Introduction

Inequitable access to healthcare across racial and ethnic groups remains problematic in the United States (US).1-2 Racial discrimination, which has a complex relationship to health and healthcare out-comes,3-4 has been associated with decreased access to procedures,5 decreased quality of care,6 decreased satisfaction with care,2 and increased prevalence of diseases.7-8 Paradies et al’s4 conceptual model links racial discrimination and negative health outcomes through three pathways: 1) denial of resources leading to poor living conditions and decreased quality and access to healthcare; 2) psychological stress leading to negative coping behaviors, physiological stress responses, and psychological symptoms; and 3) increased experiences with violent assaults.

The Chuukese are a rapidly growing ethnic group in the US and in Hawai‘i.9 Chuukese originate from the Federated States of Micronesia, one of the three nations with Compacts of Free Association (COFA) with the US. Along with other COFA citizens, Chuukese in the US are sometimes referred to as COFA migrants. The compacts followed the US’s involvement in Micronesia during the post-World War II period,10 including use of the region to test nuclear weapons. These actions disrupted Micronesia’s traditional cultures and subsistence lifestyles and led to western-diet-related chronic diseases.11 The compacts accorded US military access in exchange for infrastructure development. COFA citizens are allowed free entry and the right to work in the US, and many come to access education and health services, which are underdeveloped in Chuuk. While COFA migrants pay taxes, they are not able to fully participate in government programs such as Medicaid.12 This barrier is especially devastating as Micronesians have a high burden of infectious and chronic disease.13 A study analyzing Hawai‘i hospitalizations found that Micronesians are hospitalized younger and with a higher severity of illness than other ethnic groups, suggesting they may spend more years with severe illness or die younger.14 Racial discrimination may partly explain these health inequities.12,15-17

No studies have formally gauged racial discrimination in any Micronesian population. The objective of this study was to better understand: 1) the barriers, including racial discrimination, to obtaining healthcare for Chuukese in Hawai‘i; and 2) possible solutions to these barriers, including assets of the Chuukese community. We conducted in-depth interviews with Chuukese individuals and providers that serve Chuukese communities.

Materials and Methods

Measurement tool

IRB approval was obtained, and participants provided written and verbal consent. Interview guides were reviewed by experts in qualitative methods and Pacific Islander research. They were pilot-tested with Chuukese individuals, leading to rephrasing of questions. For example, questions needed to allow respondents to frame their answers in terms of incidents experienced by friends, family, or the community in general. This was done to avoid potential minimization bias due to embarrassment of disclosing personal victimization,18 to respect the Chuukese collectivist identity,19 and to gain an richer understanding of participants’ perspectives.20

Sampling.

Community participants were eligible to participate if they self-identified as Chuukese, were 18 years or older, currently lived in Hawai‘i and had accessed the Hawai‘i's healthcare system. Providers, including physicians, community health workers, and interpreters, were eligible to participate if they provided health services to Chuukese.

To ensure maximum variation, both purposive and referral sampling were used. Purposive, rather than random, sampling is commonly used in qualitative research when rich detailed data are desired.21 Referral sampling increases participation rates in low socioeconomic and minority populations.22

The sampling frame for providers was based on their employment [hospitals, community health centers (CHCs), or interpretation agencies], and if they were Chuukese themselves. Including both Chuukese and non-Chuukese providers allowed the capture of emic and etic perspectives. Some providers were identified through previous relationships fostered while the principal researcher (MKI) was herself a community health worker. Other interviewees were referred by other participants.

Purposive sampling for community participants was informed by a similar study23 and was dependent on age and language. Age was divided into 18-39 and 40 and above; the latter age group has a higher burden of chronic disease,24 which we hypothesized might affect their experience with the healthcare system. English language proficiency was defined by a self-reported need for an interpreter when accessing healthcare.

