Abstract

Necroptosis is a lytic form of programmed cell death that involves the swelling and rupture of dying cells. While several necroptosis-inducing stimuli have been defined, in most cells this pathway is kept in check by the action of the pro-apoptotic protease caspase-8 and the IAP ubiquitin ligases. How and when necroptosis is triggered under physiological conditions therefore remains a persistent question. Because necroptosis likely arose as a defensive mechanism against viral infection, exploration of this question requires a consideration of host-pathogen interactions, and how the sensing of infection could sensitize cells to necroptosis. Here, we will discuss the role of necroptosis in the response to viral infection, consider why the necroptotic pathway has been favored during evolution, and describe emerging evidence for death-independent functions of key necroptotic signaling components.

Introduction

Programmed cell death is an important part of development, homeostasis, and pathogen defense. As we develop, cell populations expand and contract, forming critical parts of us like the digits of our fingers and the folds of our brains. Once we reach adulthood, billions of our cells are turned over and replaced by others each day, and when we are infected with an invading pathogen, cell death can be an important component of the immune response leading to the clearance of that infection and survival of the host. Most developmental and homeostatic cell death is carried out by the caspase proteases, via the well-described pathway of apoptosis. From the point of view of the immune system, this death is quiet: the apoptotic cell condenses and packages itself for rapid and uneventful elimination by phagocytes.

The mechanism and morphology of apoptosis stand in contrast to that of necroptosis, a more recently described form of programmed cell death. Necroptosis is carried out by the receptor interacting protein kinases, RIPK1 and RIPK3, and their activation results in cellular swelling, bursting, and the release of intracellular contents into the extracellular space. Interestingly, RIPK3 seems to require the suppression, rather than the activation, of a key apoptotic caspase—caspase-8—to carry out its pro-death role. These characteristics lead to a few interesting questions:

What benefit is conferred on the host by the existence of the RIP kinase pathway, and of necroptotic cell death?

Is there an immunological benefit to the lytic, inflammatory nature of necroptosis?

Why have we evolved a form of programmed cell death that seemingly only occurs when another cell death process cannot be carried out?

These questions are linked; answering the second and third may help us answer the first. The lytic nature of necroptosis would be presumed to stimulate inflammation, and promote immune cell recruitment. This would be undesirable if the point were tissue homeostasis or development, but beneficial during an infection. But why would this occur preferentially when caspases are inhibited? Some pathogens target the caspase-8 apoptotic pathway, possibly to prevent killing of infected cells by Fas ligand on the surface of responding CD8+ T cells. This targeting might explain the emergence of a cell death pathway that is activated only when caspase-8 is blocked but perhaps there are other non-death-related functions of the RIP kinases and caspase-8 have driven the emergence and interplay of the necroptotic and apoptotic pathways.

Before discussing roles for RIPK signaling in the host response to pathogens, let us briefly consider the pathway of necroptosis as it is currently understood. This pathway has been extensively reviewed elsewhere(1)(2)(3)(4), so here we will provide only a brief summary. RIPK3 can be activated downstream of several receptors, including TNFR1, Fas, TRAIL-R, TLR-3 and −4, and by the interferon (IFN)-inducible innate sensor DAI. However, it has been most extensively characterized downstream of TNF signaling. In most cellular contexts, TNF is a pro-survival signal. Upon engagement, its receptor interacts with numerous cytosolic proteins including RIPK1, forming a receptor-associated complex that triggers NF-kB activation(5). Subsequently, it is thought that RIPK1 can translocate to the cytosol, where it forms additional complexes. One of these is a complex that contains RIPK3(6), the so-called necrosome. Formation of this complex requires the interaction of the RIP homotypic interaction motif (RHIM) domains present in both RIPK1 and RIPK3 and can lead to RIPK3 activation and cell death, but is normally prevented from doing so by the action of a heterodimeric enzyme complex composed of caspase-8 and cFLIP(7). These enzymes are recruited to RIPK1 via the adapter FADD and cooperate with E3 ubiquitin ligases, the IAPs, to abrogate necrosome formation and prevent necroptosis(8,9). Notably, cFLIP is a target of NF-kB, meaning that RIPK1 signaling at the TNFR1 complex leads to up-regulation of a protein that will prevent its participation in necroptotic signaling. This regulation is essential to survival, as genetic deletion of caspase-8 is lethal during embryonic development, but is fully rescued by the additional deletion of RIPK3(10). Notably then, the necrosome can stably form only when caspase-8 is absent or inhibited, or perhaps when cFLIP upregulation or IAP function is blocked. In such conditions, RIPK1 and RIPK3 can oligomerize and activate MLKL, a pseudokinase that translocates to the plasma membrane, leading to the cellular swelling and rupture that characterizes necroptotic cell death(11–14). These conditions can be mimicked in vitro by chemical inhibitors of the caspases or the IAPs, and as we will discuss below, also occur during certain infections.

