Abstract

Background

It remains unknown to what extent consensus molecular subtype (CMS) groups and immune-stromal infiltration patterns improve our ability to predict outcomes over tumor–node–metastasis (TNM) staging and microsatellite instability (MSI) status in early-stage colorectal cancer (CRC).

Patients and methods

We carried out a comprehensive retrospective biomarker analysis of prognostic markers in adjuvant chemotherapy-untreated (N = 1656) and treated (N = 980), stage II (N = 1799) and III (N = 837) CRCs. We defined CMS scores and estimated CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes (CytoLym) and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) infiltration scores from bulk tumor tissue transcriptomes (CMSclassifier and MCPcounter R packages); constructed a stratified multivariable Cox model for disease-free survival (DFS); and calculated the relative proportion of explained variation by each marker (clinicopathological [ClinPath], genomics [Gen: MSI, BRAF and KRAS mutations], CMS scores [CMS] and microenvironment cells [MicroCells: CytoLym+CAF]).

Results

In multivariable models, only ClinPath and MicroCells remained significant prognostic factors, with both CytoLym and CAF infiltration scores improving survival prediction beyond other markers. The explained variation for DFS models of ClinPath, MicroCells, Gen markers and CMS4 scores was 77%, 14%, 5.3% and 3.7%, respectively, in stage II; and 55.9%, 35.1%, 4.1% and 0.9%, respectively, in stage III. Patients whose tumors were CytoLym high/CAF low had better DFS than other strata [HR=0.71 (0.6–0.9); P = 0.004]. Microsatellite stable tumors had the strongest signal for improved outcomes with CytoLym high scores (interaction P = 0.04) and the poor prognosis linked to high CAF scores was limited to stage III disease (interaction P = 0.04).

Conclusions

Our results confirm that tumor microenvironment infiltration patterns represent potent determinants of the risk for distant dissemination in early-stage CRC. Multivariable models suggest that the prognostic value of MSI and CMS groups is largely explained by CytoLym and CAF infiltration patterns.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, prognosis, microsatellite instability, CMS, immune, stromal

Key Message

In multivariable prognostic models that incorporate clinicopathological features, microsatellite instability status, consensus molecular subtype groups and microenvironment signatures, the most critical drivers of disease recurrence or death in early-stage colorectal cancer, on top of TNM staging, were infiltration scores of cytotoxic lymphocytes and cancer-associated fibroblasts.

Introduction

Management of locoregional colorectal cancer (CRC) is still largely dictated by tumor–node–metastasis (TNM) status at diagnosis, despite the multitude of prognostic biomarker research over the recent years. Depth of tumor wall invasion (pT1−pT4) and lymph node (LN) involvement (pN0−pN2) are strongly associated with 5-year disease-free survival (DFS), which ranges from 30% to 90% [1, 2]. The decision to offer adjuvant chemotherapy, particularly in stage II relies on clinicopathological features such as bowel obstruction or perforation at presentation, number of LNs examined, lymphovascular or perineural invasion and tumor grade [3]. The only molecular marker with clinical utility in early-stage CRC is microsatellite instability (MSI), which is universally recommended for diagnosis of Lynch Syndrome, but also defines a stage II population (irrespective of germline or sporadic background) with significantly improved when treated with surgery alone [4]. There are no validated molecular markers to help identify patient populations with increased benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy in locoregional CRC.

Previously, we have estimated the value of clinicopathological features, MSI and additional molecular markers, namely BRAFV600E and KRAS exon 2 mutations, in prognostic models of stage II/III (early-stage) CRC [4]. We found that incorporation of MSI and driver gene mutation status to overall survival models with TNM staging does improve the prognostic discriminatory power, but only modestly increases prediction accuracy in multivariable models that include detailed clinicopathological annotation, particularly in chemotherapy-treated patients. Importantly, there was only one genomically defined subgroup of CRC with consistently higher risk of death across multiple cohorts, namely patients whose tumors were microsatellite stable (MSS) and BRAFV600E mutated, which corresponded to only 6% of the stage II/III population. Discovery of additional clinically relevant subgroups with potentially targetable pathway dependencies and/or cancer microenvironment features has the potential to guide adjuvant treatment strategies in broader patient populations.

