Abstract

Vitamin C (VC) and vitamin D (VD) have been widely used as the dietary supplements and in treatment of diseases both independently and in combination. Whether there is a connection between their pathways is critical for their therapeutic applications. Using whole-genome expression profiles, we performed multiple measures of associations, networks, eQTL mappings and expressions of key genes of interest in VC and VD functions. Several key genes in their pathways were found to be associated. Gc and Rgn play important roles connecting VC and VD pathways in mice. The r values of expression levels between Gc and Rgn in mouse spleen, liver, lung, and kidney are 0.937, 0.558, 0.901, and 0.617, respectively. The expression QTLs of Gc and Rgn are mapped onto the same locations, i.e., 68–76 MB in chromosome 7 and 26–36 MB in chromosome 9. In humans, there are positive correlations between CYP27B1 and SLC23A1 expression levels in kidney (r = 0.733) and spleen (r = 0.424). SLC23A2 and RXRA are minimally associated in both mouse and human. These data indicate that pathways of VC and VD are not independent but affect each other, and this effect is different between mice and humans during VC and VD synthesis and transportation.

Subject terms: Metabolic pathways, Molecular medicine

Introduction

Vitamin C (VC) and vitamin D (VD) are indispensable for optimal health in humans. More than half a century ago, researchers found that VD deficiency could lead to rickets, and VC deficiency could lead to scurvy1,2. More recently many researchers have focused on the functions of VD and VC in different diseases and/or in different tissues3–7. Converging evidence suggests that VC and VD may exert similar effects in some circumstances. Wei et al. reported that there may be a moderate inverse association between dietary VC intake and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in middle-aged and older adults3. A different group found that timely initiation of VD supplementation is a critical determinant of treatment outcome in NAFLD4. VC and VD are each important in modulating bronchial asthma5. In addition, VD and VC both have pleiotropic effects on the immune, cardiovascular, and neurological systems and also share antineoplastic activity6,7. In spite of similarities between VD and VC functions in some diseases and human health, their applications in therapeutics and diet supplementation have largely been assessed independently, with little attention devoted to their potential interaction.

Key genes in VD pathways

With the help of ultraviolet B (UVB), both mouse and human body can synthesize Vitamin D3 from dehydrocholesterol (DHC). 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase (Dhcr7) is one of the regulatory genes in DHC production. Humans also obtain Vitamin D3 through diet. In the body, vitamin D3 is first converted to 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) and then to 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(1,25(OH)D3)8. Gc is the key gene to producing VD binding protein (DBP), which binds 25(OH)D and 1,25(OH)D3 in plasma. Vitamin D receptor (Vdr) in target cells binds specifically to 1,25(OH)D3 with high affinity9. A large number of genes are involved in VD molecular pathways in target cells. The most important ones are Cyp24a1, Trpv6, Cyp27b1, Cyp2r1, and Rxra which are studied in our lab8–10. Among them, Rxra is an obligatory co-receptor for Vdr mediating transcription11.

Key genes in VC synthesis and transport

Mice can synthesize vitamin C de novo. The pathway to synthesize vitamin C is through D-glucuronate, in which L-gulonate and L-gulono-γ-lactone serve as intermediate metabolites. Humans, some primates, and guinea pigs cannot synthesize vitamin C because their Gulo gene, which produces L-gulono-γ-lactone oxidase, is mutated. Senescence-marker protein-30 (SMP30) is essential for the conversion of L-gulonate to L-gulono-γ-lactone. SMP30 is produced by the regucalcin (Rgn) gene12. Two sodium-dependent transporters Slc23a1 and Slc23a2 (also referred to as Svct1 and Svct2), are important regulators in VC transport as well13. When Rgn or Slc23a2 are knocked out, mice cannot synthesize VC14. In this research we chose to study the role of Gulo, Rgn, slc23a1, and Slc23a2 in VC function and the role of Vdr, Gc, Cyp24a1, Trpv6, Cyp27b1, Cyp2r1, Dhcr7, and Rxra in VD function.

History of BXD strains

For over half a century, recombinant inbred (RI) strains of mice have been well-studied as models in biomedical research. In this research, we chose BXD RI strains, which represent the best developed animal model and have made significant contributions to the study of human diseases. The BXD families of RI strains were derived by crossing C57BL/6 J (B6) and DBA/2 J (D2) mice. Multiple generations of individuals from the F2 group were produced15. Theoretically, after more than 20 generations of inbreeding, most genetic sites of inbred animals should be homozygous. The BXD database can be downloaded from GeneNetwork, a public data source website that is a large whole genome expression resource platform. Using GeneNetwork, we worked to find potential overlap in synthesis and transport pathways of VC and VD.

Results

The crosstalk of key genes in gene network between VC and VD pathways

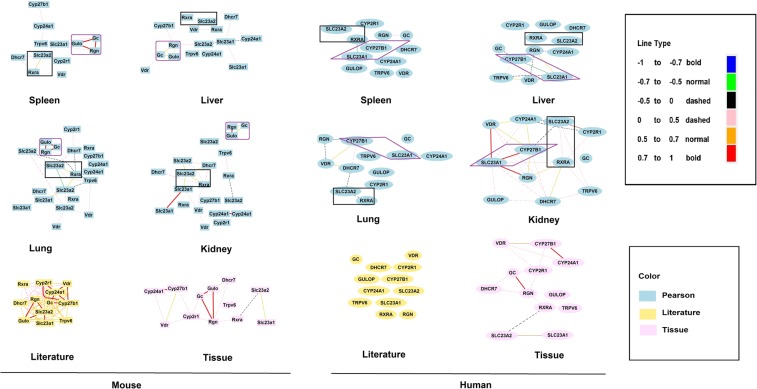

From the GeneNetwork platform, we first obtained the expression levels of VC key genes (Gulo, Rgn, Slc23a1, and Slc23a2) and VD key genes (Vdr, Gc, Cyp24a1, Trpv6, Cyp27b1, Cyp2r1, Dhcr7, and Rxra) from whole genome mRNA expression profiles in four different mouse and human organ tissues (spleen, liver, lung and kidney). Next, network graphs of these key genes were created using a threshold of absolute values greater than 0.35 as we previously reported16.

