Abstract

Dexmedetomidine (DEX), a highly specific and selective α2 adrenergic receptor agonist, has been demonstrated to possess potential cardioprotective effects. However, the mechanisms underlying this process remain to be fully illuminated. In the present study, a myocardial infarction (MI) animal model was generated by permanently ligating the left anterior descending coronary artery in mice. Cardiac function and collagen content were evaluated by transthoracic echocardiography and picrosirius red staining, respectively. Apoptosis was determined by the relative expression levels of Bax and Bcl-2 and the myocardial caspase-3 activity. Additionally, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NOX)-derived oxidative stress was evaluated by the relative expression of Nox2 and Nox4, along with the myocardial contents of malondialdehyde (MDA) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. It was demonstrated that intraperitoneal DEX treatment (20 µg/kg/day) improved the systolic function of the left ventricle, and decreased the fibrotic changes in post-myocardial infarction mice, which was paralleled by a decrease in the levels of apoptosis. Subsequent experiments indicated that the restoration of redox signaling was achieved by DEX administration, and the over-activation of NOXs, including Nox2 and Nox4, was markedly inhibited. In conclusion, this present study suggested that DEX was cardioprotective and limited the excess production of NOX-derived ROS in ischemic heart disease, implying that DEX is a promising novel drug, especially for patients who have suffered MI.

Keywords: cardiac dysfunction, ischemic injury, dexmedetomidine, apoptosis, reactive oxidative stress

Introduction

Despite the advance of therapeutic approaches, ischemic heart disease, in particular myocardial infarction (MI), remains a major cause of left ventricular dysfunction or heart failure (1,2). Hypoxia and hypoperfusion disrupt regional redox homeostasis, trigger inflammatory cascades and subsequently facilitate excessive cell death and cardiac remodeling, resulting in the deterioration of cardiac dysfunction. During this process, the sympathetic stress response may also exacerbate the imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and the protective antioxidant defense system, thereby increasing the levels of oxidative stress in the heart tissue (3).

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase (NOX) is a prominent source of excess ROS in the cardiovascular system (4). Treatments targeting NOX inhibition have demonstrated therapeutic success in a number of previous studies (5–7). Following MI, NOX expression is significantly increased and serves a critical role in cardiac remodeling in the infarcted myocardium. The adverse remodeling of the left ventricle is an unfavorable development associated with myocardial hypertrophy and increased the sympathetic activity (8–10). However, it is unclear whether dexmedetomidine (DEX)-mediated sympathetic sedation contributes to curbing NOX-derived ROS, thereby protecting MI-induced cardiac dysfunction.

DEX, with an α2 to α1 selectivity ratio of 1,600:1, is a highly selective α adrenergic receptor agonist (11,12). It targets the α2 adrenergic receptors in the central nervous system to inhibit the activity of sympathetic outflow, producing the effects of analgesia, anxiolysis and sedation (13,14). Therefore, the application of DEX may alleviate the sympathetic stress response induced by acute MI injury. The present study involved an animal model of permanent coronary ligation and the cardio-protective effects of DEX were analyzed. It was demonstrated that DEX hindered NOX-derived oxidative stress and improved the systolic performance of the damaged left ventricle following MI.

Materials and methods

Induction of myocardial infarction and drug treatment

Male C57BL/6J mice (8–10 weeks old, n=55), obtained from the Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University, were divided into 4 groups (n=12/group; others failing to survive the surgery): Sham + Normal Saline (NS) group, Sham + DEX group, MI + NS group and MI + DEX group. The mice were maintained in air-filtered units at 21±2°C and 50±15% relative humidity under a 12-h light/dark cycle. Mice were randomized and anesthetized using inhaled isoflurane (2%) with the heart rate monitored simultaneously. Surgical procedures were performed as described previously (15). Briefly, mice in the MI + NS and MI + DEX groups received a left thoracotomy and the left anterior descending coronary artery was permanently ligated by using a 7.0 polypropylene suture. The surgery in Sham + NS and Sham + DEX groups involved an identical procedure, with the exception of coronary artery ligation. DEX treatment was initiated immediately following surgery.

