Abstract

Rationale: The relevance of hormones in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a predominantly male lung disease, is unknown.

Objectives: To determine whether the ER (estrogen receptor) facilitates the development of pulmonary fibrosis and is mediated in part through microRNA regulation of ERα and ERα-activated profibrotic pathways.

Methods: ER expression in male lung tissue and myofibroblasts from control subjects (n = 6) and patients with IPF (n = 6), aging bleomycin (BLM)-treated mice (n = 7), and BLM-treated AF2ERKI mice (n = 7) was determined. MicroRNAs that regulate ER and fibrotic pathways were assessed. Transfections with a reporter plasmid containing the 3′ untranslated region of the gene encoding ERα (ESR1) with and without miRNA let-7 mimics or inhibitors or an estrogen response element–driven reporter construct (ERE) construct were conducted.

Measurements and Main Results: ERα expression increased in IPF lung tissue, myofibroblasts, or BLM mice. In vitro treatment with let-7 mimic transfections in human myofibroblasts reduced ERα expression and associated fibrotic pathways. AF2ERKI mice developed BLM-induced lung fibrosis, suggesting a role for growth factors in stimulating ER and fibrosis. IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1) expression was increased and induced a fourfold increase of an ERE construct.

Conclusions: Our data show 1) a critical role for ER and let-7 in lung fibrosis, and 2) that IGF may stimulate ER in an E2-independent manner. These results underscore the role of sex steroid hormones and their receptors in diseases that demonstrate a sex prevalence, such as IPF.

Keywords: estrogen receptor, pulmonary fibrosis, microRNA let-7

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

The relevance of hormones in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a predominantly male lung disease, is unknown.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Our studies highlight the unexpected role of ER (estrogen receptor) in a male-predominant lung disease.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) remains a fatal and incurable form of interstitial lung disease (1). Although the incidence and prevalence of IPF vary in the literature, epidemiologic studies consistently indicate that the disease occurs predominantly in men (1, 2). In studies in mice, estrogens are protective, whereas androgens exacerbate fibrosis (3). In contrast, female rats develop more severe bleomycin (BLM)-induced interstitial fibrosis than those of male rats that is abrogated by ovariectomy and exacerbated by estrogen replacement (3). A key study showed that the lungs of ERβ (estrogen receptor β) knockout mice accumulated increased collagen compared with wild-type controls (4). In the few published studies in IPF, sex steroid receptor expression remains inconclusive, and data on the role gonadal hormones and their receptors may play in IPF are lacking (5–7).

Genomic analyses of IPF lung biopsies have revealed a unique microRNA (miRNA) transcriptome compared to normal control biopsy samples (8). These and other studies identified a significant change in 10% of miRNAs between control and IPF lungs (9, 10). A recent study reported 47 differentially expressed serum miRNAs in patients with rapidly or slowly progressive IPF compared with control subjects (11). Interestingly, some miRNAs that are changed in IPF (miR-21, let-7a and -7d, and miR-29) have been reported to be regulated by estrogens in breast cancer (12–14). A group of miRNAs that directly or indirectly target ER (estrogen receptor) expression in breast cancer cell lines, such as miR-9-5p (15), and let-7a, -7b, and -7i (13, 16), are also reported to be decreased in IPF (11, 17).

We and others have shown that the ratio of ERα:ERβ is crucial in preventing changes in epithelial cell function (18, 19), rescue of severe preexisting pulmonary hypertension in rats (20), ERα-driven fibroblast activation and fibrosis pathways in hernia development (21), and prevention of cardiac fibrosis in males (22). These publications suggest that activation of ERα may be profibrotic in multiple organs, even in males. Therefore, the aims of the current study were to determine if 1) increased ERα mRNA and protein expression in male IPF lungs and in an aging male BLM mouse model resulted in enhanced ER activity, mediating profibrotic pathways; and 2) altering specific miRNAs found to be decreased in IPF regulate ER expression, and thereby mediate activation of the relevant downstream fibrotic pathways.

Methods

For details, see the online supplement.

Study Approval

All experiments and procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Leonard M. Miller School of Medicine at the University of Miami, a facility accredited by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Isolation and Characterization of Human and Mouse Lung Cells

Human tissues and cells were isolated and propagated from lung tissue removed from male patients with IPF or age-matched males without fibrotic lung disease (control subjects) (Table E1 in the online supplement). Mouse cells were grown and characterized as previously described (23).

Animal Models

Animal use was approved by the University of Miami Animal Care and Use Committee. Male 22-month-old C57BL/6 mice (National Institute of Aging) were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions with food and water ad libitum. AF2ERKI mice were generated as previously described (24).

BLM and Pellet Administration

BLM was administered and mice killed as previously described (25). Placebo, ERα antagonist (MPP, 0.1 mg/pellet), ERβ agonist (O41, 0.1 mg/pellet), or ICI 182,780 (0.1 mg/pellet) was administered to the mice via 21-day time-release pellets (Innovative Research of America) at the time of BLM administration as previously described (26). See the online supplement for further details.

Histological Analysis and Ashcroft Scoring

Lung sections were stained with Masson’s trichrome, and pulmonary fibrosis was measured by semiquantitative Ashcroft scale (27). Scoring was conducted by a pulmonary pathologist in a blinded manner (28).

Hydroxyproline Assay

Lung hydroxyproline assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Hydroxyproline Assay Kit; Sigma-Aldrich).

Real-Time PCR

Amplification and measurement of target RNA was performed on the Step 1 real-time PCR system, as previously described (25).

Western Blot Analysis

ERα, ERβ, AKT (protein kinase B), SMAD2 (mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 2), and phosphorylated AKT and SMAD2 protein expression in lung tissue and myofibroblasts were measured by Western blotting, as previously described (29).

MMP Activity

MMP-2 (matrix metalloproteinase 2) activity was assessed in lung tissue supernatants using a previously described method (23).

Transfection Procedures

Lung cells were plated in basal medium with 20% charcoal/dextran-treated fetal bovine serum (<5 pg/ml estrogens) in 24-well plates.

TGF-β1, phosphorylated SMAD total/SMAD, and IGF-1 ELISAs

Lung tissue was rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline, homogenized in appropriate lysis buffer, and subsequent freeze-thaw cycles were performed to break the cell membrane. After centrifugation, supernatant was removed and assayed according to manufacturer’s directions for IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1) (R&D Systems), TGF-β1 (transforming growth factor β1) (LifeSpan BioSciences Inc.), and phospho-SMAD2 and total SMAD2 (RayBiotech).

Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as mean (±SEM). Overall significance of differences within multiple experimental groups was determined by Kruskal-Wallis test. Comparison of two independent groups was determined by the Mann-Whitney U test. All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.2. Two-tailed P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Increased ER Protein Expression in Lung Tissue and Myofibroblasts of Male Patients with IPF and Lung Tissue from Aging BLM Model Results in Increased ER Transcriptional Activity

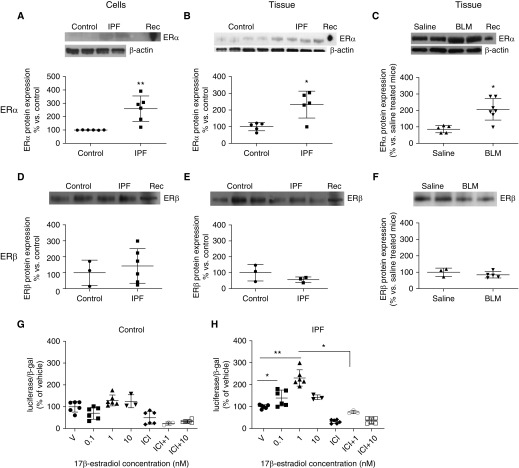

ERα mRNA copy number was increased in lung tissue from male patients with IPF (Table 1) and BLM-treated mice (Table 2) compared with control lungs. We found no difference in ERβ mRNA copy number in human lung (Table 1); instead, ERβ mRNA copy number was decreased in BLM lungs compared with controls. We also examined protein expression in human lung myofibroblasts (Figure 1A) and lung tissue (Figure 1B) from male patients with IPF. There was a 2.5-fold increase in ERα expression in myofibroblasts and lung tissue (Figures 1A and 1B), and no difference in ERβ protein expression in myofibroblasts (Figure 1D) or lung tissue (Figure 1E) compared with control subjects. ERα protein expression increased twofold in the lungs of BLM-treated mice compared with saline controls (Figure 1C). In contrast, ERβ remained unchanged (Figure 1F). Because estrogen sensitivity and responsiveness is in part dependent on the level of functional ERs, IPF myofibroblasts and control fibroblasts were transfected with a luciferase-based reporter gene under the control of four consecutive estrogen-responsive elements (EREs). Control fibroblasts were responsive to E2 (1.2-fold, Figure 1G), although the transcriptional response to E2 was higher in IPF myofibroblasts (2.5-fold, Figure 1H). ICI 182,780, the complete ER antagonist, blocked the response in control and IPF myofibroblasts, proving that E2 effects were ER mediated.

Table 1.

ER mRNA Copy Number of Human IPF and Control Lung Tissue

| Control (n = 5) | IPF (n = 6) | |

|---|---|---|

| ERα copy number | 1.824 ± 0.4* | 12.59 ± 1.1 |

| ERβ copy number | 1,506 ± 16 | 1,466 ± 72 |

Definition of abbreviations: ER = estrogen receptor; IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

P < 0.01 compared with IPF.

Table 2.

ER Copy Number of Lung Tissue Isolated from BLM- and Saline-treated Mice

| Saline | BLM | ERα Antagonist | ERβ Agonist | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERα copy number | 518 ± 102*, n = 16 | 3,160 ± 937, n = 20 | 946 ± 184†, n = 11 | 883 ± 162‡, n = 13 |

| ERβ copy number | 9,110 ± 3,779‡, n = 16 | 1,100 ± 206, n = 11 | 5,914 ± 1,233*, n = 12 | 5,480 ± 1,364‡, n = 10 |

Definition of abbreviations: BLM = bleomycin; ER = estrogen receptor.

Data are shown as mean ± SEM.

P < 0.001 compared with BLM.

P < 0.05 compared with BLM.

P < 0.01 compared with BLM.

Figure 1.

ER (estrogen receptor) protein expression and transcriptional activity were increased in lung myofibroblasts and tissue isolated from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and aging mice with bleomycin (BLM)-induced fibrosis. (A–F) ERα and ERβ protein expression was measured by Western blot analysis in myofibroblasts (A and D) and tissue (B and E) obtained from lungs of male patients with IPF and control lungs and lungs of BLM-treated male mice or saline controls (C and F). ERα expression was increased approximately 2.5-fold in lung tissue (n = 5) or myofibroblasts (n = 6) from patients with IPF and twofold from BLM lungs (n = 5–8). ERβ expression did not change in IPF myofibroblasts, lung tissue, or BLM lungs. Shown are representative Western blots of ER protein expression and β-actin loading control. Data are graphed as the mean ± SEM of tissue or cell lines. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. P values were calculated by Mann-Whitney U test. (G and H) 17β-Estradiol (E2) induced increased transcriptional activation in myofibroblasts isolated from IPF lungs (H) compared with fibroblasts from control lungs (G). Cells were grown in phenol red–free DMEM-F12 supplemented with 20% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 24 hours. After transfection, cells were treated with either vehicle (V) or increasing concentrations (0.1–10 nM) of E2 for 48 hours in phenol red–free medium containing 10% charcoal-stripped FBS. Data are expressed as percentage of vehicle. Shown are means ± SEM of triplicate wells on two representative cell lines; n = 3 unique cell lines/IPF or control cell lines; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01. P values were calculated by Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U test. ICI = ICI 182,780; Rec = recombinant human ERα protein.

Increased ER Expression and Transcriptional Activity Is Modulated by ER-related Pharmacologic Treatment

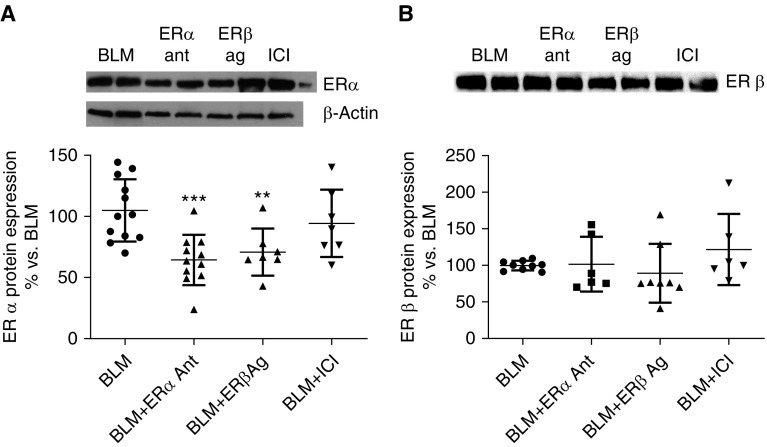

Administration of ER-related pharmacologic agents after BLM injury supported the integral role of ER activation in fibrosis. ERα antagonist (MPP) and ERβ agonist (ERβ 041) decreased expression of ERα protein expression (Figure 2A), whereas the complete ER antagonist (ICI 182,780) did not affect ERα protein expression (Figure 2A). In contrast, ERβ protein expression in mouse lungs was unchanged by administration of an ERα antagonist, ERβ agonist, or ICI compared with BLM treatment (Figure 2B), despite changes in mRNA copy number.

