Abstract

Background:

At present, the role of autologous cells as antigen-carriers inducing immune tolerance is appreciated. Accordingly, intravenous administration of haptenated syngeneic mouse red blood cells (sMRBC) leads to hapten-specific suppression of contact hypersensitivity (CHS) in mice, mediated by light chain-coated extracellular vesicles (EVs). Subsequent studies suggested that mice intravenously administered with sMRBC alone may also generate regulatory EVs, revealing the possible self-tolerogenic potential of autologous erythrocytes.

Objectives:

The current study investigated the immune effects induced by mere intravenous administration of a high dose of sMRBC in mice.

Methods:

The self-tolerogenic potential of EVs was determined in a newly developed mouse model of delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) to sMRBC. The effects of EV’s action on DTH effector cells were evaluated cytometrically. The suppressive activity of EVs, after coating with anti-hapten antibody light chains, was assessed in hapten-induced CHS in wild type or miRNA-150−/− mice.

Results:

Intravenous administration of sMRBC led to the generation of CD9+CD81+ EVs that suppressed sMRBC-induced DTH in a miRNA-150-dependent manner. Furthermore, the treatment of DTH effector cells with sMRBC-induced EVs decreased the activation of T cells but enhanced their apoptosis. Finally, EVs coated with antibody light chains inhibited hapten-induced CHS.

Conclusions and Clinical Relevance:

The current study describes a newly discovered mechanism of self-tolerance induced by the intravenous delivery of a high dose of sMRBC that is mediated by EVs in a miRNA-150-dependent manner. This mechanism implies the concept of naturally occurring immune tolerance, presumably activated by overloading of the organism with altered self-antigens.

Keywords: delayed-type hypersensitivity to self-antigen, extracellular vesicles, immune suppression, miRNA-150, mouse model of delayed-type hypersensitivity to self-antigen, self-tolerance

Introduction

Peripheral immune tolerance to self-antigens is conferred by immune cells expressing regulatory phenotypes, including different T cell subsets.1,2 However, regulatory T (Treg) cell-mediated tolerance can be broken quite easily.3 This promotes development of autoimmunity, drawing attention to the clinical importance of newly elaborated methods that enable the preservation or restoration of immune regulatory cell activity. Some of the currently investigated approaches are based on the observation that antigen coupled to autologous cells induces tolerance rather than effector responses.4 Accordingly, autologous erythrocytes were proposed to constitute good carriers of antigens to induce specific Treg cells.5

Along these lines, recent findings revealed that intravenous administration of a high dose of syngeneic mouse red blood cells (sMRBC) coupled with hapten or protein antigen induces CD8+ suppressor T (Ts) cells in mice.6,7 These regulatory cells inhibit contact (CHS) or delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) reactions by releasing miRNA-150-carrying extracellular vesicles (EVs), further coated with B1 cell-derived, antigen-specific antibody free light chains (LCs).8–15 It is worth noting that surface expression of LCs confers antigen-specificity of tolerance mediated by EV-carried miRNA-150.11 Simultaneously, mice merely injected with a high dose of sMRBC alone generate EVs capable of inhibiting the function of antigen-presenting macrophages,14 which implies their tolerogenic potential and possible self-protecting activity. Therefore, our current study aimed to investigate the immune effects induced by EVs generated in response to mere intravenous administration of a high dose of sMRBC in mice. We also assessed the self-protecting potential of EVs by establishing a new model of DTH to sMRBC.

Methods

Mice

Ten- to 12-week-old male mice (C57BL/6, miRNA-150−/− and CBA inbred strains) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), and some of the CBA mice were obtained from the Breeding Unit of the Jagiellonian University Medical College, Faculty of Medicine (Krakow, Poland). Mice were fed autoclaved food and water ad libitum. This study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the European Union Directive 2010/63/EU and the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of laboratory animals and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Yale University, New Haven, CT (Permit Number 07381) and 1-st Local Ethics Committee of the Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland (Permit Number 39/2011, 40/2011, 106/2012 and 124/2018). All procedures were performed under ether or isoflurane anaesthesia, and all efforts were made to minimize suffering. The experimental design is depicted in Fig. 1.

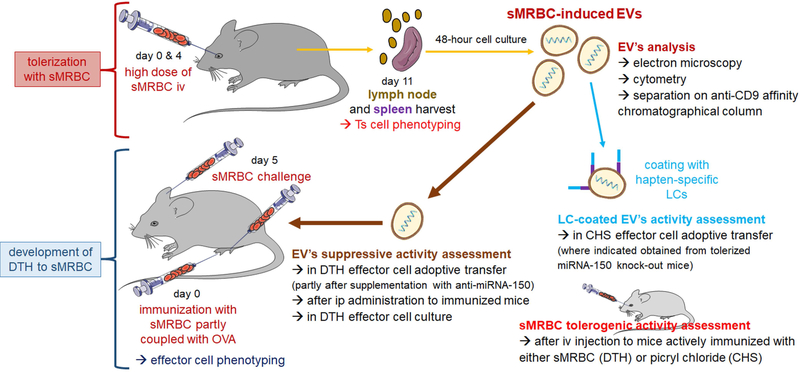

Fig. 1. Experimental design.

To induce immune tolerance, mice were intravenously (iv) injected with a high dose of syngeneic red blood cells (sMRBC) at days 0 and 4, and 7 days later lymph nodes and spleens were collected for phenotyping and culturing of suppressor T (Ts) cells that release sMRBC-induced extracellular vesicles (EVs). Otherwise, mice were intradermally injected into footpads with sMRBC mixed with ovalbumin (OVA)-coupled sMRBC, and 5 days later were intradermally injected into footpads and ears with sMRBC alone to elicit delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) reaction, with phenotyping of effector cells. Further, sMRBC-induced EVs were analyzed for their biological properties and immune function in DTH and, after coating with hapten-specific antibody light chains (LCs), in contact hypersensitivity (CHS).

Induction and elicitation of active DTH to self-antigens of sMRBC

Freshly collected sMRBC in 50% DPBS suspension were coupled with ovalbumin (OVA, Sigma, St Louis, MO) by incubation with 1% OVA solution in DPBS (in a ratio 1:5 v/v) for 60 minutes at room temperature on a haematological roller in the presence of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC, Pierce, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).11

Naive or sMRBC-tolerized mice were actively immunized with sMRBC by intradermal injection of 50 μl of 10% suspension of the 1:1 mixture of sMRBC and OVA-coupled sMRBC in 0.9% NaCl into each hind footpad. Five days later, immunized mice were challenged by intradermal injections with 10 μl of 20% sMRBC in 0.9% NaCl per ear and with 15 μl of 20% sMRBC in 0.9% NaCl per footpad into both ears or both hind limbs, respectively, to elicit DTH. The resulting ear and footpad swelling was measured between 24 and 120 hours after challenge with an engineer’s micrometer by a blinded observer, as described below. Where indicated, mice immunized with the sMRBC/OVA-sMRBC-mixture were challenged with 20% sheep red blood cell (SRBC) suspension in 10 μl or 15 μl of 0.9% NaCl injected into the ear or footpad, respectively, to assess the antigen specificity of the developed DTH swelling response. Additionally, just after measuring the 24-hour DTH swelling response, some mice were intraperitoneally administered with sMRBC-induced EVs. Where indicated, blood serum was collected from sMRBC-immunized mice 48 hours after challenge.

