Summary

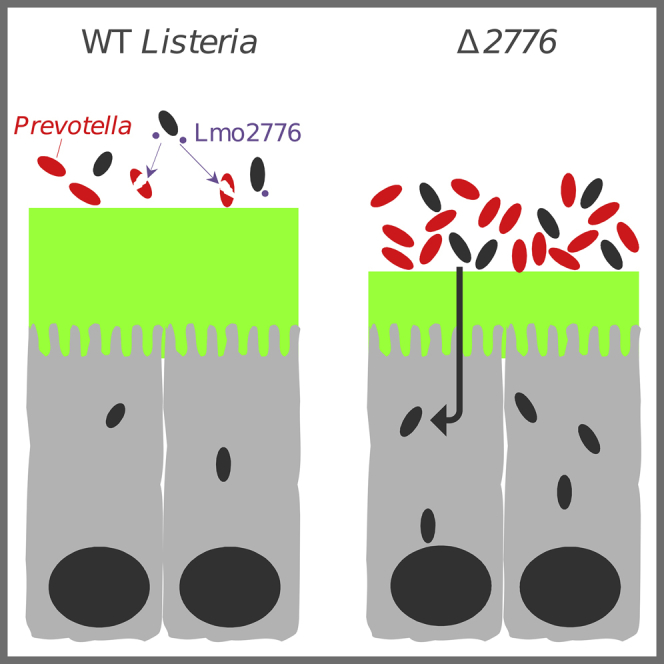

Understanding the role of the microbiota components in either preventing or favoring enteric infections is critical. Here, we report the discovery of a Listeria bacteriocin, Lmo2776, which limits Listeria intestinal colonization. Oral infection of conventional mice with a Δlmo2776 mutant leads to a thinner intestinal mucus layer and higher Listeria loads both in the intestinal content and deeper tissues compared to WT Listeria. This latter difference is microbiota dependent, as it is not observed in germ-free mice. Strikingly, it is phenocopied by pre-colonization of germ-free mice before Listeria infection with Prevotella copri, an abundant gut-commensal bacteria, but not with the other commensals tested. We further show that Lmo2776 targets P. copri and reduces its abundance. Together, these data unveil a role for P.copri in exacerbating intestinal infection, highlighting that pathogens such as Listeria may selectively deplete microbiota bacterial species to avoid excessive inflammation.

Keywords: Listeria monocytogenes, Prevotella copri, Bacteriocin, Lmo2776, microbiota, M-SHIME, infection

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

L. monocytogenes secretes a bacteriocin (Lmo2776) homologous to the lactococcin 972

-

•

Lmo2776 controls Listeria intestinal colonization in a microbiota-dependent manner

-

•

Lmo2776 targets the abundant gut commensal Prevotella copri

-

•

Presence of P. copri exacerbates infection

While studying the impact of a previously unknown Listeria monocytogenes bacteriocin on infection, Rolhion et al. identify P. copri, an abundant gut commensal, as the primary target of this bacteriocin in the gut microbiota and as a modulator of infection.

Introduction

Prevotella is classically considered a common commensal bacterium due to its presence in several locations of the healthy human body, including the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, urogenital tract, and skin (Larsen, 2017). The Prevotella genus encompasses more than 40 different culturable species of which three—P. copri (Pc), P. salivae (Ps), and P. stercorea—are members of the gut microbiota. Prevotella has been reported to be associated with opportunistic infections, e.g., periodontitis or bacterial vaginosis (Larsen, 2017). Moreover, Prevotella is the major genus of one of the three reported human enterotypes (Arumugam et al., 2011), but how Prevotella behaves in different gut ecosystems and how it interacts with other bacteria of the microbiota and/or with its host is not well defined. In addition, high levels of genomic diversity within Prevotella strains of the same species have been observed (De Filippis et al., 2019, Gupta et al., 2015), which adds another layer of complexity for predicting the effects of Prevotella strains. Recent studies have linked higher intestinal abundance of Pc to rheumatoid arthritis (Alpizar-Rodriguez et al., 2019, Maeda et al., 2016, Scher et al., 2013), metabolic syndrome (Pedersen et al., 2016), low-grade systemic inflammation (Pedersen et al., 2016), and inflammation in the context of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (Dillon et al., 2016, Kaur et al., 2018, Lozupone et al., 2014), suggesting that some Prevotella strains may trigger and/or worsen inflammatory diseases (Larsen, 2017, Ley, 2016, Precup and Vodnar, 2019).

The microbiota plays a central role in protecting the host from pathogens, in part through colonization resistance (Buffie and Pamer, 2013). In the case of Listeria monocytogenes (Lm), the foodborne pathogen responsible for listeriosis, the intestinal microbiota provides protection, as germfree mice are more susceptible to infection than conventional mice (Archambaud et al., 2013, Becattini et al., 2017). Treatment with probiotics such as Lactobacillus paracasei CNCM I-3689 or L. casei BL23 was shown to decrease Lm systemic dissemination in orally inoculated mice (Archambaud et al., 2012). Unravelling the interactions between the host, the microbiota, and pathogenic bacteria is critical for the design of new therapeutic strategies via manipulation of the microbiota. However, identifying specific molecules and mechanisms used by commensals to elicit their beneficial action is challenging due to the high complexity of the microbiome, together with technical issues in culturing many commensal species. In addition, cooperative interactions between commensal species are likely to be central to the functioning of the gut microbiota (Rakoff-Nahoum et al., 2016). So far, mechanism or molecules underlying the impact of commensals on the host or on the infection have been elucidated only for a few species. For example, (i) segmented filamentous bacteria were shown to coordinate maturation of T cell responses toward Th17 cell induction (Gaboriau-Routhiau et al., 2009, Ivanov et al., 2009), (ii) glycosphingolipids produced by the common intestinal symbiont Bacteroides fragilis have been found to regulate homeostasis of host intestinal natural killer T cells (An et al., 2014), (iii) a polysaccharide A also produced by B. fragilis induces and expands Il-10 producing CD4+ T cells (Mazmanian et al., 2005, Mazmanian et al., 2008, Round and Mazmanian, 2010), (iv) the microbial anti-inflammatory molecule secreted by Faecalibacterium prausnitzii impairs the nuclear-factor-κB pathway (Quévrain et al., 2016), (v) Mucispirillum schaedleri protects mice from Salmonella-induced colitis (Herp et al., 2019), and (vi) Blautia producta restores resistance against vancomycin-resistant enterococci (Kim et al., 2019).

Conversely, enteric pathogens evolved various means to outcompete other species in the intestine and access nutritional and spatial niches, leading to successful infection and transmission. In this regard, the contribution of bacteriocins and type VI secretion system effectors during pathogen colonization of the gut is an emerging field of investigation (Bäumler and Sperandio, 2016, Rolhion and Chassaing, 2016). Here, we studied the impact of a previous unknown Lm bacteriocin (Lmo2776) on infection, and we discovered that Pc, an abundant gut commensal, is the primary target of Lmo2776 in both the mouse and human microbiota and as a modulator of infection.

Results

Lmo2776 Limits Lm Intestinal Colonization and Virulence in a Microbiota-Dependent Manner

A recent reannotation of the genome of the Lm strain EGD-e revealed that the lmo2776 gene, absent in the non-pathogenic L. innocua species (Figure S1A), potentially encodes a secreted bacteriocin of 107 amino acids (Desvaux et al., 2010, Glaser et al., 2001), homologous to the lactococcin 972 (Lcn972) secreted by Lactococcus lactis (Martínez et al., 1996) and to putative bacteriocins of pathogenic bacteria Streptococcus iniae (Li et al., 2014), Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus (Figure S1B). This gene belongs to a locus containing two other genes, lmo2774 and lmo2775, encoding potential immunity and transport systems (Glaser et al., 2001). It is present in lineage I strains responsible for the majority of Lm clinical cases (Maury et al., 2016) and in some lineage II strains, such as EGD-e (Figure S1C). Little is known about this bacteriocin family, and studies have focused on Lcn972. Lmo2776 shares between 38% an d 47% overall amino acid sequence similarity with members of the Lcn972 family. Because expression of lmo2774, lmo2775, and lmo2776 is significantly higher in stationary phase compared to exponential phase of EGD-e at 37°C in BHI (Figure S1D), all experiments described below were conducted with Lm grown up to stationary phase.

We first examined the effect of Lmo2776 on infection. We inoculated conventional BALB/c mice with either the WT, the Δlmo2776, or the Lmo2776 complemented strains and compared Lm loads in the intestinal lumen and deeper organs (spleen and liver). We had verified that deletion of lmo2776 was not affecting expression of surrounding genes, lmo2774, lmo2775, and lmo2777 (Figure S1E) or bacterial growth in vitro (Figure S1F). Inoculation of mice with Δlmo2776 strain resulted in significantly higher Lm loads in the small intestinal lumen 24 h post-inoculation (pi) compared to the WT strain (Figure 1A). These differences persisted at 48 and 72 h pi (Figure S1G). Lm loads of Δlmo2776 were also significantly higher in the spleen and liver at 72 h pi compared to both WT and Lmo2776-complemented strains (Figures 1B and 1C). Similar results were observed in C57BL/6J mice (data not shown). Together, these results indicate a key role for Lmo2776 in bacterial colonization of intestine and deeper organs. Following intravenous inoculation of BALB/c mice with WT or Δlmo2776 bacteria, bacterial loads at 72 h pi were similar in the spleen and liver (Figure S1H), revealing that Lmo2776 exerts its primary role during the intestinal phase of infection and not later.

Figure 1.

