Abstract

Abnormal cell metabolism with vigorous nutrition consumption is one of the major physiological characteristics of cancers. As such, the strategy of cancer starvation therapy through blocking the blood supply, depleting glucose/oxygen and other critical nutrients of tumors has been widely studied to be an attractive way for cancer treatment. However, several undesirable properties of these agents, such as low targeting efficacy, undesired systemic side effects, elevated tumor hypoxia, induced drug resistance, and increased tumor metastasis risk, limit their future applications. The recent development of starving-nanotherapeutics combined with other therapeutic methods displayed the promising potential for overcoming the above drawbacks. This review highlights the recent advances of nanotherapeutic-based cancer starvation therapy and discusses the challenges and future prospects of these anticancer strategies.

Keywords: drug delivery, nanomedicine, cancer starvation therapy, combination treatment

1. Introduction

Characterized by abnormal cell metabolism and growth with risk of metastasis, cancer remains a global fatal threat to human health today 1, 2. In recent years, cancer starvation therapy is emerging as an effective method for suppressing tumor growth and survival through blocking blood flow or depriving their essential nutrients/oxygen supply 3-5. The transport of nutrients could be blocked by stopping the tumor blood supply with the treatments of angiogenesis inhibiting agents (AIAs) 6, 7, vascular disrupting agents (VDAs) 8, 9 and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) 10. Moreover, agents that could consume the intratumoral nutrients/oxygen or mediate the essential substances uptake by tumor cells can also lead to tumor “starvation” and necrosis 4, 5, 11, 12. Although some unique advantages have been exhibited for cancer treatment these years, concerns associated with these agents, such as low targeting efficiency, elevated tumor hypoxia, acute coronary syndromes, abnormal ventricular conduction, induced drug resistance and increased tumor metastasis risk, limit their further applications in clinic 13-16.

To overcome these challenges, combination therapy of cancer starvation agents with other cancer treating approaches has demonstrated to be an efficient way, which can maximize the therapeutic efficiency when compared to the single therapeutic method alone 17. However, issues of the free drugs, such as undesirable drug absorption, poor bioavailability and rapid metabolism in vivo, have still been concerned 18. The advances in micro-/nanotechnology as well as cancer biology have boosted development of drug delivery systems for cancer management with enhanced efficacy and limited side effects 19-22. Among them, a variety of nanomaterials based on natural/synthetic polymers 23-29, liposomes 30, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) 13, gold nanoparticles (NPs) 31 and silica NPs 11, 32, 33 have been employed to co-deliver cancer-starving agents and other therapeutics with the aim of reducing drug side effects 23, improving their targeting efficacy 26, 27, increasing the stability and half-life of therapeutics 13, and co-delivery of multiple drugs to overcome the drug resistance 34, 35. Furthermore, cancer-starvation strategy associated with the multimodal nanomedicines have also been developed for achieving synergistic cancer therapy, which has been demonstrated to be the efficient way for overcoming the side effects of free drugs and resulting in superadditive therapeutic effects 14, 15, 20.

There are two major mechanisms in designing starving-nanotherapeutics. One is stopping/reducing the tumor blood supply through inhibiting/disrupting angiogenesis, or directly blocking the blood vessels 11, 23, 26, 36, 37. The other is depriving essential nutrients/oxygen input of tumor cells through consuming the intratumoral nutrients/oxygen, or limiting the critical nutrients uptake 4, 38-40. For maximizing the therapeutic efficiency, these therapeutics were cooperated with other cancer treating approaches, including chemotherapy 41, 42, gene therapy 43, phototherapy 44, 45, gas therapy 46, and immunotherapy 47. Herein, we overview the recent efforts of leveraging nanomedicine-based drug delivery systems for cancer starvation therapy and focus on the major strategies of multimodal synergistic starvation treatments (Figure 1). Both the design principles and their anticancer performance of these formulations are highlighted. Finally, the challenges and future prospects of this field are discussed.

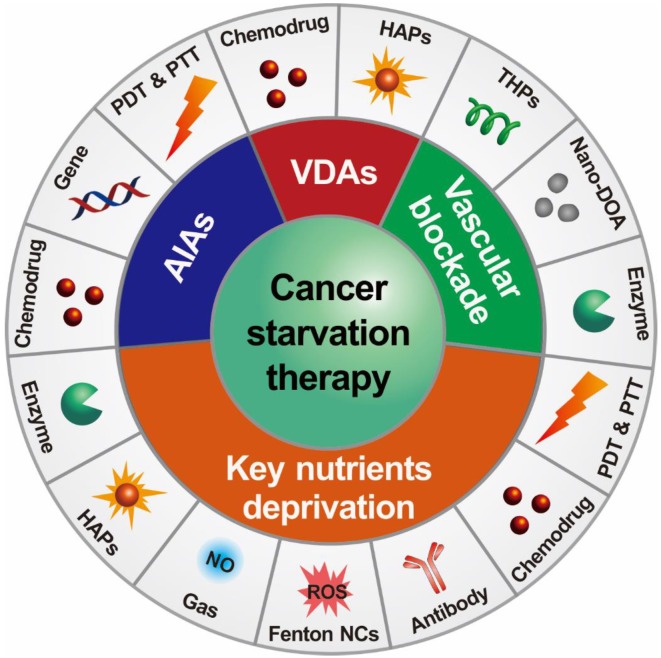

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of nanomedicine-mediated cancer starvation therapy. AIA: angiogenesis inhibiting agent; Nano-DOA: nano-deoxygenation agent; HAP: hypoxia-activated prodrug; NO: nitric oxide; NC: nanocatalyst; PDT: photodynamic therapy; PTT: photothermal therapy; ROS: reactive oxygen species; THP: tumor-homing peptide; VDA: vascular disrupting agent.

2. Nanomedicine-mediated cancer starvation therapy

2.1 Antiangiogenesis-related cancer starvation therapy

Tumor growth and metastasis highly depend on the angiogenesis, which is an essential step of neoplasms from benign to malignant transformation 48. Anti-angiogenic therapy provides an efficient way for arresting the tumor growth through inhibiting the key angiogenic activators 7, 49. Several AIAs have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for clinical cancer treatment since 2003 7. However, associated toxicities of these AIAs are nonnegligible according to the clinical/preclinical investigation, which includes hypertension, vascular contraction, regression of blood vessels and proteinuria 14, 17, 50.

2.1.1 Nano-antiangiogenesis-based cancer monotherapy

Compared to the free AIAs, nanomedicine could both improve their therapeutic outcomes via regulating their release behavior and increasing the drug accumulation in the tumor site through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect as well as actively targeting the tumor and/or endothelial cells via surface conjugation with target ligands 51, 52. For example, mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) could significantly improve the targeting efficacy of tanshinone IIA (an angiogenesis inhibitor) to HIF-1α overexpression, leading to improved antiangiogenesis activity in a mouse colon tumor model (HT-29) 53. Several over-expressed receptors, such as integrin αvβ3 and Neuropilin-1, were employed as the targets of nanomedicines, which showed enhanced targeting efficacy and improved tumor inhibiting rate 54-56. Furthermore, paclitaxel (PTX) loaded antiangiogenic polyglutamic acid (PGA)-PTX-E-[c(RGDfK)2] nano-scaled conjugate could markedly suppressed the growth and proliferation of the αvβ3-expressing endothelial cells (ECs) and several cancer cells 57. Additionally, bevacizumab, an angiogenesis inhibitor against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was directly used as a targeting ligand to modify magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs), which was demonstrated to be an efficient platform for bevacizumab delivery in mice breast tumor (4T1) treatment 58.

Nanonization strategies for AIAs not only could reduce their associated toxicities and enhance the antitumor efficacy to some degree, but also provide a multidrug co-delivery platform toward enhancing the AIAs-based combination anticancer efficacy 31, 34, 59-61.

2.1.2 Synergistic antiangiogenesis/chemotherapy

Angiogenesis inhibitors were often used together with chemotherapeutics for overcoming their shortages and enhancing the antitumor efficacy 17. Recently, types of engineered anti-angiogenic nanotherapeatics have been developed for cancer combination treatment. For instance, doxorubicin (DOX) and mitomycin C (MMC) co-loaded polymer-lipid hybrid nanoparticles could significantly increase the animal survival and tumor cure rate compared with liposomal DOX for treating multidrug resistant human mammary tumor xenografts 34. DOX combining with methotrexate (MTX), which was co-delivered by MSNs could also significantly improve the efficacy of oral squamous cell carcinoma treatment through down-regulating the expression of lymph dissemination factor (VEGF-C) 62. Zhu and coworkers synthesized a matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2)-responsive nanocarrier for the co-delivery of camptothecin (CPT) and sorafenib, which was demonstrated to be an efficient approach for colorectal cancer synergistic therapy 63. Curcumin (Cur), a potent antiangiogenesis agent, was co-loaded with DOX into pH-responsive poly(beta-amino ester) copolymer NPs for the 4T1 tumor treatment, which showed intensive anti-angiogenic and pro-apoptotic activities 64.

2.1.3 Synergistic antiangiogenesis/gene therapy

The co-delivery of antiangiogenesis drugs and gene silencing agents is considered to be another efficient way for cancer starvation therapy 43, 65-67. For example, Lima and coworkers synthesized a chlorotoxin (CTX)-conjugated liposomes for anti-miR-21 oligonucleotides delivery, which promoted the efficiency of miR-21 silencing and enhanced the antitumor activity with less systemic immunogenicity 68. Liu et al. also found that the fusion suicide gene (yCDglyTK) could induce tumor cell apoptosis more effectively after co-delivering with VEGF siRNA by a calcium phosphate nanoparticles (CPNPs), where the density of capillary vessels was also observed to obviously decrease in the xenograft tissue of gastric carcinoma (SGC7901) 67. Furthermore, the poly-VEGF siRNA/thiolated-glycol chitosan nanocomplexes were employed to help overcome the resistant problem of bevacizumab by Kim and coworkers 65. The results indicated that the combination of these two VEGF inhibitors produced synergistic effects with decreased VEGF expression and drug resistance.

2.1.4 Synergistic antiangiogenesis/phototherapy

Nanomaterial-based phototherapies that can selectively kill cancer cells without normal tissue injury have attracted extensive interest in the field of cancer treatments 69-71. Enhanced antitumor efficacy was also observed when angiogenesis inhibitors and phototherapy agents were combined 31, 72. For example, Kim and coworkers developed a hybrid RNAi-based AuNP nanoscale assembly (RNAi-AuNP) for combined antiangiogenesis gene therapy and photothermal ablation (Figure 2) 31. AuNPs modified by single sense/anti-sense RNA strands could self-assemble into various geometrical nanoconstructs (RNAi-AuNP). Then, PEI/RNAi-AuNP complexes were prepared with branched polyethylenimine (BPEI) for the purpose of effective intracellular delivery. After intratumoral administration, the therapeutic effects of PEI/RNAi-AuNP complexes could be activated by continuous-wavelength lasers or high intensity focused ultrasound, which led to effective antiangiogenesis and tumor ablation. In another work, a carrier-free nanodrug was prepared by self-assembling of Sorafenib and chlorin e6 (Ce6) for antiangiogenesis and photodynamic therapy 72. This nanodrug presented good passive targeting behavior in the tumor sites and effective reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation ability in vivo. The tumor inhibition rate was significantly improved after combination with Sorafenib. With additional merits, such as good biosafety and biocompatibility, this nano-integrated strategy promised potential for cancer synergetic treatment in clinic.

