Abstract

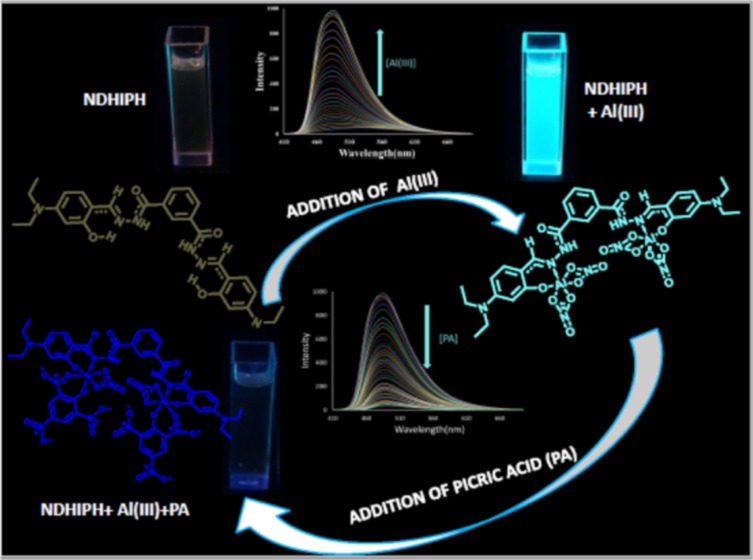

A hydrazone-based N′1,N′3-bis((E)-4-(diethylamino)-2–hydroxybenzylidene)isophthalohydrazide (NDHIPH), has been synthesized, characterized, and assessed for its highly selective and sensitive (limit of detection, 2.53 nM) response toward Al(III) via fluorescence enhancement in 95% aqueous medium. All experimental results of analytical studies are in good consonance with the theoretical studies performed. Further, this NDHIPH-Al(III) ensemble is used for selective and sensitive (12.15 nM) detection of explosive picric acid (PA) via fluorescence quenching. This reversible behavior of NDHIPH toward Al(III) and PA is used for the creation of a molecular logic gate.

Introduction

Fluorescent sensors have attracted extensive inquisitiveness of researchers in the past few decades owing to their operational simplicity, extreme sensitivity of emission intensities and/or wavelengths to subtle environmental changes, and direct visual perception selectivity.1 Out of various metal ions, aluminum, being the most abundant one in the earth’s crust, finds wide applications in industry and in our daily lives, such as in food additives, packing materials, water treatment, paper making, production of light alloys, and some medicines.2 Studies indicate that excess accumulation of Al(III) can cause serious damage to the human nervous system, which leads to diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases.3 Toxicity due to Al(III) is also accountable for bone softening, impaired lung function, fibrosis, chronic renal failure, etc.3 It is also found to be detrimental for aquatic life and agricultural production by increasing the acidity of the soil.4 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends an average weekly human body dietary intake of Al(III) of around 7 mg/kg of body weight.5 Therefore, detection of Al(III) is crucial in controlling its concentration levels both in the environment and biological systems. Unfortunately, determination of Al(III) is much more difficult in comparison to the determination of other biologically important cations, such as Cu(II), Pb(II), Hg(II), Zn(II), etc., due to its properties of strong hydration and poor coordination. Although a significant number of chemosensors are known6 for sensing Al(III), they are relatively fewer in number in comparison to those for sensing other metal ions. Hitherto, many approaches such as atomic absorption spectroscopy, graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry, inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry, mass spectrometry, electrochemistry, and NMR technology have been used for Al(III) detection.7 However, these methods have limitations, as they require sophisticated instrumentation and are time-consuming. In contrast, optical sensors have gathered interest for providing quick, low-cost, nondestructive, and highly selective results. Hence, there is an ample need to design and synthesize new chromo-fluorogenic Al(III) sensors through simple synthetic mechanisms that possess a low detection limit and high selectivity and sensitivity in aqueous medium.

Research interests of our lab involve recognition of various biologically important ions through usage of aromatic platform based chemosensors,8 which have imine/hydroxyl, urea/thiourea, thiosemicarbazide, and hydrazone functional groups acting as receptor-cum-transducers. We have already reported9 three positional isomers of a Schiff base (DBIH1–DBIH3) for highly selective and sensitive Al(III) detection (respective limit of detection (LOD): 8.91, 14.1, and 19.95 nM) in 70% aqueous medium. Presently, we report another highly sensitive (LOD 2.53 nM) and selective system, NDHIPH, for Al(III) detection. NDHIPH possesses a coordination environment of −CONH, C=N, and −OH groups (Scheme 1). Being a hard acid, Al(III) prefers systems containing hard base sites such as O and N; hence, NDHIPH provides an ideal framework for the detection of Al(III) in 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) buffer (pH 7.4, containing 5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a cosolvent). Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to check the geometrical and electronic structural features of NDHIPH and its Al(III) complex. The detection limit achieved for NDHIPH is 2.53 nM, comparable to the concentration range of Al(III) ions found in many chemical and biological systems. Furthermore, NDHIPH finds application in the form of “paper strips” that facilitate instant selective detection of Al(III) in the presence of other interfering metal ions.

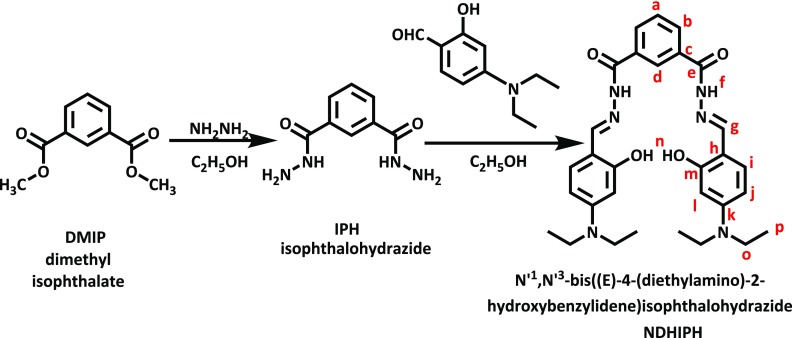

Scheme 1. Synthesis of the Sensor (NDHIPH).

Results and Discussion

Syntheses and General Characterization

N′1,N′3-bis((E)-4–(diethylamino)-2-hydroxybenzylidene)isophthalohydrazide (NDHIPH) was synthesized by a Schiff base condensation reaction of isophthalohydrazide and (IPH)4-(diethylamino)-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde (Scheme 1) and characterized by techniques such as 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy, distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer (DEPT), correlation spectroscopy (COSY), Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), and CHN analysis (Figures S1–S7). In 1H NMR spectra of NDHIPH, the signal of the −CH2 group is merged with the residual peak of moisture, which is established with techniques such as 13C NMR, DEPT, and COSY. The presence of a peak at δ 44.2 in 13C and DEPT spectra confirms the presence of the −CH2 group. Further, the COSY spectrum also showed the interaction of methyl protons at δ 1.11 (position p) with the methylene proton at δ 3.38 (position o).