Adoptive transfer of sMRBC-induced DTH effector cells

Five days after immunization with sMRBC/OVA-sMRBC, mice were sacrificed, and lymph nodes and spleens were collected to enrich for DTH effector cells. Where indicated, DTH effector cells were depleted using monoclonal antibodies against CD4 (clone GK1.5) or CD8 (clone 53–6.7 TIB-105) with added rabbit complement for 1 hour in a 37°C water bath. All hybridoma cells were from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and antibodies were obtained and chromatographically purified at the Department of Immunology, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Krakow, Poland. Otherwise, cells were positively selected with CD4 (L3T4) MicroBeads separated on a MiniMACS MS column according to the manufacturer’s procedure (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). The efficacy of magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) was then assessed with flow cytometry and reached 95%. DTH effector cells were treated either with miRNA-150 alone or with sMRBC-induced EVs, in some cases supplemented with anti-miR-150, for 30 minutes in a 37°C water bath.9 After washing, DTH effector cells were transferred intravenously (7×107 cells per mouse) into naive recipients; 24 hours later, the recipients were challenged with sMRBC to elicit a DTH response. This newly elaborated methodology was partly modelled on the DTH response to SRBC.16 In parallel, lymph node DTH effector cells were cultured for 24 hours in the presence of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies (clone 145–2C11 CRL-1975, ATCC, antibodies were produced and chromatographically purified at the Department of Immunology, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Krakow, Poland) and/or sMRBC-induced EVs to produce culture supernatant. Along with blood sera, the supernatant was further used to measure IFNγ concentrations by ELISA (according to the manufacturer’s instructions with the use of Mouse IFNγ ELISA Ready-SET-Go kit, eBioscience Inc., San Diego, CA). Blood sera were also subjected to direct haemagglutination to determine the potential presence of antibodies against sMRBC.14

Intravenous administration of sMRBC (tolerization) and harvesting of EVs

On day 0 and 4, CBA or miRNA-150−/− mice were intravenously injected with 0.2 ml of 10% DPBS suspension of sMRBC.14 On day 11, lymph nodes and spleens were collected, and single cell suspension (2×107 cells per ml) was cultured in protein-free Mishell-Dutton medium for 48 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2 after enriching for CD8+ cells by MACS or depleting CD3+ cells with specific antibodies and rabbit complement, where indicated, with efficacy reaching 92% and 100%, respectively.9,10,13,14 The resulting culture supernatant was subsequently centrifuged at 300 g and 3,000 g to remove cellular debris, filtered through 0.45 μm and 0.22 μm molecular filters and then ultracentrifuged twice at 100,000 g for 70 minutes at 4°C. Pelleted EVs were resuspended in DPBS and, in some instances, incubated overnight on ice with anti-hapten (trinitrophenol, TNP, or oxazolone, OX) monoclonal antibody LCs,9,11,14 produced as formerly described.17 This was followed by ultracentrifugation to remove unbound LCs. Further, EVs from miRNA-150−/− mice were additionally incubated overnight on ice with synthetic miRNA-150 (mmu-miR-150–5p, GE Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO), followed by ultracentrifugation to remove excessive miRNA molecules. Otherwise, sMRBC-induced EVs of wild type mice were supplemented with anti-miR-150 (mmu-miR-150–5p hairpin inhibitor, GE Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) with a 1-hour incubation at 37°C.9 Finally, sMRBC-induced EVs were visualized by transmission electron microscopy or were separated by affinity chromatography on columns filled with CNBr-activated Sepharose (GE Healthcare, Boston, MA) conjugated to anti-CD9 monoclonal antibodies (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA).9

Cytometric analysis of sMRBC-induced EVs

DPBS-resuspended EVs were coated onto aldehyde/sulfate latex beads (4% w/v, 4 μm; Life Technologies, ThermoFisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA) for 2 hours at room temperature with gentle agitation. Then, any remaining binding sites were blocked with 1 ml of 100 mM glycine solution by a 30-minute incubation at room temperature with gentle agitation. After extensive washing in DPBS with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 600 g, bead-coated EVs were stained with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated monoclonal antibodies against mouse CD9 (clone KMC8), CD63 (clone NVG-2) or CD81 (clone Eat2) molecules and with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated monoclonal antibody against mouse kappa light chains (clone 187.1, all from BD Bioscience) for 40 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Cells were then washed with 0.1% BSA, and acquired by a BD FACSCalibur, with data analysis using BD CellQuest Pro software (Supplementary Fig. 1A).

DTH effector cell culture

Thioglycollate-induced peritoneal macrophages were pulsed with sMRBC by a 20-minute incubation at 37°C in water bath, followed by osmotic shock to remove non-phagocytosed sMRBC. DTH effector cells (1×106 cells per well) from the draining lymph nodes of mice immunized with sMRBC were stimulated with either anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies (2.4 μg/well) and IL-2 (3 U/well) or with sMRBC-pulsed macrophages (1×105 cells per well). They were then partly treated with sMRBC-induced EVs and cultured for either 3 hours to assess apoptosis; 18 hours to assess CD69 expression; or 24 hours to analyse expression of CD25, CD62L and CD44 markers on CD4+ cells by flow cytometry with the use of annexin-V and propidium iodide or fluorescent monoclonal antibodies (all from BD Biosciences, Supplementary Fig. 1B).

Induction and elicitation of active or adoptively transferred CHS reaction

Naive or sMRBC-tolerized mice were actively contact sensitized and 5 days later challenged with picryl chloride (PCL, Chemtronix, Swannanoa, NC) as described elsewhere.9,10,12,14 After 24 hours, ear swelling was measured with an engineer’s micrometer (Mitutoyo, Japan) by a blinded observer.18 Background nonspecific increases in ear thickness in non-sensitized, but similarly challenged, littermates were subtracted from experimental groups to yield a net swelling value expressed as delta ± standard error (SE) [U×10−2 mm]. OX hapten (Sigma, St Louis, MO) in 3% solution was selected to efficiently sensitize miRNA-150−/− and C57BL/6 mice.9–11 CHS effector cells were collected 5 days after sensitization with PCL or OX and then treated with various vesicle preparations for 30 minutes at 37°C in water bath.9,10 These cells were then intravenously transferred (7×107 cells per mouse) into naive recipients that were immediately challenged to elicit CHS ear swelling, as measured as above.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was carried out at least 2 times, and the results of representative experiments are shown in the figures. Experimental and control groups consisted of 4–6 mice. Average values of nonspecific increases of ear thickness due to chemical irritation by vehicle and hapten in challenged, but not sensitized mouse littermates, were subtracted from average values in experimental groups to obtain a net swelling value (delta). In the case of in vitro tests, the results of repeated experiments were pooled for statistical analysis. Statistical significance of the data was estimated (after control of meeting of test assumptions) by one-way or two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with post hoc RIR Tukey test or two-tailed Student’s t test, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

DTH to self-antigens of red blood cells is mediated by CD4+ T cells and macrophages