As shown in Fig. 1, in the pathways for VC and VD synthesis, it is obvious that Gc, Rgn, and Gulo in mice are tightly connected together compared to other genes in Pearson’s r value in the four tissues, especially in spleen and lung. The correlation between Gc, Rgn, and Gulo are all connected in red lines, depicting the positive correlations among them. We also examined correlations among these key genes reported in the literature for mouse and human tissue (Fig. 1). Correlations among these genes were more frequently reported for mice Correlations in mouse tissue showed similarity of expression in the same tissues among these key genes. GeneNetwork and the literature both support positive correlations among Gc, Rgn and Gulo, raising the question as to whether Gc is the key gene that overlaps in the VC and VD pathways in mice. However, since humans cannot synthesize VC due to a mutation in the Gulo gene, such a correlation is not present in humans. Furthermore, GC and RGN are not connected in humans.

Figure 1.

Different correlation levels among VC and VD key genes. The left portion shows correlations in mice and the right portion shows correlations in humans. Graphs in blue are Pearson’s correlations in four types of tissues. Literature correlation is presented in yellow and tissue correlation in pink. Different colors and thickness of line show different levels of correlation.

For the genes involved in transport of VC and VD, it seems that SLC23A1 is connected to CYP27B1 in humans in the spleen, liver, and kidney. The figures all show strong correlations between SLC23A1 and CYP27B1 in the tissues, except for the lung. The correlation is especially strong in the kidney. However, such a strong connection is lacking in mice. However, a clear connection between Slc23a2 and Rxra is present in both the mouse and human version of the genes (SLC23A2 and RXRA) are also connected. Thus, in post-synthesizing pathways there are both similarities and differences between humans and mice. Of note, in the human literature and tissue correlation analyses, connections between SLC23A1 and CYP27B1 are lacking.

Differences and similarities in patterns of correlation among key VC and VD genes

Since initial analysis of correlations among key genes in the VD and VC pathways showed both similarities and differences between mice and humans, we further examined in detail the correlation matrix among these genes in mouse spleen (N = 81), liver (N = 32), lung (N = 49), and kidney (N = 55) using the GeneNetwork platform with the Pearson coefficient17.

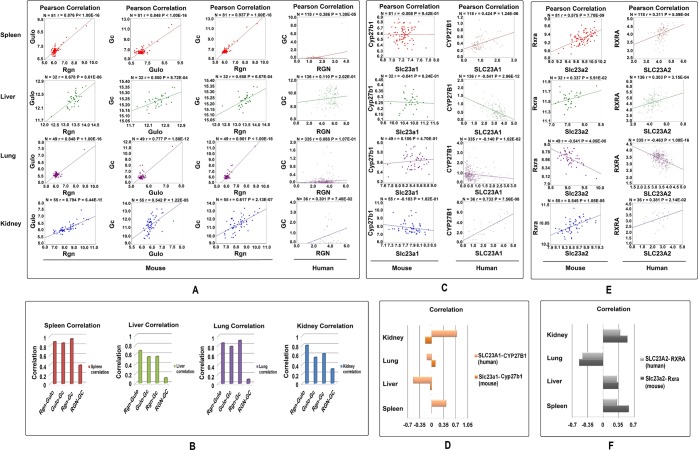

Figure 2A shows correlations in different tissues between Gulo and Rgn, Gc and Gulo, and Gc and Rgn in mouse and GC and RGN in human. Figure 2B summarizes the correlation between the expression levels of these genes. Correlations (r values) between Gulo and Rgn in mouse spleen, liver, lung, and kidney were 0.876, 0.678, 0.848, and 0.794, respectively. Correlations between Gc and Gulo in these four tissues in mice were 0.848, 0.550, 0.777, and 0.542, respectively. The R values between Gc and Rgn in these tissues of mice are 0.937, 0.558, 0.901, and 0.617, respectively. All of these correlations are statistically significant at less than 0.001. Rgn, Gc, and Gulo are highly expressed in mouse liver, and their correlations are more than 0.5 in this tissue. These detailed analyses in the four tissues confirm the positive correlation among these three genes. At the same time, the correlations of GC and RGN in humans are 0.386, 0.110, 0.088, and 0.301 (Fig. 2B), which means GC and RGN have a low degree of linkage in humans (as expected, since humans cannot synthesize VC). Further, we have found a similarly strong correlation between Gc and Rgn in rat tissues (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 2.

The correlations between paired key genes in four tissues, the spleen, liver, lung, and kidney. The number of samples, R value, and P value of each group are shown at the top of each graph. (A) Pearson’s correlations between Gulo and Rgn in mice, Gc and Gulo in mice, Gc and Rgn in mice, and GC and RGN in humans. (B) Correlation values between paired genes in four tissues. (C) Pearson’s correlations between SLC23A1 and CYP27B1 in humans, and Slc23a1 and Cyp27b1 in mice in the four tissues. (D) Correlation values of paired genes. (E) Pearson’s correlations between Rxra and Slc23a2 in mice and RXRA and SLC23A2 in humans. (F) Correlation values of paired genes in our tissues.

Figure 2C shows the detailed correlation between Cyp27b1 and Slc23a1 in mice and CYP27B1 and SLC23A1 in humans. Figure 2D summarizes correlations among these gene pairs in the four tissues. In humans, there are obvious positive correlations between the expression levels of CYP27B1 and SLC23A1 in kidney and spleen, with r values of 0.733 and 0.424. However, in liver the relation between these two genes is negative. In mice, there is no correlation between Cyp27b1 and Slc23a1, with r values between −0.183 and 0.106. Either positive or negative, at these low levels of R values, it means that they do not correlate. In liver the number of shared probes is the least between Gc and Rgn. However, even such a small number of shared genes are difficult to find when the two genes are not related. We have shown in the supplementary data that in pairs of non-relevant genes, there are no shared probes that are closely related to their expression levels.

Figure 2E,F show the correlation of expression levels between Rxra and Slc23a2 in mice and RXRA and SLC23A2 in humans. These weak connections are shown in a graphic gene network between the PAK pathway and RXRA in four tissues (Supplementary Fig. S2). In kidney, liver, and spleen, these gene pairs show positive correlations at the expression level while in lung they have a negative correlation. The P values of correlations in these tissues between humans and mice are similar, with a P value of 0.2890.