Pathogen defense

While genetic studies have proven invaluable to our understanding of the signaling mechanisms of necroptosis, the question remains: why has necroptosis been selected for during evolution? RIPK3-deficient mice lack an overt phenotype, but are sensitive to many viral infections(15–19). Furthermore, several pathogens have evolved mechanisms to antagonize the necroptotic pathway, indicating that disrupting RIPK3 activation is critical to successful infection by these organisms(16,20). These findings are consistent with the idea that the core function of the necroptotic pathway lies in the host response to infection. Here we will discuss how pathogens trigger RIPK3-dependent responses, how they have evolved to evade those responses, and how type I IFN signaling, a well characterized innate immune programs, plays a critical role in necroptosis.

Through the trap door: caspase inhibition and necroptosis induction in physiological settings

In vitro studies on mechanisms of RIPK3 activation usually require the use of caspase inhibitors, hinting at its physiological role. Caspase-dependent cell death is the most ancient form of programmed cell death, and evolutionary evidence implies that the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, which is responsible for developmental and homeostatic cell death, originated as a pathogen-sensing pathway(21). Thus, caspase-dependent death was presumably the only form of programmed death that pathogens had to evade at one time. It is therefore not surprising that many pathogens encode caspase inhibitors that allow for escape from apoptosis or the related caspase-dependent process of pyroptosis(22)(23). However, as the RIP kinases evolved, it may be that a cell death function was gained by this pathway to induce programmed cell death when caspases were no longer active, giving the cell a trap door for pathogen clearance(24). Vaccinia virus (VACV) was one of the first viruses shown to induce RIP3 activation(19). VACV encodes a caspase inhibitor (B13R/Spi2) that sensitizes cells to programmed necrosis(25). Induction of RIPK3-dependent effects are critical to host survival, as RIPK3-deficient mice succumb to VACV infection while WT mice are able to clear the infection. Presumably this is due to its pro-death function, however other roles of RIPK3 (discussed later) have not been examined in this model. Infection of MLKL knockout animals with VACV would be informative to determine if necroptosis is the primary mediator of host survival.

Like viruses, many bacteria encode proteins that suppress caspase activation; for example, pathogenic E. coli produce NleB1, a T3SS effector that inhibits caspase-8 activity, blocking apoptosis in infected cells(26). Furthermore, a component of bacterial cell wall, LPS, has been show to activate RIPK3 in vitro through a common TLR adaptor and RHIM-domain containing protein, Trif(27). This combination of caspase inhibition and TLR stimulation would seem an ideal activator of necroptosis. However, RIPK3’s role in bacterial infections is complicated, and a protective role for necroptosis during bacterial infection has not been clearly demonstrated. Given the existence of caspase inhibitors in bacteria, it may be that these pathogens also encode inhibitors of RHIM-dependent signaling. Analogous to effects observed in DNA viruses (discussed below), this would effectively defuse this pathway, eliminating differences observed in RIPK3-deficient settings unless these inhibitors were removed. Furthermore, unlike viruses, not all bacteria need to replicate inside a cell, making cell death a less valuable option for host defense. Indeed, there are examples of bacteria inducing cell death in immune cells to successfully evade the host response(28)(29). Finally, control of pathogenic bacteria seems to rely more readily on the lytic process of pyroptosis than on necroptosis(30).

While caspase-8 suppression is clearly an important sensitizer to necroptosis, it is likely not the only cellular context where RIPK3 can be active. When added to cells in vitro, TNF acts as a pro-survival signal unless caspase-8 is absent or inhibited. But injection of high doses of TNF into a mouse causes a sterile shock response, and surprisingly this is RIPK3-dependent(31). How does TNF lead to a RIPK3-dependent response in vivo without caspase-suppression? There are a few hypotheses that could explain these observations. First, in a whole animal, there could be a subset of “necroptosis ready” cells in which caspase-8 activity is low, effectively priming them for RIPK3-activation. But perhaps a more intriguing hypothesis is the idea that mammals have evolved additional “trap doors” to trigger RIPK3 activation. An important component of caspase-8’s ability to suppress necroptosis is the upregulation of its binding partner, cFLIP(7). cFLIP is a target of NF-kB signaling, and blocking transcription or translation of this protein can allow both necroptosis and caspase-8-driven apoptosis to occur. In this scenario, a failure of some cells to adequately upregulate cFLIP could explain their apparent susceptibility to RIPK3-dependent cell death during models of TNF septic shock, which could also induce apoptosis in some tissues. Perhaps in agreement with this idea, mice lacking both RIPK3 and caspase-8 display a significantly greater resistance to systemic TNF administration than mice lacking only RIPK3(32).