Figure 2.

ER (estrogen receptor) protein expression was regulated in mouse lung tissue by pharmacologic ER antagonists and agonists. (A and B) ERα (A) and ERβ (B) protein expression was measured by Western analysis in mouse lung tissue. Mice were exposed to bleomycin (BLM) and received ERα antagonist (Ant) or ERβ agonist (Ag) or ICI 182,780 (ICI) pellets subcutaneously 24 hours later. Lungs were harvested at 21 days after BLM administration. Data are graphed as the mean ± SEM of tissue and are expressed as percentage of BLM treatment. Shown are representative Western blots and β-actin loading control. For ERβ expression protein, immunoprecipitation was used as described in the Methods. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 compared with BLM treatment. P values were calculated by Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U test. n = 6–14 mice/treatment group.

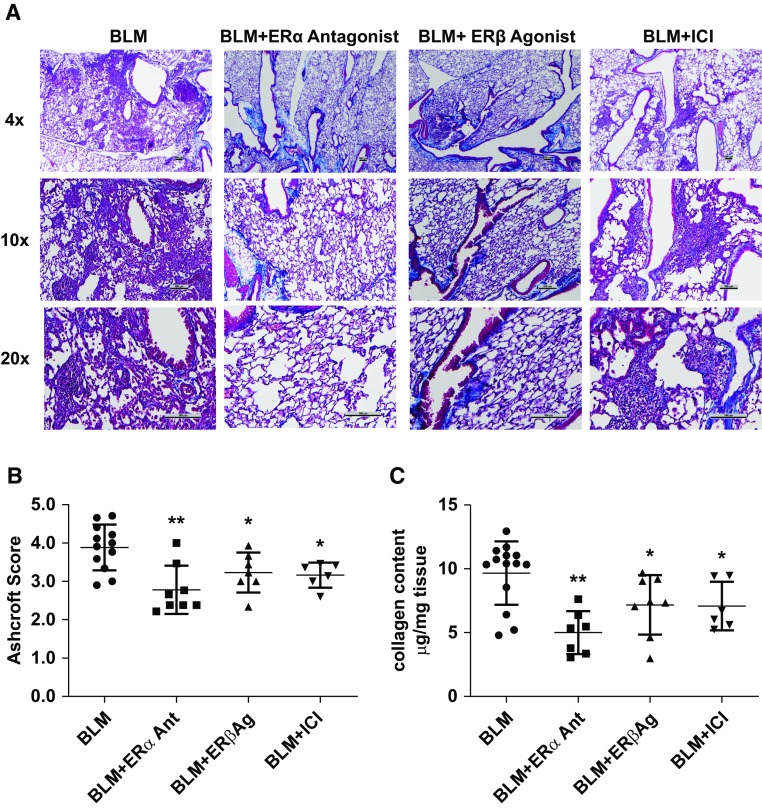

Inhibition of ER Expression by ER-related Pharmacologic Treatments Reduces BLM-induced Pulmonary Fibrosis

Because we found that ER antagonists/agonists could alter ER protein expression, we determined whether the observed changes in ER expression after treatment correlated with protection against fibrosis. Histology (Figure 3A) and lung fibrosis endpoints (Figures 3B and 3C) were examined 21 days after BLM administration in the lungs of all treated groups.

Figure 3.

ER (estrogen receptor) pharmacologic treatments reduced bleomycin (BLM)-induced pulmonary fibrosis in aging male C57/Bl6 mice. (A–C) Histology (A), Ashcroft score (B), and collagen content (C) were assessed. (A) Representative photomicrographs of the lungs of 22-month-old male C57BL/6 mice infused with BLM (n = 12), BLM + ERα antagonist (Ant, n = 8), BLM + ERβ agonist (Ag, n = 7), or BLM + complete ER antagonist ICI 182,780 (ICI, n = 6). Trichrome-stained images at 4×, 10×, and 20× original magnification are shown. Scale bars, 100 µm. (B) Histologic examination of Masson’s trichrome–stained lung tissue was carried out as described in the Methods. Ashcroft scores were used to evaluate the degree of fibrosis. Data are graphed as the mean score of 32 fields/section of lung. (C) Collagen content was estimated by hydroxyproline assay, as described in the Methods. Data are graphed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with BLM treatment alone. P values were calculated by Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U test.

In vivo pharmacologic inhibition of ERα by administration of 21 days of sustained-release pellets of an ERα antagonist resulted in prevention of BLM-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Figure 3A shows representative histologic sections of mouse lungs, demonstrating increased alveolar wall thickening and interstitial collagen deposition in BLM-treated mice that was partially prevented by ERα antagonist administration. Ashcroft score (Figure 3B) in the ERα antagonist group was decreased compared with BLM controls. Lung collagen content (Figure 3C), αv-integrin, and TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor α) mRNA expression (Table 3) were also decreased in the ERα antagonist–treated group compared with BLM controls. Administration of pellets containing ERβ agonist resulted in a decrease in Ashcroft and collagen content (Figure 3C) and demonstrated decreased expression of αv-integrin and TNF-α mRNA expression (Table 3), suggesting that the activation of ERβ could prevent fibrosis. Treatment with a complete antiestrogen (ICI 182,780) was less effective in preventing the progression of pulmonary fibrosis after BLM administration (Figure 3), as both ERα and ERβ were blocked.

Table 3.

mRNA Expression of Fibrotic Markers

| mRNA/18s | BLM (n = 13) | ERα Antagonist (n = 7) | ERβ Agonist (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| αV integrin | 16.89 ± 1.7 | 5.8 ± 1.3* | 8.9 ± 2.2† |

| TNF-α | 3.09 ± 0.9 | 0.16 ± 0.07† | 0.16 ± 0.05† |

Definition of abbreviations: BLM = bleomycin; ER = estrogen receptor.