Mice in the Sham + DEX and MI + DEX groups were treated with DEX (Jiangsu Nhwa Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; 20 µg/kg/day intraperitoneally), as previously described (16). Mice in the Sham + NS and MI + NS groups were administered normal saline injection only. Throughout these experiments, the therapeutic treatments were administered once per day for 7 days, and no significant side effects were observed in any animals following drug treatment. For ex vivo analyses of protein expression and histological study, animals were sacrificed using anesthesia of inhaled isoflurane, followed by cervical dislocation, 3 or 7 days after the surgery. All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine.

Echocardiography analysis

A total of 1 week after surgery, cardiac function was evaluated by transthoracic echocardiography with a high-resolution ultrasound imaging system (Vevo 2100; FUJIFILM VisualSonics, Inc.) equipped with a 30-MHz mechanical transducer. M-mode tracings were used to measure percentage of ejection fraction (EF%) and fractional shortening (FS%) as described previously (17). M-mode measurement data represent 3 to 6 averaged cardiac cycles from at least 2 scans/mouse.

Histological analysis

Collagen content in the heart was analyzed using picrosirius red staining. Briefly, the hearts were quickly removed, weighed and then fixed in 4% buffered paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 48 h. The hearts were embedded in paraffin, and then cut into 6 µm serial sections using a microtome. Picrosirius red staining (0.5% Picrosirius red at room temperature for 20 min) was performed to evaluate the severity of fibrosis. Images were captured with an Olympus light microscope (magnification, ×400) and quantitatively analyzed using Image-Pro Plus v.6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Inc.).

Western blot analysis

A total of 3 days after surgery, tissue samples of the left ventricular myocardium were homogenized in in RIPA lysis buffer containing 1% PMSF. Protein concentrations in supernatants were measured with a bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Equal amounts of prepared proteins (50 µg/lane) were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE, separated by electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Following blocking in 5% non-fat milk PBS for 2 h, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-Nox2 (cat. no. ab80508; Abcam; 1:1,000), anti-Nox4 (cat. no. ab195524; Abcam; 1:1,000), anti-Bax (cat. no. ab32503; Abcam; 1:1,000), anti-Bcl-2 (cat. no. ab182858; Abcam; 1:1,000) or β-actin (cat. no. ab8227; Abcam; 1:1,000) primary antibodies, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (cat. no. 7074; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; 1:5,000) for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (EMD Millipore) and quantified by Image-Pro Plus v.6.0.

Caspase-3 activity assay

Myocardial caspase-3 activity was determined by colorimetric assay kits (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), as described previously (18). The heart tissue was collected from mice 3 days after MI and the assays were performed according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Malondialdehyde (MDA) and superoxide dismutase (SDS) assay

At the end of the experimental period, mice were sacrificed, the hearts were excised and heart tissues were weighed (wet weight) and homogenized in ice-cold PBS. The homogenates were centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C to obtain the supernatant. The MDA content, a reliable index of ROS-induced lipid peroxidation, and SOD activity were measured by commercially available kits according to the manufacturer's protocol (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute Co., Ltd.).

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean and were analyzed by paired or unpaired Student's t-test unless otherwise stated. Differences between multiple groups were determined with one way analysis of variance followed by a Bonferroni post hoc analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Data were analyzed with the use of GraphPad Prism v.5 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Results

