Abstract

Adenocarcinoma of the cervix is less common than squamous cell carcinoma. Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (adenoma malignum) is considered an extremely well-differentiated variant of GAS. An association exists between GAS and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, which is a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation and multiple hamartomatous polyps in the gastrointestinal tracts. The incidence of GAS in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is estimated to be 11–17%. We present a rare case of adenoma malignum, diagnosed using colposcopic biopsy in a woman with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, which was histopathologically confirmed to be GAS after surgery.

Keywords: Adenocarcinoma, Uterine cervical neoplasms, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome

Introduction

Gastric-type adenocarcinoma (GAS) is a subtype of endocervical mucinous adenocarcinoma [1]. Cervical adenocarcinoma is less common than squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. However, the incidence of cervical adenocarcinoma has been increasing, especially in young females and is estimated to account for up to 25% of all invasive cervical carcinomas [2]. Adenoma malignum is a variant of minimal deviation GAS and accounts for approximately 1% of all cervical adenocarcinomas [3].

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation and multiple hamartomatous polyps in the gastrointestinal tracts [4]. The estimated incidence ranges from 1 in 50,000 to 1 in 200,000 live births [5,6]. According to previous reports, 11–17% of women with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome are reported to have GAS [7,8]. We report a case of adenoma malignum, diagnosed using colposcopic biopsy in a woman with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, which was histopathologically confirmed to be GAS after surgery.

Case report

A 36-year-old woman with vaginal discharge and chronic pelvic pain visited our institution in November 2017. The patient was nulliparous and not sexually active. Her Papanicolaou test result was normal in August 2017. She had been diagnosed with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome at a tertiary hospital and underwent laparoscopic surgery for strangulated intussusception of the small intestine in 2010.

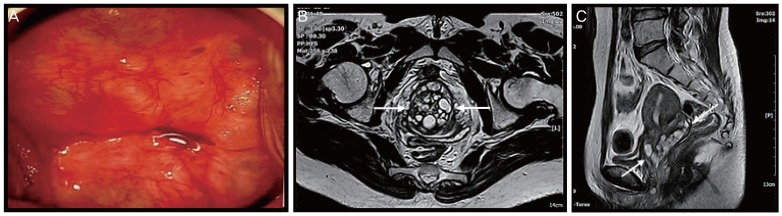

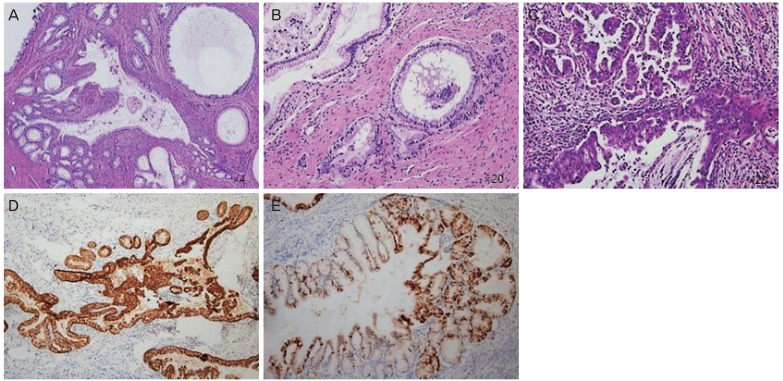

A clear mucoid vaginal discharge was prominent on pelvic examination. The surface of the cervix was smooth, with multiple nabothian cysts. However, the cervix was markedly enlarged with a diameter of 6–7 cm. Sonographic findings included a slightly enlarged uterus with a prominent cervix and multiple cystic lesions. These were thought to more likely represent multiple nabothian cysts rather than tumors. Colposcopy-guided cervical biopsy (at 6 and 12 o'clock) was performed for differential diagnosis from cervical tumor (Fig. 1A). On histopathological examination, a well-differentiated, gastric-type mucinous carcinoma (adenoma malignum) was identified (Fig. 2A and B). Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a prominent uterine cervix (5.6×4×1.9 cm) with multiple cystic lesions (Fig. 1B and C). The mass was confined to the cervix without parametrial involvement, and no evidence of metastatic lymphadenopathy was found. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) revealed a faint focal fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on the right side of the cervix, which proved to be a small malignant lesion. No enlargement or abnormal uptake in the pelvic and retroperitoneal lymph nodes or evidence of distant metastasis was found. Serum tumor markers were within their normal ranges (squamous cell carcinoma antigen, 0.8 ng/mL; carbohydrate antigen 19-9, <0.6 U/mL; carcinoembryonic antigen, 2.0 ng/mL). Colonoscopy and cystoscopy revealed no remarkable findings.