Data shown in Figs 1 and 2 suggest there are both similarities and differences in regulation of synthesis and transport pathway between VD and VC. In animals where Gulo is functional, Rgn and Gc have some linkage in VC and VD pathways. The correlation between Rgn and Gc in humans in these tissues is significantly lower than that in mice. The P value of correlations between mice and humans is 0.0173. However, due to the non-functional GULO gene in human, almost all the VC is obtained from the diet, thus RGN and GULO do not play any role in linkage of the VC and VD synthetic pathways. After VC intake, SLC23A1 and SLC23A2 start to transport VC to different tissues, and then the main linkage of VC and VD is between Rxra and Slc23a2 in mice and RXRA and SLC23A2 in humans. In addition, there is an alternative pathway that may connect VC and VD through SLC23A1 and CYP27B1. Such a linkage has not been demonstrated in mice.

Significant variations in the similarities of top 100 probes that are most correlated to key genes in the VC and VD pathways in mice

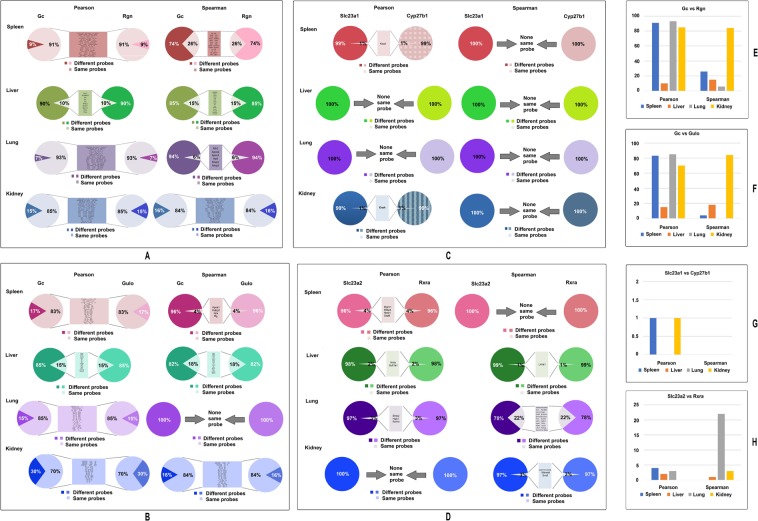

The linkage between key genes in VD and VC pathways and significant differences in their patterns of correlations raises a question as to what the similarities and differences among the top genes are and which expression levels are closely associated with the key genes. The method of exploration was to compare the top 100 most correlated genes between each correlated pair of genes, as we previously explained except we obtained the top 100 instead of 5016. Again, using GeneNetwork tools, the top 100 probes that have their expression levels most correlated with that of the expression level of each gene were identified. We first compared the similarities between the top 100 probes from Gc and Rgn. For the correlation, we used both Pearson and Spearman’s correlation (Fig. 3A,E). We found that in the kidney more than 80 probes of Gc and Rgn are the same using both Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients. In the spleen the Pearson correlation showed that as many as 91 probes are the same. This extremely similar phenomenon is usually rare when other genes are compared to each other. The results suggest that Gc and Rgn have a strong relationship in these tissues. In liver the number of shared probes is the least between Gc and Rgn. However, even such a small number of shared genes are difficult to find when the two genes are not related. We have shown in the supplementary data that in the pairs of non-relevant genes, there are no shared probes that are closely related to their expression levels (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 3.

The similarities between Gc and Rgn’s top 100 probes in spleen, liver, lung, and kidney of mice. Each group shows the percentage of same and different probes in the top 100 probes, and the names of probes which are the same between a pair of genes.

Similarly, large numbers of the same genes were found among the top 100 most correlated probes to GC and Gulo among four tissues (Fig. 3B,F). Similarly, large numbers of the same genes were found among the top 100 most correlated probes to GC and Gulo among three tissues except in liver. By Pearson coefficient, the number of same genes is 83, 15, 85, and 70 in spleen, liver, lung, and kidney, respectively. By Spearman’s coefficient, the numbers were 4, 18, 0, and 84, respectively. In order to re-affirm the relationship in the liver, we have done the same analysis with data from rat liver that confirmed the finding from mouse liver (Supplementary Fig. S3).

The top 100 most correlated genes to Slc23a1 and Cyp27b1 are compared in mice (Fig. 3C,G). While one gene in mouse spleen and kidney were found to be the same between Slc23a1 and Cyp27b1 by Pearson coefficient, the same result was not found using the Spearman’s coefficient.

Genes from the top 100 most correlated genes were found to be the same between Rxra and Slc23a2 in mice using the two statistical coefficient methods (Fig. 3D,H). In mice the number of the same genes found by using Pearson’s coefficient were 4, 2, 3, and 0 in spleen, liver, lung, and kidney respectively. Using Spearman’s coefficient, the same genes were 0, 1, 22, and 3, respectively. In contrast, there were no same probes among the top 100 genes derived from genes in unrelated pathways, such as the top 100 genes from Il1rn, Avpr1a, Vdr, and Lep (Supplementary Table S2).

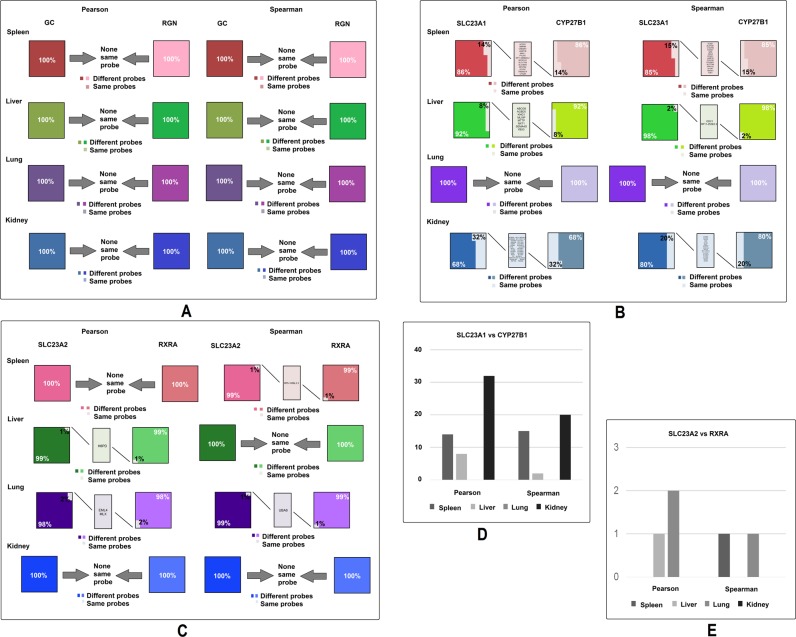

Significant variations in the similarities of top 100 probes that are most correlated to key genes in the VC and VD pathways in humans

