Abstract

Purpose: We explored the perspectives of racialized physiotherapists in Canada on their experiences of racism in their roles as physiotherapists. Method: This qualitative descriptive cross-sectional study used semi-structured, one-on-one interviews. Data were organized using NVivo qualitative analysis software and analyzed using inductive and deductive coding following the six-step DEPICT method. Results: Twelve Canadian licenced physiotherapists (four men and eight women, three rural and nine urban, from multiple racialized groups) described the experiences of racism they faced in their roles as physiotherapists at the institutionalized, personally mediated, and internalized levels. These experiences were shaped by their personal characteristics, including accent, geographical location, and country of physiotherapy (PT) education. Participants described their responses to these incidents and provided insight into how the profession can mitigate racism and promote diversity and inclusion. Conclusions: Participants described interpersonal racism often mediated by location and accent and experiences of internalized racism causing self-doubt, but they most commonly detailed institutionalized racism. PT was experienced as being infused with Whiteness, which participants typically responded to by downplaying or ignoring. The findings from this study can be used to stimulate conversations in the Canadian PT community, especially among those in leadership positions, about not only acknowledging racism as an issue but also taking action against it with further research, advocacy, and training.

Key Words: ethnic groups, minority groups, race, race relations, qualitative research

Abstract

Objectif : explorer les points de vue des physiothérapeutes racialisés du Canada au sujet du racisme qu’ils vivent dans leurs fonctions de physiothérapeute. Méthodologie : étude transversale qualitative et descriptive faisant appel à des entrevues individuelles semi-structurées. Les chercheurs ont organisé les données à l’aide du logiciel d’analyse qualitative NVivo et les ont analysées au moyen de codage inductif et déductif conforme à la méthodologie DEPICT en six étapes. Résultats : douze physiothérapeutes canadiens agréés (quatre hommes et huit femmes, trois de milieu rural et neuf de milieu urbain, de divers groupes racialisés) ont décrit les expériences de racisme institutionnalisé, personnel et intériorisé qu’ils ont vécues dans leurs fonctions de physiothérapeutes. Ces expériences ont été façonnées par leurs caractéristiques personnelles, y compris l’accent, le lieu géographique et le pays de formation en physiothérapie. Les participants ont décrit leur réponse à ces incidents et ont donné leur point de vue sur ce que peut faire la profession pour limiter le racisme et promouvoir la diversité et l’inclusion. Conclusion : les participants ont indiqué que le racisme interpersonnel est souvent fonction du lieu et de l’accent et que les expériences de racisme intériorisé provoquent des remises en question, mais ils ont surtout décrit des situations de racisme institutionnalisé. La physiothérapie était vécue comme imprégnée par le Blanc, et les participants y réagissaient généralement en banalisant cette réalité ou en en faisant abstraction. Les observations tirées de la présente étude peuvent contribuer à stimuler les échanges dans la communauté canadienne de la physiothérapie, particulièrement entre les personnes en position d’autorité, afin que le racisme soit non seulement considéré comme un problème, mais également que des mesures soient prises pour le contrer grâce à d’autres recherches, des prises de position et des formations.

Mots-clés : groupes ethniques, groupes minoritaires, race, recherches qualitatives, relations interraciales

Racism is routinely discussed in the health care field,1–5 but it has received little attention in the Canadian physiotherapy (PT) community. Racism, oppression, and diversity were addressed in the recent “Diversity in Practice” issue of the Canadian Physiotherapy Association’s (CPA’s) Physiotherapy Practice magazine;6 however, no known peer-reviewed literature has explored the impacts of racism on physiotherapists in Canada. At a time when equity, diversity, and inclusion are becoming core themes in health care education and practice, there is a lack of research on diversity and racism in the PT profession itself to act as a guide.

The limited amount of research on racism in PT that has been conducted has occurred in the United Kingdom and the United States. A study in the United Kingdom that interviewed both racialized and White physiotherapists (N = 22) described how they perceived a lack of ethnic diversity in the profession and viewed it as a “White profession.”7 In a national UK survey, 65% of respondents viewed racialized groups as being underrepresented at senior levels in PT, and 72% of non-White respondents indicated that minority groups experience barriers to career progression.8 Two additional studies conducted in the United Kingdom (N = 48) and the United States (N = 83) found indications of racial bias favouring White students over racialized students and a Black student,9, 10 respectively. A US survey found that clinical instructors expected higher clinical performance from PT students from the majority group (individuals with a Caucasian ethnic background) than from students from minority groups, a finding that suggests overt racial bias.10

In Canada, Beagan explored how racism was understood and experienced in medical school.11 She found that students from racialized minority groups experience everyday racism,11 including having difficulty fitting in, feeling less likely to experience the same advantages as White students, and being exposed to frequent racist jokes from patients and classmates.11 Another qualitative study of 76 Canadian nurses found that Indigenous nursing students “observed and detected racism from individuals, groups and processes within [the] schools, hospitals and community placements”;12(p. 693) some even experienced hurtful, disrespectful treatment from the nurse educators. In another study, Indigenous nurses described manifestations of both subtle and overt racism.13 The issues raised in these studies have not been explored empirically in the Canadian PT context.

