Abstract

Background

Marking the axilla with radioactive iodine seed and sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy have been proposed for axillary staging after neoadjuvant systemic therapy in clinically node‐positive breast cancer. This study evaluated the identification rate and detection of residual disease with combined excision of pretreatment‐positive marked lymph nodes (MLNs) together with SLNs.

Methods

This was a multicentre retrospective analysis of patients with clinically node‐positive breast cancer undergoing neoadjuvant systemic therapy and the combination procedure (with or without axillary lymph node dissection). The identification rate and detection of axillary residual disease were calculated for the combination procedure, and for MLNs and SLNs separately.

Results

At least one MLN and/or SLN(s) were identified by the combination procedure in 138 of 139 patients (identification rate 99·3 per cent). The identification rate was 92·8 per cent for MLNs alone and 87·8 per cent for SLNs alone. In 88 of 139 patients (63·3 per cent) residual axillary disease was detected by the combination procedure. Residual disease was shown only in the MLN in 20 of 88 patients (23 per cent) and only in the SLN in ten of 88 (11 per cent), whereas both the MLN and SLN contained residual disease in the remainder (58 of 88, 66 per cent).

Conclusion

Excision of the pretreatment‐positive MLN together with SLNs after neoadjuvant systemic therapy in patients with clinically node‐positive disease resulted in a higher identification rate and improved detection of residual axillary disease.

Replacing axillary lymph node dissection with less invasive axillary staging procedures in patients with clinically node‐positive breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant systemic therapy is debated. Implementation of several different less invasive procedures is ongoing at some centres. In this cohort, the identification rate and detection of residual disease of combined excision of the pretreatment‐positive marked lymph node with the sentinel lymph nodes were evaluated, and compared with excising only the marked lymph node or the sentinel lymph nodes alone.

Combination superior

Antecedentes

En el cáncer de mama con ganglios positivos clínicamente tras el tratamiento neoadyuvante sistémico, se ha propuesto la utilización de iodo radioactivo (Marking Axilla with Radioactive Iodine, MARI) y de la biopsia de ganglio linfático centinela para la estadificación axilar. En este estudio se evaluó la tasa de identificación y detección de enfermedad residual cuando se combinó la exéresis de los ganglios linfáticos marcados antes del tratamiento (marked lymph nodes, MLN) junto con los ganglios centinela (sentinel lymph nodes, SLN).

Métodos

Se realizó un análisis retrospectivo multicéntrico de pacientes con cáncer de mama con ganglios positivos clínicamente que se sometieron a tratamiento neoadyuvante sistémico y en las que se combinaron ambas técnicas (con o sin disección axilar). Se calcularon las tasas de identificación y detección de enfermedad residual axilar para MLN y SLN por separado y en conjunto.

Resultados

En 138/139 pacientes se identificaron ≥ 1 MLN y/o SLN combinando ambas técnicas (tasa de identificación del 99,3%). La tasa de identificación fue de 92,8% para MLN y del 87,8% para SLN. Combinando ambas técnicas se detectó enfermedad axilar residual en 88/139 (63,3%) pacientes. Se detectó enfermedad residual en 20/88 (22,7%) pacientes utilizando únicamente MLN, en 10/88 (11,4%) pacientes utilizando únicamente SLN y en 58/88 (65,9%) combinando ambas técnicas.

Conclusión

La exéresis conjunta de los ganglios marcados con iodo radioactivo antes del tratamiento neoadyuvante sistémico y de los ganglios centinela después del tratamiento en pacientes con cN+ logró una tasa de identificación más alta y una mejor detección de la enfermedad axilar residual.

Introduction

Over the past few decades, there has been a trend towards de‐escalation of surgical management of the axilla. In patients with clinically node‐positive (cN+) disease, axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) is still performed frequently, providing both regional control and information for adjuvant therapy recommendations. Neoadjuvant systemic therapy (NST) is often given to patients with cN+ disease, leading to a pathological complete response (pCR) in the axilla in approximately one‐third of patients1. Patients with an axillary pCR do not benefit from ALND, yet do suffer from both short‐ and long‐term side‐effects of the operation. There is a need for less invasive axillary staging methods for these patients.