Colorimetric, Chromogenic, and Fluorogenic Spectral Responses of NDHIPH

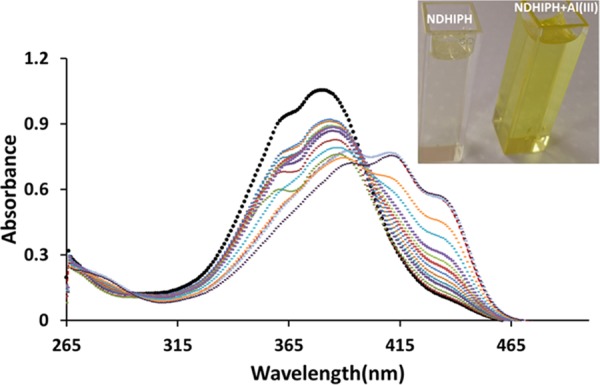

NDHIPH exhibits two absorption bands centered at 269 nm (ε = 2.03 × 104 M–1 cm–1) and 383 nm (ε = 9.17 × 104 M–1 cm–1) in HEPES buffer (pH 7.4, containing 5% DMSO as a cosolvent) (Figure S8). These bands from 320 to 460 nm indicate internal charge transfer between the imine and hydroxyl groups.10 On addition of Al(III) (inset, Figure 1) to NDHIPH, the absorption band at 269 nm showed a slight increase in intensity, whereas the band at 383 nm showed a bathochromic shift to 391 nm (ε = 7.54 × 104 M–1 cm–1) along with the formation of two new bands at λmax of 411 nm (ε = 8.00 × 104 M–1 cm–1) and 436 nm (ε = 5.69 × 104 M–1 cm–1). The color change from colorless to bright yellow (inset, Figure 1) corroborates these shifts in absorption bands. The stoichiometry of the Al(III) complex of NDHIPH is checked using a Job’s plot, which turns out to be 1:2 (Figure S9).

Figure 1.

(a) Changes in absorption spectra of NDHIPH in DMSO:HEPES (5:95) (10 μM) upon gradual addition of Al(III). Inset: Color change in the sensor solution with Al(III).

Further, NDHIPH was investigated for its fluorogenic properties in HEPES buffer (pH 7.4, containing 5% DMSO as a cosolvent) (Figure 2). It exhibits a very weak fluorescence (Φ = 0.11) at λem of 529 nm (excitation at 383 nm), which may be due to the excited-state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT) phenomenon, well known in the case of Schiff’s bases.10

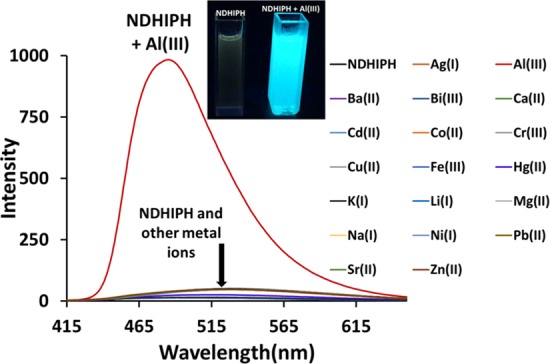

Figure 2.

Changes in fluorescence spectra of NDHIPH in DMSO:HEPES (5:95) (1 μM) upon the addition of 10 equiv of various metal nitrates. Inset: Color changes in the sensor solution with Al(III) under a UV lamp.

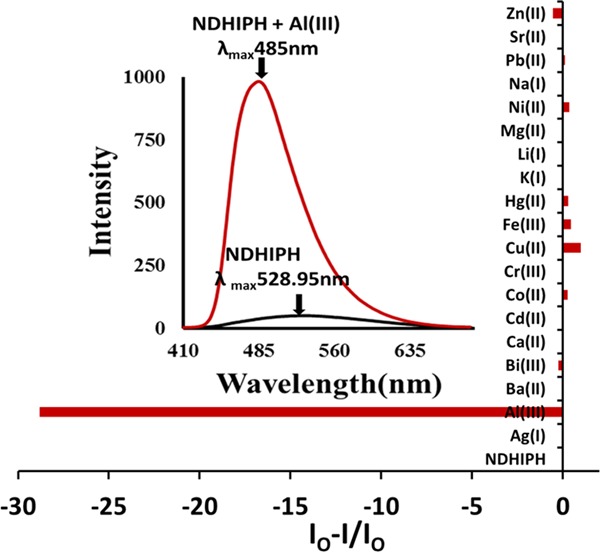

This type of phenomenon generally involves the conversion of a basal enol form to an excited enol form as a result of the transfer of a hydroxy proton to the nitrogen atom of the imine group, which ultimately leads to the formation of a cis-keto tautomer (also a π–π* state or keto*). This cis-keto form may further undergo relaxation toward a ground-state trans-keto (or keto) isomer form (photochromic tautomer) along with a large Stokes shift of 145 nm (from 383 to 528 nm) after photoinduced proton transfer.10 When treated with Al(III), NDHIPH caused a significant fluorescence enhancement along with a hypsochromic shift from 529 to 485 nm (λex 383 nm) (Figure 3). This remarkable fluorescence enhancement may be attributed to the metal coordination of NDHIPH through the lone pair of electrons of nitrogens of imine and oxygens of hydroxyl groups, which gives rise to a tetradentate N2O2 donor site for the generation of a stable chelated system with high rigidity and results in an efficient chelation-enhanced fluorescence. Further, the selectivity of NDHIPH can be checked by screening it with various metal ions under study. The addition of Li(I), Na(I), K(I), Ag(I), Mg(II), Ca(II), Cd(II), Ba(II), and Sr(II) showed no significant change, whereas Bi(III) and Zn(II) showed a slight fluorescence enhancement and Co(II), Cr(III), Cu(II), Fe(III), Hg(II), Ni(II), and Pb(II) caused quenching to various extents (Figure 3).11,12 Sensor NDHIPH showed no significant change in selectivity when different counteranions were investigated under the same conditions by using Al2(SO4)3 and AlCl3 (Figure S10). The reversibility of the recognition process of NDHIPH toward Al(III) was studied by the alternating addition of Al(III) and a strong chelating agent such as the disodium salt of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Figure S11).

Figure 3.

Variation in fluorescence intensity of NDHIPH in DMSO:HEPES (5:95) (1 μM) with the addition of metal nitrates.

Further, the 1:2 stoichiometry (Figure S12) of NDHIPH–Al(III) was checked through fluorescence using a Job’s plot. This stoichiometry was also supported by a peak in the mass spectrum at m/z 798.1951, assignable to [(NDHIPH-Al(III)-NO2)•]+ = [(C30H34Al2N10O16– NO2)•] = [(C30H34Al2N9O14)•]+. The simulated mass spectrum agrees well with that of the experimental one (Figure S20). The binding constant of NDHIPH with Al(III), 4.25 × 1012 M–2 (Figure S13), was determined through titration of NDHIPH with Al(III), employing a modified form of the Benesi–Hildebrand plot (ref (3)a in the Supporting Information). Selectivity is another important criterion of an efficient fluorescent sensor, which is checked for NDHIPH by titrating it with Al(III) in the presence of other metal ions (Figure S14), which revealed that NDHIPH can detect Al(III) even in the presence of other competitive metal ions. For this experiment, NDHIPH was treated with 10 equiv of Al(III) in the presence of 100 equiv of other metal ions. There was a slight interference in the case of Cu(II) and Fe(III), which showed some quenching but enhancement was clearly detectable, whereas other metal ions showed no significant interference with Al(III). The quantum yields of NDHIPH and its Al(III) complex were determined to be 0.11 and 0.78 using 9,10-diphenylanthracene as the standard. The limit of detection13 (LOD) of NDHIPH for Al(III) (Figure S15) was calculated from fluorescence titrations to be 2.53 × 10–9 M, which is quite lower than the limit specified by the WHO. Further, for realistic applications, the sensitivity of NDHIPH was also checked toward variations in the pH by performing fluorescence titration by adjusting the pH with HCl and NaOH in the presence and absence of Al(III) (Figure S16). An analysis of pH-induced changes in fluorescence at λmax = 485 nm showed that NDHIPH remains unaffected over the pH range of 2.24–10.09. For NDHIPH-Al(III), a large increase in intensity is observed at pH 4.05 and the intensity remains almost constant till pH 11.03, which is a good range for analysis in a biological medium. This working range for NDHIPH and its Al(III) complex may be attributed to the decomposition caused at a high pH and protonation of the phenolic hydroxyl groups at a low pH.

