews of cannabinoids versus placebo assessing this adverse effect.12 The largest systematic review included 41 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comprising 4243 participants and found an increased risk of dizziness (odds ratio of 5.09, 95% CI 4.10 to 6.32).14 Increased dizziness with cannabinoid therapy was also found by Wade et al (3 RCTs including 666 participants; 32% vs 11% experienced dizziness; number needed to harm of 5) and by Mücke et al (4 RCTs including 823 patients), who found a numerical, although not statistical, increase in dizziness (risk difference of 3%, 95% CI −2% to 8%).15,16 Furthermore, cannabinoid therapy is active in the central nervous system (CNS) and it can interact with other CNS-active drugs. The American Geriatric Society Beers criteria recommend avoiding the use of 3 or more CNS-active drugs.17 Mr Wilson is currently taking 4 CNS-active drugs (ie, pregabalin, zopiclone, duloxetine, cannabis oil), which increases his risk of harm, including dizziness.

Whether CBD alone causes dizziness is unstudied; however, all cannabis oil purchased from a legal source in Canada (ie, licensed producers or licensed retailers) will provide labeled concentrations for both CBD and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) (see Box 2 for cannabis oil considerations).18 Therefore, it is likely that Mr Wilson was given illegal cannabis oil, as the label only listed the concentration for CBD, and that Mr Wilson’s cannabis oil does contain an unspecified amount of THC despite no labeled concentration. In addition, products purchased from a legal source will have an excise stamp on the packaging and a standardized cannabis symbol (if the product contains greater than 10 μg of THC per gram), which can be another clue about the source of cannabis.19,20 To date, all legal cannabis products in Canada contain both CBD and THC.

Box 2. Cannabis oil considerations.

Most patients will report cannabis oil dose in drops or millilitres per day. However, it is important to know the milligram dose of CBD and THC. The concentration (ie, mg/mL) of CBD and THC should be reported on the product’s label

- Cannabis dose calculation using Mr Wilson as an example:

- - Cannabis oil bottle label reads CBD 100 mg/mL; THC concentration is not reported

- - Mr Wilson is taking 16 drops per day, which is about 0.8 mL/d (rule of thumb: approximately 20 drops per mL)

- - Mr Wilson is taking approximately 80 mg of CBD per day

CBD—cannabidiol, THC—tetrahydrocannabinol

Back to Mr Wilson

Physician: There really is no such thing as a safe type of cannabis. In fact, about 1 in 5 patients taking a cannabinoid medication will become dizzy. I am especially concerned when the cannabis is combined with your other medications that put you at risk of falling.

Mr Wilson: So, you want me to stop the CBD oil? But, won’t my pain come back? I don’t feel very good about that.

Bringing evidence to practice: diabetic neuropathic pain management and cannabinoid therapy

Before considering cannabinoid therapy, it is important to discuss goals of therapy with Mr Wilson and assess his previous medication trials. An understanding of Mr Wilson’s perceived benefit with cannabis oil is essential. Focusing on functional goals—that is, goals where success is measured by improvements in activities of daily life (eg, ability to play with grandchildren, garden, get groceries)—versus relying solely on pain scores is central to managing chronic pain.6,21 It is also important to set realistic expectations regarding benefits that can be achieved pharmacologically. For example, a 30% or 50% reduction in pain are common efficacy outcomes assessed in chronic pain RCTs to indicate success; however, some patients might believe that drug therapy will reduce their pain to zero. Because Mr Wilson reported some improvement with both pregabalin and duloxetine, but still pursued self-medicating with cannabis, it would be worthwhile to discuss and set functional goals while emphasizing that complete elimination of pain is unrealistic. In addition, even for patients who might feel as though they have “tried everything,” there is often still an opportunity to optimize therapies. Guidelines recommend nonpharmacologic treatment such as exercise, physiotherapy, and psychological therapies in all patients.7 Furthermore, many patients perceive a drug therapy to have failed, but have not undergone an adequate trial. For example, most medications need to be titrated to an effective dose and used for at least 6 weeks (and likely 3 months) to realize benefit.9 Of note, older adults usually require lower doses and slower medication titration than younger adults do (see Geri-RxFiles available at www.RxFiles.ca for further dosing information).22

