Abstract

Objective

Whether increased myocardial oxygen demand could help explain the association of left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy with higher adverse event rate in patients with aortic valve stenosis (AS) is unknown.

Methods

Data from 1522 patients with asymptomatic mostly moderate AS participating in the Simvastatin-Ezetimibe in AS study followed for a median of 4.3 years was used. High LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product was identified as >upper 95% CI limit in normal subjects. The association of higher LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product with major cardiovascular (CV) events, combined CV death and hospitalised heart failure and all-cause mortality was tested in Cox regression analyses, and reported as HR and 95% CI.

Results

High LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product was found in 19% at baseline, and associated with male sex, higher body mass index, hypertension, LV hypertrophy, more severe AS and lower LV ejection fraction (all p<0.01). Adjusting for these confounders in time-varying Cox regression analysis, 1 SD higher LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product was associated with higher HR of major CV events (HR 1.16(95% CI 1.06 to 1.29)), combined CV death and hospitalised heart failure (HR 1.29(95% CI 1.09 to 1.54)) and all-cause mortality (HR 1.34(95% CI 1.13 to 1.58), all p<0.01).

Conclusion

In patients with initially mild–moderate AS, higher LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product was associated with higher mortality and heart failure hospitalisation. Our results suggest that higher myocardial oxygen demand is contributing to the higher adverse event rate reported in AS patients with LV hypertrophy.

Trial registration number

NCT000092677; Post-results.

Keywords: aortic stenosis, hypertension, echocardiography

Introduction

Left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy is a common manifestation of subclinical cardiovascular (CV) disease that strongly predicts increased risk for clinical CV disease including myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure and death both in the general population and in patients with hypertension.1 2 The association of LV hypertrophy with higher CV morbidity and mortality is multifactorial and may involve reduced myocardial flow reserve, increased myocardial oxygen demand, myocardial fibrosis and scarring, as well as neuroendocrine activation, capillary rarefication, increased production of proinflammatory cytokines, cellular dysfunction and elevated LV ventricular wall stress.3–7 Experimental studies on hypertension in dogs subjected to standardised coronary artery ligation demonstrated that LV hypertrophy was associated with increased myocardial infarct size and higher rates of ventricular arrhythmias.8 9 However, a subsequent study suggested increased myocardial oxygen demand rather than the level of LV hypertrophy as the principal determinant of myocardial infarct size.10 In line with these experimental findings, we recently demonstrated that higher myocardial oxygen demand, measured indirectly by echocardiography as LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product, was indeed associated with higher rates of myocardial infarction and CV mortality in hypertensive patients with LV hypertrophy.11

Traditionally, LV hypertrophy has been regarded as an adaptive response that keeps the LV wall stress close to normal in aortic valve stenosis (AS). However, in older subjects with AS, hypertension often coexists.12 Recent publications have demonstrated that both LV adaptation to AS and prognosis are influenced by concomitant hypertension.12 13 Furthermore, presence of LV hypertrophy or a disproportionately increased LV mass in relation to actual haemodynamic load in AS was independent of hypertension associated with higher rates of heart failure hospitalisation and mortality.14 Whether higher myocardial oxygen demand may contribute to the observed impaired prognosis in AS patients with LV hypertrophy is unknown. The aim of the present analysis was to test the association of higher LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product, as an indirect measure of myocardial oxygen demand, with CV events and prognosis in AS patients participating in the Simvastatin-Ezetimibe in AS (SEAS) study.

Methods

Study population

The SEAS study was a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study performed during the years 2002–2008 which assessed the effect of combined simvastatin and ezetimibe on AS progression and CV morbidity and mortality in 1873 patients with initially asymptomatic, mild-to-moderate AS.13–15 Of these, the core lab received baseline echocardiograms on 1788. LV mass could be assessed in 1730 patients at baseline, and in 1656 of these also on at least 1 follow-up echocardiogram. Due to lack of end-echocardiography blood pressure measurements, the circumferential end-systolic stress (CESS) could only be calculated in 1623 patients at baseline, leaving 1522 patient with data on CESS, heart rate and LV mass measured both at the baseline and at least 1 follow-up echocardiogram eligible for the current study population. Sex, age and peak aortic jet velocity did not differ significantly between eligible and non-eligible patients (all p>0.3), but non-eligible patients had a lower likelihood of suffering a primary study endpoint (p<0.001).

