Abstract

Evidence is compiled to demonstrate a redox scale within Earth's photosynthesisers that correlates the specificity of their RuBisCO with organismal metabolic tolerance to anoxia, and ecological selection by dissolved O2/CO2 and nutrients. The Form 1B RuBisCO found in the chlorophyte green algae, has a poor selectivity between the two dissolved substrates, O2 and CO2, at the active site. This enzyme appears adapted to lower O2/CO2 ratios, or more “anoxic” conditions and therefore requires additional energetic or nutrient investment in a carbon concentrating mechanism (CCM) to boost the intracellular CO2/O2 ratio and maintain competitive carboxylation rates under increasingly high O2/CO2 conditions in the environment. By contrast the coccolithophores and diatoms evolved containing the more selective Rhodophyte Form 1D RuBisCO, better adapted to a higher O2/CO2 ratio, or more oxic conditions. This Form 1D RuBisCO requires lesser energetic or nutrient investment in a CCM to attain high carboxylation rates under environmentally high O2/CO2 ratios. Such a physiological relationship may underpin the succession of phytoplankton in the Phanerozoic oceans: the coccolithophores and diatoms took over the oceanic realm from the incumbent cyanobacteria and green algae when the upper ocean became persistently oxygenated, alkaline and more oligotrophic. The facultatively anaerobic green algae, able to tolerate the anoxic conditions of the water column and a periodically inundated soil, were better poised to adapt to the fluctuating anoxia associated with periods of submergence and emergence and transition onto the land. The induction of a CCM may exert a natural limit to the improvement of RuBisCO efficiency over Earth history. Rubisco specificity appears to adapt on the timescale of ∼100 Myrs. So persistent elevation of CO2/O2 ratios in the intracellular environment around the enzyme, may induce a relaxation in RuBisCO selectivity for CO2 relative to O2. The most efficient RuBisCO for net carboxylation is likely to be found in CCM-lacking algae that have been exposed to hyperoxic conditions for at least 100 Myrs, such as intertidal brown seaweeds.

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Dissolved O2/CO2 selects for a redox scale of phytoplankton Rubisco substrate selectivity and anaerobic metabolic ability.

-

•

Increasing O2/CO2 induced a positive feedback selecting for red-algal derived plastids at the start of the Mesozoic.

-

•

The relative affinity of RuBisCO for O2 and CO2 tunes to compensate for environmental O2/CO2 on timescales of 100–1000 yrs.

-

•

Induction of a CCM relaxes enzyme specificity over ∼ 100 Myrs providing a limit to improvement of RuBisCO selectivity.

-

•

Persistently high O2/CO2 ratios in restricted intertidal zones selects the most efficient RuBisCO in species lacking a CCM.

1. Aim

This hypothesis paper aims to integrate recent measurements of RuBisCO kinetic parameters across the phytoplankton and terrestrial plants together with data on the physiology, ecology and evolution of oxygenic photosynthesisers. New evidence suggests increased oxygenation of the ocean could have been a selective force in the transformation of the ocean from domination by the green algae to that of the red algal lineage at the Mesozoic. We aim to highlight the contrasting evolutionary trajectories of the green algal lineage with those of the red algal lineage from different ends of the redox spectrum and how selection for different biochemical parameters of the RuBisCO enzyme has worked through time and space. We explore the geological factors that may have triggered a perturbation in the dissolved O2/CO2 of the ocean leading to an environmental selection towards the mineralising red algal lineage.

2. Phanerozoic phytoplankton and upper ocean oxygenation

Three independent lines of evidence demonstrate that the Phanerozoic ocean was dominated by a succession of phytoplankton: microfossils, molecular biomarkers, and molecular clocks for individual clades. The low C28/C29 ratios of the sterane profiles of Paleozoic rocks are most likely driven by early diverging prasinophyte green algae, and chlorophyte green algae that produce high abundances of C29 relative to C27 and C28 sterols as found from a large, phylogenetically based survey of sterol profiles from the kingdom Plantae [1]. The Devonian saw an expansion of more derived prasinophyte algae (Chlorophyta) at the expense of the incumbent phytoplankton as evidenced by an extremely high sterane/hopane ratio in sedimentary lipids [2], and elevated C28:C29 sterane ratios [1,3]. The later and more derived groups of green algae produce a greater abundance of C28 relative to C27 and C29 sterols [1]. Later, the Mesozoic Ocean was taken over by the chlorophyll a+c containing phytoplankton of the haptophytes (e.g. coccolithophores) and heterokont (e.g. diatom) lineages, whose plastids are derived from red algae (Rhodophyta) via secondary endosymbiosis [[4], [5], [6]]. In each case the larger cell sizes of the phytoplankton, and in the latter, the addition of mineralising skeletons, added power to the biological pump of carbon and nutrients from the surface ocean to the deep, propagating oxygenation and with ramifications throughout the ecosystem.

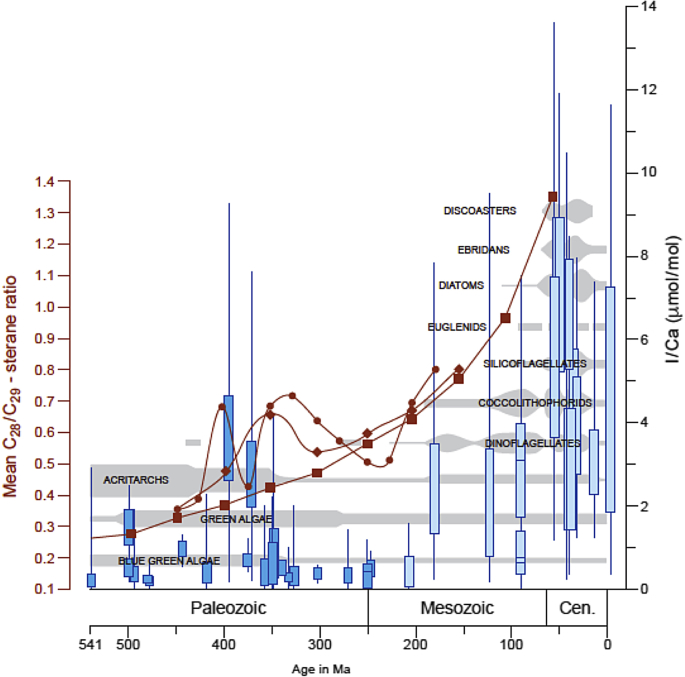

Recent evidence based on I/Ca in carbonates, a redox proxy sensitive to suboxia, identified an excursion in recorded I during the Devonian and a step change at 200 Ma, coincident with each of these micro-faunal revolutions [7]. Elevated I/Ca indicates increased ocean oxygenation, and is interpreted as a deepening of the oceanic oxygen minimum zone at each of these times achieving more persistently oxygenated modern day conditions at the Paleozoic-Mesozoic transition. This new record of I/Ca correlates with the abundance of the biomarker C28/C29 steranes, markers of the radiation in more derived green algae (Chlorophyta and Streptophyta) and the succession of the modern phytoplankton groups from a compilation of rock and oil samples (Fig. 1 [2,5,6]). Such a similarity between these two very different datasets founded on contrasting samples and geochemical analyses is strongly suggestive that there could be a common driver to both, such as an increase in surface water oxygenation.

Fig. 1.

A comparison of algal biomarker records from rock and oil samples with the I/Ca record of upper ocean oxygenation. The C28/C29-sterane ratio of 500 rock samples are plotted, averaged in 50 Myr steps (rhomboids), and in 25 Myr steps (filled circles) compared with 400 oil samples (squares) analysed by Grantham and Wakefield [8] and presented in Schwark and Empt, [2]. Candlestick plot showing ranges of I/Ca values for Paleozoic (dark blue) and Meso-Cenozoic (light blue) from Lu et al., [7]. Boxes mark the 25th and 75th percentiles of values at each locality, and the whiskers show the maximum and minimum. Also shown in grey bars are the inferred abundances of different algal groups throughout the Phanerozoic. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.).

3. Chlorophyll a+c algae have a higher RuBisCO specificity than chlorophyll b algae

The form and specificity of Ribulose‐1,5‐bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO, EC 4.1.1.39), the enzyme that catalyzes CO2 fixation during oxygenic photosynthesis, is also transformed across the open ocean upon the transition from a chlorophyll b to a chlorophyll a+c algal lineage dominated assemblage.

It is thought that all Forms of RuBisCO arose from a Form III RuBisCO within an Archaean methanogen [[9], [10], [11]]. This ancestral form gave rise to all other forms through a complex history involving a number of horizontal and vertical gene transfers [9]. Evolution within Proteobacteria diversified Form I into IA, IC and ID, and within cyanobacteria Form I evolved into Form IB. Most algae and all higher plants contain Form I RuBisCO, a 560 kDa holoenzyme of eight 50–55 kDa large (LSU) and eight 12–18 kDa small (SSU) subunits [12]. Less prevalent is Form II RuBisCO, a dimer of two LSU found in peridinin-containing dinoflagellates and some prokaryotes [13]. Only Form I and II RuBisCO are used for oxygenic photosynthesis and Form I is responsible for the bulk of this carbon fixation.

Form I RuBisCO can be further divided into subforms IA, IB, IC and ID. Form IA is found in α-cyanobacteria such as Prochlorococcus spp., while Form IB is found in higher plants, green algae and β-cyanobacteria. Form IC is found in some photosynthetic bacteria e.g. Rhodobacter sphaeroidea and Form ID is found in all non-green eukaryotic algae (i.e. red and chromist algae, except Form II-containing dinoflagellates) [14].

