Abstract

An understanding of organic chemistry can play a central role in uncovering enzymes with new biochemical functions. We have recently identified the enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of the cylindrocyclophanes, a structurally unique family of natural products, and found that this pathway employs a remarkable macrocyclization event that requires functionalization of an unactivated carbon atom. This work illustrates the potential of using chemically guided approaches for enzyme discovery.

Keywords: Biosynthesis, cylindrocyclophanes, natural products, enzymes, genomics

Graphical Abstract:

Enzymes, Nature’s tools for complex molecule synthesis, have long been a source of inspiration for chemists. Over billions of years enzymes have evolved to efficiently generate stunningly complex natural products. Enzymes can also catalyze chemical transformations that are challenging for synthetic chemists with superb selectivity and specificity. Mechanistic understanding of enzymatic function has led to developments in synthetic methodology,1 and reactions and disconnections that emulate biosynthesis have also been employed by chemists in the context of total syntheses.2 In addition, there has been growing interest in utilizing enzymes as tools for synthesis. Biocatalytic approaches are increasingly employed in drug and fine chemical synthesis as more efficient and environmentally friendly alternatives to traditional methods.4

Microorganisms are a rich source of new enzymatic chemistry, as many medicinally and industrially important natural products are microbial in origin. These molecules are made by dedicated sets of enzymes that are typically encoded by genes that are grouped within microbial genomes into biosynthetic gene clusters. Recent advances in DNA sequencing technology have facilitated rapid, low-cost microbial genome sequencing; sequencing the first microbial genome in 1995 took over a year and cost $2 million, while today a genome can be obtained in days for a few thousand dollars.5 The bioinformatic tools used to analyze DNA sequencing data and identify genes have also become more sophisticated.6 Together these developments could fundamentally change how chemists discover new tools for synthesis by providing access to a vast pool of enzyme sequences. However, a major roadblock in reaching this goal is a means of efficiently identifying enzymes most likely to possess new and desirable biochemical functions. Predicting the function of an enzyme discovered in sequencing data is normally accomplished by comparing its gene sequence to genes whose products have already been characterized. This reliance on similarity to existing enzymes is problematic for discovering new chemistry because a truly novel enzyme may have no close homologs. Moreover, less than 1% of annotated microbial genes have actually been experimentally characterized.7 Our ability to discover new enzymatic chemistry from DNA sequencing data is therefore limited.

We believe that insights and approaches from organic chemistry can play a critical role in surmounting this obstacle by helping to both link sequencing data with biological function as well as identify pathways most likely to involve novel reactivity. Our research harnesses the power of chemical knowledge to discover, understand, and manipulate microbial metabolic pathways and enzymes (Scheme 1). An understanding of chemical structure and reactivity principles helps generate biochemical hypotheses that can guide bioinformatic searches for gene clusters in microbial genome sequencing data. Chemical knowledge can also guide experiments to probe the biochemical roles of gene clusters linked to important functions. These gene clusters can encode pathways of interest from both primary and secondary metabolism. In the context of secondary metabolism, our focus is on elucidating the biosynthetic pathways that produce molecules with unique structural features that are likely to be assembled using new enzymatic chemistry. We have recently identified the biosynthetic pathway responsible for constructing the cylindrocyclophanes, a family of architecturally complex natural products.8 Our studies of this pathway have already revealed an unusual enzymatic assembly line and may uncover new strategies for C–C bond formation.

Scheme 1.

Chemically guided approaches for discovering and understanding biological function in microbial genome sequencing data.

The cylindrocyclophanes were isolated in the early 1990s from the cyanobacterium Cylindrospermum licheniforme Kützing and were the first naturally-occurring paracyclophanes to be discovered (Scheme 2A).9 The unique macrocyclic architecture of these natural products has made them popular targets for total synthesis and inspired organic chemists to develop multiple unique strategies for assembling the central paracyclophane scaffold (Scheme 2B). Smith and co-workers employed an elegant tandem cross metathesis/ring-closing metathesis macrocyclization strategy in their syntheses of (−)-cylindrocyclophanes A and F.10 This approach was also employed by the Iwabuchi group.11 Hoye and co-workers constructed cylindrocyclophane A using a double Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons macrocyclization.12 Most recently, Nicolaou and co-workers utilized an SN2 substitution for macrocycle construction followed by a Ramberg-Bäcklund reaction to generate both (–)-cylindrocyclophanes A and F13 Although the synthetic challenge presented by these natural products has produced multiple innovative syntheses, remarkably no approach to date has assembled the paracyclophane macrocycle using the disconnection postulated to be operative in cylindrocyclophane biosynthesis.