With community participants, steps were taken to respect Chuukese cultural protocols and mitigate difficulties due to racial discordance with the interviewer.3 These included meeting at locations chosen by participants26 and utilizing trusted community liaisons experienced in health work, and trained medical interpreters, to recruit and to co-facilitate interviews.25 Such trusted leaders in their communities facilitated more candid and in-depth conversations. Liaisons were also trained by the researcher in qualitative data collection, including the importance of confidentiality. To respect Chuukese culture’s strict gender roles, in which females usually speak about health issues for their families, we interviewed mostly women.26

Analysis

Interviews were conducted until thematic saturation was reached20 and all sampling categories were represented. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and reviewed by a bilingual research assistant for accuracy.

To analyze data, we used framework analysis,27 which allows the identification of themes both inductively from participants’ stories and deductively from existing literature, specifically Paradies et al.7 Each interview was coded by two researchers. A Chuukese research assistant reviewed coding for cultural relevance. Findings were reviewed and approved by community liaisons.

Results

Interviews were completed with eight providers and nine Chuukese community members. Providers included medical interpreters, physicians, managers, legal providers, and social workers. Three providers were Chuukese and were employed by CHCs, an interpretation agency, or both. The five non-Chuukese providers were employed by CHCs, a hospital, or both. Six of nine community participants were age 40 or older. Four (three age 40+) needed an interpreter for healthcare.

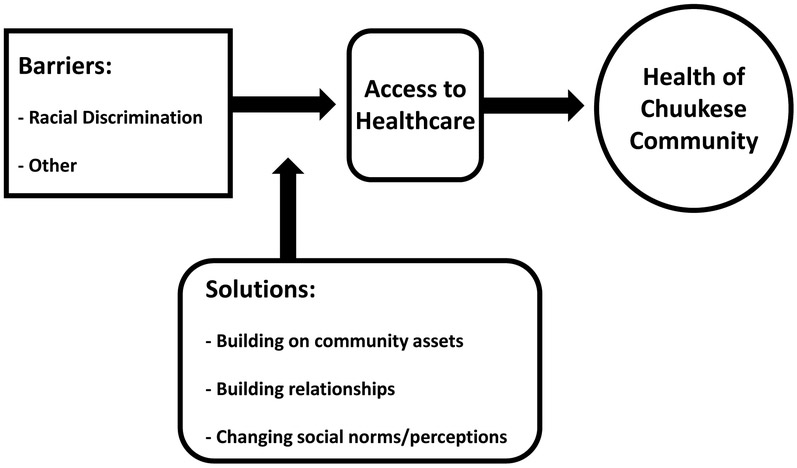

Our framework was based on Paradies’s4 conceptual model (Figure 1 below).

Figure 1.

Framework Analysis Model of Barriers and Solutions Contributing to the Health of Chuukese in Hawai‘i

Interviews were coded using five major themes; two were related to healthcare barriers (racial discrimination and other barriers) and three related to solutions, (building on community assets, building relationships, and changing social norms/perceptions). Findings are organized in relation to these themes with providers’ and community members’ contributions presented together as many of their answers were similar.

Theme 1: Barriers - other than racial discrimination.

Both providers and community participants reported a long list of barriers to care for the Chuukese. One Chuukese provider explained, “It’s just layer over layer…of disparities, and health problem[s] will rise from this.”

Many of the hurdles identified were those shared with other immigrant and low income communities, including financial barriers, food access, transportation, and health literacy. Other barriers included confusion about the healthcare system, difficulty communicating with providers, and inadequate insurance coverage due to national and state policies. Many of these issues were entwined in patient narratives.

All participants perceived that the migrants’ lack of ability to navigate healthcare arose from the differences between the US and Chuukese systems. In Chuuk, patients do not need appointments nor pay to see providers. Thus, migrants in Hawai‘i can feel overwhelmed by the prospect of seeing several physicians at different locations. One community member analogized the task of navigating the US healthcare system to “catching the bus… something that you would figure would be easy, but it’s not…so imagine how complicated healthcare is.” Providers reasoned that such system differences have resulted in migrants “not understanding the importance of showing up for appointments, especially with specialists.”

