Abstract

Objective.

This meta-analysis examined 30 randomized controlled trials (32 study sites; 35 study arms) that tested the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for alcohol or other drug use disorders (AUD/SUD). The study aim was to provide estimates of efficacy against three levels of experimental contrast (i.e., minimal [k = 5]; non-specific therapy [k = 11]; specific therapy [k = 19]) for consumption frequency and quantity outcomes at early (1 – 6 months [kes = 41]) and late (8+ months [kes = 26]) follow-up time points. When pooled effect sizes were statistically heterogeneous, study-level moderators were examined.

Method.

The inverse-variance weighted effect size was calculated for each study and pooled under random effects assumptions. Sensitivity analyses included tests of heterogeneity, study influence, and publication bias.

Results.

CBT in contrast to minimal treatment showed a moderate and significant effect size that was consistent across outcome type and follow-up. When CBT was contrasted with a non-specific therapy or treatment as usual, treatment effect was statistically significant for consumption frequency and quantity at early, but not late, follow-up. CBT effects in contrast to a specific therapy were consistently non-significant across outcomes and follow-up time points. Of ten pooled effect sizes examined, two showed moderate heterogeneity, but multivariate analyses revealed few systematic predictors of between-study variance.

Conclusions.

The current meta-analysis shows that CBT is more effective than a no treatment, minimal treatment, or non-specific control. Consistent with findings on other evidence-based therapies, CBT did not show superior efficacy in contrast to another specific modality.

Keywords: Alcohol Treatment, Cognitive Behavioral, Drug Treatment, Meta-Analysis, Relapse Prevention

Introduction

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a leading behavioral approach for intervention with alcohol or other drug use disorders (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). Despite its widespread application, the last meta-analysis of CBT efficacy for substance use was conducted 10 years ago (i.e., Magill & Ray, 2009). This is a significant gap, given the role meta-analysis plays in guiding clinical practice decisions at both micro (e.g., individual providers) and macro (e.g., community agency administrators, public service funders) levels.

We define CBT as a time-limited, multi-session intervention that targets cognitive, affective, and environmental risks for substance use and provides training in coping skills to help an individual achieve and maintain abstinence or harm reduction. Applications in the field are often based on Marlatt and Gordon’s (1985) model of relapse prevention, and there are several manuals available for use with alcohol (e.g., Epstein & McCrady, 2009; Kadden et al., 1992; Monti, Abrams, Kadden & Cooney, 1989) or other drug use disorders (e.g., Carroll, 1998). CBT for addictions has a well-established evidence base, but this literature continues to evolve (Carroll & Kiluk, 2017). Further, qualitative reviews have concluded that CBT is more effective than no treatment, but have reported mixed results on key questions such as efficacy over another evidence-based therapy (Longabaugh & Morgenstern, 1999), effect variability by primary drug type (Mastroleo & Monti, 2013; McHugh, Hearon, & Otto, 2010), and the optimal timing of intervention effects (Carroll & Onken, 2005).

In quantitative reviews, Irvin and colleagues (1999) examined 26 experimental and quasi-experimental studies of relapse prevention. They reported a small overall effect size (r = .14, p < .05), and suggested relapse prevention was more effective for alcohol use disorder than for other substances and when delivered in combination with a pharmacological intervention. In 2009, Magill and Ray followed up this work with a meta-analysis of 53 experimental CBT studies, reporting a similar overall effect size (g = .15, p < .005), although findings related to superior effects with alcohol use disorder were not replicated. The latter meta-analysis additionally noted the conservative nature of the overall effect size given the types of contrast conditions in the clinical trials reviewed. Specifically, the effect of CBT over no treatment was large (g =.79, p < .005), but this type of contrast was rare (k = 6/53). In comparison, effects for non-specific contrasts (i.e., a passive, but time-matched or usual care control condition; e.g., treatment as usual, supportive therapy, drug counseling) and specific contrasts (i.e., another manualized therapy condition; e.g., Motivational Interviewing, Contingency Management) were small and more common in the literature (g =.15, p < .005, k = 32/53; g =.11, p < .05, k = 17/53, respectively). To our knowledge, this was the last CBT meta-analysis across substances, or for individual substances, conducted to date.

Given the long-standing use of CBT in addictions care as well as its continued evolution, an up-to-date meta-analysis is needed. Additionally, reviews of cognitive therapy more broadly highlight a need for meta-analytic knowledge on effectiveness with substance-using populations (Butler, Chapman, Forman, & Beck, 2006; Hofmann, Asnaani, Vonk, Sawyer, & Fang, 2012). The present meta-analysis provides an updated assessment of CBT efficacy with alcohol or other drug use disorders, and may also offer greater conceptual clarity than past quantitative reviews. Specifically, CBT efficacy when delivered in a stand-alone format, and not combined with another psychosocial (Dutra et al., 2008; Magill & Ray, 2009; McHugh et al., 2010) or pharmacological (Irvin et al., 1999; Magill & Ray, 2009) intervention, was the focus of the present report. These latter topics are worthy of meta-analysis in their own right, and including such studies could obscure effect size estimation for the effect modifying factors of primary interest to this study: 1) CBT efficacy by contrast type (i.e., minimal; non-specific therapy; specific therapy), 2) CBT efficacy by consumption outcome type (i.e., frequency; quantity) and 3) CBT efficacy at early (i.e., 1–6 months post-treatment) and late (i.e., 8+ months post-treatment) follow-ups. Effect estimates were additionally examined for validity and stability in sensitivity analyses (i.e., tests of heterogeneity, study influence, and publication bias).

Method

Primary Study Inclusion

Studies meeting inclusion criteria were English language, peer-reviewed articles published between 1980 and 2018. These were primary outcome reports of randomized controlled trials. All types of experimental control were of interest given the importance of this factor in predicting effect size magnitude in the addictions, mental health, and in psychotherapy more broadly (Imel, Wampold, Miller, & Fleming, 2008; Wampold & Imel, 2015; Wampold, Mondin, Moody, Stich, Benson, & Ahn, 1997; Wampold, 2001). Studies were included if they targeted adult populations (age ≥ 18) meeting criteria for an alcohol or other drug use disorder (DSM III-R through V; American Psychiatric Association, 1987; 1994; 2000; 2013) or problematic use (e.g., Saunders et al., 1993). The treatment must have been identified as either Cognitive Behavioral or Relapse Prevention, although some studies were included based on a description of key CBT elements such as functional analysis, avoidance of high risk situations, and/or coping skills training (see Supplemental Table 1 for details). Studies of CBT delivered in either individual or group format were included, but we excluded studies of CBT delivered as an integrative therapy combined with another psychosocial (e.g., COMBINE Cognitive Behavioral Intervention, Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention) or pharmacological intervention.

