Abstract

The present study reports on the frequency and the spectrum of genetic variants causative of monogenic diabetes in Russian children with non-type 1 diabetes mellitus. The present study included 60 unrelated Russian children with non-type 1 diabetes mellitus diagnosed before the age of 18 years. Genetic variants were screened using whole-exome sequencing (WES) in a panel of 35 genes causative of maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY) and transient or permanent neonatal diabetes. Verification of the WES results was performed using PCR-direct sequencing. A total of 38 genetic variants were identified in 33 out of 60 patients (55%). The majority of patients (27/33, 81.8%) had variants in MODY-related genes: GCK (n=19), HNF1A (n=2), PAX4 (n=1), ABCC8 (n=1), KCNJ11 (n=1), GCK+HNF1A (n=1), GCK+BLK (n=1) and GCK+BLK+WFS1 (n=1). A total of 6 patients (6/33, 18.2%) had variants in MODY-unrelated genes: GATA6 (n=1), WFS1 (n=3), EIF2AK3 (n=1) and SLC19A2 (n=1). A total of 15 out of 38 variants were novel, including GCK, HNF1A, BLK, WFS1, EIF2AK3 and SLC19A2. To summarize, the present study demonstrates a high frequency and a wide spectrum of genetic variants causative of monogenic diabetes in Russian children with non-type 1 diabetes mellitus. The spectrum includes previously known and novel variants in MODY-related and unrelated genes, with multiple variants in a number of patients. The prevalence of GCK variants indicates that diagnostics of monogenic diabetes in Russian children may begin with testing for MODY2. However, the remaining variants are present at low frequencies in 9 different genes, altogether amounting to ~50% of the cases and highlighting the efficiency of using WES in non-GCK-MODY cases.

Keywords: monogenic diabetes, maturity onset diabetes of the young, whole-exome sequencing, genetic variants, children

Introduction

Monogenic diabetes accounts for 1–6% of pediatric diabetes patients with the highest incidence among patients manifesting non-type 1 diabetes mellitus in childhood or adolescence (1).

A large, clinically heterogeneous group of dominantly inherited disorders linked to primary β-cell dysfunction is classified as maturity onset diabetes in the young (MODY). To date, 13 genes causative of 13 types of MODY are known (2). MODY is typically diagnosed before 25 years of age; it is non-insulin dependent and its symptoms are usually mild. However, due to the variety of clinical forms caused by a wide spectrum of mutations in MODY-related genes, different treatment strategies are used: From appropriate diet and physical activity to oral and/or insulin therapy.

Monogenic diabetes also includes a number of non-MODY transient or permanent neonatal forms occurring under 6 months of age. More than 20 genes are known to be related to congenital neonatal diabetes (3). Depending on the gene involved, neonatal diabetes may follow patterns of dominant or recessive inheritance and may be isolated or associated with a variety of syndromic features (4). However, due to a very early onset of diabetes, hyperglycemia is often diagnosed prior to other syndromic features. The treatment strategy for non-MODY neonatal diabetes depends on the specific genetic defect causing the diabetic phenotype.

Molecular genetic testing is highly recommended for patients suspected of monogenic diabetes as it allows tailoring treatments to specific etiological mechanisms. Up until recently, search for diabetes-related mutations was usually performed by Sanger sequencing and was therefore limited to only a few genes, leaving a considerable proportion of cases without a known cause. Moreover, a number of studies have demonstrated that frequencies of certain monogenic diabetes subtypes vary strongly among different populations (5), challenging the development of unified recommendations for the target gene choice. An efficient technology to detect previously known and to reveal novel mutations related to monogenic diabetes is next-generation sequencing. This technique allows for a rapid analysis of an unlimited number of genes and may provide valuable knowledge on the genetic variants causative of monogenic diabetes in different populations.

Here, using targeted whole-exome sequencing (WES), we studied the frequency and the spectrum of genetic variants causative of monogenic diabetes in a cohort of Russian children with non-type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Materials and methods

Study group

A total of 60 unrelated patients with diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance (pre-diabetes) were prospectively included in the study. All the patients were of Russian ethnicity and resided in Northwest Russia. In accordance with the guidelines of the American Diabetes Association (6), the diagnoses were based on plasma glucose criteria, either the fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and/or the 2-h plasma glucose (2-h PG) value after a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and/or the HbA1C criteria. All the patients had an onset of diabetes before the age of 18 years and a detectable C-peptide secretion (or a detectable insulin level in the absence of insulin therapy) and were negative for insulin-, islet-cell-, tyrosinphosphatase IA2-, and glutamate decarboxylase-autoantibodies. The exclusion criterion was the presence of the already confirmed syndrome associated with impaired glucose metabolism (such as Prader-Willi syndrome). In 59 cases, family history was available, and in 41 of them, it was positive for diabetes. All the patients were referred to the study by their medical supervisors.

Sample preparation and whole-exome sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood by Magna Pure System (Roche) using the standard protocol. Exome DNA libraries were prepared from 100 ng DNA using TruSeq® Exome Sample Preparation kit (Illumina, Inc.), following the manufacturer's instructions. Libraries were sequenced on Illumina HiSeq 2500 in 2×100 PE mode. An average of 63.6 million sequencing reads were obtained for each sample, yielding ~50× mean coverage of CDS regions and an average of 89% of CDS bases covered at least 10×.

Bioinformatic analysis

Bioinformatic analysis of the WES data was done using a pipeline based on bwa v.0.7.12-r1044 aligner, Picard tools v.2.0.1, and Genome Analysis Tool kit (GATK) v.3.5 software with all the necessary preprocessing steps required by the GATK Best Practices workflow (https://software.broadinstitute.org/gatk/best-practices/) (7,8). Target enrichment metrics were collected using the Picard CalculateHsMetrics tool. Variant calling was done using GATK HaplotypeCaller in the cohort genotyping mode with 250 samples included into the cohort (samples with a similar ethnical background from St. Petersburg State University Biobank were used for cohort padding). Variants were filtered using variant quality score recalibration (VQSR) and annotated with SnpEff and SnpSift tools (version 4.2). Additional annotations included the following information: rsID of known variants from dbSNP (build 146), allele frequency (AF) from large sequencing consortia-1000 Genomes (9), Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) (10), and ESP6500 (11); and pathogenicity predictions by Polyphen-2 (12), SIFT (13), PROVEAN (14) obtained from dbNSFP database (15) and by Human Splicing Finder (16) and DDIG (17). For additional prediction of protein stability changes caused by missence mutations with uncertain significance, I-Mutant 2.0 (18) was used. Variant ranking was done using a custom scoring metric. Reference minor allele presence in target genes was analyzed using RMA Hunter (19).

