Abstract

RNA has been classically known to play central roles in biology, including maintaining telomeres, protein synthesis, and in sex chromosome compensation. While thousands of long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been identified, attributing RNA-based roles to lncRNA loci requires assessing whether phenotype(s) could be due to DNA regulatory elements, transcription, or the lncRNA. Here, we use the conserved X chromosome lncRNA locus Firre, as a model to discriminate between DNA- and RNA-mediated effects in vivo. We demonstrate that (i) Firre mutant mice have cell-specific hematopoietic phenotypes, and (ii) upon exposure to lipopolysaccharide, mice overexpressing Firre exhibit increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and impaired survival. (iii) Deletion of Firre does not result in changes in local gene expression, but rather in changes on autosomes that can be rescued by expression of transgenic Firre RNA. Together, our results provide genetic evidence that the Firre locus produces a trans-acting lncRNA that has physiological roles in hematopoiesis.

Subject terms: Stem cells, Gene expression, Cytokines, Lymphopoiesis, Long non-coding RNAs

LncRNA loci potentially contain multiple modes that can exert function, including DNA regulatory elements. Here, the authors generated genetic models in mice to dissect the role of the syntenically conserved lncRNA Firre in the context of hematopoiesis.

Introduction

Transcription occurs at thousands of sites throughout the mammalian genome. Many of these sites are devoid of protein-coding genes and instead contain long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs). While lncRNA loci have been implicated in a variety of biological functions, comparatively few lncRNA loci have been genetically defined to have RNA-based roles. Indeed, deletions of entire lncRNA loci have uncovered a number of in vivo phenotypes1–5; however, this approach alone is confounded because in addition to the lncRNA transcript, lncRNA loci can also exert function through DNA regulatory elements6–8, the promoter region9, as well as by the act of transcription10,11. Thus, attributing RNA-based role(s) to lncRNA loci requires testing whether other regulatory modes potentially present at the locus have molecular activity that could contribute to phenotypic effects3,12,13.

In this study, we use the functional intergenic repeating RNA element, (Firre) locus as a model to discriminate between DNA- and RNA-mediated effects in vivo. We selected this locus for our study because it is syntenically conserved in a number of mammals, including human14–17, and because studies have reported diverse biological and molecular roles. Early characterization of the FIRRE locus in human cell lines identified it as a region that interacts with the X-linked macrosatellite region, DXZ4, in a CTCF-dependent manner18–21. Further analyses of the Firre locus demonstrated that it produces a lncRNA that escapes X-inactivation15,22–24, although it is predominately expressed from the active X chromosome21,25. Studies using cell culture models suggest that the Firre locus has biological roles in multiple processes, including adipogenesis26, nuclear architecture15,19,21, and in the regulation of gene expression programs15,27. In addition, there is some evidence for roles of the FIRRE locus in human development and disease28–31. Collectively, these studies demonstrate the diverse cellular and biological functions for the Firre locus. However, the biological roles of Firre as well as disentangling DNA- and RNA-mediated function(s) for the Firre locus have not been explored in vivo.

Using multiple genetic approaches, we describe an in vivo role for the Firre locus during hematopoiesis. We report that Firre mutant mice have cell-specific defects in hematopoietic populations. Deletion of Firre is accompanied by significant changes in gene expression in a hematopoietic progenitor cell type, which can be rescued by induction of Firre RNA from an autosomal transgene within the Firre knockout background. Mice overexpressing Firre have increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and significantly impaired survival upon exposure to lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Finally, the Firre locus does not contain cis-acting RNA or DNA elements (including the promoter) that regulate neighboring gene expression on the X chromosome (nine biological contexts examined), suggesting that Firre does not function in cis. Collectively, our study provides evidence for a trans-acting RNA-based role for the Firre locus that, thus far, has physiological importance for hematopoiesis.

Results

The Firre locus produces an abundant lncRNA

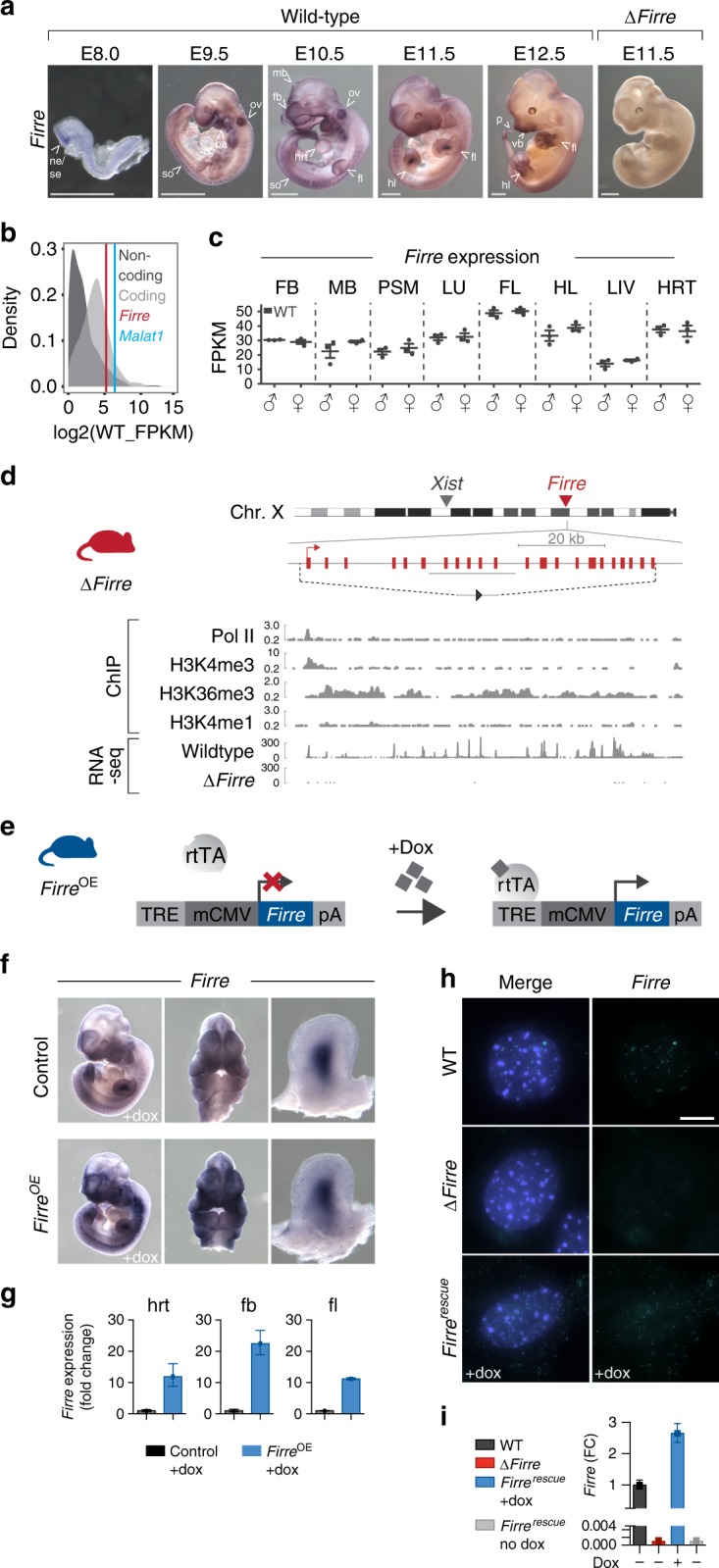

We first sought to investigate the gene expression properties for Firre RNA in vivo. To determine potential spatial and temporal aspects of Firre RNA expression during development, we performed in situ hybridization in wild-type (WT) mouse embryos (E8.0–E12.5). Notably, we detected Firre RNA in many embryonic tissues, including the forebrain, midbrain, pre-somitic mesoderm, lung, forelimb, hindlimb, liver, and heart (Fig. 1a). Since noncoding RNAs have been described to be generally expressed at lower levels compared with protein-coding genes32–35, we determined the relative abundance of Firre RNA in vivo. We performed RNA-seq on eight different WT embryonic tissues and plotted the expression of noncoding and coding transcripts. Consistent with previous reports32–35, we observed that noncoding transcripts were generally less abundant than protein-coding transcripts (Fig. 1b). Despite most lncRNAs being expressed at low levels, we found that Firre, like Malat1 (refs36–38), is an abundant transcript (Fig. 1b). Next, since Firre is located on the X chromosome and escapes X-inactivation15,22–24, we investigated whether Firre has different expression levels in male and female WT tissues. While levels of Firre RNA varied across embryonic tissue types, within individual tissues, male and female samples exhibited similar expression levels of Firre, despite escaping X-inactivation (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1.

