Abstract

Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis is a famous medicinal plant distributed in some Asian countries. This species has attracted a great deal of attention and is often used as raw materials in traditional medicine practices. With the purpose of gaining insight into the geoherbalism of wild P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis, a total of 183 dried rhizome samples from eight different regions including 16 typical or nontypical natural habitats have been analyzed by multispectral information fusion based on ultraviolet and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopies combined with partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) and hierarchical cluster analysis. From the results, the use of multispectral information fusion strategy could improve the correct classification of samples, and good classification performances have been shown according to PLS-DA models. The discrimination of samples was obtained successfully with respect to the typical and nontypical natural habitats, different collection areas of typical natural habitats, and various sampling sites in nontypical natural habitats. Additionally, the similarities among samples were presented as well. Overall, the rhizome of wild P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis exhibited various regional dependence and individual differences according to the geographical origins, and the relatively appropriate growth region with better quality consistency of samples was preliminarily selected. This study also revealed that the developed multispectral information fusion method has the potential to be a reliable analytical methodology for capturing the geoherbalism differentiation in wild P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Furthermore, it could provide more chemical evidence for the critical supplement of quality evaluation on P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis.

1. Introduction

Medicinal plants are often known as natural resources with valuable health benefits and used for therapeutic purposes owing to their exhibition of some special properties.1 In recent years, they have drawn great particular concern because of their huge medicinal and economic values. Apart from the conventional usages, many species have been served for various other purposes, which are related to health and personal care, including food supplements, health foods, and herbal teas.2,3

The special status of medicinal plants is likely to be derived from their global complex chemical constituents, and the reliable therapeutic effects are mainly expressed on the basis of these components with complicated interactions.4 In addition, the efficacy and safety of finished products are also directly dependent on the quality and chemical profiles of medicinal plant raw materials.5 However, it has been widely recognized that medicinal plants respond sensitively and rapidly to the stresses of environmental changes and adapt to these changes during the growth period, which gradually lead to the geoherbalism.6−8 Briefly, not only the type of chemical compound but also the content of effective constituents could exhibit variations under different environmental conditions. For example, Qing et al.9 investigated Macleaya cordata from four different major areas and found that the protopine-type alkaloid only existed in this species collected from one of the studied regions. Additionally, as reported by Melito et al.,10 the volatile fractions of chemical profiles in Helichrysum italicum were quantitatively differentially produced in the plants from two contrasting habitats (seaside and mountains). Hence, the study on geographical origins of medicinal plants is of great importance if the materials have relatively good qualities and uniform chemical properties.

To investigate the medicinal plants with different geographical regions, it is crucial for analytical strategies to reflect the comprehensive chemical features of the plants. With the development of analytical methods, data fusion is a novel and practical one as well as an expanding trend. This technique is a process that integrates multiple-source information from different systems to obtain information of greater quality and is focused on the characterization of a complex system of a tested sample, which can be carried out basically at three levels including data-level, feature-level, and decision-level fusion.11 In data-level fusion, data from all sources are simply concatenated into a single matrix that has as many rows as samples analyzed and as many columns as signals (variables) measured by different instruments without additional mathematical preprocessing.12 Feature-level fusion could concatenate some relevant features from each separate data source into a single dataset that is used for multivariate classification. Moreover, the scores of principal component analysis (PCA) or partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) are often used.13−15 For decision-level fusion, the results from each individual classification are fused, and a classification method is implemented for each data source.16 Generally, the first two data fusion methods are often used in many fields such as food, mushrooms, medicinal plants, and so on. For example, Dankowska et al.17 demonstrated that the feature-level fusion of fluorescence and ultraviolet and visible (UV–Vis) spectroscopies could give a complementary effect for the quantification of roasted Coffea canephora var. robusta and Coffea arabica concentration in blends. Qi et al.18 investigated Rhizoma Coptidis based on Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and Fourier transform near-infrared (FT-NIR) spectroscopies as well as the data-level and feature-level fusion, respectively, with the goal of confirming the best discrimination model. Similarly, a previous study also showed that near-infrared (NIR) and mid-infrared (MIR) spectral techniques could be fused together for distinguishing rhubarb samples that originated from different areas of China and the improved classification model could also be presented.19 Therefore, the data fusion method could enhance the entire investigation ability of each individual result and may exhibit strong potential to exploit the differences as well as quality of medicinal plant raw materials.

Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis, named “Dianchonglou” in Chinese, is a well-known medicinal plant widely used in Asian countries including China, Vietnam, Myanmar, and Nepal. The dried rhizome of this species is the main medicinal part and is often sold in Chinese herbal medicine market. In addition, it is one of the sources for Rhizome Paridis documented officially in Chinese Pharmacopoeia (version 2015), and Rhizome Paridis saponins are the main and active components in the rhizome of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis, which is also the crucial raw material for some Chinese patent medicines such as “Yunnan Baiyao”, “Gongxuening capsule”, “Jidesheng Sheyao tablet”, etc., on the account of the antitumor, anti-inflammatory, hemostatic, and anthelmintic efficiencies.20−23 Apart from the rhizome, the above-ground parts (especially the leaves) are proposed to be an alternative and more sustainable source of active ingredients compared to the rhizomes.24 In China, as an important medicinal plant resource, P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis is mainly distributed in the southwestern regions.25 It is worth mentioning that Yunnan Province of China is recognized as the typical natural habitat with better quality of this species. Due to the gradually increasing market demand and supply shortage of the wild resource, many materials collected from different regions, even nontypical natural habitats, have flooded into the market. From a previous study, the effective components of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis are different in central, southern, and western Yunnan or in other geographical locations in Yunnan Province.26 In this case, there is a great need for the investigation and comparison of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis raw materials with diverse geographical origins, which is connected with the geoherbalism of this species as well as the recognition of certain quality characteristics of the final certified products.