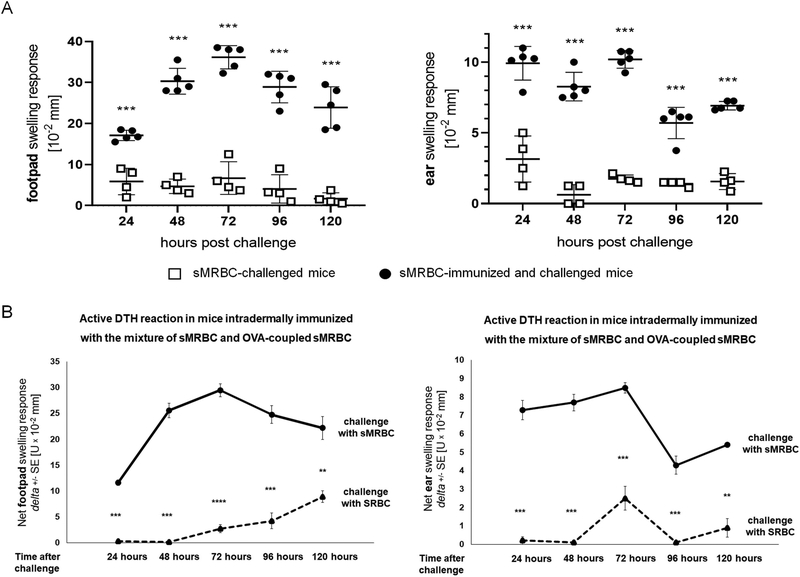

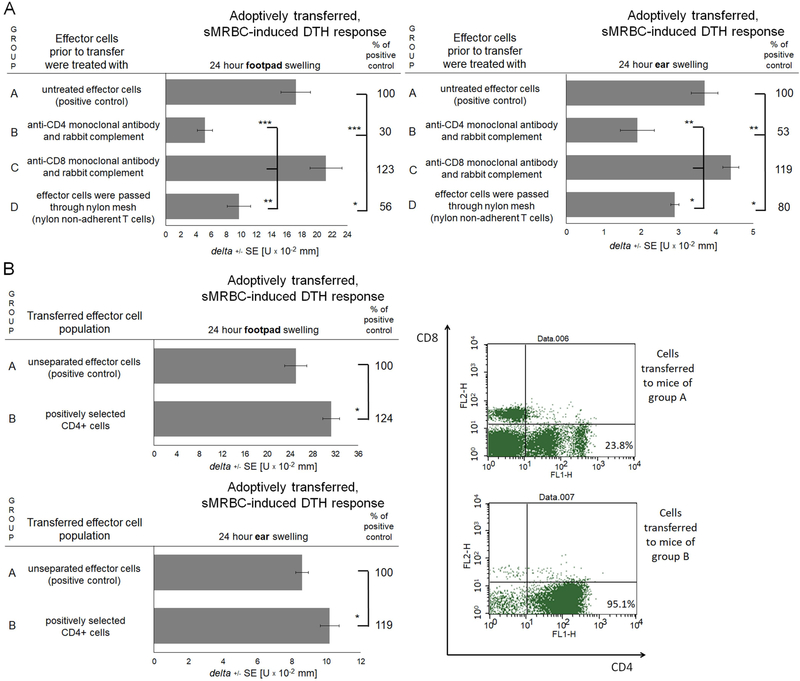

Measurable swelling of ear and footpad skin, peaking 48–72 hours after challenge, was detected in mice immunized with the mixture of sMRBC and OVA-sMRBC and challenged with sMRBC. Importantly, it was significantly greater than the background, non-specific swelling of ear and footpad skin caused by the administration of sMRBC to non-immunized littermates (Fig. 2A). To assess if the developed immune reaction was antigen-specific and directed against sMRBC antigens, we challenged OVA-MRBC/sMRBC-immunized mice with SRBC. This resulted in significantly lower net swelling of ear and footpad skin when compared to the response elicited by sMRBC (Fig. 2B). Adoptive transfer of lymph node cells and splenocytes of immunized mice allowed elicited skin swelling in recipient mice challenged with sMRBC (Fig. 3). However, depletion of CD4+ T cells greatly reduced the elicited skin swelling response mediated by the adoptively transferred DTH effector cells, similar to the removal of nylon-adherent cells, while depletion of CD8+ T cells slightly enhanced the swelling response (Fig. 3A). Additionally, adoptive transfer of positively selected CD4+ effector T cells induced a stronger DTH reaction in recipient mice than unseparated DTH effector cells (Fig. 3B). In parallel, sMRBC-agglutinating antibodies were not detected in the sera of mice actively immunized with sMRBC (data not shown). Altogether, the above results indicate that the immune response to sMRBC is mediated by CD4+ helper T lymphocytes and macrophages, which is typical for the effector phase of a classical DTH reaction.19

Fig. 2. CBA mice can be antigen-specifically immunized with syngeneic mouse red blood cells (sMRBC) to elicit delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) reaction.

(A) Footpad (left graph) or ear (right graph) swelling response of mice that were either only challenged by intradermal injection of sMRBC (open squares) or firstly immunized by intradermal injection of sMRBC mixed with ovalbumin-coupled sMRBC into footpad skin and then similarly challenged by intradermal injection of sMRBC into footpad or ear skin (black dots), measured up to 120 hours after challenge. Bars represent the mean and standard deviation. (B) Footpad (left graph) or ear (right graph) swelling response of mice that were immunized by intradermal injection of sMRBC mixed with ovalbumin-coupled sMRBC into footpad skin and then challenged by intradermal injection of either sMRBC (solid line) or sheep red blood cells (SRBC, dotted line) into footpad or ear skin, measured up to 120 hours after challenge. Two-tailed Student’s T test (n=5). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

Fig. 3. Delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) reaction to syngeneic mouse red blood cells (sMRBC) is mediated by lymph node and spleen CD4+ T cells.

(A) Footpad (left graph) or ear (right graph) swelling response of mouse recipients of either total population of lymph node and spleen DTH effector cells induced by intradermal injection of sMRBC mixed with ovalbumin-coupled sMRBC in group A or negatively selected DTH effector cells; i.e. depleted of CD4+ cells in group B, depleted of CD8+ cells in group C or deprived of nylon-adherent cells in group D. (B) Footpad (upper graph) or ear (lower graph) swelling response of mouse recipients of either total population of lymph node and spleen DTH effector cells induced by intradermal injection of sMRBC mixed with ovalbumin-coupled sMRBC in group A or positively selected CD4+ DTH effector cells in group B, with cytometric control of selection efficacy (right panel). One-way ANOVA with RIR Tukey test or two-tailed Student’s T test (n=5). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

DTH to self-red blood cells is suppressed by sMRBC-induced EVs in a miRNA-150-dependent manner

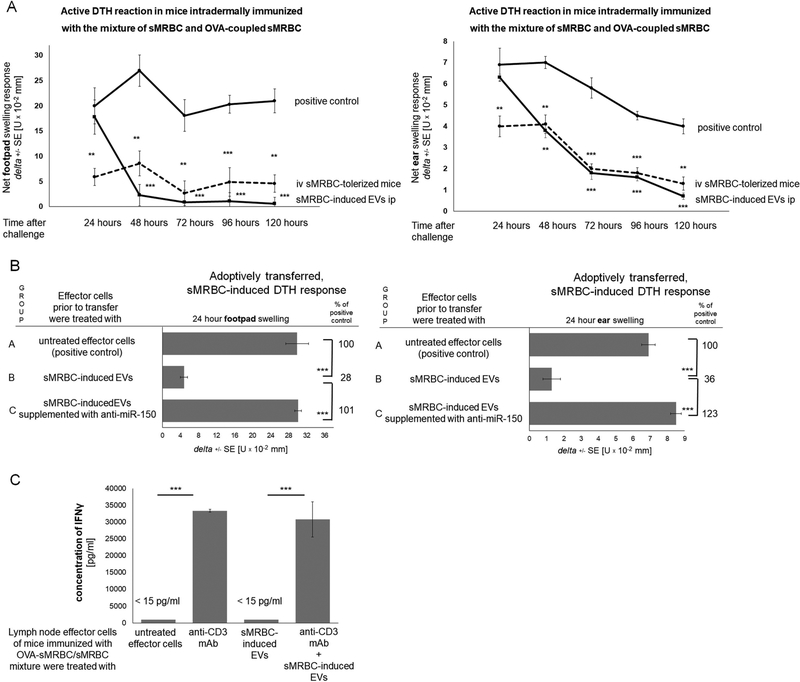

Subsequently, we investigated whether intravenous administration of sMRBC and induced EVs suppress DTH to self-red blood cells. Accordingly, sMRBC-tolerized mice developed an inhibited DTH reaction, similar to mice that received an intraperitoneal injection of sMRBC-induced EVs 24 hours after challenge (Fig. 4A). Further, treatment of DTH effector cells with sMRBC-induced EVs led to significant suppression of the skin swelling elicited in adoptively transferred recipients, while supplementation of sMRBC-induced EVs with anti-miR-150 completely blocked their suppressive activity (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. Delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) reaction to syngeneic mouse red blood cells (sMRBC) can be suppressed by intravenous (iv) administration of sMRBC and the resulting extracellular vesicles (EVs) acting in a miRNA-150-dependent manner.