Mouse models to interrogate the in vivo function of Firre. a Whole-mount in situ hybridization for Firre RNA in WT mouse embryos at E8.0 (n = 4), E9.5 (n = 4), E10.5 (n = 5), E11.5 (n = 6), E12.5 (n = 4), and ∆Firre E11.5 embryos (n = 3). Scale bar equals 1 mm. b Distribution of transcript abundances for protein-coding (light gray) and noncoding (dark gray) genes in WT E11.5 heart tissue (representative tissue shown from seven additional tissues). Vertical lines indicate Firre (red) and Malat1 (blue). c Expression of Firre shown as fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) from RNA-seq in E11.5 WT male (n = 3) and female (n = 3) forebrain (FB), midbrain (MB), pre-somitic mesoderm (PSM), lung (LU), forelimb (FL), hindlimb (HL), liver (LIV), and heart (HRT). The data shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). d Firre knockout mouse (red). Schematic of mouse X chromosome ideogram showing the Firre locus relative to Xist. UCSC genome browser diagram of the Firre locus (shown in opposite orientation). Dashed lines indicate the genomic region that is deleted in ∆Firre mice; single loxP scar upon deletion (gray triangle). Histone modifications and transcription factor binding sites in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESC-Bruce4, ENCODE/LICR, mm9). RNA-seq tracks for the Firre locus in WT and ∆Firre E11.5 forelimbs. e Schematic of doxycycline (dox)-inducible Firre overexpression mouse (FirreOE). Tet-responsive element (TRE), minimal CMV promoter (mCMV), reverse tetracycline transcriptional activator (rtTA), and β-globin polyA terminator (pA). f In situ hybridization for Firre at E11.5 in control (WT or tg(Firre) +dox) (n = 4) and FirreOE +dox (n = 3) embryos. g qRT-PCR for Firre expression shown as fold change (FC) in dox-treated E11.5 control and FirreOE hrt, fb, and fl. h RNA FISH for Firre in male WT, ∆Firre, and Firrerescue MEFs. DAPI (blue) marks the nucleus and Firre RNA is shown in green. Scale bar equals 10 µm. i qRT-PCR for Firre expression shown as FC in male WT, ∆Firre, Firrerescue +dox, and Firrerescue no dox MEFs. Expression normalized to β-actin in the control or WT sample. The data plotted as mean ± CI at 98%. Source data are provided in the Source Data file

Firre knockout and overexpression mice are viable and fertile

To investigate the in vivo role of Firre and assess DNA- and RNA-mediated effects, we generated both Firre loss-of-function and Firre overexpression mice. To delete the Firre locus in vivo, we generated a mouse line containing a floxed allele (Firrefloxed) from a previously targeted mouse embryonic stem cell line15 and mated to a CMV-Cre deleter mouse39. This produced a genomic deletion (81.8 kb) that removed the entire Firre gene body and promoter (henceforth called ∆Firre) (Fig. 1d). We confirmed the deletion of the Firre locus by genotyping (Supplementary Fig. 1) and examined Firre RNA expression. As expected, we did not detect Firre RNA in ∆Firre embryos by whole-mount in situ hybridization or by RNA-seq (Fig. 1a, d).

Since Firre is found on the X chromosome, we first sought to determine if deletion of the locus had an effect on the expected sex ratio of the progeny. Matings between ∆Firre mice produced viable progeny and had a normal frequency of male and female pups (Supplementary Table 1) that did not exhibit overt morphological, skeletal, or weight defects (Supplementary Fig. 2). Moreover, deletion of Firre did not impact expression levels of Xist RNA in embryonic tissues or perturb Xist RNA localization during random X chromosome inactivation (XCI) in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (Supplementary Fig. 3A–C).

Because the ∆Firre allele removes the entire gene body, this model does not allow us to distinguish between DNA- and RNA-mediated effects. Therefore, in order to be able to investigate the role of Firre RNA, we generated a doxycycline (dox)-inducible Firre overexpression mouse. This mouse model was engineered to contain a Firre cDNA downstream of a tet-responsive element (henceforth called tg(Firre)), and was mated to mice that constitutively express the reverse tetracycline transcriptional activator (rtTA) gene (combined alleles henceforth called FirreOE) (Fig. 1e). This approach enabled systemic induction of Firre RNA in a temporally controllable manner by the administration of dox. Moreover, by combining the FirreOE and ∆Firre alleles (henceforth called Firrerescue), we could test whether Firre RNA expression alone is sufficient to rescue phenotypes arising in the ∆Firre mice, thereby distinguishing DNA- and RNA-based effects.

To confirm expression of transgenic Firre RNA, tg(Firre) females were mated with rtTA males and placed on a dox diet the day a copulatory plug was detected, and embryos were collected at E11.5 for analyses. Compared with sibling control embryos, we detected increased Firre RNA in FirreOE embryos by whole-mount in situ hybridization (Fig. 1f) and by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) (heart, 16-fold; forebrain, 26.6-fold; and forelimb, 11.5-fold) (Fig. 1g). Moreover, matings between tg(Firre) and rtTA mice fed a dox diet produce viable progeny that overexpress Firre at expected male and female frequencies (Supplementary Table 1).

Firre RNA has been reported to be largely enriched in the nucleus of mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs)15,40, neuronal precursor cells39, and HEK293 cells17, and also has been reported in the cytoplasm of a human colon cell line27. Thus, we investigated the subcellular localization of Firre in the genetic models using RNA fluorescent in situ hybridization (RNA FISH). In contrast to ∆Firre MEFs, we detected pronounced localization of Firre RNA in the nucleus of WT MEFs (Fig. 1h). In dox-treated Firrerescue MEFs, which only produce Firre RNA from the transgene, we detected Firre RNA in both the nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 1h), which corresponded to approximately a 2.7-fold increase in Firre RNA relative to WT (Fig. 1i). Notably, the Firrerescue transgenic model showed both nuclear and cytoplasmic localization of Firre, suggesting a threshold level control for nuclear localized Firre.

Tissue-specific gene dysregulation in ∆Firre tissues

Given the broad expression profile of Firre RNA (Fig. 1a), we took an initial unbiased approach to explore the potential biological roles for the Firre locus, and performed poly(A)+ RNA-seq on eight E11.5 tissues from WT and ∆Firre embryos (forebrain, midbrain, heart, lung, liver, forelimb, hindlimb, and pre-somitic mesoderm). As expected, Firre expression was not detected in any of the ∆Firre tissues (Supplementary Data 1–8). Deletion of Firre was accompanied by significant changes in gene expression in all tissues examined (>1 FPKM, FDR<0.05) (Fig. 2a, b; Supplementary Data 1–8).

Fig. 2.

Modulation of Firre impacts genes with roles in the blood. a Schematized E11.5 tissues used for RNA-seq. WT (n = 6) shown in black, and ∆Firre (n = 6) shown in red. The number of differentially expressed genes shown below each tissue. b Heatmap of replicate embryonic tissues. c GO analysis for genes found dysregulated in four or more tissues. d Firre expression across multiple mouse blood cell lineages (RNA-seq data from bloodspot.eu, GSE60101). e Experimental approach for cytokine and survival experiments. f Cytokine measurements in serum at 5 h post intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 5 mg/kg LPS (broad acting) in WT (n = 8), ∆Firre (n = 8), FirreOE control diet (n = 6), FirreOE dox diet (n = 5–6), and saline-injected WT (n = 2) and ∆Firre (n = 2) (two independent experiments shown). g Cytokine measurements in serum at 5 h post i.p. injection of 5 mg/kg LPS (specific acting) in WT (n = 6), FirreOE control diet (n = 5), FirreOE dox diet (n = 4). Cytokine data are plotted as mean ± SEM, and significance determined by an unpaired two-tailed t test. h 6-day survival plot of mice injected with 5 mg/kg LPS (specific acting) in WT (n = 30), ∆Firre (n = 18), FirreOE control diet (n = 13), and FirreOE dox diet (n = 17) or saline control group (n = 10) consisting of WT, ∆Firre, and FirreOE mice over two independent experiments. Statistical difference determined by a by a Mantel–Cox test with P < 0.05 deemed significant. Source data are provided in the Source Data file

Across these eight tissues, we identified a total of 3910 significantly differentially expressed genes, of which 271 genes were differentially expressed in two or more tissues (Supplementary Data 1–8). Interestingly, gene ontology (GO) analysis of the commonly dysregulated genes showed that deletion of the Firre locus affected genes involved in hemoglobin regulation and general blood developmental processes (Fig. 2c). We therefore analyzed publicly available mouse RNA-seq data sets, and found that Firre is expressed across many blood cell types and note that expression is found highest in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs)41 and then decreases in conjunction with hematopoietic differentiation42 (Fig. 2d). Based on this information, we narrowed our investigation to evaluate potential roles for Firre in the blood system, and leveraged the genetic mouse models to test DNA- and RNA-mediated effects.

LPS potentiates the innate immune response in FirreOE mice

Firre is expressed in many innate immune cell types (Fig. 2d). Cell-based approaches have shown that Firre can be transcriptionally upregulated upon exposure to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and can modulate the levels of inflammatory genes in a human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line (SW480)27, mouse macrophage cell line (RAW264.7)27, as well as in an injury model using cultured primary rat microglial cells30. Thus, we hypothesized that dysregulation of Firre might alter the inflammatory response in vivo and reasoned that investigating the inflammatory response in Firre loss- and gain-of-function mice could provide insight into the DNA- and RNA-mediated effects of Firre. To test this, we employed a commonly used endotoxic shock model by administering LPS intraperitoneally to cohorts of WT, ∆Firre, FirreOE no dox, and dox-fed FirreOE mice in order to stimulate signaling pathways that regulate inflammatory mediators43 (Fig. 2e).

We administered two different LPS preparations, one which broadly stimulates the pattern recognition receptors toll-like receptors (TLR) 2, 4, and nitric oxide synthase, and an ultrapure LPS preparation that specifically stimulates TLR4 (refs44–46). At 5 h post LPS injection, we measured serum cytokine levels. Notably, we observed that FirreOE dox-fed mice administered broad-acting LPS had significantly higher levels of inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα, IL12-p40, and MIP-2 compared with WT (Fig. 2f). In contrast, we did not observe a significant difference for these cytokines in LPS-treated ∆Firre mice (Fig. 2f). Consistent with the increased cytokine response using broad-acting LPS, dox-fed FirreOE mice administered TLR4-specific-acting LPS also had significantly higher levels of TNFα, IL12-p40, and MIP-2 compared with WT (Fig. 2g), albeit at lower serum concentrations compared with the broad-acting LPS (Fig. 2f, g). In addition, we confirmed that overexpressing Firre RNA alone (without LPS) does not result in increased serum levels of TNFα, IL12-p40, and MIP-2 (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Because increased levels of TNFα is a hallmark of endotoxic shock47–49, we next tested whether the levels of Firre RNA had an impact on survival following LPS treatment. We administered 5 mg/kg of TLR4-specific-acting LPS to WT (n = 30), ∆Firre (n = 18), FirreOE no dox (n = 13), and FirreOE dox-fed (n = 17) mice, as well as a saline control group and monitored for 6 days. At this dose, across two independent cohorts, dox-treated FirreOE mice showed a significantly higher susceptibility to LPS compared with WT mice (P<0.0001, Mantel–Cox) and uninduced FirreOE animals (P = 0.0063, Mantel–Cox) (Fig. 2h). Whereas ∆Firre mice did not show a significant difference in the level of susceptibility to LPS (P = 0.1967, Mantel–Cox test) (Fig. 2h). Collectively, these results indicate that endogenous Firre does not appear to be necessary for a physiological inflammatory response to LPS, but that ectopic levels of Firre RNA can modulate this inflammatory response in vivo independent of genomic context, consistent with an RNA-based role for Firre.