Sensing Mechanism

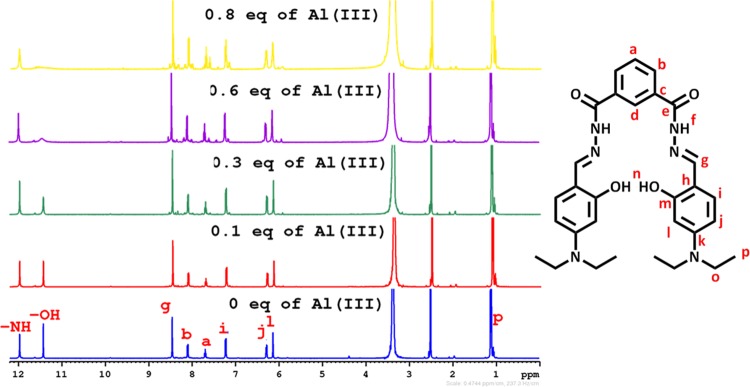

To further dig into the NDHIPH-Al(III) interactions, NMR titrations were performed in DMSO-d6, (Figure 4). With the addition of Al(III) to the solution of NDHIPH, the peak for −OH at δ 11.42 almost disappears completely along with a slight downward shift of the peak for −NH owing to deprotonation of former groups and complexation by imine and −OH groups. The signals of aromatic protons at positions l, i, and j (in the vicinity of the −OH group) and protons of −CH=N groups showed downward shifts, whereas aromatic protons at positions “a” and “b” remain virtually unperturbed (Figure S17 and Table S1). The formation of the NDHIPH-Al(III) complex was further confirmed by isolating the solid complex formed by reacting NDHIPH with Al(NO3)3·9H2O in ethanol and characterizing it by NMR, IR, and mass spectroscopy (Figures S18–S20).

Figure 4.

Changes in 1H NMR of NDHIPH (5 mM) upon the addition of Al(III) in DMSO-d6.

Response of the NDHIPH-Al(III) Ensemble toward Organic Nitro Derivatives

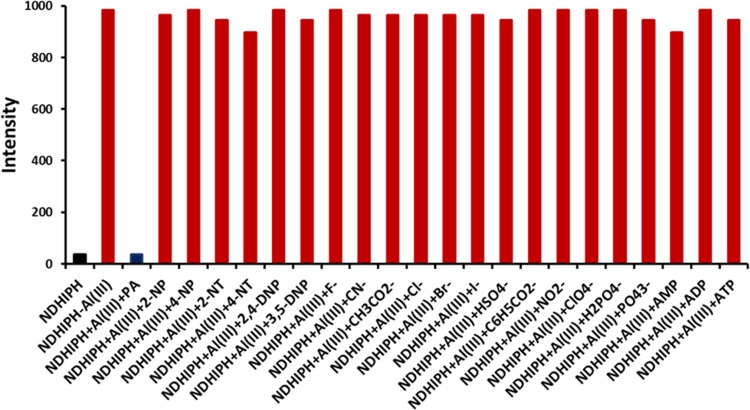

The NDHIPH-Al(III) ensemble showed another useful property in the form of a selective and sensitive probe for the detection of organic nitro-based explosives. When titrated with various nitro derivatives, the ensemble showed a highly selective response only toward picric acid (PA). With the addition of PA, the absorption bands of the ensemble metalloligand NDHIPH-Al(III) at λmax of 411 and 436 nm showed a large increase in intensity (Figure S21a), whereas it showed significant quenching of the emission band at 485 nm (Figure S21b). To examine the selectivity of NDHIPH-Al(III) for PA, its fluorescence response was investigated toward different analytes, such as picric acid (PA), 2-nitrophenol (2-NP), 4-nitrophenol (4-NP), 2-nitrotoluene (2-NT), 4-nitrotoluene (4-NT), 2,4-dinitrophenol (2,4-DNP), 3,5-dinitrophenol (3,5-DNP), Cl–, Br–, I–, F–, CN–, ClO4–, NO2–, CH3CO2–, C6H5CO2–, HSO4– H2PO4–, PO43–, AMP, ADP, and ATP (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Competitive selectivity of NDHIPH-Al(III) (1μM) toward picric acid (PA) in the presence of various anions under study.

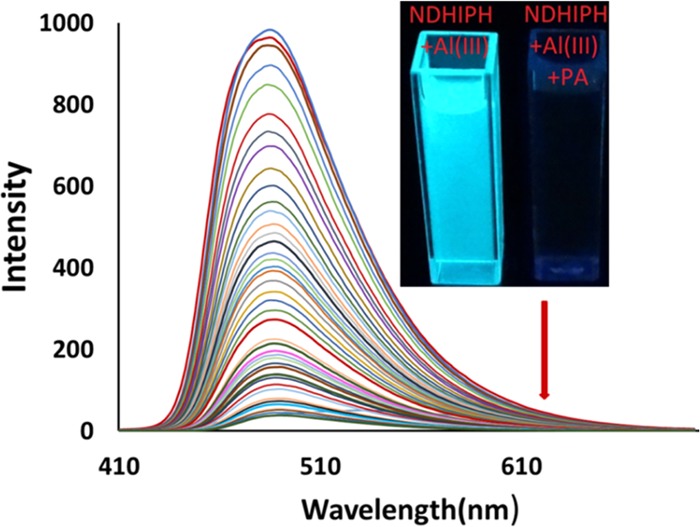

Interestingly, only the addition of PA instantly causes significant fluorescence quenching, whereas no significant change in fluorescence intensity is observed in other cases. A fluorescence titration of ML with PA (ϕ = 0.040) (Figure 6) caused quenching gradually up to the extent of 96%, which is calculated using the formula: [Io – I]/Io × 100, where Io is the original fluorescence intensity and I is the fluorescence intensity of ML.

Figure 6.

Changes in the fluorescence spectra of ML in DMSO:HEPES (5:95) (5 μM) upon gradual addition of picric acid (0–50 μM). Inset: Color changes in ML solution with PA under a UV lamp.

