Abstract

Background

Developers of medicines-related apps collect a variety of technical, health-related, and identifying user information to improve and tailor services. User data may also be used for promotional purposes. Apps, for example, may be used to skirt regulation of direct-to-consumer advertising of medicines. Researchers have documented routine and extensive sharing of user data with third parties for commercial purposes, but little is known about the ways that app developers or “first” parties employ user data.

Objective

We aimed to investigate the nature of user data collection and commercialization by developers of medicines-related apps.

Approach

We conducted a content analysis of apps’ store descriptions, linked websites, policies, and sponsorship prospectuses for prominent medicines-related apps found in the USA, Canada, Australia, and UK Google Play stores in late 2017. Apps were included if they pertained to the prescribing, administration, or use of medicines, and were interactive. Two independent coders extracted data from documents using a structured, open-ended instrument. We performed open, inductive coding to identify the range of promotional strategies involving user data for commercial purposes and wrote descriptive memos to refine and detail these codes.

Key Results

Ten of 24 apps primarily provided medication adherence services; 14 primarily provided medicines information. The majority (71%, 17/24) outlined at least one promotional strategy involving users’ data for commercial purposes which included personalized marketing of the developer’s related products and services, highly tailored advertising, third-party sponsorship of targeted content or messaging, and sale of aggregated customer insights to stakeholders.

Conclusions

App developers may employ users’ data in a feedback loop to deliver highly targeted promotional messages from developers, and commercial sponsors, including the pharmaceutical industry. These practices call into question developers’ claims about the trustworthiness and independence of purportedly evidenced-based medicines information and may create a risk for mis- or overtreatment.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-019-05214-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

BACKGROUND

Smartphones are increasingly ubiquitous, and apps related to medicines are widely used by clinicians and consumers. A survey of UK clinicians found the majority used apps in their clinical practice, including drug formularies, dose calculators, and drug preparation and administration, and found them very helpful.1 The accessibility and portability of mobile apps pose an opportunity for improving medication adherence, and there are several thousand such apps available to consumers, though there is concern about their quality and relevance.2

In 2011, a New York Times investigation revealed that a popular, free application (app), Epocrates, used by clinicians to look up information on drug dosing, interactions, and insurance coverage presented users with highly targeted advertisements from pharmaceutical companies.3 The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes that pharmaceutical industry promotion is a public health concern due to its impacts on the cost, quality, and safety of healthcare and provides a code of conduct detailing ethical criteria for drug promotion.4 However, this document dates from 1988 and needs updating to account for promotional activities occurring through novel technologies such as mobile apps.5 Digital platforms, for example, allow for interactive direct-to-consumer advertising, soliciting information about the consumer while delivering promotional and other messaging that prompts the consumer to self-diagnose, request a particular medication, or fill a prescription.6 Such practices represent an insidious form of direct-to-consumer advertising and in some countries, may allow companies to skirt regulation.

User data collected from medicines-related mobile apps may be particularly valuable to commercial interests and thus, vulnerable to privacy and security risks.7 Researchers have focused on privacy and security risks stemming from the sharing and aggregation of user data among third parties8–11 or vulnerabilities of apps to malicious hacking.12, 13 We previously conducted a traffic analysis of data transmitted from 24 medicines-related apps to the network, finding the majority of apps shared user data with third parties and that this data could be further shared, aggregated, and potentially re-identified, within the wider mobile ecosystem.14 However, in our analysis, 50% of sampled apps transmitted user data to the developer or parent company, termed “first parties.” Among these 12 apps, 83% (10/12) transmitted unique identifiers such as Android ID; 58% (7/12) health-related data such as medication lists, symptoms, or conditions; and 17% (2/12) personally identifying information such as name or birthdate.14 Analyses of health app privacy policies suggest there is little transparency around user data collection and sharing.12, 15–17 Thus, the reasons that app developers collect user information and the way it is used, particularly for commercial purposes, are largely unknown. We aimed to investigate the nature of user data collection, analysis, and commercialization by developers of prominent medicines-related apps and the implications for app users.