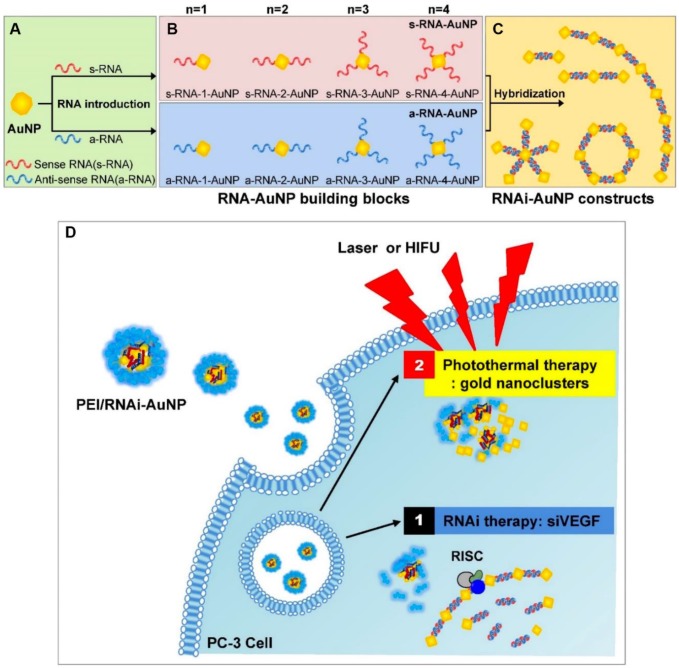

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of antisense- and sense-RNA strands introduction (A), RNA-AuNP building blocks with n-designated numbers of RNA strands (B) and versatile RNAi-AuNP nanoconstructs (C). Illustration of PEI/RNAi-AUNPs-induced the combinational strategy of anti-angiogenesis/photothermal cancer therapy (D). Reproduced with permission from ref. 31. Copyright 2017, Ivyspring international publisher.

2.2 VDAs-based cancer starvation therapy

VDAs, as a unique class of anticancer compounds, is designed to selectively prevent the established abnormal tumor blood vasculature by targeting ECs and pericytes, leading to tumor starvation and central necrosis through hypoxia and nutrient deprivation 73. However, they are powerless to the cancer cells at the tumor margin, which could draw oxygen and nutrients from the surrounding normal tissues 15. Beside this, several other vascular risk factors, such as the acute coronary syndromes, blood pressure alteration, abnormal ventricular conduction, and transient flush, also limit the further application of free VDAs 73. To overcome the above issues and enhance their antitumor ability, VDAs-based multimodal cancer therapies have been developed for solid tumor treatments 23, 27, 28, 42, 74-78.

2.2.1 Free VDAs-enhanced nanomedicine-based chemotherapy

The barriers of heterogeneity and high interstitial fluid pressure of solid tumors not only limit the targeting efficiency of nanomedicines, but also weaken their antitumor ability against the tumor central area 79, 80. Recent studies reported that small free molecule VDAs could help nanomedicines to overcome the above drawbacks 42, 74, 75. For example, Chen and coworkers developed a coadministration strategy using free CA4P and CDDP-loaded PLG-g-mPEG NPs (CDDP-NPs) for complementing each other's antitumor advantages and improving the antitumor efficiency 75. The multispectral optoacoustic tomography (MSOT) images indicated that the tumor penetration of CDDP-NPs highly relied on the tumor vasculature, which aggregated in the peripheral region of the tumors. While co-administration of free CA4P and CDDP-NPs improved the tumor cellular killing efficiency both in the central and peripheral regions according to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The enhanced antitumor efficiency against both murine colon cancer (C26) and human breast cancer (MDA-MB-435) models supported that this combination strategy was a promising way for solid tumor treatment.

Furthermore, small molecule VDAs could induce tumor target amplification of ligand-coated NPs through selectively modifying tumor vasculature. For example, protein p32, a stress-related protein which is specifically expressed on the surface of tumor cells 37, can selectively bind with the phage-displayed cyclic peptide (LyP-1) 81. Ombrabulin, a small molecule VDAs, was used to induce the local upgraded presentation of protein p32 for enhancing the tumor “active targeting” of LyP-1 coated NPs. The in vivo results demonstrated that the recruitment of LyP-1 coated DOX-loaded NPs significantly increased after pretreating with ombrabulin when compared with the control groups 74. In another work, coagulation-targeted polypeptide-based NPs were developed for improving their tumor-targeting accumulation by homing to VDA-induced artificial coagulation environment. The in vivo results showed that this cooperative targeting system recruited over 7-fold higher CDDP doses to the tumors than non-cooperative control groups 42. The above cooperative targeting strategies combining with free VDAs and ligand-coated NPs showed obviously decreased tumor burden and prolonged mice survival compared to the non-cooperative controls.

2.2.2 VDAs-nanomedicine induced synergistic starvation/chemotherapy

VDAs-nanomedicine could enhance their accumulation and retention at the leaky tumor vasculature via EPR effect, leading to high distribution and gradual release of VDAs around the immature tumor blood vessels as well as prolonged vascular disruption effect compared to free drugs 28. Beside this, nanomedicine also provides a platform for VDAs-based cancer multimodal therapy 23, 27, 76, 78. For instance, a multi-compartmental “nanocell” integrating a DOX-PLGA conjugate core and a phospholipid shell was prepared for achieving temporal release of DOX and combretastatin A4 (CA4) 23. After accumulating at the tumor site, CA4 was released from the outer phospholipid shell of the nanocell rapidly and attacked the tumor blood vessels, and DOX was then released subsequently from the inner polymeric core for killing tumor cells directly. This mechanism-based strategy exhibited reduced side toxicity and enhanced therapeutic synergism in the progress of inhibiting murine melanoma (B16F10) and Lewis lung carcinoma growth.

Furthermore, several polymer-VDA conjugates caused amplified TME characteristics was also utilized to develop new cancer co-administration strategies 27, 78. Hypoxia is one of the major features of solid tumors which can promote neovascularization, drug resistance, cell invasion and tumor metastasis 82, 83. Meanwhile, the existence of hypoxia also provides the desired target for tumor selective therapy 21. Tirapazamine (TPZ) is a typical hypoxia-activated prodrug (HAP), which own low toxicity toward normal tissues and can selectively kill the hypoxic cells after conversion into cytotoxic benzotriazinyl (BTZ) radical within hypoxic regions 84. Nevertheless, the insufficient hypoxia level within tumors tremendously limited its further clinical application 85. To address this, Chen and coworkers proposed a cooperative strategy based on VDA-nanomedicine and HAPs for solid tumor treatment (Figure 3) 27. In this study, poly(L-glutamic acid)-CA4 conjugate nanoparticles (CA4-NPs) were employed to selectively disrupt the abnormal vasculature of the tumor, as well as elevating the hypoxia level of the tumor microenvironment (TME). The intensive hypoxic TME further boosted the antitumor efficacy of TPZ subsequently. The in vivo results demonstrated that this combinational strategy can not only completely suppress the small tumor growth (initial tumor volume: 180 mm3), but also obviously keep down the size of large tumors (initial tumor volume: 500 mm3) without distal tumor metastasis. Moreover, Chen and coworkers also demonstrated that the expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9, a typical tumor-associated enzyme) in treated tumors (4T1) could be markedly increased by more than 5-fold after treatment with CA4-NPs. These overexpressed MMP9 could further activate the DOX release from a MMP9-sensitive doxorubicin prodrug (MMP9-DOX-NPs) and enhance the in vivo cooperative antitumor efficacy 78.

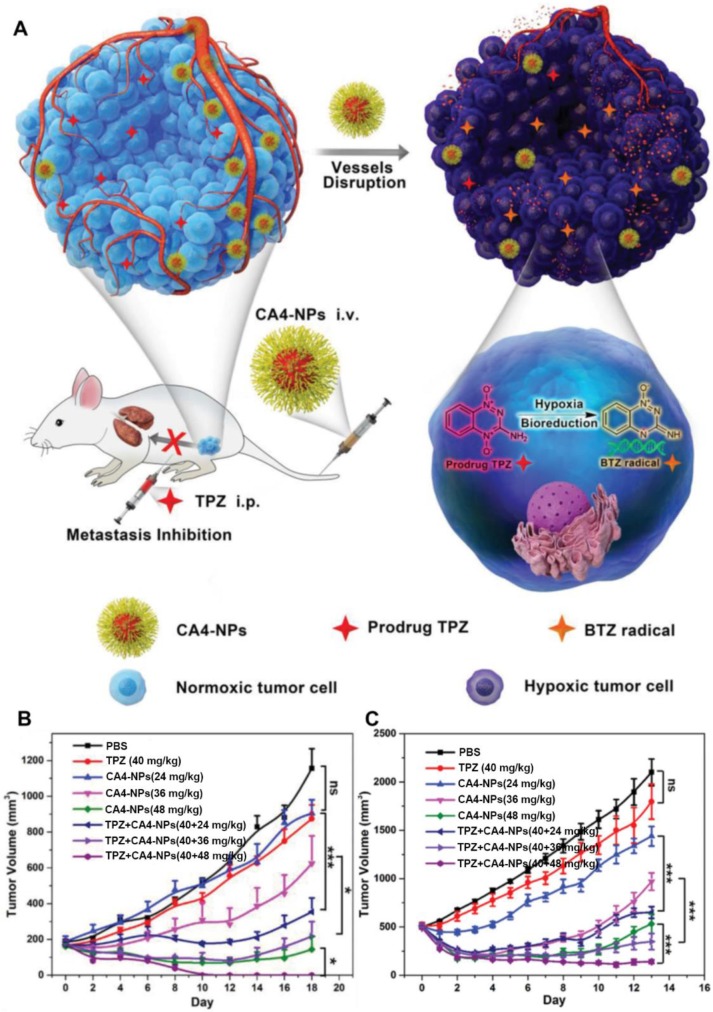

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of hypoxia-inducing VDA nanodrug combined with hypoxia-activated prodrug for cancer therapy (A). Tumor volume changes of BALB/c mice bearing 4T1 tumors with both moderate sizes (≈180 mm3) (n=6). (B). and large sizes (≈500 mm3) (n=6). (C). All data points are presented as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). Reproduced with permission from ref. 27. Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH.

2.3 Vascular blockade-induced cancer starvation therapy

Besides the strategies of anti-angiogenic therapy and VDAs-induced tumor blood vessel disrupting, another promising strategy for cancer starvation therapy was proposed by shutting off the blood supply with nanothereapeutics that could selectively blockade tumor vascular and then inducing tumor necrosis.

2.3.1 Tumor-homing peptides-induced cancer starvation therapy

Tumor-homing peptides (THPs), such as pentapeptide (CREKA) and 9-amino acid cyclic peptide (CLT-1), could specially bind with fibrin-fibronectin complex in tumor blood clots 86. Based on this, Ruoslahti and coworkers developed a CREKA modified IONPs for fibrin-fibronectin complexes targeting and subtle clotting in tumor vessels 87. The initial deposition of these CREKA-IONPs created new binding sites for the subsequent NPs, and further enhanced the blood coagulation in the tumor lesion. The results indicated that the tumor imaging efficiency of this self-amplifying tumor homing system owned about six-fold enhancement compared to the control groups. However, the tumor inhibition efficiency of this system showed no significant improvement due to the insufficient tumor vessel occlusion. To this end, a cooperative theranostic system containing CREKA-IONPs and CRKDKC-coated iron oxide nanoworms was further developed by the same research group for improving the clots binding efficacy. The results proved that this combination system led to 60~ 70% tumor blood blockades and obvious tumor size reduction in vivo 88.