Lmo2776 Limits Lm Virulence in a Microbiota-Dependent Manner

(A–C) BALB/c mice were inoculated orally with Lm WT, Δlmo2776, or Lmo2776 complemented (p2776) bacteria. CFUs in the intestinal luminal content (A), spleen (B), and liver (C) were assessed at 72 h pi.

(D–F) Germfree C57BL/6J were inoculated with Lm WT or Δlmo2776 for 72 h and CFUs in the intestinal luminal content (D), spleen (E), and liver (F) were assessed. Each dot represents the value for one mouse. Statistically significant differences were evaluated by the Mann–Whitney test (∗p < 0.05; NS, not significant).

Considering that lmo2776 is predicted to encode a bacteriocin and that it significantly affects the intestinal phase of infection, we hypothesized that Lmo2776 might target intestinal bacteria, thereby impacting Lm infection. To address the role of intestinal microbiota in infection, we orally inoculated germfree mice with WT or Δlmo2776 strains and compared bacterial counts 72 h pi. Strikingly, no significant difference was observed between WT and Δlmo2776 strains in the small intestinal content (Figure 1D) nor in spleen and liver (Figures 1E and 1F). These results showed that the Lmo2776 bacteriocin limits the presence in the deeper organs of WT Lm in a microbiota-dependent manner.

Lmo2776 Targets Prevotella in Mouse and Human Microbiota

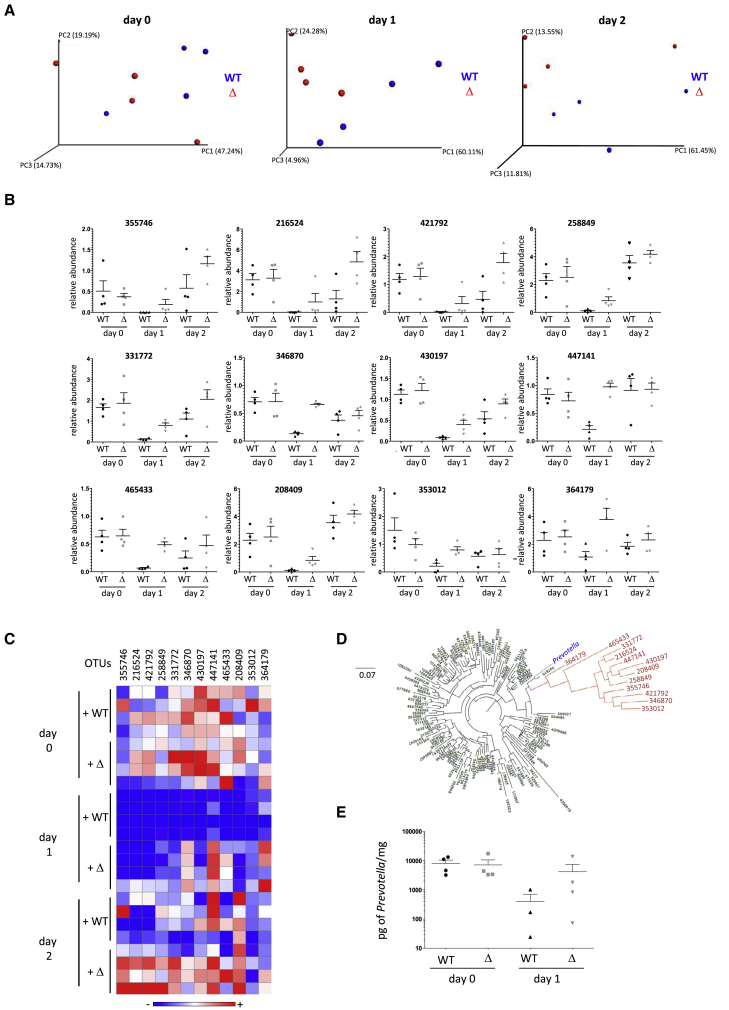

To identify which intestinal bacteria were targeted by Lmo2776, we compared microbiota compositions of conventional mice orally infected with WT or Δlmo2776 strains by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. We first verified that the fecal microbiota composition of all mice was indistinguishable at day 0 (Figure 2A). As expected, the microbiota composition at day 1 pi was dramatically altered by infection with Lm WT (Figure S2A). These alterations in microbiota composition included reduced levels of Bacteroidetes phylum (relative abundance before infection: 65.4% and at day 1 pi: 42.4%) and increased levels of Firmicutes (relative abundance before infection: 29.9% and at day 1 pi: 54.0%) (Figure S2B–S2E). The increased levels in the Firmicutes were mainly due to an increase of the Clostridia class (relative abundance before infection: 27.4% and at day 1 pi: 50.7%). Of note, the relative abundance of Lm was around 0.1% and cannot therefore explain by itself the increased levels of Firmicutes observed between day 0 and day 1. Importantly, at 24 h and 48 h pi, intestinal microbial compositions differed in mice orally inoculated with Δlmo2776 strain compared to WT strain (Figure 2A). We focused on operational taxonomic units (OTUs) for which the relative abundance was identical before infection with Lm strains (day −3 to day 0) and was subsequently altered by at least a 2-fold difference at day 1 pi in mice infected with Δlmo2776 compared to mice infected with WT strain. In independent experiments, the relative abundance of 12 OTUs was lower in mice infected with WT strain compared to Δlmo2776 mutant (Figures 2B and 2C) at day 1 and also at day 2 pi. Phylogenetic analyses revealed that all these 12 OTUs belong to the Prevotella cluster (Figure 2D). A decrease of Prevotella in mice infected with WT strain at day 1 and day 2 pi compared to mice infected with Δlmo2776 strain was also observed by qPCR analysis using primers specific for Prevotella (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Lmo2776 Targets Prevotella in Mouse Microbiota

(A) Principal coordinates analysis of the weighted Unifrac distance matrix of mice infected with WT strain or Δlmo2776 at days 0, 1, and 2. Permanova: day 0, p = 0.383; day 1, p = 0.05864; and day 2, p = 0.360.

(B) Relative abundance of 12 OTUs in gut microbiota of mice inoculated with WT or Δlmo2776 strains overtime. Each dot represents the value for one mouse.

(C) Heat-map analysis of the relative abundance of 12 OTUs in gut microbiota of mice inoculated with WT or Δlmo2776 strains. Each raw represents one mouse. The red and blue shades indicate high and low abundance.

(D) Phylogenetic tree of 16S rRNA gene alignment of 5 representative bacteria for each phylum of the bacteria domain, together with OTUs showing significantly different relative abundances in gut microbiota of mice infected with WT or Δlmo2776 strains at day 1 (in red).

(E) PCR quantification of Prevotella in feces of mice inoculated with WT strain or Δlmo2776 at day 0 and day 1.

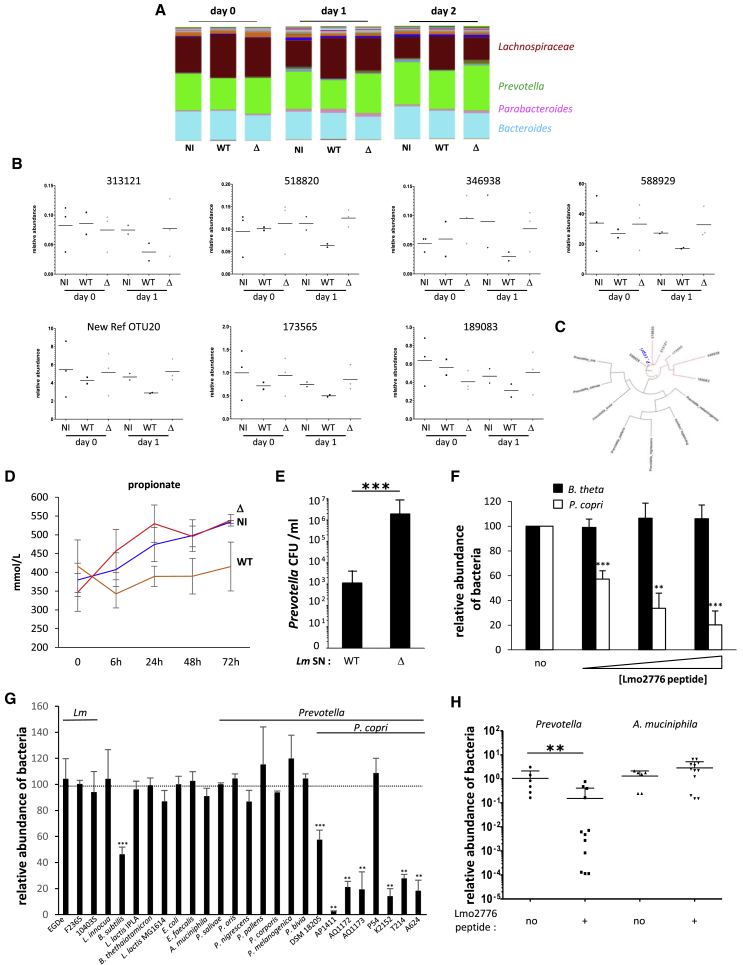

Important differences exist between mouse and human gut microbiota composition. Prevotella abundance is known to be low in mouse intestinal content (< 1%), although it can reach 80% in human gut microbiota (Hildebrand et al., 2013, Nguyen et al., 2015). As Lm is a human pathogen, we searched to investigate the impact of Lmo2776 on human gut microbiota. For this purpose, we used a dynamic in vitro gut model (mucosal-simulator of human intestinal microbial ecosystem [M-SHIME]), which allows stable maintenance of human microbiota in vitro in absence of host cells but in presence of mucin-covered beads (Chassaing et al., 2017, Geirnaert et al., 2015, Van den Abbeele et al., 2013, Van den Abbeele et al., 2012) and therefore allows studies on human microbiota independently of the host responses (such as inflammation). The microbiota of a healthy human volunteer was inoculated to the system which was then infected with WT or Δlmo2776 Lm. 16S sequencing to luminal and mucosal M-SHIME samples indicated that before Lm inoculation, the bacterial composition in all vessels was similar (Figure 3A and data not shown). In contrast, following Lm addition, luminal microbial community compositions were different in vessels containing WT Lm compared to both non-infected vessels and vessels infected with the Δlmo2776 isogenic mutant (Figure 3A). No difference was observed in mucosal microbial community composition. The relative abundance of 7 OTUs was lower in the case of the WT strain compared to the non-inoculated condition or upon addition of the Δlmo2776 strain (Figure 3B). These 7 OTUs all belonged to Pc species (Figure 3C), revealing that Lmo2776 targets Pc in human microbiota in a host-independent manner.