Literature Search

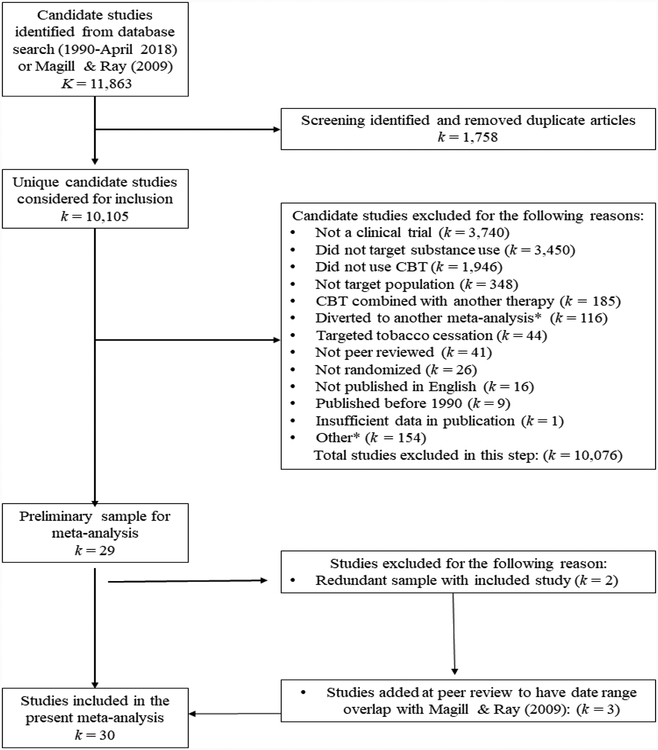

A literature search was conducted through June of 2018 to identify eligible studies for a large-scale, meta-analytic project on CBT in addictions care (R21AA026006). The first step involved a title, abstract, and keyword search by treatment (‘cognitive behavioral therapy’ OR ‘relapse prevention’ OR ‘coping skills training’), AND outcome (‘alcohol’ OR ‘cocaine’ OR ‘methamphetamine’ OR ‘stimulant’ OR ‘opiate’ OR ‘heroin’ OR ‘marijuana’ OR ‘cannabis’ OR ‘illicit drug’ OR ‘substances’ OR ‘dual disorder’ OR ‘polysubstance’ OR ‘dual diagnosis’), AND study terms (‘efficacy’ OR ‘randomized controlled trial’ OR ‘randomized clinical trial’) in the PubMed database. Then, a search of the Cochrane Register and EBSCO database (i.e., Medline, PsycARTICLES) was performed, removing duplicates from the results of the PubMed search. Abstract screening occurred by two raters in ABSTRKR (Wallace, Small, Brodley, Lau, & Trikalinos, 2012). A bibliographic search of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of CBT was also performed to identify any candidate studies not identified by the original search methods (Carroll, 1996; Carroll & Kiluk, 2017; Irvin et al., 1999; Longabaugh & Morgenstern, 1999; Magill & Ray, 2009; Mastroleo & Monti, 2013; Miller, Wilbourne, & Hettema, 2003; Prendergast, Podus, Chang, & Urada, 2002). Finally, three studies published between 1980 and 1989 were added during peer review to achieve an overlapping date range with Magill & Ray (2009; i.e., Donovan & Ito, 1988; Jones, Kanfer, & Lanyon, 1982; Kadden, Cooney, Getter, & Litt, 1989). Figure 1 provides a visual representation of study inclusion for the present report on stand-alone CBT efficacy with adult AUD/SUD; the figure follows QUORUM guidelines (Moher et al., 1999). The final meta-analytic sample was comprised of K = 30 studies, with 32 study sites (i.e., two studies provided two sites each, Project MATCH Research Group, 1997; McAuliffe, 1990), and a total of 5,398 participants.

Figure 1.

Flow of primary study inclusion.

Notes. K/k is defined as number of groups. CBT = cognitive behavioral therapy * E.g., dual diagnosis population; couples or self-help format; ineligible control condition.

Primary Study Characteristic Variables

There were several study characteristic variables of interest to this meta-analysis, as a priori effect size modifiers (i.e., subgroup variables) as well as potential pooled effect variance predictors (i.e., meta-regression covariates) in instances of systematic (i.e., versus random) between-study heterogeneity. Effect size modifiers were: 1) contrast condition type (i.e., minimal [e.g., waitlist, brief psychoeducation]; non-specific therapy [e.g., treatment as usual, supportive therapy, drug counseling]; specific therapy [e.g., Motivational Interviewing, Contingency Management]), 2) substance use outcome type (i.e., frequency; quantity), and 3) follow-up time point (early = 1–6 months post-treatment; late = 8+ months post-treatment). Study-level descriptors and potential meta-regression covariates were mean age, percent female participants, percent white participants, percent black participants, percent Latino/a participants, primary drug outcome (i.e., alcohol, other drug), substance use severity (i.e., dependence, abuse or heavy use), treatment length (i.e., number of planned sessions), treatment delivery (i.e., individual format, group format), study context (i.e., community sample, specialty substance use or mental health clinic, medical setting, college setting, criminal justice setting, other setting), publication country (i.e., United States, other country), use of biological assay outcome measure (i.e., yes, no), and study-level risk-of-bias (Higgins et al., 2011). Data extraction guidelines were detailed in a study codebook available, upon request, from the first author. Data were extracted in two independent passes conducted by trained raters (i.e., fourth and fifth authors), and showed a between-rater agreement rate of 95.3%. Final data entry, where disagreement was observed, required a consensus review with the first author.

Primary Study Outcome Variables

The standardized mean difference was used to measure efficacy outcomes in this meta-analysis.1 Hedges’ g includes a correction, f, for a slight upward bias in the estimated population effect (Hedges, 1994).

Prior to pooling, effect sizes were weighted by the inverse of the estimate variance to allow larger studies more influence on the overall effect size (Hedges & Olkin, 1985). Primary studies typically provided data on more than one outcome; therefore, data for effect size estimation were selected based on a decisional hierarchy in the following order: 1) biological assay measures, 2) measures of frequency or quantity in the form of means and standard deviations, 3) sample proportions, and 4) other outcomes (e.g., diagnostic measures [Addiction Severity Index; McLellan, Luborsky, Woody, & O’Brien, 1980]). When multiple months of follow-up date were provided, the latest time point in two time intervals was selected (i.e., 1–6 months, 8 + months). Effect sizes were reverse scored as needed (e.g., number of days drank) such that a positive effect size indicated a positive treatment outcome. Finally, when univariate outcome data were not reported, test statistics were transformed using available formulae (e.g., Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). When data from publications were insufficient for effect size calculation, raw data were obtained from authors where possible (i.e., Kadden, Litt, Cooney, Kabela, & Getter, 2001; Project MATCH, 1997). One eligible study was removed due to author non-response to data request (Källmén, Sjöberg, & Wennberg, 2003).

Data Analysis

Alcohol and other drug use effect sizes were pooled using a random effects model. In this approach, there is an assumed distribution for the population effect size with both systematic and random sources of variability (Hedges & Vevea, 1998). The significance of the Q-test determined whether statistically significant between-study heterogeneity existed within a given pooled estimate and the I2 provided a percent heterogeneity estimate, regardless of statistical significance.2 When I2 estimates exceeded 40%, indicating that 40% of the variance in effect sizes was due to systematic variance (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2015), a multivariate regression model was used to examine potential effect size moderators. Candidate variables were entered in participant (i.e., age, sex, race, primary drug, substance use severity), implementation, (i.e., treatment length, treatment delivery), and methodological (i.e., study risk-of-bias) blocks. Analyses were conducted with Wilson’s (2005) METAREG for Maximum Likelihood regression (ML; SPSS Version 24), and variables with significant regression coefficients were placed into a final predictive model along with residual variance estimates. Missing variable codes for regression covariates were mean imputed, and a predictor was removed from the analysis if imputed values reached 20% of total cases (Pigott, 1994). We conducted sensitivity analyses throughout data analysis and considered heterogeneity and moderator analyses as two primary methods for examining effect size validity. Trimmed estimates with influential studies removed (Baujat, Mahé, Pignon, & Hill, 2002) were also provided.3 Finally, to test for potential publication bias, the relationship between error and effect size was assessed using rank correlation (Begg & Mazumdar, 1994) and graphical methods (Egger, Smith, Schneider, & Minder, 1997). Here, small sample/small effect studies are assumed to characterize unpublished research, resulting in a significant and negative relationship, thus an asymmetrical funnel plot, when publication bias is present.