Moreover, no national statistics on race are collected by the PT profession in Canada. However, in examining occupational classifications by visible minority and Aboriginal status using Statistics Canada data, an estimated 18.7% (n = 4,535) of 24,195 total physiotherapists in Canada identify themselves as a visible minority. A further 1.3% of physiotherapists identify themselves as Aboriginal (n = 315). This means that 20% of Canadian physiotherapists identify as a visible minority or as Aboriginal. These proportions compare with the 22.3% of the total Canadian population who self-identify in the census as a visible minority and the 4.9% who declare Aboriginal identity, for a total of 27.2%.14, 15

Conceptual Framework: Race, Racism, and Racialization

In this study, we use the term racialized instead of terms such as visible minority (as used by Statistics Canada), racial minority, or people of colour to recognize that race is a social and not a biological construct.16–18 By racialized groups, we mean non-dominant ethno-racial (i.e., non-White) communities who, via the process of racialization, experience race as a key factor in their identity and experience of inequality.19 Racialization is the social process of “judging, categorizing, and creating difference among people” to establish and justify socially created hierarchies based primarily on physical characteristics in relation to Whiteness.17(p.5) In other words, it is “the process by which societies construct races as real, different and unequal in ways that matter to economic, political and social life.”20 Racism is “an ideology that either directly or indirectly asserts that one group is inherently superior to others.”20

In this study, we use Jones’s framework,16 which conceptualizes racism at three levels: (1) institutionalized, (2) personally mediated, and (3) internalized. Jones defined institutionalized racism as “differential access to the goods, services and opportunities of society by race,”16(p.1212) which manifests in society as differential access to both material conditions (e.g., access to quality education, housing, employment, medical facilities, and a clean environment) and power (e.g., access to information, wealth, and organizational infrastructure or lack of voice including voting rights, representation in government, and control of the media).16 Jones stated that institutionalized racism is the most fundamental of the three levels and emphasizes its role in constructing the initial entrenched structural barriers and societal norms that directly affect the two other levels of racism.16

Personally mediated racism is defined as prejudice and discrimination according to one’s race, regardless of the perpetrator’s intention, and it can be subtle or overt.16 Prejudice refers to assumptions about others based on race; discrimination is defined as differential actions and behaviours toward others according to their race.16 Personally mediated racism manifests as lack of respect (e.g., poor or no service), suspicion (e.g., shopkeepers’ vigilance, everyday avoidance, purse clutching), devaluation (e.g., surprise at competence), and dehumanization (e.g., police brutality, hate crimes). This level of racism reflects and maintains the structural barriers and power imbalances created by institutionalized racism.16

The third level, internalized racism, is the acceptance of negative messages by members of stigmatized groups about their own abilities and self-worth, including embracing Whiteness (e.g., use of hair straighteners and bleaching creams, stratification by skin tone within racialized communities), devaluation of self (e.g., racial slurs as nicknames, rejection of ancestral culture), and helplessness and hopelessness (e.g., dropping out of school, engaging in risky health behaviour).16 Jones explained that internalized racism reflects the systems of privilege and the collective societal values that are deeply rooted at the institutionalized level.16

It is well known that experiences of racism can also be shaped by other aspects of social identity, including gender, class, ability, religion, sexual orientation, and geographical location.21–23 These social identities, also known as social locations, can be defined as the groups to which people belong because of their place or position in history and society. Hence, in addition to using Jones’s framework, we also use the concept of social locations to further investigate the complexities in the experiences of racism.

Racism has been investigated in medicine and nursing in Canada,11–13 as well as in the PT profession in other countries.7, 8, 24 However, there has been no empirical research on racism in the Canadian PT community. Given that approximately one-fifth of physiotherapists in Canada self-identify as a visible minority or Aboriginal,14–15 and considering the experiences of racism described by racialized physiotherapists in other countries, as well as those in other health care professions in this country, it is crucial to investigate racism in the context of PT in Canada. Guided by Jones’s framework,16 we aim to better understand the impact of racism on racialized physiotherapists in Canada to stimulate conversation and action to mitigate harm and guide the PT profession to greater maturity.

The objective of this study was to explore the perspectives of racialized physiotherapists in Canada on their experiences of racism in their roles as physiotherapists. Specifically, we aimed to explore (1) experiences of institutionalized, internalized, and personally mediated levels of racism; (2) the strategies that the participants used to manage their experiences of racism; and (3) the influence, if any, of their social locations (e.g., social identities including gender, education, accent, geographical location) on their experiences of racism.

Methods

In this qualitative study, we used a critical social science approach25 to shine a light on systems of inequality and on racism in particular. Following this orientation, we used an interpretivist approach to collect and analyze the data provided by soliciting rich and nuanced narratives from participants about their experiences and to analyze these narratives by looking for patterns across the interviews. This study was approved by the research ethics board at the University of Toronto; all participants provided informed consent.

Participants and recruitment

Inclusion criteria for this study were physiotherapists who (1) were licensed and resided in a province or territory of Canada (participants did not have to be educated in Canada), (2) were English speaking, and (3) identified as racialized. We defined racialized physiotherapists as those who identified themselves as non-Caucasian or non-White, including but not limited to people who identified as Indigenous, non-White, because of the colour of their skin (e.g., Black or Brown) or non-White associated with non-European place of origin or ancestry (e.g., Africa, Asia, or Latin America). Self-identifying as having had experiences of racism was not an inclusion criterion. There were no exclusion criteria related to years of practice or area of practice (e.g., participants could be clinicians, researchers, or managers). In addition to the inclusion criteria, we sought to ensure heterogeneity by recruiting a minimum of two Indigenous participants (First Nations, Inuit, or Metis),26 two Black participants, and two male participants.

