Abstract

Background

We conducted a longitudinal study to evaluate changes in the clinical presentation and epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) in an academic, US medical center.

Methods

Consecutive patients with monomicrobial SAB were enrolled from January 1995 to December 2015. Each person’s initial bloodstream S. aureus isolate was genotyped using spa typing. Clonal complexes (CCs) were assigned using Ridom StaphType software. Changes over time in both the patient and bacterial characteristics were estimated with linear regression. Associations between genotypes or clinical characteristics and complications were estimated using multivariable regression models.

Results

Among the 2348 eligible participants, 54.2% had an implantable, foreign body of some type. This proportion increased significantly during the 21-year study period, by 0.96% annually (P = .002), as did comorbid conditions and acquisition outside of the hospital. Rates of any metastatic complication also significantly increased, by 0.94% annually (P = .019). Among the corresponding bloodstream S. aureus isolates, spa-CC012 (multi-locus sequence type [MLST] CC30), -CC004 (MLST CC45), -CC189 (MLST CC1), and -CC084 (MLST CC15) all significantly declined during the study period, while spa-CC008 (MLST CC8) significantly increased. Patients with SAB due to spa-CC008 were significantly more likely to develop metastatic complications in general, and abscesses, septic emboli, and persistent bacteremia in particular. After adjusting for demographic, racial, and clinical variables, the USA300 variant of spa-CC008 was independently associated with metastatic complications (odds ratio 1.42; 95% confidence interval 1.02–1.99).

Conclusions

Systematic approaches for monitoring complications of SAB and genotyping the corresponding bloodstream isolates will help identify the emergence of hypervirulent clones and likely improve clinical management of this syndrome.

Keywords: USA300, spa-CC008, spa typing, MRSA, clonal complex

During 21 years of continuous enrollment in this prospective, observational cohort study of 2348 patients, bacterial genotypes, patient characteristics, and metastatic complication rates changed significantly. The emergence of the USA300 genotype was independently associated with an increase in metastatic complications.

(See the Editorial Commentary by David on pages 1878–80.)

Although clinicians have considered the syndrome of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (SAB) to be fundamentally similar over time, a number of observations now bring this assumption into question. First, multiple studies have drawn associations between specific bacterial genotypes and an increased risk for various forms of infectious complications [1–5]. Next, several bacterial clones and types, such as USA400, USA300, Sequence Type (ST) 93, and phage type 80/81, are distinct for their virulence and ability to cause specific forms of infection. Each of these inexplicably emerged, dominated, and ultimately diminished in their frequency [6–9].

The present study used a longitudinal design to test the central hypothesis that temporal shifts in patient characteristics and in the genotype of S. aureus bloodstream isolates are associated with changes in the clinical presentation and severity of SAB. The study was possible because we have prospectively enrolled all eligible patients with SAB and genotyped the corresponding bloodstream bacterial isolates in our institution for more than 20 years.

METHODS

Study Population

The S. aureus Bacteremia Group Prospective Cohort Study (SABG-PCS) prospectively enrolled all eligible adult, hospitalized, non-neutropenic patients with monomicrobial SAB at Duke University Medical Center from 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2015. Duke University Medical Center is a tertiary-care referral center providing health-care services for North Carolina.

Patients were excluded from the study if they were: <18 years of age; neutropenic (defined as an absolute neutrophil count ≤1 × 109/L); not admitted to the hospital; previously enrolled for another SAB episode; had no signs or symptoms of infection; an additional clinically significant bacterial pathogen was isolated from their blood culture; or they declined informed consent. Within the SABG-PCS cohort, only patients whose initial bloodstream S. aureus isolate was viable and available for further testing met the inclusion criteria for the present study and were further analyzed.

Only the initial presentation for eligible patients was included in the study. Clinical data were collected on a standardized case report form and entered into an electronic database (Microsoft Access), including demographics; past medical history; history of surgery within the previous 30 days; site of acquisition of SAB; follow-up blood culture results; initial source of SAB; Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score [10], calculated on the day of the index positive blood culture; metastatic complications; and outcome at 90 days. The outcomes of SAB, per study protocol, recorded deaths (attributable to S. aureus or other causes), cures, or recurrent bacteremia within the 90-day follow-up period.

The study was approved by the Duke Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from patients or their legal representatives. If a patient expired prior to the notification of their blood culture results, the subjects were included using an Institutional Review Board–approved Notification of Decedent Research.

Definitions

Instances of SAB were categorized either as hospital- or community-acquired, according to criteria previously defined [11]. The latter category was further delineated as either community-acquired, healthcare–associated (CA-HCA) or community-acquired, nonhealthcare associated (CA-NHCA) [11].

A metastatic infection was defined as a site of S. aureus infection resulting from the spread from an initial site (via bloodstream seeding or direct extension). Patients were considered to have metastatic infections if they developed any of the following conditions: infective endocarditis, vertebral osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, septic emboli, septic thrombophlebitis, a metastatic abscess, or another deep tissue abscess (ie, epidural or psoas abscess). Distinguishing a metastatic infection from the source of SAB is often difficult, and was out of the scope of this study.

Clinical diagnoses for endovascular, osteoarticular, pulmonary, or other metastatic sites of S. aureus infections were based on clinical findings and laboratory, microbiology, radiology, or pathology data. Infective endocarditis was diagnosed according to the modified Duke criteria [12]. Persistent bacteremia was defined as ≥5 days of positive blood cultures after an appropriate treatment was initiated. Appropriate antimicrobial therapy was defined as therapy that included at least 1 antimicrobial, active in vitro against the SAB isolate. Recurrent SAB was defined as another episode of SAB within the 90-day follow-up period, after the resolution of the first episode.