Results

Primary Study Descriptive Characteristics

The sample included 30 randomized trials, with 32 study sites, targeting CBT for adult substance use disorders published between 1982 and 2018. The median sample size was 102 participants with a minimum of 39 (Donovan & Ito, 1988) and a maximum of 952 (Project MATCH, 1997). The primary substance targets within these clinical trials were alcohol (k = 15), marijuana (k = 3), opiates (k = 2), stimulants (k = 6), and polydrug (k = 6) use. The samples’ mean age was 37 (SD = 6), samples were 30% female (SD = 20%) on average, and although report of race and ethnicity were inconsistent, the percentiles were as follows: 68% white (SD = 38%; k = 31/32), 36% black (SD = 37%; k = 18/32), and 12% Latino/a (SD = 27%; k = 13/32). Diagnostically, study inclusion primarily targeted individuals with alcohol or drug dependence (78%). The CBT interventions were 53% individual and 44% group delivered, and one study utilized a mixture of individual and group sessions (McKay et al., 2004). The median number of planned sessions was 12 (range = 6 to 40), and recruitment contexts included specialty substance use or mental health clinics (k = 18), community advertising (k = 11), and other specialty settings (e.g., college campus, medical setting, criminal justice system; k = 3). Study-level risk-of-bias assessment showed 60% of studies were low risk (Higgins et al., 2011). When studies were designated as unclear or high risk, this was typically due to the presence or no report of 1) baseline differences between conditions, 2) differential attrition between conditions, and 3) blinding of outcome assessment. Finally, the majority (72%) of studies were published in the United States. Tables 1 and 2 describe each study with respect to design characteristics, effect sizes, and are separated by early and late follow-up time points, respectively.

Table 1.

CBT efficacy at early follow-up by type of contrast condition

| First author (date) | N1 | Treatment | Contrast | Drug | Follow-up month | Outcome2 | Risk of Bias3 | g(se) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal/Waitlist Contrasts | ||||||||

| Kivlahan (1990) | 43 | alcohol skills training | assessment only | alcohol | 4 | drinks per week | L | .43(.36) |

| Lanza (2014) | 50 | cognitive behavioral therapy | waitlist | polydrug | 6 | rate abstinent | U | .27(.48) |

| McAuliffe (1990) - US | 88 | relapse prevention | referral | opiates | 6 | rate abstinent | L | .44(.26) |

| McAuliffe (1990) – HK | 80 | relapse prevention | referral | opiates | 6 | rate abstinent | L | .26(.32) |

| Stephens (2000) | 291 | relapse prevention | waitlist | marijuana | 4 | days used | L | 1.01(.16) |

| Stephens (2000) | 291 | relapse prevention | waitlist | marijuana | 4 | use per day | L | .75(.16) |

| Non-Specific Therapy Contrasts | ||||||||

| Bowen (2014) | 183 | relapse prevention | TAU | polydrug | 6 | days used | L | .26(.16) |

| Burtscheidt (2002) | 80 | coping skills training | non-specific support group | alcohol | 6 | rate abstinent | U | .12(.26) |

| Kivlahan (1990) | 43 | alcohol skills training | didactic alcohol information | alcohol | 4 | drinks per week | L | .46(.37) |

| McKay (1997) | 98 | relapse prevention | group counseling | polydrug | 6 | days used | L | −.14(.20) |

| McKay (2004) | 257 | relapse prevention | group counseling | polydrug | 6 | rate abstinent | U | .10(.13) |

| McKay (2010) | 75 | relapse prevention | TAU | cocaine | 6 | rate relapse | U | .00(.31) |

| Monti (1997) | 128 | coping skills training | attention placebo | cocaine | 6 | days used | L | .59(.20) |

| Morgenstern (2001) | 168 | cognitive behavioral therapy | TAU | polydrug | 6 | days abstinent | L | .08(.15) |

| Papas (2011) | 75 | cognitive behavioral therapy | TAU | alcohol | 3 | days used | L | .72(.24) |

| Papas (2011) | 75 | cognitive behavioral therapy | TAU | alcohol | 3 | drinks per day | L | .40(.23) |

| Stephens (1994) | 212 | relapse prevention | social support group | marijuana | 6 | days used | U | .01(15) |

| Specific Therapy Contrasts | ||||||||

| Brown (2002) | 133 | relapse prevention | twelve-step facilitation | polydrug | 6 | days to first lapse | L | −.23(.17) |

| Budney (2006) | 60 | cognitive behavioral therapy | contingency management | marijuana | 6 | days used | L | .32(.30) |

| Carroll (1991) | 42 | relapse prevention | interpersonal psychotherapy | cocaine | 1 | rate abstinent | H | .53(.35) |

| Donovan (1988) | 39 | relapse prevention | interpersonal process group | alcohol | 6 | days drank | U | .27(.35) |

| Heather (2000) | 91 | behavioral self-control | moderation cue exposure | alcohol | 6 | days abstinent | L | −.23(.23) |

| Heather (2000) | 91 | behavioral self-control | moderation cue exposure | alcohol | 6 | drinks per day | L | .41(.23) |

| Kadden (1989) | 96 | coping skills training | interactional group therapy | alcohol | 6 | days abstinent | U | .00(.19) |

| Kadden (2001) | 250 | cognitive behavioral therapy | interactional group therapy | alcohol | 6 | days abstinent | U | .17(.18) |

| Lanza (2014) | 50 | cognitive behavioral therapy | acceptance and commitment | polydrug | 6 | rate abstinent | U | −.41(.38) |

| Litt (2016) | 193 | cognitive behavioral therapy | network support therapy | alcohol | 6 | days abstinent | L | −.18(14) |

| Litt (2016) | 193 | cognitive behavioral therapy | network support therapy | alcohol | 6 | heavy use days | L | −.11(.14) |

| Maude-Griffin (1998) | 128 | cognitive behavioral therapy | twelve-step facilitation | cocaine | 4 | rate abstinent | L | .22(.21) |

| McKay (2010) | 75 | relapse prevention | contingency management | cocaine | 6 | rate relapse | U | −.22(.32) |

| P. MATCH (1997) - opt. | 952 | cognitive behavioral therapy | motivational interviewing/twelve-step facilitation4 | alcohol | 6 | days abstinent | L | −.05(.08) |

| P. MATCH (1997) - opt. | 952 | cognitive behavioral therapy | motivational interviewing/twelve-step facilitation4 | alcohol | 6 | drinks per day | L | .09(.08) |

| P. MATCH (1997) - aft. | 774 | cognitive behavioral therapy | motivational interviewing/twelve-step facilitation4 | alcohol | 6 | days abstinent | L | .06(.09) |

| P. MATCH (1997) - aft. | 774 | cognitive behavioral therapy | motivational interviewing/twelve-step facilitation4 | alcohol | 6 | drinks per day | L | −.06(.09) |

| Shakeshaft (2002) | 295 | cognitive behavioral therapy | brief intervention | alcohol | 6 | days heavy use | L | −.05(.12) |

| Sitharthan (1997) | 42 | cognitive behavioral therapy | cue exposure | alcohol | 6 | days used | L | −.61(.31) |

| Sitharthan (1997) | 42 | cognitive behavioral therapy | cue exposure | alcohol | 6 | drinks per day | L | −.66(.31) |

| Smout (2010) | 104 | cognitive behavioral therapy | acceptance and commitment | meth. | 6 | rate relapse | H | −.29(.50) |

| Smout (2010) | 104 | cognitive behavioral therapy | acceptance and commitment | meth. | 6 | grams per month | H | .16(.20) |

| Stephens (2000) | 291 | relapse prevention | motivational interviewing | marijuana | 6 | days used | L | .12(.15) |

| Stephens (2000) | 291 | relapse prevention | motivational interviewing | marijuana | 6 | use per day | L | .04(.15) |

Notes. keffect sizes = 41. TAU = treatment as usual, US = United States, HK = Hong Kong, opt. = outpatient, aft. = aftercare, meth. = methamphetamine.

