We propose a novel conceptual model for PPC integration into the traditionally cure-oriented CICU using interdisciplinary PPCCs.

Abstract

Integration of pediatric palliative care (PPC) into management of children with serious illness and their families is endorsed as the standard of care. Despite this, timely referral to and integration of PPC into the traditionally cure-oriented cardiac ICU (CICU) remains variable. Despite dramatic declines in mortality in pediatric cardiac disease, key challenges confront the CICU community. Given increasing comorbidities, technological dependence, lengthy recurrent hospitalizations, and interventions risking significant morbidity, many patients in the CICU would benefit from PPC involvement across the illness trajectory. Current PPC delivery models have inherent disadvantages, insufficiently address the unique aspects of the CICU setting, place significant burden on subspecialty PPC teams, and fail to use CICU clinician skill sets. We therefore propose a novel conceptual framework for PPC-CICU integration based on literature review and expert interdisciplinary, multi-institutional consensus-building. This model uses interdisciplinary CICU-based champions who receive additional PPC training through courses and subspecialty rotations. PPC champions strengthen CICU PPC provision by (1) leading PPC-specific educational training of CICU staff; (2) liaising between CICU and PPC, improving use of support staff and encouraging earlier subspecialty PPC involvement in complex patients’ management; and (3) developing and implementing quality improvement initiatives and CICU-specific PPC protocols. Our PPC-CICU integration model is designed for adaptability within institutional, cultural, financial, and logistic constraints, with potential applications in other pediatric settings, including ICUs. Although the PPC champion framework offers several unique advantages, barriers to implementation are anticipated and additional research is needed to investigate the model’s feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy.

The goal of pediatric palliative care (PPC) is to provide support and reduce suffering for children with serious illnesses and their families.1 These objectives are accomplished through expert interdisciplinary assessment and management of physical and psychological symptoms, provision of high-quality communication to facilitate decision-making and advance care planning, attention to psychosocial and spiritual suffering, enhancement of quality of life, and provision of emotional, logistic, grief, and bereavement support.2–5 The National Academy of Medicine has long advocated for the provision and evaluation of child- and family-centered PPC,6 and reports slow widespread adoption of the recommendation.7 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) professional guidelines further endorse concurrent PPC and disease-directed care as best practice.1,2,5 Integration of PPC into the management of children with serious illnesses has been identified as a key research priority by expert clinicians and bereaved families.5,8 An emerging evidence base supports integration of palliative care (PC) in the ICU, with authors of a growing body of literature describing direct benefits for patients, families, and staff.9–11 As a result, the Society of Critical Care Medicine recommend PC be considered a key component of comprehensive critical care and a core ICU physician competency.12–15

Despite growing evidence and recommendations that practice of and responsibility for PC must be shared by all clinicians and not just specialists,16 adoption of PPC within cardiac ICUs (CICUs) has been particularly slow. A high proportion of children with advanced heart disease are referred late to PC services, or not at all.17–19 Pediatric providers have been encouraged to investigate novel “service delivery models to improve access, outcomes and cost-effectiveness.”2,5 Although several models have been proposed to facilitate incorporation of PC into adult and pediatric oncology as well as other ICU settings,11,15,20–22 these have inherent disadvantages and inadequately address unique aspects of the CICU environment. Traditional models for integration of PPC into the CICU place significant burden on subspecialty PPC teams and fail to recognize specific aspects of the patient population and overcome the survival-focused culture. Additionally, these models do not encourage the practice of PPC by all CICU interdisciplinary team members, instead creating silos of skill sets within disciplines and specialties.

In this article, we review the rationale for focusing attention in the CICU, discuss how current models for PC integration in different care settings are insufficient for the CICU, and present a novel champion-based conceptual framework to optimize integration of PPC within the CICU, with potential adaptability for use in other care settings.

Rationale for Focusing on the CICU Setting

The current CICU community faces challenges necessitating exploration of innovative approaches to improve PPC integration throughout illness trajectory. Although many challenges are shared across ICU settings, they are often more extreme and common in the CICU, and recent high profile cases have placed pediatric critical care end of life (EOL) management under public scrutiny.23,24 Additionally, CICU-specific challenges exist, including rising prognostic uncertainty, availability of invasive technologies, cardiac-surgical subspecialty involvement, and the focus on survival outcomes.

Advances in medical and surgical techniques have decreased CICU and PICU mortality to <3% in high-income countries.25–27 Certain pediatric cardiac populations, however, continue to suffer high morbidity and mortality, and improvements in survival in the CICU may unfortunately result in greater disability and increased technological dependence.25,28–32 Patients with single-ventricle physiology, for example, have a 6-year transplant-free survival of only 59% to 64%, with a journey that involves multiple surgical procedures and invasive catheterizations in early childhood.33 Frequent and prolonged CICU admissions are experienced by many children with cardiac disease and their families.17,32,34–36 The longitudinal nature of pediatric cardiac morbidity has important psychosocial implications for patients and families that may be mitigated by early PPC interventions.37–40 Burdens of survivorship are increasingly recognized, and the substantial increase in adults with congenital heart disease12,28 requires improved understanding of patients’ and families’ values and preferences. Readdressing patient and family goals across the illness experience and disease trajectory is paramount to the provision of optimal care and could be improved with earlier integration of PC principles. In addition, although acute cardiac events and crises do occur in previously healthy children,41 children with complex chronic conditions are increasingly cared for in the CICU.29,32,42 Individuals with PC and communication expertise have the potential to positively impact this patient population’s health care experience.37–39,43,44