All patients signed informed consent prior to study enrolment.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed following a standardised study protocol at baseline and then annually and before valve surgery.14 15 All echocardiographic analysis was performed at the SEAS Echocardiography Core Laboratory, and 94% of final reading was done by the same experienced reader. The time range between the baseline and final echocardiogram was 2.7–84.4 months.

Quantitative echocardiographic evaluation of the LV and AS severity was performed following current guidelines.16 17 LV hypertrophy was considered present if LV mass/height2.7>46.7 g/m2.7 in women and 49.2 g/m2.7 in men, respectively.14 Concentric LV geometry was considered present if relative wall thickness >0.420.16 CESS was calculated by an invasively validated method,18 taking mean aortic valve gradient into account. Heart rate was measured on the echocardiograms as the average over 3 beats in patients in sinus rhythm and over 15 beats in patients with atrial fibrillation. Myocardial oxygen demand was estimated from the LV mass x CESS x heart rate product (LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product).11 Midwall shortening and stress-corrected midwall shortening were calculated using previously validated equations.19 Stress-corrected LV myocardial oxygen demand was estimated from LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product.11 High LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product was identified by the upper 95% CI limit calculated in a previously collected normotensive New York population (>2.13×106 g kdyne/cm2 bpm).20 Aortic valve area adjusted for pressure recovery in the aortic root, the energy loss, was calculated as previously published and used as the primary measure of AS severity, to avoid overestimation of severity in patients with milder degree of AS.21 LV stroke volume was calculated by Doppler and indexed for body surface area. LV diastolic function was assessed by peak early and atrial transmitral filling velocities, their ratio and left atrial anterior–posterior diameter.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was major CV events, a composite of aortic valve events (combined aortic valve replacement, CV death and hospitalisation for heart failure due to progression of AS) and ischaemic CV events (combined coronary artery bypass grafting, non-fatal myocardial infarction, hospitalisation for unstable angina pectoris, percutaneous coronary intervention and non-haemorrhagic stroke).15 All-cause mortality was a tertiary study endpoint. We also assessed hospitalisation for heart failure, combined CV death and hospitalisation for heart failure and combined all-cause mortality and hospitalisation for heart failure in the present analysis. All endpoints in the SEAS study were adjudicated by an independent committee.15

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were done using IBM SPSS V.25. Data are presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables. Groups of patients with high and normal LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product were compared using unpaired Student’s t-test and χ2 test, as appropriate. Clinically relevant covariables of high LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product identified in univariable logistic regression analysis were included in the multivariable model and reported as OR and 95% CI.12–15 Hosmer-Lemeshow test was used to assess the goodness-of-fit for the model. The association of high versus normal baseline LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product with outcome was assessed by Kaplan-Meier plots and log rank test. The association of 1 SD higher in-study LV mass–wall stress–heart rate with HRs of study endpoints was assessed in unadjusted and adjusted time-varying Cox regression models and reported as HRs and 95% CI. In the secondary model, prevalent atrial fibrillation and use of beta-blocker treatment at baseline and time-varying left atrial diameter, stroke volume index and serum creatinine were added. The incremental predictive value of LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product over its composites was assessed by comparison of global χ2 values in sequential Cox models including LV mass, CESS and heart rate as individual variables and the LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product, respectively. A two-tailed p<0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses.