Accordingly, in this research, preliminary exploration of multispectral information fusion based on UV and FTIR spectroscopies together with PLS-DA and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) was carried out to attempt some of geographical classification and differentiation of the crude rhizome of wild P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis that originated from eight regions in typical and nontypical natural habitats. Meanwhile, the discrimination and comparison on the samples of typical and nontypical natural habitats, different collection regions of typical natural habitats, and various sampling sites in nontypical natural habitats were discussed. The results may provide new insights into the current knowledge and may be beneficial to future exploitation and utilization of this species of medicinal plant.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Examination and Characterization of Original Spectral Information

The average raw UV absorption spectra obtained for the methanol extracts of rhizome of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples that originated from eight regions in the range of 200–400 nm are shown in Figure 1A. Not only the similar spectral characteristics could be presented, but also the distinctness in several featured peaks is visible, which is typically considered for the initial comparison of samples. Obviously, the characteristic wavelengths of the spectra are found from 200 to 350 nm, where the useful electronic transitions are π → π* for compounds with conjugated double bonds and some n → π* and n → σ* transitions, with several common peaks in the wavelengths of 285 and 325 nm. However, the maximum absorption for each spectrum is slightly different. Especially, samples obtained from XSBN and GX have the strongest absorption at about 207 nm, probably indicating the presence of steroid saponins in P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis, while others present the strong absorption band at around 225 nm. Additionally, for the mean UV spectra, it may be appreciated that they display some differences in the whole absorption intensities that the peak heights of spectra change from samples to samples according to the collection regions. The lowest absorption of the spectrum is found in the samples collected from GBH, whereas the relatively higher one belongs to the samples that originated from Yunnan Province. In general, when the chemical component was in high concentration, the corresponding absorption intensity increased as well. It implied that the various geographical locations may have an influence on the content of chemical components in methanol extracts of the rhizome of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis.

Figure 1.

(A, B) Average original UV (A) and FTIR (B) spectra profiles of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples with different geographical regions. NJ, Nujiang; CY, Central Yunnan; WS, Wenshan; XSBN, Xishuangbanna; GBG, Guanteng; GBH, Hezhang; GA, Anshun; GX, Xingyi.

On the other hand, by careful examination of the mean original FTIR spectra (Figure 1B), it is worth noting that the spectral profiles present a similar shape with each other based on visual inspection, suggesting a homogeneous chemical constitution among the rhizome samples, despite the fact that their geographical origins were different. From the overall view of spectra, it shows a typical major broad peak at around 3384 cm–1 for the stretching vibration of −OH.27 The backbone at about 2931 cm–1 corresponds to the C–H stretching vibration of −CH2, which is revealed in all of the spectra. Furthermore, although it is difficult to identify the molecular source of unique chemical information characteristics in mid-infrared spectra of medicinal plants unambiguously, the following absorption peaks in the region of 1800–400 cm–1, which contains a large number of bands and is rich in structural information, may display spectral informative features in various compounds. The strong absorption peaks around 1639 cm–1 are mainly attributed to C=O stretching vibration of steroid saponins.3,28 Absorbance at approximately 1409 cm–1 may be due to the presence of plane deviational vibration of −CH2, while peaks that appear at 1243 cm–1 are likely to suggest the C–H deviational vibrations and C–OH stretching vibration in the benzene ring. In addition, the region from 1200 to 900 cm–1 is probably to be identified as the content of the skeletal vibration of saponins and other glycosides, which have many intensive peaks at around 1155, 1074, 1045, and 1022 cm–1.29,30 Moreover, some small but obvious peaks in the range of 900–400 cm–1 may indicate the existence of starch, especially the peaks at around 860, 765, and 582 cm–1. Totally, it could be inferred that saponins, some starch, and carbohydrates may be the main chemical composition in P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis, which was also proved by previous publications.20,26 Although 18 common absorption peaks of the average FTIR spectra of each group sample have been observed and a few significant visible differences among the spectral shapes and peak positions could be presented, there was still some variation among the samples because several diversities of the absorption intensities appeared at a number of characteristic peaks, indicating that the chemical property in the rhizome of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis may be affected by the geographical origins, which was similar to the initial analysis of UV spectra in this study.

2.2. Confirmation of the Appropriate PLS-DA Model

Since the changes along the full UV and FTIR spectra were comparatively small, it was not possible to investigate the P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples with different geographical origins accurately through simple visual inspection, making it necessary to utilize some chemometric methods. To make sure whether the collection regions could influence the chemical property of the rhizome of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis, PLS-DA was used to establish the classification models of samples. Three types of models in terms of typical and nontypical natural habitats, different collection regions of typical natural habitats, and various sampling sites in nontypical natural habitats were constructed.

For the single UV and FTIR spectra, the selection of the number of latent variables (LVs) for each model is shown in Figure 2, and the accuracy of training and test sets for the classification models based on these LVs is presented in Table 1. As can be seen in this table, the model performance of FTIR spectra is better than that of UV spectral information because the former has higher accuracy not only in the training set but also in the test set. Besides, to obtain significant information of the spectra related to the separation of samples, variable importance in projection (VIP) scores were used. The spectral information with VIP scores greater than 1 would be considered to be significantly contributive to the developed PLS-DA model, whereas the variables with VIP scores smaller than 1 are less important for this model. As shown in Figure 3 as well as Tables S1 and S2, the VIP scores of each model according to UV and FTIR spectra could be presented. It shows that individual experimental variables are identified as more significant for the discrimination of typical and nontypical natural habitats of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples belonging to two main wavebands of UV spectra, including 207–280 nm and 306–324 nm (Figure 3A and Table S1A). For the differentiation of collection areas in typical natural habitats, UV spectral information of the waveband in the range of 207–265 nm and 320–376 nm is considered to be particularly crucial, while for the classification of sampling sites of nontypical natural habitats, the variables from 207 to 272 nm and from 319 to 393 nm display distinguishable peaks (Figure 3B,C and Table S1B,C). In a word, the most relevant UV wavelengths for the distinction of rhizome samples that originated from different localities are in the spectral region of 207–265 nm, which could be roughly in accordance with the presence of dioscin (210 nm), paris saponins VII (239 nm), and paritrisides C and D (243, 250, and 260 nm) in P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis.3,29 In other words, it was possible to estimate that the differences among rhizomes of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples with different geographical regions may be in connection with some chemical components such as steroid saponins and triterpenes. For the three models on the basis of FTIR, the wavenumbers in the range of 1750 to 1000 cm–1 are responsible for each discrimination, which may suggest the existence of some steroid saponins.3,28,29 Similar to the results of UV spectra analysis, it demonstrated that the diversity of rhizome of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples obtained from different regions may be related to the distinction of a number of steroid saponins. On the whole, combining the results mentioned above, it seemed to imply that the variation of the rhizome of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples with different geographical origins may be primarily due to the diversity of steroid saponins, which agreed with the previous study.26

Figure 2.

(A–C) Selection of optimal number of LVs to construct PLS-DA models on the basis of typical and nontypical natural habitats (A), four collection regions of typical natural habitats (B), and different sampling locations in nontypical natural habitats (C) by using UV and FTIR techniques as well as low-level fusion and mid-level fusion methods.

