Abstract

There is little information concerning the predictive ability of the preoperative platelet to albumin ratio (PAR) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients after liver resection. In the current study, we aimed to assess the prognostic power of the PAR in HCC patients without portal hypertension (PH) following liver resection.

Approximately 628 patients were included in this study. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to evaluate the predictive value of the PAR for both recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS). Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to identify the independent risk factors for both RFS and OS.

During the follow-up period, 361 patients experienced recurrence, and 217 patients died. ROC curve analysis suggested that the best cut-off value of the PAR for RFS was greater than 4.8. The multivariate analysis revealed that microvascular invasion (MVI), tumor size >5 cm, high aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet count ratio index (APRI) and high PAR were four independent risk factors for both RFS and OS. Patients with a low PAR had significantly better RFS and OS than those with a high PAR.

The PAR may be a useful marker to predict the prognosis of HCC patients after liver resection. HCC patients with a high preoperative PAR had a higher recurrent risk and lower long-term survival rate than those with a low preoperative PAR.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, liver resection, platelet to albumin ratio

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common malignancy and third most frequent tumor-related death in the world.[1] Every year, approximately 800,000 new HCC patients are diagnosed.[1] Unfortunately, death is almost the same due to the aggressive biological behavior of HCC.[1] Liver resection is widely accepted as a curative treatment for HCC. Although advances in surgical technology and perioperative management have been achieved, the long-term survival of HCC patients after liver resection is still not satisfactory due to the high postoperative recurrence rate.[2] Published investigations have suggested that the recurrence rates of patients with HCC may be as high as 50% within the first 3 years and greater than 70% during the first 5 years after surgery.[3,4]

Many factors could influence the outcomes of patients with HCC after liver resection. Recently, systemic inflammation has been confirmed to be involved in carcinogenesis, tumor progression and metastasis of HCC.[5] A number of inflammation-based prognostic models, including the platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), were proposed to predict HCC patients’ prognosis.[6,7] However, there is little information regarding the platelet to albumin ratio (PAR) in HCC patients after liver resection. Published investigations also suggested that preoperative platelet counts and serum albumin levels were associated with patient prognosis after liver resection.[8,9] Low preoperative albumin levels contributed to a high incidence of postoperative complications and recurrence, as well as poor long-term survival for patients with HCC.[9,10] Basic studies have confirmed that platelets could interact with tumor cells, which could promote tumor growth and metastasis.[11,12] Clinical investigations also revealed that platelets are closely correlated with the progression of many malignancies, including HCC.[13–16] PAR is an inflammation-based model that incorporates both platelets and albumin. In this study, we tried to identify whether the PAR is a marker for predicting the prognosis of patients with HCC after liver resection.

2. Patients and methods

Patients with diagnosed HCC within Barcelona clinic liver cancer stage 0/A who received liver resection at our center from 2008 to 2019 were enrolled in this study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: re-resection, ruptured HCC, receipt of preoperative antitumor treatment, a positive surgical margin, and the presence of other types of tumors. All HCCs were confirmed by postoperative pathology. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. This study was approved by the ethics committee of West China Hospital of Sichuan University.

2.1. Follow-up

All preoperative blood tests were performed within one week prior to liver resection. After surgery, patients were regularly screened for recurrence every 3 months by monitoring blood cell tests, liver function tests, serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), HBV-DNA tests, and visceral ultrasonography, as well as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging and chest radiography. Bone scintigraphy was performed whenever HCC recurrence was suspected. Before and after surgery, antiviral drugs (entecavir, lamivudine or tenofovir) were conventionally administered to patients with a positive hepatitis B virus-DNA (HBV-DNA) load. Postoperative recurrence was defined as newly local or distant tumors detected by visceral ultrasonography, as well as computed tomography or magnetic resonance with or without an increase in tumor markers or as confirmed by biopsy or resection.[17]

2.2. Definitions

The PAR was calculated as the platelet count (109/L) divided by the serum albumin level (g/L).[18] The NLR was calculated by dividing the absolute neutrophil count by the absolute lymphocyte count.[19] A NLR ≥ 3 was considered as a high NLR.[20] The PLR was defined as the platelet count divided by the lymphocyte count.[19] A PLR ≥ 150 was defined as a high PLR.[20] A preoperative AFP level greater than 400 ng/mL was considered a high AFP level.[17] Aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet count ratio index (APRI) was calculated as [(AST value/ULN)/platelet count (109/L)] x 100.[21] APRI less than 0.5 was considered low APRI, whereas APRI ≥ 0.5 was defined as high APRI.[21] Clinical portal hypertension (PH) was defined as presence of esophageal and gastric varices, and a platelet count <100 × 109/L associated with splenomegaly.[22]