Laboratory Studies

The identification and methicillin susceptibility testing are described in the Supplementary Material.

Molecular Typing

The initial bloodstream S. aureus isolate from each eligible patient underwent spa typing using an in-house, high-throughput, DNA isolation method (Supplementary Material) and polymerase chain reaction for the spa gene, with specific primers [13].

The assignment of spa types was performed using Ridom StaphType (Ridom GmbH, Würzburg, Germany). The spa types were clustered into spa Clonal Complexes (spa-CCs) using the based upon repeat pattern algorithm, at a cost setting of ≤4 and excluding spa types with <5 repeats. Genotypic characterization was repeated using the eGenomics software (http://tools.egenomics.com/spaTypeTool.aspx). Throughout this manuscript, the spa-CC nomenclature will be accompanied by the corresponding multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) CC nomenclature, for easy reference.

Isolates that failed to produce amplicons twice or that produced amplicons of such low quality that reading was unreliable were characterized as nontypeable for the statistical analysis.

Confirmation of USA300 Genotype

All isolates assigned to spa-CC008 (MLST CC8) were analyzed for the presence of both Panton-Valentine Leukocidin (PVL)- and Arginine Catabolic Mobile Element (ACME)-encoding genes [14]. For the statistical analysis, isolates that were methicillin resistant, PVL positive, and ACME positive and belonged to spa-CC008 (MLST CC8) were characterized as consistent with the USA300 type [15–17].

Statistical Analysis

Each variable for demographics, patient clinical characteristics, spa-CC, and USA300 was summarized using descriptive statistics and calculated separately for each calendar year and overall. An additional analysis further stratified the spa-CC by methicillin resistance. Frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables and medians and quartiles were generated for continuous measures. Plots of proportions by calendar year present these data for the clinical measures and bacterial genotypic characteristics. To test for secular trends in these parameters, linear regression models were fit for the calendar year means and proportions, with year as the independent variable. Multivariable logistic regression models assessed the associations of clinical characteristics and genotypes with any metastatic complications and abscesses, embolizations, and persistent bacteremia separately. Analyses were performed with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Spotfire SPlus 8.1 (TIBCO, Palo Alto, CA).

Clinical Ascertainment Bias

To examine whether any apparent increases in the rates of metastatic infections were due to an increasing use of imaging studies during the study period, we compared rates of use of imaging studies in a randomly selected 10% subgroup of study patients for each year, from 1995 to 2015 (Supplementary Material).

RESULTS

Study Population

Between 1995 and 2015, 2423 unique patients were enrolled in SABG-PCS. We excluded 53 from the study because the initial bloodstream isolate could not be retrieved. Another 22 were excluded from the analysis due to inconsistent data in the outcome variable. A mean of 112 eligible patients were enrolled per year (range, 72–135 patients). The annual distribution of the 2348 eligible patients is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

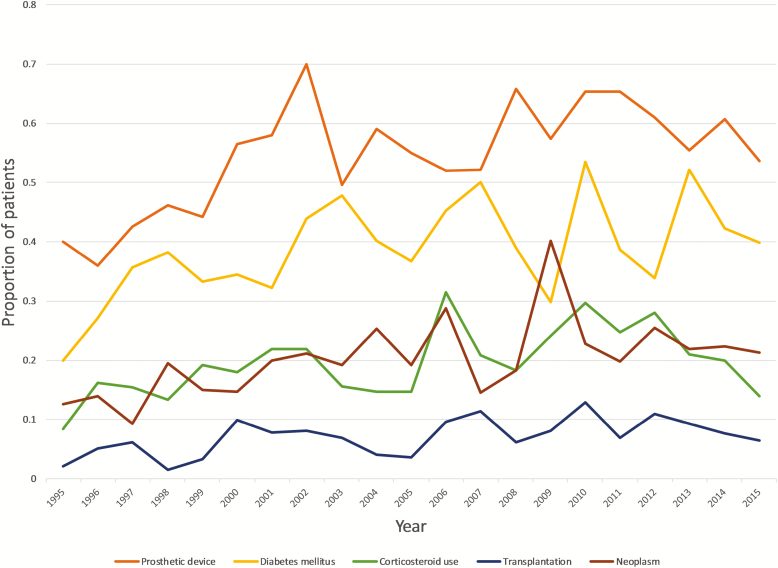

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. The median age of patients was 60 years, 56.6% were male, and 61% were Caucasian. The most common comorbidities were diabetes mellitus (38.6%), end-stage renal disease (ESRD; 21.1%), malignancy (hematologic or solid tumor; 19.8 %), and recent corticosteroid treatment (19.4%). The study cohort exhibited significant trends during the study period, including increases in rates of diabetes (annual increase 0.7%; P = .017), malignancy (0.6%; P = .012), transplantation (0.3%; P = .015), corticosteroid use (0.5%; P = .032), and rheumatoid arthritis (0.1%; P = .03) and decreases in rates of hemodialysis dependence (annual decline 0.5%; P = .023). The majority of patients (1273; 54.2%) carried some type of implantable device, such as a central vascular catheter, cardiac device, vascular graft, or orthopedic implant. The rate of patients with an implantable foreign body increased significantly, from 40% in 1995 to 54.7% in 2015 (P = .002; Figure 1). This increase was mainly driven by an increase in the use of cardiac devices and orthopedic implants. Patients with prosthetic devices were more likely to develop persistent SAB (P = .0002).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of 2348 Patients With Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia Enrolled in the Study

