Abstract

Aim

This study aimed to evaluate the effect of a team training program to support shared mental model (SMM) development in interprofessional rounds.

Design and Participants

A three-arm randomized controlled trial study was conducted for interprofessional teams of 207 health profession learners who were randomized into three groups.

Program Description

The full team training program included a didactic training part on cognitive tools and a virtual simulation to support clinical teamwork in interprofessional round. Group 1 was assigned to the full program, group 2 to the didactic part, and group 3 (control group) with no intervention. The main outcome measure was team performance in full scale simulation. Secondary outcome was interprofessional attitudes.

Program Evaluation

Teamwork performance and interprofessional attitude scores of the full intervention group were significantly higher (P < 0.05) than those of the control group. The two intervention groups had significantly higher (P < 0.05) attitude scores on interprofessional teamwork compared with the control group.

Discussion

Our study indicates the need of both cognitive tools and experiential learning modalities to foster SMM development for the delivery of optimal clinical teamwork performances. Given its scalability and practicality, we anticipate a greater role for virtual simulations to support interprofessional team training.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-019-05320-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: interprofessional education, team training, virtual simulation, shared mental model, structured communication tools and team performance

INTRODUCTION

There is an increasing focus on the development of team training program that foster effective teamwork behaviors, including communication, coordination, and collaboration, to enhance team-based care in healthcare settings.1 The concept of the shared mental model (SMM) has been acknowledged as an important aspect of successful teamwork and collaboration in healthcare.2 Floren (2018) defined the SMM as “an individually held, organized, cognitive representation of task-related knowledge and/or team-related knowledge that is held in common among healthcare providers who must interact as a team in the pursuit of common objectives for patient care.”3

Team training using simulation has been identified as a potentially powerful tool to facilitate the development of SMMs within interprofessional teams. The use of simulation to facilitate the practice of cognitive tools such as checklists and reminders has been shown to support the development of SMMs.4 However, logistical issues in organizing simulation training have proven challenging, particularly among pre-registration healthcare students who are often trained in different institutions. With advances in learning technology, virtual environments can provide a viable and innovative platform for team-based simulation training.5

As part of an interprofessional education initiative for diverse health professions learners, a group of academic staff and educational technologies from four higher educational institutions developed a team training program. The program included didactic training on cognitive tools and virtual simulations to support SMM development on clinical teamwork in interprofessional rounds. A technopreneur company supported the development of virtual simulation using the Unity 5 games engine (Unity Technologies, San Francisco, CA), which was piloted and improved based on the learners’ evaluation.6

This study aimed to evaluate the effect of a team training program to support shared mental model (SMM) development in interprofessional rounds. The relationship between team performance and SMMs has been empirically supported in previous studies; teams holding more similar SMMs have been shown to have positively related better team performance.7, 8 Thus, in this study, we evaluated team performance in full scale simulation as the main outcome measure. In contrast to didactic training, virtual simulation training requires more resources and is complex to deliver and sustain. As such, there is a need to justify whether this educational intervention that facilitates SMM development through experiential learning can lead to better learning outcomes. Therefore, in this study, we also evaluated the effectiveness of virtual simulation as a supplement to didactic training.

STUDY DESIGNS, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS

A three-arm randomized controlled trial consisting of two intervention groups and a control group was employed in this study. This design allowed an evaluation of the effectiveness of team training program by comparing with the control group and enabled the comparison of two intervention groups to evaluate the effectiveness of virtual simulation training. After receiving approval from institutional review boards, 207 healthcare students undertaking healthcare courses in three tertiary educational institutions were recruited and assigned into interprofessional teams of five to six healthcare students from different healthcare courses (medicine, nursing, pharmacy, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and medical social work). The 40 interprofessional teams were randomized into the following groups: (1) full intervention team training program, (2) didactic-only training on cognitive tools, and (3) a control group with no intervention. After completion of the study evaluation, the didactic-only group received virtual simulation training whereas the control group received the full intervention.