We used purposive and snowball sampling to recruit participants. A total of 28 targeted invitations were sent by email to individuals who potentially met the inclusion criteria as identified through our professional networks. The invitations included our inclusion criteria and a brief description of the study methods. Interested participants who met the inclusion criteria contacted us, and we then provided them with a consent form and arranged an interview.

Data collection

The interview guide was piloted with racialized PT students. The interviews were conducted by two members of the research team (SV, AM), one who identified as racialized and the other who identified as White. Each interview began with closed-ended questions to obtain demographic information; the interviewer then followed a semi-structured interview guide using open-ended questions about (1) the participant’s experiences with racism as a physiotherapist, (2) the coping strategies that he or she developed to deal with these experiences, and (3) other aspects of the participant’s identity that he or she perceived as contributing to these experiences. One-on-one interviews were conducted in person or by phone and lasted 45–60 minutes. The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and quality checked by the interviewer for accuracy. The transcripts were also de-identified at this stage.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed by all members of the research team using the DEPICT approach for collaborative qualitative analysis, which consists of six steps: dynamic reading, engaged codebook development (organizing the data into a large group format to create, understand, and refine sub-categories), participatory coding (reviewing and coding original de-identified transcripts), inclusive reviewing and summarizing of categories, collaborative analyzing, and translating.27 After transcribing the interviews, we inductively developed a coding framework based on ideas recurring in the interviews (Steps 1 and 2), which we piloted on two transcriptions to refine our code descriptions.

Once the final codebook was developed, the data (original de-identified quotes) were coded (Step 3) into categories and organized using NVivo, Version 10 (QSR International, Cambridge, MA). The team reviewed the coded data and created descriptive summaries (Step 4, generating a list of quotes associated with each category). The descriptive summaries and the associated original quotes were then collaboratively and inductively analyzed (Step 5) to develop the comprehensive themes and sub-themes presented here.

Reflexivity

Reflexivity is a researcher’s self-reflection and critique of his or her own biases and assumptions and how these may have influenced the research process. The study team consisted of five senior PT student researchers (three of whom identified as White, one as Brown, and one as Chinese) and two PT faculty advisors (one of whom identified as Black and one as White). For this study, it was crucial for all team members to consider how their approach to study design, data collection, interpretation, and analysis was shaped by their social locations, experiences, assumptions, and backgrounds. This was particularly important for the two senior PT student interviewers, one of whom self-identified as a Brown man and one who self-identified as a White woman. For instance, when making sense of the data, we explicitly considered how the interviewers’ physical appearance, perceived background, or personal reactions might have influenced the participants’ narratives. Throughout the study, from the first meeting to the last, the team committed itself to engaging in ongoing learning about racism and the ways in which this system of inequality is entrenched in the day-to-day fabric of people’s lives.

Results

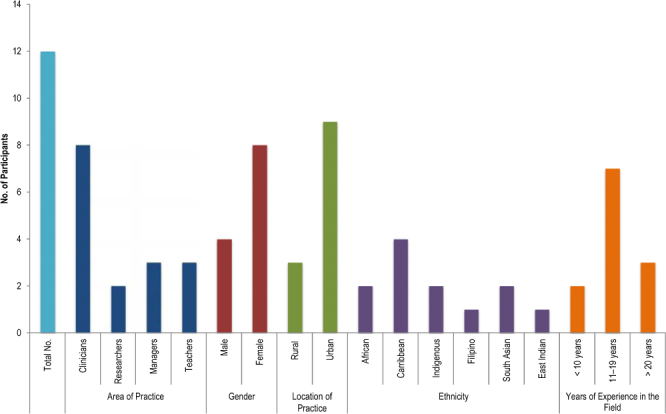

We interviewed 12 licenced physiotherapists from across Canada for this study: 4 men and 8 women. Nine participants were from urban settings (with a population of at least 1,000 and a density of 400 or more people per square kilometre) and three were from rural areas (with a population <1,000).28 Participants reflected a variety of racialized groups (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participant demographic data.

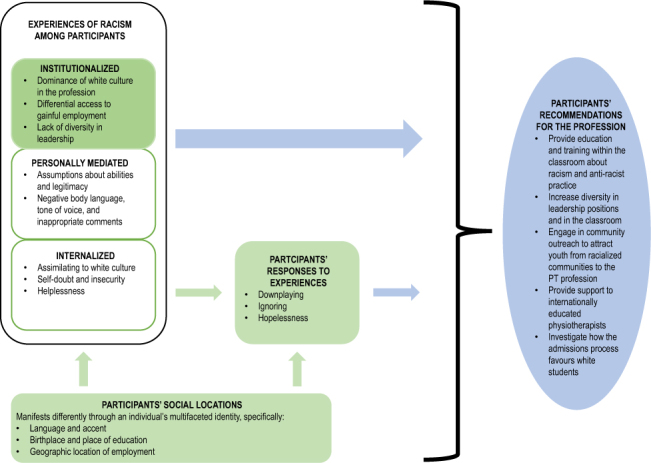

Although each participant had unique experiences to share, as a whole their experiences of being treated differently and inequitably fit into Jones’s three levels of racism.16 Participants also described how their experiences of and responses to racism were shaped by their social locations, especially accent, education, and geographical location. Moreover, participants suggested actions that the PT profession could take to address racism and promote diversity. These findings are depicted in Figure 2 and described next.

