Abstract

Background

Magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound ablation of the thalamic ventral intermediate nucleus is a safe and effective treatment for medically refractory essential tremor. However, indirect targeting of the ventral intermediate nucleus using stereotactic coordinates from normal neuroanatomy can be inefficient. We therefore evaluated the feasibility of supplementing this method with direct targeting of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract.

Methods

We retrospectively identified four patients undergoing magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound ablation for essential tremor in which preoperative diffusion tractography imaging of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract was fused with T2 weighted-imaging and utilized for intra-procedural targeting. The size and location of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract and 24-hour lesion, as well as the center of the stereotactic coordinates, was evaluated. Finally, the amount of overlap between the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract and the lesion was calculated.

Results

The 24-hour lesion size was homogeneous in the cohort (mean 31.3 mm2, range 30–32 mm2), while there was substantial variation in the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract area (mean 14.3 mm2, range 3–24 mm2). The center of the stereotactic coordinates and dentato-rubro-thalamic tract diverged by more than 1 mm in mediolateral and anterposterior directions in all patients, while the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract and lesion centers were in close proximity (mean mediolateral separation 1 mm, range 0.1–2.2 mm; mean anteroposterior separation 0.75 mm, range 0.4–1.2 mm). There was greater than 50% coverage of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract by the lesion in all patients (mean 82.9%, range 66.7–100%). All patients experienced durable tremor relief.

Conclusion

Direct targeting of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract using diffusion tractography imaging fused to T2 weighted-imaging may be a useful strategy for focused ultrasound treatment of essential tremor. Further investigation of the technique is warranted.

Keywords: MR-guided high frequency ultrasound ablation, essential tremor, diffusion tensor imaging

Introduction

Magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) ablation of the thalamic ventral intermediate nucleus (Vim) has emerged as a safe and effective, non-invasive treatment for medically refractory essential tremor.1–5 However, as the Vim cannot be readily identified on conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), targeting of the nucleus is often performed indirectly using standardized distances from the posterior commissure and midline in the mid-commissural axial plane. These distances, and their resulting Vim coordinates, are derived from prior study of atlases of normal human neuroanatomy.6,7 Yet, due to anatomical variations such as enlargement of the third ventricle, these coordinates may not accurately depict the true location of the nucleus in individual patients.6 If the Vim is not reliably targeted, multiple, time-consuming adjustments of the ablation location based on the patient’s clinical response during treatment may be required. Furthermore, there may be a greater chance of symptom recurrence if the final ablation zone does not adequately cover the Vim.

Prior work has suggested that the true target of tremor-alleviating procedures such as deep brain simulation (DBS) may be white matter tracts extending through the Vim, namely the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract (DRT).8–16 The tract passes through several established tremor-reducing targets, including the caudal zona incerta, the posterior subthalamic region, as well as the Vim and can be visualized using diffusion tractography imaging (DTI).7–9,15–26 As prior work using DTI to target this network during DBS and stereotactic radiosurgery had shown promise, we began incorporating tractography imaging into our planning for focused ultrasound Vim thalamotomy.7–9,15,17–25 This was accomplished by fusing the DRT as depicted by DTI to preoperative T2 weighted-imaging (T2WI), and importing the resulting images into the InSightec ablation system for direct intra-procedural targeting. However, uncertainty remains as to the feasibility of this technique for guiding treatments and for effective long-term tremor suppression.

We therefore elected to evaluate clinical and imaging outcomes in four representative patients treated by MRgFUS for essential tremor at our institution. Imaging outcomes analyzed included the size and location of the DRT and 24-hour lesion, as well as the center of the atlas-derived coordinates. The amount of overlap between DRT and the 24-hour lesion was also evaluated.

