Abstract

Background

Chemotherapy-induced damage of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPC) causes multi-lineage myelosuppression. Trilaciclib is an intravenous CDK4/6 inhibitor in development to proactively preserve HSPC and immune system function during chemotherapy (myelopreservation). Preclinically, trilaciclib transiently maintains HSPC in G1 arrest and protects them from chemotherapy damage, leading to faster hematopoietic recovery and enhanced antitumor immunity.

Patients and methods

This was a phase Ib (open-label, dose-finding) and phase II (randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled) study of the safety, efficacy and PK of trilaciclib in combination with etoposide/carboplatin (E/P) therapy for treatment-naive extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer patients. Patients received trilaciclib or placebo before E/P on days 1–3 of each cycle. Select end points were prespecified to assess the effect of trilaciclib on myelosuppression and antitumor efficacy.

Results

A total of 122 patients were enrolled, with 19 patients in part 1 and 75 patients in part 2 receiving study drug. Improvements were seen with trilaciclib in neutrophil, RBC (red blood cell) and lymphocyte measures. Safety on trilaciclib+E/P was improved with fewer ≥G3 adverse events (AEs) in trilaciclib (50%) versus placebo (83.8%), primarily due to less hematological toxicity. No trilaciclib-related ≥G3 AEs occurred. Antitumor efficacy assessment for trilaciclib versus placebo, respectively, showed: ORR (66.7% versus 56.8%, P = 0.3831); median PFS [6.2 versus 5.0 m; hazard ratio (HR) 0.71; P = 0.1695]; and OS (10.9 versus 10.6 m; HR 0.87; P = 0.6107).

Conclusion

Trilaciclib demonstrated an improvement in the patient’s tolerability of chemotherapy as shown by myelopreservation across multiple hematopoietic lineages resulting in fewer supportive care interventions and dose reductions, improved safety profile, and no detriment to antitumor efficacy. These data demonstrate strong proof-of-concept for trilaciclib’s myelopreservation benefits.

Clinical Trail number

Keywords: neutropenia, anemia, small-cell lung cancer, myelopreservation, trilaciclib, CDK4/6

Key Message

The addition of trilaciclib to carboplatin and etoposide chemotherapy for extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer improves safety, driven by decreased hematologic toxicity. RR, PFS, and OS are at least comparable to treatment with cytotoxic chemotherapy alone.

Introduction

While efforts to improve cancer patient care have primarily focused on therapies to delay disease progression and increase survival, a reduction in the toxicity of cancer chemotherapies can also provide clinical benefit to patients. This is particularly important for diseases such as small-cell lung cancer (SCLC), where the current standard of care relies on highly myelotoxic chemotherapy, and the patient population is often elderly with multiple comorbid conditions that increase the risk of chemotherapy-induced toxicity. Currently, there is no single available therapy that prevents the myelosuppressive effects of chemotherapy in more than one lineage. Although growth factors [granulocyte-colony-stimulating factors (G-CSF) and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs)] and transfusions are used to treat myelosuppression, these interventions are lineage specific, used after chemotherapy has done its damage, and introduce their own set of associated additional risks. An alternative approach where the bone marrow is protected from the cytotoxicity of chemotherapy, thereby leading to protection of multiple lineages simultaneously, would be clinically meaningful.

Trilaciclib is a highly potent, selective, and reversible, cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 (CDK4/6) inhibitor that transiently maintains G1 cell cycle arrest of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPC), thus preserving them from damage by cytotoxic chemotherapy (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online) [1, 2]. In animal models, trilaciclib administered before chemotherapy results in improved blood cell count recovery, reduced myeloid-biased differentiation, preservation of HSPC and immune system function, and enhanced antitumor efficacy [1–4]. Additional preclinical studies demonstrate that preserving immune system function with trilaciclib may enhance the efficacy of cytotoxic chemotherapy combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors [5–7].

This was a proof-of-concept study, designed to assess the ability of trilaciclib to reduce chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression and improve safety across multiple hematopoietic lineages. SCLC was chosen as the first clinical setting to test the potential myelopreservation benefit of trilaciclib because: (i) SCLC treatment is notable for the degree of myelotoxicity; (ii) SCLC tumor cells replicate independently of CDK4/6 through the obligate loss of Retinoblastoma (RB1) [8], thereby allowing assessment of trilaciclib’s effects on the host, without any potential direct effects on the tumor; and (iii) SCLC is a chemosensitive tumor, providing an optimal setting to demonstrate that trilaciclib does not antagonize chemotherapy efficacy.

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase Ib/II study conducted in North America and Europe (NCT02499770/EudraCT 2016-001583-11). Eligible patients were ≥18 years of age, had histologically or cytologically confirmed extensive-stage SCLC, measurable disease by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), Version 1.1, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0–2 and adequate organ function (see protocol in supplementary Material, available at Annals of Oncology online).