Table 1. Number of LVs and Accuracy for Each PLS-DA Model.

| accuracy

(%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| model | technique | LV | training set | test set |

| discrimination between typical and nontypical natural habitats | UV | 2 | 83.61 | 75.41 |

| FTIR | 4 | 91.80 | 80.33 | |

| data-level fusion | 3 | 79.34 | 74.19 | |

| feature-level fusion | 2 | 94.21 | 93.55 | |

| differentiation of collection regions in typical natural habitats | UV | 5 | 63.16 | 44.44 |

| FTIR | 8 | 89.13 | 66.67 | |

| data-level fusion | 3 | 32.26 | 36.17 | |

| feature-level fusion | 3 | 93.41 | 83.72 | |

| distinction of sampling sites of nontypical natural habitats | UV | 6 | 100.00 | 73.33 |

| FTIR | 6 | 100.00 | 86.67 | |

| data-level fusion | 6 | 85.71 | 80.00 | |

| feature-level fusion | 4 | 100.00 | 100.00 | |

Figure 3.

(A–C) VIP plot of PLS-DA models of typical and nontypical natural habitats (A), different collection areas of typical natural habitats (B), and four sampling sites in nontypical natural habitats (C) according to UV spectral information. (D–F) VIP scores of PLS-DA models on the account of typical and nontypical natural habitats (D), different sampling regions of typical natural habitats (E), and four collection localities in nontypical natural habitats (F) using FTIR spectral information.

Despite the fact that the classification models of the two spectral methods could show some differences among samples, the model performance was still unsatisfactory because most of the accuracy was lower than 90%. In particular, the accuracy of the discrimination of collection areas in typical natural habitats based on UV spectra was the lowest, which was just 44.44%. It was difficult to distinguish all the samples precisely just using the individual spectroscopy technique. Nevertheless, when we combined the UV and FTIR spectral information, obvious improvement of the model performance could be presented based on the feature-level fusion with the selected LVs (Figure 2 and Table 1). The feature important variables from single data sources including UV and FTIR spectra were extracted and coalesced, which can obtain more deep and comprehensive description than the single source achieved. All the accuracy is more than 93% except that of the test set of the second model with the value of 83.72%, which is also the lowest of all the accuracy. Even so, the lowest accuracy is much higher than those of the same models in terms of the single spectral techniques as well as the data-level fusion. Therefore, the classification models based on feature-level fusion were used to investigate the P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples.

2.3. Differentiation of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis Obtained from Typical and Nontypical Natural Habitats

When studying the classification of the rhizome of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples collected from typical and nontypical natural habitats, the first two LVs were chosen according to the lowest root-mean-square error of cross-validation (RMSECV) to establish the PLS-DA model (Figure 2A) based on feature-level fusion. In this case, 94.21% of samples in the training set are correctly classified, and the accuracy of test set is 93.55%, as shown in Table 1. It demonstrated that most of the rhizome samples could be discriminated as the typical and nontypical natural habitats. Additionally, as is evident in Table 2, all of the average values of sensitivity, specificity, and efficiency are more than 92.44%, indicating relatively good classification performance of the samples. The response permutation test revealed no overfitting with the R2Y-intercept of 0.02 and Q2-intercept of −0.21. Besides, more visual information could be presented in the two-dimensional score plot of the first two LVs (Figure 4A), which shows a good separation trend of the two group samples. To gain the similarities among samples and verify the results of PLS-DA, HCA was constructed on the basis of the optimal LVs obtained by PLS-DA. The dendrogram displayed in Figure 4B provides a very simple two-dimensional plot of the data structure indicating the merging objects and distances. It is obvious that all the samples are clustering into two main classes related to typical and nontypical natural habitats. One class consists of 90% of the samples collected from typical natural habitats and one sample obtained from nontypical natural habitats, whereas the other class contains almost all of the samples of the nontypical natural habitats and the remaining samples of typical natural habitats, suggesting some diversities between samples from these two habitats, and the individual dissimilarities of the samples originated from typical natural habitats were more than those of the samples collected from the other habitats comparatively, which were roughly in agreement with the results obtained by PLS-DA. In short, according to the two chemometric methods, it could be concluded that the chemical properties of the rhizome of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis were somewhat different in typical and nontypical natural habitats.

Table 2. Classification Parameters Obtained for PLS-DA Model Based on P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis of Typical and Nontypical Natural Habitats.

| parameter | typical natural habitat | nontypical natural habitat | average |

|---|---|---|---|

| training set | |||

| false positive rate (%) | 10.71 | 4.30 | 7.51 |

| false negative rate (%) | 4.30 | 10.71 | 7.51 |

| sensitivity (%) | 95.70 | 89.29 | 92.49 |

| specificity (%) | 89.29 | 95.70 | 92.49 |

| efficiency (%) | 92.44 | 92.44 | 92.44 |

| test set | |||

| false positive rate (%) | 10.00 | 2.13 | 6.06 |

| false negative rate (%) | 2.13 | 10.00 | 6.06 |

| sensitivity (%) | 97.87 | 90.00 | 93.94 |

| specificity (%) | 90.00 | 97.87 | 93.94 |

| efficiency (%) | 93.85 | 93.85 | 93.85 |

| RMSEE | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.26 |

| RMSECV | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.28 |

| R2-intercept | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 |

| Q2-intercept | –0.21 | –0.21 | –0.21 |

Figure 4.

(A, B) PLS-DA score plot (A) and HCA dendrogram (B) of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples obtained from typical and nontypical natural habitats. Samples marked in a red frame indicates the misclassified ones.

2.4. Discrimination of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis with Different Collection Regions in Typical Natural Habitats

With respect to the differentiation among rhizomes of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples collected from four geographical regions of typical natural habitats, the PLS-DA model was carried out to investigate significant differences among the tested groups of samples with three LVs. The four classes, NJ, DZ, WS, and XSBN, present comparably satisfactory discrimination results with 93.41% accuracy for the training set and 83.72% accuracy for the test set, as can be seen in Table 1. In addition, this classification model exhibits good sensitivity, specificity, and efficiency for the training set with the average value of 94.32, 93.95, and 94.10%, respectively (Table 3). For the test set, the average sensitivity, specificity, and efficiency are more than 84.31%, which are also acceptable for the model. R2-intercept and Q2-intercept values presented goodness of fit of the established model. These results indicated that the PLS-DA method was able to efficiently model the rhizome of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis with different geographical locations of typical natural habitats, which also implied that the collection areas could influence the chemical properties of samples. Moreover, as shown in the score plot of LV 1 and LV 2 (Figure 5A), it is initially found that the three collection regions of typical natural habitats, named NJ, CY, and XSBN, have displayed good separation with each other, suggesting obvious distinction and regional dependence among the samples originated from these three areas. Additionally, most of the samples obtained from the WS region are mixed with those of the NJ areas, and both LV 1 and LV 2 are determined mainly by positive scores for these samples as well as samples from the remaining two areas distributed in other three quadrants, indicating that samples from the first two regions may be similar with each other. Besides, samples collected from CY, which mainly get together in the left side of the score plot, may have distinct differences with other samples that almost group together at the right side.