2.3.2 Thrombin-mediated cancer starvation therapy

Thrombin is a serine protease that catalyzes series of coagulation-related reactions and leads to rapid thrombus formation during the clotting process 48. If thrombin can be precisely delivered to the tumor site and lead to selective occlusion of tumor-associated vessels by inducing the local blood coagulation, it might be a promising way for inhibiting the growth and metastasis of tumors. Recently, a nucleolin-targeting multifunctional DNA nanorobotic system was constructed for smart drug delivery. The presence of the nucleolin subsequently triggered the opening of these DNA nanotubes and released the loaded therapeutic thrombin, which then led to specific intravascular thrombosis and tumor vessel blockade at the tumor site 26. The growth of several tumor models was suppressed efficiently after treating with this thrombin-loaded DNA nanorobot, demonstrating that this system could become an attractive platform for cancer starvation therapy in a precise manner.

2.3.3 Deoxygenation agent-induced cancer starvation therapy

It is known that insufficient oxygen (O2) supply could result in hypoxia-induced tumor cell necrosis 89. Based on this, Zhang et al. designed an injectable polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP)-modified magnesium silicide (Mg2Si) nanoparticle as a nano-deoxygenation agent (nano-DOA) for directly consuming the intratumoral O2 and starving tumors 11. This polymer-coated Mg2Si NPs could respond to the slightly acidic TME after the intratumoral injection, and be converted into silicon dioxide (SiO2) by scavenging the surrounding O2 at the tumor site. As a byproduct, the in situ formed SiO2 aggregates further occluded the tumor capillaries and obstructed the follow-up nutrient and O2 supply.

On the other hand, the intratumoral hypoxic level was also enhanced in the progress of O2 consuming with the presence of DOA. Given this reason, Bu and coworkers prepared a TPZ loaded PVP-modified Mg2Si nanoparticles (TPZ-MNPs) for drug delivery and combination cancer therapy 38. After intratumoral injection, the TPZ-MNPs quickly scavenged the O2 in situ and created an artificial anaerobic environment which caused the surrounding cell dormancy. Meanwhile, the released TPZ was activated in this promoted hypoxia TME, which further caused the now-dormant tumor cells death.

2.4 GOx-mediated cancer starvation therapy

Glucose is the major energy supplier for tumor growth and proliferation 90. Glucose oxidase (GOx) can specifically catalyze the conversion of glucose into gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) with the involvement of O2. This reaction can directly consume glucose and O2, and elevate the local acidity, hypoxia and oxidation stress in vivo. Given this background, GOx has aroused considerable interest for cancer diagnosis and treatment in the past decade 4, 91. Nevertheless, there are several limitations of this approach when using GOx as an anticancer agent. On the one hand, the overproduced H2O2 of glucose oxidation can cause systemic toxicity and lethal chain reactions through directly damaging cell membranes, proteins and DNA of normal cells 92, 93. On the other hand, similar glucose supply and physiological requirement of normal cells often lead to off-targeting and ineffective starvation treatment 94. Through nanomedicine, GOx can co-delivery with other therapeutic agents for cancer multimodal treatments 4. Herein, we overview the recent representative GOx-based nanomedicines for cancer starvation therapy.

2.4.1 GOx-based cancer monotherapy

GOx could be used as an antitumor agent alone through consuming the intratumoral glucose and making the tumor “starving”. The continuously generated H2O2 could further lead to DNA damage and tumor cell apoptosis 95, 96. For example, Dinda et al. prepared a GOx-entrapped biotinylated vesicle for active targeting cancer starvation therapy 97. This GOx-containing system showed about six-fold higher tumor cell killing efficiency compared to normal cells through depleting the glucose supply for tumor cells in vitro. However, the glucose depletion efficiency was restrained by the hypoxic TME in vivo, because of the insufficient O2 supply in the solid tumor. Therefore, a hyaluronic acid (HA)-coated GOx and MnO2 coloaded nanosystem (GOx-MnO2@HA) was constructed for enhancing cancer starvation therapy outcome 98. After uptaking by the CD44-expressing tumor cells, the local glucose was converted into gluconic acid and H2O2 with GOx catalysis. The generated H2O2 then reacted with MnO2 to generate O2, which further accelerated the local glucose-consumption. This nanosystem provided benefit to break the hypoxia obstacles and enhance the antitumor effect by GOx.

2.4.2 Synergistic starvation/chemotherapy

As discussed above, the concentration of generated H2O2 can be substantially elevated in the presence of GOx at the lesion site. The increased H2O2 level was exquisitely used to active the H2O2-sensitive prodrugs for enhancing the synergistic efficiency of both cancer starvation and chemotherapy 41, 99. For example, Li et al. prepared a pH-responsive prodrug-based polymersome nanoreactor (GOx@PCPT-NR) that consisted of piperidine group, camptothecin (CPT) prodrug, PEG and GOx for cancer combination therapy (Figure 4) 41. This polymersome nanoreactor owned prolonged blood circulation and high tumor accumulation efficiency. The terminal elimination half-life of GOx@PCPT-NR reached above 39 hours after intravenous injection. This drug delivery system also showed excellent stability and almost no H2O2 and free CPT were found within 48 h treatment in the plasma or liver. Nevertheless, the slight acidity of the tumor (pH = 6.8) could trigger the GOx release from the polymersome, which then catalyzed the conversion of intratumoral glucose into gluconic acid and H2O2. The enhanced acidity causing by the generated gluconic acid could further promote the GOx release, while the elevated H2O2 level could further accelerate the active CPT release. The accumulating effects amplified the combination antitumor efficiency 41. Furthermore, this strategy was further confirmed by another biomimetic cascade nanoreactor (Mem@GOx@ZIF-8@BDOX) in vivo. As a byproduct of GOx-induced glucose depletion, gluconic acid could promote the release of loaded BDOX prodrug from the nano-framework, and the released BDOX were then converted into DOX in the presence of elevated H2O2 at the tumor site 99.

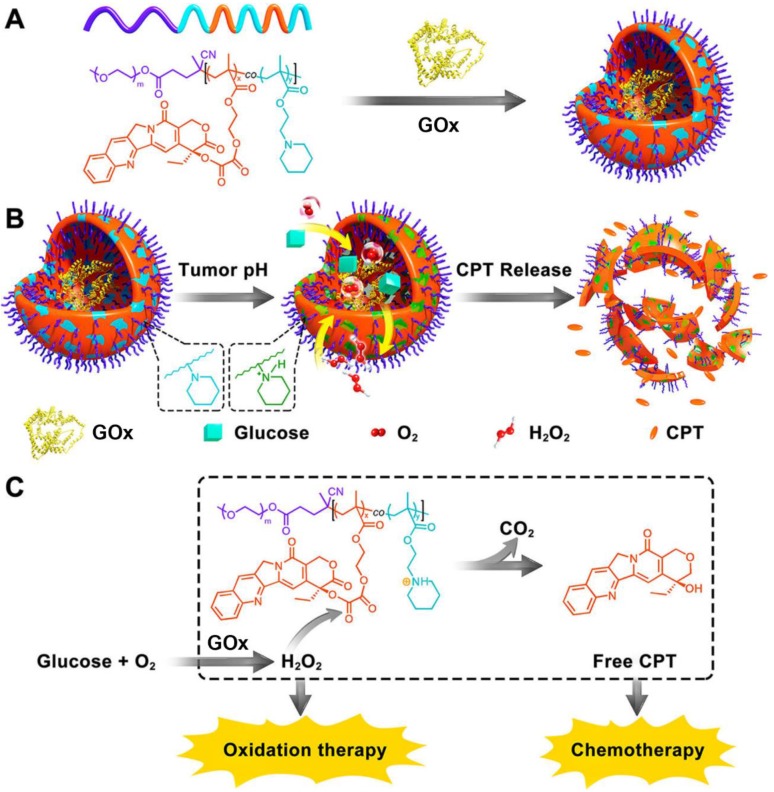

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of the preparation of GOx@PCPT-NR (A). Scheme of cancer starvation/chemotherapy via in situ H2O2 generation and acidity-activated CPT release (B). Molecular mechanism of GOx@PCPT-NR-induced cancer starvation/chemotherapy (C). Reproduced with permission from ref. 41. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society.

2.4.3 GOx-inducing cancer starvation and hypoxia-activated chemotherapy

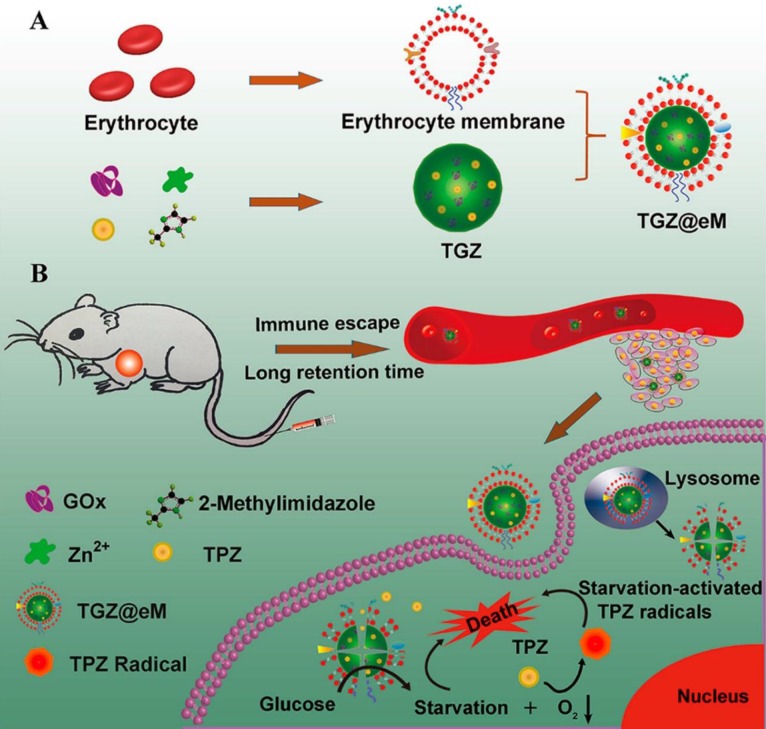

The consummation of molecular oxygen could increase the local hypoxia level in the progress of GOx-involved cancer therapy. This promoted hypoxic microenvironment was also employed to activate the hypoxia-activated prodrugs and amplify their antitumor activity 13, 30, 33, 100. For example, a MOF-based biomimetic nanoreactor coating with erythrocyte membrane (eM) was developed for precise GOx and TPZ delivery and cancer combination therapy (Figure 5) 13. The grafted biomimetic surface of the nanoreactor not only endowed it with prolonged blood circulation and immune-escaping property, but also enhanced the tumor homing efficiency of this nanosystem. After uptake by cells, the released GOx deprived the endogenous glucose and O2, which resulted in amplified hypoxic microenvironment and sufficient activation of TPZ. Based on the above synergistic cascade effects, a colon cancer model were efficiently inhibited in vivo. In another work, the PEG-modified long-circulating liposomes were used to sequentially deliver GOx and banoxantrone dihydrochloride (AQ4N, a hypoxia-activated prodrug) to tumors for cancer combination starvation/chemotherapy 30. The in vivo photoacoustic image indicated that GOx-loaded liposome could obviously deplete the glucose of the tumor site, and lead to tumorous hypoxia enhancement. Under the elevated hypoxic microenvironment, the antitumor activity of the subsequent arrival liposome-AQ4N was activated by reducing low toxic AQ4N into high toxic 1,4-Bis[[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]amino]-5,8-dihydroxyanthracene-9,10-dione (AQ4) by the series of intracellular reductases. Synergistically enhanced antitumor effect was observed on 4T1 murine breast cancer model after treating with this liposome-based GOx/AQ4N co-delivery system. These results demonstrated that combination of GOx-based cancer starvation therapy and HAP-involved hypoxia-activated chemotherapy is an effective way for solid tumor treatment.