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

Didactic Training on Cognitive Tools

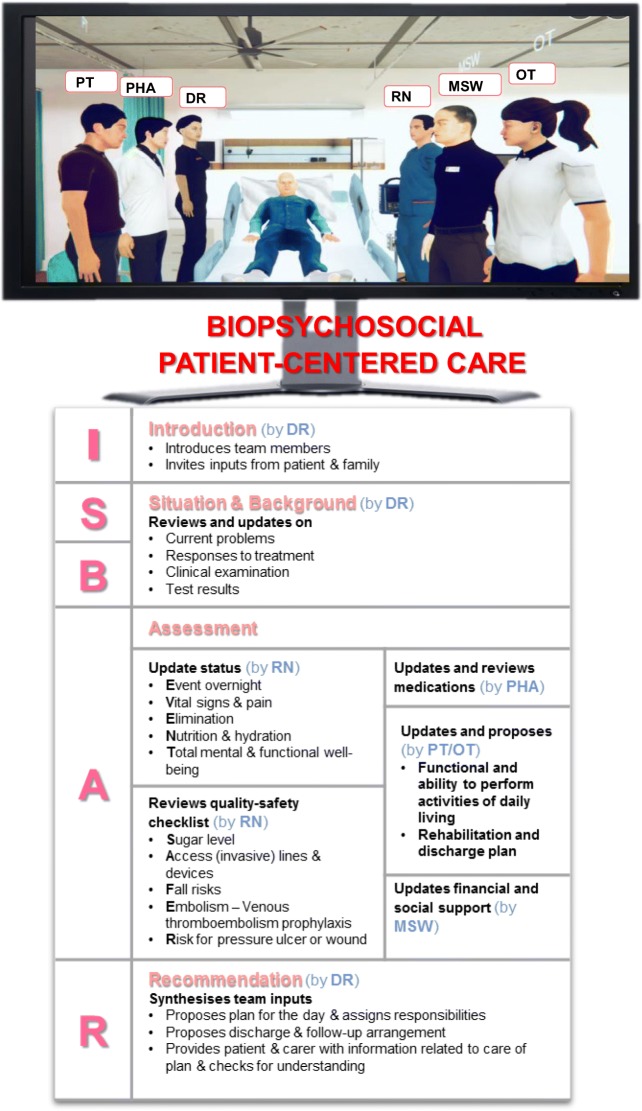

Didactic training part of the team training program focused on the acquisition of cognitive tools that can be applied during interprofessional rounds. Using a computer setup at a university simulation center, participants were directed to an asynchronous online video for about half an hour. As shown in Figure 1, the team cognitive tools included (1) Identity, Situation, Background, Assessment and Recommendation (ISBAR) communication tool, adopted and modified from the “In Safe hands” program,9 which spelled out the roles of each team member as well as the sequence and nature of inputs to be used for communicating with patients, their families, and other team members and (2) biopsychosocial model of health, which covers the medical, functional, psychological, and social dimensions of illness,10 to facilitate interprofessional team planning of an actionable comprehensive care plan.

Figure 1.

Cognitive tools and virtual simulation.

Virtual Simulation

In addition to receiving didactic training on cognitive tools, participants from the full intervention group underwent virtual simulation training. Each participant logged onto the virtual platform and assumed the avatar representing the respective profession to participate in real-time interprofessional rounds with other team members. In the first scenario involving bedside round, the interprofessional team was expected to apply the cognitive tools to render team care for an elderly post-operative patient (Mr. Jin) who presented with pain and fever on the 3rd post-operative day. The second scenario involved a family conference to discuss the discharge plan for Mr. Jin with his family. Each scenario ended with a debrief session. Facilitated by a healthcare clinician or faculty staff, the participants reflected on their virtual simulation experiences and the application of the cognitive tools during the debriefing sessions. The entire virtual team training took about 2 h.