Results

A high LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product was found in 19% of the study population at baseline. The group with high LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product included more men and patients with obesity and hypertension than those with normal LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product (table 1), and also had higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation and LV hypertrophy, lower LV systolic function and more severe AS, while age and LV diastolic filling was comparable in the two groups (table 2). In multivariable logistic regression analysis, presence of hypertension, male sex, lower LV ejection fraction and peak early/peak atrial transmitral velocity ratio, and higher body mass index and peak aortic jet velocity were all independently associated with presence of high LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product (all p<0.001) (table 3).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the total study population and in groups with high and normal LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product

| Variable | All (n=1522) | High LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product (n=289) | Normal LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product (n=1233) | P value |

| Age (years) | 67±10 | 68±9 | 67±10 | 0.272 |

| Male (%) | 61.1 | 74.1 | 58.1 | <0.001 |

| Height (m) | 1.70±0.09 | 1.73±0.09 | 1.70±0.09 | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 78.0±14.3 | 84.6±15.3 | 76.4±13.6 | <0.001 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 1.89±0.20 | 1.98±0.20 | 1.87±0.19 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.8±4.2 | 28.2±4.5 | 26.4±4.1 | <0.001 |

| Obesity (%) | 19.9 | 30.3 | 17.4 | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 148±20 | 155±20 | 146±20 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 83±10 | 85±11 | 82±10 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 66±11 | 71±13 | 64±10 | |

| Hypertension (%) | 83.3 | 92.1 | 81.2 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 9.7 | 14.9 | 8.4 | 0.001 |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 93±16 | 95±17 | 93±15 | 0.017 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 139±10 | 139±12 | 140±13 | 0.042 |

BP, blood pressure; bpm, beats per minute; LV, left ventricular.

Table 2.

Echocardiographic findings at baseline in the total study population and in groups of patients with high or normal LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product

| Variable | All (n=1522) | High LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product (n=289) | Normal LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product (n=1233) | P value |

| LV end-diastolic diameter (cm) | 5.03±0.63 | 5.55±0.59 | 4.91±0.57 | <0.001 |

| LV end-systolic diameter (cm) | 3.19±0.56 | 3.75±0.51 | 3.06±0.48 | <0.001 |

| Interventricular septal thickness (cm) | 1.15±0.28 | 1.32±0.30 | 1.11±0.25 | <0.001 |

| Posterior wall thickness (cm) | 0.89±0.19 | 0.98±0.19 | 0.86±0.18 | <0.001 |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 67±6 | 62±6 | 68±6 | <0.001 |

| Relative wall thickness | 0.36±0.09 | 0.35±0.08 | 0.36±0.09 | 0.716 |

| LV mass index (g/m2.7) | 45.5±14.4 | 59.9±15.6 | 42.1±11.8 | <0.001 |

| LV hypertrophy (%) | 34.4 | 74.6 | 24.9 | <0.001 |

| Concentric LV geometry (%) | 18.7 | 18.7 | 18.7 | 0.990 |

| Midwall shortening (%) | 17.0±3.3 | 15.3±2.9 | 17.4±3.2 | <0.001 |

| Circumferential end-systolic stress (dyne/cm2) | 129±35 | 158±38 | 122±31 | |

| Stress-corrected midwall shortening (%) | 97±19 | 91±18 | 99±19 | <0.001 |

| LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product (g kdyne/cm2 bpm) | 1.6×106±0.7×106 | 2.8×106±0.7×106 | 1.3×106±0.4×106 | |

| Peak aortic jet velocity (m/s) | 3.08±0.54 | 3.20±0.56 | 3.05±0.53 | <0.001 |

| Peak aortic valve gradient (mm Hg) | 39±14 | 42±14 | 38±13 | <0.001 |

| Mean aortic valve gradient (mm Hg) | 23±9 | 25±9 | 22±8 | <0.001 |

| Energy loss (cm2) | 1.50±0.66 | 1.54±0.65 | 1.49±0.67 | 0.210 |

| Energy loss index (cm2/m2) | 0.90±0.46 | 0.84±0.36 | 0.91±0.48 | 0.009 |

| Severe AS (%) | 19.9 | 20.4 | 17.8 | 0.329 |

| Stroke volume index (mL/m2) | 45±13 | 46±13 | 45±13 | 0.188 |

| Left atrial diameter (cm) | 3.74±0.66 | 3.97±0.68 | 3.69±0.64 | <0.001 |

| Peak early mitral filling velocity (m/s) | 0.75±0.23 | 0.73±0.23 | 0.75±0.23 | 0.146 |

| Peak atrial mitral filling velocity (m/s) | 0.83±0.25 | 0.86±0.25 | 0.83±0.25 | 0.045 |

| Peak early/peak atrial mitral filling velocity ratio | 0.93±0.35 | 0.89±0.39 | 0.94±0.34 | 0.050 |

| Deceleration time (ms) | 227±76 | 223±78 | 228±76 | 0.305 |

AS, aortic valve stenosis; LV, left ventricular.