Figure 5.

Schematic illustration of preparation of GOx and TPZ coloaded biomimetic nanoreactor with erythrocyte membrane coating (TGZ@eM) (A). TGZ@eM nanoreactor induced cancer starvation/hypoxia-activated chemotherapy (B). Reproduced with permission from ref. 13. Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society.

Furthermore, in order to reduce the systemic toxicity, Wang and coworkers developed a nanoclustered cascaded enzymes by crosslinking GOx and CAT with a pH-responsive block polymer poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) bearing 2-(2-carboxyethyl)-3-methylmaleic anhydride (PEG-b-PHEMACMA) with a BSA/BSATPZ (wt:wt, 1:2) outer shell for cancer starvation and hypoxia-activated chemotherapy 94. The experimental data indicated that GOx and CAT could be released by the stimuli of the mild acidic TME after accumulating at the tumor site. Then, the release rate was self-accelerated by the subsequent generated gluconic acid with GOx-induced glucose consumption. Meanwhile, the aggravated hypoxia of TME further activated the BSATPZ which led to hypoxia-activated chemotherapy. Importantly, the authors also found that the present CAT could timely eliminate the appeared H2O2 as well as lowered the systemic toxicity of GOx-mediated cancer starvation therapy.

2.4.4 Starvation/oxidation synergistic therapy

Glutathione (GSH) is a natural antioxidant in the body, which prevents the damage of important cellular components by ROS, such as H2O2, hydroxyl radicals (∙OH), and singlet oxygen (1O2). However, GSH could weaken the antitumor efficiency in the progress of ROS-mediated cancer therapy. To this end, Li et al. prepared GOx-loaded therapeutic vesicles based on a diblock copolymer containing a mPEG segment and copolymerized piperidine-functionalized methacrylate and phenylboronic ester (mPEG-b-P(PBEM-co-PEM)) 101. After precise activation at the tumor site, the GOx-induced enzymatic reaction caused local consumption of glucose and O2 and generation of gluconic acid and H2O2. The generated H2O2 not only elevated the intracellular oxidative stress, but also led to the production of quinone methide (QM), which further suppressed the antioxidant ability of the tumor cells through depleting the intracellular GSH. These cumulative anticancer effects of the therapeutic vesicles resulted in effective cancer cell death and tumor ablation.

H2O2 can be transformed into the highly toxic ROS under certain conditions in vivo 71, 102. For example, H2O2 could be disproportionated into ∙OH with the presence of Fenton reaction catalysts under acidic condition 103, 104. While, in the presence of neutrophil-expressed phagocytic enzyme myeloperoxidase (MPO), H2O2 and chlorine ion (Cl-) could be converted into hypochlorous acid (HClO) through the enzymatic reaction 105. Based on this, specific strategies were developed to combine with GOx for cancer starvation/oxidation synergistic therapy 106-110.

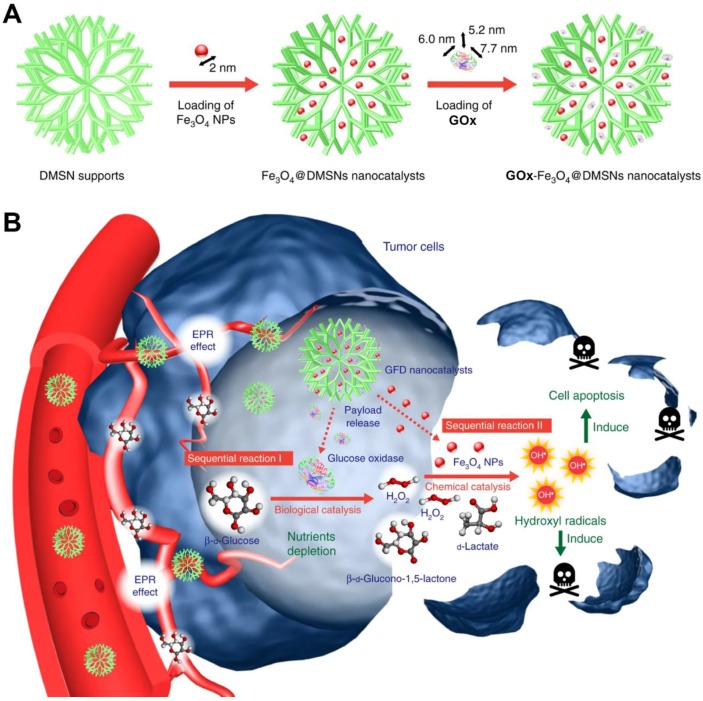

In a recent study, Huo et al. designed a dendritic silica nanoparticle-based sequential nanocatalyst for co-delivering of GOx and Fe3O4 NPs (GOx-Fe3O4@DMSNs) for enhancing of combination anticancer efficiency (Figure 6) 106. After EPR effect-induced accumulation of these nanocatalysts in the tumor site, the released GOx catalyzed the oxidation of the intratumoral glucose to gluconic acid and H2O2 and led to tumor starvation and central necrosis. Thereafter, the generated H2O2 sequentially were translated into highly toxic ∙OH by Fe3O4 NPs under the slightly acidic TME, which resulted in elevated oxidative stress and massive apoptosis of tumor cells. The final tumor inhibition rate of this nanomedicine by intravenous and intratumoral treatments with the same treating dose was reached to 64.7% and 68.9%, respectively. Besides this, another core-shell TME-responsive nanocatalyst, incorporated with a magnetic nanoparticle core of iron carbide (Fe5C2)-GOx and MnO2-nanoshell, was constructed by Lin and co-workers 107. After endocytosis by tumor cells, the MnO2-nanoshell of this nanosystem was degraded into Mn2+ and O2 and resulted in GOx release under the stimuli of the acidic microenvironment. The generated O2 could enhance consumption of the local glucose with the presence of GOx, leading to sufficient tumor starving. Sequentially, the produced H2O2 further evolved into ∙OH catalyzed by Fe5C2, resulting in efficient tumor cell death. Recently, a smart autocatalytic Fenton nanosystem, consisted of GOx-loaded zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-responsive metal polyphenol network (MPN) shell, was designed by Zhang et al. for the combination cancer therapy 108. In tumor cells, the MPN shell was degraded into Fe3+ and tannic acid (TA) and further trigged the inner GOx release under the stimuli of the overexpressed ATP. Then, the exposed GOx led to endogenous glucose consumption and H2O2 accumulation. With the presence of TA, the transition efficiency of Fe3+ to Fe2+ was accelerated, which further promoted the transformation of the generated H2O2 into high toxic ∙OH by Fenton reaction. These accumulating antitumor effects significantly suppressed the tumor growth.

Figure 6.

Synthetic procedure for preparation of GOx-Fe3O4@DMSNs (A). Scheme of GOx-Fe3O4@DMSNs induced sequential catalytic-therapeutic mechanism for cancer therapy (B). Reproduced with permission from ref. 106. Copyright 2017, Nature Publishing Group.

Silver (Ag) ions have been demonstrated to kill different types of cancer cells through increasing the intracellular oxidative stress, causing mitochondrial damage, and inducing cell autophagy 111, 112. Based on this, Huang and coworkers designed a GOx-conjugated silver nanocube (AgNC-GOx) for efficient Ag ions delivery and synergistic starvation/metal-ion therapy 113. AgNC-GOx catalyzed the glucose conversion into gluconic acid and H2O2 after uptake by the tumor cells. Cumulative gluconic acid elevated the acidity of TME which accelerated the AgNC degradation and Ag ions generation in the tumor site. Meanwhile, the generated H2O2 and Ag ions were found to lead the eradication of 4T1 cancer cells. Both the glucose consumption and accumulation of toxic H2O2 and Ag ions significantly suppressed the tumor growth and prolonged the mice survival.

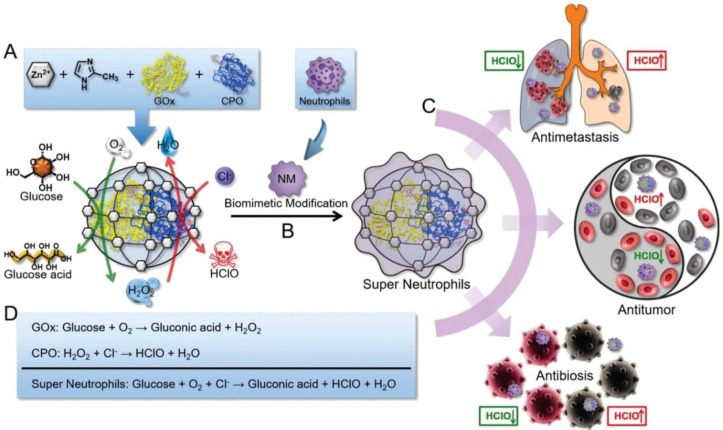

HClO is a powerful ROS which can be generated by the MPO-mediated catalysis and owns higher cellular toxicity in comparison with H2O2. It has been proved to be a promising candidate for cancer therapy through disrupting some cellular functions and promoting the tumor cell death by the oxidation progress 114. Given this pattern, Zhang and coworkers prepared an “artificial neutrophils”, consisting of GOx and chloroperoxidase (CPO) coloaded zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) core and neutrophil membrane (NM) coating (GOx-CPO@ZIF-8@NM), for both of cancer and infection treatments. NM coating help the NPs to target the tumor site efficiently (Figure 7) 109. After uptake by the tumor cells, the embedded GOx and CPO were released from the ZIF-8 NPs, which synergistically enhanced the glucose depletion and HClO generation through a sequential enzymatic catalysis progress. According to the results, this artificial neutrophil can produced seven-fold higher reactive HClO than the natural neutrophils both in vitro and in vivo. Benefit from this, 4T1 tumors of mice was almost completely eradicated after treating with this neutrophil-mimicking NPs.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the synthesis of GOx and CPO-coloaded ZIF-8 NPs. Glucose conversation and HClO generation with the catalyzing of GOx and CPO (A). Preparation of the “artificial neutrophils” by the surface modification of the GOx/CPO-coloaded ZIF-8 NPs with natural neutrophil membrane (B). Compare to natural neutrophils, the “artificial neutrophils” showed stronger HClO generation ability for biomedical applications (C). The mechanism of enzymatic reaction of GOx, CPO and “artificial neutrophils” (D). Reproduced with permission from ref. 109. Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH.