PROGRAM EVALUATION

Data Collection and Instrument

All participants from both intervention groups undertook team-based simulation assessments on interprofessional bedside rounds immediately after the study interventions whereas the control group underwent the simulation assessment before receiving the study interventions. The simulation assessment lasted about 15 min and required the teams to perform interprofessional bedside rounds of a simulated patient with physical and psychosocial issues. Recordings of the simulation process were sent to two raters who were blinded to the grouping and independently scored the team performances using a validated rating scale developed by the research team (see supplementary material).

The development of the rating scale was informed by literature related to relevant teamwork instruments.11, 12 A total of 14 checklist items using 3-point scale (0 = behavior was not observed; 1 = behavior was doubtful or inconsistent; 2 = behavior was clearly observed) were constructed using observable teamwork and collaborative behaviors during interprofessional rounds. A global rating item (on a scale of 1 to 10) was also included to allow an overall rating of team performance. The content validity of the tool was established by an interprofessional team of five academics and clinicians with background in nursing, physiotherapy, geriatric medicine, and medical education. Inter-rater reliability was tested across two raters, who independently scored ten video-recorded team performances, and yielded a high intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.95 (95% confidence interval ranges between 0.93 and 0.96). Internal consistency, which was computed based on the rating of 40 video-recorded team performances, was good with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.

Prior to the simulation assessments, participants completed questionnaires to evaluate their attitudes towards interprofessional team care. These include the 14-item Attitudes Towards Interprofessional Health Care Teams (ATIHCT) and the 24-item Interprofessional Socialization and Valuing Scale (ISVS). Consistent with the robust psychometrics properties of ATIHCT and ISVS reported in earlier studies,13, 14 our study showed high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha 0.82 and 0.95 respectively),

DATA ANALYSIS

Descriptive statistics and a univariate analysis were used to analyze the characteristics of the study population. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to determine differences between the three arms in teamwork performance and attitudes scores.

RESULTS

Two hundred seven (n = 207) healthcare students participated in the interprofessional team training. Most were female (65.2%) and undertaking a degree course (71%). There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics among the three groups, including age (P = 0.63), gender (P = 0.81), type of qualification (P = 0.77), and type of healthcare course (P = 0.19), supporting post-randomization homogeneity among the groups.

The Kruskal-Wallis test revealed a significant difference for team performance (H(2,37) = 11.1, P < 0.05, η2 = 0.29) between the three groups. As shown in Figure 2, pairwise comparison indicated that team performance of the full intervention group was significantly higher than the control group (M = 28.93 (SD 4.58) vs M = 24.15 (SD 3.63), P < 0.05). There were no significant differences between the didactic-only and control groups (M = 27.38 (SD 3.69) vs M = 24.15 (SD 3.63), P = 0.08) or between the full intervention and didactic groups (M = 28.93 (SD 4.58) vs M = 27.38 (SD 3.69), P = 0.96).

Figure 2.

Comparisons of team performance mean scores between groups.

With regard to interprofessional attitudes, one-way ANOVA revealed a significant difference in the ISVS (F(2,205) = 34.64, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.25) and ATIHCT (F(2,166) = 6.04, P < 0.01, η2 = 0.07) scores between the three groups. Post hoc comparison indicated that both the full intervention and didactic training groups had significantly higher ISVS (P < 0.001) and ATIHCT (P < 0.05) mean scores than the control group. There was no significant difference between the full intervention and didactic-only groups for the ISVS (M = 139.8 (SD 14.2) vs M = 137.0 (SD 12.6), P = 0.77) and ATIHCT (M = 58.55 (SD 6.07) vs M = 58.63 (SD 5.74), P = 1.00).

DISCUSSION

Our paper contributes to the burgeoning literature of interprofessional team-based care delivery by describing and evaluating an innovative team training intervention to support SMM development in interprofessional rounds. Our findings show that there was a significant effect on team performance when comparing between full intervention and control groups, in contrast to the lack of effectiveness of didactic-only training on team performance compared with the control group. These findings raise questions regarding the effectiveness of the acquisition of SMMs through a single educational intervention using only didactic method and suggest the critical role of experiential learning modalities such as simulation in the development and application of SMMs to improve team performance. Our findings support an earlier review that recommended the use of team training interventions that pair learning activities and practices with tools to optimize clinical teamwork.1 Congruent with other simulation-based team training programs,15, 16 our findings support the use of simulation to provide opportunities for the interprofessional team to work together and practice the use of cognitive tools to build a shared understanding of team roles and tasks.