Table 3.

Covariables of high LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Male sex | 1.90 (1.35 to 2.68) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 3.40 (1.99 to 5.82) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 1.07 (1.03 to 1.11) | 0.001 |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 0.87 (0.85 to 0.89) | <0.001 |

| Peak aortic jet velocity (m/s) | 2.05 (1.53 to 2.73) | 0.002 |

| Left atrial diameter (cm) | 1.61 (1.24 to 2.90) | <0.001 |

| Peak early/atrial mitral velocity ratio | 0.60 (0.38 to 0.96) | 0.035 |

Multivariable logistic regression analysis in the total study population.

LV, left ventricular.

Prognostic significance of LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product

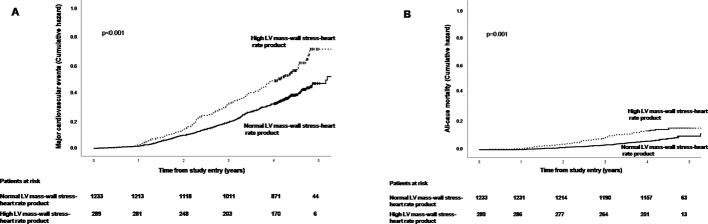

During a median of 4.3-year follow-up, the group with high LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product at baseline had higher rates of major CV events and higher all-cause mortality compared with those with normal LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product at baseline (both p<0.01) (figure 1). In unadjusted time-varying Cox regression, 1 SD higher in-study LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product was associated with a 23% higher HR of major CV events, a 50% higher HR of CV death, a 33% higher HR of all-cause mortality and a 60% higher HR of heart failure hospitalisation (all p<0.001) (table 4). The associations of high LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product remained significantly associated with mortality and combined mortality and hospitalised heart failure after adjustment for sex, hypertension, age and time-varying body mass index, LV hypertrophy, LV ejection fraction and peak aortic jet velocity, while the association with hospitalised heart failure was explained by the covariables (table 4, model 1). Adding prevalent atrial fibrillation and beta-blocker use at baseline, and time-varying left atrial diameter, Doppler stroke volume index and serum creatinine as covariables in a second model did not change the results (table 4, model 2). The yield (global χ2 value) of the primary Cox model did not differ significantly when LV mass, CESS and heart rate at baseline were included as individual variables compared with when the LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product at baseline was included (p=0.876), demonstrating that the prognostic information of the LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product was fully explained by the composites.

Figure 1.

Association of high LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product with HRs of major cardiovascular events (A) and all-cause mortality (B) in the study population. Kaplan-Meier plots.

Table 4.

Associations of in-study LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product with HRs of study outcomes

| Study outcome | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) |

P value | Adjusted model 1* HR (95% CI) |

P value | Adjusted model 2† HR (95% CI) |

P value |

| Primary endpoint (n=456) | 1.23 (1.14 to 1.32) | <0.001 | 1.16 (1.06 to 1.29) | 0.002 | 1.16 (1.05 to 1.29) | 0.002 |

| Heart failure hospitalisation (n=53) | 1.60 (1.37 to 1.87) | <0.001 | 1.18 (0.94 to 1.50) | 0.162 | n.a. | |

| CV death (n=63) | 1.50 (1.31 to 1.77) | <0.001 | 1.42 (1.14 to 1.79) | 0.002 | n.a. | |

| Combined CV death and hospitalised HF (n=105) | 1.49 (1.34 to 1.66) | <0.001 | 1.29 (1.09 to 1.54) | 0.004 | 1.33 (1.11 to 1.60) | 0.002 |

| All-cause mortality (n=121) | 1.33 (1.17 to 1.51) | <0.001 | 1.34 (1.13 to 1.58) | 0.001 | 1.36 (1.15 to 1.62) | <0.001 |

| Combined all-cause mortality and hospitalised HF (n=153) | 1.40 (1.26 to 1.56) | <0.001 | 1.29 (1.12 to 1.49) | <0.001 | 1.32 (1.14 to 1.53) | <0.001 |

| Non-fatal myocardial infarction (n=26) | 1.40 (1.07 to 1.83) | 0.016 | n.a. | n.a. |

Unadjusted and adjusted time-varying Cox regression models. Results of 1 SD higher in-study LV mass–wall stress–heart rate are presented as HR and 95% CI.