Using the same method from the mouse analysis, we analyzed the top human probes of three gene pairs, GC and RGN, SLC23A1 and CYP27B1, and RXRA and SLC23A2. Surprisingly, there is no identical probe in the top 100 most correlated probes of GC and RGN, regardless of whether Pearson or Spearman’s calculations are employed (Fig. 4A). These data support the conclusion that the correlation in mice between this pair of genes does not exist in humans. P values comparing the number of genes in mice (Fig. 3A,E) and in humans by Pearson’s coefficient was 0.0398 and Spearman’s was 0.1591; the combination of the two is 0.0085.

Figure 4.

The similarities between Gc and Rgn’s top 100 probes in spleen, liver, lung, and kidney of humans. Each group shows the percentage of same and different probes in the top 100 probes, and names of the probes which are the same between genes in the pair. (A) Comparison of top 100 most closely correlated genes between GC and RGN in the four tissues, using both Pearson’s and Spearman’s coefficient. (B) Comparison of top 100 most closely correlated genes between SLC23A1 and CYP27B1 in the four tissues, using both Pearson’s and Spearman’s coefficient. (C) Comparison of top 100 most closely correlated genes between SLC23A2 and RXRA in four tissues, using both Pearson’s and Spearman’s coefficient. (D) Number of the same genes among top 100 most closely correlated genes between SLC23A1 and CYP27B1 in four tissues, using both Pearson’s and Spearman’s coefficient. (E) Number of the same genes among top 100 most closely correlated genes between SLC23A2 and RXRA in four tissues, using both Pearson’s and Spearman’s coefficient.

Next, we compared the top 100 most correlated genes to SLC23A1 and CYP27B1 in humans (Fig. 4B,D). A large number of probes were found to be the same between SLC23A1 and CYP27B1 among the spleen, liver, and kidney using both Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlations coefficient, except the lung. The number of the same genes in spleen, liver, lung, and kidney by Pearson’s coefficient were 14, 8, 0 and 32, respectively, and by Spearman’s coefficient were 15, 2, 0, and 20, respectively. P values comparing the number of genes in mice (Fig. 3C,G) and in humans by Pearson’s is 0.1422, by Spearman’s is 0.1548, and the combination of the two is 0.0235. These data support the conclusion that the role between SLC23A1 and CYP27B1 in linkage between VD and VC pathway is more important in humans than in mice.

Lastly, we compared the top 100 most correlated genes to RXRA vs SLC23A2 in humans (Fig. 4C,E). While in humans there are some genes that are the same between the top 100 most closely correlated genes of one to the other, there are fewer numbers of identical genes in humans than in mice. The number of identical genes in spleen, liver, lung, and kidney by Pearson’s coefficient were 0, 1, 2 and 0, respectively, and by Spearman’s coefficient were 1, 0, 1, and 0, respectively. P values comparing the number of genes in mice and in humans by Pearson’s coefficient were 0.1817, by Spearman’s is 0.3216, and the combination is 0.1813. Thus, a slightly weaker correlation between this pair of gene exists in humans and a stronger one in mice (Fig. 3D,H).