Fig. 1.

(A) The cervix on colposcopy. (B, C) Pelvic magnetic resonance image showing an enlargement of the cervix with multiple cystic lesions (arrow). The cervical parametrium is intact.

Fig. 2.

Histopathological results of colposcopic biopsy (A, B) and cervical conization (C-E). (A) The tumor consists of a mucinous epithelium infiltrating the cervical wall with little or no stromal reaction (original magnification ×4). (B) Cells lining these malignant glands have abundant clear cytoplasm and slightly enlarged nuclei with small nucleoli. Mitotic figures are rarely present (original magnification ×20). (C) Mucinous carcinoma of the gastric type with a more poorly differentiated component (original magnification ×20). (D) Immunohistochemical staining is positive for MUC6, a marker of pyloric gland mucin. (E) Immunohistochemical staining is focal positive but block pattern negative for p16.

Before surgery, clinical stage IB2 was diagnosed in accordance with the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics criteria. The tumor size on PET-CT was very small as compared with the size on MRI. In addition, the patient wanted uterine preservation; therefore, diagnostic conization was performed to confirm the tumor size and depth before radical surgery. The histopathological result of the conization indicated a gastric-type mucinous carcinoma with moderate differentiation (Fig. 2C-E). Specific findings were 1) a tumor size of 6 cm in the greatest dimension, 2) depth of invasion of 2 cm, 3) lymphovascular invasion, 4) involvement of both lateral margins, and 5) extension to the endometrium. Eventually, the patient underwent radical transabdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingectomy, bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection, and bilateral ovarian transposition. No tumor was found in the surgical margins of the vaginal wall or pelvic lymph nodes on intraoperative frozen biopsy. The final histopathological analysis of the specimen from radical surgery confirmed no residual carcinoma. No myometrial invasion or metastasis to pelvic lymph nodes was observed. The patient had adjuvant chemoradiation therapy after the radical surgery.

Discussion

Patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome have a high risk of developing several malignancies, including gastrointestinal, breast, and pancreatic cancers [9]. Among gynecological tumors, minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (MDA) and ovarian sex-cord tumors are associated with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome [7]. MDA (adenoma malignum), a rare subtype of gastric-type endocervical adenocarcinoma with minimal deviation, was first identified by Gusserow in 1870 [10]. As the microscopic findings of MDA resemble those of benign tumors, the immunohistochemical profile of diagnosis has been studied [11]. GAS and MDA can be diagnosed on the basis of the expression patterns of MUC6 and HIK1083 on immunohistochemical staining [12]. Neither tumor shows diffuse p16 expression, in contrast to the usual type of endocervical adenocarcinoma. In our case, the immunohistochemical result was positive for MUC6 (mouse monoclonal; MRQ-20, Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA, USA) and negative for p16 (mouse monoclonal; CINtec p16; Ventana, Tucson, AZ, USA; Fig. 2D and E).

The presentation of GAS of the cervix includes a hypertrophic cervical shape and abnormal uterine bleeding or watery vaginal discharge [7]. In female patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, which has some association with cervical adenocarcinoma, these symptoms should not be overlooked, although they are not critical for diagnosis. The diagnostic approach for GAS differs from that for human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cervical cancers because GAS is included in the group of non-HPV-associated tumors [13]. Studies suggest that preoperative diagnosis of this mucinous adenocarcinoma variant is difficult owing to its lack of correlation with Papanicolaou test results [14]. As the test result is normal in many cases, cervical cytological examination is insufficient for the diagnosis of GAS. Imaging studies such as MRI and pelvic ultrasonography can be helpful in the diagnosis of cervical masses. However, the final diagnosis can be made histopathologically by cervical biopsy or conization [14].