This study uniquely addressed logistical challenges on the use of simulation for collaborative learning in interprofessional team care delivery. To our knowledge, this is the first study in interprofessional education within the healthcare setting that focused on the development of SMMs using virtual simulations. In this study, our virtual simulation training afforded the experiential learning approach commonly applied in physical simulation. It provided opportunities for different team members to simultaneously apply and practice the use of cognitive tools in interprofessional round scenarios, thus strengthening the formation of SMMs. In addition, the cognitive tools were incorporated into the debriefing process to guide facilitators in providing feedback to the learners, a critical step in maximizing the development of SMMs.17 Given its practicality, flexibility, and potential for scalability, virtual simulation training confers practical advantages over existing modalities of simulation for training large groups of learners across different institutions.5

Even though full intervention showed superiority to control group on team performance while the didactic-only intervention did not, full intervention was not shown to be superior to the didactic-only intervention on team performance and attitudes towards interprofessional collaboration. Possible reasons include an underpowered study to detect statistical significance for post hoc comparison between full versus didactic-only intervention, and the lack of discriminatory ability of the team performance rating scale to detect differences of a smaller magnitude. Nevertheless, the lack of substantial differences between these two interventions may suggest the potential role of didactic training in supporting development of SMMs in interprofessional education. Thus, our findings lend indirect support to the suggestion by Hobgood et al. that institutions with limited resources for implementing simulations should not be deterred from delivering teamwork training using other more conventional educational modalities.18

In contrast to the findings on team performance, our findings provide evidence on the effectiveness of didactic-only training on the attitudes of interprofessional collaboration. A possible explanation for these contrasting outcomes could be the use of self-reported attitudes questionnaires that may be subjected to social desirability. Although a rigorous outcome measure using simulation-based team performance assessments was employed for this study, it was limited to immediate post-intervention evaluations. Thus, future studies should adopt a longitudinal design to evaluate the retention and transfer of learning or even the impact of the intervention on healthcare delivery and patient care. Finally, by evaluating the team effectiveness, our study is limited by the indirect measurement of SMMs. The challenges of measuring SMMs are well documented.3

CONCLUSION

With the application of SMM constructs, we developed and evaluated a team training program using didactic training on cognitive tools and virtual simulations to support clinical teamwork in interprofessional rounds. Our findings not only highlighted the use of these bundled educational interventions but also the critical role of experiential modality to foster the development of SMMs for effective performance outcomes. Team training among diverse healthcare students from different institutions was made possible with virtual simulations. Moving forward, we anticipate a greater role of virtual simulation in interprofessional team training to prepare a future collaborative-ready workforce.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 21 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the healthcare students for their participation as well as the rest of CREATIVE team including John Yap, Tan Khoon Kiat, Shem Teo, Choo Hyekyung, Wong Li Lian, and May, Lim Sok Mui for their help in recruiting the students. We also thank the staff of the Centre for Healthcare Simulation for supporting with this study. Lastly, we would like to thank the National University Health System Publications Support Unit for providing editing services for this manuscript.

Funding Information

This study was financially supported by Singapore Millennium Foundation Research Grant.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

After receiving approval from institutional review boards, 207 healthcare students undertaking healthcare courses in three tertiary educational institutions were recruited and assigned into interprofessional teams of five to six healthcare students from different healthcare courses (medicine, nursing, pharmacy, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and medical social work).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

2/18/2020

This capsule commentary, Capsule Commentary on Liaw et al., “Getting everyone on the same page”: interprofessional team training to develop shared mental models on interprofessional rounds,” was to have accompanied the article, DOI: <ExternalRef><RefSource>https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05320-z</RefSource><RefTarget Address="10.1007/s11606-019-05320-z" TargetType="DOI"/></ExternalRef>, which appeared in the December 2019 issue