| Characteristica | Number of Patients (%)b | Annual Change (%)c | P Valued |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, median/IQR1-3 | 60/47–70 | 0.13e | .05 |

| Male gender | 1330 (56.6) | 0.36 | .084 |

| Race | |||

| White | 1422 (61) | 0.44 | .006 |

| African American | 846 (36.2) | −0.43 | .014 |

| Otherf | 65 (2.8) | −0.008 | .909 |

| Site of acquisition | |||

| Community-acquired nonhealthcare–associated | 228 (9.7) | 0.55 | <.0001 |

| Community-acquired healthcare–associated | 1390 (59.2) | 1.40 | <.0001 |

| Hospital-acquired | 729 (31.1) | −1.94 | <.0001 |

| Medical history | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 905 (38.6) | 0.70 | .017 |

| Dialysis dependence | 495 (21.1) | −0.47 | .023 |

| Injection drug use | 99 (4.2) | −0.03 | .587 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 60 (2.6) | 0.13 | .03 |

| Previous endocarditis | 73 (3.1) | 0.25 | .033 |

| Neoplasm | 464 (19.8) | 0.57 | .012 |

| Corticosteroid use (past 30 days) | 455 (19.4) | 0.45 | .032 |

| Transplantation | 164 (7.0) | 0.25 | .015 |

| HIV/AIDS | 70 (3.0) | −0.12 | .15 |

| Surgery (past 30 days) | 641 (27.4) | −0.52 | .032 |

| Presence of implantable foreign bodyg | |||

| Any type | 1273 (54.2) | 0.96 | .002 |

| Central vascular catheter (any type) | 571 (24.3) | 0.15 | .559 |

| Vascular graft | 219 (9.3) | −0.13 | .377 |

| Cardiac deviceh | 567 (24.2) | 0.84 | .004 |

| Orthopedic implant | 241 (10.3) | 0.54 | .001 |

| Otheri | 164 (7.0) | −0.08 | .707 |

| Central line–associated bacteremia | 619 (26.4) | −1.10 | <.0001 |

| Severity of disease | |||

| APACHE II scorej (median/IQR1-3) | 15/11–19 | 0.09k | .146 |

| CHPSl | |||

| 0 | 360 (15.3) | −0.26 | .502 |

| 2 | 474 (20.2) | −0.52 | .05 |

| 5 | 1514 (64.5) | 0.78 | .08 |

| Outcome in 90 days | |||

| Cure | 1518 (64.7) | −0.09 | .649 |

| Recurrent SAB | 197 (8.4) | −0.16 | .22 |

| Death (crude mortality) | 622 (26.5) | 0.26 | .166 |

| Death due to S. aureus (attributable mortality) | 317 (13.5) | 0.26 | .142 |

| Complicationsm | |||

| Persistent bacteremian | 518 (22.1) | 0.49 | .022 |

| Any metastatic infection | 860 (36.7) | 0.94 | .019 |

| Endocarditis | 320 (13.7) | 0.45 | .049 |

| Abscess (other than the types below) | 197 (8.4) | 0.40 | .004 |

| Psoas abscess | 47 (2.0) | 0.05 | .272 |

| Epidural abscess | 69 (2.9) | 0.20 | .004 |

| Septic emboli | 138 (5.9) | 0.62 | <.0001 |

| Vertebral osteomyelitis | 105 (4.5) | 0.30 | .002 |

| Septic arthritis | 163 (7.0) | 0.17 | .154 |

| Septic thrombophlebitis | 96 (4.1) | 0.20 | .044 |

| Meningitis | 20 (0.9) | −0.08 | .087 |

| Other metastatic infectiono | 108 (4.6) | 0.21 | .144 |

Abbreviations: APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; CHPS, Chronic Health Point Score; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IQR, interquartile range; max, maximum; min, minimum; S. aureus, Staphylococcus aureus; SAB, S. aureus bacteremia.

aSome entries have missing observations (see Supplementary Table 1 for details).

bUnless otherwise specified.

cA decrease is designated with a minus sign.

dSignificant values are shown in bold.

eChange in age of participants, annually.

fIncludes Hispanic, Native American, and Asian.

gSome patients carried more than 1 foreign device.

hIncludes heart valves, implantable pacemakers, automated implantable cardioverter-defibrillators, and Left Ventricular Assist Devices.

iIncludes vascular stents, vascular clips, biliary stents, urinary stents, draining tubes, percutaneous feeding tubes, intrathecal catheters, vena cava filters, peritoneal dialysis catheters, esophageal stents, meshes, penile implants, breast implants, tracheostomy tubes, spinal cord stimulation implants, drug delivery implants, and intra-aortic balloon pumps.

jCalculated on Day 1 of SAB.

kScore change, annually.

lCalculated as part of the APACHE II score: 0, no severe organ system insufficiency or immune compromise; 2, severe organ system insufficiency or immune compromise and elective postoperative; 5, severe organ system insufficiency or immune compromise and nonoperative or emergency postoperative [10].

mSome patients had more than 1 complication.

nDefined as persistently positive blood cultures for ≥5 days after initiation of appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

oIncludes cases of pneumonia, empyema, pericarditis, mycotic aneurysm, endophthalmitis, myositis, fasciitis, and urinary tract infections.