If an arm of the trial did not contribute an effect contrast, the study-level sample size was adjusted.

Negative outcomes such as days used or number of times used per day were reverse-scored such that a positive effect estimate would reflect a positive treatment outcome.

Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (Higgins et al., 2011), L = low risk, U = unclear risk, H = high risk.

Active contrasts outcomes were pooled to provide a single estimate per outcome type and follow up for Project MATCH.

Table 2.

CBT efficacy at late follow-up by type of contrast condition

| First author (date) | N1 | Treatment | Contrast | Drug | Follow-up month | Outcome2 | Risk of Bias3 | g(se) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal/Waitlist Contrast Studies | ||||||||

| Kivlahan (1990) | 43 | alcohol skills training | assessment only | alcohol | 12 | drinks per week | L | .98(.38) |

| McAuliffe (1990) - US | 88 | relapse prevention | referral | opiates | 12 | rate abstinent | L | .35(.27) |

| McAuliffe (1990) - HK | 80 | relapse prevention | referral | opiates | 12 | rate abstinent | L | .60(.35) |

| Non-Specific Therapy Contrasts | ||||||||

| Bowen (2014) | 183 | relapse prevention | TAU | polydrug | 12 | days used | L | −.08(.16) |

| Burtscheidt (2002) | 80 | coping skills training | non-specific support group | alcohol | 30 | rate abstinent | U | .30(.46) |

| Jones (1982) | 45 | alcohol skills training | TAU | alcohol | 12 | days abstinent | U | .82(.46) |

| Jones (1982) | 45 | alcohol skills training | TAU | alcohol | 12 | mean consumption | U | .85(.46) |

| Kivlahan (1990) | 43 | alcohol skills training | didactic alcohol information | alcohol | 12 | drinks per week | L | .75(.38) |

| McKay (1997) | 98 | relapse prevention | group counseling | polydrug | 24 | days used | L | .09(.17) |

| McKay (2004) | 257 | relapse prevention | group counseling | polydrug | 12 | rate abstinent | U | .13(.13) |

| McKay (2010) | 75 | relapse prevention | TAU | cocaine | 18 | rate relapse | U | −.13(.32) |

| Stephens (1994) | 212 | relapse prevention | social support group | marijuana | 12 | days used | U | −.04(.15) |

| Thornton (2003) | 291 | Behavioral treatment | facilitative therapy | polydrug | 9 | ASI5 | U | −.04(20) |

| Specific Therapy Contrasts | ||||||||

| Budney (2006) | 60 | cognitive behavioral therapy | contingency management | marijuana | 12 | days used | L | −.01(.29) |

| Dawe (2002) | 100 | behavioral self-control | moderation cue exposure | alcohol | 8 | days used | U | .03(.22) |

| Dawe (2002) | 100 | behavioral self-control | moderation cue exposure | alcohol | 8 | days heavy use | U | .22(.22) |

| Litt (2016) | 193 | cognitive behavioral therapy | network support therapy | alcohol | 27 | days abstinent | L | −.14(.14) |

| Litt (2016) | 193 | cognitive behavioral therapy | network support therapy | alcohol | 27 | days heavy use | L | −.03(.14) |

| McKay (2010) | 75 | relapse prevention | contingency management | cocaine | 18 | rate relapse | U | −.36(.33) |

| P. MATCH (1997) - opt. | 952 | cognitive behavioral therapy | motivational interviewing/twelve-step facilitation4 | alcohol | 15 | days abstinent | L | −.05(.08) |

| P. MATCH (1997) - opt. | 952 | cognitive behavioral therapy | motivational interviewing/twelve-step facilitation4 | alcohol | 15 | drinks per day | L | .09(.08) |

| P. MATCH (1997) - aft. | 774 | cognitive behavioral therapy | motivational interviewing/twelve-step facilitation4 | alcohol | 15 | days abstinent | L | .09(.09) |

| P. MATCH (1997) - aft. | 774 | cognitive behavioral therapy | motivational interviewing/twelve-step facilitation4 | alcohol | 15 | drinks per day | L | −.11(.09) |

| Sandahl (2004) | 49 | cognitive behavioral therapy | psychodynamic therapy | alcohol | 15 | days abstinent | L | −.64(.29) |

| Stephens (2000) | 291 | relapse prevention | motivational interviewing | marijuana | 16 | days used | L | .06(.16) |

| Stephens (2000) | 291 | relapse prevention | motivational interviewing | marijuana | 16 | use per day | L | .02(.16) |

Notes. Keffect sizes = 26. TAU = treatment as usual, US = United States, HK = Hong Kong, opt. = outpatient, aft. = aftercare, meth. = methamphetamine.

If an arm of the trial did not contribute an effect contrast, the study-level sample size was adjusted.

Negative outcomes such as days used or number of times used per day were reverse-scored such that a positive effect estimate would reflect a positive treatment outcome.

Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool (Higgins et al., 2011), L = low risk, U = unclear risk, H = high risk.

Active contrasts outcomes were pooled to provide a single estimate per outcome type and follow up for Project MATCH.

Addiction Severity Index (McLellan et al., 1980).

CBT Effect by Contrast Type, Outcome Type, and Follow-up Time Point

CBT in contrast to minimal treatment.

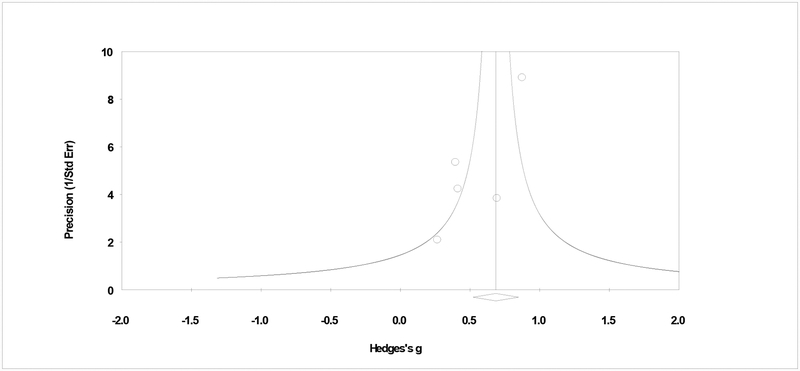

Primary study effect sizes were pooled by contrast type and within each subgroup, pooled effect sizes by frequency and quantity outcomes at early (i.e., 1 to 6 months) and late (i.e., 8 + months) follow-ups are provided. Studies with minimal, waitlist, or assessment only contrast conditions comprised a minority of the studies reviewed, and the pooled effect size for frequency outcomes was g = .58 (95% CI = .15, 1.01, p = .009; tau2 = .11, Q > .05, I2 = 59%; k = 4) at early follow-up and g = .44 (95% CI = .02, .86, p = .039; tau2 = .00, Q > .05, I2 = 0%; k = 2) at late follow-up. For quantity outcomes at early follow-up, the pooled effect size for two studies was moderate and significant (g = .67: 95% CI= .41, .98, p < .001; tau2 = .00, Q > .05, I2 = 0%; k = 2), but only one study provided late follow-up quantity data (Kivlahan, Marlatt, Fromme, Coppel, & Williams, 1990). Converting effect estimates to a percentile success rate (U3; Cohen, 1988), the data show 15 to 26% of CBT participants had better outcomes than the median of those in minimal treatment conditions. Analyses by minimal contrast showed no influential studies. Figure 2 shows some asymmetry in the plot of primary studies, by minimal contrast, but rank correlation analyses do not suggest bias due to publication status (τ = −.33, p = .497).