Currently, cannabinoids are considered a third- or fourth-line treatment alternative for chronic neuropathic pain after patients fail tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentinoids, and selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor antidepressants.7,9 For Mr Wilson, cannabinoids might be a reasonable alternative, as he has trialed nortriptyline, pregabalin, and duloxetine. A 2018 Cochrane meta-analysis of 10 RCTs of patients (1586 participants) experiencing chronic neuropathic pain found that cannabinoids compared with placebo increased the number of patients achieving a 30% or greater reduction in pain with a number needed to treat of 11 (moderate quality of evidence).23 However, there was no difference in patients with diabetic neuropathy based on a subgroup analysis of 2 RCTs (327 participants).23 In addition, the review attempted to meta-analyze a functional outcome—patient reported global impression of pain—but the quality of evidence was low and further study is required.23

Although cannabinoids have been studied in chronic neuropathic pain as outlined above, important limitations exist. Most RCTs included fewer than 100 participants (range 20 to 339), between the ages of approximately 25 to 60 years (up to 70 years), and assessed the prescription cannabinoid nabiximols.23 None of the RCTs assessed cannabis oil.23 Two RCTs assessed nabilone (but were not included in the meta-analysis).23 Most RCTs were 12 weeks in duration (up to 26 weeks), and long-term benefit is unknown.23 This was further assessed in a systematic review by Allan et al, in which short RCTs (up to 5 weeks) found positive results and longer RCTs (9 to 15 weeks) found neutral results.12 Thus, cannabinoid effects, especially long-term, remain unknown in older adults, such as Mr Wilson.

Potential management approaches for Mr Wilson

Managing refractory chronic neuropathic pain is challenging; however, there are a few interventions that Mr Wilson would likely benefit from. Goals of care, with an emphasis on function, should be discussed, and Mr Wilson should be reminded that drug therapy is unlikely to reduce his pain level to zero. Nonpharmacologic therapy is helpful and should be explored (eg, psychotherapy, physiotherapy, supervised activity program). An outline of many nonpharmacologic therapies is available online at www.RxFiles.ca/painlinks.

Various drug therapy approaches for refractory chronic neuropathic pain are reasonable and depend on many variables such as patient characteristics and values. For Mr Wilson, it might be reasonable to trial an increased dose of either 90 mg of duloxetine daily or 75 mg of pregabalin in the morning and 150 mg at night for 3 months while weighing the potential for benefits and adverse effects.24,25

Given that Mr Wilson’s cannabis oil is likely illicit and associated with the onset of his dizziness, he should be encouraged to stop using it, or at least to decrease the dose (although it is important to note that Mr Wilson might not follow medical advice). Tapering is advised when stopping, as withdrawal symptoms (eg, anxiety, sweating, and sleep disturbances) have been reported when cannabinoids are used daily for a few weeks to months.26 While the optimal tapering regimen is unknown, in non-frail elderly patients like Mr Wilson, decreasing the dose by 25% every 1 to 2 weeks as tolerated is reasonable while monitoring for dizziness resolution, cannabis withdrawal symptoms, and effects on function.27 You might choose to provide Mr Wilson with a cannabis patient booklet, which highlights some cannabis myths and adverse effects (available at www.RxFiles.ca).28

