Abstract

Case studies can generate hypothesis based on unique clinical patient encounters and provide guidance among populations with limited numbers of patients. However, case studies are not blinded and are susceptible to a variety of factors that can influence study outcomes. One potential solution to minimize this bias is to use an N-of-1 trial. N-of-1 trials are a double-blinded randomized crossover trial within a limited number of patients, often as small as a single patient. These trials borrow many concepts from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which in turn increases the validity of findings compared with a case report. Situations best suited for an N-of-1 trial include chronic disease states and therapies with quick onset and offset, such as in patients with seizures. There are many opportunities to use N-of-1 trials among patients with epilepsy, and providers are encouraged to explore and employ these methods. The purpose of this article was to describe N-of-1 trials along with considerations for conducting, publishing, and evaluating N-of-1 trials.

Keywords: N-of-1, Single-case design, Single patient trial, Epilepsy, Antiseizure drug

Highlights

-

•

The use of N-of-1 trials can minimize bias found in traditional case studies.

-

•

N-of-1 trials are a double-blinded randomized crossover trial within a single patient.

-

•

There are methods and reporting standards to guide the development and interpretation of N-of-1 trials.

1. Introduction

Case studies have an important place in the medical literature. They can generate hypothesis based on unique clinical patient encounters and provide guidance among populations with limited numbers of patients. Case studies are usually a detailed description of one or more patient experiences. However, case studies are not blinded and are susceptible to a variety of factors that can influence study outcomes [[1], [2], [3], [4]]. These include the placebo effect, the patient's desire to please their provider, patient and provider expectations of the therapy, and natural waxing and waning of the condition [[2], [3], [4]]. One potential solution to minimize bias found in case studies is to employ the methods from a single-case design, better known as an N-of-1 trial (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of case studies to N-of-1 trials.

| Study design | Time orientation | Number of measurements | Randomized | Blinded | Control | Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case study | Often retrospective | Limited; based on clinical need | No | No | Possibly | Yes |