Figure 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population that exhibited a significant trend over the study period. Lines represent the proportion of patients with a history of diabetes mellitus, corticosteroid use, transplantation, neoplasm, or prosthetic device(s).

The site of acquisition of SAB shifted over the 21-year study period. Rates of hospital-acquired SAB decreased 1.9% annually, from 50.5% of cases in 1995 to 19.4% in 2015 (P < .0001). Simultaneously, CA-HCA increased by 1.4% annually, from 46.3% to 68.5% (P < .0001), and CA-NHCA SAB increased by 0.6% annually, from 3.2% to 12.0% (P < .0001).

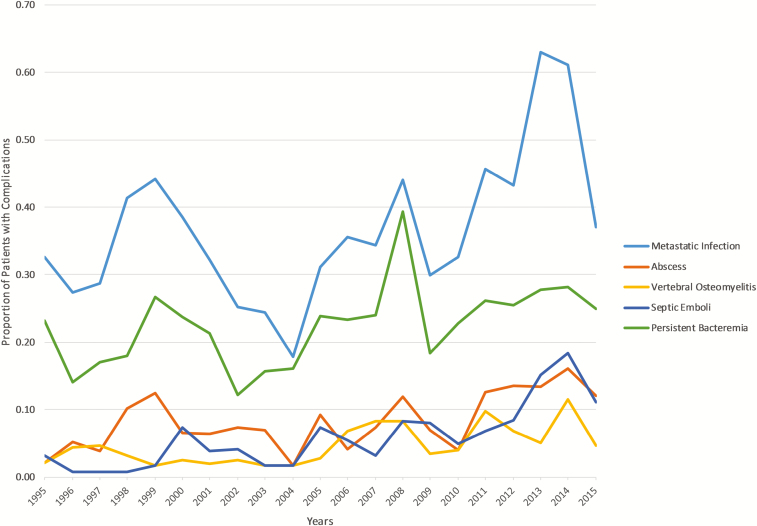

Patient Outcomes

Rates of crude and attributable mortality were 26.5 and 13.5%, respectively. Clinical outcomes did not differ over the study period. However, the overall rate of detected metastatic infections increased by 0.9% annually (P = .019). This increase in overall metastatic infections was driven by significant annual increases in abscesses (annual increase 0.4%; P = .004), vertebral osteomyelitis (0.3%; P = .002), epidural abscesses (0.2%; P = .004), septic thrombophlebitis (0.2%; P = .044), endocarditis (0.5%; P = .049), and septic emboli (0.6%; P < .0001; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Annual distribution of all metastatic complications of SAB and of abscesses, vertebral osteomyelitis, septic emboli, and persistent bacteremia. Only metastatic complications with a significant trend are shown. Abbreviation: SAB, Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia.

Potential for Ascertainment Bias

No significant difference was noted in the number of imaging studies ordered on a 10%, randomly selected sample of study patients, with the exception of transthoracic echocardiograms. From 1995 to 2015, there was an annual increase of 1.6% in transthoracic echocardiogram use (P < .0001; Supplementary Table 2).

Phenotypic and Genotypic Studies of Staphylococcus aureus Isolates

Among 2348 unique S. aureus isolates, 1222 (52%) were methicillin-susceptible (MSSA). The annual distribution of methicillin-resistant (MRSA) and MSSA isolates is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

We identified 411 distinct spa types, which were clustered to 16 spa-CCs. A total of 85 (3.6%) isolates remained nontypeable after 2 attempts. During the synchronization process with the global Ridom database, 3 new repeats and 86 new spa types were identified. There were 10 (0.4%) isolates that could not be aligned to known or new spa types (Supplementary Tables 3 and 3a). The most common spa-CCs were spa-CC002 (MLST CC5), -CC012 (MLST CC30), and -CC008 (MLST CC8; 30.0, 20.6, and 16.8%, respectively), which together comprised 67.4% of the study isolates.