Various less invasive procedures have been proposed for axillary staging after NST in patients with cN+ tumours before treatment. However, neither the sentinel lymph node (SLN) nor the marking of the axilla with a radioactive iodine seed (MARI) procedure have low enough false‐negative rates (FNRs) for these techniques to comfortably replace ALND1, 2, 3, 4. Based on the negative predictive values (NPVs) of these procedures, residual axillary disease may be missed in at least one in six patients with cN+ disease in whom an axillary pCR is suggested5, 6, 7. To improve accuracy, Caudle and colleagues8 introduced targeted axillary dissection, which is a combination of SLN biopsy (SLNB) and a MARI‐like procedure; this was shown to have a FNR of 2 per cent and a NPV of 97 per cent in a cohort of 85 patients. Based on this, residual axillary disease would be missed in only one of 33 patients in whom an axillary pCR is suggested. The ongoing Dutch RISAS trial (NCT02800317)9 will assess whether these promising results of a combination procedure can be validated in a prospective multicentre study.

In the absence of high‐level evidence, various protocols involving less invasive axillary staging are being implemented in clinical practice. Those in favour of SLNB alone believe that pretreatment marking of the positive lymph node is an unnecessary extra procedure, and instead support the removal of at least three sentinel nodes to improve accuracy. Advocates of the MARI procedure believe that SLNB is not of additional benefit if removal of the marked lymph node (MLN) is guaranteed, whereas others stress the need to combine these procedures to secure accurate staging. At the same time, omission of ALND is controversial as long‐term follow‐up of patients with cN+ disease in whom ALND is omitted is not yet available.

This large multicentre retrospective study analysed a cohort of patients with cN+ breast cancer who underwent a combination procedure after NST. The combination procedure comprised excision of both a pretreatment‐positive MLN and SLN(s) instead of performing standard ALND for axillary staging after NST. The identification rate and detection of residual disease of the combination procedure, and its advantages over either the MARI procedure or SLNB alone, are reported.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included patients with pathologically proven node‐positive breast cancer who underwent a combination procedure with excision of the MLN and SLN(s) after NST. Patients with distant metastasis and those who underwent SLNB before NST were not eligible. Patients were treated between September 2014 and November 2017 in four hospitals in the Netherlands: University Medical Centre Utrecht in Utrecht, Amphia Hospital in Breda, Haaglanden Medical Centre in The Hague and Alrijne Hospital in Leiderdorp. Multidisciplinary tumour boards at these centres reviewed local protocols for axillary staging, which led to replacing or preceding ALND with excision of the MLN and SLN(s) after NST in patients with cN+ disease. Type of adjuvant axillary surgery and/or radiation therapy was also decided by the multidisciplinary tumour boards. Medical records were obtained to collect data on age, breast cancer subtype, receptor status, TNM classification (AJCC 7th edition)10 before and after NST, NST regimens, imaging findings, radiological and surgical procedures, and adjuvant treatment.

This study protocol was reviewed by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of University Medical Centre Utrecht (number 18/111); the requirement for written informed consent was waived.

Neoadjuvant systemic therapy

Systemic therapy regimens were determined according to the Dutch breast cancer guidelines (2012)11 and local multidisciplinary tumour board preferences. In human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)‐positive disease, NST was combined with HER2‐targeted therapy.

Pretreatment marking of positive lymph node

Suspicious lymph nodes identified on imaging were examined pathologically by sampling the (most) suspicious lymph node using fine‐needle aspiration or core needle biopsy. Subsequently, the same lymph node, if proven N+, was marked by a radiologist under ultrasound guidance before the start of NST by means of either an iodine seed or a radio‐opaque clip, depending on local practice. If a clip was used, a wire or iodine seed was placed within the clipped lymph node after completion of NST, to facilitate removal of the clipped node during surgery. If there were multiple suspicious lymph nodes, only one node was biopsied, and marked if positive.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy

SLNB was performed by a single‐tracer method (99mTc) in Haaglanden Medical Centre, and by a dual‐tracer method (Tc and blue dye) in the other three centres. In the event of negative lymphoscintigraphy, Tc was reinjected before surgery depending on local protocols. In some patients, sampling with blue dye alone was performed. Suspicious and/or enlarged non‐SLN(s) were removed at the discretion of the surgeon.