GAS is more aggressive than the typical endocervical adenocarcinoma. Patients with GAS show ovarian involvement, abdominal disease, and extraperitoneal recurrences (at prevalence rates of 35%, 20%, and 12%, respectively), which are more common than the complications observed in patients with typical endocervical adenocarcinoma [13]. The cancer-specific 5-year survival rate is 30–42%, lower than the 74–91% survival rate for the typical disease [13,15]. The prognosis of patients with GAS is worse than that of patients with HPV-related adenocarcinoma because patients with GAS tend to represent an advanced-stage disease and unusual metastatic organs. Owing to the high risk of malignancy in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, a more thorough cancer screening has been proposed. Annual pelvic sonography and cervical screening test have been recommended for cancer screening in females with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Although Papanicolaou smear results are usually negative in GAS, the presence of an enlarged cervix with multiple cysts in a patient with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is an indication for cervical biopsy.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of (IRB No. CGH-IRB-2018-17) and performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consents were obtained.

References

- 1.Kurman RJ, Carcangiu ML, Herrington CS, Young RH. WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adegoke O, Kulasingam S, Virnig B. Cervical cancer trends in the United States: a 35-year population-based analysis. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:1031–1037. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaminski PF, Norris HJ. Minimal deviation carcinoma (adenoma malignum) of the cervix. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1983;2:141–152. doi: 10.1097/00004347-198302000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giardiello FM, Trimbath JD. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and management recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Utsunomiya J, Gocho H, Miyanaga T, Hamaguchi E, Kashimure A. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: its natural course and management. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1975;136:71–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burt RW. Polyposis syndromes. Clin Perspect Gastroenterol. 2002;5:51–59. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young RH, Welch WR, Dickersin GR, Scully RE. Ovarian sex cord tumor with annular tubules: review of 74 cases including 27 with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and four with adenoma malignum of the cervix. Cancer. 1982;50:1384–1402. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19821001)50:7<1384::aid-cncr2820500726>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilks CB, Young RH, Aguirre P, DeLellis RA, Scully RE. Adenoma malignum (minimal deviation adenocarcinoma) of the uterine cervix. A clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:717–729. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198909000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giardiello FM, Brensinger JD, Tersmette AC, Goodman SN, Petersen GM, Booker SV, et al. Very high risk of cancer in familial Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1447–1453. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gusserow AL. Ueber sarcoma des uterus. Arch Gynakol. 1870;1:240–251. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silverberg SG, Hurt WG. Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (“adenoma malignum”) of the cervix: a reappraisal. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1975;121:971–975. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(75)90920-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikami Y, Kiyokawa T, Hata S, Fujiwara K, Moriya T, Sasano H, et al. Gastrointestinal immunophenotype in adenocarcinomas of the uterine cervix and related glandular lesions: a possible link between lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia/pyloric gland metaplasia and ‘adenoma malignum’. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:962–972. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karamurzin YS, Kiyokawa T, Parkash V, Jotwani AR, Patel P, Pike MC, et al. Gastric-type endocervical adenocarcinoma: an aggressive tumor with unusual metastatic patterns and poor prognosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:1449–1457. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takatsu A, Shiozawa T, Miyamoto T, Kurosawa K, Kashima H, Yamada T, et al. Preoperative differential diagnosis of minimal deviation adenocarcinoma and lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia of the uterine cervix: a multicenter study of clinicopathology and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:1287–1296. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31821f746c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kojima A, Mikami Y, Sudo T, Yamaguchi S, Kusanagi Y, Ito M, et al. Gastric morphology and immunophenotype predict poor outcome in mucinous adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:664–672. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213434.91868.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]