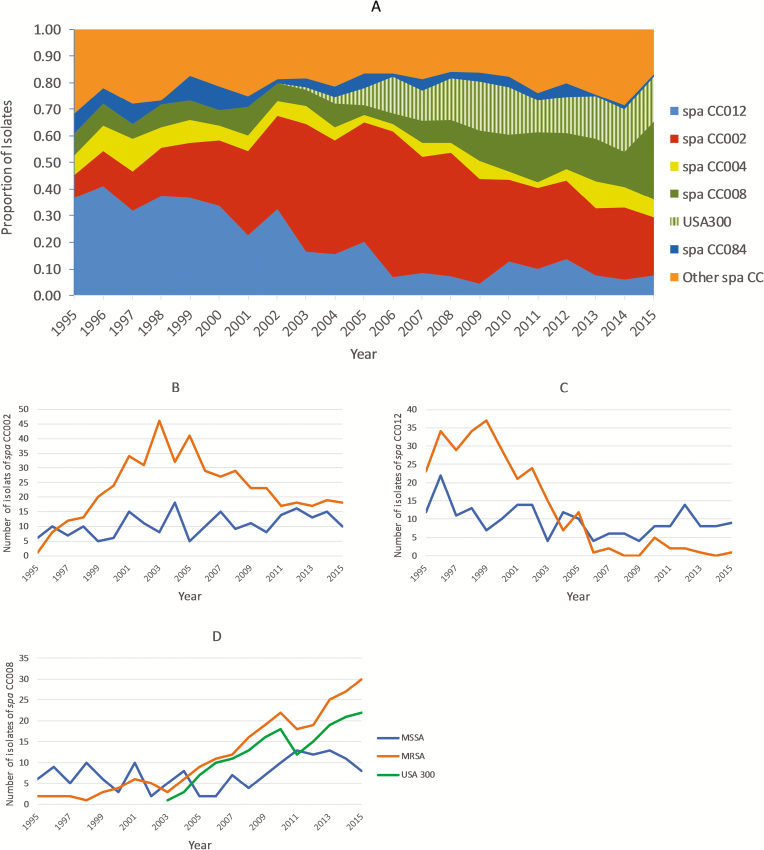

From 1995 to 2015, genotypes of the bloodstream S. aureus isolates changed significantly. The prevalence of spa-CC012 (MLST CC30) decreased from 36.8% of patients in 1995 to 9.3% in 2015 (annual decrease 1.8%; P < .0001). Simultaneously, the prevalence of spa-CC008 (MLST CC8) quadrupled, from 8.4% in 1995 to 35.2% in 2015 (annual increase 1.6%; P < .0001). The annual distribution of spa types within spa-CC008 (MLST CC8) is shown in Supplementary Table 4. The prevalence of spa-CC002 (MLST CC5) did not increase significantly during the study period (P = .074; Figure 3A). These findings remained consistent and robust when we repeated the genotypic characterization using eGenomics software (data not shown).

Figure 3.

A, Annual distribution of CC causing SAB in our institution over the 21-year study period. USA300 clonal type is shown as hatched area within spa-CC008. Spa-CC012 corresponds to MLST CC30, -CC002 to MLST CC5, -CC004 to MLST CC45, -CC008 to MLST CC8, and -CC084 to MLST CC15. For other CCs refer to Supplementary Table 3. B–D, Distribution of predominant CCs, stratified by methicillin susceptibility. Abbreviations: CC, clonal complexes; MLST, multi-locus sequence typing; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; SAB, Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia.

Figure 3B–D depict the distribution of MRSA within each of the predominant clones over the course of the 21 years. Spa-CC002 (MLST CC5) consisted primarily of MRSA isolates (68.7%). The proportion of MRSA within spa-CC012 (MLST CC30) decreased by 3.8% annually, but increased by 3% within spa-CC008 (MLST CC8; both, P < .0001). Spa-CC004 (MLST CC45), -CC84 (MLST CC15), and -CC189 (MLST CC1) consisted primarily of MSSA (90.2, 94.9, and 80.6%, respectively), without significant changes over the study period (data not shown).

Associations Between the Phenotypic Characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia and the Genotype of Staphylococcus aureus Isolates

In the univariate analysis, the spa-CC008 (MLST CC8) genotype was associated with overall metastatic infections (P = .001), including metastatic abscesses (P = .005), septic emboli (P = .018), persistent bacteremia (P = .001), and the heterogeneous group of other metastatic infections, such as pneumonia, empyema, pericarditis, mycotic aneurysm, endophthalmitis, myositis, fasciitis, and urinary tract infections (P < .0001). However, spa-CC008 was not associated with treatment failure, recurrent bacteremia, or mortality.

Among spa-CC008 (MLST CC8) isolates, a total of 168 (42.5%) were methicillin resistant and positive for both PVL and ACME, and were designated as USA300. USA300 emerged as a cause of SAB in our institution in 2003, and has increased in frequency thereafter, constituting 20.4% of all episodes of SAB in 2015 (P < .0001; Figure 3A and 3D).

In a multivariable analysis (Table 2), the USA300 strain type was significantly associated with a higher risk for overall metastatic complications (odds ratio [OR] 1.42, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02–1.99), including septic emboli (OR 2.05, 95% CI 1.20–3.48) and persistent bacteremia (OR 1.95, 95% CI 1.38–2.78), even after adjusting for variables including age, gender, race, comorbidities, and site of acquisition of SAB. This association was limited to USA300 variants, as the spa-CC008 clonal lineage outside of the USA300 subtype was not associated with metastatic complications. When USA300 was compared to all other MRSA types, the associations with metastatic complications, emboli, or persistent bacteremia were not significant (data not shown). This may be due to the loss of statistical power associated with a significant reduction in the sample size.

Table 2.

Multivariable Analysis of Variables Associated With Metastatic Complications, Abscess, Emboli, and Persistent Bacteremia

| Metastatic Complications | Abscess | Emboli | Persistent Bacteremia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | |||

| Genotype | ||||

| All genotypes except spa-CC008 | Reference | |||

| spa-CC008 non-USA300 | 1.17 (.87–1.56) | 1.41 (.89–2.22) | 0.98 (.55–1.77) | 1.17 (.84–1.63) |

| USA300 | 1.42 (1.02–1.99) a | 1.52 (.93–2.46) | 2.05 (1.20–3.48) b | 1.95 (1.38–2.78) b |

| Age | 1.00 (.99–1.00) | 1.00 (.99–1.01) | 0.97 (.96–.98) b | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) a |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | Reference | |||

| Female | 0.76 (.64–.91) b | 0.67 (.49–.91) a | 0.93 (.65–1.34) | 0.91 (.75–1.12) |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | Reference | |||