Figure 3.

Lmo2776 Targets Pc in Human Microbiota and In Vitro

(A) Relative abundance of genera in SHIME vessels non-infected or infected with WT or Δlmo2776 strains. The four more abundant genera are indicated.

(B) Relative abundance of 7 different OTUs in SHIME vessels infected with WT or Δlmo2776 strains or non-infected. Each dot represents the value for one vessel.

(C) Phylogenetic tree of 16S rRNA gene alignment of several Prevotella species, together with OTUs showing significantly different relative abundances in vessels inoculated with WT or Δlmo2776 strains at day 1 (in red).

(D) Levels of propionate in SHIME vessels infected with WT or Δlmo2776 strains or non-infected overtime. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM for 2 to 3 individual vessels.

(E) Numbers of Pc after incubation with supernatant of WT or Δlmo2776 strains.

(F) Relative abundance of Pc and Bt after 24 h incubation with increasing dose of Lmo2776 peptide (3 (+), 6 (++) and 9(+++) μg/mL) relative to their abundance without Lmo2776 peptide.

(G) Relative abundance of different bacteria after 24 h incubation with Lmo2776 peptide (3μg/mL) relative to their abundance without Lmo2776 peptide. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of a least 3 independent experiments and P values were obtained using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.005).

(H) PCR quantification of Prevotella and Am in the feces of mice treated with Lmo2776 peptide (1 mg) or with water relative to their levels before treatment. Each dot represents the value for one mouse. Statistically significant differences were evaluated by Student’s t test (∗∗p < 0.01).

As short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) levels serve as a classical readout for gut microbiota metabolism and as Prevotellae are known to produce propionate (Flint and Duncan, 2014), we quantified SCFAs production in the luminal M-SHIME samples. A specific decrease in propionate production upon infection with WT Lm was observed as early as 6 h pi (Figure 3D) compared to non-infected and Δlmo2776-infected vessels. This difference was continuously observed up to 3 days pi, while no significant difference was observed for butyrate, isobutyrate, acetate and isovalerate (Figure S3). Although propionate is produced by many bacterial species, the decrease in propionate production observed upon inoculation of M-SHIME with WT Lm is in agreement with the decrease in Pc population.

Lmo2776 Targets Pc In Vitro

We first addressed the direct inhibitory activity of Lmo2776 on Pc by growing Pc (DSMZ 18205 strain) at 37°C in anaerobic conditions in the presence of culture supernatants of Lm strains and counting the viable CFUs on agar plates. Growth of Pc dramatically decreased in the presence of the WT Lm supernatant compared to the Δlmo2776 supernatant or medium alone (Figure 3E), suggesting that Lmo2776 is secreted and targets directly Pc.

To definitively assess the function of Lmo2776, a peptide of 63 aa (Gly69 to Lys131) corresponding to the putative mature form of Lmo2776 was synthesized. Its activity was first analyzed on Pc and B. thetaiotaomicron (Bt), another prominent commensal bacterium (Figure 3F). A dose-dependent effect of Lmo2776 peptide was observed on Pc growth, while no effect was observed on Bt growth, demonstrating that Lmo2776 targets Pc and not Bt. We then tested the effect of the peptide on several other intestinal bacteria, either aerobic (Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli) or anaerobic (Akkermansia muciniphila [Am]) bacteria. No effect was observed on any of these bacteria (Figure 3G). Moreover, Lmo2776 peptide did not inhibit growth of seven other Prevotella species (Ps, P. oris, P. nigrescens, P. pallens, P. corporis, P. melaninogenica, and P. bivia). We next tested the peptide activity on 7 Pc isolated from healthy humans and patients. Strikingly, 6 out of the 7 strains were sensitive to the bacteriocin (Figure 3G).

We also tested the effect of the Lmo2776 peptide on known targets of the bacteriocins of the Lcn972 family (Bacillus subtilis [Bs] and L. lactis MG1614). Growth of Bs decreased significantly in presence of the peptide (Figure 3G), while no effect was observed on L. lactis growth. Growth of Bs was also significantly reduced in the presence of WT Lm and of Lmo2776 complemented strains compared to the Δlmo2776 strain (Figures S3E and S3F). Addition of the culture supernatant of WT Lm to Bs significantly decreased the number of Bs compared to the addition of Δlmo2776 culture supernatant (Figure S3G) (Li et al., 2014). Together, these results indicate that Lmo2776 is a bona fide bacteriocin that targets both Pc and Bs in vitro.

To evaluate the effect of Lmo2776 peptide in vivo, we used an approach previously described to bypass degradation by enzymes of the upper digestive tract. Conventional BALB/c mice were inoculated intra-rectally with Lmo2776 peptide (1mg per mice, a dose probably higher than the one produced by Lm upon infection) or water, taken as a control. Levels of total bacteria, Prevotella and Am were determined by qPCR on feces collected between 1 and 4 h pi. While no effect was observed on the levels of total bacteria or Am, fecal levels of Prevotella decreased following administration of Lmo2776 peptide, showing that similar to bacteria, Lmo2776 alone was effective in reducing Pc in vivo (Figure 3H).

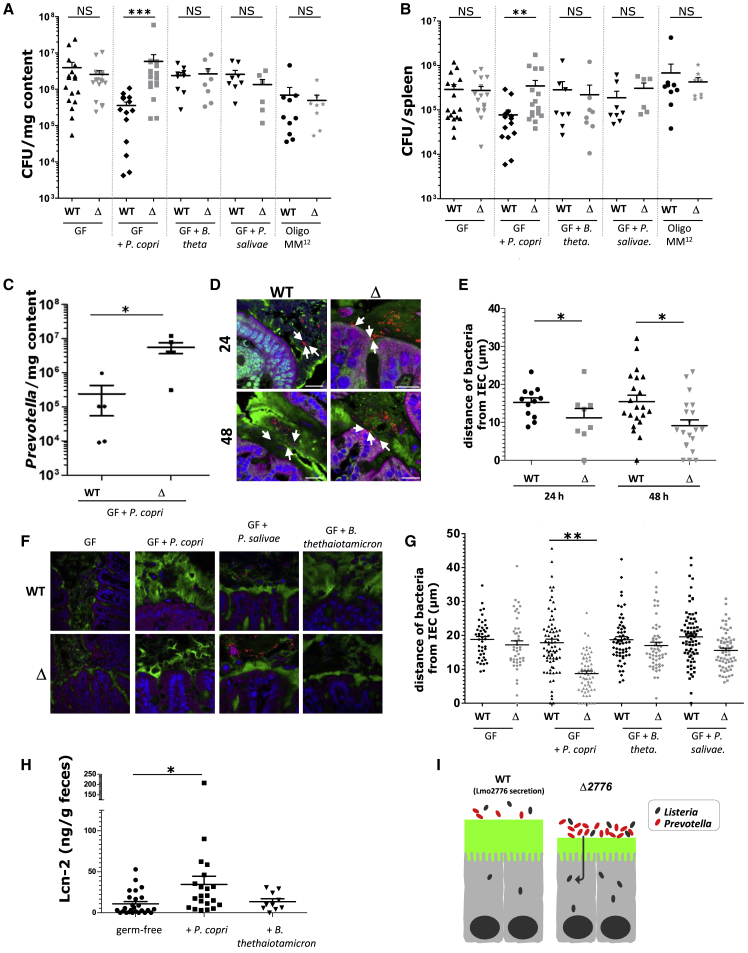

Colonization of Germfree Mice by Pc Phenocopies the Effect of the Microbiota on Lm Intestinal Growth in Conventional Mice

To decipher the role of Pc during Lm infection in vivo, germfree C57BL/6J mice were orally inoculated with either Pc (DSMZ 18205 strain), Bt or Ps, another Prevotella present in the gut, or stably colonized with a consortium of 12 bacterial species (termed Oligo-Mouse-Microbiota (Oligo-MM12), representing members of the major bacterial phyla in murine gut (Brugiroux et al., 2016)). Two weeks after colonization, mice were orally inoculated with WT Lm or Δlmo2776 strains and Lm loads in the intestinal lumen and target organs were compared 72 h pi. Compared to WT strain, Δlmo2776 mutant strain displayed significantly higher loads in the intestinal lumen (Figure 4A), spleen (Figure 4B) and liver (Figure S4) in mice colonized with Pc, while no difference between the two strains was observed in mice precolonized with Bt, Ps or the OligoMM12 consortium. In addition, the number of Pc significantly decreased in WT inoculated Pc-colonized animals compared to Δlmo2776-inoculated animals (Figure 4C). Altogether, these results indicate that the greater ability of the Δlmo2776 mutant to grow in intestine and reach deeper tissues compared to the WT strain correlates with the presence of Prevotella in the microbiota, as it is observed in either conventional mice or mice colonized with Pc. We cannot exclude that the production of the bacteriocin against Prevotella in vivo and at 3 days pi has a fitness cost for Lm strains.