All Form I enzymes are structurally similar with 422 symmetry (tetragonal-trapezoidal crystal structure) and a core consisting of four LSU dimers (L2) arranged around a four-fold axis, capped at each end with four SSUs [13]. Forms IA – ID can be differentiated according to their amino acid sequence. Forms IA and IB are about 80% similar, as are the forms IC and ID. Between Forms IA/B and IC/D there is only about 60% sequence similarity [15,16]. Despite the different forms of I Rubisco, they all have the same functional active site [17].

During oxygenic photosynthesis, RuBisCO catalyzes two competitive reactions; fixation of CO2 for photosynthesis (carboxylation) and energy wasting photorespiration using O2 (oxygenation). The ability of a particular RuBisCO to discriminate between the non‐polar, structurally similar substrates CO2 and O2 is determined by the kinetic properties of the enzyme, denoted as the specificity factor (Ω):

| Ω = (VcKo/VoKc) | (1) |

where Vc and Vo are maximal velocities of the carboxylase and oxygenase reactions and Kc and Ko are the Michaelis constants for the susbtrates CO2 and O2. The carboxylation:oxygenation efficiency of the net reaction must also account for the CO2 and O2 concentrations at the catalytic site of the enzyme:

| carboxylation/oxygenation = (VcKo/VoKc)*([CO2]/[O2]) | (2) |

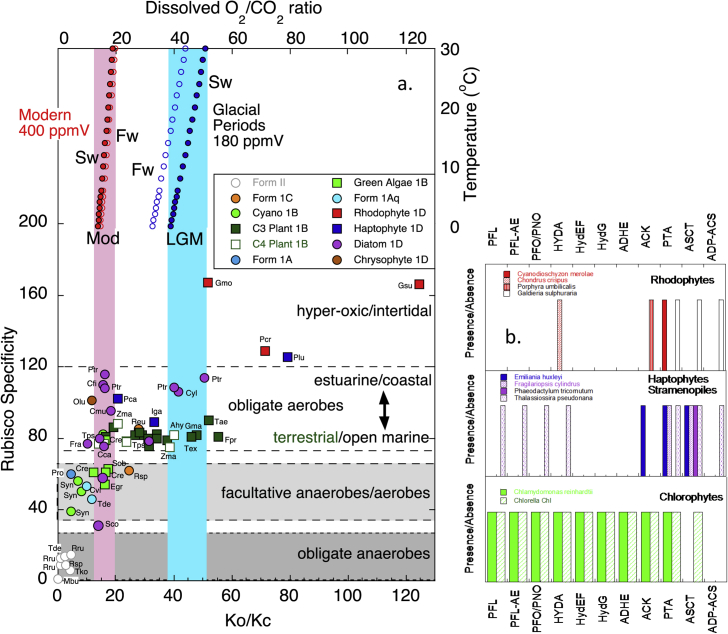

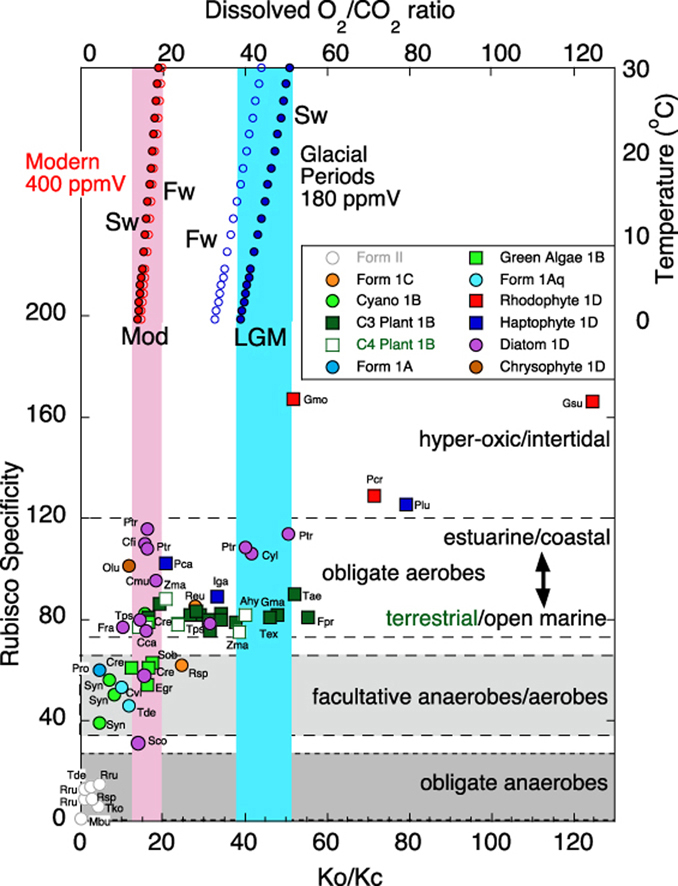

RuBisCO kinetic characterization from a diversity of organisms shows specificities that range from about 4 to 240 [[18], [19], [20], [21]]. As seen in Fig. 2, a replacement of Form IB-containing green algae and β-cyanobacteria across the ocean, by Form ID-containing haptophytes and heterokonts represents an approximate doubling in RuBisCO specificity [ [[18], [19], [20]], Supplementary Table 1] in the open ocean.

Fig. 2.

a) The sensitivity of the equilibrium dissolved ratio of O2/CO2 (CO2 [22]) (O2 [23]) concentrations to temperature and salinity (S; 0, open circles, and 35 ppt, closed circles) for the modern (with an atmosphere of 400 ppmV) compared to that at the LGM with invariant O2 but a CO2 atmosphere of 180 ppmV. This environmental O2/CO2 provides a calibration for the redox gradient to RuBisCO of different algal groups and their ecology showing the relative substrate affinities Ko/Kc of RuBisCO as a first order determinant of RuBisCO specificity. Species abbreviation labels Rhodophyta: Gsu Galdieria sulfiraria, Gmo Griffithsia monilis, Pcr Porphyridium cruentum, Haptophytes: Plu Pavlovale lutheri, Pca Pleurochrysis carterae, Iga Isochrysis galbana, Heterokonts: Phaeodactylum tricornutum, Cyl cylindrotheca spp, Cfu Cylindrus fusiformis, Cmu Chaetoceros muellerae, Chrysophyte: Olu Olisthodiscus luterae, Fra Fragilariopsis sp, Cca Chaetoceros calcitrans, Tps Thalassiosira pseudonana, Sco: Skeletonema costatum, Green algae: Cre Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Sob Scenedesmus obliquus, Egr Euglena gracilis, Cyanobacteria: Syn synechococcus, Pro Prochloroccus Plants: C3: Triticum aestivium C4 Zea Mays, Anaerobes: Tde Thiobacillus denitrans, Rsp Rhodobacter sphaeroides, Rru Rhodospirillum rubrum, Mbe Methanococcoides burtonii, Tko Thermococcus kodakarensis. Also labeled are mean ecologies of different groups of algae ranging from obligate anaerobes, through facultative anaerobes to obligate aerobes and hyperoxic tolerant. b) The number of anaerobic metabolic pathways in the genomes (PFL, PFL-AE, PFO/PNO, HYDA, HydEF, HydG, ADHE, ACK, PTA, ASCT, ADP-ACS) of the labeled organisms where RuBisCO specificity has also been determined taken from Atteia et al., [24]. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.).

4. Organisms with higher specificity RuBisCOs are selected by higher environmental O2/CO2

All else being equal, according to equation (2), an increase in the O2/CO2 ratio in the environment will decrease carboxylation relative to oxygenation for a given RuBisCO and net photosynthetic efficiency. Phytoplankton may adapt to such an environmental pressure by development of a carbon concentrating mechanism (CCM) to internally elevate CO2 relative to O2 around RuBisCO and restore net carbon fixation rates [[21], [22], [23]], by expression of a higher specificity RuBisCO should two different enzymes be available in the genome, or by improvement of their RuBisCO selectivity.

Many extant aquatic photosynthesisers possess a CCM [21,25,26]. Key constituents of the CCM include: (i) plasma- and chloroplast-membrane inorganic carbon transporters; (ii) a suite of carbonic anhydrase enzymes in strategic locations; and usually (iii) a microcompartment in the chloroplast in which most Rubisco aggregates (the pyrenoid) [20,27]. Generally, RuBisCO enzymes from algae have evolved a lower affinity for CO2 when the algae have adopted a strategy that employs a CCM to help optimise for CO2 fixation [20]. The phylogenetic progression in green RuBisCO kinetic properties suggest that RuBisCO substrate affinity for CO2 demonstrates a systematic relaxation in response to the origins and effectiveness of a CCM [27]. In land plants, it has been established that positive selection in rbcL emerges coincident with the development of a C4 CCM which elevates CO2 to almost saturation at the site of RuBisCO [28,29]. This relaxes pressure for RuBisCO to have a high affinity for CO2 so Kc of C4 plants is generally higher than the Kc of C3 plants. The development of a CCM masks any selective pressure exerted by rising external O2/CO2 on RuBisCO because it shields the enzyme within a high CO2 microenvironment. The extent of relaxation of selective pressure due to the presence of a CCM depends on its efficiency as there is great diversity in the structure and function of CCMs across the aquatic photosynthesisers.

Despite the prevalence of a CCM in aquatic photosynthesisers, there is considerable evidence that environmental O2/CO2 has frequently exerted a selective pressure on Rubisco specificity, or the use of a higher specificity Rubisco where two forms exist. A higher O2/CO2 ratio can induce the expression of a higher specificity RuBisCO in a single organism which harbours genes for two forms of RuBisCO of contrasting specificities (e.g. the more efficient Form 1C compared to the lower specificity Form II) such as within the non-sulphur purple photoautotrophic bacteria Rhodospirillum rubrum [30] and within the chemolithoautotrophic bacteria Thiobacillus denitrificans [31]. Generally, the use of the lower specificity Form II is selected under conditions of high CO2 (>1.5%) and low O2, in contrast to the induction of the higher specificity Form 1C during photoautotrophic growth at medium levels of CO2 (<1.5% CO2) and under more aerobic conditions [32].