This study was designed and conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Council for Harmonisation. The study protocol and all study-related materials were approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee of each investigational site. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before the initiation of study procedures.

Randomization and procedures

Part 1 of the study included a phase Ib, open-label, dose-finding portion followed by a phase IIa, open-label, expansion at the recommended phase II dose (RP2D). Part 2 was a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II with patients randomized 1 : 1 to receive chemotherapy plus trilaciclib or placebo and stratified by ECOG performance status (0–1 versus 2).

All patients received carboplatin (AUC 5) on day 1 and etoposide [100 mg/m2; etoposide/carboplatin (E/P)] on days 1–3. Trilaciclib or placebo was administered intravenously once daily before chemotherapy. Patients in Part 1 of the study received trilaciclib 200 or 240 mg/m2, and patients in Part 2 were randomized to trilaciclib 240 mg/m2 or placebo. Dose modifications were allowed for chemotherapy but not for trilaciclib. Growth factors were administered per ASCO guidelines (no primary prophylaxis in cycle 1); otherwise supportive care including transfusions was allowed as needed throughout the treatment period.

Adverse events (AEs) and laboratory abnormalities were graded with the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE), v.4.03. Dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs; applicable to cycle 1 of the phase Ib part 1) were drug-related toxicities as defined in the protocol. In both parts, study drug administration continued until completion of chemotherapy as determined by the investigator (generally four to six cycles), disease progression per RECIST, v.1.1, unacceptable toxicity, withdrawal of consent, or discontinuation by investigator. Blood samples were collected to monitor clinical laboratory assessments and measure PK parameters.

A safety monitoring committee reviewed safety, DLT and PK data in part 1 and made cohort and trilaciclib dose recommendations. In Part 2, an independent data monitoring committee monitored safety and disposition data approximately every 4 months.

Outcomes and statistical analysis

The primary objective of the study was to define the trilaciclib RP2D (part 1) and to assess the safety and tolerability of trilaciclib with E/P (parts 1 and 2). To test whether trilaciclib can reduce chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression, assessment of trilaciclib efficacy included the evaluation of a number of common myelosuppression end points across multiple hematopoietic lineages (e.g. hematologic AEs, laboratory values, supportive care interventions). In addition, an exploratory composite end point of major adverse hematological events (MAHE) was developed to assess the totality of myelopreservation benefit, including analysis of several clinically relevant, but low-frequency events. Time-to-first MAHE was prospectively defined, and a post hoc end point, total number of MAHE, was evaluated using an alternative list of components (described below and in supplementary Methods, available at Annals of Oncology online).

As an exploratory study, the initial sample size was determined based on clinical rather than statistical considerations. For non-comparative results from a treatment group [e.g. median progression-free survival (PFS), median overall survival (OS), overall response rate (ORR)], 95% CIs were presented. Since part 2 was exploratory, trilaciclib was compared with placebo at a significance level of two-sided α = 0.2 [9]. Where appropriate, model-based point estimates, along with their associated two-sided 80% CIs were presented with the two-sided P-value. The stratification factor of ECOG performance status (0–1 versus 2) was adjusted in the analyses. Binary end points were analyzed using a stratified exact Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel (CMH) model, and their adjusted proportion difference was calculated using CMH weight [10]. For time-to-event end points, in addition to the Kaplan–Meier method, P-values were obtained from a stratified log-rank test, and the hazard ratio (HR) was calculated from a Cox proportional hazard model. Post hoc subgroup analyses were also conducted, including the use of the Poisson model to account for varying duration of treatment in the analysis of the count variable of total number of MAHE. No formal multiplicity adjustment was carried out to control for multiple analyses. All statistical analyses were carried out with SAS software, v.9.4.

Results

A total of 122 patients were enrolled in the study and 94 patients received study drug per protocol (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Of note, one patient was treated without randomization, in violation of study procedures; the site was immediately shut down and the patient excluded from analysis. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were generally comparable across the treatment groups (Table 1) with the following exceptions for part 2: (i) brain metastases and patients ≥65 years were more common in the placebo group (Table 1) and (ii) cardiovascular conditions were less common in the placebo group (7/38, 18.4%) compared with the trilaciclib group (15/39, 38.5%). In both parts of the study, disease progression was the main reason for study drug discontinuation before completion of therapy.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline disease characteristics

| Category | Part 1 |

Part 2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort 1 (E/P+trilaciclib 200 mg/m2) (N = 10) | Cohort 2 (E/P+trilaciclib 240 mg/m2) (N = 9) | E/P+placebo (N = 38) | E/P+trilaciclib 240 mg/m2 (N = 39) | Total (N = 77) | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 70 (11.6) | 62 (8.6) | 65 (9.5) | 65 (8.4) | 65 (8.9) |