Table 3. Classification Parameters Obtained for PLS-DA Model of the P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis Samples with Different Collection Regions in Typical Natural Habitats.

| typical

natural habitat |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| parameter | NJ | CY | WS | XSBN | average |

| training set | |||||

| false positive rate (%) | 4.35 | 6.78 | 6.33 | 6.76 | 6.05 |

| false negative rate (%) | 12.00 | 5.71 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 5.68 |

| sensitivity (%) | 88.00 | 94.29 | 100.00 | 95.00 | 94.32 |

| specificity (%) | 95.65 | 93.22 | 93.67 | 93.24 | 93.95 |

| efficiency (%) | 91.75 | 93.75 | 96.78 | 94.12 | 94.10 |

| test set | |||||

| false positive rate (%) | 11.76 | 17.86 | 15.00 | 16.67 | 15.32 |

| false negative rate (%) | 25.00 | 11.11 | 16.67 | 10.00 | 15.69 |

| sensitivity (%) | 75.00 | 88.89 | 83.33 | 90.00 | 84.31 |

| specificity (%) | 88.24 | 82.14 | 85.00 | 83.33 | 84.68 |

| efficiency (%) | 81.35 | 85.45 | 84.16 | 86.60 | 84.39 |

| RMSEE | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.21 |

| RMSECV | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.25 |

| R2-intercept | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| Q2-intercept | –0.29 | –0.30 | –0.25 | –0.30 | –0.29 |

Figure 5.

(A, B) LV 1–LV 2 score plot (A) and resulting dendrogram of HCA (B) for P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples according to four collection regions of typical natural habitats. Samples marked in a red frame indicates the misclassified ones.

A similar discrimination pattern is observed in the HCA dendrogram of the rhizome samples (Figure 5B). Overall, apart from 10 samples, other samples are grouped together as their geographical origins, and clustering of samples in the same group means a large similarity on their chemical constituents. In addition, samples of NJ and WS can be recognized to have relatively closer relationships because they can cluster into the same branch at first. For the samples originated from CY, they are classified into one subfraction and reveal a difference compared with others, which is consistent with the results acquired by PLS-DA. Meanwhile, it also showed that the individual differences of samples were various based on the collection regions. In Figure 5B, samples from NJ are likely to have the most obvious individual discrepancies because 16.2% of these samples cluster into another group. Subsequently, samples with the geographical origin of CY also have some individual diversities due to the fact that 5.6% of these samples get together with another class. The least individual differences are exhibited in samples obtained in XSBN, and all of them group into the same branch, which also indicated better quality consistency. From the consequence mentioned in Section 2.3, great individual differences could be presented among samples from the typical natural habitats. However, in this section, an interesting finding implied that not all of the samples collected from typical natural habitats had remarkable individual dissimilarities and it may further depend on the small regions of the collection. Consequently, according to the results in this section, collection regions in the typical natural habitats could affect the chemical properties of the rhizome of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis, and the individual discrepancies in the samples may be decided by different areas.

2.5. Comparison of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis Collected from Different Sampling Sites of Nontypical Natural Habitats

Apart from the typical natural habitats, the collection sites of the nontypical natural habitats may also have impacts on the chemical components of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples. Similarly, the fusion matrix was carried out by PLS-DA for establishing the discrimination model of the rhizome samples. In fact, the first four LVs were used, and the detailed parameters are shown in Table 4. With regard to the training and test sets, all the values of sensitivity, specificity, and efficiency are 100%, suggesting perfect performance of the classification model without any false prediction. In other words, the rhizome of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples could be exactly discriminated by the geographical origins of nontypical natural habitats. In addition, the two-dimensional plot using LV 1 and LV 2 is shown in Figure 6A. In general, the distribution trends could interpret the relationships among studied rhizome samples. First, individual samples belonging to the same collection site are grouped together, and the four classes are distinguished in accordance with their origins, indicating the differences of the chemical constituents of these samples. Likewise, the regional dependence may occur in these samples. However, samples from GBG and GBH are distributed closely, and LV 2 is determined mainly by the strong positive scores for these samples, while the negative scores on LV 2 are found for samples belonging to the region of GA and GX, which implied the similarity of the chemical properties of the samples collected from the first two areas. For the dendrogram of HCA displayed in Figure 6B, it reveals that all the samples could cluster as their collection sites, and GBG as well as GBH classes could be readily discriminated from the other samples, which also verify the results of PLS-DA stating that different geographical origins could be one of the factors that affect the chemical profiles of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis in nontypical natural habitats. Furthermore, on the other hand, it also demonstrated that a few individual differences of the tested samples from all the four regions in nontypical natural habitats could be presented, which may be inferred that the quality of individuals in each location was relatively consistent.

Table 4. Parameters of PLS-DA Modeling on P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis with Different Sampling Sites of Nontypical Natural Habitats.

| nontypical

natural habitat |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| parameter | GBG | GBH | GA | GX | average |

| training set | |||||

| false positive rate (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| false negative rate (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| sensitivity (%) | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| specificity (%) | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| efficiency (%) | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| test set | |||||

| false positive rate (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| false negative rate (%) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| sensitivity (%) | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| specificity (%) | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| efficiency (%) | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| RMSEE | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| RMSECV | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.40 | 0.32 |

| R2-intercept | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.20 |

| Q2-intercept | –0.54 | –0.46 | –0.55 | –0.55 | –0.53 |

Figure 6.

(A, B) Score plot of the first two LVs of PLS-DA (A) and HCA dendrogram (B) of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples in terms of different geographical origins of nontypical natural habitats.