“No show” rates are exacerbated by the value that Chuukese place on community obligations. Thus, even if ill, individuals will skip appointments to attend to family needs. Consequentially, providers may thereby conclude that Chuukese patients are “non-compliant” and “do not care about their health.”

Additionally, providers’ lack of knowledge of Chuuk’s history and culture has led to disagreements. One provider explained:

One patient said, “Don't worry my care is free,” and the provider got mad and said, “It’s not free, tax payers pay for it!” And this poor lady was really embarrassed because she didn’t know that was how health plans worked.

Another barrier was lack of communication. In some cases, language and cultural differences, resulted in subpar care and lack of trust between patient and provider. One hospital provider depicted how language barriers led to an inability to share important medical information:

The biggest challenge we have is communication … Without interpreters we were not able to educate them on options that are available for their care. And bearing in mind that they come from a culture that’s very easy going, very laid back, very non-invasive when it comes to deliveries, to come to a medical center like this, especially if they’re a high-risk patient, it’s difficult to have them understand perhaps the severity of their own illness.

Improper handling of language barriers led to preventable tragedies, including “babies getting circumcised when the moms didn’t want it…and people waking up from surgery and not really knowing what happened.” In one case a mother and child fleeing an abusive partner were not assisted by a domestic violence hotline because there was no interpreter. Consequently, mother and child slept overnight at a bus stop.

Other communication barriers arose from cultural differences, such as the Chuukese desire to not cause conflict. One community participant explained:

There are some people who are afraid of speaking out. They will say yes when they mean no, they will say no when they mean yes. Not because that’s the actual answer, but I think they tell you what they think you like to hear.

Cultural beliefs surrounding the privacy of one’s health can also make communication difficult. Chuukese providers explained, “in our culture we kind of keep things to ourselves … only families can [know about health], sometimes even families cannot.” She elaborated that this can lead to reluctance to utilize interpreters because patients are “afraid we may know about their problems.” One non-Chuukese nurse explained this cultural difference can inhibit trusting relationships. She gave the example of Chuukese women “internalizing a lot of pain during delivery so it’s very difficult to build a relationship with them like most labor and delivery nurses do.”

Another barrier brought up by all participants was the lack of adequate insurance coverage. Not only is insurance unfamiliar to many migrants, but multiple changes to Medicaid eligibility have compounded confusion and mistrust. Many community participants reported not filling prescriptions or obtaining needed care for fear of receiving a bill. Providers echoed this sentiment:

There are certainly lots of stories floating around of people who gave up on healthcare… I think partly it’s that health insurance coverage is so messed up and so confusing that they just think “I don’t want to be a burden so I’ll just quit…I’ll quit my dialysis, I’ll quit my medicine.”

Many providers interpreted the health insurance issue to be discriminatory, noting that unequitable healthcare policies, whether intended or not, sent the devastating message, “We don’t care if you live or die.” One Chuukese provider shared, “I really felt personally that when the state singled out our community to put us on a different health plan, it’s almost like it's giving permission to the [general public] to lash out on us.” Several providers agreed that the effects of this “discriminatory policy” were perpetuated by negative media coverage of this group.

Theme 2: Barriers - racial discrimination

Almost all respondents spoke of receiving poor care or hearing insensitive remarks from providers, mostly at hospital settings. For example, one woman reported asking her doctor to remove her birth control implant because it was making her feel sick. The doctor refused and asked her, “Why do you want to get pregnant again?” making her feel frustrated and offended. For some it was difficult to make an appointment because front desk staff at both hospitals and CHCs were overtly “rude,” “hard,” or spoke in a “mean way. ”

When asked if this type of poor treatment was due to being Chuukese, the majority of community participants were unsure or hesitant to make this correlation. One woman said she would ask herself, “Is it me or is it them?” Another explained, “I don’t want to entertain that it’s because [we are] Chuukese…I tell myself not to think that way….Maybe that’s just how…some of the doctors are.” One community participant was apologetic for conjecturing that the unfair treatment was due to her race, “I don’t know, maybe I’m old and think too much. I’m sorry for saying this.”