Surgery

The combination procedure was performed simultaneously with removal of the breast by a dedicated breast surgeon. The MLN containing the iodine seed was excised under guidance of a hand‐held γ probe set to detect 125I. If the MLN contained a wire, the wire was used to guide excision of the MLN. The γ probe was then set to detect Tc and used to identify SLN(s). Surgeons were trained to note whether the MLN also showed Tc radioactivity or blue dye uptake, that is whether the MLN was the sentinel node. In all patients with an iodine seed, excision of this seed was confirmed by means of a specimen radiograph and/or the absence of 125I radioactive counts in the axilla. Specimen radiography was not undertaken routinely in patients who had wire localization.

Pathology

All lymph nodes were sectioned and stained with haematoxylin and eosin, and the pathologist could opt to use immunohistochemical analysis of the MLN and/or SLN(s). The following items were reported: number of lymph nodes, presence of an iodine seed or clip, number of positive lymph nodes and extent of residual disease. The number of examined lymph nodes reported by the pathologist was documented for the MLN and SLN separately. Their sum was the number of examined lymph nodes for the combination procedure, unless the MLN was the sentinel node. The pathological outcome of the combination procedure was based on the combined outcome of the MLN and SLNB (Table S1 , supporting information).

Adjuvant treatment

Adjuvant treatment was based on national guidelines and local multidisciplinary tumour board preferences. As residual disease may have been missed by the combination procedure in a limited number of patients, adjuvant axillary radiotherapy was frequently recommended, and also in the event of an axillary pCR. The need for completion ALND was determined on an individual basis.

Statistical analysis

The aim was to report on experiences with the combination procedure and not the accuracy of the combination procedure, as completion ALND was not undertaken in all patients. The focus was therefore on identification rate and detection of axillary residual disease for the MLN, SLNB and the combination procedure. In terms of identification rate, the combination procedure was considered successful if at least one lymph node (MLN and/or SLN) was identified. Regarding the detection of axillary residual disease, it was determined whether the MLN and the SLN were one and the same node based on data from the surgery and/or pathology report.

Either the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test was used to compare unpaired data. The McNemar exact test was used for analysis of paired assessments of the proportion of patients with cN+ disease in whom residual axillary disease was detected by the MLN, SLN(s) or by the combination of MLN with SLN(s). Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® for Windows® version 24 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

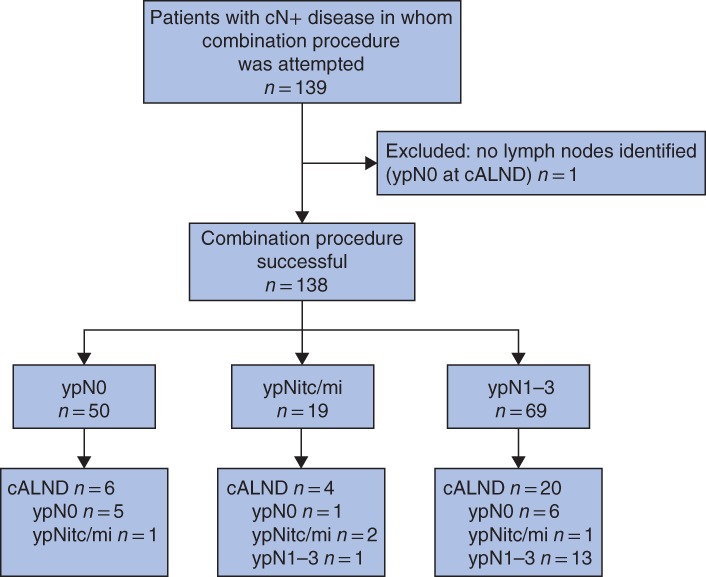

A total of 139 patients from four institutions were included in this study (Fig. 1). Patient, tumour and treatment characteristics are shown in Tables 1 and 2. An overall axillary pCR was identified in 50 of 139 patients (36·0 per cent) (74 per cent for patients with HER2‐positive, 44 per cent for those with triple‐negative, and 7·4 per cent for patients with hormone receptor‐positive, HER2‐negative tumours respectively), based on final pathological assessment of MLN, SLNs and, if applicable, completion ALND. A breast pCR was identified in 48 of 139 patients (34·5 per cent), and a pCR in both the breast and axilla in 40 of 139 (28·8 per cent).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for the study cALND, completion axillary lymph node dissection; itc/mi, isolated tumour cells/micrometastases.

Table 1.