Tumor microenvironment markers have demonstrated independent prognostic value in stage II/III CRC, with a high density of CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CytoLym) infiltration being consistently associated with prolonged survival [5–8]. Indeed, an immunohistochemistry-based scoring system has been developed (termed Immunoscore®) to quantify cytotoxic and memory T cells in the tumor center/invasive margin, which proved to be a strong prognostic index in early-stage CRC [8]. Several authors have suggested that the dense CytoLym infiltrate could explain the better prognosis of tumors displaying MSI, compared with MSS CRC [9, 10]. In addition, a subset of MSS tumors harbors prominent expression of immune cytotoxic markers (up to 30% of the stage II/III population), and multivariable models revealed that Immunoscore® was superior to MSI status in predicting disease-specific recurrence and patient survival [10]. Furthermore, gene expression signatures that reflect epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor infiltration with cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) also constitute independent prognostic indicators in early stages, with dismal outcomes for patients with an invasive stromal-rich microenvironment [11, 12]. These markers are not as thoroughly validated as Immunoscore(R), but they are reflected in the transcriptomic-based consensus molecular subtypes (CMS) of CRC, which have also been linked to patient outcome in early-stage CRC. High CAFs content (CMS4 Mesenchymal) and CytoLym infiltration (CMS1 MSI Immune) are important features of the tumor microenvironment in early-stage CRC, with poor and good prognosis, respectively. The dismal DFS rates for CMS4 tumors is independent of clinicopathological markers, KRAS or BRAFV600E mutations and MSI status [13, 14]. Interestingly, CMS4 tumors have high expression of genes specific for both CAFs and CytoLym, counterbalanced by immunosuppressive cells, such as Treg cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, monocytic derived cells and TH17 cells [15], previously linked to chemotherapy resistance [16, 17].

Given the known interactions between MSI, immune-stromal markers and mesenchymal activation states, only an unbiased multivariable prognostic model that incorporates TNM staging, genomic markers, transcriptomic subtypes and microenvironment features can identify the most critical drivers of disease recurrence in CRC. It is unknown to what extent the combined analysis of immune and stromal infiltration patterns improves prediction of DFS over traditional clinicopathological/molecular markers in stage II/III CRC and whether the potential prognostic effect of microenvironment cells is modulated by adjuvant chemotherapies. Here we describe the results of a comprehensive retrospective biomarker analysis of prognostic markers in chemotherapy-untreated and treated stage II/III CRCs from a large aggregated cohort of clinical studies with molecular data. Our hypothesis was that microenvironment features constitute stronger determinants of disease recurrence in early-stage CRC than genomic or transcriptomic subtypes. We aimed to perform a holistic assessment of the prognostic value of well-known intrinsic biological features of CRC.

Methods—patient population and molecular data

To perform this analysis, we aggregated data from multiple public cohorts and collaborated with different academic groups to have access to private data from prospective series and one clinical trial (Alliance CALGB9581). This project was approved by the Vall d'Hebron Institute of Oncology Ethics Committee. Patients signed informed consent for exploratory biomarker research on samples prospectively collected in accordance with the guidelines of Institutional Review Boards from each organization/clinical trial. Table 1 summarizes the final study population that included 2636 patients diagnosed with stage II/III CRC, untreated (N = 1656) or treated (N = 980) with adjuvant chemotherapy, with clinicopathological and molecular annotation for variables of interest. Transcriptomic data were normalized following standard bioinformatics procedures for CMSclassifier and MCPcounter application independently in each cohort (see supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online for details on gene expression platform and tissue source). We obtained CMS1, CMS2, CMS3 and CMS4 Random Forest posterior probabilities as a continuous value (each ranging from 0–1) and final CMS labels using CMSclassifer R-package [13]. Likewise, the abundance of immune- and nonimmune-stromal cell populations was estimated from gene expression data using MCPcounter R-package [18]. Given the fact that MCPcounter scores are affected by gene expression platform and tissue source, microenvironment cell infiltration scores were scaled (from 0 to 1) first within three subgroups [Affymetrix in fresh frozen samples; Agilent in fresh frozen samples; and Almac-Affymetrix in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples] and then rescaled after data aggregation to facilitate cross-study comparisons. Multiple imputation of random missing values was carried out via the mice R package in the aggregated cohort (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 1.

