INTRODUCTION

Histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) is a member of the Class IIb histone deacetylases (HDAC)[38]. HDAC6 has little or no deacetylase activity towards histones, but mainly targets cytosolic proteins such as α-tubulin[3;16;21]. HDAC6 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases as well as cancer [23;37;38]. In neurodegenerative diseases, increased HDAC6 activity is associated with impaired axonal transport of mitochondria, which contributes to disease pathogenesis[6;9;12;15;19;20;30;45;51;60]. In the context of cancer, upregulation of HDAC6 is associated with tumor growth and metastasis formation[37]. Efficacy of HDAC6 inhibitors as add-on cancer treatment has been reported in both preclinical models and clinical trials[7;39;58;62;66].

There is growing interests in targeting HDAC6 for mitigating neurotoxic side effects of cancer treatment, including chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) which affects over 60% of this patient group[32;41;52;61]. Common symptoms of CIPN include allodynia, persistent pain, tingling, and numbness[1;42;47]. The loss of intraepidermal nerve fibers (IENFs) is commonly used for clinical diagnosis of CIPN[25]. CIPN reduces patients’ quality of life and because it can lead to chemotherapy dose reduction it also impacts the efficacy of cancer treatment[1;42;47]. Despite the high prevalence and severe impact, there are no FDA-approved medications for its prevention or management[10].

Neuronal mitochondrial dysfunction and bioenergetic deficits have been proposed as critical contributors to CIPN[5;42]. Deficient energy supply in sensory neurons may reduce ion pump activity, resulting in spontaneous discharges in sensory afferents and the experience of pain[5;64]. Additionally, localized energy deficiency at nerve terminals due to mitochondrial dysfunction and defective axonal mitochondrial transport causes axonal degeneration and the loss of IENFs[5;32]. In support of a fundamental role of mitochondrial dysregulation, agents that target mitochondrial deficits have been shown to prevent the development of CIPN[26;33;44;64;70].

We have shown that pharmacological inhibition of HDAC6 administered after completion of chemotherapy reverses cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia, ongoing pain, sensory loss and loss of IENFs[32]. These effects were associated with improved mitochondrial function[32]. Co-administration of HDAC6 inhibitors with chemotherapy prevented development of CIPN in response to paclitaxel or vincristine[32;61]. However, the underlying mechanism via which HDAC6 contributes to CIPN remains unclear.

HDAC6 is expressed in multiple cell types, including sensory neurons, glial cells and immune cells, all of which contribute to CIPN[8;36;42;68]. Because of the contribution of sensory neuron mitochondrial deficits to CIPN, we hypothesized that HDAC6 activity in sensory neurons is key to the development of CIPN. We tested this hypothesis by examining the effect of pharmacological inhibition of HDAC6 and of global and cell-specific genetic deletion of HDAC6 in a mouse model of cisplatin-induced neuropathy. We show that HDAC6 global deletion prevents all CIPN signs. Strikingly, deletion of HDAC6 in advillin-positive sensory neurons alone prevented cisplatin-induced IENF loss, but only partially and transiently prevented cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia. We also identify a key role of T cells in the preventive effect of HDAC6 inhibition on mechanical allodynia, while T cells are not involved in prevention of IENF loss. Our findings reveal the cell-specific contribution of HDAC6 to the establishment of two key aspects of CIPN, i.e. mechanical allodynia and the loss of IENFs.

MATERALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male and female WT C57BL/6J mice and Rag2 KO mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice with global deletion of HDAC6 and HDAC6-floxed (HDAC6-fl) mice were kindly provided by Dr. Patrick Matthias (Friedrich Miescher Institute for Biomedical Research, Basel, Switzerland)[68], and bred in house. Mice with sensory neuron specific deletion of HDAC6 were generated by cross breeding Advillin-Cre+/− mice with HDAC6-fl mice. All animals were housed at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center animal facility (Houston, TX) on a regular 12-hour light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. All experiments started when the mice were 8 – 10 weeks of age. All experimental procedures were consistent with the National Institute of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the Ethical Issues of the International Association for the Study of Pain[71] and were approved by the Institution for Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Experiments were performed and reported in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines[29].

Drug administration

Cisplatin (TEVA Pharmaceuticals, North Wales, PA) was diluted in sterile PBS and administered i.p. at a dose of 2.3 mg/kg per day for 5 days followed by 5 days of rest and another 5 days of injections[46]. The HDAC6 inhibitor ACY-1215 (Regenacy Pharmaceuticals) was prepared in 10% DMSO, 30% Propylene glycol and 60% Poly(ethylene glycol)-300, and was administered daily via oral gavage at 30 mg/kg 1 hour prior to each cisplatin injection[32].

Von Frey test

Mechanical allodynia was measured using the von Frey up and down methods with von Frey hairs (0.02, 0.07, 0.16, 0.4, 0.6, 1.0, and 1.4 g) (Stoelting, Wood Dale, Illinois, USA) as described previously[11;32]. Testing was done by an individual blinded to treatment groups during the full course of the experiment and analysis.

RNA Sequencing

Whole-genome RNA sequencing was used to identify transcriptional changes induced by cisplatin in the DRG. Total RNA was isolated 2 weeks after the completion of cisplatin treatment with the RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Libraries were prepared with the Stranded mRNA-Seq kit (Kapa Biosystems, Wilmington, MA) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Stranded-mRNA seq was performed with a HiSeq4000 Sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA) with 76nt PE format by the RNA Sequencing Core at MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Data analysis was performed as previously described[13]. Briefly, expression data of 4 samples per group were analyzed in R using bioconductor packages. STAR was used for alignment of paired-end reads to the mm10 version of the mouse reference genome, featureCounts was used to assign mapped sequence reads to genomic features, and DESeq2 was used to identify differentially expressed genes (padj<0.05). Qualify check of raw and aligned reads was performed with FastQC and Qualimap. Next, we used Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA;Qiagen Inc., https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/ingenuity-pathway-analysis/) for analysis of the canonical pathways implicated by cisplatin-induced transcriptome changes in DRG.

Quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

Quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was used to measure mRNA levels. Total RNA was isolated 2 weeks after the completion of cisplatin treatment with the RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was prepared with the high-capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (ThermoFisher, Waltham, USA). Quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed with TaqMan Real-Time PCR Master Mix (ThermoFisher) and PrimeTime qPCR Taqman probes for hdac6 and gapdh (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coraville, IA, USA) using the CFX Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Relative mRNA levels were calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method and normalized to gapdh in the same sample. Amplifications without template were included as negative control.

Western blotting

Tissue lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 2 mM Na3VO4, 50 mM NaF) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX). Protein content was assessed using Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Equivalent amounts of protein were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF membranes (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% milk, and were then subjected to incubation of primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for 2 hours. The following primary and secondary antibodies were used in the study: HDAC6 (SC-5258, 1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), acetlylated lysine (ab190479, 1:2000, Abcam), β-Actin (A3854, 1:50,000, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), α-Tubulin (2144S, 1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit (111–035-144, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), anti-goat (111–035-144, Jackson ImmunoResearch). For detection of signal, enhanced chemiluminescent agent (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) or Clarity Western ECL Substrate (BioRad) was used followed by imaging on LAS4000 chemiluminescence system. Band density was determined using Image J software (NIH).

Immunohistochemistry

Biopsies from the glabrous skin of the hind paws were collected and processed for quantification of IENFs as described previously[32]. Frozen sections (25 μm) were incubated with rabbit anti-PGP9.5 (ab108986, 1:500, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) and goat anti-Collagen IV antibodies (1340–01, 1:100, Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) followed by Alexa-594 donkey anti-rabbit and Alexa-488 donkey anti-goat secondary antibodies (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). A Leica SPE confocal microscope was used to capture images (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). IENF density was determined as the total number of PGP9.5 stained nerve fibers that crossed the collagen-stained dermal-epidermal junction/length of epidermis (IENFs/mm). 4–5 mice from each group were measured, with 5 random pictures quantified from each mouse for individual IENF counts.

Mitochondrial bioenergetics analysis

Mitochondrial bioenergetics were measured with the XF24 Flux Analyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc, Santa Clara, CA) as previously described[32;40]. For measurement of axonal mitochondrial bioenergetics, 10 mm sections of tibial nerves were freshly isolated and placed into the islet capture XF24 microplate (Seahorse Bioscience, North Billerica, MA) in XF media supplemented with 5 mM glucose, 0.5 mM sodium pyruvate, and 1 mM glutamine[32]. Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were measured and normalized to total protein contents of each individual nerve, and were used as indicators of mitochondrial bioenergetic status.

DRG neurons were isolated as described previously[40;43] and plated in XF24 microplate and cultured overnight in Ham’s F-10 media (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) supplemented with N2 supplement (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). On the day of assay, media was changed to XF media supplemented with 5 mM glucose, 0.5 mM sodium pyruvate, and 1 mM glutamine for OCR measurement. Carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP;4 μM) and Rotenone and Antimycin A (2 μM each) (Sigma-Aldrich) were used to determine mitochondrial respiratory properties. The results were normalized to the protein contents of each well.