2.4.5 Synergistic starvation/phototherapy

Blue light irradiation (450~490 nm) could promote the Conversion of H2O2 into more toxic ∙OH, which provides an alternative approach for cancer therapy. However, insufficient H2O2 supplies in the tumor site weaken the ∙OH production as well as the antitumor efficiency. Instead, GOx, as an antitumor agent, could induce the glucose depletion and tumor starvation with consecutively generating of H2O2. Given this fact, Chang et al. developed GOx-conjugated polymer dots (Pdot-GOx) for enzyme-enhanced phototherapy (EEPT) 115. After immobilizing into tumor, Pdot-GOx NPs could efficiently catalyze the glucose oxidation and steadily produce H2O2, which led to the enhancement of the local oxidative stress. Meanwhile, the appeared H2O2 could also be photolyzed to produce ∙OH under light irradiation (460 nm) for killing tumor cells. The experimental results indicated that this EEPT strategy exhibited much higher efficacy in inhibiting MCF-7 tumor growth compared with the control groups in mouse models.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has proved to be a promising platform in imaging and treatment of cancers and other diseases 116. As a noninvasive method, PDT utilizes the generated toxic ROS to destroy the cellular organelles and ablate tumors with the presence of photosensitizers under light irradiation. However, the poor penetration of the excitation light makes it powerless against deeply seated tumors 117. Besides, hypoxia of TME is another suppressive factor for this O2-dependent antitumor approach 118. Thus, the combination with other strategies would be an alternative way for improving the efficiency of PDT-involved cancer therapy 119, 120. Recently, Li et al. developed a GOx and catalase co-loaded porphyrin metal-organic framework with tumor cell membrane surface coating (mCGP) for synergistic starvation/PDT therapy. This mCGP NPs owned excellent tumor homing ability due to the tumor cell membrane surface coating. After internalized by tumor cells, the loaded catalase in mCGP was found to catalyze the generated H2O2 to disproportionate into molecular O2 and H2O, accelerating the consumption of endogenous glucose and promoting the production of 1O2 under light irradiation. These accumulating effects obviously enhanced the in vivo synergistic antitumor efficiency of mCGP NPs. In another work, Yu et al. developed a biomimetic nanoreactor (bioNR)-based starvation/PDT strategy for effective combating deeply seated metastatic tumors 32. The bioNR was constructed based on a GOx and Ce6 conjugated hollow mesoporous silica NPs (HMSNs) with B16F10 cell membrane coating, which was filled with bis[2,4,5-trichloro-6-(pentyloxycarbonyl)phenyl]oxalate (CPPO) and perfluorohexane (PFC) in the cavity. After homing to the tumor, the peripheral glucose was converted into gluconic acid with H2O2. At the same time, the appeared H2O2 not only promoted the local oxidative stress of the tumor, but also could react with CPPO to generate chemical energy, which led to chemiluminescence resonance energy transfer-based PDT with the presence of Ce6. Furthermore, the molecular oxygen releases from PFC further increase the antitumor efficiency of O2-dependent GOx-involved cancer starvation therapy and PDT. It was demonstrated that the Ce6-induced PDT effect for tumor metastasis was substantially enhanced after combination with GOx-involved cancer starvation therapy.

As described above, insufficient oxygen supply in solid tumors could limit the antitumor efficiency of GOx-related therapeutics. To address this challenge, Cai and coauthors prepared a HA-conjugated porous hollow Prussian Blue NPs (PHPBNs) for facilitating GOx delivery and tumor synergistic starvation/photothermal therapy 121. The HA shell could enhance the targeting efficiency towards CD44 overexpressing tumors. After cellular endocytosis, the released GOx catalyzed the glucose depletion by consuming O2, and PHPBNs sequentially catalyzed the generated H2O2 splitting into O2 and H2O to amplify the tumor starvation effect. Furthermore, GOx-induced glucose depletion not only inhibited the tumor growth, but also suppressed the expression of heat shock proteins (HSPs), where the latter facilitated PHPBNs-mediated low-temperature photothermal treatment to reduce their resistance. The results indicated that this combinational therapeutic system could significantly repress tumor growth in mice. In another work, Tang et al. developed a novel BSA-directed two-dimensional (2D) MnO2 nanosheet (M-NS) by one-step method 122. This M-NS not only owned an excellent GOx-like activity for catalyzing the local glucose oxidation, but also exhibited high photothermal conversion efficiency due to the large surface area. Furthermore, this M-NS artificial enzyme showed higher thermal stability than natural GOx. The experimental results indicated that the M-NS-induced intratumoral glucose depletion inhibited the ATP production as well as cellular HSPs expression, which promoted the sensitivity of tumors to the M-NS-mediated photothermal treatments.

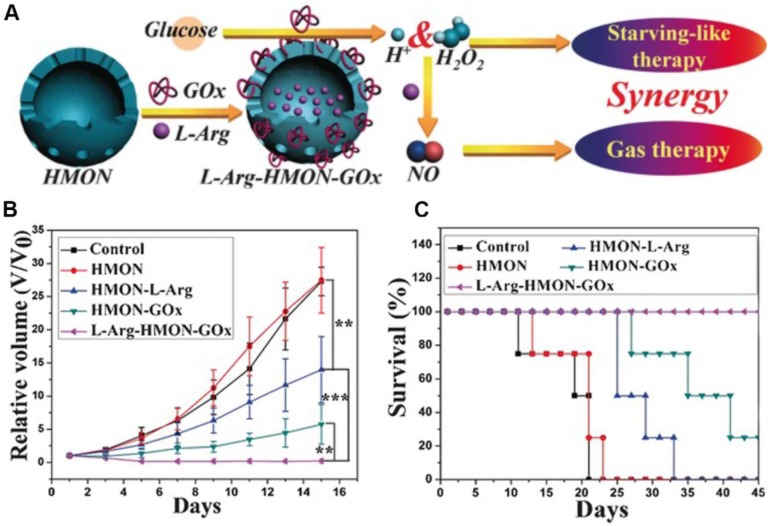

2.4.6 Starvation/gas synergistic therapy

Previous studies have demonstrated that nitric oxide (NO) could be used as a therapeutic gas for cancer therapy through the nitrosation of mitochondria and DNA or enhance the efficiency of PDT or radiation therapy123, 124. L-Arginine (L-Arg) is a natural NO donor which can release NO in the presence of inducible NO synthase enzyme (iNOS) or in the presence of H2O2 125, 126. Given this reality, Fan et al. employed a hollow mesoporous organosilica nanoparticle (HMON) for GOx and L-Arginine co-delivery (L-Arg-HMON-GOx) and cancer starvation/gas therapy (Figure 8) 46. After accumulating at the tumor site, the intratumoral glucose was transformed into gluconic acid and H2O2 by GOx. The generated H2O2 not only killed the tumor cells directly, but also enhanced the gas therapy effect through oxidizing L-Arginine into NO in the acidic TME. The in vivo experimental results indicated that L-Arg-HMON-GOx treated U87MG tumor bearing mice have the best tumor ablation outcome and much longer survival rate than the control groups, indicating the significantly promoted synergistic starvation/gas therapy effects.

Figure 8.

The schematic illustration of the preparation of L-Arg-HMON-GOx for cancer starvation/gas synergistic therapy (A). Tumor volume changes (B) and survival curves (C) of U87 tumor bearing mice after different treatments (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). Reproduced with permission from ref. 46. Copyright 2017, Wiley-VCH.

2.4.7 GOx-mediated starvation/immunotherapy

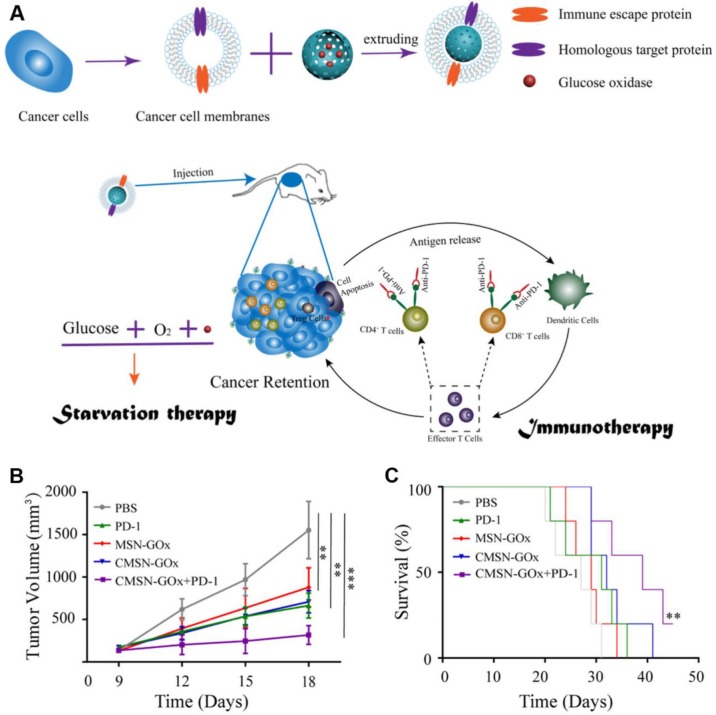

Although cancer immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy has been witnessed exciting progress in treating many types of cancers in clinic, several remaining challenges still need to be overcome in ICB-related cancer immunotherapy, such as low immune response efficacy, off-target side effects, and immune suppressive factors in TME 127-131. Combination of cancer immunotherapy with other anticancer methods has been considered as an efficient strategy for addressing these issues 132-138. For example, Xie et al. presented a therapeutic method combing with cancer cell membrane coated GOx-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles (CMSN-GOx) and anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (anti-PD-1) for cancer starvation/immunotherapy (Figure 9) 47. Contributing to the CM coating, CMSN-GOx was efficiently delivered to the tumor site. The released GOx could not only catalyze the glucose depletion to inhibit the tumor growth, but also induce more dendritic cells (DCs) maturation which further enhanced the antitumor efficacy of anti-PD-1. In vivo experimental results indicated that CMSN-GOx plus anti-PD-1 combination treatment provided more effective tumor suppression than any single therapies.

Figure 9.

Schematic illustration of CMSN-GOx induced cancer starvation/immunotherapy (A). Tumor volume changes (n=5). (B). and survival curves (n=5). (C). Of B16F10 tumor bearing mice after different treatments. All data points are presented as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001). Reproduced with permission from ref. 47. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society.

2.4.8 GOx-involved multimodal synergistic therapy

As previously reported, H2O2 generated in the GOx-induced glucose oxidation could split into high toxic ∙OH radicals through Fenton reaction in the presence of Fe3O4106. The rising tumor temperature could further elevate the conversion efficiency of local H2O2 to ∙OH as well as enhance the antitumor ablation 71. Given this fact, Feng et al. developed a Fe3O4/GOx co-loaded polypyrrole (PPy)-based composite nanocatalyst (Fe3O4@PPy@GOx NC) for multimodal cancer therapy. Fe3O4@PPy@GOx NCs could selectively accumulate at the tumor site (4T1) via EPR effect. Thereafter, the released GOx-mediated intratumoral glucose oxidation elevated the H2O2 level and acidity of TME, which sequentially resulted in local ∙OH accumulation and tumor cell death. At the same time, the polypyrrole (PPy) component which owned a high photothermal-conversion efficiency (66.4% in NIR-II biowindow) considerably increased the tumor temperature in both in NIR-I and NIR-II biowindows, which accelerated the H2O2 disproportionation as well as enhanced the photothermal-enhanced cancer starvation/oxidation therapy.