Patient’s and tumor characteristics

| All (N = 2636) | No adjuvant chemotherapy (N = 1656) | Adjuvant chemotherapy (N = 980) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset public | Variable | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| E-MTAB-864 | 144 | 48.37% | 144 | 49.15% | 0 | 47.04% | |

| GSE14333 | 183 | 99 | 84 | ||||

| GSE17536 | 109 | 55 | 54 | ||||

| GSE24550 | 76 | 57 | 19 | ||||

| GSE31595 | 37 | 26 | 11 | ||||

| GSE33113 | 87 | 87 | 0 | ||||

| GSE37892 | 128 | 71 | 57 | ||||

| GSE38832 | 72 | 34 | 38 | ||||

| GSE39582 | 439 | 241 | 198 | ||||

| Dataset private | CRCSC | 589 | 51.63% | 110 | 50.85% | 479 | 52.96% |

| Oslo | 281 | 241 | 40 | ||||

| CALGB9581 | 393 | 393 | 0 | ||||

| Colonomics | 98 | 98 | 0 | ||||

| Age | Median (min−max) | 69 (22 − 97) | 70 (24–97) | 65 (22–97) | |||

| Sex | Male | 1382 | 52.43% | 867 | 52.36% | 515 | 52.55% |

| Female | 1254 | 47.57% | 789 | 47.64% | 465 | 47.45% | |

| Stage | T1-2N0 | 5 | 0.19% | 5 | 0.30% | 0 | 0% |

| T3N0 | 1606 | 60.93% | 1322 | 79.83% | 284 | 28.98% | |

| T4N0 | 188 | 7.13% | 140 | 8.45% | 48 | 4.90% | |

| T1-2N1 | 41 | 1.56% | 13 | 0.79% | 28 | 2.86% | |

| T3N1 | 461 | 17.49% | 117 | 7.07% | 344 | 35.10% | |

| T4N1 | 54 | 2.05% | 13 | 0.79% | 41 | 4.18% | |

| T1-2N2 | 6 | 0.23% | 2 | 0.12% | 4 | 0.41% | |

| T3N2 | 232 | 8.80% | 37 | 2.23% | 195 | 19.90% | |

| T4N2 | 43 | 1.63% | 7 | 0.42% | 36 | 3.67% | |

| Primary site | Right colon | 1292 | 49.01% | 860 | 51.94% | 432 | 44.08% |

| Left colon | 1177 | 44.65% | 683 | 41.24% | 494 | 50.41% | |

| Rectum | 167 | 6.34% | 113 | 6.82% | 54 | 5.51% | |

| Microsatellite status | Stable (MSS) | 2184 | 82.85% | 1343 | 81.10% | 841 | 85.82% |

| Instable (MSI) | 452 | 17.15% | 313 | 18.90% | 139 | 14.18% | |

| BRAF V600E status | Wt | 2306 | 87.48% | 1414 | 85.39% | 892 | 91.02% |

| Mut | 330 | 12.52% | 242 | 14.61% | 88 | 8.98% | |

| KRAS codons 12/13 status | Wt | 1684 | 63.88% | 1057 | 63.83% | 627 | 63.98% |

| Mut | 952 | 36.12% | 599 | 36.17% | 353 | 36.02% | |

| CMS label | CMS1 | 507 | 19.23% | 339 | 20.47% | 168 | 17.14% |

| CMS2 | 1062 | 40.29% | 673 | 40.64% | 389 | 39.69% | |

| CMS3 | 337 | 12.78% | 218 | 13.16% | 119 | 12.14% | |

| CMS4 | 551 | 20.90% | 334 | 20.17% | 217 | 22.14% | |

| Mixed | 179 | 6.79% | 92 | 5.56% | 87 | 8.88% | |

| CMS4 score | Median (IQR) | 0.10 (0.02–0.38) | 0.10 (0.02–0.35) | 0.11 (0.02–0.43) | |||

| Cytotoxic lymphocyte (CytoLym) infiltration score | Median (IQR) | 0.43 (0.38–0.49) | 0.43 (0.37–0.5) | 0.43 (0.38–0.49) | |||

| Cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF) infiltration score | Median (IQR) | 0.59 (0.49–0.67) | 0.59 (0.48–0.67) | 0.59 (0.51–0.67) | |||

Methods—multivariable survival modeling

Our primary end point was DFS, measured from time of cancer diagnosis until disease relapse or death from any cause. Survival was censored at 72 months based on median follow-up of patients alive. The covariates considered for inclusion in the prognostic models were as follows:

Clinicopathological features (ClinPath): AJCC version 7 pathological tumor stage (pT-stage; pT1, pT2, pT3 and pT4) and pathological nodal stage (pN-stage: pN0, pN1 and pN2), age (continuous), sex (male versus female), primary tumor location [right (caecum to transverse colon) versus left (splenic flexure to sigmoid) or rectum].

Genomic markers (Gen): MSI status (MSI high versus MSS or MSI low), mutations in KRAS codons 12/13 or BRAFV600E (versus wild-type).

Transcriptomic markers (CMS groups): CMS labels either as categorical variables (CMS1, CMS2, CMS3 or CMS4) or as independent continuous scores (CMS1 score, CMS2 score, CMS3 score, CMS4 score) from CMSclassifier R package [13].