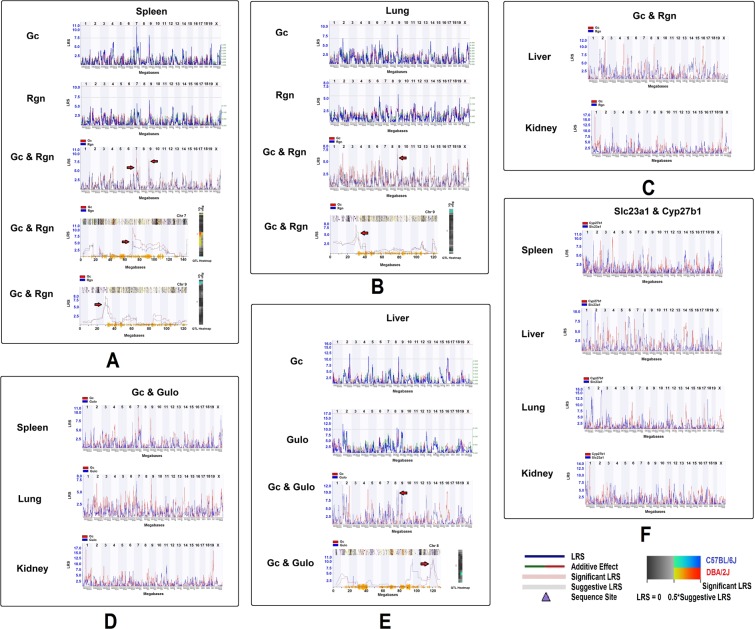

eQTL mapping in Gc and Rgn in mouse

Due to the availability of genotypes of BXD strains, we were able to examine the regulatory loci of these key genes in mice. The eQTL of Gc and Rgn from the four tissues studied were obtained from GeneNetwork using an interval mapping tool with 1000 permutations and with all the expression data from BXD strains without removing outliers from data from the four tissues. We conducted two separate mapping procedures, mapping Gc and Rgn individually and mapping them together. When mapped individually, the result suggested that Gc has a possible eQTL in both chromosome 7 and chromosome 9 in spleen (Fig. 5A). The highest LRS (Likelihood ratio statistic) of Rgn is also in the same position on chromosomes 7 and 9 although the eQTL did not reach a significant LRS. When mapping Gc and Rgn together, the result showed they are in the same location, 68–76 MB in chromosome 7 and 26–36 MB in chromosome 9 (Fig. 5A, picture at bottom row). While in the lung, eQTL from Gc and Rgn both reached suggestive levels in chromosome 9, in a similar location as that in the spleen, between 28–34 MB (Fig. 5B). The heatmap showed the same results as that of the eQTL mapping (Fig. 5A,B). No significant eQTL was identified from liver or kidney (Fig. 5C). Although the eQTL of Gc and Gulo from spleen, lung, and kidney rose to a significant level, they were mapped on chromosome 9 in both the spleen and lung (Fig. 5D). In addition, in liver, an eQTL on chromosome 8 was obtained by individual and combined mapping (Fig. 5E). No significant eQTL was identified between Slc23a1 and Cyp27b1, although a potential locus on chromosome 8 was mapped from both spleen and liver (Fig. 5F).This analysis identified a strong association between Gc and Rgn, Gc and Gulo, and between Slc23a1 and Cyp27b1. This result further enhances the assumption that there are connections between VD and VC pathways in mice.

Figure 5.

Locations of eQTLs that regulate the expression levels of key genes in mice. On the left of each picture is the LRS, which measures the association of linkage between the expression levels of key genes and particular genotype markers on mouse chromosomes. Each heatmap is shown at the right of the eQTL figure. (A) The locations of eQTLs on chromosome 7 and 9 that regulate the expression levels of Gc and Rgn in spleen. (B) Locations of eQTLs that regulate the expression levels of Gc and Rgn on chromosome 9 in lung of mouse. (C) eQTL mapping of expression levels of Gc and Rgn in liver and kidney. (D) The potential eQTL that regulate Gc and Gulo in tissues of spleen, lung and kidney. (E) The eQTL locations that regulate the expression of Gc and Gulo on chromosome 8 in liver. (F) The eQTL mapping of Slc23a1 and Cyp27b1 in four tissues.

Key genes were expressed differently in one pathway when the key gene in another pathway was affected

The expression levels of VC and VD key genes in Sfx mice and Balb/c mice were examined to determine whether there is a difference in expression levels in VD key genes when a VC key gene was knocked out. As is shown in Table 1, all the groups showed that when Gulo was knocked out, no matter whether the supplied drinking water contained VC or not, some VD key genes were expressed differently in the Sfx group than the Balb/c group. The two analysis in femurs showed similar differences, while the differences between two femur groups are the mice age and the analyzed methods.

Table 1.

Different gene expression levels of VC and VD key genes in Sfx with /without VC treatment and Balb/c mice.

| Tissue | Symbol | Sfx with VC | Sfx without VC | Balb/c | F Log Ratio | M Log Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | F | M | F | M | ||||

| Femur (7 weeks mice) | Vdr | 809 ± 87.7 | 780 ± 73 | 810.7 ± 102.8 | 743 ± 185 | 623.1 ± 13.4 | 557.6 ± 50 | — | — |

| Gc | 188.1 ± 4.3 | 174.6 ± 10.7 | 167.7 ± 7.1 | 170.9 ± 2.7 | 287.1 ± 24.6 | 268.5 ± 137.1 | — | — | |

| Dhcr7 | 365.7 ± 49.4 | 362.1 ± 8 | 343.9 ± 8.2 | 342.3 ± 10.8 | 281.7 ± 34.5 | 205.6 ± 60.3 | — | — | |

| Rxra | 226.4 ± 10.2 | 223 ± 1.8 | 223.7 ± 3.5 | 204 ± 7.3 | 314.3 ± 40.2 | 382.8 ± 51.2 | — | — | |

| Rgn | 189.6 ± 2.1 | 197.9 ± 2.4 | 184.4 ± 9.6 | 189.7 ± 6 | 245.3 ± 67.5 | 239.8 ± 71 | — | — | |

| Slc23a1 | 193.9 ± 11.1 | 194.3 ± 5.7 | 192.5 ± 11.9 | 199.6 ± 3 | 252.5 ± 37.7 | 253.8 ± 72.6 | — | — | |

| Slc23a2 | 423 ± 46.1 | 406 ± 23.9 | 503.9 ± 63 | 472.9 ± 15.8 | 266.5 ± 50 | 256.9 ± 137 | — | — | |

| Gulo | 187.3 ± 15 | 183 ± 3 | 181.2 ± 7.8 | 176 ± 3.2 | 269.8 ± 14.2 | 284.9 ± 81.8 | — | — | |

| Muscle | Cyp2r1 | 193.7 ± 12.3 | 191.8 ± 28 | 156.8 ± 4.3 | 157.4 ± 1.3 | 156.5 ± 0.6 | 147.7 ± 1.7 | — | — |

| Rxra | 320.3 ± 17.5 | 339.4 ± 31.2 | 379.5 ± 72.1 | 365.5 ± 8.5 | 262.3 ± 18.6 | 255.7 ± 19.5 | — | — | |

| Slc23a2 | 201.2 ± 8 | 173 ± 5.3 | 159.1 ± 11 | 157.5 ± 3.8 | 154 ± 5.9 | 151 ± 7.8 | — | — | |

| Gulo | 173.9 ± 8.1 | 183 ± 39.5 | 159 ± 0.3 | 151.4 ± 3.3 | 151.6 ± 5 | 147.7 ± 4.8 | — | — | |

| Femur (6 weeks mice) | Vdr | — | — | 420.5 | 658.6 | 547.1 | 1189.7 | −0.6 | −0.8 |