Several providers confided that they had witnessed colleagues discriminating against Chuukese patients. One non-Chuukese provider disclosed that a non-Chuukese coworker referred all her Chuukese patients to other providers for “vague reasons.” A Chuukese interpreter explained she witnessed both “really good providers and providers who did not seem to care.”

Like community participants, providers could not be certain of the underlying reasons for a person’s action. One provider hypothesized the unfair treatment was due to “personal bias against the group as a whole.” One provider reported racial discrimination at a hospital. “I can just tell right away that they ‘re so discriminating on the Chuukese… They say ‘Oh these Micronesians, they have to learn what to eat ’.”

All providers working at CHCs and many community participants shared examples of overt racial discrimination towards Chuukese outside the healthcare system. Several participants reported encountering racial discrimination on a daily basis. “Just because [they are] Micronesian…[they are] treated as criminals…thieves,…and assumed to be the bad guys.” One provider explained,

I can tell that people are exhausted. I can tell people are just tired of dealing with it…The minute somebody tells me “oh they weren't nice to me” I think…death by a thousand cuts.those everyday encounters….it’s those daily insults that people have to go through just to get something.

Examples included backhanded compliments, with one mother recounting teachers expressing surprise that her daughter was Chuukese, because she was "so clean" and "wasn't loud like the others." One Chuukese provider explained how these low expectations can be detrimental for a child:

A 12 year old kid from the islands is considered a man in the eyes of the community ‧ but then he comes here and the system is saying he is nobody, all of a sudden his maturity is taken away making him a weakling.

Several participants concluded that such damaging assumptions and differential treatment have had negative effects health. For example, a social worker shared the story of a young Chuukese male patient who was physically assaulted. Unjustly blamed for the incident and evicted from public housing, he felt “unsafe and depressed” because he was “targeted.” Others reported “police brutality” and security personnel physically assaulting Chuukese housing tenants. Chuukese children endured the similar profiling – being repeatedly bullied while the school did not respond to parental complaints. When the Chuukese students defended themselves they were suspended, leaving parents feeling “helpless and fed up, with some even pulling their children out of school.”

When discussing racial discrimination with patients, several providers felt discrimination was an appropriate word to use with the Chuukese community. One Chuukese provider stated, “Micronesians are very familiar with the word discrimination.” A non-Chuukese provider suggested that the longer migrants have been in the US, the more they disclosed "discrimination and feeling discriminated against, like…'why do they always attack us, why is our healthcare in jeopardy? Why don’t we have…parity with other groups?'"

However, during the interviews, few community participants used the word “discrimination.” Rather they reported, “being treated differently because they were Chuukese,” and that people were “not nice.” They described getting a “funny feeling inside,” often while gesturing to their heart. Several non-Chuukese providers at CHCs said it often took “work” to uncover stories of discrimination:

A majority of incidents that we hear… come as a side issue…underneath all of those encounters …then they’re finally like, “I think they treat Micronesian people differently. ”…I have to draw it out of them because…they don't want to say, “oh they treated me badly because they're racist.” They're never going to say that.

Providers attributed this hesitancy to disclose experiences with racial discrimination to mistrust of agencies, feelings of shame, and fear of repercussions. One community participant did not report a provider’s behavior because she was afraid that she would lose access to services, so she “just stopped talking.” Another deterrent is that some fear “bringing negative attention to their community. ”

Providers shared that, despite personal discomfort and risk, individuals are more likely to speak out if it will protect others. Often people are willing to “let it go” or think “I can handle it” if the incident affects only themselves. However, when children are involved, “parents are willing to stand up and say this is racism; it’s discrimination; it’s affecting my child’s well-being.”