To check the possible presence of copy-number variants (CNVs), we analyzed the sequencing coverage across all targeted exons of interest. To this end, we calculated coverage for each interval using GATK, and then normalized the coverage matrix across samples and intervals. We then used z-score value of the normalized coverage to assess the statistical significance of the results.

Verification of the WES results and family analysis

Verification of the WES results in probands and subsequent family analyses were performed by PCR-direct sequencing. Specific primers were designed for verification of each case. The PCR products were purified with 5M NH4Ac and 96% ethanol and then with 70% ethanol, dried at 60°C, and dissolved in 10 µl of deionized water. After purification, the PCR products were sequenced using an ABI PRISM BigDyeTerminator 3.1 kit reagent (Applied Biosystems). Then, a capillary electrophoresis was performed in a GA3130×l Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Sequences were analyzed using the Sequence Scanner software (Applied Biosystems).

Analysis of the GCK promoter for c.-71G>C genetic variant

A single-base substitution c.-71G>C in the GCK promoter is known to be linked to MODY2 phenotype (20). However, WES did not allow for analysis of the GCK promoter for c.-71G>C. For this reason, the GCK promoter was analyzed for c.-71G>C genetic variant by PCR-direct sequencing as described above with the use of Hae III endonuclease and the following primers: F-5′-GCATGGCAGCTCTAATGACAGG-3′ and R-5′-CATCCTAGCCTGCTTCCCTGG-3′.

Results

Genetic variants causative of monogenic diabetes in Russian children with non-type 1 diabetes mellitus

Using whole-exome sequencing followed by PCR-direct sequencing, we identified the frequency and the spectrum of genetic variants causative of monogenic diabetes in 60 Russian children with non-type 1 diabetes mellitus. Genetic variants were screened for a total of 35 genes: 13 genes causative of MODY [HNF4A (MODY1), GCK (MODY2), HNF1A (MODY3), PDX1 (MODY4), HNF1B (MODY5), NEUROD1 (MODY6), KLF11 (MODY7), CEL (MODY8), PAX4 (MODY9), INS (MODY10), BLK (MODY11), ABCC8 (MODY12), and KCNJ11 (MODY13)] and 22 genes causative of transient or permanent neonatal diabetes, including the ones related to specific syndromes (EIF2AK3, RFX6, WFS1, ZFP57, FOXP3, AKT2, PPARG, APPL1, PTF1A, GATA4, GATA6, GLIS3, IER3IP1, LMNA, NEUROG3, PAX6, PLAGL1, SLC19A2, SLC2A2, SH2B1, SERPINB4, and MADD).

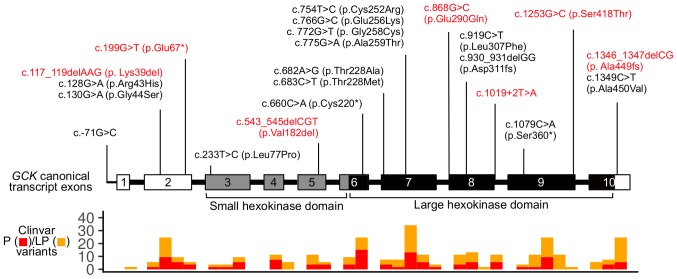

Overall, 33 out of 60 patients (55%) had genetic variants in the target genes (Table I; 21–40). For 12 patients, parents were available for genetic testing and origins of genetic variants were determined. In 11 cases, genetic variants had been inherited from the parents, and in one case, a de novo genetic variant was confirmed. Of 33 patients, 27 (81.8%) had genetic variants in MODY-related genes. The majority of these patients (19 out of 27) had genetic variants in GCK (MODY2). The spectrum of GCK genetic variants included 13 missense mutations, 3 nonsense mutations, 1 in-frame and 3 frameshift deletions, and 1 single-base substitution in the promoter. In two GCK mutation-positive patients, two genetic variants were present: Missense mutation along with a single-base substitution in the promoter (patient #27) and missense mutation along with a nonsense mutation (patient #78). The spectrum of the identified GCK genetic variants is shown in Fig. 1. Missense mutations in HNF1A (MODY3) were registered in two patients. The other MODY-related genetic variants included three cases of missense mutations: In PAX4 (MODY 9), in ABCC8 (MODY12), and in KCNJ11 (MODY 13).

Table I.

Genetic variants identified in Russian children with non-type 1 diabetes mellitus.

| Patient number | Gene | Nucleotide change (protein change) | Mutation type | Mutation origin | Pathogenicity according to ACMG | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 59 | GCK | c.772G>T (p.Gly258Cys) | Missense | Unknown | Likely pathogenic | (21) |

| 62 | GCK | c.930_931delGG (p.Asp311fs) | Frameshift | Unknown | Pathogenic | (22) |

| 83 | GСK | c.930_931delGG (p.Asp311fs) | Frameshift | Unknown | Pathogenic | (22) |

| 95 | GCK | c.130G>A (p.Gly44Ser) | Missense | Father | Likely pathogenic | (23) |

| 167 | GCK | c.128G>A (p.Arg43His) | Missense | Mother | Likely pathogenic | (24) |

| 197 | GCK | c.233T>C (p.Leu77Pro) | Missense | Father | Likely pathogenic | (25) |

| 426 | GCK | c.683C>T (p.Thr228Met) | Missense | Unknown | Likely pathogenic | (26) |

| 460 | GCK | c.682A>G (p.Thr228Ala) | Missense | Mother | Likely pathogenic | (21) |

| 580 | GCK | c.775G>A (p.Ala259Thr) | Missense | Unknown | Likely pathogenic | (27) |

| 663 | GCK | c.1079C>A (p.Ser360*) | Nonsense | Unknown | Pathogenic | (28) |

| 665 | GCK | c.660C>A (p.Cys220*) | Nonsense | Unknown | Pathogenic | (24) |

| 176 | GCK | c.1349C>T (p.Ala450Val) | Missense | Unknown | Likely pathogenic | (29) |

| 661 | GCK | c.1349C>T (p.Ala450Val) | Missense | Unknown | Likely pathogenic | (29) |