Methods

Study design, setting and participants

Twenty-four patients were enrolled in the institutional review board-approved prospective, essential tremor and continued access studies at our institution from July 2014 to August 2016. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The inclusion and exclusion criteria have previously been published.5 Briefly, a movement disorder neurologist determined patient diagnosis and eligibility for treatment, with the severity of tremor evaluated using the clinical rating scale for tremor at baseline. All patients were on a stable dose of anti-tremor medication(s) prior to ablation. Eligible patients then underwent MRgFUS thalamotomy contralateral to the dominant hand. From this prospective cohort, we retrospectively identified four representative patients in whom preoperative DTI imaging of the DRT was fused with T2WI and subsequently utilized for direct intra-procedural ablation guidance.

Pre-procedure imaging

All patients underwent a non-contrast head computed tomography (CT) and MRI of the brain prior to the procedure. For patients undergoing pretreatment CT imaging at our institution, CT images were acquired on a 128-row multi-detector CT scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions; Erlangan, Germany). Images reconstructed using C-filter in bone windows were utilized for skull density measurements, identifying and marking calcifications and for procedural planning.

Anatomical and diffusion tensor MRI was performed on a clinical 3-Tesla Tim Trio MRI system (Siemens Medical Solutions). Anatomical sequences were performed using a 12-channel head coil and consisted of a three-dimensional (3D) MPRAGE (TR = 2300 ms, TE = 2.91 ms, TI = 900 ms, flip angle = 9°, field of vision = 256 mm × 256 mm, voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm3 and 176 sagittal slices) as well as a 3D T2 TSE sequence (TR = 3000 ms, TE = 222 ms, echo train duration 444 ms, flip-angle mode T2 variable, voxel size = 1 ×1 × 1 mm3). Both T1 and T2 images were reformatted in the axial plane parallel to the anterior-posterior commissure line. Diffusion tensor imaging was performed in the same axial direction using a twice-refocused single shot two-dimensional (2D) SE EPI for reduced eddy current artifacts (TR = 6700 ms, TE = 102 ms, diffusion b values b = 0 s/mm2 and b = 1000 s/mm2, 2500 s/mm2 with diffusion directions 45, 52 axial slices, voxel size 2.7 × 2.7 × 2.7 mm3).

DTI reconstruction and tractography was carried out on a Siemens Leonardo workstation (Siemens Medical Solutions) using a Neuro3D task card (Siemens Medical Solutions). Reconstructed DTI maps were fused to T2WI through rigid transformation by maximization of the normalized mutual information cost function. DTI maps were then interpolated to a resolution of 1 × 1 × 1 cm3 for image overlay on T2WI through an optimized implementation that combined a partial volume interpolation scheme and a multiresolution strategy to cope efficiently with volumes of arbitrary resolution. The accuracy of DTI and T2WI fusion was assessed by viewing the overlay of FA color map and underlying anatomical structure provided by T2WI. Deterministic fiber tracking was carried out using the fourth order Runge-Kutta algorithm with tracking parameters chosen to optimize visualization of the DRT (FA threshold: 0.2, angle threshold: 30°, samples per voxel length: 2, step length: 1.35 mm). We began fiber tracking with a cubic volume of interest (VOI) defining the red nucleus (RN) and hand knob of the pre-central gyrus ipsilateral to the target Vim on T2WI. The resulting fibers originate in the dentate nucleus, decussate and follow the contralateral cerebral peduncle, passing through the Vim followed by the corona radiata, and extending to the primary motor strip (M1) in the pre-central gyrus. The resulting fiber tracts were saved as overlay on pre-procedure high resolution T2WI. Finally, the fused images were transferred to the Insightec workstation for intra-procedural ablation guidance.

Procedural details

Details regarding focused ultrasound Vim ablation using the ExAblate system (Insightec, Haifa, Israel) have previously been described.5 Briefly, an Integra CRW stereotactic head frame (Integra Lifesciences, Plainsboro, NJ, USA) was placed on the patient’s head after shaving and administration of local anesthetic. The patient was then placed supine on the magnetic resonance table with the head coupled to the focused ultrasound device in a degassed and cooled water bath. The Vim contralateral to the most affected upper extremity was localized on T2WI at the level of the axial mid-commissural plane. Simultaneously, preprocedure T2WI with fused DRT tract that had been earlier imported into the Exablate treatment software (Insightec) was reviewed for targeting guidance (Figure 1).