Microenvironment infiltration markers (MicroCells): MCPcounter R package scores predict the abundance of 10 cell populations from transcriptomic profiles (CD3+ T cells, CD8+ T cells [CytoLym], CTLs [cytotoxic lymphocytes], NK [Natural Killer] cells, B lymphocytes, monocytic lineage cells, myeloid dendritic cells, neutrophils, endothelial cells and CAFs) [18] as a continuous variable.

Study methodology is summarized in supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online. First, following data aggregation and imputation, we assessed proportional hazards assumption using survival R package. Sex did not hold the assumption of proportional hazards (P < 0.05) and was included in the survival models as a stratification variable, together with gene expression profiling subgroups as defined above (Affymetrix fresh-frozen; Agilent fresh-frozen; Affymetrix-Almac FFPE) and adjuvant chemotherapy status. In order to select variables within the CMS and MicroCells categories with the highest prognostic impact on DFS estimation, we carried out forward and backward stepwise regression using the Bayesian information criterion. Then, multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were formulated using all factors that demonstrated statistical significance for DFS in univariate models (with P < 0.1 according to log-rank test). We investigated significant interactions among genomic, transcriptomic, microenvironment infiltration markers and clinicopathological features with impact on patient outcomes (P < 0.05 according to ANOVA test). Next, the following multivariable models were compared: (i) ClinPath +Gen; (ii) ClinPath +Gen +CMS; (iii) ClinPath +Gen +MicroCells; and (iv) ClinPath +Gen +CMS +MicroCells. We then calculated, using multiple permutations, the relative proportion of explained variation in DFS that was accounted for by the different categories of predictor covariates using survMisc R package [19]. For illustration purposes, continuous scores (CMS and microenvironment cell infiltration) were dichotomized based on the maximization of the log-rank statistic to generate Kaplan−Meier DFS curves using survminer R package. All analyses were carried out using R statistical software version 3.2.5 [20].

Results

Demographics, tumor-related characteristics and molecular markers of the numerous cohorts of patients with stage II or stage III CRC included in survival models are described in Table 1. Patients were recruited in the different studies between 1990 and 2005. Clinicopathological features of our population are in line with other prospective biomarker series (non-clinical trial cohorts), including a relatively elderly population, with stage II representing 85% and 35% of the cases in the untreated and chemotherapy-treated cohorts, respectively. Information on type of adjuvant chemotherapy is missing in most public cohorts, but given the standards of treatment at time of study recruitment, we estimate that <10% of the combined public−private treated populations received oxaliplatin in addition to 5-fluorouracil. The prevalence of molecular markers also mirrors published literature, with 17% MSI tumors, 36% KRAS codons 12/13 mutated, 13% BRAFV600E mutated and 21% CMS4 tumors.

In the variable selection process, CMS4 as a continuous score was a better predictor of DFS than CMS 1/2/3 scores or CMS 1/2/3/4 labels. Also, from 10 MicroCells populations, CytoLym and CAFs infiltration scores were the strongest predictors of DFS. We found no significant inter-study heterogeneity when assessing CytoLym and CAFs scores as dichotomous variables in DFS models (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). On average, CytoLym infiltration scores were highest in CMS1 samples, while CAF scores were highest in CMS4 samples (supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). Indeed, 66% of CMS1 tumors fall in the CytoLym high categories, ∼65% of CMS2 and CMS3 samples are classified as CytoLym low/CAF low and 49% of CMS4 samples are CytoLym low/CAF high (supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). We also found high association between CytoLym infiltration scores and microsatellite status, with 68% of MSI tumors in the CytoLym high categories (supplementary Figure S4, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Clinicopathological and genomic markers, together with continuous CMS4 scores and CytoLym/CAF infiltration scores, were assessed in univariate and multivariable models detailed in Table 2. Importantly, only age, pT stage, pN stage, primary tumor location and immune-stromal infiltration scores were independent prognostic factors in multivariable models. Patients with right-sided tumors had better DFS outcomes than left-sided primaries, both in stage II and III CRC. MSI status and CMS4 scores did not significantly improve prognosis prediction over ClinPath features when CytoLym and CAFs infiltration scores were considered. Analysis of deviance showed that the addition of CytoLym and CAF infiltration scores to ClinPath + Gen +/− CMS models provides significant prognostic information (ANOVA P < 0.05), as detailed in supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online. We found a significant interaction between MSI status and CytoLym scores on DFS models (interaction P = 0.04), with MSS tumors having the strongest signal for improved outcomes when displaying CytoLym high infiltration scores.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariable disease-free survival Cox models (stratified by sex, gene expression profiling platform and adjuvant chemotherapy status)

| Disease-free survival Cox models (all patients) (N = 2 636 769 events) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis |

Multivariable analysis |

|||||

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age | 1.01 | 1–1.02 | <0.001 | 1.01 | 1–1.02 | <0.001 |

| pT2/pT1 versus pT3 | 1.07 | 0.65–1.75 | 0.8 | 0.86 | 0.52–1.43 | 0.56 |

| pT4 versus pT3 | 1.37 | 1.11–1.69 | 0.003 | 1.46 | 1.18–1.81 | <0.001 |

| pN1 versus pN0 | 1.99 | 1.61–2.46 | <0.001 | 2.05 | 1.65–2.55 | <0.001 |

| pN2 versus pN0 | 3.08 | 2.41–3.93 | <0.001 | 3.15 | 2.45–4.05 | <0.001 |

| Rectum versus left | 1.03 | 0.76–1.40 | 0.83 | 0.94 | 0.69–1.29 | 0.72 |

| Right versus left | 0.84 | 0.72–0.97 | 0.02 | 0.86 | 0.73–1.00 | 0.05 |

| MSI versus MSS | 0.76 | 0.61 –0.93 | 0.008 | 0.88 | 0.7–1.11 | 0.29 |

| KRAS mut versus wild-type | 1.04 | 0.9–1.21 | 0.55 | − | − | − |

| BRAF mut versus wild-type | 0.9 | 0.72 − 1.13 | 0.35 | − | − | − |

| CMS4 score | 1.37 | 1.07–1.76 | 0.01 | 0.93 | 0.64–1.32 | 0.67 |

| CAF infiltration score | 1.6 | 0.93–2.74 | 0.09 | 2.54 | 1.08–6.02 | 0.03 |

| CytoLym infiltration score | 0.45 | 0.25–0.78 | 0.005 | 0.26 | 0.12–0.55 | <0.001 |

CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; CytoLym, cytotoxic lymphocytes. P values ≤0.05 displayed in bold.

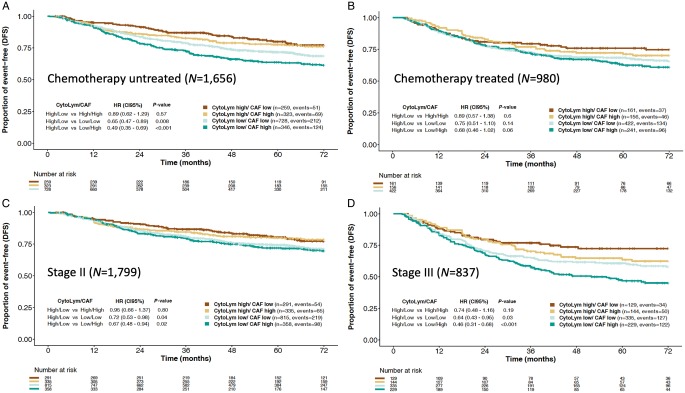

Figure 1 illustrates adjusted Kaplan−Meier DFS curves by CytoLym and CAF infiltration scores in chemotherapy-untreated and treated cohorts, as well as stage II and III CRC populations. Overall, CytoLym high/CAF low population represented 16% of samples, compared with 18% with CytoLym high/CAF high, 22% with CytoLym low/CAF high and 44% harboring CytoLym low/CAF low scores. Patients whose tumors were CytoLym high/CAF low had better DFS than other strata [adjusted HR =0.71 (0.6–0.9); P = 0.004]. In both untreated and treated cohorts (Figure 1A and B), patients with CytoLym low/CAF high infiltration scores had the highest risk of disease recurrence. In the untreated population, patients with CytoLym high/CAF low tumors had significantly better DFS than CytoLym low/CAF high tumors (Figure 1A). In both untreated and stage II CRC, CytoLym infiltration scores were a critical determinant of prognosis, with significant differences in DFS when comparing CytoLym high versus CtyoLym low categories (Figure 1A and C). The same associations were found in both chemotherapy-treated and stage III CRC, but CAF infiltration scores helped segregate the strata even further (Figure 1B and D). Indeed, the poor DFS outcomes linked to high CAF infiltration scores were limited to stage III CRC (interaction P = 0.04). We found no major differences in CytoLym and CAF infiltration scores between stage III low-risk (T1−3, N1) and high-risk (T4 or N2) groups (supplementary Figure S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). However, 31.3% of high-risk stage III tumors are classified as CytoLym low/CAF high, while 24.5% of low-risk stage III patients fall into this category. Individual Kaplan−Meier DFS curves stratified by stage plus adjuvant chemotherapy exposure can be found in supplementary Figure S6, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Figure 1.