Patient and tumour characteristics among patients with clinically node‐positive disease

| No. of patients* (n = 139) | |

|---|---|

| Treating centre | |

| University Medical Centre Utrecht | 23 (16·5) |

| Amphia Hospital | 22 (15·8) |

| Medical Centre Haaglanden | 59 (42·4) |

| Alrijne Hospital | 35 (25·2) |

| Age (years) † | 56 (26–82) |

| Clinical tumour category ‡ | |

| cT1 | 19 (14) |

| cT2 | 78 (57·4) |

| cT3 | 27 (19·9) |

| cT4 | 12 (8·8) |

| Clinical node category | |

| cN1 | 102 (73·4) |

| cN2 | 26 (18·7) |

| cN3 | 11 (7·9) |

| Histology | |

| Ductal | 117 (84·2) |

| Lobular | 10 (7·2) |

| Ductulolobular | 7 (5·0) |

| Other§ | 5 (3·6) |

| Molecular subtype | |

| HR+/HER2+ | 24 (17·3) |

| HR–/HER2+ | 22 (15·8) |

| HR+/HER2– | 68 (48·9) |

| Triple‐negative | 25 (18·0) |

| Method of confirmation of nodal positivity | |

| FNAC | 126 (90·6) |

| CNB | 13 (9·4) |

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (range).

Data available for 136 patients; one patient had relapse in mastectomy scar (patient A), one had ductal carcinoma in situ after neoadjuvant systemic therapy (NST) but no histopathological diagnosis before NST (patient B), and one had axillary relapse without signs of local relapse (patient C).

Tubulolobular carcinoma in one patient, tubular carcinoma in one patient, data missing for three patients (including patients B and C). HR, hormone receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; FNAC, fine‐needle aspiration cytology; CNB, core needle biopsy.

Table 2.

Treatment characteristics

| No. of patients (n = 139) | |

|---|---|

| Neoadjuvant regimen | |

| Chemotherapy only | 82 (59·0) |

| Chemotherapy + HER2‐directed therapy | 44 (31·7) |

| Endocrine therapy only | 13 (9·4) |

| Type of pretreatment lymph node marker | |

| Iodine seed | 68 (48·9) |

| Clip | 71 (51·1) |

| Breast surgery * | |

| Breast‐conserving surgery | 87 (63·5) |

| Mastectomy | 50 (36·5) |

| Axillary surgery | |

| Combination procedure only | 108 (77·7) |

| Combination procedure + completion ALND | 31 (22·3) |

Values in parentheses are percentages.

Excluding patients A and C in Table 1. HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; ALND, axillary lymph node dissection.

Preoperative details of nodal assessment

Data on the number of suspicious lymph nodes before NST were available for 130 of 139 patients (93·5 per cent). The median number of suspicious lymph nodes identified on ultrasound examination was 1 (range 0–5). The median number identified by MRI and/or PET–CT was 2 (range 0–9), with data available for 126 of 139 patients (90·6 per cent).

The MLN was marked primarily with an iodine seed in 68 of 139 patients (48·9 per cent) and with a clip in 71 (51·1 per cent). When a clip was used, a wire (58 of 71, 82 per cent) or iodine seed (12 of 71, 17 per cent) was placed within the lymph node after completion of NST. In one patient (1 per cent), placement of a wire was not attempted owing to the location of the lymph node and the risk of pneumothorax.

Lymphoscintigraphy was undertaken in 131 of 139 patients (94·2 per cent) as part of the SLNB procedure, and one or more hotspots were identified in 104 of 131 (79·4 per cent). SLNB was performed using a dual‐tracer technique in 76 of 139 patients (54·7 per cent) and a single‐tracer technique in 63 (45·3 per cent); 55 of the latter patients (87 per cent) patients had lymphoscintigraphy with Tc only and eight (13 per cent) with blue dye only.

Identification rates

The MLN procedure had an overall identification rate of 92·8 per cent (129 of 139). The identification rate was 93 per cent both for primary marking with an iodine seed and with a clip (P = 0·994). In patients with a clip, the identification rate was 95 per cent (55 of 58) for patients with a clip–wire combination and 92 per cent (11 of 12) for those with a clip–seed combination (P = 0·668). The iodine seed was retrieved in all patients, but a lymph node was not identified in six, meaning that the iodine seed was not located within a lymph node but in the adjacent adipose tissue. SLN(s) were identified in nine of ten patients in whom the MLN was not identified.