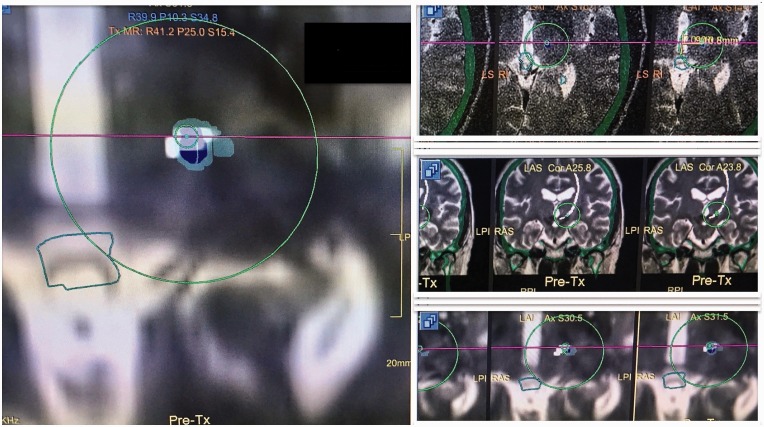

Figure 1.

A screenshot of intraoperative imaging during ablation of the left dentato-rubro-thalamic tract (DRT) (tract shown in white color). Note that the center of the transducer is placed on the anterior aspect (small, green circle) of the DRT. The light green color represents the thermal map superimposed on the DRT and the transducer target location. The location of the target can be confirmed in multiple planes (the magnified view on the left is in the axial plane). The images on the right demonstrate the target in relation to axial and coronal location of the DRT.

Serial focused ultrasound lesioning of the Vim was then performed by heating an approximately 2 mm diameter volume of tissue with short, low-energy sonications generating non-ablative temperatures (i.e. 40–45℃). During and after each sonication, patients were monitored clinically by serial physical examination for side effects and treatment efficacy. In addition, the size and location of the ablative zone was also monitored by magnetic resonance thermometry. If no side effects were encountered with low-energy sonications at a given target location, the deposited energy was then incrementally increased to achieve ablative temperatures.

In our practice, we generally begin Vim thalamotomy by sonicating at the target derived by the indirect method using standardized distances from the midline and posterior commissure in the axial mid-commissural plan. In the few cases when this initial target and the center of the DRT coincide, tractography plays no further role in the procedure. However, when the two diverge, we then repeat the process of trial sonication followed by ablation targeting the DRT, usually beginning at the anteromedial border to maximize the distance from the medial lemniscus and pyramidal tracts. Movement of the target in the craniocaudal direction out of the mid-commissural plane is generally not performed. The latter strategy is consistent with the hypothesis that the DRT is the true tremor-alleviating target, and that disruption of the 3D tract is achievable by ablating the fibers in a single cross-sectional area.

Following the treatment session, the stereotactic frame was removed and patients were typically discharged from the hospital the following day. A post-procedure MRI of the brain was acquired prior to discharge.

Evaluation of location and degree of overlap of the 24-hour lesion and DRT

To evaluate the agreement in the 24-hour lesion and DRT, we first linearly registered the post-treatment T2WI to the anterior-posterior commissure line aligned pretreatment T2WI (with DRT overlay) using Flirt command with 6 degrees of freedom in FSL (FMRIB, Oxford, UK). All measurements of 24-hour lesion and DRT area/location were performed in the same axial, mid-commissural plane that was utilized for focused ultrasound ablation. The boundary areas of both the 24-hour lesion, as well as the DRT, were then manually traced on the mid-commissural axial slice using the medical imaging processing, analysis and visualization (MIPAV) tool from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). For lesion region-of-interest (ROI), we use the zone 2 ablation lesion. Zone 2 is defined by Ghanouni et al.27 as the area of cytotoxic edema in the center of the lesion, and is delineated by the larger area of surrounding vasogenic edema by a clear hyper-intense rim. The DRT ROI was depicted by marking the edge of the DRT tract on the T2WI with DRT overlay. Both the area and center of gravity for each ROI was noted. Next, the locations of the 24-hour lesion and DRT were compared (Figure 2). A similar analysis was performed evaluating the location of the centers of the DRT and the indirect, stereotactic coordinates.