| N-of-1 trial | Always prospective | Many | Yes | Yes | Yes | Likely |

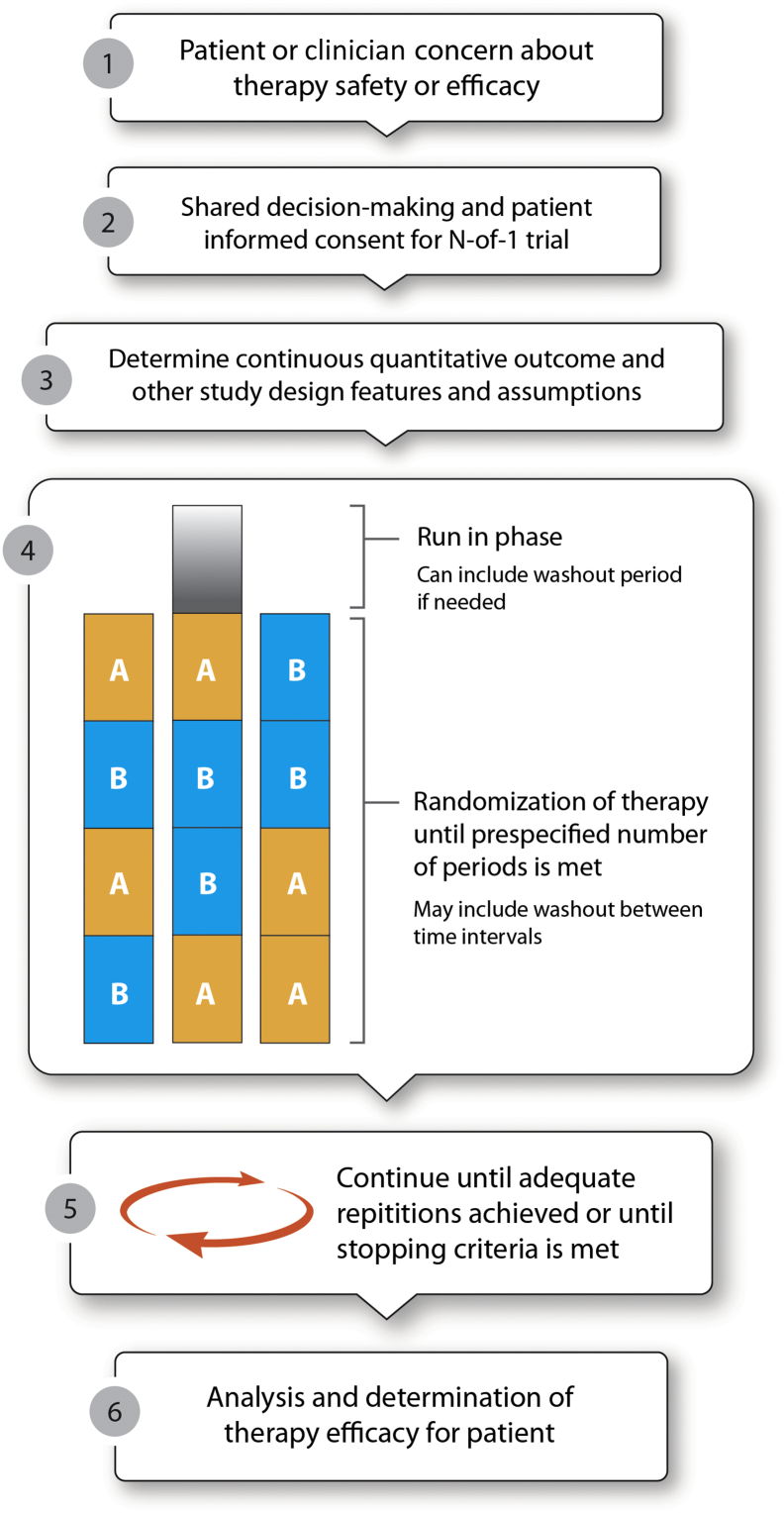

N-of-1 trials are a double-blinded randomized crossover trial within a limited number of patients, often as small as a single patient [[2], [3], [4], [5], [6]]. It can be used to determine if an existing therapy is conferring the intended benefit or used for a trial of a new therapy. In an N-of-1 trial, the patient and provider are typically blinded to the order that therapy is administered. Following a predetermined treatment period, the patient may crossover to the other therapy. This cycle is repeated in a randomly determined pattern with prospective measurement of disease control until the patient response is determined. The general flow of designing and implementing an N-of-1 trial is displayed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Steps for conducting an N-of-1 trial.

While traditional randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide valuable safety and efficacy data for new drug approvals, they are not without limitations, especially in trials evaluating antiseizure drugs. Typically, phase II–III studies of antiseizure drugs involve patients that present with very high monthly seizure frequency. New agents are studied initially as “add-on” therapy, meaning they are given as adjunctive to a patient already receiving other anti-seizure drugs. In addition, patients with other complex medical or psychiatric conditions may not meet typical RCT eligibility criteria. Given these constraints, data from phase III studies may be difficult to extrapolate to other patient populations. An N-of-1 trial can be used in these situations for patients not meeting RCT inclusion criteria if or different comparators are used [3,5,7].

Often an N-of-1 trial will follow a RCT; the RCT demonstrates that a therapy works, on average, for a population. However, N-of-1 trials can determine who the therapy works for and may be considered phase IV research [3]. Despite N-of-1 trials taking place within a small sample, they can still produce a high level of evidence. The Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 levels of evidence lists N-of-1 trials as a high level-1 evidence for intervention-based research, especially when considering a clinical question within an individual patient [8]. This is a similar level of evidence to an RCT. Case studies, however, are considered a lower level of evidence (level 4) given the potential for bias that influences the outcome. For reference, an RCT can be level 1 or 2 evidence and a nonrandomized observational study is a level 3. Additionally, N-of-1 trials are useful for patients already receiving a therapy when either the patient or clinician is unsure of the therapy's effectiveness [5,9]. An example where an N-of-1 trial may be suited is when patients with epilepsy syndromes (e.g., juvenile myoclonic epilepsy) and multiple seizure types are using approved antiseizure drugs but there is a lack of class 1 evidence for the population.