2.3. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21.0 (SPSS Company, Chicago, IL) for Windows. All continuous variables were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance. Univariate analyses for categorical variables were performed using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) rates were calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Multivariable analysis using Cox regression analysis was used to identify independent risk factors for OS and RFS with a backward elimination stepwise approach. All variables with a P value <.2 by univariate analysis were involved in the multivariate analysis. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to evaluate the predictive value of the PAR for both RFS. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) was used to estimate the cutoff value of the PAR. A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

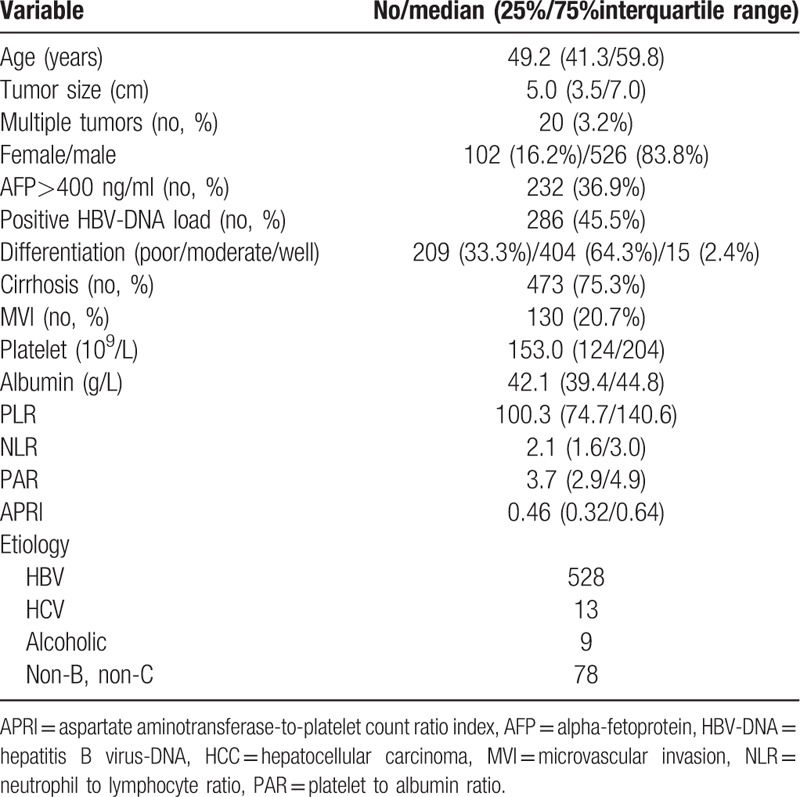

A total of 628 patients were enrolled in this study. The demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 50.9 ± 12.7 years, and the predominance was male (n = 526, 83.8%). Multiple tumors were presented in 20 (3.2%) patients at the time of diagnosis. High preoperative AFP was observed in 232 (36.9%) patients. Microvascular invasion (MVI) was detected in 130 (20.7%) patients. Positive HBV-DNA was identified in 288 (45.9%) patients. The median tumor size was 5.0 cm. The median PAR was 3.7 for all patients.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants.