Adjusted disease-free survival (DFS) Kaplan−Meier curves stratified by CytoLym and CAF groups, estimated with multivariable Cox proportional hazard model controlling for pT, pN, age, sex, primary tumor location, MSI status and CMS4 scores:chemotherapy untreated (A), chemotherapy treated (B), stage II (C) and stage III (D) CRC cohorts.

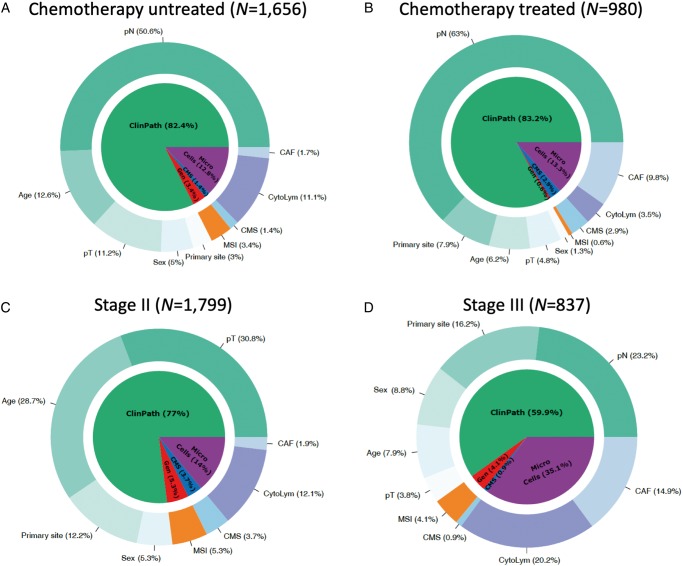

Figure 2 illustrates the relative contribution of different factors for prognosis prediction in early-stage CRC. Across all cohorts, the explained variation in multivariable DFS models for clinicopathological features, microenvironment infiltration scores, genomic markers and CMS4 scores were 83%, 11.4%, 3.7% and 1.9%, respectively. The relative contribution of clinicopathological features in prognosis prediction was larger in stage II as compared with stage III disease, while the impact of tumor microenvironment features on DFS is not diminished in more advanced stages of locoregional CRC (Figure 2C and D). In untreated and stage II cohorts (Figure 2A and C), in addition to CytoLym infiltration scores, age was an important contributor to DFS estimation, potentially associated with competing death risks. In adjuvant chemotherapy-treated and stage III cohorts (Figure 2B and C), CAF infiltration scores had substantial impact on DFS estimation.

Figure 2.

Relative proportion of explained variation in disease-free survival (DFS) of the full multivariable model in chemotherapy untreated (A), chemotherapy treated (B), stage II (C) and stage III (D) CRC cohorts.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated whether intrinsic gene expression signatures from cancer and microenvironment cells in stage II/III CRC have significant impact on DFS models adjusted for clinicopathological and genomic markers. For the first time, we show that the prognostic value of CMS groups is largely explained by tumor microenvironment infiltration patterns. In fact, CytoLym and CAF infiltration scores obviate the prognostic value of MSI status and CMS4 scores in multivariable models. We found that a high CytoLym infiltrated microenvironment is a critical determinant of improved outcomes and this ‘protective’ effect is strong across clinicopathological and genomic subgroups. Low microenvironment cytotoxic lymphocyte counts associates with higher chances of disease recurrence or death, particularly when tumors have a stromal invasive phenotype infiltrated with CAFs. Our results are in line with extensive literature built on pathology assessments of the tumor microenvironment showing the protective role of high infiltration by CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (approximately one-third of early-stage CRC population) [8] and the unfavorable outcome of patients whose tumors harbor high infiltration with stromal fibroblasts (∼40% of early-stage CRC population) [21]. Our data also suggest that the worse outcomes repeatedly seen in patients whose tumors display a mesenchymal-like phenotype may be directly linked to a prometastatic immune evasive and stromal-rich microenvironment. In fact, the impact of CAF infiltration scores on DFS estimation was larger in stage III and treated populations, which may be linked to a chemotherapy-resistance phenotype [16, 17]. Still, most CRC tumors have a ‘microenvironment desert’ phenotype, previously linked to epithelial CRC subtypes (CMS2 Canonical and CMS3 Metabolic) [15], known to have intermediate prognosis in early-stage disease. Here, the prognostic effect of cancer cell-intrinsic genomic markers may be more profound, as previously illustrated for KRAS mutations [22].