Scheme 2.

Isolation and total syntheses of the cylindrocyclophanes. A. Structures of the cylindrocyclophanes isolated from C. licheniforme. B. Strategies employed in previous cylindrocyclophane total syntheses.

Bobzin and Moore put forth the first biosynthetic hypothesis for cylindrocyclophane assembly in 1993.14 Feeding experiments using isotopically labeled sodium acetate revealed that these natural products are of polyketide origin. The highly symmetric nature of the isotopic labeling pattern observed in these studies suggested that biosynthesis involved head-to-tail dimerization of a monomeric precursor (Scheme 3). Bobzin and Moore postulated that this extremely unusual C–C bond formation would proceed via an intermediate bearing two pre-functionalized sp2 carbon centers. Recognizing that such a transformation had little precedent in biochemistry, we decided to search for the cylindrocyclophane biosynthetic pathway using a chemically guided genome mining approach. By discovering and studying the enzymatic chemistry involved in constructing these unusual molecules, we hoped to uncover the potentially new chemistry Nature has evolved for stereo- and regioselective construction of the [7.7]paracyclophane framework.

Scheme 3.

Previous studies of cylindrocyclophane biosynthesis by Bobzin and Moore. A. Feeding experiments with isotopically labeled sodium acetate reveal the polyketide origin of the natural products. B. Biosynthetic hypothesis for macrocycle formation.

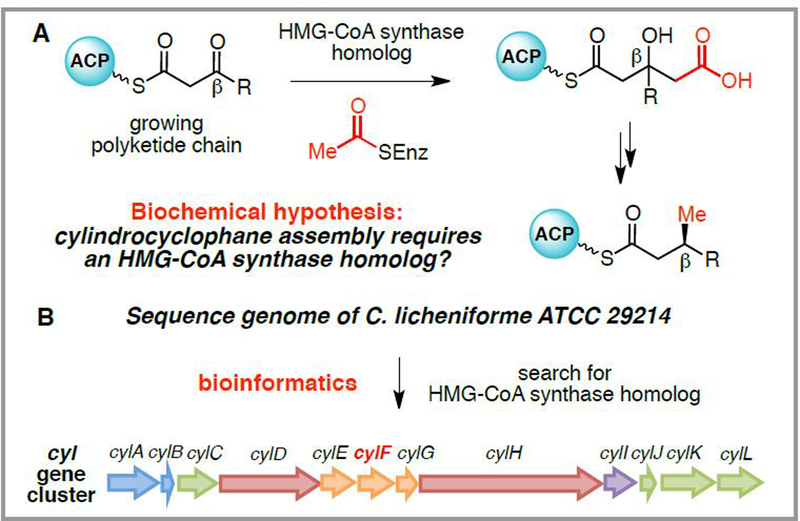

Our strategy for identifying the cylindrocyclophane biosynthetic enzymes required access to genome sequencing data from the producing organism and a biochemical hypothesis for the enzymatic reactions used in natural product assembly. The recent drop in the cost of DNA sequencing has allowed individual labs to independently sequence the genomes of their own organisms of interest, which was the approach we used for the cylindrocyclophane-producing cyanobacterium C. licheniforme ATCC 29412. With genome sequencing data in hand, we then searched for candidate biosynthetic gene clusters based on the presence of genes with predicted biochemical functions consistent with a potential role in cylindrocyclophane assembly. Namely, the results of the original feeding studies led us to hypothesize that biosynthesis should involve a hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) synthase homolog that installs acetate-derived β-methyl substituents onto polyketide scaffolds (Scheme 4A).15 Using this approach, we discovered a candidate cylindrocyclophane (cyl) biosynthetic gene cluster that contained not only an HMG-CoA synthase homolog (cylF) but also other genes, such as polyketide synthases (PKSs), whose predicted functions were consistent with this biosynthetic pathway (Scheme 4B). Thus, a chemical understanding of how a methyl group should be added to these natural products shaped a hypothesis that led to identification of additional biosynthetic machinery.