Citrate synthase activity assay

Citrate synthase activity as an indicator of mitochondrial content in the tibial nerves and DRGs was measured using the Citrate synthase activity assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich). Tissues were homogenized in 100 μL of assay buffer provided in the assay kit and incubated on ice for 30 min. Samples were then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min. Supernatants were collected for subsequent measurement of citrate synthase activity according to manufacturer’s protocol. Bradford protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was used to determine the protein concentration of the samples. Citrate synthase activity of each sample was then normalized to the protein contents used for the assay.

T cell adoptive transfer

T cells were isolated from spleens collected from CO2-asphyxiated mice as described previously[31]. Briefly, single cell suspensions were prepared by passing spleens from WT or HDAC6 KO mice in PBS plus 0.1% bovine serum albumin through a 70 μm mesh filter. T-cell were isolated using the Pan CD3+ T-cell negative selection kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). One week before initiation of cisplatin administration, CD3+ T cells (8 × 106 per mouse) or PBS were injected intravenously into the tail vein of Rag2 KO mice in a volume of 100 μl.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis of the differences between groups was performed using student’s t test, one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc analysis (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) as appropriate;P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Transcriptome changes induced by cisplatin in the dorsal root ganglion

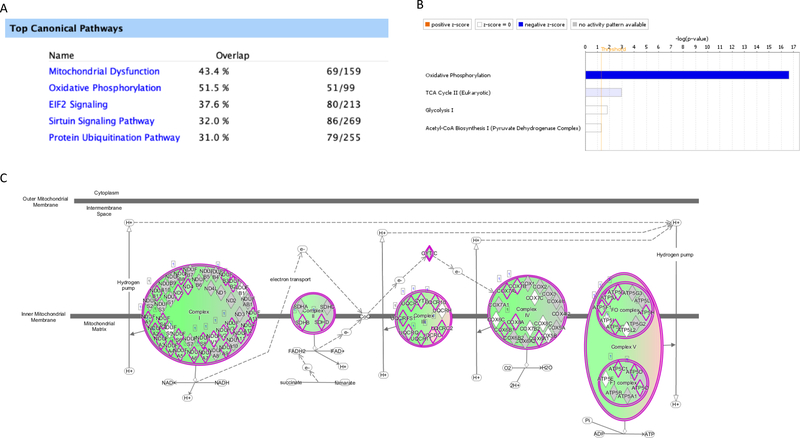

To identify the pathogenic pathways that contribute to cisplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy, we performed RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) analysis on DRGs from mice treated with 2 cycles of cisplatin. We have shown previously that this treatment schedule of cisplatin induces profound neuropathy in mice[32;44;46]. 2930 genes were identified to be differentially expressed in the cisplatin group versus the PBS group, among which 1538 genes were up-regulated and 1392 gene were down-regulated (padj<0.05). Ingenuity Pathway Analysis identified “Mitochondrial dysfunction” and “Oxidative phosphorylation” among the top 5 canonical pathways affected by cisplatin (Figure 1A). We therefore examined cisplatin-induced changes in pathways involved in the generation of precursor metabolites and energy. Interestingly, cisplatin seems to specifically inhibit oxidative phosphorylation without having overt impact on glycolysis or the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (Figure 1B). As shown in Figure 1C, cisplatin treatment decreased the transcripts of major components of the mitochondrial electron transport chain. These findings from unbiased expression profiling are well in line with previous data reporting functional and morphological changes in mitochondria in DRG and nerve induced by cisplatin[32;44] and other chemotherapeutics[26;33;63;69]. Taken together, these data support an essential role of mitochondrial dysfunction and the associated bioenergetic deficits in the pathogenesis of CIPN.

Figure 1. Effects of cisplatin on mitochondrial transcriptome in DRG.

Cisplatin (2.3 mg/kg) or PBS was administered i.p. once a day for two 5-day treatment cycles with 5 days of rest in between. Lumbar DRG were collected after completion of treatment for RNA sequencing analysis. (A) Top canonical pathways induced by cisplatin treatment. (B) Cisplatin-induced changes in pathways involved in the generation of precursor metabolites and energy. (C) Cisplatin-induced transcriptome changes in the major components of the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Green, downregulation; red, upregulation.

The effect of HDAC6 inhibition on cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia and mitochondrial dysfunction in DRG neurons

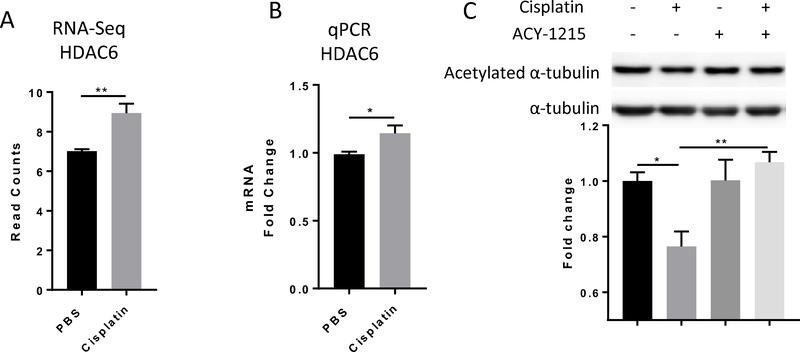

Our RNA-Seq dataset showed a small but significant increase of HDAC6 transcripts in DRG of mice treated with cisplatin (Figure 2A), and this was confirmed by qPCR analysis (Figure 2B). Consistent with the increase in HDAC6 expression, 2 cycles of cisplatin treatment reduced acetylation of the HDAC6 substrate α-tubulin in the DRG (Figure 2C). Co-administration of ACY-1215, an HDAC6 inhibitor that’s currently under clinical trials for its efficacy as add-on cancer treatment[7;39;58;62;66], prevented this cisplatin-induced α-tubulin deacetylation in the DRG (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Effects of cisplatin on HDAC6 expression and the deacetylation of the HDAC6 substrate α-tubulin.

(A) RNA sequencing analysis indicates that cisplatin induced HDAC6 expression change in the DRG. (B) The upregulation of HDAC6 by cisplatin was validated by real-time qPCR analysis (n = 5, student’s t test). (C) ACY-1215 (30mg/kg) or vehicle was given 1 hour prior to each cisplatin or PBS dosing for two 5-day treatment cycles. Following completion of the last dose of cisplatin, lumbar DRG were collected for western blot analysis of acetylation of α-tubulin (n = 4, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis). Results are expressed as means ± SEM;*p<0.05, **p<0.01.

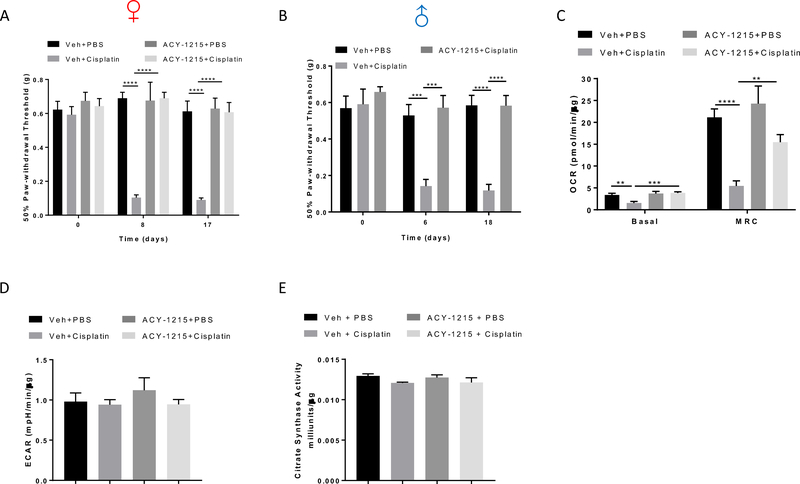

To determine the effect of co-administration of the HDAC6 inhibitor ACY-1215 on CIPN, we assessed mechanical sensitivity using von Frey hairs at baseline and after completion of the first and second cycle of cisplatin treatment. Cisplatin treatment induced similar levels of mechanical allodynia in female and male mice (Figure 3A and B). Co-administration of the HDAC6 inhibitor ACY-1215 with cisplatin prevented cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia in both female (Figure 3A) and male mice (Figure 3B). ACY-1215 alone did not have any impact on mechanical sensitivity in either female (Figure 3A) or male mice[32].

Figure 3. Effects of the HDAC6 inhibitor ACY-1215 on cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia and DRG mitochondrial dysfunction.