Figure 2.

Plot of assessment of publication bias.

Notes. Assessment of bias in CBT effect in contrast to a minimal condition. The plot shows some asymmetry, but the rank order correlation shows a non-significant relationship between precision and effect size (τ = −.33, p > .05).

CBT in contrast to non-specific therapy.

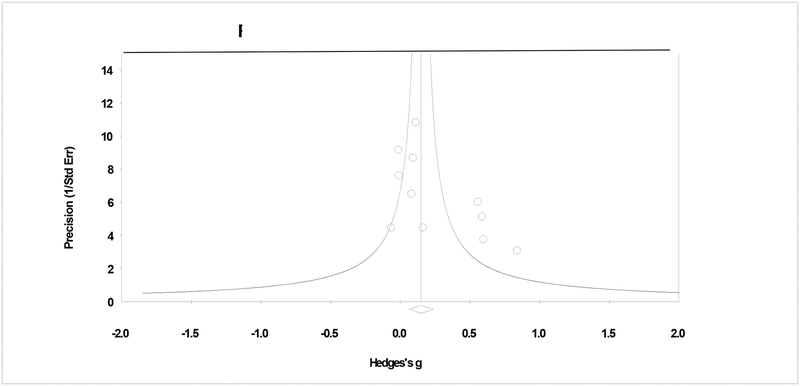

The second level of contrast included studies that compared CBT to some form of non-specific therapy such as treatment at usual, supportive therapy, or group drug counseling. The pooled effect size for frequency outcomes at early follow-up was small and statistically significant (g = .18: 95% CI = .02, .35, p = .04; tau2 = .03, Q > .05, I2 = 45%; k = 9)6 with a success rate roughly 8% higher than the median within the contrast condition. However, the effect was non-significant at late follow-up (g = .05: 95% CI = −.09, .19, p = .492; tau2 = .00, Q > .05, I2 = 0%; k = 7). For quantity outcomes at early follow-up, the pooled effect was moderate and significant for two studies (g = .42: 95% CI = .03, .81, p = .034; tau2 = .00, Q > .05, I2 = 0%), and only one study provided late follow-up quantity data (Kivlahan et al., 1990). Analyses of CBT in contrast to a non-specific therapy showed three influential studies that, when removed, the overall effect size became non-significant (gtrimmed ~ .07 to .26). Figure 3 shows the plot of primary studies, by non-specific contrast, and does not suggest bias due to publication status (τ = .36, p = .059).

Figure 3.

Plot of assessment of publication bias.

Notes. Assessment of bias in CBT effect in contrast to a non-specific therapy. The plot shows symmetry and the correlation test shows a non-significant relationship between precision and effect size (τ = .36, p > .05).

CBT in contrast to another specific therapy.

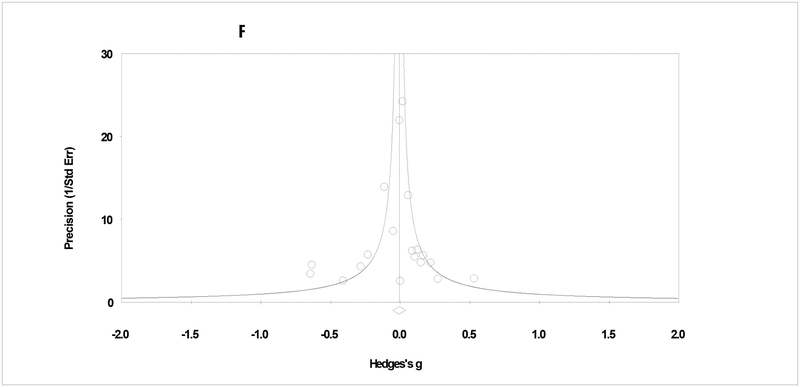

The third level of contrast included studies that compared CBT to another specific therapy (e.g., Motivational Interviewing, Contingency Management). The pooled effect size for frequency outcomes was non-significant at early (g = −.02: 95% CI = −.12, .08, p = .740; tau2 = .01, Q > .05, I2 = 14%; k = 16) and late (g = −.04: 95% CI = −.15, .08, p = .507; tau2 = .01, Q > .05, I2 = 15%; k = 8) follow-ups. For quantity outcomes, pooled effects were also non-significant at early (g = .01: 95% CI = −.11, .12, p = .956; tau2 = .01, Q > .05, I2 = 36%; k = 8) and late (g = .01: 95% CI = −.09, .11, p = 887; tau2 = .00, Q > .05, I2 = 0%; k = 5) follow-ups. Analyses of CBT in contrast to another specific therapy showed no influential studies and no evidence of publication bias (Figure 4; τ = .00, p = .500).

Figure 4.

Plot of assessment of publication bias.

Notes. Assessment of bias in CBT effect in contrast to a specific therapy. The plot shows symmetry and the correlation test shows a non-significant relationship between precision and effect size (τ = .00, p > .05).

Analysis of Heterogeneous Pooled Effect Sizes

Given variability in the types of contrast conditions within this sample of CBT efficacy trials, this meta-analysis did not provide a single pooled effect size to characterize the effect of CBT for adult AUD/SUD. Using a subgroup approach, two out of 10 pooled effect sizes were determined to have sufficient systematic heterogeneity to warrant moderator analyses. Of these two estimates (I2 range = 45 – 59%), only one subgroup also contained a sufficient k number of studies to provide variability in the covariates examined.4 For heterogeneous effects of CBT on early follow-up use frequency in contrast to a non-specific therapy (g = .18; Q > .05, I2 = 45%; k = 9), we used a meta-regression approach to conduct random effects moderator analysis. Within this approach, a priori covariates are considered, but residual heterogeneity is also expected and acceptable. Table 3 summarizes findings for the participant, implementation, and methodological models. These analyses yielded largely non-significant meta-regression estimates, with the exception of client age. For CBT effects on early follow-up use frequency in contrast to a non-specific therapy, older age was associated with smaller effect sizes (b = −.072, p = .044).

Table 3.

Study-level predictors of effect size heterogeneity

| Model | Beta | b | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Specific, early frequency | ||||

| Participant Block | ||||

| Mean age of participants | −1.225 | −.072 | −2.017 | .044 |

| Percent female participants | .160 | .003 | .347 | .729 |

| Percent white participants | −.728 | −.005 | −1.314 | .189 |

| Primary drug (reference = drug) | .798 | .547 | 1.636 | .102 |

| Substance use severity (reference = dependent) | −.470 | −.248 | −.969 | .332 |

| QE (5) = 4.874 | ||||

| QR (3) = 1.183 | ||||

| Implementation Block | ||||

| Treatment format (reference = group) | −.191 | −.068 | −.453 | .651 |

| Treatment length | −.708 | −.018 | −1.681 | .093 |

| QE (2) = 2.827 | ||||

| QR (6) = 3.229 | ||||

| Methodological Block | ||||

| Risk of bias (reference = low) | −.451 | −.232 | −1.110 | .267 |

| QE (1) = 1.232 | ||||

| QR (7) = 4.824 |

Notes. k = 9. QE and QR = chi-square explained and residual, respectively. Treatment length was measured in number of planned CBT sessions.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis of CBT efficacy for adults with alcohol and other drug use disorders conducted in 10 years, despite ongoing research and utilization of the CBT approach. We pooled primary study effect sizes by contrast condition type (i.e., minimal, non-specific therapy, specific therapy), and then by consumption outcome type (i.e., frequency, quantity) and follow-up time point (i.e., early, late). For the most part (k = 8/10), these subgroup estimates showed acceptable homogeneity. This suggests that the selected variables were informative effect size modifiers for the sample of clinical trials reviewed. Meta-analyses of alcohol or other drug treatments generally show effect sizes in the small to moderate range (e.g., Bertholet, Daeppen, Wietlisbach, Fleming, & Burnand, 2005; Lundahl, Kunz, Brownell, Tollefson, & Burke, 2010; Prendergast et al., 2002) and this includes pharmacological treatments (e.g., Fullerton et al., 2014; Maisel, Blodgett, Wilbourne, Humphreys, & Finney, 2013; Streeton & Whelan, 2001). In the present study, a moderate-to-large and stable (i.e., across outcome type and follow-up time point) effect size was observed for CBT in contrast to no treatment or a minimal treatment comparison (15–26% success rate). However, the majority of trials in this review considered CBT in contrast to an active comparison, either a non-specific or a specific therapy. In other words, the measure of efficacy in the CBT literature has most often been how well CBT performs in reference to another form of therapy.