METHODS

We conducted a content analysis of apps’ store descriptions, developers’ websites, privacy and editorial policies, and investor or advertiser prospectuses, where available. The methods are reported in accordance with the COREQ reporting guidelines.18

Sampling

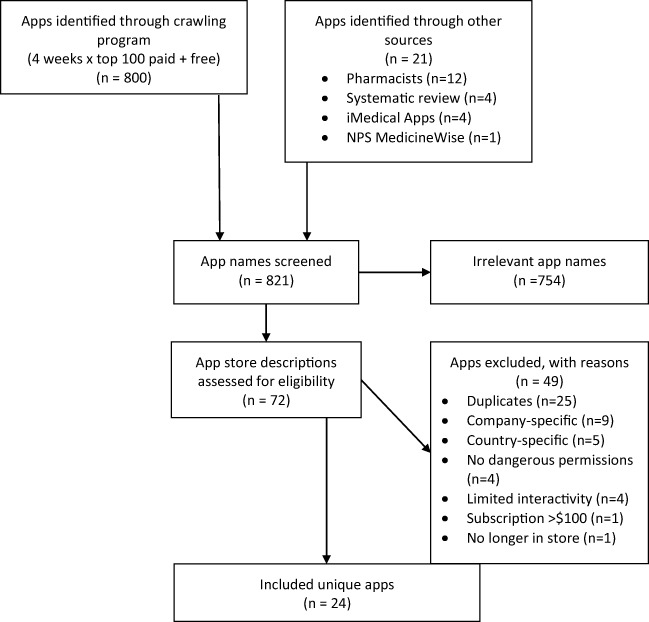

Using a crawling program, we identified the top 100 paid and free apps in the Medical store category of the USA, UK, Canada, and Australia Google Play app stores on a weekly basis from October 17 to November 17, 2017, and hand-searched a systematic review of medicines-related apps,19 and the iMedical app library; our network of practicing pharmacists reviewed the list for omissions. Figure 1 displays the app screening process and reasons for exclusion. Apps were included if they:

Pertained to medicines management, adherence, or information

Were available to Australian consumers using the Android platform

Requested at least one “dangerous” permission, as defined by Google Play20

Required user input in their functionality

Figure 1.

Sampling flow diagram for prominent medicines-related apps.

Data Collection and Analysis

Using an author-generated open-ended form in RedCap,21 two investigators independently extracted data related to the company characteristics, mission, main activities, data-sharing partnerships, and privacy practices verbatim. For each app, we extracted data from the app store description, and if available, the developer’s website, privacy policy, terms and conditions, and investor or advertiser prospectuses. Data were extracted between February 1, 2018, and July 15, 2018. Any discrepancies were resolved through consensus or consolidation, taking the more recent information as accurate.

All documents were imported into NVivo 12 (QSR International). QG performed open, inductive coding on all unstructured data related to app developers, developing two groups of codes: codes related to main activities and company mission, and codes related to user data collection, analysis, or commercialization. QG wrote descriptive memos providing an overview of each group of codes, guided by the questions: whether, how, and to what end do app developers employ user data? The authorship team reviewed these memos, discussing and revising the coding scheme until all codes and data were accounted for. This resulted in final coding scheme used to categorize the developers’ main activities, and another documenting developers’ promotional strategies, both in relation to user data. QG then re-coded the unstructured data using the final coding scheme and wrote memos including detailed qualitative findings with illustrative quotations. To provide context and to further demonstrate the nature and range of promotional strategies, QG calculated frequencies on privacy practices and the set of final codes. KC independently verified the frequencies. The authorship team again reviewed and finalized the coding scheme, which formed the basis for organizing our results and tables.

RESULTS

Table 1 describes app and developer characteristics for the 24 included apps. We thematically categorized apps into two groups based on developers’ main activities and company missions: apps primarily targeted at consumers and focused on medication adherence and apps primarily targeted at clinicians and focused on practice supports.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Apps and Developers (n = 24)

| App (version no.) | No. of downloads | Type | Developer (parent company) | Type of developer | Developer country | Free/paid | Hosts adsa | In-app purchasesa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ada – Your Health Companion (2.10.0) | 1,000,000–5,000,000 | Information | Ada Health | Private company | Germany | Free | No | No |

| CredibleMeds Mobile (2.9.6) | 5000–10,000 | Information | Arizona Center for Education and Research on Therapeutics | Not-for-profit | USA | Free | No | No |

| Dental Prescriber (3.3) | 500–1000 | Information | Dental Sciences Australia Party Ltd | Individual | Australia | Paid | No | No |

| Dosecast - Medication Reminder (5.12) | 100,000–500,000 | Adherence | Montuno Software, LLC | Private company | USA | Free | No | Yes |

| DrugDoses for Android (5.5) | 1000–5000 | Information | DrugDoses | Individual | USA | Paid | No | Yes |

| Drugs.com Medication Guide (2.0.7.40) | 1,000,000–5,000,000 | Information | Drugs.com | Private company | New Zealand | Free | Yes | Yes |

| Epocrates Plus (17.7.3) | 1,000,000–5,000,000 | Information | Epocrates Inc. (AthenaHealth, Inc) | Publicly traded company | USA | Subscription | No | No |

| Lexicomp (4.0.1) | 100,000–500,000 | Information | Lexi-Comp, Inc. (Wolters Kluwer) | Publicly traded company | USA | Subscription | No | No |