ACY-1215 (30mg/kg) or vehicle was given 1 hour prior to each cisplatin or PBS dosing for two 5-day treatment cycles and sensitivity to mechanical stimulation of the hind paws was monitored over time using the von Frey test. Mechanical sensitivity was measured on day 6 or 8 after start of cisplatin treatment (1–3 days after completion of the first round of dosing) and day 17 after start of cisplatin treatment (2 days after completion of the second round of dosing). Co-administration of ACY-1215 prevented cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia in (A) female and (B) male mice (n = 8, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis). Lumbar DRG neurons were isolated following completion of behavioral testing for mitochondrial bioenergetic analysis. Changes induced by cisplatin and ACY-1215 in (C) basal OCR and MRC and (D) basal ECAR in the DRG neurons (n = 8–10, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis). (E) Changes induced by cisplatin and ACY-1215 in citrate synthase activity in the DRG (n = 4, two-way ANOVA). Results are expressed as means ± SEM;**p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Examination of the effect of cisplatin and the HDAC6 inhibitor on mitochondrial bioenergetics in DRG neurons showed that cisplatin treatment significantly decreased the basal oxygen consumption rate (OCR) (Figure 3C). In addition, cisplatin reduced the maximal respiratory capacity (MRC) assessed in response to addition of the mitochondrial uncoupler FCCP (Figure 3C). The basal extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) was not affected (Figure 3D). Importantly, co-administration of ACY-1215 prevented the cisplatin-induced deficits in basal OCR and MRC of DRG neurons (Figure 3C). To determine if the cisplatin-induced changes in mitochondrial bioenergetics are associated with changes in mitochondrial content, we measured citrate synthase activity, a widely used marker for this purpose[34]. We did not detect any effect of cisplatin or HDAC6 inhibition on citrate synthase activity of the DRG (Figure 3E). These data indicate that in the cell bodies of DRG neurons, cisplatin impairs mitochondrial bioenergetics by compromising mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation without affecting mitochondrial content. In addition, HDAC6 plays an essential role in this process, as inhibition of HDAC6 prevented the development of these deficits.

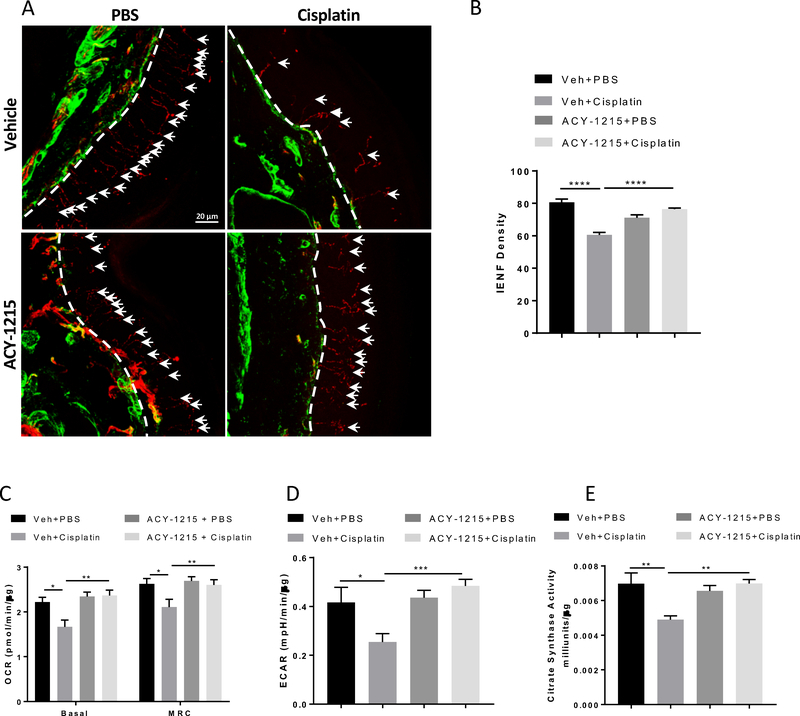

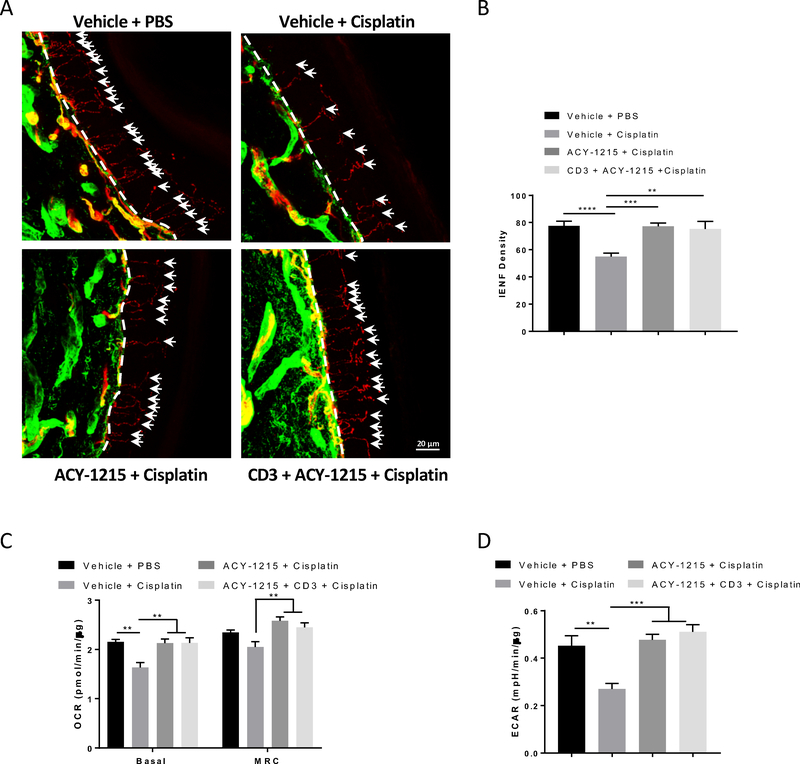

The effect of HDAC6 inhibition on cisplatin-induced loss of intra-epidermal nerve fibers and bioenergetic deficits in the peripheral nerves

Cisplatin treatment reduces IENF density in the plantar surface of mouse hind paws[32;46]. The results in Figure 4A and B show that co-administration of the HDAC6 inhibitor ACY-1215 prevented the cisplatin-induced IENF loss. ACY-1215 alone did not affect IENF density.

Figure 4. Effects of the HDAC6 inhibitor ACY-1215 on cisplatin-induced IENF loss and mitochondrial bioenergetic deficits in the tibial nerves.

Paw biopsies were obtained from the hind paws of mice that received 2 cycles of cisplatin with or without the HDAC6 inhibitor ACY-1215. Tissues were stained with antibodies against PGP9.5 (red) and collagen (green). (A) Representative images from each treatment group, scale bar = 20 mm, magnification × 40. (B) Quantification of IENF density expressed as the number of nerve fibers crossing the basement membrane/length of the basement membrane (mm) (n = 4, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis). Mitochondrial bioenergetics changes induced by cisplatin and ACY-1215 in (C) basal OCR and MRC and (D) basal ECAR in the tibial nerves (n = 7 – 9, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis). (E) Cisplatin and ACY-1215 induced changes in citrate synthase activity (n = 4, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis). Results are expressed as means ± SEM;* p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Chemotherapy-induced IENF loss is thought to be associated with disruption of mitochondrial function in peripheral nerves[5;32]. Indeed, cisplatin significantly decreased basal OCR and MRC in the tibial nerve. These deficits were prevented by co-administration of the HDAC6 inhibitor ACY-1215 (Figure 4C). Interestingly, cisplatin also decreased basal ECAR in the nerves, which was also prevented by ACY-1215 co-administration (Figure 4D). This is in contrast to what we observed in the DRG neurons. In our assay system, changes in extracellular acidification can be largely attributed to respiratory acidification caused by generation of CO2 from the mitochondrial TCA cycle[53]. Therefore, the simultaneous decreases in OCR and ECAR in the tibial nerve in response to cisplatin are likely due to a decrease in axonal mitochondrial content. To test this hypothesis, citrate synthase activity was measured in the tibial nerves. As shown in Figure 4E, cisplatin decreased citrate synthase activity in nerves from WT mice and this was prevented by co-administration of ACY-1215. These results suggest that cisplatin impairs mitochondrial bioenergetics in the tibial nerves through reducing mitochondrial content, and that inhibition of HDAC6 prevents this cisplatin-induced reduction of mitochondrial content in the nerves.

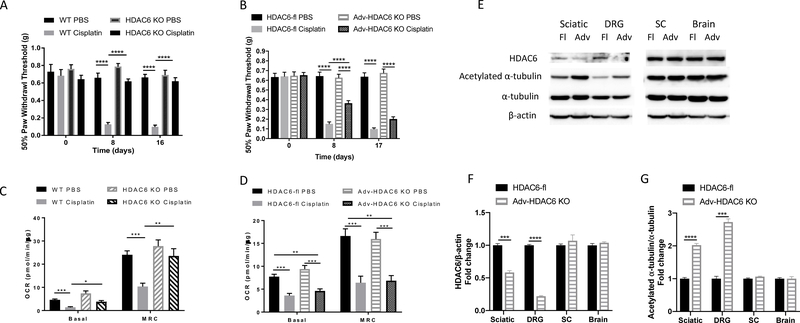

The effect of genetic deletion of HDAC6 on cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia and mitochondrial dysfunction in DRG neurons

To test the hypothesis that HDAC6 in peripheral sensory neurons is critically involved in the development of CIPN, we compared the effects of genetic ablation of HDAC6 in all cells (HDAC6 KO) or only in advillin-positive peripheral sensory neurons (Adv-HDAC6 KO) on CIPN. In line with our pharmacological data using and HDAC6 inhibitor, HDAC6 KO mice were fully protected against the development of mechanical allodynia in response to cisplatin treatment (Figure 5A). Surprisingly, however, cell-specific deletion of HDAC6 in advillin-positive sensory neurons only partially prevented the onset of cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia, and the protective effect was lost after the second round of cisplatin treatment (Figure 5B). At baseline, we did not detect differences in mechanical sensitivity between HDAC6 KO and WT mice or between Adv-HDAC6 KO and HDAC6-fl mice.