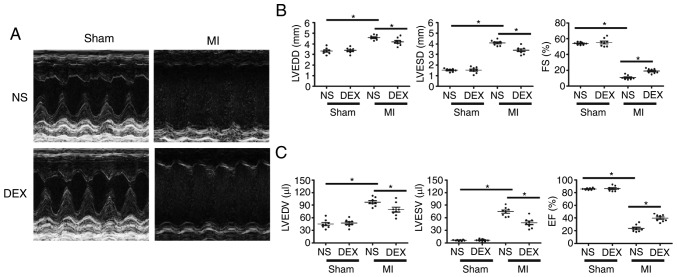

DEX treatment leads to an improvement in LV dysfunction following MI

As demonstrated in Fig. 1, echocardiographic parameters were measured in each group at day 7 post-MI. For sham mice, the results revealed no significant changes in ejection fraction or fractional shortening regardless of whether or not DEX treatment was given. LAD ligation resulted in the dilatation of LV and a serious impairment of cardiac function. Notably, the MI-induced acceleration of cardiac dilatation and deterioration of LV function were inhibited in MI + DEX mice, in comparison with those in the MI + NS mice.

Figure 1.

Functional analysis of the left ventricle with echocardiography. (A) Representative M-mode echocardiograms from the Sham + NS, Sham + DEX, MI + NS, and MI + DEX mice. (B) The mean left ventricular LVEDD, LVESD and FS in the Sham + NS, Sham + DEX, MI + NS, and MI + DEX-treated mice. (C) The mean left ventricular LVEDV, LVESV and EF in the Sham + NS, Sham + DEX, MI + NS, and MI + DEX mice. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. n=6. *P<0.05. NS, normal saline; DEX, dexmedetomidine; MI, myocardial infarction; LVEDD, left ventricle end-diastolic dimension; LVESD, LV end-systolic dimension; FS, fractional shortening.

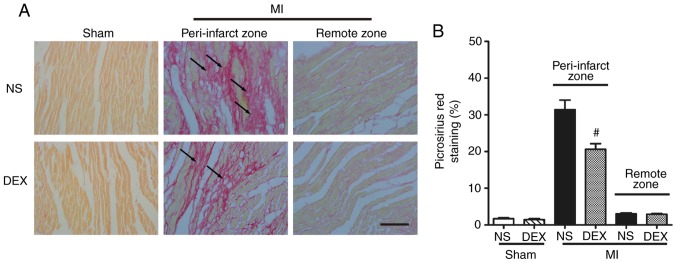

DEX treatment mitigates cardiac fibrosis following MI

Picrosirius red staining was performed to determine the severity of fibrotic changes in each group. No significant difference was observed in the positive picrosirius red stained areas between the Sham + NS and Sham + DEX mice. In the MI mice, DEX treatment resulted in significantly decreased collagen content in the peri-infarct zone (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Analysis of pathological cardiac remodeling with picrosirius red staining. (A) Representative images of picrosirius red-stained sections in the Sham + NS, Sham + DEX, MI + NS, and MI + DEX mice. Scale bar, 50 µm. (B) Quantitative analysis of picrosirius red-positive area in the Sham + NS, Sham + DEX, MI + NS, and MI + DEX mice. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (n=6. #P<0.05 vs. MI + NS group. NS, normal saline; DEX, dexmedetomidine; MI, myocardial infarction.

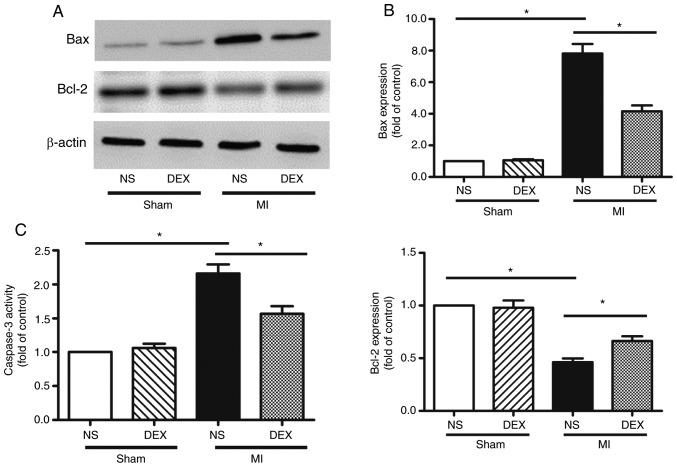

DEX treatment protects the myocardium against apoptosis after MI

The levels apoptosis of myocardium was analyzed by western blot analysis and the detection of caspase-3 activity. The data from the western blot analysis performed in the present study revealed significant upregulation of Bax and downregulation of Bcl-2 expression in myocardium following MI, indicating the occurrence of enhanced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. MI-induced apoptosis was decreased following the administration of DEX (Fig. 3A and B).