These changes in fluorescence intensity were consistent with the disappearance of the fluorescent green color (under a UV lamp, Figure 6, inset, right). Further, this fluorescence quenching data were analyzed using a Stern–Völmer plot, which showed a linear dependence of the fluorescence intensity ratio (I/Io) on the concentration of Al(III) ions added (Figure S22). The value of Ksv for the complex of PA and NDHIPH-Al(III) was calculated to be 1.165 × 106 M–1. The 1:2 stoichiometry of binding between the NDHIPH-Al(III) and PA was calculated using a Job’s plot (Figure S23), which was further confirmed by the appearance of a peak in high-resolution ESI-HRMS at m/z 1130.1980 assignable to [(NDHIPH-Al(III) + PA-NO2)•]+ = [(C42H38Al2N14O24–NO2)•]+ = [(C42H38Al2N13O22)•+] (calc 1130.1980) (Figure S24). This interaction of the NDHIPH-Al(III) complex with PA was also studied by 1H NMR titrations (Figure S25), although no significant chemical shift with addition of picric acid was observed except for an increase in the intensity of the peak at 8.6 ppm for the aromatic protons of picric acid. The detection limit of the NDHIPH-Al(III) ensemble toward PA was calculated to be 12.15 nM (Figure S26). Hence, the mechanism proposed for the quenching of picric acid involved replacement of one NO3 ligand of Al in NDHIPH-AL with picric acid in its phenoxide anion form. In Table S2, we have compared the outcomes of NDHIPH with the already reported literature values.

Computational Analysis of NDHIPH, NDHIPH-Al(III) Complex, and NDHIPH-Al(III) Complex with Picric Acid

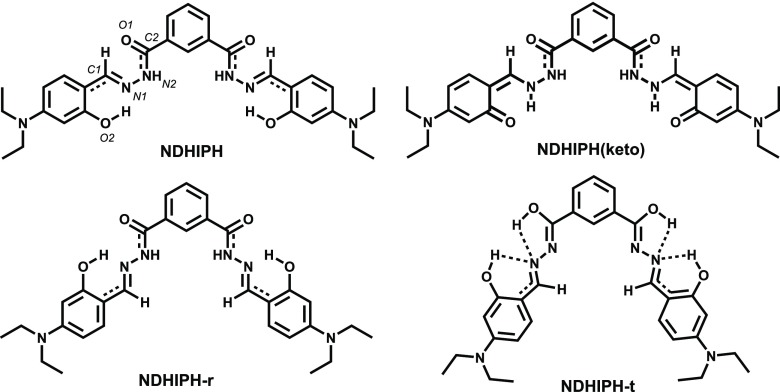

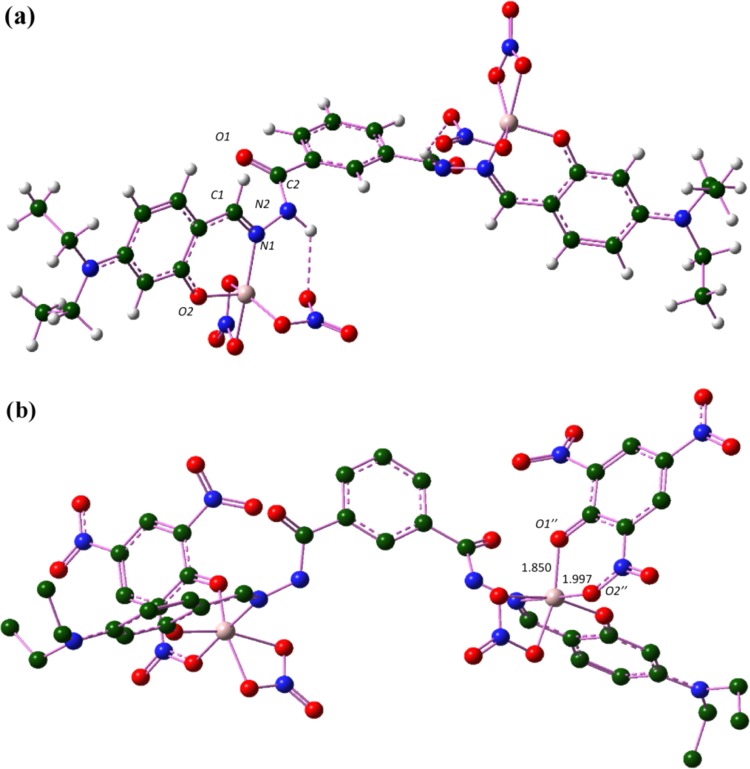

To identify the geometrical and electronic structural features of NDHIPH and its possible Al(III) complexes, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the Gaussian 09 package.14 The results show that there can be three geometrical isomers of NDHIPH (Figures 7 and S27), with comparable energies (Table S3). NDHIPH exists in the hydrazide form, NDHIPH-r is its rotamer, and NDHIPH-t is an azine tautomer of NDHIPH-r.15 The rotamer is more stable by only 0.19 kcal/mol, whereas the tautomer is less stable by only 0.82 kcal/mol. NDHIPH and its rotamer are characterized by two intramolecular hydrogen bonds each, and the tautomer is characterized by two bifurcated hydrogen bonds. NDHIPH possesses two benzylidene groups coplanar with the attached hydrazide moieties. However, the overall geometry is nonplanar. Stability is attained due to the E/E configuration along C1–N1–N2–C2 bonds, O2–H···1 hydrogen bonding, and C1–H···O type of weak hydrogen bonding interaction. In the ground state, NDHIPH exists in the enol form. Thus, a time-dependent DFT calculation (TDDFT) was performed to identify the intramolecular proton transfer through the excited-state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT) mechanism. The obtained geometry, NDHIPH(keto), in the excited state possessed a cis-keto configuration and was characterized by a ππ* transition state, which attained stability due to O2···H–N1 intramolecular hydrogen bonding (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Proposed isomers of NDHIPH, optimized at the B3LYP/6-311 + G(d,p) level of theory. NDHIPH(keto) was obtained using the TDDFT excited-state calculation with the same basis set.