| Median | 74 | 61 | 66 | 64 | 66 |

| Min, Max | 45, 80 | 51, 76 | 39, 86 | 49, 82 | 39, 86 |

| Age group, n (%) | |||||

| <65 | 2 (20.0%) | 5 (55.6%) | 17 (44.7%) | 20 (51.3%) | 37 (48.1%) |

| ≥65 | 8 (80.0%) | 4 (44.4%) | 21 (55.3%) | 19 (48.7%) | 40 (51.9%) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||

| Male | 4 (40.0%) | 7 (77.8%) | 27 (71.1%) | 27 (69.2%) | 54 (70.1%) |

| Female | 6 (60.0%) | 2 (22.2%) | 11 (28.9%) | 12 (30.8%) | 23 (29.9%) |

| Body surface area (m2) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.76 (0.165) | 2.06 (0.266) | 1.91 (0.210) | 1.89 (0.223) | 1.90 (0.216) |

| ECOG score, n (%) | |||||

| 0–1 | NA | NA | 35 (92.1%) | 35 (89.7%) | 70 (90.9%) |

| 2 | NA | NA | 3 (7.9%)a | 4 (10.3%) | 7 (9.1%) |

| Weight loss in 6 months before randomizationb | |||||

| Yes | 7 (70.0%) | 3 (33.3%) | 14 (36.8%) | 16 (41.0%) | 30 (39.0%) |

| >5% | 6 (85.7%) | 0 | 7 (50.0%) | 10 (62.5%) | 17 (56.7%) |

| ≤5% | 1 (14.3%) | 3 (100.0%) | 7 (50.0%) | 6 (37.5%) | 13 (43.3%) |

| Brain metastases, n (%)c | |||||

| Present | 2 (20.0%) | 1 (11.1%) | 8 (21.1%) | 5 (12.8%) | 13 (16.9%) |

| Baseline LDH, n (%) | |||||

| ≤ULN | 1 (10.0%) | 3 (33.3%) | 18 (47.4%) | 16 (41.0%) | 34 (44.2%) |

| >ULN | 9 (90.0%) | 6 (66.7%) | 17 (44.7%) | 21 (53.8%) | 38 (49.4%) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 3 (7.9%) | 2 (5.1%) | 5 (6.5%) |

| Any prior radiation therapy, n (%) | |||||

| Yes | 2 (20.0%) | 0 | 4 (10.5%) | 3 (7.7%) | 7 (9.1%) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||||

| Never smoked | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Former smokers | 8 (80.0%) | 7 (77.8%) | 25 (65.8%) | 25 (64.1%) | 50 (64.9%) |

| Current smokers | 2 (20.0%) | 2 (22.2%) | 12 (31.6%) | 14 (35.9%) | 26 (33.8%) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.6%) | 0 | 1 (1.3%) |

Due to data discrepancies, one patient in the placebo group was labeled as having an ECOG performance score of 2 at randomization but had an ECOG performance score of 0 on Cycle 1 Day 1.

Percentages are based on the number of patients with weight loss.

Patients with brain metastases at baseline could enroll if they were asymptomatic, did not require urgent treatment, and were off all steroids, i.e., did not require treatment prior to enrollment.

E/P, standard of care (etoposide + carboplatin); SD, standard deviation; Min, minimum; Max, maximum; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ULN, upper limit of normal; mg, milligram; m2, meter squared; N, number of patients.

Part 1: phase Ib/IIa

Hematological treatment emergent AEs (TEAEs) were the most commonly reported AEs in part 1. Patients in Cohort 2 (240 mg/m2) reported fewer ≥grade 3 hematologic AEs (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online) and fewer ≥grade 3 hematologic laboratory abnormalities compared with Cohort 1 (200 mg/m2) (supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). Cohort 2 patients had reduced G-CSF use (3, 33.3% versus 5, 50.0%), ESA use (0, 0% versus 2, 20.0%), RBC transfusions (1, 11.1% versus 4, 40.0%), platelet transfusions (0, 0% versus 1, 10%), infection SAEs (serious adverse events; 1, 11.1% versus 2, 20.0%) and intravenous antibiotic use (1, 11.1% versus 4, 40.0%) compared with Cohort 1. Overall, trilaciclib 240 mg/m2 showed a greater reduction in myelosuppression in more than 1 lineage and fewer ≥grade 3 hematologic AEs compared with 200 mg/m2, supporting its selection as the RP2D.

Noncompartmental PK parameters for trilaciclib, etoposide and carboplatin are summarized in supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online. Pharmacokinetic analysis demonstrated little or no accumulation during 3 days of dosing for trilaciclib or etoposide. Etoposide and carboplatin pharmacokinetics did not appear to be affected by coadministration of trilaciclib when compared with historical PK parameters [11–14].

In Cohort 1 (trilaciclib 200 mg/m2) RR was 80%, median PFS 5.3 months [95% CI 0.1, 6.1], and median OS 10.6 [1.2, 25.1]. In Cohort 2 (trilaciclib 240 mg/m2) RR was 100%, median PFS 6.3 [95% CI 4.5, 9.1], and median OS 12.8 [6.3, 13.6].