| 118 | GCK | c.117_119delAAG (p.Lys39del) | In-frame deletion | Unknown | Uncertain significance | Novel |

| 119 | GCK | c.1346_1347delCG (p.Ala449fs) | Frameshift | Unknown | Pathogenic | Novel |

| 434 | GCK | c.868G>C (p.Glu290Gln) | Missense | Mother | Uncertain significance | Novel |

| 578 | GCK | c.1253G>C (p.Ser418Thr) | Missense | Unknown | Pathogenic | Novel |

| 27 | GCK | c.754T>C (p.Cys252Arg) | Missense | Unknown | Likely pathogenic | (30) |

| c.-71G>C | Promoter | Unknown | Likely pathogenic | (20) | ||

| 78 | GCK | c.199G>T (p.Glu67*) | Nonsense | Mother | Pathogenic | Novel |

| c.766G>C (p.Glu256Lys) | Missense | Mother | Likely pathogenic | (31) | ||

| 153 | HNF1A | c.709A>G (p.Asn237Asp) | Missense | Unknown | Uncertain significance | (32) |

| 422 | HNF1A | c.485T>G (p.Leu162Arg) | Missense | Unknown | Uncertain significance | Novel |

| 215 | PAX4 | c.574C>A (p.Arg192Ser) | Missense | Unknown | Uncertain significance | (33) |

| 114 | ABCC8 | c.4139G>A (p.Arg1380His) | Missense | Unknown | Likely pathogenic | (34) |

| 134 | KCNJ11 | c.406C>A (p.Arg136Ser) | Missense | Unknown | Uncertain significance | (35) |

| 68 | GATA6 | c.1477C>T (p.Arg493*) | Nonsense | De novo | Pathogenic | (36) |

| 266 | WFS1 | c.2452C>T (p.Arg818Cys) | Missense | Mother | Likely benign | (37) |

| 408 | WFS1 | c.2327A>T (p.Glu776Val) | Missense | Mother | Likely benign | (38) |

| 133 | WFS1 | c.1124G>A (p.Arg375His) | Missense | Unknown | Uncertain significance | Novel |

| 411 | EIF2AK3 | c.1912C>T (p.Arg638*) | Nonsense | From | Pathogenic | Novel |

| EIF2AK3 | c.1912C>T (p.Arg638*) | Nonsense | parents | |||

| 432 | SLC19A2 | c.164delC (p.Pro55fs) | Frameshift | Mother | Pathogenic | Novel |

| SLC19A2 | c.161C>A (p.Thr54Asn) | Missense | Father | Uncertain significance | Novel | |

| 226 | GCK | c.543_545delCGT (p.Val182del) | In-frame deletion | Unknown | Uncertain significance | Novel |

| HNF1A | c.92G>A (p.Gly31Asp) | Missense | Unknown | Likely pathogenic | (39) | |

| 529 | BLK | c.939G>C (p.Glu313Asp) | Missense | Unknown | Uncertain significance | Novel |

| GCK | c.919C>T (p.Leu307Phe) | Missense | Unknown | Uncertain significance | Novel | |

| 662 | GCK | c.1019+2T>A | Splicing defect | Unknown | Pathogenic | Novel |

| BLK | c.1148G>A (p.Arg383Gln) | Missense | Unknown | Uncertain significance | Novel | |

| WFS1 | c.1957C>T (p.Arg653Cys) | Missense | Unknown | Likely pathogenic | (40) |

ACMG, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.

Figure 1.

The spectrum of genetic variants in the GCK gene identified in Russian children with non-type 1 diabetes mellitus. Exons and variants are numbered according to the canonical transcript (ENST00000403799.8). Novel variants are highlighted in red. The lower panel indicates the distribution of known pathogenic and likely pathogenic coding variants in GCK according to ClinVar (v. 2019-06-18). P, pathogenic; LP, likely pathogenic.

The presence of genetic variants in different target genes was detected in three patients. In one of them, a GCK in-frame deletion was accompanied by an HNF1A missense mutation (patient #226). In another one, two missense mutations were present: In GCK and in BLK (patient #529). In the third patient (#662), a splicing defect in GCK and missense mutations in BLK and WFS1 were present.

Genetic variants causative of non-MODY monogenic diabetes were found in 6 out of 33 mutation-positive patients (18.2%). These included a nonsense mutation in GATA6, three cases of missense mutations in WFS1, one case of a homozygous EIF2AK3 nonsense mutation (patient #411), and one case of missense mutation and a frameshift deletion present in SLC19A2 (c.164delC and c.161C>A) (patient #432). The EIF2AK3 nonsense mutations had been inherited from consanguineous parents who were heterozygous carriers of the same mutation. The SLC19A2 mutations also appeared to have been inherited from the parents: C.164delC from the mother and c.161C>A from the father, indicating that both SLC19A2 alleles in patient #432 were affected.

Considering that monogenic diabetes may be associated with deletions and duplications, we analyzed the possible presence of CNVs in the target genes. We found no evidence for CNVs in the target genes in either sample. However, it should be noted that the limitations of WES technology do not allow for confident detection of small-scale CNVs.

Relationship between genetic variants and diabetic phenotypes

We analyzed the relationship of the detected genetic variants to the patients' diabetic phenotypes. Among the 38 detected genetic variants, 23 had been previously reported as linked to monogenic diabetes and 15 were novel ones (Table I). According to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines (41), most of the detected genetic variants (18 previously reported and 6 novel ones) were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic and thus were considered as causative of the diabetic phenotypes in the studied patients. However, the relationship of the detected KCNJ11 missense mutation to the diabetic phenotype was not apparent, because earlier it had been shown to be associated with hyperinsulinism (35), which was not present in patient #134.

Three previously reported and 9 novel genetic variants were classified as those of uncertain significance, and two genetic variants were likely benign (Table I). These variants included 12 missense mutations; for them, we performed an additional in silico analysis using I-Mutant 2.0 (18) (Table II). In all but one case, the in silico modeling attested to a decrease of protein stability, thus suggesting the pathogenic effect of the checked genetic variants. Of special interest were two novel WFS1 genetic variants, initially classified as likely benign. Patient #266 inherited the genetic variant from a non-diabetic mother, while patient #408 inherited the genetic variant from a mother with diabetes. Homozygous mutations in WFS1 lead to the development of Wolfram syndrome, an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by a list of clinical signs including a bilateral progressive optic atrophy, deafness, and diabetes mellitus (42). Heterozygous carriers of WFS1 mutations have been reported to have risk of early-onset diabetes mellitus (43). The latter cannot be excluded in our patients. However, an intriguing point is that the WFS1 genetic variant in patient #408, who inherited it from a diabetic mother, appeared to not decrease the protein stability according to I-Mutant, which makes its pathogenicity questionable.