The idea that failure to upregulate cFLIP or other survival factors could act as a key sensitizer to necroptosis may also apply to settings of pathogen infection. Many pathogens modify transcription and/or translation during their takeover of the cellular environment, and perturbations of cFLIP expression, or protein synthesis in general, may represent an additional “trap door” pathogens can fall into, triggering a RIPK3-dependent response. A possible (though unproven) example of this idea comes from work on influenza A virus (IAV). Infection with influenza has recently been shown to trigger necroptosis without the addition of a caspase inhibitor both in vitro and in vivo(17). Interestingly, unlike other RIPK3-activating viruses, IAV has not been shown to encode its own endogenous caspase inhibitor to block caspase-8 activity and sensitize cells to a RIPK3-dependent response. Indeed, caspase-8 activity seems to be intact in IAV-infected cells, as deletion or knockdown of MLKL results in back-signaling from the RIP kinases and caspase-8-dependent apoptosis. What allows for RIPK3 activation in the presence of active caspase-8? IAV is known to block translation of cellular mRNAs(33), and perhaps this change in protein synthesis or changes in particular protein levels (like cFLIP) allows for RIPK3 activation. While caspase-8 suppression is the most well characterized “trapdoor” for pathogens, it seems probable that there are other cellular perturbations that lead to RIPK3 activation and necroptosis. What these cellular changes are and how they lead to RIPK3 activation remains to be explored.

RHIM-based viral evasion

Perhaps the most compelling evidence that the RIP kinase pathway plays an important role in viral defense is that viruses have evolved to counteract programmed necrosis. This has been most extensively characterized in DNA viruses. MCMV contains both a viral inhibitor of caspase activation (vICA) and a viral inhibitor of RHIM activation (vIRA)(16). vICA blocks apoptosis, but is a double-edged sword for the virus, as it also blocks caspase-8 activity and sensitizes to necroptosis. However, vIRA contains its own RHIM domain which interferes with the interaction of RIPK3 with DAI, a RHIM-containing protein shown to be important in controlling herpesvirus infection through induction of necroptosis(15). It seems likely that a proto-virus may have first acquired the ability to block apoptosis, which at one time might have been the primary cell death response to infection. However, as RIP kinases evolved and necroptosis emerged as an outcome of caspase suppression, the virus in turn had to counteract both apoptosis and necroptosis for its continued propagation. Intriguingly, HCMV seems to have evolved a different strategy to counteract necroptosis, as it does not encode a RHIM domain-containing protein like vIRA, but can still block necroptosis downstream of RIPK3 via an unknown mechanism(34). This highlights not only the co-evolution of these DNA viruses with their hosts, but also the multitude of strategies a virus can take to block RIP3-dependent death (Figure 1). Like MCMV, herpes simplex viruses-1 and −2 (HSV-1/2) also encode RHIM-domain containing proteins (ICP6 and ICP10, respectively) that block necroptosis in human cells(35). Interestingly, these proteins were previously shown to block caspase-8 activity, and so simultaneously sensitize cells to necroptosis, while blocking RIP3 activation. Again, we might hypothesize that HSV first acquired the ability to block caspase-8 dependent apoptosis, and then had to acquire the ability to block the cell death trapdoor of necroptosis. But unlike MCMV, HSV uses one protein to block both cell death programs, likely constraining the evolution of this protein to retain both functions.

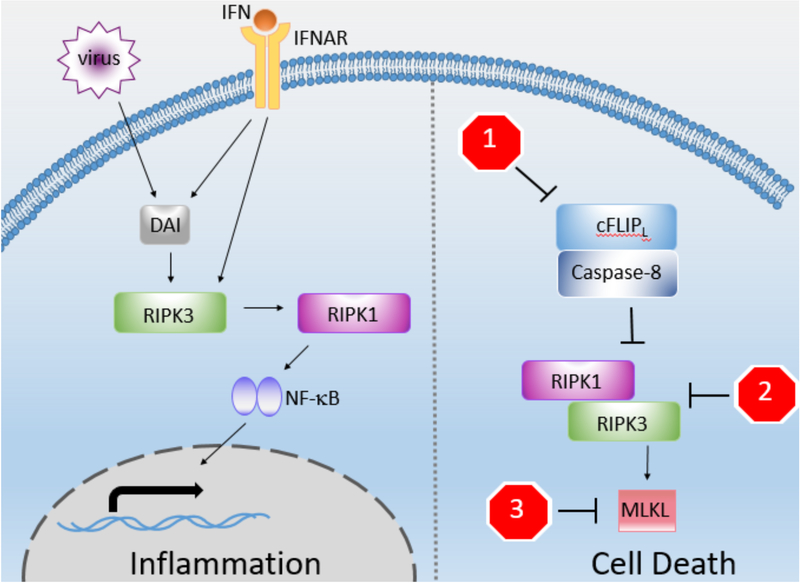

Figure 1: RIPK3 has both death and non-death roles.