Part 2: randomized phase II

In part 2, the number of cycles completed was comparable between treatment groups [E/P +trilaciclib 240 mg/m2 (trilaciclib) versus E/P +placebo (placebo)]. However, the relative dose intensities were higher for trilaciclib compared with placebo for both etoposide and carboplatin (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). This was consistent with fewer patients experiencing cycle delays (39.5% versus 67.6%; P = 0.0170) and dose reductions (7.9% versus 35.1% for both etoposide and carboplatin; P = 0.0033) for trilaciclib compared with placebo, respectively (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Efficacy of trilaciclib to prevent myelosuppression

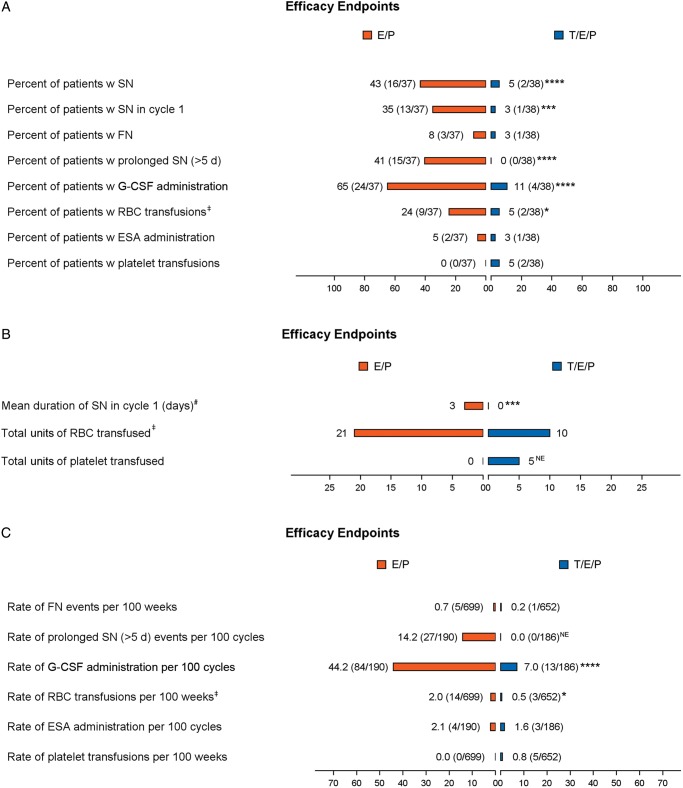

Trilaciclib clinically and significantly reduced both the duration of severe neutropenia (DSN) in cycle 1, a surrogate for febrile neutropenia (FN) and infections, and the occurrence of severe neutropenia (SN) (Figure 1; supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). For those patients in the trilaciclib group who did experience SN, the duration of those events was shorter compared with placebo (median duration of 3 versus 8 days). Additional supportive neutrophil-related end points all favored trilaciclib (Figure 1). A similar trend for improved RBC end points favoring trilaciclib was also seen, including a statistically significant reduction in the percent of patients receiving RBC transfusions (on/after 5 weeks) and the rate of RBC transfusions per 100 weeks. Clinically relevant platelet events were too few to assess the efficacy of trilaciclib on this lineage.

Figure 1.

Myelosuppression end points. Assessment of myelosuppression end points across hematological lineages. (A) Occurrence of specified end point per treatment group represented as percent (number of patients with at least one event/total number of patients per group). (B) Summary of the duration of SN in cycle 1 and the total units of RBCs or platelets transfused per treatment group. (C) Number of episodes of specified end point reported as event rate per 100 weeks or 100 cycles (number of events/cumulative number of weeks or cycles). Statistical significance: * ≤0.05, ** ≤0.01, *** ≤0.001, **** ≤0.0001. NE, not estimable; orange, E/P + Placebo (E/P); blue, E/P + Trilaciclib 240 mg/m2 (T/E/P); SN, severe (grade 4) neutropenia; FN, febrile neutropenia; RBC, red blood cell; ESA, erythropoietin-stimulating agent; G-CSF, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; d, day; w, with. ‡Analysis only includes RBC transfusions on/after 5 weeks of treatment. #Mean duration of SN in cycle 1 per treatment group (including patients without an event, whose duration is 0 days).