Greater complexity in congenital heart disease combined with developments in cardiac-surgical techniques and mechanical support options have increased prognostic uncertainty for patients, families, and medical teams.25 Although most pediatric patient deaths in the CICU follow a decision to limit or discontinue life-sustaining treatment,18,25,45 invasive technologies now exist, enabling prolonged ventilator and circulatory support in patients with variable chances of recovery.46,47 Additionally, interventions targeted at symptom relief can paradoxically be burdensome; for example, repeated catheterization procedures for balloon dilations for pulmonary vein stenosis. Prognostic uncertainty, divergent views on treatment goals, and a lack of consensus on what constitutes a good outcome create ethical dilemmas and may contribute to conflict with families and between interdisciplinary team members. Clinicians are increasingly faced with providing treatment that is at odds with their moral compass,32,34,48–52 highlighting the importance of high-quality, value-based communication and development of trusting relationships between families and medical team members to provide goal-concordant care and mitigate moral distress.38,39,44,53–56

Traditionally, the cure-oriented CICU culture has resulted in delayed or absent involvement of subspecialty PPC.17–19 Historically, in-hospital mortality has been the primary quality metric for pediatric cardiac surgery programs and wider CICUs.25–27,57,58 This singular focus on mortality outcomes contributes to the survival-focused culture and disincentivizes PPC incorporation into the care of children with cardiac disease and their families.25,57–59 There is substantial evidence, however, in favor of interventions promoting earlier involvement of PC experts as a strategy to reduce ICU resource use without adversely impacting mortality rates.13,60 In addition, unlike most other ICU settings, the CICU team includes cardiac-surgical or interventional subspecialists that are closely involved longitudinally in patient care and responsible for offering and performing procedures. These team members add a layer to an already complex health care system, playing a prominent role in clinical decision-making and discussions with families, emphasizing the importance of their specific buy-in and an interdisciplinary approach.

This contemporary CICU landscape offers a compelling environment within which to examine strategies to improve the incorporation of PPC principles as part of comprehensive patient care encompassing medical, psychosocial, and spiritual well-being.3

Current Models of PC Integration

Several models have been employed through clinical initiatives to improve the quality and integration of PC in different clinical settings, each of which offers certain advantages and significant disadvantages, including barriers to implementation in the CICU (Table 1).9,11,15,21,22,61–63 Traditional practical approaches to ICU-based PC include consultative and integrative models. Given the challenges inherent to these models and recognizing that many patients may benefit from basic PC principles, clinicians and researchers in neonatal and adult ICU settings have recently advocated for a mixed model combining elements from both paradigms.9,11,41,60,63–65 In the context of clear benefits of early, concurrent PC for patients with high-risk cancer,66–69 both adult and pediatric oncology communities are exploring embedded models to improve PC integration as part of comprehensive cancer care.21,22,70–73 Lastly, ICU physicians with secondary PC skills serving as local microcommunity experts has been recently described.15,74,75

TABLE 1.

Current Models of PC Integration With Specific Advantages and Disadvantages Relevant to the Cardiac Intensive Care Setting

| Models | Consultative | Integrative | Mixed | Embedded |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | • Specialist PC clinicians function as external expert consultants | • PC principles are practiced routinely by the ICU team as standard of care | • Core PC elements are provided by the ICU team as part of their clinical practice (primary PC) | • Specialist PC clinicians are embedded within primary ICU teams and serve as experts from within to promote access to and provision of high-quality PC |

| • PC experts work alongside but separate from the critical care team to provide PC | • Based on the assumption that all ICU patients and families may benefit from provision of basic PC throughout disease course | • Expert subspecialists are available to aid the ICU team with management of complex patients whose needs exceed the skills or time capabilities of the primary team | • Embedding PC team members has been implemented within oncology and trialed in adult ICU settings | |

| • Currently the most prevalent model of PC service delivery in pediatric hospitals | • Proposed as the best model for PC integration in resource-limited settings | |||

| Advantages | • Enables translocation of PC across care settings (both inpatient and in the community) | • Aligns with NAM recommendations and critical care task forces | • All patients may benefit as basic PPC principles are assimilated into routine care as opposed to exclusively at EOL | • Opportunity for relationship building between subspecialty providers and the ICU team |

| • Overcomes the shift work and isolated nature of ICU staffing and units | • Highlights PC skills as core competencies for all ICU physicians | • Subspecialty services are reserved for challenging cases maximizing their productivity | • Embedded PC specialists provide continuity of care over time and teach PC principles to ICU staff | |

| • Provides additional external support for ICU staff in challenging and distressing patient and family care situations | • Delivery of PC principles is not dependent on staffing or workforce issues of the subspecialty PPC team and reaches greater numbers of patients | • Aligned with standard ICU practices for referrals: ICUs manage infections; however, in refractory cases, infectious disease specialists are consulted for expert guidance | • Increases and normalizes PC visibility in the ICU | |

| Disadvantages | • Growing demand overwhelms specialist PC team capacity | • Necessitates ICU practitioners having sufficient time, interest, and skills to learn and sustain basic PC practices in addition to critical care knowledge | • Requires buy-in from multiple stakeholders | • An individual PC clinician as an embedded expert can be isolated in the CICU and would require additional training on ICU-specific management |

| • Access to PC services and resources for only a small select group of patients and families | • Lack of continuity of PC delivery across clinical settings outside the CICU | • Necessitates ICU practitioners having sufficient time, interest, and skills to learn and sustain basic PC practices in addition to their critical care skills and knowledge | • No continuity is provided across care settings | |

| • PC referral and timing is subject to physician preferences and biases | • Does not address when and how to include subspecialty PPC teams for patients with complex symptoms or families that may require additional psychosocial support | • Subspecialty PC referral and timing subject to ICU clinician preferences and biases | • Requires tremendous resources from the subspecialty PC team and acceptance of outside input from the ICU | |

| • Does not allow for or enable education of the CICU providers | • Does not address how CICU clinicians receive training in PC principles and focuses on physicians rather than the interdisciplinary team | • Does not address how CICU clinicians receive or obtain training in PC principles | • This model is not interdisciplinary, with PC represented by a single clinician immersed in the foreign team with limited understanding of the team dynamics and culture | |

| • Adds another layer to an already complex health care system. PPC is seen as separate, and without a shared mindset, silos of care may impede collaborative practice, disrupting existing therapeutic relationships | • Does not address integration of psychosocial and support staff | • Fails to address how to integrate psychosocial and support team members |

NAM, National Academy of Medicine.