Figure 4.

Pc Controls Lm Infection by Modifying Mucus Layer and Promoting Inflammation

(A and B) Assessment of listerial CFUs in the intestinal luminal content (A) and in the spleen (B) of germfree (GF) C57BL/6J mice colonized or not with Pc, Ps or Bt or stably colonized with 12 bacterial species (Oligo-MM12) for 2 weeks and then inoculated with Lm WT or Δlmo2776 for 72 h.

(C) Numbers of Pc CFUs in the intestinal luminal content of GF C57BL/6J mice colonized with Pc and then inoculated with Lm WT or Δlmo2776 for 72 h.

(D) Confocal microscopy analysis of microbiota localization in colon of BALB/c mice infected with Lm WT or Δlmo2776 bacteria for 24 or 48 h. Muc2 (green), actin (purple), bacteria (red), and DNA (blue). Bar = 20 μm. White arrows highlight the 3 closest bacteria. Pictures are representatives of 5 biological replicates.

(E) Distances of closest bacteria to colonic intestinal epithelial cells per condition over 5 high-powered fields per mouse, with each dot representing a measurement.

(F) Confocal microscopy analysis of microbiota localization in colon of GF C57BL/6J mice colonized with Pc, Bt or Ps for 2 weeks and inoculated with Lm WT or Δlmo2776 bacteria. Muc2 (green), actin (purple), bacteria (red), and DNA (blue). Bar: 20 μm.

(G) Distances of closest bacteria to intestinal cells per condition over 5 high-powered fields per mouse, with each dot representing a measurement.

(H) Levels of the inflammatory marker Lcn-2 in feces of mice 2 weeks pi with Pc or Bt.

(I) Model depicting the effect of Prevotella on Lm infection. In (A), (B), and (E), each dot represents one mouse. Statistically significant differences were evaluated by the Mann–Whitney test (A, B), one way-ANOVA test (E, G) or two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test (C, H) (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.005).

Pc Modifies the Mucus Layer

The intestinal mucus layer forms a physical barrier of about 30μm that is able to keep bacteria at a distance from the epithelium (Johansson et al., 2008). A mucus-eroding microbiota promotes greater epithelial access (Desai et al., 2016). Prevotella, through production of sulfatases that induce mucus degradation (Wright et al., 2000), might impair the mucosal barrier function and therefore contribute to better accessibility to intestinal epithelial cells and to local inflammation. We thus compared the colonic mucus layer thickness of conventional mice infected with WT Lm or Δlmo2776 by confocal microscopy, using mucus-preserving Carnoy fixation and FISH (Johansson and Hansson, 2012). The average distance of bacteria from colonic epithelial cells was significantly smaller in mice infected with Δlmo2776 compared to mice infected with WT Lm at 24 and 48 h (Figures 4D and 4E), suggesting that Prevotella present in the microbiota of mice infected with Δlmo2776 decreases the mucus layer thickness and might consequently increase its permeability. Of note, these distances were also smaller than in uninfected mice, indicating that Lm infection itself affects the mucus layer thickness. To confirm the effect of Pc on mucus layer in the context of listerial infection, germfree C57BL/6J mice were precolonized with Pc (DSMZ 18205 strain), Bt, or Ps, then orally inoculated with WT Lm or Δlmo2776 strains; and mucus layer thickness was analyzed by FISH. In mice precolonized with Pc, the average distance of bacteria from colonic epithelial cells was significantly smaller in Δlmo2776-infected mice compared to WT Lm-infected mice (Figures 4F and 4G). Strikingly, such a difference was not observed in germfree mice or in mice precolonized with Ps or Bt, revealing that mucus erosion is dependent on Pc.

Since the thinner mucus layer induced by Prevotella could favor invasion of the host by bacteria and contribute to intestinal inflammation, we quantified faecal lipocalin-2 (LCN-2) as a marker of intestinal inflammation (Chassaing et al., 2012). LCN-2 is a small secreted innate immune protein that is critical for iron homeostasis and whose levels increase during inflammation. Faecal LCN-2 levels were analyzed after colonization of germfree mice with Pc compared to non-colonized mice or mice colonized with Bt. A significant increase of faecal LCN-2 was observed in germfree mice monocolonized with Pc compared to non-colonized animals or to animals monocolonized with Bt (Figure 4H), revealing that Pc induces intestinal inflammation. Altogether, these results showed that presence of Prevotella in the intestine is associated with a thinner mucus layer and increased levels of faecal LCN-2. They are consistent with previous reports describing Prevotella as a bacterium promoting a pro-inflammatory phenotype (Elinav et al., 2011, Larsen, 2017, Scher et al., 2013).

Discussion

Outcompeting intestinal microbiota stands among the challenging issues for enteropathogens. Pathogens may secrete diffusible molecules such as bacteriocins or T6SS effectors to target commensals and consequently promote colonization and virulence. In most cases, molecular mechanisms underlying the interplay between pathogenic and commensal bacteria in the intestine remain elusive. We previously reported that most strains responsible for human infections, such as the F2365 strain, secrete a bacteriocin that promotes intestinal colonization by Lm (Quereda et al., 2016). When overexpressed in mouse gut, this bacteriocin, named Listeriolysin S (LLS), decreases Allobaculum and Alloprevotella genera known to produce butyrate or acetate, two SCFAs reported to inhibit transcription of virulence factors or growth of Lm (Ostling and Lindgren, 1993, Sun et al., 2012). However, whether physiological concentrations of LLS have a direct or an indirect role on these genera is still under investigation and is a question particularly difficult to address as LLS is highly post-translationally modified and therefore difficult to purify or to synthetize. In the case of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infection, killing of intestinal Klebsiella oxytoca via its T6SS is essential for S. enterica gut colonization of gnotobiotic mice colonized by K. oxytoca (Sana et al., 2016), but whether K. oxytoca and other members of the gut microbiota are targeted by the Salmonella T6SS in conventional mice is unknown. Shigella sonnei uses a T6SS to outcompete E. coli in vivo but the effectors responsible for this effect are unknown (Anderson et al., 2017).

Here, we report and provide evidence that the Lmo2776 Lm bacteriocin targets Prevotella in mouse and in in vitro reconstituted human microbiota. This effect is direct and specific to Pc, as (i) Pc are killed by Lm culture supernatant and by the purified Lmo2776 in vitro and (ii) despite the complexity of the microbiota and its well-controlled equilibrium, no other genus of the intestinal microbiota was found to be impacted by Lmo2776. By studying Lmo2776, we have unveiled a so-far-unknown role for intestinal Pc in exacerbating bacterial infection. The intestinal microbiota, in some cases, has already been reported to promote bacterial virulence by producing metabolites that enhance pathogens virulence gene expression and colonization in the gut (Bäumler and Sperandio, 2016, Rolhion and Chassaing, 2016). For example, Bt enhances Clostridium rodentium colonization by producing succinate (Curtis et al., 2014, Ferreyra et al., 2014), and Am exacerbates S. Typhimurium-induced intestinal inflammation by disturbing host mucus homeostasis (Ganesh et al., 2013). Pc decreases the mucus layer thickness and increases propionate concentration and levels of fecal LCN-2, in agreement with previous studies reporting that Pc exacerbates inflammation (Elinav et al., 2011, Scher et al., 2013). In addition, Prevotella enrichment within the lung microbiome of HIV-infected patients has been observed and is associated with Th17 inflammation (Shenoy and Lynch, 2018). Prevotella sp. have also been associated with bacterial vaginosis, and their role in its pathogenesis has been linked to the production of sialidase, an enzyme involved in mucin degradation and increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Briselden et al., 1992, Si et al., 2017). Together, our data strongly suggest that Pc, by modifying mucus layer permeability and changing the gut inflammatory condition, promotes greater epithelial access and therefore infection by Lm (Figure 4I). We can speculate that individuals with a high abundance of intestinal Prevotella might be more susceptible to enteric infections. Interestingly, it was recently shown that subjects with higher relative abundance of Pc could be at higher risk to traveler’s diarrhea and to the carriage of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (Leo et al., 2019). In addition, as Lmo2776 bacteriocin allows a selective depletion of Pc in the gut, it could prevent excessive inflammation and allow Lm persistence and long-lasting infection, eventually leading to meningitis. Further work is required to determine why Lm strains have kept the lmo2776 gene. We showed here that the Lmo2776 bacteriocin also targets Bs, a Gram-positive bacterium found in the soil, suggesting that Lmo2776 could give an advantage to Lm in that environment. It is possible that Lmo2776 is critical for species survival and replication in a so far unknown niche, consequently favoring transmission or dissemination. Bs is also found in the human gastrointestinal tract (Hong et al., 2009) and could be targeted by Lmo2776 in the intestine as well. Bs is also targeted by Sil, another member of the Lcn972 family (Li et al., 2014). The role of the homologs of Lcn972 in other human pathogenic bacteria such as S. pneumoniae and S. aureus remains to be determined, but conservation of the bacteriocin in different pathogenic bacteria associated with mucosa strongly suggests an important role.