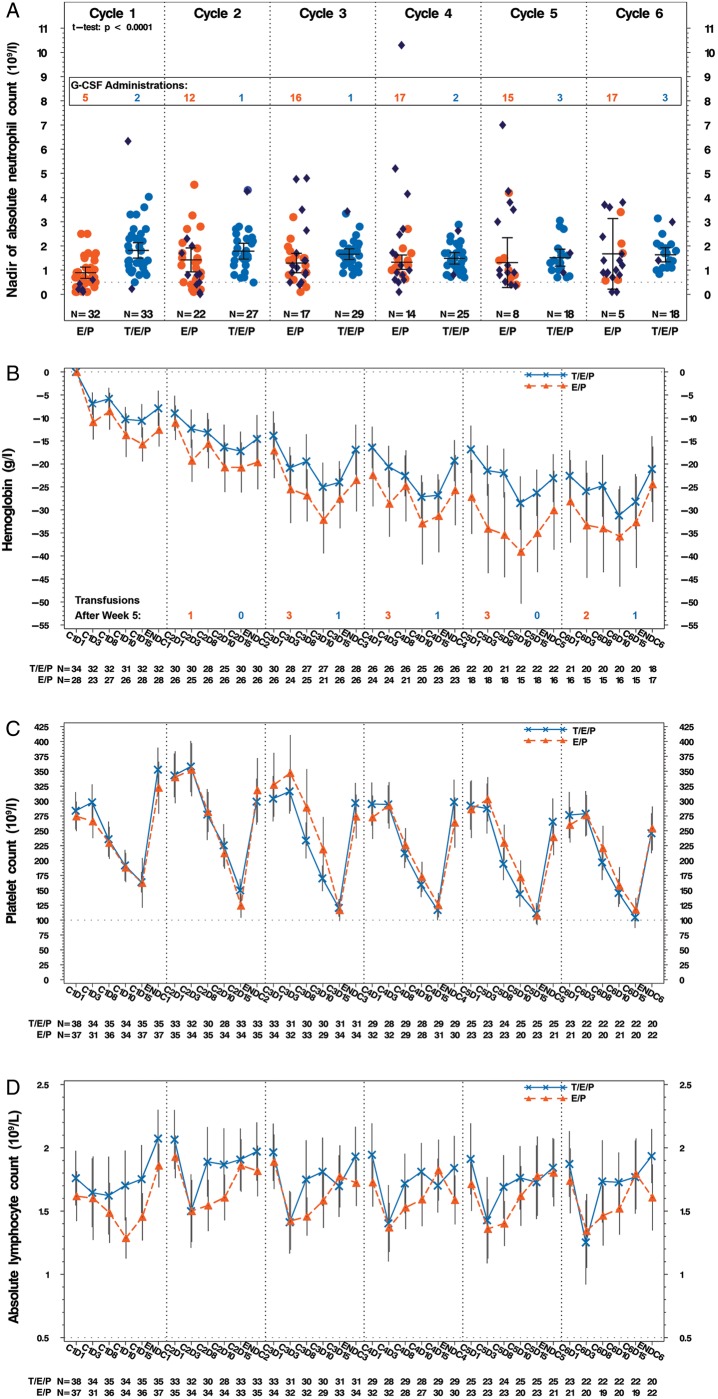

Consistent with trilaciclib’s mechanism of action (MOA) to protect the HSPC, evaluation of complete blood cell counts revealed trilaciclib significantly improved ANC nadirs in cycle 1, delayed hemoglobin decline over time and led to a faster recovery of lymphocytes (Figure 2; supplementary Figure S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). Unlike approaches to stimulate new RBC production (ESAs) or replace RBCs (transfusions), protection with trilaciclib appears to slow the rate of hemoglobin decline over time as evidenced by (i) a lower absolute and mean change in hemoglobin from baseline for trilaciclib compared with placebo with the difference more pronounced in later cycles (Figure 2B;supplementary Figure S7, available at Annals of Oncology online) and (ii) more patients in the placebo group requiring RBC transfusions in later cycles (supplementary Figure S6, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 2.

Hematology assessments. Hematological assessments were scheduled on days 1, 3, 8, 10, 15, and 22 of each cycle. (A) Mean nadir values (with 95% CI) for ANC for each cycle for patients who did not receive G-CSF. Dark blue dots represent the nadir for patients receiving G-CSF in each group, but the data are not included in the mean±95% CI calculations. The dotted line represents the value required to start each new cycle, i.e. 1.5×109/l. The number of patients receiving G-CSF for each cycle is overlaid on the graph. Comparison of cycle 1 ANC nadir was made using Student’s t-test. (B) Mean (with 95% CI) change from baseline in hemoglobin in g/l. Patients who received transfusions or ESAs were excluded. The number of patients receiving RBC transfusions per cycle is overlaid in the graph. (C) and (D) Mean counts (with 95% CI) over time for platelet and lymphocytes, respectively. The dotted line on (C) represents the value required to start each new cycle, i.e. 100×109/l. The dotted line on (D) represents a CTCAE grade 3 lymphocyte count decreased value, i.e. 0.5×109/l. orange, E/P + Placebo (E/P); blue, E/P + Trilaciclib 240 mg/m2 (T/E/P); C, cycle; D, day; ENDC, end of cycle which is defined as the last value measured prior to the first day of dosing in the subsequent cycle; CI, confidence interval; Gr, grade; G-CSF, granulocyte colony stimulating factor; l, liter; g, gram; N, number of patients.