Firre mice have cell-specific hematopoietic phenotypes

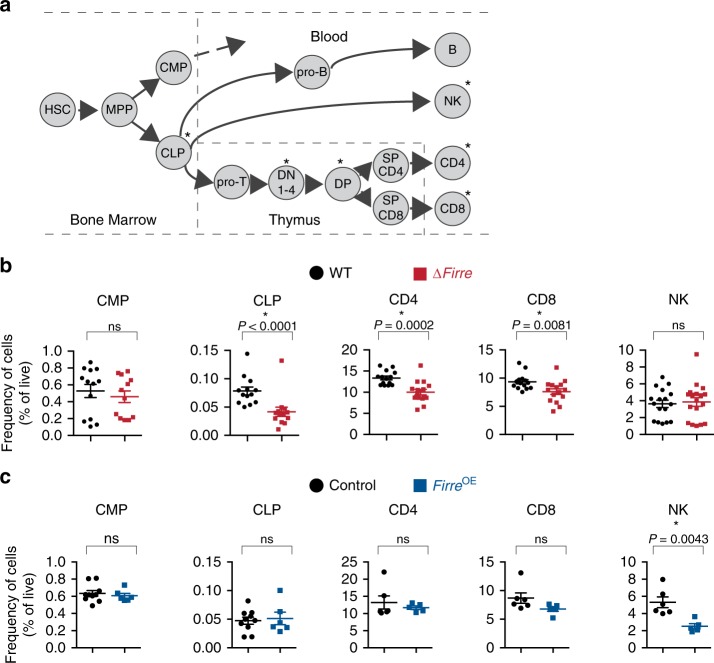

Having observed an effect of Firre in regulating gene expression and accentuating the inflammatory response, we further investigated the role of Firre in hematopoiesis (Fig. 3a). We first examined cell populations in the peripheral blood in ∆Firre mice and observed a modest but significant reduction in the frequencies of CD4 and CD8 T cells, whereas the frequencies of B and NK cells were unaffected compared with WT (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Fig. 5A). To investigate the cause of this reduction, we examined the thymus (to assess for a defect in T-cell development) and the bone marrow (to assess for a defect in hematopoietic progenitor cells). There was no block in thymic development in ∆Firre mice, as normal frequencies of cells were observed at each developmental stage (Supplementary Fig. 5B, upper panels). However, we noticed that the absolute number of cells was generally lower in ∆Firre mice at every developmental stage, suggestive of a pre-thymic defect in progenitor development (Supplementary Fig. 5B, lower panels). Consistent with this, in the bone marrow compartment, we observed a significant reduction in both the frequency and number of the common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) (lineage(lin)−Sca1loc-KitloIL7Rα+), a hematopoietic progenitor cell type, in ∆Firre mice (Fig. 3b; Supplementary Fig. 5C).

Fig. 3.

∆Firre and FirreOE mice have cell-specific hematopoietic phenotypes. a Schematic of hematopoiesis. b Frequencies of common myeloid progenitors (CMP) and common lymphoid progenitors (CLP) in the bone marrow shown from WT (n = 13, black circles) and ∆Firre (n = 12-13, red squares) mice. Two representative experiments combined (three independent experiments). Frequencies of CD4 and CD8 cells from the peripheral blood from WT (n = 14) and ∆Firre (n = 15) mice. Frequency of NK cells from the peripheral blood from WT (n = 17) and ∆Firre (n = 18) mice. Three representative experiments combined (seven independent experiments). c Frequencies of CMPs and CLPs from the bone marrow from control (tg(Firre) or WT or rtTA with dox) (n = 10, black circle) and FirreOE +dox (n = 6, blue square) mice. One representative experiment is shown (two independent experiments). Frequencies of CD4, CD8, and NK cells from the peripheral blood from control (WT or tg(Firre) or rtTA with dox) (n = 6, black circle) and FirreOE +dox (n = 5, blue square) mice. One representative experiment is shown (three independent experiments). Cell frequencies determined by flow cytometry analysis. The data are plotted as percent (%) of live cells showing the mean ± SEM, and statistical significance determined by a two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test. Source data are provided in the Source Data file

To assess whether the observed defect in hematopoiesis could be due to a progenitor-intrinsic effect of Firre deficiency, we performed a competitive chimera transplant assay using an HSC-enriched population. We isolated an HSC-enriched population (lin–Sca1+c-Kit+CD34+/−CD135−) from WT (CD45.2), ∆Firre (CD45.2), and congenic WT (CD45.1), and then separately mixed WT (CD45.2) or ∆Firre (CD45.2) cells at an equal ratio with congenic WT (CD45.1). We then transplanted this cell mixture into lethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice (Supplementary Fig. 6A, B) and assessed the long-term reconstitution ability of WT and ∆Firre HSCs to repopulate blood cell lineages in vivo. We observed that ∆Firre/CD45.2-donors had significant reductions in the frequencies of CD4 and CD8 T cells, B cells, and NK cells in the peripheral blood of recipient mice compared with WT/CD45.2-donors (P = 0.0028, P = 0.0051, P = 0.0114, P = 0.0068, respectively, two-tailed Mann–Whitney U), indicating that ∆Firre-donors were markedly outcompeted at repopulating the blood (Supplementary Fig. 6C). Together, these data are consistent with a progenitor-intrinsic role for Firre in hematopoiesis.

In contrast to the ∆Firre model, mice overexpressing Firre RNA in the WT background (FirreOE) had normal frequencies of CD4, CD8, and B cells, but had a significant reduction in the frequency of NK cells in the peripheral blood compared with control mice (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Fig. 5D). A decrease in the frequency of NK cells in dox-fed Firrerescue mice, where only Firre RNA from the transgene is expressed, was also observed (Supplementary Fig. 7). In the bone marrow of dox-fed FirreOE mice, we did not observe significant changes in the frequencies of HSC, multipotent progenitor (MPP), common myeloid progenitor (CMP), or CLPs compared with control samples (Fig. 3c; Supplementary Fig. 5E). Taken together, these results identify cell type-specific defects during hematopoiesis, whereby alterations of Firre impact the ratios and numbers of particular blood cells produced during hematopoiesis.

Firre RNA has a trans-acting role in vivo

Next, we wanted to further investigate the DNA- and RNA-mediated effects of the Firre locus using a cell type that was dysregulated in the ∆Firre immunophenotyping analysis. We selected to use the CLP as a model, because this was the earliest hematopoietic defect identified and because Firre is highly expressed in this progenitor cell type. Therefore, further investigation could provide insight into the physiological effects of modulating Firre in a progenitor cell population. Because the ∆Firre mouse contains a deletion that removes all potential DNA regulatory elements, the lncRNA, and the promoter (thus removing the act of transcription), this mouse model does not allow us to distinguish between DNA- and RNA-mediated effects.

To directly test whether the decrease in the frequencies of CLPs observed in the ∆Firre mice is mediated by an RNA-based mechanism, we reasoned that overexpressing Firre RNA in the ∆Firre background would enable to test for an RNA-mediated role. To this end, we generated multiple cohorts of mice that contained the FirreOE alleles in the ∆Firre background (Firrerescue) and induced transgenic Firre RNA expression by placing mice on a dox-diet. From multiple cohorts of WT, ∆Firre, and dox-fed Firrerescue mice, we assessed CLP frequency by flow cytometry in total bone marrow and lineage-depleted bone marrow (to enrich for hematopoietic non-lineage committed cells).

Consistent with the previous data (Fig. 3b), we also observed a significant decrease in the frequency of CLPs in total bone marrow from ∆Firre mice (n = 17, mean CLP frequency = 0.0532) compared with WT mice (n = 16, mean CLP frequency = 0.0829) (Fig. 4b) and in lineage-depleted bone marrow from ∆Firre mice (n = 9, mean CLP frequency = 0.3011) compared with WT (n = 9, mean CLP frequency = 0.2167) (Supplementary Fig. 8A, B). In contrast, dox-fed Firrerescue mice which only expressed transgenic Firre RNA, we observed that the frequency of CLPs was significantly increased (n = 15, mean CLP frequency = 0.0810) compared with ∆Firre mice, and restored to approximately that of WT in total bone marrow (Fig. 4b). Consistent with this data, in lineage-depleted bone marrow, we also observed a significant increase in the frequency of CLPs in dox-fed Firrerescue mice (n = 11, mean CLP frequency = 0.2809) compared with ∆Firre mice (Supplementary Fig. 8). Thus, induction of transgenic Firre RNA alone is sufficient to rescue the reduction in frequency of CLPs observed in ∆Firre bone marrow. These data suggest that Firre RNA, rather than DNA, exerts a biological function during hematopoiesis.

Fig. 4.