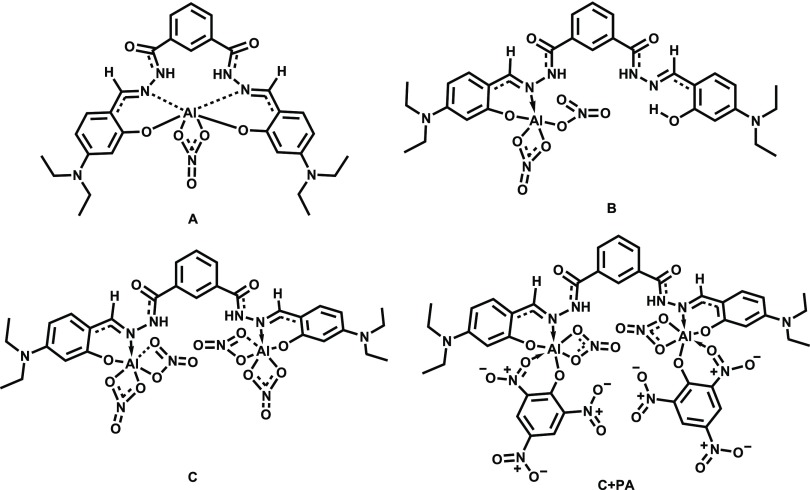

Complexation of NDHIPH with Al(III) can result in three probable complexes, namely, A, B, and C (Figure 8), depending on the stoichiometry of the reaction (Figure S26). When an equimolar amount of Al(NO3)3 is considered, two complexes A and B were possible. Quantum chemical analysis indicates that the formation of A demands 15.20 kcal/mol (endergonic), whereas the formation of B is exergonic by 19.32 kcal/mol. Two equivalents of Al(NO3)3 leads to the formation of complex C, releasing 35.25 kcal/mol. In principle, NDHIPH-t can also yield two metal complexes, B′ with the loss of two units of HNO3 and complex C′ with the loss of four units of HNO3. Formation of B′ and C′ is exergonic by 4.15 and 10.31 kcal/mol, respectively (Figure S29). The three-dimensional (3D) structures of all complexes are provided in Figure S30. The energetics of the complexation reaction indicates that C is the most stable complex (Figure S28). The optimized 3D structure of C (Figure 9) shows that the bond length between Al and O2 is 1.777 Å and the Al–N1 bond length is 1.956 Å. After complexation, the C1–N1 bond is elongated from 1.299 to 1.318 Å due to the involvement of N1 in coordination. The C–O2 bond length is decreased from 1.349 to 1.321 Å. The C–C1 bond is shortened to 1.412 from 1.443 Å, and a slight elongation of the aromatic C=C bond is observed after complexation. This transformation makes a conjugated system through benzylidene and hydrazide, which results in a stable NDHIPH-Al(III) complex. The angles around Al are observed to be between 93 and 108°, which indicates that both the Al centers have a distorted trigonal-bipyramidal configuration. This complex is also characterized by a N2–H···O–NO2 hydrogen bonding interaction with a bond length of 2.130 Å.

Figure 8.

Possible complexes (A, B, and C) formed as a result of the reaction of NDHIPH with Al(NO3)3; C + PA is the complex of C with picric acid. The geometries are obtained at the B3LYP/6-311 + G(d,p) level of theory.

Figure 9.

Optimized geometry of (a) NDHIPH-Al(III), complex C, and (b) complex of NDHIPH-Al(III) with picric acid, C + PA; hydrogens are hidden for the clarity of image. Bond lengths are given in Å and all geometries are optimized at the B3LYP/6-311 + G(d,p) level of theory.

The optimized 3D geometry of complex of C with picric acid (C + PA) indicates that picric acid was bound to Al in the form of a phenoxide anion by replacing one NO3 ligand of the Al (Figure 8). The bond length between O1″ and Al was observed to be 1.850 Å, which is slightly longer than the Al–O2 bond length and shorter than the Al–ONO2 bond length (2.001 Å). The coordination through O of one of the o-NO2 groups of picric acid (with Al–O2″ bond length = 1.997 Å) stabilized the complex. Bidentate ligation of picric acid to Al may affect the aromaticity of the ring (Figure 9b).

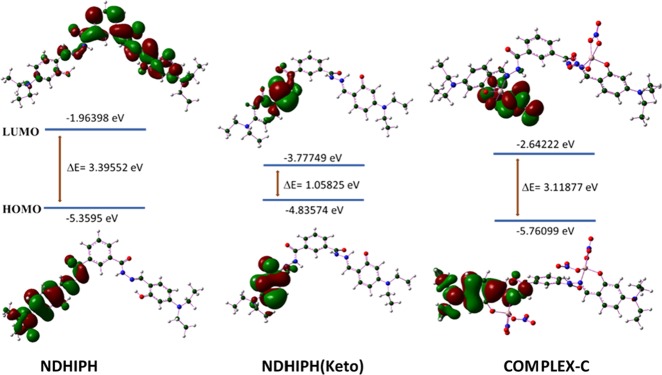

Frontier molecular orbital analysis (Figures 10 and S31) shows that the energy gap between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of NDHIPH is 3.39 eV, which is reduced to 3.12 eV after coordination with Al as in complex C.

Figure 10.

HOMO–LUMO orbitals of NDHIPH, its keto form in the excited state, and its Al(III) complex.

On the other hand, the HOMO–LUMO gap of the keto form of NDHIPH (Figure 10) is 1.06 eV in the excited state. Presumably, a slight decrease in energy gap after metal complexation is responsible for the absorption phenomenon of the ligand, while showing a bathochromic shift in the UV–visible spectrum. Contrarily, the same energy difference is greater than the HOMO–LUMO gap of the keto form in the excited state. Thus, the observed hypsochromic shift in the fluorescence spectrum can be explained.16

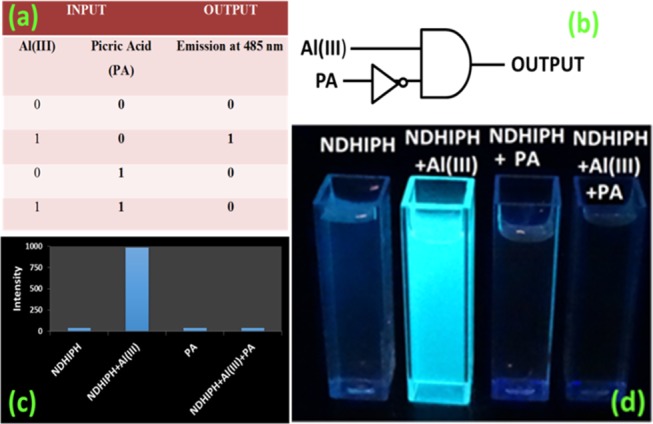

Logic Gate

The reversible behavior of the fluorogenic response of NDHIPH at 485 nm toward Al(III) ions and picric acid can be usefully engaged in the construction of an INHIBIT logic gate with two inputs, Al(III) and picric acid (Figure 11). In the first case, both the inputs are absent; there is no significant change in the fluorescence emission of NDHIPH at 485 nm, which implies that the gate is “OFF” or in the “0” state. In the second case, when only Al(III) is added, large fluorescence enhancement implies that the gate is “ON” or in the “1” state. In the third case, when only picric acid is added to NDHIPH, the result is OFF or the 0 state. In the fourth case, when both the inputs are present, the quenching (by input 2, PA) of the fluorescence of NDHIPH at 485 nm should override the fluorescence enhancement by input 1, which is in accordance with the truth table and the circuit for the INHIBIT gate.

Figure 11.

Operation of the INHIBIT logic gate. (a) Truth table corresponding to the INHIBIT logic gate. (b) Pictorial representation of the logic gate. (c) Bar chart presentation of fluorescence outputs. (d) Visual color outputs.

Paper Strip Experiment

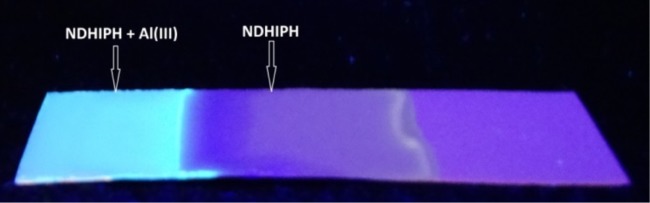

To check the practical usefulness of NDHIPH, we accomplished a paper strip experiment for the on-site detection of metal ions.