| African American | 0.80 (.65–.98) a | 0.85 (.60–1.22) | 0.74 (.49–1.12) | 1.00 (.79–1.27) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.27 (1.05–1.53) a | 1.28 (.93–1.74) | 1.02 (.69–1.49) | 1.14 (.92–1.40) |

| End-stage renal disease | 0.88 (.69–1.13) | 0.70 (.45–1.10) | 1.22 (.75–1.99) | 1.80 (1.37–2.37) b |

| Neoplasm | 0.65 (.51–.83) b | 0.83 (.56–1.25) | 0.90 (.54–1.50) | 0.68 (.51–.90) b |

| Transplantation | 0.45 (.30–.67) b | 0.70 (.36–1.36) | 1.18 (.61–2.31) | 0.67 (.43–1.03) |

| Corticosteroid use | 1.80 (1.41–2.29) b | 1.36 (.91–2.02) | 1.18 (.73–1.90) | 1.79 (1.37–2.34) b |

| Presence of central vascular catheter (any type) | 0.7 (.6–.9) b | 0.5 (.3–.8) b | 0.9 (.6–1.4) | 1.17 (.9–1.5) |

| Site of acquisition | ||||

| CA-HCA | Reference | |||

| HA | 0.45 (.36–.55) b | 0.44 (.29–.66) b | 0.33 (.19–.58) b | 0.96 (.75–1.22) |

| CA-NHCA | 1.81 (1.34–2.44) b | 1.54 (1.00–2.37) | 1.62 (.97–2.70) | 1.61 (1.15–2.27) b |

Results for each variable are adjusted for all other variables shown. ORs marked in bold are significant.

Abbreviations: CA-HCA, community-acquired, healthcare–associated; CA-NHCA, community acquired, nonhealthcare–associated; CI, confidence interval; HA, hospital-acquired; OR, odds ratio.

a P < .05.

b P < .01.

Other associations between strain characteristics and clinical phenotypes of SAB are shown in Supplementary Tables 5 and 6. No association was found between endocarditis or vertebral osteomyelitis and S. aureus genotypes.

DISCUSSION

This study confirms that the clinical presentation of SAB in the early 21st century differs from that of SAB encountered in previous decades. The morbidity of the patients has increased as the clinical presentation has become more complicated. This could be the result of changes in the characteristics of the patient population, in the clones causing SAB, or both.

This study documents that the clones causing SAB at a single center differ significantly over time, and that these changes can have clinical consequences. Using a prospective cohort that spans 2 decades and includes over 2300 patients with SAB, the study demonstrated that spa-CC008 has progressively replaced multiple other previously predominant clones at our institution. After adjusting for patient comorbid conditions, USA300 was independently associated with metastatic complications in patients with SAB.

First identified in the late 1990s [18], USA300 rapidly emerged to become the dominant community-acquired MRSA in North America [19, 20]. Although originally a cause of skin and soft issue infections, USA300 has progressively become endemic in nosocomial settings, and is now the most common MRSA type isolated from bloodstream infections in parts of the United States [19, 21, 22]. The success and high virulence of USA300 is thought to be due, in part, to its acquisition of various mobile genetic elements: namely, SCCmec type IVa, carrying the mecA gene; S. aureus pathogenicity island 5, containing sek (gene encoding enterotoxin K) and seq (gene encoding enterotoxin Q); phage phiSA2, carrying the PVL genes; and ACME type I, carrying the arginine deiminase cluster [arc] and speG gene [23–26]. USA300 has also been shown to exhibit increased expression of α-toxin and phenol-soluble modulins (cytolytic toxins), due to overexpression of the global transcriptional regulators agr and sae [27]. This extraordinary array of virulence factors and traits of enhanced invasiveness could explain the striking association of USA300 with metastatic complications of SAB shown in this study, and is consistent with the findings of other recent investigations [28].

Patient characteristics also changed during the study period. Patients had higher rates of comorbid conditions, including diabetes mellitus, cancer, transplantation, rheumatoid arthritis, and corticosteroid use. This may be the consequence of either the increasing prevalence of these conditions, the increasing life expectancy of patients suffering from these conditions [29], and/or the increasing use of the advances offered by modern medicine that predispose patients to SAB. Overall, patients with SAB were significantly sicker in 2015 than they were in 1995, by any measure. The only notable exception was in patients with ESRD, which was less commonly identified among patients with SAB in 2015 versus 1995. Plausible explanations could be the advances in vascular access methods, as permanent central venous catheters have increasingly been replaced by arteriovenous fistulas or vascular grafts; improvements in infection control practices in this population; or fewer patients with ESRD served in our institution over the 21-year study period.

A critical emerging characteristic of study patients during the study was the increased presence of prosthetic devices. By the end of the enrollment period, over half of study patients had at least 1 indwelling prosthetic device. The role of prosthetic devices—including pacemakers/defibrillators, prosthetic valves, endovascular prostheses, and arthoplasties—in the prevalence and changing epidemiology of SAB have been well documented [30–32].

Our study confirms that SAB remains primarily a consequence of health-care contact. Almost 88% of patients had CA-HCA infections in 2015. This percentage has significantly dropped, from ~97% in 1995. By contrast, 80% of patients developed their SAB outside the hospital in 2015, versus 50% in 1995. These shifts likely reflect the substantive changes in health-care delivery over the past 2 decades, with increasing outpatient care delivery and increasing use of indwelling prosthetic devices, and have been previously described among patients with S. aureus endocarditis [33]. In our study, true community-acquired infections significantly increased, from 3.2% in 1995 to 12% in 2015. This trend has been documented in the United States since the early 2000s [34], has been validated in all types of health-care settings, and has been linked to the emergence of community-associated MRSA: notably, the USA300 strain type [35–38].