Theme 3: Solutions - building on community assets

Participants shared many suggestions for solutions including changes to patient-provider relationships and altering facility protocols. Many providers at CHCs had incorporated Chuukese community assets into their practice. One therapist shared that, rather than utilizing individual psychotherapy methods, she now incorporates the whole family because Chuukese patients “always come as a community…[they have] a lot of protective factors from a mental health perspective…they’re usually very supported.” She added, “If you don’t talk about their spirituality in treatment, you’re totally missing the mark.”

Building upon the community’s connection to their culture is another avenue. A non-Chuukese provider explained, “Even in the face of all this adversity, they’re still very connected to who they are as people, their values, and what gives them meaning in life, and that they don’t falter from that.”

Theme 4: Solutions - building relationships

Some providers reported the importance of taking the time to build relationships, offer navigational services, and express empathy. One community member highlighted the importance of “really meeting each other and understanding each other. ” All CHC providers cited the value of learning a few Chuukese words to help people feel welcome and strengthen trusting relationships. One physician emphasized involvement in patients' lives outside the health center, including attending funerals and celebrations. Another provider explained, “I almost feel like I have to be that much more of an ambassador…to let them know we really do want you here, we really do want to support you.”

An interpreter echoed the importance of practitioners being compassionate:

I understand that everything has a deadline but please talk nice to them instead of pushing because that’s what just close[s] everything up…if I hear that the doctor or social worker demands something I try to say it in a nice word to the Chuukese… [because I know] they’d rather suffer than come into the office and get yelled at….They want to get help but they ’re afraid.

Others suggested incorporating Chuukese-specific teachings into cultural sensitivity trainings. Many providers are unprepared for the unique needs of this community. Individuals who want to know about Chuukese culture and history must educate themselves. One provider explained,

It’s such a learning curve you know … I wish I was told, here’s their history, here’s how they’re impacted by their transitional life in the US, here’s the symptoms that they usually present with because of these reasons, and here’s what we’ve found [to be] best approaches or best practices working with this population.

Theme 5: Solutions – changing social norms

Some CHCs have made changes to their infrastructure’s everyday practices, such as hiring on-site interpreters and adding providers to see walk-in patients to mitigate scheduling issues. Participants also supported the need to change how our society frames concepts of health, healthcare, and racial discrimination. A physician shared,

Should healthcare be viewed as a commodity, or should it be viewed as a social good, or should it be viewed as a human right. I think that for myself as a believer in health and healthcare as a human right, as a social good I try my best to… deliver healthcare with that in mind.

Another provider suggested that “we need to frame racism as a disease of the community, not of the individual.” She suggested that harnessing community discourse on discrimination “in a way that promotes fairness and equality can have the power to help change things,”

Discussion

This study elucidates the barriers to obtaining healthcare for Hawai‘i's Chuukese community and proposes possible solutions. Some barriers are ones faced by other minority groups and previously identified by Paradies et al.’s framework4 such a racial discrimination, while others were particular to the Chuukese community including targeted systematic denial of healthcare coverage and cultural beliefs that health issues are extremely private. Obstacles to care— whether related to language, culture, knowledge, or policy have led to fractured relationships. Participants described patients not understanding the healthcare system, providers not understanding Chuukese history and culture, and neither effectively communicating to each other. For many, this has led to confusion, frustration, and misunderstanding. Participants underscored how low health literacy, ineffective communication, cultural differences, and inequitable coverage resulted in damaged relationships, discriminatory stereotypes, lower standards of care, and in some cases, denial of service.

This study illustrated that racial discrimination permeates many aspects of Chuukese migrant life. The majority of providers inferred a connection between racial discrimination and negative health outcomes. Consistent with other studies, community participants were hesitant to divulge experiences of racial discrimination.18 Also, it was often difficult for participants to attribute unfair treatment to race—a phenomenon labeled attribution ambiguity.3,18 Providers who had discussed racial discrimination with patients suggested framing conversations in terms of experiences of their children and the community. Community liaisons observed that after the formal interview was over, most community participants would disclose additional experiences of discrimination. This may reflect non-confrontational cultural or religious precepts about not speaking negatively, avoiding the vulnerability and stigma of discrimination, not wanting to draw attention to the community, or fearing negative repercussions. Such findings supports the need for safe spaces where individuals can constructively discuss injustice and a culturally sensitive racial discrimination measurement tool to talk to the larger Chuukese community.28 Such a tool might utilize familiar terms and frame questions in collective rather than individual terms.