| Vdr | — | — | 335.5 | 430.0 | 158.3 | 883.9 | 1.0 | −1.1 | |

| Gc | — | — | 4648.7 | 785.7 | 1482.8 | 1028.4 | 1.6 | −0.5 | |

| Rgn | — | — | 855.6 | 161.5 | 743.7 | 456.9 | 0.2 | −1.0 | |

| Liver | Gc | 62635.6 | — | — | — | 49704.3 | — | 0.4 | — |

| Dhcr7 | 3282.4 | — | — | — | 2753.2 | — | 0.4 | — | |

| Rgn | 40842.4 | — | — | — | 31661.3 | — | 0.3 | — | |

| Slc23a2 | 2296.0 | — | — | — | 1259.1 | — | 0.7 | — | |

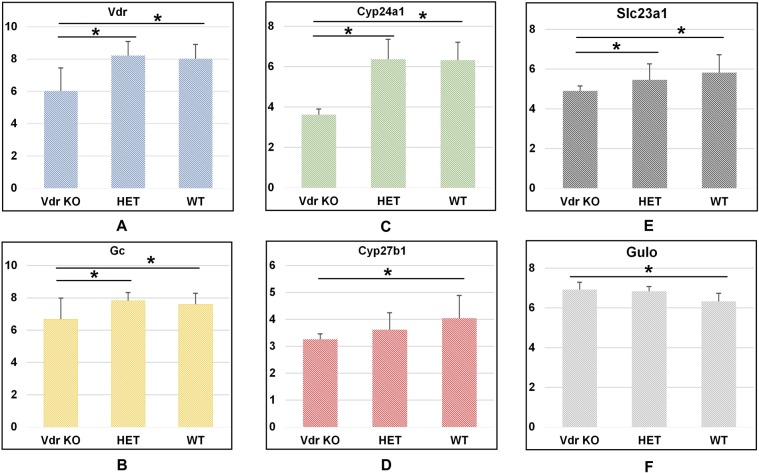

For the analysis of data of Vdr knockout mice, we downloaded the database (details described in methods) and sorted the different expression results in the key genes of VC and VD. As can be seen in Fig. 6, when Vdr was knocked out, the expression levels of the associated gene were altered, including Cyp24a1, Gc, and Cyp27b1. In addition, the expression levels of Slc23a1 and Gulo also showed significant differences when compared between the Vdr knockout group and the wildtype group (P < 0.05). The expression levels of those key genes are not affected in arthritic mice models with the non-mutated Gulo gene when compared to healthy control mice (Supplementary Table S1). These results support our hypothesis that the expression levels of VC and VD key genes influence each other.

Figure 6.

Different expression levels of VC and VD key genes in Vdr knockout mice group, Vdr heterozygous mice group, and wildtype mice group. *Represents P < 0.05. Numbers on the vertical lines indicate the relative expression level of genes.

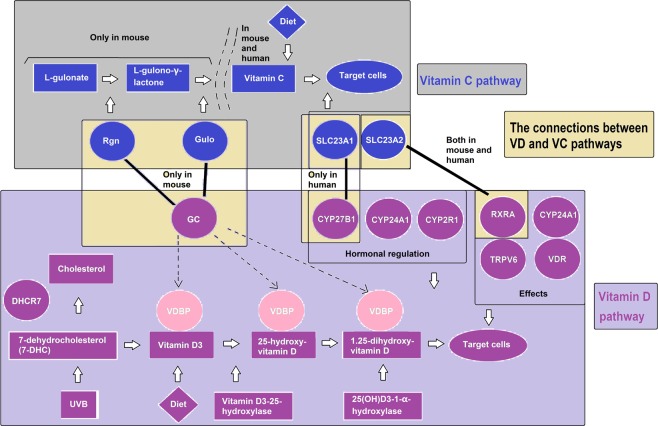

Discussion

Our data reveals for the first time the potentially key switch in the relationship between VC and VD pathways. To illustrate such an overlap, we have drawn a pathway diagram (Fig. 7). In Fig. 7, the upper part of the figure shows the VC synthesis and transport pathway. In mice and many other animals, it is through Rgn and Gulo, by which L-gulonate becomes L-gulono-γ-lactone and finally becomes VC. Slc23a1 and Slc23a2 are transporters for VC in vivo.

Figure 7.

A hypothesis about the overlap between VC and VD synthesis and transport pathways. The VC and VD pathways are shown at the top and bottom of the figure while the interactions are shown in the middle. The black bold lines represent the VC and VD interaction.

VD synthesis and transport pathways are illustrated in the lower part of Fig. 7. Vitamin D3 from UVB and diet are bound by VDBP until transport to target cells. VDBP is encoded by Gc. In the kidney, hormonal regulation significantly impacts the VD pathway and CYP27B1, CYP24A1, CYP2R1. RXRA, CYP24A1, VDR, and TRPV6 are all functional in VD target cells.

In the middle part of Fig. 7 we illustrate how these two pathways are possibly connected. Our results show that Rgn is connected with Gc only in mice and SLC23A1 is connected with CYP27B1 only in humans. Gulo weakly connects with Gc in mice. Slc23a2 connects with RXRA both in mouse and human. There may be some unknown genes involved in regulation, leading to their association.

A series of reported evidence supports our views. A recent study showed that plasma levels of vitamin D correlated with those of vitamin E and vitamin C17. Da Costa et al. reported levels of vitamin D-binding protein were inversely associated with levels of ascorbic acid in humans when they focused on identifying plasma proteins associated with circulating levels of ascorbic acid18. Our data also suggest that the associations between VD and VC can be direct or indirect. The direct association may be linked by Rgn and Gulo, Gc and Rgn in mouse, or SLC23A1 and CYP27B1 in humans. SLC23A1 and CYP27B1 are both highly expressed in kidney, and they also show a linkage in other tissues. The indirect associations could be through multiple ways connected by some other related genes, as we showed in the top 100 closely correlated genes to them, which need to be further studied.

A critical issue is that different individuals may utilize VD or VC with different efficiency, as the pathways are not independent. Our data may partially clarify why results of studies on the effects of VD and VC vary, i.e., because one element is affected by the other19. Our data may also explain why the value of VD deficiency thresholds (in measured by 25(OH)D) also varies19–21. Similarly, recommended optimal VC and VD levels have also generally been independent, without considering possible interactions.

Equally important, VC and VD have been used in combination with other agents in the treatment of disease22–25. According to our data, the optimal amount of VC or VD when used in treatment should be based on the balanced levels of both VC and VD. It is understandable that results of different combinations among drugs and VC or VD may also differ due to particular interactions between the drug and VC or VD. It is necessary to investigate whether it is optimal to add other vitamins to work synergistically to produce a better therapeutic effect.

The key genes in the connection between VC and VD may be used as alternative targets in disease treatment, nutrition, and supplementation. In addition to their function in VC and VD pathways, these genes have other important functions26,27. When these genes are utilized, their association may influence each other, which in turn, may affect the VC and VD pathway. Thus, a much broader effect of these genes should be considered when they are used for other purposes.