P < 0.001 compared with BLM for integrin.

P < 0.05 compared with BLM for integrin.

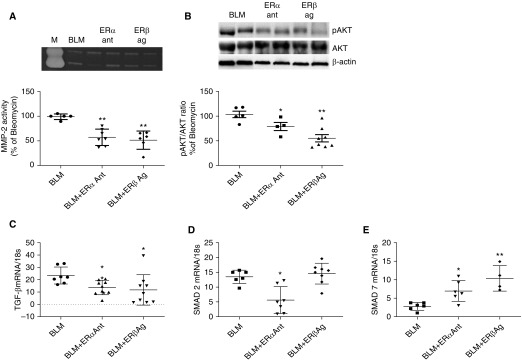

Modulation of ER Expression Regulates Other Fibrotic Pathways, TGF-β Protein Expression, MMP-2 Activity, AKT Activation, and SMAD2 Phosphorylation

Several pathways associated with fibrosis, including MMPs, AKT, and TGF-β, are mediated by ER activation (30–33). We therefore reasoned that it was possible that altering ERα expression would affect these pathways. As described for collagen content, ERα antagonist and ERβ agonists decreased MMP-2 activity (Figure 4A), AKT phosphorylation (Figure 4B), and TGF-β mRNA expression (Figure 4C). SMAD2 and SMAD7 mRNA expression were also regulated such that SMAD2 mRNA expression (Figure 4D) was lowered by ERα treatment, and SMAD7 (a negative regulator of TGF-β signaling pathways) was increased by all treatments (Figure 4E). ER subtype antagonist and agonist data provided pharmacologic evidence that modulation of ER expression regulated fibrotic pathways and downstream signaling. As expected, ICI 182,780 was not effective, because it blocked ERα and ERβ in our system (data not shown). TGF-β protein expression was decreased by ERα antagonist (96 ± 39 pg/ml, n = 4) and ERβ agonist (62 ± 32 pg/ml, n = 5) treatment compared with BLM placebo–treated mice (218 ± 17 pg/ml, n = 5). ICI had no effect (157 ± 41, n = 4). Because sustained SMAD2 phosphorylation has been noted to contribute to TGF-β–induced myofibroblast differentiation (34), we also performed Western analysis and semiquantitative ELISA for total SMAD/SMAD2. Our data revealed that SMAD2 phosphorylation was dampened by ERα pharmacologic treatment (62% of control), but not by ERβ agonist treatment (95% of control) similar to mRNA expression.

Figure 4.

Activation of fibrotic pathways is mediated by ER (estrogen receptor) antagonist/agonists in bleomycin (BLM)-induced fibrotic lungs. (A) Zymography was performed on lung tissue protein extracts from aged male C57BL/6 mice receiving BLM, ERα antagonist (Ant), or ERβ agonist (Ag) to measure MMP-2 activity. Inset is a representative zymogram. Data are graphed as the mean ± SEM of n = 5–6/group. (B) Western blots were performed on lung tissue protein extracts from aged male C57BL/6 mice receiving BLM, ERα antagonist, or ERβ agonist to measure AKT phosphorylation. A representative Western blot is shown of two individual mice per group. Data are graphed as the mean ± SEM of n = 5–8/group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with BLM treatment alone. P values were calculated by Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests; all treatments compared with BLM. (C–E) TGF-β (C), SMAD2 (D), and SMAD7 (E) mRNA expression was measured in lungs from aged male C57BL/6 mice receiving BLM, ERα antagonist, or ERβ agonist. Data are graphed normalized for 18S content. n = 5–8/group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with BLM treatment alone. P values were calculated by Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests; all treatments were compared with BLM. M = zymography control.

miRNA Expression Is Altered in IPF and BLM-induced Pulmonary Fibrosis in Aging Mice

Based on our data showing a change in ER and prevention of fibrosis after pharmacologic treatment, we investigated miRNAs that regulate ER as a potential mechanism. We performed real-time PCR on lung tissue isolated from male patients with IPF or controls and aging mice receiving either BLM or BLM + ER antagonists or agonists and assayed for miR let-7b, 7i, 92, 221/222, 26, and 206 (Table E2), miRNAs known to regulate ER expression (14). We found that let-7a and -7d were lower in human lung tissue from patients with IPF compared with normal tissue, data similar to previous reports (Table 4). In addition, expression of let-7a and -7d was decreased in the lungs of BLM-treated mice compared with saline-treated mice. Importantly, in vivo pharmacologic treatment of mice with ER antagonists/agonists increased let-7a and -7d (Table 4). There was no difference in baseline expression between IPF and control lungs of other miRNAs that regulated ER expression. We found that miR-26a, another regulator of ERα expression, was modulated by ERα agonist and ERβ antagonist treatment (Table E2).

Table 4.

MicroRNA Expression in Lung Tissue

| miR/U6 | Control (n = 3–4) | IPF (n = 3–4) | Saline (n = 6–8) | BLM (n = 14) | ERα Antagonist (n = 10) | ERβ Agonist (n = 9–11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| let-7a | 1.82 ± 0.46* | 0.49 ± 0.15 | 0.41 ± 0.09† | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 0.70 ± 0.13‡ | 0.69 ± 0.10‡ |

| let-7d | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.02 ± 0.05 | 0.35 ± 0.07‡ | 0.035 ± 0.009 | 0.27 ± 0.24‡ | 0.39 ± 0.10‡ |

Definition of abbreviations: BLM = bleomycin; ER = estrogen receptor; IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

P < 0.05 compared with IPF.

P < 0.01 compared with BLM.

P < 0.0001 compared with BLM.