| ListMeds – Free (1.16.170531) | 50,000–100,000 | Adherence | Fourth Career Solutions | Individual | USA | Free | Yes | No |

| Med Helper Pro Pill Reminder (2.7.6) | 5000–10,000 | Adherence | Manyeta | Private company | Canada | Paid | No | No |

| MedAdvisor (4.7.0) | 100,000–500,000 | Adherence | MedAdvisor | Publicly traded company | Australia | Free; pharmacist activated | No | No |

| MedicineWise (3.0.3) | 50,000–100,000 | Adherence | NPS MedicineWise | Not-for-profit | Australia | Free | No | No |

| MediTracker (1.7.1) | 1000–5000 | Adherence | Precedence Health Care | Private company | Australia | Subscription | No | Yes |

| Medscape (4.3) | 5,000,000–10,000,000 | Information | Medscape (WebMD, LLC, Internet Brands) | Publicly traded company | USA | Free | Yes | No |

| MedSmart Meds & Pill Reminder App (1.32) | 500–1000 | Adherence | Talking Medicines | Private company | UK | Free | No | No |

| MIMS For Android (2.0.10) | 10,000–50,000 | Information | MIMS For Android | Publicly traded company | Australia | Subscription | No | No |

| My PillBox (Meds & Pill Reminder)+ (1.42)b | 100,000–500,000 | Adherence | Master B | Individual | China | Free | Yes | No |

| MyMeds (5.3.6) | 1000–5000 | Adherence | MyMeds, Inc. | Private company | USA | Free | No | No |

| myPharmacyLink (1.3.2) | 500–1000 | Adherence | GuildLink Pty Ltd. (Pharmacy Guild of Australia) | Private company | Australia | Free; pharmacist activated | No | No |

| Nurse’s Drug Handbook (2.3.1.380) | 100,000–500,000 | Information | Atmosphere Apps (USBMIS) | Private company | USA | Subscription | No | Yes |

| Nurse’s Pocket Drug Guide 2015 (8.0.250) | 5000–10,000 | Information | MobiSystems | Private company | USA | Subscription | Yes | Yes |

| Pedi Safe Medications (3.4) | 5000–10,000 | Information | iAnesthesia LLC | Private company | USA | Paid | No | No |

| Pill Identifier and Drug list (3.5) | 100,000–500,000 | Information and Adherence | Mobixed, LLC (B3Net) | Private company | USA | Free | Yes | No |

| UpToDate for Android (2.28.1) | 500,000–1,000,000 | Information | UpToDate Inc. (Wolters Kluwer) | Publicly traded company | USA | Subscription | No | No |

aAs of July 2018 as reported in Google Play

bNo longer available in Google Play

A total of 42% (10/24) primarily provided mobile services related to medication management such as mobile medication lists, pill reminders and identifiers, or prescription refills. The core theme among these apps’ promotional messages was the positive value placed on the ability to share collected data with the developer, across devices, with caregivers, or with trusted health professionals. One developer, Talking Medicines, encouraged users to share as much health information as possible: “The more information you provide for your profile, medicines and health conditions, the more MedSmart can help you take control of your medicines and your health.”

A total of 58% (14/24) primarily provided drug or medical information on a mobile platform, including clinician drug guides, symptom checkers, and prescribing support. The core theme among apps providing medicines-related information was that they were “evidence-based.” Developers promoted their apps as “trusted,” “objective,” “unbiased,” and “impartial” sources of drug information. A number of developers, including Lexicomp, UpToDate LLC, and Drugs.com, specifically emphasized their independence from pharmaceutical companies.

The Nature of User Data Collection and Sharing

A total of 92% (22/24) of the apps had a privacy policy; however, only 38% (9/24) were specific to the app, 46% (11/24) addressed the developer’s multiple apps or platforms, and 8% (2/24) applied to the company in general. Twenty-nine percent (7/24) of apps’ privacy policies mentioned compliance with privacy legislation (e.g., European Union General Data Protection Rules (GDPR)).

Developers described collecting information that users actively provided through registering, or using the app (including name, email address, clinical specialty, medication lists, or symptoms). Developers also collected user information automatically using third-party analytics services (e.g., Google Analytics), cookies, and “various tracking methods” (including date and time of use, IP address, location, or unique mobile device ID). Developers distinguished among personally identifying information, which could be used to identify and/or contact a specific user (e.g., name); “pseudonymous” information, which could be used to uniquely identify a user, but not by name (e.g., advertising identifiers); and anonymous user information reported in aggregate.