*Adjusted for sex, baseline hypertension and age, and time-varying body mass index, LV hypertrophy, LV ejection fraction and peak jet velocity.

†Adjusted also for prevalent atrial fibrillation use of beta-blocker treatment at baseline and time-varying left atrial diameter, stroke volume index and serum creatinine.

CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure; LV, left ventricular; n.a., not applicable.

Discussion

LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product and outcome

The present hypothesis-generating analysis from the large, prospective SEAS study extend previous evidence in hypertensive patients with LV hypertrophy,3 11 suggesting increased LV myocardial oxygen demand as a major demand-side predisposition to myocardial ischaemia and subsequent CV events in AS. Although concomitant coronary artery disease is an important cause of myocardial ischaemia, it is not a prerequisite.22 In LV hypertrophy caused by hypertension or severe AS, myocardial ischaemia has been demonstrated in absence of stenotic coronary artery disease.22–24 Although LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product was typically higher in patients with LV hypertrophy and the majority of these patients had concomitant hypertension, the associations with higher HRs of all-cause mortality and major CV events were independent of presence of LV hypertrophy, as well as independent of concomitant hypertension, higher body mass index and AS severity, all well-documented prognosticators in AS.13–15 21

LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product and LV systolic dysfunction

The transition from compensated LV hypertrophy to congestive heart failure in AS is driven by progressive cardiomyocyte death and myocardial fibrosis.25 Using contrast echocardiography, Galiuto et al found that myocardial hypoperfusion was associated with cardiomyocyte apoptosis in myocardial biopsies from patients with severe AS.24 In a study using late gadolinium enhancement cardiac MRI, Dweck et al found that among patients with moderate and severe AS, fibrosis was particularly present in the LV midwall in patients with higher LV mass, and associated with impaired prognosis.4 In line with these observations, patients with high LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product in the present study population had significantly lower LV midwall shortening, probably reflecting more advanced myocardial disease in this group.

LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product: relation to symptoms and CV risk factors

Previous studies have found concomitant hypertension in AS to be associated with higher combined valvuloarterial LV load and to influence LV adaptation and prognosis.13 26 Earlier development of AS-related symptoms has also been suggested in patients with combined AS and hypertension.27 The presence of LV hypertrophy was independently associated with onset of cardinal symptoms in a prospective study of 622 patients with AS by Pellikka et al.28 In a study of 58 patients with severe AS, Hansson et al used 11C-acetate positron emission tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance for measurement of myocardial oxygen consumption and myocardial external efficiency, respectively.29 However, myocardial oxygen consumption and myocardial external efficiency did not discriminate between asymptomatic and symptomatic patients. The present results add to this knowledge by demonstrating that concomitant hypertension was more common in AS patients with high LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product, suggesting that high myocardial oxygen demand in combined hypertension and AS may contribute to the observed earlier onset of heart failure symptoms and higher mortality in these patients.13 14 27 In line with previous findings in hypertension, use of beta-blocker treatment in AS was associated with lower HRs for these adverse outcomes.11 30

Study limitations

The SEAS study excluded patients with diabetes, renal failure and known coronary artery disease.15 Thus, the results should be applied with caution in less selected groups of AS patients. The prospective SEAS study was performed during the years 2002–2008, and the imaging protocol did not include mitral annulus velocities by spectral tissue Doppler or recording of tricuspid regurgitation by continuous wave Doppler, as recommended by current guidelines on assessment of LV diastolic function. The assessment of the associations of LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product with LV diastolic dysfunction was therefore limited. Finally, coronary artery disease was not systematically assessed in the SEAS study. In particular, diagnosis of myocardial ischaemia by cardiac MRI, positron emission tomography, contrast stress echocardiography or exercise testing was not performed. The association of LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product as an indirect measure of myocardial oxygen demand could therefore not be compared with direct assessment of myocardial oxygen consumption by positron emission tomography.29