Figure 2.

Participants’ perspectives on their experiences of racism in physiotherapy.

Participants’ experiences of racism

The participants’ experiences of being treated differently and inequitably can be broken down into Jones’s three levels of racism.16

Institutionalized racism

The participants described how racism was entrenched in the systems and structures that underpinned PT, including the lack of diversity in PT leadership roles. One participant explained,

Where I see more signs of racism is not necessarily dealing with clients, but when you look at the structure of the organization, like the manager, the head of departments; whether it’s in teaching or in the hospital, they’re rarely minorities.

One participant explained that “historically, people feel that Whites are superior.” This sentiment was echoed by other participants, who also noted that racialized physiotherapists in Canada needed to assimilate into a “White profession.”

The Indigenous participants described experiencing far-reaching institutionalized racism, including a significant lack of access to resources, jobs, and places in university programmes. They described being at a disadvantage when they entered the profession because of the Western orientation of PT, which was also reflected in admissions processes. One participant explained that “in our assessment tools, we are taught to look at things as whether they’re normal or not normal; we address the things that are not normal,” linking to the idea that in PT, anything outside the White norm was considered abnormal. Another participant explained,

Most individuals who enter the profession are expected to assimilate into the profession, and the cultural identity of our profession isn’t a racialized one. Therefore, if the expectation is assimilation, um, you know, we don’t as a profession accommodate much. … We don’t really think about accommodation for race.

Personally mediated racism

Prejudice and discrimination were revealed in the assumptions about the participants’ abilities and legitimacy and in overt comments that came from multiple sources, including both patients and colleagues. Several participants described patients’ negative body language or tone of voice when they walked into a patient’s room. In one example, a patient declined to be seen by the physiotherapist (participant in this study) on hearing the physiotherapist’s name. Participants described dealing with patients’ and colleagues’ assumptions based on their race, including assumptions about a lower skill level, diminished ability to build rapport with patients, and limited capacity for leadership. Several participants described situations in which they were not believed to be a physiotherapist or in a leadership position. One participant who is a senior executive explained,

I went to meet with one of the physician chiefs at the hospital, and I was the only person in the waiting room. I had gone up to his administrative assistant and identified myself and confirmed that I had an appointment with this physician, for this time. And, he came out, about 5 minutes later, and she said, “Yes, [name of participant] is in the waiting room.” He came into the waiting room, looked at me, and left. And went back to his administrative assistant who was just around the corner. I heard him say, “She’s left, she’s not there.” And she came out and looked, and said, “She’s sitting right there.” And he was visibly shocked that it was, that I was who I am.

Others described inappropriate comments from patients:

I said hello and introduced myself, and he introduced himself and then he’s like, “Oh, can I call you Slumdog Millionaire?” Umm, like it was just a joke. I took it lightly … but I mean obviously that was completely and totally racist because I was of Brown skin.

Most experiences described behaviours of individuals who were White; however, one Black participant described a time when his patient who was also Black asked to be treated by a White physiotherapist, indicating the patient’s internalized racism.

Internalized racism

Participants often described experiences of self-doubt, insecurity about competency, and experiences of not fitting in. When describing working in a setting with predominantly White patients and colleagues, one participant remarked,

It’s just you are definitely aware of it. … I don’t know if it stems from like a deep-seated insecurity about being a coloured person, but I think you’re always wondering about, umm, do they see you as different?

Another participant described an experience of self-doubt about her own accomplishments.

This is going to sound bad, but sometimes I wonder, did I get hired here because they wanted to fill a minority gap? … Or any position I ever get for anything, I’m always like, well, I probably got it because they needed a Brown person [laugh]. Like, you feel a little bit like maybe you weren’t 100% qualified.

A number of participants described feeling that they needed to willingly adopt White culture, image, and norms to fit into the profession. One participant explained, “This is gonna sound weird, but I guess I would just pretend I am White in a sense.”

Some participants, especially internationally trained racialized physiotherapists, expressed feelings of hopelessness about attaining reputable jobs in the private practice and hospital settings. These participants stated that White physiotherapists typically dominated these jobs, and as a result, some racialized physiotherapists resorted to applying only for jobs in rural environments and community positions such as long-term care.

Overall, these accounts may have reflected internalized racism, whereby individuals have taken on the assumptions of inferiority based on race. However, they may also reflect strategies that the participants have intentionally adopted to counter personally mediated and institutionalized racism in their work.

Influence of participants’ social locations

The participants described how their experiences of racism were frequently shaped by other aspects of their identities. Participants who did not have a European-Canadian accent perceived more frequent experiences of racism than their racialized colleagues who had a European-Canadian accent (i.e., “no accent”). When comparing accents, one participant noted,

Well, there are definitely some accents, um, I mean, I don’t want to say on a hierarchy, but sort of on a hierarchy … there are definitely accents coming from more racialized communities that are a little bit more frowned upon, Caribbean accents, different African accents, um sometimes Arabic accents.