Figure 3.

Analysis of apoptosis with western blot analysis and caspase-3 activity assay. (A) Representative gel images and (B) quantitative densitometric analysis of western blot analysis data demonstrating the expression levels of Bax and Bcl-2 proteins in the Sham + NS, Sham + DEX, MI + NS, and MI + DEX mice. (C) Analysis of caspase-3 activity assay in the Sham + NS, Sham + DEX, MI + NS, and MI + DEX mice. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (n=6. *P<0.05. NS, normal saline; DEX, dexmedetomidine; MI, myocardial infarction.

Caspase-3 is involved in a number of important events in the apoptosis process (19). LAD ligation led to the upregulation of caspase-3 activity compared with sham mice. The data from the present study also revealed that this pro-apoptotic change was markedly hindered by the administration of DEX (Fig. 3C).

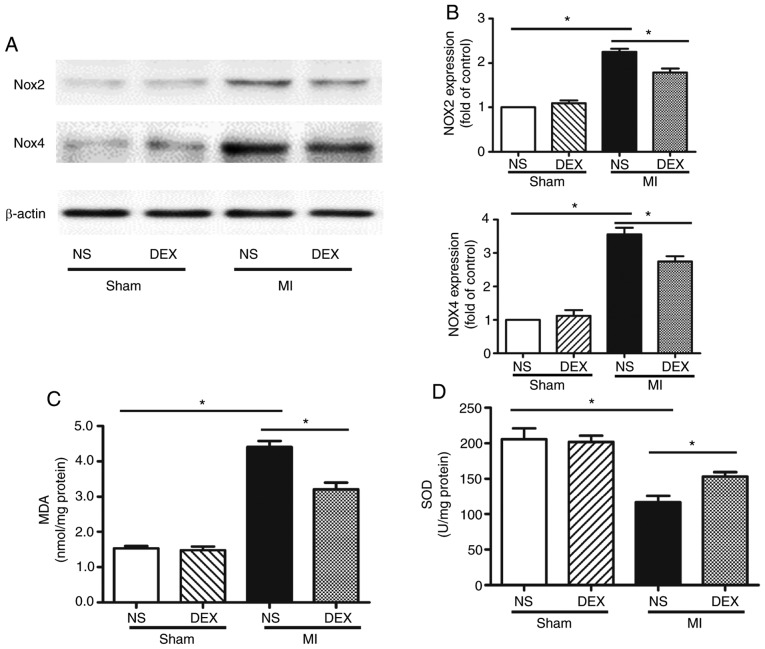

DEX treatment inhibits NOX-derived oxidative stress in myocardium following MI

Whether NOX served an important role in DEX-induced cardiac protection was examined. The protein expression levels of NOX2 and NOX4 were evaluated by western blot analysis. The results revealed that DEX significantly decreased the expression levels of both NOX2 and NOX4, which were upregulated following MI (Fig. 4A and B).

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis of NOX2 and NOX4 expression and SOD and MDA assays. (A) Representative gel images and (B) quantitative densitometric analysis of western blot analysis data demonstrating the expression levels of NOX2 and NOX4 proteins in the Sham + NS, Sham + DEX, MI + NS, and MI + DEX mice. (C) Analysis of MDA content in the Sham + NS, Sham + DEX, MI + NS, and MI + mice. (D) Analysis of SOD activity in the Sham + NS, Sham + DEX, MI + NS, and MI + DEX mice. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. n=6. *P<0.05. NOX, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase; NS, normal saline; DEX, dexmedetomidine; MI, myocardial infarction.