Raw material examination is a critical process in the industrial production of pharmaceuticals. According to previous studies, there were some analytical techniques used to investigate P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis including UV, NIR, FTIR, HPLC, UPLC-MS, etc.26,31−34 In the present study, multispectral information fusion in conjunction with chemometrics was proved to be a potential tool to rapidly and comprehensively compare and evaluate different properties of wild P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis that originated from eight collection regions. This method contained more chemical information than that of a single technique and may offer a new insight into the geoherbalism differentiation of this species of medicinal plant. In total, the typical and nontypical natural habitats as well as the different situated areas in the same habitats could play important roles in the influence on the chemical properties of samples. Additionally, both the regional dependency and individual differences among samples relied on the geographical origins. Considering the fact that the sampling locations are far related regions, such different geographical conditions could be existent.

For the typical natural habitat, Yunnan Province is the main part of the low-latitude plateau in China, which is influenced by the complicated three-dimensional climate with the long total sun exposure time, strong UV light, relatively stable average year temperature, the considerable intraday temperature variation, and obvious alternating dry and rainy seasons.35P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis that is native to this province has relatively better quality, and it is one of the geoherbs in Yunnan Province. However, the nontypical natural habitat, which is Guizhou Province, is characterized by subtropical plateau monsoon climate based on lower average altitude and total sun exposure time as well as unstable average year temperature than those of Yunnan Province.36 By the way, abundant annual precipitation is also present in Guizhou Province. During the progress of growth, the changes of higher plants are a result of the interaction between plants and biotic and abiotic environments.37 As reported by Ren et al.,38 the accumulation of bioactive products in rhubarb was impacted by the geographic distribution and soil components. In addition, Zheng et al.39 demonstrated that the accumulation of flavonol glycosides in Hippophae rhamnoides ssp. rhamnoides berries was associated negatively with the sum of the daily mean temperatures from the start of growth season until the day of harvest. Sometimes, the chemical properties of medicinal plants are almost connected with the synergy of a variety of environmental factors, and their relationships were complex.40 So, for the results of our study, the differences among samples from typical and nontypical natural habitats may be related to environmental factors, such as light quality, sun exposure time, temperature, and rainfall. Besides, the individual dissimilarities of samples obtained from typical natural habitats were more than others, which may be due to the relatively more complicated environment in Yunnan Province.

On the other hand, although there were some samples collected from the typical natural habitats, obvious differences were also exhibited. From the results, samples with the geographical origin of Xishuangbanna, located in the south part of Yunnan Province, were somewhat special because of their least individual differences and relative better quality consistency. According to previous studies, Zhao et al.32 showed that the content of polyphyllin I and total steroid saponins in P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis obtained from southwestern Yunnan was the highest in all the samples. Moreover, the content of some chemical compounds of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis from different regions in Yunnan Province was diverse, and the quality of the tested samples from south Yunnan was better than those from the central area, as reported by Yang et al.26 These findings were similar to our study and may sustain the special phenomenon in this work. Comparing the environmental condition of this region to others in Yunnan Province, the rainfall in Xishuangbanna is relatively much more than that in Nujiang, Central Yunnan, and Wenshan regions. More interestingly, samples from nontypical natural habitats with great rainfall also had consistent qualities in each collection site. Hence, it could be inferred that precipitation may be one of the dominant factors for the quality consistency of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Meanwhile, from the perspective of quality consistency, Xishuangbanna of Yunnan Province as one of the typical natural habitats of wild P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis may be the relative suitable growth area for this species. Nevertheless, it is difficult to speculate which site in nontypical natural habitats is the best. Furthermore, since time immemorial, people have gathered plant resources for their demands, and medicinal plants play an important role in both traditional medicines used and trade commodities in many countries.1 In recent years, the demand for a wide variety of wild medicinal plants is increasing with growth in human needs, numbers, and commercial trade, which give rise to some wild species being overexploited, and some of them are recommended to be brought into artificial cultivation systems to avoid further loss of endangered species and to give a continuous and uniform supply of medicinal plants.41 The raw material selection and growth locations are crucial for the final cultivated plants. In this study, with respect to P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis, samples collected from Xishuangbanna could be considered to be the better raw material with consistent quality for artificial cultivation of this species. However, further studies are needed to investigate the reliability and reason for this phenomenon.

3. Conclusions

In the present paper, the use of multispectral information fusion combined with chemometric methods was investigated to condense the information brought by UV and FTIR spectroscopies for the geoherbalism differentiation of wild P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis raw materials. In conclusion, the variation of this species was correlated with their geographical origins, not only the typical and nontypical natural habitats but also the different situated locations in the same habitats. Meanwhile, the degree of regional dependence and individual discrepancy also relied on the collection regions. In addition, Xishuangbanna of Yunnan Province as one of the typical natural habitats of wild P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis was recommended as the relative suitable growth area for this species with better quality consistency. Totally, it may contribute to a more entire complement of current studies on the development and utilization of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis Samples and Reagents

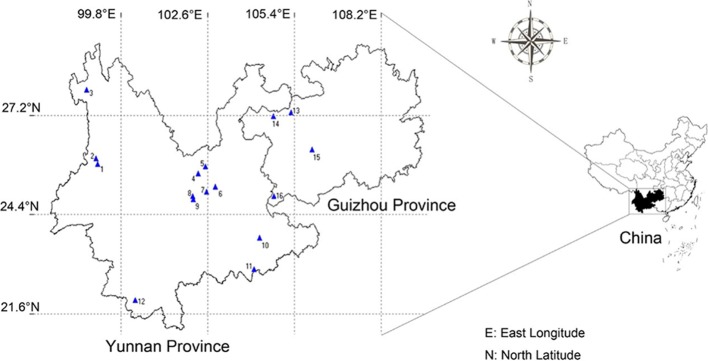

A total of 183 wild fresh P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples were obtained from eight distinct regions (16 collection sites) in Yunnan and Guizhou provinces of China, including Nujiang (NJ), Central Yunnan (CY), Wenshan (WS), Xishuangbanna (XSBN), Guanteng (GBG), Hezhang (GBH), Anshun (GA), and Xingyi (GX). Among them, the first four regions belonging to Yunnan Province are the typical habitats of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis, while the other four areas of Guizhou Province are nontypical natural habitats of this species. The botanical origins were identified by Jinyu Zhang from Yunnan Academy of Agricultural Sciences, and voucher specimens of all samples collected were stored at the Institute of Medicinal Plants, Yunnan Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Detailed sample information is specified in Table 5 and Figure 7. After collection, the fresh materials were washed clean immediately, the rhizome of each sample was cut into small pieces, and then they were dried in the shade. Afterward, the dried rhizome samples were ground into fine powder, passed through a 100-mesh stainless steel sieve, and kept in new labeled Ziploc bags at room temperature prior to use. For the reagents, methanol of analytical grade purchased from Xilong Chemical Company, Ltd. (China), and potassium bromide (KBr) of spectroscopic grade were used in this study.