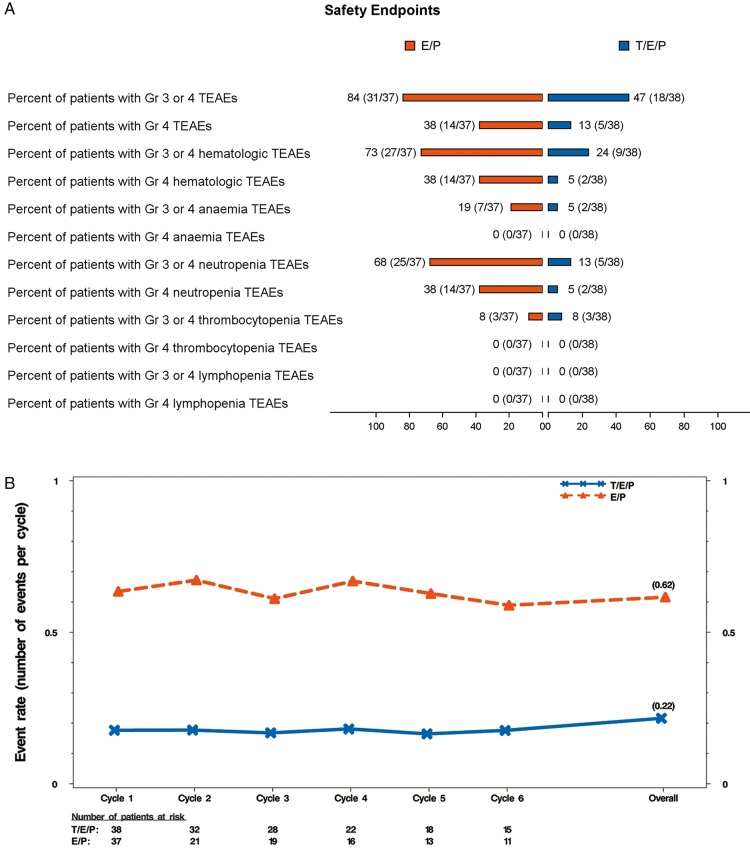

Almost all patients reported at least one TEAE (supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). While the addition of trilaciclib to chemotherapy may increase the frequency of some low-grade toxicities (e.g. headache), this is outweighed by the clinically meaningful decrease in high grade (≥grade 3) toxicities, which is mostly due to significantly fewer ≥grade 3 hematologic TEAEs (Figure 3A). The number of patients with SAEs was comparable for the trilaciclib and placebo groups (11/38 patients, 28.9% versus 9/37 patients, 24.3%, respectively).

Figure 3.

Safety end points and major adverse hematological events (MAHE) composite. (A) Occurrence of grade 3 or 4 TEAEs (all, hematologic, lineage specific; see supplementary Methods, available at Annals of Oncology online for description) per treatment group represented as percent (number of patients with at least one TEAE/total number of patients per group). (B) Event rate over time for modified MAHE defined using the following events: (1) hospitalization for any reason, (2) febrile neutropenia, (3) death for any reason, (4) dose reduction for any reason, (5) duration of severe (grade 4) neutropenia >5 days, and (6) RBC transfusions occurring on/after 5 weeks after start of treatment. Event rates were calculated using the Poisson method accounting for the ECOG status (0-1 versus 2) as the stratification factor. Events occurring between the first dose and 60 days after the last dose of study drug were included in the event rate over time analysis. orange, E/P + Placebo (E/P); blue, E/P + Trilaciclib 240 mg/m2 (T/E/P). TEAEs, treatment emergent adverse events; MAHE, major adverse hematologic event; RBC, red blood cell.

To assess the totality of myelopreservation benefit, including analysis of several clinically relevant, but low-frequency events, a composite end point of time-to-first MAHE was developed. There were more patients with first MAHE in the placebo group compared with the trilaciclib group (30 versus 11, respectively) and the time-to-first MAHE was significantly shorter for placebo (1 month) versus trilaciclib (not estimable) (supplementary Figure S8, available at Annals of Oncology online; HR of 0.19; P-value <0.0001). Since most patients would be expected to experience more than one event and treatment would generally continue despite those events, a post hoc event rate analysis was carried out using a modified MAHE end point with alternative components. The number of MAHE per cycle was clinically and statistically greater for placebo compared with trilaciclib (Figure 3B).