MDA is an oxidative stress marker, the expression levels of which are considered the index of ROS-induced lipid peroxidation in cardiac tissue (20). In the present study, in the cardiac tissue, MI significantly increased the MDA level in comparison with the sham mice. In the MI mice, treatment with DEX resulted in a significant decrease in MDA level in comparison with NS-treated mice.

In addition, SOD, a component of several myocardial endogenous antioxidants, was decreased significantly in the MI groups as compared with the sham groups, whereas SOD levels were increased significantly in MI + DEX mice compared with MI + NS mice.

Discussion

Ischemic injury leads to the loss of viable myocardium, which is followed by adverse cardiac remodeling. Eventually, progressive changes in the molecular and structural components of the myocardium result in cardiac dysfunction. In the present study, the administration of DEX, a highly selective α2 adrenergic receptor agonist, was identified as a protective factor for the recovery of heart tissue post-MI. DEX treatment contributed to the successful healing process and limited the level of oxidative stress, through the over-activation of NOXs.

Clinically, DEX is frequently prescribed during perioperative periods, and contributes to an enhancement of vagus nerve excitability, hemodynamic stability and permits the use of a lower dosage of anesthetic with sedation and analgesia (21). As an anesthetic adjuvant, DEX produces sedative and analgesic effects, primarily through its agonistic action on the α2 adrenergic receptors in the locus coeruleus of the pons and the spinal cord (22). Without depressing respiration, DEX is also a potential regulator of inflammatory and immune responses (23,24). These properties suggest that DEX may have an effect on post-MI remodeling and cardiac dysfunction, in spite of the fact that DEX is not a component of conventional therapies for patients who have suffered MI. In the present study, DEX treatment was identified to markedly decrease the levels of fibrotic changes and improve the cardiac performance after MI. While the deposition of non-contractile scar tissue is important for a successful healing process, excess fibrogenesis is a key component of adverse cardiac remodeling.

The fibrosis and dysfunction of MI hearts may be attributed to the loss of viable myocardium. Bax, Bcl-2 and caspase-3 are all closely associated with apoptosis (17). The present study demonstrated that DEX administration restored the Bax and Bcl-2 ratio and simultaneously decreased the activity of caspase-3, implying that DEX decreased the levels of apoptosis of the myocardium. The underlying mechanism for the anti-apoptosis properties of DEX requires further investigation.

Oxidative stress serves a vital role in the development of post-MI remodeling and cardiomyocytic apoptosis following MI (25,26). SOD and MDA are two common indexes used for evaluating the ability to eliminate oxygen free radicals in cells (27). SOD, engaged in scavenging free radicals, protects cells from damage elicited by ROS, while MDA, together with excessive oxyradicals, attacks the cell membrane, leading to cell death. The present study revealed that ischemic injury resulted in an increased MDA level and a decreased SOD level; furthermore, the homeostasis between MDA and SOD was partially restored following the administration of DEX, suggesting that DEX may participate in the inhibition of the activated oxidative stress response.

Previous studies have confirmed the importance of ROS-generating NOX family in redox signaling following ischemic injury (28,29). Of the 5 NOX family members, Nox2 and Nox4 are expressed in the murine heart (17,30). In the present study, the expression levels of these two molecules were analyzed by western blot analysis. The results indicated that their expression levels were both decreased following the administration of DEX in MI mice. Understanding of the mechanisms of DEX-induced cardioprotective signaling is complex, as α2 adrenergic receptors are also present in the myocardial tissue (31,32). In addition to the action of DEX-induced neurohumoral systemic modulation, the direct stimulation of cardiac α2 adrenergic receptors may also facilitate the benefits of DEX administration.