This study has significant strengths. To perform this study, we used a unique resource, the SABG-PCS Biorepository, which has been maintained for 24 years to date. It contains robust clinical data and bacterial bloodstream isolates from more than 2700 prospectively ascertained patients, setting it among the largest resources of its kind in the world. To genotype these isolates, we developed and validated an in-house, high-throughput, DNA isolation method. Finally, we repeated our genotype-phenotype associations using 2 different software platforms for CC assignment: eGenomics and Ridom StaphType. Collectively, these design strengths allowed us to conclude that the results of the study are consistent, irrespective of the typing tool used.

Our study has limitations. It is possible that, as the abstractors have changed over the course of 2 decades, inconsistencies in data capture may have occurred. To minimize potential biases, the same standardized case report form, with the same data abstraction guidelines and definitions, was used throughout. In addition, random validation was performed by a single investigator (F. R.) for missing data or inconsistencies, and data were rectified as needed. Our study is subject to referral bias. It is possible that results deriving from 1 academic referral center may not be generalizable to other medical centers in the country. For example, a study of 5 geographically dispersed centers in the United States showed marked decreases in USA300 prevalence in some locations, like Los Angeles, and significant increases in others, like New York. It is unclear whether these patterns simply represent local trends or different phases in the expansion and contraction of USA300. In our center, which was 1 of the 5 academic medical centers of that study, USA300 accounted for 35% of the 80 MRSA isolates examined [35].

The management of SAB has changed over the past 2 decades that this study has enrolled patients, thereby introducing potential biases. However, we found no evidence for any biases in the diagnosis of abscesses, osteoarticular infections, or emboli when we evaluated the use of imaging practices in a 10% subset of study patients. Finally, we did not perform pulsed-field gel electrophoresis to unequivocally distinguish the USA300 strain type within our collection of isolates, but used a consensus definition (spa-CC008, methicillin resistance, PVL positivity, and ACME positivity) that has been previously validated in the literature to accurately identify this type [17, 26] being aware that USA300 strains that are PVL and/or ACME negative have emerged but are still quite rare [38, 39].

In conclusion, shifts in bacterial genetics can have significant consequences in the infections that they cause. Interestingly, most of these shifts in bacterial genotypes and severities of infections are likely to go unnoticed by the busy practitioner. Systematic approaches for bacterial genotyping and recording rates of specific complications will likely have a bidirectional benefit: improving clinical management and offering an effective means of detecting subtle shifts in clinical syndromes, which could indicate the emergence of a new, hypervirulent bacterial clone.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Presented in part: IDWeek 2017, San Diego, CA, 4–8 October 2017. Poster Number 1889.

Notes

Disclaimer.The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Financial support.This work was supported by the NNIH (grant numbers U01 AI-124319-01, 2R01-AI068804, and K24-AI093969 to V. G. F.).