In this meta-analysis, we selected two types of treatment outcomes a priori. These were alcohol or other drug use frequency and quantity. The goal was to consider both abstinence and harm reduction, although quantity outcomes (kes = 19) were reported less consistently than frequency outcomes (kes = 47), and only one study explicitly targeted substance use moderation (Heather et al., 2000). The current study can thus provide only preliminary data on the broader question of whether CBT is particularly effective for certain types of clinical outcomes. For example, Irvin and colleagues (1999) reported effect sizes for secondary outcomes (e.g., self-efficacy or coping skills) that were more than twice the magnitude of those for substance use. In the present study, CBT effect sizes for quantity outcomes were larger than frequency outcomes, such as number of abstinent days. This pattern of findings held for minimal and non-specific therapy contrasts, but caution is warranted due to the relatively smaller number of primary studies contributing quantity outcome effect estimates.

CBT effects in relation to the timing of follow-up assessment were examined in the present review. Here, outcomes were pooled at 1- to 6-month follow-up (i.e., early) and at 8 months or later (i.e., late). Further, a minority of early follow-up (Carroll et al., 1991; Smout et al., 2010; Papas et al., 2011; Stephens, Roffman, & Simpson, 2000) and late follow-up (Dawe, Rees, Mattick, Sitharthan, & Heather, 2002; Thornton, Gottheil, Patkar, & Weinstein, 2003) studies provided effect estimates prior to 6 and 12 months, respectively. This underscores the nature of findings in the present study as maintenance of CBT effects at follow-up, rather than initial efficacy at post-treatment. Studies using a no treatment or a minimal treatment contrast provide the optimal conditions for examining the durability of treatment effect. In these cases, studies reporting frequency outcomes demonstrated that CBT effects were quite durable with moderate effects at both early (k = 5) and late (k = 4) follow-ups. The cognitive-behavioral emphasis on relapse prevention suggests this is a treatment well-suited to abstinence maintenance and long-term functioning. When the contrast condition was a non-specific or specific therapy, then relative durability in contrast to another form of treatment is the effect measure. This relative durability was not demonstrated in the present review.

Perhaps the most important message of this meta-analysis, in concert with others in the literature, is that contrast condition matters when intervention effect magnitude is of interest (e.g., Wampold, 1997; Wampold, Minami, Baskin, & Tierney, 2002). We suggest that future meta-analyses label effect sizes for exactly what they are, that is, effect sizes in contrast to no treatment, assessment only, or other minimal treatment versus effect sizes in relation to another form of treatment. In the present study, estimates of effect were sizable only among the seven studies contrasting CBT with a minimal comparison. When non-specific therapies or usual care were the contrast, the pooled effect size was small to non-significant. In this review, non-specific contrasts were typically either treatment as usual (e.g., Bowen et al., 2014; McKay et al., 2010; Morgenstern, Blanchard, Morgan, Labouvie, & Havaki, 2001; Papas et al., 2011) or conditions designed to account for non-specific therapy factors (e.g., supportive therapy [Burtscheidt, Wölwer, Schwarz, Strauss, & Gaebel, 2002]; didactic education [Kivlahan et al., 1990]). Modest relative efficacy in contrast to these conditions underscores how little we know about the specificity of CBT ingredients when delivered to populations with alcohol or other drug use disorders. A view of Supplemental Table 1 supports this point where non-specific contrasts were quite variable, but often involved addiction information, mutual support, and 12-step program involvement. These are established elements of community-based care and confer benefit in their own right (SAMHSA, 2017).

Non-significant pooled effects, in contrast to a specific therapy, across outcome types and follow-up time point was observed in the present study. As noted above, this type of contrast characterized the majority of studies reviewed despite the known phenomenon of limited evidence for differential efficacy between specific therapies (i.e., the dodo bird effect). While it is beyond the scope of this work, an important question for future research is - how or why this phenomenon continues to occur? A range of explanations have been offered including common factors and specific, yet equally effective, factors (e.g., Magill, Kiluk, McCrady, Tonigan, & Longabaugh, 2015), and it could be a combination of both. Such questions are complex, but highly significant for future clinical training, intervention refinement, and community program implementation.

Limitations

The limitations of this study may reflect some of the key trade-offs in meta-analysis. Specifically, our primary goal was to derive valid, random effects estimates characterized by effect modifiers. In other words, the study sought to avoid combining “apples and oranges” (Wilson, 2000). The trade-off was that some effect estimates were comprised of a small number of primary studies, which could result in underpowered moderator analysis if heterogeneity was present in these pooled effects. In this study, two of 10 subgroup effect sizes showed greater than 40% systematics heterogeneity, and one of these two subgroups had a sufficient number of studies to allow multivariate moderator analysis. CBT frequency outcomes at early follow-up, in contrast to a non-specific therapy, showed smaller effect sizes among studies with older samples. In summary, the derived effect sizes showed minimal heterogeneity, and when heterogeneity was observed, moderator analyses revealed few significant moderating factors possibly due to low statistical power.

Additional limitations are perhaps more conceptual than statistical, but nevertheless reflect potential challenges to the validity of meta-analytic studies of intervention efficacy. The first concerns fidelity and other sources of variability in what comprised the sample of CBT interventions. As noted, we sought homogeneity in how CBT was defined via inclusion of face-to-face CBT not combined with another intervention, whether psychosocial or pharmacological. However, reporting of therapist training (44%), supervision frequency and/or methods (70%), and fidelity (7%) was variable in the sample of studies. As such, the quality of CBT-delivery cannot be assured. Second, study results should be considered in the context of the ongoing debate about what constitutes an optimal outcome in randomized clinical trials with substance use disorders. We selected consumption measures, and favored biological assay variables, but equally meaningful are use consequences and improvements in overall functioning (Kiluk, Fitzmaurice, Strain, & Weiss, 2019). Further, optimal outcomes could vary as a function of intervention modality, including specific ingredients and purported mechanisms of action (Donovan et al., 2012). Therefore, the degree to which the outcomes presented in this review reflect an ideal endpoint or merely one kind of endpoint for measurement of CBT efficacy should be considered.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this meta-analysis shows CBT efficacy, in contrast to no or minimal treatment, was moderate and durable over follow-up. Consistent with a number of evidence-based addictions therapies, CBT effect sizes were small to non-significant in contrast to non-specific and specific therapies, respectively. The majority of derived effects were homogeneous, suggesting that the selected subgroup variables (i.e., contrast type, outcome type, and follow-up time point) were informative modifiers of CBT effects5.

Supplementary Material

Public Health Significance:

This meta-analysis provides an up-to-date summary of treatment efficacy in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for alcohol or other drug use disorders. CBT is effective for these conditions with outcomes roughly 15–26% better than average outcomes in untreated, or minimally treated, controls.