The SLNB procedure had an overall identification rate of 87·8 per cent (122 of 139). The identification rate was 86 per cent for the dual‐tracer and 90·4 per cent for the single‐tracer technique (P = 0·375). Three or more SLNs were removed from 46 of 122 patients (37·7 per cent). A MLN was identified in 16 of 17 patients in whom no SLN(s) were identified.

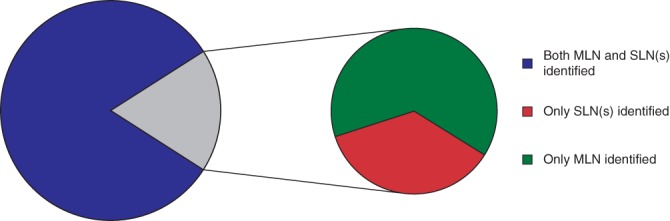

The combination procedure had an overall identification rate of 99·3 per cent (138 of 139). At least one MLN and/or SLN was identified in 138 patients. No nodes were retrieved from one patient because no SLN was identified during surgery and the iodine seed was not located within or adjacent to a lymph node. Completion ALND in this patient showed an axillary pCR. The median number of lymph nodes resected with the combination procedure was 2 (mean 2·6; range 1–9, i.q.r. 1–3). Both the MLN and SLN(s) were identified in 113 of 139 patients (81·3 per cent); either the MLN alone (16 of 139, 11·5 per cent) or only the SLN(s) (9 of 139, 6·5 per cent) were identified in the remaining 25 patients (Fig. 2). Whether the MLN and the sentinel node were the same was reported for 96 of 113 patients (85·0 per cent), and this was the case in 62 of 96 (65 per cent).

Figure 2.

Success rate in identifying both the marked lymph node and sentinel lymph nodes in a patient The figure represents 138 of 139 patients, as no marked lymph node (MLN) or sentinel lymph node (SLN) was identified in one patient. Patients in whom the MLN and SLN were one and the same were included in the group with both MLN and SLN(s) identified. In 25 of 138 patients, it was not possible to identify both the MLN and SLNs, but either the MLN or SLN(s) was identified.

Detection of residual axillary disease with the combination procedure

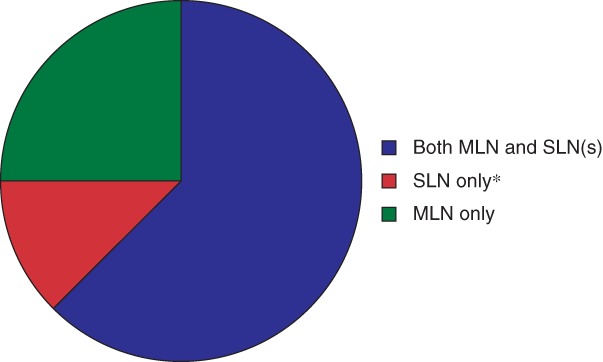

Residual axillary disease was detected in 88 of 139 patients (63·3 per cent) with the combination procedure. The median number of lymph nodes resected with the combination procedure was 2 (range 1–9) among patients with and 2 (1–7) in those without residual disease. Both the MLN and SLN(s) contained residual disease in 58 of 88 patients (66 per cent). Residual disease was detected only in the MLN in 20 of 88 (23 per cent); no SLN(s) were identified in 11 of these patients, and in nine patients the SLN did not contain residual disease whereas the MLN did. Residual disease was detected only in the SLN(s) in ten of 88 patients (11 per cent); no MLN was identified in one patient, and in nine patients the MLN did not contain residual disease but the SLN(s) did (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Types of node in which disease was found among patients with residual axillary disease identified by the combination procedure The population comprises all 88 patients in whom residual axillary disease was detected by the combination procedure. Residual disease was found only in the marked lymph node (MLN) and not in the sentinel lymph node (SLN) (either because no SLN was identified or because the SLN was free from disease), only in the SLN(s) and not in the MLN (either because no MLN was identified or because the MLN was free from disease) or in the MLN as well as the SLN(s). *Including palpable non‐SLN(s) if applicable.

The proportion of all patients in whom residual axillary disease was identified by the combination procedure (MLN and SLN(s)) was 63·3 per cent and this was significantly higher than the proportion identified using either MLN (56·1 per cent; P = 0·002) or SLN (48·9 per cent; P < 0·001) procedures alone. The proportion of patients in whom residual axillary disease was identified did not differ significantly between the MLN and the SLN procedures (56·1 versus 48·9 per cent; P = 0·100).