Commonly, developers (58%, 14/24) collected user data for the purpose of “analytics” in order to understand how the app was being used and to optimize and tailor content. Thirty-three percent (8/24) of developers explicitly stated that users’ identifying information would not be sold to third parties. However, analysis of developer websites, privacy policies, and investor and advertiser prospectuses identified a range of promotional strategies involving users’ data (Table 2). The majority of developers (71%, 17/24) reported employing at least one promotional strategy, designed for commercial purposes, which we categorized as follows: marketing the developer’s own products and services; advertising revenue; sponsorship revenue; commercializing customer “insights”; licensing the app; and exclusive “supply agreements” (Table 3).

Table 2.

Range of Promotional Strategies Involving User Data

| Promotional strategy | Commercial purpose | Description | Type of user data collected | Method of user data collection | Nature of consent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emails, newsletters, or push notifications | Marketing the developer’s products or services | Developers targeted individual users with tailored content or “relevant” promotions using user-provided contact information and on the basis of user characteristics |

Identifiers Pseudonymous |

User provided | “Opt-out” through unsubscribing |

| Banner or interstitial ads | Advertising revenue | Developers integrated an ad library in their app’s program; users were automatically served ads on the basis of user and usage analytics (e.g., location); the ad network pays the developer based on advertising metrics10 | Pseudonymous | Tracking technologies | App identified with “contains ads”11 |

| Native ads | Advertising revenue | Developers sold advertising space embedded within app or website content (e.g., sponsor-developed articles, ads within a feed)11; developers sometimes provided advertisers with usage analytics related to the performance of their ads |

Pseudonymous Aggregated |

Tracking technologies | App identified with “contains ads”11 |

| Sponsored content | Sponsorship | Developers and sponsors mutually agreed upon the content’s topic; content was created in accordance with the developer’s editorial policies and the sponsor had no control over the content; developers sometimes provided sponsors with usage analytics related to the content |

Pseudonymous Aggregated |

Tracking technologies | Designated by labels such as “funded by” or “sponsored by” and identifies the sponsor |

| Sponsored messaging | Sponsorship | Sponsors paid fees to sponsor targeted messaging (e.g., adherence messages) that was served to particular groups based on user characteristics; typically, developers and sponsors mutually agreed upon the message’s topic but the developer had control over the content of the messaging |

Pseudonymous Aggregated |

Tracking technologies | “Opt-out” through unsubscribing |

| Customized branding | Licensing | Pharmacies paid a license fee to the developer and could customize the app to their branding; the app is activated by a pharmacist and encourages repeat business through prescription re-fill reminders, for example | Identifiers | User provided | Implied through use of app |

| Data as a product | User insights “shared” with third-parties | Developers generated analyses of user characteristics and behaviors and shared these with third parties; reports ranged from anonymous and aggregated analyses to analyses including identifiers (though not contact information) |

Identifiers Pseudonymous Aggregated |

User provided Tracking technologies |

Implied through use of app |

| Product placement | Exclusive “supply agreements” or subscription fees for premium listings | Developer agreed the sponsor’s brand would be the only one represented in the app within that product category or accepted subscription fees for prominent placement of branded product within the app | N/A | N/A | Not identified |

Table 3.

Illustrative Examples of Commercialization of User Data (n = 24)

| Commercial purpose | Number of apps (%)a | Illustrative quotations (app, developer) |

|---|---|---|

| Marketing developer’s products and services | 9 (38%) |

“We may use your Personal Data to contact you with newsletters, marketing or promotional materials and other information only if you have opted-in. You may opt-out of receiving any, or all, of these communications from us by following the unsubscribe link or instructions provided in any email we send.” (Drugs.com Medication Guide, Drugs.com, bold in original) “for our own marketing, promotional, and informational purposes, including sharing with contracted third parties to assist with our own marketing efforts (all contracted third parties must agree not to use your personal information other than to fulfill their responsibilities to us).” (Epocrates Plus, Epocrates, Inc., bold in original) |

| Advertising revenue | 7 (29%) |

“These third parties may also obtain anonymous information about other applications you have downloaded to your mobile device, the mobile websites you visit, your non-precise location information (e.g., your zip code), and other non-precise location information in order to help analyze and serve anonymous targeted advertising on the Application and elsewhere.” (ListMeds – Free, Fourth Career Solutions) “We use cookies, Web beacons and other similar automated tracking technologies to show targeted ads of our services on your device(s). These ads are more likely to be relevant to you because they are based on inferences drawn from location data, web viewing data collected across non-affiliated sites over time, and/or other application use data. This is called “Interest-based Advertising”.” (UpToDate for Android, Wolters Kluwer Health | UpToDate) “Drugs.com is NOT affiliated with any pharmaceutical companies. The only funding we receive from pharmaceutical companies is by way of advertisements that appear on the Drugs.com website.” (Drugs.com Medication Guide, Drugs.com) “We give you [advertisers] access to the largest community of active physicians and HCPs [health care professionals] across all specialties and we leverage our deep-scale data to reach the exact audience you want to engage.” (Medscape, WebMD, LLC) |