Existing models both have general inherent disadvantages and insufficiently address specific challenges currently facing the CICU, particularly around how and when to involve the subspecialty PC team to avoid PPC overextension and burnout and how CICU clinicians will obtain skills in primary PC. These models fail to account for the CICU culture, patient population, interdisciplinary nature, and team dynamics in which physiology, technology, and interventions may result in symptoms and associated distress that is different from other pediatric settings and requires clinicians with an enhanced understanding of this unique environment.

PPC Champions: A Proposed Model for Integrating PC in the CICU

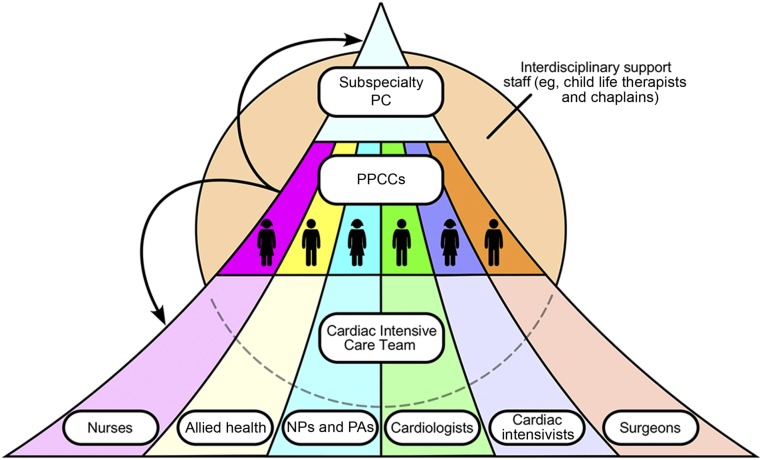

We propose a novel conceptual framework to improve provision of PPC in the CICU setting using pediatric palliative care champions (PPCCs) (Fig 1, Table 2). Because the goal of PPC is to provide support, ameliorate suffering, and maximize quality of life for seriously ill children and their families in alignment with their goals and preferences,2,3 we advocate that all CICU clinicians should provide PPC.16 Because successful PPC-CICU integration requires mutual understanding of each respective discipline’s goals, missions, and skills, this model uses CICU-based champions. Our approach fosters a shared mindset, acknowledges the need for a unique understanding of CICU culture, has an interdisciplinary focus, and emphasizes education, which are not elements across existing care models. Using PPCCs means that greater numbers of patients in the CICU are exposed to PC principles and the workload is shared with the subspecialty PC team, lessening the burden on this group of individuals and thus overcoming many inadequacies of other models. Ultimately, the goal of PPCCs is to encourage earlier incorporation of PC principles into the care of children with critical cardiac disease and their families. These champions will be well positioned and empowered to extend the impact of PC, offering the next frontier to provide holistic care to patients and families in the CICU.

FIGURE 1.

Proposed PPCC model for integration of PPC into the CICU. PPCCs are identified by the CICU interdisciplinary team. PPCCs receive additional training in PC and serve as educational resources within the unit, improve use of subspecialty PPC for complex patients, better incorporate interdisciplinary support staff, and fulfill an operational role. Allied health includes social workers and respiratory therapists, for example. NP, nurse practitioner; PA, physician assistant.

TABLE 2.

PPCC-Based Model Summary

| PPCC-Based Model Summary | |

|---|---|

| Description | Multidisciplinary CICU-based PPCCs |

| Interested clinicians receive training in communication and PC principles | |

| Three role domains: clinical, educational, and operational | |

| Encourages earlier and long-standing incorporation of PC principles into the care of children with critical cardiac disease | |

| Advantages | PPCCs have extensive expertise in both cardiac medicine and PC. |

| As integral members of the CICU interdisciplinary team, PPCCs have an improved understanding of CICU culture and team dynamics to facilitate PPC integration and create a shared mindset. | |

| Bidirectional knowledge transfer between PPCCs and PPC subspecialists can improve symptom management and care needs of the patient population both in the CICU (by PPCCs) and to wider PPC patients (through subspecialty PPC providers). | |

| Improved primary PC delivery with empowered champions providing care and education; | |

| Specialist experts and resources can be prioritized for the most complex patients and families. | |

| Extends the impact and reach of PC within the CICU, providing holistic care to a greater proportion of patients and their families. | |

| Disadvantages | Requires institutional support and buy-in from CICU providers and support for upfront and ongoing training of PPCCs |

| Needs a robust institutional subspecialty PPC team to support program development and training as well as PPCC provider support and mentorship | |

| There are potential challenges over recruitment and retention of PPCCs and the possibility of role confusion and/or misconception | |

| Feasibility | The PANDA PC Team: Panda Cubs |

| This QI project at Children’s National involves an intensive PC educational and mentorship program for physicians, advanced practice nurses, registered nurses, and social work and child life staff, including from the CICU. The year-long program includes a 2-d course adapted from the ELNEC-PPC and EPEC-Pediatrics quarterly educational sessions, monthly rounding with discussions of case studies, and a final 1-d educational conference. Participants have mentorship and are expected to undertake a unit-based QI project to establish meaning and integrate knowledge into practice. | |

| PC in the Heart Center | |

| Department-funded training at the Boston Children’s Hospital trained 2 physicians, a cardiac intensivist and cardiologist, to complete the PCEP course with additional support to undertake rotations with the subspecialty PPC services to augment primary PC delivery in the heart center. An interdisciplinary communication and PC working group was created to better understand obstacles and implement solutions to the complex decision-making and communication surrounding the care of children with advanced heart disease, with research including parent, physician, and nursing surveys on symptom burden, prognostic awareness and communication, and a monthly journal club PC interest group. | |

| Mid-career PC Training Program | |

| This educational pilot at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia was funded by the Milbank Foundation. Two physicians, a cardiac intensivist, and a general pediatrician working on the complex care team participated in the program with the goal of building a PC skillset for their ongoing work within their core teams. Each attending physician spent a few weeks rotating with the consulting inpatient PC team and became trained facilitators for the VitalTalk communication skills program. Each built on their experiences to enhance primary palliative skills and awareness within their core teams and helped educate the PC team about the conditions their core teams treated. |

ELNEC, End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium; EPEC, Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care; PCEP, Palliative Care Education and Practice.