Acknowledgement:

This research is supported by #AA026006, awarded to Molly Magill.

Footnotes

Effect size magnitude was interpreted using the following benchmarks: 0.2 “small”, 0.5 “medium”, and 0.8 “large” (Cohen, 1988). However, these are generic guidelines and should be considered conservative in the absence of empirically-based effect size distributions for adult SUD/AUD samples. For example, Tanner-Smith, Durlak, & Marx (2018) suggest that effect size magnitudes of 0.05, 0.10, and 0.15 approximate the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles (respectively) for behavioral outcomes in youth drug prevention.

I2 magnitude can be interpreted using the following benchmarks: 0 – 40% “might not be important”, 30 – 60% “may represent moderate heterogeneity”, 50 – 90% “may represent substantial heterogeneity”, 75 – 100% “considerable heterogeneity” (Higgins & Green, 2011).

An influential study was defined as any study that, if removed, would change the statistical significance of the pooled effect estimate.

For heterogeneous effects of CBT on early follow-up use frequency in contrast to minimal treatment, the sample of primary studies was k = 4.

Please see Supplemental Information for PRISMA Checklist.

References

References marked with an asterisk (*) are included in the meta-analysis

- American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed., test rev.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Baujat B, Mahé C, Pignon JP, & Hill C (2002). A graphical method for exploring heterogeneity in meta-analyses: application to a meta-analysis of 65 trials. Statistics in Medicine, 21(18), 2641–2652. 10.1002/sim.1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg CB, & Mazumdar M (1994). Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics, 1088–1101. 10.2307/2533446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertholet N, Daeppen JB, Wietlisbach V, Fleming M, & Burnand B (2005). Reduction of alcohol consumption by brief alcohol intervention in primary care: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165(9), 986–995. 10.1001/archinte.165.9.986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, & Rothstein H (2015). Regression in meta-analysis. Retrieved from https://www.meta-analysis.com/downloads/MRManual.pdf

- *.Bowen S, Witkiewitz K, Clifasefi SL, Grow J, Chawla N, Hsu SH, Carroll HA, Harrop E, Collins SE, Lustyk MK, & Larimer ME (2014). Relative efficacy of mindfulness-based relapse prevention, standard relapse prevention, and treatment as usual for substance use disorders: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(5), 547–556. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Brown TG, Seraganian P, Tremblay J, & Annis H (2002). Matching substance abuse aftercare treatments to client characteristics. Addictive Behaviors, 27(4), 585–604. 10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00195-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Budney AJ, Moore BA, Rocha HL, & Higgins ST (2006). Clinical trial of abstinence-based vouchers and cognitive-behavioral therapy for cannabis dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(2), 307–316. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Burtscheidt W, Wölwer W, Schwarz R, Strauss W, & Gaebel W (2002). Out-patient behaviour therapy in alcoholism: Treatment outcome after 2 years. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 106(3), 227–232. 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02332.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, & Beck AT (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(1), 17–31. 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM (1996). Relapse prevention as a psychosocial treatment: A review of controlled clinical trials. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 4(1), 46–54. 10.1037/1064-1297.4.1.46 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM (1998). A cognitive behavioral approach: Treating cocaine addiction. NIH Publication Number: 984308. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, & Kiluk BD (2017). Cognitive behavioral interventions for alcohol and drug use disorders: Through the stage model and back again. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(8), 847–861. 10.1037/adb0000311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, & Onken LS (2005). Behavioral therapies for drug abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(8), 1452–1460. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, & Gawin FH (1991). A comparative trial of psychotherapies for ambulatory cocaine abusers: relapse prevention and interpersonal psychotherapy. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 17(3), 229–247. 10.3109/00952999109027549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Dawe S, Rees VW, Mattick R, Sitharthan T, & Heather N (2002). Efficacy of moderation-oriented cue exposure for problem drinkers: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(4), 1045–1050. 10.1037/0022-006X.70.4.1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM, Bigelow GE, Brigham GS, Carroll KM, Cohen AJ, Gardin JG, … & Marlatt GA (2012). Primary outcome indices in illicit drug dependence treatment research: Systematic approach to selection and measurement of drug use end points in clinical trials. Addiction, 107(4), 694–708. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03473.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Donovan DM, & Ito JR (1988). Cognitive behavioral relapse prevention strategies and aftercare in alcoholism rehabilitation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 2(2), 74–81. 10.1037/h0080521 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, & Otto MW (2008). A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(2), 179–187. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, & Minder C (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein EE, & McCrady BS (2009). A cognitive-behavioral treatment program for overcoming alcohol problems: Therapist guide. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton CA, Kim M, Thomas CP, Lyman DR, Montejano LB, Dougherty RH, … & Delphin-Rittmon ME (2014). Medication-assisted treatment with methadone: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services, 65(2), 146–157. 10.1176/appi.ps.201300235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Heather N, Brodie J, Wale S, Wilkinson G, Luce A, Webb E, & McCarthy S (2000). A randomized controlled trial of Moderation-Oriented Cue Exposure. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 61(4), 561–570. 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV (1994). Statistical considerations In Cooper H & Hedges LV. (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis (pp. 29–38), New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV, & Olkin I (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV, & Vevea JL (1998). Fixed-and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 486–504. 10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, … & Sterne JA (2011). The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 343, d5928 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJ, Sawyer AT, & Fang A (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36(5), 427–440. 10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imel ZE, Wampold BE, Miller SD, & Fleming RR (2008). Distinctions without a difference: direct comparisons of psychotherapies for alcohol use disorders. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 22(4), 533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin JE, Bowers CA, Dunn ME, & Wang MC (1999). Efficacy of relapse prevention: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(4), 563–570. 10.1037/0022-006X.67.4.563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Jones SL, Kanfer R, & Lanyon RI (1982). Skill training with alcoholics: A clinical extension. Addictive Behaviors, 7(3), 285–290. 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90057-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadden RM, Carroll K, Donovan D, Cooney N, Monti P, Abrams D, Litt M & Hester R (Eds.) (1992). Cognitive-Behavioral Coping Skills Therapy Manual: A Clinical Research Guide for Therapists Treating Individuals with Alcohol Abuse and Dependence. Volume 4, Project MATCH Monograph Series. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; (DHHS Publication No. (ADM)92–1895). [Google Scholar]