The compilation of RuBisCO kinetics from extant photosynthesisers suggests that the O2/CO2 of the environment has also selected for organisms that express a higher specificity RuBisCO. There is a general correlation of RuBisCO specificity with Ko/Kc, the ratio of the relative affinities of RuBisCO for the O2 and CO2 substrates such that a high Ko (low affinity for O2) relative to a low Kc (high affinity for CO2) characterizes a highly specific RuBisCO and vice versa. This suggests that changes in relative carboxylation/oxygenation speeds (Vo/Vc) of the enzyme are small compared to changes in the relative affinities for the substrates. The Ko/Kc of the RuBisCO in modern marine phytoplankton appears to have adapted to compensate for the dissolved O2/CO2 ratio in the recent environment [33]. There is a close match between the Ko/Kc = ∼16 for most Form 1D-containing open ocean algae with red-algal derived plastids (e.g. haptophytes, heterokonts) and the modern dissolved O2/CO2 ratio in sea water (O2/CO2 ∼ 13 to 19 between 0 and 30 °C). In other words, RuBisCOs of these species display a 16-fold lower affinity for O2 than CO2 and thus appear to compensate for the 16-fold excess of dissolved O2 relative to CO2 (Fig. 2). It is not clear why there should be such an apparent tuning of the relative affinities of Rubisco to compensate for the modern environmental ratio of O2/CO2. One plausible mechanism may be the action of a CCM which acts to elevate the intracellular CO2/O2 and over time the relative substrate affinities of RuBisCO evolve in response to this compensating intracellular ratio.

This putative selective pressure exerted by environmental O2/CO2 on the RuBisCO Ko/Kc ratio may, paradoxically, also explain why some photosynthesisers have been found to have a Ko/Kc so extreme as to be apparently tuned to conditions outside the geologically recent range in atmospheric O2/CO2. During the ice ages of the Pleistocene, atmospheric CO2 concentrations have varied in parallel with the temperature fluctuations by ∼100 ppmV [34] but atmospheric O2 has stayed near constant [35]. The dissolved O2/CO2 has fluctuated from ∼13 to 19 in interglacials to ∼39 to 50 during glacial periods (Fig. 2 [33]). Compared to this range, the Ko/Kc of the 1D RuBisCO of two red algae (Porphyridium cruentum and Griffithsia monilis) and one coastal haptophyte (Pavlova lutheri) imply exposure to conditions of hyper-oxia compared to the “norm-oxia” of the modern ocean. Indeed, these species are known to inhabit brackish/intertidal zones which are susceptible to highly elevated O2/CO2 ratios during daylight hours when the rate of photosynthesis is high and water exchange may be limited [36]. Similarly the thermoacidophiles Cyanidium caldarium, Cyanidium partita and Galdiera sulfuraria likely experience high O2/CO2 ratios due to both temperature and pH effects on the relative solubilities of these gases in the hot acidic springs of their habitat. Furthermore, amongst the diatoms there is a huge range in specificities likely due to differences in their CCM [19] and their ecology. Some diatoms (Cylindrotheca fusiformis, and Phaeodactylum tricornutum) have higher specificities (∼110–120) than others. These species have a distinct ecology compared to diatoms reported with lower specificities (∼80), being found in coastal regions, estuaries, mud flats and rock pools compared to the lower specificity open ocean marine diatoms. These highly specific diatom RuBisCOs have a very high Ko relative to their Kc which may be a result of living in these more restricted hyperoxic coastal/intertidal zones, or even subaerially exposed, compared to open ocean conditions. Similarly two diatom strains of Skeletonema costatum, and Chaetoceros calcitrans have outstandingly low specificities (specificity of 30.3 and 56.7 respectively). These species are known to have resting stages that persist in oxygen-deficient sediments [37] for decades.

At the other extreme of the environmental scale, the form II RuBisCO of Methanococcoides burtonii, Thermococcus kodakarensis, Hydrogenovibrio marinus, T. denitrificans, Rhodobacter sphaeroides and Rhodospirillum rubrum is expressed only under anaerobic conditions i.e. with extremely low O2/CO2 ratios. Within this context, the lower Ko/Kc (4–8) of the cyanobacteria RuBisCO compared to the RuBisCO of green algae, haptophytes and heterokonts is consistent with the ability of the β-cyanobacteria to flourish under eutrophication. Such an observation may be supported by the correlation of abundance of microbial carbonates in the geological record with inferred periods of a more poorly oxygenated ocean [38].

This analysis reveals that organisms containing the 1D Form RuBisCO within the chlorophyll a+c algae are better adapted to an open ocean environment with an O2/CO2 ratio (∼16 to 35) that is approximately double that to which the RuBisCO of the cyanobacteria appears to be adapted (O2/CO2 ratio of 4– to 8). This further supports the hypothesis that a step change in upper ocean oxygenation contributed to the changing success of these different algal groups across the Paleozoic/Mesozoic boundary. Should the cyanobacteria Ko/Kc be tuned to the Paleozoic dissolved O2/CO2 ratio in the oceans, before the haptophytes and heterokonts took over then atmospheric compositions at that time, could have fluctuated around 10 to 20% O2 and 400 to 800 ppm CO2 when cyanobacteria were dominant. Even if this link between the Ko/Kc and the O2/CO2 of the environment is only qualitative, the Ko/Kc does provide some indication of ecological O2/CO2 ratios and is a first order determinant of RuBisCO specificity.

5. Higher specificity RuBisCOs are selected by organisms with aerobic physiology

In addition to environmental O2/CO2 ratios exerting a selective influence on organisms harbouring different specificity RuBisCOs, there is also a correlation between the physiological adaptation of the photosynthetic organism to aerobic/anaerobic conditions and RuBisCO specificity (Fig. 2). Obligate anaerobes, or facultative anaerobes which express a form II RuBisCO under anaerobic conditions, all have the lowest RuBisCO specificities (between 1 and 16). There is then a distinction between a group containing the higher specificity 1B land plants and 1D containing haptophytes and heterokonts (obligate aerobes) with a specificity between 80 and 120, compared to the group containing the 1B containing green algae and cyanobacteria (facultative anaerobes) with a specificity between 30 and 60. When investigating the differences between these photosynthesizing organisms, a distinctive physiology for the green algae and cyanobacteria emerges compared to other oxygenic autotrophs. They all have the ability to undergo indirect water photolysis to generate H2 if grown under anaerobic or low sulfate conditions. Anaerobic metabolic pathways allow unicellular organisms to tolerate or colonize anoxic environments. Green algae, such as Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, and Scenedesmus obliquus, all have the ability to ferment their plastidic starch to a variety of end products including acetate, ethanol, formate, glycerol, lactate, H2 and CO2. Cyanobacteria, depending on the species, utilize both nitrogenases and hydrogenases in the pathway of H2 production [39], whereas the green algae rely solely on hydrogenases [40]. Nitrogenases have the advantage that they act unidirectionally, whereas hydrogenases are bidirectional [41]. The high O2 sensitivity of both enzymes requires the separation of H2 evolution and CO2 fixation, temporally or spatially.

An overview of the presence of anaerobic metabolic pathways from whole genome analysis confirms such a gradient to the O2 tolerance of these physiologies ([24]; Fig. 2b). The red algae may be considered an “oxic” endmember to the algae. They are nearly devoid of any of the pathways involved in anaerobic metabolism. They also appear to have undergone a significant genome reduction in their evolutionary history, which could be responsible for the loss of the ancestral anaerobic pathways from the primary endosymbiosis [42]. Similarly the haptophytes and heterokonts are also lacking many of the anaerobic metabolic genes found in the green algae. In a parallel to the large diversity of diatom RuBisCO specificity, the greatest diversity in anaerobic gene presence is also found among the diatoms. By contrast, many green algae have an abundance of anaerobic pathways. Some were lost via gene reductions (such as in Ostreococcus tauri), but C. reinhardtii is adapted to both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. In a survey on different algal groups, redox-regulation of some parts of the Calvin Benson Cycle was also found to be variable with the greatest degree of regulation in green algae, but there was little or no redox-regulation in a red alga or in most lineages with red-algal derived plastids (including the diatoms) [43].

It was from within the Chlorophyte green algae, through the sister group of the Charophyte green algae, that the land plants emerged with their facultative anaerobic metabolism capable of living on land and becoming truly complex multicellular organisms (defined by three-dimensional body plans and multiple cell types). Meanwhile the red algal lineages have been limited in stature, multicellularity and ability to make roots [44] and were restricted to marine environments. The first steps onto land would have required the ability to differentiate cells to make roots to obtain nutrients from sediments or soils in periodically inundated and anoxic soils (e.g. Refs. [45,46]). Indeed it may have been the cellular differentiation into roots/shoots versus leaves harbouring RuBisCO that allowed the physical segregation between the anaerobic metabolic pathways in the roots and the chloroplasts containing RuBisCO in the leaves that allowed the plant RuBisCOs to make the step change towards a higher RuBisCO specificity, indicative of an aerobic environment, in the leaves.

6. Direction of evolution of RuBisCO specificity and nutrient requirement for a CCM

Eukaryotes with a green plastid possess Form IB Rubisco thought to have arisen through endosymbiosis of a Form IB containing cyanobacteria. Within this lineage therefore, the Form 1B RuBisCO improved its specificity in response to increasing O2/CO2 ratios over time, as seen in the land plants compared to the green algae and cyanobacteria. The emergence of a CCM was required to generate high intracellular CO2/O2 to maintain photosynthetic efficiency with the poorer specificity RuBisCO found in the cyanobacteria. These CCMs arose relatively late in geological time, ∼420 Ma, after CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere and ocean declined from their initially high levels and dissolved O2 levels rose [33,47].