RIPK3 can mediate both inflammation and cell death. While the cytokine-producing functions of RIPK1 and caspase-8 are more well understood, RIPK3’s role is still under investigation. Viruses, potentially through DAI or IFN, can directly activate RIPK3, allowing RIPK3-dependent cytokine production, likely through interactions with RIPK1 or caspase-8. Inflammation may be the more ancient function of the RIP kinase pathway, and begs the question: can this occur independently of RIPK3’s cell death role? RIPK3’s cell death role is more established, and many pathogens engage with diverse proteins associated with necroptosis. Some pathogens sensitize to necroptosis by blocking the caspase-8/FLIP heterodimer (stop sign 1). Others block necrosome formation (stop sign 2). And finally, others block downstream of RIPK3 activation in a less-well understood fashion, potentially involving blockade of MLKL oligomerization, access to the cell membrane, or perturbation of yet-to-be-described cofactors (stop sign 3). These pathogen interactions have allowed greater understanding of how the pathway works and its physiological role in pathogen defense.

Stop signs:

1 – ICP6 (HSV-1), ICP10 (HSV-2), vICA (CMV), vFLIP (KSHV, MCV), CrmA (Cowpox), B13R (VACV), E3 (adenovirus), Serp2 (myxoma virus), E6 (HDV-16)

2 – ICP6 (HSV-1), ICP10 (HSV-2), vIRA/M45 (murine mCMV)

3 – IE1 (hCMV)

Surprisingly, ICP6 and ICP10 do not block necroptosis in murine cells, but rather activate RIPK3, highlighting a lack of species crossover for RHIM activity by this virus. The biochemistry and mechanism of RHIM-RHIM interactions and oligomerization are incompletely understood. Presently, we understand that RHIM interactions are critical for both negative regulation of RIPK3 activation, as well as oligomerization upon its activation(36)(6). Current models postulate that conformational changes following post-translational modification or protein binding lead to RHIM exposure and initiate the formation of RHIM-containing complexes. But it remains unclear whether all RHIMs are able to participate in such complexes, and whether certain RHIMs are intrinsically stiochiometrically favored within the RHIM amyloid. While it is clear that RIPK1’s RHIM allows for bridging between RIPK3 and caspase-8, it is unclear how other RHIM-containing proteins, including RHIM-containing viral inhibitors, restrict RIPK3 activation. Do these proteins target RIPK3 for degradation or sterically hinder the formation of protein complexes? As the core interaction-determining region of the RHIM is very small, perhaps it simply initiates protein associations while the rest of the protein dictates whether oligomerization is propagated or blocked. The result of this interaction is species-specific, as HSV can only block RIPK3 activation in human cells, its natural host. This raises the possibility that only the correct interaction will block oligomerization, while other interactions through a RHIM might propagate the oligomer. Further investigations into the biochemistry of RHIM interactions might be enlightening on this front.

Necroptosis as an arm of the interferon-driven antiviral response

Type I interferons are a set of secreted cytokines capable of upregulating hundreds of genes that induce an antiviral state within cells. Interestingly, macrophages deficient in type I IFN signaling could not undergo necroptosis following treatment with RIPK3 activators, such as TNF and toll-like receptor ligands(37). This finding is surprising, as the mechanisms of RIPK3 activation for these ligands are known, and relatively linear, with no known role for interferons. Though MLKL is IFN-inducible, protein levels are similar between WT and IFNAR-deficient cells, pointing to additional IFN-dependent control of necroptosis that has yet to be uncovered. Perhaps some additional interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) plays a critical, yet undefined general role in necroptosis. Understanding why type I IFN contributes to induction of necroptosis downstream of all known RIPK3-activating ligands remains an intriguing open question in the field.

Additionally, IFN itself seems to be capable of inducing necroptosis in cells lacking caspase-8 function(38), though the mechanism of how this occurs remains murky. While PKR, an RNA sensor, has been implicated in this process, subsequent work found no role for PKR in IFN-induced necroptosis(37). An intriguing alternative hypothesis on how type I IFN might cause necroptosis is by the upregulation of DAI, a highly IFN-responsive gene that is one of four RHIM-domain containing proteins in mammals(39). DAI is known to be an important sensor of herpesvirus infections, and can directly interact with RIPK3, leading to its activation and necroptosis(15). While DAI has been described as a DNA sensor(40), it has never been shown to bind DNA during a herpesvirus infection, nor to trigger necroptosis following introduction of a pure DNA ligand to the cytosol. Furthermore, DAI has most recently been shown to play an important role in triggering RIPK3 activation and cell death during infection with an RNA virus, influenza virus(41). What does DAI sense – DNA, RNA, or something else? Perhaps expression of DAI over a certain threshold can lead to spontaneous interaction with RIPK3, or perhaps DAI can be activated by an endogenous ligand, either a nucleic acid motif or a protein. If this were true, DAI could be responsible for IFN-induced necroptosis, either due to exogenous addition or during the course of viral infections. A better understanding of how IFN signaling interfaces with and sensitizes to necroptosis will likely be forthcoming, and may support the idea that necroptotic cell death is a component of the IFN-driven antiviral response.