- *.Kadden RM, Cooney NL, Getter H, & Litt MD (1989). Matching alcoholics to coping skills or interactional therapies: Posttreatment results. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57(6), 698–704. 10.1037/0022-006X.57.6.698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kadden RM, Litt MD, Cooney NL, Kabela E, & Getter H (2001). Prospective matching of alcoholic clients to cognitive-behavioral or interactional group therapy. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 62(3), 359–369. 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Källmén H, Sjöberg L, & Wennberg P (2003). The effect of coping skills training on alcohol consumption in heavy social drinking. Substance Use & Misuse, 38(7), 895–903. 10.1081/JA-120017616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Fitzmaurice GM, Strain EC, & Weiss RD (2019). What Defines a Clinically Meaningful Outcome in the Treatment of Substance Use Disorders: Reductions in Direct Consequences of Drug Use or Improvement in Overall Functioning?. Addiction, 114(1), 9–15. 10.1111/add.14289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA, Fromme K, Coppel DB, & Williams E (1990). Secondary prevention with college drinkers: Evaluation of an alcohol skills training program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 58(6), 805–810. 10.1037/0022-006X.58.6.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Lanza PV, Garcia PF, Lamelas FR, & González-Menéndez A (2014). Acceptance and commitment therapy versus cognitive behavioral therapy in the treatment of substance use disorder with incarcerated women. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(7), 644–657. 10.1002/jclp.22060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, & Wilson DB (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- *.Litt MD, Kadden RM, Tennen H, & Kabela-Cormier E (2016). Network Support II: Randomized controlled trial of Network Support treatment and cognitive behavioral therapy for alcohol use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 165, 203–212. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, & Morgenstern J (1999). Cognitive-behavioral coping-skills therapy for alcohol dependence: Current status and future directions. Alcohol Research &Health, 23(2), 78–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, & Burke BL (2010). A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty-five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice, 20(2), 137–160. 10.1177/1049731509347850 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, & Ray LA (2009). Cognitive-behavioral treatment with adult alcohol and illicit drug users: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70(4), 516–527. 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Wilbourne PL, Humphreys K, & Finney JW (2013). Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: When are these medications most helpful?. Addiction, 108(2), 275–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, & Gordon JR (Eds.). (1985). Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mastroleo NR, & Monti PM (2013). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for addictions In McCrady BS & Epstein EE (Eds.), Addictions: A comprehensive guidebook (pp. 391–410). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- *.Maude-Griffin PM, Hohenstein JM, Humfleet GL, Reilly PM, Tusel DJ, & Hall SM (1998). Superior efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for urban crack cocaine abusers: Main and matching effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(5), 832–837. 10.1037/0022-006X.66.5.832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.McAuliffe WE (1990). A randomized controlled trial of recovery training and self-help for opioid addicts in New England and Hong Kong. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 22(2), 197–209. 10.1080/02791072.1990.10472544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Hearon BA, & Otto MW (2010). Cognitive behavioral therapy for substance use disorders. Psychiatric Clinics, 33(3), 511–525. 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.McKay JR, Alterman AI, Cacciola JS, Rutherford MJ, O’Brien CP, & Koppenhaver J (1997). Group counseling versus individualized relapse prevention aftercare following intensive outpatient treatment for cocaine dependence: Initial results. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65(5), 778–788. 10.1037/0022-006X.65.5.778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.McKay JR, Lynch KG, Coviello D, Morrison R, Cary MS, Skalina L, & Plebani J (2010). Randomized trial of continuing care enhancements for cocaine-dependent patients following initial engagement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(1), 111–120. 10.1037/a0018139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.McKay JR, Lynch KG, Shepard DS, Ratichek S, Morrison R, Koppenhaver J, & Pettinati HM (2004). The effectiveness of telephone-based continuing care in the clinical management of alcohol and cocaine use disorders: 12-month outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(6), 967–979. 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, & O’Brien CP (1980). An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: The Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 168(1), 26–33. 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Wilbourne PL, & Hettema JE (2003). What works? A summary of alcohol treatment outcome research. summary of alcohol treatment outcome research In Hester RK & Miller WR (Eds.), Handbook of alcohol treatment approaches: Effective alternatives (3rd ed., pp. 13–63). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, & Stroup DF (1999). Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: The QUORUM statement. Lancet, 354, 1896–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti PM, Abrams DB, Kadden RM, & Cooney NL (1989). Treating Alcohol Dependence: A Coping Skills Training Guide. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- *.Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Michalec E, Martin RA, & Abrams DB (1997). Brief coping skills treatment for cocaine abuse: Substance use outcomes at three months. Addiction, 92(12), 1717–1728. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1997.tb02892.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Morgenstern J, Blanchard KA, Morgan TJ, Labouvie E, & Hayaki J (2001). Testing the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral treatment for substance abuse in a community setting: within treatment and posttreatment findings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(6), 1007–1017. 10.1037/0022-006X.69.6.1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Papas RK, Sidle JE, Gakinya BN, Baliddawa JB, Martino S, Mwaniki MM, … Maisto SA (2011). Treatment outcomes of a stage 1 cognitive-behavioral trial to reduce alcohol use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected out-patients in western Kenya. Addiction, 106(12), 2156–2166. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03518.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigott TD (1994). Methods for handling missing data in research synthesis In Cooper H & Hedges LV (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis (pp. 163–175). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast ML, Podus D, Chang E, & Urada D (2002). The effectiveness of drug abuse treatment: A meta-analysis of comparison group studies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 67(1), 53–72. 10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00014-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Project MATCH Research Group. (1997) Matching Alcoholism Treatments to Client Heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 58(1), 7–29. 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Sandahl C, Gerge A, & Herlitz K (2004). Does treatment focus on self-efficacy result in better coping? Paradoxical findings from psychodynamic and cognitive-behavioral group treatment of moderately alcohol-dependent patients. Psychotherapy Research, 14(3), 388–397. 10.1093/ptr/kph032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De la Fuente JR, & Grant M (1993). Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Shakeshaft AP, Bowman JA, Burrows S, Doran CM, & Sanson-Fisher RW (2002). Community-based alcohol counselling: A randomized clinical trial. Addiction, 97(11), 1449–1463. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00199.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Sitharthan T, Sitharthan G, Hough MJ, & Kavanagh DJ (1997). Cue exposure in moderation drinking: A comparison with cognitive-behavior therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65(5), 878–882. 10.1037/0022-006X.65.5.878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Smout MF, Longo M, Harrison S, Minniti R, Wickes W, & White JM (2010). Psychosocial treatment for methamphetamine use disorders: A preliminary randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy. Substance Abuse, 31(2), 98–107. 10.1080/08897071003641578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Stephens RS, Roffman RA, & Curtin L (2000). Comparison of extended versus brief treatments for marijuana use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 898–908. 10.1037/0022-006X.68.5.898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Stephens RS, Roffman RA, & Simpson EE (1994). Treating adult marijuana dependence: A test of the relapse prevention model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62(1), 92–99. 10.1037/0022-006X.62.1.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streeton C, & Whelan G (2001). Naltrexone, a relapse prevention maintenance treatment of alcohol dependence: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 36(6), 544–552. 10.1093/alcalc/36.6.544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). The national survey of substance abuse treatment services (N-SSATS). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2017). Addiction Counseling Competencies (TAP-21). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner-Smith EE, Durlak JA, & Marx RA (2018). Empirically based mean effect size distributions for universal prevention programs targeting school-aged youth: a review of meta-analyses. Prevention Science, 19(8), 1091–1101. 10.1007/s11121-018-0942-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *.Thornton C, Gottheil E, Patkar A, & Weinstein S (2003). Coping styles and response to high versus low-structure individual counseling for substance abuse. American Journal on Addictions, 12(1), 29–42. 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2003.tb00537.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace BC, Small K, Brodley CE, Lau J, & Trikalinos TA (2012). Deploying an interactive machine learning system in an evidence-based practice center: abstrackr In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGHIT International Health Informatics Symposium (pp. 819–824). New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE (1997). Methodological problems in identifying efficacious psychotherapies. Psychotherapy Research, 7(1), 21–43. 10.1080/10503309712331331853 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE (2001). The great psychotherapy debate: Models, methods, and findings. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE, & Imel ZE (2015). The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE, Minami T, Baskin TW, & Tierney SC (2002). A meta-(re) analysis of the effects of cognitive therapy versus ‘other therapies’ for depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 68(2–3), 159–165. 10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00287-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE, Mondin GW, Moody M, Stich F, Benson K, & Ahn HN (1997). A meta-analysis of outcome studies comparing bona fide psychotherapies: Empirically, “all must have prizes.” Psychological Bulletin, 122(3), 203–215. 10.1037/0033-2909.122.3.203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DB (2000). Meta analyses in alcohol and other drug abuse treatment research. Addiction, 95(11s3), 419–438. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.95.11s3.9.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DB (2005). Macros for SPSS/Win Version 6.1 or Higher (Version 2005.05.23). Retrieved from http://mason.gmu.edu/~dwilsonb/ma.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.