Scheme 4.

Identification of the cylindrocyclophane biosynthetic pathway A. HMG-CoA synthase homologs install β-methyl substituents onto polyketide scaffolds. B. Strategy for identifying the cylindrocyclophane (cyl) biosynthetic gene cluster in C. licheniforme genome sequencing data.

Detailed bioinformatic analysis of our putative cyl gene cluster allowed us to formulate a more detailed biosynthetic hypothesis for cylindrocyclophane assembly (Scheme 5). This analysis is facilitated by extensive knowledge of the biosynthetic logic underlying assembly line enzymes. Since the discovery of the first type I modular polyketide synthase 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase (DEBS) in the early 1990s,16 a large body of research has deciphered the roles of individual PKS domains and modules.17 This knowledge makes it possible to predict the structure generated by a type I PKS by analyzing the sequences of the assembly line enzymes. The type I PKS assembly line of the cyl cluster is unexpectedly short in length, and its abbreviated nature indicated that it might be initiated and terminated in an unusual manner. We hypothesize that biosynthesis begins with decanoic acid, which is activated as a thioester (7) and loaded onto the first PKS CylD. Chain elongation by CylD is followed by installation of the β-methyl substituent by three enzymes, including the HMG-CoA synthase homolog CylF. A second type I PKS CylH then elongates the carbon chain to form acyl carrier protein (ACP)-bound thioester 8. This intermediate is then removed from the assembly line by type III PKS Cyll, which terminates the PKS assembly line by catalyzing aromatic ring formation and generating resorcinol 9. This metabolite is a candidate monomeric precursor for the cylindrocyclophane macrocyclic scaffold and could be elaborated to the final natural product through a series of tailoring events.

Scheme 5.

Biosynthetic hypothesis for cylindrocyclophane assembly.

Our strategy for verifying the connection between the cyl gene cluster and cylindrocyclophane production involved examining the activities of enzymes predicted to perform distinctive roles in biosynthesis. We began by analyzing the enzymes likely to initiate and terminate the type I PKS assembly line. We hypothesized that initiation could involve acyl adenylating enzyme, CylA, which would use ATP to activate free decanoic acid and load it onto the phosphopantethienyl (ppant) ann of free-standing ACP CylB for transfer to the assembly line. Use of free fatty acid as a starter unit has limited precedence among type I modular PKS assembly lines.18 We confirmed the activities of CylA and CylB in vitro and discovered a striking preference for activation of decanoic acid over alternate fatty acid substrates (Scheme 6A). With the roles of the initiating enzymes defined, we then examined assembly line termination. Typically, type I PKSs are terminated by the action of a thioesterase (TE) domain, which catalyzes thioester hydrolysis or macrolactonization. Although CylH contained a TE domain, we postulated that a more unusual termination event might be operative in the cylindrocyclophane PKS assembly line: aromatic ring formation by type III PKS Cyll. Type III PKSs typically catalyze aromatic ring formation using a series of Claisen condensations. We anticipated that Cyll might terminate the assembly line by converting CylH-bound intermediate 8 into alkyl resorcinol 9.

Scheme 6.

The in vitro activities of the cyl enzymes support their involvement in cylindrocyclophane production A. Biochemical characterizations of fatty acid activating enzymes CylA and CylB. B. Biochemical characterization of type III PKS Cyll. C. Proposed mechanism for Cyll-catalyzed formation of resorcinol 9.

While a few type III PKSs accept acyl-ACP substrates bound to iterative type I19 and type II20 fatty acid synthases, a type III PKS capable of terminating a modular type I PKS had not been previously reported. We tested the activity of Cyll using a synthetic mimic of its putative ACP-bound substrate and found that it generated the anticipated resorcinol product (Scheme 6B). The mechanism of this transformation likely involves two decarboxylative Claisen condensations, followed by cyclization, thioester hydrolysis, and aromatization (Scheme 6C). Overall, the in vitro characterization of CylA, CylB and Cyll verified that these enzymes have functions consistent with our biosynthetic hypothesis, strongly supporting involvement of the cyl cluster in cylindrocyclophane assembly.