It is hard to decipher the direction of evolution of the kinetics of RuBisCO within the form 1D RuBisCO containing lineages. Eukaryotes with a red plastid have Form ID that was originally derived from a γ-proteobacteria [9]. The red algae putatively diverged from the eukaryote tree of life ∼1.1 billion years ago and provided the plastids in the secondary endosymbiotic event that gave rise to the heterokonts and haptophytes. Did the haptophytes and heterokonts inherit a relatively low-specificity RuBisCO from the ancestral rhodophyte via secondary endosymbiosis, which has been retained in most extant haptophyte/heterokont species? Was a lower specificity RuBisCO of the haptophytes and heterokonts then shielded from the evolving environment by emergence of CCM pathways in response to rising O2/CO2? Did this lower specificity RuBisCO then become more specific in other species, such as Pavlova lutheri, that lack a CCM and inhabit higher O2/CO2 environments? An increase in RuBisCO specificity in the Pavlovales may have occurred concurrently with the selection of a higher RuBisCO specificity in red algae (as Fig. 2 shows P. lutheri has closest Ko/Kc to the red algal species). Alternatively, did the haptophytes and stramenopiles inherit an already highly specific RuBisCO from the rhodophytes, which then relaxed under the persistent induction of a CCM elevating internal CO2/O2 in the haptophytes and heterokonts (as proposed by Young et al. [48])?

Regarding the direction of evolution of RuBisCO specificity in the different lineages, three lines of evidence suggest that the latter hypothesis may be the more likely scenario i.e. that the haptophytes and stramenopiles inherited an already highly specific RuBisCO which then relaxed in specificity over time. Firstly, the ancient fossil record of the red algae, Bangiomorpha, places them as continuous inhabitants of the hyperoxic peri-to supra-tidal environment [49]. The peri-tidal zone is distinct for harbouring hyperoxic conditions of elevated O2 and much diminished CO2 concentrations during daily light-driven photosynthesis [36], and the supratidal zone sees highly elevated atmospheric O2/CO2 ratio with million fold faster diffusion rates. Another representative of the red algae, the Porphyra and its ancestors, have competed successfully in this dynamic and severe intertidal environment for over a billion years [44]. Similarly, the relatively morphologically simple Pavlovales have always been restricted to near-shore, brackish, or freshwater environments often with semibenthic modes of life, and this may mirror the ancestral ecological strategy of the Paleozoic haptophytes [5]. Even under a poorly oxygenated atmosphere, it is likely that these restricted coastal zones where photosynthesis was rife were consistently hyperoxic. Over this billion year timeframe, these hyperoxic conditions exerted a selection pressure beyond that of typical ocean conditions and selected for RuBisCOs that were better adapted to these rather more extremely oxygenated conditions, a trait inherited by the secondary endosymbiotic lineages. To obtain a competitive edge in this environment, algae could have additionally induced a CCM. It is through the persistent induction of a CCM to elevate internal CO2/O2 ratios that eventually the RuBisCO specificity relaxed during the speciation events that founded the lineages including the haptophytes and heterokonts.

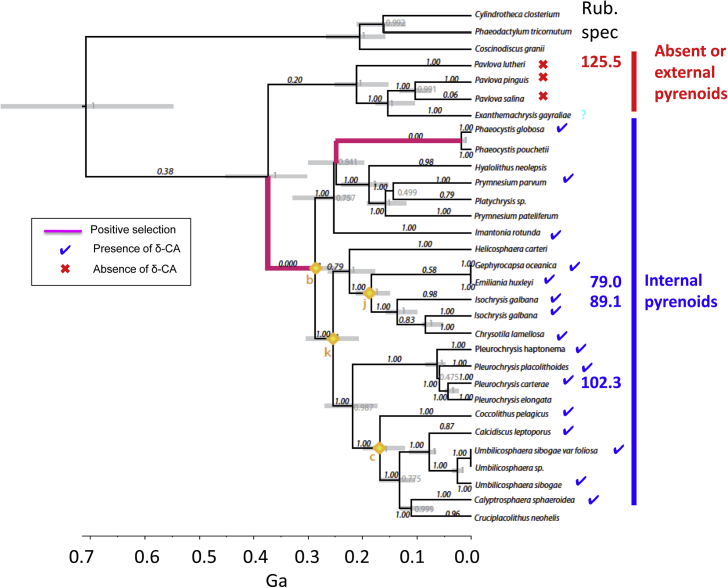

The strongest signal of positive selection in haptophyte RuBisCOs is at the divergence between the Pavlovophycaeae and Prymnesiophycaeae [48] with a step change in RuBisCO specificity (from 125 to 90) between respective representatives P. lutheri and I. galbana (Fig. 3). Distinct differences in RuBisCO specificities within the haptophyte lineage RuBisCO correlate with the formation of a pyrenoid and/or presence of a CCM [20]. Pavlova lutheri has a low cellular affinity for carbon, negligible change in this affinity when adapted to high or low external carbon conditions (Rae et al., unpubl data) and lacks a pyrenoid [50,51], suggesting that it has no CCM [20]. By contrast both Isochrysis galbana and Pleurochrysis carterae contain a pyrenoid [50,64,67] and are known to possess CCMs (including carbonic anhydrases) and lower specificity RuBisCOs compared to P. lutheri.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic Tree for RbcL within Haptophyta showing branches under positive selection (magenta) and those with no positive selection (black) adapted from Young et al., [48]. Black numbers above branch is statistical significance (p-value) of positive selection after a likelihood ratio test comparing nested models and using Bonferroni correction. Grey bars denote 95% confidence intervals for date estimates and grey numbers are posterior probability values. Yellow diamonds with corresponding letter are fossil calibration dates. Also indicated is the presence/absence of some components of a CCM with a blue tick for the presence of a δCA (methodology from Heureux et al. [20]), and a red bar for the absence or presence (blue) of a pyrenoid (Eason Hubbard unpublished; P. lutheri (now Diacronema lutheri) [50,51] Pavlova pinguis [52,53], Pavlova salina (now Rebecca salina) [51,53], Exanthemachrysis gayraliae [51,54], Phaeocystis globosa [55], Phaeocystis pouchetii [56], Hyalolithus neolepis (now Prymnesium neolepis) [57], Prymnesium parvum [58], Prymnesium patelliferum (now Prymnesium parvum haploid stage) [59], Imantonia rotunda (now Dicrateria rotunda) [60], Gephyrocapsa oceanica [61], Helicosphaera carteri (Eason Hubbard unpubl), Emiliania huxleyi [62,63], Isochrysis galbana [64], Chrysotila lamellosa [65], Pleurochrysis placolithoides [66], Pleurochrysis carterae [67], Pleurochrysis elongate [68], Coccolithus pelagicus [69], Calcidiscus leptoporus (Eason Hubbard unpubl), Umbilicosphaera sibogae var foliosa [70], Calyptrosphaera sphaeroidea (now Holococcolithophora sphaeroidea) [71], Cruciplacolithus neohelis [72]. Also indicated is the RuBisCO specificity in numerical values where data is available. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

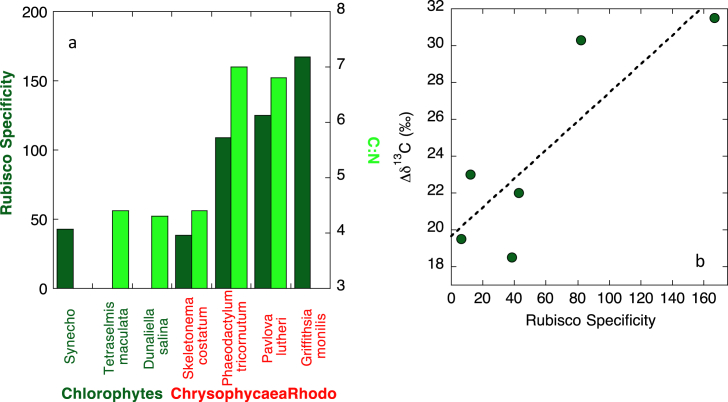

The winners of the competition for success in the open ocean then derives from the nutrient efficiency with which algal lineages can maintain high rates of carboxylation relative to oxygenation. Across a rise in ocean O2/CO2 at the Mesozoic, as a result of their poorer RuBisCO specificity, β-cyanobacteria need to invest greater nutrient resource in fixing carbon via a more efficient CCM than the haptophytes and heterokonts with a more highly specific RuBisCO and lesser need of investment in proteins for a CCM to succeed within this niche. A hint of this higher nutrient requirement for C fixation in species with a lower RuBisCO specificity is afforded by a comparison of the Redfield ratio of a range of species measured under identical laboratory conditions in the same study (Fig. 4a). There is such plasticity to the Redfield ratio that direct comparison across a broad range of species from the exact same conditions is the only way to obtain a direct comparison. If a higher C:N reflects a higher efficiency C fixation process per protein expressed, then species with higher RuBisCO specificities indeed obtain greater C fixation rates per nitrogen fixed as a result of requiring less proteins for the CCMs. In addition, green seaweeds from the upper intertidal zone but same location have been found to have lower C:N ratios (∼10) than both red (∼13) and brown seaweeds (∼16) for the lower intertidal zone [76] suggestive that these different Redfield ratios may be more broadly characteristic of these algal lineages. Upon oxygenation and increasing oligotrophy of the open ocean, haptophytes and heterokonts could outcompete the green algae and β-cyanobacteria in terms of net carboxylation relative to oxygenation per nutrient required.

