Abstract

Acoustic neuroma (AN) usually manifests with asymmetric hearing loss, tinnitus, dizziness and sense of disequilibrium. About 10% of patients complain of atypical symptoms, which include facial numbness or pain and sudden onset of hearing loss. Patients with atypical symptoms also tend to have larger tumours due to the delay in investigation. We report a particularly interesting case of a patient presented to us with numbness over her right hemifacial region after a dental procedure without significant acoustic and vestibular symptoms. Physical examination and pure tone audiometry revealed no significant findings but further imaging revealed a cerebellopontine angle mass. The changing trends with easier access to further imaging indicate that the presentation of patients with AN are also changing. Atypical symptoms which are persistent should raise clinical suspicion of this pathology among clinicians.

Keywords: Ear, nose and throat; Ear, nose and throat/otolaryngology

Background

Acoustic neuromas (AN) or vestibular schwannomas are benign neoplasms arising from the Schwann cell sheath of the vestibular nerve. They are one of the most common (6%–10%) intracranial tumours1 with incidence ranging from 0.6 to 1.9 per 100 000 population.2 Studies have also shown an increase in detection of ANs due to better accessibility to MRI studies, audiometric and vestibular testing,2 which may implicate a change in patients’ initial clinical presentation to clincians.

Case presentation

A 54-year-old woman without medical illness was referred to us by the dental team due to 3 months history of persistent numbness over her right cheek and chin, which started after a tooth bridging procedure. She denied having toothache and her dentist could not find an association between her symptom and the dental treatment received. On further enquiries, she revealed having a 1 month history of mild right-sided tinnitus as well. Otherwise, there were no other otological symptoms.

Otoscopy and nasoendoscopy examination were normal. Examination of the cranial nerves revealed a reduced sensation of the skin over the distribution of the right maxillary and mandibular division of trigeminal nerve and a reduced corneal reflex on the right side. There were no other neurological deficits from physical examination.

Investigations

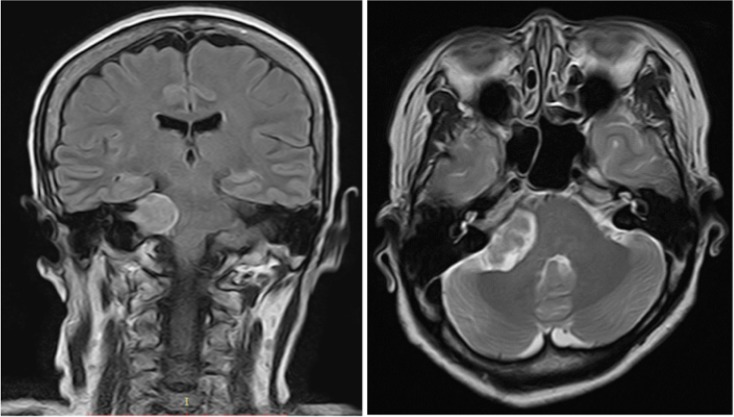

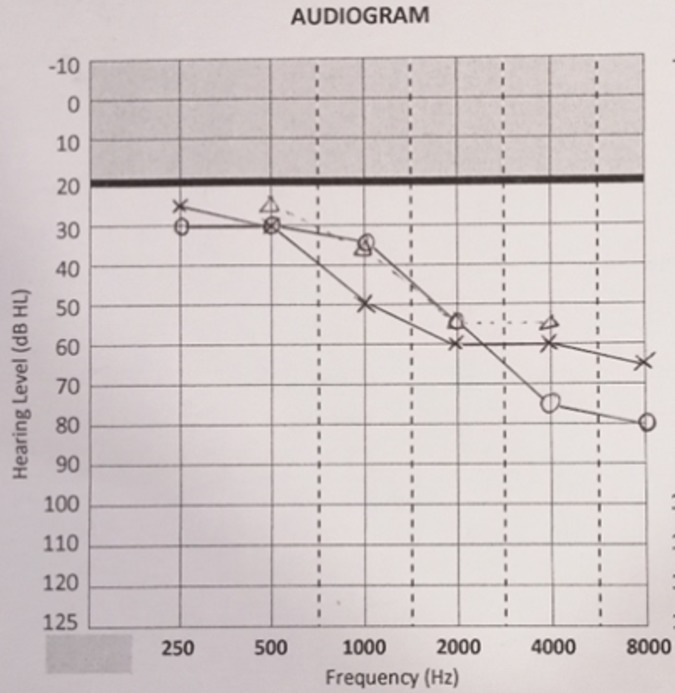

Pure tone audiometry showed a symmetrical mild to moderate sensorineural hearing loss with a down-sloping configuration (figure 1). A non-contrasted CT scan of the brain revealed a right cerebellopontine lesion at the internal auditory meatus, suggestive of AN. An MRI scan of the internal acoustic meatus showed an extracanalicular lesion measuring 3.4×2.2×2.4 cm and a smaller intracanalicular component measuring 1.0×0.6 cm. There was also compression of the lesion onto the adjacent brainstem and fourth ventricle with midline shift of 4 mm to the left (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Pure tone audiogram showed bilateral ear with almost symmetrical mild to moderate sensorineural hearing loss.

Figure 2.

MRI T2 sequence coronal and axial sections showed hyperintense right cerebellopontine angle mass with cystic component compressing onto brainstem and fourth ventricle with 4 mm midline shift to the left. The extracanalicular component measured 3.4×2.2×2.4 cm with small intracanalicular component measured 1.0×0.6 cm.

Outcome and follow-up

This patient decided to obtain treatment overseas in Australia where her daughter resides for better family support postoperatively. She underwent a translabyrinthine resection of the tumour and was discharged home well. Unfortunately, the facial numbness persisted after the operation with new onset of ipsilateral hearing loss. There were no other postoperative complications. No recurrences were identified from serial imagings postoperatively.

Discussion

AN is typically found within the internal acoustic meatus (intracanalicular) but can also project beyond the petrous part of the temporal bone (extracanalicular). Clinical manifestations of AN varies depending on the origin and extension of the tumour, where it may have mass effect on the surrounding structures of the cerebellopontine angle (CPA), such as the vestibular and cochlear portion of eight cranial nerve, facial nerve, trigeminal nerve, cerebellum and brainstem. Unilateral hearing loss, tinnitus and unsteadiness are the most common initial symptoms of AN. Late features of AN include headache, diplopia, nausea, vomiting, otalgia, facial numbness or weakness and dysgeusia. Facial paresthesia has also been reported as the initial presenting feature in about 4%–10% of patients with AN.3 Facial numbness or weakness are considered as late features when expansion of the tumour outside the internal auditory canal (IAC) near the trigeminal or facial nerve occur. Otalgia and dysgeusia are rarely encountered and are usually due to compression of the sensory and chorda tympani fibres of the facial nerve. Further growth of the tumour leads to symptoms of raised intracranial pressure such as headache, diplopia, nausea and vomiting. AN-related trigeminal neuropathy are thought to be caused by direct tumour pressure on the trigeminal nerve causing demyelination of somatosensory and pain fibres or less likely, from tumour pushing the trigeminal nerve and an artery into contact.4

Stangerup et al demonstrated in a large population-based prospective study that only a relatively small fraction of ANs (30% of extracanalicular tumours and 17% of intracanalicular tumours) grow over several years. Regardless of the tumour location or size, significant growth of the tumour only occurs within the first 5 years after diagnosis.5 The growth occurrence or rate was found to be unrelated to patients’ gender or age. With this improved understanding of the natural history of ANs, there has been a shift towards conservative management.

Moffat et al divided AN into three categories according to their morphologies and extensions from the IAC to the CPA, namely the dumbbell, cone and lollipop-shaped tumours. It has been suggested that when the tumour reaches a size of 20 mm, it extends out of the porus acusticus and touches the trigeminal nerve. Therefore, when tumours extend out of IAC into the CPA, there would be more involvement of the trigeminal nerve and less invovlement of hearing in patients.6 Involvement of the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve (VI) in particular, is a serious complication due to absence of corneal reflex, which exposes patients to dry eyes and subsequent keratitis especially if there is facial nerve paralysis of House-Brackmann grade IV and above. Karkas et al also found signfiant association between preoperative trigeminal hypoesthesia with findings of cerebellar peduncle compression on preoperative MRI.7

Generally, tumours measuring <1 cm are managed conservatively with yearly MRI for 5 years, followed by 2 yearly MRI for 4 years and one last MRI 5 years later, after which, no further follow-up imaging is required. This is because studies have found that AN grow at a mean growth rate of 1.8–1.9 mm/year, with most tumours only grow within the first 5 years.8 However, Patel et al found that hearing threshold and speech discrimination could progressively deteriorate even when the tumour size appears to be static.9

Radiosurgery has shown favourable patient outcomes in various studies, with improvement of their facial and trigeminal nerve function, preservation of hearing, reduced hospital stay and better quality of life.10 However, microsurgery was found to be significantly superior to radiosurgery in treating AN patients with trigeminal symptoms, especially when the tumour is >3 cm, where surgical removal of the tumour and concurrent decompression of the trigeminal nerve can be performed.11 Overall, management of AN is challenging as the surgeon must balance the risk of hearing loss, increased vestibular symptoms and facial weakness with treatment-related side effects. It has been found that 22% of patients experience one signficant postoperative complication, where the rate of facial paralysis and weakness after surgery was found to be 8% and 14%, respectively.12

Learning points.

About 10% of patients with acoustic neuroma (AN) complain of atypical symptoms, which include facial numbness or pain and sudden onset of hearing loss.

Facial paresthesia has been reported as the initial presenting feature in only about 4%–10% of patients with AN.

Patients with atypical symptoms tend to have larger tumours due to delay in investigation.

The changing trends with easier access to further imaging indicate that the presentation of patients with AN is also changing.

The increase in detection of ANs due to better accessibility to imaging studies may implicate a change in patients’ initial clinical presentation.

Clinicians should have raised awareness on this atypical presentation so that further investigation and management can be implemented promptly.

Footnotes

Contributors: CCL: data collection, literature review and writing up. YTL: literature review, writing up and editing. KM: literature review and data collection. EHCW: literature review and final editing.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hoffman S, Propp JM, McCarthy BJ. Temporal trends in incidence of primary brain tumors in the United States, 1985-19991. Neuro Oncol 2006;8:27–37. 10.1215/S1522851705000323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gal TJ, Shinn J, Huang B. Current epidemiology and management trends in acoustic neuroma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2010;142:677–81. 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.01.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berrettini S, Ravecca F, Russo F, et al. Some uncharacteristic clinical signs and symptoms of acoustic neuroma. J Otolaryngol 1997;26:97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jannetta PJ. Arterial compression of the trigeminal nerve at the pons in patients with trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg 2007;107:216–37. 10.3171/JNS-07/07/0216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stangerup S-E, Caye-Thomasen P, Tos M, et al. The natural history of vestibular schwannoma. Otol Neurotol 2006;27:547–52. 10.1097/01.mao.0000217356.73463.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moffat DA, Golledge J, Baguley DM, et al. Clinical correlates of acoustic neuroma morphology. J Laryngol Otol 1993;107:290–4. 10.1017/S0022215100122856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karkas A, Lamblin E, Meyer M, et al. Trigeminal nerve deficit in large and compressive acoustic neuromas and its correlation with MRI findings. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;151:675–80. 10.1177/0194599814545440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selesnick SH, Johnson G. Radiologic surveillance of acoustic neuromas. Am J Otol 1998;19:846–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel NB, Nieman CL, Redleaf M. Hearing in static unilateral vestibular schwannoma declines more than in the contralateral ear. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2015;124:490–4. 10.1177/0003489414566181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollock BE, Driscoll CLW, Foote RL, et al. Patient outcomes after vestibular schwannoma management: a prospective comparison of microsurgical resection and stereotactic radiosurgery. Neurosurgery 2006;59:77–85. 10.1227/01.NEU.0000219217.14930.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang H, Kano H, Awan NR, et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery for larger-volume vestibular schwannomas: clinical article. J Neurosurg 2013;119:801–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sughrue ME, Yang I, Aranda D, et al. Beyond audiofacial morbidity after vestibular schwannoma surgery. J Neurosurg 2011;114:367–74. 10.3171/2009.10.JNS091203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]