Many of suggestions offered to overcoming racial discrimination and providing a high standard of care to Chuukese patients are in line with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s (RWJF) roadmap and best practices for reducing racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare.29 Our participants touched upon most of the levels of interventions that RWJF suggests, including patient, provider, organizational, community, and policies.

The majority of participants’ suggestions spoke to changing how providers deliver care, how facilities are structured, and how society views healthcare and racial discrimination. Most solutions came down to building trust by incorporating Chuukese community assets into care provision, strengthening communication via interpreters, educating patients on navigating the healthcare system, and educating providers in the history and culture of the Chuukese. This is consistent with efforts to utilize Micronesian healthcare navigators,30 orienting patients to the healthcare system, and promoting “political education and community mobilization.”13,pg7 A systematic solution was to shift our society’s way of thinking about racial discrimination in healthcare, specifically by regarding healthcare as a human right rather than a commodity and addressing racial discrimination as a structural problem.

Limitations

The non-Chuukese interviewer’s presence may have made community participants uncomfortable – though steps were taken to minimize this. Another limitation was that the majority of community participants were women. Although this was expected because of the cultural norm of women representing family health issues, Chuukese men may have different experiences with discrimination. However, most providers recounted stories of discrimination pertinent to both genders.

Conclusion

Together these stories, from healthcare providers and community members paint a picture of not only a community facing many barriers to care, including racial discrimination, but one that has a clear vision for healing and reconciliation. To overcome harmful stereotypes, misinformation, mistaken assumptions, and indifference, many are working to build stronger patient-provider relationships, mutual understanding, and respect. This study highlights the importance of addressing racial discrimination, cultural beliefs, and community assets when working towards health and healthcare equity for the Chuukese. Lessons learned may be relevant for other Micronesian, Pacific Islander, and indigenous communities.

Footnotes

COI: None declared

Contributor Information

Megan Kiyomi Inada, Kokua Kalihi Valley Comprehensive Family Services 2239 North School Street, University of Hawai‘i Manoa, Office of Public Health Studies, 1960 East-West Road Honolulu, HI 96822.

Kathryn L. Braun, University of Hawai‘i Manoa, Office of Public Health Studies, 1960 East-West Road Honolulu, HI 96822.

Parkey Mwarike, College of Micronesia –FSM P.O. Box 879, Chuuk, FM 96942.

Kevin Cassel, University of Hawai‘i Cancer Center, 701 Ilalo Street Honolulu, HI 96822.

Randy Compton, Medical-Legal Partnership for Children in Hawai‘i, University of Hawai‘i, William S. Richardson School of Law, 2515 Dole Street, Honolulu, HI 96822.

Seiji Yamada, John A. Burns School of Medicine, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, 651 Ilalo St, Honolulu, HI 96813.