Transgenic Firre RNA rescues physiological and molecular defects in CLPs. a Schematic of experimental approach. b Frequencies of CLPs as determined by flow cytometry shown as percent of live cells in total bone marrow from 3 to 7 months old WT (n = 16, mean age = 26 weeks), ∆Firre (n = 17, mean age = 23 weeks), and Firrerescue dox diet (n = 15, mean age = 23 weeks) mice over three independent experiments. The data are shown as mean ± SEM, and statistical significance determined by a two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test. c Firre RNA expression in CLPs from WT (n = 4), ∆Firre (n = 4), and dox-treated Firrerescue (n = 4) determined by RNA-seq. The data plotted as transcripts per million (TPM +1) showing the mean ± SEM. d Heatmap showing significantly differentially expressed genes in CLPs in ∆Firre/WT comparison and dox-treated Firrerescue/∆Firre comparison. Color gradient is saturated outside of +/− log2 fold changes. e GO analysis for significantly dysregulated genes in ∆Firre CLPs. f Examples of genes that show significant reciprocal regulation in WT, ∆Firre, and dox-treated Firrerescue CLPs. g Firre locus region (2 Mb) showing gene expression differences in log2 FC between ∆Firre and WT CLPs, mouse embryonic forelimb, and heart. Firre is shown in red, significantly dysregulated genes are shown in red, genes that are not significantly changed are shown in black, and genes that were not detected shown in white. Source data are provided in the Source Data file

Transgenic Firre RNA restores gene-expression programs in vivo

To gain further insight into the molecular roles of Firre in the CLPs, we took a gene expression approach, because alterations of the Firre locus and RNA have previously been shown to impact gene expression15,21,50. Moreover, we reasoned that we could test if changes in gene expression in the loss-of-function model could be rescued by expressing only transgenic Firre RNA. To this end, we isolated CLPs by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) from the bone marrow of age- and sex-matched WT, ∆Firre, and dox-fed Firrerescue mice, and performed poly(A)+ RNA-seq. As expected, Firre RNA was not detected in the ∆Firre samples, and expression of transgenic Firre RNA in the Firrerescue samples was detected at levels above WT (Fig. 4c). Differential gene expression analysis between WT and ∆Firre CLPs identified 89 significantly differentially expressed genes (FDR<0.1) (Fig. 4d; Supplementary Data 9). GO analysis of the differentially expressed genes showed that deletion of Firre in CLPs affected genes involved in lymphocyte activation, cell adhesion, and B-cell activation (Fig. 4e).

Next, we determined if induction of Firre RNA in the Firrerescue model could rescue expression of the 89 significantly dysregulated genes found in ∆Firre CLPs. We compared the CLP RNA-seq from ∆Firre and Firrerescue mice and identified 4656 genes with significant changes in gene expression (FDR<0.1) (Supplementary Data 10). Notably, 78 of the 89 genes that were significantly differentially expressed in ∆Firre CLPs were found to be significantly and reciprocally regulated in Firrerescue CLPs (P = 2.2e-16, Fisher exact test) (Fig. 4d). For example, Ccnd3, Lyl1, and Ctbp1 are significantly downregulated in ∆Firre CLPs, but are found significantly upregulated in Firrerescue CLPs to (Fig. 4f). Further, genes such as Maoa, Fam46c, and Icos were found significantly upregulated in ∆Firre CLPs, but their expression was significantly reduced in Firrerescue CLPs (Fig. 4f). We also noted that several immunoglobin heavy and light-chain variable region genes were reciprocally regulated in our analyses (Fig. 4d). Taken together, these data suggest that ectopic expression of Firre is sufficient to restore a gene expression program in an RNA-based manner in vivo.

The Firre locus does not function in cis

Many lncRNA loci exert function to control the expression of neighboring genes, a biological function called cis-regulation51. This occurs through a variety of mechanisms including, cis-acting DNA-regulatory elements, the promoter region, the act of transcription, and the lncRNA9,10,52–54. The ∆Firre mouse model enables to test for potential cis-regulatory roles for Firre on the X chromosome, because the knockout removes the entire Firre locus and promoter region (Fig. 1d). To investigate local (cis) effects on local gene expression, we generated a 2 Mb windows centered on the Firre locus and examined whether the neighboring genes were significantly dysregulated across nine biological contexts.

Differential gene expression analysis for WT and ∆Firre CLPs showed that of the 12 genes within a 2 Mb window (excluding Firre), none were differentially expressed (Fig. 4g). Consistent with this finding, we did not observe significant changes in local gene expression (2 Mb windows centered on the Firre locus) in seven of the eight embryonic tissues (Fig. 4g; Supplementary Fig. 9A–F). Indeed, we observed one instance of differential expression in one embryonic tissue (Hs6st2 was slightly but significantly downregulated in the embryonic forebrain, −0.38 log2 fold change, FDR<0.05) (Supplementary Fig. 9A–F). These data demonstrate that the Firre locus does not exert a local effect on gene expression in vivo, and suggest that the Firre lncRNA regulates gene expression in a trans-based manner. Collectively, our study investigates the roles of DNA and RNA at the Firre locus in vivo and genetically defines that the Firre locus produces as a trans-acting lncRNA molecule in vivo.

Discussion

Classic models used to study noncoding RNAs—ribosomal RNAs, small nucleolar RNAs, tRNAs, and the telomerase RNA component (TERC)—have demonstrated that RNAs serve important cellular functions. This core of possible RNA biology has been greatly expanded by studies that have identified tens of thousands of lncRNAs32,33,55. Indeed, subsequent molecular and genetic interrogation of lncRNA loci have identified diverse molecular roles and biological phenotypes. However, lncRNA loci can potentially function through multiple molecular modes: DNA-regulatory elements (including the promoter), the act of transcription itself, and the lncRNA gene product. Therefore, attributing an RNA-based role to a lncRNA locus requires the development of multiple genetic models to determine the activities and contributions of potential regulatory modalities12,13,52.

In this study, we developed three genetic models in mice for the syntenically conserved lncRNA Firre: loss-of-function, overexpression, and rescue. Notably, we report that deletion of the Firre locus does not impact survival in mice, or despite escaping XCI, skew the sex ratio of progeny. We leveraged the genetic models to discriminate between DNA- and RNA-mediated effects in vivo. We determined that modulating Firre directs cell-specific defects during hematopoiesis, potentiates the innate immune response upon exposure to LPS, and can restore gene expression programs—all of which have an RNA-based functional modality. We also conclude that the Firre locus does not have a local cis-regulatory effect on gene expression in nine different biological contexts. Together, by using multiple genetic and molecular approaches, we identified that Firre produces a trans-acting lncRNA in a hematopoietic context. There are several important implications for these results.

First, our study indicates that Firre has trans RNA-based activity in vivo, and thus extends reports that have suggested RNA-based roles for Firre in cell culture models25,27,40. By using compound genetic approaches, we found that overexpression of Firre from a transgene in the Firre-deficient background was sufficient to rescue physiological and molecular phenotypes in ∆Firre CLPs in vivo. The rescue of genes found differentially expressed in ∆Firre CLPs by a Firre transgene produced a highly significant result (P = 2.2e-16, Fisher exact test); however, we note that the widespread changes in gene expression observed in the CLPs from animals only expressing transgenic Firre RNA could also formally contribute to this effect. Yet, we speculate that early hematopoietic progenitor cells may represent a unique context to study the role(s) of FIRRE/Firre. In humans, FIRRE is expressed as both circular (circ-FIRRE) and linear forms in hematopoietic cells, and circ-FIRRE is abundant in all progenitor cell types, except for the CLPs56. More studies will be needed to determine how and if Firre RNA is interacting at distal loci as well as assess the functional differences between linear and circular isoforms of Firre in a progenitor cell context.

Second, we observed that overexpression of Firre RNA in an endotoxic shock model potentiated the innate immune response in vivo, and in turn, led to significant viability defects. Consistent with our findings, independent studies have found that overexpression of Firre RNA in different cellular contexts can modulate genes in the innate immune response. For example, the levels of select inflammatory genes, including IL12p40, are increased upon overexpression of Firre RNA followed by LPS stimulation in human SW480 cells27. In addition, upon overexpression of Firre RNA in an injury model using cultured primary microglial cells, TNF-α levels are increased30. The different, yet synergistic approaches (cell-based, ex vivo, and in vivo) provide supporting evidence for an RNA-based role for Firre. In the overexpression approach in this study, we note that the phenotypes could be due to increased levels of Firre in a cell type where it is normally expressed and/or from de novo expression in a cellular context where Firre is not endogenously found. Yet, this strategy may perhaps mimic disease contexts where FIRRE is found overexpressed. We speculate that Firre could be important in setting functional thresholds for cells. For example, FIRRE is not only significantly increased in certain cancers, including, kidney renal cell carcinoma, lung squamous cell carcinoma, and colon adenocarcinoma31, but high levels of FIRRE expression have been significantly associated with more aggressive disease and poor survival in patients with large B-cell lymphoma29.

Finally, our study suggests that Firre does not have a cis-regulatory role on gene expression in vivo. Upon deletion of the Firre locus and its promoter region, we observed global changes in gene expression. Yet, we did not find changes in local gene expression (2 Mb window) at the Firre locus in most embryonic tissues and in CLPs. Thus, potential DNA regulatory elements, the lncRNA, the promoter, and the act of transcription appear to not have regulatory roles on neighboring gene expression in the nine biological contexts (eight embryonic and one cell type) analyzed in this study. Moreover, we observed that deletion of Firre in vivo does not perturb Xist RNA expression in eight embryonic tissues and does not affect random XCI in MEFs, which is consistent with a previous study using cell culture models21. Together, these data are notable because cis-acting mechanisms are speculated to be common feature at lncRNA loci57. While we did not find any evidence for cis-activity at the Firre locus in vivo, a previous study from our group found active DNA elements within the Firre locus using a cell-based enhancer reporter assay in 3T3 cells14. We speculate that these candidate DNA-regulatory elements are likely to regulate the Firre locus rather than neighboring genes, as we did not find evidence that neighboring genes were significantly dysregulated upon deletion of the Firre locus.