Table II.

In silico prediction of increase/decrease in the protein stability caused by missense mutations with uncertain significance and by benign missense mutations.

| Patient number | Gene | Genetic variant (amino acid change) | Pathogenicity according to ACMG | Protein stability predicted by I-Mutant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 434 | GCK | c.868G>C (p.Glu290Gln) | Uncertain significance | Decrease |

| 153 | HNF1A | c.709A>G (p.Asn237Asp) | Uncertain significance | Decrease |

| 422 | HNF1A | c.485T>G (p.Leu162Arg) | Uncertain significance | Decrease |

| 215 | PAX4 | c.574C>A (p.Arg192Ser) | Uncertain significance | Decrease |

| 134 | KCNJ11 | c.406C>A (p.Arg136Ser) | Uncertain significance | Decrease |

| 266 | WFS1 | c.2452C>T (p.Arg818Cys) | Likely benign | Decrease |

| 408 | WFS1 | c.2327A>T (p.Glu776Val) | Likely benign | Increase |

| 133 | WFS1 | c.1124G>A (p.Arg375His) | Uncertain significance | Decrease |

| 432 | SLC19A2 | c.161C>A (p.Thr54Asn) | Uncertain significance | Decrease |

| 529 | BLK | c.939G>C (p.Glu313Asp) | Uncertain significance | Decrease |

| GCK | c.919C>T (p.Leu307Phe) | Uncertain significance | Decrease | |

| 662 | BLK | c.1148G>A (p.Arg383Gln) | Uncertain significance | Decrease |

ASMG, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.

Clinical picture in patients with multiple genetic variants

Finally, we analyzed the clinical picture in patients with more than one genetic variant in one or different target genes (Table III). A simultaneous presence of two GCK genetic variants in patient #27 raised the question of their location in one or both alleles. The parents were not available for analysis. The clinical picture was mild and typical for MODY2. It contrasted with the severe one usually reported in patients with both GCK alleles affected (44,45), suggesting that, in patient #27, both genetic variants were present in the same allele and thus had no accumulative effect. In patient #78, who was also a carrier of two GCK genetic variants, the clinical picture was typical for MODY2. As both genetic variants were inherited from the mother, we concluded that only one allele was affected. Moreover, only nonsense mutation c.199G>T seemed to be clinically significant, because the resulting stop-codon terminates translation before the c.766G>C site. The clinical picture in patient #226, who had genetic variants in GCK and HNF1A, was more typical for MODY2 than for MODY3: He had mild fasting and postprandial hyperglycemia, had no glucosuria, and was successfully being treated by a diet. Patient #411 had a homozygous EIF2AK3 nonsense mutation, inherited from consanguineous parents and associated with Wolcott-Rallison syndrome, which, in turn, has been reported to be the most common genetic cause of permanent neonatal diabetes in consanguineous families (46). Patient #432 had two novel genetic variants affecting both SLC19A2 alleles. Homozygous mutations in SLC19A2 cause Rogers syndrome: Thiamine-responsive megaloblastic anaemia associated with diabetes mellitus and deafness (47). Among other clinical signs are congenital heart defects, retinal degeneration, ketonuria, dwarfism, and neurological symptomatology (42). Of note, patient #432 had only diabetes mellitus, retinal degeneration, ketonuria, and neurological symptomatology and thus did not manifest a typical clinical picture. Both patients #529 and #662 had typical clinical signs of GCK-MODY rather than BLK-MODY, suggesting an absence of strong accumulation of the pathogenic effect of the detected genetic variants.

Table III.

Clinical characteristics of the patients with multiple genetic variants in monogenic diabetes-related genes.

| Patient number | Gene Nucleotide change Amino acid change | Age at diagnosis months | Diabetic ketoacidosis | C-peptide ng/ml | HbA1C % | SDS BMI | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 | GCK | 3 | No | 0.7 | 6 | −0.63 | Diet |

| c.754T>C (p.Cys252Arg) | |||||||

| GCK | |||||||

| c.-71G>C | |||||||

| 78 | GCK | 39 | No | 0.63 | 6.4 | +0.83 | Diet |

| c.199G>T (p.Glu67*) | |||||||

| GCK | |||||||

| c.766G>C (p.Glu256Lys) | |||||||

| 226 | GCK | 36 | No | 1.1 | 6 | −1.69 | Diet |

| c.543_545delCGT (p.Val182del) | |||||||

| HNF1A | |||||||

| c.92G>A (p.Gly31Asp) | |||||||

| 411 | EIF2AK3 | 3 | Ketonuria | 0.2 | 9.2 | −0.72 | Insulin |

| c.1912C>T (p.Arg638*) | |||||||

| EIF2AK3 | |||||||

| c.1912C>T (p.Arg638*) | |||||||

| 432 | SLC19A2 | 48 | Ketonuria | 1.1 | 5.3 | −1.0 | Insulin for |

| c.164delC (p.Pro55fs) | a few days/ | ||||||

| SLC19A2 | diet | ||||||

| c.161C>A (p.Thr54Asn) | |||||||

| 529 | BLK | 10 | No | 0.43 | 6.7 | −0.46 | Diet |

| c.939G>C (p.Glu313Asp) | |||||||

| GCK | |||||||

| c.919C>T (p.Leu307Phe) | |||||||

| 662 | GCK | 22 | No | 1.1 | 6.82 | −1.32 | Diet |

| c.1019+2T>A | |||||||

| BLK | |||||||

| c.1148G>A (p.Arg383Gln) | |||||||

| WFS1 | |||||||

| c.1957C>T (p.Arg653Cys) |

SDS BMI reference range: −1.5/+1.5; SDS, standard deviation score.

Discussion

In 1974, Tattersall reported on three families suffering from mild non-insulin dependent diabetes with Mendelian dominant inheritance (48). The disease was diagnosed in children and young adults and was later defined as maturity-onset type diabetes of young people (MODY) (49). The discovery of mutations in the genes encoding HNF4A (50), HNF1A (51), HNF1B (52), IPF (PDX1) (53), and GCK (54,55) as the causes of MODY provided evidence for genetic heterogeneity of familial diabetes. To date, MODY-causing mutations are identified in a total of 13 genes, and mutations in more than 20 genes are known to be associated with neonatal hyperglycemia (56). Because of such a variety of genetic causes, many cases of monogenic diabetes remain without a genetic diagnosis, and its frequency remains underestimated.