Potential conflicts of interest.V. G. F. served as Chair of the V710 Scientific Advisory Committee (Merck); has received grant support from Cerexa/Actavis/Allergan, Pfizer, Advanced Liquid Logics, NIH, MedImmune, Basilea Pharmaceutica, Cubist/Merck, Karius, ContraFect, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, and Genentech; has NIH Small Business Technology Transfer/Small Business Innovation grants pending with Affinergy, Locus, and Medical Surface, Inc; has been a consultant for Achaogen, AmpliPhi Biosciences, Astellas Pharma, Arsanis, Affinergy, Basilea Pharmaceutica, Bayer, Cerexa Inc., ContraFect, Cubist, Debiopharm, Destiny Pharmaceuticals, Durata Therapeutics, Grifols, Genentech, MedImmune, Merck, The Medicines Company, Pfizer, Novartis, NovaDigm Therapeutics Inc., Regeneron, Theravance Biopharma, Inc., XBiotech, and Integrated BioTherapeutics; has received honoraria from Theravance Biopharma, Inc., and Green Cross; and has a patent pending in sepsis diagnostics. S. A. M. was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (grant number 1KL2TR002554). All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Fowler VG Jr, Nelson CL, McIntyre LM, et al. Potential associations between hematogenous complications and bacterial genotype in Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Infect Dis 2007; 196:738–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nienaber JJ, Sharma Kuinkel BK, Clarke-Pearson M, et al. ; International Collaboration on Endocarditis-Microbiology Investigators Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis isolates are associated with clonal complex 30 genotype and a distinct repertoire of enterotoxins and adhesins. J Infect Dis 2011; 204:704–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rieg S, Jonas D, Kaasch AJ, et al. Microarray-based genotyping and clinical outcomes of Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection: an exploratory study. PLOS One 2013; 8:e71259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blomfeldt A, Aamot HV, Eskesen AN, Müller F, Monecke S. Molecular characterization of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus isolates from bacteremic patients in a Norwegian University Hospital. J Clin Microbiol 2013; 51:345–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fernández-Hidalgo N, Ribera A, Larrosa MN, et al. Impact of Staphylococcus aureus phenotype and genotype on the clinical characteristics and outcome of infective endocarditis. A multicenter, longitudinal, prospective, observational study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24:985–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Otter JA, French GL. Molecular epidemiology of community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Europe. Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10:227–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tenover FC, Goering RV. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain USA300: origin and epidemiology. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009; 64:441–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chua KY, Seemann T, Harrison PF, et al. The dominant Australian community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone ST93-IV [2B] is highly virulent and genetically distinct. PLOS One 2011; 6:e25887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Glaser P, Martin-Simoes P, Villain A, et al. Demography and intercontinental spread of the USA300 community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lineage. MBio 2016; 7:e02183-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med 1985; 13:818–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Friedman ND, Kaye KS, Stout JE, et al. Health care–associated bloodstream infections in adults: a reason to change the accepted definition of community-acquired infections. Ann Intern Med 2002; 137:791–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, et al. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis 2000; 30:633–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mathema B, Mediavilla J, Kreiswirth BN. Sequence analysis of the variable number tandem repeat in Staphylococcus aureus protein A gene: spa typing. Methods Mol Biol 2008; 431:285–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Berlon NR, Qi R, Sharma-Kuinkel BK, et al. Clinical MRSA isolates from skin and soft tissue infections show increased in vitro production of phenol soluble modulins. J Infect 2015; 71:447–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carrel M, Perencevich EN, David MZ. USA300 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, United States, 2000–2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21:1973–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. O’Hara FP, Suaya JA, Ray GT, et al. Spa typing and multilocus sequence typing show comparable performance in a macroepidemiologic study of Staphylococcus aureus in the United States. Microb Drug Resist 2016; 22:88–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. David MZ, Taylor A, Lynfield R, et al. Comparing pulsed-field gel electrophoresis with multilocus sequence typing, spa typing, staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) typing, and PCR for Panton-Valentine leukocidin, arcA, and opp3 in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates at a U.S. Medical Center. J Clin Microbiol 2013; 51:814–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Centers for Disease Control. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin or soft tissue infections in a state prison—Mississippi, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001; 50:919–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Diekema DJ, Richter SS, Heilmann KP, et al. Continued emergence of USA300 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the United States: results from a nationwide surveillance study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014; 35:285–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. King MD, Humphrey BJ, Wang YF, Kourbatova EV, Ray SM, Blumberg HM. Emergence of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA 300 clone as the predominant cause of skin and soft-tissue infections. Ann Intern Med 2006; 144:309–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Seybold U, Kourbatova EV, Johnson JG, et al. Emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 genotype as a major cause of health care-associated blood stream infections. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42:647–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tenover FC, Tickler IA, Goering RV, Kreiswirth BN, Mediavilla JR, Persing DH; MRSA Consortium Characterization of nasal and blood culture isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from patients in United States Hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:1324–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Planet PJ, LaRussa SJ, Dana A, et al. Emergence of the epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain USA300 coincides with horizontal transfer of the arginine catabolic mobile element and speG-mediated adaptations for survival on skin. Bio 2013; 4:e00889-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crémieux AC, Saleh-Mghir A, Danel C, et al. α-Hemolysin, not Panton-Valentine leukocidin, impacts rabbit mortality from severe sepsis with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis. J Infect Dis 2014; 209:1773–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Diep BA, Palazzolo-Ballance AM, Tattevin P, et al. Contribution of Panton-Valentine leukocidin in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis. PLOS One 2008; 3:e3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Diep BA, Gill SR, Chang RF, et al. Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 2006; 367:731–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li M, Diep BA, Villaruz AE, et al. Evolution of virulence in epidemic community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009; 106:5883–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lessa FC, Mu Y, Ray SM, et al. ; Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs); MRSA Investigators of the Emerging Infections Program Impact of USA300 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus on clinical outcomes of patients with pneumonia or central line-associated bloodstream infections. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:232–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic disease prevention and health promotion. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/stats/. Accessed 4 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murdoch DR, Roberts SA, Fowler VG Jr, et al. Infection of orthopedic prostheses after Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 32:647–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. El-Ahdab F, Benjamin DK Jr, Wang A, et al. Risk of endocarditis among patients with prosthetic valves and Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Am J Med 2005; 118:225–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chamis AL, Peterson GE, Cabell CH, et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in patients with permanent pacemakers or implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Circulation 2001; 104:1029–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fowler VG Jr, Miro JM, Hoen B, et al. ; ICE Investigators Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis: a consequence of medical progress. JAMA 2005; 293:3012–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chambers HF. The changing epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus? Emerg Infect Dis 2001; 7:178–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. David MZ, Daum RS, Bayer AS, et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia at 5 US academic medical centers, 2008–2011: significant geographic variation in community-onset infections. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:798–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Anderson DJ, Moehring RW, Sloane R, et al. Bloodstream infections in community hospitals in the 21st century: a multicenter cohort study. PLOS One 2014; 9:e91713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sherwood J, Park M, Robben P, Whitman T, Ellis MW. USA300 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus emerging as a cause of bloodstream infections at military medical centers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013; 34:393–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tickler IA, Goering RV, Mediavilla JR, Kreiswirth BN, Tenover FC; HAI Consortium Continued expansion of USA300-like methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among hospitalized patients in the United States. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2017; 88:342–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pardos de la Gandara M, Curry M, Berger J, et al. MRSA causing infections in hospitals in greater metropolitan New York: major shift in the dominant clonal type between 1996 and 2014. PLOS One 2016; 11:e0156924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.