Figure 5. Effects of global and cell specific deletion of HDAC6 on cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia and DRG mitochondrial dysfunction.

Mechanical allodynia was measured in cisplatin or PBS-treated mice with (A) global HDAC6 deletion (n = 4 – 9, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis) or (B) sensory neurons specific deletion of HDAC6 (n = 7 – 10, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis). Mechanical sensitivity was measured on day 8 after start of cisplatin treatment (3 days after completion of the first round of dosing) and day 16 or 17 after start of cisplatin treatment (1 or 2 days after completion of the second round of dosing). Mitochondrial bioenergetic analysis of the DRG neurons in (C) HDAC6 KO (n = 5 – 12) and (D) Adv-HDAC6 KO mice (n = 5 – 10, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis). Results are expressed as means ± SEM;* p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. (E) Western blot analysis of HDAC6 and α-tubulin acetylation in the sciatic nerve, DRG, spinal cord and brain of Adv-HDAC6 KO and HDAC6-fl mice. (F) Quantification of HDAC6 in the sciatic nerve, DRG, spinal cord and brain of Adv-HDAC6 KO and HDAC6-fl mice (n = 3, student’s t test). Results are expressed as means ± SEM; ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001. (G) Quantification of acetylated α-tubulin in the sciatic nerve, DRG, spinal cord and brain of Adv-HDAC6 KO and HDAC6-fl mice (n = 3, student’s t test). Results are expressed as means ± SEM; ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Consistent with our findings using the HDAC6 inhibitor ACY-1215, global knockout of HDAC6 prevented cisplatin-induced impairment in mitochondrial bioenergetics in DRG neurons (Figure 5C). In contrast, however, sensory neuron-specific deletion of HDAC6 did not prevent cisplatin-induced deficits in mitochondrial bioenergetics in the DRG neurons. Basal OCR and MRC were reduced by cisplatin to the same extent in Adv-HDAC6 KO mice and their control littermates (Figure 5D). Western blot analysis confirmed successful deletion of HDAC6 in the sensory neurons of Adv-HDAC6 KO mice; HDAC6 protein levels were decreased in DRG and sciatic nerve, and there was no change in HDAC6 protein levels in brain or spinal cord of Adv-HDAC6 KO mice (Figure 5E). Consistently, α-tubulin acetylation was increased in the DRG and sciatic nerve, but not in the spinal cord or brain of Adv-HDAC6 KO mice (Figure 5E).

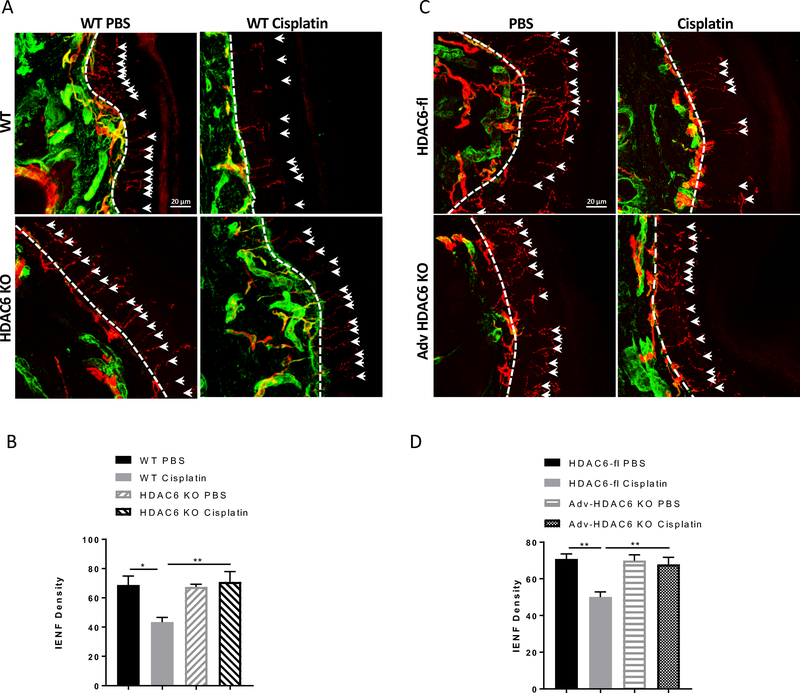

The effect of whole-body deletion and sensory neuron-specific deletion of HDAC6 on cisplatin-induced IENF loss and deficits in axonal transport of mitochondria

Next, we examined the contribution of sensory neuron HDAC6 to cisplatin-induced loss of IENFs. Interestingly, mice with global deletion of HDAC6 and mice with sensory neuron-specific deletion of HDAC6 were both fully protected against the cisplatin-induced reduction of IENF density (Figure 6). In untreated mice, genetic deletion of HDAC6 had no impact on IENF density.

Figure 6. Effects of global and cell specific deletion of HDAC6 on cisplatin-induced IENF loss.

IENF density was measured in cisplatin or PBS-treated mice with (A and B) global HDAC6 deletion (n = 4 – 5, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis) or (C and D) sensory neurons specific deletion of HDAC6 (n = 4 – 5, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis). Paw biopsies were stained with antibodies against PGP9.5 (red) and collagen (green). Scale bar = 20 mm, magnification × 40. Results are expressed as means ± SEM;* p<0.05, **p<0.01.

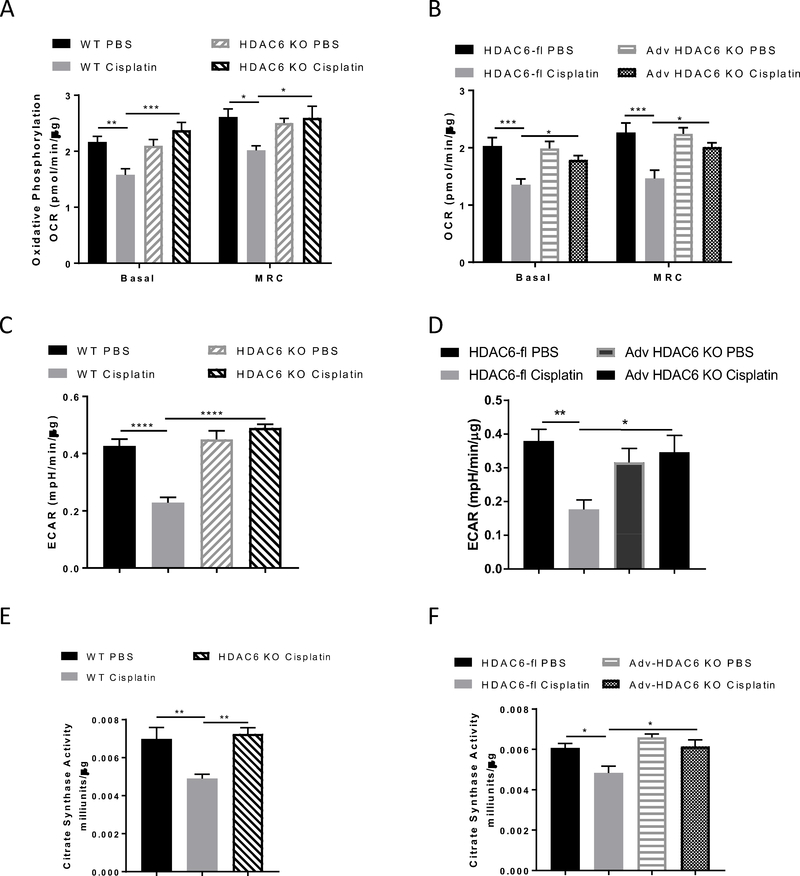

We then measured axonal mitochondrial bioenergetics in the tibial nerves. As shown in Figure 7A–D, both HDAC6 KO mice as well as Adv-HDAC6 KO were protected from the cisplatin-induced decrease in basal OCR, MRC, and basal ECAR. Consistently, results from the citrate synthase activity assay indicate that cisplatin decreased axonal mitochondrial content. The reduction of axonal mitochondrial content was prevented by both global deletion and sensory neuron-specific deletion of HDAC6 (Figure 7E and F).

Figure 7. Effects of genetic modulation of HDAC6 on cisplatin-induced deficits in tibial nerve mitochondrial bioenergetics.