In summary, we have developed genetic models to test the DNA- and RNA-mediated effects of the syntenically conserved lncRNA locus, Firre, in vivo. Our findings provide evidence that the Firre lncRNA locus has a role in hematopoiesis that is mediated by a trans-acting RNA, and further highlights the biological importance of lncRNA-based machines in vivo. While this study defines a role for Firre in a hematopoietic context, it is important to note that deletion of Firre perturbed gene expression in a number of tissues, including the brain, where FIRRE has been implicated in a rare human disease28. Therefore, going forward it will be important to use genetic models to investigate the potential role(s) of Firre in a number of different biological and disease contexts.

Methods

Mouse care and ethics statement

Mice used in this study were maintained in a pathogen-specific free facility that is under the supervision of Harvard University’s Institutional Animal Care Committee. We have complied with the ethical regulations for animal testing and research in accordance with Harvard University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Mice used in this study were housed at a density of 2–5 mice per cage containing: Anderson’s Bed (The Andersons, Inc), Enviro-Dri (Shepherd Specialty Papers), compressed 2” × 2” cotton nestlet (Ancare), a red mouse hut (BioServ), automatic watering of reverse osmosis deionized water was chlorinated at 2 ppm, and were fed a regular chow diet (Prolab IsoPro RMH 3000 5P75/76).

Firre mouse strains and genotyping

A previously targeted allele for Firre in JM8 embryonic stem cells (mESC) was generated by sequential targeting where a floxed-neomycin-floxed cassette was inserted at the 5′ end of the Firre locus between nucleotides 4790843 and 4790844 (mm9), and a floxed-hygromycin-floxed cassette was inserted at the 3′ end of the Firre locus between nucleotides 47990293 and 47990294 (mm9)15. mESCs containing both correctly targeted neomycin and hygromycin cassettes (Firrefloxed) were injected into blastocysts (Harvard Genome Modification Facility), and subsequent progeny were screened for the Firrefloxed allele (Jackson Laboratory, 029931). To generate a deletion of the Firre locus in all tissues, female Firrefloxed mice were mated to male B6.C-Tg(CMV-Cre)1Cgn/J mice39 (CMV-Cre) (Jackson Laboratory, 006054). We screened the progeny for the ∆Firre allele by PCR genotyping (described below) for Firre wild-type, knockout (∆Firre), neomycin, hygromycin, and cre alleles (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B). A female containing the ∆Firre and CMV-Cre alleles was subsequently mated to male C57BL/6J mice in order to remove CMV-Cre and to propagate the ∆Firre allele. Progeny were PCR genotyped for Firre wild-type, ∆Firre, and cre alleles. Progeny containing only the ∆Firre allele were backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice for three generations (N3) (Jackson Laboratory, 030038). Mice were inbred by intercrosses by heterozygous and homozygous breeding strategies.

To generate an inducible Firre-overexpressing allele (tg(Firre)) in mice, we cloned a mouse Firre cDNA15 into a Tet-On vector (pTRE2), where the β-globin intron sequence was removed. The construct was verified by Sanger DNA sequencing. Next, we used EcoRI and NheI restriction enzymes to digest the cassette containing the tet-responsive element, CMV minimal promoter, Firre cDNA, and β-globin poly(A) terminator. The digested DNA fragment was purified according to Harvard Genome Modification Facility protocol, and the purified DNA cassette was injected into the pronucleus of C57BL/6J zygotes (Harvard Genome Modification Facility). Progeny were screened for the tg(Firre) cassette by PCR genotyping for the tg(Firre) allele, and male founder mice were identified and individually mated to female C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory, 000664). To overexpress tg(Firre) N2 and N3 generation, females were mated to male B6N.FVB(Cg)-Tg(CAG-rtTA3)4288Slowe/J (rtTA) mice (Jackson Laboratory, 016532) and at the plug date females, and the subsequent progeny were either placed on a normal chow diet or 625 mg/kg doxycycline-containing chow (Envigo, TD.01306) until the experimental end points. A colony of male rtTA mice were maintained by breeding to C57BL6/J females for up to four generations.

Genotyping for mice was performed on tissue biopsies that were mixed with 200 µL of digest buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.3, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mg/mL gelatin, 0.45% NP40, and 0.45% Tween-20 in ddH2O with 10 µg/mL proteinase K) in a 1.5 -mL eppendorf tube, and were incubated for 6–18 h at 54 °C. Next, samples were placed on a heating block at 100 °C for 5 minutes (min) in order to heat inactivate proteinase K. Genotyping was performed by PCR using 2x PCR Super Master Mix (Biotool, B46019) and Quick-Load Taq 2X Master Mix (NEB, M0271L) with the cycling conditions 94 °C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94 °C for 20 s, 55 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 45 s. Primers used for genotyping: Firre wild-type allele, F: GGAGGAGTGCTGCTTACTGG, R: TCTGTGAGCCACCTGAAATG; ∆Firre allele, F: TCACAATGGGCTGGGTATTCTC, R: CCTGGGTCCTCTATAAAAGCAACAG; neomycin, F: GACCACCAAGCGAAACATC, R: CTCGTCAAGAAGGCGATAGAA; hygromycin, F: CGGAAGTGCTTGACATTGGG, R: CGTCCATCACAGTTTGCCAGTG; Cre, F: TAATCCATATTGGCAGAACG, R: ATCAATCGATGAGTTGCTTC; Sry, F: TTGTCTAGAGAGCATGGAGGGCCATGTCAA, R: CCACTCCTCTGTGACACTTTAGCCCTCCGA; tg(Firre) allele, F: TACCACTCCCTATCAGTGA, R: CGGCTTCATCTTCAGTCCTC; and the rtTA allele, F: AGTCACTTGTCACACAACG, R: CTCTTATGGAGATCCCTCGAC. Additional genotyping was performed by Transnetyx using real-time PCR.

Cytokine analysis and in vivo endotoxin challenge

To investigate the cytokine response in vivo, we used two different preparations of LPS from Escherichia coli (E. coli) O111:B4. (Sigma, L2630) and Ultrapure LPS, E. coli O111:B4 (InvivoGen, tlrl-3pelps) and dissolved in 0.9% saline solution (Teknova, S5825). We administered either 0.9% saline or 5 mg/kg broad-acting LPS (Sigma, L2630) by i.p. injection using 30-G insulin syringes (BD, 328411) to two female mice cohorts 8–10 weeks old (WT, ∆Firre, FirreOE no dox, and dox fed FirreOE). We also administered a different preparation of LPS at 5 mg/kg that is TLR4-specific (InvivoGen, tlrl-3pelps) by i.p. injection in mice 5–10 weeks old (WT, FirreOE no dox, and dox fed FirreOE). At 5 h post i.p. injection, mice were euthanized, and peripheral blood was collected by cardiac puncture and allowed to clot for 30 min at room temperature with gentle rotation. After clotting, samples were centrifuged at 1000×g for 10 min at 4 °C, and serum was collected. Cytokine analysis was performed on serum diluted twofold in PBS pH 7.4 (Eve Technologies, Chemokine Array 31-Plex). Measurements within the linear range of the assay are reported.

Endotoxin survival experiments were performed over two independent experiments using mice 9–16 weeks old: WT (mean age = 12.9 weeks), ∆Firre (mean age = 16 weeks), FirreOE no dox (mean age = 13.6 weeks), and dox fed FirreOE (mean age = 13.7 weeks). Saline control group consisting of WT, ∆Firre, and FirreOE mice. In all, 0.9% saline or 5 mg/kg LPS (InvivoGen, tlrl-3pelps) was prepared as described above and administered by i.p. injection, and mice were monitored for moribund survival over 6 days. Mice were housed at a density of 3–5 mice per cage containing: Anderson’s Bed (The Andersons, Inc), Enviro-Dri (Shepherd Specialty Papers), compressed 2” × 2” cotton nestlet (Ancare), and a red mouse hut (BioServ). The following supportive care was provided during the duration of the experiments: hydrogel, a small cup containing powdered diet mixed with water, and a heating pad (5” × 8.6” × 6”) was placed externally on the bottom of the cage (Kobayashi).

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

We generated a digoxigenin-labeled antisense riboprobe by in vitro transcription (Roche, 11277073910) against Firre from a 428 bp sequence (Supplementary Fig. 1C) that corresponds to the 5′ end of the Firre transcript. In situ hybridization was performed on a minimum of three embryos per stage and/or genotype. For whole-mount staining, we fixed embryos in 4% paraformaldehyde for 18 h at 4 °C, followed by three washes in 1× PBS for 10 min at room temperature. We then dehydrated the embryos for 5 min at room temperature in a series of graded methanol solutions (25%, 50%, 75%, methanol containing 0.85% NaCl, and 100% methanol). Embryos were stored in 100% methanol at -20 °C. Next, we rehydrated embryos through a graded series of 75%, 50%, 25% methanol/0.85% NaCl solutions for 5 min at room temperature. Embryos were next washed twice in 1x PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) and treated with 10 mg/mL proteinase K in 1x PBST for 10 min (E8.0, E9.5) or 30 min (E10.5, E11.5, and E12.5). Samples were fixed again in 4% paraformaldehyde/0.2% glutaraldehyde in PBST for 20 min at room temperature, and washed twice in 1x PBST. We then incubated samples in pre-hybridization solution (50% formamide, 5× saline–sodium citrate (SSC) pH 4.5, 50 μg/ml yeast RNA, 1% SDS, 50 μg/ml heparin, and nuclease-free ddH2O) for 1 h at 68 °C, and then incubated samples in 500 ng/mL of Firre antisense riboprobe at 68 °C for 16 h. Post hybridization, samples were washed in stringency buffers and incubated in 100 μg/mL RNaseA at 37 °C for 1 h. Next, samples were washed in 1× maleic acid buffer with 0.1% Tween-20 (MBST) and incubated in Roche Blocking Reagent (Roche, 1096176) with 10% heat-inactivated sheep serum (Sigma, S2263) for 4 h at room temperature. We used an anti-digoxigenin antibody (Roche, 11093274910) at 1:5000 and incubated the samples for 18 h at 4 °C. Samples were washed eight times with MBST for 15 min, five times in MBST for 1 h, and then once in MBST for 16 h at 4 °C. Samples were washed 3x for 5 min at room temperature with NTMT solution (100 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris–HCl (pH 9.5), 50 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween-20, 2 mM levamisole). The in situ hybridization signal was developed by adding BM Purple (Roche, 11442074001). After the colorimetric development, samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and cleared through a graded series of glycerol/1X PBS and stored in 80% glycerol. Embryos were imaged with a Leica M216FA stereomicroscope (Leica Microsystems) equipped with a DFC300 FX digital imaging camera in Leica Application Suite v2.3.4 R2.