Other participants echoed this “hierarchy” and remarked that a European-Canadian accent and a British accent were often deemed to be superior. The participants frequently remarked that accents were perceived differently, based on their origin, and that they could shape people’s biases and assumptions positively or negatively based on the accent’s location in this hierarchy. One participant noted that many racialized physiotherapists chose to take language classes to reduce their accent.

Participants born outside Canada believed that they experienced more issues in the workplace than those who were born in Canada, primarily because of their accent and their ability to navigate the health care system. Those who were racialized and educated outside Canada believed that they were at a further disadvantage when applying for jobs because some employers questioned their integrity. In applying for a position, one participant was told, “Next time you’re in India you need to get documents [transcripts] in person. You can’t have your school mail them to us because they’re most likely forged.” Many participants thought that urban environments were more diverse than rural ones and that in a rural environment patients exhibited more of a shock factor when treated by racialized physiotherapists. One participant compared his employment experience between urban and rural environments: “People [would] not make much contact, considering I am the director. … It’s a very interesting dynamic that I don’t necessarily experience anywhere else except for in that [rural] region.”

Responses to incidents of racism: downplaying, ignoring, and hopelessness

The participants discussed a range of responses and reactions to experiences of racism. In most instances, they chose not to acknowledge or act on their experiences at that moment and refrained from engaging in conversation with the individuals who had mistreated them. The reasons they gave included being unsure whether their perception of the racism was legitimate, thinking the experience was not a “big enough deal” to address, or worrying that responding might cause more harm than good for their employers. Others explained that they had elected to ignore the racism because such events were so common, and they assumed that their actions would be futile in creating change. Others reflected on the insidious nature of racism: “It [racism] is not blatant, it’s very subtle. And it’s harder to deal with when it’s subtle. At least when it’s out there, you can have a conversation.” This inaction left many participants feeling conflicted because they described how their parents had encouraged them to use instances of discrimination as an educational moment with the perpetrator.

When asked whether they had spoken to colleagues in their workplace or professional PT associations, in all instances participants answered no. When asked whether they would approach their institution for support, one participant expressed fear of negative ramifications: “I don’t, I wouldn’t broach that. That would be like … almost like, suicide … political suicide. … It’s not, it’s not going to help me.” When participants did reflect openly about an experience, it was typically with other racialized colleagues, friends, and family. “When it came to like things about race, I only felt comfortable talking about it to my other friends of colour who worked in the hospital.”

However, many participants suggested that they would be more likely to seek guidance if they thought that their work environment was open to conversations about race. One participant stated that she would be more likely to speak to her manager if the manager were also racialized.

Participants’ recommendations for the profession

The participants perceived PT as a White-dominant profession in need of far greater diversity, particularly among students, teaching faculty, and leadership positions at the provincial and federal levels. They thought that increasing diversity in the profession would better reflect the diversity of the client population, thereby leading to better patient-centered care. One participant noted,

I think Canada in general, with so much of our population being immigrants, we have a huge population [of people of colour] and, if you try to work with them like they’re White, you’re going to miss stuff. You’re going to miss things or you’re going to not understand, or you’re not going to be able to provide this client-centered care that we’re always talking about and how it should be specific to these clients.

Many participants remarked that the majority of leaders in the profession, including those in professional associations, were White. When asked whether they felt at a disadvantage when searching for jobs, many participants did not think this was an issue. However, on one occasion when a participant was interested in applying for a leadership position, she was repeatedly told by her White manager that there was no role for her in the hospital other than as a bedside physiotherapist, whereas another manager who was Black encouraged her to apply. The participants suggested that it would be easier to talk about diversity and inclusion if people in positions of power could better relate to the experiences of racialized physiotherapists. Some suggested that the issue of diversity begins in the classroom, where there seems to be fewer racialized than White students; Black and Indigenous individuals are particularly underrepresented. One participant, self-identifying as Black, noted, “When you look at the structure of the physio [profession] or even your physio class, there are not a lot of people who look like me.”

The majority of participants noted that there was insufficient discussion of diversity, equity, and racism in the profession. However, the participants also identified efforts to raise awareness of this issue; for example, the CPA includes people who are racialized in its promotional and educational materials (i.e., using names of racialized physiotherapists in online articles and case studies) and produced a diversity issue of its monthly magazine. The participants discussed ways in which the profession’s governing bodies could create a more equitable and inclusive work environment, including (1) providing outreach to diverse communities and schools to promote the recruitment of diverse students (particularly Indigenous students) into PT programmes, (2) providing support to internationally educated physiotherapists, (3) validating the concerns about racism raised by racialized physiotherapists and creating safe environments for these concerns to be raised, and (4) promoting conversations on race, racism, diversity and inclusion in the profession.