Tibial nerves were collected from cisplatin or PBS-treated mice with global HDAC6 deletion or sensory neuron-specific deletion of HDAC6 for mitochondrial bioenergetic analysis. Cisplatin induced changes in basal OCR and MRC in (A) HDAC6 KO mice (n = 7 – 8, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis) and (B) Adv-HDAC6 KO mice (n = 7 – 9, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis). Cisplatin induced changes in basal ECAR in (C) HDAC6 KO mice (n = 7 – 8, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis) and (D) Adv-HDAC6 KO mice (n = 7 – 9, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis). Citrate synthase activity in (E) HDAC6 KO (n = 4, one-way ANOVA) and (F) Adv-HDAC6 KO mice (n = 4, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc analysis). Results are expressed as means ± SEM;* p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Collectively, our data suggest that inhibition of sensory neuron HDAC6 is sufficient to protect against cisplatin-induced loss of IENFs and axonal mitochondrial deficiency, while inhibition of HDAC6 in additional cell types is required to protect against the development of mechanical allodynia and mitochondrial deficits in the cell bodies of DRG neurons.

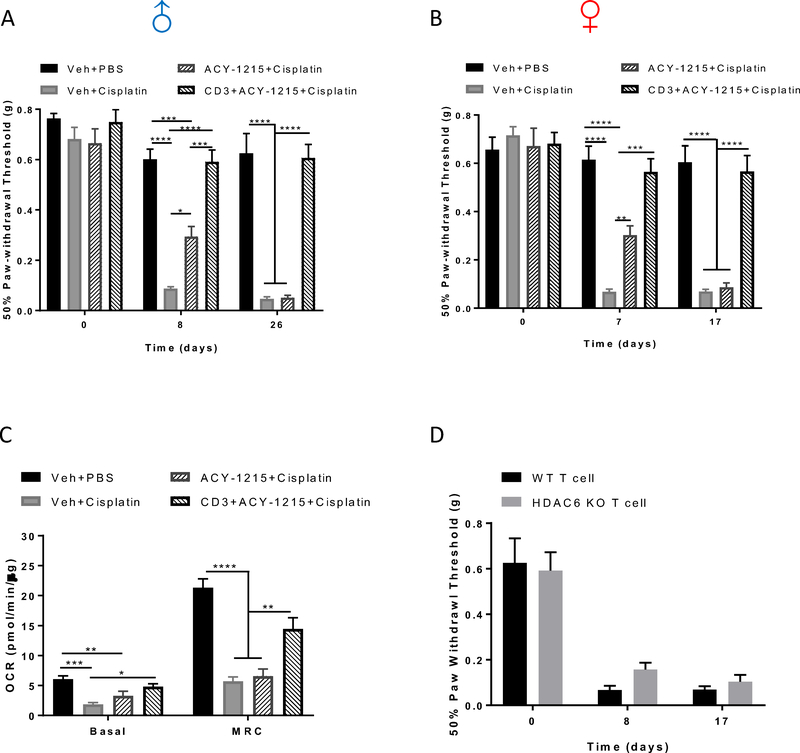

The protective effects of HDAC6 inhibition on mechanical allodynia and DRG mitochondrial dysfunction depend on the presence of T cells

T cells play an essential role in the spontaneous resolution of mechanical allodynia after completion of chemotherapy[31;35]. We hypothesized that T cells may also play a role in the protective effects of HDAC6 inhibition or global deletion of HDAC6 on cisplatin-induced allodynia and damage to mitochondria in cell bodies of DRG neurons. To test his hypothesis, we treated Rag2 KO mice which do not have mature T or B cells, with ACY-1215 and cisplatin. Cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia was similar in WT and Rag2 KO mice, which is consistent with our previous findings[31;35]. However, the effect of HDAC6 inhibition on mechanical allodynia differed between WT and Rag2 KO mice; co-administration of the HDAC6 inhibitor with cisplatin did not prevent cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia in either male or female Rag2 KO mice. Reconstitution of Rag2 KO mice with CD3+ T cells re-established the protective effects of ACY-1215 (Figure 8A and B).

Figure 8. Effects of the HDAC6 inhibitor ACY-1215 on cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia and DRG neuronal mitochondrial deficits in Rag2 KO mice.

Rag2 KO mice were treated with ACY-1215 and cisplatin as in WT mice. CD3+ T cells were adoptively transferred one week before the start of ACY-1215 and cisplatin treatment. Mechanical sensitivity was measured in (A) male and (B) female mice (n = 8 – 9, one-way ANOVA). Mechanical sensitivity was measured on day 7 or 8 after start of cisplatin treatment (2 or 3 days after completion of the first round of dosing) and day 17 or 26 after start of cisplatin treatment (2 or 11 days after completion of the second round of dosing). (C) DRG mitochondrial bioenergetics from ACY-1215 and cisplatin-treated Rag2 KO mice with or without CD3+ T cells reconstitution (n = 6 – 8, one-way ANOVA). (D) Mechanical sensitivity was measured in cisplatin-treated Rag2 KO mice reconstituted with HDAC6 KO CD3+ T cells (n = 8, student’s t test). Results are expressed as means ± SEM;* p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

Given the link between mechanical sensitivity and mitochondrial function in DRG neurons we identified in the Adv-HDAC6 KO mice, we next tested the contribution of T cells to the protective effect of HDAC6 inhibition on DRG mitochondrial bioenergetics. ACY-1215 did not prevent cisplatin-induced DRG mitochondrial dysfunction in Rag2 KO mice. In the absence of the inhibitor, cisplatin decreased mitochondrial bioenergetics to the same extent in WT and Rag2 KO mice (Figure 8C). However, the protective effect of the HDAC6 inhibitor on DRG neuron mitochondrial function was re-established by reconstitution of Rag2 KO mice with CD3+ T cells (Figure 8C). Thus, T cells are critically involved in the preventive effects of HDAC6 inhibition on both cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia and mitochondrial deficits in DRG neuronal cell bodies.

In contrast, inhibition of HDAC6 prevented the loss of IENFs (Figure 9A and B) and impaired mitochondrial bioenergetics in the tibial nerves (Figure 9C and D) in Rag2 mice despite the lack of T cells. Thus, T cells are apparently not involved in this process, which is consistent with our data from Adv-HDAC6 KO mice revealing HDAC6 in the sensory neurons as the key factor underlying cisplatin-induced IENF loss.

Figure 9. Effects of the HDAC6 inhibitor ACY-1215 on cisplatin-induced IENF loss and changes in tibial nerve mitochondrial bioenergetics in Rag2 KO mice.

Rag2 KO mice were treated with ACY-1215 and cisplatin for two treatment cycles. CD3+ T cells were adoptively transferred one week before the start of ACY-1215 and cisplatin treatment. Paw biopsies were stained with antibodies against PGP9.5 (red) and collagen (green). (A) Representative images from each treatment group, scale bar = 20 mm, magnification × 40. (B) Quantification of IENF density (n = 4 – 8, one-way ANOVA). Effects of cisplatin and ACY-1215 on (C) basal OCR, MRC and (D) basal ECAR in Rag2 KO mice with or without T cell reconstitution (n = 6 – 8, one-way ANOVA). Results are expressed as means ± SEM;**p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001.

To determine whether deleting HDAC6 from T cells is sufficient to prevent cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia, we reconstituted Rag2 KO mice with CD3+ T cells isolated from HDAC6 KO mice and treated them with cisplatin. However, reconstitution with HDAC6 KO T cells did not prevent cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia (Figure 8D).