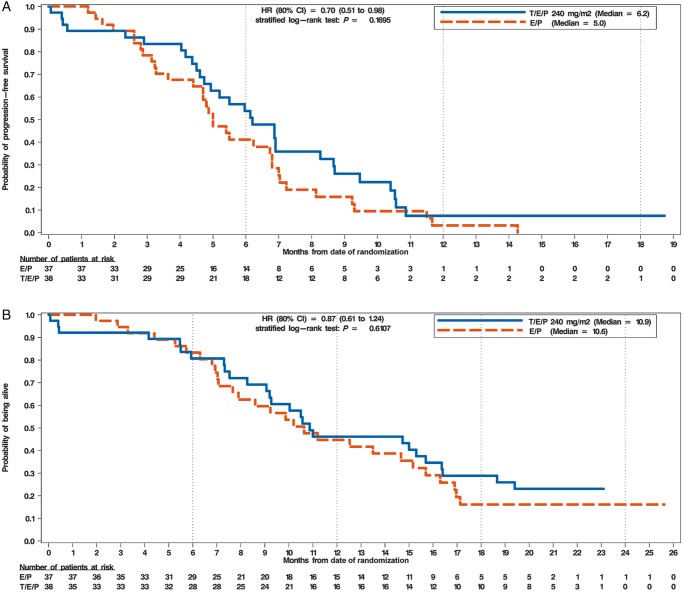

Antitumor efficacy in part 2

Investigator assessed ORR for the response assessable population was higher for trilaciclib (66.7%) than for placebo (56.8%) (supplementary Figure S4B, available at Annals of Oncology online); however, statistical significance was not reached (P = 0.3831). The median duration of response was comparable for trilaciclib and placebo (5.7 versus 5.4 months, respectively). Median PFS (interquartile range; IQR) was numerically longer for trilaciclib [6.2 (4.7, 8.3) months] than placebo [5.0 (4.4, 6.8) months; HR 0.70; P = 0.1695] (Figure 4A). A subgroup analysis suggests that, in general, patients in the trilaciclib group had a longer PFS than those on placebo across all subgroups (supplementary Figure S9, available at Annals of Oncology online) except for patients with ECOG 2 performance status and baseline brain metastases. Median OS (IQR) was comparable for the placebo and trilaciclib groups [10.6 (7.7, 15.2) months versus 10.9 (9.1, 16.4), respectively; HR 0.87; P = 0.6107] (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Progression-free and overall survival. (A) Kaplan–Meier analysis of progression-free survival. The x-axis depicts months from first dose of study drug administration and number of patients at risk. The y-axis depicts the probability of being progression-free. (B) Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival. The x-axis depicts months from first dose of study drug administration and number of patients at risk. The y-axis depicts the probability of being alive. The HR and its 80% CI are calculated using the Cox regression model and the P-value is calculated using the stratified log-rank method. Baseline ECOG status (0-1 versus 2) was used as the stratification factor for both the HR and P-value calculations. orange, E/P + Placebo (E/P); blue, E/P + Trilaciclib 240 mg/m2 (T/E/P); HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; mg, milligram; m2, meter squared.

Discussion

To our knowledge, trilaciclib is the first agent with the potential to preserve HSPC and immune system function during chemotherapy. The phase I portion of this trial established trilaciclib 240 mg/m2 as the RP2D when used in combination with E/P. Results from the randomized phase II portion suggest that the patient’s experience on chemotherapy may be improved with trilaciclib as shown by an improved safety profile and a decrease in clinically meaningful chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression which places patients at substantial risk of additional intervention(s), hospitalization, and even death. Additionally, patient reported outcomes data, collected with a validated instrument, further demonstrates an improved experience for patients who received trilaciclib [15]. Trilaciclib did not have a detrimental effect on chemotherapy efficacy.

As an exploratory study, a number of outcomes across multiple hematological lineages were evaluated. Of these, several are validated surrogate end points that have been used to demonstrate clinically meaningful benefit to patients. DSN is strongly predictive of the incidence of chemotherapy-induced FN, and a reduction in DSN correlates with reduced incidence of FN, infectious episodes, IV antibiotic use, and hospitalization (as established by filgrastim). Therefore, while the incidence of FN in this study was low likely due to the confounding use of G-CSF (predominantly in the placebo group), the reduction in DSN by trilaciclib can be interpreted as clinically meaningful.

Similarly, a reduction in RBC transfusions as a marker of fewer high-grade anemia events is also clinically meaningful since chemotherapy-induced anemia can affect patient quality of life, morbidity, and mortality. In the current study, trilaciclib decreased the need for RBC transfusions (patients requiring RBC transfusions, number of transfusions over time, units transfused) in the setting of reduced high grade anemia (≥grade 3). Furthermore, patients receiving trilaciclib had a slower decline in hemoglobin values over time compared with placebo. Collectively, these data support trilaciclib’s clinical benefit for a second hematological lineage.

Patients in the trilaciclib group had fewer ≥grade 3 AEs, primarily due to a reduction in hematological ≥grade 3 AEs. Although time-to-first MAHE was prospectively defined, evaluating the cumulative incidence of MAHE using both prespecified and modified components was considered to be a more appropriate measure of the consequences of myelosuppression. By all measures, trilaciclib demonstrated a robust improvement in the MAHE composite end point further supporting its unique MOA to protect HSPC from chemotherapy damage. These data support trilaciclib’s ability to improve the overall safety profile of this chemotherapy regimen. Similar MAHE results have been observed when trilaciclib was added to gemcitabine plus carboplatin for the treatment of triple-negative breast cancer [16].