| Sponsorship revenue | 4 (17%) |

Sponsorship “allows us to provide certain content at no additional cost to our members. In addition, we believe that third parties have information that is relevant and valuable to clinicians. Therefore, we also provide opportunities for third parties to market their own products and services or distribute their own content to our network through a variety of mechanisms within our Services.” (Epocrates Plus, Epocrates, Inc.) Pharmaceutical companies are “utilizing MedAdvisor’s platform to ensure their drugs are taken appropriately through training and adherence campaigns aimed only at those using their drugs.” (MedAdvisor, MedAdvisor) |

| Commercializing customer insights | 3 (13%) |

“With global ambition MedSmart® offers unique patients insights from how medicines are used in the real world to healthcare stakeholders including Pharmaceutical Companies.” (MedSmart Meds & Pill Reminder App, Talking Medicines) “GuildLink also uses the information for market research, project planning, troubleshooting, detecting and protecting against error, fraud and other criminal activities, statistical analysis and reporting on trends in pharmacy related service delivery, for analysis and reporting to government on health and health related trends, to evaluate the effectiveness, efficacy and value of myPharmacyLink and for providing commercial services. GuildLink sells reports of aggregated de-identified information about these matters to third parties.” (myPharmacyLink, GuildLink Pty Ltd) |

| Licensing the app | 2 (8%) | “myPharmacyLink is white labeled, meaning it’s fully customisable to your pharmacy’s branding. As soon as your patient activates the app, it will display your branding and your pharmacy’s details. The app is only linked to your pharmacy, so your trusted relationship with the patient is reinforced every time they interact with you through the app.” (myPharmacyLink, GuildLink Pty Ltd) |

| Exclusive “supply agreements” | 1 (4%) | “GSK’s brand Panadol Osteo is granted exclusive access to be the only paracetamol based product to engage with MedAdvisor Platform users in [MedAdvisor Training and Adherence Communications] MTAC services. GSK pays MedAdvisor based on a number of products that utilize the MTAC services of the Platform. The agreement is for an initial two year term with GSK holding an option to extend for a further one year.” (MedAdvisor, MedAdvisor) |

aPercentages do not add to 100% as some apps used multiple strategies

“For Our Own Marketing Purposes”

A total of 38% (9/24) of the apps’ privacy policies described collecting user data for the purposes of marketing the developer’s own products and services (Table 3). Privacy policies outlined users’ ability to “opt-out” (in the form of an unsubscribe notice) or stated that this type of marketing would only occur with the user’s consent (though this process was not always specified).

Revenue from Tailored Advertising

Developers reported 29% (7/24) of apps hosted advertisements and that this often allowed them to provide the app at no cost to users; only 25% (6/24) were labeled with “contains ads” in the Google Play store.22 In some cases, developers embedded an ad library into their application’s code and had no control over which ads appeared in their app (e.g., banner ads) or whether and how third parties tracked users and their data. Three of the sampled apps (Drugs.com Medication Guide, Epocrates Plus, Medscape) actively solicited advertisers such as pharmaceutical and other health-related companies and embedded these ads into their app and/or website content (e.g., native ads). In advertising prospectuses, developers emphasized the reach of their apps to the “global English-speaking community” (Drugs.com) and their accessibility to clinicians “in the moments of care” (Epocrates, Inc.).

Advertising could be “highly targeted” to the audience based on user characteristics. Epocrates, Inc.’s sponsored “DocAlert” messages, for example, contain branded clinical content and are targeted by “disease state, occupation, specialty, look-up history, formulary coverage, [and] geographies.” Epocrates, Inc. boasted a 3:1 return on advertising investment, alerting sponsors that they would be provided with physician-level data about the performance of their ad. User data were also used for “remarketing services” where app developers engaged third-party services (e.g., Google AdWords) to serve users targeted advertising on third-party websites after the user visited their app or associated website. Developers outlined a variety of ways that users could opt-out of tailored advertising; users would, however, continue to receive generic ads, but their information would not be used for the purpose of serving “interest-based ads.” Typically, this meant the user had to visit the individual websites of the advertising networks to opt-out or to modify settings on their device (e.g., turning off an app’s permission to access the user’s location).

