Abstract

Value-based payment initiatives, such as the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), offer the possibility of using financial incentives to drive improvements in mental health and substance use outcomes. In the past 2 years, Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) participating in the MSSP began to publicly report on one behavioral health outcome—Depression Remission at Twelve Months, which may indicate how value-based payment incentives have impacted mental health and substance use, and if reforms are needed. For ACOs that meaningfully reported performance on the depression remission measure in 2017, the median rate of depression remission at 12 months was 8.33%. A recent meta-analysis found that the average rate of spontaneous depression remission at 12 months absent treatment was approximately 53%. Although a number of factors likely explain these results, the current ACO design does not appear to incentivize improved behavioral health outcomes. Four changes in value-based payment incentive design may help to drive better outcomes: (1) making data collection easier, (2) increasing the salience of incentives, (3) building capacity to implement new interventions, and (4) creating safeguards for inappropriate treatment or reporting.

KEY WORDS: value-based payment, payment reform, depression, mental health, behavioral health

As of August of 2018, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have released 2 years of data on the Accountable Care Organizations’ (ACOs) performance on the “Depression Remission at Twelve Months” quality measure. Depression remission performance indicates how value-based payment is progressing in behavioral health, as early research found that few ACOs were meaningfully addressing behavioral health in their populations.1

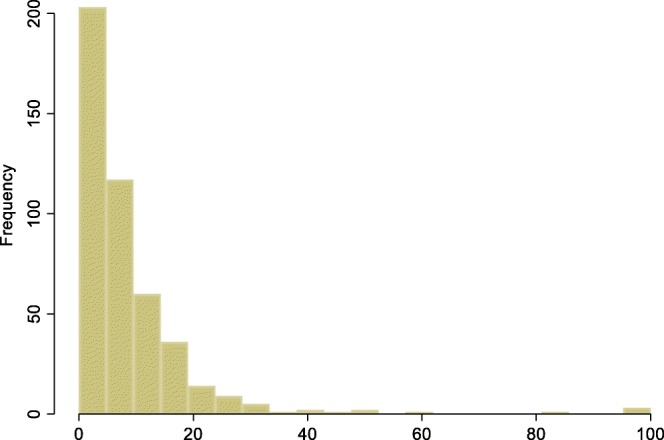

The Depression Remission quality measure evaluates the proportion of patients identified with depression at the beginning of the year who score below a cutoff on a depression screen by the end of the year.2 While far from perfect, this measure stands out as one of the few patient-reported outcome performance measures (PRO-PMs) used by CMS, and one of the only outcome measures in behavioral health. At present, Depression Remission is a pay-for-reporting measure, so ACOs are not reimbursed based on their performance on the measure, only whether they report it. It supplements “Screening for Clinical Depression and Follow-up Plan,” which evaluates rates of screening for depression, and is a pay-for-performance for ACOs beginning their second year in the program. The summary statistics for ACO performance on the Screening quality measure and the Depression Remission quality measure in 2016 and 2017 are presented in Table 1, and a histogram of Depression Remission scores for 2017 are presented in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Summary Statistics for ACO Performance on the Depression Screening Quality Measure and the Depression Remission Quality Measure in 2016 and 2017

| Year | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2017 | |

| Total ACOs | 432 | 472 |

| Screening for Clinical Depression and Follow-up Plan | ||

| Number excluded (N/A or 0) | 4 | 6 |

| Sample size | 428 | 466 |

| Mean (% screened) | 53.62 | 62.10 |

| Standard deviation | 21.21 | 19.77 |

| Median (% screened) | 53.43 | 65.24 |

| Maximum | 97.18 | 99.18 |

| Minimum | 0.16 | 0.81 |

| Depression Remission at Twelve Months | ||

| Number excluded (N/A or 0) | 230 | 149 |

| Sample size | 204 | 323 |

| Mean (% remission) | 12.27 | 11.50 |

| Standard deviation | 11.20 | 12.62 |

| Median (% remission) | 9.09 | 8.33 |

| Maximum | 67.86 | 100 |

| Minimum | 1.32 | 0.76 |

Figure 1.

Histogram of ACO Depression Remission at Twelve Months scores, 2017.

In preparing the summary statistics, we excluded all ACOs that either did not report Depression Remission or reported a score of zero, assuming that this was equivalent to failing to meaningfully collect the data. This led to an exclusion of over half of the participating ACOs for 2016 and slightly under one-third of participating ACOs in 2017. Among the remaining ACOs, the median Depression Remission was 9.09% in 2016 and 8.33% in 2017, while the median Screening was 53.4% in 2016 and 65.2% in 2017.

A recent meta-analysis estimated that the rate of depression remission among adults that received no treatment after 12 months was 53%,3 making the rate of depression remission reported by ACOs participating in the MSSP—8.33%—less than that of no treatment by a substantial margin. With 2 years of public data available now for the ACO program, measuring Depression Remission on its own does not appear (from the available data) to have motivated better performance in depression care.