RNA-seq in embryonic tissues preparation and analysis

For WT and ∆Firre RNA-seq in embryonic tissues, we dissected tissues (forebrain, midbrain, heart, lung, liver, forelimb, hindlimb, and pre-somitic mesoderm) from E11.5 embryos (44–48 somites) that were collected from matings between either male WT and female Firre+/− or male ∆Firre and female Firre+/− mice. Tissues were immediately homogenized in Trizol (Invitrogen), and the total RNA was isolated using RNeasy mini columns (Qiagen) on a QIAcube (Qiagen). Samples were genotyped for the WT, ∆Firre, and sex alleles. For each tissue, we generated the following libraries: WT male (n = 3), WT female (n = 3), ∆Firre male (n = 3), and ∆Firre female (n = 3). Poly(A)+ RNA-seq libraries were constructed using TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit v2 (Illumina). The libraries were prepared using 500 ng of the total RNA as input, with the exception of the lung (200 ng) and the pre-somitic mesoderm (80 ng), and with a 10-cycle PCR enrichment to minimize PCR artifacts. The indexed libraries were pooled in groups of six, with each pool containing a mix of WT and ∆Firre samples. Pooled libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 in rapid-run mode with paired-end reads.

Reads were mapped to the mm10 mouse reference genome using TopHat v2.1.1 with the flags: "--no-coverage-search --GTF gencode.vM9.annotation.gtf", where this GTF is the Gencode vM9 reference gene annotation available at gencodegenes.org. Cufflinks v2.2.1 was used to quantify gene expression and assess the statistical significance of differences between conditions. Cuffdiff was used to independently compare the WT and ∆Firre samples and from each tissue and sex, and genes with FDR ≤0.05 were deemed significant (Supplementary Data 1–8). Gene Ontology analysis was performed using genes found significantly dysregulated in four or more embryonic tissues using FuncAssociate 3.058.

RNA-seq in CLPs preparation and analysis

We isolated CLPs (Lin–Sca1locKitloIL7Rα+)by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) from mice 27–32 weeks old: WT (n = 4, mean age = 31 weeks), ∆Firre (n = 4, mean age = 30.4 weeks), and Firrerescue +dox (n = 4, mean age = 29.3 weeks. CLPs were directly sorted into TRIzol. RNA was isolated using RNeasy micro columns (Qiagen, 74004) on a QIAcube (Qiagen), and we quantified the concentration, and determined the RNA integrity using a BioAnalyzer (Agilent). Poly(A)+ RNA-seq libraries were constructed using CATS RNA-seq kit v2 (Diagenode, C05010041). Pooled libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 in rapid-run mode with paired-end reads.

The adapter-trimmed reads were mapped to the mm10 mouse reference genome using TopHat v2.1.1 with the flags: “--no-coverage-search --GTF gencode.vM9.annotation.gtf ” (Gencode vM9 reference gene annotation). FeatureCounts v1.6.2 and DESeq2 v1.14.1 were used to quantify gene expression and assess the statistical significance of differences between conditions59,60 and the P-value of comparisons were empirically calculated by using fdrtools v1.2.15 (ref.61). Genes with an FDR ≤0.1 were deemed significant in a comparison between wild-type and ∆Firre (Supplementary Data 9) and genes with an FDR ≤0.1 in the ∆Firre and Firrerescue comparison were deemed significant (Supplementary Data 10). Gene Ontology analysis was performed on significantly differentially regulated genes (FDR ≤0.1) in the WT and ∆Firre CLP comparison using PANTHER62.

qRT-PCR

Embryonic tissues or cells were homogenized in Trizol (Invitrogen), and total RNA was isolated using RNeasy mini columns (Qiagen) on a QIAcube (Qiagen). In total, 300 ng of the isolated RNA was used as input to synthesize cDNA (SuperScript IV VILO Master Mix, Invitrogen, 11756050). Primers used qRT-PCR experiments: F_b-act: GCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCGTG, R_b-act: CACGGTTGGCCTTAGGGTTCAG; F_Firre: AAATCCGAGGACAGTCGAGC, R_Firre: CCGTGGCTGGTGACTTTTTG. Experiments were performed on a Viia7 (Applied Biosciences). qRT-PCR data were analyzed by the ∆∆Ct method63.

Distribution of Firre expression across wild-type tissues

For each of the eight WT embryonic tissues, FPKM estimates of all protein-coding or noncoding genes (biotypes selected: protein coding, lincRNA, and processed transcript) were aggregated and filtered for expression > 1 FPKM. Density and expression plots were generated using ggplot2_2.2.1 (geom_density()) in R version 3.3.3.

Flow-cytometry analysis

Zombie Aqua Fixable Viability Kit (Biolegend, 423101) was used as a live-dead stain, and used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For cell analysis of the peripheral blood, thymus, and bone marrow, age and sex-matched mice were used. Peripheral blood was collected by cardiac puncture or by tail vein collection into 10% by volume 4% citrate solution. The following antibodies were added (1:100) to each sample and incubated for 30 min at room temperature Alexa Fluor 700 anti-mouse CD8a clone 53-6.7 (Biolegend, 100730), PE/Dazzle-594 anti-mouse CD4 clone GK1.5 (Biolegend, 100456), APC anti-mouse CD19 clone 6D5 (Biolegend, 115512), Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse NK-1.1 clone PK136 (Biolegend, 108718), PE anti-mouse CD3 clone 17A2 (Biolegend, 100205), and TruStain FcX (anti-mouse CD16/32) clone 93 (1:50) (Biolegend, 101319). For competitive chimera experiments, Pacific Blue anti-mouse CD45.2 clone 104 (Biolegend, 109820) and PerCP anti-mouse CD45.1 clone A20 (Biolegend, 110726) were also used. Red blood cells were then lysed for 15 min at room temperature using BD FACS Lysing Solution (BD, 349202). Cells were washed twice in 1x PBS with 1% BSA and then resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde or 1x PBS with 0.2% BSA.

Thymi were collected and homogenized in ice cold PBS over a 40-micron filter. The cells were incubated with the following antibodies (1:100) for 30 min at room temperature: Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse CD25 clone PC61 (Biolegend, 102017), PE/Cy7 anti-mouse/human CD44 clone IM7 (Biolegend, 103030), PE anti-mouse TCR β chain clone H57-597 (Biolegend, 109208), APC anti-mouse/human CD45R/B220 clone RA3-6B2 (Biolegend, 103212), eFluor 450 anti-mouse CD69 clone H1.2F3 (Invitrogen/eBioscience, 48069182), Alexa Fluor 700 anti-mouse CD8a clone 53-6.7 (Biolegend, 100730), and PE/Dazzle-594 anti-mouse CD4 clone GK1.5 (Biolegend, 100456). Cells were washed twice in 1x PBS with 1% BSA and then resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde.

Bone marrow was collected from both femurs and tibias (four bones total per mouse) by removing the end caps and flushing with DMEM (Gibco, 11995-073) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, 26140079) and 10 mM EDTA. Cells were then pelleted, resuspended, and passed through a 70-micron filter. The resulting single-cell suspension was then incubated with the following antibodies (1:100) for 60 min on ice: Alexa Fluor 700 anti-mouse CD16/CD32 clone 93 (Invitrogen/eBioscience, 56-0161-82), PE/Cy7 anti-mouse CD127 (IL-7Rα) clone A7R34 (Biolegend, 135014), Alexa Fluor 488 anti-mouse CD117 (c-Kit) clone 2B8 (Biolegend, 105816), PE/Dazzle-594 anti-mouse Ly-6A/E (Sca1) clone D7 (Biolegend, 108138), APC anti-mouse CD34 clone HM34 (Biolegend, 128612), PE anti-mouse CD135 clone A2F10 (Biolegend, 135306), and Pacific Blue anti-mouse Lineage Cocktail (20 μL per 1×106 cells) clones 17A2/RB6-8C5/RA3-6B2/Ter-119/M1/70 (Biolegend, 133310). Red blood cells were lysed for 15 min at room temperature using BD FACS Lysing Solution (BD, 349202) or BD Pharm Lyse (BD, 555899). Cells were washed twice in 1x PBS with 1% BSA and then resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde or 1x PBS with 0.2% BSA.