(A) Footpad (left graph) or ear (right graph) swelling response either of mice immunized by intradermal injection of sMRBC mixed with ovalbumin-coupled sMRBC (OVA-sMRBC) into footpad skin and then challenged by intradermal injection of sMRBC (solid line with circles), or of mice that had been intravenously administered with sMRBC prior to immunization (dotted line with circles), or of mice intraperitoneally (ip) administered with sMRBC-induced EVs 24 hours after challenge (solid line with squares), measured up to 120 hours after challenge. (B) Footpad (left graph) or ear (right graph) swelling response of mouse recipients of either untreated DTH effector cells induced by intradermal injection of sMRBC mixed with OVA-sMRBC in group A, or DTH effector cells treated prior to transfer with sMRBC-induced EVs in group B, or DTH effector cells treated prior to transfer with sMRBC-induced EVs supplemented with anti-miR-150 (miRNA-150 hairpin inhibitor) in group C. (C) The concentration of interferon gamma (IFNγ) released to 24-hour culture supernatant by lymph node DTH effector cells induced by intradermal injection of sMRBC mixed with OVA-sMRBC and cultured alone or in the presence of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies (mAb) and/or sMRBC-induced EVs. One-way ANOVA with RIR Tukey test (n=5). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

However, while we did not detect IFNγ in the blood sera of mice in each treatment group shown in Fig. 4A (data not shown), lymph node effector cells from mice immunized with a mixture of sMRBC/OVA-sMRBC released vast amounts of IFNγ into the culture supernatant after stimulation with anti-CD3, and the addition of sMRBC-induced EVs failed to significantly modulate this effect (Fig. 4C). This supports our hypothesis on the DTH nature of the immune response to sMRBC.

sMRBC-induced EVs are produced by CD3+CD8+ Ts cells and express CD9 and CD81 tetraspanins

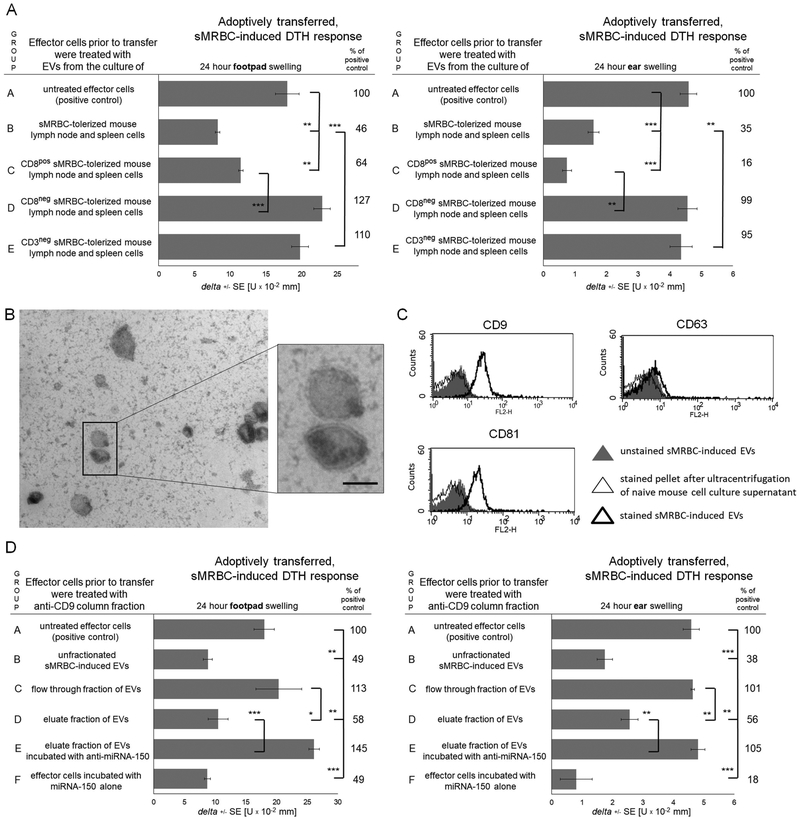

To determine the phenotype of EV-releasing cells, we enriched CD8+ T cells or depleted CD3+ lymphocytes from sMRBC-tolerized mouse lymph nodes and spleens prior to culture. Accordingly, EVs produced by enriched CD8+ T cells suppressed adoptively transferred DTH effector cells, while EVs released by populations deprived of CD8+ or CD3+ T cells failed to inhibit the transferred DTH response (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5. Syngeneic mouse red blood cell (sMRBC)-induced extracellular vesicles (EVs) are generated by CD3+CD8+ T cells and express CD9 and CD81 tetraspanins.

(A) Footpad (left graph) or ear (right graph) swelling response of mouse recipients of unaffected delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) effector cells in group A, or DTH effector cells pretreated with aMRBC-induced EVs produced by tolerized mouse lymph node and spleen cells cultured either as total population in group B, or after enrichment of CD8+ cells in group C, or after depleting of CD8+ or CD3+ cells in groups D and E, respectively. (B) Electron microscopy analysis of sMRBC-induced EVs (bar express 100 nm). (C) Cytometric analysis of sMRBC-induced EVs with staining against CD9, CD63 or CD81 vesicle markers. (D) Footpad (left graph) or ear (right graph) swelling response of mouse recipients of untreated DTH effector cells in group A, or DTH effector cells treated prior to transfer with either unfractionated sMRBC-induced EVs in group B, or EVs passing through anti-CD9 affinity column in group C, or EVs eluted from anti-CD9 column alone in group D or supplemented with anti-miR-150 (miRNA-150 hairpin inhibitor) in group E, or of recipients of DTH effector cells pretreated with miRNA-150 alone. One-way ANOVA with RIR Tukey test (n=4–5). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

Further, electron microscopy revealed the presence of EVs with a bilamellar membrane, resembling exosome-like nanovesicles, in the culture supernatant of lymph node and spleen cells of sMRBC-tolerized mice (Fig. 5B). By means of flow cytometry, sMRBC-induced EVs were shown to express CD9 and CD81 but not CD63 tetraspanins (Fig. 5C). Subsequent fractionation of the sMRBC-induced EVs on an anti-CD9 affinity column showed that CD9+ EVs present in the column eluate suppress the DTH reaction and that this effect is prevented by supplementation of eluted EVs with anti-miR-150 (Fig. 5D). Additionally, incubation of effector cells with miRNA-150 alone suppressed the transferred DTH reaction (Fig. 5D).