Revenue from Sponsored Content

A total of 17% (4/24) of developers hosted sponsored content within their apps and websites (Drugs.com, Epocrates, Inc., MedAdvisor, WebMD). Developers distinguished between sponsored content (paid for by sponsors but controlled by the developer) and advertising (paid for and created by sponsors) in their editorial policies, but sometimes described advertising that blurred this boundary. For example, WebMD, the developer of Medscape, in their media kit, described the opportunity for “custom content development,” where advertisers could work with WebMD’s “DNA brand studio” to “tell [their] story through the creation of emotive content that is grounded in editorial insights and designed to influence action and drive emotional connections.” Developers identified sponsored content by appending labels such as “Funding from,” “Provided by,” or “From Our Sponsor.” Typically, this content linked to the sponsor’s website. In some cases, the source of the content on medicines information was ambiguous. Talking Medicines provided users “useful info about some key medicines,” which they described as “curated content taken from what people are saying on the web, popular conversations about medicines.”

The mobile platform also enabled sponsored content to take the form of targeted messaging based on user characteristics. In their Investor Prospectus, MedAdvisor promoted its app as allowing “pharmacists and pharmaceutical manufacturers to connect with their patients.” Pharmaceutical companies could sponsor targeted messaging on a subscription basis, aimed at boosting adherence rates (“adherence increases of up to 30%, translating to up to 30% more dispenses of those medications per annum, and reduced ‘drop-off’”) and “brand loyalty” as benefits of this subscription.

Commercializing Customer Insights

Two developers (Talking Medicines, GuildLink Pty Ltd) monetized their apps by selling reports of aggregated, de-identified users’ information or behaviors within the app. Talking Medicines, the developer of MedSmart Meds & Pill Reminder App, positioned itself as offering “unique patient insights from how medicines are used in the real world to healthcare stakeholders including pharmaceutical companies.” To users, the app was promoted as “designed to help you keep track of taking medicines” in the Google Play store description. However, the developer’s website is geared towards pharmaceutical companies as “customers”:

By understanding who is actually taking the medicines that are being developed and how they are being taken in the real world helps marketing teams to connect with their patients, listen to them and add value in their marketing communications and negotiations for listings.

They offered several types of commercial data reports to pharmaceutical companies, available as a subscription service, including “personal data” (what type of people are taking their medicines), where they sit within the competitive set, the combinations of over-the-counter and prescription medicines that people take, and “deeper dive analysis” to “uncover behavior and answer specific questions and challenges.” In contrast, some apps, such as Lexicomp, specifically stated that they “do not provide pharma companies with statistics reflecting end user usage habits.”

Licensing the App

Two apps (myPharmacyLink, MedAdvisor) specifically offered the ability for pharmacies to fully customize the app to the pharmacy’s branding to encourage “repeat business through easy script refill functions” (GuildLink Pty Ltd). MedAdvisor licenses its app to pharmacies, promoting itself as offering “compelling advantages to pharmacists, who benefit from increased revenue as patients are reminded to fill prescriptions or see their doctor for a new script.”

Exclusive “Supply” Agreements and Product Placement

In one case, MedAdvisor engaged in a form of sponsored product placement by entering into an exclusive 2-year “supply agreement” with GlaxoSmithKline, where GSK’s brand “Panadol Osteo” was granted exclusive access to be the only paracetamol-based product to engage with app users through sponsored targeted messaging.

DISCUSSION

In this sample of 24 medicines-related apps for the Android platform, developers commonly collected and employed app users’ data in a feedback loop to target users with promotional messages from developer and parent companies, third-party advertisers, and commercial sponsors, including the pharmaceutical industry. Developers employed user data for targeted marketing and tailoring of sponsored content, which calls into question the claims developers made about the trustworthiness, independence, and risk of bias of medicines information that is purportedly evidenced-based. Ultimately, these often insidious promotional practices create the risk for mistreatment, overtreatment, or overdiagnosis through promotion of new, costly, and branded products or services, particularly medicines, that are unnecessary or represent little benefit over existing treatments.5

Apps targeted primarily at clinicians attracted advertising from pharmaceutical and other medically related companies, much like a medical journal. Although doctors frequently rely on pharmaceutical advertising to learn about new products, analyses of advertising in medical journals suggest that key information, particularly in relation to safety, is often missing and that misleading claims are prevalent.23, 24 Digital advertising, however, allows for an unprecedented level of targeting to the individual clinician across platforms and in the context of apps, accompanies a user in the moment of care, making it highly tailored and ubiquitous in contrast to traditional print advertisements. In our analysis, developers boasted of the return on investment that this form of “interest-based” advertising offered, suggesting that it is also effective in promoting prescriptions. Medical journal advertising declined from $744 million in 1997 to $119 million in 201614; mobile apps may offer a new and largely unregulated avenue for targeting clinicians. Thus, guidance pertaining to drug promotion requires updating to account for these new advertising tactics and also a broader range of ethical values, such as privacy.5