The paper strips were coated first with an aqueous solution of NDHIPH and then dried for 30 min. for uniform distribution of the sensor. After drying, these strips were dipped in a solution of Al(NO3)3 (5 μM) in distilled water and dried again for 30 min. Further, these strips were checked under a UV lamp. Bright bluish green fluorescence was observed on that part of the test strip that was dipped in the solution of Al(NO3)3, whereas the other part of the test strip showed no change. Similar color changes were observed in the solid state (Figure 12) as earlier in the solution state.

Figure 12.

Fluorescent color changes with dip sticks formed from NDHIPH (2.5 μM) in DMSO–H2O upon treatment with 5 μM Al(III). Left: after Al(III) treatment; right: before metal treatment.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have designed and synthesized a new hydrazone-based Schiff base, NDHIPH, which possesses a coordination environment of −CONH, C=N, and −OH groups and exhibits excellent selectivity and sensitivity toward Al(III). The detection limit of NDHIPH toward Al(III) is 2.53 nM. Further, the NDHIPH-Al(III) ensemble acts as a selective and sensitive probe for picric acid. DFT calculations were performed for NDHIPH, NDHIPH-Al(III), and the complex between NDHIPH-Al(III) and picric acid. The reversible behavior of NDHIPH toward Al(III) and picric acid leads to the creation of an INHIBIT logic gate. Hence, these results specify that NDHIPH will be a significant addition in the perception of sensing of trace metal ions in aqueous medium.

Experimental Section

See the Supporting Information to get details about chemicals and specifications of instruments used in the current study.

Synthesis and Characterization

Synthesis of NDHIPH

200 mg (1.02 mmol) of IPH was dissolved in 10 mL of ethanol, to which was added 398 mg (2.05 mmol) of 4-(diethylamino)-2-hydroxybenzaldehyde in 10 mL of ethanol along with 2–3 mg of zinc perchlorate.17 The color of the solution changed immediately to turbid yellow and precipitates separated out within 10 min. These precipitates were filtered, washed with methanol, and dried under vacuum for 24 h. Yield 92%. Light yellow solid. mp = 240–242 °C; 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) (Figure S1, Supporting information, δ): 1.11 (t, 12H, −CH3, J = 7 Hz), 6.13 (s, 2H, Ar), 6.28 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 8.5 Hz), 7.22 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 9 Hz), 7.69 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 7.5 Hz), 8.10 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 7.5 Hz), 8.46 (s, 2H, −CH=N and 1H, Ar), 11.42 (s, 2H, −OH); 11.97 (s, 2H, −NH); 13C NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) (Figure S2, δ): 13.0 (−CH3), 44.2 (−CH2), 97.9 (Ar), 104.2 (Ar), 106.8 (−C=), 127.1(Ar), 129.2 (Ar), 130.9 (Ar), 132.1 (Ar), 133.9 (−C=), 150.7 (CH=N), 160.1 (−C–OH) and (−C–NH), 162.1 (−C=O); FT-IR (KBr, cm–1) (Figure S6): 3530, 3202, 2968, 1619, 1582, 1349, 1247, 1138, 1073, 788, 707, 445; Elemental analysis calculated for C30H36N6O4: C, 66.16; H, 6.66; N, 15.43%. Found: C, 66.09; H, 5.18; N, 15.30%; ESI-HRMS m/z (Figure S7): 544.9233 [M]+ ion (calc 544.2793).

Synthesis of the NDHIPH-Al(III) Complex

To a 5 mL suspension of NDHIPH (0.05 g, 1.15 mmol) in ethanol, a 10 mL solution of Al(NO3)3.9H2O (0.086 g, 2.30 mmol) in distilled water was added dropwise over 15 min, and then the mixture was stirred for half an hour. The reaction mixture was concentrated and placed in an ice bath. Dark brown precipitates were collected on a Buchner funnel. mp = 300–302 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) (Figure S18, δ): 1.12 (t, 12H, −CH3, J = 6.9 Hz), 6.17 (s, 2H, Ar), 6.32 (d, 2H, Ar, J = 5.7 Hz), 7.24 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 7.5 Hz), 7.69 (t, 1H, Ar, J = 7.5 Hz), 8.10 (dd, 2H, Ar, J1 = 7.7 Hz, J2 = 1.5 Hz), 8.46 (s, 2H, −CH=N and 1H, Ar), 11.99 (s, 2H, −NH); IR (KBr, cm–1) (Figure S19): 3370, 1650, 1385, 1246, 1100, 1044, 661; ESI-HRMS m/z, (Figure S20): 798.1951 [(C30H31Al2N9O14)•]+ (calc 798.1851).

Acknowledgments

S.S. is grateful to the CSIR for a fellowship (File No. 09/254(0265)/216-EMR-I) of Research Associate. G.H. is grateful to the CSIR (India) for research Grant No. 01(2819)15/EMR-II.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.9b02132.