2.5 Other strategies for cancer starvation therapy

Recently, types of special strategies in this field, which aimed at some critical nutrients, such as lactate and cholesterol, were also developed 39, 40, 139-141.

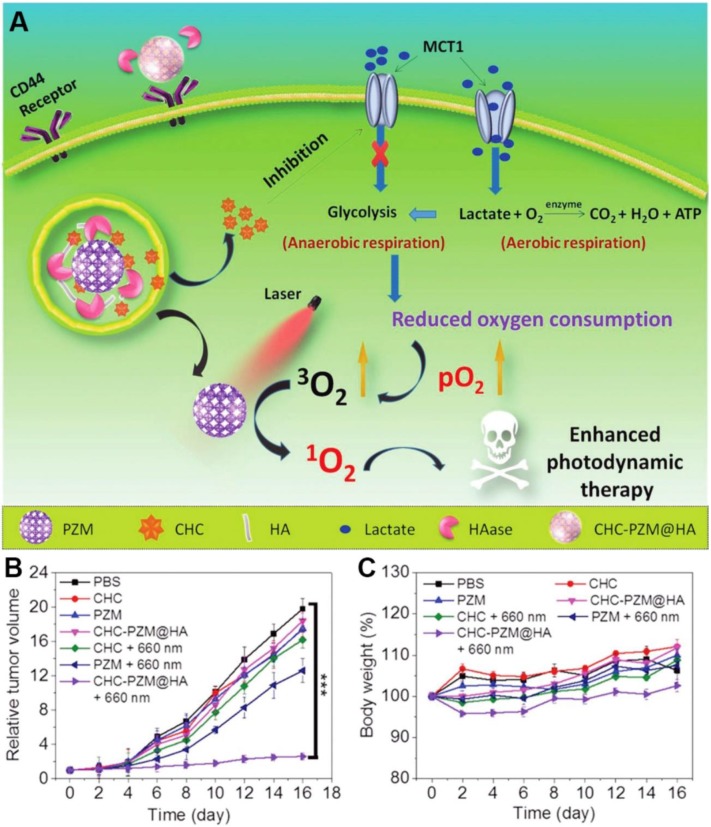

Lactate, which was once considered to be the waste product of glycolysis, has been demonstrated that can “fuel” the oxidative tumor cells growth as an energy substrate 12, 142. Investigation indicated that interfering the lactate-fueled respiration could selectively kill the hypoxic tumor cells via inhibiting the expression of lactate-proton symporter, monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) 143. Meanwhile, the reduction of lactate uptake by inhibiting the expression of MCT1 could transform the lactate-fueled aerobic respiration to anaerobic glycolysis as well as lower the O2 consumption in tumor cells which would facilitate the O2-depleting cancer therapy. For example, Zhang and coworkers developed an α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamate (CHC) loaded porous Zr (IV)-based porphyrinic metal-organic framework (PZM) NPs with HA coating for cancer combination therapy (Figure 10) 40. After effectively accumulating at the CT26 tumors, the released CHC could obviously decrease the expression of MCT1 and turn down the lactate uptake which leading to lower the O2 consumption. As a result, the PDT efficiency was markedly enhanced due to the sufficient 3O2 converting upon the laser irradiation (600 nm). Additionally, reducing the production of lactate via knockdown of lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) in tumor cells was also demonstrated that could neutralize of the tumor acidity and enhance the anti-PD-L1-mediated immunotherapy 139.

Figure 10.

Schematic illustration of porphyrinic MOF nanoplatform mediated suppressing lactate-fueled respiration for enhanced PDT therapy (A). Tumor volume changes (n=5). (B). and body weight curves (n=5). (C). Of CT26 tumor bearing mice after different treatments. All data points are presented as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). (***P<0.001). Reproduced with permission from ref. 40. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH.

Recently, Thaxton and coworkers designed synthetic high density lipoprotein nanoparticles (HDL-NPs) with gold NPs as a size- and shape-restrictive template for lymphoma starvation therapy 39. This HDL-NPs could specially target scavenger receptor type B-1 (SR-B1), which is a high-affinity HDL receptor expressed by lymphoma cells. This combination of SR-B1 promoted the cellular cholesterol efflux and limited the cholesterol delivery, which selectively induced cholesterol starvation and cell apoptosis. The B-cell lymphoma growth was obviously inhibited after HDL-NPs treatment of B-cell lymphoma bearing mice. Furthermore, this HDL-NPs could reduce the activity of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), a type of innate immune cells that potently inhibit T cells, through specifically binding with SR-B1of MDSCs 140. In Lewis lung carcinoma mice model, the in vivo data showed that the suppression of MDSCs by HDL-NPs markedly increased CD8+ T cells and reduced Treg cells in the metastatic TME. After treating with HDL-NPs, the tumor growth and metastatic tumor burden were obviously reduced and the survival rate was clearly improved due to enhanced adaptive immunity.

3. Conclusion and outlook

As an attractive strategy for cancer treatment, nanomedicine-mediated cancer starvation therapy could selectively deprive the nutrients and oxygen supply through antiangiogenesis treatment, tumor vascular disrupting or blockade, direct depletion of the intratumoral glucose and oxygen, and other processes. Moreover, by combining with chemotherapeutic drugs, therapeutic genes, enzymes, metal NPs, hypoxia-activated prodrugs, inorganic NPs, Fenton-reaction catalysts, photosensitizers, or photothermal agents, two or more therapeutic agents could be readily integrated into one single formulation, leading to enhanced treatment outcomes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Representative formulations for nanomedicine-mediated cancer starvation therapy described in this review.

| Strategies | Materials | Therapeutics | Administration route | Treatments | Tumor models | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antiangiogenesis-related cancer starvation therapy | αvβ3-integrin targeted perfluorocarbon NPs | Docetaxel-prodrug | i.v. injection | Antiangiogenesis therapy | Vx2 tumor bearing rabbits | 54 |

| Chitosan NPs | Ursolic acid | Oral administration | Antiangiogenesis therapy | H22 tumor bearing mice | 145 | |

| PGA-PTX-E-[c(RGDfK)2] | PTX | i.v. injection | Antiangiogenesis therapy | 4T1 tumor bearing mice | 57 | |

| Recombinant human endostatin conjugated AuNPs | Recombinant human endostatin | Subcutaneous injection | Antiangiogenesis therapy | SW620 tumor bearing mice | 146 | |

| MSNs | Tanshinone IIA | i.v. injection | Antiangiogenesis therapy | HT-29 tumor bearing mice | 53 | |

| M-MSN@PEI-PEG-KALA NPs | anti-VEGF siRNA | i.v. injection | Antiangiogenic gene therapy | A549 tumor bearing mice | 43 | |

| αvβ3-integrin-targeted lipid-encapsulated NPs | Fumagillin prodrug and zoledronic acid | i.v. injection | Dual antiangiogenic therapy | Vx2 tumor bearing rabbits | 55 | |

| Thiolated-glycol chitosan formed NPs | Bevacizumab and poly- anti-VEGF siRNA | i.v. injection | Dual antiangiogenic therapy | A431 tumor bearing mice | 65 | |

| Polymer-lipid hybrid NPs | DOX and MMC | i.v. injection | Antiangiogenesis therapy and chemotherapy | MDA-MB 435/LCC6/WT tumor bearing mice and MDA-MB 435/LCC6/MDR1 tumor bearing mice | 34 | |

| pH and thermo-responsive MSNs | DOX and MTX | i.v. or oral administration | Antiangiogenesis therapy and chemotherapy | OSCC tumor bearing mice | 62 | |

| PEGylated lipid bilayer-supported MSNs | AXT and CST | i.v. injection | Antiangiogenesis therapy and chemotherapy | SCC7 tumor bearing mice | 147 | |

| MMP-2 responsive mPEG-peptide diblock copolymer (PPDC) NPs | CPT and Sorafenib | i.v. injection every | Antiangiogenesis therapy and chemotherapy | HT-29 tumor bearing mice | 63 | |

| pH-sensitive poly(beta-amino ester) copolymer NPs | DOX and Cur | i.v. injection | Antiangiogenesis therapy and chemotherapy | SMMC 7721 tumor bearing mice | 64 | |

| Captopril-polyethyleneimine conjugated AuNPs | Captopril and siRNA | i.v. injection | Antiangiogenesis and gene therapy | MDA-MB-435 tumor bearing mice | 66 | |

| Calcium phosphate NPs | anti-VEGF shRNA and yCDglyTK | Intraperitoneal or intratumoral administration | Antiangiogenic gene therapy and suicide gene therapy | SGC7901 tumor bearing mice | 67 | |

| CTX-coupled SNALP-formulated anti-miR-21 oligonucleotides | CTX and anti-miR-21 | i.v. or oral administration | Antiangiogenesis therapy and gene therapy | GBM tumor bearing mice | 68 | |

| RhoJ antibody modified Au@I NPs | RhoJ antibody | i.v. injection | Antiangiogenesis therapy and radiotherapy | Patient-derived tumor xenografts | 61 | |

| AuNPs | anti-VEGF siRNA | Intratumoral injection and laser irritation (655 nm) | Antiangiogenic gene therapy and photothermal therapy | PC-3 tumor bearing mice | 31 | |

| Near infrared probe iron oxide NPs | Bevacizumab | i.v. injection | Antiangiogenesis therapy and imaging | 4T1 tumor bearing mice | 58 | |

| Sorafenib and Ce6 formed carrier-free NPs | Sorafenib and Ce6 | i.v. injection and laser irritation (660 nm) | Antiangiogenesis therapy and photodynamic therapy | HSC3 tumor bearing mice | 72 | |

| VDAs-based cancer starvation therapy | ||||||

| DOX-PLGA-conjugate NPs | Free CA4 and DOX | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and chemotherapy | Lewis lung carcinoma xenografts and B16F10 tumor bearing mice | 23 | |

| LyP-1 coated liposomes | Free Ombrabulin and DOX | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and chemotherapy | MDA-MB-435 tumor bearing mice | 74 | |

| Poly(L-glutamic acid)-g-mPEG NPs | Free CA4P and CDDP | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and chemotherapy | MDA-MB-435 tumor bearing mice | 75 | |

| A15-PGA-CDDP NPs | Free DMXAA and CDDP | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and chemotherapy | C26 tumor bearing mice | 42 | |

| CA4-NPs | CA4 | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy | C26 tumor bearing mice | 28 | |

| mPEG-b-PHEA-DMXAA conjugate NPs | DMXAA and DOX | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and chemotherapy | MCF-7 tumor bearing mice | 76 | |

| CA4-NPs | CA4 and TPZ | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and chemotherapy | 4T1 tumor bearing mice | 27 | |

| CA4-NPs and MMP9-DOX-NPs | CA4 and DOX | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and chemotherapy | 4T1 and C26 tumor bearing mice | 78 | |

| Vascular blockade-induced cancer starvation therapy | CREKA modified IONPs and CRKDKC modified iron oxide nanoworms | Two tumor-homing peptide of CREKA and CRKDKC | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy | 22Rv1 tumor bearing mice | 88 |

| DNA nanorobots | Thrombin | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy | MDA-MB-231 tumor bearing mice | 26 | |

| PVP-modified Mg2Si NPs | Mg2Si | Intratumoral injection | Starvation therapy | 4T1 tumor bearing mice | 11 | |