Taken together, our data reveal that Pc can modulate intestinal infection, and using Lmo2776 might represent an effective therapeutic tool for Prevotella-related diseases to reduce Pc abundance in the gut without affecting the remaining commensal microbiota.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mucin-2 primary antibody | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | rabbit H-300 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| EGD-e Listeria monocytogenes WT strain | Mackanes, 1964 | BUG 1600 |

| EGD-e Δlmo2776 Listeria monocytogenes EGD-e lmo2776 deletion mutant |

this study | BUG 3713 |

| EGD-e Δlmo2776 plmo2776 pAD-lmo2776 chromosomally integrated in Δlmo2776 | this study | BUG 3717 |

| F2365, Listeria monocytogenes strain associated with the 1985 listeriosis outbreak in California | Linnan et al., 1988 | BUG 3012 |

| 10403S, Listeria monocytogenes WT strain | Edman et al., 1968 | BUG 1361 |

| L. innocua Clip11262 | ATCC | ATCC 33091 |

| Bacillus subtilis 168trpC2 | Institut Pasteur Collection | BUG 748 |

| Escherichia coli Top10 | Invitrogen | C404003 |

| Bacteroides thethaiotamicron | Institut Pasteur Collection | CIP 104206T |

| Lactococcus lactis IL14103 | Gift from B. Martinez | BUG 1801 |

| Lactococcus lactis M1363 | Gift from B. Martinez | BUG 3029 |

| Enterococcus faecalis | ATCC | ATCC 700802 |

| Akkermensia muciniphila | ATCC | ATCC BA-835 |

| Prevotella copri | DSMZ | DSMZ 18205 |

| Prevotella salivae | DSMZ | DSMZ 15606 |

| Prevotella oris | Institut Pasteur Collection | CIP 104480T |

| Prevotella nigrescens | Institut Pasteur Collection | CIP 105552T |

| Prevotella pallens | Institut Pasteur Collection | CIP 105551T |

| Prevotella corporis | Institut Pasteur Collection | CIP 105107T |

| Prevotella melanogenica | Institut Pasteur Collection | CIP 104591 |

| Prevotella bivia | Institut Pasteur Collection | CIP 105105T |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| GTFWVTWGQDRHYSNYQHTKKTHRSSASNYRATERSSW KAKNNLATAWIKSSLWGNKANWATK |

Chemically synthetized polypeptide for this study | N/A |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| PowerSoilTM DNA Isolation Kit | MOBiO | 12888-50 |

| Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA assay | ThermoFischer | P7589 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| 16S rRNA gene sequence data | this study | in the European Nucleotide Archive database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena) |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| BALB/c mice | Charles River | 24980676 |

| C57BL6/J mice | Charles River | 24980803 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| All oligonucleotides are listed in Table S1. | This study | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pMAD(shuttle vector used for creating plasmid for mutagenesis) | Arnaud et al., 2004 | N/A |

| pAD (site-specific integration vector used for complementation) | Lauer et al., 2002 | N/A |

| plmo2776 lmo2776 complementation plasmid | this study | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 6.0 | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| Microsoft Excel | Microsoft | https://products.office.com/en-us/excel |

Lead Contact and Materials Availability

Further information and requests for resources and reagents, including strains and plasmids generated in this study, should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Pascale Cossart (pascale.cossart@pasteur.fr). All reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact.

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Bacterial Strains and Plasmids

Strains, plasmids and primers used in this study are listed in in the Key Resources Table. For standard experiments, Listeria, E. coli, Bs and L. lactis were grown at 37°C with shaking in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) medium (Difco) and Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (BD). If needed, Lm were selected on Oxford medium (Oxoid). Anaerobic bacteria were grown in appropriate medium (PYG medium modified or Schaedler medium or BHI supplemented with 8mM L-Cysteine hydrochloride, 0.2% NaHCO3 and 0.025% Hemin, following ATCC or DSMZ recommendations) at 37°C under anaerobic conditions (Genbag Anaer, Biomérieux or AnaeroGen, ThermoScientific). The Lmo2776 deletion mutant was constructed using the pMAD shuttle plasmid (Arnaud et al., 2004) as described previously (Mellin et al., 2013) and confirmed by DNA sequencing. For the construction of pAD-based plasmid, fragment obtained by PCR with EGD-e genomic DNA as template, was cloned into the SmaI/SalI sites of the pAD vector (Balestrino et al., 2010) derived previously from the pPL2 vector (Lauer et al., 2002). Plasmid was verified by sequencing with primers pPL2-Rv and pPL2-Fw and were transformed into Δlmo2776 by electroporation. Integration in the chromosome was verified by PCR using primers NC16 and PL95 (Balestrino et al., 2010). Pc strains (AP1411, AQ1172, AQ1173, P54, K2152, T214 and A624) were isolated from stool from healthy subjects and new onset rheumatoid arthritis patients. Stool was collected into anaerobic transport media (Anaerobe Systems), then streaked on BRU and LKV plates (Anaerobe Systems). After 24-48 h, individual colonies were picked and screened with Prevotella-specific PCR primers, and the 16S rRNA V3-V4 sequence was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Fehlner-Peach et al., manuscript in preparation). Prevotella-positive isolates were grown on BRU plates, and glycerol stocks were frozen at −80°C.

Mice

9- to 12-week-old female BALB/c conventional (Charles River) or C57BL6/J conventional (Charles River) or C57BL6/J germfree (CDTA or Pasteur) or C57BL6/J stably colonized with a consortium of 12 bacterial species (termed Oligo-Mouse-Microbiota (Oligo-MM12), representing members of the major bacterial phyla in the murine gut: Bacteroidetes (Bacteroides caecimuris and Muribaculum intestinale), Proteobacteria (Turicimonas muris), Verrucomicrobia (Am), Actinobacteria (Bifidobacterium longum subsp. Animalis) and Firmicutes (Enterococcus faecalis, Lactobacillus reuteri, Blautia coccoides, Flavonifractor plautii, Clostridium clostridioforme, Acutalibacter muris and Clostridium innocuum) (Brugiroux et al., 2016)) mice were used for experiments. Germfree and Oligo-MM12 mice were housed in plastic gnotobiotic isolators.

All animal experiments were carried out in strict accordance with the French national and European laws and conformed to the Council Directive on the approximation of laws, regulations, and administrative provisions of the Member States regarding the protection of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes (86/609/Eec). Experiments that relied on laboratory animals were performed in strict accordance with the Institut Pasteur’s regulations for animal care and use protocol, which was approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of the Institut Pasteur (approval no. 03-49).

Method Details

Mice Infection

Lm overnight cultures were diluted in BHI and bacteria were grown to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1. Bacterial cultures were centrifuged at 3,500 × g for 15 min and washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Mice were infected orally with 5 × 109 bacteria diluted in 200 μl of PBS supplemented with 300 μl of CaCO3 (50 mg/mL). Serial dilutions of the inoculum were plated to control the number of bacteria inoculated. The different inoculum were closed to 5 × 109 bacteria and the mean ± SEM of all independent experiments were: for WT: 5.03 × 109 ± 0.26 × 109, for Δlmo2776: 5.01 × 109 ± 0.14 × 109 (p = 0.45) or Lmo2776 complemented strain: 4.87 × 109 ± 0.30 × 109 (p = 0.25). Mice were killed at subsequent time points, and intestines, spleens, and livers were removed. The small intestine was opened, and the luminal content was recovered in a 1.5-mL tube and weighed. The small intestine (duodenum, jejunum, and ileum) tissue was washed four times in DMEM (ThermoFisher), incubated for 2 h in DMEM supplemented with 40 μg/mL gentamycin, and finally washed four times in DMEM. All of the organs and the intestinal luminal content were homogenized, serially diluted, and plated onto BHI plates or Oxford plates and grown overnight at 37°C for 48–72 h. CFU were enumerated to assess bacterial load. At least three independent experiments were carried out with four or five mice per group in each experiment. Statistically significant differences were evaluated by the Mann–Whitney test, and differences were considered statistically significant when P values were < 0.05.

For mice colonization, Pc, Ps and Bt were grown to log phase under anaerobic conditions in PYG modified or Schaedler broth media and 107 CFU were used to inoculate germ-free mice. Feces were collected at 2 weeks post-gavage to confirm colonization. Feces were homogenized, serially diluted and plated on PYG modified, Schaedler or Columbia agar plates.

Six- to 8-week-old female BALB/c mice (Charles River, Inc., France) were injected intravenously with 5.103 CFU of the indicated strain. Mice were sacrificed at 72 h after infection, and livers and spleens were removed. Organs were homogenized and serially diluted. Dilutions were plated onto BHI plates and grown during 24 h at 37°C. Colonies were counted to assess bacterial load per organ.

Fecal Microbiota Analysis by 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing Using Illumina Technology

Before infection, 8 BALB/c conventional mice were co-housed for 5 weeks in order to stabilize and homogenize their microbiota. After oral infection, animals were single-housed. Feces were collected and frozen at −20°C. 16S rRNA gene amplification and sequencing were done using the Illumina MiSeq technology following the protocol of Earth Microbiome Project with their modifications to the MOBIO PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit procedure for extracting DNA (Caporaso et al., 2012, Gilbert et al., 2010). Bulk DNA were extracted from frozen extruded feces using a PowerSoil DNA Isolation kit (MoBio Laboratories) with mechanical disruption (bead-beating). The 16S rRNA genes, region V4, were PCR amplified from each sample as described in Chassaing et al., 2015 (Chassaing et al., 2015). Four independent PCRs were performed for each sample, combined, purified with Ampure magnetic purification beads (Agencourt), and products were visualized by gel electrophoresis. Products were then quantified (BIOTEK Fluorescence Spectrophotometer) using Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA assay. A master DNA pool was generated from the purified products in equimolar ratios. The pooled products were quantified using Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA assay and then sequenced using an Illumina MiSeq sequencer (paired-end reads, 2 × 250 bp) at Cornell University (Ithaca, USA).