Evolutionary perspectives: inflammation before death

Much of the research surrounding RIPK3-dependent signaling has revolved around its pro-death role. But emerging evidence shows that RIPK3 may have non-cell death functions in pro-inflammatory signaling. Perhaps we should not be so surprised that RIPK3 has other functions; it is strongly tied to a pathway that has its roots in inflammatory signaling. Cell death may therefore represent a more recently acquired function of the RIP kinase pathway.

A homologue of RIPK3 is present in lampreys(42), indicating that it emerged, likely as a gene duplication event, early in the vertebrate lineage. But much of the pathway involved in RIP kinase signaling has even more ancient roots. Drosophila have homologs of man y members of the TNF-driven proinflammatory pathway, including a RHIM domain-containing RIPK1-like molecule, imd. Remarkably similar to mammalian RIPK1, imd associates with the Drosophila FADD homolog and a caspase dredd, and activates Relish, the fly equivalent of NF-kB, through coordinated signaling of IKK homologs and ubiquitin(43). Interestingly, the imd pathway senses bacterial peptitoglycans and promotes the release of antimicrobial molecules, suggesting that this pathway has an ancient role in host defense. Glycan sensing in mammals is accomplished in part by the NOD receptors which converge on activation of another RIPK family member, RIPK2(44). This suggests additional divergent evolution in these pathways between fly and mammals; NOD/RIP2 maintained the glycan sensing ability of the imd pathway, while the ancestral signaling components were re-configured into the RIP1/RIP3 pathway which now responds to other signals. Similar to the mammalian TNF response, under certain stimuli, the imd pathway can lead to caspase-dependent cell death(45), mirroring caspase-8-dependent apoptosis. But Drosophila do not have a RIPK3 homolog, nor do they seem to have a caspase-independent cell death program.

So why do mammals have RIPK3? Perhaps one clue lies in its sequence. Comparison of gene sequences between evolutionarily related species allows measurement of the rate with which a given gene is undergoing non-synonymous mutation, which in turn allows estimation of the evolutionary pressure being applied to a given protein. Most often, this pressure represents efforts by pathogens to antagonize a given protein, conferring evolutionary advantage on mutations that allow escape from that antagonism. Applying this measure of “positive selection” to the RIPKs reveals that while RIPK3 is rapidly evolving under positive selection in primates, RIPK1 is not (M. Patel and H. Malik, personal communication). Gene duplication events can allow proteins more flexibility in their evolution while maintaining their core function. In mammals, loss of RIPK1 is perinatally lethal due to unrestrained programmed cell death(5)(46), and this likely constrains the ability of RIPK1 to evolve in the face of invading pathogens. Perhaps the emergence of RIPK3 allowed the pathway to rapidly evolve its additional pro-death function without losing the indispensable functions of RIPK1 in the process. Certainly during evolutionary time, animals were being exposed to various pathogens, requiring nimble evolution of innate immune responses. Duplication and subsequent neofunctionalization of the RIP kinases may have helped our animal ancestors survive these infections.

One of the roles RIPK3 has evolved is the ability to induce necroptosis. But if its roots are within this proinflammatory signaling platform, it may have other non-cell death roles. Indeed, many death-independent roles of RIPK3 are beginning to be described. Bone marrow derived macrophages stimulated with LPS and zVAD produce TNFa in a RIPK1 and RIPK3-dependent manner(47). However, this effect does not require the expression of MLKL, indicating that these effects are unrelated to RIPK3’s ability to induce cell death. While the biological circumstances in which LPS-driven, RIPK3-dependent inflammatory transcription might be important remain unclear, these findings clearly indicate a death-independent function for RIPK3. Furthermore, RIPK3-deficient mice show more protection from disease models of kidney ischemia-reperfusion and A20-deficiency than MLKL KO animals(32), implying functions of RIPK3 in these models that extend beyond MLKL activation and necroptosis. Intriguingly, direct activation of RIPK3 has been shown to produce immunostimulatory cytokines that allow for better cross priming of T cells(48), indicating that one of RIPK3’s non-death roles may be linking the innate and adaptive immune responses. Interestingly, production of these cytokines requires the RHIM domain of RIPK3 in order to engage RIPK1 and NF-kB signaling, somewhat backwards from the canonical RIPK1 to RIPK3 signal. However, as RIPK3 can be activated independently of RIPK1 by other RHIM-containing proteins(15)(39), this “backwards” interaction could allow RIPK3 to engage the proinflammatory capacity of RIPK1 outside of traditional receptor-driven signaling, which may play an important inflammatory role during infection. As such, perhaps one early role of RIPK3 was linking antiviral signaling with proinflammatory cytokine production. While these results are certainly illuminating, understanding the capacity and mechanism of RIPK3’s coordination of both cytokine production and cell death is still in its infancy. As many disease models have implicated RIPK3 involvement, either in clearance of infection or propagation of inflammatory effects, it will be important to further clarify whether the pathology of these models is driven by a pro-death or non-death role of the RIP kinases.