Conclusion

In mostly hypertensive AS patients without known CV disease or diabetes participating in the SEAS study, higher LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product, an indirect measure of myocardial oxygen demand, was associated with higher all-cause mortality and higher HR for CV events, independent of well-known prognosticators in AS including stenosis severity and presence of LV hypertrophy and hypertension. Whether higher myocardial oxygen demand assessed by LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product contributes to impaired prognosis through induction of chronic myocardial ischaemia should be tested in future studies using modern non-invasive imaging methods for assessment of myocardial perfusion.

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject?

Presence of hypertension in aortic valve stenosis (AS) is associated with higher left ventricular (LV) mass and wall stress and predicts higher risk of ischaemic cardiovascular events and higher mortality. Increased LV mass, wall stress and heart rate all lead to increased LV myocardial oxygen demand in AS, which may predispose to myocardial ischaemia even in the absence of coronary artery disease. In hypertension, reduction of LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product by atenolol treatment was associated with improved prognosis.

What might this study add?

The present study demonstrates that higher LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product, an indirect measure of myocardial oxygen demand, was associated with earlier onset of heart failure symptoms and increased mortality, independent of presence of other prognosticators in AS including LV hypertrophy, hypertension, stenosis severity, sex, age, body mass index and LV ejection fraction.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

AS patients with high LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product are at increased risk for death and heart failure hospitalisation. Based on studies in hypertension, treatment with a beta-blocker may be initiated in asymptomatic AS patients with hypertension to reduce LV mass–wall stress–heart rate product and thereby myocardial oxygen demand to reduce risk for adverse events.