Our initial in vitro experiments did not directly examine formation of the paracyclophane scaffold. We obtained further insights into the construction of this unusual structural motif using in vivo feeding experiments. Feeding labeled versions of potential biosynthetic precursors or intermediates to producing organisms can be a powerful approach for investigating natural product biosynthesis. We probed the origin of the cylindrocyclophane macrocycle’s saturated carbon backbone by feeding d19-decanoic acid to C. licheniforme ATCC 29412. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis of organic cell extracts from fed cultures revealed both the formation of d18- and d36-cylindrocyclophane F (Scheme 7). This result confirmed that decanoic acid is a precursor to the cylindrocyclophanes and indicated that biosynthesis must therefore involve functionalization of an unactivated C–H bond. Incorporation of d19-decanoic acid with a loss of only one deuterium also rules out the possibility of prefunctionalization as a ketone or alkene and supports a biosynthetic disconnection in which the C–C bond formation occurs between sp2 and sp3 carbon centers. Interestingly, the relative abundance of the double incorporation product d36-cylindrocyclophane F was greater than the single incorporation product. This observation suggests that complex enzyme interactions may take place to tightly couple formation of monomeric precursor and dimerization.

Scheme 7.

Feeding d19-decanoic acid to C. licheniforme ATCC 29412 confirms its role as a biosynthetic precursor.

Future work on this pathway will be directed toward understanding the enzymatic chemistry underlying this unusual C–C bond formation, which we now know requires functionalization of an unactivated carbon center. We envision that this oxidative functionalization could occur either concomitant with or prior to C–C bond formation (Scheme 8A). The most commonly used strategies for C–C bond formations in biology, Aldol, Claisen, and Michael-type reactions, involve carbonyl chemistry.21 Direct enzymatic oxidative alkylations are rare; enzymes capable of functionalizing unactivated C–H bonds, including diiron enzymes22,23 and α-ketoglutarate-dependent hydroxylases24 and halogenases,25 typically promote alternate transformations. Recent reports have described the first enzymes that catalyze direct sp2–sp3 C–C bond formation at unfunctionalized carbon centers. A diiron enzyme capable of crosslinking the side chains of active site phenylalanine and valine residues was characterized in vitro26 Rieske oxygenase homologs RedG and McpG have also been shown to catalyze C–C bond formation in streptorubin B and metacycloprodigiosin biosynthesis in vivo (Scheme 8B).27 While the possible direct oxidative alkylation in cylindrocyclophane biosynthesis may be conceptually related to these transformations, there is an additional complexity of intermolecular dimerization and macrocyclization. Biochemical characterizations and mechanistic studies of the C–C bond forming enzymes in cylindrocyclophane biosynthesis are therefore warranted, and we hypothesize that one or more of the remaining enzymes encoded by the cyl cluster may be involved in this transformation.

Scheme 8.

Understanding the macrocyclization event in cylindrocyclophane biosynthesis. A. Possible biosynthetic logic employed in macrocyclization. B. Potentially related direct oxidative C–C bond formations.

Our initial studies of cylindrocyclophane biosynthesis have provided the first insights into the enzymatic chemistry used to construct a unique [7.7]paracyclophane scaffold. We believe that targeting natural products with unusual molecular architectures for biosynthetic studies will be a powerful approach for discovering new enzymatic transformations. With recent advances in microbial genome sequencing and bioinformatics affording an unprecedented opportunity to understand microbial metabolism, scientists have never been better positioned to interrogate the biological world for new chemistry. Organic chemistry will certainly play a critical role in the success of these endeavors.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge financial support from Harvard University, the Corning Foundation, and the Searle Scholars Program. H.N. acknowledges fellowship support from the NIH (GM095450) and the Herchel Smith Fellowship program.

Biography

Hitomi Nakamura received her B.S. degree in chemistry in 2010 from the University of California, Berkeley where she worked under the mentorship of Prof. Carolyn R. Bertozzi. Currently she is pursuing a Ph.D. at Harvard University under the guidance of Prof. Balskus.