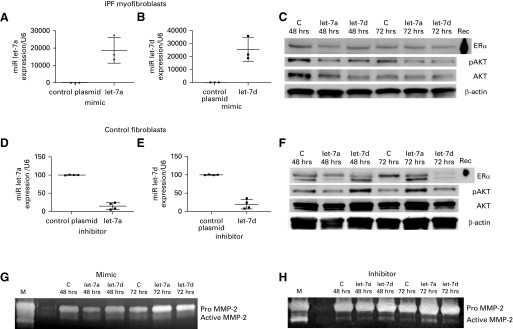

let-7a and -7d Directly Regulate Expression of ERα Protein Expression

We transfected myofibroblasts from male patients with IPF with a mimic of let-7a (Figure 5A, >18,000% of control plasmid), let-7d (Figure 5B, >25,000% of control plasmid), or inhibitor let-7a (Figure 5D, <20% of control plasmid) or let-7d (Figure 5E, <25% of control plasmid) in control lung fibroblasts. After transfection with mimics, myofibroblasts had reduced ERα protein expression at 48 and 72 hours (Figure 5C, upper panel, n = 3 unique myofibroblast cell lines). In contrast, 48 hours after transfection with let-7d inhibitors and 72 hours after transfection with let-7a, control fibroblasts expressed increased ERα protein (Figure 5F, n = 3 unique fibroblasts). To provide further evidence that let-7a or -7d were regulating ERα expression, we performed experiments using the 3′- UTR (untranslated region) of the ESR1 gene containing the miRNA response element of let-7. Baseline luciferase expression was at least twofold higher in IPF myofibroblasts compared with control fibroblasts (n = 2 unique cell lines of each). Transfection of control fibroblasts with an inhibitory plasmid in tandem with the 3′UTR increased luciferase reporter activity by approximately 200% for let-7a and 300% for let-7d. In contrast, transfection with a mimic plasmid increased ERα expression and decreased luciferase activity when transfected into IPF myofibroblasts (n = 3 individual patient cells).

Figure 5.

(A–F) ER (estrogen receptor) expression was inversely regulated by let-7a and let-7d manipulation in myofibroblasts from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) lungs (A–C) or control fibroblasts (D–F). (A–E) MicroRNA expression determined by PCR, as described in the Methods, was performed on myofibroblasts transfected with plasmids containing mimic or mutated control plasmids (A and B) or control fibroblasts transfected with inhibitor (D and E). Data are expressed as percent of control scrambled plasmids. Each point represents independent transfections of n = 3–4 (control fibroblasts) or n = 4 (IPF myofibroblasts). Graphs illustrate transfection efficacy of individual cell lines. Inserts are representative Western blots of two individual cell lines. (C and F) A time course of ERα, pAKT, AKT protein expression, and β-actin loading controls for mimics (C) and inhibitors (F) are shown. (G and H) Zymography was performed on cell lysates after transfection of mimic (G) or inhibitor (H) of let-7a or -7d to measure MMP-2 activity. A representative zymogram of each is shown (n = 3 unique cell lines). C = control scrambled plasmids; M = zymography control; Rec = recombinant.

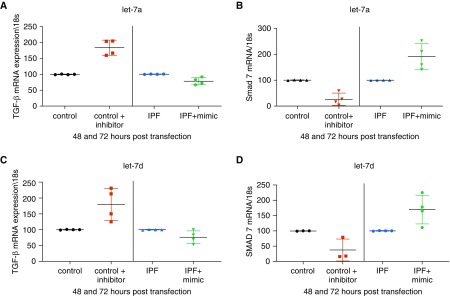

Manipulation of let-7a or -7d Modulates MMP-2 Activity, AKT Phosphorylation, and TGF-β and SMAD7 Expression

We determined the downstream effects of ER manipulation after let-7a and -7d mimics (Figure 5C) or inhibitors (Figure 5F). Inhibition of let -7a and -7d increased AKT activation between 130% and 215% (Figure 5C). After transfection with a let-7a or -7d mimic, AKT activation decreased approximately 45% at 72 hours (Figure 5C). Active MMP-2 (lower band) decreased at 48 hours after transfection of let-7a and let-7d mimic (Figure 5G). Active MMP-2 increased at 48 and 72 hours after let 7a and -7d inhibition, respectively (Figure 5H).

Because ER regulation of TGF-β has been shown in multiple organs, and SMADs regulate let-7, we investigated whether transfection of mimics or inhibitors modulated this fibrotic pathway. We did not test for significance due to a small number of unique patient cell lines; however, we found that inhibition of let-7 increased TGF-β mRNA up to over 175% and decreased SMAD7 mRNA at least 50% (Figure 6) in every cell line tested. As noted in the literature, mimics were less effective (35) in reducing TGF-β mRNA expression (∼30% decrease) but increased inhibitory SMAD7 mRNA more than 150%.

Figure 6.

(A–D) Regulation of the TGF-β pathway was suggested after let-7a and -7d manipulation. Transfection with mimic let-7a or -7d in myofibroblasts from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) lungs or let-7a or -7d inhibitor in fibroblasts from controls regulates TGF-β (A and C) and SMAD pathway changes (B and D). Red symbols represent control human fibroblasts after transfection with let-7 inhibitors (n = 3–4); green symbols represent IPF myofibroblasts after transfection with let-7 mimic plasmids (n = 4); and black and blue symbols represent cells transfected with mutated control plasmids. Data are graphed as mean ± SEM of independent transfections.

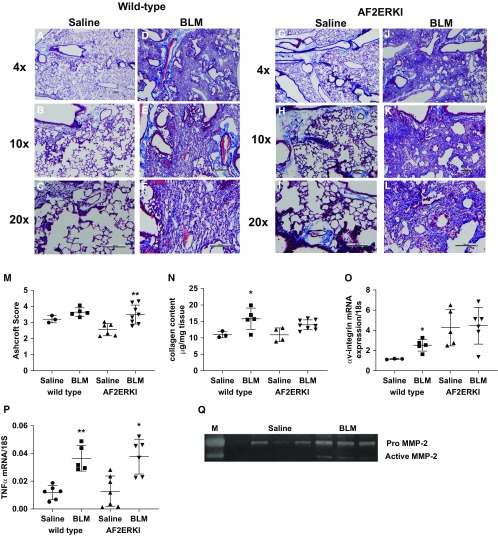

BLM Induces Fibrosis in AF2ERKI Mice

To determine in vivo if ERα activation in IPF lungs is E2 dependent, we induced fibrosis in mice with a mutation in the AF2, estrogen ligand–binding domain (24). We found that, even in the absence of the functional AF2 domain, the mice developed BLM-induced fibrosis, as determined by Ashcroft scores and other established fibrotic markers (Figures 7A–7H). These data suggest a role for alternative ligands mediating ER activation and fibrotic consequences. BLM treatment resulted in increased ERα protein expression (data not shown) and MMP-2 activation (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Estrogen-independent activation of the ER (estrogen receptor) may play a role in fibrosis. C57/BL6 mice (3 mo old) that harbor a mutation in the AF2 domain of the ER (AF2ERKI) and their wild-type littermate controls were administered saline or bleomycin (BLM), as described in the Methods. Mice were killed at 21 days after treatment and lungs collected for histology. Representative trichrome sections from a single mouse per group (n = 3–5 mice/group). (A–N) Saline- and BLM-treated wild-type littermates (A–F) or AF2ERKI mouse lungs (G–L) were analyzed for severity of fibrosis by Ashcroft scores (M); collagen content was estimated by hydroxyproline assay, as described in the Methods (N). (O and P) mRNA expression of fibrotic markers αV-integrin (O) and TNF-α (P) was assessed. Data are graphed as the mean ± SEM of n = 3–8/group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 saline compared with BLM of same mouse group. P values were calculated by Mann-Whitney U test. (Q) Zymography was performed on lung lysates from homozygous mice treated with either saline or BLM. MMP-2 activity was markedly increased after BLM-induced fibrosis (n = 3 mice/group). Scale bars, 100 µm. M = positive control for MMP.