Concluding remarks

Evolutionary studies imply that while the ancestral RIP kinase pathway did not contain a functional RIPK3-like molecule or induce caspase-independent cell death, evolution favored these adaptations. For what purpose were they added? Examining what we know about RIPK3-dependent signaling is suggestive of an answer. Necroptosis is triggered upon infection by several viral pathogens in vitro, and mice lacking RIPK3 succumb to many of these pathogens more readily than wild-type animals. Furthermore, it appears that IFN signaling—a master regulator of the anti-viral response—is required for necroptosis in at least some cells, though the mechanism by which IFN and necroptosis are connected is not clear. These findings support the idea discussed in the introduction to this piece: that RIPK activation during viral infection triggers inflammatory cell death, eliminating infected cells and promoting inflammation and immunity. Notably however, clear demonstration of necroptosis in vivo during infection, and precisely how this cell death program might promote host defense, remains elusive.

While much has been learned since the discovery of RIPK3, many questions remain about its activation. Are there other sensitizers to RIPK3 activation besides caspase-8 inhibition? It seems likely that some kind of transcription or translation perturbation could also lead to activation, but the nature of these interactions is not well understood, particularly in an in vivo setting. How exactly does IFN induce RIPK3 activation? Furthermore, do ligands capable of activating other antiviral IFN-production pathways, such as the cGAS-STING or RIG-I-like receptor pathways, also activate RIPK3? If IFN can induce necroptosis, it should follow that inducers of its expression might also lead to a similar response, expanding the possibility of RIPK3-dependent responses to other infections and disease models. It is possible that these ligands could work through a universal mechanism of RIPK3 activation that could shed light on why IFN signaling seems to be broadly required for necroptosis, at least in some cell types.

While RIPK3-dependent cell death has been the primary focus of research into its function, we increasingly appreciate that this is not the only function of RIPK3. It is becoming apparent that the RIP kinase pathway coordinates both the production of proinflammatory cytokines and cell death. Studying the non-death functions of RIPK3 remains difficult, due to the nature of the pathway it evolved from; RIPK1 has its own transcription effects, many of which are independent from RIPK3. Further, recent work indicates that caspase-8 can participate in cytokine production as well(49). And yet still the question remains, how and why exactly did RIPK3 evolve to be activated when caspase-8 is suppressed? Perhaps this is simply an additional checkpoint to ensure that necroptosis does not happen when apoptosis could be favored, as necroptosis might lead to unnecessary inflammation and immune response. However, there may be other possibilities related to the non-death roles of these proteins. Perhaps RIPK3 activation leads to a distinctly different set of cytokines that instruct an inflammatory response in ways that caspase-8 or RIPK1-dependent cytokines do not. Comparison of RIPK3-deficient and MLKL-deficient mice seems to be a viable way to determine which responses are dependent on cell death, rather than the inflammatory effects of RIPK3. Untangling RIPK3’s role in inflammation from the inflammatory capacity of caspase-8 and RIPK1 remains a challenging task, but one that will illuminate the evolutionary emergence and function of this novel cell death pathway.

Acknowledgements:

We thank Susana Orozco for help with figure design and Annelise Snyder for editorial comments. This work is supported by NIGMS grant PHS NRSA T32GM007270 (to MB) and NIH grants 1R01AI108685–01 and 1R21CA185681 (to AO).

Bibliography:

- 1.Linkermann A, Green DR. Necroptosis. N Engl J Med. 2014. January 30;370(5):455–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasparakis M Necroptosis and its role in inflammation. Nature. 2015. January 14;517(7534):311–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newton K, Manning G. Necroptosis and Inflammation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2016. February 8;85(1):743–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan FK-M, Luz NF, Moriwaki K. Programmed Necrosis in the Cross Talk of Cell Death and Inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. Annual Reviews 4139 El Camino Way, PO Box 10139, Palo Alto, California 94303–0139, USA; 2014. May 9;33(1):141210135520002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelliher MA, Grimm S, Ishida Y, Kuo F, Stanger BZ, Leder P. The death domain kinase RIP mediates the TNF-induced NF-kappaB signal. Immunity. 1998. March;8(3):297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J, McQuade T, Siemer AB, Napetschnig J, Moriwaki K, Hsiao Y-S, et al. The RIP1/RIP3 necrosome forms a functional amyloid signaling complex required for programmed necrosis. Cell. 2012. July 20;150(2):339–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oberst A, Dillon CP, Weinlich R, McCormick LL, Fitzgerald P, Pop C, et al. Catalytic activity of the caspase-8-FLIP(L) complex inhibits RIPK3-dependent necrosis. Nature. 2011. March 17;471(7338):363–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moulin M, Anderton H, Voss AK, Thomas T, Wong WW-L, Bankovacki A, et al. IAPs limit activation of RIP kinases by TNF receptor 1 during development. The EMBO Journal. 2012. February 10;31(7):1679–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geserick P, Hupe M, Moulin M, Wong WWL, Feoktistova M, Kellert B, et al. Cellular IAPs inhibit a cryptic CD95-induced cell death by limiting RIP1 kinase recruitment. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2009. December 28;187(7):1037–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaiser WJ, Upton JW, Long AB, Livingston-Rosanoff D, Daley-Bauer LP, Hakem R, et al. RIP3 mediates the embryonic lethality of caspase-8-deficient mice. Nature. 2011. March 17;471(7338):368–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dondelinger Y, Declercq W, Montessuit S, Roelandt R, Goncalves A, Bruggeman I, et al. MLKL compromises plasma membrane integrity by binding to phosphatidylinositol phosphates. Cell Rep. 2014. May 22;7(4):971–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez DA, Weinlich R, Brown S, Guy C, Fitzgerald P, Dillon CP, et al. Characterization of RIPK3-mediated phosphorylation of the activation loop of MLKL during necroptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2015. May 29;. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H, Sun L, Su L, Rizo J, Liu L, Wang L-F, et al. Mixed Lineage Kinase Domain-like Protein MLKL Causes Necrotic Membrane Disruption upon Phosphorylation by RIP3. Mol Cell. 2014. April;54(1):133–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cai Z, Jitkaew S, Zhao J, Chiang H-C, Choksi S, Liu J, et al. Plasma membrane translocation of trimerized MLKL protein is required for TNF-induced necroptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2014. January;16(1):55–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Upton JW, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES. DAI/ZBP1/DLM-1 complexes with RIP3 to mediate virus-induced programmed necrosis that is targeted by murine cytomegalovirus vIRA. Cell Host and Microbe. 2012. March 15;11(3):290–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Upton JW, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES. Virus Inhibition of RIP3-Dependent Necrosis. Cell Host and Microbe. 2010. April 22;7(4):302–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nogusa S, Thapa RJ, Sharma S, Gough PJ, Dillon CP, Oberst A, et al. RIPK3 activates parallel pathways of FADD-mediated apoptosis and MLKL-driven necroptosis to protect against influenza A virus. Cell Host and Microbe in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris KG, Morosky SA, Drummond CG, Patel M, Kim C, Stolz DB, et al. RIP3 Regulates Autophagy and Promotes Coxsackievirus B3 Infection of Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Cell Host and Microbe. Elsevier; 2015. December 8;18(2):221–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho YS, Challa S, Moquin D, Genga R, Ray TD, Guildford M. Phosphorylation-driven assembly of the RIP1-RIP3 complex regulates programmed necrosis and virus-induced inflammation. Cell. 2009. June 12;137(6):1112–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo H, Omoto S, Harris PA, Finger JN, Bertin J, Gough PJ, et al. Herpes Simplex Virus Suppresses Necroptosis in Human Cells. Cell Host and Microbe. 2015. February;17(2):243–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oberst A, Bender C, Green DR. Living with death: the evolution of the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis in animals. Cell Death Differ. 2008. May 2;15(7):1139–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewart MK, Cookson BT. Evasion and interference: intracellular pathogens modulate caspase-dependent inflammatory responses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016. May 13;14(6):346–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mocarski ES, Upton JW, Kaiser WJ. Viral infection and the evolution of caspase 8-regulated apoptotic and necrotic death pathways. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2011. December 23;12(2):79–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaiser WJ, Upton JW, Mocarski ES. Viral modulation of programmed necrosis. Current Opinion in Virology. 2013. June;3(3):296–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li M, Beg AA. Induction of Necrotic-Like Cell Death by Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha and Caspase Inhibitors: Novel Mechanism for Killing Virus-Infected Cells. Journal of virology. 