Fig. 4.

a) Comparison between RuBisCO specificity (dark green bars) and the Redfield ratio (C:N measured in cells under exponential growth, light green bars [73]). These are data measured on a wide variety of species under the exact same conditions, important for internal consistency given the propensity for plasticity in the Redfield ratio. Here the Redfield ratio is interpreted to reflect nutrient efficiency of C fixation and C:N is higher when carbon fixation is more nutrient efficient and requires less proteins of a CCM. B) The relationship between higher RuBisCO specificity and larger carbon isotopic fractionation of the RuBisCO enzyme in vitro taken from Tcherkez et al. [74], and updated with data for S. costatum from Boller et al., [75]. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.).

Such nutrient selection and open ocean or coastal selection of CCM efficiency is evident amongst the different groups of cyanobacteria, compensating for a lesser RuBisCO efficiency. The open ocean α-cyanobacteria with form IA RuBisCOs have a restricted suite of HCO3− accumulation processes and little capacity to acclimatize to decreased inorganic C availability [47,77,78] The oceanic α -cyanobacteria may have developed a physiology where they may not have the ability to acquire or induce high-affinity carbon transport systems, and in some species no active CO2 uptake system may be present which makes them nutrient efficient and well adapted to the open ocean. On the other hand, many β-cyanobacteria have the ability to induce various CO2 and HCO3− transport systems as their environmental conditions change [47,77,78] and so flourish in coastal nutrient rich zones. Indeed the sensing of oxygen may play a key role in the induction of a CCM in the cyanobacteria [79].

It is worth noting that this consideration above yields contrasting nutrient gradients for CCMs to succeed in different O2/CO2 environments between the chlorophyte and chromalveolate lineages. Amongst the green algae with a poorly specific RuBisCO, a great energetic or nutrient investment in a CCM is necessary to inhabit conditions of elevated O2/CO2. By contrast, amongst the haptophytes and heterokonts, the greater nutrient requirement for a CCM, which over time relaxes RuBisCO specificity, allows them to extend their ecology into lower O2/CO2 environments.

A second argument to support the red algae having consistently expressed high specificity RuBisCOs rather than evolving towards a higher specificity RuBisCO under rising O2/CO2 comes from C isotopic fractionation. A more highly specific RuBisCO binds the CO2 substrate more tightly and thus results in a larger kinetic fractionation associated with C fixation compared to a lower specificity RuBisCO ([74], Fig. 4b). The larger C isotopic swings of oceanic δ13C in the Neoproterozoic which dampen towards the modern day [80] could either reflect variations in the burial rate of isotopically light carbon (e.g. Ref. [81]) or burial of different sources of organic carbon with more extreme C isotopic signatures than those of the modern day. If burial of organic matter oscillated between the much lighter isotopic carbon produced by the highly specific RuBisCO in the coastal Pavlovales and or Porphyra, and the much isotopically heavier organic matter of the cyanobacteria [82], this could contribute to the higher amplitude oscillations of the early part of the δ13C record (see Figure 2c of [81]). The oceanic δ13C oscillations became damped as CCMs were induced and the more intermediate specificity RuBisCOs of the terrestrial plants, haptophytes and heterokonts became increasingly prevalent throughout the Phanerozoic contributing to burial of organic matter with less extreme carbon isotopic compositions due to the smaller isotopic fractionations factors of these more intermediate specificity RuBisCOs. There are hints that some seaweed δ13C and P. lutheri δ13C may be extremely isotopically light [83,84] which could be consistent with a large carbon isotope discrimination factor of a highly specific RuBisCO.

Thirdly, there is little difference in RuBisCO specificity between the cyanobacteria (the primary endosymbiont) and the chlorophyte green algae nor between the red alga, P. cruentum (a putative secondary endosymbiont) and the haptophyte P. lutheri suggestive that the ancestor of the endosymbiont and secondary lineages bearing that endosymbiont are similar in their RuBisCO specificity. Furthermore, the positive selection and change in RuBisCO specificity are coincident at the speciation events [48]. This might suggest that the process of endosymbiosis itself did not change the specificity, and that it was the later environmental change around the RuBisCO that effected a change in the RuBisCO of the land plants and that of the haptophytes and heterokonts.

7. Tempo of evolution of RuBisCO kinetics

7.1. Slow to generate specificity

Despite the general correlation of RuBisCO specificity with relative substrate affinity across the continuum of change in Ko/Kc, there are discrete groups of RuBisCO specificities characterized by a range of Ko/Kc values (Fig. 3). This is suggestive that Ko/Kc may evolve very quickly, and in response to environmental or physiological conditions, but a change in specificity takes much longer. If net carboxylation is the single rate-limiting step for the growth and replication of a single-celled photosynthesizing microorganism, then strong positive selection will be exerted upon the enzyme that catalyzes this step i.e. RuBisCO. A strong selection pressure from an increasing O2/CO2 at the active site can impart drastic improvements in a short period of time, yielding an evolved enzyme that is no longer the weak link in the metabolic network of the cell, hence step changes in specificity [85]. Once that link is no longer the weakest, selection pressure shifts to another point in that physiological pathway such as the proteins of the CCM.

For a particular RuBisCO specificity, a CCM may be responsible for some of the variance in the Ko/Kc due to its ability to boost the internal CO2/O2 ratio and maintain photosynthetic rates in the face of rising environmental O2/CO2. Although a CCM relaxes pressure for RuBisCO to have a high affinity for CO2 so Kc of C4 plants is generally higher than the Kc of C3 plants, but curiously there is no difference to the specificity of the RuBisCOs between the C3 and C4 plants despite the presence of a CCM. The higher Kc of the C4 plants is accompanied by a higher Ko presumably due to a relaxation in the binding for both substrates at the active site. Further, a more relaxed active site for each substrate, turns over those substrates faster so C4 plants require less nitrogen to achieve a given CO2 fixation capacity. But due to these correlative biochemical constraints, a CCM appears to yield no change in specificity over relatively short timescales.

In comparison, when considering the largely CCM-lacking Pavlovophyceae with the CCM-bearing Prymnesiophyceae of the haptophyte lineage, it is evident that the evolution of a CCM in the latter has both altered the substrate affinities and relaxed the specificity of the RuBisCO enzyme (Fig. 3). A possible explanation for the difference between the evolution of specificity in RuBisCOs of the haptophyte lineage and the C3/C4 plants is that it takes a long time to accumulate sufficient mutations to effect a change in RuBisCO specificity, on the order of 100s of millions of years. The signal of positive selection in haptophyte RuBisCOs at the branch between the Pavlovophyceae and Prymnesiophyceae [48] is dated to between 300 and 400 Ma. The step change in 1B RuBisCO specificity accompanies the divergence between the filamentous green algae and the land plants around 410 Ma, so about 200 Myrs after the rise to dominance of the chlorophytes ∼650 Ma [3]. By contrast, C4 plants have only been present for the last ∼30 Myrs [86]. It seems to take >100 Myrs to accumulate sufficient mutations to evolve an improved functional RuBisCO specificity.

These step changes in the RuBisCO specificity align with analyses of gene sequence for the RbcL gene across the algal phylogenies that find evidence for positive selection in the gene sequence clustered only at the base of the divergence of the modern algal lineages [48]. So RuBisCO undergoes major changes at the establishment of the haptophyte, and heterokont groups relative to the red algae [48]. This is consistent with the former use of RbcL genes for phylogenetic reconstruction i.e. as a species specific marker.

7.2. Fast evolution of Ko/Kc

By contrast, manipulations of the environment or intracellular O2/CO2 appear to yield changes to the RuBisCO substrate affinities at rates as fast as the timescale of decades. Assuming that the relative substrate affinity for RuBisCOs compensate for environmental O2/CO2 as proposed in Ref. [33], this timescale for adaptation derives from the degree to which these affinities appear to have kept pace with the documented changes in the environment. The Ko/Kc of most C3 and C4 plants cluster at a level that could compensate for a Pleistocene glacial period when there was an excess of O2/CO2 between 39 and 50 fold (Fig. 2), or somewhere in between the extrema of the glacial-interglacial variance. It is reasonable to compare plant RuBisCO kinetics to dissolved gas ratios since RuBisCO experiences those substrates in a dissolved state. The Ko/Kc of algal RuBisCOs appear better tuned to current conditions (O2/CO2 ratio of 13–19), a dissolved ratio that is lower than that experienced during the last 1 million years of the Pleistocene glacial cycles because of the anthropogenic rise in pCO2 over the last two centuries. Consequently the fine-tuning of RuBisCO's relative affinity for substrates appears to evolve in response to environmental change over timescales of tens of kyrs in the plants, and hundreds of years in the algae. This observation supports the emerging view that RuBisCO may be optimized to its environment [74]. Its kinetic performance can even be classified as moderately efficient when compared to a global overview of enzyme kinetic rates [[87], [88], [89]].

Adaptation processes may work differently in relatively small, subdivided populations of terrestrial organisms and astronomically large populations of marine phytoplankton inhabiting a fairly homogenous environment. Population size is one of the most important parameters that determines the amount of new genetic variation introduced into a population via mutation (the more individuals, the more copies of a gene in a population to mutate every generation), as well as the dynamics of spread and loss of the mutations by chance or selection [90]. It has further been shown that molecular evolution is proportional to generation time in plant lineages and microbial lineages [91,92]. Perennials, with longer generation times, have been shown to accumulate substitutions more slowly than rapidly maturing annual plants. It is likely therefore that the substrate affinity of algal RuBisCOs can be fine tuned to environmental change more quickly and potentially keep pace with anthropogenically diminishing O2/CO2 ratios, compared to the slower evolving plant RuBisCOs which appear to be stuck in glacial times. The rate of evolution of algal RuBisCOs is potentially orders of magnitude faster than that of plants due to their small generation time compared to that of plants. There is a hint that some diatom species (two strains of P. tricornutum and C. fusiformis) are also better adapted to glacial O2/CO2, potentially due to longer generation times as a result of resting spore formation, akin to the slower evolution rates in spore-forming bacteria.