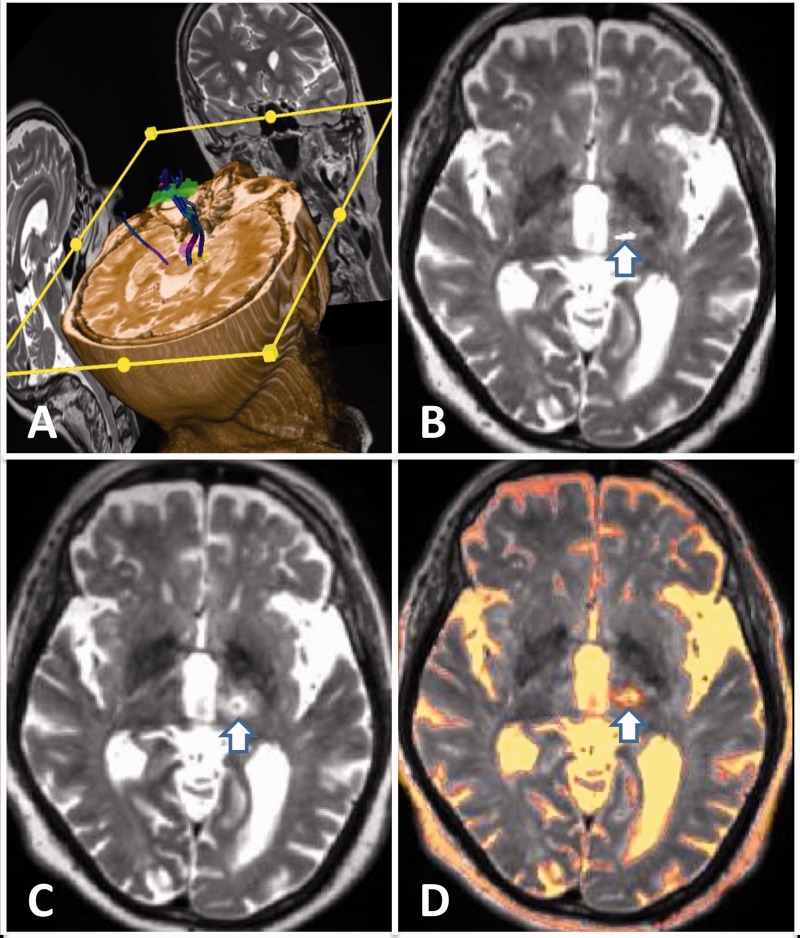

Figure 2.

(a) Multi-planar diffusion tractography imaging of the dentato-rubro-thalamic (DRT) and corticospinal tracts. (b) DRT (white arrow) superimposed on pre-procedure T2 weighted-imaging (T2WI) in the axial plane. (c) Post-ablation T2WI demonstrating the ablation zone (white arrow). (d) Superimposed pre and post-treatment T2WI with overlay of the DRT and ablation zone (white arrow).

Finally, the amount of overlap between the DRT and 24-hour lesion was calculated as a percentage in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) using the following formula:

Where ROIDRT denotes the ROI of the DRT in the axial mid-commissural plane, and ROIAbl denotes the ROI of the 24-hour zone 2 lesion.

Evaluation of clinical response

The severity of the patients’ tremor before and after the procedure was evaluated and compared using the clinical rating scale for tremor (CRST).5 The three components of the CSRT include part A (resting, postural and intentional hand tremor), part B (handwriting, drawing, pouring tasks) and part C (disability subsection). The tremor score ranges from 0 to 32 and higher scores indicate more severe tremors and disease severity. Focus was placed on change in the CRST score for the dominant upper extremity following contralateral focused ultrasound thalamotomy.