Increased IGF-1 in IPF Lung and BLM-Fibrotic Lungs Can Bind to ER

Because the amount of circulating estrogens in males may not be enough to stimulate ER activation, we investigated growth factors, such as IGF-1, known to stimulate the ER-mediating downstream events in an estrogen-independent manner (36, 37). IGF-1 mRNA increased in myofibroblasts isolated from IPF lungs compared with control fibroblasts (38, 39). In our studies, IGF-1 levels were higher in IPF myofibroblasts compared with control fibroblasts (0.17 ± 0.03 ng/ml, n = 4 vs. 0.05 ± 0.009, n = 7). IGF-1 was also increased in lungs isolated from BLM-treated mice compared with saline-treated mice (0.99 ± 0.16 ng/ml vs. 0.33 ± 0.038). Finally, we performed additional transfection studies to determine if IGF-1 increased transcriptional activity of the ER. IGF-1 stimulated transcriptional activation of an ERE up to fourfold over vehicle compared with E2 in myofibroblasts isolated from IPF lungs (Figure E1), whereas control fibroblast transcriptional activity was not stimulated by IGF-1 treatment. This response was blocked in the presence of ICI 182,780, thus suggesting an E2 ligand–independent ER-mediated response (36).

Discussion

Our study highlights the importance of ERα activation in mediating male-predominant lung fibrosis, and it reveals key miRNAs essential for ERα regulation. We show parallel increases using Western blotting and PCR in ERα expression in lung tissue from male patients with IPF compared with lungs analogous to the increase in ERα expression in aging BLM-induced fibrotic lungs compared with saline control lungs. The increased expression of ERα protein was accompanied by increased transcriptional activation in myofibroblasts from IPF lung and BLM mouse lungs compared with fibroblasts from control lungs and lungs from saline control mice, respectively. A recent study reported the lack of positive ER expression in IPF tissue using immunohistochemistry (IHC) (6). This result is in contrast to our reported results using Western blotting and PCR. The difficulties with IHC detection of ER are well recognized due to a lack of standardized IHC assays and a high false-negative rate in nonreproductive organs, such as the lung (40).

There is ongoing interest concerning the influence of sex on the development of IPF due to the male prevalence of the disease. For this study, we chose to study ER, because a change in change in ratio of ERα:ERβ has been reported in cardiac and muscle fibrosis in males (22, 41–44). ERs are known to be involved in normal lung development, physiology, and in several lung diseases, including interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, airway hyperreactivity, and acute lung injury in males and females. A single study, limited by small sample size and incomplete classification of IPF disease severity, reported higher levels in the ESR1 gene in lung tissue from patients with IPF compared with lung tissue from patients with COPD (7). A more recent study showed a decreased expression of ESR1 gene and ER protein in lung tissue isolated from patients with IPF at the time of transplant and in SV-40–transformed bronchial epithelial cells (5). The difference between these two studies may lie in the use of “end-stage” IPF lung tissue and the use of an SV-40–transformed cell line. Our data from lung biopsies from patients with IPF show an increase in ER expression in isolated myofibroblasts and total lung tissue.

In the aging mouse model, there is a correlation between increased ERα expression and fibrotic markers/endpoints (Ashcroft score, collagen content, and αV-integrin and TNF expression). We therefore investigated the effect of regulation of ER expression and downstream mediated effects (TGF-β pathway, MMP-2 activity, and AKT activation). The importance of the regulation of ERα was underscored by our in vivo pharmacologic manipulations. We administered 21-day release pellets of an ERα antagonist, an ERβ agonist, or the complete receptor antagonist, ICI 182,780. Based on our pharmacologic results, we demonstrated clearly that a decrease of ERα reduces the fibrosis in the lungs of aging male mice with a reduction in fibrotic pathways.

After confirming the pharmacologic regulation of ER expression, we investigated the possible mechanism(s). We analyzed miRNAs that have been shown to regulate ER expression, including miRs 221/222, 9, 193, and 18 and the let-7 family (14). We focused on the miR let-7 family due to the aberrant regulation in IPF tissue (17, 45), IPF serum (11), and breast cancer cells (46). We confirmed the downregulation of let-7a and -7d in tissues and myofibroblasts from IPF lungs compared with fibroblasts isolated from control lungs. We also found that let-7a and -7d were decreased in lungs from BLM mice and increased after treatment with ERα antagonist or ERβ agonist. We validated our results in vitro using let-7 mimics or inhibitors in combination with the ESR1 3′UTR containing the miR response element of let-7, and we confirmed ERα as a direct target of miR let-7a/7d.

Changes in miRNAs have been implicated in gene expression associated with the development of IPF (11, 17, 47). Upregulation of profibrotic miRNAs and downregulation of antifibrotic miRNAs contribute to the proliferation of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, leading to the aberrant response to epithelial injury and ECM collagen deposition (11, 17, 39). These alterations in miRNAs alter fibrotic-inducing expression of TGF-β, AKT, and MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase), pathways also modulated by ER activation (48, 49). In fact, we noted that a trend of pathway modulation after ERα change was achieved, and this appeared to be linked in part to regulation of let-7a/7d and subsequent ER regulation (by pharmacologic modulation with let-7 mimic). Thus, we provide mechanistic evidence that modulating ER in a preclinical model of pulmonary fibrosis may be, in part, performed via gene expression regulation by miRNAs that effect changes through multiple pathways. Availablility of new unique cell lines will allow future experiments to test manipulation of let-7 and subsequent in-depth pathway changes.