Four changes in value-based program design may help to promote strong performance on PRO-PMs in mental health: (1) making data collection easier, (2) increasing the salience of incentives, (3) building capacity to implement new interventions, and (4) creating safeguards for inappropriate treatment or reporting.

Making Data Collection Easier

Most of the poor ACO performance on Depression Remission is likely due to loss to follow-up—the provider did not make another contact around 12 months and was unable to determine whether the individual’s symptoms improved. Because Depression Remission is a PRO-PM, and future mental health outcomes likely will be as well, data collection could be streamlined by having individuals complete the follow-up instrument at home or through an app or text message platform. CMS can ensure that payment policy supports ACOs to build out this digital capability, and reimburse for the effort required to follow-up with individuals to complete the instrument at home—enabling better reporting and more effective measurement-based care.4

Increasing the Salience of Incentives

Reporting aggregated performance data to CMS may not motivate provider level change—providers need incentives that fit into their clinical workflow and align with what we know from behavioral economics and improvement science.5 CMS can increase the financial incentives by transitioning Depression Remission to a pay-for-performance measure, but it can also work with ACOs and quality improvement organizations to ensure that information is timely, salient, and interpretable at the provider level.

Building Capacity to Implement New Interventions

Many ACOs likely do not have the resources in place to offer integrated behavioral health services and supports and are not incentivized to build out new capacities by the ACO model design. Because evidence suggests that depression remission predicts lower long-term costs, CMS has the opportunity to build capacity among ACOs while maintaining cost neutrality.6 CMS can offer additional upfront investments that produce commensurate savings, as with the ACO Investment Model, or increase value-based payments based on the associated savings, as with the Outcomes-Based Credits in the Maryland Total Cost of Care Model. In addition, CMS may need to lead additional shared learning activities for ACOs to support integration of behavioral health delivery innovations, such as tele-mental health, certified peer support specialists, and digital mental health.

Creating Safeguards for Inappropriate Treatment or Reporting

If Depression Remission were a pay-for-performance measure, the ACOs reporting 100% remission may give us pause. If an ACO outperforms the literature, this may point to an exciting innovation, but it may also indicate a reporting error, cherry-picking issues, or even overtreatment. CMS will need to create procedures to evaluate performance variation, touting delivery innovations or working with ACOs to correct reporting issues. CMS may also need to implement supplemental process measures to identify potential overtreatment, especially in children and adolescents.

On the other hand, pay-for-performance for Depression Remission may create disincentives for treating individuals with severe or treatment-resistant depression, or other forms of complexity. Because the measure is constructed based on binary change from case to non-case, it rewards a transition from severe to minimal depression the same as moderate to minimal and penalizes a transition from severe to moderate depression, even of that improvement would have a profound impact on the individual. When tied to payment, this measure could fail to finance effective practice for individuals with the greatest need. As a pay-for-performance measure, it should look at dimensional change, i.e., whether an individual improved by a certain amount even if they are not “well” by the end of the year, or use another method of risk adjustment.

CONCLUSION

Value-based payment holds promise for integrating effective behavioral health care and improving population health, but early results are mixed. Additional reforms will be necessary to ensure that ACOs and other value-based payment models equip providers with necessary resources and offer salient incentives to motivate needed transformation.

Authors’ Contributions

Mr. Counts led the initial drafting, and all authors offered critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors had access to the data, which is publicly available.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Busch AB, Huskamp HA, McWilliams JM. Early efforts by Medicare accountable care organizations have limited effect on mental illness care and management. Health Affairs. 2016;35(7):1247–56. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pincus HA, Scholle SH, Spaeth-Rublee B, Hepner KA, Brown J. Quality measures for mental health and substance use: gaps, opportunities, and challenges. Health Affairs. 2016;35(6):1000–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whiteford HA, Harris MG, McKeon G, Baxter A, Pennell C, Barendregt JJ, Wang J. Estimating remission from untreated major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological medicine. 2013;43(8):1569–85. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fortney JC, Unützer J, Wrenn G, Pyne JM, Smith GR, Schoenbaum M, Harbin HT. A tipping point for measurement-based care. Psychiatric Services. 2016;68(2):179–88. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcotte L, Hodlofski A, Bond A, Patel P, Sacks L, Navathe AS. Into practice: How Advocate Health System uses behavioral economics to motivate physicians in its incentive program. Healthcare. 2017;5(3):129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dennehy EB, Robinson RL, Stephenson JJ, Faries D, Grabner M, Palli SR, Stauffer VL, Marangell LB. Impact of non-remission of depression on costs and resource utilization: from the COmorbidities and symptoms of DEpression (CODE) study. Current medical research and opinion. 2015;31(6):1165–77. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1029893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]