Results

The size of the 24-hour zone 2 lesion area was fairly homogeneous in the cohort (mean 31.3 mm2, range 30–32 mm2). However, there was significant variation in the area of the DRT as depicted by DTI in the axial mid-commissural plane (mean 14.3 mm2, range 3–24 mm2). When comparing the centers of the indirect, atlas-derived Vim coordinates and those of the DRT, as depicted by DTI, the two diverged in location by more than 1 mm in both the mediolateral and anterposterior planes in all four patients. In contradistinction, the locations of the DRT and 24-hour lesion demonstrated their centers to be in close proximity (mean medial-lateral separation 1 mm, range 0.1–2.2 mm; mean anterior-posterior separation 0.75 mm, range 0.4–1.2 mm). Finally, there was greater than 50% DRT coverage by the 24 hour zone 2 lesion in all four patients (mean 82.9%, range 66.7–100%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Locations and percentage overlap between DRT and 24-hour lesion.

| Patient | Distance of lesion center from midcommisural line (mm) | Distance of tract center from midcommisural line (mm) | Distance of lesion center from posterior commissure (mm) | Distance of tract center from posterior commissure (mm) | Lesion area (mm2) | Tract area (mm2) | % Lesion–tract overlap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14.1 | 14.0 | 5.8 | 7 | 31 | 3 | 100.0 |

| 2 | 15.1 | 17.3 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 32 | 15 | 66.7 |

| 3 | 13.3 | 12.4 | 6.7 | 7.1 | 30 | 15 | 73.3 |

| 4 | 14.2 | 15.0 | 4.8 | 6.0 | 32 | 24 | 91.7 |

DRT: dentato-rubro-thalamic tract.

All patients experienced significant, lasting tremor relief following their procedure. The baseline CSRT composite scores for these patients were 38, 66, 76 and 50, respectively, and reduced to 21, 36, 29 and 32, respectively, at the 3-month follow-up. One of the four patients died before the 6-month follow-up due to unrelated cardiac arrest. The therapeutic benefit was sustained at one year for the remaining three patients. The tremor score for the dominant hand improved from respective baseline, pre-treatment values of 5, 7, 7, 7 (mean score 6.5) to 0, 1, 0, 2, respectively (mean score 0.75). The mean tremor score improvement at 3 months was 88.5% (range 71–100%). There were no procedure-related complications.

Discussion

Earlier reports have demonstrated the efficacy of direct DRT targeting using DTI in patients with refractory essential tremor undergoing DBS or stereotactic radiosurgery.8,9 Similarly, our study suggests that direct targeting of the DRT during MRgFUS using fused DTI–T2WI uploaded to the ablation system may be a feasible ablation strategy. While MRgFUS has several potential advantages compared to other tremor-reducing techniques such as DBS, one of its challenges is the lack of intra-procedural electrode recordings to confirm correct target localization. Consequently, accurate imaging guidance of focused ultrasound ablation is essential. Although monitoring of the patient’s clinical response may be helpful for targeting, this approach cannot differentiate between ablation of the tremor-relieving target versus stunning (i.e. target at the periphery of the ablation lesion), which may lead to early symptom recurrence. Moreover, the adequacy of treatment response may sometimes be difficult to interpret intraprocedurally, particularly during long-duration procedures in which factors such as patient fatigue or discomfort may confound the clinical examination.

Although we still continue to utilize the indirect, atlas-derived method for Vim localization, we believe that DTI has facilitated treatment of essential tremor patients by potentially avoiding instances of inadequate or non-durable symptom relief. Anecdotally, we have found that direct DRT targeting has allowed for rapid adjustment of the ablation site in instances when there is an inadequate response at the indirect coordinates. In other cases when tremor relief is quickly achieved, DRT visualization has provided guidance on the direction in which to extend the ablation zone to ensure a long-lasting response (e.g. avoid stunning of the tremor-abating target). In this way, DTI information may potentially serve as a tool to guide creation of the ablation zone in MRgFUS.