There are two published N-of-1 trials using antiseizure drugs. Privitera and colleagues assessed the efficacy and safety of dezinamide in 15 patients with focal seizures (mix of patients with focal aware and focal impaired awareness seizures) experiencing at least four seizures per month despite phenytoin use [10]. After determining each patient's dezinamide dose, patients were randomized to six 5-week periods in pairs of dezinamide or placebo. At the conclusion of the study, the investigators were able to demonstrate a significant decrease in seizure frequency (37.9%) using two statistical procedures. Gordon and colleagues performed an N-of-1 trial in a single child with “frontally predominant, bilaterally synchronous spike and slow-wave discharges” and a history of tonic–clonic seizure following head trauma who had stopped valproic acid because of hyperactivity and disruptive behavior [11]. There were seven randomized 1-week periods of valproic acid or placebo during the trial. It was determined that valproic acid returned his electroencephalogram (EEG) results to normal and improved his cognitive function in school but worsened hyperactivity. The results were discussed with the patient and caregivers which resulted in continuation of valproic acid. Both cases highlight the potential benefit for the generation of new knowledge and for improved patient care through the use of N-of-1 trials [10,11]. The purpose of this article was to describe N-of-1 trials along with considerations for conducting, publishing, and evaluating N-of-1 trials.

2. Methods for conducting an N-of-1 trial

Before initiating an N-of-1 trial, a determination must be made if the patient is a good candidate. N-of-1 trials are generally best suited for chronic conditions in an outpatient setting (Table 2). As it is a crossover trial, if the condition can be cured, there is no longer an opportunity to test the other therapy. Similarly, considering the efforts that go into conducting an N-of-1 trial, the therapy should be for a chronic condition [2]. There should also be efforts to minimize harm.

Table 2.

Determination that an N-of-1 trial is feasible.

| Question | Determination | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Is treatment efficacy questionable? | If it is clear to the patient and provider that a treatment does or does not work, then an N-of-1 trial is unnecessary. | After dramatic decrease in seizure frequency following the initiation of a new medication, an N-of-1 trial would be unnecessary to determine if therapy should be continued. |

| Is treatment for a chronic condition? | Given the resources needed to conduct an N-of-1 trial, they are only recommended for chronic conditions. | An N-of-1 trial for a single case of status epilepticus is not feasible. |

| Is there a rapid treatment onset and offset? | N-of-1 trials are only reasonable for therapies with quick onset and offset. | An N-of-1 trial with carbamazepine may not be feasible. Levetiracetam is an appropriate therapy for an N-of-1 trial. |

| Can the outcome be measured in a reasonable amount of time? | When taking the duration of a therapeutic trial and the number of trials, it is suggested to try to keep the N-of-1 trial to less than 12 weeks. However, patient willingness to complete the trial will factor into how long the trial can last. | For a patient who averages one seizure per week, a minimum of three weeks is needed to measure therapy efficacy. If an additional week is needed to washout and transfer to a new therapy, this N-of-1 trial would take upwards of 6 months to complete. This may not be considered reasonable by many patients. |

| Can the pharmacy department assist? | Pharmacy departments can often serve as the removed nonblinded individual. | Pharmacy departments can perform the randomization and prepare the therapy and placebo or control to maintain patient and provider blinding. |

| Is the patient interested in an N-of-1 trial? | Shared-decision making with a cognitively intact patient is essential for patient selection in an N-of-1 trial. | It is unethical to give a placebo or control therapy to a patient who has not undergone informed consent. Additionally, if a patient is uninterested in the N-of-1 trial, they will be unlikely to complete the required data collection. |