Palpable or suspicious lymph nodes were removed in addition to the MLN and/or SLN(s) in 29 of 139 patients (20·9 per cent) at the discretion of the surgeon. Additional nodes were removed in 21 of 122 patients (17·2 per cent) with SLNs identified, and in eight of 17 (47 per cent) with no SLNs identified. The additionally removed nodes showed macrometastasis, whereas the MLN and/or SLN(s) were negative, in three of 29 patients. In the remaining 26 patients, the additional nodes did not change the outcome based on the MLN and/or SLN(s); the disease was classified as ypN+ in 15 patients and as ypN0 in 11.

Adjuvant axillary radiotherapy

Adjuvant radiotherapy treatment plans were available for 138 of 139 patients (99·3 per cent). Adjuvant radiotherapy of the axilla was planned in 114 of 138 patients (82·6 per cent), including the periclavicular nodes in 74·6 per cent and including internal mammary nodes in 2·6 per cent.

Discussion

This retrospective analysis of a large multicentre cohort of patients who presented with biopsy‐confirmed cN+ disease evaluated the identification rate and detection of residual disease of the MLN in combination with SLNB after NST. This less invasive combination procedure had an excellent identification rate of 99·3 per cent, and enabled improved detection of residual axillary disease compared with either the MLN alone or the SLNB procedure alone.

The optimal staging and management of the axilla in patients with cN+ disease who receive NST is controversial. The need for consensus on the most appropriate method for axillary staging in this situation is reflected by the varying practices worldwide. Although SLNB has proven accurate in patients with clinically node‐negative disease, both before and after NST12, it is associated with less favourable accuracy in those with cN+ tumours treated with NST. The St Gallen International Expert Consensus Conference13 on axillary surgery after NST considered SLNB to be adequate for axillary staging before NST in patients with cN+ disease. The recommendation for patients with a clinically positive axilla after NST, and with a limited number of SLN(s) resected (fewer than 3) or with macrometastatic disease identified in the SLNs, remains ALND. It has been reported that the accuracy of SLNB in patients with cN+ tumours treated with NST depends on the number of excised SLN(s) and whether the dual‐tracer technique is used. Although the dual‐tracer technique was used in only 54·7 per cent of patients in the present cohort, the identification rate for SLNB was high at 87·8 per cent. However, only 37·7 per cent had three or more SLNs removed. To act in accordance with the St Gallen recommendations would have required completion ALND in a significant number of patients, including those with an axillary pCR. As most patients will not have at least three SLNs identified at surgery, ensuring removal of the MLN in addition to the SLN(s) may be a better strategy. Targeted axillary dissection, developed at MD Anderson Cancer Center, appears promising, with a FNR of 2 per cent and NPV of 97 per cent8. Recently, the prospective ILINA trial14 was reported, which included ultrasound‐guided excision of the MLN in combination with SLNB. Of 46 patients with cN+ disease treated with NST, 35 completed the protocol followed by ALND, resulting in a FNR of 4·1 per cent and NPV of 91·7 per cent. Although both studies reported promising results, evidence is hampered by single‐centre study designs and small sample sizes. The Dutch multicentre RISAS trial6 is currently accruing with the aim of enrolling a prospective cohort of 225 patients with cN+ disease.

A survey15 among members of the American Society of Breast Surgeons revealed that only 15 per cent of 638 respondents still perform ALND in all patients with cN+ tumours treated with NST, and that 54 per cent offer SLNB with possible omission of ALND in over half of their patients. The survey also showed that different methods are used for localization of the clipped and marked lymph node (73 per cent wire, 13 per cent iodine seed, 14 per cent other) after completion of NST. In the present cohort, identification rates were similar for patients in whom the positive lymph node was marked primarily with an iodine seed versus a clip. For patients in whom a clip was placed, identification rates were also similar between placing a wire or an iodine seed after NST. Other marking techniques reported previously, such as charcoal tattooing16, 17, were not used here.

Besides using a combination of the MLN and SLN(s), recent reports18, 19 have suggested combining the outcome of MARI with the number of fluorodeoxyglucose‐avid lymph nodes on PET–CT carried out before NST to determine the need for further axillary treatment. Among 159 patients with cN+ disease included in the analysis, the proposed treatment algorithm resulted in no further axillary treatment in 24·5 per cent, axillary radiotherapy in 57·3 per cent, and ALND in combination with axillary radiotherapy in 18·2 per cent. As in the present cohort, longer follow‐up is needed to prove the long‐term oncological safety of omitting ALND with the risk of leaving residual disease behind. Sufficient data have not yet been reported on the long‐term outcome of patients with cN+ disease in whom ALND was replaced by less invasive staging procedures.