Similar to prior investigations of DTI targeting of DBS for essential tremor, we found that the DRT is often located near, but does not precisely coincide with, the coordinates derived from the indirect, atlas-based targeting method. This is presumably due to anatomical variation in individual patients, such as an enlarged third ventricle, which may confound the indirect method.6 Furthermore, although a majority (<50%) of the DRT in the axial mid-commissural plane was covered by the 24-hour lesion in our cohort, there was substantial variation in tract coverage between the individual patients. We believe the uniformly good clinical responses noted in our cohort, despite this variation in DRT coverage, may be explained by several factors. These include the lower spatial resolution of DTI compared to conventional MRI, as well as small inherent errors in registration of the pre and postoperative MRI, which may lead to some inaccuracy in depiction of the location of the tract. Furthermore, it is also possible that the true tremor-reducing target comprises only a portion of the DRT at the mid-commissural level. Finally, in some cases the true tremor-reducing target may have been in the periphery of the 24-hour lesion, with the observed clinical response resulting from stunning of this region. However, the durable treatment responses observed in our cohort argue against this possibility.

A prior study of four patients also used DTI DRT targeting for MRgFUS ablation for essential tremor, and reported improvement in symptoms to correlate with successful interruption of DRT on postoperative DTI imaging.28 However, in that report the authors simply referenced a 3D display of the tractography imaging during the procedure for target localization, as opposed to the direct overlaying of tracts onto thin section T2WI imported into the InSightec ablation system, as performed in our study. Furthermore, as the authors were not fusing tractography to post-ablation T2 imaging, they were unable quantitatively to evaluate the percentage of DRT that was included in the final ablation lesion. Instead, they evaluated tract ablation by performing tractography of the targeted DRT one day post-treatment. In these instances, they were unable to re-demonstrate the tract, which they suggested indicated successful ablation. However, we are skeptical of this conclusion given the amount of edema that is typically seen at the treatment site acutely following ablation, which may also interfere with successful fiber tracking.

The current study suffers from several limitations, including its small size, retrospective nature, and lack of a control group. Our results will therefore need to be validated in a larger cohort of patients and ideally compared to controls in which DTI imaging is not utilized for Vim targeting. Despite these limitations, we believe that our findings support further investigation of the use of DTI localization of the DRT during focused ultrasound treatment of essential tremor.