Although estrogens and the ERs have been shown to play a role in male physiology and disease (50–52), the question remains as to whether the ERα increase is relevant and participates in the pathogenesis of IPF. We acknowledge that the amount of circulating E2 in aging males (10–40 pg/ml) may not be sufficient to stimulate ER-mediated fibrotic effects. We measured estradiol levels in IPF and age-matched control patients and were unable to find differences (data not shown). Multiple levels of interaction or cross-talk between ER and growth factor and tyrosine kinase pathways have been noted to contribute to ER actions (53). We therefore used AF2ERKI mice to test whether E2-independent ligand binding to the ER by growth factors, such as IGF-1 or PDGF (platelet-derived growth factor), could be involved. AF2ERKI mice that received BLM were susceptible to lung fibrosis even in the absence of a functional AF-2 (E2 ligand binding domain), suggesting that alternative E2-mediated transactivation of the ER could be mediating the development of fibrosis. We found that ER-dependent IGF-1 stimulation is in part responsible for transactivation of the ERE in IPF and BLM myofibroblasts. We also confirmed upregulation of IGF-1 in IPF versus control and BLM versus saline lungs, but we cannot rule out that other growth factors could be involved (54, 55).

Thus, in this study, we investigated the relationship between ERs, and selected miRNAs known to be changed in IPF and associated with regulation of ER in decreasing pulmonary fibrosis in an aging male BLM mouse model. Our studies highlight the unexpected role of ER in a male-predominant lung disease.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported, in part, by the Lester and Sue Smith Foundation, The Samrick Foundation, and the NIH (National Institute of Aging grants R01 AG017170 [S.E.] and R21 AGAG060338 [S.E. and M.K.G.] and General Medical Sciences grant R01GM113256 [K.B.]).

Author Contributions: S.E. designed the research studies, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript; G.R. conducted experiments and analyzed data; S.P.-S., X.X., P.C., and J.S. conducted experiments and acquired and analyzed data; S.S. and F.E.S. performed analysis of lungs obtained from in vivo experiments; K.B. and K.S.K. provided scientific input and edited the manuscript; and M.K.G. designed the research studies, analyzed data, and wrote and edited the manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201903-0508OC on July 10, 2019