In previous cohorts that received combination procedures17, 20, 21, sometimes ten or more lymph nodes were retrieved, even though these procedures aim to offer a less invasive alternative to ALND. In the present cohort, only one to three lymph nodes were excised in half of the patients. Furthermore, the median number of excised lymph nodes was the same for patients with and without residual axillary disease. This suggests that the improved detection of residual disease achieved with the combination procedure did not result from removing more lymph nodes.

As ALND was not performed routinely in the present cohort, it was not possible to calculate the FNR and NPV for the combination procedure. Although not all patients underwent ALND, the combination procedure improved the detection rate of residual axillary disease compared with that had the MLN procedure or SLNB been performed as a stand‐alone staging procedure. This might because one method covered the failure of the other. An axillary pCR may be predicted based on the MLN, whereas residual axillary disease is predicted based on the SLN(s) and vice versa. A possible explanation for false‐negative SLN(s) could be residual disease obstructing normal lymphatic drainage or NST altering normal lymphatic drainage. The phenomenon of false‐negative SLN(s) has been reported previously by Caudle and colleagues15, who noted that the clipped node was not retrieved as a SLN in 23 per cent of patients in their cohort. A possible explanation for a false‐negative MLN could be unsuccessful marking of the most suspicious lymph node, with the marker located in adipose tissue or in non‐metastatic lymph nodes, or the existence of differential responses to chemotherapy in the axilla.

The present study is limited by its retrospective design. The combination procedure differed between institutions, although these differences reflect real‐world clinical practice. Optimal axillary management after NST in patients with cN+ disease before treatment is currently being investigated in the Alliance A01120222 and National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project 51/Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 130423 trials. These trials will determine optimal management of the axilla based on response to chemotherapy. Until then, the combination procedure for axillary staging in patients with cN+ tumours treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy can be recommended when omission of ALND is considered.

Supporting information

Table S1. Pathologic outcome of the combination procedure

Acknowledgements

No preregistration exists for the study reported in this article. J.M.S. received a salary from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF Kankerbestrijding).