The development of high throughput sequencing became a milestone in the search for diabetes-related mutations. Allowing for simultaneous testing of an unlimited number of genes (i.e. of all known genetic etiology in monogenic diabetes), the method increased the mutation detection rate significantly (57). In our study, we detected genetic variants causative of monogenic diabetes and hyperglycemia-related syndromes in 33 out of 60 children (55%) with non-type 1 diabetes mellitus. This frequency is considerably higher than that detected by Sanger sequencing, which is usually restricted to the analysis of several MODY-related genes and confirms approximately 15% of the cases tested for MODY (58). The higher mutation detection rate in our study is achieved by increasing the number of genes tested and a thorough clinical selection of patients with possible monogenic diabetes. In this regard, one more advantage of WES should be mentioned: DNA sequencing data may be easily stored for further analysis of newly discovered candidate genes.

Ethnic differences play an important role in determining the epidemiology of monogenic diabetes, especially of MODY. Large population studies in European Caucasians showed a general trend of increased HNF1A-MODY frequency in Northern Europe, while GCK-MODY is prevalent in Southern European populations (5). Here, we report GCK-MODY in 19 and HNF1A-MODY in only 2 out of 27 MODY-positive Russian patients. These mutation rates appeared to be closer to those in Southern European populations than to those in Northern Europe residents. Our finding may indicate the population-specific frequency MODY types in Russian patients. The recently shown high prevalence of GCK-MODY cases among Russian patients with diabetes in pregnancy supports this suggestion (59). However, it should be also considered that our study was performed on children who developed diabetes before the age of 18 years. In the previous observations, it was noticed that the relative proportion of GCK-MODY is higher in cases ascertained through pediatric clinics, in contrast to HNF1A-MODY, which predominates in cases from adult clinics (58,60). Thus, considering this information, our results are in good accordance with those reported in Spain, Italy, France, Germany, and the Czech Republic, where mostly pediatric cases were tested (25,61). The prevalence of GCK variants (57.6%) in our study suggests that genetic analysis in Russian children with suspected monogenic diabetes may start with testing for MODY2, which may not necessarily be performed by WES. However, other cases amount to 42.4% and are linked to 9 different genes, which attests to the efficiency of using WES for the search of genetic causes of diabetes in non-GCK-MODY cases.

Our results show that the spectrum of monogenic diabetes-related genetic variants in Russian children includes missense and nonsense mutations, in-frame and frameshift deletions, and a promoter mutation. Generally, these data do not contrast with results obtained in other populations, which also demonstrated a wide spectrum of mutations (62–64). Among genetic variants detected in our study, 60.5% had already been reported in diabetic patients and 39.5% were novel ones. On the one hand, these results point towards a significant recurrent variation within monogenic-diabetes-related genes. On the other hand, they suggest that, in spite of the multitude of monogenic diabetes studies, many variants still remain unidentified. Identification of novel genetic variants as well as accumulating data on previously known causes of monogenic diabetes is of high importance, both for fundamental understanding of the disease pathogenesis and for clinical practice.

Interpretation of genetic variants, especially novel ones, may be challenging. In this study, only 63.2% of the detected genetic variants (18 previously reported and 6 novel ones) were unambiguously considered as causative of the diabetes in the studied patients. The remaining 36.8% variants, including 9 novel ones, were initially classified as those of uncertain significance (n=12) or likely benign (n=2). Additional in silico predictions performed for missense mutations among these variants indicate that, with the exception of one variant, they all likely have an adverse effect on protein stability. Considering these results and the patients' phenotypes, the assumption that the abovementioned variants may be causative of monogenic diabetes can be made. Importantly, the detected genetic variants are absent in non-diabetic Russian population resided in Northwest Russia (65). However, to make a strong conclusion on the pathogenic effect of each novel variant, more data are required, including functional characterization and reports of a specific genetic variant in multiple patients with similar phenotypes. The latter highlights the importance of our results for future studies of monogenic diabetes-related genetic variants.

Noteworthy, our analysis of the clinical picture in the patients simultaneously having BLK+GCK (patient #529 and #662) and GCK+HNF1A (patient #226) genetic variants suggests no accumulation of adverse effect: All these patients had a typical MODY2 phenotype. The most plausible explanation for this is the specific age of development of different MODY types. Patients suffering from GCK-MODY have an impaired glucose metabolism since birth (66). In contrast, carriers of HNF1A genetic variants may develop diabetes by the age of 35 years or even by the age of 55 years, although most of them have diabetes before 25 years of age (67). In the study by López-Garrido et al (68), the co-inheritance of GCK and HNF1A genetic variants was reported in two patients and was associated with a typical MODY3 phenotype in an adult patient and only impaired fasting glucose in a younger patient with the same genotype. In addition, HNF1A genetic variant detected in patient #226 in this study (c.92G>A) was previously reported in a diabetic proband and his non-diabetic sister of 43 years of age (69). Similarly, affected carriers of BLK genetic variants usually develop diabetes at the middle age (70). Thus, it is likely that patients #529, #662, and #226, who were all involved in our study before the age of 4 years, have not developed the clinical picture of HNF1A-MODY and BLK-MODY yet. The possibility of a late manifestation of HNF1A-MODY and BLK-MODY in the children who already have GCK-MODY strongly suggests the necessity of their strict medical supervision in order to timely modify their therapy. Additional studies, including functional ones, on the pathogenicity of the novel BLK genetic variants detected in patients #529 and #662 will also facilitate the development of the most effective treatment strategies for them.