Flow cytometry was performed on a LSR-II (BD). To enumerate cell populations, 50 μL of CountBright Absolute Counting Beads (Invitrogen, C36950) was added to relevant bone marrow and thymus samples. Gating of cell populations was performed using FlowJo 10.4.1 software (Treestar) using the following criteria (applied to live singlets) (Supplementary Fig. 10): CD4 T cells (CD3+CD4+CD8-CD19-); CD8 T cells (CD3+CD8+CD4-CD19-); NK cells (NK1.1+CD19-CD3-); B cells (CD19+CD3-); double negative (DN) (B220-CD4-CD8-CD25varCD44var); double positive (DP) (CD4+CD8+B220-); single positive (SP) (CD8, CD8+CD4-B220-); single positive (SP) (CD4, CD4+CD8-B220-); hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) (LSK [Lin-], Sca1+, c-Kit+)-CD34+-CD135-); multipotent progenitors (MPP) (LSK[CD34+CD135+]); common lymphoid progenitors (CLP) (Lin-Sca1loc-KitloIL7Rα+); and common myeloid progenitors (CMP) (LK[CD34+CD16/32-]). Negative gates were set using fluorescence-minus-one controls (FMO).

Competitive HSC transplant assay

Bone marrow from age- and sex-matched mice was collected and pooled with like genotypes (as described in flow-cytometry analysis section) from mice that were 8–9 weeks in age: PepBoy/CD45.1 (n = 3 females per experiment; mean age = 9 weeks) (Jackson Laboratory, 002014), Firre WT/CD45.2 (n = 3 females per experiment mean age = 8.9 weeks), and ∆Firre/CD45.2 (n = 3 females per experiment; mean age = 8.6 weeks). Bone marrow was lineage-depleted according to the manufacturer's protocol (MiltinyiBiotec, 130-042-401), and cell marker surface staining was performed (as described for bone marrow in the Flow-cytometry analysis section). Red blood cells were then lysed for 15 min at room temperature using BD Pharm Lyse (BD, 555899). Cells were washed twice in 1x Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) (Gibco, 14025092) with 5% FBS and 2 mM EDTA. We then double-sorted lineage-depleted cells for an HSC-enriched population (Live, Lin-Sca1+c-Kit+CD34+-CD135-) into HBSS with 2% FBS using FACS (BD Aria). Recipient mice, PepBoy/CD45.1 (n = 10 males per experiment; mean age = 8.6 weeks), were lethally irradiated using a split 9.5γ split dose (3 h apart). Firre WT and ∆Firre HSCs were separately mixed at a 1:1 ratio with PepBoy/CD45.1 HSCs. In total, 100 μl containing 4000 mixed cells were transplanted by retro-orbital injection using 30-gauge insulin syringes (BD, 328411) into lethally irradiated recipients. Forty-eight hours post transplant, 100,000 helper marrow cells from male PepBoy/CD45.1 were transplanted by retro-orbital injection into each experimental PepBoy/CD45.1 male recipient mouse. After transplantation, mice were maintained on antibiotic-containing water (0.4% sulfamethoxazole/0.008% trimethoprim) for 4 weeks, and then switched to automatic watering of reverse osmosis deionized water chlorinated at 2 ppm.

MEF preparations and culture

We generated Firre WT, Firre knockout, and Firrerescue MEFs at E13.5 from intercrosses between male Firre-/y with female Firre+/− and male Firrerescue with female Firre−/−. Individual embryos were dissected into 1x phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and were eviscerated, and the head, forelimbs, and hindlimbs were removed. Embryo carcasses were placed into individual 6 cm2 tissue culture plates containing 1 mL of pre-warmed 37 °C TrypLE (Thermo Fisher, 12604013) and were incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. Embryos were dissociated by gently pipetting using a P1000 tip and MEF media was added. Cells were cultured for 5–7 days, and cryostocks of individual lines were generated. Subsequent experiments were performed from thaws from the cryostocks up to passage 3. MEFs were genotyped for Firre WT, knockout, rtTA, tg(Firre), and sry alleles. MEF culture media: 1x Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen 11965-118), 10% FBS (Gibco, 10082139), L-glutamine (Thermo Fisher, 25030081), and penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher, 15140122).

Firre FISH probe design and RNA FISH

Firre oligo probes were designed using Primer3 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/), and synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies. After Amine-ddUTP (Kerafast) was added to 2 pmol of pooled oligos by terminal transferase (New England Biolabs), oligos were labeled with Alexa647 NHS-ester (Life Technologies) in 0.1 M sodium borate. Firre RNA FISH was performed on Firre WT, ∆Firre, and Firrerescue MEFs which were plated at a density of 50,000 cells per well onto round glass coverslips in a 24-well plate. Firrerescue MEFs were cultured with either 2 µg/mL dox (Sigma, D9891) or vehicle (ddH2O) for 24 h. Replicate wells were processed for either RNA FISH or to isolate RNA for Firre induction analysis by qRT-PCR. For RNA FISH, cells grown on glass coverslips were rinsed with 1x PBS and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in 1x PBS for 3 min at room temperature and then washed two times with 1x PBS for 5 min at room temperature. Cells were then dehydrated in a series of increasing ethanol concentrations. Six labeled oligo probes were added to hybridization buffer containing 25% formamide, 2X SSC, 10% dextran sulfate, and 1 mg/mL yeast tRNA. RNA FISH was performed in a humidified chamber at 42 °C for 4 h. Cells were washed three times in 2× SSC, and then were mounted for wide-field fluorescent imaging or dehydrated for STORM imaging. Nuclei were counter-stained with Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies). The following pooled oligos against Firre were used: (1) AGCAGCAAATCCCAGGGGCC, (2) TTCCTCATTCCCCTTCTCCTGG, (3) CCCATCTGGGTCCAGCAGCA, (4) ATCAGCTGTGAGTGCCTTGC, (5) TCCAGTGCTTGCTCCTGATG, (6) GCCATGGTCAAGTCCTGCAT.

Firre DNA/RNA and Xist RNA co-FISH

Primary MEF cells were trypsinzed and cytospun to glass slides. After brief air drying, cells were incubated in PBS for 1 min, CSK/0.5% Triton X-100 for 2 min on ice, and CSK for 2 min on ice. Cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at RT and washed twice in PBS. After dehydrated through series of EtOH washes, cells were subject to hybridization at 37 °C O/N with denatured digoxigenin-labeled Xist probe (50% formamide, 2× SSC, 10% dextran sulfate, 0.1 mg/mL CoT1 DNA). Cells were washed in 50% formamide, 2× SSC at 37 °C, and in 2× SSC at RT, three times each. RNA FISH signal was detected by incubating FITC-labeled anti-digoxygenin antibody (Roche) in 4× SSC, 0.1% Tween-20 at 37 °C for 1 h and followed by washing in 4× SSC, 0.1% Tween-20 at 37 °C three times. Cells were fixed again in 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min and washed twice in PBS. Cellular RNAs were removed by RNase A (Life Technologies) in PBS at 37 °C. After dehydrated through series of EtOH, cells were sealed in hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 2× SSC, 10% dextran sulfate, 0.1 mg/mL CoT-1 DNA) containing Cy3-labeled Firre probe (Fosmid WI-755K22). Chromosomal DNA and probes were denatured at 80 °C for 15 min and allowed to renature by cooling down to 37 °C O/N. Cells were washed in 50% formamide, 2× SSC at 37 °C and in 2× SSC at RT, three times each. Nuclei were counter-stained with Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies). Imaging was performed on a Nikon 90i microscope equipped with a 60X/1.4 N.A. VC objective lens, Orca ER camera (Hamamatsu), and Volocity software (Perkin Elmer). All probes were prepared by nick translation using DNA polymerase I (New England Biolab), DNase I (Promega), and Digoxigenin-dUTP (Roche), or Cy3-dUTP (Enzo Life Sciences).

Skeletal preparations

WT and ∆Firre E18.5 embryos were dissected and eviscerated. Samples were fixed in 100% ethanol for 24 h at room temperature. Embryos were then placed in 100% acetone for 24 h at room temperature and then incubated in staining solution (0.3% alcian blue 8GS (Sigma) and 0.1% Alizarin Red S (Sigma) in 70% ethanol containing 5% acetic acid) for 3 days at 37 °C. Samples were rinsed with distilled water and then placed in 1% potassium hydroxide at room temperature for 24 h. Samples were cleared in a series of incubations with 1% potassium hydroxide in 20%, 50%, and 80% glycerol. Skeletal preparations were placed in 80% glycerol/1x PBS and imaged using a Nikon D7000 camera with a Nikon 28-105 macro lens. Images were captured in the Nikon Electronic Format (NEF), and were processed in the Adobe Camera Raw plugin where exposure and temperature adjustments were applied to all like images.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Martin Sauvageau for providing a Firre clone to generate a riboprobe; Dr. Diana Sanchez for assistance in the mouse facility; Dr. Susan Carpenter, Dr. Kate Pritchett-Corning, and Elektra Robinson for discussions on the LPS study; Joyce LaVecchio and Silvia Ionescu in the HSCRB flow cytometry core for FACS assistance; the Harvard Bauer Core for sequencing; Dr. Marta Melé for initial optimization for RNA-seq analysis; Dr. Rasim Barutcu for discussion on the manuscript; and Dr. Laurie Chen and Dr. Lin Wu at the Harvard Genome Modification Facility. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) General Medical Sciences postdoctoral fellowship award 1F32GM122335-01A1 (to J.P.L.) and support from NIH National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute T32HL007893; NIH postdoctoral fellowship F32AG050395 (to J.M.G.); The Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellowship (105920/Z/14/Z) (to J.C.L); Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to R.A.F); NIH RO1 AG048917 and the Dean’s Initiative Award Program for Innovation Grants in the Basic and Social Sciences (to A.J.W.); and the Institute of Mental Health grant R01MH102416-03 and the NIH Institute of General Medical Sciences grant P01GM099117 (to J.L.R.) J.L.R is the Leslie Orgel Professor of RNA Science and HHMI Faculty Scholar.