In this article, we focus on the mRNA expression level or genomic levels, not on protein levels. However, with multiple analyses with different methodologies and at different levels, we have found evidence to demonstrate that some overlap exists between VC and VD synthesis and transport pathways. It is clear that additional studies such as at protein levels should be conducted in the future. Our study has several limitations. First of all, most of our analyses are based on mouse models, or gene expressions profiles at one time point. The human sample is from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project, with a sample of around 500 that was 85% Caucasian. Secondly, we did not test for potential sex differences. Thirdly, the mouse data are mainly from BXD RI strains, which were derived from two parental strains, (C57B6/J and DBA/2 J), and thus may not represent all mouse strains. Furthermore, our analysis is only based on the association of the expression levels between genes. Influence by polymorphism and other epidermal factors was not been considered. Further studies on verification of these results and further analysis of potential age and sex differences will advance research into mechanisms of VD and VC effects.

In summary, our study suggests that in mice, the VC and VD functional pathways are connected mainly through Gc-Rgn and Gc-Gulo. In humans, the connection is mainly through SLC23A1 and CYP27B1. The significant differences raise the question of whether it is suitable to conduct research using VC endogenous production rodent models. The association between VD and VC pathways indicates a need for both to be considered in their nutritional and therapeutic applications.

Methods

Data source

All the relevant data were derived from GeneNetwork which is publicly accessible via http://www.GeneNetwork.org. We separately analyzed BXD strains’ whole genome expression profile in spleen (UTHSC Affy MoGene 1.0 ST Spleen (Dec10) RMA), liver (GSE16780 UCLA Hybrid MDP Liver Affy HT M430A (Sep11) RMA)28, lung (HZI Lung M430v2 (Apr08) RMA), and kidney (Mouse kidney M430v2 Sex Balanced (Aug06) RMA). These four sets of data using the GeneNetwork platform were the best resource for us to explore whether VC and VD have relationships. For humans, we chose whole genome expression data at GTEx V5 group in GeneNetwork and chose the same tissues as we have used in mice29,30.

Sfx mice were used to validate the connection of key genes in the VC and VD pathways. The key gene in VC synthesis, Gulo, was mutated in the Sfx mice. Because Sfx mice are under Balb/c background, Balb/c mice were used as the control group. The microarray data has been reported in previous studies31,32. RNA extract and data analysis followed our previous procedures31. These experiments were designed to compare the expression level in Sfx mice with/without VC treatment and in Balb/c mice, and the tissues included liver, femur, and muscle. Real-time PCR was applied to validate the microarray results.

The data from a public database in NCBI GEO DataSets (GSE61583) was used to confirm that VC genes are affected when Vdr was knocked out. The study is an analysis of mouse placenta retrieved at day 18.5 pc with Vdr gene knockout. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE61583). Mice were divided into three groups: Vdr knockout mice group, Vdr heterozygous mice group, and wildtype mice group33,34.

Gene network construction

The graphic application tools in GeneNetwork can construct key genes of VC and VD pathways. We chose Spring Model layout (energy reduction) for all graphic subjects. Different correlations were drawn in different colors which are the same as in our previous publication16. We separately analyzed Pearson, Literature, and Tissue in different tissues of mouse and human.

eQTL mapping

We used the standard resolution provided by GeneNetwork to identify eQTL position. Interval mapping tools mapped each chromosome with 1000 permutation tests to compute eQTLs. Expression values from different strains are considered to be phenotypes. A molecular marker along the chromosome was used as the genotype of the position on the chromosome. Then, the expression value of the probability of a particular genotype at the test position between the two flanking markers was compared. Statistical probability was used to assess the significance of the eQTL at a location to ultimately produce an eQTL16.

Correlation between Gc and Rgn

The sample correlation is computed between expression levels of Gc or Rgn and any other traits in the sample database selected. Pearson’s Rank was chosen when the sample size is large. Spearman’s Rank was used when the sample size was small (<20) or when there are influential outliers. We separately computed the top 100 probes for Gc and Rgn in each tissue.

Statistical analysis

R values and P values were obtained from GeneNetwork automatically. We used standard criteria to categorize the strength of the correlation. Thus, when the R value was equal to or more than 0.7 or −0.7, we regarded the correlation as a strong positive or negative index. An R value of between 0.35 and 0.69 or between −0.35 and −0.69 was considered a weak correlation. We treated R values between 0 and 0.35 or between 0 and −0.35 as no correlation35.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Robert W. Williams’ research team at University of Tennessee Health Science Center for providing data and analytic tools in the GeneNetwork. The study was partially supported by a merit grant (I01 BX000671 to Weikuan Gu) from the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Memphis. We thank following people for providing the genome expression data to GeneNetwork: Drs Lu and Robert Williams, University of Tennessee Health Science Center; Aldons Lusis, University of California, Los Angeles; Klaus Schughart, Helmholtz Centre for Infection Research, Dept. Experimental Mouse Genetics Inhoffenstr, 7 Braunschweig, Braunschweig Germany; and The GTEx Consortium. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

Conception and design: Weikuan Gu, Ge Lou, Dianjun Sun. Data collection: Wei Dong, Cheng Tian, Yan Jiao, Savannah Blackwell. Data organization and analysis: Wei Dong, Cheng Tian, Savannah Blackwell, Weikuan Gu. Data interpretation, Weikuan Gu, Wei Dong, Arnold Postlethwaite. Drafting the manuscript: Wei Dong, Cheng Tian. Review and/or revision of the manuscript: Yan Jiao, Savannah Blackwell, Ge Lou, Arnold Postlethwaite, Weikuan Gu, Dianjun Sun. Providing funding to the study: Weikuan Gu, Yan Jiao, Ge Lou, Arnold Postlethwaite, DianJun Sun.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data will be available without restrictions.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Weikuan Gu, Email: wgu@uthsc.edu.

Dianjun Sun, Email: hrbmusdj@163.com.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-53074-9.