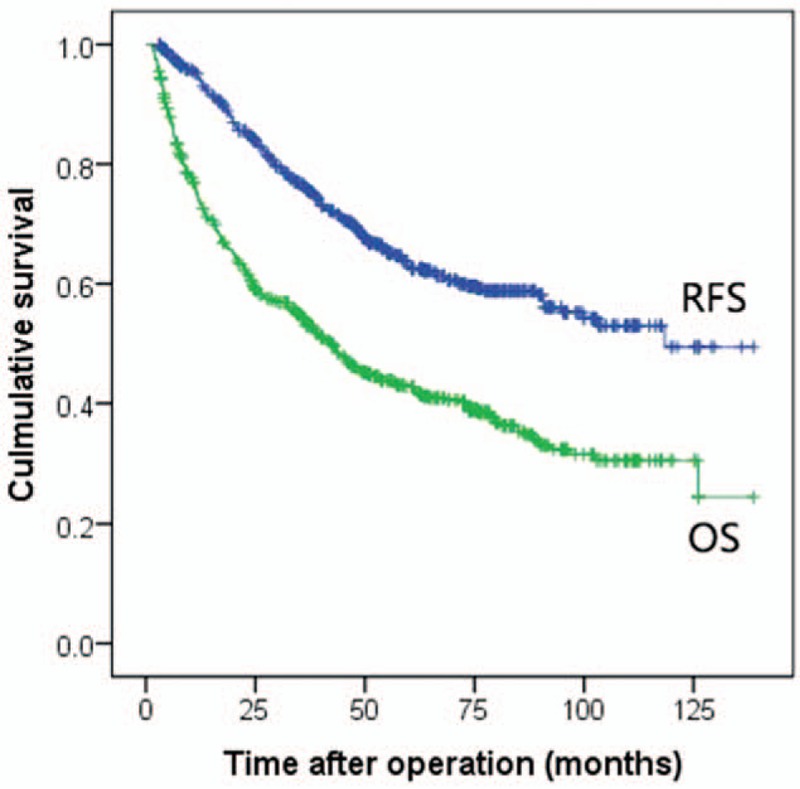

Within a mean of 51.1 ± 31.8 months of follow-up, 361 (57.5%) patients suffered from recurrence, whereas 217 (34.6%) patients died. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS rates were 74.3%, 54.3%, and 42.8%, respectively, for the entire cohort (Fig. 1). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS was 94.4%, 76.6%, and 63.0%, respectively, for the whole cohort (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Receiver operating curve of preoperative platelet to albumin ratio for recurrence-free survival.

3.1. Comparison of the prognosis of HCC patients with high and low PARs

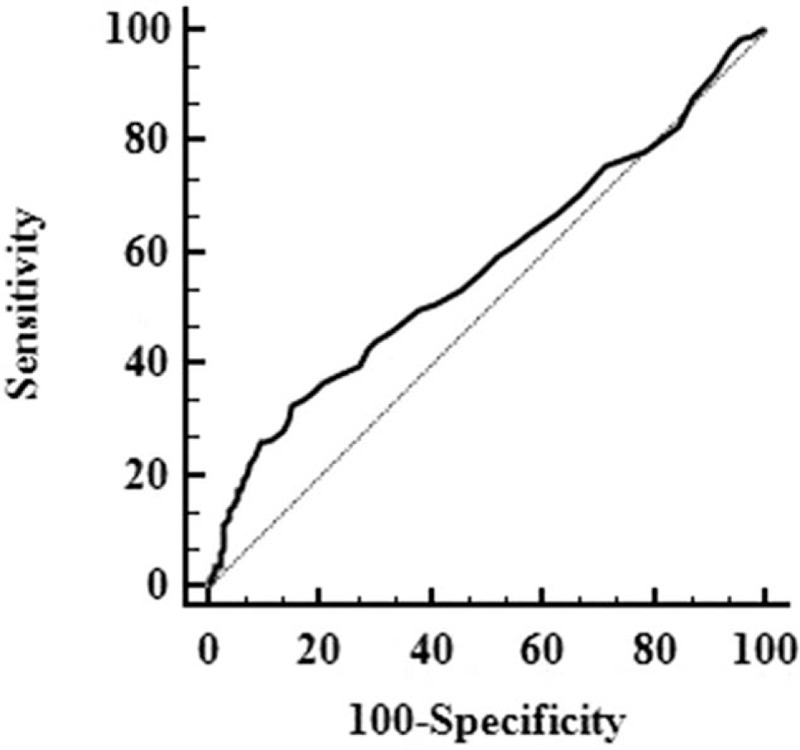

We used ROC analyses to identify the optimal cut-off values of the PAR in predicting postoperative recurrence and survival. As presented in Figure 2, the best cut-off value of the PAR for postoperative RFS was greater than 4.8, with a sensitivity of 33.0% and a specificity of 85.0%. The AUC was 0.577.

Figure 2.

Recurrence-free and overall survival curves of the entire cohort.