8. Implications for optimizing photosynthesis

Photosynthesisers have evolved two strategies for achieving similar rates of net carboxylation at a given environmental O2/CO2. The evolution of a CCM maintains a more ancient O2/CO2 ratio, shielding the RuBisCO against the environment and keeping a lower specificity RuBisCO competitive for carboxylation (e.g. the cyanobacteria whom likely increase internal CO2 10-fold above the environment) but at an additional nutrient cost. By contrast, the CCM lacking species succumb to the selection pressure of the environmental O2/CO2 resulting in a more specific RuBisCO (e.g. the coastal P. lutheri).

Given sufficient time (100s of millions of years), the persistent expression of a CCM reduces the specificity of RuBisCO so a natural limit emerges as to how far net carboxylation, and RuBisCO can improve, within the bounds of evolution. The brown algae, which diversified between 150 and 200 Ma, live ecologically at greater elevation relative to the tide than the red algae. They are distinct for employing iodinated peroxidases [93] which suggests that their more recent divergence has allowed them to take advantage of the rise in ocean iodate documented by the carbonates [7] as part of their antioxidant strategy, and they are well adapted to high O2/CO2. The brown algae could harbor the Rolls Royce of RuBisCOs, currently limited to this supratidal zone of hyperoxic conditions and are a worthy candidate of characterization of RuBisCO kinetics in the quest to find the most efficient RuBisCO.

At the other end of the spectrum, the cyanobacteria and green algae appear to have a RuBisCO which, as a bare enzyme, is poorly optimized for the modern oxygenated environment. Within the β-cyanobacteria, an exceptional CCM has evolved including the carboxysome (e.g. Ref. [94]) that compensates for the low specificity RuBisCO. But given that better RuBisCOs exist, has the improvement of RuBisCO within the cyanobacteria been limited by some other factor? It has been speculated that a first Calvin cycle might have evolved from ancient nucleotide metabolism and initially served in redox cofactor balancing and/or mixotrophy, before developing autotrophic function [11]. The 1B form of RuBisCO has also been invoked to be involved in anaerobic methionine sulphur salvage metabolism with the suggestion that the active site of RuBisCO has evolved to insure that this enzyme maintains both key functions [95]. Each of these RuBisCO functions may be lost with an evolution to a higher specificity RuBisCO. As a result the green algal and cyanobacteria RuBisCO may be limited to lower intracellular redox conditions that allows the maintenance of some anaerobic pathways to enable success in environments of fluctuating oxygenation.

9. Geological implications

A prolonged increase in dissolved ocean or intracellular O2/CO2, can precipitate rapid change in the RuBisCO enzyme. Although it is tempting to speculate that improvements in RuBisCO might increase carbon fixation rates and oxygen production rates and set the atmospheric composition [96], the majority of change in RuBisCO is an adaptation to an environment which is less favourable to net carboxylation. Any adaptation in terms of specificity and/or induction of a CCM helps sustain carboxylation rates as the environment O2/CO2 becomes less favourable.

In terms of the ocean atmosphere budget of CO2 and O2, it is likely that the ratio underwent distinct step changes through geological history. The two atmospheric gases are inversely linked via the burial of carbon in its reduced organic carbon form, the dominant geological driver, that acts to decrease CO2 at the same time as driving O2 increase. An interrogation of a recent compilation of Phanerozoic δ13C of the ocean points towards a first order monotonic rise in ocean δ13C through the Palaeozoic indicative of an increasing proportional burial of organic carbon relative to carbonate peaking with the heaviest δ13C of the Phanerozoic ocean between 250 and 200 Ma [80,81]. The increase throughout the Paleozoic towards the Mesozoic parallels the tectonically paced aggregation of the Pangaean supercontinent and its migration away from the poles towards the low latitudes. It is likely then that either a large area of low latitude continental shelf buried a significant proportion of reduced carbon, or the amalgamation of plates uplifted significant shelf organic carbon onto the continents and out of the geological carbon cycle. Alternatively, submarine fans that accumulate during mountain erosion are efficient at burying large quantities of organic carbon from a vegetated land surface [97]. Pangaea was the first time in geological history that the continents amalgamated, contained significant mountains after plate collision and were covered by terrestrial biota. This maximal sink of organic carbon could have shifted the redox balance of the atmosphere/ocean towards a final rise in atmospheric O2 and lowered CO2. It may have been this peak organic carbon burial that tipped the environmental balance in the surface ocean towards the chlorophyll c containing lineages and propagated the positive feedbacks towards deepening OMZs, increasing pH and enhanced oligotrophy. There is a hint that the first sedimentary evidence for the coccolithophores (∼220 Ma), and the biomarker change may have predated the deepening of the OMZ by ∼ 20 million years (Fig. 1 [98]).

9.1. The deepening of the OMZs

A small trigger such as those described above can easily propagate to a large selective force by a positive feedback and co-evolution between the environment and phytoplankton physiology at the start of the Mesozoic. An increase in the redox or Eh of the upper ocean, or a deepening of an OMZ goes hand in hand with an increase in pH of the surface ocean [99] due to the deepening of the oxidative remineralisation of organic matter. So this persistent oxygenation of the upper waters also accompanied a persistent alkalinisation of the surface ocean helping the advent of mineralised skeletons and carbonate buffering of the deep ocean [100]. There is a positive feedback between the deepening of the oxygen minimum zone due to the enhanced ballast [7,101], increased alkalinisation of the surface ocean, aiding calcification and contributing to the persistent oxygenation. Such ballasting also deepens nutrient remineralisation leaving the surface ocean increasingly depleted - a condition less tolerated by the more nutrient hungry cyanobacteria and green algae that flourish under eutrophication than the nutrient-lean red algae. Concurrently the macro fauna themselves may not just be recipients of additional energy, but by their change in lifestyle as a result of the increasing transfer of nutrients from the lower echelons of the ecosystem they may also be implicit in driving the deepening of the OMZs and oxygenation of the upper ocean by their daily vertical migration [102]. There is a feedback loop between deepening OMZs, persistent oxygenation, alkalinisation, and oligotrophy which once set in motion creates an aggravating selective force towards the mineralising coccolithophores and diatom success over the incumbent green algae setting the scene for the advent of the modern ocean and its biota.

10. Conclusions

The different photosynthetic lineages, and their expressed RuBisCO specificities appear to evolve from contrasting redox endmembers towards similar “redox poise” under modern oxygenated conditions. The view of RuBisCO kinetic data, here, and the fossil record suggests that the red algae and other lineages with red algal-derived plastids (e.g. haptophytes, heterokonts) with a superior RuBisCO specificity were restricted to the oxic intertidal oasis through the Paleozoic. A step change in upper ocean oxygenation, enhanced oligotrophy, and elevated surface ocean pH at the start of the Mesozoic allowed them to inundate the open ocean. By contrast, the β-cyanobacteria and green algae with a greater nutrient requirement to support the CCM supply of carbon for their lesser specificity RuBisCO were restricted to the nutrient rich coastal ocean. This photosynthetic strategy is better adapted to fluctuating anoxic conditions which may have been a key to their successful invasion of the land through periodically inundated and anoxic soils. We explore the tempo of adaptation within RuBisCO kinetics to changing environmental O2/CO2 ratios and show that evolution of a CCM, at a nutrient cost, acts to relax RuBisCO efficiency and so imposes a natural limit to the improvement of RuBisCO over Earth's history.