Bacterial Quantification in Feces

Bulk DNA were extracted from frozen extruded feces using a PowerSoil DNA Isolation kit (MoBio Laboratories) with mechanical disruption (bead-beating). q-PCR reactions were prepared with SYBR Green master mix. Reaction cycling and quantification was carried out in an C1000 touch Thermal cycler (CFX384, Biorad). Genomic DNA from Prevotella was used to generate a standard curve to quantitate pg of Prevotella present per mg of total feces.

M-SHIME

M-SHIME system is a dynamic in vitro model which simulates the lumen-associated and mucus-associated human intestinal microbial ecosystem (ProDigest, Ghent University, Belgium) (Geirnaert et al., 2015, Van den Abbeele et al., 2013, Van den Abbeele et al., 2012). It consists of consecutive pH-controlled, stirred, airtight, double-jacketed glass vessels kept at 37°C and under anaerobic conditions. The system was operated as described earlier (Chassaing et al., 2017) with minor modifications The set-up used here consisted of 3 stomach-small intestine vessels and 9 proximal colon vessels in parallel (3 for non-infected condition, 3 for infection with WT and 3 for infection with Δlmo2776). The colon vessels were inoculated at the start with 40 mL fresh human faecal suspension, from a healthy volunteer with high levels of Prevotella, in 500 mL sterile nutritional medium. Every 2 days, half of the mucin agar-covered microcosms were replaced by fresh sterile ones under a flow of N2 to prevent disruption of anaerobic conditions. Fourteen days after inoculation, 3 colon vessels were infected with 106 WT bacteria, 3 colon vessels with 106 Δlmo2776 and 3 were left uninfected. Lumen (10 ml) and mucin agar samples were taken at 6, 24, 48 and 72 h. Mucin agar-covered microcosms were washed with sterile PBS to remove lumen bacteria. Mucin agar was removed from microcosms, homogenized and stored immediately at −20°C until further analysis.

For 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing, DNA was extracted from 1 mL of lumen samples or 250 mg of mucin agar samples using a PowerSoil DNA Isolation kit and 16S rRNA gene sequencing was analyzed as decribed above.

Our full 16S rRNA gene sequence data are deposited under Study ID PRJEB34638 in the European Nucleotide Archive database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena).

For SCFA analysis, lumen samples were diluted 1:2 in demineralized water. Acetate, propionate, butyrate, isobutyrate and isovalerate were extracted and quantified as described (De Weirdt et al., 2010).

RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

A total of 25 mL cultures of bacteria, grown in BHI, was pelleted for 20 min at 3000 g. Pellets were resuspended in 1 mL TRI Reagent (Sigma), transferred to 2 mL Lysing Matrix tubes (MP Biomedicals) and mechanically lysed by bead beating in a FastPrep apparatus (twice 45 s, speed 6.5). Tubes were then centrifuged for 5 min at 8000 g at 4°C to separate beads from lysates. The lysates were drawn off and transferred to a 2 mL Eppendorf tube. 200 uL chloroform was added to the lysate, shaken and incubated 10 min at room temperature, followed by centrifugation for 15 min at 13 000 g at 4°C. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube and RNA was precipitated by the addition of 500 uL isopropanol and incubation at room temperature for 10 min. RNA was pelleted by centrifuging for 10 min at 13000 g at 4°C, washed twice with 75% ethanol. RNA pellets were resuspended in 50 to 100 uL water. For each sample, 10 ug of RNA was treated with Dnase (Turbo DNA-free, Ambion) following manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthetiszed from 1 ug of RNA using QuantiTect Reverse Transcription (QIAGEN) and reactions were subsenquently diluted with 180 ul of water. qRT-PCR reactions were prepared with SYBR Green master mix. Reaction cycling and quantification was carried out in an C1000 touch Thermal cycler (CFX384, Biorad). Expression levels were normalized to the rpoB gene. Samples were evaluated in triplicate and results represent at least three independent experiments.

Co-cultures and Culture in Presence of Supernatant or Lmo2776 Peptide

For co-culture assays with Bs, a mixture of equivalent CFU (107) of Bs and Lm (WT, Δlmo2776 or p2776) was inoculated into 5 mL of fresh BHI and incubated at 37°C for 6 h. Serial dilutions were plated on BHI and on Oxford media for CFU enumeration.

For culture of target in presence of Listeria supernatant, 25 mL of overnight culture of Listeria were centrifuged at 13000 g and the supernatants were collected and centrifuged further to remove cells and cells debris. Supernatants were filtered through a 0.20μm pore size filter (Millipore). 107 bacterial targets (Bs, E. coli or Pc) were inoculated at 37°C into 2.5 mL of listerial supernatant and 2.5 mL of fresh medium (BHI for Bs, LB for E. coli and PYG modified for Pc). At 16 h after inoculation (in aerobic conditions for Bs and E. coli and in anaerobic conditions for Pc), cultures were serially diluted and plated on medium.

For in vitro assays, a peptide of 63aa (GTFWVTWGQDRHYSNYQHTKKTHRSSASNYRATERSSWKAKNNLATAWIKSSLWGNKANWATK), corresponding to the putative mature form of Lmo2776 has been chemically synthesized (Polypeptide) and diluted. 107 bacteria were inoculated in absence or in presence of different concentrations of this peptide at 37°C into 5 mL of medium. At 16 h after inoculation (in aerobic or anaerobic conditions), cultures were serially diluted and plated.

For in vivo assays, conventional mice were anaesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of 75 mg ketamine kg−1 and 5 mg xylazine kg−1. One hundred ul of Lmo2776 peptide (1mg in 100μl distilled H2O) was introduced rectally using a flexible catheter into each of 12 test mice and 100μl distilled H2O was introduced into each of 6 control mice. Feces were collected between 1 and 4 h following the introduction. Bacteria were quantified as described above.

Immunostaining of Mucins and Localization of Bacteria by FISH

Colonic mucus immunostaining was paired with fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), as previously described (Chassaing et al., 2017, Johansson and Hansson, 2012). Briefly, colonic tissues (proximal colon, 2nd cm from the cecum) containing fecal material were placed in methanol-Carnoy’s fixative solution (60% methanol, 30% chloroform, 10% glacial acetic acid) for a minimum of 3 h at room temperature. Tissues were then washed in methanol 2 × 30 min, ethanol 2 × 15 min, ethanol/xylene (1:1) 15 min and xylene 2 × 15 min, followed by embedding in Paraffin with a vertical orientation. Five μm sections were performed and dewax by preheating at 60°C for 10 min, followed by xylene 60°C for 10 min, xylene for 10 min and 99.5% ethanol for 10 min. Hybridization step was performed at 50°C overnight with EUB338 probe (5′-GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT-3′, with a 5′ labeling using Alexa 647) diluted to a final concentration of 10 μg/mL in hybridization buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 0.9 M NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 20% formamide). After washing 10 min in wash buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 0.9 M NaCl) and 3 × 10 min in PBS, PAP pen (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to mark around the section and block solution (5% fetal bovine serum in PBS) was added for 30 min at 4°C. Mucin-2 primary antibody (rabbit H-300, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) was diluted 1:1500 in block solution and apply overnight at 4°C. After washing 3 × 10 min in PBS, block solution containing anti-rabbit Alexa 488 secondary antibody diluted 1:1500, Phalloidin-Tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate (Sigma-Aldrich) at 1 μg/mL and Hoechst 33258 (Sigma-Aldrich) at 10 μg/mL was applied to the section for 2 h. After washing 3 × 10 min in PBS slides were mounted using Prolong anti-fade mounting media (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Observations were performed with a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope. The software Zen 2011 version 7.1 was used to measure the distance between bacteria and epithelial cell monolayer.

Quantification of Fecal Lcn-2 by ELISA

Fecal samples were weighted, reconstituted in PBS-0.1% Tween 20 to a final concentration of 100 mg/mL and homogenized. Samples were then centrifuged for 10 min at 14 000 g and 4°C and supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C until analysis. Lcn-2 levels were measured using DuoSet mouse Lipocalin-2/NGAL ELISA kit (R&D Systems).

Core genome MLST

lmo2774, lmo2775, lmo2776 genes were screened in a collection of 1,696 publicly available genomes (Moura et al., 2016)representative of the diversity of lineages and sublineages of Lm. Genes were detected using the BLASTn algorithm implemented in BIGSdb-Lm platform v.1.17 (https://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/listeria; (Jolley and Maiden, 2010, Moura et al., 2016), with minimum nucleotide identity of 70%, alignment length coverage of 70% and word size of 10.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Statistical Analysis

Statistically significant differences were evaluated by Mann–Whitney test, one way-ANOVA test or two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test using Excel or Prism software. Statistical details of experiments and statistical tests are reported and described in the figure legends. Differences denoted in the text as significant fall below a p value of 0.05.

Data and Code Availability

16S rRNA Gene Sequence Analysis

Analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequence was performed exactly as previously described (Chassaing et al., 2015). Our full 16S rRNA gene sequence data are deposited under Study ID PRJEB34638 in the European Nucleotide Archive database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena).

Acknowledgments

We thank the CDTA (Orléans) and the Institut Pasteur Animalerie Centrale staff, especially K. Sébastien, T. Angélique, M.G. Lopez Dieguez, M. Jacob, and E. Maranghi. We thank G. Jouvion and M. Tichit for technical help and the Centre Ressources Biologiques de l’Institut Pasteur for providing strains. We thank L. Maranghi, J. Blondou, and A. Lavelle for technical support and C. Bécavin, A. Hryckowian, B. Martinez, G. Eberl, G. Hansson, and H. Sokol for helpful discussion. N.R. was supported by an EMBO short-term fellowship (ASTF 399-2015); B.C. by a Career Development Award from the CCFA, an Innovator Award from the Kenneth Rainin Foundation, and a Seed Grant from the GSU’s Brain & Behavior program; H.F.-P. by an NYU-HCC CTSI grant (1TL1TR001447); and D.R.L. by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Colton Center for Autoimmunity. This work was supported by grants to P.C.: ERC Advanced Grant BacCellEpi (670823), ANR (Investissement d’Avenir Programme 10-LABX-62-IBEID), ERANET Infect-ERA PROANTILIS (13-IFEC-0004-02), and the Fondation le Roch.