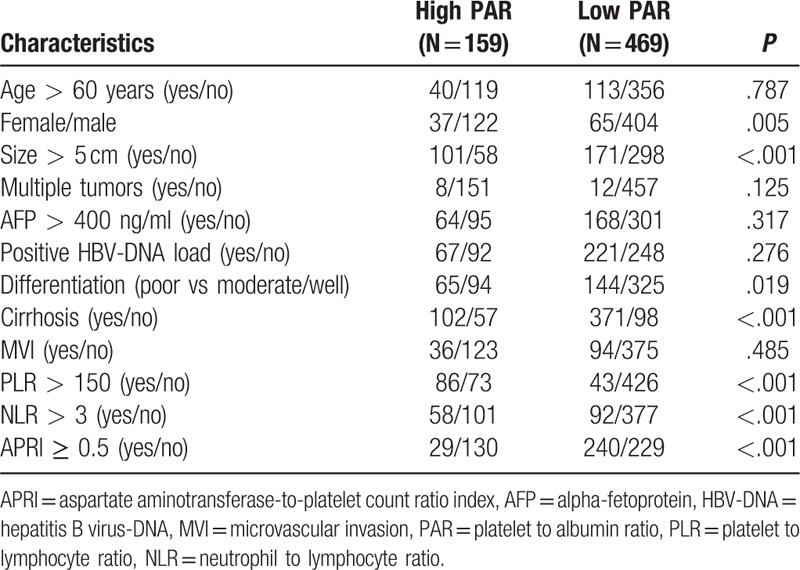

We compared the clinicopathological data of patients with high and low PARs. As shown in Table 2. More female patients, tumor size >5 cm, poor differentiation, high NLR and PLR were observed in patients with high PAR. Whereas, more cirrhosis and low APRI were observed in patients with low PAR.

Table 2.

comparison of clinicopathological characteristics of patients with high and low PARs.

The 1-, 3-, and 5-year RFS of HCC patients with high and low preoperative PARs were 65.9%, 42.2%, and 26.1%; and 77.1%, 58.5%, and 47.3%, respectively (Fig. 3A). The RFS of patients with a low (N = 459) preoperative PAR was significantly better than those with a high (N = 159) preoperative PAR (P < .001). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates were 91.5%, 65.9%, and 49.3%, respectively, in patients with a high (N = 159) preoperative PAR and 95.3%, 79.7%, and 67.7%, respectively, in patients with a low (N = 459) preoperative PAR (Fig. 3B). Statistical differences were observed (P < .001).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the recurrence-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) of patients with a high preoperative PAR and low preoperative PAR. PAR = platelet to albumin ratio.

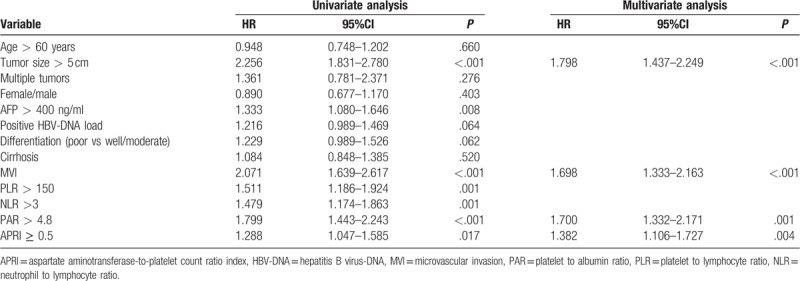

3.2. Univariate and multivariate analyses for RFS

Table 3 lists the results of univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of the predictors of RFS. Univariate analysis revealed that MVI, tumor size >5 cm, poor differentiation, positive HBV-DNA load, AFP > 400 ng/ml, high PLR, high NLR, high APRI and high PAR were potential risk factors for postoperative recurrence. Multivariate analysis confirmed that presence of MVI (HR = 1.698; 95%CI = 1.333–2.163; P < .001), tumor size >5 cm (HR = 1.798; 95%CI = 1.437–2.249; P < .001), high APRI (HR = 1.382; 95%CI = 1.106–1.727; P = .004) and high PAR (HR = 1.700; 95%CI = 1.332–2.171; P = .001) were four independent risk factors for RFS.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic factors for RFS.