Table 5. Information of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis Samples.

| number | code | collection site | quantity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NJ | Yipian, Lushui, Nujiang, Yunnan | 9 |

| 2 | NJ | Ronghua, Lushui, Nujiang, Yunnan | 14 |

| 3 | NJ | Gongshan, Nujiang, Yunnan | 14 |

| 4 | CY | Wuding, Chuxiong, Yunnan | 9 |

| 5 | CY | Luquan, Kunming, Yunnan | 7 |

| 6 | CY | Guandu, Kunming, Yunnan | 7 |

| 7 | CY | Xishan, Kunming, Yunnan | 10 |

| 8 | CY | Xiaojie, Yuxi, Yunnan | 13 |

| 9 | CY | Liujie, Yuxi, Yunnan | 7 |

| 10 | WS | Yanshan, Wenshan, Yunnan | 9 |

| 11 | WS | Maguan, Wenshan, Yunnan | 11 |

| 12 | XSBN | Menghai, Xishuangbanna, Yunnan | 30 |

| 13 | GBG | Guanteng, Bijie, Guizhou | 7 |

| 14 | GBH | Hezhang, Bijie, Guizhou | 6 |

| 15 | GA | Anshun, Guizhou | 15 |

| 16 | GX | Xingyi, Guizhou | 15 |

Figure 7.

Sampling location of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis in Yunnan and Guizhou provinces.

4.2. UV Spectroscopic Analysis

Accurately weighed rhizome powders (0.05 g) were extracted by an ultrasonic extraction apparatus for 30 min at 55 kHz with 5.0 mL of methanol. Then, the extracted solution was adjusted to the initial weight by adding methanol as needed and filtered with analytical filter paper. After that, the filtrates were used as sample solution for final UV qualitative analysis. The spectra of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples were immediately acquired using a UV-2550 UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with two quartz cells with an optical path of 1 cm. One cell was used for the extracts of samples, and the other one was for methanol. In addition, UV spectral analysis was carried out in the working range from 200 to 400 nm with a sampling interval of 1.0 nm, and the blank spectrum was scanned with methanol. Before each measurement, baseline correction was also conducted. Each UV spectrum was recorded in triplicate, and all further data analyses were performed based on the average spectrum of each triplicate. Moreover, the original spectra were pretreated by the third derivative so as to enlarge the difference among spectra.

4.3. FTIR Spectra Acquisition

The FTIR spectra of samples were collected through KBr pellets, in which the ratio of KBr to sample was 100:1.5 (w/w) by using a Frontier FTIR spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer, USA) equipped with a deuterated triglycine sulfate (DTGS) detector at a resolution of 4 cm–1 with 16 scans in the region of 4000–400 cm–1. Each spectrum with high signal-to-noise signal was recorded by an average of these 16 scans. All the analyses were carried out under the condition of constant temperature (25 °C) and humidity (30%). The sample spectra were obtained by subtracting the background measured according to pure dried KBr in tablet form with the same parameters for the sake of removing unwanted absorbance bands of water and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Each sample was scanned with three replicates, and the average of three spectra obtained from each same sample was used for subsequent data analyses. In addition, all the raw FTIR spectra were automatically baseline-corrected and automatically smoothed with the aid of Spectrum for Windows software (Nicolet OMNIC 9.7.7, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and also preprocessed by the second derivative and standard normal variate, which were applied to correct light scatter and reduce the changes in the light path length as well as remove the overlapping peaks.

4.4. Statistical Analysis

The preprocessed individual UV and FTIR spectral information was first subjected to establish PLS-DA models respectively so as to carry out the investigation among P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples on the basis of the typical and nontypical natural habitats, various collection regions of typical natural habitats, and different sampling location in nontypical natural habitats. In general, this method is a variation of the partial least squares regression algorithm for discriminant analysis and belongs to the group of the supervised learning methods, which has initial knowledge of the classes.42,43 It could transform the observed data information into a set of several intermediate linear LVs that are useful to predict the dependent variables and demonstrate whether a given sample belongs to a given class.44 The final model is decided by the best number of LVs selected in terms of the minimum value of RMSECV.45 Prior to the construction of PLS-DA models, two-thirds of samples from each group were selected by Kennard–Stone algorithm for the training set, and the remaining samples were used as the test set. Simultaneously, single spectral information obtained from UV and FTIR spectroscopies were directly grouped into a new dataset to form the data-level fusion matrix. In addition, the scores from individual UV and FTIR spectral information were joined together for the feature-level fusion data block. These two fusion data matrices were also used to build PLS-DA models, which were compared with those of single UV and FTIR spectra via the accuracy of training and tests as well. After that, the appropriate models were confirmed to discuss the differences among samples. The validation of the model was conducted by using 7-fold cross-validation and permutation tests (n = 200). In addition, the performance of the selected models was further evaluated with respect to some statistical parameters including false positive rate, false negative rate, sensitivity, specificity, efficiency, the root mean square error of estimation (RMSEE), RMSECV, R2-intercept, and Q2-intercept. The false positive rate and false negative rate, which represent the incorrectly identified samples of positive and negative class, respectively, could express the trueness in qualitative analysis while sensitivity and specificity, which represent the model ability to classify samples, are related to the selectivity of the method.46 The efficiency, which presents the geometric mean of the specificity and sensitivity, could summarize these two parameters of model performance, and the index values of efficiency vary between 0 and 100%.47 For the lowest RMSECV, it could guarantee the LVs collected as much as possible, and they are not overfitted.48 Besides, if the intercept of R2 was below 0.4 and that of Q2 was below −0.05 in the permutation test, then the built PLS-DA model was considered as an appropriate model without overfitting.49 Moreover, HCA, which was intended to create groups that maximize the cohesion internally and maximize separation externally, was eventually employed to explain the degree of similarities among different classes of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis samples by using Ward’s clustering algorithm. In this study, PLS-DA and HCA were performed by SIMCA-P+ 13.0 (Umetrics, Umeå, Sweden) and R statistical analysis program (version 3.4.1; R Development Core Team), respectively.

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81460584) and the Science and Technology Planning Project in Yunnan Province (2017RA001).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.9b02818.