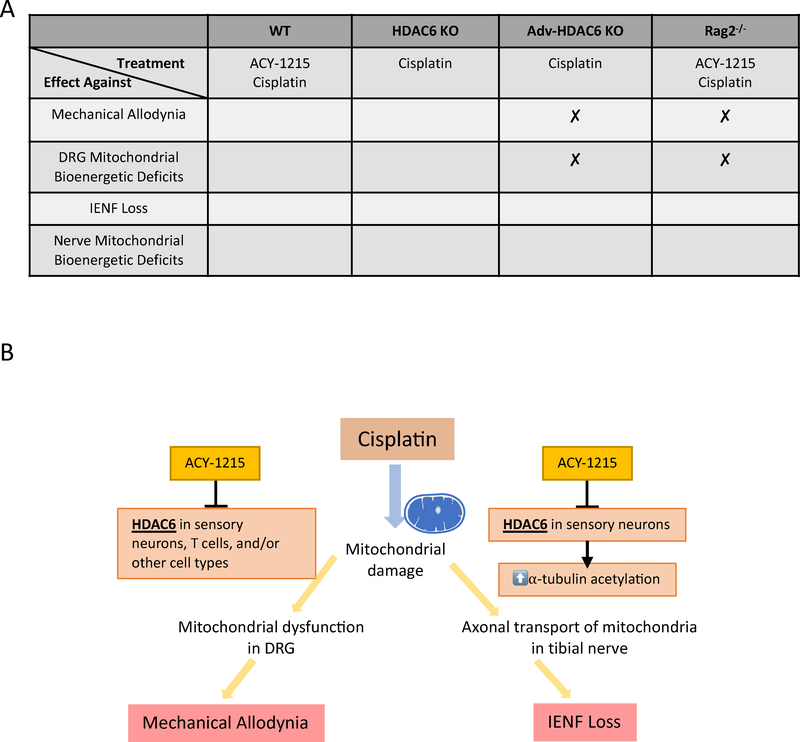

Discussion

CIPN is a highly prevalent and serious health care concern that negatively impacts cancer treatment and the quality of life of cancer patients and survivors[1;42;47]. Currently, there is no FDA approved treatment to prevent or manage CIPN[10;42], emphasizing the urgent need to unveil the pathological mechanism underlying CIPN and to identify preventive and/or disease-modifying interventions. In the current study, we identified the cell-specific contribution of HDAC6 to the development of different aspects of CIPN (summarized in Figure 10). We show that pharmacological inhibition of HDAC6 protects against CIPN in both male and female mice, and this protective effect is recapitulated by global deletion of the HDAC6 gene. HDAC6 inhibition or global genetic deletion of HDAC6 also prevented cisplatin-induced mitochondrial deficits in DRG neurons and peripheral nerves, supporting the hypothesis that there is a fundamental contribution of mitochondrial damage to CIPN. Moreover, it reveals HDAC6 as a crucial molecule in the development of various aspects of cisplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy. Surprisingly, however, deletion of HDAC6 in advillin-positive sensory neurons did not fully prevent cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia and did not protect against DRG neuronal mitochondrial dysfunction, while it was sufficient to protect against IENF loss and reduced mitochondrial content in the nerve. Finally, we identify a key role for the adaptive immune system and in particular T cells in the preventive effects of pharmacological HDAC6 inhibition on mechanical allodynia and mitochondrial deficits in DRG neuron induced by cisplatin. In contrast, T cells are not required for protection against IENF loss or mitochondrial loss in the nerve. Taken together, our current findings identify an essential and cell-specific role of HDAC6 in the development of two key, but mechanistically distinct, aspects of CIPN, i.e. mechanical allodynia and the loss of IENFs.

Figure 10. Summary.

(A) Summary of treatments and protective effects observed in 4 different mouse strains used in our study. (B) Illustration for the working model of our study.

In line with the clinical data that gender does not predict susceptibility for CIPN in cancer patients[27], we did not detect sex differences in cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia. This is consistent with previous rodent CIPN studies from our group and others[22;35;44;46;54]. Additionally, there is no sex difference in the protective effects of pharmacological inhibition of HDAC6 during cisplatin treatment on mechanical allodynia in WT or Rag2 KO mice with or without T cell reconstitution. Collectively, our results support the potential of utilizing HDAC6 inhibitors as preventive agents for CIPN in a sex-independent manner.

It has been well established that platinum-based drugs induce both mechanical allodynia as well as loss of IENFs, a hallmark of small fiber neuropathy[18]. Our current findings demonstrate that the mechanisms underlying these two characteristics of CIPN are distinct and that they can develop independently of each other. This is in line with clinical observations in patients with polyneuropathy of various origins indicating that there is no clear correlation between IENF loss and allodynic symptoms[55]. Mechanistically, our data indicate that mitochondrial function in the DRG neuronal cell bodies is critical for the maintenance of normal mechanical sensitivity, whereas axonal mitochondrial bioenergetics are more closely linked to the maintenance of IENF density (Figure 10B).

Mitochondria are essential in cellular energy production as well as the maintenance of ion homeostasis, the dysregulation of which could lead to neuronal hyperexcitability and ectopic discharges that contribute to allodynic behaviors in neuropathic pain[14;67]. For example, paclitaxel has been shown to cause rapid mitochondrial depolarization and Ca2+ release from mitochondria, which enhances intracellular Ca2+ concentration and the excitability of neurons[28;49]. Energy deficiency caused by mitochondrial dysfunction can also lead to inactivity of ion pumps including the Na+/K+ ATPase[17], resulting in aberrant spontaneous activity[5;64]. In support of a direct role of mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction in the generation of neuropathic pain, it has been shown that the mitochondrial ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin exacerbates paclitaxel- and oxaliplatin-induced allodynia in rats[63]. A targeted mutation in the mitochondrial respiratory chain Complex IV in advillin-positive sensory neurons lead to significant neuropathic pain symptoms including mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity[50]. Our RNA-Seq data show that cisplatin changes expression of genes involved in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation while genes involved in glycolysis and TCA cycle are minimally impacted. Consistently, functional measurement of DRG neurons reveals that cisplatin reduces basal OCR and MRC, indicative of impaired oxidative phosphorylation. ECAR, which serves as a rough measurement of glycolysis and TCA cycle activity[53], remains unaltered in cisplatin-treated neurons.

Despite a clear role for HDAC6 in the establishment of cisplatin-induced mitochondrial damage in sensory neurons and mechanical allodynia, we demonstrate that deletion of HDAC6 only in sensory neurons is not sufficient to achieve full protective effects. Sensory neuron deletion of HDAC6 partially protected against cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia assessed after 1 round of cisplatin, however, the protective effects did not sustain following the second round of treatment. Similar data were obtained in Rag2 KO mice treated with cisplatin and the HDAC6 inhibitor ACY-1215. These findings imply that there is a partial contribution of HDAC6 in sensory neurons to the initial development of cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia, while other pathways take over after prolonged cisplatin treatment. Moreover, our data reveal that the beneficial effects of HDAC6 inhibition on mechanical allodynia and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation activity of DRG neurons are dependent on T cells. This is intriguing as these data suggest that interactions of neurons and T cells have a significant impact on the bioenergetic status of the sensory neurons. However, it remains to be determined how T cell-sensory neuron interactions regulate allodynia and DRG mitochondrial activity.

HDAC6 has been implicated in the regulation of T cell phenotype and activity[4;16;59;65]. Specifically, HDAC6 inhibition or knockdown enhances the number and suppressive activity of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and upregulates the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10[16], both of which are antinociceptive[2;31;35](Laumet, in prep). Interestingly, it has been shown recently that IL-10 can promote mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation[24], opening up the possibility that HDAC6 inhibition promotes DRG mitochondrial health via a mechanism involving enhanced IL-10 production. Taken together, we propose that HDAC6 inhibition during cisplatin treatment promotes DRG mitochondrial health and prevents development of mechanical allodynia via increasing the regulatory activity of T cells and IL-10 production. Notably, despite the key contribution of T cells to the prevention of cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia in response to HDAC6 inhibition, adoptive transfer of HDAC6 KO T cells to Rag2 KO mice was not sufficient to prevent cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia. These data indicate that targeting HDAC6 in the T cells alone is clearly not sufficient. Our results indicate that prevention of mechanical allodynia in CIPN requires targeting of HDAC6 in multiple cell types and is dependent on the presence of T cells. The potential involvements of HDAC6 in T cells and other cell types such as macrophages and spinal cord neurons require further investigation in future studies.

In the tibial nerves, which contain the axons of DRG sensory neurons, the negative impact of cisplatin on mitochondrial bioenergetics is associated with a reduction in mitochondrial content rather than impairment of oxidative phosphorylation activity. Axonal transport of mitochondrial is an energy-consuming process, and the transport of mitochondria along axons has been shown to be membrane potential-dependent[48]. Therefore, it is conceivable that only mitochondria with normal electron transport chain activity could afford the “energy toll” to travel all the way towards axonal terminal[48], and that bioenergetic deficits in the tibial nerves are more relevant to a reduction in mitochondrial content. Importantly, sensory neuron HDAC6 is playing a direct role in this process, whereas T cells are not involved. Increased HDAC6 activity has been reported to impair axonal transport of mitochondria in various neurodegenerative diseases[6;9;12;15;19;20;30;41;45;51;60]. HDAC6 deacetylates α-tubulin which reduces binding of axonal motor proteins and impaired transport of cellular cargos including the mitochondria[56;57]. Consistent with a role of neuronal HDAC6 in axonal mitochondrial transport, we showed previously that cisplatin reduces axonal mitochondrial movement in primary DRG cultures and that this is prevented by HDAC6 inhibition[32]. As a result of the lack of sufficient number and activity of mitochondria in the axonal terminals, localized energy crisis in the nerve terminals likely underlies the failure to maintain IENFs in the cutaneous surface of the hind paws[5;32;44]. Indeed, our data demonstrate that genetic deletion of sensory neuron HDAC6 is sufficient to prevent both the reduction in mitochondrial content in the tibial nerves and the loss of IENFs induced by cisplatin. Collectively, these data demonstrate for the first time that increased sensory neuronal HDAC6 activity is a key factor underlying the bioenergetic deficits in the nerves of cisplatin-treated mice and the associated IENF loss.

In summary, our study identifies the critical and cell-specific involvement of HDAC6 in the development of different signs of cisplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy. We identify sensory neuron HDAC6 as the key mediator for cisplatin-induced IENF loss and the loss of axonal mitochondrial content, indicating that the HDAC6 is crucially involved in the impairment of mitochondrial motility. On the other hand, it is not sufficient to delete HDAC6 in sensory neurons alone to fully prevent cisplatin-induced mechanical allodynia, and the protective effect of HDAC6 inhibition requires the presence of T cells. Moreover, our work advances the understanding of the mechanisms underlying CIPN by showing that mechanical allodynia occurs as a result of mitochondrial damage in the DRG neurons, whereas the loss of IENFs is more associated with deficits in axonal transport of mitochondria.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Regenacy Pharmaceuticals Inc. and grants CA208371, NS073939, and CA227064 from the National Institutes of Health. The RNA sequencing work was done with technical support from MD Anderson’s Sequencing and Microarray Facility, supported by MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant NIH CA016672.