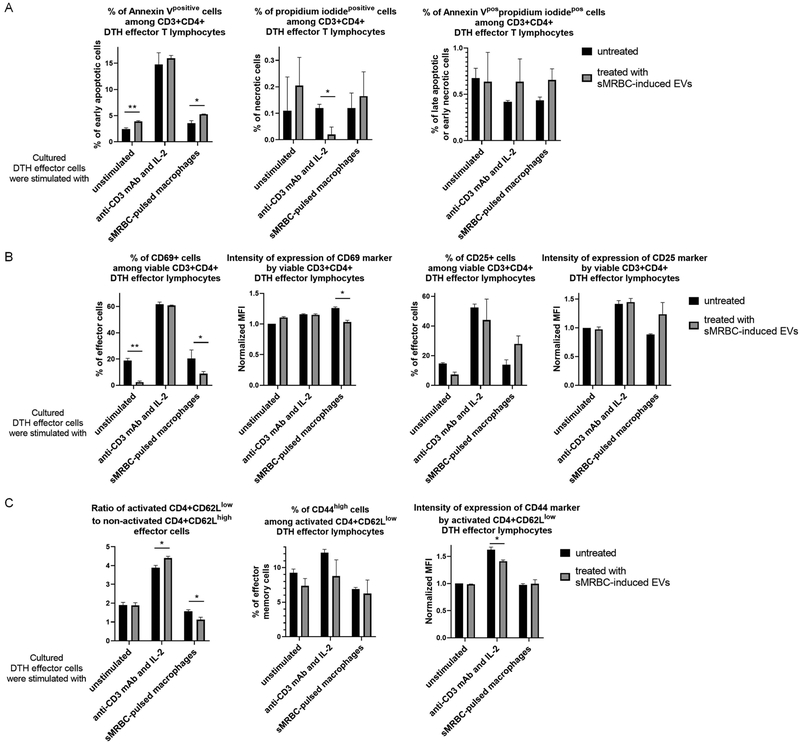

In vitro treatment of DTH effector cells with sMRBC-induced EVs enhances apoptosis and impairs CD4+ effector T cell activation

To determine the possible mechanism underlying the suppressive activity of EVs, we treated DTH effector cells with sMRBC-induced EVs and then cultured them with either IL-2 and anti-CD3 antibodies or with sMRBC-pulsed macrophages. Afterwards, the viability and activation of CD4+ T cells were assessed. In the case of unstimulated DTH effector T cells, an increased percentage of early apoptotic cells was detected (Fig. 6A) along with a decreased percentage of CD69-expressing T lymphocytes (Fig. 6B). A similar trend was observed when analysing CD25 expression (Fig. 6B). Re-stimulation of EV-treated DTH effector T cells with IL-2 and anti-CD3 antibodies resulted in a decreased percentage of necrotic cells (Fig. 6A) and intensity of CD44 expression by activated T cells, simultaneously increasing the ratio of CD62Llow to CD62Lhigh cells (Fig. 6C).20 In the case of EV-treated DTH effector T cells cultured with sMRBC-pulsed macrophages, an increased percentage of early apoptotic cells (Fig. 6A), decreased percentage of CD4+CD69+ cells and reduced intensity of CD69 expression were observed (Fig. 6B). Analogously, a decreased ratio of CD62Llow to CD62Lhigh cells was determined (Fig. 6C). However, these cells tended to increase their expression of CD25 after culture with sMRBC-pulsed macrophages (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6. Syngeneic mouse red blood cell (sMRBC)-induced extracellular vesicles (EVs) increase the apoptosis and decrease the activation of delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) effector cells.

(A) Cytometrically assessed percentage of CD3+CD4+ DTH effector cells that are positive in staining with annexin-V and/or propidium iodide, after 3-hour culture in the presence (gray bars) or absence (black bars) of sMRBC-induced EVs. (B) Percentage of viable CD3+CD4+ DTH effector cells that express either CD69 or CD25 markers and geometric mean of fluorescence intensity (MFI) of fluorescent dyes conjugated to monoclonal antibodies (mAb) binding to either CD69 or CD25 markers, cytometrically evaluated after 18- or 24-hour culture in the presence (gray bars) or absence (black bars) of sMRBC-induced EVs. (C) Ratio of activated to non-activated DTH effector cells calculated as the percentage of CD62Llow cells divided by the percentage of CD62Lhigh cells, among CD3+CD4+ T lymphocytes, or percentage of CD4+CD62Llow DTH effector cells that highly express CD44 marker with geometric mean of fluorescence intensity (MFI) of fluorescent dye conjugated to mAb against CD44, cytometrically evaluated after 24-hour culture in the presence (gray bars) or absence (black bars) of sMRBC-induced EVs. MFI has been normalized to the value obtained while analyzing control group of unstimulated and EV-untreated cells. Graph bars depict mean ± standard deviation (SD). Two-way ANOVA with RIR Tukey test (n=4). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Similar tendencies were observed in the case of tolerized mice and naive human T cells treated with sMRBC-induced EVs in the presence of antigen-presenting cells (APCs, Supplementary Fig. 2 and 3). Additionally, our preliminary data suggest that miRNA-150 may downregulate the IL-2-dependent viability of effector cells (Supplementary Fig. 4).

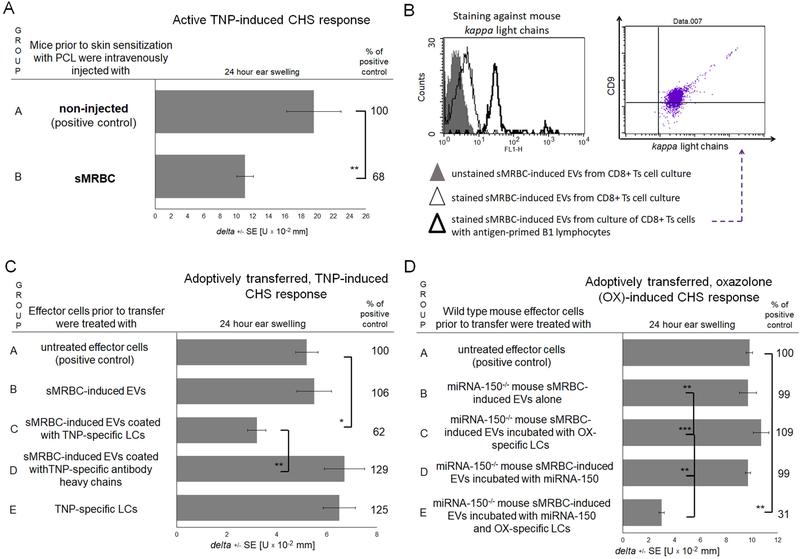

sMRBC-induced EVs suppress hapten-induced CHS after coating with hapten-specific antibody LCs

Next, we attempted to investigate whether the tolerogenic activity of sMRBC is limited solely to DTH against self-antigens. Thus, we tolerized mice with sMRBC prior to skin sensitization with hapten, which inhibit the elicited ear swelling response (Fig. 7A). This effect may have resulted from the resulting surface coating of sMRBC-induced EVs with hapten-specific LCs provided by hapten-activated B1 cells.11 To test this hypothesis, we cytometrically analysed the expression of mouse kappa LCs on sMRBC-induced EVs originating from CD8+ Ts cells, cultured alone or with hapten-primed B1 lymphocytes, showing that sMRBC-induced EVs acquire LC-coating in the presence of B1 cells (Fig. 7B). Thus, we pre-incubated sMRBC-induced EVs with TNP-specific LCs prior to treatment of adoptively transferred CHS effector cells, which rendered them fully suppressive, in contrast to coating with specific antibody heavy chains (Fig. 7C). This observation was reproduced in the dose response experiment (Supplementary Fig. 5). Simultaneously, further results implied that this effect is mediated by the buoyant fraction of EVs (Supplementary Fig. 6A) induced by intravenous administration of sMRBC, but not of allogeneic or xenogeneic erythrocytes (Supplementary Fig. 6B), and depends on the RNA cargo of the EVs (Supplementary Fig. 7). This suggested that LC-coated, sMRBC-induced EVs suppress CHS in a miRNA-150-dependent manner. To verify this assumption, we tolerized miRNA-150−/− mice with sMRBC, but their derived EVs failed to suppress adoptively transferred CHS effector cells, even when pre-incubated with either hapten-specific LCs or synthetic miRNA-150 (Fig. 7D). However, pre-incubation of sMRBC-induced EVs from miRNA-150−/− mice with hapten-specific LCs and synthetic miRNA-150 together rendered them fully suppressive (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7. Syngeneic red blood cell (sMRBC)-induced extracellular vesicles (EVs) gain full suppressive activity in contact hypersensitivity (CHS) to trinitrophenol (TNP) or oxazolone (OX) hapten after coating with hapten-specific antibody light chains (LCs).