Apps designed to promote medication management and adherence encouraged and enabled users to share their medicines-related data; however, developers also used this information for commercial purposes—albeit typically in aggregated and de-identified forms—and informed consumers only in the “fine print.” A longitudinal survey of 4000 USA consumers found that only 11% of respondents were willing to share their health data with tech companies like Google or Facebook, and 20% with pharmaceutical companies.25 Unfortunately, health-related data, or data that can be used to make inferences about one’s health, are shared routinely and often without users’ informed or express consent.14, 17, 26

Developers in our sample commercialized app user data in the form of selling or licensing reports of user behavior within the app. This is another example of what has been termed the “digital patient experience economy,” where patients’ online accounts are collected through digital platforms specifically for the purpose of commercializing this data in form of targeted advertising or on-selling the data to third parties.27 Other content analyses of health-related apps have similarly found that the commercial interests underpinning the content or platform lack transparency.28

Limitations

This is a cross-sectional content analysis and developers may have updated their privacy policies or business practices. Our sample is restricted to apps for the Android platform; it is not known how the privacy practices of medicines-related apps on the iOS platform compare. Our purposive, criterion sampling strategy was designed to sample prominent medicines-related apps that were likely to share data; thus, while information-rich, the strategy emphasized similarities rather than variability. Our findings are therefore not generalizable to medicines-related or health apps in general, and other purposive sampling strategies may have detected a greater diversity of promotional strategies. Many privacy policies were not specific to the app; thus, it is not known to what degree inferences about data collection or commercialization practices apply to use of the app, linked websites, or both.

Implications for Practice and Policy

Our findings suggest that medicines-related apps may be a novel means to promote medicines that has largely escaped academic and policy scrutiny. Parker and colleagues5 proposed that the WHO update and expand the ethical criteria for drug promotion, suggesting that criteria be grounded in principles of public health ethics including, but not limited to, maximizing benefit, minimizing harm, promoting autonomy, and communicating honestly. We suggest implications for practicing clinicians and policymakers, drawing on relevant principles of public health ethics in regard to use of medicines-related apps:

Maximizing benefit: Clinicians should seek out developers who are independent of medically related industry, which includes apps that are free of advertising and industry sponsorship.5 Ideally, content should be independent, peer-reviewed, authors and contributors credited, and free from conflicts of interest.

Minimizing harm: Clinicians should select apps with content available offline that request minimal permissions related to user data, permit users to control what data is shared when, and with whom (e.g., turning off location tracking), or, at minimum, offer full transparency about privacy practices.14 Clinicians should educate themselves on drivers of and conditions that are prone to mistreatment, overdiagnosis, and overtreatment,29, 30 and be prepared to discuss and potentially counter promotional adherence messages targeted at patients.31

Promoting autonomy: Regulators should prohibit direct-to-consumer advertising and product placement (i.e., “exclusive” supply agreements) within apps to allow individuals to make and act on their personal choices in relation to their health.5

Communicating honestly: Regulators should require, at minimum, full transparency about the nature of user data collection and use. Clinicians should also consider raising issues related to sponsorship, advertising, and privacy practices when discussing app use with patients as part of the process of informed consent.

Unfortunately, this analysis also highlights that identifying and selecting apps that meet these ethical criteria require some due diligence, and we recommend that clinicians research apps prior to use, including reading privacy and editorial policies.

CONCLUSIONS

Though there is growing concern about third-party access to app users’ data, app developers also routinely employ users’ data for commercial purposes. Promotional strategies can be highly targeted on the basis of user characteristics and may create a heightened risk for mistreatment, overtreatment, or overdiagnosis associated with drug promotion in general. Many promotional strategies lack transparency or rely on implied rather than informed consent through download and use of the app. Sponsored content, targeted messaging, or product placement in the context of apps providing medicines information calls into question whether these apps are truly evidence-based and independent. Clinicians and consumers should seek out medicines-related apps from developers that do not commercialize user data.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(PDF 490 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Chris Klochek, MSc, for developing the app store crawling program.

Funding

This work was funded by a grant from the Sydney Policy Lab at The University of Sydney. Quinn Grundy was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Mobasheri MH, King D, Johnston M, Gautama S, Purkayastha S, Darzi A. The ownership and clinical use of smartphones by doctors and nurses in the UK: a multicentre survey study. BMJ Innov. 2015;1(4):174–181. doi: 10.1136/bmjinnov-2015-000062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed I, Ahmad NS, Ali S, et al. Medication adherence apps: Review and content analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2018;6(3):e62. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.6432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson D. Drug ap comes free, ads included. The New York Times. July 29, 2011: B1.