Spectral characterization of sensors; UV and fluorescence titrations; modified Benesi–Hildebrand plot; Job’s plots; Stern–Volmer plot; detection limit and competitive selectivity; NMR titrations; comparison table; spectral characterization of the NDHIPH-Al(III) complex and ESI-HRMS spectrum of the NDHIPH-Al(III) ensemble with picric acid; DFT calculations of NDHIPH; NDHIPH-Al(III); NDHIPH-Al(III) with picric acid (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Qin M.; Huang Y.; Li F.; Song Y. Photochromic sensors: a versatile approach for recognition and discrimination. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 9265–9275. 10.1039/C5TC01939G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Guo Z.; Park S.; Yoon J.; Shin I. Recent progress in the development of near-infrared fluorescent probes for bioimaging applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 16–29. 10.1039/C3CS60271K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Liu Z.; He W.; Guo Z. Metal coordination in photoluminescent sensing. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 1568–1600. 10.1039/c2cs35363f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Schäferling M. The Art of Fluorescence Imaging with Chemical Sensors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 3532–3554. 10.1002/anie.201105459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Wu J.; Liu W.; Ge J.; Zhang H.; Wang P. New sensing mechanisms for design of fluorescent chemosensors emerging in recent years. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 3483–3495. 10.1039/c0cs00224k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Sinkeldam R. W.; Greco N. J.; Tor Y. Fluorescent Analogs of Biomolecular Building Blocks: Design, Properties, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2579–2619. 10.1021/cr900301e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Amendola V.; Fabbrizzi L. Anion receptors that contain metals as structural units. Chem. Commun. 2009, 513–531. 10.1039/B808264M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Thomas S. W. III; Joly G. D.; Swager T. M. Chemical Sensors Based on Amplifying Fluorescent Conjugated Polymers. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 1339–1386. 10.1021/cr0501339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Basabe-Desmonts L.; Reinhoudt D. N.; Crego-Calama M. Design of fluorescent materials for chemical sensing. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 993–1017. 10.1039/b609548h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Yoon J.; Kim S. K.; Singh N. J.; Kim K. S. Imidazolium receptors for the recognition of anions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 355–360. 10.1039/b513733k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Wright A. T.; Anslyn E. V. Differential receptor arrays and assays for solution-based molecular recognition. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 14–28. 10.1039/B505518K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l Meier H. Conjugated Oligomers with Terminal Donor–Acceptor Substitution. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 2482–2506. 10.1002/anie.200461146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m Prodi L. Luminescent chemosensors: from molecules to nanoparticles. New J. Chem. 2005, 29, 20–31. 10.1039/b411758a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; n Valeur B.; Leray I. Design principles of fluorescent molecular sensors for cation recognition. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2000, 205, 3–40. 10.1016/S0010-8545(00)00246-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Kim S.; Noh J. Y.; Kim K. Y.; Kim J. H.; Kang H. K.; Nam S.-W.; Kim S. H.; Park S.; Kim C.; Kim J. Salicylimine-Based Fluorescent Chemosensor for Aluminum Ions and Application to Bioimaging. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 3597–3602. 10.1021/ic2024583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Aguilar F.; Autrup H.; Barlow S.; Castle L.; Crebelli R.; Dekant W.; Engel K.-H.; Gontard N.; Gott D.; Grilli S.; Gürtler R.; Larsen J.-C.; Leclercq; Leblanc J.-C.; Malcata F.-X.; Mennes W.; Milana M.-R.; Pratt I.; Rietjens I.; Tobback P.; Toldrá F. Safety of aluminium from dietary intake[1] - Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Food Additives, Flavourings, Processing Aids and Food Contact Materials (AFC). EFSA J. 2008, 754, 1–11. 10.2903/j.efsa.2008.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Berthon G. Aluminium speciation in relation to aluminium bioavailability, metabolism and toxicity. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 228, 319–341. 10.1016/S0010-8545(02)00021-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Greger J. L.; Sutherland J. E. Aluminum exposure and metabolism. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 1997, 34, 439–474. 10.3109/10408369709006422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e DeVoto E.; Yokel R. A. The biological speciation and toxicokinetics of aluminium. Environ. Health Perspect. 1994, 102, 940–951. 10.1289/ehp.94102940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wang B.; Xing W.; Zhao Y.; Deng X. Effects of chronic aluminum exposure on memory through multiple signal transduction pathways. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2010, 29, 308–313. 10.1016/j.etap.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kim S. H.; Cho H. S.; Kim J.; Lee S. J.; Quang D. T.; Kim J. S. Novel Optical/Electrochemical Selective 1,2,3-Triazole Ring-Appended Chemosensor for the Al3+ Ion. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 560–563. 10.1021/ol902743s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wang Y. W.; Yu M. X.; Yu Y. H.; Bai Z. P.; Shen Z.; Li F. Y.; You X. Z. A colorimetric and fluorescent turn-on chemosensor for Al3+ and its application in bioimaging. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 6169–6172. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.08.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Baral M.; Sahoo S. K.; Kanungo B. K. Tripodal amine catechol ligands: A fascinating class of chelators for aluminium(III). J. Inorg. Biochem. 2008, 102, 1581–1588. 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Exley C.; Begum A.; Woolley M. P.; Bloor R. N. Aluminum in Tobacco and Cannabis and Smoking-Related Disease. Am. J. Med. 2006, 119, 276.e9–276.e11. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Ng S. M.; Narayanaswamy R. Fluorescence sensor using a molecularly imprinted polymer as a recognition receptor for the detection of aluminium ions in aqueous media. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 386, 1235–1244. 10.1007/s00216-006-0736-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Walton J. R. Aluminum in hippocampal neurons from humans with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotoxicology 2006, 27, 385–394. 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Flaten T. P. Aluminium as a risk factor in Alzheimer’s disease, with emphasis on drinking water. Brain Res. Bull. 2001, 55, 187–196. 10.1016/S0361-9230(01)00459-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Fasman G. D. Aluminum and Alzheimer’s disease: model studies. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1996, 149, 125–165. 10.1016/0010-8545(96)89157-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Delhaize E.; Ryan P. R. Aluminium Toxicity and Tolerance in Plants. Plant Physiol. 1995, 107, 315–321. 10.1104/pp.107.2.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Godbold D. L.; Fritz E.; Hüttermann A. Aluminium toxicity and forest decline. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988, 85, 3888–3892. 10.1073/pnas.85.11.3888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Gunsé B.; Garson T.; Barcelo J. Study of aluminum toxicity by means of vital staining profiles in four cultivars of Phaseolus vulgaris L. J. Plant Physiol. 2003, 160, 1447–1450. 10.1078/0176-1617-01001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Barcaló J.; Poschenrieder C. Fast root growth responses, root exudates, and internal detoxification as clues to the mechanisms of aluminium toxicity and resistance: a review. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2002, 48, 75–92. 10.1016/S0098-8472(02)00013-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Berthon G. Aluminum speciation in relation to aluminum bioavailability, metabolism and toxicity. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 228, 319–341. 10.1016/S0010-8545(02)00021-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b World Health Organization. Aluminium in Drinking-Water: Background Document for Development of WHO Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality; World Health Organization, 2010; WHO Reference number: WHO/HSE/WSH/10.01/13. [Google Scholar]