(A) Ear swelling response of mice actively sensitized with picryl chloride (PCL) in group A or intravenously injected with sMRBC prior to active sensitization in group B. (B) Cytometric analysis of sMRBC-induced EVs, that had been produced by either enriched CD8+ suppressor T (Ts) cells cultured alone or with antigen-primed B1 lymphocytes, and stained against mouse antibody kappa light chains and CD9 tetraspanin. (C) Ear swelling response of mouse recipients of unaffected CHS effector cells in group A or of CHS effector cells treated with either non-supplemented sMRBC-induced EVs in group B or EVs supplemented with antibody light or heavy chains in groups C and D, or of CHS effector cells incubated with LCs alone in group E. (D). Ear swelling response of mouse recipients of unaffected CHS effector cells in group A or of CHS effector cells treated with miRNA-150−/− mouse sMRBC-induced EVs alone in group B, or supplemented with synthetic miRNA-150 mimic and/or OX-specific LCs in groups C-E. One-way ANOVA with RIR Tukey test or two-tailed Student’s T test (n=5). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

Discussion

Administration of OVA-altered sMRBC via the intradermal route, which is considered immunogenic,15 results in the breaking of immune tolerance and subsequent development of immune responses against self-erythrocytes. Positive and negative selection assays have revealed that the immune response to altered sMRBC is mediated by CD4+ T cells and macrophages. Furthermore, it peaks at 48–72 hours post-challenge and is also measurable at a site distant (ear skin) to the area of initial antigen deposition (footpad skin).21 Upon stimulation, lymph node cells of mice immunized with sMRBC released IFNγ, while immunized mouse blood sera did not contain antibodies agglutinating sMRBC. Thus, these overall characteristics confirm that the immune response to sMRBC is a classical DTH reaction mediated by CD4+ helper T cells activating the cytotoxic function of macrophages. This further implies that IFNγ-producing CD4+ Th1 cells dominate the effector cell population.22

Some self-reactive T cells escape negative selection in the thymus,3 and their responsiveness seems to positively correlate with the dose of self-antigen.23 In such conditions, immune tolerance is conferred by Treg cells but is less durable and can be quite easily broken by challenges with antigen.3 Furthermore, in the current circumstances, breaking of tolerance was additionally facilitated by delivering self-antigen together with a foreign, immunogenic protein. Thus, after extravascular delivery, OVA-altered sMRBC undergo phagocytosis by infiltrating macrophages and skin resident APCs that then present the resulting immunogenic determinants to naive CD4+ T cells, beginning the induction phase of the DTH reaction.15,19 Consequently, proliferating effector T cells are reactive to sMRBC self-antigens, allowing initiation of the effector phase of DTH by subsequent intradermal injection of intact sMRBC.

On the other hand, intravenous administration of sMRBC causes sudden alterations in blood parameters, including viscosity, due to the elevated blood volume and increased number of circulating erythrocytes. Consequently, this drives compensatory mechanisms to restore physiological conditions, including removal of excessive, altered or senescent blood cells by hepatic and splenic macrophages,24,25 which have recently been proposed to activate Treg cells.26 However, in the currently studied conditions, delivery of sMRBC in a huge excess likely led to the overloading of phagocytosing macrophages, which forced them to ensure the protection of self-antigens against eventual recognition by self-reactive cells. This resulted in the generation of EVs by Ts cells. Our previous data, consistent with this prediction, demonstrated that depletion of clodronate-sensitive cells, mostly macrophages, prior to tolerization significantly impairs the generation of suppressive EVs.14 Thus, circulating sMRBC-induced EVs seem to confer protection against possible autoimmunization, likely by delivering regulatory miRNA-150. Instead, when these self-protecting EVs gain surface coating with antigen-specific LCs, they become redirected towards the suppression of immune responses against the corresponding antigen. Since the excessive inflammatory reaction to nonpathogenic antigens could be self-damaging, in this regard, LC-coated EVs still preserve their self-protecting function.

Furthermore, haptenation of self-proteins leads to the development of allergies and hypersensitivities in susceptible individuals.27 Thus, hapten-specific LC-coated, sMRBC-induced EVs, redirected towards the suppression of sensitized effector cells, would greatly support the activation of immune tolerance to the hapten. This opens up the possibility to therapeutically induce immune tolerance to a particular allergen but also suggests that LC-coated EVs may mediate the naturally occurring, possibly miRNA-150-dependent, immune tolerance to haptens in non-allergic individuals, which requires further investigation.

Along these lines, one can speculate that, in some circumstances, DTH-inducing allergens, such as haptens, may bind to host erythrocytes while passing to the circulation. These in turn would be sensed by splenic and hepatic macrophages, ultimately activating Ts cell release of EVs. Hence, as mentioned before, sMRBC-induced EVs presumably may be considered as mediators of the possible, naturally occurring mechanism of immune tolerance to DTH-inducing allergens. Validity of this speculation may be supported by the fact that not all individuals exposed to contact allergens suffer from contact allergy.

Our research findings demonstrate that sMRBC alone or conjugated with contact allergens induce immune tolerance after systemic injection of a high dose.6,9,10,14 This is in line with studies by Cremel et al. highlighting the role of erythrocytes as carriers for immunogenic antigens that make them tolerogenic after intravenous administration.28 Interestingly, it was reported that intravenous administration of MRBC coupled with OVA and then treated with [bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)] suberate (BS3), a chemical promoting liver targeting, prior to immunization with OVA mixed with an adjuvant downregulated the response of OVA-specific CD8+ T cells and B lymphocytes and increased the number of splenic Treg cells. Instead, in those conditions, administration of MRBC treated with BS3 alone failed to significantly modulate the immune response triggered by immunization with OVA mixed with an adjuvant.28 However, compared to our current experimental settings, crucial differences include the immunization protocols and the means of MRBC treatment prior to injections. In the discussed study, stored sMRBC were treated with a liver targeting promoter and then partly reconstituted with mouse plasma. In contrast, in our conditions, freshly collected sMRBC deprived of buffy coat were used as a plain DPBS suspension. Furthermore, while boosting of mice with OVA in the presence of various adjuvants triggers cytotoxic T cell responses and the production of antibodies,28 epicutaneous sensitization with hapten alone or intradermal immunization with OVA without an adjuvant induces CHS or DTH reactions, respectively.9,12,29 Finally, our current observations demonstrate that intradermal administration of sMRBC mixed with OVA-coupled sMRBC also induces a DTH reaction and that both hapten-induced CHS and DTH to self-erythrocytes could be antigen-specifically suppressed by intravenous administration of a high dose of intact sMRBC. Thus, the herein presented research findings contribute to our understanding of erythrocyte-induced immune tolerance by characterizing the underlying biological mechanism involving EVs that target APCs to ultimately suppress effector T cells.14