Discussion

This is the first empirical study to explore experiences of racism in the Canadian PT profession. Previous literature on racism in PT has been conducted in the United Kingdom and the United States,7–10,24 and consistent with the findings of Yeowell,7 the narratives of our participants suggest that they view PT as a White-dominant profession with insufficient inclusion of diverse peoples and worldviews. Many participants described a PT profession that often demands that its practitioners assimilate into a White culture and norm. This phenomenon, described as institutional Whiteness, reflects a process by which institutions take form and shape through generations of decisions about the allocation of resources, recruitment, and the creation of structures and norms to reproduce an institution that primarily reflects White ideals.29 This idea aligns with Jones’s institutionalized level of racism,16 which describes how racism is incorporated into the structure of society, producing personally mediated racism among (often well-intentioned) individuals.

Using Jones’s three-level framework of racism to analyze the perspectives and voices of our participants has allowed us to understand the complexities of racism and how it functions on multiple levels in the Canadian PT profession.16 Notably, many participants, directly or indirectly, voiced concerns about the deep and engrained barriers and societal norms created by institutionalized racism that inherently disadvantage racialized physiotherapists in Canada. The participants voiced numerous examples of institutionalized racism, including day-to-day inequities and differential access to opportunities in education, services, employment, and leadership positions. These insights reinforce the importance of recognizing that racism is not merely a set of incidents between individuals (e.g., discrimination or prejudice at the personally mediated level of racism), it also manifests in deeply rooted structural and systemic inequities (e.g., institutionalized racism), suggesting that a mandatory step in addressing racism in PT is to tackle institutional racism. One approach to mitigating and unravelling the workings of institutionalized racism is using anti-racism theory.

According to the Canadian Race Relations Foundation, anti-racism is the active and consistent process of change to eliminate individual, institutional, and systemic racism.30 As an approach, anti-racism acknowledges that systemic racism exists, and it confronts the unequal power dynamic between groups of people and in the structures that sustain it.31 To advance racial equity, Ontario’s Anti-Racism Directorate was established in 2016 to lead the government’s anti-racism initiatives by working to identify, address, and prevent systemic racism in government policy, legislation, programmes, and services. As a result of this initiative, the province passed the Anti-Racism Act in 2017.32

Using the anti-racism approaches that have recently been initiated in government policy, legislation, and services and mirroring the suggestions of our participants, we propose three calls to action for the PT profession in Canada: training, advocacy, and research.

Training

To better educate current and future physiotherapists on the topics of diversity, equity and inclusion, we advocate that curricula on anti-racist practice be integrated into PT programmes across Canada.35 The Ontario Ministry of Education has recently begun this process by implementing the Equity and Inclusive Education Strategy, which aims to help educators identify and address discriminatory biases and systemic barriers.31 As voiced by our participants, implementing education and training at the root of our profession may be the most beneficial way to address and prevent the inequities related to race in the classroom. We invite educators and faculty members to consider how they can add training on this topic (e.g., training materials, resources, inclusive classroom practices) to ensure that a school’s culture and practices resist and dismantle, as opposed to reproduce institutional racism.

Advocacy

The Anti-Racism Directorate estimates that racialized individuals will make up 48% of the population of Ontario by 2036.33 With this in mind, we invite the leaders of our profession to advocate for safe environments in our institutions where discussions about race, culture, and diversity are encouraged. As the participants in our study emphasized, there remains a lack of diversity in both the educational system and leadership positions in our profession. Their concern about the lack of racialized individuals in leadership roles in PT echoes findings from the United Kingdom that racialized individuals are poorly represented in senior roles and face barriers to career progression.8

We invite faculty members in PT programmes and policy-makers to advocate for equitable access for prospective racialized students to PT programmes as well as increased access for current racialized physiotherapists to positions of leadership. Specifically, by recognizing that our profession is historically and currently predominantly White, faculty members should develop outreach strategies to create a more representative sample of prospective physiotherapists to reflect the growing number of racialized individuals in Canada. As suggested by our participants, we strongly recommend outreach and communication strategies for our Indigenous population and prospective students.36

Those who are racialized should be recognized for their expertise on racism and consulted about how to advance much-needed action to mitigate racism in the profession and, for our patients, as a determinant of health. Mentoring, promoting, and electing more members of racialized groups to positions of leadership throughout the PT profession will help mobilize strategic action to address the underpinnings of systemic racism.

Research

As a result of this first study of its kind in the Canadian PT literature, we call for more support for racism-related research and race-based data collection in the field. At a time when discussions about equity, diversity, and inclusion have become mainstays of health care practice and research, the PT profession in Canada lacks empirical data on racism and diversity among its members. Given this preliminary conversation about racism among racialized physiotherapists in our study, future research in the form of national surveys may be warranted to help understand the scope of racism and racial disparities in our profession. This is especially true given the need for evidence-based decision making and to quantitatively study racial disparities in the field. To implement this action, we invite PT organizational bodies in Canada such as the CPA to use the Ontario government’s newly published anti-racism data standards for race-based data collection.34

Future Research

Whereas our study focused on racialized physiotherapists, future research should consider the perspectives of racialized students in their experiences of racism in PT programmes in Canada. This is especially important given Beagan’s findings about the profound impact of everyday racism on medical students in this country.11 In addition, because race is regarded as a significant predictor of the quality of care received by patients,2, 5 future research should examine patients’ viewpoints on racism and diversity in their experiences of PT care. Future research should also explore how to build reflexivity among physiotherapists, especially White leaders in PT, to better understand the multifaceted ways that racism plays out day to day in our profession; this will move us forward in solidarity toward a supportive and inclusive profession for all.