Change history

2/18/2020

This capsule commentary, Capsule Commentary on Liaw et al., ���Getting everyone on the same page���: interprofessional team training to develop shared mental models on interprofessional rounds,��� was to have accompanied the article, DOI: 10.1007/s11606-019-05320-z, which appeared in the December 2019 issue

References

- 1.Weaver SJ, Dy SM, Rosen MA. Team-training in healthcare: a narrative synthesis of the literature. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(5):359–372. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McComb S, Simpson V. The concept of shared mental models in healthcare collaboration. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(7):1479–88. doi: 10.1111/jan.12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Floren LC, Donesky D, Whitaker E, Irby DM, Ten Cate O, O’Brien BC. Are we on the same page? Shared mental models to support clinical teamwork among health professions learners: a scoping review. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):498–509. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeChurch LA, Mesmer-Magnus JR. The cognitive underpinnings of effective teamwork: A meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2010;95(1):32–53. doi: 10.1037/a0017328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liaw SY, Carpio GAC, Lau Y, Tan SC, Lim WS, Goh PS. Multiuser virtual worlds in healthcare education: a systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;65:136–149. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liaw SY, Soh S, Tan KK, Wu LT, Yap J, Chow YL, Lau TC, Lim WS, Tan SC, Choo H, Wong LL, Lim MSM, Ignacio J, Wong LF. Design and evaluation of a 3D virtual environment for collaborative learning in interprofessional team care delivery. Nurse Educ Today. In press [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Mathieu JE, Heffner TS, Goodwin GF, Salas E, Cannon-Bowers JA. The influence of shared mental models on team process and performance. J Appl Psychol. 2000;85(2):273–83. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.85.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rico R, Sánchez-Manzanares M, Gil F, Gibson C. Team Implicit Coordination Processes: A Team Knowledge-Based Approach. Acad Manag Rev. 2008;33(1):163–184. doi: 10.5465/amr.2008.27751276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clinical Excellence Commission. In safe hands. 2016. Available at: http://www.cec.health.nsw.gov.au/quality-improvement/team-effectiveness/insafehands. Accessed 14 June, 2019.

- 10.Van Dijk-de VA, Moser A, Mertens V-C, Van der Linden J, Van der Weijen T, Van Eijk TM. The ideal of biopsychosocial chronic care: How to make it real? A qualitative study among Dutch stakeholders. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henneman EA, Kleppel R, Hinchey KT. Development of a checklist for documenting team and collaborative behaviours during multidisciplinary bedside rounds. J Nurse Adm. 2013;43(5):280–285. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31828eebfb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutton G, Liao J, Jimmieson NL, Restubog SL. Measuring multidisciplinary team effectiveness in a ward-based healthcare setting: development of the team functional assessment tool. J Health Qual. 2011;33(3):10–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2011.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curran VR, Sharpe D, Forristall J. Attitudes of health sciences faculty members towards interprofessional teamwork and education. Med Educ. 2007;41(9):892–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King G, Shaw L, Orchard CA, Miller S. The interprofessional socialization and valuing scale: a tool for evaluation the shift towards collaborative care approaches in health care settings. Work. 2010;35(1):77–85. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2010-0959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brock D, Abu-Rish E, Chiu C, et al. Interprofessional education in team communication: working together to improve patient safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(5):414–423. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riley W, Davis S, Miller K, Hansen H, Sainfort F, Sweet R. Didacting and simulation nontechnical skills team training to improve perinatal patient outcomes in a community hospital. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37(8):357–364. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandez R, Shah S, Rosenman ED, Kozlowshi SWJ, Parker SH, Grand JA. Developing team cognition: a role for simulation. Simul Healthc. 2017;12(2):96–103. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hobgood C, Sherwood G, Frush K, et al. Teamwork training with nursing and medical student: does the method matter? Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(6):e25. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2008.031732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 21 kb)