Emily Balskus received her B. A. in chemistry from Williams College in 2002. After spending a year at the University of Cambridge as a Churchill Scholar in the lab of Prof. Steven V. Ley, she pursued graduate studies with Prof. Eric N. Jacobsen in the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology (CCB) at Harvard University and received her Ph.D. in 2008. From 2008–2011 she was an NIH postdoctoral fellow at Harvard Medical School in the lab of Prof. Christopher T. Walsh. In 2011 Emily returned to CCB as an Assistant Professor. Her research focuses on the discovery of new biosynthetic pathways and enzymes from microorganisms and the development of new approaches for using microorganisms in chemical synthesis.

References

- (1).Wender PA; Miller BL Nature. 2009, 460, 197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) De la Torre MC; Sierra MA Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 160. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bulger PG; Bagal SK; Marquez R Nat. Prod. Rep. 2008, 25, 254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Weeks AM; Chang MCY . Biochemistry 2011, 50, 5404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Koeller KM; Wong C-H Nature 2001, 409, 232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Cruz J; Liu Y; Liang Y; Zhou Y; Wilson M; Dennis JJ; Stothard P; Van Domselaar G; Wishart DS Nucl. Acid. Res. 2012, 40, D599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).(a) Bansal AK Microb. Cell. Fact. 2005, 4, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Challis GL Microbiology 2008, 154, 1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Erdin S; Lisewski AM; Lichtarge O Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2011, 21, 180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Nakamura H; Hamer HA; Sirasani G; Balskus EP J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 18518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).(a) Moore BS; Chen JL; Patterson GML; Moore RE; Brinen LS; Kato Y; Clardy J J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 4061. [Google Scholar]; (b) Moore BS; Chen JL; Patterson GML; Moore RE Tetrahedron 1992, 48, 3001. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Smith AB; Adams CM; Kozmin SA; Paone DV J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 5925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Yamakoshi H; Ikarashi F; Minami M; Shibuya M; Sugahara T; Kanoh N; Ohori H; Shibata H; Iwabuchi Y Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 3772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Hoye TR; Humpal PE; Moon BJ Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 4982. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Nicolaou KC; Sun YP ; Korman H.; Sarlah D Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 5875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Bobzin SC; Moore RE Tetrahedron 1993, 49, 7615. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Calderone CT Nat. Prod. Rep. 2008, 25, 845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).(a) Cortes J; Haydock SF; Roberts GA; Bevitt DJ; Leadlay PF Nature 1990, 348, 176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Donadio S; Staver MJ; McAlpine JB; Swanson SJ; Katz L Science 1991, 252, 675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).(a) Hertweck C Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 4688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Walsh CT; Fischbach MA J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).(a) Trivedi OA; Arora P; Sridharan V; Tickoo R; Mohanty D; Rajesh S; Gokhale RS Nature 2004, 428, 441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Arora P; Goyal A; Natarajan VT; Rajakumara E; Verma P; Gupta R; Yousuf M; Trivedi OA; Mohanty D; Tyagi A; Sankaranarayanan R; Gokhale RS Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).(a) Austin MB; Saito T; Bowman ME; Haydock S; Kato A; Moore BS; Kay RR; Noel JP Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006, 2, 494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Miyanaga A; Funa N; Awakawa T; Horinouchi S Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).(a) Song L; Barona-Gomez F; Corre C; Xiang L; Udwarry DW; Austin MB; Noel JP ; Moore BS; Challis GL J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 14754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chemler JA; Buchholz TJ; Geders TW; Akey DL; Rath CM; Chlipala GE; Smith JL; Sherman DH J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 7359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nakano C; Ozawa H; Akunuma G; Funa N; Horinouchi SJ Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 4916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Fessner W-D Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1998, 2, 85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Merkx M; Kopp DA; Sazinsky MH; Blazyk JL; Müller J; Lippard SJ Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Shanklin J; Cahoon EB Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1998, 49, 611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Hausinger RP Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. 2004, 39, 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Vaillancourt FH; Yeh E; Vosburg DA; Tsodikove SG; Walsh CT Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 3364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Cooley RB; Rhoads TW; Arp DJ; Karplus PA . Science 2011, 332, 929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Syndor PK; Barry SM; Odulate OM; Barona-Gomez F; Haynes SW; Corre C; Song L; Challis GL Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]