Developing and Training PPCCs

Ideally, PPCCs are drawn from different disciplines within the CICU team, including bedside nurses, advanced practice nurses, physician assistants, respiratory and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapists, social workers, and physicians (CICU fellows and attending physicians, cardiologists, and cardiovascular surgeons) to promote seamless PPC integration within the CICU environment. A selection of dedicated and self-motivated PPCCs is essential to the success of this care model. Ideally, PPCCs should self-identify on the basis of personal or professional interest in PC, with subsequent screening and final selection determined by a panel that includes CICU and PPC leadership. To encourage participation and investment, collegiality with continued education, and debriefing and to create redundancy as a buffer against attrition, we recommend inclusion of ≥2 PPCCs from each discipline. Ideally, 1 PPCC would be in training or early career and the other would have more clinical experience for mentorship (Fig 1).

Within this paradigm, clinicians who demonstrate an interest in PPC would receive additional training and education to become champions. Specific training should be adapted to meet the participant needs from various clinical disciplines and consider institutional factors such as expert subspecialty PPC availability (see Table 3, Supplemental Information). We advocate for the training to encompass 3 domains: (1) didactic sessions and education modules covering foundational PPC principles, (2) experiential communication training with an emphasis on enhancing adult learning through group discussion and role-play, and (3) immersive training in which PPCCs participate as learners on subspecialty PPC clinical rotations. To facilitate PPCC training, cardiac-specific PPC training programs, education courses, and curricula should be developed that are focused on cardiac case-based scenarios, advanced symptom assessment, and management skills unique to children with heart disease. Examples of specific programmatic details from institutions exploring this model are discussed in Table 2.

TABLE 3.

Training and Development of PPCCs

| PPCC Training and Development | Example Training Courses by Discipline |

|---|---|

| Didactic education modules, courses, and seminars | ELNEC courses from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Educational curriculum on palliative and EOL care principles: https://www.aacnnursing.org/ELNEC |

| EPEC-Pediatrics | |

| Comprehensive curriculum to address the needs of children and their families, pediatric oncologists, and other pediatric clinicians: https://www.bioethics.northwestern.edu/programs/epec/curricula/pediatrics.html | |

| Experiential communication skills courses, including training to facilitate communication teaching sessions for CICU staff | Harvard Medical School Center for Palliative Care courses: https://pallcare.hms.harvard.edu/courses |

| PAPC: 2-d course for interdisciplinary providers on PC principles | |

| PCEP: 2-wk intensive course on PC principles and communication training | |

| VitalTalk courses: http://vitaltalk.org/courses/ | |

| Half- or full-day communication training | |

| Faculty development course | |

| Rotation Experiences | Clinical rotations with the subspecialty PPC team |

| 1-y hospice and palliative medicine fellowship (ACGME accredited) | |

| 1-mo rotations with PPC team for CICU and cardiology trainees and advanced practice nurses | |

| Ongoing participation with attendance at team meetings and service-based grand rounds and presentations |

ACGME, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; ELNEC, End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium; EPEC, Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care; PAPC, Practical Aspects of Palliative Care; PCEP, Palliative Care Education and Practice.

PPCC Roles

We envision several ways in which PPCCs may improve care delivery in the CICU (Table 4). First, PPCCs’ clinical role could include liaising between CICU, subspecialty PPC, and interdisciplinary support staff. PPCCs could serve as a bridge to subspecialty PPC services, with the goal of optimizing appropriate access to and use of consultative services for challenging cases. Interdisciplinary PPCCs would work in collaboration with CICU-specific supportive staff, including psychologists, child life specialists, and chaplains to augment support for patients and families. Notably, there is a lack of evidence-based guidelines to inform eligibility criteria for PPC referral in the context of cardiac disease.28 We advocate for PPCCs to lead collaborative efforts between key stakeholders in the CICU and subspecialty PPC clinicians to create consensus referral criteria that align with PC principles.

TABLE 4.

Roles and Responsibilities of PPCCs in the CICU

| Domain | Description of Activity |

|---|---|

| Clinical | Liaise with subspecialty PPC team and assist CICU team with why, when, and how to consult the PC team for more complex patients or situations. |

| Develop CICU-specific guidelines to identify patients who may benefit from subspecialty consultation. | |

| Model optimal language to use in introducing the subspecialty PPC team to patients and families. | |

| Improve the integration of interdisciplinary support staff into daily clinical care. | |

| PPCCs attend regular psychosocial team meetings with PPC subspecialists and provide regular medical updates to members of the interdisciplinary support teams to improve spiritual, material, and psychological support for patients and families in the CICU. | |

| Educational | Improve provision of primary PC routinely provided in the CICU by leading discipline-specific educational sessions and communication trainings. |

| Brief, interactive, didactic, and case-based sessions can be incorporated into existing unit administrative or educational meetings. | |

| Topics may include symptom assessment and management, identification of patients who warrant expert or specialist PPC consultation, and provision of high-quality care at the EOL. | |

| Specific communication seminars could focus on eliciting patient and family preferences regarding information delivery, providing difficult news in a straightforward and clear manner, responding to emotion, assessing patient and family hopes and worries, cultivating prognostic awareness and making goal-based recommendations. | |

| Operational | Create CICU-specific checklists, protocols, and standard operating procedures (eg, a checklist for compassionate discontinuation of ventilator support or extracorporeal support). |

| Develop and identify CICU-specific metrics to evaluate quality of care. Proposed quality metrics may include patient and family quality of life, prospective reported symptom assessment, satisfaction with communication, goal concordance of EOL care, and psychosocial well-being. | |

| Develop and implement QI projects. | |

| Example QI projects may include the development of EOL pathways, mechanical support deactivation procedures, PC passports for emergency department presentations or admissions to outside hospitals (documents that detail the wishes of patients and families), or updating electronic medical record documentation processes. |

Second, trained PPCCs would educate other CICU staff on basic PPC principles, with the goal of facilitating routine delivery of core PC elements by the CICU team (primary PC). Life-prolonging therapies engender important differences in care for patients dying in the CICU, and education must cover strategies for managing cardiac devices at EOL (eg, pacemakers, implantable cardiac defibrillators, and ventricular assist devices).46,76,77 Discipline-specific advanced communication training and practice may include skills to aid navigation of prognostic uncertainty with provision of anticipatory guidance around risk for sudden death in cardiac disease. Shorter communication skills didactics can be incorporated into routine simulation exercises within the CICU (eg, conversations at the time of resuscitation events).