Although our results confirm the notion that activated immune cytotoxicity represents a potent determinant of the risk of distant dissemination, it is also known that immune and stromal infiltration patterns can be predicted by assessing intrinsic tumor cell epithelial expression profiles in early-stage CRC samples [23]. Moreover, interactions between immune cells, checkpoint expression and MSI status do have a clinically significant impact on prognosis. The expression levels of Immunoscore-like metagenes confers favorable prognosis in CRC patients with MSS tumors displaying low levels of CytoLym and immune checkpoints [24]. On the other hand, the expression levels of immune checkpoints annuls the prognostic relevance of CytoLym in highly immunogenic colon tumors and predicts a poor outcome in MSI CRC patients. These results are in line with our data showing a stronger signal for improved outcomes with CytoLym high scores mainly in the MSS population. To summarize, these data suggest that microenvironment markers must be analyzed alongside cancer cell genomic and transcriptomic markers for proper risk stratification.

Our study has limitations related to the retrospective, non-randomized nature of most patient cohorts included in the analysis, with missing values for some genomic markers such as KRAS, BRAFV600E mutations and MSI status in the range of 30%−50% in some cohorts. Therefore, no definite conclusions can be obtained from our study on the role of genomic markers for prognostication in early-stage CRC. Larger and more contemporary cohorts are needed to investigate whether the prognostic effect of microenvironment cells is modulated by adjuvant chemotherapies, particularly oxaliplatin-based. On the other hand, our study describes the largest cohort of untreated early-stage CRC patients with clinical, genomic and transcriptomic features, the ideal setting for multivariable survival modeling. In addition, prospective non-clinical trial series included in our analyses are representative of ‘real world’ populations. Indeed, recent insights on clinicopathological prognostic markers, such as primary tumor location, were validated in our aggregated cohort. In a recent SEER database study and a British Columbia cohort, stage II right-sided cancers had better cause-specific survival and relapse-free survival than the left-sided cancers, respectively [25, 26]. In stage III disease, right-sided poorly differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma showed significantly better survival than left-sided malignancies [25]. These results could be explained by the higher prevalence of MSI in right-sided high-grade tumors. We also found improved DFS for right-sided early-stage CRC when compared with left-sided disease, both in stage II and III disease. Interestingly, in a multivariable model, sidedness remained an independent prognostic factor when adjusting for MSI status. Our findings may be partly explained by unique patient characteristics included in population studies, such as a large proportion of elderly females.

To conclude, our data reinforce the idea that tumor microenvironment features should guide biomarker-drug co-development in the adjuvant setting. With recent advances in targeted immunotherapeutic interventions, we may be able to successfully boost anticancer immune cytotoxicity or inhibit immunosuppressive pathway dependencies that facilitate metastatic spread. The major impact of CAF infiltration scores on DFS of stage III and chemotherapy-treated populations deserves further validation in recent clinical trial cohorts, such as the IDEA consortium. We believe that our results will encourage clinical trial design with novel agents capable of reverting a chemotherapy-resistance phenotype linked to a distinct tumor microenvironment. When combined with liquid biopsies for detection of minimal residual disease [27], tumor and microenvironment biomarkers will eventually help personalize adjuvant therapies in early-stage CRC.

Funding

This study was supported by Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany (Grant for Oncology Innovation 2015, ‘Next generation of clinical trials with matched targeted therapies in colorectal cancer’). Merck KGaA reviewed the manuscript for medical accuracy only before journal submission. The authors are fully responsible for the content of this manuscript, and the views and opinions described in the publication reflect solely those of the authors. This work was also supported by the Norwegian Cancer Society (project numbers 6824048-2016 and 182759-2016) and the Research Council of Norway (project number 250993). VM received fund from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, co-funded by FEDER funds—a way to build Europe—grant PI14-00613, the Agency for Management of University and Research Grants (AGAUR) of the Catalan Government grant 2017SGR723 and the Scientific Foundation of the Spanish Association Against Cancer (AECC). RSW was supported by a grant from the NIH (RO184018).