Conflict of Interest: This study was supported in part by a research grant from Regenacy Pharmaceuticals to A.K. and C.J.H. who are also holding patent 15/170,335 entitled Histone deacetylase 6 selective inhibitors for the treatment of cisplatin-induced numbness.

REFERENCE

- [1].Alberti P, Cortinovis D, Frigeni B, Bidoli P, Cavaletti G. Neuropathic pain and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity: the issue. Pain Manag 2013;3(6):417–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Austin PJ, Kim CF, Perera CJ, Moalem-Taylor G. Regulatory T cells attenuate neuropathic pain following peripheral nerve injury and experimental autoimmune neuritis. Pain 2012;153(9):1916–1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bali P, Pranpat M, Bradner J, Balasis M, Fiskus W, Guo F, Rocha K, Kumaraswamy S, Boyapalle S, Atadja P, Seto E, Bhalla K. Inhibition of histone deacetylase 6 acetylates and disrupts the chaperone function of heat shock protein 90: a novel basis for antileukemia activity of histone deacetylase inhibitors. J Biol Chem 2005;280(29):26729–26734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Beier UH, Akimova T, Liu Y, Wang L, Hancock WW. Histone/protein deacetylases control Foxp3 expression and the heat shock response of T-regulatory cells. Curr Opin Immunol 2011;23(5):670–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bennett GJ, Doyle T, Salvemini D. Mitotoxicity in distal symmetrical sensory peripheral neuropathies. Nat Rev Neurol 2014;10(6):326–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Benoy V, Van Helleputte L, Prior R, d’Ydewalle C, Haeck W, Geens N, Scheveneels W, Schevenels B, Cader MZ, Talbot K, Kozikowski AP, Vanden Berghe P, Van Damme P, Robberecht W, Van Den Bosch L. HDAC6 is a therapeutic target in mutant GARS-induced Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Brain 2018;141(3):673–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bitler BG, Wu S, Park PH, Hai Y, Aird KM, Wang Y, Zhai Y, Kossenkov AV, Vara-Ailor A, Rauscher FJ III, Zou W, Speicher DW, Huntsman DG, Conejo-Garcia JR, Cho KR, Christianson DW, Zhang R. ARID1A-mutated ovarian cancers depend on HDAC6 activity. Nat Cell Biol 2017;19(8):962–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Boyette-Davis JA, Walters ET, Dougherty PM. Mechanisms involved in the development of chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. Pain Manag 2015;5(4):285–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Carlomagno Y, Chung DC, Yue M, Castanedes-Casey M, Madden BJ, Dunmore J, Tong J, DeTure M, Dickson DW, Petrucelli L, Cook C. An acetylation-phosphorylation switch that regulates tau aggregation propensity and function. J Biol Chem 2017;292(37):15277–15286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cavaletti G, Marmiroli P. Pharmacotherapy options for managing chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2018;19(2):113–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods 1994;53(1):55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chen S, Owens GC, Makarenkova H, Edelman DB. HDAC6 regulates mitochondrial transport in hippocampal neurons. PLoS One 2010;5(5):e10848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chiu GS, Boukelmoune N, Chiang ACA, Peng B, Rao V, Kingsley C, Liu HL, Kavelaars A, Kesler SR, Heijnen CJ. Nasal administration of mesenchymal stem cells restores cisplatin-induced cognitive impairment and brain damage in mice. Oncotarget 2018;9(85):35581–35597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chung JM, Chung K. Importance of hyperexcitability of DRG neurons in neuropathic pain. Pain Pract 2002;2(2):87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].d’Ydewalle C, Krishnan J, Chiheb DM, Van Damme P, Irobi J, Kozikowski AP, Vanden Berghe P, Timmerman V, Robberecht W, Van Den Bosch L. HDAC6 inhibitors reverse axonal loss in a mouse model of mutant HSPB1-induced Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Nat Med 2011;17(8):968–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].de Zoeten EF, Wang L, Butler K, Beier UH, Akimova T, Sai H, Bradner JE, Mazitschek R, Kozikowski AP, Matthias P, Hancock WW. Histone deacetylase 6 and heat shock protein 90 control the functions of Foxp3(+) T-regulatory cells. Mol Cell Biol 2011;31(10):2066–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Erecinska M, Silver IA. Ions and energy in mammalian brain. Prog Neurobiol 1994;43(1):37–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Fukuda Y, Li Y, Segal RA. A Mechanistic Understanding of Axon Degeneration in Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. Front Neurosci 2017;11:481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Govindarajan N, Rao P, Burkhardt S, Sananbenesi F, Schluter OM, Bradke F, Lu J, Fischer A. Reducing HDAC6 ameliorates cognitive deficits in a mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease. EMBO Mol Med 2013;5(1):52–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Guo W, Naujock M, Fumagalli L, Vandoorne T, Baatsen P, Boon R, Ordovas L, Patel A, Welters M, Vanwelden T, Geens N, Tricot T, Benoy V, Steyaert J, Lefebvre-Omar C, Boesmans W, Jarpe M, Sterneckert J, Wegner F, Petri S, Bohl D, Vanden Berghe P, Robberecht W, Van Damme P, Verfaillie C, Van Den Bosch L. HDAC6 inhibition reverses axonal transport defects in motor neurons derived from FUS-ALS patients. Nat Commun 2017;8(1):861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hubbert C, Guardiola A, Shao R, Kawaguchi Y, Ito A, Nixon A, Yoshida M, Wang XF, Yao TP. HDAC6 is a microtubule-associated deacetylase. Nature 2002;417(6887):455–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hwang BY, Kim ES, Kim CH, Kwon JY, Kim HK. Gender differences in paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain behavior and analgesic response in rats. Korean J Anesthesiol 2012;62(1):66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Iaconelli J, Xuan L, Karmacharya R. HDAC6 Modulates Signaling Pathways Relevant to Synaptic Biology and Neuronal Differentiation in Human Stem-Cell-Derived Neurons. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ip WKE, Hoshi N, Shouval DS, Snapper S, Medzhitov R. Anti-inflammatory effect of IL-10 mediated by metabolic reprogramming of macrophages. Science 2017;356(6337):513–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Izycki D, Niezgoda AA, Kazmierczak M, Piorunek T, Izycka N, Karaszewska B, Nowak-Markwitz E. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy - diagnosis, evolution and treatment. Ginekol Pol 2016;87(7):516–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Janes K, Doyle T, Bryant L, Esposito E, Cuzzocrea S, Ryerse J, Bennett GJ, Salvemini D. Bioenergetic deficits in peripheral nerve sensory axons during chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain resulting from peroxynitrite-mediated post-translational nitration of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase. Pain 2013;154(11):2432–2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kerckhove N, Collin A, Conde S, Chaleteix C, Pezet D, Balayssac D. Long-Term Effects, Pathophysiological Mechanisms, and Risk Factors of Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathies: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Front Pharmacol 2017;8:86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kidd JF, Pilkington MF, Schell MJ, Fogarty KE, Skepper JN, Taylor CW, Thorn P. Paclitaxel affects cytosolic calcium signals by opening the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. J Biol Chem 2002;277(8):6504–6510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol 2010;8(6):e1000412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kim C, Choi H, Jung ES, Lee W, Oh S, Jeon NL, Mook-Jung I. HDAC6 inhibitor blocks amyloid beta-induced impairment of mitochondrial transport in hippocampal neurons. PLoS One 2012;7(8):e42983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Krukowski K, Eijkelkamp N, Laumet G, Hack CE, Li Y, Dougherty PM, Heijnen CJ, Kavelaars A. CD8+ T Cells and Endogenous IL-10 Are Required for Resolution of Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathic Pain. J Neurosci 2016;36(43):11074–11083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Krukowski K, Ma J, Golonzhka O, Laumet GO, Gutti T, van Duzer JH, Mazitschek R, Jarpe MB, Heijnen CJ, Kavelaars A. HDAC6 inhibition effectively reverses chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Pain 2017;158(6):1126–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Krukowski K, Nijboer CH, Huo X, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ. Prevention of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy by the small-molecule inhibitor pifithrin-mu. Pain 2015;156(11):2184–2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Larsen S, Nielsen J, Hansen CN, Nielsen LB, Wibrand F, Stride N, Schroder HD, Boushel R, Helge JW, Dela F, Hey-Mogensen M. Biomarkers of mitochondrial content in skeletal muscle of healthy young human subjects. J Physiol 2012;590(14):3349–3360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Laumet G, Edralin JD, Dantzer R, Heijnen CJ, Kavelaars A. Cisplatin educates CD8+ T cells to prevent and resolve chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in mice. Pain 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lees JG, Makker PG, Tonkin RS, Abdulla M, Park SB, Goldstein D, Moalem-Taylor G. Immune-mediated processes implicated in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Eur J Cancer 2017;73:22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Li T, Zhang C, Hassan S, Liu X, Song F, Chen K, Zhang W, Yang J. Histone deacetylase 6 in cancer. J Hematol Oncol 2018;11(1):111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Li Y, Shin D, Kwon SH. Histone deacetylase 6 plays a role as a distinct regulator of diverse cellular processes. FEBS J 2013;280(3):775–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lwin T, Zhao X, Cheng F, Zhang X, Huang A, Shah B, Zhang Y, Moscinski LC, Choi YS, Kozikowski AP, Bradner JE, Dalton WS, Sotomayor E, Tao J. A microenvironment-mediated c-Myc/miR-548m/HDAC6 amplification loop in non-Hodgkin B cell lymphomas. J Clin Invest 2013;123(11):4612–4626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ma J, Farmer KL, Pan P, Urban MJ, Zhao H, Blagg BS, Dobrowsky RT. Heat shock protein 70 is necessary to improve mitochondrial bioenergetics and reverse diabetic sensory neuropathy following KU-32 therapy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2014;348(2):281–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ma J, Huo X, Jarpe MB, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ. Pharmacological inhibition of HDAC6 reverses cognitive impairment and tau pathology as a result of cisplatin treatment. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2018;6(1):103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ma J, Kavelaars A, Dougherty PM, Heijnen CJ. Beyond symptomatic relief for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: Targeting the source. Cancer 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ma J, Pan P, Anyika M, Blagg BS, Dobrowsky RT. Modulating Molecular Chaperones Improves Mitochondrial Bioenergetics and Decreases the Inflammatory Transcriptome in Diabetic Sensory Neurons. ACS Chem Neurosci 2015;6(9):1637–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Maj MA, Ma J, Krukowski KN, Kavelaars A, Heijnen CJ. Inhibition of Mitochondrial p53 Accumulation by PFT-mu Prevents Cisplatin-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy. Front Mol Neurosci 2017;10:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Majid T, Griffin D, Criss Z 2nd, Jarpe M, Pautler RG. Pharmocologic treatment with histone deacetylase 6 inhibitor (ACY-738) recovers Alzheimer’s disease phenotype in amyloid precursor protein/presenilin 1 (APP/PS1) mice. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2015;1(3):170–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Mao-Ying QL, Kavelaars A, Krukowski K, Huo XJ, Zhou W, Price TJ, Cleeland C, Heijnen CJ. The anti-diabetic drug metformin protects against chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in a mouse model. PLoS One 2014;9(6):e100701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Marmiroli P, Scuteri A, Cornblath DR, Cavaletti G. Pain in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neurotoxicity. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2017;22(3):156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Miller KE, Sheetz MP. Axonal mitochondrial transport and potential are correlated. J Cell Sci 2004;117(Pt 13):2791–2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Mironov SL, Ivannikov MV, Johansson M. [Ca2+]i signaling between mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum in neurons is regulated by microtubules. From mitochondrial permeability transition pore to Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release. J Biol Chem 2005;280(1):715–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Mitchell R, Campbell G, Mikolajczak M, McGill K, Mahad D, Fleetwood-Walker SM. A Targeted Mutation Disrupting Mitochondrial Complex IV Function in Primary Afferent Neurons Leads to Pain Hypersensitivity Through P2Y1 Receptor Activation. Mol Neurobiol 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Mo Z, Zhao X, Liu H, Hu Q, Chen XQ, Pham J, Wei N, Liu Z, Zhou J, Burgess RW, Pfaff SL, Caskey CT, Wu C, Bai G, Yang XL. Aberrant GlyRS-HDAC6 interaction linked to axonal transport deficits in Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. Nat Commun 2018;9(1):1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Molassiotis A, Cheng HL, Lopez V, Au JSK, Chan A, Bandla A, Leung KT, Li YC, Wong KH, Suen LKP, Chan CW, Yorke J, Farrell C, Sundar R. Are we mis-estimating chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy? Analysis of assessment methodologies from a prospective, multinational, longitudinal cohort study of patients receiving neurotoxic chemotherapy. BMC Cancer 2019;19(1):132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Mookerjee SA, Brand MD. Measurement and Analysis of Extracellular Acid Production to Determine Glycolytic Rate. J Vis Exp 2015(106):e53464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Naji-Esfahani H, Vaseghi G, Safaeian L, Pilehvarian AA, Abed A, Rafieian-Kopaei M. Gender differences in a mouse model of chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain. Lab Anim 2016;50(1):15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Nebuchennykh M, Loseth S, Lindal S, Mellgren SI. The value of skin biopsy with recording of intraepidermal nerve fiber density and quantitative sensory testing in the assessment of small fiber involvement in patients with different causes of polyneuropathy. J Neurol 2009;256(7):1067–1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Reed NA, Cai D, Blasius TL, Jih GT, Meyhofer E, Gaertig J, Verhey KJ. Microtubule acetylation promotes kinesin-1 binding and transport. Curr Biol 2006;16(21):2166–2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Sainath R, Gallo G. The dynein inhibitor Ciliobrevin D inhibits the bidirectional transport of organelles along sensory axons and impairs NGF-mediated regulation of growth cones and axon branches. Dev Neurobiol 2015;75(7):757–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Santo L, Hideshima T, Kung AL, Tseng JC, Tamang D, Yang M, Jarpe M, van Duzer JH, Mazitschek R, Ogier WC, Cirstea D, Rodig S, Eda H, Scullen T, Canavese M, Bradner J, Anderson KC, Jones SS, Raje N. Preclinical activity, pharmacodynamic, and pharmacokinetic properties of a selective HDAC6 inhibitor, ACY-1215, in combination with bortezomib in multiple myeloma. Blood 2012;119(11):2579–2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Segretti MC, Vallerini GP, Brochier C, Langley B, Wang L, Hancock WW, Kozikowski AP. Thiol-Based Potent and Selective HDAC6 Inhibitors Promote Tubulin Acetylation and T-Regulatory Cell Suppressive Function. ACS Med Chem Lett 2015;6(11):1156–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Simoes-Pires C, Zwick V, Nurisso A, Schenker E, Carrupt PA, Cuendet M. HDAC6 as a target for neurodegenerative diseases: what makes it different from the other HDACs? Mol Neurodegener 2013;8:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Van Helleputte L, Kater M, Cook DP, Eykens C, Rossaert E, Haeck W, Jaspers T, Geens N, Vanden Berghe P, Gysemans C, Mathieu C, Robberecht W, Van Damme P, Cavaletti G, Jarpe M, Van Den Bosch L. Inhibition of histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) protects against vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathies and inhibits tumor growth. Neurobiol Dis 2018;111:59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Vogl DT, Raje N, Jagannath S, Richardson P, Hari P, Orlowski R, Supko JG, Tamang D, Yang M, Jones SS, Wheeler C, Markelewicz RJ, Lonial S. Ricolinostat, the First Selective Histone Deacetylase 6 Inhibitor, in Combination with Bortezomib and Dexamethasone for Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23(13):3307–3315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Xiao WH, Bennett GJ. Effects of mitochondrial poisons on the neuropathic pain produced by the chemotherapeutic agents, paclitaxel and oxaliplatin. Pain 2012;153(3):704–709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Xiao WH, Zheng H, Bennett GJ. Characterization of oxaliplatin-induced chronic painful peripheral neuropathy in the rat and comparison with the neuropathy induced by paclitaxel. Neuroscience 2012;203:194–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Xu K, Yang WY, Nanayakkara GK, Shao Y, Yang F, Hu W, Choi ET, Wang H, Yang X. GATA3, HDAC6, and BCL6 Regulate FOXP3+ Treg Plasticity and Determine Treg Conversion into Either Novel Antigen-Presenting Cell-Like Treg or Th1-Treg. Front Immunol 2018;9:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Yee AJ, Bensinger WI, Supko JG, Voorhees PM, Berdeja JG, Richardson PG, Libby EN, Wallace EE, Birrer NE, Burke JN, Tamang DL, Yang M, Jones SS, Wheeler CA, Markelewicz RJ, Raje NS. Ricolinostat plus lenalidomide, and dexamethasone in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: a multicentre phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17(11):1569–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Zhang H, Dougherty PM. Enhanced excitability of primary sensory neurons and altered gene expression of neuronal ion channels in dorsal root ganglion in paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. Anesthesiology 2014;120(6):1463–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Zhang Y, Kwon S, Yamaguchi T, Cubizolles F, Rousseaux S, Kneissel M, Cao C, Li N, Cheng HL, Chua K, Lombard D, Mizeracki A, Matthias G, Alt FW, Khochbin S, Matthias P. Mice lacking histone deacetylase 6 have hyperacetylated tubulin but are viable and develop normally. Mol Cell Biol 2008;28(5):1688–1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Zheng H, Xiao WH, Bennett GJ. Functional deficits in peripheral nerve mitochondria in rats with paclitaxel- and oxaliplatin-evoked painful peripheral neuropathy. Exp Neurol 2011;232(2):154–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Zheng H, Xiao WH, Bennett GJ. Mitotoxicity and bortezomib-induced chronic painful peripheral neuropathy. Exp Neurol 2012;238(2):225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Zimmermann M Ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals. Pain 1983;16(2):109–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]