| TPZ-MNPs | Mg2Si and TPZ | Intratumoral injection | Starvation therapy and hypoxia-activated chemotherapy | 4T1 tumor bearing mice | 38 | |

| GOx-mediated cancer starvation therapy | GOx-MnO2@HA NPs | GOx and MnO2 | Intratumoral injection | Starvation therapy | CT-26 tumor bearing mice | 98 |

| Large pore-sized dendritic silica NPs | GOx and Fe3O4 NPs | Intratumoral or i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and oxidation therapy | 4T1 and U87 tumor xenografts | 106 | |

| PEG-b-P(PBEM-co-PEM) NPs | GOx and QM | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and oxidation therapy | A549 tumor bearing mice | 101 | |

| Poly(FBMA-co-OEGMA) nanogels | GOx | Intratumoral injection | Starvation therapy and oxidation therapy | C8161 tumor bearing mice | 96 | |

| Fe5C2-GOx@MnO2 NCs | GOx, Fe5C2 and MnO2 | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and oxidation therapy | U14 and 4T1 tumor bearing mice | 107 | |

| GOx-CPO@ZIF-8@NM NPs | GOx and CPO | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and oxidation therapy | 4T1 tumor bearing mice | 109 | |

| ATP-responsive GOx@ZIF@MPN NPs | GOx and Fe(III)/Fe(II) | Intratumoral injection e | Starvation therapy and oxidation therapy | 4T1 tumor bearing mice | 108 | |

| FDMSNs@GOx@HA | GOx and Ferrocene | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and oxidation therapy | HeLa tumor bearing mouse | 148 | |

| GOx@PCPT-NR | GOx and CPT prodrug | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and chemotherapy | A549 tumor bearing mice | 41 | |

| Mem@GOx@ZIF-8@BDOX) NPs | GOx and BDOX | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and chemotherapy | 4T1 tumor bearing mice | 99 | |

| MSNs-GOx/PLL/HA | GOx and PTX | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and chemotherapy | HepG2 tumor bearing mice | 149 | |

| Yolk-shell tetrasulfide bond bridged dendritic MONs | GOx and AQ4N | Intratumoral injection o | Starvation therapy and hypoxia-activated chemotherapy | 4T1 tumor bearing mice | 33 | |

| TGZ@eM NRs | GOx and TPZ | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and hypoxia-activated chemotherapy | CT26 tumor bearing mice | 13 | |

| HA-coated CaCO3 NPs | GOx and TPZ | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and hypoxia-activated chemotherapy | CT26 tumor bearing mice | 100 | |

| Liposomes | GOx and AQ4N | Intratumoral injection | Starvation therapy and hypoxia-activated chemotherapy | 4T1 tumor bearing mice | 30 | |

| BCETPZ@(GOx+CAT) | GOx, CAT and TPZ | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and hypoxia-activated chemotherapy | EMT-6 tumor bearing mice | 94 | |

| GOx conjugated polymer dots | GOx | Intratumoral injection and laser irritation (460 nm) | Starvation therapy and photodynamic therapy | MCF-7 tumor bearing mice | 115 | |

| Mem@catalase@GOx@PCN-224 bioreactor | GOx, CAT and TCPP | i.v. injection and laser irritation (660 nm) | Starvation therapy and photodynamic therapy | 4T1 tumor bearing mice | 44 | |

| HMSNs | GOx and Ce6 | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and photodynamic therapy | B16F10 metastatic tumor bearing mice | 32 | |

| Hollow-MnO2-GOx-Ce6@CM | GOx, MnO2 and Ce6 | i.v. injection and laser irritation (655 nm) | Starvation therapy and photodynamic therapy | B16F10 tumor bearing mice | 150 | |

| rMGB | GOx, MnO2 and Ce6 | i.v. injection and laser irridation (660 nm) | Starvation therapy and photodynamic therapy | 4T1 cancer bearing mice | 120 | |

| PEGylate HA-functionalized PHPBNs | GOx | i.v. injection and NIR laser irritation (808 nm) | Starvation therapy and photothermal therapy | HepG2 tumor bearing mice | 121 | |

| BSA-directed two-dimensional MnO2 nanosheet | MnO2 | i.v. injection and NIR laser irritation (808 nm) | Starvation therapy and photothermal therapy | U87MG tumor bearing mice | 122 | |

| GOx-conjugated silver nanocubes | GOx and Ag ions | Intratumoral injection | Starvation therapy and metal ion therapy | 4T1 tumor bearing mice | 113 | |

| HMONs | L-Arg and GOx | Intratumoral injection | Starvation therapy and gas therapy | U87MG tumor bearing mice | 46 | |

| CMSNs | GOx and anti-PD-1 | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and immunotherapy | B16F10 tumor bearing mice | 47 | |

| Fe3O4@PPy@GOx NCs. | GOx, Fe3O4 NPs and PPy | i.v. injection and NIR laser irradiation (808 or 1064 nm) | Starvation therapy, oxidation therapy and photodynamic therapy | 4T1 tumor bearing mice | 45 | |

| CPT@MOF(Fe)-GOx | GOx, Fe3+ and CPT | Intratumoral injection | Starvation therapy, oxidation therapy and chemotherapy | HeLa tumor bearing mice | 151 | |

| MGH nanoamplifier | GOx and MIL-100 | i.v. injection, NIR laser irradiation (808 nm) | Starvation therapy, oxidation therapy, photothermal therapy and imaging | 4T1 tumor bearing mice | 110 | |

| Other strategies for cancer starvation therapy | HDL-AuNPs | HDL | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy | B-cell lymphoma xenografts | 39 |

| HDL-AuNPs | HDL | i.v. injection | Starvation therapy and immunotherapy | LLC tumor bearing mice and melanoma metastatic lung colonization mice model | 140 | |

| CHC-PZM@HA | CHC and PZM | i.v. injection, laser irradiation (660 nm) | Starvation therapy and photodynamic therapy | CT26 tumor bearing mice | 40 | |

| Mn-D@BPFe-A NPs | DOX, Fe3+ | Starvation therapy, chemotherapy and photodynamic therapy | HepG2 tumor bearing mice | 141 |

However, most innovations in this field are still in their infancy, with underlying challenges regarding clinical translation that need to be assessed in detail. For example, the biosafety of these nanomaterials is still significantly concerned, especially for the non-biodegradable formulations. Although the biosafety assessment of these materials could be systematically evaluated through animal models, long-term internal metabolic behaviors and related toxicity should be thoroughly investigated before clinical application. Another major concern is the aggravating hypoxia level that may accelerate the tumor invasion and metastasis in the progress of tumor starvation therapy. Detailed studies should be performed to confirm whether cancer starvation therapy could turn on the tumor metastasis switch by elevating the hypoxic TME, which would also help to develop new combination strategies for offering synergistic effects. Moreover, in addition to elevating the hypoxia level, these cancer starvation-based methods could also increase the intratumoral acidity and/or promoting the intracellular oxidative stress. It remains unknown how these changes influence the local and systemic immune responses. The advances in cancer immunotherapy would offer new insights and perspectives for further evolving cancer starvation-based treatments 144.

4. Abbreviations

Table 2.

List of abbreviations

| ∙OH | Hydroxyl radical |

| 1O2 | Singlet oxygen |

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| 4T1 | Mice breast tumor cell line |

| 22Rv1 | Human prostate cancer cell line |

| A431 | Human epidermoid carcinoma cell line |

| A549 | Human lung cancer cell line |

| Ag | Silver |

| AIA | Angiogenesis inhibiting agent |

| anti-PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 antibody |

| anti-PD-L1 | Programmed cell death ligand 1 antibody |

| AQ4N | Banoxantrone dihydrochloride |

| AXT | Axitinib |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| Au NP | Gold nanoparticle |

| B16F10 | Mouse melanoma cell line |

| BDOX | H2O2-sensitive doxorubicin prodrug |

| BPEI | Branched polyethylenimine |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| BCE | PEG-b-PHEMA crosslinked CPZ loaded BSA and CAT/GOx nanoclustered enzymes |

| C26 | Murine colon cancer cell line |

| C8161 | Human melanoma cell line |

| CT26 | Mouse colon cancer cell line |

| CA4 | Combretastatin A4 |

| CA4P | Combretastatin A4 disodium phosphate |

| CA4-NPs | Poly(L-glutamic acid)-CA4 conjugate nanoparticles |

| CDDP | Cisplatin |

| Ce6 | Chlorin e6 |

| CHC | α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamate |

| CM | Cell membrane |

| CMSNs | Cancer cell membrane coated mesoporous silica nanoparticles |

| CPNP | Calcium phosphate nanoparticle |

| CPO | Chloroperoxidase |

| CPPO | Bis[2,4,5-trichloro-6-(pentyloxycarbonyl)phenyl]oxalate |

| CPT | Camptothecin |

| CST | Celastrol |

| CTX | Chlorotoxin |

| Cur | Curcumin |

| DDS | Drug delivery system |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| DMXAA | 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid |

| DOX | Doxorubicin |

| ECs | Endothelial cells |

| EEPT | Enzyme-enhanced phototherapy |

| eM | Erythrocyte membrane |

| EMT-6 | Mouse mammary cancer cell line |

| EPR | Enhanced permeability and retention |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FDMSNs | Ferrocene-functionalized dendritic mesoporous silica nanoparticles |

| GBM | Human glioblastoma cell line |

| GO | Graphene oxide |

| GOx | Glucose oxidase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| HA | Hyaluronic acid |

| HAP | Hypoxia-activated prodrug |

| HDL | High density lipoprotein |

| HFR | Heparin-folic acid-retinoic acid conjugate |

| HMON | Hollow mesoporous organosilica nanoparticle |

| H22 | Mouse hepatocellular carcinoma cell line |

| HepG2 | Human liver cancer cell line |

| HSC3 | Human oral squamous carcinoma cell line |

| HSP | Heat shock protein |

| HT-29 | Mouse colon tumor cell line |

| ICG | Indocyanine green |

| ICB | Immune checkpoint blockade |

| iNGR-NP | iNGR-modified PEG-PLGA nanoparticle |

| iNOS | NO synthase enzyme |

| IONP | Iron oxide nanoparticle |

| i.v. | Intravenous injection |

| LyP-1 | Phage-displayed cyclic peptide |

| LLC | Lewis lung carcinoma cell line |

| MCF-7 | Human breast cancer cell line |

| MCT1 | Monocarboxylate transporter 1 |

| MDA-MB-435 | Human breast cancer cell line |

| MDA-MB-231 | Human breast cancer cell line |

| MDR | Multidrug resistance |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| Mg2Si | Magnesium silicide |

| MGP | GOx and MnCO coloaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles |

| MIL-100 | Ferric ions contained metal organic framework |

| MGH | GOx loaded MIL-100 with polydopaminemodified hyaluronic acid coating |

| MMC | Mitomycin C |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| MnO2 | Manganese dioxide |

| M-NS | BSA-directed two-dimensional MnO2 nanosheet |

| MOF | Metal-organic framework |

| MOST | Multispectral optoacoustic tomography |

| MPN | Metal polyphenol network |

| MSN | Mesoporous silica nanoparticle |

| MTX | Methotrexate |

| nano-DOA | Nano-deoxygenation agent |

| NC | Nanocatalyst |

| NIR | Near-infrared |

| NM | Neutrophil membrane |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NP | Nanoparticle |