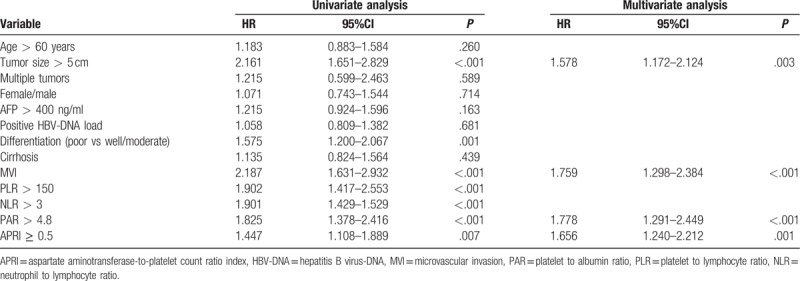

3.3. Univariate and multivariate analyses for OS

Prognostic factors affecting the OS of patients with HCC by univariate and multivariate Cox regression models are displayed in Table 4. Univariate analyses to identify factors significantly associated with postoperative survival found that the poor prognostic factors were poor tumor differentiation, AFP > 400 ng/ml, MVI, NLR, PLR, PAR, APRI and tumor size >5 cm. Among these factors, only presence of MVI (HR = 1.759; 95%CI = 1.298–2.384; P < .001), tumor size >5 cm (HR = 1.578; 95%CI = 1.172–2.124; P = .003), high APRI (HR = 1.656; 95%CI = 1.240–2.212; P = .001) and the high PAR (HR = 1.778; 95%CI = 1.291–2.449; P < .001) were identified as independent prognostic factors by Cox regression analysis.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic factors for OS.

4. Discussion

Recently, many investigations have suggested that the systemic inflammatory response is associated with the prognosis of patients with HCC following liver resection, liver transplantation, and radiofrequency ablation. Some inflammation markers were proven to be predicters of postoperative recurrence and survival, such as the NLR and PLR. However, whether the PAR could contribute to the postoperative outcomes of patients with HCC is not well established. The current study confirmed that a high preoperative PAR adversely impacted HCC patients’ postoperative RFS and OS after liver resection.

A number of investigations have confirmed that thrombocytosis at the time of diagnosis contributes to poor long-term survival in many types of solid tumors.[23–25] The systemic inflammation response and protection from host immune surveillance may be the potential mechanisms of this correlation.[24,25] Stone et al[26] reported that serum thrombopoietin and interleukin-6 were significantly elevated in ovarian cancer patients who had thrombocytosis compared with those who did not. The platelet counts were significantly reduced in both patients with epithelial ovarian cancer and in tumor-bearing mice when using anti-interleukin-6 antibody treatment.[26] Moreover, platelets could guard tumor cells from the attack of the host's immune system and promote their arrest at the endothelium.[27,28] Palumbo et al[29] confirmed that platelets could protect tumor cells from natural killer cell-mediated elimination. Moreover, platelets could also help the tumor cells take over the MHC-1, thereby mimicking host cells and escaping immune surveillance.[28,30] Clinical studies also suggested that high preoperative platelets were associated with poor prognosis of patients with HCC. Xue et al[31] confirmed that high platelet counts increase the incidence of metastasis in patients with huge HCC who received transarterial chemoembolization. Pang et al[8] revealed that preoperative platelet counts greater than 148 × 109/L were related to a high incidence of postoperative recurrence. Zhang et al[12] confirmed that inhibiting platelet function could block tumor metastasis.

In this study, we excluded patients with PH. In patients with PH, the preoperative platelet counts may be very low. In this case, the PAR may also be very low. However, many published studies have suggested that PH is associated with high perioperative complications and poor long-term outcomes.[32,33] Choi et al[32] reported that the 5-year OS of HCC patients with PH who underwent liver resection was 37.9%, which was significantly lower than in those without PH (5-year OS 78.7%). Many studies have also suggested that PH could significantly increase the incidence of postoperative liver failure in HCC patients.[33,34] Recently, a meta-analysis also confirmed that clinical PH could negatively influence both short-term and long-term outcomes of patients with HCC after liver resection.[35] Accordingly, in the present study, we excluded patients with portal hypertension.

Low serum albumin levels could also result in a high PAR. The serum albumin level could reduce the patient's liver function and nutrition status. Hypoalbuminemia was often observed in patients with poor liver function and/or malnutrition. Both preoperative and postoperative poor liver function and malnutrition were confirmed to increase the patient's surgical risk and decrease the patient's long-term survival.[36–39] Moreover, albumin has been proven to have antitumor effects. Bagirsakci et al[40] confirmed that albumin may directly inhibit the growth of HCC, either via modulation of AFP or via its actions on growth-controlling kinases. A systematic review was conducted by Gupta et al[41] to assess the influence of pretreatment albumin on cancers including breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, colorectal cancer, HCC, pancreatic cancer and so on. Finally, Gupta et al[41] confirmed that pretreatment serum albumin levels showed useful prognostic significance in cancer.