Once it is determined that the patient is a good candidate for an N-of-1 trial, the therapy must also be evaluated (Table 2). An ideal therapy for an N-of-1 trial has a quick onset and offset [2]. Longer time to therapeutic effect will make the treatment periods and potential washouts unwieldy. Therapy onset and offset must be taken into account when determining the length of the treatment period, including when it is reasonable to measure the outcome of interest. For frequency-based outcomes that may not present daily, the “inverse rule of 3” can be considered: “if an event occurs, on average, once every X days, we need 3 times X days to be 95% confident of seeing at least one event” during the measurement portion of the treatment period [2]. For example, if a patient has a seizure, on average, once every 3 days, the measurement period should be a minimum of 9 days. However, patient and clinician availability to assess treatment efficacy or to cross treatments may also factor into determining the length of the treatment period. Lastly, if efficacy and safety are uncertain, a run-in phase may be used prior to the first trial period.

Determination of both the outcome of interest and how it is operationalized should be agreed upon prospectively by the clinician and the patient (Fig. 1). Outcomes should be based on the patient's symptoms of concern. While it is possible to conduct an N-of-1 trial using a binomial outcome (i.e., yes or no outcomes), continuous and ordinal outcomes are better suited for an N-of-1 design. For instance, if a patient believes a medication is causing heartburn, the patient could rate the severity of their heartburn each evening on a Likert scale of 0 to 7 with 0 being none and 7 being very severe. The size of the scale used (e.g., 4-point versus 7-point scale) can be jointly determined by the patient and provider. Patients and providers may also choose to monitor more than one outcome but should focus on key symptomatic outcomes to minimize the patient documentation burden [12]. For patients with epilepsy, frequency of seizure during the treatment period using a seizure diary may help to determine treatment efficacy. Subjective outcomes are more prone to bias, and blinding of the patient and provider should be considered [[13], [14], [15]]. Biomarkers and physician assessments can also be used but are often less patient-oriented and may introduce logistical travel issues.

Randomization is an essential component to an N-of-1 trial to determine the order of therapy delivery. Often, therapy is delivered in a series of pairs, such as ABAB and ABBA (Fig. 1). While some suggest a coin flip could be used to determine randomization, statistical packages and random number tables and generators are easy resources to identify and use [2,16]. Computer-generated randomization is recommended to minimize any inadvertent bias. Randomization can be performed in a number of ways, each with their own benefits. Simple randomization could be used, but this runs the risk of an unequal number of control and intervention treatment periods. A blocked randomization of two units (i.e., AB or BA) will create equal numbers of intervention and control treatment periods but is more complicated in generating the randomization scheme [6]. Additionally, blocked randomization is potentially easier in unmasking the allocation sequence; if the patient knows that they first received the intervention (maybe through experience of an adverse effect), they will know that the control therapy comes next to complete the block.

Therapeutic trials are typically continued until the prespecified number of trials is completed to determine the patient response to therapy. Lobo and colleagues suggest a minimum of four treatment periods (i.e., two pairs or therapy randomized) to allow for at least three crossover comparisons [6]. This is consistent with a number of published N-of-1 trials which include three pairs of therapy randomized or six treatment periods [4,7,[17], [18], [19]]. When taking the length of the treatment period and the number of preplanned repetitions, some suggest trying to keep an N-of-1 trial to 12 weeks or less [20]. In some cases, the trial can be stopped early if prespecified criteria are met or in cases where the patient decides to end the trial early (i.e., early patient withdrawal from the trial).