- a Shellaiah M.; Wu Y. H.; Lin H. C. Simple pyridyl-salicylimine-based fluorescence “turn-on” sensors for distinct detections of Zn2+, Al3+ and OH– ions in mixed aqueous media. Analyst 2013, 138, 2931–2942. 10.1039/c3an36840h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Soroka K.; Vithanage R. S.; Phillips D. A.; Walker B.; Dasgupta P. K. Fluorescence Properties of Metal Complexes of 8-Hydroxyquinoline-5-sulfonic Acid and Chromatographic Applications. Anal. Chem. 1987, 59, 629–636. 10.1021/ac00131a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Singh V. P.; Tiwari K.; Mishra M.; Srivastava N.; Saha S. 5-[{(2-Hydroxynaphthalen-1-yl)methylene}amino]pyrmidine-2,4(1H,3H)-dione as Al3+ selective colorimetric and fluorescent chemosensor. Sens. Actuators, B 2013, 182, 546–554. 10.1016/j.snb.2013.03.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Tiwari K.; Mishra M.; Singh V. P. A highly sensitive and selective fluorescent sensor for Al3+ ions based on thiophene-2-carboxylic acid hydrazide Schiff base. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 12124–12132. 10.1039/c3ra41573b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Mahato P.; Saha S.; Das P.; Agarwalla H.; Das A. An overview of the recent developments on Hg2+recognition. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 36140–36174. 10.1039/C4RA03594A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ma Y. H.; Yuan R.; Chai Y. Q.; Liu X. L. A new aluminum(III)-selective potentiometric sensor based on N,N′-propanediamide bis(2-salicylideneimine) as a neutral carrier. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2010, 30, 209–213. 10.1016/j.msec.2009.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Zioła-Frankowska A.; Frankowski M.; Siepak J. New method for speciation analysis of aluminium fluoride complexes by HPLC–FAAS hyphenated technique. Talanta 2010, 80, 2120–2126. 10.1016/j.talanta.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zheng F.; Hu B. Novel bimodal porous N-(2-aminoethyl)-3-aminopropyltrimethoxysilane-silica monolithic capillary microextraction and its application to the fractionation of aluminum in rainwater and fruit juice by electrothermal vaporization inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Spectrochim. Acta, Part B 2008, 63, 9–18. 10.1016/j.sab.2007.10.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Rao G. P. C.; Seshaiah K.; Rao Y. K.; Wang M. C. Solid Phase Extraction of Cd, Cu, and Ni from Leafy Vegetables and Plant Leaves Using Amberlite XAD-2 Functionalized with 2-Hydroxy-acetophenone-thiosemicarbazone (HAPTSC) and Determination by Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 2868–2872. 10.1021/jf0600049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Thomas F.; Maslon A.; Bottero J. Y.; Rouiller J.; Montlgny F.; Genevrlere F. Aluminum(III) speciation with hydroxy carboxylic acids. Aluminum-27 NMR study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1993, 27, 2511–2516. 10.1021/es00048a031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Tong A.; Akama Y.; Tanaka S. Pre-concentration of copper, cobalt and nickel with 3-methyl-1-phenyl-4-stearoyl-5-pyrazolone loaded on silica gel. Analyst 1990, 115, 947–949. 10.1039/an9901500947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Sanz-Medel A.; Cabezuelo A. B. S.; Milacic R.; Polak T. B. The chemical speciation of aluminium in human serum. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 228, 373–383. 10.1016/S0010-8545(02)00085-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Sharma S.; Sran B. S.; Singh N.; Hundal G. From Dual to Discriminatory Sensing of CN-/F-Using Isomeric Molecules and Ascertained by Spectroscopic and DFT Methods. ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 3225–3233. 10.1002/slct.201702950. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Sharma S.; Singh J.; Singh N.; Hundal G. Spectroscopic and theoretical evaluation of solvent-assisted, cyanide selectivity of chromogenic sensors grounded on mesitylene platform and their biological applications. Sens. Actuators, B 2016, 225, 141–150. 10.1016/j.snb.2015.11.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Sharma S.; Hundal M. S.; Hundal G. Dual channel chromo/fluorogenic chemosensors for cyanide and fluoride ions – an example of in situ acid catalysis of the Strecker reaction for cyanide ion chemodosimetry. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 654–661. 10.1039/C2OB27096J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Sharma S.; Hundal M. S.; Hundal G. Selective recognition of fluoride ions through fluorimetric and colorimetric response of a first mesitylene based dipodal sensor employing thiosemicarbazones. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 2423–2427. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2013.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Sharma S.; Hundal M. S.; Singh N.; Hundal G. Nanomolar fluorogenic recognition of Cu(II) in aqueous medium—A highly selective “on–off” probe based on mesitylene derivative. Sens. Actuators, B 2013, 188, 590–596. 10.1016/j.snb.2013.07.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Bhardwaj V. K.; Sharma S.; Singh N.; Hundal M. S.; Hundal G. New tripodal and dipodal colorimetric sensors for anions based on tris/bis-urea/thiourea moieties. Supramol. Chem. 2011, 23, 790–800. 10.1080/10610278.2011.593629. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S.; Hundal M. S.; Walia A.; Vanita V.; Hundal G. Nanomolar fluorogenic detection of Al(III) by a series of Schiff bases in an aqueous system and their application in cell imaging. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 4445–4453. 10.1039/c4ob00329b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ziółek M.; Kubicki J.; Maciejewski A.; Naskrȩcki R.; Grabowska A. Enol-keto tautomerism of aromatic photochromic Schiff base N,N′N,N′-bis(salicylidene)-pp-phenylenediamine: Ground state equilibrium and excited state deactivation studied by solvatochromic measurements on ultrafast time scale. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124, 124518-1–124518-10. 10.1063/1.2179800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zgierski M. Z.; Grabowska A. Higher-Pressure Ion Funnel Trap Interface for Orthogonal Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124, 7845–7852. 10.1021/ac071091m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Moghadam A. J.; Omidyan R.; Mirkhani V. Photophysics of a Schiff base: theoretical exploration of the excited-state deactivation mechanisms of N-salicilydenemethylfurylamine (SMFA). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 2417–2424. 10.1039/C3CP54416H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Cordoba W.; Zugazagoitia J. S.; Collado-Fregoso E.; Peon J. Excited State Intramolecular Proton Transfer in Schiff Bases. Decay of the Locally Excited Enol State Observed by Femtosecond Resolved Fluorescence. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 6241–6247. 10.1021/jp072415d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodi L.; Bolletta F.; Montalti M.; Zaccheroni N. Luminescent chemosensors for transition metal ions. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2000, 205, 59–83. 10.1016/S0010-8545(00)00242-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Park H. M.; Oh B. N.; Kim J. H.; Qiong W.; Hwang I. H.; Jung K. D.; Kim C.; Kim J. Fluorescent chemosensor based-on naphthol–quinoline for selective detection of aluminum ions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 5581–5584. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.08.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Naskar B.; Bauzá A.; Frontera A.; Maiti D. K.; Mukhopadhyay C. D.; Goswami S. A versatile chemosensor for the detection of Al3+ and picric acid (PA) in aqueous solution. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 15907–15916. 10.1039/C8DT02289E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Mennucci B.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.; Caricato M.; Li X.; Hratchian H. P.; Izmaylov A. F.; Bloino J.; Zheng G.; Sonnenberg J. L.; Hada M.; Ehara M.; Toyota K.; Fukuda R.; Hasegawa J.; Ishida M.; Nakajima T.; Honda Y.; Kitao O.; Nakai H.; Vreven T.; Montgomery J. A. Jr.; Peralta J. E.; Ogliaro F.; Bearpark M.; Heyd J. J.; Brothers E.; Kudin K. N.; Staroverov V. N.; Keith T.; Kobayashi R.; Normand J.; Raghavachari K.; Rendell A.; Burant J. C.; Iyengar S. S.; Tomasi J.; Cossi M.; Rega N.; Millam J. M.; Klene M.; Knox J. E.; Cross J. B.; Bakken V.; Adamo C.; Jaramillo J.; Gomperts R.; Stratmann R. E.; Yazyev O.; Austin A. J.; Cammi R.; Pomelli C.; Ochterski J. W.; Martin R. L.; Morokuma K.; Zakrzewski V. G.; Voth G. A.; Salvador P.; Dannenberg J. J.; Dapprich S.; Daniels A. D.; Farkas O.; Foresman J. B.; Ortiz J. V.; Cioslowski J.; Fox D. J.. Gaussian 09, revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2010.

- a Ramakrishnan A.; Chourasiya S. S.; Bharatam P. V. Azine or hydrazone? The dilemma in amidinohydrazones. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 55938–55947. 10.1039/C5RA05574A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Chourasiya S. S.; Kathuria D.; Nikam S. S.; Ramakrishnan A.; Khullar S.; Mandal S. K.; Chakraborti A. K.; Bharatam P. V. Azine-Hydrazone Tautomerism of Guanylhydrazones: Evidence for the Preference Toward the Azine Tautomer. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 7574–7583. 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kathuria D.; Chourasiya S. S.; Mandal S. K.; Chakraborti A. K.; Beifuss U.; Bharatam P. V. Ring-chain isomerism in conjugated guanylhydrazones: Experimental and theoretical study. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 2857–2864. 10.1016/j.tet.2018.04.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S.; Chowdhury B.; Ghosh P. A. Highly Sensitive ESIPT-Based Ratiometric Fluorescence Sensor for Selective Detection of Al3+. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 9212–9220. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b01170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N.; Hundal M. S.; Hundal G.; Martinez-Ripoll M. Zinc templated synthesis—a route to get metal ion free tripodal ligands and lariat coronands, containing Schiff bases. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 7796–7806. 10.1016/j.tet.2005.05.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.