There are also some limitations in this study. First, this is a single-center retrospective study. Second, our study confirmed that both RFS and OS of HCC patients with a low PAR were better than those in patients with a high PAR. However, the AUC of the PAR in predicting RFS in the current study is low. Accordingly, the optimal cut-off value of the PAR in predicting the prognosis of HCC patients need further large sample studies. Moreover, platelet counts may be adversely influenced by PH. Although we have excluded all patients with clinical PH. Some patients with severe cirrhosis may also have a relatively low platelet count although they didn’t have clinical PH. Accordingly, the relationship between PAR and RFS/OS maybe not linear. This may also explain why more patients with cirrhosis and high APRI in the low PAR group.

In conclusion, our study confirmed that the preoperative PAR may serve as a surrogate marker to predict postoperative recurrence and mortality in HCC patients without PH following liver resection. HCC patients with a high preoperative PAR had a higher recurrent risk and lower long-term survival rate than those with a low preoperative PAR.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Chuan Li, Li-Ping Chen.

Data curation: Chuan Li, Wei Peng, Xiao-Yun Zhang, Tian-Fu Wen, Li-Ping Chen.

Formal analysis: Chuan Li, Wei Peng, Xiao-Yun Zhang, Li-Ping Chen.

Methodology: Li-Ping Chen.

Software: Li-Ping Chen.

Supervision: Li-Ping Chen.

Writing – original draft: Chuan Li.

Writing – review & editing: Li-Ping Chen.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AUC = area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, HBV-DNA = hepatitis B virus-DNA, HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma, MVI = microvascular invasion, NLR = neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, OS = overall survival, PAR = platelet to albumin ratio, PH = portal hypertension, PLR = platelet to lymphocyte ratio, RFS = recurrence-free survival.

How to cite this article: Li C, Peng W, Zhang XY, Wen TF, Chen LP. The preoperative platelet to albumin ratio predicts the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma patients without portal hypertension after liver resection. Medicine. 2019;98:45(e17920).

This study was supported by grants from the State Key Scientific and Technological Research Programs (2017ZX10203207-003-0020), the Science and Technological Supports Project of Sichuan Province (2018SZ0204 and 2019YJ0149) as well as the Health and Family Planning Commission of Sichuan Province (17PJ393).

The authors have no conflicts of interests to disclose.