References

- 1.Marmot M Achieving Health Equity: From Root Causes to Fair Outcomes. The Lancet. 2007. 370(9593):1153–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weech-Maldonado R, Hall A, Bryant T, et al. The Relationship Between Perceived Discrimination and Patient Experiences with Healthcare. Medical care. 2012. 50(902):S62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. Journal of behavioral medicine. 2009. February 1;32(1): 20–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paradies Y, Priest N, Ben J. Racism as a determinant of health: A protocol for conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis. Systematic Reviews 2013. 2(85). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzales KL, Harding AK, Lambert WE, et al. Perceived Experiences of Discrimination in Healthcare: A Barrier for Cancer Screening Among American Indian Women with Type 2 Diabetes. Women's Health Issues. 2013. 23(1):e61–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorkin DH, Ngo-Metzger Q, De Alba I. Racial/ethnic Discrimination in Healthcare: Impact on Perceived Quality of Care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010. 25(5):390–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paradies Y A Systematic Review of Empirical Research on Self-reported Racism and Health. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006. 35(4):888–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS.Racial/ethnic Discrimination and Health: Findings from Community Studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003. 93(2):200–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Look MA, Trask-Batti MK, Agres R, et al. Assessment and priorities for health & well-being in Native Hawaiians & other Pacific peoples Center for Native and Pacific Health Disparities Research. Honolulu HI: University of Hawai’i; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riklon S, Alik W, Hixon A, et al. The ‘Compact Impact; in Hawai‘i: Focus on Healthcare. Hawai‘i Medical Journal. 2010. 7:7–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palafox NA, Riklon S, Esah S, et al. 2012. “The Micronesians” In People and Cultures of Hawai‘i ; the Evolution of Culture and Ethnicity, edited by McDermott JF, Naupaka N; Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shek D, Yamada S. Health care for Micronesians and constitutional rights. Hawaii Medical Journal. 2011. November;70(11 Suppl 2):4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacNaughton NS, Jones ML. Health Concerns of Micronesian Peoples. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2013. 1043659613481675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagiwara MK, Miyamura J, Yamada S, et al. Younger and Sicker: Comparing Micronesians to Other Ethnicities in Hawaii. American journal of public health. 2016. February(0):e1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blair C No aloha for micronesians in Hawaii Honolulu Civil Beat.[Internet] 2011. June 20 [cited 2016 March 10] Avaliable from: http://www.civilbeat.-com/articles/2011/06/20/11650-no-aloha-for-micronesians-in-Hawaii [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamada S Discrimination in Hawai‘i and the health of Micronesians and Marshallese. Hawaii J Public Health. 2011. 3(1):55–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saunders A, Schiff T, Rieth K, et al. Health as a Human Right: Who is Eligible. Hawaii Med J. 2010. Jun; 69:4–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bastos JL, Celeste RK, Faerstein E, et al. Racial discrimination and health: a systematic review of scales with a focus on their psychometric properties. Social science & medicine. 2010. April 30;70(7): 1091–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Podsiadlowski A, Fox S. Collectivist Value Orientations Among Four Ethnic Groups: Collectivism in the New Zealand Context. New Zealand Journal of Psychology. 2011. 40(1):5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maxwell JA. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods (3nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez DF, Nie JX, Ardern CI, et al. Impact of Participant Incentives and Direct and Snowball Sampling on Survey Response Rate in an Ethnically Diverse Community: Results from a Pilot Study of Physical Activity and the Built Environment. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2013. 15(1):207–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi JY. Seeking Healthcare: Marshallese Migrants in Hawai‘i. Ethnicity and Health. 2008. 13(1):73–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pobutsky AM, Krupitsky D, Yamada S. Micronesian Migrant Health Issues in Hawai‘i: Part 2: An assessment of Health, Language and Key Social Determinants of Health. Californian Journal of Health Promotion. 2009. 7(2):32–55. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mellor D Responses to Racism: A Taxonomy of Coping Styles Used by Aboriginal Australians. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2004. 74(1):56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MicSem Monthly Discussion Topic. Women's Role in Micronesia: Then and Now #6 March 8, 1994. http://www.mic-sem.org/pubs/conferences/frames/wom-tradfr.htm [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, et al. Using the Framework Method for the Analysis of Qualitative Data in Multidisciplinary Health Research. BMC medical Research Methodology. 2013. 13(1): 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gee GC, Ro A, Shariff-Marco S, Chae D. Racial Discrimination and Health Among Asian Americans: Evidence, Assessment, and Directions for Future Research. Epidemiologic reviews. 2009. 31(1): 130–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chin MH, Marshall H., Nocon R, et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Internal Med. 2010. 27(8):922–1000. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aitaoto N, Braun KL, Estrella J, et al. Design and results of a culturally tailored cancer outreach project by and for Micronesian women. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012. 9:100262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]