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Simons JM, van Nijnatten TJA, van der Pol CC, Luiten EJT, Koppert LB, Smidt ML. Diagnostic accuracy of different surgical procedures for axillary staging after neoadjuvant systemic therapy in node‐positive breast cancer: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ann Surg 2019; 269: 432–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boileau JF, Poirier B, Basik M, Holloway CM, Gaboury L, Sideris L et al Sentinel node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in biopsy‐proven node‐positive breast cancer: the SN FNAC study. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boughey JC, Suman VJ, Mittendorf EA, Ahrendt GM, Wilke LG, Taback B et al; Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology . Sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node‐positive breast cancer: the ACOSOG Z1071 (Alliance) clinical trial. JAMA 2013; 310: 1455–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kuehn T, Bauerfeind I, Fehm T, Fleige B, Hausschild M, Helms G et al Sentinel‐lymph‐node biopsy in patients with breast cancer before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (SENTINA): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 609–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Donker M, Straver ME, Wesseling J, Loo CE, Schot M, Drukker CA et al Marking axillary lymph nodes with radioactive iodine seeds for axillary staging after neoadjuvant systemic treatment in breast cancer patients: the MARI procedure. Ann Surg 2015; 261: 378–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van Nijnatten TJ, Schipper RJ, Lobbes MB, Nelemans PJ, Beets‐Tan RG, Smidt ML. The diagnostic performance of sentinel lymph node biopsy in pathologically confirmed node positive breast cancer patients after neoadjuvant systemic therapy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol 2015; 41: 1278–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vugts G, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, Maaskant‐Braat AJ, Schipper RJ, Smidt ML. Axillary response monitoring after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: can we avoid the morbidity of axillary treatment? Ann Surg 2016; 263: e28–e29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caudle AS, Yang WT, Krishnamurthy S, Mittendorf EA, Black DM, Gilcrease MZ et al Improved axillary evaluation following neoadjuvant therapy for patients with node‐positive breast cancer using selective evaluation of clipped nodes: implementation of targeted axillary dissection. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 1072–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Nijnatten TJA, Simons JM, Smidt ML, van der Pol CC, van Diest PJ, Jager A et al A novel less‐invasive approach for axillary staging after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with axillary node‐positive breast cancer by combining Radioactive Iodine Seed localization in the Axilla with the Sentinel node procedure (RISAS): a Dutch prospective multicentre validation study. Clin Breast Cancer 2017; 17: 399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene F, Trotti A . AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (7th edn). Springer: New York, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11. CBO Kwaliteitsinstituut voor de Gezondheidszorg; Vereniging van Integrale Kankercentra Richtlijn ‘Behandeling van het Mammacarcinoom’. [Guideline ‘Treatment of Breast Cancer’.] Nationaal Borstkanker Overleg Nederland: Utrecht, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hunt KK, Yi M, Mittendorf EA, Guerrero C, Babiera GV, Bedrosian I et al Sentinel lymph node surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy is accurate and reduces the need for axillary dissection in breast cancer patients. Ann Surg 2009; 250: 558–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Curigliano G, Burstein HJ, P Winer E, Gnant M, Dubsky P, Loibl S et al De‐escalating and escalating treatments for early‐stage breast cancer: the St. Gallen International Expert Consensus Conference on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2017. Ann Oncol 2017; 28: 1700–1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Siso C, de Torres J, Esgueva‐Colmenarejo A, Espinosa‐Bravo M, Rus N, Cordoba O et al Intraoperative ultrasound‐guided excision of axillary clip in patients with node‐positive breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant therapy (ILINA Trial): a new tool to guide the excision of the clipped node after neoadjuvant treatment. Ann Surg Oncol 2018; 25: 784–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Caudle AS, Bedrosian I, Milton DR, DeSnyder SM, Kuerer HM, Hunt KK et al Use of sentinel lymph node dissection after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node‐positive breast cancer at diagnosis: practice patterns of American Society of Breast Surgeons members. Ann Surg Oncol 2017; 24: 2925–2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim WH, Kim HJ, Jung JH, Park HY, Lee J, Kim WW et al Ultrasound‐guided restaging and localization of axillary lymph nodes after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for guidance of axillary surgery in breast cancer patients: experience with activated charcoal. Ann Surg Oncol 2018; 25: 494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Park S, Koo JS, Kim GM, Sohn J, Kim SI, Cho YU et al Feasibility of charcoal tattooing of cytology‐proven metastatic axillary lymph node at diagnosis and sentinel lymph node biopsy after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Cancer Res Treat 2018; 50: 801–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van der Noordaa MEM, van Duijnhoven FH, Straver ME, Groen EJ, Stokkel M, Loo CE et al Major reduction in axillary lymph node dissections after neoadjuvant systemic therapy for node‐positive breast cancer by combining PET/CT and the MARI procedure. Ann Surg Oncol 2018; 25: 1512–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Koolen BB, Donker M, Straver ME, van der Noordaa MEM, Rutgers EJT, Valdés Olmos RA et al Combined PET–CT and axillary lymph node marking with radioactive iodine seeds (MARI procedure) for tailored axillary treatment in node‐positive breast cancer after neoadjuvant therapy. Br J Surg 2017; 104: 1188–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Diego EJ, McAuliffe PF, Soran A, McGuire KP, Johnson RR, Bonaventura M et al Axillary staging after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: a pilot study combining sentinel lymph node biopsy with radioactive seed localization of pre‐treatment positive axillary lymph nodes. Ann Surg Oncol 2016; 23: 1549–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Taback B, Jadeja P, Ha R. Enhanced axillary evaluation using reflector‐guided sentinel lymph node biopsy: a prospective feasibility study and comparison with conventional lymphatic mapping techniques. Clin Breast Cancer 2018; 18: e869–e874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. http://ClinicalTrials.gov. Comparison of Axillary Lymph Node Dissection with Axillary Radiation for Patients with Node‐Positive Breast Cancer Treated with Chemotherapy https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01901094 [accessed 30 October 2018].

- 23. http://ClinicalTrials.gov. Standard or Comprehensive Radiation Therapy in Treating Patients with Early‐Stage Breast Cancer Previously Treated with Chemotherapy and Surgery https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01872975 [accessed 30 October 2018].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Pathologic outcome of the combination procedure