Authors Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C. and N.R.; Investigation, N.R., B.C. (16S samples preparation and sequencing data analysis, and FISH), M.-A.N. (in vivo work), J.d.B. (M-SHIME), A.M., and M.L. (genomic analyses); Methodology, N.R., O.D., and M.B.; Writing – Original Draft, N.R. and P.C.; Writing – Review & Editing, B.C., O.D., A.M., M.L., H.F.-P., D.R.L., M.M., A.T.G., and T.V.d.W.; Advices: O.D., A.T.G., T.V.W., and M.M.; Resources, M.B., H.F.-P., and D.R.L.; Supervision, P.C.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: November 13, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2019.10.016.

Supplemental Information

References

- Alpizar-Rodriguez D., Lesker T.R., Gronow A., Gilbert B., Raemy E., Lamacchia C., Gabay C., Finckh A., Strowig T. Prevotella copri in individuals at risk for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2019;78:590–593. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An D., Oh S.F., Olszak T., Neves J.F., Avci F.Y., Erturk-Hasdemir D., Lu X., Zeissig S., Blumberg R.S., Kasper D.L. Sphingolipids from a symbiotic microbe regulate homeostasis of host intestinal natural killer T cells. Cell. 2014;156:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M.C., Vonaesch P., Saffarian A., Marteyn B.S., Sansonetti P.J. Shigella sonnei Encodes a Functional T6SS Used for Interbacterial Competition and Niche Occupancy. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21:769–776. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archambaud C., Nahori M.A., Soubigou G., Bécavin C., Laval L., Lechat P., Smokvina T., Langella P., Lecuit M., Cossart P. Impact of lactobacilli on orally acquired listeriosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:16684–16689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212809109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archambaud C., Sismeiro O., Toedling J., Soubigou G., Bécavin C., Lechat P., Lebreton A., Ciaudo C., Cossart P. The intestinal microbiota interferes with the microRNA response upon oral Listeria infection. MBio. 2013;4:e00707–e00713. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00707-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaud M., Chastanet A., Débarbouillé M. New vector for efficient allelic replacement in naturally nontransformable, low-GC-content, gram-positive bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:6887–6891. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6887-6891.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumugam M., Raes J., Pelletier E., Le Paslier D., Yamada T., Mende D.R., Fernandes G.R., Tap J., Bruls T., Batto J.M., MetaHIT Consortium Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2011;473:174–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balestrino D., Hamon M.A., Dortet L., Nahori M.A., Pizarro-Cerda J., Alignani D., Dussurget O., Cossart P., Toledo-Arana A. Single-cell techniques using chromosomally tagged fluorescent bacteria to study Listeria monocytogenes infection processes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:3625–3636. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02612-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäumler A.J., Sperandio V. Interactions between the microbiota and pathogenic bacteria in the gut. Nature. 2016;535:85–93. doi: 10.1038/nature18849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becattini S., Littmann E.R., Carter R.A., Kim S.G., Morjaria S.M., Ling L., Gyaltshen Y., Fontana E., Taur Y., Leiner I.M., Pamer E.G. Commensal microbes provide first line defense against Listeria monocytogenes infection. J. Exp. Med. 2017;214:1973–1989. doi: 10.1084/jem.20170495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briselden A.M., Moncla B.J., Stevens C.E., Hillier S.L. Sialidases (neuraminidases) in bacterial vaginosis and bacterial vaginosis-associated microflora. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992;30:663–666. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.3.663-666.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugiroux S., Beutler M., Pfann C., Garzetti D., Ruscheweyh H.J., Ring D., Diehl M., Herp S., Lötscher Y., Hussain S. Genome-guided design of a defined mouse microbiota that confers colonization resistance against Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Nat. Microbiol. 2016;2:16215. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffie C.G., Pamer E.G. Microbiota-mediated colonization resistance against intestinal pathogens. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13:790–801. doi: 10.1038/nri3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J.G., Lauber C.L., Walters W.A., Berg-Lyons D., Huntley J., Fierer N., Owens S.M., Betley J., Fraser L., Bauer M. Ultra-high-throughput microbial community analysis on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms. ISME J. 2012;6:1621–1624. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassaing B., Srinivasan G., Delgado M.A., Young A.N., Gewirtz A.T., Vijay-Kumar M. Fecal lipocalin 2, a sensitive and broadly dynamic non-invasive biomarker for intestinal inflammation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassaing B., Koren O., Goodrich J.K., Poole A.C., Srinivasan S., Ley R.E., Gewirtz A.T. Dietary emulsifiers impact the mouse gut microbiota promoting colitis and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2015;519:92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature14232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassaing B., Van de Wiele T., De Bodt J., Marzorati M., Gewirtz A.T. Dietary emulsifiers directly alter human microbiota composition and gene expression ex vivo potentiating intestinal inflammation. Gut. 2017;66:1414–1427. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis M.M., Hu Z., Klimko C., Narayanan S., Deberardinis R., Sperandio V. The gut commensal Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron exacerbates enteric infection through modification of the metabolic landscape. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:759–769. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Filippis F., Pasolli E., Tett A., Tarallo S., Naccarati A., De Angelis M., Neviani E., Cocolin L., Gobbetti M., Segata N., Ercolini D. Distinct Genetic and Functional Traits of Human Intestinal Prevotella copri Strains Are Associated with Different Habitual Diets. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;25:444–453.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Weirdt R., Possemiers S., Vermeulen G., Moerdijk-Poortvliet T.C., Boschker H.T., Verstraete W., Van de Wiele T. Human faecal microbiota display variable patterns of glycerol metabolism. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2010;74:601–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai M.S., Seekatz A.M., Koropatkin N.M., Kamada N., Hickey C.A., Wolter M., Pudlo N.A., Kitamoto S., Terrapon N., Muller A. A Dietary Fiber-Deprived Gut Microbiota Degrades the Colonic Mucus Barrier and Enhances Pathogen Susceptibility. Cell. 2016;167:1339–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desvaux M., Dumas E., Chafsey I., Chambon C., Hébraud M. Comprehensive appraisal of the extracellular proteins from a monoderm bacterium: theoretical and empirical exoproteomes of Listeria monocytogenes EGD-e by secretomics. J. Proteome Res. 2010;9:5076–5092. doi: 10.1021/pr1003642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon S.M., Lee E.J., Kotter C.V., Austin G.L., Gianella S., Siewe B., Smith D.M., Landay A.L., McManus M.C., Robertson C.E. Gut dendritic cell activation links an altered colonic microbiome to mucosal and systemic T-cell activation in untreated HIV-1 infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:24–37. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edman D.C., Pollock M.B., Hall E.R. Listeria monocytogenes L forms. I. Induction maintenance, and biological characteristics. J. Bacteriol. 1968;96:352–357. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.2.352-357.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elinav E., Strowig T., Kau A.L., Henao-Mejia J., Thaiss C.A., Booth C.J., Peaper D.R., Bertin J., Eisenbarth S.C., Gordon J.I., Flavell R.A. NLRP6 inflammasome regulates colonic microbial ecology and risk for colitis. Cell. 2011;145:745–757. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreyra J.A., Wu K.J., Hryckowian A.J., Bouley D.M., Weimer B.C., Sonnenburg J.L. Gut microbiota-produced succinate promotes C. difficile infection after antibiotic treatment or motility disturbance. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:770–777. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint H.J., Duncan S.H. Bacteroides and Prevotella. In: Batt C.A., editor. Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology. Elsevier; 2014. pp. 203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Gaboriau-Routhiau V., Rakotobe S., Lécuyer E., Mulder I., Lan A., Bridonneau C., Rochet V., Pisi A., De Paepe M., Brandi G. The key role of segmented filamentous bacteria in the coordinated maturation of gut helper T cell responses. Immunity. 2009;31:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh B.P., Klopfleisch R., Loh G., Blaut M. Commensal Akkermansia muciniphila exacerbates gut inflammation in Salmonella Typhimurium-infected gnotobiotic mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geirnaert A., Wang J., Tinck M., Steyaert A., Van den Abbeele P., Eeckhaut V., Vilchez-Vargas R., Falony G., Laukens D., De Vos M. Interindividual differences in response to treatment with butyrate-producing Butyricicoccus pullicaecorum 25-3T studied in an in vitro gut model. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2015;91:fiv054. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiv054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert J.A., Meyer F., Jansson J., Gordon J., Pace N., Tiedje J., Ley R., Fierer N., Field D., Kyrpides N. The Earth Microbiome Project: Meeting report of the “1 EMP meeting on sample selection and acquisition” at Argonne National Laboratory October 6 2010. Stand. Genomic Sci. 2010;3:249–253. doi: 10.4056/aigs.1443528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser P., Frangeul L., Buchrieser C., Rusniok C., Amend A., Baquero F., Berche P., Bloecker H., Brandt P., Chakraborty T. Comparative genomics of Listeria species. Science. 2001;294:849–852. doi: 10.1126/science.1063447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta V.K., Chaudhari N.M., Iskepalli S., Dutta C. Divergences in gene repertoire among the reference Prevotella genomes derived from distinct body sites of human. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:153. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1350-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herp S., Brugiroux S., Garzetti D., Ring D., Jochum L.M., Beutler M., Eberl C., Hussain S., Walter S., Gerlach R.G. Mucispirillum schaedleri Antagonizes Salmonella Virulence to Protect Mice against Colitis. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;25:681–694. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand F., Nguyen T.L., Brinkman B., Yunta R.G., Cauwe B., Vandenabeele P., Liston A., Raes J. Inflammation-associated enterotypes, host genotype, cage and inter-individual effects drive gut microbiota variation in common laboratory mice. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R4. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-1-r4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H.A., Khaneja R., Tam N.M., Cazzato A., Tan S., Urdaci M., Brisson A., Gasbarrini A., Barnes I., Cutting S.M. Bacillus subtilis isolated from the human gastrointestinal tract. Res. Microbiol. 2009;160:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov I.I., Atarashi K., Manel N., Brodie E.L., Shima T., Karaoz U., Wei D., Goldfarb K.C., Santee C.A., Lynch S.V. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 2009;139:485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson M.E., Hansson G.C. Preservation of mucus in histological sections, immunostaining of mucins in fixed tissue, and localization of bacteria with FISH. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;842:229–235. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-513-8_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson M.E., Phillipson M., Petersson J., Velcich A., Holm L., Hansson G.C. The inner of the two Muc2 mucin-dependent mucus layers in colon is devoid of bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:15064–15069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803124105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley K.A., Maiden M.C. BIGSdb: Scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:595. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur U.S., Shet A., Rajnala N., Gopalan B.P., Moar P., D H., Singh B.P., Chaturvedi R., Tandon R. High Abundance of genus Prevotella in the gut of perinatally HIV-infected children is associated with IP-10 levels despite therapy. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:17679. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35877-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.G., Becattini S., Moody T.U., Shliaha P.V., Littmann E.R., Seok R., Gjonbalaj M., Eaton V., Fontana E., Amoretti L. Microbiota-derived lantibiotic restores resistance against vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus. Nature. 2019;572:665–669. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1501-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen J.M. The immune response to Prevotella bacteria in chronic inflammatory disease. Immunology. 2017;151:363–374. doi: 10.1111/imm.12760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer P., Chow M.Y., Loessner M.J., Portnoy D.A., Calendar R. Construction, characterization, and use of two Listeria monocytogenes site-specific phage integration vectors. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:4177–4186. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.15.4177-4186.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leo S., Lazarevic V., Gaïa N., Estellat C., Girard M., Matheron S., Armand-Lefèvre L., Andremont A., Schrenzel J., Ruppé E. The intestinal microbiota predisposes to traveler’s diarrhea and to the carriage of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae after traveling to tropical regions. Gut Microbes. 2019;10:631–641. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2018.1564431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley R.E. Gut microbiota in 2015: Prevotella in the gut: choose carefully. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016;13:69–70. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M.F., Zhang B.C., Li J., Sun L. Sil: a Streptococcus iniae bacteriocin with dual role as an antimicrobial and an immunomodulator that inhibits innate immune response and promotes S. iniae infection. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnan M.J., Mascola L., Lou X.D., Goulet V., May S., Salminen C., Hird D.W., Yonekura M.L., Hayes P., Weaver R. Epidemic listeriosis associated with Mexican-style cheese. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988;319:823–828. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809293191303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozupone C.A., Rhodes M.E., Neff C.P., Fontenot A.P., Campbell T.B., Palmer B.E. HIV-induced alteration in gut microbiota: driving factors, consequences, and effects of antiretroviral therapy. Gut Microbes. 2014;5:562–570. doi: 10.4161/gmic.32132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackanes G.B. The Immunological Basis of Acquired Cellular Resistance. J. Exp. Med. 1964;120:105–120. doi: 10.1084/jem.120.1.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda Y., Kurakawa T., Umemoto E., Motooka D., Ito Y., Gotoh K., Hirota K., Matsushita M., Furuta Y., Narazaki M. Dysbiosis Contributes to Arthritis Development via Activation of Autoreactive T Cells in the Intestine. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:2646–2661. doi: 10.1002/art.39783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez B., Suárez J.E., Rodríguez A. Lactococcin 972 : a homodimeric lactococcal bacteriocin whose primary target is not the plasma membrane. Microbiology. 1996;142:2393–2398. doi: 10.1099/00221287-142-9-2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maury M.M., Tsai Y.H., Charlier C., Touchon M., Chenal-Francisque V., Leclercq A., Criscuolo A., Gaultier C., Roussel S., Brisabois A. Uncovering Listeria monocytogenes hypervirulence by harnessing its biodiversity. Nat. Genet. 2016;48:308–313. doi: 10.1038/ng.3501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazmanian S.K., Liu C.H., Tzianabos A.O., Kasper D.L. An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system. Cell. 2005;122:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazmanian S.K., Round J.L., Kasper D.L. A microbial symbiosis factor prevents intestinal inflammatory disease. Nature. 2008;453:620–625. doi: 10.1038/nature07008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellin J.R., Tiensuu T., Bécavin C., Gouin E., Johansson J., Cossart P. A riboswitch-regulated antisense RNA in Listeria monocytogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:13132–13137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304795110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura A., Criscuolo A., Pouseele H., Maury M.M., Leclercq A., Tarr C., Björkman J.T., Dallman T., Reimer A., Enouf V. Whole genome-based population biology and epidemiological surveillance of Listeria monocytogenes. Nat. Microbiol. 2016;2:16185. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T.L., Vieira-Silva S., Liston A., Raes J. How informative is the mouse for human gut microbiota research? Dis. Model. Mech. 2015;8:1–16. doi: 10.1242/dmm.017400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostling C.E., Lindgren S.E. Inhibition of enterobacteria and Listeria growth by lactic, acetic and formic acids. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1993;75:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb03402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen H.K., Gudmundsdottir V., Nielsen H.B., Hyotylainen T., Nielsen T., Jensen B.A., Forslund K., Hildebrand F., Prifti E., Falony G., MetaHIT Consortium Human gut microbes impact host serum metabolome and insulin sensitivity. Nature. 2016;535:376–381. doi: 10.1038/nature18646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Precup G., Vodnar D.C. Gut Prevotella as a possible biomarker of diet and its eubiotic versus dysbiotic roles: a comprehensive literature review. Br. J. Nutr. 2019;122:131–140. doi: 10.1017/S0007114519000680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quereda J.J., Dussurget O., Nahori M.A., Ghozlane A., Volant S., Dillies M.A., Regnault B., Kennedy S., Mondot S., Villoing B. Bacteriocin from epidemic Listeria strains alters the host intestinal microbiota to favor infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:5706–5711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523899113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quévrain E., Maubert M.A., Michon C., Chain F., Marquant R., Tailhades J., Miquel S., Carlier L., Bermúdez-Humarán L.G., Pigneur B. Identification of an anti-inflammatory protein from Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a commensal bacterium deficient in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2016;65:415–425. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakoff-Nahoum S., Foster K.R., Comstock L.E. The evolution of cooperation within the gut microbiota. Nature. 2016;533:255–259. doi: 10.1038/nature17626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolhion N., Chassaing B. When pathogenic bacteria meet the intestinal microbiota. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2016;371:20150504. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Round J.L., Mazmanian S.K. Inducible Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell development by a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiota. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:12204–12209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909122107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sana T.G., Flaugnatti N., Lugo K.A., Lam L.H., Jacobson A., Baylot V., Durand E., Journet L., Cascales E., Monack D.M. Salmonella Typhimurium utilizes a T6SS-mediated antibacterial weapon to establish in the host gut. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E5044–E5051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608858113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher J.U., Sczesnak A., Longman R.S., Segata N., Ubeda C., Bielski C., Rostron T., Cerundolo V., Pamer E.G., Abramson S.B. Expansion of intestinal Prevotella copri correlates with enhanced susceptibility to arthritis. eLife. 2013;2:e01202. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy M.K., Lynch S.V. Role of the lung microbiome in HIV pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS. 2018;13:45–52. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si J., You H.J., Yu J., Sung J., Ko G. Prevotella as a Hub for Vaginal Microbiota under the Influence of Host Genetics and Their Association with Obesity. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Wilkinson B.J., Standiford T.J., Akinbi H.T., O’Riordan M.X. Fatty acids regulate stress resistance and virulence factor production for Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:5274–5284. doi: 10.1128/JB.00045-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Abbeele P., Roos S., Eeckhaut V., MacKenzie D.A., Derde M., Verstraete W., Marzorati M., Possemiers S., Vanhoecke B., Van Immerseel F., Van de Wiele T. Incorporating a mucosal environment in a dynamic gut model results in a more representative colonization by lactobacilli. Microb. Biotechnol. 2012;5:106–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2011.00308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Abbeele P., Belzer C., Goossens M., Kleerebezem M., De Vos W.M., Thas O., De Weirdt R., Kerckhof F.M., Van de Wiele T. Butyrate-producing Clostridium cluster XIVa species specifically colonize mucins in an in vitro gut model. ISME J. 2013;7:949–961. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright D.P., Rosendale D.I., Robertson A.M. Prevotella enzymes involved in mucin oligosaccharide degradation and evidence for a small operon of genes expressed during growth on mucin. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;190:73–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

16S rRNA Gene Sequence Analysis

Analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequence was performed exactly as previously described (Chassaing et al., 2015). Our full 16S rRNA gene sequence data are deposited under Study ID PRJEB34638 in the European Nucleotide Archive database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena).