Abstract

There are now close to 17 million cancer survivors in the United States, and this number is expected to continue to grow. One decade ago the Institute of Medicine report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, outlined 10 recommendations aiming to provide coordinated, comprehensive care for cancer survivors. Although there has been noteworthy progress made since the release of the report, gaps remain in research, clinical practice, and policy. Specifically, the recommendation calling for the development of quality measures in cancer survivorship care has yet to be fulfilled. In this commentary, we describe the development of a comprehensive, evidence-based cancer survivorship care quality framework and propose the next steps to systematically apply it in clinical settings, research, and policy.

A decade ago, the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition, outlined 10 recommendations aiming to provide coordinated, comprehensive care for cancer survivors (1). Although progress has been made, gaps remain (2,3). One recommendation stated that “Quality of survivorship care measures should be developed through public/private partnerships and quality assurance programs implemented by health systems to monitor and improve the care that all survivors receive” (1). In attempts to fulfill this recommendation, several initiatives have been launched including the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer standards for survivorship care that were required for cancer program accreditation (4), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (5), and the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation Center Oncology Care Model (6). Although these efforts are likely to improve care for cancer survivors, their scope has been limited with respect to addressing the breadth of cancer survivorship care. Further limiting progress in this area is the lack of systematically developed, tested, and implemented models for delivering and evaluating cancer survivorship care (1,7–13). In this commentary, we describe the development of a comprehensive, evidence-based quality of cancer survivorship care framework that is applicable for diverse populations of adult cancer survivors (including those who have completed active treatment, may be on adjuvant hormonal therapy, or remain on chronic cancer treatment) and propose the next steps to systematically apply this framework in clinical settings, research, and policy.

Landscape Review

Review Process and Sources

Using a scoping methodology (14), we aimed to identify the domains of cancer survivorship care and their respective constructs or indicators. Our iterative review included numerous sources and was intended to capture the evidence as well as the perspectives of multiple stakeholders. First, we reviewed guidelines focusing on cancer survivorship care, including those published by the American Cancer Society (ACS), ASCO, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, as well as survivorship-focused guidelines from Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia (Box 1). Following a detailed review of these guidelines, we conducted a supplemental review of selected disease-based guidelines for additional domains and/or indicators that had not been captured. Second, we reviewed titles and abstracts of National Cancer Institute (NCI) grants funded during fiscal year 2016, as part of a larger portfolio analysis (15). Of the identified 165 grants, 69 were excluded because they focused solely on measure development, biomarker mechanisms, caregivers, or enrolled survivors less than 6 months after diagnosis or who were children. We followed a similar process to review the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute-funded (2013–2017) grants, including 10 of 13 identified survivorship grants. Third, we identified the most current cancer control plans using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program database (16) and internet searches, supplemented by direct contact with representatives from the states’ programs. For each of the plans, we conducted a systematic review of the survivorship-related goals, objectives, and indicators. Fourth, we reviewed quality measures endorsed or supported by health-care organizations in the United States and Europe (Box 1). Fifth, to incorporate the survivor perspective, we reviewed selected ACS Survivor Network message boards for additional thematic areas in cancer survivorship care that were not uncovered through the other sources (17). Throughout the process, we reviewed published literature, focusing on reviews, commentaries and editorials, and position papers addressing cancer survivorship care quality (1, 7–10, 12, 13, 18–34). We also reviewed seminal papers in quality of care, not specifically in the field of oncology (35–37). Through the iterative process, we outlined and updated the domains and their respective indicators. We developed and updated a visual graphic that was meant to summarize the framework.

Box 1.

Guidelines included in review

- American Cancer Society

- American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline

- American Cancer Society Colorectal Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline

- American Cancer Society Head and Neck Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline

- American Cancer Society Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline

- American Cancer Society Nutrition and Physical Activity Guidelines for Cancer Survivors

- American Society of Clinical Oncology

- Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline: American Society of Clinical Oncology Practice Guideline Endorsement

- Head and Neck Cancer Survivorship Guideline: American Society of Clinical Oncology Endorsement of the American Cancer Society Guideline

- Follow-Up Care, Surveillance Protocol, and Secondary Prevention Measures for Survivors of Colorectal Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Endorsement

- Screening, Assessment, and Management of Fatigue in Adult Survivors of Cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation

- Screening, Assessment, and Care of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Adults With Cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology Guideline Adaptation

- Prevention and Management of Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy in Survivors of Adult Cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Summary

- Fertility Preservation in Patients With Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update

- Prevention and Monitoring of Cardiac Dysfunction in Survivors of Adult Cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline

- American Society of Clinical Oncology Endorsement of Cancer Care Ontario - Interventions to Address Sexual Problems in People with Cancer

- Patient-Clinician Communication: American Society of Clinical Oncology Consensus Guideline

- Cancer Care Ontario

- Follow-up and Surveillance of Curatively Treated Lung Cancer Patients

- Follow-up for Cervical Cancer

- Follow-up of Patients Who Are Clinically Disease-free After Primary Treatment for Fallopian Tube, Primary Peritoneal, and Epithelial Ovarian Cancer

- Follow-up of Patients with Cutaneous Melanoma Who Were Treated with Curative Intent

- Person-Centred Care Guideline

Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer (Version 4.0)

National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology

Survivorship, Version 2.2017

Recommended screening and preventive practices for long-term survivors after hematopoietic cell transplantation; Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR), American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (ASBMT), European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT), Asia-Pacific Blood and Marrow Transplantation Group (APBMT), Bone Marrow Transplant Society of Australia and New Zealand (BMTSANZ), East Mediterranean Blood and Marrow Transplantation Group (EMBMT), and Sociedade Brasileira de Transplante de Medula Ossea (SBTMO)

Supplemental Guidelines

- Cancer Australia

- Recommendations for use of bisphosphonates in early breast cancer

- Recommendations for follow up of women with early breast cancer

- Follow up of women with epithelial ovarian cancer

- Management of menopausal symptoms in women with a history of breast cancer

- Clinical guidance for responding to suffering in adults with cancer

- Recommendation for the identification and management of FOR (fear of recurrence) in adult cancer survivors

- Cancer Care Ontario

- Position Statement on Guidelines for Breast Cancer Well Follow-Up Care

- Follow-up Care and Psychosocial Needs of Survivors of Prostate Follow-up

- Care for Survivors of Lymphoma Who Have Received Curative-Intent Treatment

- Follow-up Care, Surveillance Protocol, and Secondary Prevention Measures for Survivors of Colorectal Cancer

- Models of Care for Cancer Survivorship

Selected European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Guidelines

Selected National Comprehensive Cancer Center (NCCN) Guidelines

Selected National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines

Key Expert Interviews

Following the development of the draft framework, one author conducted telephone interviews with experts (n = 20) representing researchers, clinicians (primary care, medical oncology, radiation oncology, surgical oncology, and psychology), policy makers, payers, advocacy groups, and patients. The list of experts was identified based on contribution to the fields of cancer survivorship and/or cancer care quality and was vetted by the study team to ensure representation of diverse perspectives. Experts were invited by email to participate in a telephone call or an in-person interview, which lasted 30 minutes. Institutional Review Board approval for this portion of the project was obtained from the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. The interviews were semistructured and included discussion of the definition of quality in cancer survivorship care, domains of cancer survivorship quality, draft framework, and gaps in the area of cancer survivorship quality. Field notes and recordings were used to summarize the conversations; formal qualitative analyses were not performed. The discussions led to several revisions of the framework to achieve the final version that included the domains, their relationships to one another, contextual factors influencing cancer survivorship care quality, and outcomes. The framework was subsequently presented in informal meetings and formal venues (eg, national professional conferences), and additional revisions were made based on the feedback.

Quality of Cancer Survivorship Care Framework

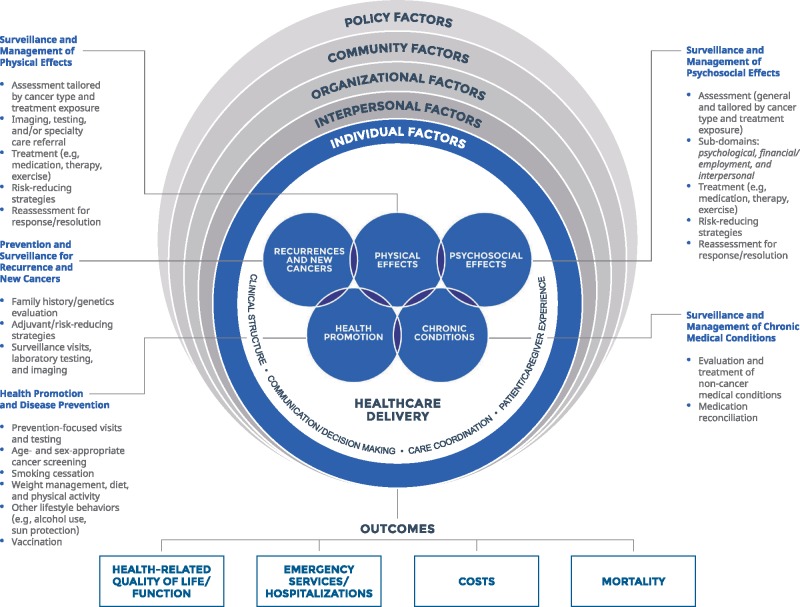

The framework for cancer survivorship care quality is presented in Figure 1. Overall, we identified five domains of cancer survivorship quality pertaining to cancer-related and general care needs including prevention and surveillance for recurrences and new cancers; surveillance and management of physical effects; surveillance and management of psychosocial effects; surveillance and management of chronic medical conditions; and health promotion and disease prevention. Although represented distinctly, each of the domains are interrelated and often codependent on one another. Relevant indicators for each domain are described below and listed in detail in Box 2. Further, we identified contextual domains of the health-care delivery system that influence cancer survivorship care quality, including clinical structure, communication and decision making, care coordination, and patient and/or caregiver experience (Box 2).

Figure 1.

Cancer survivorship care quality framework.

Box 1.

Cancer survivorship care quality domains and proposed indicators

Domains of Cancer Survivorship Care Pertaining to Cancer and its Treatment

Prevention and Surveillance for Recurrence and New Cancers

Assessment of risk predisposition including family history

Referral and receipt of recommended genetics evaluation

Recommendation for adjuvant and/or risk-reducing strategies

Assessment of adherence with recommended adjuvant and/or risk-reducing strategies

Clinical surveillance visits recommended and completed per guidelines

Laboratory surveillance testing recommended and completed per guidelines

Imaging surveillance recommended and completed per guidelines

Surveillance and Management of Physical Effects

- Assessment of symptoms and/or conditions via history, physical examination, and/or standardized instruments, tailored by cancer type and treatment exposure. May include the following:

- Visual (eg, cataracts, visual impairment, dry eyes)

- Hearing (eg, ototoxicity, tinnitus, hearing loss)

- Oral/dental (eg, loss of teeth, dry mouth, trismus)

- Ear/nose/throat (eg, dysphagia, sinusitis)

- Endocrine (eg, central endocrinopathies, hypothyroidism, hypogonadism, growth hormone deficiency, osteopenia, osteoporosis)

- Cardiac (eg, dyspnea, coronary artery disease, valvular disease, congestive heart failure)

- Pulmonary (eg, fibrosis, restrictive lung disease, shortness of breath, oxygen dependence, cough)

- Gastrointestinal (eg, diarrhea, proctitis, gastroesophageal reflux, bowel obstruction, bloating, eructation, hernia, small bowel obstruction)

- Hepatic (eg, hepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, focal nodular hyperplasia)

- Genitourinary (eg, urinary toxicity, urinary incontinence, hematuria)

- Immunological (eg, asplenia, immunodeficiency, graft versus host disease)

- Male genital (eg, anorgasmia, azoospermia, dry ejaculate, penile shortening/curvature, retrograde ejaculation)

- Gynecological (eg, vaginal dryness, pain with intercourse, uterine insufficiency, vaginal stenosis, pelvic floor dysfunction)

- Musculoskeletal (eg, scoliosis, pain, post-mastectomy pain, post-thoracotomy pain, bone fractures)

- Dermatological (eg, dry skin, graft versus host disease manifestations, skin color changes, skin texture changes, loss of hair)

- Neurological (eg, neurotoxicity, peripheral neuropathy, imbalance, spasticity)

- Neurocognitive (eg, memory changes, behavioral changes, concentration)

- Vasomotor (eg, hot flashes, irritability)

- Vascular (eg, carotid stenosis, aneurysms, cerebrovascular accident, moyamoya)

- Body composition (eg, sarcopenia, cachexia)

- Frailty

- Reduced exercise tolerance

- Overall burden of physical symptoms

Referral and receipt of recommended evaluation including, as indicated, laboratory, imaging, and/or specialty care

Recommendation and receipt of appropriate treatment, such as medication, therapy, and/or exercise

Recommendation for risk-reducing strategies (eg, weight loss, exercise, pharmacological treatment)

Assessment of adherence to recommended treatment and/or risk-reducing strategies

Reassessment of symptoms and/or conditions at defined intervals and/or treatment phase

Surveillance and Management of Psychosocial Effects

- Assessment of symptoms and/or conditions using history or validated instruments, general and tailored by cancer type and/or treatment exposure. May include the following:

- Psychological

- Fatigue

- Stress

- Posttraumatic stress

- Posttraumatic growth

- Distress

- Anxiety

- Fear of recurrences

- Sleep disturbance

- Coping

- Worry

- Illness intrusiveness

- Cognitive changes

- Educational problems

- Social withdrawal

- Financial and/or employment

- Financial toxicity

- Underemployment, unemployment, return to work

- Work productivity

- School productivity

- Insurance status

- Interpersonal

- Sexuality and/or intimacy

- Fertility

- Family and/or caregiver relationships

- Recommended evaluation provided (eg, laboratory testing, imaging, referral to specialty care)

- Treatment provided (eg, medication, therapy, exercise)

- Assessment of adherence to treatment completed

- Reassessment of symptoms and/or conditions at defined intervals and/or treatment phase

Domains of Cancer Survivorship Care Pertaining to General Health Care

Surveillance and Management of Chronic Medical Conditions

Evaluation and treatment of noncancer medical conditions (eg, hypertension, diabetes, depression) using disease-specific indicators

Medication reconciliation

Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

Prevention-focused visits and testing (eg, screening for diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia)

Age- and gender-appropriate cancer screening (eg, Pap smear, mammogram, colonoscopy), recommendation, referral, and receipt of screening

Assessment of lifestyle behaviors, referral, and treatment (eg, smoking, alcohol, sun protection)

Assessment of weight management (eg, obesity, physical activity, diet), referral, and treatment

Vaccination advice and assessment of vaccination rates (eg, influenza, pneumonia, meningococcal, shingles, particularly among those who may be chronically immunocompromised)

Screening for exposure to infectious exposures (eg, HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C)

Contextual Domains of Health-Care Delivery

Clinical Structure

Type of health-care delivery environment (eg, primary care office, oncology office, survivorship clinic, academic medical center/community-based hospital, urban/rural)

Status of cancer survivorship providers’ education and/or training

Availability of needed specialty care (eg, cardiology, nephrology, endocrinology)

Availability of needed health-care professionals (eg, psychology, nutrition, social work, physical therapy, sexual health)

Access to care enabled (eg, availability of appointments, financial counseling, navigators)

Availability and functionality of health information systems (eg, electronic medical records, tele-health)

Opportunities for research participation offered

Communication/Decision Making

Information/education provided and understanding assessed while taking into account health literacy (eg, survivorship care plan may serve as a tool)

Assessment of self-management skills and support and/or advice provided

Advance care planning discussion and/or documentation

Discussion of sensitive topics (eg, sexual activity, continence, end-of-life care)

Cancer care team involves family members or friends in discussions

Involvement in shared decision making (eg, assessment of risk perception, values, decision support)

Respectful communication with patient

Care consistent with patients’ goals of care

Care Coordination

Discussion with patient about care planning, documentation, and sharing with patient and care team (eg, survivorship care plan as tool)

Evidence of communication between oncology specialists and primary care providers

Evidence of communication between other health-care professionals, oncology team, and primary care providers

Providers aware of important information about patient’s medical history and/or ongoing care

Patient and cancer care team office talked about all prescription medications the patient was taking

Patient/Caregiver Experience

Satisfaction with provider and/or health care delivery setting

Perceived timely access to care

Perceived access to services

Timely follow-up with patient/caregiver to give test results

Domains of Cancer Survivorship Care Pertaining to Cancer and Its Treatment

Prevention and Surveillance for Recurrences and New Cancers

Cancer survivors are at risk for recurrence of the primary cancer and the development of new cancers that may be due to genetic predisposition, lifestyle habits, and/or treatment exposures (38). First, assessment of such risk factors is needed. Genetic predisposition may be measured by the completion of a detailed family history, referral for genetic counseling, and receipt of appropriate testing and follow-up. Lifestyle behaviors may be assessed using a detailed social history, followed by counseling and/or referral to appropriate providers and reassessment. Likewise, treatment exposures (eg, radiation fields, dose, and time since; chemotherapy types/dose/duration/time since) should be collected. Recommendation for and receipt of appropriate surveillance using evidence-based modalities should be assessed. Second, completion of evidence-based surveillance strategies for recurrence of the primary cancer should be assessed and may include history, physical examination, laboratory, and/or imaging. Provision of nonevidence-based and/or guideline-recommended strategies should also be addressed. Lastly, assessment of completion of risk-modifying strategies such as chemoprevention (eg, adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy), if applicable, is warranted.

Surveillance and Management of Physical Effects

Cancer survivors are at risk for a variety of physical effects whose presence, number, and severity may be related to disease, treatment exposures, and other factors. A list of proposed indicators, which includes symptoms (eg, dry mouth) and conditions (eg, cardiomyopathy), is provided in Box 2. An assessment (using history, physical examination, and/or validated instruments) for the existence and severity of physical effects using a systematic approach may be global or tailored by disease and treatment exposure. Identified symptoms and/or conditions should then guide an evidence-based and/or guideline-recommended treatment. Measurement of risk-reducing strategies for physical effects is also indicated, for example, blood pressure control aiming to reduce anthracycline and/or chest radiation-related cardiotoxicity and/or early intervention for cardiac disease among such individuals. The evaluation of quality should aim for a “closed loop” approach, including assessment, referral, and reassessment of symptoms and/or conditions. Provision of nonevidence-based and/or guideline recommended strategies should be assessed because this may lead to unnecessary utilization of services and related consequences.

Surveillance and Management of Psychosocial Effects

As with physical symptoms, survivors’ psychosocial burden may vary, and thus the type and extent of systematic surveillance for symptoms may be guided by cancer type, treatment exposures, and other factors. Indicators in this category include psychological effects, such as newly diagnosed depression, anxiety, and fear of recurrences; financial indicators including perceived hardship, loss of work productivity, return to school, and changes in insurance status; and interpersonal issues such as sexuality and/or intimacy, fertility, and family and/or caregiver relationships. A list of indicators is presented in Box 2. Once symptoms are identified, provision of evidence-based and/or guideline-recommended care, referral, and completion of treatment should be assessed. Further, referral for risk-reducing strategies such as early referral to psycho-educational programs and counseling should be measured. As mentioned above, reassessment of symptoms and/or conditions should be measured and provision of nonevidence-based and/or guideline-recommended strategies should also be assessed.

Domains of Cancer Survivorship Care Pertaining to General Health Care

Surveillance and Management of Chronic Medical Conditions

Given the high prevalence of chronic physical and mental health conditions among cancer survivors both prior to and subsequent to treatment (39), and the contribution of such conditions to physical and psychosocial effects as well as mortality (40–44), cancer survivorship care should take into account the indicators in this domain. This includes an assessment and management for preexistent or newly diagnosed chronic medical conditions (eg, hypertension, diabetes, depression) using disease-based indicators, medication reconciliation, and assessment of adherence with recommended therapies.

Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

Population data have demonstrated that cancer survivors are often obese and less active than those without cancer, and survivors often continue to smoke (45–47). These lifestyle behaviors are associated with an increased risk of new, additional cancers (48), whereas engaging in physical activity after cancer may reduce mortality (49, 50). Assessment of lifestyle behaviors and provision of appropriate counseling is vital for achieving cancer survivorship care quality (Box 2). Other indicators include age- and sex-appropriate cancer screening, vaccination, screening for chronic medical conditions, and infectious exposures.

Contextual Domains of Health-Care Delivery

Contextual domains are not unique to cancer survivorship care, although indicators may be specifically tailored to this population (Box 2). For example, Clinical Structure includes indicators such as type of health-care setting (eg, primary care, oncology, or survivorship clinic; academic medical center or community-based hospital; urban or rural); type and availability of providers offering care; whether access to care is adequately enabled (eg, availability of appointments, financial counseling, navigators, health information technology); and opportunities for research participation, if available. Communication and Decision Making indicators include the provision and understanding of information; assessment of self-management skills; discussion of sensitive topics such as sexual activity, continence, and advance-care planning; extent and preferences of patient involvement in shared decision making; and communication that is both patient-centered and respectful. Whether a survivorship care plan was provided to the patient may be assessed. Care Coordination indicators include documentation and sharing of a survivorship care plan and follow-up with appropriate providers, the adequacy of care coordination (eg, assessment that communication took place, that providers are aware of the important information about the patient’s medical history and/or ongoing care, and that prescribed medications are taken into consideration by all providers). Lastly, Patient/Caregiver Experience measures include an evaluation of perceived access and timeliness of care and needed services, timely follow-up on testing, satisfaction with care, and care that is consistent with expectations and needs regardless of provider or setting.

Individual and Socio-Ecological Factors

As demonstrated by the framework, Individual Factors are central to the delivery of cancer survivorship care and should drive which and to what extent domains are addressed. These factors include sociodemographics (eg, age, gender, education, occupation, income), health literacy, patient activation (eg, knowledge, self-management skills, confidence) to manage own health, cancer type, stage, treatment, and time since treatment or phase of survivorship, among others. The framework also takes into account the previously described socio-ecological factors (19) affecting cancer survivorship care at all levels including interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy.

Health-Care Outcomes

Outcomes of cancer survivorship care quality that may be measured are not distinct to this population and include health-related quality of life including physical, mental, emotional, and social functioning; health-care utilization, specifically emergency care, hospitalizations, and critical care use); costs of care, including those to the patient and health-care system; and mortality (all-cause and cancer specific).

Implications for Clinical Care, Research, and Policy

Through a comprehensive, iterative process, we developed a framework that may be used to systematically deliver and evaluate the quality of cancer survivorship care across the population of adult cancer survivors. Prior literature offered approaches to measuring quality in cancer survivorship care and outlined opportunities for research (1, 7–11); however, these were mainly based on narrative literature reviews and/or individual authors’ perspectives. Our framework was derived using a multimethods analysis including US and international professional guidelines, funded grants, comprehensive state cancer plans, patient voices, and published literature. The model was validated through semistructured stakeholder interviews followed by presentations at a number of venues. As such, our framework is comprehensive, based on existing evidence and inclusive of wide-ranging perspectives. Our framework serves as a road map for future efforts aiming to systematically measure and improve cancer survivorship care quality in clinical care, research, and policy. We propose several strategies for such steps in the sections below.

Clinical Care

Our review revealed a number of barriers in the provision and evaluation of cancer survivorship care quality within clinical health-care systems, including what, how, and when to measure quality, as well as how to balance measurement while avoiding overburdening the patients, providers, and systems. Our model provides an overview of the domains and indicators in cancer survivorship that matter to patients and providers. We propose the following steps in applying the framework to clinical settings. First, to design effective, evidence-based clinical survivorship care, providers, practices, and health-care systems need to understand their patient populations. This requires accurately and systematically identifying those with a prior history of cancer, their characteristics, diagnoses, treatments, comorbid medical conditions, and other factors needed to inform where specific efforts will be most beneficial. If not intuitive from the medical record, collection of such information and placement in a recognizable field in the record is critical (51). Second, based on the population needs, implementation of the full framework, or parts thereof, may be desired. For example, elderly men with early stage prostate cancer may derive the most benefit from an emphasis on management of chronic medical conditions, whereas adult survivors of childhood cancer may have broad needs that must include attention to most of the domains presented. Decisions must also be made on how and when specific domains of care are offered. There has been great interest in the models of cancer survivorship care and where and who should deliver this care (25, 52, 53), yet few have measured interventions in this regard (10, 53). Our framework provides an overview of processes that should be offered to deliver quality survivorship care, but who and where these are provided may be tailored. Comprehensive cancer centers may be able to offer more extensive resources and services to their survivors than smaller, independent oncology providers. However, smaller programs may have fewer barriers in assessing and meeting those needs. Regardless of setting, decisions on which domains are being addressed and how they are best delivered should be made systematically and should not be based purely on the availability of resources. Patient- and other socio-ecological-level needs assessments can help prioritize, guide, and evaluate the delivery of existing services, or they may be developed or offered through local partnerships (eg, psychological support may be provided via a community organization, exercise counseling may be provided by trained staff at a local gym, insomnia intervention may be provided using an online program).

Psychosocial and physical effects among cancer survivors are common and may lead to considerable detriments in quality of life. As we found on the ACS Cancer Survivors Network, patients readily share their symptoms, suggesting a need for support and guidance from others. It is important that patient-reported outcomes and unmet needs are routinely collected in clinical settings. There are a number of existing validated measures that may be used (54–56). Crosscutting screening instruments that are brief and easy to administer and interpret may be preferable, with expanded supplemental tools geared toward specific patient populations, cancers, and treatment exposures. For example, women treated for gynecological malignancy require a more detailed inquiry into sexual function, pelvic floor dysfunction, and interpersonal issues, whereas a more cursory evaluation may be indicated for a survivor of surgically resected localized melanoma. To avoid provider burden (57), tools collecting patient-reported outcomes may be completed by patients prior to clinical appointments or administered by support staff, and they may be assessed using e-health technologies (58).

Electronic medical records and other innovative health information technologies should be structured to facilitate the delivery of quality cancer survivorship care. Tools may be developed that can help identify patients at risk, provide decision support, monitor patient-reported outcomes, track the provision of services, assess response to interventions, and enhance communication and care coordination. Feedback may be provided to clinicians, with opportunities for education and training. Whether through local initiatives or through nationwide efforts such as ASCO’s CancerLinQ , measurement of survivorship-focused outcomes will help improve quality of care through the rapid learning system where real-time clinical data are collected, analyzed, and used to improve clinical care and health-care outcomes (59). Because reimbursement for lengthy visits and development of a survivorship care plan may be a barrier to the provision of quality survivorship care (60), training of billing and documentation (with possible implementation of bundled payment for cancer survivorship care) will generate additional reimbursement. We posit, however, that institutions should consider survivorship care in their cancer care mission and offer financial resources to enhance the care of their patients.

Research

Mention of existing gaps in cancer survivorship research was notable in our review of clinical guidelines and other publications. We suggest that our framework be used to identify these gaps and advance research accordingly. First, we propose a systematic assessment of existing evidence across the domains, indicators, and outcome measures. For areas where sufficient evidence exists [eg, benefits of smoking cessation and exercise interventions among survivors (61, 62)], attention should be placed on dissemination and scalability of proven interventions to diverse groups of survivors. Where evidence suggests harm [eg, use of surveillance tumor markers for women with early breast cancer (63)], efforts should be made to de-implement (64). Where evidence gaps exist, such as surveillance for cardiotoxicity (65) or management of neurotoxicity (66), we advise an assessment of the contributing reasons for these gaps and the design of interventions to address them. Our review of NCI grants revealed that the most commonly proposed measures were of physical and psychosocial effects and health promotion, whereas measures of chronic medical conditions, care coordination, and health-care delivery structure were rare. Outcomes such as costs, mortality, and adverse health-care utilization were less frequently measured than health-related quality of life. Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute grants mainly focused on surveillance for recurrences. We propose the following steps to advance research on cancer survivorship care quality: the training and support of investigators from less represented cancer types and/or disciplines and health-care providers; targeted funding announcements addressing scientific gaps with designated and informed review panels; evaluation, prioritization, and consensus-building for existing measures (eg, compiled by NCI) (67); development of new patient-reported measures and those that may be ascertained using automated data; use of modeling for rarer cancers and/or collection of survivorship measures from treatment-based clinical trials of such cancers; and promotion of well-designed dissemination and implementation research for the sustained use of evidence-based strategies in clinical settings.

Policy

Our review revealed policy barriers including the need for professional guidelines, training, reimbursement, and health insurance coverage. We found inconsistent approaches to post-treatment care in cancer guidelines. Whereas those dedicated to cancer survivorship (eg, ACS disease-based guidelines and selected ASCO guidelines presented in Box 1) covered most of the proposed domains, others focused mainly on symptom management (eg, selected ASCO guidelines) and most on cancer surveillance alone. Among the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, we found inconsistent focus on post-treatment effects that varied by cancer type (although not necessarily based on risk of such effects by treatment exposure). Although evidence is lacking for many diseases, a standardized approach to incorporate all domains of cancer survivorship care should be embedded in every cancer guideline, and lack of evidence for recommendations should be emphasized. Research strategies should be developed to fill in the gaps identified, as described above. For example, a recent “systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses” targeted the domains outlined in the ACS/ASCO Prostate Cancer Survivorship guideline and found that exercise and psychosocial interventions were effective but that interventions addressing cancer surveillance and care coordination were lacking (68).

In our review of national quality organizations’ efforts, we found little focus on measures in cancer survivorship care quality. Although prior efforts have been made to introduce measures of cancer surveillance after breast, colon, and prostate cancer for National Quality Forum endorsement, such measures (as well as those pertaining to the physical effects and psychosocial effects) are not currently included. Measures addressing general health care in health promotion and chronic disease management and pertaining to shared decision making and patient satisfaction are included (69) and may be implemented in clinical settings. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality indicators in cancer survivorship are lacking (70). The ASCO Quality Oncology Practice Initiative 2018 metrics focus mainly on treatment, and only a few measures address those in the survivorship phase of care as outlined in our framework (eg, provision of a survivorship care plan, radiation-treatment summary, advance-care planning, documentation of medications, tobacco cessation, and blood pressure measurement) (5). Much of the focus of the Commission on Cancer and the Oncology Care Model has been around the survivorship care plan, which our framework demonstrates is simply one measure of communication and coordination. The International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement, a nonprofit organization aiming to develop quality measures for global implementation, addresses many of the patient-reported outcomes, but no other indicators were identified (71–74). Our framework serves as a road map for future efforts to systematically identify, develop, and prioritize measures that include the processes, patient-reported, and other health-care quality outcomes. Such “high-value, high-impact, evidence-based measures that promote better patient outcomes” and “reduce the burden of measuring” may be used for “quality improvement, transparency, and payment” (75).

An additional policy-level approach to enhance cancer survivorship care that is facilitated by our framework should focus on the state and national levels. Our review found that cancer state control plans aimed to raise awareness of cancer survivorship, reduce rates of smoking and obesity, promote the delivery of cancer survivorship care plans, and address models of coordinated care, but they were often lacking in clearly measurable objectives. A standardized approach to measuring quality of cancer survivorship care as guided by our framework not only may be effective in improving quality in specific settings but also may be used to assess and compare quality by neighborhood, state, and region and to evaluate the effects of variable health-care delivery practices and insurance plans. Disparities may be addressed by targeting interventions at lower performing areas and by driving policy and advocacy efforts that are supported by evidence.

Summary

There are now an estimated 16.9 million cancer survivors in the United States who are getting older, have chronic medical conditions, and are cared for across health-care settings (76). Although progress has been made, it is important that we fulfill a key recommendation made by the National Academy of Medicine over a decade ago and focus our attention on improving the quality of comprehensive cancer survivorship care. We propose that our framework serve as a road map toward this goal and that it is systematically applied in clinical settings through implementation of effective, evidence-based interventions, in research through expansion of initiatives to address gaps in knowledge, and in policy through the development of recommendations and assessments that promote cancer survivorship quality improvement.

Notes

Affiliations of authors: Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA (LN); Healthcare Delivery Research Program, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD (MAM, PBJ, AMG); UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center and School of Nursing, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, NC (DKM); Office of Cancer Survivorship, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD (DKM); Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA (LNS).

This article was prepared as part of some of the authors’ (MAM, PBJ, DKM, AMG) official duties as employees of the US Federal Government. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the National Cancer Institute.

This work was completed while Dr Nekhlyudov was a National Cancer Institute/AcademyHealth Healthcare Delivery Research Visiting Scholar. This program offers mid-career scientists an opportunity to develop new research directions and address high-priority needs for the field of health services research and health-care delivery.

Preliminary findings were presented at the AcademyHealth Annual Meeting in June 2018 and at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Quality Care Symposium in September 2018.

Table 1.

Organizations with endorsed quality measures, indicators, and/or initiatives included in review

References

- 1. Institute of Medicine. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nekhlyudov L, Ganz P, Arora NK, et al. Going beyond being lost in transition: a decade of progress in cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2017;3518:1978–1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Long-Term Survivorship Care after Cancer Treatment: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. American College of Surgeons. Cancer Program Standards (2016 Edition). https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/standards. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 5. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Quality oncology practice initiative.https://practice.asco.org/quality-improvement/quality-programs/quality-oncology-practice-initiative. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 6. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Oncology care model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/oncology-care/. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 7. Parry C, Kent E, Forsythe L, et al. Can’t see the forest for the care plan: a call to revisit the context of care planning. J Clin Oncol. 2013;3121:2651–2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grunfeld E, Earle C, Stovall E.. A framework for cancer survivorship research and translation to policy. Cancer. Epidemiology Biomarkers Prev. 2011;2010:2099–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Earle CC. Long term care planning for cancer survivors: a health services research agenda. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;11:64–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Halpern M, Argenbright K.. Evaluation of effectiveness of survivorship programmes: how to measure success? Lancet Oncol. 2017;181:e51–e59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McCabe M, Bhatia S, Oeffinger K, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2013;315:631–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rechis R, Beckjord E, Arvey SR, et al. The essential elements of survivorship care: a LIVESTRONG brief; 2011. https://www.livestrong.org/sites/default/files/what-we-do/reports/EssentialElementsBrief.pdf. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 13. National Cancer Survivorship Resource Center. Systems policy and practice: clinical survivorship care. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/cancer-control/en/reports/systems-policy-and-practice-clinical-survivorship.pdf. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 14. Arksey H, O’Malley L.. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;81:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rowland JH, Gallicchio L, Mollica MA, et al. Survivorship science at the NIH: lessons learned from grants funded in fiscal year 2016. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;1112:109–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Comprehensive Cancer Control Program. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/ncccp/about.htm.

- 17. American Cancer Society. Cancer Survivors Network. https://csn.cancer.org/.

- 18. Loonen JJ, Bilijlevens NM, Prins J, et al. Cancer survivorship care: person centered care in a multidisciplinary shared care model. Int J Integr Care. 2018;181:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moore A, Buchanan N, Fairley T, et al. Public health action model for cancer survivorship. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(6 Suppl 5):S470–S476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nardi E, McCanney J, Winckworth-Prejsnar K, et al. Redefining quality measurement in cancer care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;165:473–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bevans M, El-Jawahri A, Tierney D, et al. National Institutes of Health Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Late Effects Initiative: the Patient-Centered Outcomes Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;234:538–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ganz PA. Improving the quality and value of cancer care: a work in progress-The 2016 Joseph V. Simone Award and Lecture. J Oncol Pract. 2016;1210:876–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jacobsen PB, Rowland JH, Paskett ED, et al. Identification of key gaps in cancer survivorship research: findings from the American Society of Clinical Oncology Survey. JOP. 2016;123:190–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Neuss M, Rocque G, Zuckerman D, et al. Establishing a core set of performance measures to improve value in cancer care: ASCO Consensus Conference Recommendation report. J Oncol Pract. 2017;132:135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mayer D, Fuld Nasso S, Earp J.. Defining cancer survivors, their needs, and perspectives on survivorship health care in the USA. Lancet Oncol. 2017;181:e11–e18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jacobs L, Shulman L.. Follow-up care of cancer survivors: challenges and solutions. Lancet Oncol. 2017;181:e19–e29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Recklitis C, Syrjala K.. Provision of integrated psychosocial services for cancer survivors post-treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2017;181:e39–e50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kosty MP, Hanley A, Chollette V, et al. National Cancer Institute-American Cancer Society of Clinical Oncology Teams in Cancer Care Project. J Oncol Pract. 2016;1211:955–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van Overveld LF, Braspenning JC, Hermens RP.. Quality indicators of integrated care for patients with head and neck cancer. Clin Otolaryngol. 2017;422:322–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nag N, Millar J, Davis ID, et al. Development of indicators to assess quality of care for prostate cancer. Eur Urol Focus. 2018;41:57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van Leeuwen M, Husson O, Alberti P, et al. Understanding the quality of life issues in survivors of cancer: towards the development of an EORTC QOL cancer survivorship questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;161:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ferrell B, Dow KH, Grant M.. Measurement of the quality of life in cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 1995;46:523–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zerillo JA, Schouwenburg MG, van Bommel ACM, et al. An international collaborative standardizing a comprehensive patient-centered outcomes measurement set for colorectal cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;35:686–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tremblay D, Latreille J, Bilodeau K, et al. Improving the transition from oncology to primary care teams: a care for shared leadership. J Oncol Pract. 2016;1211:1012–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness. Eff Clin Pract. 1998;11:2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Q. 2005;834:691–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;361:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wood ME, Vogel V, Ng A, et al. Second malignant neoplasms: assessment and strategies for risk reduction. J Clin Oncol. 2012;3030:3734–3745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Leach CR, Weaver K, Aziz NM, et al. The complex health profile of long-term cancer survivors: prevalence and predictors of comorbid conditions. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;92:239–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhao X, Ren G.. Diabetes mellitus and prognosis in women with breast cancer. Medicine. 2016;9549:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Barone B, Yeh H, Snyder C, et al. Long-term all-cause mortality in cancer patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2008;30023:2754–2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Patnaik JL, Byers T, Diguiseppi C, et al. The influence of comorbidities on overall survival among older women diagnosed with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;10314:1101–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hershman DL, Till C, Wright JD, et al. Comorbidities and risk of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy among participants 65 years or older in Southwest Oncology Group clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2016;3425:3014–3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Salz T, Zabor EC, de Nully Brown P, et al. Preexisting cardiovascular risk and subsequent heart failure among non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2017;3534:3837–3843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. National Cancer Institute. Cancer trends progress report: cancer survivors and obesity. https://progressreport.cancer.gov/after/weight. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 46. National Cancer Institute. Cancer trends progress report: cancer survivors and physical activity. https://progressreport.cancer.gov/after/physical_activity. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 47. National Cancer Institute. Cancer trends progress report: cancer survivors and smoking. https://progressreport.cancer.gov/after/physical_activity. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 48. Ng A, Kenney LB, Gilbert ES, et al. Secondary malignancies across the age spectrum. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2010;201:1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ballard-Barbash R, Friedenrich C, Courneya KS, et al. Physical activity, biomarkers, and disease outcomes in cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;10411:815–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Je Y, Jeon JY, Giovannucci EL, et al. Association between physical activity and mortality in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Cancer. 2013;1338:1905–1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Burton J. History of lymphoma. JAMA Oncol. 2018;43:292.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McCabe M, Partridge A, Grunfeld E, et al. Risk-based health care, the cancer survivor, the oncologist, and the primary care physician. Semin Oncol. 2013;406:804–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nekhlyudov L, O’Malley D, Hudson S.. Integrating primary care providers in the care of cancer survivors: gaps in evidence and future opportunities. Lancet Oncol. 2017;181:E30–E38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Paice JA, Portenoy R, Lacchetti C, et al. Management of chronic pain in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;3427:3325–3345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Andersen B, DeRubeis R, Berman B, et al. Screening, assessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: an American Society of Clinical Oncology Guideline Adaptation. J Clin Oncol. 2014;3215:1605–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt G, et al. The development and evaluation of a measure to assess cancer survivors’ unmet supportive care needs: the CaSUN (Cancer Survivors’ Unmet Needs measure). Psychooncology. 2007;169:796–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang B, Lloyd W, Jahanzeb M, et al. Use of patient-reported outcome measures in Quality Oncology Practice Initiative-registered practices: results of a national survey. J Oncol Pract. 2018;1410:e602–e611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck A, et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017;3182:197–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Abernethy AP, Etheredge LM, Ganz PA, et al. Rapid-learning system for cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2010;2827:4268–4274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Coverage & reimbursement for survivorship care services. https://www.asco.org/practice-guidelines/cancer-care-initiatives/prevention-survivorship/survivorship/survivorship-8. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 61. Rock C, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;624:243–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Gallaway M, Glover-Kudon R, Momin B, et al. Smoking cessation among cancer survivors: United States, 2015. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(suppl 7):111.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry L, et al. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;346:611–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Norton WE, Chambers DA, Kramer BS.. Conceptualizing de-implementation in cancer care delivery. J Clin Oncol. 2019;372:93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Armenian SH, Lacchetti C, Barac A, et al. Prevention and monitoring of cardiac dysfunction in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017;358:893–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hershman DL, Lacchetti C, Dworkin RH, et al. Prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2014;3218:1941–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. National Cancer Institute. Grid-Enabled Measures Database. https://www.gem-beta.org/Public/home.aspx. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 68. Crawford-Williams F, March S, Goodwin BC, et al. Interventions for prostate cancer survivorship: a systematic review of reviews. Psychooncology. 2018;2710:2339–2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. National Quality Forum. National Quality Forum: Quality Positioning System. https://bit.ly/1TAaf6R. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 70. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ quality indicators. https://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/Modules/PSI_TechSpec_ICD10_v70.aspx. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 71. International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement. Colorectal cancer: the standard set. https://www.ichom.org/medical-conditions/colorectal-cancer/. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 72. International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement. Breast cancer: the standard set. https://www.ichom.org/medical-conditions/breast-cancer/. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 73. International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement. Lung cancer: the standard set. https://www.ichom.org/medical-conditions/lung-cancer/. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 74. International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement. Advanced prostate cancer: the standard set. https://www.ichom.org/medical-conditions/advanced-prostate-cancer/. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 75. Core Quality Measures Collaborative. AHIP, CMS, and NQF partner to promote measure alignment and burden reduction. http://www.qualityforum.org/cqmc/. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 76. Bluethmann SM, Mariotto A, Rowland JH.. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer. Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;257:1029–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Practical steps to improving the quality of care and services using NICE guidance. https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/Into-practice/Practical-steps-improving-quality-of-care-and-services-using-NICE-guidance.pdf. Accessed May 27, 2019.

- 78. Kline RM, Muldoon LD, Schumacher HK, et al. Design challenges of an episode-based payment model in oncology: the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Oncology Care Model. J Oncol Pract. 2017;137:e632–e645. Accessed May 27, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]