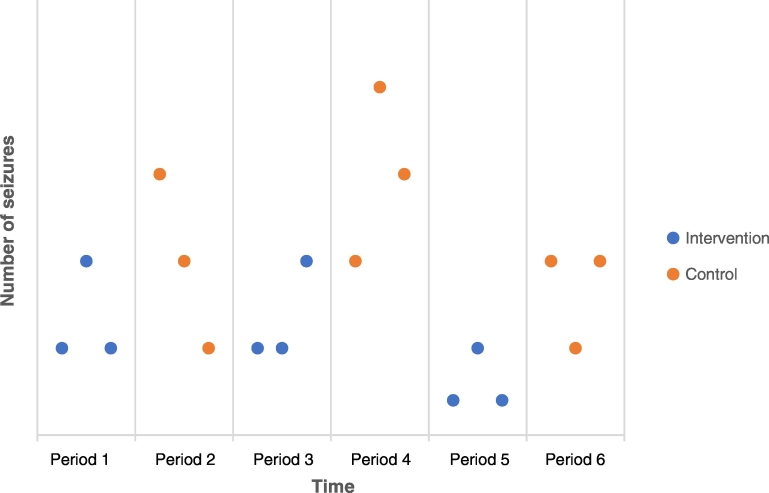

After the trial has been completed, the first step in determining the outcome is to plot the data over time. Sometimes this simple visual review is all that is needed to determine the results of the N-of-1 trial (Fig. 2); however, visual inspection alone has been shown to produce inaccurate conclusions at times [21]. There are more sophisticated visual analysis techniques described by Lobo and colleagues which quantify the results and may minimize errors made compared with using visual review alone [6]. In the case of a successful visual analysis, there are also statistical analyses which have been developed for use in N-of-1 trials. These are also described in Lobo et al. and include an individual-level effect size as well as an across-case effect size.

Fig. 2.

Example visualization from a theoretical N-of-1 trial.

The figure describes a theoretical N-of-1 trial for a patient with treatment-resistant epilepsy. In the example, the intervention (blue) therapy lowers the number of seizures compared with the control (orange) therapy during each pair of therapeutic trials. In this example, depending on the magnitude, the patient and provider may determine that the intervention therapy is beneficial to the control therapy without further visual or statistical analysis.

3. Considerations when using N-of-1 trials

Similarly to an RCT, patients must choose to participate in an N-of-1 trial and understand what the trial entails (Table 2). This is regardless of whether the health system requires formal institutional review board (IRB) approval or not. Likewise, an official informed consent process and documentation is recommended regardless of the need for IRB approval (Fig. 1) [2]. Shared-decision making must first be used to decide if a patient should participate in an N-of-1 trial. Additionally, patients can assist with some design elements of the trial they are undergoing (e.g., the number of treatment periods they are willing to participate in or determining the outcome of interest) [2]. Given the potential for randomization, blinding, and the data collection requirements, patients should be cognitively intact [22].

The need for IRB approval for an N-of-1 trial varies by institution. Before starting an N-of-1 trial, providers should review their IRB policies or seek guidance from an IRB reviewer to see if IRB approval is needed. If IRB approval is needed, this may cause a delay in the initiation of the N-of-1 trial. This information should be considered when deciding if the trial is appropriate and should be conveyed to the patient so they can expect when the investigation can be initiated.

An ideal candidate for an N-of-1 trial will be excited about participating given the additional monitoring they will have to complete [2]. It is important to discuss how the results will be used prior to starting the trial. For instance, the patient should understand that a negative trial (i.e., no discernable difference from placebo) means the therapy in question will be discontinued [3]. However, patients who choose to be in N-of-1 trials typically prefer this approach as they want to determine which therapy works better for them [4,9]. As an additional benefit, many patients who complete N-of-1 trials also find that they learn more about their condition and become more empowered to manage their symptoms.

A common suggestion for conducting an N-of-1 trial is to seek assistance from the pharmacy department [3,5,12]. The pharmacist can randomize the order of therapy administration (i.e., therapy versus placebo) and can blind the medication for both the patient and provider (Table 2). If the institutional pharmacy department cannot accommodate the request, consider seeking out a specialty compounding pharmacy or seeing if the therapy manufacturer can supply placebos. Without the assistance of an independent individual or group, it is impossible to administer double-blinded N-of-1 trial; which is the ideal method to employ for bias minimization.