To summarize, our data show a high rate of genetic variants causative of monogenic diabetes in Russian children with non-type 1 diabetes mellitus. The use of a WES-based panel allowed us to identify a variety of previously known and novel genetic variants in MODY-related and unrelated genes, including multiple variants in a number of patients. The revealed variety is characterized by a prevalence of GCK genetic variants (MODY2) and also includes variants in HNF1A, PAX4, KCNJ11, BLK, ABCC8, GATA6, WFS1, EIF2AK3, and SLC19A2. These results, on the one hand, suggest that genetic analysis for monogenic diabetes in Russian children may start with testing for GCK variants, which may not necessarily be performed by WES. On the other hand, non-GCK variants are linked to 9 different genes, which attests to the efficiency of using WES while searching for genetic causes of diabetes in non-GCK-MODY cases. Notably, the detection of genetic variants in the genes linked to specific syndromes with recessive inheritance-WFS1, EIF2AK3, and SLC19A2-is essential for appropriate genetic counseling and family planning. Our study highlights the importance of using WES for monogenic diabetes testing and provides new information on the diabetes-related genetic variants in the Russian population.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs Ksenia Khudadyan (Logrus LLC) for helpful advice during the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

The current study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation within the framework of the Basic Research Program in 2019–2021 (grant no. AAAA-A19-119021290033-1), the alpha-Endo program, the Charities Aid Foundation Foundation (grant nos. 65/315 and 133/315), and the Russian Science Foundation (grant no. 14-50-00069).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

OSG, EAS, MET, OAE, EBB and VSB designed the study. OSG, EAS, MET, ASG, YAN, DEP, MAF, IVP, TEI, NYS, ESS, AVT, OVR, AMS, AAP, SGS, EVM, AVPK, LRL, LVD, LAZ, LVT, OSB, ENS and EBB recruited the patients and performed experimental procedures. YAB, AVP and RKS performed bioinformatic analysis. OSG, EAS, MET, OAE, AAP, TEI, LRL, EBB and VSB analyzed result and performed literature search. OAE wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of D.O. Ott Research Institute of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductology. All the patients/patients' representatives gave written informed consent to participate in the study. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