Disclosure

RD has received speaker fee from Roche, Symphogen, Ipsen, Amgen, Sanofi, Servier, MSD and had advisory roles for Roche and Novartis over the last 2 years. RD and JG received research grant from Merck from 2015 to 2017. RAL received a Board of Directors member fee from Inven2, an innovation company for research at Oslo University Hospital and the University of Oslo. VM has received research funds from Universal Diagnostics and Bioiberica and had advisory role for Ferrer. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Siegel R, Miller KD, Fedewa SA. et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 64: 177–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer 2013; 49(6): 1374–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dienstmann R, Salazar R, Tabernero J.. Personalizing colon cancer adjuvant therapy: selecting optimal treatments for individual patients. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(16): 1787–1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dienstmann R, Mason MJ, Sinicrope FA. et al. Prediction of overall survival in stage II and III colon cancer beyond TNM system: a retrospective, pooled biomarker study. Ann Oncol 2017; 28(5): 1023–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mlecnik B, Bindea G, Kirilovsky A. et al. The tumor microenvironment and Immunoscore are critical determinants of dissemination to distant metastasis. Sci Transl Med 2016; 8(327): 327ra26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A. et al. Histopathologic-based prognostic factors of colorectal cancers are associated with the state of the local immune reaction. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29(6): 610–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sinicrope FA, Smyrk TC, Foster NR. et al. Association of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes with molecular subtype and prognosis in stage III colon cancers from a FOLFOX-based adjuvant chemotherapy trial. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34 (Suppl 15): 3518.27573653 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pagès F, Mlecnik B, Marliot F. et al. International validation of the consensus Immunoscore for the classification of colon cancer: a prognostic and accuracy study. Lancet 2018; 391(10135): 2128–2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bauer K, Nelius N, Reuschenbach M. et al. T cell responses against microsatellite instability-induced frameshift peptides and influence of regulatory T cells in colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2013; 62(1): 27–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mlecnik B, Bindea G, Angell HK. et al. Integrative analyses of colorectal cancer show immunoscore is a stronger predictor of patient survival than microsatellite instability. Immunity 2016; 44(3): 698–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Berdiel-Acer M, Berenguer A, Sanz-Pamplona R. et al. A 5-gene classifier from the carcinoma-associated fibroblast transcriptomic profile and clinical outcome in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget 2014; 5(15): 6437–6452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Calon A, Lonardo E, Berenguer-Llergo A. et al. Stromal gene expression defines poor-prognosis subtypes in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet 2015; 47(4): 320–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X. et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med 2015; 21(11): 1350–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Song N, Pogue-Geile KL, Gavin PG. et al. Clinical outcome from oxaliplatin treatment in stage II/III colon cancer according to intrinsic subtypes: secondary analysis of NSABP C-07/NRG Oncology Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 2016; 2(9): 1162–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Becht E, de Reynies A, Giraldo NA. et al. Immune and stromal classification of colorectal cancer is associated with molecular subtypes and relevant for precision immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 2016; 22(16): 4057–4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roepman P, Schlicker A, Tabernero J. et al. Colorectal cancer intrinsic subtypes predict chemotherapy benefit, deficient mismatch repair and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Int J Cancer 2014; 134(3): 552–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Straussman R, Morikawa T, Shee K. et al. Tumour micro-environment elicits innate resistance to RAF inhibitors through HGF secretion. Nature 2012; 487(7408): 500–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Becht E, Giraldo NA, Lacroix L. et al. Estimating the population abundance of tissue-infiltrating immune and stromal cell populations using gene expression. Genome Biol 2016; 17(1): 218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Royston P. Explained variation for survival models. Stata J 2 − 6(6): 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- 20.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2008. http://www.r-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huijbers A, van Pelt GW, Kerr RS. et al. The value of additional bevacizumab in patients with high-risk stroma-high colon cancer. A study within the QUASAR2 trial, an open-label randomized phase 3 trial. J Surg Oncol 2018; 117(5): 1043–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Smeby J, Sveen A, Merok MA. et al. CMS-dependent prognostic impact of KRAS and BRAFV600E mutations in primary colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2018; 29(5): 1227–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wirapati P, Qu X, Huw L. et al. Prognostic stromal and immune response expression patterns in early-stage colorectal cancer predicted by genes intrinsically expressed by tumor epithelial cells. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37(Suppl); 3601. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marisa L, Svrcek M, Collura A. et al. The balance between cytotoxic T-cell lymphocytes and immune checkpoint expression in the prognosis of colon tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018; 110(1): 68–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li Y, Feng Y, Dai W. et al. Prognostic effect of tumor sidedness in colorectal cancer: a SEER-based analysis. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2019; 18(1): e104–e116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kennecke HF, Yin Y, Davies JM. et al. Prognostic effect of sidedness in early stage versus advanced colon cancer. Health Sci Rep 2018; 1(8): e54.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dasari A, Grothey A, Kopetz S.. Circulating tumor DNA-defined minimal residual disease in solid tumors: opportunities to accelerate the development of adjuvant therapies. J Clin Oncol 2018; 35: 3437–3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.