One of the largest barriers frequently cited by both patients and clinicians regarding the potential implementation of an N-of-1 trial is the additional time needed [20,22]. For the clinician, time is needed to thoroughly discuss the rational of the N-of-1 trial and perform informed consent with a patient, to design and perform the trial, and to measure and analyze the results. Larson and colleagues ran an N-of-1 service and estimated that approximately 17 h was needed per trial [12].

4. Reporting and interpreting N-of-1 trials

The process of reporting and evaluating N-of-1 trials has many similarities to RCTs. Despite the similarities to RCTs, N-of-1 trials have lacked consistency in reporting of results. One study found that 79% of N-of-1 trials did not report the primary outcome and 64% did not assess harms, among other areas of inconsistencies [23]. Criteria aimed at reducing variability in reporting N-of-1 trials (CENT) have been developed by the Consolidated Standards of Reporting (CONSORT), which follows a similar layout to reporting RCTs [24]. This tool serves as a useful starting point for those publishing N-of-1 trials and should be reviewed when designing these studies to ensure that criteria can be met. This portion of the paper will serve as a guide for those wishing to publish or evaluate N-of-1 trials with a focus on seizures. We will go through each portion of the traditional manuscript starting with the title and working towards the conclusion.

Titles should be unbiased, refrain from leading readers to the conclusions, and highlight that an “N-of-1” trial was conducted [24]. This should be followed by an abstract that accurately reflects the main points of the paper. The introduction section introduces the problem being studied, discusses previous pertinent studies, justifies the selection of an N-of-1 trial design, and leads to the purpose of the manuscript. When justifying study selection, it may be helpful to contrast N-of-1 trials with case reports to show the increased rigor associated with this approach. Additional support can be provided by referencing the Oxford Centre levels of evidence document that show N-of-1 trials as being considered level 1 evidence or by highlighting a therapeutic controversy [8]. For example, Gordon et al. justified their N-of-1 trial by discussing how there is a lack of data surrounding the management of cognition in patients experiencing severely epileptiform electroencephalogram (EEG) changes without seizures [11].

The methods section should start with a description of the setting of the trial and timeframe [24]. Subsequently, randomization is described including the number of groups, number of time periods, length of time periods, and what was used to perform randomization (i.e., random number generator). If washout or run-in periods are used, the length of the period and rationale should be described. Rationale should include pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations if a medication is used as the intervention. N-of-1 trials do not need an inclusion/exclusion section if only one patient is enrolled. Instead, the rationale for choosing the patient should be described. For example, in a patient experiencing recurrent seizures, the seizure type(s), frequency, and length of time with the disease state could serve as the rationale for inclusion.

The intervention and control should be described next [24]. The control can be an active control, especially in the case of disease states that can lead to permanent harm. The primary outcome should be stated along with the plan for assessing adverse events. For example, the number of seizures during each time period could serve as a primary outcome. If a tool is utilized in measuring outcomes, reliability and validity need to be described. Additionally, rules around stopping the trial early and interim analyses should be described. Stopping a trial early could occur if patients clearly demonstrate a significant reduction on one seizure medication versus the comparison. Lastly, if blinding was employed, the method used should be described.

After discussion of outcomes, the analytical plan is detailed [24]. Analysis of N-of-1 trials can either be descriptive or analytical and ideally should employ both [6]. Descriptive approaches tend to plot the outcome over time, such as the number of seizures on treatment and on control. Statistical approach choices need to be explained and take into account repeated measures over time. Results should be analyzed using the intention-to-treat principle [25]. Sample size calculations can either reflect the number of periods evaluated in a single patient or the number of patients needed if the intent is to enroll multiple patients. Similar to an RCT, alpha, power, and the effect size are reported. The a priori criteria for success of the intervention should also be reported [18]. Lastly, IRB approval and funding sources should be described if either were obtained.