References

- [1].Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wen T, Jin C, Facciorusso A, et al. Multidisciplinary management of recurrent and metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma after resection: an international expert consensus. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2018;7:353–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bruix J, Boix L, Sala M, et al. Focus on hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2004;5:215–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Forner A, Hessheimer AJ, Isabel Real M, et al. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2006;60:89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chu MO, Shen CH, Chang TS, et al. Pretreatment inflammation-based markers predict survival outcomes in patients with early stage hepatocellular carcinoma after radiofrequency ablation. Sci Rep 2018;8:16611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Goh BK, Kam JH, Lee SY, et al. Significance of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and prognostic nutrition index as preoperative predictors of early mortality after liver resection for huge (≥ 10 cm) hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 2016;113:621–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kaida T, Nitta H, Kitano Y, et al. Preoperative platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio can predict recurrence beyond the Milan criteria after hepatectomy for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res 2017;47:991–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pang Q, Zhang JY, Xu XS, et al. Significance of platelet count and platelet-based models for hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:5607–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Adachi E, Maeda T, Matsumata T, et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic recurrence in human small hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 1995;108:768–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Harimoto N, Shirabe K, Ikegami T, et al. Postoperative complications are predictive of poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Res 2015;199:470–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wang C, Chen YG, Gao JL, et al. Low local blood perfusion, high white blood cell and high platelet count are associated with primary tumor growth and lung metastasis in a 4T1 mouse breast cancer metastasis model. Oncol Lett 2015;10:754–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhang Y, Wei J, Liu S, et al. Inhibition of platelet function using liposomal nanoparticles blocks tumor metastasis. Theranostics 2017;7:1062–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhou M, Li L, Wang X, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet count predict long-term outcome of stage IIIC epithelial ovarian cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem 2018;46:178–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Wang B, Li F, Cheng L, et al. The pretreatment platelet count is an independent predictor of tumor progression in patients undergoing transcatheter arterial chemoembolization with hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Future Oncol 2019;15:827–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sylman JL, Mitrugno A, Tormoen GW, et al. Platelet count as a predictor of metastasis and venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Converg Sci Phys Oncol 2017;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Obrink E, Eksborg S, Lonnqvist PA, et al. Preoperative platelet count and volume could not help predict PONV in women undergoing breast cancer surgery: a prospective cohort study. Int J Surg 2015;18:128–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Li C, Shen JY, Zhang XY, et al. Predictors of futile liver resection for patients with Barcelona clinic liver cancer stage B/C hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg 2018;22:496–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shirai Y, Shiba H, Haruki K, et al. Preoperative platelet-to-albumin ratio predicts prognosis of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma after pancreatic resection. Anticancer Res 2017;37:787–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Li C, Wen TF, Yan LN, et al. Postoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio plus platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts the outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Res 2015;198:73–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yamamura K, Sugimoto H, Kanda M, et al. Comparison of inflammation-based prognostic scores as predictors of tumor recurrence in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2014;21:682–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wang H, Xue L, Yan R, et al. Comparison of FIB-4 and APRI in Chinese HBV-infected patients with persistently normal ALT and mildly elevated ALT. J Viral Hepat 2013;20:e3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Giannini EG, Savarino V, Farinati F, et al. Influence of clinically significant portal hypertension on survival after hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients. Liver Int 2013;33:1594–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Buergy D, Wenz F, Groden C, et al. Tumor-platelet interaction in solid tumors. Int J Cancer 2012;130:2747–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Saito N, Shirai Y, Horiuchi T, et al. Preoperative platelet to albumin ratio predicts outcome of patients with cholangiocarcinoma. Anticancer Res 2018;38:987–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Steele M, Voutsadakis IA. Pre-treatment platelet counts as a prognostic and predictive factor in stage II and III rectal adenocarcinoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2017;9:42–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Stone RL, Nick AM, McNeish IA, et al. Paraneoplastic thrombocytosis in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:610–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gay LJ, Felding-Habermann B. Contribution of platelets to tumour metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer 2011;11:123–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Stegner D, Dutting S, Nieswandt B. Mechanistic explanation for platelet contribution to cancer metastasis. Thromb Res 2014;133Suppl 2:S149–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Palumbo JS, Talmage KE, Massari JV, et al. Platelets and fibrin(ogen) increase metastatic potential by impeding natural killer cell-mediated elimination of tumor cells. Blood 2005;105:178–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Placke T, Orgel M, Schaller M, et al. Platelet-derived MHC class I confers a pseudonormal phenotype to cancer cells that subverts the antitumor reactivity of natural killer immune cells. Cancer Res 2012;72:440–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Xue TC, Ge NL, Xu X, et al. High platelet counts increase metastatic risk in huge hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolization. Hepatol Res 2016;46:1028–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Choi GH, Park JY, Hwang HK, et al. Predictive factors for long-term survival in patients with clinically significant portal hypertension following resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int 2011;31:485–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Chen X, Zhai J, Cai X, et al. Severity of portal hypertension and prediction of postoperative liver failure after liver resection in patients with Child-Pugh grade A cirrhosis. Br J Surg 2012;99:1701–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Fang KC, Su CW, Chiou YY, et al. The impact of clinically significant portal hypertension on the prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after radiofrequency ablation: a propensity score matching analysis. Eur Radiol 2017;27:2600–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Liu J, Zhang H, Xia Y, et al. Impact of clinically significant portal hypertension on outcomes after partial hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford) 2019;21:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Li C, Zhang XY, Peng W, et al. Postoperative albumin-bilirubin grade change predicts the prognosis of patients with hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma within the Milan criteria. World J Surg 2018;42:1841–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Johnson PJ, Berhane S, Kagebayashi C, et al. Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a new evidence-based approach-the ALBI grade. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:550–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chan AW, Chan SL, Wong GL, et al. Prognostic nutritional index (PNI) predicts tumor recurrence of very early/early stage hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:4138–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Takagi K, Umeda Y, Yoshida R, et al. Preoperative controlling nutritional status score predicts mortality after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Surg 2019;36:226–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bagirsakci E, Sahin E, Atabey N, et al. Role of albumin in growth inhibition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology 2017;93:136–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Gupta D, Lis CG. Pretreatment serum albumin as a predictor of cancer survival: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Nutr J 2010;9:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]