Conclusion

Our pilot study suggests that direct intraprocedure targeting of the DRT using DTI fused to T2WI may help to facilitate MRgFUS ablation performed for the treatment of medically refractory essential tremor. However, the approach needs to be validated in a larger cohort of patients.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Zaaroor M, Sinai A, Goldsher D, et al. Magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy for tremor: a report of 30 Parkinson’s disease and essential tremor cases. J Neurosurg 2017; 128: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallay MN, Moser D, Rossi F, et al. Incisionless transcranial MR-guided focused ultrasound in essential tremor: cerebellothalamic tractotomy. J Ther Ultrasound 2016; 4: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipsman N, Schwartz ML, Huang Y, et al. MR-guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy for essential tremor: a proof-of-concept study. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weintraub D, Elias WJ. The emerging role of transcranial magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused ultrasound in functional neurosurgery. Mov Disord 2017; 32: 20–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elias WJ, Lipsman N, Ondo WG, et al. A randomized trial of focused ultrasound thalamotomy for essential tremor. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 730–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anthofer J, Steib K, Fellner C, et al. The variability of atlas-based targets in relation to surrounding major fibre tracts in thalamic deep brain stimulation. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2014; 156: 1497–1504. discussion 1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim W, Sharim J, Tenn S, et al. Diffusion tractography imaging-guided frameless linear accelerator stereotactic radiosurgical thalamotomy for tremor: case report. J Neurosurg 2017; 128: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coenen VA, Allert N, Madler B. A role of diffusion tensor imaging fiber tracking in deep brain stimulation surgery: DBS of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract (drt) for the treatment of therapy-refractory tremor. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2011; 153: 1579–1585. discussion 1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coenen VA, Varkuti B, Parpaley Y, et al. Postoperative neuroimaging analysis of DRT deep brain stimulation revision surgery for complicated essential tremor. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2017; 159: 779–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomes JG, Gorgulho AA, de Oliveira Lopez A, et al. The role of diffusion tensor imaging tractography for Gamma Knife thalamotomy planning. J Neurosurg 2016; 125(Suppl. 1): 129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bastian AJ, Thach WT. Cerebellar outflow lesions: a comparison of movement deficits resulting from lesions at the levels of the cerebellum and thalamus. Ann Neurol 1995; 38: 881–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colebatch JG, Findley LJ, Frackowiak RS, et al. Preliminary report: activation of the cerebellum in essential tremor. Lancet 1990; 336: 1028–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deuschl G, Raethjen J, Lindemann M, et al. The pathophysiology of tremor. Muscle Nerve 2001; 24: 716–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein JC, Barbe MT, Seifried C, et al. The tremor network targeted by successful VIM deep brain stimulation in humans. Neurology 2012; 78: 787–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coenen VA, Allert N, Paus S, et al. Modulation of the cerebello-thalamo-cortical network in thalamic deep brain stimulation for tremor: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Neurosurgery 2014; 75: 657–669. discussion 669–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hyam JA, Owen SL, Kringelbach ML, et al. Contrasting connectivity of the ventralis intermedius and ventralis oralis posterior nuclei of the motor thalamus demonstrated by probabilistic tractography. Neurosurgery 2012; 70: 162–169. discussion 169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barkhoudarian G, Klochkov T, Sedrak M, et al. A role of diffusion tensor imaging in movement disorder surgery. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2010; 152: 2089–2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calabrese E. Diffusion tractography in deep brain stimulation surgery: a review. Front Neuroanat 2016; 10: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King NKK, Krishna V, Basha D, et al. Microelectrode recording findings within the tractography-defined ventral intermediate nucleus. J Neurosurg 2017; 126: 1669–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pouratian N, Zheng Z, Bari AA, et al. Multi-institutional evaluation of deep brain stimulation targeting using probabilistic connectivity-based thalamic segmentation. J Neurosurg 2011; 115: 995–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sammartino F, Krishna V, King NK, et al. Tractography-based ventral intermediate nucleus targeting: novel methodology and intraoperative validation. Mov Disord 2016; 31: 1217–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sasada S, Agari T, Sasaki T, et al. Efficacy of fiber tractography in the stereotactic surgery of the thalamus for patients with essential tremor. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2017; 57: 392–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fenoy AJ, Schiess MC. Deep brain stimulation of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract: outcomes of direct targeting for tremor. Neuromodulation 2017; 20: 429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schlaier J, Anthofer J, Steib K, et al. Deep brain stimulation for essential tremor: targeting the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract? Neuromodulation 2015; 18: 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Avecillas-Chasin JM, Alonso-Frech F, Parras O, et al. Assessment of a method to determine deep brain stimulation targets using deterministic tractography in a navigation system. Neurosurg Rev 2015; 38: 739–750. discussion 751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coenen VA, Madler B, Schiffbauer H, et al. Individual fiber anatomy of the subthalamic region revealed with diffusion tensor imaging: a concept to identify the deep brain stimulation target for tremor suppression. Neurosurgery 2011; 68: 1069–1075. discussion 1075–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghanouni P, Pauly KB, Elias WJ, et al. Transcranial MRI-guided focused ultrasound: a review of the technologic and neurologic applications. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015; 205: 150–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chazen JL, Sarva H, Stieg PE, et al. Clinical improvement associated with targeted interruption of the cerebellothalamic tract following MR-guided focused ultrasound for essential tremor. J Neurosurg 2017; 129: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]