2000. August 15;74(16):7470–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pearson JS, Giogha C, Ong SY, Kennedy CL, Kelly M, Robinson KS, et al. A type III effector antagonizes death receptor signalling during bacterial gut infection. Nature. 2013. September 11;501(7466):247–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He S, Liang Y, Shao F, Wang X. Toll-like receptors activate programmed necrosis in macrophages through a receptor-interacting kinase-3-mediated pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011. December 13;108(50):20054–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson N, McComb S, Mulligan R, Dudani R, Krishnan L, Sad S. Type I interferon induces necroptosis in macrophages during infection with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium Nature Immunology. Nature Publishing Group; 2012. August 26;. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Staphylococcus aureus Degrades Neutrophil Extracellular Traps to Promote Immune Cell Death. Science. 2013;342(6160):863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miao EA, Leaf IA, Treuting PM, Mao DP, Dors M, Sarkar A, et al. Caspase-1-induced pyroptosis is an innate immune effector mechanism against intracellular bacteria. Nature Immunology. 2010. November 7;11(12):1136–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duprez L, Takahashi N, Van Hauwermeiren F, Vandendriessche B, Goossens V, Vanden Berghe T, et al. RIP kinase-dependent necrosis drives lethal systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Immunity. 2011. December 23;35(6):908–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newton K, Dugger DL, Maltzman A, Greve JM, Hedehus M, Martin-McNulty B, et al. RIPK3 deficiency or catalytically inactive RIPK1 provides greater benefit than MLKL deficiency in mouse models of inflammation and tissue injury. Cell Death Differ. 2016. May 13;. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Global Impact of Influenza Virus on Cellular Pathways Is Mediated by both Replication-Dependent and -Independent Events. Journal of virology. 2001;75(9):4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Omoto S, Guo H, Talekar GR, Roback L, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski E. Suppression of RIP3-dependent Necroptosis by Human Cytomegalovirus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Huang Z, Wu S-Q, Liang Y, Zhou X, Chen W, Li L, et al. RIP1/RIP3 binding to HSV-1 ICP6 initiates necroptosis to restrict virus propagation in mice. Cell Host and Microbe. 2015. February 11;17(2):229–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orozco S, Yatim N, Werner MR, Tran H, Gunja SY, Tait SWG, et al. RIPK1 both positively and negatively regulates RIPK3 oligomerization and necroptosis Cell Death Differ. Nature Publishing Group; 2014. October;21(10):1511–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McComb S, Cessford E, Alturki NA, Joseph J, Shutinoski B, Startek JB, et al. Type-I interferon signaling through ISGF3 complex is required for sustained Rip3 activation and necroptosis in macrophages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Thapa RJ, Nogusa S, Rall GF, Balachandran S. Interferon-induced RIP1/RIP3-mediated necrosis requires PKR and is licensed by FADD and caspases Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. National Acad Sciences; 2013. August 13;110(33):E3109–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaiser WJ, Upton JW, Mocarski ES. Receptor-interacting protein homotypic interaction motif-dependent control of NF-kappa B activation via the DNA-dependent activator of IFN regulatory factors. The Journal of Immunology. 2008. November 1;181(9):6427–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takaoka A, Wang Z, Choi MK, Yanai H, Negishi H, Ban T, et al. DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature. 2007. July 8;448(7152):501–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuriakose T, Man SM, Malireddi R. ZBP1/DAI is an innate sensor of influenza virus triggering the NLRP3 inflammasome and programmed cell death pathways. Science …. 2016;1(2):aag2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dondelinger Y, Hulpiau P, Saeys Y, Bertrand MJM, Vandenabeele P. An evolutionary perspective on the necroptotic pathway. Trends in Cell Biology. 2016. June 28;. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myllymäki H, Valanne S, Rämet M. The Drosophila imd signaling pathway. The Journal of Immunology. 2014. April 8;192(8):3455–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Philpott DJ, Sorbara MT, Robertson SJ, Croitoru K, Girardin SE. NOD proteins: regulators of inflammation in health and disease Nature Reviews Immunology. Nature Publishing Group; 2014. January 1;14(1):9–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Georgel P, Naitza S, Kappler C, Ferrandon D, Zachary D, Swimmer C, et al. Drosophila immune deficiency (IMD) is a death domain protein that activates antibacterial defense and can promote apoptosis. Developmental Cell. 2001. November 13;1(4):503–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaiser WJ, Mandal P, Guo H, Bertin J, Gough PJ, Balachandran S, et al. RIP1 suppresses innate immune necrotic as well as apoptotic cell death during mammalian parturition. pnasorg. 2014. May 27;111(21):7753–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Najjar M, Saleh D, Zelic M, Nogusa S, Shah S, Tai A, et al. RIPK1 and RIPK3 Kinases Promote Cell-Death-Independent Inflammation by Toll-like Receptor 4 Immunity. Elsevier; 2016. July;0(0). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yatim N, Jusforgues-Saklani H, Orozco S, Schulz O, Barreira da Silva R, Reis e Sousa C, et al. RIPK1 and NF-κB signaling in dying cells determines cross-priming of CD8⁺ T cells. Science. 2015. October 16;350(6258):328–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gurung P, Vande Walle L, Van Opdenbosch N, Weinlich R, Green DR, Lamkanfi M, et al. FADD and caspase-8 mediate priming and activation of the canonical and noncanonical Nlrp3 inflammasomes. jimmunolorg. American Association of Immunologists; 2014. February 15;192(4):1835–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]