The study followed standard supportive care (SSC) clinical practice guidelines for the use of G-CSF, ESAs and transfusions. Per the guidelines, primary prophylactic G-CSF was not allowed in cycle 1, and in that regard, the current study is a comparison to SSC. We believe this is a fair comparison given trilaciclib’s mechanism to protect HSPC from chemotherapy damage as opposed to rescue with growth factors, which are given after chemotherapy to stimulate surviving cells. Compared with SSC, the addition of trilaciclib to E/P improved the overall safety profile of the regimen as shown by the reduction in high grade AEs without adversely affecting the antitumor efficacy. Additionally, trilaciclib demonstrated improvement across multiple clinically meaningful myelosuppression end points, which currently cannot be addressed by a single existing intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank and acknowledge all the patients, their families, and study personnel for participating in the study. We thank the members of the independent data monitoring committee, Drs D. Ross Camidge and Jeffrey Crawford. We thank Ann Li and Jie Xiao of G1 Therapeutics for data analysis support. Finally, the authors acknowledge Wendy Anders for assisting with figure preparation and Aubri Charboneau of Sage Scientific Writing, LLC for writing support for the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by G1 Therapeutics, Inc (no grant numbers apply).

Disclosure

SA, JMA, AYL, JAS, ZY, RKM, SRM, and PJR are all employees of G1 Therapeutics. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Bisi JE, Sorrentino JA, Roberts PJ. et al. Preclinical characterization of G1T28: a novel CDK4/6 inhibitor for reduction of chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression. Mol Cancer Ther 2016; 15(5): 783–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. He S, Roberts PJ, Sorrentino JA. et al. Transient CDK4/6 inhibition protects hematopoietic stem cells from chemotherapy-induced exhaustion. Sci Transl Med 2017; 9: eaal3986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnson SM, Torrice CD, Bell JF. et al. Mitigation of hematologic radiation toxicity in mice through pharmacological quiescence induced by CDK4/6 inhibition. J Clin Invest 2010; 120(7): 2528–2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roberts PJ, Bisi JE, Strum JC. et al. Multiple roles of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012; 104(6): 476–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deng J, Wang ES, Jenkins RW. et al. CDK4/6 inhibition augments antitumor immunity by enhancing T-cell activation. Cancer Discov 2018; 8(2): 216–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lai AY, Sorrentino JA, Strum JC, Roberts PJ.. Abstract 1752: transient exposure of trilaciclib, a CDK4/6 inhibitor, modulates gene expression in tumor immune infiltrates to promote a pro-inflammatory tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res 2018; 78: 1752. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sorrentino JA, Lai AY, Strum JC, Roberts PJ, Abstract 5628: trilaciclib (G1T28), a CDK4/6 inhibitor, enhances the efficacy of combination chemotherapy and immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment in preclinical models. Cancer Res 2017; 77: 5628.28904063 [Google Scholar]

- 8. George J, Lim JS, Jang SJ. et al. Comprehensive genomic profiles of small cell lung cancer. Nature 2015; 524(7563): 47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brown SR, Gregory WM, Twelves C, Brown J.. A Practical Guide to Designing Phase II Trials in Oncology. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2014; 1 (online resource). [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim YW. Adjusted Proportion Difference and Confidence Interval in Stratified Randomized Trials. PharmaSUG, Chicago, May 12–15, 2013; Paper SP-04.

- 11. Arbuck SG, Douglass HO, Crom WR. et al. Etoposide pharmacokinetics in patients with normal and abnormal organ function. J Clin Oncol 1986; 4(11): 1690–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Elferink F, van der Vijgh WJ, Klein I. et al. Pharmacokinetics of carboplatin after i.v. administration. Cancer Treat Rep 1987; 71(12): 1231–1237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaul S, Igwemezie LN, Stewart DJ. et al. Pharmacokinetics and bioequivalence of etoposide following intravenous administration of etoposide phosphate and etoposide in patients with solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 1995; 13(11): 2835–2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van der Vijgh WJ. Clinical pharmacokinetics of carboplatin. Clin Pharmacokinet 1991; 21(4): 242–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weiss JS, Gwaltney C, Daniel D. et al. Positive effects of trilaciclib on patient myelosuppression-related symptoms and functioning: results from three phase 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled small cell lung cancer trials. Support Care Cancer 2019; 27: S274. [Google Scholar]

- 16. O'Shaughnessy JW, Thummala AR, Danso MA. et al. Trilaciclib (T), a CDK4/6 inhibitor, dosed with gemcitabine (G), carboplatin (C) in metastatic triple negative breast cancer (mTNBC) patients: preliminary phase 2 results. Cancer Res 2019; 79: PD1-01. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.