Author contributions

Study conceptualization and design: J.P.L., J.C.L., and J.L.R.; Firre ES cell targeting: A.W., J.H., and R.A.F.; transgenic mice generation and mouse husbandry, N.C. and J.P.L.; Immunophenotyping experiments: J.P.L., J.C.L., and J.M.G.; competitive chimera design and analysis: J.M.G., J.P.L., A.J.W.; endotoxic shock experiments: J.P.L., N.C., and C.G.; RNA-sequencing design and analysis: T.H., J.P.L., C.G., W.M., and A.G.; RNA FISH for Firre: H.S. and J.T.L.; funding and supervision: A.J.W. and J.L.R.; writing the paper: J.P.L., J.C.L., and J.L.R. with input from all of the authors.

Data availability

RNA-sequencing data is available at Gene Expression Omnibus under the accession numbers GSE125683 and GSE83631. The data that support the findings of the study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-019-12970-4.

References

- 1.Sauvageau M, et al. Multiple knockout mouse models reveal lincRNAs are required for life and brain development. eLife. 2013;2:1–24. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atianand MK, et al. A long noncoding RNA lincRNA-EPS acts as a transcriptional brake to restrain inflammation. Cell. 2016;165:1672–1685. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elling R, et al. Genetic models reveal cis and trans immune-regulatory activities for lincRNA-Cox2. Cell Rep. 2018;25:1511–1524.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai KMV, et al. Diverse phenotypes and specific transcription patterns in twenty mouse lines with ablated lincRNAs. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotzin JJ, et al. The long non-coding RNA Morrbid regulates Bim and short-lived myeloid cell lifespan. Nature. 2017;537:239–243. doi: 10.1038/nature19346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paralkar VR, et al. Unlinking an lncRNA from its associated cis element. Mol. Cell. 2016;62:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groff AF, Barutcu AR, Lewandowski JP, Rinn JL. Enhancers in the Peril lincRNA locus regulate distant but not local genes. Genome Biol. 2018;19:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13059-018-1589-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groff AF, et al. In vivo characterization of Linc-p21 reveals functional cis-regulatory DNA elements. Cell Rep. 2015;16:2178–2186. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engreitz JM, et al. Local regulation of gene expression by lncRNA promoters, transcription and splicing. Nature. 2016;539:452–455. doi: 10.1038/nature20149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Latos PA, et al. Airn transcriptional overlap, but not its lncRNA products, induces imprinted Igf2r silencing. Science. 2012;338:1469–1472. doi: 10.1126/science.1228110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson KM, et al. Transcription of the non-coding RNA upperhand controls Hand2 expression and heart development. Nature. 2016;539:433–436. doi: 10.1038/nature20128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bassett AR, et al. Considerations when investigating lncRNA function in vivo. eLife. 2014;3:1–14. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feyder M, Goff LA. Investigating long noncoding RNAs using animal models. J. Clin. Invest. 2016;126:2783–2791. doi: 10.1172/JCI84422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hacisuleyman E, Shukla CJ, Weiner CL, Rinn JL. Function and evolution of local repeats in the Firre locus. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:1–12. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hacisuleyman E, et al. Topological organization of multichromosomal regions by the long intergenic noncoding RNA Firre. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014;21:198–206. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J, et al. Evolutionary analysis across mammals reveals distinct classes of long non-coding RNAs. Genome Biol. 2016;17:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0866-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hezroni H, et al. Principles of long noncoding RNA evolution derived from direct comparison of transcriptomes in 17 species. Cell Rep. 2015;11:1110–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horakova AH, Moseley SC, Mclaughlin CR, Tremblay DC, Chadwick BP. The macrosatellite DXZ4 mediates CTCF-dependent long-range intrachromosomal interactions on the human inactive X chromosome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012;21:4367–4377. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barutcu AR, Maass PG, Lewandowski JP, Weiner CL, Rinn JL. A TAD boundary is preserved upon deletion of the CTCF-rich Firre locus. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03614-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darrow, E. M. et al. Deletion of DXZ4 on the human inactive X chromosome alters higher-order genome architecture. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA113, E4504–E4512 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Froberg JE, Pinter SF, Kriz AJ, Jégu T, Lee JT. Megadomains and superloops form dynamically but are dispensable for X-chromosome inactivation and gene escape. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1–19. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07446-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berletch, J. B., Ma, W., Yang, F., Shendure, J. & Noble, W. S. Escape from X inactivation varies in mouse tissues. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005079 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Yang F, et al. The lncRNA Firre anchors the inactive X chromosome to the nucleolus by binding CTCF and maintains H3K27me3 methylation. Genome Biol. 2015;16:52. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0618-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang F, Babak T, Shendure J, Disteche CM. r by RNA-sequencing in mouse. Genome Res. 2010;20:614–622. doi: 10.1101/gr.103200.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fang, H. et al. Trans- and cis-acting effects of the lncRNA Firre on epigenetic and structural features of the inactive X chromosome. Preprint at bioRxiv https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/687236v1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Sun L, et al. Long noncoding RNAs regulate adipogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:3387–3392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222643110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu Y, et al. The NF-κB–responsive long noncoding RNA FIRRE regulates posttranscriptional regulation of inflammatory gene expression through interacting with hnRNPU. J. Immunol. 2017;199:3571–3582. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abe Y, et al. Xq26.1-26.2 gain identified on array comparative genomic hybridization in bilateral periventricular nodular heterotopia with overlying polymicrogyria. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2014;56:1221–1224. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi X, et al. LncRNA FIRRE is activated by MYC and promotes the development of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma via Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019;510:594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.01.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zang Y, Zhou X, Wang Q, Li X, Huang H. LncRNA FIRRE/NF-kB feedback loop contributes to OGD/R injury of cerebral microglial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018;501:131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.04.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan X, et al. Comprehensive genomic characterization of long non-coding RNAs across human cancers. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:529–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cabili M, et al. Integrative annotation of human large intergenic noncoding RNAs reveals global properties and specific subclasses. Genes Dev. 2012;447:27–32. doi: 10.1101/gad.17446611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Derrien T, et al. The GENCODE v7 catalogue of human long non-coding RNAs: analysis of their structure, evolution and expression. Genome Res. 2012;22:1775–1789. doi: 10.1101/gr.132159.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mattioli K, et al. High-throughput functional analysis of lncRNA core promoters elucidates rules governing tissue-specificity. Genome Res. 2019;29:344–355. doi: 10.1101/gr.242222.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Molyneaux BJ, et al. DeCoN: genome-wide analysis of in vivo transcriptional dynamics during pyramidal neuron fate selection in neocortex. Neuron. 2015;85:275–288. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang B, et al. The lncRNA Malat1 is dispensable for mouse development but its transcription plays a cis-regulatory role in the adult. Cell Rep. 2012;2:111–123. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ji P, et al. MALAT-1, a novel noncoding RNA, and thymosin β4 predict metastasis and survival in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 2003;22:8031–8041. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eißmann M, et al. Loss of the abundant nuclear non-coding RNA MALAT1 is compatible with life and development. RNA Biol. 2012;9:1076–1087. doi: 10.4161/rna.21089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwenk F, Baron U, Rajewsky K. A cre-transgenic mouse strain for the ubiquitous deletion of loxP-flanked gene segments including deletion in germ cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:5080–5081. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.24.5080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bergmann JH, et al. Regulation of the ESC transcriptome by nuclear long noncoding RNAs. Genome Res. 2015;9:1336–1346. doi: 10.1101/gr.189027.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo M, et al. Long non-coding RNAs control hematopoietic stem cell function. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:426–438. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cabezas-Wallscheid N, et al. Identification of regulatory networks in HSCs and their immediate progeny via integrated proteome, transcriptome, and DNA methylome analysis. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:507–522. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fink MP, Heard S. Models of sepsis and septic shock. J. Surg. Res. 1990;49:186–196. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(90)90260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hirschfeld M, Ma Y, Weis JH, Vogel SN, Weis JJ. Cutting edge: repurification of lipopolysaccharide eliminates signaling through both human and murine toll-like receptor 2. J. Immunol. 2014;165:618–622. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kellogg RA, Tian C, Etzrodt M, Tay S. Cellular decision making by non-integrative processing of TLR inputs. Cell Rep. 2017;19:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cauwels A, et al. Nitric oxide production by endotoxin preparations in TLR4-deficient mice. Nitric Oxide-Biol. Chem. 2014;36:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tracey KJ, et al. Anti-cachectin/TNF monoclonal antibodies prevent septic shock during lethal bacteraemia. Nature. 1987;330:662–664. doi: 10.1038/330662a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beutler B, Milsark IW, Cerami AC. Passive immunization against cachectin/tumor necrosis factor protects mice from lethal effect of endotoxin. Science. 1985;229:869–871. doi: 10.1126/science.3895437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marino MW, et al. Characterization of tumor necrosis factor-deficient mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:8093–8098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andergassen, D. et al. In vivo Firre and Dxz4 deletion elucidates roles for autosomal gene regulation. Preprint at bioRxiv https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/612440v1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Rinn JL, Guttman M. RNA and dynamic nuclear organization. Science. 2014;345:1240–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.1252966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kopp F, Mendell JT. Review functional classification and experimental dissection of long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2018;172:393–407. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Santoro F, et al. Imprinted Igf2r silencing depends on continuous Airn lncRNA expression and is not restricted to a developmental window. Development. 2013;140:1184–1195. doi: 10.1242/dev.088849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang KC, et al. A long noncoding RNA maintains active chromatin to coordinate homeotic gene expression. Nature. 2011;472:120–124. doi: 10.1038/nature09819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guttman M, et al. Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature. 2009;457:223–227. doi: 10.1038/nature07672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]