Third, PPCCs would play an integral role in optimizing operational processes and policies within the CICU, including development of CICU-specific protocols, checklists, and standard operating procedures; identification of metrics to better define quality of care in the CICU; and design and implementation of quality improvement (QI) projects at the intersection of the PPC and CICU fields.25,59,78–81 PPCC representation in existing hospital-wide PPC programs would aid collaboration; such partnerships are particularly important in the context of rapid expansion of long-term mechanical support options for children with cardiac disease, including their use as destination therapy.46,76,77

Benefits of the PPCC Model

The PPCC framework offers several unique advantages over other care models: sharing the workload with overextended subspecialty PPC services; improving primary PC through education interventions, extending the reach of PC and integrating principles into patient care earlier; and creating mutual understanding through an interdisciplinary focus.

Perhaps most importantly, the PPCC framework is more sustainable than current models, matching supply and demand. In the context of a rapidly growing strain on subspecialty PC teams in the form of clinical overextension, the PPCC approach can ensure the appropriate use and timing of subspecialty PPC involvement to overcome workforce shortages or overextension of current PPC staff. The knowledge PPCCs impart to PC experts can also improve symptom management and care needs of patients with cardiac disease outside the CICU.

The emphasis on PPCC-led interdisciplinary education interventions for all CICU providers to improve primary PC is a unique aspect to the model. This approach ensures that greater numbers of patients in the CICU receive high-quality primary PC earlier in their illness trajectory. PPCCs may facilitate debriefings and provide constructive feedback after family meetings or difficult conversations with the goal of enhancing overall team communication skills in the context of sharing difficult news, discussing goals of care, providing clear prognostic information, and making preference-based recommendations. Because patients increasingly survive acute CICU hospitalizations and consequently live with significant morbidities, early introduction of PC principles and interdisciplinary support staff may help prepare and support patients and families for challenges that follow ICU discharge.

Champions have extensive clinical experience across both cardiac critical care and PC domains, uniquely positioning them to bridge the gap between the PPC and CICU to create a shared mindset. Their expertise and understanding of pediatric cardiac medical conditions encountered is of benefit to consulting PPC subspecialists, extending the impact beyond the CICU. PPCCs can provide continuity of care for patients, families, and other health care providers across the course of prolonged single and serial CICU hospitalizations. Their consistent presence in the CICU further makes PPCCs readily available for colleagues to curbside with PC-related questions or concerns. Given their role in the CICU, PPCCs are well positioned to understand the unspoken culture of the CICU and key aspects of team dynamics; as such, PPCCs may be more successful at navigating challenging interpersonal dynamics and advocating for PC principles and consultations as compared with outsider providers. Involving surgical team representatives trained in PC principles will further help overcome specific barriers to PPC integration that are more unique to the CICU.

Overcoming Barriers to Implementation of the PPCC Model

The PPCC approach requires access to subspecialty PPC consultants, with sufficient expert bandwidth to support champion training and provide ongoing guidance across programmatic development. A commitment and receptivity from CICU staff to strengthen internal capabilities for delivering PC principles and collaborate across specialties and disciplines will be essential.11 To develop a successful program and to ensure PPCC recruitment and retention, protected operational and education time is imperative. Institutional or departmental funding will be required to subsidize PPCC training, and discipline- and institution-dependent academic and fiscal incentives will be needed to facilitate educational and operational activities. Physicians on faculty who serve as PPCCs should have protected time for PC teaching, training, and research activities built into their promotional track; nurses who serve as PPCCs should have their role recognized in yearly assessments and reviews that afford upward mobility on their respective promotional tracks as well.

Like other unit-specific care models, the PPCC model does not ensure continuity across all care settings. Another anticipated barrier may involve role confusion, particularly when implicit expectations of cure are prevalent and PC referral may be perceived as synonymous with giving up.5,19,41,54 To address these issues, we recommend that PPC specialists join CICU rounds weekly and cofacilitate educational sessions with an eye toward dispelling myths and reinforcing respective roles within the care team.82 PPC subspecialty participation in regular interdisciplinary CICU rounds also enables identification of patients who may benefit from additional support during their time in the CICU or after transfer or discharge. We propose a gradual transition of care for those patients and families benefiting from additional support after transfer and suggest that PPCCs introduce the subspecialty PPC team several days before the proposed discharge. A close relationship between PPCCs and PPC subspecialists should be maintained involving mentorship and supervision, with an ongoing commitment to education, support, and debriefing through case discussions to ensure the delivery of high-quality PPC in the CICU and to guide educational and QI activities. PPCCs will need to prove their value without overstepping their role; we advocate for clear a priori demarcation of PPCC responsibilities and objectives, ideally defined collaboratively by CICU and PPC leadership. To ensure optimal dissemination of critical information regarding conversations about goals of care, advance directives, and EOL planning, robust processes and clear expectations for high-quality documentation must also be established.