Results should include a flow diagram to illustrate the number of participants who completed the study and how many patients were lost [24]. A small number of patients being lost or not completing periods can have a significant impact on trial results. For example, in the EEG changes without seizure trial previously mentioned, cognition could not be evaluated during one period because the patient was sick [11]. Fortunately, because multiple periods were employed, this did not have a large effect on the results. If the trial is stopped early, this could also affect findings. If a run-in phase is used, the number of patients that do not complete the run-in phase should be reported along with the reason why they were excluded. If an N-of-1 trial excludes many patients in the run-in phase, this can decrease the generalizability of findings.

Baseline characteristics are typically presented in Table 1 but usually on an individual patient level [24]. For example, in the trial evaluating dezinamide in 15 patients, each patient was described in a separate row with characteristics such as age, seizure type, and number of seizures during the baseline period [10]. Results are often displayed as a figure, with outcomes on the y-axis and time on the x-axis [6,18]. Time should be divided into periods (Fig. 2). For example, one trial evaluating the Feingold diet was able to display the number of seizures during periods when patients were on and off the diet [26]. Interestingly, one of the active diet periods showed more seizures, and it was found that the patient was not adherent to the diet during this period. Lastly, potential harms should be described [24]. The discussion section of the paper mimics other manuscripts. This can be divided into paragraph themes in the following order: summarizing results, comparing and contrasting results with other trials, study implications, limitations, and conclusion.

Most journals do not have guides for N-of-1 trial submissions in their instructions for authors. Therefore, before submitting an N-of-1 trial to a journal, a quick search should be conducted to determine if the journal accepts these manuscripts. When searching a journal, N-of-1 trials may be listed as “single case design”, “single patient trial”, “N of 1”, or “N-of-1”. Unfortunately, N-of-1 trials do not have a medical subject heading (MeSH) on Pubmed. Authors could also communicate with the editorial board and provide the CENT recommendations if editors are unfamiliar with study design [24]. If a journal accepts case reports, they should also accept N-of-1 trials.

5. Conclusion

Case studies have a long history of stimulating further research that has led to changes in practice. N-of-1 trials expand upon case study designs by utilizing methodologic concepts from RCTs, which in turn increases the validity of findings compared with a case report. N-of-1 trials may be especially useful for patients with pharmacoresistant seizures or patients with rare epilepsy syndromes; providers who serve these patients are encouraged to explore and employ N-of-1 trials. Publication of these trials can facilitate discussion and research to further improve patient care. When preparing to publish, the CENT guidelines serve as an excellent reference tool and will help standardize reporting and improve evaluation by readers.

Ethical statement

As this is a review article, no IRB review was necessary.

Declaration of competing interest

This manuscript is not under consideration by any other journal. The authors have no financial interests to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Sally Griffith-Oh for assistance with graphic design and Barry Gidal for a review of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Amanda Margolis, Email: Amanda.Margolis@wisc.edu.

Christopher Giuliano, Email: ek2397@wayne.edu.