Taken together, the results of the present study demonstrated that the administration of DEX promoted recovery from ischemic injury and improved the performance of damaged left ventricles following MI. The therapeutic effect may be associated with the inhibition of excess NOX-derived ROS, thereby decelerating apoptosis in the myocardium and the subsequent adverse cardiac remodeling.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81570316, 81670389, 81770249 and 81800375).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

GT and RZ provided the concept, administration, supervision, resources and funding for the present study, and validated the data. HH, DD, JZ and JH collected the data. HH, DD and LL analyzed the data. DD and JZ analyzed the data with the software. HH, DD and JH prepared the figures. HH and DD wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Cahill TJ, Choudhury RP, Riley PR. Heart regeneration and repair after myocardial infarction: Translational opportunities for novel therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:699–717. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lefer DJ, Marban E. Is cardioprotection dead? Circulation. 2017;136:98–109. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.027039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malfitano C, Barboza CA, Mostarda C, da Palma RK, dos Santos CP, Rodrigues B, Freitas SC, Belló-Klein A, Llesuy S, Irigoyen MC, De Angelis K. Diabetic hyperglycemia attenuates sympathetic dysfunction and oxidative stress after myocardial infarction in rats. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:131. doi: 10.1186/s12933-014-0131-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li B, Tian J, Sun Y, Xu TR, Chi RF, Zhang XL, Hu XL, Zhang YA, Qin FZ, Zhang WF. Activation of NADPH oxidase mediates increased endoplasmic reticulum stress and left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction in rabbits. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852:805–815. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu L, Yang G, Zhang X, Wang P, Weng X, Yang Y, Li Z, Fang M, Xu Y, Sun A, Ge J. Megakaryocytic leukemia 1 (MKL1) bridges epigenetic activation of NADPH oxidase in macrophages to cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2018;138:2820–2836. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cadenas S. ROS and redox signaling in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury and cardioprotection. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;117:76–89. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asensio-Lopez MDC, Lax A, Fernandez Del Palacio MJ, Sassi Y, Hajjar RJ, Pascual-Figal DA. Pharmacological inhibition of the mitochondrial NADPH oxidase 4/PKCalpha/Gal-3 pathway reduces left ventricular fibrosis following myocardial infarction. Transl Res. 2018;199:4–23. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi S, Liang J, Liu T, Yuan X, Ruan B, Sun L, Tang Y, Yang B, Hu D, Huang C. Depression increases sympathetic activity and exacerbates myocardial remodeling after myocardial infarction: Evidence from an animal experiment. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang BS, Leenen FH. The brain renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system: A major mechanism for sympathetic hyperactivity and left ventricular remodeling and dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2009;6:81–88. doi: 10.1007/s11897-009-0013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiong L, Liu Y, Zhou M, Wang G, Quan D, Shuai W, Shen C, Kong B, Huang C, Huang H. Targeted ablation of cardiac sympathetic neurons attenuates adverse post-infarction remodeling and left ventricle dysfunction. Exp Physiol. 2018;103:1221–1229. doi: 10.1113/EP086928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji F, Li Z, Nguyen H, Young N, Shi P, Fleming N, Liu H. Perioperative dexmedetomidine improves outcomes of cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2013;127:1576–1584. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menon DV, Wang Z, Fadel PJ, Arbique D, Leonard D, Li JL, Victor RG, Vongpatanasin W. Central sympatholysis as a novel countermeasure for cocaine-induced sympathetic activation and vasoconstriction in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:626–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parati G, Esler M. The human sympathetic nervous system: Its relevance in hypertension and heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1058–1066. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun Z, Zhao T, Lv S, Gao Y, Masters J, Weng H. Dexmedetomidine attenuates spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injury through both anti-inflammation and anti-apoptosis mechanisms in rabbits. J Transl Med. 2018;16:209. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1583-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan X, Zhang H, Fan Q, Hu J, Tao R, Chen Q, Iwakura Y, Shen W, Lu L, Zhang Q, Zhang R. Dectin-2 deficiency modulates Th1 differentiation and improves wound healing after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2017;120:1116–1129. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.310260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sun Y, Jiang C, Jiang J, Qiu L. Dexmedetomidine protects mice against myocardium ischaemic/reperfusion injury by activating an AMPK/PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2017;44:946–953. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han H, Zhu J, Zhu Z, Ni J, Du R, Dai Y, Chen Y, Wu Z, Lu L, Zhang R. p-Cresyl sulfate aggravates cardiac dysfunction associated with chronic kidney disease by enhancing apoptosis of cardiomyocytes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001852. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.001852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu J, Deng G, Tian Y, Pu Y, Cao P, Yuan W. An in vitro investigation into the role of bone marrowderived mesenchymal stem cells in the control of disc degeneration. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:5701–5708. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang B, Ye D, Wang Y. Caspase-3 as a therapeutic target for heart failure. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2013;17:255–263. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.745513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J, Wang H, Hao P, Xue L, Wei S, Zhang Y, Chen Y. Inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 by oxidative stress is associated with cardiac dysfunction in diabetic rats. Mol Med. 2011;17:172–179. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong J, Guo X, Yang S, Li L. The effects of dexmedetomidine preconditioning on aged rat heart of ischaemia reperfusion injury. Res Vet Sci. 2017;114:489–492. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2017.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen V, Tiemann D, Park E, Salehi A. Alpha-2 agonists. Anesthesiol Clin. 2017;35:233–245. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu W, Yu W, Weng Y, Wang Y, Sheng M. Dexmedetomidine ameliorates the inflammatory immune response in rats with acute kidney damage. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14:3602–3608. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X, Wang J, Qian W, Zhao J, Sun L, Qian Y, Xiao H. Dexmedetomidine inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin 6 in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated astrocytes by suppression of c-Jun N-terminal kinases. Inflammation. 2014;37:942–949. doi: 10.1007/s10753-014-9814-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hou L, Guo J, Xu F, Weng X, Yue W, Ge J. Cardiomyocyte dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase1 attenuates left-ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial infarction: Involvement in oxidative stress and apoptosis. Basic Res Cardiol. 2018;113:28. doi: 10.1007/s00395-018-0685-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Becher UM, Ghanem A, Tiyerili V, Furst DO, Nickenig G, Mueller CF. Inhibition of leukotriene C4 action reduces oxidative stress and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes and impedes remodeling after myocardial injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:570–577. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jimenez-Fernandez S, Gurpegui M, Díaz-Atienza F, Perez-Costillas L, Gerstenberg M, Correll CU. Oxidative stress and antioxidant parameters in patients with major depressive disorder compared to healthy controls before and after antidepressant treatment: Results from a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:1658–1667. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14r09179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu Q, Lee CF, Wang W, Karamanlidis G, Kuroda J, Matsushima S, Sadoshima J, Tian R. Elimination of NADPH oxidase activity promotes reductive stress and sensitizes the heart to ischemic injury. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000555. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cave AC, Brewer AC, Narayanapanicker A, Ray R, Grieve DJ, Walker S, Shah AM. NADPH oxidases in cardiovascular health and disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:691–728. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsushima S, Tsutsui H, Sadoshima J. Physiological and pathological functions of NADPH oxidases during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2014;24:202–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imamura M, Lander HM, Levi R. Activation of histamine H3-receptors inhibits carrier-mediated norepinephrine release during protracted myocardial ischemia. Comparison with adenosine A1-receptors and alpha2-adrenoceptors. Circ Res. 1996;78:475–481. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.78.3.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zefirov TL, Khisamieva LI, Ziyatdinova NI, Zefirov AL. Selective blockade of α2-adrenoceptor subtypes modulates contractility of rat myocardium. Bull Exp Biol Med. 2016;162:177–179. doi: 10.1007/s10517-016-3569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.