This study had a number of limitations. First, the sample was small, only 12 participants, but they gave us in-depth perspectives and presented information-rich cases that illuminated an issue that has historically been out of view. Second, although we sought to open up ideas and dialogue about racism in PT, studies using this design should not be considered generalizable or definitive on the subject. Third, many viewpoints and experiences of racism were not captured; however, this was not meant to be an exhaustive study of racism in PT, and additional research is urgently needed. Next, the research team consisted of seven physiotherapists or PT students with knowledge and experience of PT and health care; however, no members had a background in race theory (or related domains), which would have been an asset. However, one of the advisors has extensive experience in critical qualitative research and was able to contribute to nurturing reflexivity throughout the research process. Moreover, the interviews were conducted by student researchers with limited prior research experience. Finally, some of the interviews on this sensitive topic were conducted virtually as opposed to in person, which could have compromised the trust and rapport required for an in-depth interview. To mitigate these concerns, the research team and interviewers participated in interview training and a series of pilot interviews as well as rigorous post-interview reflection processes.

Conclusion

The participants described common experiences of interpersonal racism – often mediated by geographical location, language, and accent – as well as experiences of internalized racism, which corresponded with feelings of insecurity and self-doubt. A majority of the participants mentioned how systemic racism manifests in the Canadian PT profession as the inequitable access to employment, leadership positions, and services and a lack of access to power. Moreover, they described a profession that is predominantly White and that demands that racialized physiotherapists assimilate to White norms and ideals. As the first empirical study to examine racism in the Canadian PT field, it highlights the need for further research, anti-racism training in PT curricula, and the pressing need for advocacy on this issue. This study calls for the PT profession, in particular those in leadership positions, to create a safe environment for promoting a discussion of racism and race relations.

Key Messages

What is already known on this topic

The literature investigating racism in health care is extensive, but little literature exists on racism in PT in particular.1–5 The research on this topic that does exist has been conducted in the United Kingdom and the United States, and it has shown that PT is perceived as a White profession with instances of differential treatment of PT students on the basis of race.7–10,24 There have been no empirical studies investigating racism experienced by physiotherapists in Canada.

What this study adds

This is the first study to investigate the experiences of personal, internalized, and systemic racism experienced by racialized physiotherapists in Canada. It takes a multifaceted, intersectional approach to exploring the racism experienced by health professionals who are racialized, suggesting that these experiences may be shaped by their social locations – specifically, accent, birthplace, place of education, and geographical place of employment. Our findings show that we need further engagement on the issue of racism in PT, including further research, training, and advocacy, while also building capacity for reflexivity about Whiteness in a predominantly White profession.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank the participants for sharing their experiences. They also thank Shaun Cleaver, Kelly O’Brien, Nancy Salbach, Karen Yoshida, Cathy Evans, and two anonymous reviewers for their guidance.

Contributor Information

Shrey Vazir, Department of Physical Therapy, University of Toronto, Toronto.

Kaela Newman, Department of Physical Therapy, University of Toronto, Toronto.

Lara Kispal, Department of Physical Therapy, University of Toronto, Toronto.

Amanda E. Morin, Department of Physical Therapy, University of Toronto, Toronto.

Yang (Yusuf) Mu, Department of Physical Therapy, University of Toronto, Toronto.

Meredith Smith, Department of Physical Therapy, University of Toronto, Toronto.

Stephanie Nixon, Department of Physical Therapy, University of Toronto, Toronto.