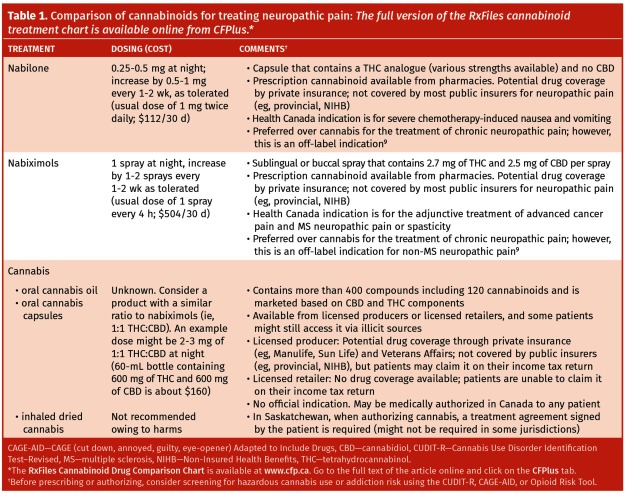

If alternative cannabinoid therapy is explored (see Table 1 for cannabinoid product details9 and the full version of the RxFiles cannabinoid treatment chart available online from CFPlus*), Mr Wilson should likely be titrated off or given a reduced dose of duloxetine or pregabalin to minimize additive CNS adverse effects.9 Prescription cannabinoids are preferred over cannabis, as most RCTs assessed these products, dosing guidance is available, provincial and territorial electronic prescription databases capture these products aiding in cannabinoid screening, and the products meet prescription-level quality standards. However, cost might be prohibitive, especially with nabiximols. It would be important to initiate the cannabinoid at a low dose and increase it every few days or weekly, and a reasonable trial duration would be approximately 3 months. In general, the best approach will be patient-centred.

Table 1.

Comparison of cannabinoids for treating neuropathic pain: The full version of the RxFiles cannabinoid treatment chart is available online from CFPlus.*

Conclusion

Overall, there are many unknowns and uncertainties about the optimal role of cannabinoids in older adults for refractory neuropathic pain. Until more robust data are available, ensure other nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies are optimized and that patients have failed at least 3 other agents before initiating cannabinoid therapy. Patients might be curious and want to explore cannabinoid therapy, so it is important to screen for cannabinoid use, monitor for potential adverse effects, and engage with patients. In addition, cannabinoid-related tools for practice exist to assist family physicians who seek practical guidance for delivering patient care.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lynette Kosar and Loren Regier for their review of this article.

Footnotes

The RxFiles Cannabinoid Drug Comparison Chart is available at www.cfp.ca. Go to the full text of the article online and click on the CFPlus tab.

Competing interests

RxFiles and contributing authors do not have any commercial competing interests. RxFiles Academic Detailing Program is funded through a grant from Saskatchewan Health to the University of Saskatchewan; additional “not for profit; not for loss” revenue is obtained from sales of books and online subscriptions. No financial assistance was obtained for this publication.

This article is eligible for Mainpro+ certified Self-Learning credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro+ link.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro de novembre 2019 à la page e469.