References

- 1.Akhtar S. Vitamin D Status in South Asian Populations - Risks and Opportunities. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016;56:1925–1940. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2013.807419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frei B, Birlouez-Aragon I, Lykkesfeldt J. Authors’ perspective: What is the optimum intake of vitamin C in humans? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012;52:815–829. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.649149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wei Jie, Lei Guang-hua, Fu Lei, Zeng Chao, Yang Tuo, Peng Shi-fang. Association between Dietary Vitamin C Intake and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study among Middle-Aged and Older Adults. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(1):e0147985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jahn Daniel, Dorbath Donata, Kircher Stefan, Nier Anika, Bergheim Ina, Lenaerts Kaatje, Hermanns Heike M., Geier Andreas. Beneficial Effects of Vitamin D Treatment in an Obese Mouse Model of Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Nutrients. 2019;11(1):77. doi: 10.3390/nu11010077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ginter E, Simko V. Deficiency of vitamin D and vitamin C in the pathogenesis of bronchial asthma. Bratisl. Lek. Listy. 2016;117:305–307. doi: 10.4149/bll_2016_060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jean, G., Souberbielle, J. C. & Chazot, C. Vitamin D in Chronic Kidney Disease and Dialysis Patients. Nutrients. 9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Grosso G, et al. Effects of vitamin C on health: a review of evidence. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2013;18:1017–1029. doi: 10.2741/4160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffer LJ, et al. Appropriate vitamin D loading regimen for patients with advanced lung cancer. Nutr. J. 2016;15:84. doi: 10.1186/s12937-016-0203-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tagliabue E, Raimondi S, Gandini S. Meta-analysis of vitamin D-binding protein and cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:1758–1765. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Brien KM, Sandler DP, Kinyamu HK, Taylor JA, Weinberg CR. Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms in Vitamin D-Related Genes May Modify Vitamin D-Breast Cancer Associations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:1761–1771. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hibler EA, et al. Association between polymorphic variation in VDR and RXRA and circulating levels of vitamin D metabolites. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010;121:438–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabbay KH, et al. Ascorbate synthesis pathway: dual role of ascorbate in bone homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:19510–19520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.110247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eck P, et al. Comparison of the genomic structure and variation in the two human sodium-dependent vitamin C transporters, SLC23A1 and SLC23A2. Hum. Genet. 2004;115:285–294. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1167-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu R, Schellhorn HE. Recent applications of engineered animal antioxidant deficiency models in human nutrition and chronic disease. J. Nutr. 2013;143:1–11. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.168690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peirce JL, Lu L, Gu J, Silver LM, Williams RW. A new set of BXD recombinant inbred lines from advanced intercross populations in mice. BMC Genet. 2004;5:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui J, et al. Potential effect on molecular pathways in different targeted genes in the VEGF family in retina - From the genomic point of view. Exp. Eye. Res. 2018;176:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2018.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Godala M, et al. The risk of plasma vitamin A, C, E and D deficiency in patients with metabolic syndrome: A case-control study. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2017;26:581–586. doi: 10.17219/acem/62453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Da Costa LA, García-Bailo B, Borchers CH, Badawi A, El-Sohemy A. Association between the plasma proteome and serum ascorbic acid concentrations in humans. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013;24:842–847. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alonso MA, Mantecón L, Santos F. Vitamin D deficiency in children: a challenging diagnosis! Pediatr. Res. 2019;85:596–601. doi: 10.1038/s41390-019-0289-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beitz R, Mensink GB, Fischer B, Thamm M. Vitamins–dietary intake and intake from dietary supplements in Germany. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002;56:539–545. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saggese G, et al. Vitamin D in childhood and adolescence: an expert position statement. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2015;174:565–576. doi: 10.1007/s00431-015-2524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdel-Wahab AF, et al. Vitamin D enhances antiepileptic and cognitive effects of lamotrigine in pentylenetetrazole-kindled rats. Brain Res. 2017;1673:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoseini R, Damirchi A, Babaei P. Vitamin D increases PPARγ expression and promotes beneficial effects of physical activity in metabolic syndrome. Nutrition. 2017;36:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puente, V., Demaria, A., Frank, F. M., Batlle, A. & Lombardo, M. E. Anti-parasitic effect of vitamin C alone and in combination with benznidazole against Trypanosoma cruzi. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 12, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Sikri K, et al. Multifaceted remodeling by vitamin C boosts sensitivity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis subpopulations to combination treatment by anti-tubercular drugs. Redox Biol. 2018;15:452–466. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim HS, et al. Senescence marker protein 30 deficiency increases Parkinson’s pathology by impairing astrocyte activation. Neurobiol. Aging. 2013;34:1177–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghaly S, et al. High Vitamin D-Binding Protein Concentration, Low Albumin, and Mode of Remission Predict Relapse in Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2456–2464. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett Brian J., Davis Richard C., Civelek Mete, Orozco Luz, Wu Judy, Qi Hannah, Pan Calvin, Packard René R. Sevag, Eskin Eleazar, Yan Mujing, Kirchgessner Todd, Wang Zeneng, Li Xinmin, Gregory Jill C., Hazen Stanley L., Gargalovic Peter S., Lusis Aldons J. Genetic Architecture of Atherosclerosis in Mice: A Systems Genetics Analysis of Common Inbred Strains. PLOS Genetics. 2015;11(12):e1005711. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.GTEx Consortium The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:580–585. doi: 10.1038/ng.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The GTEx Consortium Human genomics. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) pilot analysis: multitissue gene regulation in humans. Science. 2015;348:648–660. doi: 10.1126/science.1262110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan J, et al. Evaluation of gene expression profiling in a mouse model of L-gulonolactone oxidase gene deficiency. Genet Mol Biol. 2007;30:322–329. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572007000300004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiao Y, et al. Differential gene expression between wild-type and Gulo-deficient mice supplied with vitamin C. Genet Mol Biol. 2011;34:386–95. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572011005000031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson RL, et al. Vitamin D Receptor Gene Ablation in the Conceptus Has Limited Effects on Placental Morphology, Function and Pregnancy Outcome. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0131287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buckberry S, et al. The effect of Vdr gene ablation on global gene expression in the mouse placenta. Genom Data. 2015;6:72–3. doi: 10.1016/j.gdata.2015.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao, Y. et al. Sex Differences in Correlation with Gene Expression Levels between Ifi200 Family Genes and Four Sets of Immune Disease-Relevant Genes. J. Immunol. Res. 2018 (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data will be available without restrictions.