References

- 1.Peek ME, Odoms-Young A, Quinn MT, et al. Racism in healthcare: its relationship to shared decision-making and health disparities: a response to Bradby. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(1):13–7. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.018. Medline:20403654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson AR, Smedley B, Stith A, editors. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care [Internet]. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2003. [cited 2017 Jul 12]. 10.17226/12875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):20–47. 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. Medline:19030981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shavers VL, Fagan P, Jones D, Klein WMP, Boyington J, Moten C, et al. The state of research on racial/ethnic discrimination in the receipt of health care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):953–66. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300773. Medline:22494002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen FM, Fryer GE, Phillips RL, et al. Patients’ beliefs about racism, preferences for physician race, and satisfaction with care. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(2):138–43. 10.1370/afm.282. Medline:15798040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrion JJD. Imagining an encompassing physiotherapy. Physioth Pr. 2017;7(2). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeowell G. “Isn‘t it all Whites?” Ethnic diversity and the physiotherapy profession. Physioth. 2013;99(4):341–6. 10.1016/j.physio.2013.01.004. Medline:23537883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogg J, Pontin E, Gibbons C, et al. Physiotherapists’ perceptions of equity and career progression in the NHS. Physioth. 2007;93(2):137–43. 10.1016/j.physio.2006.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haskins AR, Rose-St Prix C, Elbaum L. Covert bias in evaluation of physical therapist students’ clinical performance. Phys Ther. 1997;77(2):155–63. Medline:9037216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clouten N, Homma M, Shimada R. Clinical education and cultural diversity in physical therapy: clinical performance of minority student physical therapists and the expectations of clinical instructors. Physiother Theory Pract. 2006;22(1):1–15. 10.1080/09593980500422404. Medline:16573242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beagan BL. “Is this worth getting into a big fuss over?” Everyday racism in medical school. Med Educ. 2003;37(10):852–60. Medline:12974838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin DE, Kipling A. Factors shaping Aboriginal nursing students’ experiences. Nurse Educ Pract. 2006;6(6):380–8. 10.1016/j.nepr.2006.07.009. Medline:19040905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vukic A, Jesty C, Mathews SV, et al. Understanding race and racism in nursing: insights from Aboriginal nurses. ISRN Nurs. 2012;2012:1–9. 10.5402/2012/196437. Medline:22778991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statistics Canada Table 98-400-X2016357: occupation – National Occupationalal Classification (NOC) 2016 (691), employment income statistics (3), highest certificate, diploma or degree (7), Aboriginal identity (9), work activity during the reference year (4), age (4D) and sex (3) for the population aged 15 years and over who worked in 2015 and reported employment income in 2015, in private households of Canada, provinces and territories and census metropolitan areas, 2016 census – 25% sample data [Internet]. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2016. [cited 2018 June 1]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/98-400-X2016357. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Statistics Canada Census profile, 2016 census [Internet]. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2017. [cited 2018 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–5. Medline:10936998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ontario Human Rights Commission Policy and guidelines on racism and racial discrimination [Internet]. Toronto: The Commission; 2005. [cited 2016 Sep 27]. Available from: http://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/policy-and-guidelines-racism-and-racial-discrimination. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Block S, Galabuzi G-E. Canada’s colour coded labour market: the gap for racialized workers [Internet]. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives; 2011. [cited 2016 Oct 1]. Available from: http://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2011/03/Colour%20Coded%20Labour%20Market.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galabuzi G-E. Canada’s economic apartheid: the social exclusion of racialized groups in the new century [Internet]. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2006. Available from: https://www.cspi.org/books/canada-s-economic-apartheid. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ontario Human Rights Commission Racial discrimination, race and racism (fact sheet). Toronto: The Commission; [Internet]; n.d. [cited 2018 Aug 6]. Available from: http://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/racial-discrimination-race-and-racism-fact-sheet. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dick S, Hunt-Humchitt S, John R, et al. Cultural safety: module two – peoples’ experiences of oppression [Internet]. Available from: http://web2.uvcs.uvic.ca/courses/csafety/mod2/glossary.htm#Q. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abu-Ras WM, Suarez ZE. Muslim men and women’s perception of discrimination, hate crimes, and PTSD symptoms post 9/11. Traumatology. 2009;15(3):48–63. 10.1177/1534765609342281 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patten E. The black-white and urban-rural divides in perceptions of racial fairness [Internet]. Washington (DC): Pew Research Center; 2013. [cited 2018 May 3]. Available from: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/08/28/the-black-white-and-urban-rural-divides-in-perceptions-of-racial-fairness/. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams A, Norris M, Cassidy E, et al. An investigation of the relationship between ethnicity and success in a BSc (Hons) Physiotherapy degree programme in the UK. Physioth. 2015;101(2):198–203. 10.1016/j.physio.2014.08.003. Medline:25293982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eakin J, Robertson A, Poland B, et al. Towards a critical social science perspective on health promotion research. Health Promot Int. 1996;11(2):157–65. 10.1093/heapro/11.2.157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crown–Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada Indigenous peoples and communities [Internet]. Ottawa: CINAC; 2017. [cited 2018 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100013785/1529102490303. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flicker S, Nixon SA. The DEPICT model for participatory qualitative health promotion research analysis piloted in Canada, Zambia and South Africa. Health Promot Int. 2015;30(3):616–24. 10.1093/heapro/dat093. Medline:24418997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Statistics Canada From urban areas to population centres [Internet]. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2017. [cited 2018 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/eng/subjects/standard/sgc/notice/sgc-06. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed S. A phenomenology of whiteness. Fem Theory. 2007;8(2):149–68. 10.1177/1464700107078139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Canadian Race Relations Foundation Glossary of terms [Internet]. Toronto: The Foundation; 2015. [cited 2018 Sep 6]. Available from: http://www.crrf-fcrr.ca/en/resources/glossary-a-terms-en-gb-1/item/22793-anti-racism. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ontario A better way forward: Ontario’s 3-year anti-racism strategic plan [Internet]. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2017. [cited 2018 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/page/better-way-forward-ontarios-3-year-anti-racism-strategic-plan. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ontario Anti-Racism Act, 2017, SO 2017, c 15 [Internet] [cited 2018 June 1]. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/17a15.

- 33.Ontario Anti-Racism Directorate [Internet]. Toronto: The Directorate; 2016. [cited 2018 Sep 10]. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/page/anti-racism-directorate. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ontario Data standards for the identification and monitoring of systemic racism. [Internet]. Toronto: Government of Ontario; 2018. [cited 2018 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/document/data-standards-identification-and-monitoring-systemic-racism. [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGibbon EA, Etowa JB. Anti-racist health care practice. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cox J, Kapil V, McHugh A, et al. Build insight, change thinking, inform action: considerations for increasing the number of indigenous students in Canadian physical therapy programmes. Physiother Can. 2019;71(3):261–9. 10.3138/ptc.2018-14.e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]