Accordingly, attempts to determine the mechanisms underlying the suppressive effects of sMRBC-induced EVs revealed that they diminish T cell activation by sMRBC-pulsed macrophages but not by anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies and IL-2.30–32 This seems to prove the involvement of APCs in the regulatory action of EVs, which is in line with the previously described crucial role of antigen-primed macrophages in the suppression of CHS effector T cells by miRNA-150-carrying EVs.14 Furthermore, we demonstrate the pro-apoptotic effect of sMRBC-induced EVs exerted on DTH effector T cells, which may result from miRNA-150 activity, as reported in the case of CD8+ memory T cell differentiation.33 In addition, sMRBC-induced EVs express anti-proliferative potential and influence the IL-2-dependent viability of HT-2 cells.14 These effects also seem to be regulated by miRNA-150 and are likely responsible for the eventual inhibition of the sMRBC-induced DTH reaction.34–36

It is worth noting that miRNA-150 is well known to regulate haematopoiesis, including erythropoiesis.37,38 Overexpression of miRNA-150 was recently shown to inhibit erythroid proliferation and terminal differentiation.39 Accordingly, miRNA-150-mediated inhibition of the release of matured erythrocytes from the bone marrow to the circulation would greatly support the process of restoration of homeostatic conditions after infusion of excessive sMRBC. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report that immune cells, namely, CD8+ Ts lymphocytes, contribute to the downregulation of erythropoiesis by releasing miRNA-150 in EVs after a significant systemic increase in red blood cell number.14

From another point of view, the transfusion-related immunomodulation (TRIM) effect is observed in critically ill patients transfused with allogeneic blood or packed red blood cells,40–42 supposedly leading to life threatening complications.43,44 Accordingly, replacement of allogeneic blood transfusions by the administration of autologous (syngeneic) blood or its products was suggested for clinical use to prevent adverse TRIM effects in severely injured individuals.45 Furthermore, our current data obtained in a mouse model indicate that, in particular circumstances, sMRBC infusion could induce immune tolerance to self- and nonpathogenic antigens. This in turn could exert beneficial effects by suppressing excessive or unwanted inflammatory responses in the prevention or alleviation of immune-related symptoms of allergies, hypersensitivities and autoimmune disorders, highlighting the clinical importance and translational potential of the herein described tolerance mechanism.

Additionally, DTH reactions to nonpathogenic antigens underlie the pathogenesis of various immune-related disorders, including contact dermatitis as well as celiac and Crohn’s diseases.19,46 In such conditions, therapeutic strategies to precisely induce immune tolerance to particular antigens, simultaneously preserving immune responsiveness to other antigens, would bring the most beneficial effects. In this regard, the currently described mechanism of DTH suppression expands our current understanding of the process of immune regulation via EVs and miRNAs and the possible means of its induction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The Authors express their gratitude to Michael Kozlowski, MD, who provided linguistic corrections of the manuscript; to Magdalena Wąsik, MSc, from the Department of Immunology, Jagiellonian University Medical College; and to collaborators from the Electron Microscopy Laboratory of Department of Pathology, Yale University School of Medicine, for their valuable technical support. The current study was supported by Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education [K/DSC/002102, K/ZDS/001429 and N41/DBS/000187], National Institutes of Health [AI-076366], and the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness [SAF2014–55579-R]. K.N. was subsidized by the European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO) Short-Term Fellowship at the Immunology Department of Hospital de la Princesa, Autonomous University of Madrid, Spain. The funding sources had no involvement in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or the decision on article submission.

Abbreviations

- APC

antigen-presenting cell

- CHS

contact hypersensitivity

- DPBS

Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline

- DTH

delayed-type hypersensitivity

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- EVs

extracellular vesicles

- LCs

light chains

- MRBC

mouse red blood cells

- OX

oxazolone

- OVA

ovalbumin

- PCE

phenol-chloroform extract

- PCL

picryl chloride

- SEE

Staphylococcal enterotoxin type E superantigen

- sMRBC

syngeneic mouse red blood cells

- SRBC

sheep red blood cells

- TNP

trinitrophenol

- Treg

regulatory T (cells)