References

- 1.Mahon J., Laupacis A., Donner A., Wood T. Randomised study of n of 1 trials versus standard practice. BMJ. 1999;312:1069–1074. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7038.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guyatt G., Sackett D., Adachi J., Roberts R., Chong J., Rosenbloom D. A clinician's guide for conducting randomized trials in individual patients. CMAJ. 1998;139:497–503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guyatt G., Sackett D., Taylor D., Chong J., Roberts R., Pugsley S. Determining optimal therapy--randomized trials in individual patients. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:889–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198604033141406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nikles J.C., Glasziou P.P., Del Mar C.B., Duggan C.M., Clavarino A., Yelland M.J. Preliminary experiences with a single-patient trials service in general practice. Med J Aust. 2000;173:100–103. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb139254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsapas A., Matthews D.R. N of 1 trials in diabetes: making individual therapeutic decisions. Diabetologia. 2008;51:921–925. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-0983-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lobo M.A., Moeyaert M., Cunha A.B., Babik I. Single-case design, analysis, and quality assessment for intervention research. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2017;41:187–197. doi: 10.1097/NPT.0000000000000187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guyatt G., Keller J., Jaeschke R., Rosenbloom D., Adachi J., Newhouse M. The n-of-1 randomized controlled trial: clinical usefulness. Our three-year experience. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:293–299. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-4-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howick J., Chalmers I., Glasziou P., Greenhalgh T., Heneghan C., Liberati A. 2011. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine 2011 levels of evidence. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikles C., Clavarino A., Del Mar C. Using n-of-1 trials as a clinical tool to improve prescribing. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:175–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Privitera M.D., Treiman D.M., Pledger G.W., Sahlroot J.T., Handforth A., Linde M.S. Dezinamide for partial seizures: results of an n-of-1 design trial. Neurology. 2012 doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.8.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon K., Bawden H., Camfield P., Mann S., Orlik P. Valproic acid treatment of learning disorder and severely epileptiform electroencephalogram without clinical seizures - a double-blind, randomized, N of 1 clinical-trial. Ann Neurol. 1990;28:423. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larson E.B., Ellsworth A.J., Oas J. Randomized clinical trials in single patients during a 2-year period. JAMA. 1993;270:2708–2712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hróbjartsson A., Thomsen A.S.S., Emanuelsson F., Tendal B., Rasmussen J.V., Hilden J. Observer bias in randomized clinical trials with time-to-event outcomes: systematic review of trials with both blinded and non-blinded outcome assessors. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:937–948. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Odgaard-Jensen J., Vist G.E., Timmer A., Kunz R., Akl E.A., Schünemann H. Randomisation to protect against selection bias in healthcare trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000012.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feys F., Bekkering G.E., Singh K., Devroey D. Do randomized clinical trials with inadequate blinding report enhanced placebo effects for intervention groups and nocebo effects for placebo groups? Syst Rev. 2014;3 doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J., Shin W. How to do random allocation (randomization) Clin Orthop Surg. 2014;6:103–109. doi: 10.4055/cios.2014.6.1.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel A., Jaeschke R., Guyatt G., Keller J., Newhouse M. Clinical usefulness of n-of-1 randomized controlled trials in patients with nonreversible chronic airflow limitation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:962–964. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.4.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guyatt G., Heyting A., Jaeschke R., Keller J., Adachi J., Roberts R. N of 1 randomized trials for investigating new drugs. Control Clin Trials. 1990;11:88–100. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(90)90003-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nikles C.J., Mitchell G.K., Del Mar C.B., Clavarino A., McNairn N. An n-of-1 trial service in clinical practice: testing the effectiveness of stimulants for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2006;117:2040–2046. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nikles J., Mitchell G.K., Clavarino A., Yelland M.J., Del Mar C.B. Stakeholders' views on the routine use of n-of-1 trials to improve clinical care and to make resource allocation decisions for drug use. Aust Health Rev. 2010;34:131–136. doi: 10.1071/AH09654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rochon J. A statistical model for the “N-of-1” study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990 doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90139-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kravitz R.L., Paterniti D.A., Hay M.C., Subramanian S., Dean D.E., Weisner T. Marketing therapeutic precision: potential facilitators and barriers to adoption of n-of-1 trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30:436–445. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Punja S., Bukutu C., Shamseer L., Sampson M., Hartling L., Urichuk L. N-of-1 trials are a tapestry of heterogeneity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;76:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vohra S., Shamseer L., Sampson M., Bukutu C., Schmid C.H., Tate R. CONSORT extension for reporting N-of-1 trials (CENT) 2015 statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;76:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shamseer L., Sampson M., Bukutu C., Schmid C.H., Nikles J., Tate R. CONSORT extension for reporting N-of-1 trials (CENT) 2015: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;76:18–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haavik S., Altman K., Woelk C. Effects of the feingold diet on seizures and hyperactivity: a single-subject analysis. J Behav Med. 1979 doi: 10.1007/BF00844740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]