Figure S1, rhizome of P. polyphylla var. yunnanensis sold in Chinese herbal medicine market; Table S1A, VIPs of the PLS-DA model of typical and nontypical natural habitats according to UV spectral information; Table S1B, VIPs of the PLS-DA model based on different collection areas of typical natural habitats according to UV spectral information; Table S1C, VIPs of the PLS-DA model based on four sampling sites in nontypical natural habitats according to UV spectral information; Table S2A, VIPs of the PLS-DA model of typical and nontypical natural habitats according to FTIR spectral information; Table S2B, VIPs of the PLS-DA model based on different collection areas of typical natural habitats according to FTIR spectral information; Table S2C, VIPs of the PLS-DA model based on four sampling sites in nontypical natural habitats according to FTIR spectral information (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ashiq S.; Hussain M.; Ahmad B. Natural occurrence of mycotoxins in medicinal plants: a review. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2014, 66, 1–10. 10.1016/j.fgb.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton A. C. Medicinal plants, conservation and livelihoods. Biodiversity Conserv. 2004, 13, 1477–1517. 10.1023/B:BIOC.0000021333.23413.42. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nohara T.; Yabuta H.; Suenobu M.; Hida R.; Miyahara K.; Kawasaki T. Steroid glycosides in Paris polyphylla SM. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1973, 21, 1240–1247. 10.1248/cpb.21.1240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong W.; Wang J.; Zang Q.; Xing X.; Zhao Y.; Liu W.; Jin C.; Li Z.; Xiao X. Fingerprint-efficacy study of artificial Calculus bovis in quality control of Chinese materia medica. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 1342–1347. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.01.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindaraghavan S.; Sucher N. J. Quality assessment of medicinal herbs and their extracts: Criteria and prerequisites for consistent safety and efficacy of herbal medicines. Epilepsy Behav. 2015, 52, 363–371. 10.1016/j.yebeh.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. J.; Jiang Y.; Li P. Chemistry, bioactivity and geographical diversity of steroidal alkaloids from the Liliaceae family. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006, 23, 735–752. 10.1039/b609306j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagunin A. A.; Goel R. K.; Gawande D. Y.; Pahwa P.; Gloriozova T. A.; Dmitriev A. V.; Ivanov S. M.; Rudik A. V.; Konova V. I.; Pogodin P. V.; Druzhilovsky D. S.; Poroikov V. V. Chemo- and bioinformatics resources for in silico drug discovery from medicinal plants beyond their traditional use: a critical review. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 1585–1611. 10.1039/C4NP00068D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S.; Li Z.; Wang H.; Von Arx G.; Lü Y.; Wu X.; Wang X.; Liu G.; Fu B. Roots of forbs sense climate fluctuations in the semi-arid Loess Plateau: Herb-chronology based analysis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28435. 10.1038/srep28435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qing Z. X.; Liu X. B.; Wu H. M.; Cheng P.; Liu Y. S.; Zeng J. G. An improved separation method for classification of Macleaya cordata from different geographical origins. Anal. Methods 2015, 7, 1866–1871. 10.1039/C4AY02600D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melito S.; Petretto G. L.; Podani J.; Foddai M.; Maldini M.; Chessa M.; Pintore G. Altitude and climate influence Helichrysum italicum subsp. microphyllum essential oils composition. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 80, 242–250. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B.; Wu H.; Li S. F. Y. Development of variable pathlength UV-Vis spectroscopy combined with partial-least-squares regression for wastewater chemical oxygen demand (COD) monitoring. Talanta 2014, 120, 325–330. 10.1016/j.talanta.2013.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borràs E.; Ferré J.; Boqué R.; Mestres M.; Aceña L.; Busto O. Data fusion methodologies for food and beverage authentication and quality assessment-A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 891, 1–14. 10.1016/j.aca.2015.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biancolillo A.; Bucci R.; Magrí A. L.; Magrí A. D.; Marini F. Data-fusion for multiplatform characterization of an Italian craft beer aimed at its authentication. Anal. Chim. Acta 2014, 820, 23–31. 10.1016/j.aca.2014.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi T.; Zhu L.; Peng W.-L.; He X.-C.; Chen H.-L.; Li J.; Yu T.; Liang Z.-T.; Zhao Z.-Z.; Chen H.-B. Comparison of ten major constituents in seven types of processed tea using HPLC-DAD-MS followed by principal component and hierarchical cluster analysis. LWT--Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 194–201. 10.1016/j.lwt.2015.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q. L.; Zhu L.; Tang Y. N.; Kwan H. Y.; Zhao Z. Z.; Chen H. B.; Yi T. Comparative evaluation of chemical profiles of three representative ″snow lotus″ herbs by UPLC-DAD-QTOF-MS combined with principal component and hierarchical cluster analyses. Drug Test. Anal. 2017, 9, 1105–1115. 10.1002/dta.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Márquez C.; López M. I.; Ruisánchez I.; Callao M. P. FT-Raman and NIR spectroscopy data fusion strategy for multivariate qualitative analysis of food fraud. Talanta 2016, 161, 80–86. 10.1016/j.talanta.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dankowska A.; Domagała A.; Kowalewski W. Quantification of Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora var. robusta concentration in blends by means of synchronous fluorescence and UV-Vis spectroscopies. Talanta 2017, 172, 215–220. 10.1016/j.talanta.2017.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L.; Ma Y.; Zhong F.; Shen C. Comprehensive quality assessment for Rhizoma Coptidis based on quantitative and qualitative metabolic profiles using high performance liquid chromatography, Fourier transform near-infrared and Fourier transform mid-infrared combined with multivariate statistical analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 161, 436–443. 10.1016/j.jpba.2018.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W.; Zhang X.; Zhang Z.; Zhu R. Data fusion of near-infrared and mid-infrared spectra for identification of rhubarb. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2017, 171, 72–79. 10.1016/j.saa.2016.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.-Y.; Wang Y.-Z.; Zhao Y.-L.; Yang S.-B.; Zuo Z.-T.; Yang M.-Q.; Zhang J.; Yang W.-Z.; Yang T.-M.; Jin H. Phytochemicals and bioactivities of Paris species. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2011, 13, 670–681. 10.1080/10286020.2011.578247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- State Pharmacopoeia Commission , Chinese Pharmacopoeia; China Medical Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2015, 260. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. G.; Zhang J.; Zhang J. Y.; Wang Y. Z. Research progress in chemical constituents in plants of Paris L. and their pharmacological effects. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2016, 47, 3301–3323. [Google Scholar]