The key purpose of this novel conceptual model integrating PPC in the CICU is to improve outcomes for critically ill pediatric patients and their families by providing holistic care throughout illness trajectory. We hypothesize that this care model may also help to improve staff well-being and reduce provider distress. Historically, it has been difficult to identify rigorous outcome measures to evaluate quality in PPC; the lack of benchmarks and multidimensional instruments means that demonstrating a quantifiable benefit to interventions is an inherent challenge and a priority for PPC research.8,80,81,83,84 Despite this difficulty, we propose several evaluable metrics after PPCC model implementation: (1) change in knowledge and comfort level of primary CICU providers dealing with EOL after PPCC education interventions evaluated through established questionnaires85,86; (2) improved quality of care and symptom management at the EOL in the CICU examined by using patient and family surveys and existing pediatric critical care instruments for staff perspectives59; and (3) enhanced integration of PPC principles and education on goal-concordant care could conceivably result in greater alignment with families and ameliorate moral distress, measurable with validated tools.48

Finally, strong institutional support with financial backing across interdisciplinary teams is essential for the success of this or any other model.41 Despite increasing uptake, the role of clinical champion remains empirically underdeveloped in health services literature, with no quantitative data inferring direct benefits.87 Because the true value of a PPCC model remains unknown, we acknowledge that institutional administrations may be wary of supporting implementation of a conceptual model without data demonstrating efficacy and cost savings. Implementation logistics and frameworks must be tailored to meet the needs of specific institutions to encourage buy-in. We recommend the use of center-specific needs assessments to adapt components of this proposed model to individual institutional needs. Although early exploration piloting elements of this framework in the CICUs at 3 major pediatric institutions illustrates feasibility of model implementation (Table 2), we advocate for additional collaborative investigation between clinicians and researchers at the intersection of CICU and PPC to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of integrative holistic care models to move the field forward.

Adaptation of the PPCC Model to Other Settings

Although the PPCC model for integration was designed for the CICU, elements of this model can potentially be adapted to other clinical settings, particularly other ICUs or pediatric subspecialties such as oncology, gastroenterology, pulmonology, neurology, and genetics and/or metabolism. These care environments experience similar challenges to the CICU: specific conditions with high morbidity and mortality; increasing reliance on medical technologies and greater comorbidities; prolonged length of stay; inherent uncertainty; and associated patient, family, and team distress.5,32,34,36,48,88 The training and disciplines represented by PPCCs may differ based on the care setting, potentially including nutrition, pharmacy, general surgery, and/or respiratory therapists based on the specific unit and interdisciplinary team members, with additional modifications required to adapt to in- and outpatient settings for some subspecialties.

Importantly, the PPCC model also offers a feasible approach for smaller programs or mixed pediatric and cardiac centers without access to subspecialty PPC services. Providers can receive external training as champions in a larger center, returning to their institution to incorporate PC within their local environment. PPCCs in this scenario should retain close communication with subspecialty PPC clinicians at larger institutions to allow for ongoing education, mentorship, and debriefing.

Conclusions

Improving the delivery of PC principles for patients in the CICU is essential to ensuring provision of high-quality care within the changing landscape of CICU practice. The PPCC approach, developed through interdisciplinary collaboration and consensus-building across departments and institutions, offers a novel model for integration of PPC into the CICU setting. The PPCC model offers several unique advantages over other care models both sharing the workload with overextended subspecialty PPC services, extending the reach of PPC in the CICU through education interventions and a unique interdisciplinary focus. Application of the proposed framework requires realistic assessment of the cultural, financial, personnel, and logistic constraints of target institutions before implementation, with the potential to be adapted to other clinical settings. Clinical exploration of the generalizability and dissemination capacity of the model across institutions is needed to determine overall feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of a PPCC approach toward optimizing the care of patients and families in the CICU.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michele Panaccione, Christine Rachwal, and Dorothy Beke as well as Shana Swartz, Nick Purol, and Arden O’Donnell for their support and CICU nursing and social work perspectives on the PPCC model.

Glossary

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- CICU

cardiac ICU

- EOL

end of life

- PC

palliative care

- PPC

pediatric palliative care

- PPCC

pediatric palliative care champion

- QI

quality improvement

Footnotes

Contributed equally as co-first authors.

Drs Moynihan and Snaman conceptualized and designed the proposed model, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Morrison, Wolfe, Dewitt, Sacks, Hwang, and Thompson and Ms LaFond and Ms Bailey revised and edited the proposed model and the manuscript for important intellectual content; Drs Kaye and Blume conceptualized and designed the proposed model and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: No external funding.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Bioethics and Committee on Hospital Care. Palliative care for children. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2 pt 1):351–357 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Section on Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Committee on Hospital Care Pediatric palliative care and hospice care commitments, guidelines, and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):966–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogetz JF, Ullrich CK, Berry JG. Pediatric hospital care for children with life-threatening illness and the role of palliative care. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014;61(4):719–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter BS. Pediatric palliative care in infants and neonates. Children (Basel). 2018;5(2):E21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang TI, Munson D, Hwang J, Feudtner C. Integration of palliative care into the care of children with serious illness. Pediatr Rev. 2014;35(8):318–325; quiz 326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Appendix B: Recommendations of the Institute of Medicine’s Reports Approaching Death (1997) and When Children Die (2003): Progress and Significant Remaining Gaps Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015:407–442 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker JN, Levine DR, Hinds PS, et al. Research priorities in pediatric palliative care. J Pediatr. 2015;167(2):467.e3–470.e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boss R, Nelson J, Weissman D, et al. Integrating palliative care into the PICU: a report from the Improving Palliative Care in the ICU Advisory Board. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15(8):762–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keele L, Keenan HT, Sheetz J, Bratton SL. Differences in characteristics of dying children who receive and do not receive palliative care. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):72–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson JE, Bassett R, Boss RD, et al. ; Improve Palliative Care in the Intensive Care Unit Project . Models for structuring a clinical initiative to enhance palliative care in the intensive care unit: a report from the IPAL-ICU Project (Improving Palliative Care in the ICU). Crit Care Med. 2010;38(9):1765–1772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aslakson RA, Curtis JR, Nelson JE. The changing role of palliative care in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(11):2418–2428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson JE, Curtis JR, Mulkerin C, et al. ; Improving Palliative Care in the ICU (IPAL-ICU) Project Advisory Board . Choosing and using screening criteria for palliative care consultation in the ICU: a report from the Improving Palliative Care in the ICU (IPAL-ICU) Advisory Board. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(10):2318–2327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Truog RD, Cist AF, Brackett SE, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: the Ethics Committee of the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(12):2332–2348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison WE, Gauvin F, Johnson E, Hwang J. Integrating palliative care into the ICU: from core competency to consultative expertise. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(8S suppl 2):S86–S91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 4th ed.Richmond, VA: National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care; 2018. Available at: https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/ncp. Accessed January 6, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feudtner C, Kang TI, Hexem KR, et al. Pediatric palliative care patients: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Pediatrics. 2011;127(6):1094–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morell E, Wolfe J, Scheurer M, et al. Patterns of care at end of life in children with advanced heart disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(8):745–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balkin EM, Kirkpatrick JN, Kaufman B, et al. Pediatric cardiology provider attitudes about palliative care: a multicenter survey study. Pediatr Cardiol. 2017;38(7):1324–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hui D, Bruera E. Models of integration of oncology and palliative care. Ann Palliat Med. 2015;4(3):89–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaye EC, Friebert S, Baker JN. Early integration of palliative care for children with high-risk cancer and their families. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(4):593–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaye EC, Snaman JM, Baker JN. Pediatric palliative oncology: bridging silos of care through an embedded model. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(24):2740–2744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Truog RD. Defining death-making sense of the case of Jahi McMath. JAMA. 2018;319(18):1859–1860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lantos JD. The tragic case of Charlie Gard. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(10):935–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laussen PC. Modes and causes of death in pediatric cardiac intensive care: digging deeper. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17(5):461–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilboa SM, Salemi JL, Nembhard WN, Fixler DE, Correa A. Mortality resulting from congenital heart disease among children and adults in the United States, 1999 to 2006. Circulation. 2010;122(22):2254–2263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spector LG, Menk JS, Knight JH, et al. Trends in long-term mortality after congenital heart surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(21):2434–2446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazwi ML, Henner N, Kirsch R. The role of palliative care in critical congenital heart disease. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(2):128–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Namachivayam P, Shann F, Shekerdemian L, et al. Three decades of pediatric intensive care: who was admitted, what happened in intensive care, and what happened afterward. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11(5):549–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ebrahim S, Singh S, Hutchison JS, et al. Adaptive behavior, functional outcomes, and quality of life outcomes of children requiring urgent ICU admission. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14(1):10–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones S, Rantell K, Stevens K, et al. ; United Kingdom Pediatric Intensive Care Outcome Study Group . Outcome at 6 months after admission for pediatric intensive care: a report of a national study of pediatric intensive care units in the United Kingdom. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):2101–2108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edwards JD, Houtrow AJ, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Chronic conditions among children admitted to U.S. pediatric intensive care units: their prevalence and impact on risk for mortality and prolonged length of stay*. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(7):2196–2203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newburger JW, Sleeper LA, Gaynor JW, et al. ; Pediatric Heart Network Investigators . Transplant-free survival and interventions at 6 years in the SVR trial. Circulation. 2018;137(21):2246–2253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Namachivayam SP, Alexander J, Slater A, et al. ; Paediatric Study Group and Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society . Five-year survival of children with chronic critical illness in Australia and New Zealand. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(9):1978–1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Namachivayam SP, d’Udekem Y, Millar J, Cheung MM, Butt W. Survival status and functional outcome of children who required prolonged intensive care after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152(4):1104.e3–1112.e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plunkett A, Parslow RC. Is it taking longer to die in paediatric intensive care in England and Wales? Arch Dis Child. 2016;101(9):798–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hancock HS, Pituch K, Uzark K, et al. A randomised trial of early palliative care for maternal stress in infants prenatally diagnosed with single-ventricle heart disease. Cardiol Young. 2018;28(4):561–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Donnell AE, Schaefer KG, Stevenson LW, et al. Social Worker-Aided Palliative Care Intervention in High-risk Patients With Heart Failure (SWAP-HF): a pilot randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(6):516–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.October T, Dryden-Palmer K, Copnell B, Meert KL. Caring for parents after the death of a child. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(8S suppl 2):S61–S68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burns JP, Sellers DE, Meyer EC, Lewis-Newby M, Truog RD. Epidemiology of death in the PICU at five U.S. teaching hospitals*. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(9):2101–2108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carter BS, Hubble C, Weise KL. Palliative medicine in neonatal and pediatric intensive care. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;15(3):759–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaies M, Ghanayem NS, Alten JA, et al. Variation in adjusted mortality for medical admissions to pediatric cardiac ICUs. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019;20(2):143–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michelson KN, Patel R, Haber-Barker N, Emanuel L, Frader J. End-of-life care decisions in the PICU: roles professionals play. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14(1):e34–e44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lewis-Newby M, Clark JD, Butt WW, Dryden-Palmer K, Parshuram CS, Truog RD. When a child dies in the PICU despite ongoing life support. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(8S suppl 2):S33–S40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marcus KL, Balkin EM, Al-Sayegh H, et al. Patterns and outcomes of care in children with advanced heart disease receiving palliative care consultation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(2):351–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Truog RD, Thiagarajan RR, Harrison CH. Ethical dilemmas with the use of ECMO as a bridge to transplantation. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(8):597–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Austin W, Kelecevic J, Goble E, Mekechuk J. An overview of moral distress and the paediatric intensive care team. Nurs Ethics. 2009;16(1):57–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Larson CP, Dryden-Palmer KD, Gibbons C, Parshuram CS. Moral distress in PICU and neonatal ICU practitioners: a cross-sectional evaluation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18(8):e318–e326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garros D, Austin W, Carnevale FA. Moral distress in pediatric intensive care. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(10):885–886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sauerland J, Marotta K, Peinemann MA, Berndt A, Robichaux C. Assessing and addressing moral distress and ethical climate, part 1. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2014;33(4):234–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sauerland J, Marotta K, Peinemann MA, Berndt A, Robichaux C. Assessing and addressing moral distress and ethical climate part II: neonatal and pediatric perspectives. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2015;34(1):33–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marron JM, Jones E, Wolfe J. Is there ever a role for the unilateral do not attempt resuscitation order in pediatric care? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(1):164–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Vos MA, Bos AP, Plötz FB, et al. Talking with parents about end-of-life decisions for their children. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/135/2/e465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Balkin EM, Wolfe J, Ziniel SI, et al. Physician and parent perceptions of prognosis and end-of-life experience in children with advanced heart disease. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(4):318–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blume ED, Balkin EM, Aiyagari R, et al. Parental perspectives on suffering and quality of life at end-of-life in children with advanced heart disease: an exploratory study*. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15(4):336–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moynihan KM, Jansen MA, Liaw SN, Alexander PMA, Truog RD. An ethical claim for providing medical recommendations in pediatric intensive care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2018;19(8):e433–e437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Welke KF. Interpreting congenital heart disease outcomes: what do available metrics really tell us? World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2010;1(2):194–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Welke KF, Karamlou T, Ungerleider RM, Diggs BS. Mortality rate is not a valid indicator of quality differences between pediatric cardiac surgical programs. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89(1):139–144; discussion 145–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sellers DE, Dawson R, Cohen-Bearak A, Solomond MZ, Truog RD. Measuring the quality of dying and death in the pediatric intensive care setting: the clinician PICU-QODD. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(1):66–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mun E, Nakatsuka C, Umbarger L, et al. Use of improving palliative care in the ICU (Intensive Care Unit) guidelines for a palliative care initiative in an ICU. Perm J. 2017;21:16-037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care–creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1173–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grunauer M, Mikesell C. A review of the integrated model of care: an opportunity to respond to extensive palliative care needs in pediatric intensive care units in under-resourced settings. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Marc-Aurele KL, English NK. Primary palliative care in neonatal intensive care. Semin Perinatol. 2017;41(2):133–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaye EC, Rubenstein J, Levine D, Baker JN, Dabbs D, Friebert SE. Pediatric palliative care in the community. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(4):316–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mosenthal AC, Weissman DE, Curtis JR, et al. Integrating palliative care in the surgical and trauma intensive care unit: a report from the Improving Palliative Care in the Intensive Care Unit (IPAL-ICU) Project Advisory Board and the Center to Advance Palliative Care. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(4):1199–1206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hilden J. It is time to let in pediatric palliative care. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(4):583–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kaye EC, Gushue CA, DeMarsh S, et al. Illness and end-of-life experiences of children with cancer who receive palliative care. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(4):e26895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Snaman JM, Kaye EC, Lu JJ, Sykes A, Baker JN. Palliative care involvement is associated with less intensive end-of-life care in adolescent and young adult oncology patients. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(5):509–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Snaman JM, Kaye EC, Baker JN, Wolfe J. Pediatric palliative oncology: the state of the science and art of caring for children with cancer. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2018;30(1):40–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vern-Gross TZ, Lam CG, Graff Z, et al. Patterns of end-of-life care in children with advanced solid tumor malignancies enrolled on a palliative care service. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50(3):305–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Prince-Paul M, Burant CJ, Saltzman JN, Teston LJ, Matthews CR. The effects of integrating an advanced practice palliative care nurse in a community oncology center: a pilot study. J Support Oncol. 2010;8(1):21–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Muir JC, Daly F, Davis MS, et al. Integrating palliative care into the outpatient, private practice oncology setting. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(1):126–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nelson JE, Cortez TB, Curtis JR, et al. ; The IPAL-ICU Project™ . Integrating palliative care in the ICU: the nurse in a leading role. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2011;13(2):89–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dahlin C, Coyne PJ, Cassel JB. The advanced practice registered nurses palliative care externship: a model for primary palliative care education. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(7):753–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hollander SA, Axelrod DM, Bernstein D, et al. Compassionate deactivation of ventricular assist devices in pediatric patients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35(5):564–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mascio CE. The use of ventricular assist device support in children: the state of the art. Artif Organs. 2015;39(1):14–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Meert KL, Keele L, Morrison W, et al. ; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network . End-of-Life practices among tertiary care PICUs in the United States: a multicenter study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16(7):e231–e238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schepers SA, Engelen VE, Haverman L, et al. Patient reported outcomes in pediatric oncology practice: suggestions for future usage by parents and pediatric oncologists. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(9):1707–1710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Clarke EB, Curtis JR, Luce JM, et al. ; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care End-Of-Life Peer Workgroup Members . Quality indicators for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(9):2255–2262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aslakson RA, Bridges JF. Assessing the impact of palliative care in the intensive care unit through the lens of patient-centered outcomes research. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2013;19(5):504–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Billings JA, Keeley A, Bauman J, et al. ; Massachusetts General Hospital Palliative Care Nurse Champions . Merging cultures: palliative care specialists in the medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(suppl 11):S388–S393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Friedel M, Aujoulat I, Dubois AC, Degryse JM. Instruments to measure outcomes in pediatric palliative care: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2019;143(1):e20182379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Downing J, Namisango E, Harding R. Outcome measurement in paediatric palliative care: lessons from the past and future developments. Ann Palliat Med. 2018;7(suppl 3):S151–S163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brock KE, Cohen HJ, Popat RA, Halamek LP. Reliability and validity of the pediatric palliative care questionnaire for measuring self-efficacy, knowledge, and adequacy of prior medical education among pediatric fellows. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(10):842–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brock KE, Cohen HJ, Sourkes BM, Good JJ, Halamek LP. Training pediatric fellows in palliative care: a pilot comparison of simulation training and didactic education. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(10):1074–1084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Soo S, Berta W, Baker GR. Role of champions in the implementation of patient safety practice change. Healthc Q. 2009;12(Spec No Patient):123–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Marcus KL, Henderson CM, Boss RD. Chronic critical illness in infants and children: a speculative synthesis on adapting ICU care to meet the needs of long-stay patients. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17(8):743–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]