Acknowledgments

REMR is grateful to the ERC Starting Grant (SP2-GA-2008-200915), ERC Consolidator Grant (681746) and a Wolfson Research Merit Award from the Royal Society, UK for financial support of this work on RuBisCO and for the incredible work and discussions of the GRACE team including Ana Heureux, Jodi Young, Ben Rae, Renee Lee, Harry McClelland and collaborator Spencer Whitney and Rob Sharwood at ANU. The manuscript has benefitted from discussions with Nick Butterfield, Steven Kelly, Emily Flashman, Simon Conway Morris, Erdem Idiz, Rachel Wood and Sinead Collins.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.05.006.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Kodner R.B., Pearson A., Summons R.E., Knoll A.H. Sterols in red and green algae: quantification, phylogeny, and relevance for the interpretation of geologic steranes. Geobiology. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2008.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwark L., Empt P. Sterane biomarkers as indicators of Palaeozoic algal evolution and extinction events. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2006;240:225–236. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brocks J.J., Jarrett A.J.M., Sirantoine E., Hallmann C., Hoshino Y., Liyanage T. The rise of algae in Cryogenian oceans and the emergence of animals. Nature. 2017;548:578–581. doi: 10.1038/nature23457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falkowski P.G., Katz M.E., Knoll A.H., Quigg A., Raven J.A., Schofield O., Taylor F.J.R. The evolution of modern eukaryotic phytoplankton. Science. 2004;305:354–360. doi: 10.1126/science.1095964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Vargas C., Aubry M.P., Probert I., Young J. The origin and evolution of coccolithophores: from coastal hunters to oceanic farmers. In: Falkowski P.G., Knoll A.H., editors. Evolution of Primary Producers in the Sea. Elsevier Academic; Amsterdam: 2007. pp. 251–286. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knoll A.H., Summons R.E., Waldbauer J., Zumberge J. The geological succession of primary producers in the oceans. In: Falkowski P., Knoll A.H., editors. The Evolution of Primary Producers in the Sea. Elsevier; Burlington, MA: 2007. pp. 133–163. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu W. Late inception of a persistently oxygenated upper ocean. Science. 2018 doi: 10.1126/science.aar5372. eaar5372, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grantham P.J., Wakefield L.L. Variations in the sterane carbon number distributions of marine source rock derived crude oils through geological times. Org. Geochem. 1988;12:61–77. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tabita F.R., Satagopan S., Hanson T.E., Kreel N.E., Scott S.S. Distinct form I, II, III, and IV Rubisco proteins from the three kingdoms of life provide clues about Rubisco evolution and structure/function relationships. J. Exp. Bot. 2008;59(7):1515–1524. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kacar B., Hanson-Smith V., Adam Z.R., Boekelheide N. Constraining the timing of the great oxidation event within the Rubisco phylogenetic tree. Geobiology. 2017 doi: 10.1111/gbi.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erb T.J., Zarzycki J. A short history of RubisCO: the rise and fall (?) of Nature's predominant CO2 fixing enzyme. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018;49:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker T.S., Eisenberg D., Eiserling F.A., Weissman L. The structure of form I crystals of -ribulose-1,5-diphosphate carboxylase. J. Mol. Biol. 1975;91:391–398. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90267-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morse D., Salois P., Markovic P., Hastings J. A nuclear-encoded form II RuBisCO in dinoflagellates. Science. 1995;268:1622–1624. doi: 10.1126/science.7777861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spreitzer R.J., Salvucci M.E. Rubisco: structure, regulatory interactions, and possibilities for a better enzyme. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2002;53:449–475. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.100301.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pichard S., Campbell L., Paul J. Diversity of the ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase form I gene (rbcL) in natural phytoplankton communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997;63:3600–3606. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3600-3606.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tabita F.R. Microbial ribulose 1,5-Bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase: a different perspective. Photosynth. Res. 1999;60:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersson I., Backlund A. Structure and function of Rubisco. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2008;46:275–291. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galmés J., Kapralov M.V., Andralojc P.J., Conesa M.À., Keys A.J., Parry M.A., Flexas J. Expanding knowledge of the RuBisCO kinetics variability in plant species: environmental and evolutionary trends. Plant Cell Environ. 2014;37:1989–2001. doi: 10.1111/pce.12335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young J.N., Heureux A., Sharwood R., Rickaby R.E.M., Whitney S.M. The variation in diatom RuBisCO kinetics reveals diversity in the efficiency of their carbon concentrating mechanisms. J. Exp. Bot. 2016 doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heureux A., Young J.N., Whitney S.M., Eason-Hubbard M.R., Lee R.B.Y., Sharwood R.E., Rickaby R.E.M. The role of RuBisCO kinetics and pyrenoid morphology in shaping the CCM of haptophyte microalgae. J. Exp. Bot. 2017;68:3959–3969. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Badger M.R., Hanson M., Price G.D. Evolution and diversity of CO2-concentrating mechanisms in cyanobacteria. Funct. Plant Biol. 2002;29:161–173. doi: 10.1071/PP01213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss R.F. Carbon dioxide in water and seawater: the solubility of a non-ideal gas. Mar. Chem. 1974;2:203–215. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benson B.B., Krause D. The concentration and isotopic fractionation of oxygen dissolved in freshwater and seawater in equilibrium with the atmosphere. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1984;29:620–632. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atteia A., van Lis R., Tielens A.G., Martin W.F. Anaerobic energy metabolism in unicellular photosynthetic eukaryotes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1827:210–223. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giordano M., Beardall J., Raven J.A. CO2 concentrating mechanisms in algae: mechanisms, environmental modulation, and evolution. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2005;56:99–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reinfelder J.R. Carbon concentrating mechanisms in eukaryotic marine phytoplankton. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2010;3:291–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer M., Griffiths H. Origins and diversity of eukaryotic CO2-concentrating mechanisms: lessons for the future. J. Exp. Bot. 2013;64:769–786. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christin P., Salamin N., Muasya A.M., Roalson E.H., Russier F., Besnard G. Evolutionary switch and genetic convergence on rbcL following the evolution of C4 photosynthesis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008;25:2361–2368. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kapralov M.V., Kubien D.S., Andersson I., Filatov D.A. Changes in Rubisco kinetics during the evolution of C4 photosynthesis in Flaveria (Asteraceae) are associated with positive selection on genes encoding the enzyme. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010;28:1491–1503. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dubbs J.M., Tabita F.R. Regulators of nonsulfur purple phototrophic bacteria and the interactive control of CO2 assimilation, nitrogen fixation, hydrogen metabolism and energy generation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2004;28:353–376. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beller H.R., Letain T.E., Chakicherla A., Kane S.R., Legler T.C., Coleman M.A. Whole-genome transcriptional analysis of chemolithoautotrophic thiosulfate oxidation by Thiobacillus denitrificans under aerobic versus denitrifying conditions. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:7005–7015. doi: 10.1128/JB.00568-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Badger M.R., Bek E.J. Multiple RuBisCO forms in proteobacteria: their functional significance in relation to CO2 acquisition by the CBB cycle. J. Exp. Bot. 2008;59:1525–1541. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffiths H., Meyer M., Rickaby R.E.M. Overcoming adversity through diversity: aquatic carbon concentrating mechanisms. J. Exp. Bot. 2017;68:3689–3695. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luthi D. High resolution carbon dioxide concentration record 650,000-800,000 years before present. Nature. 2008;453:379–382. doi: 10.1038/nature06949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stolper D.A., Bender M.L., Dreyfus G.B., Yan Y., Higgins J.A. A Pleistocene ice core record of atmospheric O2 concentrations. Science. 2016;353:1427–1430. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Truchot J.P., Duhamel-Jouve A. Oxygen and carbon dioxide in the marine intertidal environment: diurnal and Tidal Changes in Rockpools. Respir. Physiol. 1980;39:241–254. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(80)90056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McQuoid M., Godhe A., Nordberg K. Viability of phytoplankton resting stages in the sediments of a coastal Swedish fjord. Eur. J. Phycol. 2002;37:191–201. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riding R., Liang L., Lee J.-H., Virgone A. Influence of dissolved oxygen on secular patterns of marine microbial carbonate abundance during the past 490 Myr. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2018;51 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dutta D., De D., Chaudhuri S., Bhattacharya S.K. Hydrogen production by cyanobacteria. Microb. Cell Factories. 2005;4 doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-4-36. 36–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oncel S.S., Kose A., Faraloni C. Chapter 25 - genetic optimization of microalgae for biohydrogen production. In: Kim S.-K., editor. Handbook of Marine Microalgae. Academic Press; Boston: 2015. pp. 383–404. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Melnicki M.R., Pinchuk G.E., Hill E.A., Kucek L.A., Fredrickson J.K., Konopka A., Beliaev A.S. Sustained H2 production driven by photosynthetic water splitting in a unicellular cyanobacterium. mBio. 2012;3 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00197-12. e00197–00112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qiu H., Price D.C., Yang E.C., Yoon H.S., Bhattacharya D. Evidence of ancient genome reduction in red algae (Rhodophyta) J. Phycol. 2015;51:624–636. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maberly S.C., Courcelle C., Groben R., Gontero B. Phylogenetically based variation in the regulation of the Calvin cycle enzymes, phosphoribulokinase and glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase, in algae. J. Exp. Bot. 2010;61:735–745. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brawley S.H. Insights into the red algae and eukaryotic evolution from the genome of Porphyra umbilicalis (Bangiophyceae, Rhodophyta) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am. 114, 2017, E6361–E6370 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1703088114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Drew M.C. Oxygen deficiency and root metabolism: injury and acclimation under hypoxia and anoxia. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1997;48:223–250. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White M.D., Kamps J.J.A.G., East S., Taylor Kearney L.J., Flashman E.J. The plant cysteine oxidases from Arabidopsis thaliana are kinetically tailored to act as oxygen sensors. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:11786–11795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.003496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raven J.A., Cockell C.S., De La Rocha C.L. The evolution of inorganic carbon concentrating mechanisms in photosynthesis. Phil. Trans. Biol. Sci. 2008;363:2641–2650. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Young J.N., Rickaby R.E.M., Kapralov M., Filatov D. Adaptive signals in algal RuBisCO reveal a history of ancient atmospheric CO2. Phil. Trans, Roy. Soc. 2012;367:483–492. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Butterfield N.J. Bangiomorpha pubescens n. gen., n. sp.: implications for the evolution of sex, multicellularity, and the Mesoproterozoic/Neoproterozoic radiation of eukaryotes. Paleobiology. 2000;26:386–404. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Green J.C. The fine-structure and taxonomy of the haptophycean flagellate Pavlova lutheri (Droop) comb. nov. (= Monochrysis lutheri Droop) J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 1975;55:785–793. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bendif E.M., Probert I., Hervé A., Billard C., Goux D., Lelong C., Cadoret J.-P., Véron B. Integrative taxonomy of the Pavlovophyceae (Haptophyta): a reassessment. Protist. 2011;162(5):738–761. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Green J.C. The fine structure of Pavlova pinguis Green and a preliminary survey of the order Pavlovales (Prymnesiophyceae) Eur. J. Phycol. 1980;15(2):151–191. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Green J.C. Notes on the flagellar apparatus and taxonomy of Pavlova mesolychnon Van der Veer, and on the status of Pavlova Butcher and related genera within the Haptophyceae. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 1976;56:595–602. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gayral P., Fresnel J. Exanthemachrysis gayraliae Lepailleur (Prymnesiophyceae, Pavlovales): ultrastructure et discussion taxonomique. PROTISTOLOGICA. 1979;XV:271–282. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parke M., Green J.C., Manton I. Observations on the fine structure of zoids of the genus Phaeocystis (Haptophyceae) J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 1971;51:927–941. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jacobsen A. Morphology, relative DNA content and hypothetical life cycle of Phaeocystis pouchetii (Prymnesiophyceae); with special emphasis on the flagellated cell type. Sarsia. 2002;87:338–349. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yoshida M., Noël M.-H., Nakayama T., Naganuma T., Inouye I. A haptophyte bearing siliceous scales: ultrastructure and phylogenetic position of Hyalolithus neolepis gen. et sp. nov. (Prymnesiophyceae, Haptophyta) Protist. 2006;157:213–234. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Manton I., Leedale G.F. Observations on the fine structure of Prymnesium parvum Carter. Arch. Mikrobiol. 1963;45:285–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00406854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Green J.C., Hibberd D.J., Pienaar R.N. The taxonomy of Prymnesium (Prymnesiophyceae) including a description of a new cosmopolitan species, P. patellifera sp. nov., and further observations on P. parvum N. carter. Br. Phycol. J. 1982;17:363–382. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reynolds N. Imantonia rotunda gen. et sp. nov., a new member of the Haptophyceae. Br. Phycol. J. 1974;9:429–434. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bendif E.M., Young J. On the ultrastructure of Gephyrocapsa oceanica (Haptophyta) life stages. Cryptogam. Algol. 2014;35:379–388. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klaveness D. Coccolithus huxleyi (Lohmann) Kamptner. I., Morphological investigations on the vegetative cell and the process of coccolith formation. PROTISTOLOGICA. 1972;8:335–346. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Klaveness D. Coccolithus huxleyi (Lohm.) Kamptn II. The flagellate cell, aberrant cell types, vegetative propagation and life cycles. Eur. J. Phycol. 1972;7(3):309–318. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Green J.C., Pienaar R.N. The taxonomy of the order isochrysidales (Prymnesiophyceae) with special reference to the genera Isochrysis parke, Dicrateria parke and Imantonia Reynolds. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 1977;57:7–17. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Green J.C., Parke M. New observations upon members of the genus Chrysotila Anand, with remarks upon their relationships within the Haptophyceae. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 1975;55:109–121. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fresnel J., Billard C. Pleurochrysis placolithoides sp. nov. (Prymnesiophyceae), a new marine coccolithophorid with remarks on the status of Cricolith-bearing species. Eur. J. Phycol. 1991;26(1):67–80. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Manton I., Peterfi L.S. Observations on the fine structure of coccoliths, scales and the protoplast of a freshwater coccolithophorid, Hymenomonas roseola Stein, with supplementary observations on the protoplast of Cricosphaera carterae. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. B. 1969;172:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Henry M., Karez C.S., Roméo M., Gnassia-Barelli M., Fresnel J., Puiseux-Dao S. Ultrastructural study and calcium and cadmium localization in the marine coccolithophorid Cricosphaera elongata. Mar. Biol. 1991;111:167–173. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Manton I., Leedale G.F. Observations on the microanatomy of Coccolithus pelagicus and Cricosphaera carterae, with special reference to the origin and nature of coccoliths and scales. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 1969;49:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Inouye I., Pienaar R.N. New observations on the coccolithophorid Umbilicosphaera sibogae var. foliosa (Prymnesiophyceae) with reference to cell covering, cell structure and flagellar apparatus. Br. Phycol. J. 1984;19(4):357–369. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Klaveness D. The microanatomy of Calyptrosphaera sphaeroidea, with some supplementary observations on the motile stage of Coccolithus pelagicus. Norweg. J. Bot. 1973;20:151–162. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fresnel J. Nouvelles observations sur une coccolithacée rare: Cruciplacolithus neohelis (McIntyre et Bé) Reinhardt (Prymnesiophyceae) PROTISTOLOGICA. 1986;22:193–204. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Parsons T.R., Stephens K., Strickland J.D.H. On the chemical composition of eleven species of marine phytoplankters. J. Fish. Res. Board Can. 1961;18:1001–1016. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tcherkez G.G.B., Farquhar G.D., Andrews T.J. Despite slow catalysis and confused substrate specificity, all ribulose bisphosphate carboxylases may be nearly perfectly optimized. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:7246–7251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600605103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Boller A.J., Thomas P.J., Cavanaugh C.M., Scott K.M. Isotopic discrimination and kinetic parameters of RuBisCO from the marine bloom-forming diatom, Skeletonema costatum. Geobiology. 2015;13:33–43. doi: 10.1111/gbi.12112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kesava Rao Ch, Indusekhar V.K. Carbon, nitrogen and phosphorous ratios in seawater and seaweeds of Saurashtra, north west coast of India. Indian J. Mar. Sci. 1987;16:117–121. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Badger M.R., Hanson M., Price G.D. Evolution and diversity of CO2-concentrating mechanisms in cyanobacteria. Funct. Plant Biol. 2002;29:161–173. doi: 10.1071/PP01213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Price G.D., Badger M.R., Woodger F.J., Long B.M. Advances in understanding the cyanobacterial CO2-concentrating-mechanism (CCM): functional components, Ci transporters, diversity, genetic regulation and prospects for engineering into plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2008;59:1441–1461. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Woodger F.J., Badger M.R., Price G.D. Sensing of inorganic carbon limitation in synechococcus PCC7942 is correlated with the size of the internal inorganic carbon pool and involves oxygen. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:1959–1969. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.069146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Saltzman M.R., Thomas E. In: Carbon Isotope Stratigraphy, the Geologic Time Scale 2012. Gradstein F., Ogg J., Schmitz M.D., Ogg G., editors. 2012. pp. 207–232. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bachan A., Lau K.V., Saltzman M.R., Thomas E., Kump L.R., Payne J.L. A model for the decrease in amplitude of carbon isotope excurions across the Phanerozoic. Am. J. Sci. 2017;317:641–676. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Popp B.N., Laws E.A., Bidigare R.R., Dore J.E., Hanson K.L., Wakeham S.G. Effect of phytoplankton cell geometry on carbon isotopic fractionation. Geochem. Cosmochim. Acta. 1998;62:69–77. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu A., Mazumder D., Dover M.C., Sheng Lal T., Crawford J., Sammut J. Stable isotope analysis of the contribution of microalga diets to the growth and survival of Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg, 1979) larvae. J. Shellfish Res. 2016;35:63–69. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rosenfelder N., Vetter W. Stable carbon isotope composition (δ13C values) of the halogenated monoterpene MHC-1 as found in fish and seaweed from different marine regions. J. Environ. Monit. 2012;14:845–851. doi: 10.1039/c2em10838k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Newton M.S., Arcus V.L., Patrick V.L. Rapid bursts and slow declines: on the possible evolutionary trajectories of enzymes. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2015;12 doi: 10.1098/rsif.2015.0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sage R.F. The evolution of C4 photosynthesis. New Phytol. 2004 doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tawfik D. Accuracy-rate tradeoffs: how do enzymes meet demands of selectivity and catalytic efficiency? Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2014;21:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bar-Even A., Noor E., Savir Y., Liebermeister W., Davidi D., Tawfik D.S., Milo R. The moderately efficient enzyme: evolutionary and physicochemical trends shaping enzyme parameters. Biochemistry. 2011;50:4402–4410. doi: 10.1021/bi2002289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bathellier C., Tcherkez G., Lorimer G.H., Farquhar G.D. RuBisCO is not really so bad. Plant Cell Environ. 2018;41:705–706. doi: 10.1111/pce.13149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Crow J.F., Kimura M. Harper & Row; New York: 1970. An Introduction to Population Genetics Theory. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Soria‐Hernanz D.F., Fiz‐Palacios O., Braverman J.M., Hamilton M.B. Reconsidering the generation time hypothesis based on nuclear ribosomal ITS sequence comparisons in annual and perennial angiosperms. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008;8:344. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Weller C., Wu M. A generation-time effect on the rate of molecular evolution in bacteria. Evolution. 2015;69:643–652. doi: 10.1111/evo.12597. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.La Barre S., Potin P., LeBlanc G., Delage L. The halogenated metabolism of Brown algae (phaeophyta), its Biological importance and its environmental significance. Mar. Drugs. 2010;8:988–1010. doi: 10.3390/md8040988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rae B.D., Long B.M., Badger M.R., Price G.D. Functions, compositions, and evolution of the two types of carboxysomes: polyhedral microcompartments that facilitate CO2 fixation in cyanobacteria and some proteobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2013;77:357–379. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00061-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dey S., North J.A., Sriram J., Evans B.S., Tabita F.R. In vivo studies in Rhodospirillum rubrum indicate that ribulose-1,5,bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) catalyzes two obligatorily required and physiologically significant reactions for distinct carbon and sulfur metabolic pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2015 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.691295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nisbet E.G., Grassineau N.V., Howe C.J., Abell P.I., Regelous M., Nisbet R.E.R. The age of RuBisCO: the evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis. Geobiology. 2007;5:311–335. [Google Scholar]

- 97.France-Lanord C., Derry L.A. Organic carbon burial forcing of the carbon cycle from Himalayan erosion. Nature. 1997;390:65. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bown P.R., Lees J.A., Young J.R. Calcareous nannoplankton evolution and diversity through time. In: Thierstein H., Young J.R., editors. Coccolithophores: from Molecular Processes to Global Impacts. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; Berlin: 2004. pp. 481–508. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cai Acidification of subsurface coastal waters enhanced by eutrophication. Nat. Geosci. 2011;4:766–770. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zeebe R.E., Westbroeck P. A simple model for the CaCO3 saturation state of the ocean: the “Strangelove,” the “Neritan,” and the “Cretan” Ocean. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2003;4:1104. [Google Scholar]