Footnotes

Contributors: EG and RD contributed to the conception and design of the work, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting and critical revision of the work. SS, HM, AR, JBC, EE and EB contributed to data collection and critical revision of the work. All authors gave final approval of the version published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: The SEAS echocardiography core laboratory was supported by the MSP Singapore Company, LLC, Singapore, a partnership between Merck & Co., and the Schering-Plough Corporation during study conduct from 2002 to 2008.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The SEAS study was approved by ethical committees in all study centres.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Devereux RB, Alderman MH. Role of preclinical cardiovascular disease in the evolution from risk factor exposure to development of morbid events. Circulation 1993;88:1444–55. 10.1161/01.CIR.88.4.1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, et al. . Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med 1990;322:1561–6. 10.1056/NEJM199005313222203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Palmieri V, et al. . Left ventricular wall stresses and wall stress–mass–heart rate products in hypertensive patients with electrocardiographic left ventricular hypertrophy. J Hypertens 2000;18:1129–38. 10.1097/00004872-200018080-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dweck MR, Joshi S, Murigu T, et al. . Midwall fibrosis is an independent predictor of mortality in patients with aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:1271–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liao Y, Cooper RS, McGee DL, et al. . The relative effects of left ventricular hypertrophy, coronary artery disease, and ventricular dysfunction on survival among black adults. JAMA 1995;273:1592–7. 10.1001/jama.1995.03520440046035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Galderisi M, de Simone G, D’Errico A, et al. . Independent association of coronary flow reserve with left ventricular relaxation and filling pressure in arterial hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2008;21:1040–6. 10.1038/ajh.2008.226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Irvine T, Kenny A. Aortic stenosis and angina with normal coronary arteries: the role of coronary flow abnormalities. Heart 1997;78:213–4. 10.1136/hrt.78.3.213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Koyanagi S, Eastham CL, Harrison DG, et al. . Increased size of myocardial infarction in dogs with chronic hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy. Circ Res 1982;50:55–62. 10.1161/01.RES.50.1.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koyanagi S, Eastham C, Marcus ML. Effects of chronic hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy on the incidence of sudden cardiac death after coronary artery occlusion in conscious dogs. Circulation 1982;65:1192–7. 10.1161/01.CIR.65.6.1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Inou T, Lamberth WC, Koyanagi S, et al. . Relative importance of hypertension after coronary occlusion in chronic hypertensive dogs with LVH. Am J Physiol 1987;253(5 Pt 2):H1148–H1158. 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.5.H1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Devereux RB, Bang CN, Roman MJ, et al. . Left ventricular wall stress-mass-heart rate product and cardiovascular events in treated hypertensive patients: LIFE study. Hypertension 2015;66:945–53. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.05582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Saeed S, Gerdts E. Managing complications of hypertension in aortic valve stenosis patients. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2018;16:897–907. 10.1080/14779072.2018.1535899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rieck ÅE, Cramariuc D, Boman K, et al. . Hypertension in aortic stenosis: implications for left ventricular structure and cardiovascular events. Hypertension 2012;60:90–7. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.194878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gerdts E, Rossebø AB, Pedersen TR, et al. . Relation of left ventricular mass to prognosis in initially asymptomatic mild to moderate aortic valve stenosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8:e003644 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.003644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rossebø AB, Pedersen TR, Boman K, et al. . Intensive lipid lowering with simvastatin and ezetimibe in aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1343–56. 10.1056/NEJMoa0804602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. . Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2005;18:1440–63. 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, et al. . ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. The Task Force for the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2017;2017:2739–91. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gaasch WH, Zile MR, Hoshino PK, et al. . Stress-shortening relations and myocardial blood flow in compensated and failing canine hearts with pressure-overload hypertrophy. Circulation 1989;79:872–83. 10.1161/01.CIR.79.4.872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Simone G, Devereux RB, Koren MJ, et al. . Midwall left ventricular mechanics. An independent predictor of cardiovascular risk in arterial hypertension. Circulation 1996;93:259–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Devereux RB, de Simone G, Pickering TG, et al. . Relation of left ventricular midwall function to cardiovascular risk factors and arterial structure and function. Hypertension 1998;31:929–36. 10.1161/01.HYP.31.4.929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bahlmann E, Gerdts E, Cramariuc D, et al. . Prognostic value of energy loss index in asymptomatic aortic stenosis. Circulation 2013;127:1149–56. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.078857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stanton T, Dunn FG. Hypertension, Left Ventricular Hypertrophy, and Myocardial Ischemia. Med Clin North Am 2017;101:29–41. 10.1016/j.mcna.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lønnebakken MT, Rieck AE, Gerdts E. Contrast stress echocardiography in hypertensive heart disease. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2011;9:33 10.1186/1476-7120-9-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Galiuto L, Lotrionte M, Crea F, et al. . Impaired coronary and myocardial flow in severe aortic stenosis is associated with increased apoptosis: a transthoracic Doppler and myocardial contrast echocardiography study. Heart 2006;92:208–12. 10.1136/hrt.2005.062422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hein S, Arnon E, Kostin S, et al. . Progression from compensated hypertrophy to failure in the pressure-overloaded human heart: structural deterioration and compensatory mechanisms. Circulation 2003;107:984–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rieck AE, Gerdts E, Lønnebakken MT, et al. . Global left ventricular load in asymptomatic aortic stenosis: covariates and prognostic implication (the SEAS trial). Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2012;10:43 10.1186/1476-7120-10-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Antonini-Canterin F, Huang G, Cervesato E, et al. . Symptomatic aortic stenosis: does systemic hypertension play an additional role? Hypertension 2003;41:1268–72. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000070029.30058.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pellikka PA, Sarano ME, Nishimura RA, et al. . Outcome of 622 adults with asymptomatic, hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis during prolonged follow-up. Circulation 2005;111:3290–5. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.495903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hansson NH, Sörensen J, Harms HJ, et al. . Myocardial oxygen consumption and efficiency in aortic valve stenosis patients with and without heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:pii: e004810 10.1161/JAHA.116.004810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bang CN, Greve AM, Rossebø AB, et al. . Antihypertensive treatment with β‐blockade in patients with asymptomatic aortic stenosis and association with cardiovascular events. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6:pii: e006709 10.1161/JAHA.117.006709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]