- Ts

suppressor T (cells)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The Authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- 1.Filaci G, Fenoglio D, Indiveri F. CD8(+) T regulatory/suppressor cells and their relationships with autoreactivity and autoimmunity. Autoimmunity 2011;44:51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar P, Saini S, Khan S, Surendra Lele S, Prabhakar BS. Restoring self-tolerance in autoimmune diseases by enhancing regulatory T-cells. Cell Immunol 2018; (article in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Legoux FP, Lim JB, Cauley AW, Dikiy S, Ertelt J, Mariani TJ, Sparwasser T, Way SS, Moon JJ. CD4+ T cell tolerance to tissue-restricted self antigens is mediated by antigen-specific regulatory T cells rather than deletion. Immunity 2015;43:896–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pearson RM, Casey LM, Hughes KR, Miller SD, Shea LD. In vivo reprogramming of immune cells: Technologies for induction of antigen-specific tolerance. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2017;114:240–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grimm AJ, Kontos S, Diaceri G, Quaglia-Thermes X, Hubbell JA. Memory of tolerance and induction of regulatory T cells by erythrocyte-targeted antigens. Sci Rep 2015;5:15907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nazimek K, Wąsik M, Askenase PW, Bryniarski K. Intravenously administered contact allergens coupled to syngeneic erythrocytes induce in mice tolerance rather than effector immune response. Folia Med Cracov 2019;59:61–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ptak W, Rozycka D, Rewicka M. Induction of suppressor cells and cells producing antigen-specific suppressor factors by haptens bound to self carriers. Immunobiology 1980;156:400–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Askenase PW, Bryniarski K, Paliwal V, Redegeld F, Groot Kormelink T, Kerfoot S, Hutchinson AT, van Loveren H, Campos R, Itakura A, Majewska-Szczepanik M, Yamamoto N, Nazimek K, Szczepanik M, Ptak W. A subset of AID-dependent B-1a cells initiates hypersensitivity and pneumococcal pneumonia resistance. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2015;1362:200–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryniarski K, Ptak W, Jayakumar A, Püllmann K, Caplan MJ, Chairoungdua A, Lu J, Adams BD, Sikora E, Nazimek K, Marquez S, Kleinstein SH, Sangwung P, Iwakiri Y, Delgato E, Redegeld F, Blokhuis BR, Wojcikowski J, Daniel AW, Groot Kormelink T, Askenase PW. Antigen-specific, antibody-coated, exosome-like nanovesicles deliver suppressor T-cell microRNA-150 to effector T cells to inhibit contact sensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;132:170–181.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryniarski K, Ptak W, Martin E, Nazimek K, Szczepanik M, Sanak M, Askenase PW. Free extracellular miRNA functionally targets cells by transfecting exosomes from their companion cells. PLoS One 2015;10:e0122991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nazimek K, Askenase PW, Bryniarski K. Antibody light chains dictate the specificity of contact hypersensitivity effector cell suppression mediated by exosomes. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19:E2656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nazimek K, Bryniarski K, Askenase PW. Functions of exosomes and microbial extracellular vesicles in allergy and contact and delayed-type hypersensitivity. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2016;171:1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nazimek K, Nowak B, Marcinkiewicz J, Ptak M, Ptak W, Bryniarski K. Enhanced generation of reactive oxygen intermediates by suppressor T cell-derived exosome-treated macrophages. Folia Med Cracov 2014;54:37–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nazimek K, Ptak W, Nowak B, Ptak M, Askenase PW, Bryniarski K. Macrophages play an essential role in antigen-specific immune suppression mediated by T CD8⁺ cell-derived exosomes. Immunology 2015;146:23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ptak W, Nazimek K, Askenase PW, Bryniarski K. From mysterious supernatant entity to miRNA-150 in antigen-specific exosomes: a history of hapten-specific T suppressor factor. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2015;63:345–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith MJ, White KL Jr. Establishment and comparison of delayed-type hypersensitivity models in the B₆C₃F₁ mouse. J Immunotoxicol 2010;7:308–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Redegeld FA, van der Heijden MW, Kool M, Heijdra BM, Garssen J, Kraneveld AD, Van Loveren H, Roholl P, Saito T, Verbeek JS, Claassens J, Koster AS, Nijkamp FP. Immunoglobulin-free light chains elicit immediate hypersensitivity-like responses. Nat Med 2002;8:694–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zemelka-Wiącek M, Majewska-Szczepanik M, Pyrczak W, Szczepanik M. Complementary methods for contact hypersensitivity (CHS) evaluation in mice. J Immunol Methods 2013;387:270–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan DH, Igyártó BZ, Gaspari AA. Early immune events in the induction of allergic contact dermatitis. Nat Rev Immunol 2012;12:114–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harpaz I, Bhattacharya U, Elyahu Y, Strominger I, Monsonego A. Old mice accumulate activated effector CD4 T cells refractory to regulatory T cell-induced immunosuppression. Front Immunol 2017;8:283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen IC. Contact hypersensitivity models in mice. Methods Mol Biol 2013;1032:139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weaver CT, Harrington LE, Mangan PR, Gavrieli M, Murphy KM. Th17: an effector CD4 T cell lineage with regulatory T cell ties. Immunity 2006;24:677–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swee LK, Nusser A, Curti M, Kreuzaler M, Rolink R, Terracciano L, Melchers F, Andersson J, Rolink A. The amount of self-antigen determines the effector function of murine T cells escaping negative selection. Eur J Immunol 2014;44:1299–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Theurl I, Hilgendorf I, Nairz M, Tymoszuk P, Haschka D, Asshoff M, He S, Gerhardt LM, Holderried TA, Seifert M, Sopper S, Fenn AM, Anzai A, Rattik S, McAlpine C, Theurl M, Wieghofer P, Iwamoto Y, Weber GF, Harder NK, Chousterman BG, Arvedson TL, McKee M, Wang F, Lutz OM, Rezoagli E, Babitt JL, Berra L, Prinz M, Nahrendorf M, Weiss G, Weissleder R, Lin HY, Swirski FK. On-demand erythrocyte disposal and iron recycling requires transient macrophages in the liver. Nat Med 2016;22:945–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wojczyk BS, Kim N, Bandyopadhyay S, Francis RO, Zimring JC, Hod EA, Spitalnik SL. Macrophages clear refrigerator storage-damaged red blood cells and subsequently secrete cytokines in vivo, but not in vitro, in a murine model. Transfusion 2014;54:3186–3197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurotaki D, Uede T, Tamura T. Functions and development of red pulp macrophages. Microbiol Immunol 2015;59:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chipinda I, Hettick JM, Siegel PD. Haptenation: chemical reactivity and protein binding. J Allergy (Cairo) 2011;2011:839682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cremel M, Guérin N, Horand F, Banz A, Godfrin Y. Red blood cells as innovative antigen carrier to induce specific immune tolerance. Int J Pharm 2013;443:39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szczepanik M, Akahira-Azuma M, Bryniarski K, Tsuji RF, Kawikova I, Ptak W, Kiener C, Campos RA, Askenase PW. B-1 B cells mediate required early T cell recruitment to elicit protein-induced delayed-type hypersensitivity. J Immunol 2003;171:6225–6235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blas-Rus N, Bustos-Morán E, Pérez de Castro I, de Cárcer G, Borroto A, Camafeita E, Jorge I, Vázquez J, Alarcón B, Malumbres M, Martín-Cófreces NB, Sánchez-Madrid F. Aurora A drives early signalling and vesicle dynamics during T-cell activation. Nat Commun 2016;7:11389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bustos-Morán E, Blas-Rus N, Martin-Cófreces NB, Sánchez-Madrid F. Microtubule-associated protein-4 controls nanovesicle dynamics and T cell activation. J Cell Sci 2017;130:1217–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mittelbrunn M, Gutiérrez-Vázquez C, Villarroya-Beltri C, González S, Sánchez-Cabo F, González MÁ, Bernad A, Sánchez-Madrid F. Unidirectional transfer of microRNA-loaded exosomes from T cells to antigen-presenting cells. Nat Commun 2011;2:282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Z, Stelekati E, Kurachi M, Yu S, Cai Z, Manne S, Khan O, Yang X, Wherry EJ. miR-150 regulates memory CD8 T cell differentiation via c-Myb. Cell Rep 2017;20:2584–2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moles R, Bellon M, Nicot C. STAT1: A novel target of miR-150 and miR-223 is involved in the proliferation of HTLV-I-transformed and ATL cells. Neoplasia 2015;17:449–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trifari S, Pipkin ME, Bandukwala HS, Äijö T, Bassein J, Chen R, Martinez GJ, Rao A. MicroRNA-directed program of cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:18608–18613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sang W, Wang Y, Zhang C, Zhang D, Sun C, Niu M, Zhang Z, Wei X, Pan B, Chen W, Yan D, Zeng L, Loughran TP Jr, Xu K. MiR-150 impairs inflammatory cytokine production by targeting ARRB-2 after blocking CD28/B7 costimulatory pathway. Immunol Lett 2016;172:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams BD, Guo S, Bai H, Guo Y, Megyola CM, Cheng J, Heydari K, Xiao C, Reddy EP, Lu J. An in vivo functional screen uncovers miR-150-mediated regulation of hematopoietic injury response. Cell Rep 2012;2:1048–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He Y, Jiang X, Chen J. The role of miR-150 in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Oncogene 2014;33:3887–3893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun Z, Wang Y, Han X, Zhao X, Peng Y, Li Y, Peng M, Song J, Wu K, Sun S, Zhou W, Qi B, Zhou C, Chen H, An X, Liu J. miR-150 inhibits terminal erythroid proliferation and differentiation. Oncotarget 2015;6:43033–43047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blajchman MA. Immunomodulation and blood transfusion. Am J Ther 2002;9:389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blajchman MA. Transfusion immunomodulation or TRIM: what does it mean clinically? Hematology 2005;10(Suppl 1):208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blajchman MA, Bordin JO. Mechanisms of transfusion-associated immunosuppression. Curr Opin Hematol 1994;1:457–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vamvakas EC. Pneumonia as a complication of blood product transfusion in the critically ill: transfusion-related immunomodulation (TRIM). Crit Care Med 2006;34(5 Suppl):S151–S159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Torrance HD, Brohi K, Pearse RM, Mein CA, Wozniak E, Prowle JR, Hinds CJ, OʼDwyer MJ. Association between gene expression biomarkers of immunosuppression and blood transfusion in severely injured polytrauma patients. Ann Surg 2015;261:751–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vamvakas EC, Blajchman MA. Transfusion-related immunomodulation (TRIM): an update. Blood Rev 2007;21:327–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li N, Shi RH. Updated review on immune factors in pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease. World J. Gastroenterol 2018;24:15–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.