| NR | Nanoreactor |

| O2 | Oxygen |

| OCl- | Hypochlorite ion |

| OSCC | Oral squamous carcinoma cell line |

| PC-3 | Human prostate cancer cell line |

| Pdot | Polymer dot |

| PDT | Photodynamic therapy |

| PFC | Perfluorocarbon |

| PLA | Poly-L-arginine |

| PLL | poly (L-lysine) |

| PLGA | Polylactic-co-glycolic acid |

| PEG | Poly(ethylene glycol) |

| PEG-b-PHEMA | poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) |

| PLG-g-mPEG | Poly(L-glutamic acid)-g-methoxy poly(ethylene glycol) |

| PPy | Polypyrrole |

| PTT | Photothermal therapy |

| PTX | Paclitaxel |

| PVP | Polyvinyl pyrrolidone |

| PZM | Porous Zr (IV)-based porphyrinic metal-organic framework |

| RA | Retinoic acid |

| RBC | Red blood cell |

| RGD | Arginine-glycine-aspartic acid |

| rMGB | Biomimetic hybrid nanozyme with a GOx/MnO2/BSA-Ce6 core and red blood cell membrane coating |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SCC7 | Murine squamous cell carcinoma cell line |

| SGC7901 | Gastric cancer cell line |

| shVEGF | VEGF-targeted small hairpin RNA |

| SiO2 | Silicon dioxide |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| SMMC 7721 | Human liver tumor cell line |

| SR-B1 | Scavenger receptor type B-1 |

| SW620 | Human Caucasian colon adenocarcinoma cell line |

| TACE | Transarterial chemoembolization |

| TAF | Tumor angiogenesis factor |

| TCPP | Tetrakis (4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin |

| THP | Tumor-homing peptide |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TPZ | Tirapazamine |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| VDA | Vascular disrupting agent |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| U14 | Mouse cervical subcutaneous cancer cell line |

| U87 | Human glioblastoma cell line |

| U87MG | Human glioblastoma cell line |

| Vx2 | Rabbit carcinoma cell line |

| yCDglyTK | Fusion suicide gene |

| ZIF-8 | Zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 |

| αvβ3-Dxtl-PD NP | αvβ3-integrin targeted perfluorocarbon nanoparticle |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the the start-up package at UCLA (to Z.G.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 51773199 to S.Y.) and the start-up fund from Hangzhou Normal University (4095C5021920450 to S.Y.).

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA-Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA-Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selwan EM, Finicle BT, Kim SM, Edinger AL. Attacking the supply wagons to starve cancer cells to death. FEBS Lett. 2016;590:885–907. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu LH, Qi C, Lin J, Huang P. Catalytic chemistry of glucose oxidase in cancer diagnosis and treatment. Chem Soc Rev. 2018;47:6454–72. doi: 10.1039/c7cs00891k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maddocks OD, Berkers CR, Mason SM, Zheng L, Blyth K, Gottlieb E. et al. Serine starvation induces stress and p53-dependent metabolic remodelling in cancer cells. Nature. 2013;493:542–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rafii S, Lyden D, Benezra R, Hattori K, Heissig B. Vascular and haematopoietic stem cells: novel targets for anti-angiogenesis therapy? Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:826–35. doi: 10.1038/nrc925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shojaei F. Anti-angiogenesis therapy in cancer: current challenges and future perspectives. Cancer Lett. 2012;320:130–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tozer GM, Kanthou C, Baguley BC. Disrupting tumour blood vessels. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:423. doi: 10.1038/nrc1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chase DM, Chaplin DJ, Monk BJ. The development and use of vascular targeted therapy in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145:393–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin WH, Yeh SH, Yeh KH, Chen KW, Cheng YW, Su TH. et al. Hypoxia-activated cytotoxic agent tirapazamine enhances hepatic artery ligation-induced killing of liver tumor in HBx transgenic mice. PNAS. 2016;113:11937–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1613466113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang C, Ni D, Liu Y, Yao H, Bu W, Shi J. Magnesium silicide nanoparticles as a deoxygenation agent for cancer starvation therapy. Nat Nanotechnol. 2017;12:378–86. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2016.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feron O. Pyruvate into lactate and back: from the Warburg effect to symbiotic energy fuel exchange in cancer cells. Radiother Oncol. 2009;92:329–33. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang L, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Cao F, Dong K, Ren J. et al. Erythrocyte Membrane Cloaked Metal-Organic Framework Nanoparticle as Biomimetic Nanoreactor for Starvation-Activated Colon Cancer Therapy. ACS Nano. 2018;12:10201–11. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b05200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergers G, Hanahan D. Modes of resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:592–603. doi: 10.1038/nrc2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollebecque A, Massard C, Soria JC. Vascular disrupting agents: a delicate balance between efficacy and side effects. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:305–15. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32835249de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Bock K, Mazzone M, Carmeliet P. Antiangiogenic therapy, hypoxia, and metastasis: risky liaisons, or not? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:393–404. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung BL, Toth MJ, Kamaly N, Sei YJ, Becraft J, Mulder WJ. et al. Nanomedicines for Endothelial Disorders. Nano Today. 2015;10:759–76. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu S, He C, Chen X. Injectable Hydrogels as Unique Platforms for Local Chemotherapeutics-Based Combination Antitumor Therapy. Macromol Biosci. 2018;18:e1800240. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201800240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi J, Kantoff PW, Wooster R, Farokhzad OC. Cancer nanomedicine: progress, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:20–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan W, Yung B, Huang P, Chen X. Nanotechnology for Multimodal Synergistic Cancer Therapy. Chem Rev. 2017;117:13566–638. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu Y, Aimetti AA, Langer R, Gu Z. Bioresponsive materals. Nat Rev Mater. 2016;1:16075–81. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun W, Hu Q, Ji W, Wright G, Gu Z. Leveraging Physiology for Precision Drug Delivery. Physiol Rev. 2016;97:189–225. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sengupta S, Eavarone D, Capila I, Zhao G, Watson N, Kiziltepe T. et al. Temporal targeting of tumour cells and neovasculature with a nanoscale delivery system. Nature. 2005;436:568–72. doi: 10.1038/nature03794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park IK, Tran TH, Oh IH, Kim YJ, Cho KJ, Huh KM. et al. Ternary biomolecular nanoparticles for targeting of cancer cells and anti-angiogenesis. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2010;41:148–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang E, Xing R, Liu S, Li K, Qin Y, Yu H. et al. Vascular targeted chitosan-derived nanoparticles as docetaxel carriers for gastric cancer therapy. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;126:662–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.12.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li S, Jiang Q, Liu S, Zhang Y, Tian Y, Song C. et al. A DNA nanorobot functions as a cancer therapeutic in response to a molecular trigger in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:258. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang S, Tang Z, Hu C, Zhang D, Shen N, Yu H, Selectively Potentiating Hypoxia Levels by Combretastatin A4 Nanomedicine: Toward Highly Enhanced Hypoxia-Activated Prodrug Tirapazamine Therapy for Metastatic Tumors. Adv Mater; 2019. e1805955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu TZ, Zhang DW, Song WT, Tang ZH, Zhu JM, Ma ZM. et al. A poly(L-glutamic acid)-combretastatin A4 conjugate for solid tumor therapy: Markedly improved therapeutic efficiency through its low tissue penetration in solid tumor. Acta Biomater. 2017;53:179–89. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He WY, Zheng X, Zhao Q, Duan LJ, Lv Q, Gao GH. et al. pH-Triggered Charge-Reversal Polyurethane Micelles for Controlled Release of Doxorubicin. Macromol Biosci. 2016;16:925–35. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201500358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang R, Feng L, Dong Z, Wang L, Liang C, Chen J. et al. Glucose & oxygen exhausting liposomes for combined cancer starvation and hypoxia-activated therapy. Biomaterials. 2018;162:123–31. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Son S, Kim N, You DG, Yoon HY, Yhee JY, Kim K. et al. Antitumor therapeutic application of self-assembled RNAi-AuNP nanoconstructs: Combination of VEGF-RNAi and photothermal ablation. Theranostics. 2017;7:9–22. doi: 10.7150/thno.16042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu Z, Zhou P, Pan W, Li N, Tang B. A biomimetic nanoreactor for synergistic chemiexcited photodynamic therapy and starvation therapy against tumor metastasis. Nat commun. 2018;9:5044. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07197-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Y, Lu Y, Abbaraju PL, Azimi I, Lei C, Tang J. et al. Stepwise Degradable Nanocarriers Enabled Cascade Delivery for Synergistic Cancer Therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2018;28:1800706. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prasad P, Shuhendler A, Cai P, Rauth AM, Wu XY. Doxorubicin and mitomycin C co-loaded polymer-lipid hybrid nanoparticles inhibit growth of sensitive and multidrug resistant human mammary tumor xenografts. Cancer Lett. 2013;334:263–73. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jing L, Qu H, Wu D, Zhu C, Yang Y, Jin X. et al. Platelet-camouflaged nanococktail: Simultaneous inhibition of drug-resistant tumor growth and metastasis via a cancer cells and tumor vasculature dual-targeting strategy. Theranostics. 2018;8:2683–95. doi: 10.7150/thno.23654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mukherjee S, Patra CR. Therapeutic application of anti-angiogenic nanomaterials in cancers. Nanoscale. 2016;8:12444–70. doi: 10.1039/c5nr07887c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laakkonen P, Porkka K, Hoffman JA, Ruoslahti E. A tumor-homing peptide with a targeting specificity related to lymphatic vessels. Nat Med. 2002;8:751–5. doi: 10.1038/nm720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen C, Su W, Liu Y, Zhang J, Zuo C, Yao Z. et al. Artificial anaerobic cell dormancy for tumor gaseous microenvironment regulation therapy. Biomaterials. 2019;200:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang S, Damiano MG, Zhang H, Tripathy S, Luthi AJ, Rink JS. et al. Biomimetic, synthetic HDL nanostructures for lymphoma. PNAS. 2013;110:2511–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213657110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Z-X, Liu M-D, Zhang M-K, Wang S-B, Xu L, Li C-X. et al. Interfering with Lactate-Fueled Respiration for Enhanced Photodynamic Tumor Therapy by a Porphyrinic MOF Nanoplatform. Adv Funct Mater. 2018;28:1803498. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li J, Li Y, Wang Y, Ke W, Chen W, Wang W. et al. Polymer Prodrug-Based Nanoreactors Activated by Tumor Acidity for Orchestrated Oxidation/Chemotherapy. Nano Lett. 2017;17:6983–90. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b03531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song W, Tang Z, Zhang D, Li M, Gu J, Chen X. A cooperative polymeric platform for tumor-targeted drug delivery. Chem Sci. 2016;7:728–36. doi: 10.1039/c5sc01698c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Y, Gu H, Zhang DS, Li F, Liu T, Xia W. Highly effective inhibition of lung cancer growth and metastasis by systemic delivery of siRNA via multimodal mesoporous silica-based nanocarrier. Biomaterials. 2014;35:10058–69. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li SY, Cheng H, Xie BR, Qiu WX, Zeng JY, Li CX. et al. Cancer Cell Membrane Camouflaged Cascade Bioreactor for Cancer Targeted Starvation and Photodynamic Therapy. ACS Nano. 2017;11:7006–18. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b02533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]