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Raghu G, Chen SY, Hou Q, Yeh WS, Collard HR. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US adults 18–64 years old. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:179–186. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01653-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sathish V, Martin YN, Prakash YS. Sex steroid signaling: implications for lung diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;150:94–108. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voltz JW, Card JW, Carey MA, Degraff LM, Ferguson CD, Flake GP, et al. Male sex hormones exacerbate lung function impairment after bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:45–52. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0340OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morani A, Barros RP, Imamov O, Hultenby K, Arner A, Warner M, et al. Lung dysfunction causes systemic hypoxia in estrogen receptor beta knockout (ERbeta−/−) mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7165–7169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602194103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith LC, Moreno S, Robertson L, Robinson S, Gant K, Bryant AJ, et al. Transforming growth factor beta1 targets estrogen receptor signaling in bronchial epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2018;19:160. doi: 10.1186/s12931-018-0861-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehrad M, Trejo Bittar HE, Yousem SA. Sex steroid receptor expression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Hum Pathol. 2017;66:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGee SP, Zhang H, Karmaus W, Sabo-Attwood T. Influence of sex and disease severity on gene expression profiles in individuals with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2014;5:71–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vukmirovic M, Kaminski N. Impact of transcriptomics on our understanding of pulmonary fibrosis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2018;5:87. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milosevic J, Pandit K, Magister M, Rabinovich E, Ellwanger DC, Yu G, et al. Profibrotic role of miR-154 in pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;47:879–887. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0377OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandit KV, Milosevic J, Kaminski N. MicroRNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Transl Res. 2011;157:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang G, Yang L, Wang W, Wang J, Wang J, Xu Z. Discovery and validation of extracellular/circulating microRNAs during idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis disease progression. Gene. 2015;562:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhat-Nakshatri P, Wang G, Collins NR, Thomson MJ, Geistlinger TR, Carroll JS, et al. Estradiol-regulated microRNAs control estradiol response in breast cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4850–4861. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fletcher CE, Dart DA, Bevan CL. Interplay between steroid signalling and microRNAs: implications for hormone-dependent cancers. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:R409–R429. doi: 10.1530/ERC-14-0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klinge CM. miRNAs regulated by estrogens, tamoxifen, and endocrine disruptors and their downstream gene targets. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;418:273–297. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pillai MM, Gillen AE, Yamamoto TM, Kline E, Brown J, Flory K, et al. HITS-CLIP reveals key regulators of nuclear receptor signaling in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;146:85–97. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3004-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao Y, Deng C, Lu W, Xiao J, Ma D, Guo M, et al. let-7 microRNAs induce tamoxifen sensitivity by downregulation of estrogen receptor α signaling in breast cancer. Mol Med. 2011;17:1233–1241. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pandit KV, Milosevic J. MicroRNA regulatory networks in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Biochem Cell Biol. 2015;93:129–137. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2014-0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Catanuto P, Doublier S, Lupia E, Fornoni A, Berho M, Karl M, et al. 17 beta-estradiol and tamoxifen upregulate estrogen receptor beta expression and control podocyte signaling pathways in a model of type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int. 2009;75:1194–1201. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elliot SJ, Catanuto P, Espinosa-Heidmann DG, Fernandez P, Hernandez E, Saloupis P, et al. Estrogen receptor beta protects against in vivo injury in RPE cells. Exp Eye Res. 2010;90:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Umar S, Iorga A, Matori H, Nadadur RD, Li J, Maltese F, et al. Estrogen rescues preexisting severe pulmonary hypertension in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:715–723. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201101-0078OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao H, Zhou L, Li L, Coon V J, Chatterton RT, Brooks DC, et al. Shift from androgen to estrogen action causes abdominal muscle fibrosis, atrophy, and inguinal hernia in a transgenic male mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E10427–E10436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1807765115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedram A, Razandi M, O’Mahony F, Lubahn D, Levin ER. Estrogen receptor-beta prevents cardiac fibrosis. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:2152–2165. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glassberg MK, Choi R, Manzoli V, Shahzeidi S, Rauschkolb P, Voswinckel R, et al. 17β-estradiol replacement reverses age-related lung disease in estrogen-deficient C57BL/6J mice. Endocrinology. 2014;155:441–448. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arao Y, Hamilton KJ, Ray MK, Scott G, Mishina Y, Korach KS. Estrogen receptor α AF-2 mutation results in antagonist reversal and reveals tissue selective function of estrogen receptor modulators. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14986–14991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109180108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tashiro J, Elliot SJ, Gerth DJ, Xia X, Pereira-Simon S, Choi R, et al. Therapeutic benefits of young, but not old, adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in a chronic mouse model of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Transl Res. 2015;166:554–567. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glassberg MK, Catanuto P, Shahzeidi S, Aliniazee M, Lilo S, Rubio GA, et al. Estrogen deficiency promotes cigarette smoke–induced changes in the extracellular matrix in the lungs of aging female mice. Transl Res. 2016;178:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2016.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashcroft T, Simpson JM, Timbrell V. Simple method of estimating severity of pulmonary fibrosis on a numerical scale. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41:467–470. doi: 10.1136/jcp.41.4.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shahzeidi S, Mulier B, de Crombrugghe B, Jeffery PK, McAnulty RJ, Laurent GJ. Enhanced type III collagen gene expression during bleomycin induced lung fibrosis. Thorax. 1993;48:622–628. doi: 10.1136/thx.48.6.622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glassberg MK, Elliot SJ, Fritz J, Catanuto P, Potier M, Donahue R, et al. Activation of the estrogen receptor contributes to the progression of pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis via matrix metalloproteinase–induced cell invasiveness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1625–1633. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russo RC, Garcia CC, Barcelos LS, Rachid MA, Guabiraba R, Roffê E, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ plays a critical role in bleomycin-induced pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89:269–282. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0610346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park S, Ahn JY, Lim MJ, Kim MH, Yun YS, Jeong G, et al. Sustained expression of NADPH oxidase 4 by p38 MAPK-Akt signaling potentiates radiation-induced differentiation of lung fibroblasts. J Mol Med (Berl) 2010;88:807–816. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richter K, Kietzmann T. Reactive oxygen species and fibrosis: further evidence of a significant liaison. Cell Tissue Res. 2016;365:591–605. doi: 10.1007/s00441-016-2445-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craig VJ, Zhang L, Hagood JS, Owen CA. Matrix metalloproteinases as therapeutic targets for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;53:585–600. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0020TR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ard S, Reed EB, Smolyaninova LV, Orlov SN, Mutlu GM, Guzy RD, et al. Sustained Smad2 phosphorylation is required for myofibroblast transformation in response to TGF-β. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2019;60:367–369. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2018-0252LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Selbach M, Schwanhäusser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, Rajewsky N. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature. 2008;455:58–63. doi: 10.1038/nature07228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klotz DM, Hewitt SC, Ciana P, Raviscioni M, Lindzey JK, Foley J, et al. Requirement of estrogen receptor-alpha in insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)–induced uterine responses and in vivo evidence for IGF-1/estrogen receptor cross-talk. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8531–8537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109592200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ignar-Trowbridge DM, Pimentel M, Parker MG, McLachlan JA, Korach KS. Peptide growth factor cross-talk with the estrogen receptor requires the A/B domain and occurs independently of protein kinase C or estradiol. Endocrinology. 1996;137:1735–1744. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.5.8612509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu G, Friggeri A, Yang Y, Milosevic J, Ding Q, Thannickal VJ, et al. miR-21 mediates fibrogenic activation of pulmonary fibroblasts and lung fibrosis. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1589–1597. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montgomery RL, Yu G, Latimer PA, Stack C, Robinson K, Dalby CM, et al. MicroRNA mimicry blocks pulmonary fibrosis. EMBO Mol Med. 2014;6:1347–1356. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201303604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anagnostou VK, Welsh AW, Giltnane JM, Siddiqui S, Liceaga C, Gustavson M, et al. Analytic variability in immunohistochemistry biomarker studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:982–991. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pedram A, Razandi M, Narayanan R, Levin ER. Estrogen receptor beta signals to inhibition of cardiac fibrosis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016;434:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pelzer T, Loza PA, Hu K, Bayer B, Dienesch C, Calvillo L, et al. Increased mortality and aggravation of heart failure in estrogen receptor-beta knockout mice after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2005;111:1492–1498. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000159262.18512.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang M, Crisostomo PR, Markel T, Wang Y, Lillemoe KD, Meldrum DR. Estrogen receptor beta mediates acute myocardial protection following ischemia. Surgery. 2008;144:233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu Y, Bian Z, Lu P, Karas RH, Bao L, Cox D, et al. Abnormal vascular function and hypertension in mice deficient in estrogen receptor beta. Science. 2002;295:505–508. doi: 10.1126/science.1065250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pandit KV, Corcoran D, Yousef H, Yarlagadda M, Tzouvelekis A, Gibson KF, et al. Inhibition and role of let-7d in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:220–229. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200911-1698OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun X, Qin S, Fan C, Xu C, Du N, Ren H. Let-7: a regulator of the ERα signaling pathway in human breast tumors and breast cancer stem cells. Oncol Rep. 2013;29:2079–2087. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lino Cardenas CL, Kaminski N, Kass DJ. Micromanaging microRNAs: using murine models to study microRNAs in lung fibrosis. Drug Discov Today Dis Models. 2013;10:e145–e151. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmod.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsuda T, Yamamoto T, Muraguchi A, Saatcioglu F. Cross-talk between transforming growth factor-β and estrogen receptor signaling through Smad3. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:42908–42914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105316200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yaşar P, Ayaz G, User SD, Güpür G, Muyan M. Molecular mechanism of estrogen-estrogen receptor signaling. Reprod Med Biol. 2016;16:4–20. doi: 10.1002/rmb2.12006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schulster M, Bernie AM, Ramasamy R. The role of estradiol in male reproductive function. Asian J Androl. 2016;18:435–440. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.173932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blattner MS, Mahoney MM. Changes in estrogen receptor signaling alters the timekeeping system in male mice. Behav Brain Res. 2015;294:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Couse JF, Korach KS. Estrogen receptor null mice: what have we learned and where will they lead us? Endocr Rev. 1999;20:358–417. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lange CA. Making sense of cross-talk between steroid hormone receptors and intracellular signaling pathways: who will have the last word? Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:269–278. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maeda A, Hiyama K, Yamakido H, Ishioka S, Yamakido M. Increased expression of platelet-derived growth factor A and insulin-like growth factor-I in BAL cells during the development of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Chest. 1996;109:780–786. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.3.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Choi JE, Lee SS, Sunde DA, Huizar I, Haugk KL, Thannickal VJ, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor blockade improves outcome in mouse model of lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:212–219. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-228OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.