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO) Ethical criteria for medicinal drug promotion. Geneva: WHO; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parker L, Williams J, Bero L. Ethical drug marketing criteria for the 21st century. BMJ. 2018;361:k1809. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ebeling M. ‘Get with the Program!’: Pharmaceutical marketing, symptom checklists and self-diagnosis. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(6):825–832. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dehling T, Gao F, Schneider S, Sunyaev A. Exploring the far side of mobile health: Information security and privacy of mobile health apps on iOS and Android. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(1):e8. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vallina-Rodriguez N, Sundaresan S, Razaghpanah A, et al. Tracking the trackers: Towards understanding the mobile advertising and tracking ecosystem. 1st Data and Algorithm Transparency Workshop; 2016; New York, NY.

- 9.Razaghpanah A, Nithyanand R, Vallina-Rodriguez N, et al. Apps, Trackers, privacy, and regulators: A global study of the mobile tracking ecosystem. Proceedings 2018 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; 2018.

- 10.Binns R, Lyngs U, Van Kleek M, Zhao J, Libert T, Shadbolt N. Third party tracking in the mobile ecosystem. Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Web Science - WebSci '18; 2018.

- 11.Grundy Q, Held F, Bero L. Tracing the potential flow of consumer data: A network analysis of prominent health and fitness apps. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(6):e233. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huckvale K, Prieto J, Tilney M, Benghozi P-J, Car J. Unaddressed privacy risks in accredited health and wellness apps: a cross-sectional systematic assessment. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):214. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0444-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papageorgiou A, Strigkos M, Politou E, Alepis E, Solanas A, Patsakis C. Security and privacy analysis of mobile health applications: The alarming state of practice. IEEE Access. 2018;6:9390–9403. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2799522. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grundy Q, Chiu K, Held F, Continella A, Bero L, Holz R. Data sharing practices of medicines related apps and the mobile ecosystem: traffic, content, and network analysis. BMJ. 2019;364:l920. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grindrod K, Boersema J, Waked K, Smith V, Yang J, Gebotys C. Locking it down: The privacy and security of mobile medication apps. Can Pharm J. 2017;150(1):60–66. doi: 10.1177/1715163516680226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blenner SR, Köllmer M, Rouse AJ, Daneshvar N, Williams C, Andrews LB. Privacy policies of android diabetes apps and sharing of health information. JAMA. 2016;315(10):1051–1052. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.19426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robillard Julie M., Feng Tanya L., Sporn Arlo B., Lai Jen-Ai, Lo Cody, Ta Monica, Nadler Roland. Availability, readability, and content of privacy policies and terms of agreements of mental health apps. Internet Interventions. 2019;17:100243. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2019.100243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Quality Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santo K, Richtering SS, Chalmers J, Thiagalingam A, Chow CK, Redfern J. Mobile phone apps to improve medication adherence: A systematic stepwise process to identify high-quality apps. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2016;4(4):e132–e132. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.6742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Android Developers. System permissions. 2018; https://developer.android.com/guide/topics/security/permissions.html#normal-dangerous. Accessed July 27, 2018.

- 21.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) - A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Google I. Play console help: Set up prices & app distribution. 2019; https://support.google.com/googleplay/android-developer/answer/6334373?hl=en&ref_topic=7071529. Accessed May 1, 2019.

- 23.Othman N, Vitry A, Roughead EE. Quality of pharmaceutical advertisements in medical journals: A systematic review. PLOS ONE. 2009;4(7):e6350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korenstein D, Keyhani S, Mendelson A, Ross JS. Adherence of pharmaceutical advertisements in medical journals to FDA guidelines and content for safe prescribing. PLOS ONE. 2011;6(8):e23336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Day S, Zweig M. Beyond wellness for the healthy: Digital health consumer adoption 2018. San Francisco: Rock Health; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sunyaev A, Dehling T, Taylor PL, Mandl KD. Availability and quality of mobile health app privacy policies. JAMIA. 2015;22(e1):e28–e33. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lupton D. The commodification of patient opinion: the digital patient experience economy in the age of big data. Sociol Health Illn. 2014;36(6):856–869. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lupton D, Jutel A. ‘It’s like having a physician in your pocket!’ A critical analysis of self-diagnosis smartphone apps. Soc Sci Med. 2015;133:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parker L, Grundy Q, Bero L. Interpreting evidence in general practice: Bias and conflicts of interest. Aust J General Practitioners. 2018;47(6):337–340. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-12-17-4432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pathirana T, Clark J, Moynihan R. Mapping the drivers of overdiagnosis to potential solutions. BMJ. 2017;358:j3879. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parker L, Bero L, Gillies D, et al. Mental health messages in prominent mental health apps. Ann Family Med. 2018;16(4):338–342. doi: 10.1370/afm.2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 490 kb)