All the patients/patients' representatives gave written informed consent for publication of the study results.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Hattersley AT, Greeley SAW, Polak M, Rubio-Cabezas O, Njølstad PR, Mlynarski W, Castano L, Carlsson A, Raile K, Chi DV, et al. ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2018: The diagnosis and management of monogenic diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19(Suppl 27):S47–S63. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbetti F, D'Annunzio G. Genetic causes and treatment of neonatal diabetes and early childhood diabetes. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;32:575–591. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemelman MB, Letourneau L, Greeley SAW. Neonatal diabetes mellitus: An update on diagnosis and management. Clin Perinatol. 2018;45:41–59. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greeley SA, Naylor RN, Philipson LH, Bell GI. Neonatal diabetes: An expanding list of genes allows for improved diagnosis and treatment. Curr Diab Rep. 2011;11:519–532. doi: 10.1007/s11892-011-0234-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleinberger JW, Pollin TI. Undiagnosed MODY: Time for Action. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15:110. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0681-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(Suppl 1):S13–S27. doi: 10.2337/dc18-S002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, Garimella KV, Maguire JR, Hartl C, Philippakis AA, del Angel G, Rivas MA, Hanna M, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van der Auwera GA, Carneiro MO, Hartl C, Poplin R, Del Angel G, Levy-Moonshine A, Jordan T, Shakir K, Roazen D, Thibault J, et al. From FastQ data to high-confidence variant calls: The genome analysis toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr Protoc Bioinform. 2013;43:11.10.1–33. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.1000 Genomes Project Consortium. Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, Korbel JO, Marchini JL, McCarthy S, McVean GA, Abecasis GR. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, O'Donnell-Luria AH, Ware JS, Hill AJ, Cummings BB, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu W, O'Connor TD, Jun G, Kang HM, Abecasis G, Leal SM, Gabriel S, Rieder MJ, Altshuler D, Shendure J, et al. Analysis of 6,515 exomes reveals the recent origin of most human protein-coding variants. Nature. 2013;493:216–220. doi: 10.1038/nature11690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng PC, Henikoff S. Predicting deleterious amino acid substitutions. Genome Res. 2001;11:863–874. doi: 10.1101/gr.176601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi Y, Chan AP. PROVEAN web server: A tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:2745–2747. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X, Jian X, Boerwinkle E. dbNSFP v2.0: A database of human non-synonymous SNVs and their functional predictions and annotations. Hum Mutat. 2013;34:E2393–E2402. doi: 10.1002/humu.22376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desmet FO, Hamroun D, Lalande M, Collod-Béroud G, Claustres M, Béroud C. Human splicing finder: An online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao H, Yang Y, Lin H, Zhang X, Mort M, Cooper DN, Liu Y, Zhou Y. DDIG-in: Discriminating between disease-associated and neutral non-frameshifting micro-indels. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R23. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-3-r23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Capriotti E, Fariselli P, Casadio R. I-Mutant2.0: Predicting stability changes upon mutation from the protein sequence or structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W306–W310. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barbitoff YA, Bezdvornykh IV, Polev DE, Serebryakova EA, Glotov AS, Glotov OS, Predeus AV. Catching hidden variation: Systematic correction of reference minor allele annotation in clinical variant calling. Genet Med. 2018;20:360–364. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gasperíková D, Tribble ND, Staník J, Hucková M, Misovicová N, van de Bunt M, Valentínová L, Barrow BA, Barák L, Dobránsky R, et al. Identification of a novel beta-cell glucokinase (GCK) promoter mutation (−71G>C) that modulates GCK gene expression through loss of allele-specific Sp1 binding causing mild fasting hyperglycemia in humans. Diabetes. 2009;58:1929–1935. doi: 10.2337/db09-0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mantovani V, Salardi S, Cerreta V, Bastia D, Cenci M, Ragni L, Zucchini S, Parente R, Cicognani A. Identification of eight novel glucokinase mutations in Italian children with maturity-onset diabetes of the young. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:338. doi: 10.1002/humu.9179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bacon S, Kyithar MP, Schmid J, Rizvi SR, Bonner C, Graf R, Prehn JH, Byrne MM. Serum levels of pancreatic stone protein (PSP)/reg1A as an indicator of beta-cell apoptosis suggest an increased apoptosis rate in hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha (HNF1A-MODY) carriers from the third decade of life onward. BMC Endocr Disord. 2012;12:13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6823-12-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gragnoli C, Cockburn BN, Chiaramonte F, Gorini A, Marietti G, Marozzi G, Signorini AM. Early-onset Type II diabetes mellitus in Italian families due to mutations in the genes encoding hepatic nuclear factor 1 alpha and glucokinase. Diabetologia. 2001;44:1326–1329. doi: 10.1007/s001250100644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ziemssen F, Bellanné-Chantelot C, Osterhoff M, Schatz H, Pfeiffer AF. To: Lindner T, cockburn BN, Bell GI (1999) Molecular genetics of MODY in Germany. Diabetologia. 2002;42:121–123. doi: 10.1007/s00125-001-0738-9. Diabetologia 45: 286–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Estalella I, Rica I, Perez de Nanclares G, Bilbao JR, Vazquez JA, San Pedro JI, Busturia MA, Castaño L, Spanish MODY Group Mutations in GCK and HNF-1alpha explain the majority of cases with clinical diagnosis of MODY in Spain. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;67:538–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stoffel M, Froguel P, Takeda J, Zouali H, Vionnet N, Nishi S, Weber IT, Harrison RW, Pilkis SJ, Lesage S, et al. Human glucokinase gene: Isolation, characterization, and identification of two missense mutations linked to early-onset non-insulin-dependent (type 2) diabetes mellitus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7698–7702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hattersley AT, Beards F, Ballantyne E, Appleton M, Harvey R, Ellard S. Mutations in the glucokinase gene of the fetus result in reduced birth weight. Nat Genet. 1998;19:268–270. doi: 10.1038/953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Froguel P, Zouali H, Vionnet N, Velho G, Vaxillaire M, Sun F, Lesage S, Stoffel M, Takeda J, Passa P, et al. Familial hyperglycemia due to mutations in glucokinase. Definition of a subtype of diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:697–702. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199303113281005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borowiec M, Fendler W, Antosik K, Baranowska A, Gnys P, Zmyslowska A, Malecki M, Mlynarski W. Doubling the referral rate of monogenic diabetes through a nationwide information campaign-update on glucokinase gene mutations in a Polish cohort. Clin Genet. 2012;82:587–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pruhova S, Ek J, Lebl J, Sumnik Z, Saudek F, Andel M, Pedersen O, Hansen T. Genetic epidemiology of MODY in the Czech republic: New mutations in the MODY genes HNF-4alpha, GCK and HNF-1alpha. Diabetologia. 2003;46:291–295. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-1010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gidh-Jain M, Takeda J, Xu LZ, Lange AJ, Vionnet N, Stoffel M, Froguel P, Velho G, Sun F, Cohen D, et al. Glucokinase mutations associated with non-insulin-dependent (type 2) diabetes mellitus have decreased enzymatic activity: Implications for structure/function relationships. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1932–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colclough K, Bellanne-Chantelot C, Saint-Martin C, Flanagan SE, Ellard S. Mutations in the genes encoding the transcription factors hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha and 4 alpha in maturity-onset diabetes of the young and hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Hum Mutat. 2013;34:669–685. doi: 10.1002/humu.22279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Plengvidhya N, Kooptiwut S, Songtawee N, Doi A, Furuta H, Nishi M, Nanjo K, Tantibhedhyangkul W, Boonyasrisawat W, Yenchitsomanus PT, et al. PAX4 mutations in Thais with maturity onset diabetes of the young. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2821–2826. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flanagan SE, Patch AM, Mackay DJ, Edghill EL, Gloyn AL, Robinson D, Shield JP, Temple K, Ellard S, Hattersley AT. Mutations in ATP-sensitive K+ channel genes cause transient neonatal diabetes and permanent diabetes in childhood or adulthood. Diabetes. 2007;56:1930–1937. doi: 10.2337/db07-0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohnike K, Wieland I, Barthlen W, Vogelgesang S, Empting S, Mohnike W, Meissner T, Zenker M. Clinical and genetic evaluation of patients with KATP channel mutations from the German registry for congenital hyperinsulinism. Horm Res Paediatr. 2014;81:156–168. doi: 10.1159/000356905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki S, Nakao A, Sarhat AR, Furuya A, Matsuo K, Tanahashi Y, Kajino H, Azuma H. A case of pancreatic agenesis and congenital heart defects with a novel GATA6 nonsense mutation: Evidence of haploinsufficiency due to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A:476–479. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gomez-Zaera M, Strom T, Meitinger T, Nunes V. Wolframin mutations in Spanish families with Wolfram syndrome. Meeting abstract. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:1673. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith CJ, Crock PA, King BR, Meldrum CJ, Scott RJ. Phenotype-genotype correlations in a series of wolfram syndrome families. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2003–2009. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.8.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chèvre JC, Hani EH, Boutin P, Vaxillaire M, Blanché H, Vionnet N, Pardini VC, Timsit J, Larger E, Charpentier G, et al. Mutation screening in 18 Caucasian families suggest the existence of other MODY genes. Diabetologia. 1998;41:1017–1023. doi: 10.1007/s001250051025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Awata T, Inoue K, Kurihara S, Ohkubo T, Inoue I, Abe T, Takino H, Kanazawa Y, Katayama S. Missense variations of the gene responsible for Wolfram syndrome (WFS1/wolframin) in Japanese: Possible contribution of the Arg456His mutation to type 1 diabetes as a nonautoimmune genetic basis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;268:612–616. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaw-Smith C, Flanagan SE, Patch AM, Grulich-Henn J, Habeb AM, Hussain K, Pomahacova R, Matyka K, Abdullah M, Hattersley AT, Ellard S. Recessive SLC19A2 mutations are a cause of neonatal diabetes mellitus in thiamine-responsive megaloblastic anaemia. Pediatr Diabetes. 2012;13:314–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2012.00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fraser FC, Gunn T. Diabetes mellitus, diabetes insipidus, and optic atrophy. An autosomal recessive syndrome? J Med Genet. 1977;14:190–193. doi: 10.1136/jmg.14.3.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bennett K, James C, Mutair A, Al-Shaikh H, Sinani A, Hussain K. Four novel cases of permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus caused by homozygous mutations in the glucokinase gene. Pediatr Diabetes. 2011;12:P192–P196. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2010.00683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raimondo A, Chakera AJ, Thomsen SK, Colclough K, Barrett A, De Franco E, Chatelas A, Demirbilek H, Akcay T, Alawneh H, et al. Phenotypic severity of homozygous GCK mutations causing neonatal or childhood-onset diabetes is primarily mediated through effects on protein stability. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:6432–6440. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rubio-Cabezas O, Patch AM, Minton JA, Flanagan SE, Edghill EL, Hussain K, Balafrej A, Deeb A, Buchanan CR, Jefferson IG, et al. Wolcott-Rallison syndrome is the most common genetic cause of permanent neonatal diabetes in consanguineous families. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:4162–4170. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Labay V, Raz T, Baron D, Mandel H, Williams H, Barrett T, Szargel R, McDonald L, Shalata A, Nosaka K, et al. Mutations in SLC19A2 cause thiamine-responsive megaloblastic anaemia associated with diabetes mellitus and deafness. Nat Genet. 1999;22:300–304. doi: 10.1038/10372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tattersall RB. Mild familial diabetes with dominant inheritance. Q J Med. 1974;43:339–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tattersall RB, Fajans SS. A difference between the inheritance of classical juvenile-onset and maturity-onset type diabetes of young people. Diabetes. 1975;24:44–53. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.24.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamagata K, Furuta H, Oda N, Kaisaki PJ, Menzel S, Cox NJ, Fajans SS, Signorini S, Stoffel M, Bell GI. Mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-4alpha gene in maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY1) Nature. 1996;384:458–460. doi: 10.1038/384458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamagata K, Oda N, Kaisaki PJ, Menzel S, Furuta H, Vaxillaire M, Southam L, Cox RD, Lathrop GM, Boriraj VV, et al. Mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1alpha gene in maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY3) Nature. 1996;384:455–458. doi: 10.1038/384458a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horikawa Y, Iwasaki N, Hara M, Furuta H, Hinokio Y, Cockburn BN, Lindner T, Yamagata K, Ogata M, Tomonaga O, et al. Mutation in hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 beta gene (TCF2) associated with MODY. Nat Genet. 1997;17:384–385. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stoffers DA, Ferrer J, Clarke WL, Habener JF. Early-onset type-II diabetes mellitus (MODY4) linked to IPF1. Nat Genet. 1997;17:138–139. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Froguel P, Vaxillaire M, Sun F, Velho G, Zouali H, Butel MO, Lesage S, Vionnet N, Clément K, Fougerousse F, et al. Close linkage of glucokinase locus on chromosome 7p to early-onset non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Nature. 1992;356:162–164. doi: 10.1038/356162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hattersley AT, Turner RC, Permutt MA, Patel P, Tanizawa Y, Chiu KC, O'Rahilly S, Watkins PJ, Wainscoat JS. Linkage of type 2 diabetes to the glucokinase gene. Lancet. 1992;339:1307–1310. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91958-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Timsit J, Saint-Martin C, Dubois-Laforgue D, Bellanné-Chantelot C. Searching for Maturity-Onset diabetes of the Young (MODY): When and What for? Can J Diabetes. 2016;40:455–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ellard S, Lango Allen H, De Franco E, Flanagan SE, Hysenaj G, Colclough K, Houghton JA, Shepherd M, Hattersley AT, Weedon MN, Caswell R. Improved genetic testing for monogenic diabetes using targeted next-generation sequencing. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1958–1963. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2962-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shields BM, Hicks S, Shepherd MH, Colclough K, Hattersley AT, Ellard S. Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY): How many cases are we missing? Diabetologia. 2010;53:2504–2508. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1799-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zubkova N, Burumkulova F, Plechanova M, Petrukhin V, Petrov V, Vasilyev E, Panov A, Sorkina E, Ulyatovskaya V, Makretskaya N, Tiulpakov A. High frequency of pathogenic and rare sequence variants in diabetes-related genes among Russian patients with diabetes in pregnancy. Acta Diabetol. 2019;56:413–420. doi: 10.1007/s00592-018-01282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lorini R, Klersy C, d'Annunzio G, Massa O, Minuto N, Iafusco D, Bellannè-Chantelot C, Frongia AP, Toni S, Meschi F, et al. Maturity-onset diabetes of the young in children with incidental hyperglycemia: A multicenter Italian study of 172 families. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1864–1866. doi: 10.2337/dc08-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schober E, Rami B, Grabert M, Thon A, Kapellen T, Reinehr T, Holl RW. Phenotypical aspects of maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY diabetes) in comparison with Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in children and adolescents: Experience from a large multicentre database. Diabet Med. 2009;26:466–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ağladıoğlu SY, Aycan Z, Çetinkaya S, Baş VN, Önder A, Peltek Kendirci HN, Doğan H, Ceylaner S. Maturity onset diabetes of youth (MODY) in Turkish children: Sequence analysis of 11 causative genes by next generation sequencing. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2016;29:487–496. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2015-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Globa E, Zelinska N, Elblova L, Dusatkova P, Cinek O, Lebl J, Colclough K, Ellard S, Pruhova S. MODY in Ukraine: Genes, clinical phenotypes and treatment. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2017;30:1095–1103. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2017-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johansson BB, Irgens HU, Molnes J, Sztromwasser P, Aukrust I, Juliusson PB, Søvik O, Levy S, Skrivarhaug T, Joner G, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing reveals MODY in up to 6.5% of antibody-negative diabetes cases listed in the Norwegian Childhood Diabetes Registry. Diabetologia. 2017;60:625–635. doi: 10.1007/s00125-016-4167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barbitoff YA, Skitchenko RK, Poleshchuk OI, Shikov AE, Serebryakova EA, Nasykhova YA, Polev DE, Shuvalova AR, Shcherbakova IV, Fedyakov MA, et al. Whole-exome sequencing provides insights into monogenic disease prevalence in Northwest Russia. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019 Sep 3;:e964. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.964. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.964 (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chakera AJ, Steele AM, Gloyn AL, Shepherd MH, Shields B, Ellard S, Hattersley AT. Recognition and management of individuals with hyperglycemia because of a heterozygous glucokinase mutation. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1383–1392. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Murphy R, Ellard S, Hattersley AT. Clinical implications of a molecular genetic classification of monogenic beta-cell diabetes. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008;4:200–213. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.López-Garrido MP, Herranz-Antolín S, Alija-Merillas MJ, Giralt P, Escribano J. Co-inheritance of HNF1a and GCK mutations in a family with maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY): Implications for genetic testing. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013;79:342–347. doi: 10.1111/cen.12050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thanabalasingham G, Pal A, Selwood MP, Dudley C, Fisher K, Bingley PJ, Ellard S, Farmer AJ, McCarthy MI, Owen KR. Systematic assessment of etiology in adults with a clinical diagnosis of young-onset type 2 diabetes is a successful strategy for identifying maturity-onset diabetes of the young. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1206–1212. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Borowiec M, Liew CW, Thompson R, Boonyasrisawat W, Hu J, Mlynarski WM, El Khattabi I, Kim SH, Marselli L, Rich SS, et al. Mutations at the BLK locus linked to maturity onset diabetes of the young and beta-cell dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14460–14465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906474106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.