- Qin X. J.; Yu M. Y.; Ni W.; Yan H.; Chen C. X.; Cheng Y. C.; He L.; Liu H. Y. Steroidal saponins from stems and leaves of Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Phytochemistry 2016, 121, 20–29. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2015.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin X. J.; Ni W.; Chen C. X.; Liu H. Y. Seeing the light: Shifting from wild rhizomes to extraction of active ingredients from above-ground parts of Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 224, 134–139. 10.1016/j.jep.2018.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura M. N.Liliaceae. In Flowering Plants· Monocotyledons;. Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1988, 343–353. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Jin H.; Zhang J.; Zhang J.; Wang Y. Quantitative evaluation and discrimination of wild Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis (Franch.) Hand.-Mazz from three regions of Yunnan Province using UHPLC-UV-MS and UV spectroscopy couple with partial least squares discriminant analysis. J. Nat. Med. 2017, 71, 148–157. 10.1007/s11418-016-1044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C.; Shao Q.; Ma Z.; Li B.; Zhao X. Physical and chemical characterizations of corn stalk resulting from hydrogen peroxide presoaking prior to ammonia fiber expansion pretreatment. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 83, 86–93. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.12.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.; Wang L.; Wang G. C.; Wang H.; Dai Y.; Yang X. X.; Ye W. C.; Li Y. L. Triterpenoid saponins from rhizomes of Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis. Carbohydr. Res. 2013, 368, 1–7. 10.1016/j.carres.2012.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. B.; Thakur R. S.; Schulten H. R. Spirostanol saponins from Paris polyphylla, structures of polyphyllin C, D, E and F. Phytochemistry 1980, 21, 2925–2929. 10.1016/0031-9422(80)85070-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao X.; Zhao C.; Shao Q.; Hassan M. Structural characterization of corn stover lignin after hydrogen peroxide presoaking prior to ammonia fiber expansion pretreatment. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 6022–6030. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.8b00951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T.; Liu H.; Liu X.-T.; Xu D.-r.; Chen X.-q.; Wang Q. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of steroidal saponins in crude extracts from Paris polyphylla var. yunnanensis and P. polyphylla var. chinensis by high performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2010, 51, 114–124. 10.1016/j.jpba.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Zhang J.; Yuan T.; Shen T.; Li W.; Yang S.; Hou Y.; Wang Y.; Jin H. Discrimination of wild Paris based on near infrared spectroscopy and high performance liquid chromatography combined with multivariate analysis. PLoS One 2014, 9, e89100 10.1371/journal.pone.0089100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Liu E.; Li P. Chemotaxonomic studies of nine Paris species from China based on ultra-high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2017, 140, 20–30. 10.1016/j.jpba.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z.; Zhang J.; Xu F.; Wang Y.; Zhang J. Rapid and simple determination of polyphyllin I, II, VI, and VII in different harvest times of cultivated Paris polyphylla Smith var. yunnanensis (Franch.) Hand.-Mazz by UPLC-MS/MS and FT-IR. J. Nat. Med. 2017, 71, 139–147. 10.1007/s11418-016-1043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Wang X.; Guo J.; Xia Q.; Zhao G.; Zhou H.; Xie F. Metabolic profiling of Chinese tobacco leaf of different geographical origins by GC-MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 2597–2605. 10.1021/jf400428t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Pang T.; Li Y.; Wang X.; Li Q.; Lu X.; Xu G. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometric method for metabolic profiling of tobacco leaves. J. Sep. Sci. 2011, 34, 1447–1454. 10.1002/jssc.201100106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmesan C.; Yohe G. A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature 2003, 421, 37. 10.1038/nature01286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren G.; Li L.; Hu H.; Li Y.; Liu C.; Wei S. Influence of the environmental factors on the accumulation of the bioactive ingredients in Chinese rhubarb products. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0154649 10.1371/journal.pone.0154649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Kallio H.; Yang B. Sea buckthorn (Hippophaë rhamnoides ssp. rhamnoides) berries in Nordic environment: compositional response to latitude and weather conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 5031–5044. 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b00682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M. X.; Chen A. J.; Guo B. L.; Huang W. H.; Cao X. J.; Hou M. L. Effects of environmental factors on quality of wild Astragalus membranaceus var. mongholicus grown in Hengshan Mountain, Shanxi Province. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2012, 43, 984–989. [Google Scholar]

- Schippmann U.; Leaman D. J.; Cunningham A.. Impact of cultivation and gathering of medicinal plants on biodiversity: global trends and issues. Biodiversity and the Ecosystem Approach in Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries; FAO’s Inter-Departmental Working Group on Biological Diversity for Food and Agriculture: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- de Santana F. B.; Gontijo L. C.; Mitsutake H.; Mazivila S. J.; de Souza L. M.; Neto W. B. Non-destructive fraud detection in rosehip oil by MIR spectroscopy and chemometrics. Food Chem. 2016, 209, 228–233. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C.; Cao Y.; Ma Z.; Shao Q. Optimization of liquid ammonia pretreatment conditions for maximizing sugar release from giant reed (Arundo donax L.). Biomass Bioenergy 2017, 98, 61–69. 10.1016/j.biombioe.2017.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhardt L.; Bro R.; Zeković I.; Dramićanin T.; Dramićanin M. D. Fluorescence spectroscopy coupled with PARAFAC and PLS DA for characterization and classification of honey. Food Chem. 2015, 175, 284–291. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.11.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monakhova Y. B.; Hohmann M.; Christoph N.; Wachter H.; Rutledge D. N. Improved classification of fused data: Synergetic effect of partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) and common components and specific weights analysis (CCSWA) combination as applied to tomato profiles (NMR, IR and IRMS). Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2016, 156, 1–6. 10.1016/j.chemolab.2016.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trullols E.; Ruisánchez I.; Rius F. X. Validation of qualitative analytical methods. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2004, 23, 137–145. 10.1016/S0165-9936(04)00201-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveri P.; Downey G. Multivariate class modeling for the verification of food-authenticity claims. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2012, 35, 74–86. 10.1016/j.trac.2012.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L.; Liu H.; Li J.; Li T.; Wang Y. Feature fusion of ICP-AES, UV-Vis and FT-MIR for origin traceability of Boletus edulis mushrooms in combination with chemometrics. Sensors 2018, 18, 241. 10.3390/s18010241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang Y.; Tong H.; Luo P.; Kong H.; Xu Z.; Yin P.; Xu G. A high throughput metabolomics method and its application in female serum samples in a normal menstrual cycle based on liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Talanta 2018, 185, 483–490. 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.03.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.