References

- 1.National Cannabis Survey 1st quarter, 2019. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2019. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2019032-eng.htm. Accessed 2019 Jul 1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cannabis Survey, fourth quarter 2018. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2018. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/190207/dq190207b-eng.htm. Accessed 2018 Apr 26. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Cannabis Survey, third quarter 2018. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada; 2018. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/181011/dq181011b-eng.htm. Accessed 2018 Apr 26. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baron EP, Lucas P, Eades J, Hogue O. Patterns of medicinal cannabis use, strain analysis, and substitution effect among patients with migraine, headache, arthritis, and chronic pain in a medicinal cannabis cohort. J Headache Pain. 2018;19(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s10194-018-0862-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boehnke KF, Gangopadhyay S, Clauw DJ, Haffajee RL. Qualifying conditions of medical cannabis license holders In the United States. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38(2):295–302. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05266. Erratum in: Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38(3):511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grinzi P. The inherited chronic pain patient. Aust Fam Physician. 2016;45(12):868–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moulin D, Boulanger A, Clark AJ, Clarke H, Dao T, Finley GA, et al. Pharmacological management of chronic neuropathic pain: revised consensus statement from the Canadian Pain Society. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19(6):328–35. doi: 10.1155/2014/754693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torrance N, Smith BH, Bennett MI, Lee AJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain of predominantly neuropathic origin. Results from a general population survey. J Pain. 2006;7(4):281–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allan GM, Ramji J, Perry D, Ton J, Beahm NP, Crisp N, et al. Simplified guideline for prescribing medical cannabinoids in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:111–20. (Eng), e64–75 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adamson SJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Baker AL, Lewin TJ, Thornton L, Kelly BJ, et al. An improved brief measure of cannabis misuse: the Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test–Revised (CUDIT-R) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110(1–2):137–43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.017. Epub 2010 Mar 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minerbi A, Häuser W, Fitzcharles MA. Medical cannabis for older patients. Drugs Aging. 2019;36(1):39–51. doi: 10.1007/s40266-018-0616-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allan GM, Finley CR, Ton J, Perry D, Ramji J, Crawford K, et al. Systematic review of systematic reviews for medical cannabinoids. Pain, nausea and vomiting, spasticity, and harms. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:e78–94. Available from: www.cfp.ca/content/cfp/64/2/e78.full.pdf. Accessed 2019 Sep 23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi NG, Marti CN, DiNitto DM, Choi BY. Older adults’ marijuana use, injuries, and emergency department visits. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44(2):215–23. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2017.1318891. Epub 2017 May 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, Di Nisio M, Duffy S, Hernandez AV, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2456–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6358. Errata in: JAMA 2015;314(5):520, JAMA 2015;314(8):837, JAMA 2015;314(21):2308, JAMA 2016;315(14):1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wade DT, Collin C, Stott C, Duncombe P. Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of Sativex (nabiximols), on spasticity in people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2010;16(6):707–14. doi: 10.1177/1352458510367462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mücke M, Carter C, Cuhls H, Prüẞ M, Radbruch L, Häuser W. Cannabinoids in palliative care: systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy, tolerability and safety [article in German] Schmerz. 2016;30(1):25–36. doi: 10.1007/s00482-015-0085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674–94. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15767. Epub 2019 Jan 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perry D, Ton J, Allan GM. Evidence for THC versus CBD in cannabinoids. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:519. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canada Revenue Agency . EDN54 general overview of the cannabis excise stamps. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2018. Available from: www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/forms-publications/publications/edn54/general-overview-cannabis-excise-stamps.html. Accessed 2019 Jul 1. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Health Canada . Standardized cannabis symbol. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada; 2018. Available from: www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/laws-regulations/regulations-support-cannabis-act/standardized-symbol.html. Accessed 2019 Jul 1. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenquist EWK. Evaluation of chronic pain in adults. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2018. Available from: www.uptodate.com/contents/evaluation-of-chronic-pain-in-adults. Accessed 2019 Jul 1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geri-RxFiles. 3rd ed. Saskatoon, SK: University of Saskatchewan; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mücke M, Phillips T, Radbruch L, Petzke F, Häuser W. Cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;(3):CD012182. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012182.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lunn MP, Hughes RA, Wiffen PJ. Duloxetine for treating painful neuropathy, chronic pain or fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(1):CD007115. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007115.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geri-RxFiles. 3rd ed. Saskatoon, SK: University of Saskatchewan; 2019. Pain management in older adults. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Budney AJ, Hughes JR. The cannabis withdrawal syndrome. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19(3):233–8. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000218592.00689.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geri-RxFiles. 3rd ed. Saskatoon, SK: University of Saskatchewan; 2019. Tapering medications in older adults. [Google Scholar]

- 28.RxFiles . Cannabis. Questions about cannabis, and the answers that may surprise you. A booklet for people thinking about starting medical cannabis. Saskatoon, SK: University of Saskatchewan; 2019. Available from: www.rxfiles.ca/RxFiles/uploads/documents/Cannabis-Medical-Patient-Booklet.pdf. Accessed 2019 Sep 25. [Google Scholar]